E. coli on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a

''E. coli'' has three native glycolytic pathways: EMPP, EDP, and OPPP. The EMPP employs ten enzymatic steps to yield two pyruvates, two ATP, and two NADH per

''E. coli'' has three native glycolytic pathways: EMPP, EDP, and OPPP. The EMPP employs ten enzymatic steps to yield two pyruvates, two ATP, and two NADH per

''E. coli'' encompasses an enormous population of bacteria that exhibit a very high degree of both genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genome sequencing of many isolates of ''E. coli'' and related bacteria shows that a taxonomic reclassification would be desirable. However, this has not been done, largely due to its medical importance, and ''E. coli'' remains one of the most diverse bacterial species: only 20% of the genes in a typical ''E. coli'' genome is shared among all strains.

In fact, from the more constructive point of view, the members of genus ''Shigella'' (''S. dysenteriae'', ''S. flexneri'', ''S. boydii'', and ''S. sonnei'') should be classified as ''E. coli'' strains, a phenomenon termed

''E. coli'' encompasses an enormous population of bacteria that exhibit a very high degree of both genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genome sequencing of many isolates of ''E. coli'' and related bacteria shows that a taxonomic reclassification would be desirable. However, this has not been done, largely due to its medical importance, and ''E. coli'' remains one of the most diverse bacterial species: only 20% of the genes in a typical ''E. coli'' genome is shared among all strains.

In fact, from the more constructive point of view, the members of genus ''Shigella'' (''S. dysenteriae'', ''S. flexneri'', ''S. boydii'', and ''S. sonnei'') should be classified as ''E. coli'' strains, a phenomenon termed

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface

In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as '' Myxococcus xanthus''. In this predator-prey relationship, a parallel evolution of both species is observed through genomic and phenotypic modifications, in the case of ''E. coli'' the modifications are modified in two aspects involved in their virulence such as mucoid production (excessive production of exoplasmic acid alginate ) and the suppression of the OmpT gene, producing in future generations a better adaptation of one of the species that is counteracted by the evolution of the other, following a co-evolutionary model demonstrated by the Red Queen hypothesis.

In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as '' Myxococcus xanthus''. In this predator-prey relationship, a parallel evolution of both species is observed through genomic and phenotypic modifications, in the case of ''E. coli'' the modifications are modified in two aspects involved in their virulence such as mucoid production (excessive production of exoplasmic acid alginate ) and the suppression of the OmpT gene, producing in future generations a better adaptation of one of the species that is counteracted by the evolution of the other, following a co-evolutionary model demonstrated by the Red Queen hypothesis.

The first complete

The first complete

''E. coli'' is frequently used as a model organism in

''E. coli'' is frequently used as a model organism in

''E. coli'' on Protein Data Bank

{{Authority control Gut flora bacteria Tropical diseases Model organisms Bacteria described in 1919

gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelope consists ...

, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped

Bacterial cellular morphologies are the shapes that are characteristic of various types of bacteria and often key to their identification. Their direct examination under a light microscope enables the classification of these bacteria (and archae ...

, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia

''Escherichia'' ( ) is a genus of Gram-negative, non-Endospore, spore-forming, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae. In those species which are inhabitants of the gastroin ...

'' that is commonly found in the lower intestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

of warm-blooded

Warm-blooded is a term referring to animal species whose bodies maintain a temperature higher than that of their environment. In particular, homeothermic species (including birds and mammals) maintain a stable body temperature by regulating ...

organisms. Most ''E. coli'' strains are part of the normal microbiota of the gut, where they constitute about 0.1%, along with other facultative anaerobes. These bacteria are mostly harmless or even beneficial to humans. For example, some strains of ''E. coli'' benefit their hosts by producing vitamin K2 or by preventing the colonization of the intestine by harmful pathogenic bacteria

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and many are Probiotic, beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The nu ...

. These mutually beneficial relationships between ''E. coli'' and humans are a type of mutualistic biological relationship—where both the humans and the ''E. coli'' are benefitting each other. ''E. coli'' is expelled into the environment within fecal matter. The bacterium grows massively in fresh fecal matter under aerobic conditions for three days, but its numbers decline slowly afterwards.

Some serotype

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or Cell (biology), cells are classified together based on their shared reactivity ...

s, such as EPEC and ETEC, are pathogenic, causing serious food poisoning in their hosts. Fecal–oral transmission is the major route through which pathogenic strains of the bacterium cause disease. This transmission method is occasionally responsible for food contamination

A food contaminant is a harmful chemical or microorganism present in food, which can cause illness to the consumer.

The impact of chemical contaminants on consumer health and well-being is often apparent only after many years of processing and ...

incidents that prompt product recalls. Cells are able to survive outside the body for a limited amount of time, which makes them potential indicator organism

Indicator organisms are used as a proxy to monitor conditions in a particular environment, ecosystem, area, habitat, or consumer product. Certain bacteria, fungi and helminth eggs are being used for various purposes.

