The Jiajing Emperor (16September 150723January 1567), also known by his

temple name

Temple names are posthumous titles accorded to monarchs of the Sinosphere for the purpose of ancestor worship. The practice of honoring monarchs with temple names began during the Shang dynasty in China and had since been adopted by other dynas ...

as the Emperor Shizong of Ming, personal name Zhu Houcong,

art names Yaozhai, Leixuan, and Tianchi Diaosou, was the 12th

emperor

The word ''emperor'' (from , via ) can mean the male ruler of an empire. ''Empress'', the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), mother/grandmother (empress dowager/grand empress dowager), or a woman who rules ...

of the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

, reigning from 1521 to 1567. He succeeded his cousin, the

Zhengde Emperor

The Zhengde Emperor (26 October 149120 April 1521), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Wuzong of Ming, personal name Zhu Houzhao, was the 11th List of emperors of the Ming dynasty, emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1505 to 1 ...

.

The Jiajing Emperor was born as a cousin of the reigning Zhengde Emperor, so his accession to the throne was unexpected, but when the Zhengde Emperor died without an heir, the government, led by Senior Grand Secretary

Yang Tinghe and

Empress Dowager Zhang, chose him as the new ruler. After his enthronement, a dispute arose between the emperor and his officials regarding the method of legalizing his accession. This conflict, known as the

Great Rites Controversy, was a significant political issue at the beginning of his reign. After three years, the emperor emerged victorious, with his main opponents either banished from court or executed.

The Jiajing Emperor, like the Zhengde Emperor, made the decision to reside outside of Beijing's

Forbidden City

The Forbidden City () is the Chinese Empire, imperial Chinese palace, palace complex in the center of the Imperial City, Beijing, Imperial City in Beijing, China. It was the residence of 24 Ming dynasty, Ming and Qing dynasty, Qing dynasty L ...

. In 1542, he relocated to the

West Park, located in the middle of Beijing and west of the Forbidden City. He constructed a complex of palaces and Taoist temples in the West Park, drawing inspiration from the Taoist belief of the

Land of Immortals. Within the West Park, he surrounded himself with a group of loyal eunuchs, Taoist monks, and trusted advisers (including grand secretaries and ministers of rites) who assisted him in managing the state bureaucracy.

Zhang Cong,

Xia Yan,

Yan Song, and

Xu Jie each held senior roles in his government. In his later years, the emperor's pursuit of immortality led to questionable actions, such as his interest in young girls and alchemy. He even sent Taoist priests across the land to collect rare minerals for life-extending potions. These elixirs contained harmful substances like

arsenic

Arsenic is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol As and atomic number 33. It is a metalloid and one of the pnictogens, and therefore shares many properties with its group 15 neighbors phosphorus and antimony. Arsenic is not ...

, lead, and

mercury, which ultimately caused health problems and may have shortened the emperor's life.

At the start of the Jiajing era, the borders were relatively peaceful. In the north, the Mongols were initially embroiled in internal conflicts, but after being united by

Altan Khan in the 1540s, they began to demand the restoration of free trade. The emperor, however, refused and attempted to close the borders with fortifications, including the

Great Wall of China

The Great Wall of China (, literally "ten thousand ''li'' long wall") is a series of fortifications in China. They were built across the historical northern borders of ancient Chinese states and Imperial China as protection against vario ...

. In response, Altan Khan launched raids and even attacked the outskirts of Beijing in 1550. The Ming troops were forced to focus on defense. Meanwhile, ''

Wokou

''Wokou'' ( zh, c=, p=Wōkòu; ; Hepburn romanization, Hepburn: ; ; literal Chinese translation: "dwarf bandits"), which translates to "Japanese pirates", were pirates who raided the coastlines of China and Korea from the 13th century to the 17 ...

'' pirates posed a significant threat in southeastern China for several decades. The Ming authorities attempted to address this issue by implementing stricter

laws against private overseas trade in the 1520s, but piracy and related violence continued to escalate throughout the 1540s and reached its peak in the 1550s. These issues were not resolved until the Jiajing Emperor's son and successor, the

Longqing Emperor, allowed foreign trade to resume. Despite the trade restrictions imposed by the Jiajing government and the incidence of the

1556 Shaanxi earthquake

The 1556 Shaanxi earthquake ( Postal romanization: ''Shensi''), known in Chinese colloquially by its regnal year as the Jiajing Great Earthquake "" ('' Jiājìng Dàdìzhèn'') or officially by its epicenter as the Hua County Earthquake "" ('' ...

in northern China–the deadliest earthquake in human history, the economy continued to develop, with growth in agriculture, industry, and trade. As the economy flourished, so did society, with the traditional Confucian interpretation of

Zhuism giving way to

Wang Yangming

Wang Shouren (, 26 October 1472 – 9 January 1529), courtesy name Bo'an (), art name Yangmingzi (), usually referred to as Wang Yangming (), was a Chinese statesman, general, and Neo-Confucian philosopher during the Ming dynasty. After Zhu ...

's more individualistic beliefs.

Childhood

Zhu Houcong, the future Jiajing Emperor, was born on 16 September 1507. He was the eldest son of

Zhu Youyuan

Zhu Youyuan (22 July 1476 – 13 July 1519), was a prince of the Ming dynasty of China. He was the fourth son of the Chenghua Emperor and father of the Jiajing Emperor.

Zhu Youyuan was the fourth son of the Chenghua Emperor, the ninth empe ...

, who was Prince of Xing from 1487. Zhu Youyuan was the fourth son of the

Chenghua Emperor

The Chenghua Emperor (9 December 1447 – 9 September 1487), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Xianzong of Ming, personal name Zhu Jianshen, changed to Zhu Jianru in 1457, was the ninth emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1464 ...

, who ruled the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty, officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 1368 to 1644, following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming was the last imperial dynasty of ...

from 1464 to 1487. His mother, Lady Shao, was one of the emperor's concubines. Zhu Houcong's mother, surnamed Jiang, was the daughter of Jiang Xiao of

Daxing in

North Zhili

Beizhili, formerly romanized as , Pechili, Peichili, etc. and also known as North or Northern Zhili or Chih-li, was a historical province of the Ming Empire. Its capital was Beijing, from which it is also sometimes known as Beijing or Peking Pr ...

. Jiang Xiao was an officer of the Beijing garrison. Zhu Houcong's parents from 1494 lived in Anlu ''

zhou'' (present-day

Zhongxiang

Zhongxiang () is a county-level city of Jingmen, central Hubei province, People's Republic of China. The name ''Zhongxiang'' means "Blessed with propitious omen", and was given to the city by the Jiajing Emperor in the Ming dynasty.

History

Zhong ...

) in Huguang in central China, where Zhu Houcong was born. His father, Zhu Youyuan, was known for his poetry and

calligraphy

Calligraphy () is a visual art related to writing. It is the design and execution of lettering with a pen, ink brush, or other writing instruments. Contemporary calligraphic practice can be defined as "the art of giving form to signs in an e ...

.

Zhu Houcong received a classical (

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

) education directly from his father, to whom he was a diligent and attentive student. However, in July 1519, his father died. Afterward, Zhu Houcong took on the responsibility of managing the household with the assistance of Yuan Zonggao, a capable administrator who later became a trusted advisor after Zhu Houcong's ascension to the throne in Beijing. Following the traditional period of mourning for his father's death, Zhu Houcong officially became the Prince of Xing in late March 1521.

Beginning of reign

Accession

Meanwhile, in Beijing, the

Zhengde Emperor

The Zhengde Emperor (26 October 149120 April 1521), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Wuzong of Ming, personal name Zhu Houzhao, was the 11th List of emperors of the Ming dynasty, emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1505 to 1 ...

() fell ill and died on 20 April 1521. His father, the

Hongzhi Emperor (), was the older brother of Zhu Youyuan. Zhu Houcong was the Zhengde Emperor's closest male relative.

Before the Zhengde Emperor died, Grand Secretary

Yang Tinghe, who was effectively leading the Ming government, had already begun preparations for the accession of Zhu Houcong. Five days prior to the Zhengde Emperor's death, an edict was issued ordering Zhu Houcong to end his mourning and officially assume the title of Prince of Xing. On the day of the emperor's death, Yang Tinghe, with the support of eunuchs from the Directorate of Ceremonial in the

Forbidden City

The Forbidden City () is the Chinese Empire, imperial Chinese palace, palace complex in the center of the Imperial City, Beijing, Imperial City in Beijing, China. It was the residence of 24 Ming dynasty, Ming and Qing dynasty, Qing dynasty L ...

and

Empress Dowager Zhang (the late emperor's mother), issued an edict calling for the prince to arrive in Beijing and ascend the throne.

