A natural product is a natural

compound or

substance produced by a living organism—that is, found in

nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

.

In the broadest sense, natural products include any substance produced by life.

Natural products can also be prepared by

chemical synthesis

Chemical synthesis (chemical combination) is the artificial execution of chemical reactions to obtain one or several products. This occurs by physical and chemical manipulations usually involving one or more reactions. In modern laboratory uses ...

(both

semisynthesis

Semisynthesis, or partial chemical synthesis, is a type of chemical synthesis that uses chemical compounds isolated from natural sources (such as microbiology, microbial cell cultures or plant material) as the starting materials to produce novel ...

and

total synthesis

Total synthesis, a specialized area within organic chemistry, focuses on constructing complex organic compounds, especially those found in nature, using laboratory methods. It often involves synthesizing natural products from basic, commercially ...

and have played a central role in the development of the field of

organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

by providing challenging synthetic targets). The term ''natural product'' has also been extended for commercial purposes to refer to

cosmetics

Cosmetics are substances that are intended for application to the body for cleansing, beautifying, promoting attractiveness, or altering appearance. They are mixtures of chemical compounds derived from either Natural product, natural source ...

,

dietary supplement

A dietary supplement is a manufactured product intended to supplement a person's diet by taking a pill (pharmacy), pill, capsule (pharmacy), capsule, tablet (pharmacy), tablet, powder, or liquid. A supplement can provide nutrients eithe ...

s, and foods produced from natural sources without added artificial ingredients.

Within the field of organic chemistry, the definition of natural products is usually restricted to

organic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

s isolated from natural sources that are produced by the pathways of

primary or

secondary metabolism.

Within the field of

medicinal chemistry

Medicinal or pharmaceutical chemistry is a scientific discipline at the intersection of chemistry and pharmacy involved with drug design, designing and developing pharmaceutical medication, drugs. Medicinal chemistry involves the identification, ...

, the definition is often further restricted to secondary metabolites.

Secondary metabolites (or specialized metabolites) are not essential for survival, but nevertheless provide organisms that produce them an evolutionary advantage.

Many secondary metabolites are

cytotoxic and have been selected and optimized through evolution for use as "chemical warfare" agents against prey, predators, and competing organisms.

Secondary or specialized metabolites are often unique to specific species, whereas primary metabolites are commonly found across multiple kingdoms. Secondary metabolites are marked by chemical complexity which is why they are of such interest to chemists.

Natural sources may lead to

basic research

Basic research, also called pure research, fundamental research, basic science, or pure science, is a type of scientific research with the aim of improving scientific theories for better understanding and prediction of natural or other phenome ...

on potential bioactive components for commercial development as

lead compounds in

drug discovery

In the fields of medicine, biotechnology, and pharmacology, drug discovery is the process by which new candidate medications are discovered.

Historically, drugs were discovered by identifying the active ingredient from traditional remedies or ...

.

Although natural products have inspired numerous drugs,

drug development

Drug development is the process of bringing a new pharmaceutical drug to the market once a lead compound has been identified through the process of drug discovery. It includes preclinical research on microorganisms and animals, filing for regu ...

from natural sources has received declining attention in the 21st century by pharmaceutical companies, partly due to unreliable access and supply, intellectual property, cost, and

profit

Profit may refer to:

Business and law

* Profit (accounting), the difference between the purchase price and the costs of bringing to market

* Profit (economics), normal profit and economic profit

* Profit (real property), a nonpossessory inter ...

concerns, seasonal or environmental variability of composition, and loss of sources due to rising

extinction

Extinction is the termination of an organism by the death of its Endling, last member. A taxon may become Functional extinction, functionally extinct before the death of its last member if it loses the capacity to Reproduction, reproduce and ...

rates.

[ Despite this, natural products and their derivatives still accounted for about 10% of new drug approvals between 2017 and 2019.][ Natural products represent 100*(506/1881) = 27% of new drug approvals from 01JAN81 to 30SEP19. From Figure 9, the percentage was ~10% for 2017-2019.]

Classes

The broadest definition of natural product is anything that is produced by life,bioplastic

Bioplastics are plastic materials produced from renewable biomass sources. Timeline of plastic development, Historically, bioplastics made from natural materials like shellac or Celluloid, cellulose had been the first plastics. Since the end of ...

s, cornstarch), bodily fluid

Body fluids, bodily fluids, or biofluids, sometimes body liquids, are liquids within the body of an organism. In lean healthy adult men, the total body water is about 60% (60–67%) of the total body weight; it is usually slightly lower in wom ...

s (e.g. milk, plant exudates), and other natural materials (e.g. soil, coal).

Natural products may be classified according to their biological function, biosynthetic pathway, or source. Depending on the sources, the number of known natural product molecules ranges between 300,000

Function

Following Albrecht Kossel

Ludwig Karl Martin Leonhard Albrecht Kossel (; 16 September 1853 – 5 July 1927) was a biochemist and pioneer in the study of genetics. He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine in 1910 for his work in determining the chemical ...

's original proposal in 1891,morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

and nicotine

Nicotine is a natural product, naturally produced alkaloid in the nightshade family of plants (most predominantly in tobacco and ''Duboisia hopwoodii'') and is widely used recreational drug use, recreationally as a stimulant and anxiolytic. As ...

act as defense chemicals against herbivores, while flavonoids attract pollinators, and terpenes

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

such as menthol

Menthol is an organic compound, specifically a Monoterpene, monoterpenoid, that occurs naturally in the oils of several plants in the Mentha, mint family, such as Mentha arvensis, corn mint and peppermint. It is a white or clear waxy crystallin ...

serve to repel insects. Because of their ability to modulate biochemical and signal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a biochemical cascade, series of molecular events. Proteins responsible for detecting stimuli are generally termed receptor (biology), rece ...

pathways, some secondary metabolites have useful medicinal properties.

Natural products especially within the field of organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the science, scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic matter, organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain ...

are often defined as primary and secondary metabolites.medicinal chemistry

Medicinal or pharmaceutical chemistry is a scientific discipline at the intersection of chemistry and pharmacy involved with drug design, designing and developing pharmaceutical medication, drugs. Medicinal chemistry involves the identification, ...

and pharmacognosy.