Types Indicator bacteria ...

s to test environmental samples for fecal contamination. A growing body of research, though, has examined environmentally persistent ''E. coli'' which can survive for many days and grow outside a host.

The bacterium can be grown and cultured easily and inexpensively in a laboratory setting, and has been intensively investigated for over 60 years. ''E. coli'' is a chemoheterotroph whose chemically defined medium must include a source of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

and energy

Energy () is the physical quantity, quantitative physical property, property that is transferred to a physical body, body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of Work (thermodynamics), work and in the form of heat and l ...

. ''E. coli'' is the most widely studied prokaryotic model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

, and an important species in the fields of biotechnology

Biotechnology is a multidisciplinary field that involves the integration of natural sciences and Engineering Science, engineering sciences in order to achieve the application of organisms and parts thereof for products and services. Specialists ...

and microbiology

Microbiology () is the branches of science, scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular organism, unicellular (single-celled), multicellular organism, multicellular (consisting of complex cells), or non-cellular life, acellula ...

, where it has served as the host organism for the majority of work with recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

. Under favourable conditions, it takes as little as 20 minutes to reproduce.

Biology and biochemistry

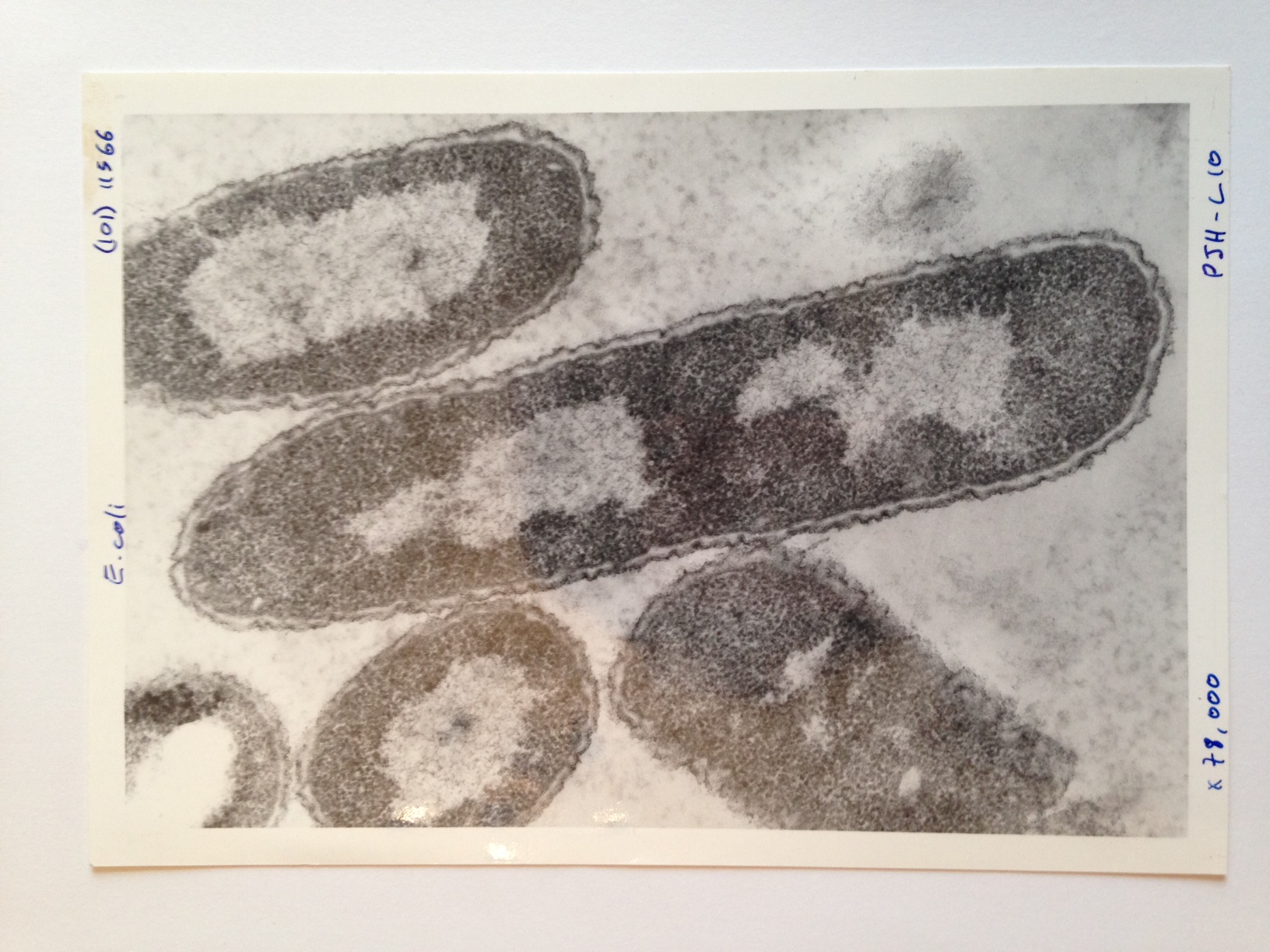

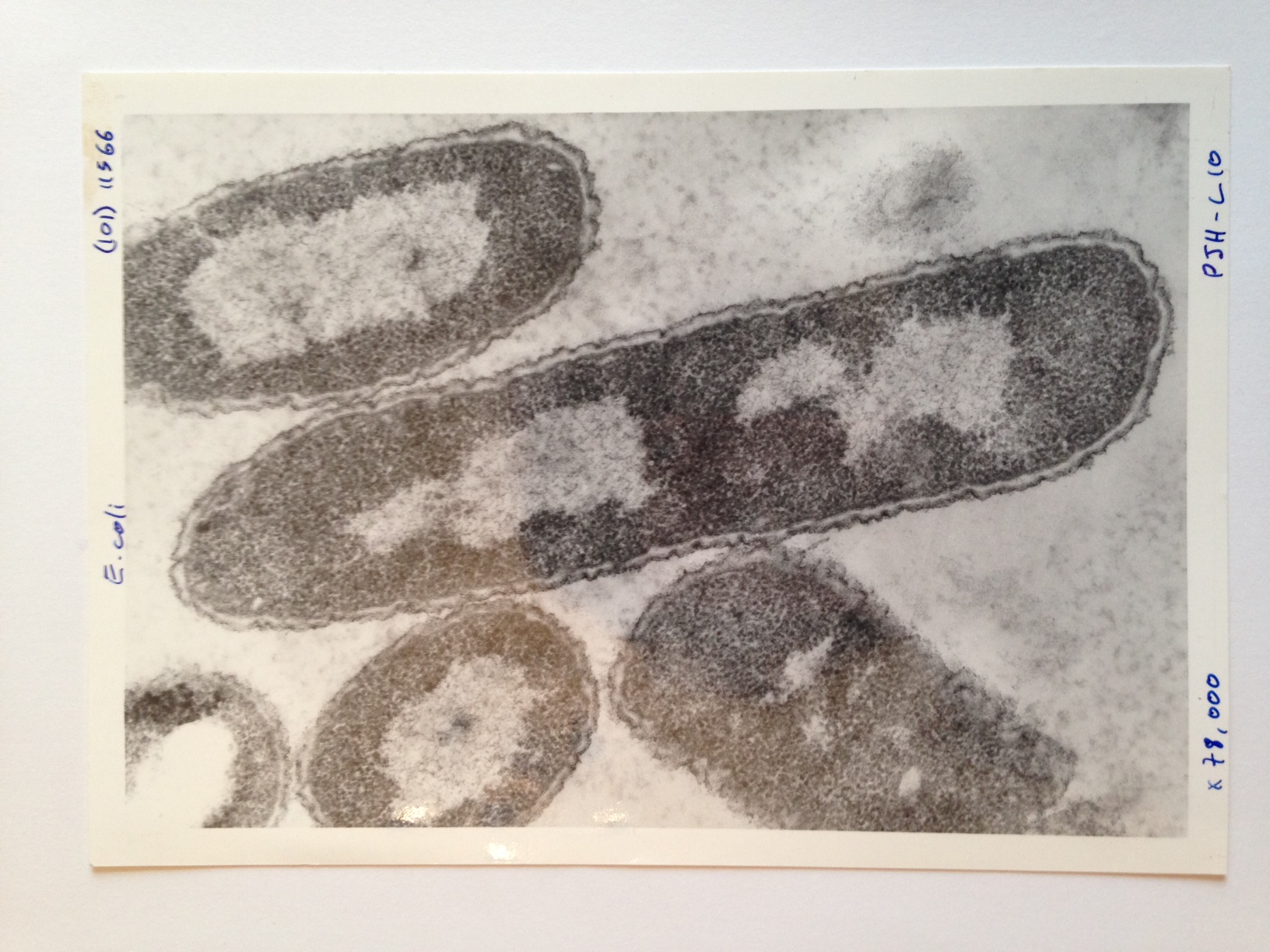

Type and morphology

''E. coli'' is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobe, nonsporulating coliform bacterium. Cells are typically rod-shaped, and are about 2.0 μm long and 0.25–1.0 μm in diameter, with a cell volume of 0.6–0.7 μm3. ''E. coli'' stains gram-negative because itscell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

is composed of a thin peptidoglycan layer and an outer membrane. During the staining process, ''E. coli'' picks up the color of the counterstain safranin and stains pink. The outer membrane surrounding the cell wall provides a barrier to certain antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

, such that ''E. coli'' is not damaged by penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

.

The flagella

A flagellum (; : flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores ( zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility. Many pr ...

which allow the bacteria to swim have a peritrichous arrangement. It also attaches and effaces to the microvilli of the intestines via an adhesion molecule known as intimin.

Metabolism

''E. coli'' can live on a wide variety of substrates and uses mixed acid fermentation in anaerobic conditions, producing lactate, succinate,ethanol

Ethanol (also called ethyl alcohol, grain alcohol, drinking alcohol, or simply alcohol) is an organic compound with the chemical formula . It is an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol, with its formula also written as , or EtOH, where Et is the ps ...