However, there was uncertainty surrounding this matter due to the Ming succession law. According to this law, although Ming emperors were allowed to have multiple wives, only the sons of the empress had the right to succeed to the throne. Any attempt to install a descendant of a concubine was punishable by death. Zhu Houcong's father, Zhu Youyuan, was not the son of the empress, but rather of a concubine. Therefore, he had no legitimate claim to the throne. In order to circumvent this issue, Yang Tinghe proposed adopting Zhu Houcong as the Hongzhi Emperor's son, so he could ascend as the late emperor's younger brother.

In addition, there were many favorites of the deceased emperor living in Beijing who were afraid of changes. The most influential among them was General

Jiang Bin, the commander of the border troops who had been transferred to Beijing. It was feared that he would try to install his own candidate for the throne, Zhu Junzhang (), Prince of Dai, who was based in the border city of

Datong

Datong is a prefecture-level city in northern Shanxi Province, China. It is located in the Datong Basin at an elevation of and borders Inner Mongolia to the north and west and Hebei to the east. As of the 2020 census, it had a population o ...

.

The day after the Zhengde Emperor's death, a delegation of high-ranking dignitaries left Beijing for Anlu to inform Zhu Houcong of the situation. They arrived in Anlu on 2 May. Zhu Houcong accepted them, familiarized himself with the edict of Empress Dowager Zhang, and agreed to ascend the throne. On 7 May, he set out for Beijing accompanied by forty of his own advisers and servants. Yang Tinghe issued orders for him to be welcomed in Beijing as the heir to the throne, but Zhu Houcong refused to appear as the heir apparent, stating that he was invited to assume the imperial rank and was therefore the emperor, not the son of the emperor. According to the grand secretaries and the government, he was the son of the Hongzhi Emperor. He forced his way into the city with imperial honors and on the same day, 27 May 1521, he ceremoniously ascended the throne. The young emperor reportedly chose the name of his era himself, from his favorite chapter of the ''

Book of Documents

The ''Book of Documents'' ( zh, p=Shūjīng, c=書經, w=Shu King) or the ''Classic of History'', is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a collection of rhetorical prose attributed to figures of ancient China, a ...

'', with ''jia'' meaning "to improve, make splendid" and ''jing'' meaning "to pacify" in Chinese.

The proposal for the era name Shaozhi (Continuation of proper governance) by the grand secretaries was rejected by the Jiajing Emperor. Shaozhi was a summary of the government's call for the new emperor to take the throne and follow the policies and rituals set by the founder of the dynasty in order to ensure proper governance. This expressed a desire for continuity in rule. The era name Jiajing means "admirable and tranquility" and is derived from a passage in the ''Book of Documents'', in which the

Duke of Zhou

Dan, Duke Wen of Zhou, commonly known as the Duke of Zhou, was a member of the royal family of the early Zhou dynasty who played a major role in consolidating the kingdom established by his elder brother King Wu. He was renowned for acting as ...

admonishes the young

King Cheng and praises King

Wu Ding of the

Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty that ruled in the Yellow River valley during the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty and followed by the Western Zhou d ...

for his admirable and tranquil leadership. Wu Ding was commended for restoring the fallen prestige of the Shang dynasty not through force, but through the radiance of his virtue. Therefore, the era name Jiajing can be seen as a criticism of the state of the country and the Zhengde government, as well as a declaration of a policy of change and restoration.

King Wen, the father of the founder of the Zhou dynasty,

King Wu, is also contrasted with the unworthy last Shang king,

Zhou. The Jiajing Emperor saw a parallel between King Wen, between Zhou and Wu, and between his noble father, the unworthy Zhengde Emperor, and himself. Therefore, he judged that he did not owe the throne to the grand secretaries, ministers, or the empress dowager, but to the virtues of his father recognized by the Heavens. This was the basis of his respect for his parents and his rejection of adoption in the

Great Rites Controversy.

Great Rites Controversy

The new emperor's primary desire was to posthumously elevate his father to the imperial rank. In contrast, Yang Tinghe insisted on his formal adoption by the Hongzhi Emperor, in order to legitimize his claim to the throne and become the younger brother of the late Zhengde Emperor. The Jiajing Emperor and his mother rejected the adoption, citing the wording of the recall decree which did not mention it. The emperor did not want to declare his parents as his uncle and aunt. Instead, he requested the elevation of his parents to the imperial status "to bring their ranks into line".

Most officials agreed to maintain a direct line of succession and supported Yang Tinghe, but the emperor argued for the duty to his biological parents. He insisted on his mother's acceptance as empress dowager when she arrived from Anlu and entered the Forbidden City on 2 November. A group of officials siding with the emperor, led by

Zhang Cong, had already formed. In late 1521, the emperor succeeded in having his parents and grandmother, Lady Shao, granted imperial rank. However, disputes continued until Yang was forced to resign in March 1524, and the removal of the emperor's opponents began in August 1524. After a disapproving demonstration by hundreds of opposing officials in front of the gates of the audience hall, the opposition was beaten at court. 17 officials died from their wounds, and the rest were exiled to the provinces by the emperor.

During the dispute, the Jiajing Emperor asserted his independence from the grand secretaries and made decisions based on his own judgment, rather than consulting with them or simply approving their proposals. This was seen as a despotic approach that went against the traditional way of governing, and was criticized by concerned scholars. As a result of the dispute, the teachings of Confucian scholar and reformer

Wang Yangming

Wang Shouren (, 26 October 1472 – 9 January 1529), courtesy name Bo'an (), art name Yangmingzi (), usually referred to as Wang Yangming (), was a Chinese statesman, general, and Neo-Confucian philosopher during the Ming dynasty. After Zhu ...

gained popularity, as some of the emperor's followers were influenced by his arguments. Additionally, there was an increase in critical analysis and interpretation of texts during discussions, and there was a growing criticism of the conservative attitudes of the

Hanlin Academy

The Hanlin Academy was an academic and administrative institution of higher learning founded in the 8th century Tang China by Emperor Xuanzong in Chang'an. It has also been translated as "College of Literature" and "Academy of the Forest of Pen ...

.

Honoring parents and legitimizing the government

In 1530, the Jiajing Emperor published the biography of

Empress Ma, the ''Gao huanghou chuan'' (), and the ''Household Instructions'' of

Empress Xu under the title ''Nüxun'' (; 'Instructions for women', in 12 volumes). The work was attributed to the emperor's mother. Empress Ma was the wife of the

Hongwu Emperor

The Hongwu Emperor (21 October 1328– 24 June 1398), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Taizu of Ming, personal name Zhu Yuanzhang, courtesy name Guorui, was the List of emperors of the Ming dynasty, founding emperor of the Ming dyna ...

, the founder of the dynasty, and Empress Xu was the wife of the

Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Chengzu of Ming, personal name Zhu Di, was the third List of emperors of the Ming dynasty, emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 142 ...

, the first monarch in the new branch of the dynasty. Additionally, the emperor changed the Yongle Emperor's temple name from "Taizong" to "Chengzu". The Jiajing Emperor's interest in the Yongle Emperor was rooted in his desire to establish a new branch of the dynasty.