Primary metabolites

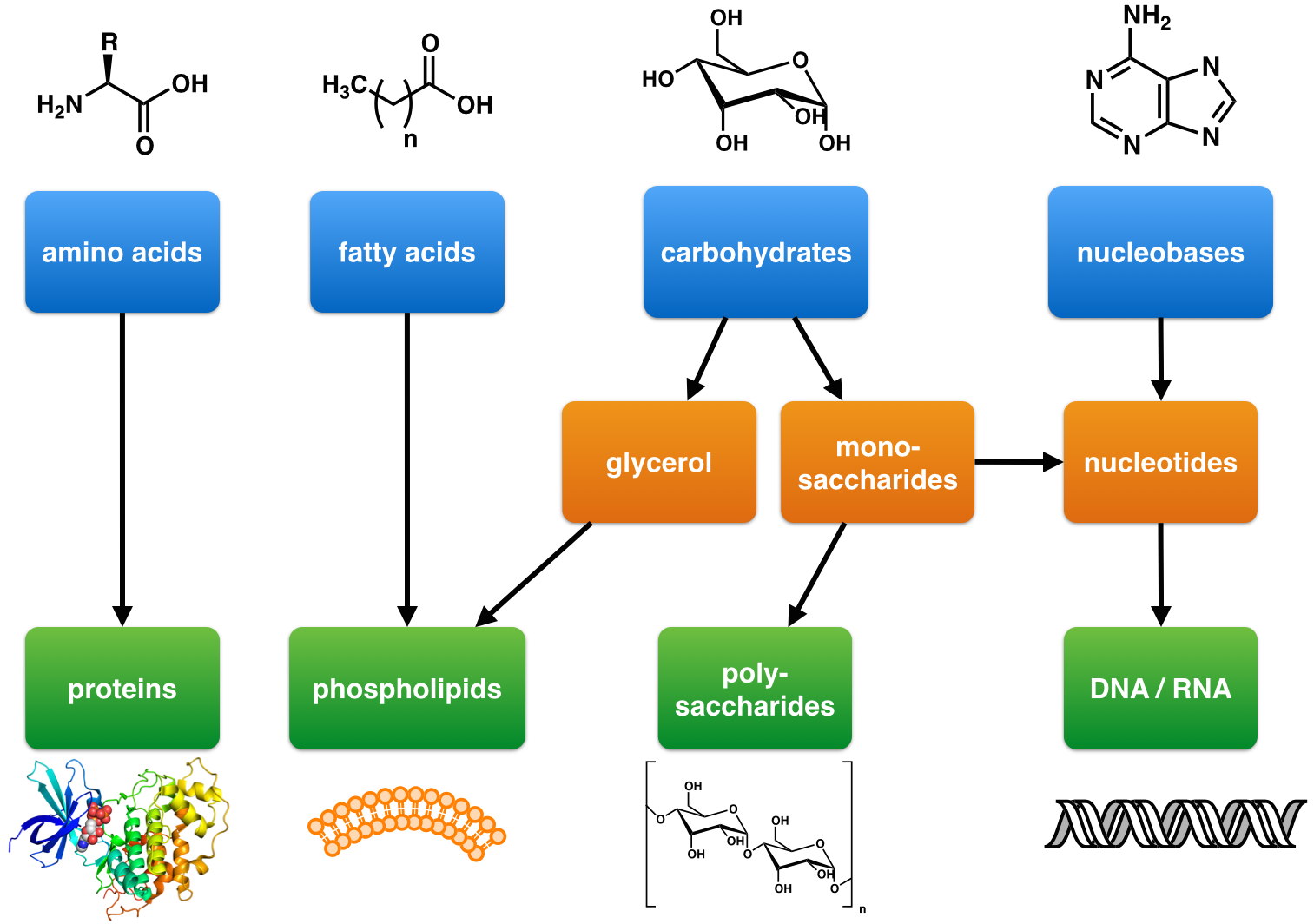

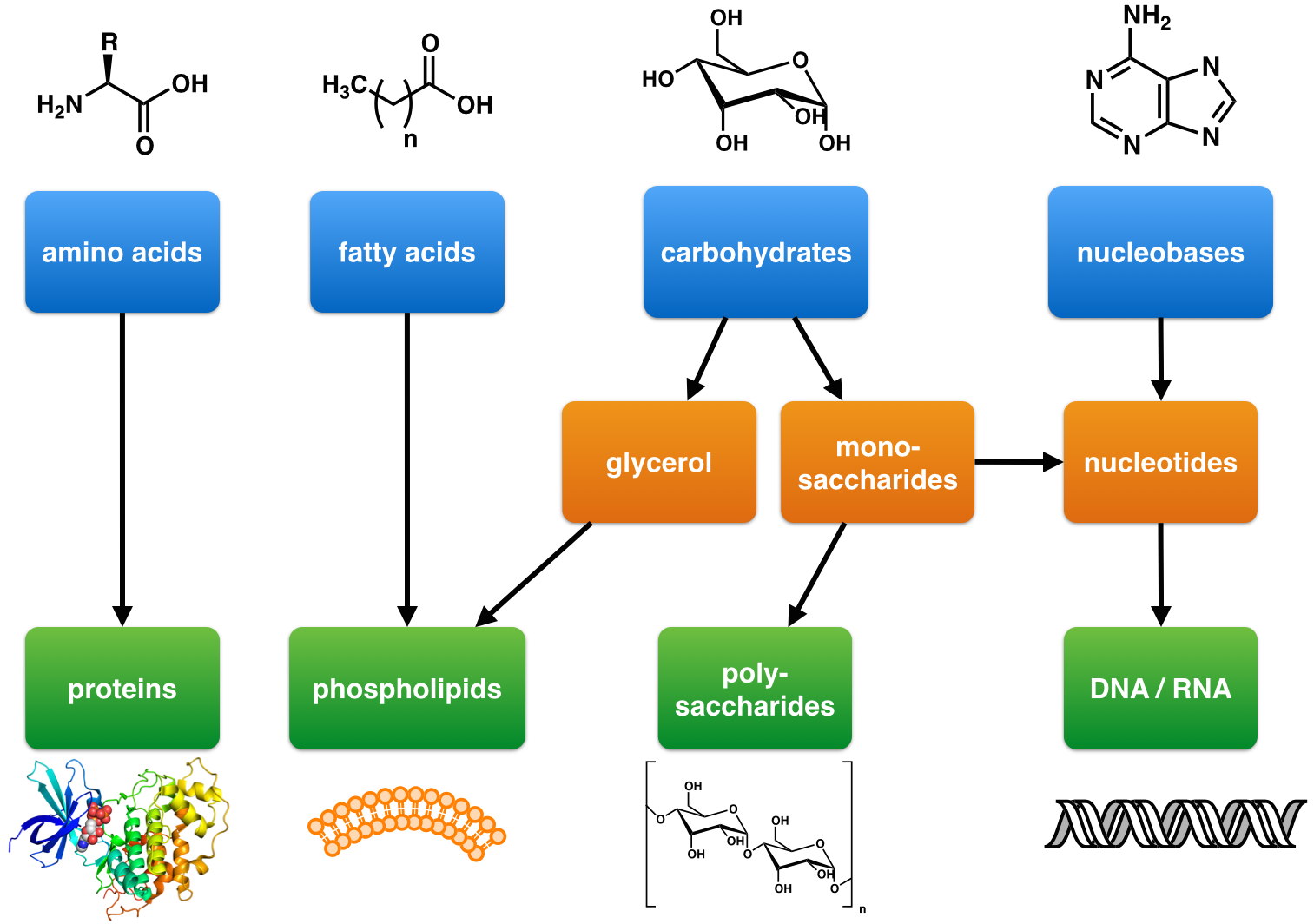

Primary metabolites, as defined by Kossel, are essential components of basic metabolic pathways required for life. They are associated with fundamental cellular functions such as nutrient assimilation, energy production, and growth and development. These metabolites have a wide distribution across many

Primary metabolites, as defined by Kossel, are essential components of basic metabolic pathways required for life. They are associated with fundamental cellular functions such as nutrient assimilation, energy production, and growth and development. These metabolites have a wide distribution across many phyla

Phyla, the plural of ''phylum'', may refer to:

* Phylum, a biological taxon between Kingdom and Class

* by analogy, in linguistics, a large division of possibly related languages, or a major language family which is not subordinate to another

Phy ...

and often span more than one kingdom. Primary metabolites include the basic building blocks of life: carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s, lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s, amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s, and nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s.photosynthetic

Photosynthesis ( ) is a Biological system, system of biological processes by which Photoautotrophism, photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical ener ...

processes. These enzymes are composed of amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s and often require non-peptidic cofactors for proper function.phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s), cell walls (e.g., peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating ...

, chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

), and cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

s (proteins).

Enzymatic cofactors that are primary metabolites include several members of the vitamin B

B vitamins are a class of water-soluble vitamins that play important roles in cell metabolism and synthesis of red blood cells. They are a chemically diverse class of compounds.

Dietary supplements containing all eight are referred to as a vita ...

family. For instance, Vitamin B1 (thiamine diphosphate), synthesized from 1-deoxy-D-xylulose 5-phosphate, serves as a coenzyme for enzymes such as pyruvate dehydrogenase, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, and transketolase

Transketolase (abbreviated as TK) is an enzyme that, in humans, is encoded by the ''TKT'' gene. It participates in both the pentose phosphate pathway in all organisms and the Calvin cycle of photosynthesis. Transketolase catalyzes two important r ...

—all involved in carbohydrate metabolism. Vitamin B2

Riboflavin, also known as vitamin B2, is a vitamin found in food and sold as a dietary supplement. It is essential to the formation of two major coenzymes, flavin mononucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide. These coenzymes are involved in ...

(riboflavin), derived from ribulose 5-phosphate and guanosine triphosphate

Guanosine-5'-triphosphate (GTP) is a purine nucleoside triphosphate. It is one of the building blocks needed for the synthesis of RNA during the transcription process. Its structure is similar to that of the guanosine nucleoside, the only di ...

, is a precursor to FMN and FAD

A fad, trend, or craze is any form of collective behavior that develops within a culture, a generation, or social group in which a group of people enthusiastically follow an impulse for a short time period.

Fads are objects or behaviors tha ...

, which are crucial for various redox reactions. Vitamin B3 (nicotinic acid or niacin), synthesized from tryptophan, is an essential part of the coenzymes NAD and NADP, necessary for electron transport in the Krebs cycle

The citric acid cycle—also known as the Krebs cycle, Szent–Györgyi–Krebs cycle, or TCA cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle)—is a series of biochemical reactions that release the energy stored in nutrients through acetyl-CoA oxidation. The e ...

, oxidative phosphorylation

Oxidative phosphorylation(UK , US : or electron transport-linked phosphorylation or terminal oxidation, is the metabolic pathway in which Cell (biology), cells use enzymes to Redox, oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing chemical energy in order ...

, and other redox processes. Vitamin B5 (pantothenic acid), derived from α,β-dihydroxyisovalerate (a precursor to valine

Valine (symbol Val or V) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α- amino group (which is in the protonated −NH3+ form under biological conditions), an α- carboxylic acid group (which is in the deproton ...

) and aspartic acid, is a component of coenzyme A

Coenzyme A (CoA, SHCoA, CoASH) is a coenzyme, notable for its role in the Fatty acid metabolism#Synthesis, synthesis and Fatty acid metabolism#.CE.B2-Oxidation, oxidation of fatty acids, and the oxidation of pyruvic acid, pyruvate in the citric ac ...

, which plays a vital role in carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism, as well as fatty acid biosynthesis. Vitamin B6

Vitamin B6 is one of the B vitamins, and is an essential nutrient for humans. The term essential nutrient refers to a group of six chemically similar compounds, i.e., "vitamers", which can be interconverted in biological systems. Its active f ...

(pyridoxol, pyridoxal, and pyridoxamine, originating from erythrose 4-phosphate), functions as pyridoxal 5′-phosphate and acts as a cofactor for enzymes, particularly transaminases, involved in amino acid metabolism. Vitamin B12

Vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, is a water-soluble vitamin involved in metabolism. One of eight B vitamins, it serves as a vital cofactor (biochemistry), cofactor in DNA synthesis and both fatty acid metabolism, fatty acid and amino a ...

(cobalamins) contains a corrin ring structure, similar to porphyrin, and serves as a coenzyme in fatty acid catabolism and methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans.

As the precursor of other non-essential amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine play ...

synthesis.retinol

Retinol, also called vitamin A1, is a fat-soluble vitamin in the vitamin A family that is found in food and used as a dietary supplement. Retinol or other forms of vitamin A are needed for vision, cellular development, maintenance of skin and ...

(vitamin A),carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

s via the mevalonate pathway

The mevalonate pathway, also known as the isoprenoid pathway or HMG-CoA reductase pathway is an essential metabolic pathway present in eukaryotes, archaea, and some bacteria. The pathway produces two five-carbon building blocks called isopentenyl ...

, and ascorbic acid

Ascorbic acid is an organic compound with formula , originally called hexuronic acid. It is a white solid, but impure samples can appear yellowish. It dissolves freely in water to give mildly acidic solutions. It is a mild reducing agent.

Asco ...

(vitamin C),glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

in the liver of animals, though not in humans.

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

and RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

, which store and transmit genetic information

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of Nucleobase, bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the orde ...

, are synthesized from primary metabolites, specifically nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s and carbohydrates.metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

and cellular differentiation

Cellular differentiation is the process in which a stem cell changes from one type to a differentiated one. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation happens multiple times during the development of a multicellula ...

. These include hormones and growth factors composed of peptides, biogenic amines, steroid hormone

A steroid hormone is a steroid that acts as a hormone. Steroid hormones can be grouped into two classes: corticosteroids (typically made in the adrenal cortex, hence ''cortico-'') and sex steroids (typically made in the gonads or placenta). Wit ...

s, auxin

Auxins (plural of auxin ) are a class of plant hormones (or plant-growth regulators) with some morphogen-like characteristics. Auxins play a cardinal role in coordination of many growth and behavioral processes in plant life cycles and are essent ...

s, and gibberellin

Gibberellins (GAs) are plant hormones that regulate various Biological process, developmental processes, including Plant stem, stem elongation, germination, dormancy, flowering, flower development, and leaf and fruit senescence. They are one of th ...

s. These first messengers interact with cellular receptors, which are protein-based, and trigger the activation of second messengers to relay the extracellular signal to intracellular targets. Second messengers often include primary metabolites such as cyclic nucleotide

A cyclic nucleotide (cNMP) is a single-phosphate nucleotide with a cyclic bond arrangement between the sugar and phosphate groups. Like other nucleotides, cyclic nucleotides are composed of three functional groups: a sugar, a nitrogenous base, ...

s and diacyl glycerol.

Secondary metabolites

Secondary in contrast to primary metabolites are dispensable and not absolutely required for survival. Furthermore, secondary metabolites typically have a narrow species distribution.

Secondary metabolites have a broad range of functions. These include

Secondary in contrast to primary metabolites are dispensable and not absolutely required for survival. Furthermore, secondary metabolites typically have a narrow species distribution.