, acetate

An acetate is a salt formed by the combination of acetic acid with a base (e.g. alkaline, earthy, metallic, nonmetallic, or radical base). "Acetate" also describes the conjugate base or ion (specifically, the negatively charged ion called ...

, and carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide is a chemical compound with the chemical formula . It is made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalent bond, covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in a gas state at room temperature and at norma ...

. Since many pathways in mixed-acid fermentation produce hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

gas, these pathways require the levels of hydrogen to be low, as is the case when ''E. coli'' lives together with hydrogen-consuming organisms, such as methanogen

Methanogens are anaerobic archaea that produce methane as a byproduct of their energy metabolism, i.e., catabolism. Methane production, or methanogenesis, is the only biochemical pathway for Adenosine triphosphate, ATP generation in methanogens. A ...

s or sulphate-reducing bacteria.

In addition, ''E. coli''s metabolism can be rewired to solely use CO2 as the source of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

for biomass production. In other words, this obligate heterotroph's metabolism can be altered to display autotrophic capabilities by heterologously expressing carbon fixation

Biological carbon fixation, or сarbon assimilation, is the Biological process, process by which living organisms convert Total inorganic carbon, inorganic carbon (particularly carbon dioxide, ) to Organic compound, organic compounds. These o ...

genes as well as formate dehydrogenase and conducting laboratory evolution experiments. This may be done by using formate to reduce electron carriers and supply the ATP required in anabolic pathways inside of these synthetic autotrophs. ''E. coli'' has three native glycolytic pathways: EMPP, EDP, and OPPP. The EMPP employs ten enzymatic steps to yield two pyruvates, two ATP, and two NADH per

''E. coli'' has three native glycolytic pathways: EMPP, EDP, and OPPP. The EMPP employs ten enzymatic steps to yield two pyruvates, two ATP, and two NADH per glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

molecule while OPPP serves as an oxidation route for NADPH synthesis. Although the EDP is the more thermodynamically favourable of the three pathways, ''E. coli'' do not use the EDP for glucose metabolism, relying mainly on the EMPP and the OPPP. The EDP mainly remains inactive except for during growth with gluconate.

Catabolite repression

When growing in the presence of a mixture of sugars, bacteria will often consume the sugars sequentially through a process known as catabolite repression. By repressing the expression of the genes involved in metabolizing the less preferred sugars, cells will usually first consume the sugar yielding the highest growth rate, followed by the sugar yielding the next highest growth rate, and so on. In doing so the cells ensure that their limited metabolic resources are being used to maximize the rate of growth. The well-used example of this with ''E. coli'' involves the growth of the bacterium onglucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

and lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

, where ''E. coli'' will consume glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

before lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

. Catabolite repression has also been observed in ''E. coli'' in the presence of other non-glucose sugars, such as arabinose and xylose, sorbitol

Sorbitol (), less commonly known as glucitol (), is a sugar alcohol with a sweet taste which the human body metabolizes slowly. It can be obtained by reduction of glucose, which changes the converted aldehyde group (−CHO) to a primary alco ...

, rhamnose, and ribose

Ribose is a simple sugar and carbohydrate with molecular formula C5H10O5 and the linear-form composition H−(C=O)−(CHOH)4−H. The naturally occurring form, , is a component of the ribonucleotides from which RNA is built, and so this comp ...

. In ''E. coli'', glucose catabolite repression is regulated by the phosphotransferase system, a multi-protein phosphorylation

In biochemistry, phosphorylation is described as the "transfer of a phosphate group" from a donor to an acceptor. A common phosphorylating agent (phosphate donor) is ATP and a common family of acceptor are alcohols:

:

This equation can be writ ...

cascade that couples glucose uptake and metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

.