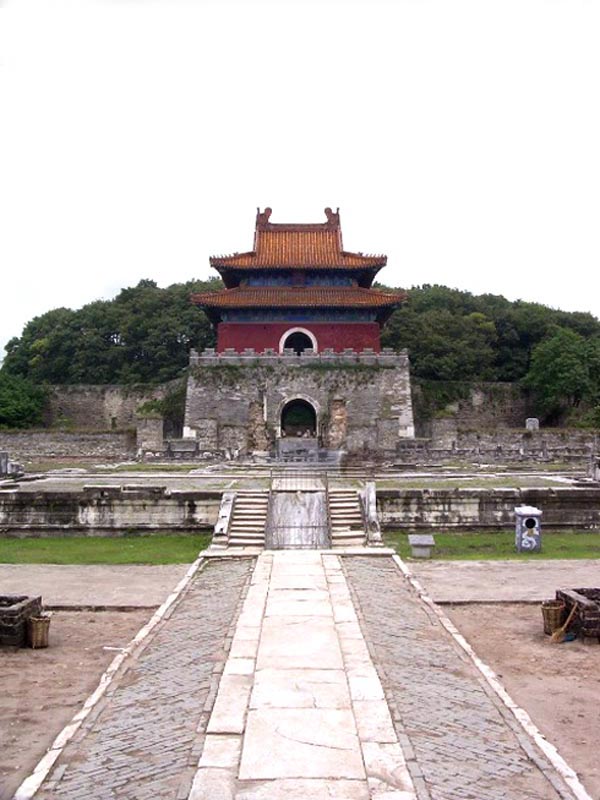

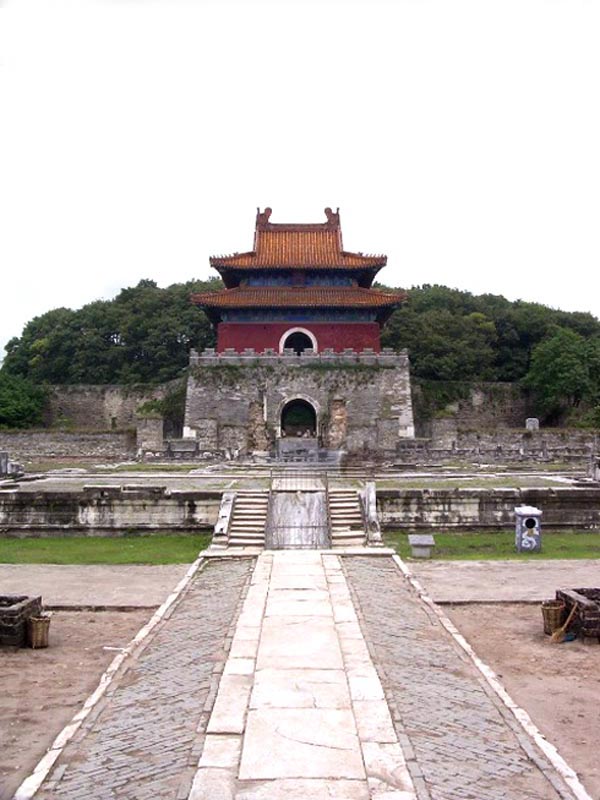

The emperor suggested transferring his father's remains from the mausoleum in Huguang to the vicinity of the imperial burial ground near Beijing, but in the end, only a shrine was created for his father in the palace. The emperor also took steps to honor his ancestors, such as restoring ancestral temples, giving his parents longer titles, and supervising rituals and ritual music. After his mother's death in December 1538, the emperor traveled south to Anlu to resolve the question of whether to bury his parents together in the south or in Beijing. He ultimately chose to bury his mother in his father's mausoleum near

Zhongxiang

Zhongxiang () is a county-level city of Jingmen, central Hubei province, People's Republic of China. The name ''Zhongxiang'' means "Blessed with propitious omen", and was given to the city by the Jiajing Emperor in the Ming dynasty.

History

Zhong ...

. He also honored his father by publishing the latter's ''

Veritable Records'' (''Shilu'') and renamed Anlu ''zhou'' to Chengtian Prefecture (, ''Chengtian Fu'') after the example of the imperial capitals.

During his journey to Anlu, the Jiajing Emperor was shocked by the sight of starving and impoverished people and refugees. He immediately released 20 thousand ''liang'' (746 kg) of silver for relief. He saw their suffering as a failure of his ceremonial and administrative reforms. Two years later, during

civil service examinations, he asked candidates why there was still poverty in the country despite his efforts to faithfully follow Confucian teachings and observe ceremonies.

Further ceremony reforms

After successfully resolving the Great Rites Controversy, the emperor proceeded to make changes to other rituals and ceremonies, despite facing opposition from some officials. These changes primarily affected the rites performed by the monarch. In the late 1530s, separate sacrifices to the Heavens, Earth, Sun, and Moon were introduced.

Additionally, the Jiajing Emperor altered the titles and forms of honoring

Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

, including a ban on images in Confucian temples, leaving only plaques with the names of Confucius and his followers. The layout of the Temple of Confucius was also modified to include separate chapels for Confucius' father and three disciples. As part of these changes, Confucius was stripped of his title of king by the Jiajing Emperor, who believed that the emperor should not bow to a king. Furthermore, the emperor did not want Confucius to be worshipped in the same rituals used for imperial sacrifices to the Heavens. As a result, the ceremonies in the Temple of Confucius were simplified and no longer resembled imperial sacrifices.

In addition, sacrifices to former emperors and kings were separated from the imperial sacrifices to the Heavens, and a special temple was built for them. This elevated the status of the monarch, as his rites were now distinct from all others. From the years 1532–1533, the Jiajing Emperor lost interest in ritual reforms and the worship of Heaven, as he was no longer able to elevate his own or his father's status. This led to a decline in the importance of ceremonies during his reign.

Government

Eunuchs

Important positions in the imperial palace were filled by eunuchs brought from Anlu by the Jiajing Emperor. As part of the dismissal of eunuchs associated with the previous monarch, some eunuch posts in the provinces were eliminated. However, the overall influence of eunuchs did not decrease; in fact, it continued to grow. By the 1530s, the most influential eunuchs saw themselves as equal to the grand secretaries. In 1548–1549, the roles of the head of the Eastern Depot and the Directorate of Ceremonial were combined, and the palace guard (established in 1552 and composed of eunuchs) was also under their control. This effectively placed the entire eunuch branch of state administration under their management.

Grand secretaries

After 1524, the emperor's closest advisers were Zhang Cong and

Gui E. They attempted to remove followers of Yang Tinghe, who were associated with the Hanlin Academy, from influential positions. This resulted in a purge of the Beijing authorities in 1527–1528 and a significant change in personnel at the academy. In addition, Zhang Cong and Gui E worked to limit the influence of Senior Grand Secretary,

Fei Hong, in the Grand Secretariat. To achieve this, they brought back

Yang Yiqing, who had previously served in the Grand Secretariat in 1515–1516. In the following years, there was a power struggle between the grand secretaries and their associated groups of officials. The position of senior grand secretary was constantly changing, with Fei, Yang, Zhang, and others taking turns.

In the early 1530s, the Jiajing Emperor's trust was won by

Xia Yan, who had been promoted from minister of rites to grand secretary. Later, in the late 1530s,

Yan Song, Xia Yan's successor in the ministry, also gained the emperor's trust. However, although Xia Yan initially supported Yan Song's rise, he eventually came into conflict with Yan. In 1542, Yan was able to oust Xia and take control of the Grand Secretariat. In an attempt to counterbalance Yan's influence, the emperor called Xia back to lead the Grand Secretariat in October 1545. However, the two statesmen were at odds, with Xia ignoring Yan, refusing to consult him, and canceling his appointment. As a result, the emperor grew distant from Xia, partly due to his reserved attitude towards Taoist rituals and prayers. In contrast, Yan strongly supported the emperor's interest in Taoism. In February 1548, Xia supported a campaign to Ordos without informing Yan, making him solely responsible for it. When the emperor withdrew his support for the campaign due to unfavorable omens and reports of discontent in the neighboring province of

Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

, enemies of Xia, including Yan, used this as an opportunity to bring charges against him and have him executed.

From 1549 to 1562, the Grand Secretariat was under Yan Song's control. He was known for his attentiveness and diligence towards the monarch, but also for pushing his colleagues out of power. Despite facing numerous political crises and challenges, Yan managed to survive by delegating decisions and responsibilities to the appropriate ministries and authorities. For example, the Ministry of Rites was responsible for dealing with the Mongols, while the Ministry of War handled their expulsion. However, Yan avoided getting involved in the government's biggest issue at the time—state finances—leaving it to the Ministries of Revenue and Works. He only maintained control over personnel matters and selected political issues. Despite facing criticism for corruption and selling offices, Yan was able to convince the emperor that these were false accusations and that his critics were simply trying to remove him from power. The emperor, who was always suspicious of officials, believed Yan's defense.