Secondary metabolites have a broad range of functions. These include pheromone

A pheromone () is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavio ...

s that act as social signaling molecules with other individuals of the same species, communication molecules that attract and activate symbiotic

Symbiosis (Ancient Greek : living with, companionship < : together; and ''bíōsis'': living) is any type of a close and long-term biolo ...

organisms, agents that solubilize and transport nutrients (siderophores

Siderophores (Greek: "iron carrier") are small, high-affinity iron-Chelation, chelating compounds that are secreted by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. They help the organism accumulate iron. Although a widening range of siderophore func ...

etc.), and competitive weapons ( repellants, venoms, toxins etc.) that are used against competitors, prey, and predators.immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

, these secondary metabolites have no specific function, but having the machinery in place to produce these diverse chemical structures is important and a few secondary metabolites are therefore produced and selected for.alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s, phenylpropanoid

The phenylpropanoids are a diverse family of organic compounds that are biosynthesized by plants from the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine in the shikimic acid pathway. Their name is derived from the six-carbon, aromatic phenyl group and ...

s, polyketides, and terpenoid

The terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, are a class of naturally occurring organic compound, organic chemicals derived from the 5-carbon compound isoprene and its derivatives called terpenes, diterpenes, etc. While sometimes used interchangeabl ...

s.

Biosynthesis

The biosynthetic pathways leading to the major classes of natural products are described below.

The biosynthetic pathways leading to the major classes of natural products are described below.

Carbohydrates

Carbohydrate

A carbohydrate () is a biomolecule composed of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), and oxygen (O) atoms. The typical hydrogen-to-oxygen atomic ratio is 2:1, analogous to that of water, and is represented by the empirical formula (where ''m'' and ''n'' ...

s are organic molecules essential for energy storage, structural support, and various biological processes in living organisms. They are produced through photosynthesis

Photosynthesis ( ) is a system of biological processes by which photosynthetic organisms, such as most plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, convert light energy, typically from sunlight, into the chemical energy necessary to fuel their metabo ...

in plants or gluconeogenesis

Gluconeogenesis (GNG) is a metabolic pathway that results in the biosynthesis of glucose from certain non-carbohydrate carbon substrates. It is a ubiquitous process, present in plants, animals, fungi, bacteria, and other microorganisms. In verte ...

in animals and can be converted into larger polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s:monosaccharide

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units (monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are polyhy ...

s → polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s (cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the chemical formula, formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of glycosidic bond, β(1→4) linked glucose, D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important s ...

, chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, glycogen

Glycogen is a multibranched polysaccharide of glucose that serves as a form of energy storage in animals, fungi, and bacteria. It is the main storage form of glucose in the human body.

Glycogen functions as one of three regularly used forms ...

, etc.)

Carbohydrates serve as a primary energy source for most life forms. Additionally, polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s derived from simpler sugars are vital structural components, forming the cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

s of bacteriaglucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

(a six-carbon sugar) or various pentoses (five-carbon sugars) through the Calvin cycle. In animals, three-carbon precursors like lactate or glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

are converted into pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic ...

, which can then be synthesized into carbohydrates in the liver.

Fatty acids and polyketides

Fatty acid

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated and unsaturated compounds#Organic chemistry, saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an ...

s and polyketides are synthesized via the acetate pathway, which starts from basic building blocks derived from sugars:glycolysis

Glycolysis is the metabolic pathway that converts glucose () into pyruvic acid, pyruvate and, in most organisms, occurs in the liquid part of cells (the cytosol). The Thermodynamic free energy, free energy released in this process is used to form ...

, sugars are broken down into acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidation, o ...

. In an ATP-dependent enzymatic reaction, acetyl-CoA is carboxylated to form malonyl-CoA. Acetyl-CoA and malonyl-CoA then undergo a Claisen condensation, releasing carbon dioxide to form acetoacetyl-CoA which is used by the mevalonate pathway

The mevalonate pathway, also known as the isoprenoid pathway or HMG-CoA reductase pathway is an essential metabolic pathway present in eukaryotes, archaea, and some bacteria. The pathway produces two five-carbon building blocks called isopentenyl ...

to produce steroids. In fatty acid synthesis

In biochemistry, fatty acid synthesis is the creation of fatty acids from acetyl-CoA and NADPH through the action of enzymes. Two ''De novo synthesis, de novo'' fatty acid syntheses can be distinguished: cytosolic fatty acid synthesis (FAS/FASI) ...

, one molecule of acetyl-CoA (the "starter unit") and several molecules of malonyl-CoA (the "extender units") are condensed by fatty acid synthase

Fatty acid synthase (FAS) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the ''FASN'' gene.

Fatty acid synthase is a multi-enzyme protein that catalyzes fatty acid synthesis. It is not a single enzyme but a whole enzymatic system composed of two ide ...

.alcohol

Alcohol may refer to:

Common uses

* Alcohol (chemistry), a class of compounds

* Ethanol, one of several alcohols, commonly known as alcohol in everyday life

** Alcohol (drug), intoxicant found in alcoholic beverages

** Alcoholic beverage, an alco ...

dehydrated, and resulting enoyl-CoAs are reduced to acyl-CoAs. Fatty acids are essential components of lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes form a continuous barrier around all cell (biology), cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many viruses a ...

s that form cell membranes and serve as energy storage in the form of fat in animals.

The plant-derived fatty acid linoleic acid

Linoleic acid (LA) is an organic compound with the formula . Both alkene groups () are ''cis''. It is a fatty acid sometimes denoted 18:2 (n−6) or 18:2 ''cis''-9,12. A linoleate is a salt or ester of this acid.

Linoleic acid is a polyunsat ...

is converted in animals through elongation and desaturation into arachidonic acid

Arachidonic acid (AA, sometimes ARA) is a polyunsaturated omega−6 fatty acid 20:4(ω−6), or 20:4(5,8,11,14). It is a precursor in the formation of leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and thromboxanes.

Together with omega−3 fatty acids an ...

, which is then transformed into various eicosanoid

Eicosanoids are lipid signaling, signaling molecules made by the enzymatic or non-enzymatic oxidation of arachidonic acid or other polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) that are, similar to arachidonic acid, around 20 carbon units in length. Eicosa ...

s, including leukotriene

Leukotrienes are a family of eicosanoid inflammation, inflammatory mediators produced in leukocytes by the redox, oxidation of arachidonic acid (AA) and the essential fatty acid eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) by the enzyme arachidonate 5-lipoxyg ...

s, prostaglandin

Prostaglandins (PG) are a group of physiology, physiologically active lipid compounds called eicosanoids that have diverse hormone-like effects in animals. Prostaglandins have been found in almost every Tissue (biology), tissue in humans and ot ...

s, and thromboxane

Thromboxane is a member of the family of lipids known as eicosanoids. The two major thromboxanes are thromboxane A2 and thromboxane B2. The distinguishing feature of thromboxanes is a 6-membered ether-containing ring.

Thromboxane is named for ...

s. These eicosanoids act as signaling molecules, playing key roles in inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

and immune response

An immune response is a physiological reaction which occurs within an organism in the context of inflammation for the purpose of defending against exogenous factors. These include a wide variety of different toxins, viruses, intra- and extracellula ...

s.

Aromatic amino acids and phenylpropanoids

The shikimate pathway is a key metabolic route responsible for the production of aromatic amino acids and their derivatives in plants, fungi, bacteria, and some protozoans:phenylpropanoid

The phenylpropanoids are a diverse family of organic compounds that are biosynthesized by plants from the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine in the shikimic acid pathway. Their name is derived from the six-carbon, aromatic phenyl group and ...

s

The shikimate pathway leads to the biosynthesis of aromatic amino acids (AAAs) — phenylalanine

Phenylalanine (symbol Phe or F) is an essential α-amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . It can be viewed as a benzyl group substituent, substituted for the methyl group of alanine, or a phenyl group in place of a terminal hydrogen of ...

, tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a conditionally essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is ...

, and tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α-carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromat ...

.phosphoenolpyruvate

Phosphoenolpyruvate (2-phosphoenolpyruvate, PEP) is the carboxylic acid derived from the enol of pyruvate and a phosphate anion. It exists as an anion. PEP is an important intermediate in biochemistry. It has the high-energy phosphate, highest-e ...

(PEP) and erythrose-4-phosphate (E4P), leading through several enzymatic steps to form chorismate, the precursor for all three AAAs.

Terpenoids and steroids

The biosynthesis of

The biosynthesis of terpenoid

The terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, are a class of naturally occurring organic compound, organic chemicals derived from the 5-carbon compound isoprene and its derivatives called terpenes, diterpenes, etc. While sometimes used interchangeabl ...

s and steroid

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused compound, fused rings (designated A, B, C, and D) arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes t ...

s involves two primary pathways, which produce essential building blocks for these compounds:Mevalonate pathway

The mevalonate pathway, also known as the isoprenoid pathway or HMG-CoA reductase pathway is an essential metabolic pathway present in eukaryotes, archaea, and some bacteria. The pathway produces two five-carbon building blocks called isopentenyl ...

and methylerythritol phosphate pathway → terpenoid

The terpenoids, also known as isoprenoids, are a class of naturally occurring organic compound, organic chemicals derived from the 5-carbon compound isoprene and its derivatives called terpenes, diterpenes, etc. While sometimes used interchangeabl ...

s and steroid

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused compound, fused rings (designated A, B, C, and D) arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes t ...

s

The mevalonate (MVA) and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways produce the five-carbon units isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP), which are the building blocks for all terpenoids.HMG-CoA

β-Hydroxy β-methylglutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA), also known as 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A, is an intermediate in the mevalonate pathway, mevalonate and ketogenesis pathways. It is formed from acetyl CoA and acetoacetyl CoA by HMG-CoA synthase ...

and mevalonate, and is essential for steroid biosynthesis. Statin

Statins (or HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) are a class of medications that lower cholesterol. They are prescribed typically to people who are at high risk of cardiovascular disease.

Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) carriers of cholesterol play ...

s, which lower cholesterol, work by inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase in this pathway.pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic ...

and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate to produce IPP and DMAPP. This pathway is crucial for the synthesis of plastid

A plastid is a membrane-bound organelle found in the Cell (biology), cells of plants, algae, and some other eukaryotic organisms. Plastids are considered to be intracellular endosymbiotic cyanobacteria.

Examples of plastids include chloroplasts ...

terpenoids like carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

s and chlorophyll

Chlorophyll is any of several related green pigments found in cyanobacteria and in the chloroplasts of algae and plants. Its name is derived from the Greek words (, "pale green") and (, "leaf"). Chlorophyll allows plants to absorb energy ...

s.monoterpene

Monoterpenes are a class of terpenes that consist of two isoprene units and have the molecular formula C10H16. Monoterpenes may be linear (acyclic) or contain rings (monocyclic and bicyclic). Modified terpenes, such as those containing oxygen func ...

s, sesquiterpene

Sesquiterpenes are a class of terpenes that consist of three isoprene units and often have the molecular formula C15H24. Like monoterpenes, sesquiterpenes may be cyclic or contain rings, including many combinations. Biochemical modifications s ...

s, and triterpene

Triterpenes are a class of terpenes composed of six isoprene units with the molecular formula C30H48; they may also be thought of as consisting of three terpene units. Animals, plants and fungi all produce triterpenes, including squalene, the pre ...

s.oxidation

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

, and glycosylation

Glycosylation is the reaction in which a carbohydrate (or ' glycan'), i.e. a glycosyl donor, is attached to a hydroxyl or other functional group of another molecule (a glycosyl acceptor) in order to form a glycoconjugate. In biology (but not ...

, enabling them to play roles in plant defense, pollinator attraction, and signaling. Steroids, primarily synthesized via the MVA pathway, are derived from farnesyl diphosphate through intermediates like squalene

Squalene is an organic compound. It is a triterpene with the formula C30H50. It is a colourless oil, although impure samples appear yellow. It was originally obtained from shark liver oil (hence its name, as '' Squalus'' is a genus of sharks). ...

and lanosterol

Lanosterol is a tetracyclic triterpenoid and is the compound from which all animal and fungal steroids are derived. By contrast, plant steroids are produced via cycloartenol. In the eyes of vertebrates, lanosterol is a natural constituent, havin ...

, which are precursors to cholesterol and other steroid molecules.

Alkaloids

Alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

s are nitrogen-containing organic compounds produced by plants through complex biosynthetic pathways, starting from amino acids. The biosynthesis of alkaloids from amino acids is essential for producing many biologically active compounds in plants. These compounds range from simple cycloaliphatic amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are organic compounds that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. Amines are formed when one or more hydrogen atoms in ammonia are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. The nitrogen atom in an amine possesses a lone pair of elec ...

s to complex polycyclic nitrogen heterocycles.amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are organic compounds that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. Amines are formed when one or more hydrogen atoms in ammonia are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. The nitrogen atom in an amine possesses a lone pair of elec ...

precursor, (ii) synthesis of an aldehyde

In organic chemistry, an aldehyde () (lat. ''al''cohol ''dehyd''rogenatum, dehydrogenated alcohol) is an organic compound containing a functional group with the structure . The functional group itself (without the "R" side chain) can be referred ...

precursor, (iii) formation of an iminium cation, and (iv) a Mannich-like reaction. These steps form the core structure of many alkaloids and represent the initial committed steps in their production.tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α-carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromat ...

, tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a conditionally essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is ...

, lysine

Lysine (symbol Lys or K) is an α-amino acid that is a precursor to many proteins. Lysine contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated form when the lysine is dissolved in water at physiological pH), an α-carboxylic acid group ( ...

, arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidinium, guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) a ...

, and ornithine

Ornithine is a non-proteinogenic α-amino acid that plays a role in the urea cycle. It is not incorporated into proteins during translation. Ornithine is abnormally accumulated in the body in ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency, a disorder of th ...

serve as essential precursors. Their accumulation is facilitated by mechanisms like increased gene expression, gene duplication, or the evolution of enzymes with broader substrate specificities.cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

follows this general pathway.strictosidine

Strictosidine is a natural chemical compound and is classified as a glucoalkaloid and a vinca alkaloid. It is formed by the Pictet–Spengler condensation reaction of tryptamine with secologanin, catalyzed by the enzyme strictosidine synthase. ...