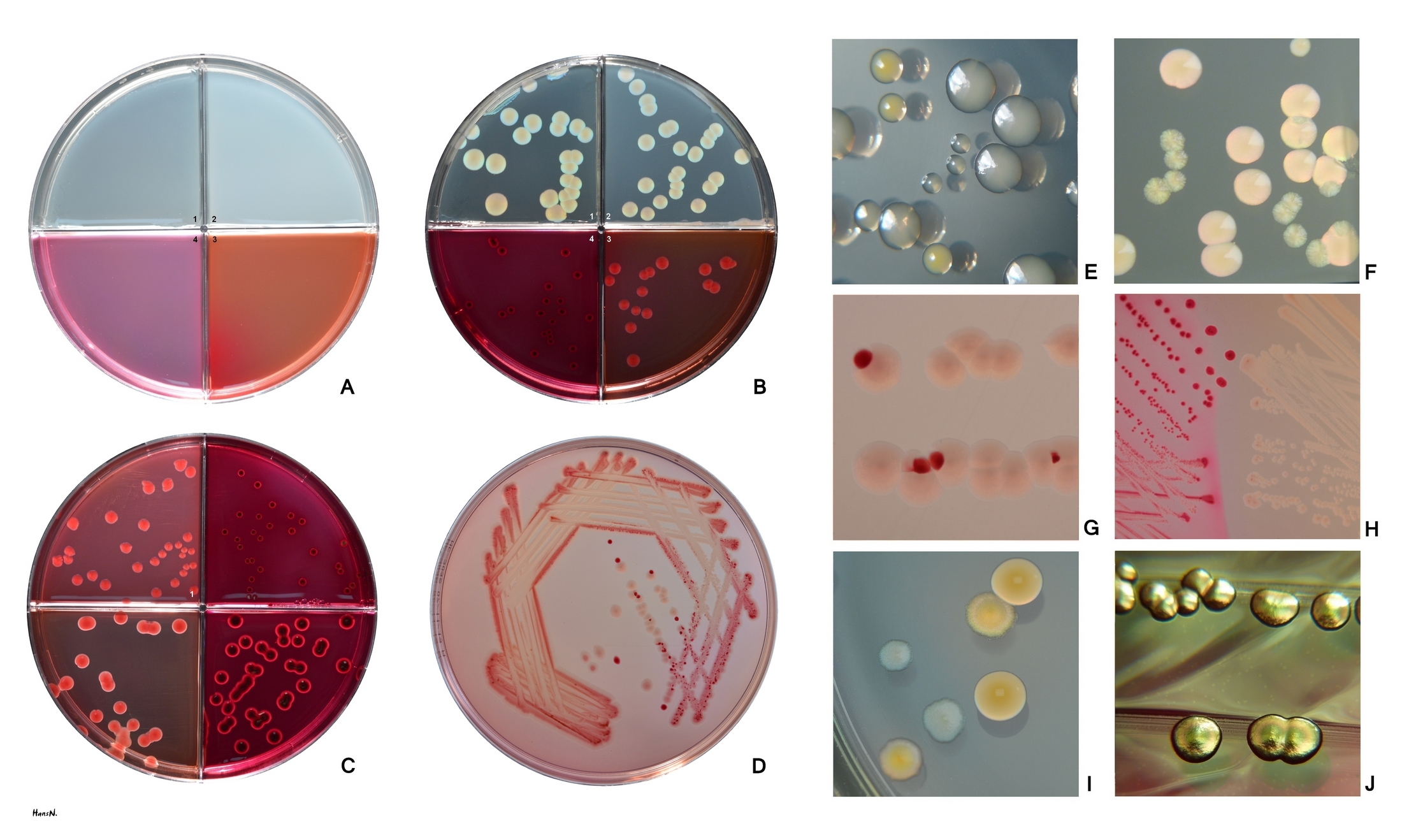

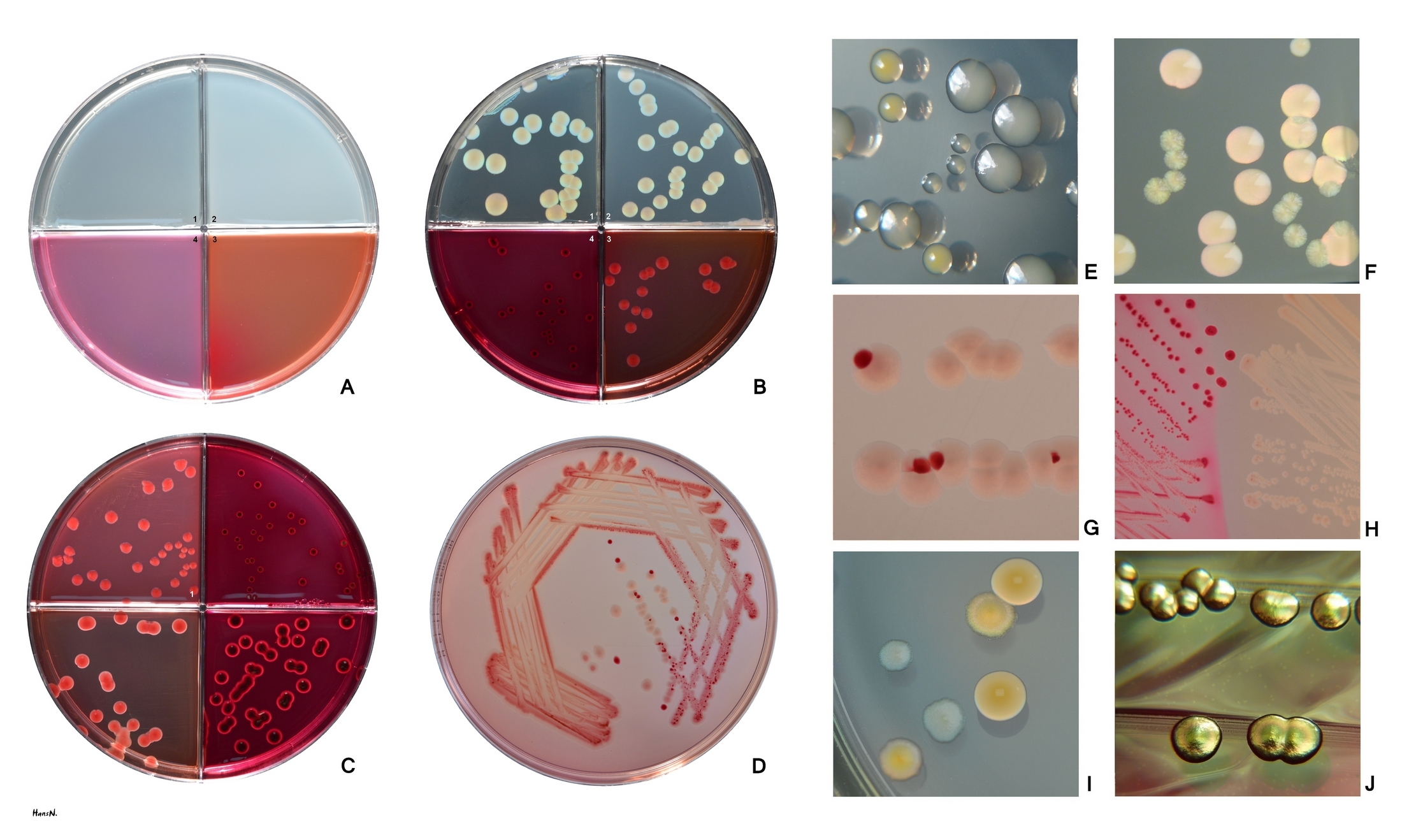

Culture growth

Optimum growth of ''E. coli'' occurs at , but some laboratory strains can multiply at temperatures up to . ''E. coli'' grows in a variety of defined laboratory media, such aslysogeny broth

Lysogeny broth (LB) is a Nutrient, nutritionally rich Growth medium, medium primarily used for the Bacterial growth, growth of bacteria. Its creator, Giuseppe Bertani, intended LB to stand for lysogeny broth, but LB has also come to colloquially ...

, or any medium that contains glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

, ammonium phosphate monobasic, sodium chloride

Sodium chloride , commonly known as Salt#Edible salt, edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs a ...

, magnesium sulfate

Magnesium sulfate or magnesium sulphate is a chemical compound, a salt with the formula , consisting of magnesium cations (20.19% by mass) and sulfate anions . It is a white crystalline solid, soluble in water but not in ethanol.

Magnesi ...

, potassium phosphate dibasic, and water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

. Growth can be driven by aerobic or anaerobic respiration, using a large variety of redox pairs, including the oxidation of pyruvic acid

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the keto acids, alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate acid, conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an metabolic intermediate, intermediate in several m ...

, formic acid

Formic acid (), systematically named methanoic acid, is the simplest carboxylic acid. It has the chemical formula HCOOH and structure . This acid is an important intermediate in chemical synthesis and occurs naturally, most notably in some an ...

, hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

, and amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s, and the reduction of substrates such as oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

, fumarate, dimethyl sulfoxide

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) is an organosulfur compound with the formula . This colorless liquid is the sulfoxide most widely used commercially. It is an important polar aprotic solvent that dissolves both polar and nonpolar compounds and is ...

, and trimethylamine N-oxide. ''E. coli'' is classified as a facultative anaerobe. It uses oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

when it is present and available. It can, however, continue to grow in the absence of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

using fermentation

Fermentation is a type of anaerobic metabolism which harnesses the redox potential of the reactants to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and organic end products. Organic molecules, such as glucose or other sugars, are catabolized and reduce ...

or anaerobic respiration. Respiration type is managed in part by the arc system. The ability to continue growing in the absence of oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

is an advantage to bacteria because their survival is increased in environments where water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

predominates.