Yan, who was already 80 years old in 1560, was unable to continue his role as grand secretary. This was especially true after his wife died in 1561 and his son, who had been assisting him with writing edicts, went home to organize the funeral. To make matters worse, he faced opposition from his subordinate, Grand Secretary

Xu Jie. As a result, the emperor no longer relied on Yan and dismissed him in June 1562. Xu Jie then took over as the head of the Grand Secretariat.

With the personnel changes in the immediate surroundings of the emperor, the focus and style of his policies also shifted. During the first phase of his reign, the Jiajing Emperor placed great importance on ceremonies, which were seen as essential in maintaining order and promoting a sense of superiority over non-Chinese peoples, according to Confucian beliefs. The refinement and organization of these ceremonies aimed to showcase the Ming dynasty as a model for surrounding countries and the world. The emperor received significant assistance from his senior grand secretary, Zhang Cong. However, during Xia Yan's dominance in the Grand Secretariat, the emperor withdrew from the Forbidden City to the

West Park, neglecting his public duties but still maintaining control over the government. During this time, Ming China used military force to intimidate neighboring countries, successfully in the case of Đại Việt, but falling in the attempt to recapture Ordos, resulting in Xia's death in 1548. In the following period, during the conflicts of the 1550s in the north and on the coast, Yan Song pursued a policy of compromise and negotiation, which was accompanied by corruption. After the fall of Yan Song in 1562, the emperor's interest in good governance was rekindled under the influence of the capable and energetic grand secretary, Xu Jie. Thus, the Jiajing Emperor's rule after the overthrow of Yang Tinghe can be divided into four phases: Zhang Cong's strict adherence to ideology, Xia Yan's aggressive expansionism, Yan Song's complacent corruption, and Xu Jie's corrective reforms.

Organization of the government

One important aspect of the decision-making process since the beginning of the Ming dynasty had been the system of interdepartmental consultation among high officials. Memoranda and proposals were submitted for debate to the "

nine ministers The Nine Ministers or Nine Chamberlains () was the collective name for nine high officials in the imperial government of the Han dynasty (206 BC–220 AD), who each headed one of the Nine Courts and were subordinates to the Three Councillors o ...

", as well as to generals of the Central Military Commissions and other officials. The result of these discussions was then presented to the emperor for a final decision. The grand secretaries were responsible for organizing the circulation of these memoranda but did not have the authority to make decisions. The Jiajing Emperor emphasized the importance of discussing important decisions at court and encouraged officials to express their opinions, particularly in the case of high-ranking government officials, to the obligee.

In the early Ming period, this system often served to justify the decisions of the emperors (especially after

the crisis of 1380), as there was no social basis for diverse attitudes, but as the crises of the mid-15th century emerged, the situation changed, and the need for political changes became apparent. The emergence of officials with merchant-family backgrounds also provided a basis for assessing problems from different perspectives. Officials used this system to debate, build support networks, lobby for their own interests, push opponents out of office, and sometimes even sabotage their policies.

Assassination attempts and relocation to the West Park

The emperor's harsh treatment of dissenters earned him many opponents and led to multiple attempts on his life. In 1539, while traveling to Anlu, his temporary residences were repeatedly set on fire. The most serious incident occurred on 27 November 1542, when a group of

palace women attempted to strangle him. When the emperor had fallen asleep in one of his concubines' quarters, a serving girl led several palace women to start strangling him with a silk cord. However, one of the palace women panicked and alerted the eunuchs, who then informed

Empress Fang. The emperor eventually woke up after being unconscious for eight hours but was unable to speak. Empress Fang ordered the execution of all women involved in the assassination attempt, both those who were actually involved and those who were falsely accused. The motives of the palace women are unclear, but possibly the emperor's cruel treatment towards them, driven by his pursuit of a longer life, may have played a role.

After the assassination attempt, the Jiajing Emperor completely withdrew from the formal life of the court and the Forbidden City. He moved to the Yongshou Palace (Palace of Eternal Life) in the West Park of the Imperial City, where he occasionally stayed starting in 1539.

The West Park was located in the western third of the Imperial City, separated from it and the Forbidden City by a system of three lakes called

Taiye Lake. These lakes stretched over two kilometers from north to south and occupied half of the park's area. The emperor built West Park to be a complex where he could live and seek immortality. Since the beginning of the Ming dynasty, West Park has been seen as a symbol of the Lands of Immortals. The Jiajing Emperor, who was fascinated by Taoism and the concept of immortality, was intrigued by this and attempted to reconstruct the site in accordance with contemporary beliefs about the Lands of Immortals. He aligned the names of the palaces and the attire of the servants and officials with Taoist symbolism, and Taoist ceremonies were performed there. Animals were also kept, and plants were grown for divination purposes. After the emperor's death, most of the buildings he had constructed were demolished, leaving only one temple, Dagaoxian dian, which still stands today.

After 1542, the emperor never resided in his palace in the Forbidden City. This relocation to the West Park also resulted in the transfer of the administrative center of the empire, further isolating the emperor from the bureaucracy. In fact, as early as 1534, he ceased holding imperial audiences. Instead, his decisions were conveyed to the ministries and other authorities through a select group of advisors who had direct access to him. This group included the grand secretaries, the minister of rites, and several military commanders. However, the discontinuation of audiences did not indicate a lack of interest in governing; the emperor diligently read reports and submissions from officials and often worked late into the night.

Taoist pursuits

From the beginning of his reign, the Jiajing Emperor was drawn to the Taoist faith, with its focus on supernaturalism and the pursuit of immortality. This may have been influenced by his childhood spent in Huguang, whose people were known for their superstitious beliefs. However, the Jiajing Emperor's support of Taoism was not without limits. In 1527, ministers and grand secretaries Gui E, Fang Xianfu (), Yang Yiqing, and Huo Tao () proposed stricter regulations for the establishment of new Taoist and Buddhist temples and monasteries. They also suggested the abolition of nunneries and temples, the confiscation of their property, and the return of Buddhist and Taoist nuns and priests to secular life. The emperor signed the decree that was prepared. As the emperor had no heir in the first ten years of his reign, some high-ranking officials suggested that Taoist prayers and rituals could solve the problem. This piqued his interest, which only intensified after the assassination in 1542.

The Jiajing Emperor spared no expense or time for Taoist ceremonies. The Taoists requested, among other things, tens of kilograms of gold dust for their prayers. The emperor even had temples built for them, which required a lot of wood to be transported from distant

Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

. Additionally, he gave them valuable items. Among the Taoists, Shao Yuanjie () was particularly favored by the emperor starting in 1526. Shao was known for his prayers for rain and protection against calamities. After the births of the emperor's eldest sons (the first died young in 1533, and the second was born in 1536), he was highly honored. Shao died in 1539 and was replaced by Tao Zhongwen (). Tao Zhongwen further strengthened the emperor's faith in Taoism and gained respect for himself by accurately predicting a fire on the way south to Anlu. In order to prolong the emperor's life, Tao offered him aphrodisiacs and elixirs of immortality made from surite and arsenic. In September 1540, the emperor announced his plans to withdraw into private life in the coming years to seek immortality. This caused great concern among officials, who criticized the preparations as toxic. Those who openly criticized the emperor were executed, and in the following decades, he slowly consumed the elixirs.

After 1545, the emperor began to rely on oracles for guidance in state affairs. These oracles were organized by Tao Zhongwen, who had control over their results. Yan Song also participated in divination, seeing it as an opportunity to influence politics in a favorable direction. The emperor's pursuit of immortality included engaging in sexual relations with young girls, of which he and Tao collected 960 for this purpose. He also called on officials throughout the country to search for and send magical herbs. After Tao's death in November 1560, the emperor struggled to find a Taoist adept who could meet his needs.

In addition to Taoist prayers, the literary form of ''qingci'' (), a poetic style of prayer full of allusions, was revived and developed. The emperor's favor with officials was often based on their skill in writing in this style, rather than their statesmanship. Yan Song and Xia Yan, who were particularly skilled in this style, were often referred to contemptuously as ''qingci zaixiang'' (; 'Qingci premiers').