, a precursor to numerous monoterpene indole alkaloids.Oxidoreductase

In biochemistry, an oxidoreductase is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of electrons from one molecule, the reductant, also called the electron donor, to another, the oxidant, also called the electron acceptor. This group of enzymes usually ut ...

s, including cytochrome P450s and flavin-containing monooxygenase

Monooxygenases are enzymes that incorporate one hydroxyl group (−OH) into substrates in many metabolic pathways. In this reaction, the two atoms of dioxygen are reduced to one hydroxyl group and one H2O molecule by the concomitant oxidation of ...

s, play a vital role in modifying the core alkaloid structures through oxidation, contributing to their structural diversity and bioactivity. For instance, in the biosynthesis of morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

, oxidative coupling is essential for forming the complex polycyclic structures typical of these alkaloids.tropane

Tropane is a nitrogenous bicyclic organic compound. It is mainly known for the other alkaloids derived from it, which include atropine and cocaine, among others. Tropane alkaloids occur in plants of the families Erythroxylaceae (including coca) ...

alkaloids, derived from ornithine, undergo processes such as decarboxylation, oxidation, and cyclization. Similarly, the biosynthesis of isoquinoline alkaloids from tyrosine involves complex transformations, including the formation of (S)- reticuline, a key intermediate in the pathway.

Peptides, proteins, and other amino acid derivatives

Biosynthesis of peptides, proteins, and other amino acid derivatives assembles amino acids into biologically active molecules, producing compounds like peptide hormones, modified peptides, and plant-derived substances.protein synthesis

Protein biosynthesis, or protein synthesis, is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via degradation or export) through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critica ...

or translation, a process involving transcription of DNA into messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

(mRNA). The mRNA serves as a template for protein assembly on ribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

s. During translation, transfer RNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

(tRNA) carries specific amino acids to match with mRNA codons, forming peptide bonds to create the protein chain.

Peptide hormone

Peptide hormones are hormones composed of peptide molecules. These hormones influence the endocrine system of animals, including humans. Most hormones are classified as either amino-acid-based hormones (amines, peptides, or proteins) or steroid h ...

s, such as oxytocin

Oxytocin is a peptide hormone and neuropeptide normally produced in the hypothalamus and released by the posterior pituitary. Present in animals since early stages of evolution, in humans it plays roles in behavior that include Human bonding, ...

and vasopressin

Mammalian vasopressin, also called antidiuretic hormone (ADH), arginine vasopressin (AVP) or argipressin, is a hormone synthesized from the ''AVP'' gene as a peptide prohormone in neurons in the hypothalamus, and is converted to AVP. It ...

, are short amino acid chains that regulate physiological processes, including social bonding and water retention.antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

s like penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

s and cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus '' Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibio ...

s, characterized by their β-lactam ring structure, which is essential for their antibacterial activity.sulfur

Sulfur ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphur ( Commonwealth spelling) is a chemical element; it has symbol S and atomic number 16. It is abundant, multivalent and nonmetallic. Under normal conditions, sulfur atoms ...

-containing compounds in cruciferous vegetables like broccoli

Broccoli (''Brassica oleracea'' var. ''italica'') is an edible green plant in the Brassicaceae, cabbage family (family Brassicaceae, genus ''Brassica'') whose large Pseudanthium, flowering head, plant stem, stalk and small associated leafy gre ...

and mustard. Their biosynthesis starts with amino acids such as methionine or tryptophan and involves adding sulfur and glucose groups.

Sources

Natural products may be extracted from the cells, tissues, and secretion

Secretion is the movement of material from one point to another, such as a secreted chemical substance from a cell or gland. In contrast, excretion is the removal of certain substances or waste products from a cell or organism. The classical mec ...

s of microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s, plants and animals.bioprospecting

Bioprospecting (also known as biodiversity prospecting) is the exploration of natural sources for small molecules, macromolecules and biochemical and genetic information that could be developed into commercialization, commercially valuable prod ...

.mechanism of action

In pharmacology, the term mechanism of action (MOA) refers to the specific biochemical Drug interaction, interaction through which a Medication, drug substance produces its pharmacological effect. A mechanism of action usually includes mention o ...

, confirmation that there is no intellectual property conflict). This is followed by the hit to lead stage of drug discovery, where derivatives of the active compound are produced in an attempt to improve its potency and safety

Safety is the state of being protected from harm or other danger. Safety can also refer to the control of recognized hazards in order to achieve an acceptable level of risk.

Meanings

The word 'safety' entered the English language in the 1 ...

.secondary metabolite

Secondary metabolites, also called ''specialised metabolites'', ''secondary products'', or ''natural products'', are organic compounds produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria, archaea, fungi, animals, or plants, which are not directly involved ...

s with complex chemical structure

A chemical structure of a molecule is a spatial arrangement of its atoms and their chemical bonds. Its determination includes a chemist's specifying the molecular geometry and, when feasible and necessary, the electronic structure of the target m ...

s, their total/semisynthesis is not always commercially viable. In these cases, efforts can be made to design simpler analogues with comparable potency and safety that are amenable to total/semisynthesis.

Prokaryotic

Bacteria

The serendipitous discovery and subsequent clinical success of penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

prompted a large-scale search for other environmental microorganisms

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic size, which may exist in its single-celled form or as a colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen microbial life was suspected from antiquity, with an early attestation in ...

that might produce anti-infective natural products. Soil and water samples were collected from all over the world, leading to the discovery of streptomycin

Streptomycin is an antibiotic medication used to treat a number of bacterial infections, including tuberculosis, Mycobacterium avium complex, ''Mycobacterium avium'' complex, endocarditis, brucellosis, Burkholderia infection, ''Burkholderia'' i ...

(derived from '' Streptomyces griseus''), and the realization that bacteria, not just fungi, represent an important source of pharmacologically active natural products.amphotericin B

Amphotericin B is an antifungal medication used for serious fungal infections and leishmaniasis. The fungal infections it is used to treat include mucormycosis, aspergillosis, blastomycosis, candidiasis, coccidioidomycosis, and cryptococ ...

, chloramphenicol

Chloramphenicol is an antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. This includes use as an eye ointment to treat conjunctivitis. By mouth or by intravenous, injection into a vein, it is used to treat meningitis, pl ...

, daptomycin and tetracycline (from '' Streptomyces'' spp.),Botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxin, or botulinum neurotoxin (commonly called botox), is a neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum'' and related species. It prevents the release of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine from axon en ...

(from ''Clostridium botulinum

''Clostridium botulinum'' is a Gram-positive bacteria, gram-positive, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, Anaerobic organism, anaerobic, endospore, spore-forming, Motility, motile bacterium with the ability to produce botulinum toxin, which is a neurot ...

'') and bleomycin (from '' Streptomyces verticillus'') are two examples. Botulinum, the neurotoxin

Neurotoxins are toxins that are destructive to nervous tissue, nerve tissue (causing neurotoxicity). Neurotoxins are an extensive class of exogenous chemical neurological insult (medical), insultsSpencer 2000 that can adversely affect function ...

responsible for botulism

Botulism is a rare and potentially fatal illness caused by botulinum toxin, which is produced by the bacterium ''Clostridium botulinum''. The disease begins with weakness, blurred vision, Fatigue (medical), feeling tired, and trouble speaking. ...

, can be injected into specific muscles (such as those controlling the eyelid) to prevent muscle spasm

A spasm is a sudden involuntary contraction of a muscle, a group of muscles, or a hollow organ, such as the bladder.

A spasmodic muscle contraction may be caused by many medical conditions, including dystonia. Most commonly, it is a musc ...

.testicular cancer

Testicular cancer is cancer that develops in the testicles, a part of the male reproductive system. Symptoms may include a lump in the testicle or swelling or pain in the scrotum. Treatment may result in infertility.

Risk factors include an c ...