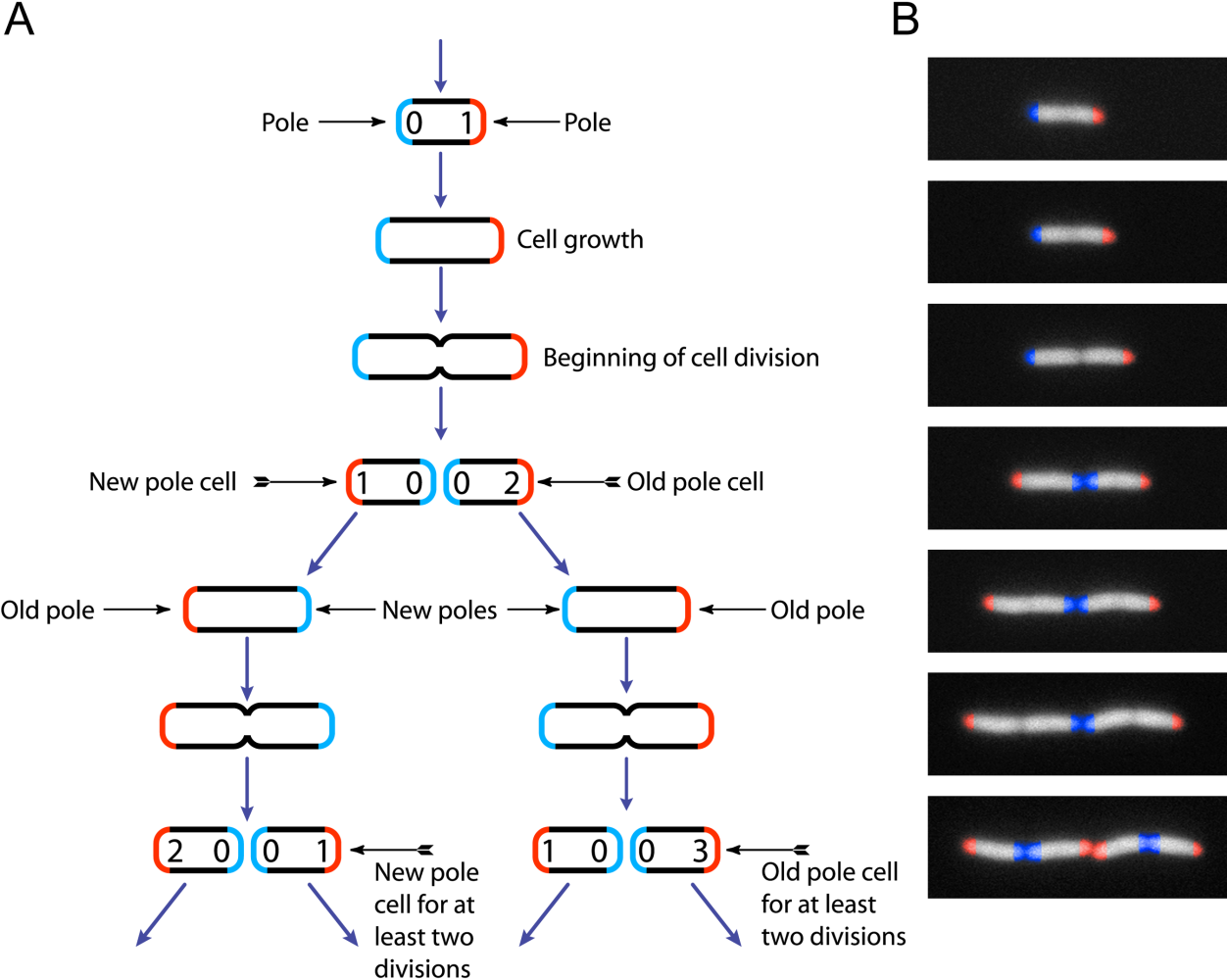

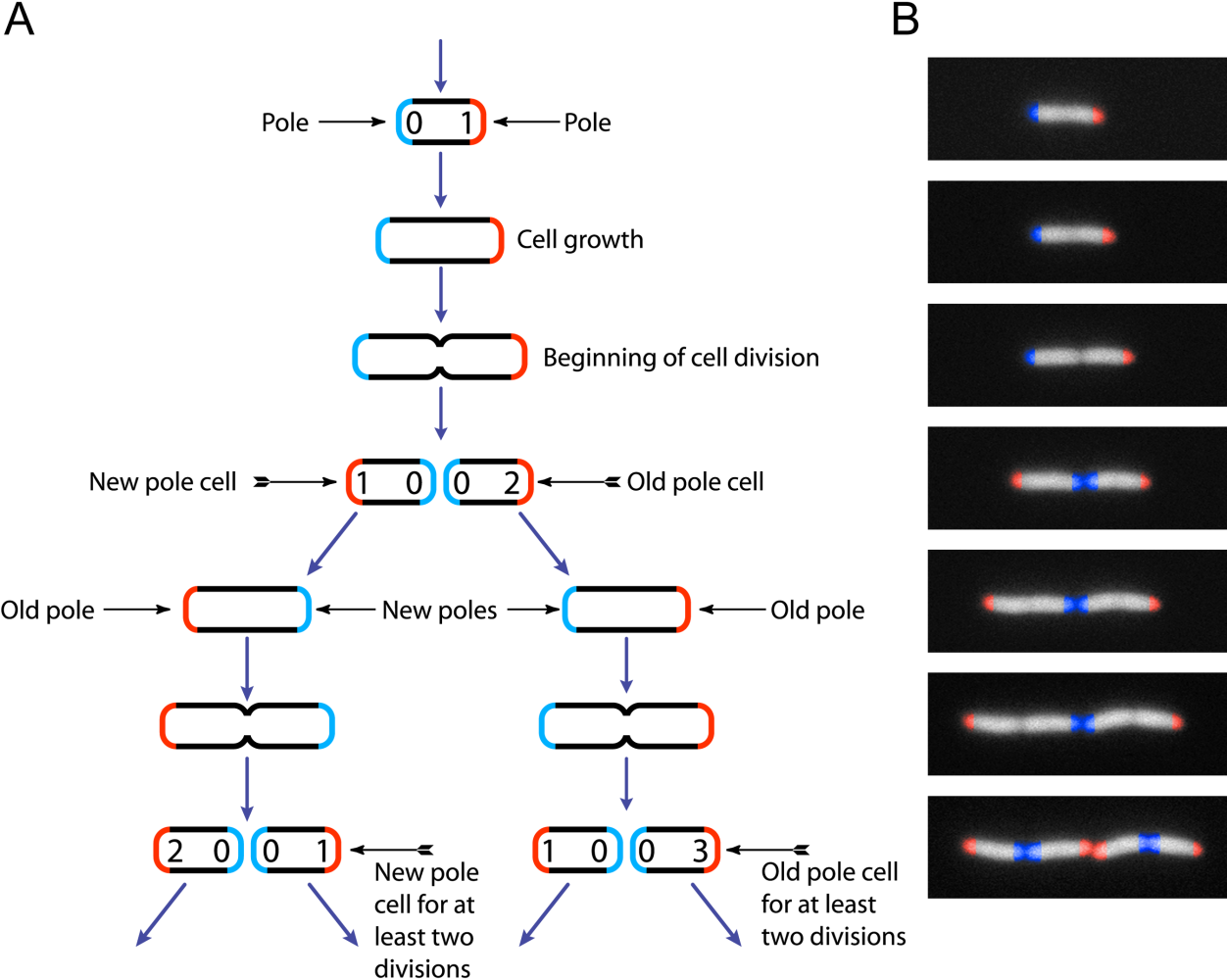

Cell cycle

The bacterial cell cycle is divided into three stages. The B period occurs between the completion of cell division and the beginning ofDNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

. The C period encompasses the time it takes to replicate the chromosomal DNA. The D period refers to the stage between the conclusion of DNA replication

In molecular biology, DNA replication is the biological process of producing two identical replicas of DNA from one original DNA molecule. DNA replication occurs in all life, living organisms, acting as the most essential part of heredity, biolog ...

and the end of cell division. The doubling rate of ''E. coli'' is higher when more nutrients are available. However, the length of the C and D periods do not change, even when the doubling time becomes less than the sum of the C and D periods. At the fastest growth rates, replication begins before the previous round of replication has completed, resulting in multiple replication forks along the DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

and overlapping cell cycles.

The number of replication forks in fast growing ''E. coli'' typically follows 2n (n = 1, 2 or 3). This only happens if replication is initiated simultaneously from all origins of replications, and is referred to as synchronous replication. However, not all cells in a culture replicate synchronously. In this case cells do not have multiples of two replication forks. Replication initiation is then referred to being asynchronous. However, asynchrony can be caused by mutations to for instance '' dnaA'' or DnaA initiator-associating protein DiaA.

Although ''E. coli'' reproduces by binary fission

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two values (0 and 1) for each digit

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical o ...

the two supposedly identical cells produced by cell division are functionally asymmetric with the old pole cell acting as an aging parent that repeatedly produces rejuvenated offspring. When exposed to an elevated stress level, damage accumulation in an old ''E. coli'' lineage may surpass its immortality threshold so that it arrests division and becomes mortal. Cellular aging is a general process, affecting prokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s and eukaryote