Economy

Natural disasters and the economy

During the reign of the Jiajing Emperor, the climate was cooler and wetter compared to previous years, but towards the end of his reign, there were warmer winters. Temperatures were 1.5 degrees lower than in the second half of the 20th century. The south and north of China were affected by floods, while the

Yangtze River

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ) is the longest river in Eurasia and the third-longest in the world. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau and flows including Dam Qu River the longest source of the Yangtze, i ...

basin experienced severe drought. In 1528, the worst drought of the entire Ming era hit

Zhejiang

)

, translit_lang1_type2 =

, translit_lang1_info2 = ( Hangzhounese) ( Ningbonese) (Wenzhounese)

, image_skyline = 玉甑峰全貌 - panoramio.jpg

, image_caption = View of the Yandang Mountains

, image_map = Zhejiang i ...

,

Shanxi

Shanxi; Chinese postal romanization, formerly romanised as Shansi is a Provinces of China, province in North China. Its capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-level cities are Changzhi a ...

,

Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

, and

Hubei

Hubei is a province of China, province in Central China. It has the List of Chinese provincial-level divisions by GDP, seventh-largest economy among Chinese provinces, the second-largest within Central China, and the third-largest among inland ...

, resulting in the death of half of the population in some areas of

Henan

Henan; alternatively Honan is a province in Central China. Henan is home to many heritage sites, including Yinxu, the ruins of the final capital of the Shang dynasty () and the Shaolin Temple. Four of the historical capitals of China, Lu ...

and

Jiangnan

Jiangnan is a geographic area in China referring to lands immediately to the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including the southern part of its delta. The region encompasses the city of Shanghai, the southern part of Jiangsu ...

. Jiangnan continued to suffer from droughts, epidemics, rains, and famines until the late 1540s.

Earthquakes were also a frequent occurrence in the Jiajing era, with many recorded in various areas. For instance, in the span of ten months from July 1523 to May 1524, there were 38 recorded earthquakes. In Nanjing alone, there were fifteen in just one month in 1525.

The most devastating earthquake occurred on 23 January 1556, affecting the provinces of Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Henan. In Shaanxi, entire regions such as

Weinan

Weinan ( zh, s=渭南 , p=Wèinán) is a prefecture-level city in east-Guanzhong, central Shaanxi, Shaanxi province, northwest China. The city lies on the lower section of the Wei River confluence into the Yellow River, about east of the provinc ...

,

Huazhou,

Chaoyi, and

Sanyuan were left in ruins. The

Yellow River

The Yellow River, also known as Huanghe, is the second-longest river in China and the List of rivers by length, sixth-longest river system on Earth, with an estimated length of and a Drainage basin, watershed of . Beginning in the Bayan H ...

and the

Wei River

The Wei River () is a major river in west-central China's Gansu and Shaanxi provinces. It is the largest tributary of the Yellow River and very important in the early development of Chinese civilization. In ancient times, such as in the Records ...

also overflowed, and some areas experienced tremors for several days. The disaster claimed the lives of 830,000 people, including several former ministers. As a result, the affected areas were granted tax forgiveness for several years.

Despite facing occasional challenges from nature, the first half of the 16th century saw significant economic growth in agriculture and crafts. However, the state struggled to collect taxes, particularly from newly cultivated land, trade, and handicraft production. The quotas and revenues set a century earlier were not met.

New crops from America

During the Jiajing era, Chinese peasants began to expand their agricultural crops to include species native to Central and South America. In the 1530s,

groundnut cultivation was documented in Jiangnan, having spread there from

Fujian

Fujian is a provinces of China, province in East China, southeastern China. Fujian is bordered by Zhejiang to the north, Jiangxi to the west, Guangdong to the south, and the Taiwan Strait to the east. Its capital is Fuzhou and its largest prefe ...

. Fujian peasants acquired this crop from Portuguese sailors.

Sweet potato

The sweet potato or sweetpotato (''Ipomoea batatas'') is a dicotyledonous plant in the morning glory family, Convolvulaceae. Its sizeable, starchy, sweet-tasting tuberous roots are used as a root vegetable, which is a staple food in parts of ...

es were documented in

Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

at the beginning of the 1560s, having arrived via Burma. Their presence on the southeast coast (Fujian and Guangdong) was only mentioned by authors of the time in the last decades of the 16th century, during the

Wanli era. Maize cultivation was documented as early as the 1550s in inland Henan, but it was most likely acquired from Europeans several decades earlier. It was also sent by Yunnan natives to Beijing as part of tribute before the mid-16th century. However, maize was not well-liked by the Han people and its cultivation remained the concern of minority peoples in southwest China for nearly three centuries. It was only in the 18th century that it began to be grown on a larger scale in Han-populated regions.

State finances at the beginning of the Jiajing Emperor's reign

Yang Tinghe, upon the accession of the Jiajing Emperor, implemented a program of severe austerity. This was in response to the significant increase in the number of state-paid dignitaries during the previous century. The number of officers rose from less than 13,000 at the beginning of the Hongwu Emperor's reign (1368–1398) to 28,000 by the end, and eventually reached 100,000 in 1520; many of them lived in and around the capital. Many of these officers were surplus and did not actively serve in the military. The same was true for civil servants, resulting in a total of around 4 million ''

dan'' of grain being imported to Beijing each year to support the needs of civil servants, soldiers, and officers. This grain was distributed at a rate of 1 ''dan'' (107.4 liters) per person per month, providing for approximately 300,000 individuals. In 1522, Yang took decisive action by cutting off payments to 148,700 supernumerary and honorary officers and officials, resulting in an annual reduction of 1.5 million ''dan'' of grain in state expenditure. This move proved to be beneficial in the mid-16th century, as the savings allowed the authorities to convert the 1.5 million ''dan'' of grain tax into a silver tax, greatly improving the state's finances.

State finances in the 1540s–1560s

In the mid-1520s, despite efforts to save money, the state's financial situation remained problematic. The costly construction projects during the early years of the Jiajing era had depleted the grain supplies from 8–9 years' worth of expenditure to only 3 years, as well as the silver reserves that had been accumulated in the 1520s. In 1540, the Minister of Revenue was dismissed for refusing to agree to an increase in the number of workers on public works, which already numbered 40,000. He argued that the cost of reconstructing palaces, ceremonial altars, and temples had already reached 6 million ''liang'' (224 tons) of silver since the beginning of the Jiajing Emperor's reign, and that he did not have the means to sustain such a pace of construction. While the emperor did cancel some projects, the most expensive buildings in the West Park were not among them.

The revenue of the Taicang treasury, which consisted of the Ministry of Revenue's income in silver, averaged 2 million ''liang'' (74.6 tons) per year after 1532. Out of this amount, 1.3 million ''liang'' was allocated for border defense. However, in the 1540s, the annual silver expenditure increased to 3.47 million ''liang'', resulting in a deficit of 1.4 million ''liang''. The Ministry of Revenue attempted to address this issue by implementing stricter monitoring of income and expenses, as well as requiring final accounts to be presented at the end of each year. Despite these efforts, the deficits persisted. In 1541, 1.2 million ''dan'' of grain surplus, which was a result of Yang Tinghe's austerity measures, were converted into silver payments. However, this decision was later revoked after five years, but was eventually reinstated. This led to an increase in the annual revenue of the Taicang treasury from 2 million to more than 3 million ''liang'' in the early 1550s. From 1540 onwards, the conversion of taxes from grain to silver became widespread, although the specific proportion and method of conversion varied among different counties.

In the 1550s, state expenditures, both regular and extraordinary, increased significantly. The cost of maintaining military garrisons on the northern border doubled, and the state faced additional financial burdens due to the earthquake of 1556 and the fire that destroyed three audience palaces and the southern gate of the Forbidden City in 1557. The reconstruction of these palaces took five years and cost hundreds of thousands of ''liang'' of silver. In 1561, the emperor's palace in the West Park, which had also been recently rebuilt, burned down again. During this time, the state's annual expenditure in silver ranged from 3 to 6 million ''liang'', while the proper revenue was only around 3 million ''liang''. To make up for the shortfall, the state resorted to extraordinary taxes, savings, and even transfers from the emperor's personal treasury, which often left it completely depleted. In 1552, the Minister of Revenue proposed an additional tax of two million ''liang'' to be imposed on the wealthy prefectures of

Jiangnan

Jiangnan is a geographic area in China referring to lands immediately to the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including the southern part of its delta. The region encompasses the city of Shanghai, the southern part of Jiangsu ...