. Newer trends in the field include the metabolic profiling and isolation of natural products from novel bacterial species present in underexplored environments. Examples include symbionts or endophytes from tropical environments,

Archaea

Because many Archaea

Archaea ( ) is a Domain (biology), domain of organisms. Traditionally, Archaea only included its Prokaryote, prokaryotic members, but this has since been found to be paraphyletic, as eukaryotes are known to have evolved from archaea. Even thou ...

have adapted to life in extreme environments such as polar regions, hot springs

A hot spring, hydrothermal spring, or geothermal spring is a Spring (hydrology), spring produced by the emergence of Geothermal activity, geothermally heated groundwater onto the surface of the Earth. The groundwater is heated either by shallow ...

, acidic springs, alkaline springs, salt lakes

A salt lake or saline lake is a landlocked body of water that has a concentration of salts (typically sodium chloride) and other dissolved minerals significantly higher than most lakes (often defined as at least three grams of salt per liter). I ...

, and the high pressure

In science and engineering the study of high pressure examines its effects on materials and the design and construction of devices, such as a diamond anvil cell, which can create high pressure. ''High pressure'' usually means pressures of thousan ...

of deep ocean water, they possess enzymes that are functional under quite unusual conditions. These enzymes are of potential use in the food

Food is any substance consumed by an organism for Nutrient, nutritional support. Food is usually of plant, animal, or Fungus, fungal origin and contains essential nutrients such as carbohydrates, fats, protein (nutrient), proteins, vitamins, ...

, chemical

A chemical substance is a unique form of matter with constant chemical composition and characteristic properties. Chemical substances may take the form of a single element or chemical compounds. If two or more chemical substances can be combin ...

, and pharmaceutical

Medication (also called medicament, medicine, pharmaceutical drug, medicinal product, medicinal drug or simply drug) is a drug used to diagnose, cure, treat, or prevent disease. Drug therapy ( pharmacotherapy) is an important part of the ...

industries, where biotechnological processes frequently involve high temperatures, extremes of pH, high salt concentrations, and / or high pressure. Examples of enzymes identified to date include amylase

An amylase () is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyses the hydrolysis of starch (Latin ') into sugars. Amylase is present in the saliva of humans and some other mammals, where it begins the chemical process of digestion. Foods that contain large ...

s, pullulanases, cyclodextrin glycosyltransferases, cellulase

Cellulase (; systematic name 4-β-D-glucan 4-glucanohydrolase) is any of several enzymes produced chiefly by fungi, bacteria, and protozoans that catalyze cellulolysis, the decomposition of cellulose and of some related polysaccharides:

: Endo ...

s, xylanases, chitinase

Chitinases (, chitodextrinase, 1,4-β-poly-N-acetylglucosaminidase, poly-β-glucosaminidase, β-1,4-poly-N-acetyl glucosamidinase, poly ,4-(N-acetyl-β-D-glucosaminide)glycanohydrolase, (1→4)-2-acetamido-2-deoxy-β-D-glucan glycanohydrola ...

s, protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s, alcohol dehydrogenase

Alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH) () are a group of dehydrogenase enzymes that occur in many organisms and facilitate the interconversion between alcohols and aldehydes or ketones with the reduction of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) to N ...

, and esterase

In biochemistry, an esterase is a class of enzyme that splits esters into an acid and an alcohol in a chemical reaction with water called hydrolysis (and as such, it is a type of hydrolase).

A wide range of different esterases exist that differ ...

s.chemical compounds

A chemical compound is a chemical substance composed of many identical molecules (or molecular entities) containing atoms from more than one chemical element held together by chemical bonds. A molecule consisting of atoms of only one element ...

also, for example isoprenyl glycerol ethers 1 and 2 from '' Thermococcus'' S557 and '' Methanocaldococcus jannaschii'', respectively.

Eukaryotic

Fungi

Several anti-infective medications have been derived from fungi including penicillin and the cephalosporins

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus ''Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibiotic ...

(antibacterial drugs from '' Penicillium rubens'' and '' Cephalosporium acremonium'', respectively)metabolite

In biochemistry, a metabolite is an intermediate or end product of metabolism.

The term is usually used for small molecules. Metabolites have various functions, including fuel, structure, signaling, stimulatory and inhibitory effects on enzymes, c ...

s include lovastatin (from '' Pleurotus ostreatus''), which became a lead for a series of drugs that lower cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

levels, cyclosporin (from '' Tolypocladium inflatum''), which is used to suppress the immune response

An immune response is a physiological reaction which occurs within an organism in the context of inflammation for the purpose of defending against exogenous factors. These include a wide variety of different toxins, viruses, intra- and extracellula ...

after organ transplant

Organ transplantation is a medical procedure in which an organ (anatomy), organ is removed from one body and placed in the body of a recipient, to replace a damaged or missing organ. The donor and recipient may be at the same location, or org ...

operations, and ergometrine (from ''Claviceps

Ergot ( ) or ergot fungi refers to a group of fungi of the genus ''Claviceps''.

The most prominent member of this group is '' Claviceps purpurea'' ("rye ergot fungus"). This fungus grows on rye and related plants, and produces alkaloids that c ...

'' spp.), which acts as a vasoconstrictor, and is used to prevent bleeding after childbirth.neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

thought to be involved in panic attacks, and could potentially be used to treat anxiety

Anxiety is an emotion characterised by an unpleasant state of inner wikt:turmoil, turmoil and includes feelings of dread over Anticipation, anticipated events. Anxiety is different from fear in that fear is defined as the emotional response ...

.

Plants

Plants are a major source of complex and highly structurally diverse chemical compounds (phytochemical

Phytochemicals are naturally-occurring chemicals present in or extracted from plants. Some phytochemicals are nutrients for the plant, while others are metabolites produced to enhance plant survivability and reproduction.

The fields of ext ...

s), this structural diversity attributed in part to the natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the Heredity, heritable traits characteristic of a population over generation ...

of organisms producing potent compounds to deter herbivory

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat n ...

( feeding deterrents).phenol

Phenol (also known as carbolic acid, phenolic acid, or benzenol) is an aromatic organic compound with the molecular formula . It is a white crystalline solid that is volatile and can catch fire.

The molecule consists of a phenyl group () ...

s, polyphenol

Polyphenols () are a large family of naturally occurring phenols. They are abundant in plants and structurally diverse. Polyphenols include phenolic acids, flavonoids, tannic acid, and ellagitannin, some of which have been used historically as ...

s, tannin

Tannins (or tannoids) are a class of astringent, polyphenolic biomolecules that bind to and Precipitation (chemistry), precipitate proteins and various other organic compounds including amino acids and alkaloids. The term ''tannin'' is widel ...

s, terpene

Terpenes () are a class of natural products consisting of compounds with the formula (C5H8)n for n ≥ 2. Terpenes are major biosynthetic building blocks. Comprising more than 30,000 compounds, these unsaturated hydrocarbons are produced predomi ...

s, and alkaloids.anticancer An anticarcinogen (also known as a carcinopreventive agent) is a substance that counteracts the effects of a carcinogen or inhibits the development of cancer. Anticarcinogens are different from anticarcinoma agents (also known as anticancer or ant ...

agents paclitaxel and omacetaxine mepesuccinate (from '' Taxus brevifolia'' and '' Cephalotaxus harringtonii'', respectively),acetylcholinesterase inhibitor

Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors (AChEIs) also often called cholinesterase inhibitors, inhibit the enzyme acetylcholinesterase from breaking down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine into choline and acetate, thereby increasing both the level an ...

galantamine (from '' Galanthus'' spp.), used to treat Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

.morphine

Morphine, formerly also called morphia, is an opiate that is found naturally in opium, a dark brown resin produced by drying the latex of opium poppies (''Papaver somniferum''). It is mainly used as an analgesic (pain medication). There are ...

, cocaine

Cocaine is a tropane alkaloid and central nervous system stimulant, derived primarily from the leaves of two South American coca plants, ''Erythroxylum coca'' and ''Erythroxylum novogranatense, E. novogranatense'', which are cultivated a ...

, quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to ''Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal leg ...

, tubocurarine, muscarine, and nicotine

Nicotine is a natural product, naturally produced alkaloid in the nightshade family of plants (most predominantly in tobacco and ''Duboisia hopwoodii'') and is widely used recreational drug use, recreationally as a stimulant and anxiolytic. As ...

.

Animals

Animals also represent a source of bioactive natural products. In particular, venom

Venom or zootoxin is a type of toxin produced by an animal that is actively delivered through a wound by means of a bite, sting, or similar action. The toxin is delivered through a specially evolved ''venom apparatus'', such as fangs or a sti ...

ous animals such as snakes, spiders, scorpions, caterpillars, bees, wasps, centipedes, ants, toads, and frogs have attracted much attention. This is because venom constituents (peptides, enzymes, nucleotides, lipids, biogenic amines etc.) often have very specific interactions with a macromolecular target in the body (e.g. α-bungarotoxin from cobra

COBRA or Cobra, often stylized as CoBrA, was a European avant-garde art group active from 1948 to 1951. The name was coined in 1948 by Christian Dotremont from the initials of the members' home countries' capital cities: Copenhagen (Co), Brussels ...

s).ion channel

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by Gating (electrophysiol ...

s, and enzymes. In some cases, they have also served as leads in the development of novel drugs. For example, teprotide, a peptide isolated from the venom of the Brazilian pit viper '' Bothrops jararaca'', was a lead in the development of the antihypertensive agents cilazapril and captopril

Captopril, sold under the brand name Capoten among others, is an ACE inhibitor, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor used for the treatment of hypertension and some types of congestive heart failure. Captopril was the first oral ACE inh ...

.disintegrin

Disintegrins are a family of small proteins (45–84 amino acids in length) from viper venoms that function as potent inhibitors of both platelet aggregation and integrin-dependent cell adhesion.

Operation

Disintegrins work by countering th ...

from the venom of the saw-scaled viper '' Echis carinatus'' was a lead in the development of the antiplatelet drug tirofiban.terrestrial animal

Terrestrial animals are animals that live predominantly or entirely on land (e.g. cats, chickens, ants, most spiders), as compared with aquatic animals, which live predominantly or entirely in the water (e.g. fish, lobsters, octopuses), ...

s and amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s described above, many marine animals have been examined for pharmacologically active natural products, with coral

Corals are colonial marine invertebrates within the subphylum Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact Colony (biology), colonies of many identical individual polyp (zoology), polyps. Coral species include the important Coral ...

s, sponges

Sponges or sea sponges are primarily marine invertebrates of the animal phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), a basal clade and a sister taxon of the diploblasts. They are sessile filter feeders that are bound to the seabed, and ar ...

, tunicate

Tunicates are marine invertebrates belonging to the subphylum Tunicata ( ). This grouping is part of the Chordata, a phylum which includes all animals with dorsal nerve cords and notochords (including vertebrates). The subphylum was at one time ...

s, sea snail

Sea snails are slow-moving marine (ocean), marine gastropod Mollusca, molluscs, usually with visible external shells, such as whelk or abalone. They share the Taxonomic classification, taxonomic class Gastropoda with slugs, which are distinguishe ...

s, and bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic animal, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary Colony (biology), colonies. Typically about long, they have a spe ...

ns yielding chemicals with interesting analgesic

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic, antalgic, pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used for pain management. Analgesics are conceptually distinct from anesthetics, which temporarily reduce, and in s ...

, antiviral, and anticancer An anticarcinogen (also known as a carcinopreventive agent) is a substance that counteracts the effects of a carcinogen or inhibits the development of cancer. Anticarcinogens are different from anticarcinoma agents (also known as anticancer or ant ...

activities.

Medical uses

Natural products sometimes have pharmacological activity that can be of therapeutic benefit in treating diseases.drug discovery

In the fields of medicine, biotechnology, and pharmacology, drug discovery is the process by which new candidate medications are discovered.

Historically, drugs were discovered by identifying the active ingredient from traditional remedies or ...

. Natural product constituents have inspired numerous drug discovery efforts that eventually gained approval as new drugs.

Modern natural product-derived drugs

Many prescribed drugs have been either directly derived from or inspired by natural products.willow

Willows, also called sallows and osiers, of the genus ''Salix'', comprise around 350 species (plus numerous hybrids) of typically deciduous trees and shrubs, found primarily on moist soils in cold and temperate regions.

Most species are known ...

tree has been known since antiquity to have pain-relieving properties due to the natural product salicin

Salicin is an alcoholic β-glucoside. Salicin is produced in (and named after) willow (''Salix'') bark. It is a biosynthetic precursor to salicylaldehyde.

Salicin hydrolyses into Glucose, β-d-glucose and salicyl alcohol (saligenin). Salicyl al ...

, which in turn may be hydrolyzed into salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H4COOH. A colorless (or white), bitter-tasting solid, it is a precursor to and a active metabolite, metabolite of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin). It is a plant hormone, and has been lis ...

. A synthetic derivative acetylsalicylic acid

Aspirin () is the Generic trademark, genericized trademark for acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions ...

better known as ''aspirin

Aspirin () is the genericized trademark for acetylsalicylic acid (ASA), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to reduce pain, fever, and inflammation, and as an antithrombotic. Specific inflammatory conditions that aspirin is ...

'' is a widely used pain reliever. Its mechanism of action is inhibition of the cyclooxygenase

Cyclooxygenase (COX), officially known as prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase (PTGS), is an enzyme (specifically, a family of isozymes, ) that is responsible for biosynthesis of prostanoids, including thromboxane and prostaglandins such a ...

(COX) enzyme.opium

Opium (also known as poppy tears, or Lachryma papaveris) is the dried latex obtained from the seed Capsule (fruit), capsules of the opium poppy ''Papaver somniferum''. Approximately 12 percent of opium is made up of the analgesic alkaloid mor ...

extracted from the latex of ''Papaver somniferous'' (a flowering poppy plant). The most potent narcotic component of opium is the alkaloid morphine, which acts as an opioid receptor agonist.N-type calcium channel

N-type calcium channels, also called Cav2.2 channels, are voltage gated calcium channels that are localized primarily on the nerve terminals and dendrites as well as neuroendocrine cells. The calcium N-channel consists of several subunits: the prim ...

blocker ziconotide

Ziconotide, sold under the brand name Prialt, also called intrathecal ziconotide (ITZ) because of its administration route, is an atypical analgesic agent for the amelioration of severe and chronic pain. Derived from '' Conus magus'', a cone sn ...

is an analgesic based on a cyclic peptide cone snail toxin (ω- conotoxin MVIIA) from the species ''Conus magus''.Penicillium