. The emperor agreed and this procedure was repeated. However, during the 1550s, Jiangnan was frequently attacked by pirates and also suffered from natural disasters, making it difficult to collect even the usual taxes. The local authorities were exhausted and lacked the resources to deal with floods and crop failures, and the government did not respond until the situation became dire and refugees, along with epidemics, appeared on the streets of Beijing. To fund military operations in southeastern China, taxes were levied in the affected regions, often in the form of labor surcharges. These taxes remained in place until some of them (totaling 400–500 thousand ''liang'') were abolished in 1562.

Savings and frugality also had negative consequences. In 1560, the market price of rice doubled to 0.8 ''liang'' of silver per tan, leading to a revolt by the Nanjing garrison. To appease them, 40 thousand ''liang'' (1492 kg) of silver was distributed, and the soldiers were not punished.

Another issue was the salaries of members of the imperial family, which exceeded 8.5 million ''dan'' of grain in the early 1560s and were still insufficient for the large number of family members. This problem was brought to the attention of the emperor, who discussed it but took no action. In 1564, 140 members of the imperial family gathered in front of the governor's residence in Shaanxi to demand payment of their arrears, which amounted to over 600,000 ''dan'' of grain, but the local authorities were only able to collect 78,000 ''liang'' of silver. As a result, the emperor excluded those involved from the imperial family, but the issue persisted.

Land tax reforms

The government's need for silver revenue prompted the implementation of the single whip reform, beginning in the south-east coast where there was a surplus of silver due to the flourishing trade industry. From the 1530s to the 1570s, the primary source of silver for China was western Japan, where new deposits were found. In the 1550s and 1560s, Chinese merchants faced restricted access to Japan due to conflicts on the Chinese coast. As a result, the Portuguese took on the role of intermediary between Japan and China.

The reforms, known as the "

single whip reform", encompassed a variety of measures that were implemented in different locations and combinations. These measures included the replacement of taxpayers with compulsory labor for land assignments, the introduction of annual payments instead of the previous ten-year levy cycle of the lijia system, the substitution of compulsory labor tax payments, the consolidation of various fees and mandatory services into a single payment, and the simplification of land categorization. In 1522, a new method of calculating taxes was implemented (initially in one county). This method took into account the fertility of newly fertilized land and the conversion of field area to fiscal ''

mu'', making it easier for taxpayers to calculate their taxes. This method became popular in both the north and south, but the government had mixed feelings about it. On one hand, it simplified the tax calculation process, but on the other hand, it relied on lower-ranking officials who were known for their corrupt practices. As a result, the government would sometimes support and other times ban this method. The adjustments and equalization of taxes also had a positive impact on land prices and market activity. In some cases, the implementation of new local cadastres led to households acquiring land registers, replacing the outdated Yellow Registers.

Culture

Philosophy

During the early years of the Jiajing Emperor's reign, the statesman and philosopher

Wang Yangming

Wang Shouren (, 26 October 1472 – 9 January 1529), courtesy name Bo'an (), art name Yangmingzi (), usually referred to as Wang Yangming (), was a Chinese statesman, general, and Neo-Confucian philosopher during the Ming dynasty. After Zhu ...

(d. 1529) was in the last years of his life. Although he did not participate in the rites dispute, his disciples were sympathetic towards the emperor's "following of the inner moral voice". Despite his previous success in quelling the

rebellion of the Prince of Ning, Wang had been dismissed from his position in the civil service under the Zhengde Emperor. In 1525, the Minister of Rites, Xi Shu (), proposed his reinstatement due to his exceptional reputation as a statesman. This proposal faced opposition from grand secretaries Gui E and Yang Yiqing, whose influence would diminish with Wang's return to Beijing. As a result, they suggested sending him to the southeast to suppress the rebellion in Guangxi.

Wang Yangming's new concept of Neo-Confucian philosophy, centered on the concept of ''xin'' (heart/mind), was met with criticism from representatives of the official

Zhusist orthodoxy. As a result, his teachings were banned and he was only rehabilitated in 1567, after the death of the Jiajing Emperor. However, despite this setback, his ideas continued to spread throughout the country. As his teachings gained popularity, his followers formed various regional schools. The Jiangzhou school, led by figures such as

Luo Hongxian, Zuo Shouyi (), Ouyang De (), and Nie Bao (), provided the most accurate interpretation of Wang's ideas. The Taizhou school, on the other hand, led by

Wang Gen, He Xinyin (), and others, took a more radical approach.

Some Neo-Confucians disagreed with the views of either Wang Yangming or Zhu Xi on the origin of the universe. Instead, they focused on elaborating the concept of ''

qi''. For example, Wang Tingxiang () drew inspiration from the ideas of

Zhang Zai

Zhang Zai () (1020–1077) was a Chinese philosopher and politician. He is best known for laying out four ontological goals for intellectuals: to build up the manifestations of Heaven and Earth's spirit, to build up good life for the populace, t ...

of Song and Xue Xuan () of Ming. He argued that the universe did not arise from the principle of ''

li'', but from the primordial energy of ''qi'' (''yuan qi''). Similarly, Luo Qinshun () believed that energy was the primordial force, while principle served as the source of order and regularity. Both of these thinkers aimed to shift philosophy from moralizing to

empiricism

In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along ...

, a direction that would become prevalent in Chinese Confucianism a century later during the early Qing period.

Painting and calligraphy

During the Jiajing era, the epicenter of artistic creativity was in the wealthy

Jiangnan

Jiangnan is a geographic area in China referring to lands immediately to the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including the southern part of its delta. The region encompasses the city of Shanghai, the southern part of Jiangsu ...

region, particularly in

Suzhou

Suzhou is a major prefecture-level city in southern Jiangsu province, China. As part of the Yangtze Delta megalopolis, it is a major economic center and focal point of trade and commerce.

Founded in 514 BC, Suzhou rapidly grew in size by the ...

. This area attracted intellectuals who prioritized artistic self-expression over pursuing an official career. These intellectuals were known as the

Wu School, named after the region's old name. The most prominent and representative painters of the Wu School were

Wen Zhengming

Wen Zhengming (28 November 1470 – 28 March 1559Wen Zhengming's epitaph by Huang Zuo indicate that he died on the 20th day of the 2nd month of the ''ji'wei'' year during the reign of the Jiajing Emperor. (嘉靖己未二月二十日,与严侍 ...

and

Chen Chun. Wen Zhengming was a master of poetry, calligraphy, and painting. He was known for his monochrome or lightly colored landscapes in the style of

Shen Zhou

Shen Zhou (, 1427–1509), courtesy names Qinan () and Shitian (), was a Chinese painting, Chinese painter in the Ming dynasty. He lived during the post-transition period of the Yuan conquest of the Ming. His family worked closely with the gove ...

, as well as his "

blue-green landscapes" in the Tang style. He is credited with reviving the tradition of southern amateur painting. Chen Chun, a disciple of Wen Zhengming, brought originality to the genre of

flowers and birds. He was also renowned for his conceptual writing as a calligrapher. Wen Zhengming had many disciples and followers, including his sons

Wen Peng and

Wen Jia, who were both painters. Wen Peng, in addition to his skills in conceptual writing, gained recognition for his seal carving. Other notable painters from the Wu School include Wen Zhengming's relative

Wen Boren, as well as

Qian Gu and

Lu Zhi.

Many artists, such as

Qiu Ying

Qiu Ying (; 1494–1552) was a Chinese painter of the Ming dynasty who specialised in the '' gongbi'' brush technique.

Early life

Qiu Ying's courtesy name was Shifu (), and his art name was Shizhou (). He was born to a peasant family in Tai ...

and

Xu Wei

Xu Wei (, 1521–1593), also known as Qingteng Shanren (), was a Chinese painter, playwright, poet, and tea master during the Ming dynasty. Cihai: Page 802.Barnhart: Page 232.

Life

Xu's courtesy names were Wenqing (文清) and then later Wenc ...

, were influenced by the Wu school but did not belong to it. They worked in Suzhou and its surrounding areas. Qiu Ying was part of the conservative wing of the

Southern tradition, while Xu Wei broke away from this conservative expression. His paintings are characterized by a deliberate carelessness and simplification of form, resulting in exceptional credibility and expressiveness in his compositions. Qiu's works were more popular among the general public than the work of scholars and officials, known as

literary painting. As a result, merchants often signed paintings in his name, even if they were far from his style.

Poetry, drama

The direction of literary development in the previous Zhengde era and the beginning of the Jiajing era was determined by the Earlier Seven Masters, led by

Li Mengyang and He Jingming (), including Wang Tingxiang (). Their main objective was to break away from the traditional cabinet-style poetry of the 15th century, which they believed lacked expression and emotion due to its adherence to conventions. Instead, they looked to

Han and

Qin prose, as well as

Tang and older poetry, particularly from the peak Tang period, as their models.

This trend continued into the 16th century with the emergence of

Xie Zhen, the first of the

Latter Seven Masters. Li Panlong () led the Latter Seven Masters, with Wang Shizhen () being considered the greatest poet among them.

Both the Earlier and Latter Seven Masters had a significant influence on the poets of Ming China, and their poetic style remained popular for many decades. However, some literati believed that their principles were too restrictive, leading to mere imitation without any originality. One such poet was Xue Hui (), as well as Yang Tinghe's son,

Yang Shen,

whose work gained many admirers. Yang Shen's most prized collection of poems was the one he exchanged with his wife,

Huang E, who was also a talented poet, while he was living in exile after 1524. Despite the prevailing trend of admiration for "Tang poetry and Han prose," the Eight Talents of the Jiajing era stood out by modeling their writing after the authors of the Tang and Song dynasties. The most notable among the Eight Talents were

Li Kaixian, Wang Shenzhong (), and Tang Shunzhi ().

In the genre of northern ''

zayu'' plays,

Kang Hai and

Wang Jiusi were important dramatists. Following them, Li Kaixian focused on drama, publishing Yuan ''zayu'' and composing plays in the southern style of ''

chuanqi''. Xu Wei, the most renowned Ming author of ''zayu'', followed in his footsteps. However, Li Kaixian's generation was the last to excel in northern drama, as the plays of the south began to dominate.

Military and foreign policy

Turpan

In 1513, Mansur, the Sultan of

Turpan

Turpan () or Turfan ( zh, s=吐鲁番) is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of and a population of 693,988 (2020). The historical center of the ...

, invaded

Hami

Hami ( zh, c=哈密) or Kumul () is a prefecture-level city in eastern Xinjiang, China. It is well known for sweet Hami melons. In early 2016, the former Hami county-level city merged with Hami Prefecture to form the Hami prefecture-level city ...

and caused destruction in the Chinese territories to the east. Sayyid Husayn, who was Mansur's envoy in Beijing, negotiated a deal where Mansur would keep Hami and the (

tribute

A tribute (; from Latin ''tributum'', "contribution") is wealth, often in kind, that a party gives to another as a sign of submission, allegiance or respect. Various ancient states exacted tribute from the rulers of lands which the state con ...

) trade would be reinstated. In 1521, Sayyid was executed for treason and the Turpan delegation was expelled from Beijing. This led to a hostile attitude towards Turpan, enforced by Yang Tinghe. As a result, fighting resumed and in 1524, the Turpans also attacked

Ganzhou

Ganzhou (), alternately romanized as Kanchow, is a prefecture-level city in the south of Jiangxi province, China, bordering Fujian to the east, Guangdong to the south, and Hunan to the west. Its administrative seat is at Zhanggong District.

His ...

. Ming troops, mostly composed of Mongols, successfully defended against the attackers, but the conflict continued until 1528 when Mansur returned to a strategy of small raids.

In 1528, the western border once again became a point of contention. Ilan, one of Mansur's generals, sought asylum in Ming territory. Mansur demanded his extradition in exchange for Hami. Additionally, he requested the resumption of trade, which had been halted in 1524.

Wang Qiong, minister of war in charge of the western borders, along with Zhang Cong and Gui E, supported the resumption of trade. However, there were voices of opposition, arguing that showing leniency without a formal apology would not be beneficial in the long run. Despite this, the emperor ultimately decided to grant Mansur's request. As a result, the western border was pacified, and the Ming government was able to focus on dealing with the increasingly aggressive Mongols, who had become more hostile after 1528.

Đại Việt

In 1537, a debate erupted at the Ming court regarding

Đại Việt

Đại Việt (, ; literally Great Việt), was a Vietnamese monarchy in eastern Mainland Southeast Asia from the 10th century AD to the early 19th century, centered around the region of present-day Hanoi. Its early name, Đại Cồ Việt,(ch ...

(present-day northern

Vietnam

Vietnam, officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam (SRV), is a country at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of about and a population of over 100 million, making it the world's List of countries and depende ...

). This was sparked by the birth of the emperor's son in November 1536, when messages were sent to neighboring countries to share the joyous news. Grand Secretary Xia Yan refused to include Đại Việt in these messages, citing the country's failure to send tribute for the past twenty years and the illegitimacy of its current ruler,

Mạc Thái Tông of the

Mạc dynasty

The Mạc dynasty (; Hán-Nôm: 茹 莫/ 朝 莫) (1527–1677), officially Đại Việt (Chữ Hán: 大越), was a Vietnamese dynasty which ruled over a unified Vietnam between 1527 and 1540, and northern Vietnam from 1540 until 1593. The M ...

. In response, the Minister of War and the militarist faction in the government, led by Guo Xun (), Marquis of Wuding, proposed a punitive expedition. This proposal was met with criticism for being extravagant and costly. Yan Song also spoke out against the proposal.

In March 1537, envoys from the legitimate Viet ruler,

Lê Trang Tông of the

Lê dynasty

The Lê dynasty, also known in historiography as the Later Lê dynasty (, chữ Hán: 朝後黎, chữ Nôm: 茹後黎), officially Đại Việt (; Chữ Hán: 大越), was the longest-ruling List of Vietnamese dynasties, Vietnamese dynasty, h ...

, arrived in Beijing seeking assistance against the Mạc dynasty. The Jiajing Emperor responded by sending officials to investigate the situation, which he perceived as an affront to his majesty. He initially considered military action, but local authorities in Guangdong objected, arguing that the Viets had not crossed the border and the outcome of their civil war was uncertain. Despite these protests, a decision was made in May to go to war, but after further objections from regional officials, the emperor began to waver and ultimately cancelled military preparations in June. In September 1537, new proposals from the other local officials convinced him to resume preparations for war.

In the spring of 1538, the Jiajing Emperor appointed a campaign commander, but after the border authorities calculated the expected costs and problems of the war and the Ministry of War responded to the emperor's inquiry by submitting the matter to inter-ministerial consultations, the emperor ultimately decided to cancel the war. However, the gathering of 110,000 troops in Guangxi during preparations for war alarmed Mạc Thái Tông. In an attempt to avert an invasion in 1540, Mạc Thái Tông ceded disputed border territories to the Ming Empire and accepted the subordinate status of his state.

This event left the Jiajing Emperor with the impression that his officials were more concerned with their personal interests than the well-being of the state and that they were unable to come up with a sound policy. By 1540, the Jiajing Emperor had become increasingly isolated from his government and saw it as an obstacle to the proper administration of the country.

The Mongols

As a result of internal conflicts among the Mongols, the Jiajing Emperor's government did not have much to worry about in the first decade of his reign, and their raids were rare. However, the Ming army itself posed a significant problem. As early as the 16th century, difficulties in the border garrisons were on the rise. In 1510, soldiers killed the governor of

Ningxia

Ningxia, officially the Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, is an autonomous region in Northwestern China. Formerly a province, Ningxia was incorporated into Gansu in 1954 but was later separated from Gansu in 1958 and reconstituted as an autonomous ...

, and in 1521, the governor of

Gansu

Gansu is a provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. Its capital and largest city is Lanzhou, in the southeastern part of the province. The seventh-largest administrative district by area at , Gansu lies between the Tibetan Plateau, Ti ...

met the same fate. In August 1524, officers and soldiers in

Datong

Datong is a prefecture-level city in northern Shanxi Province, China. It is located in the Datong Basin at an elevation of and borders Inner Mongolia to the north and west and Hebei to the east. As of the 2020 census, it had a population o ...

killed the governor and burned government buildings. Although the unrest was temporarily quelled by the execution of the rebellion's leaders in April 1525, the Datong rebellion, which was linked to the death of the garrison commander, resurfaced in 1533. Smaller rebellions also occurred in 1535 and 1539, and in 1545, members of the imperial family also rose up. The government's response to these rebellions was typically to make concessions, which ultimately failed to address the underlying issues.

After the political situation in Mongolia stabilized, the Mongols began to stage raids on Ming territory every spring and early autumn. These raids were often successful due to the incapacitation of Ming garrisons, making them an effective substitute for trade for the Mongols. In contrast to Đại Việt, the emperor showed a clear preference for using force in his relations with the Mongols and rejected proposals to restore trade. However,

Altan Khan, who solidified his rule over the Mongols in the steppes west and south of the

Gobi Desert

The Gobi Desert (, , ; ) is a large, cold desert and grassland region in North China and southern Mongolia. It is the sixth-largest desert in the world. The name of the desert comes from the Mongolian word ''gobi'', used to refer to all of th ...

in the 1540s, desired Chinese goods. His attacks on Ming territory were motivated by his need for funds to wage war against the

Oirats

Oirats (; ) or Oirds ( ; ), formerly known as Eluts and Eleuths ( or ; zh, 厄魯特, ''Èlǔtè'') are the westernmost group of Mongols, whose ancestral home is in the Altai Mountains, Altai region of Siberia, Xinjiang and western Mongolia.

...

, as well as supplies to alleviate the effects of droughts and famines in the 1540s and 1550s.

The Ming troops were successful in defending against smaller raids, but they were unable to stop large-scale Mongol attacks involving tens of thousands of horsemen. By the time enough forces were gathered, the Mongols had already retreated back to the

steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

. In response, the Ming government focused on strengthening their defenses and building fortifications, for which the emperor was willing to allocate significant funds. They also worked on improving discipline and intelligence activities. However, they failed to address the root causes of these raids.

During the 1540s and 1550s, Altan Khan repeatedly requested the restoration of trade, but the emperor refused, leading the Mongols to resort to force in order to obtain the resources they needed. This resulted in a series of raids and plundering, including the plundering of

Shanxi

Shanxi; Chinese postal romanization, formerly romanised as Shansi is a Provinces of China, province in North China. Its capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-level cities are Changzhi a ...

in 1541–1543 and the vicinity of Beijing in the late 1540s. By 1550, the Mongols had even reached the walls of

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

. In an attempt to calm the situation, the emperor allowed the opening of border markets in the spring of 1551, but after only six months, he closed the markets again and the Mongols resumed their raids. The Eastern Mongols also joined in on the attacks, plundering

Liaodong

The Liaodong or Liaotung Peninsula ( zh, s=辽东半岛, t=遼東半島, p=Liáodōng Bàndǎo) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located ...

in the early 1550s. This continued for the next two decades, with the entire northern frontier constantly under threat. The Chinese, for their part, focused on defending the passes that led to the North China Plain and Beijing.

Military reforms in the early 1550s

The failure of the Beijing garrison to defend against the Mongol invasion in 1550 prompted reforms, resulting in the abolition of 12 divisions and the western and eastern special detachments. These were replaced by the Three Great Camps, totaling 147,000 soldiers. These three corps were under the command of

Qiu Luan, who held the title of Superintendent Commander-in-chief (; ''zongdu jingying rongzheng'') and had gained recognition from the emperor for his role in the battles against the Mongols. After Qiu Luan's death in 1552, the commander's powers were limited and the position was eventually abolished in 1570. The three corps then operated independently with their own headquarters.

In 1552, the emperor, recognizing the unreliability of the Beijing garrison, established the Palace Army (; ''Neiwufu'') made up of eunuchs. The following year, the southern suburbs of Beijing, known as the "Outer City", were fortified.

Sea ban policy and problems with pirates

Foreign maritime trade of the Ming dynasty was heavily restricted by the "

sea ban" policy, which aimed to limit trade to tribute exchange and prohibited unlicensed private trading. However, the government was unable to effectively enforce these restrictions, and illegal overseas trade became a significant part of the coastal economy.

In the late 15th century, Southeast China, particularly the

Jiangnan

Jiangnan is a geographic area in China referring to lands immediately to the south of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River, including the southern part of its delta. The region encompasses the city of Shanghai, the southern part of Jiangsu ...

region along the lower

Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ) is the longest river in Eurasia and the third-longest in the world. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau and flows including Dam Qu River the longest source of the Yangtze, i ...

River, experienced a surge in population, the development of communication networks, commercialization, and the growth of critical thinking. As officials with a more favorable view towards trade began to join the government, debates emerged regarding the effectiveness and relevance of the existing anti-trade policy. During the reign of the Jiajing Emperor, the government became divided on the issue. Two factions, one advocating for the legalization of foreign trade to prevent costly wars and eliminate the root causes of conflict, and the other representing conservative landowners who believed in maintaining prohibitions and viewed war as inevitable for the sake of the country's security and stability, clashed over the authorization of foreign trade.

In the 1520s and 1530s, there was a rise in pirate attacks and related violence along the southeast coast from Zhejiang to

Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

. The Jiajing government attempted to address this issue by implementing repeated bans on private maritime trade, even going as far as prohibiting the construction of ships with two or more

masts. Despite the efforts of conservatives, maritime trade continued to grow significantly in the mid-16th century. In fact, during the 15th and 16th centuries, the Ming state gradually shifted to using silver as a form of taxation due to the lack of other options, but silver mining was limited and the state was unable to ensure its import through the tribute system. As a result, the highly profitable silver importation fell into the hands of smuggling groups.

The bans on private maritime trade were difficult to enforce, as the local military garrisons were ill-equipped to deal with the pirates. The soldiers lacked proper training and discipline, and the officers were often involved in illegal trade themselves. Furthermore, lax enforcement of the bans was supported by some high-ranking officials, including Grand Secretary Zhang Cong.

In the 1540s, groups of smugglers and pirates united and grew stronger, building bases on islands off the coast. From the mid-1520s, their center was the port of

Shuangyu

Shuangyu () was a port on () off the coast of Zhejiang, China. During the 16th century, the port served as an illegal entrepôt of international trade, attracting traders from Japan, Southeast Asia, and Portugal in a time when private overseas tr ...

in the

Zhoushan

Zhoushan is an urbanized archipelago with the administrative status of a prefecture-level city in the eastern Chinese province of Zhejiang. It consists of an archipelago of islands at the southern mouth of Hangzhou Bay off the mainland c ...

archipelago near

Ningbo

Ningbo is a sub-provincial city in northeastern Zhejiang province, People's Republic of China. It comprises six urban districts, two satellite county-level cities, and two rural counties, including several islands in Hangzhou Bay and the Eas ...

, where the Portuguese arrived in 1539 and the Japanese in 1545. In the late 1540s and 1550s, violence reached its peak as raids by pirates and smugglers not only affected the countryside, but also the suburbs of major cities such as

Hangzhou

Hangzhou, , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ; formerly romanized as Hangchow is a sub-provincial city in East China and the capital of Zhejiang province. With a population of 13 million, the municipality comprises ten districts, two counti ...

and

Jiaxing

Jiaxing (), alternately romanized as Kashing, is a prefecture-level city in northern Zhejiang province, China. Lying on the Grand Canal of China, Jiaxing borders Hangzhou to the southwest, Huzhou to the west, Shanghai to the northeast, and the p ...

. In the latter half of the 1550s, generals

Hu Zongxian,

Yu Dayou, and

Qi Jiguang

Qi Jiguang (, November 12, 1528 – January 17, 1588), courtesy name Yuanjing, art names Nantang and Mengzhu, posthumous name Wuyi, was a Chinese military general and writer of the Ming dynasty. He is best known for leading the defense on th ...

managed to break up the smuggling groups and restore order in Zhejiang. By 1563, they had successfully cleared Fujian and by the mid-1560s, Guangdong and Guangxi. As a result, piracy was no longer a serious problem.

The Jiajing Emperor refused to lift the bans; it was only after his death in 1567 that a request to abolish the sea ban policy and allow "trade with both the western and eastern seas" was successful. Trade was then concentrated in Fujian's Moon Port (

Yuegang

Yuegang () was a seaport situated at the estuary of the Jiulong River in present-day Haicheng, Fujian, Haicheng town in Zhangzhou, Fujian, China. Known as a smuggling hub since the early Ming dynasty, Yuegang rose to prominence in the 16th century ...

), while trade with Japan remained strictly prohibited.

Portugal

In 1513, the first Portuguese arrived in China. King