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

s alike.

Genetic adaptation

''E. coli'' and related bacteria possess the ability to transferDNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

via bacterial conjugation or transduction, which allows genetic material to spread horizontally through an existing population. The process of transduction, which uses the bacterial virus called a bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

, is where the spread of the gene encoding for the Shiga toxin from the ''Shigella

''Shigella'' is a genus of bacteria that is Gram negative, facultatively anaerobic, non–spore-forming, nonmotile, rod shaped, and is genetically nested within ''Escherichia''. The genus is named after Kiyoshi Shiga, who discovered it in 1 ...

'' bacteria to ''E. coli'' helped produce ''E. coli'' O157:H7, the Shiga toxin-producing strain of ''E. coli.''

Diversity

''E. coli'' encompasses an enormous population of bacteria that exhibit a very high degree of both genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genome sequencing of many isolates of ''E. coli'' and related bacteria shows that a taxonomic reclassification would be desirable. However, this has not been done, largely due to its medical importance, and ''E. coli'' remains one of the most diverse bacterial species: only 20% of the genes in a typical ''E. coli'' genome is shared among all strains.

In fact, from the more constructive point of view, the members of genus ''Shigella'' (''S. dysenteriae'', ''S. flexneri'', ''S. boydii'', and ''S. sonnei'') should be classified as ''E. coli'' strains, a phenomenon termed

''E. coli'' encompasses an enormous population of bacteria that exhibit a very high degree of both genetic and phenotypic diversity. Genome sequencing of many isolates of ''E. coli'' and related bacteria shows that a taxonomic reclassification would be desirable. However, this has not been done, largely due to its medical importance, and ''E. coli'' remains one of the most diverse bacterial species: only 20% of the genes in a typical ''E. coli'' genome is shared among all strains.

In fact, from the more constructive point of view, the members of genus ''Shigella'' (''S. dysenteriae'', ''S. flexneri'', ''S. boydii'', and ''S. sonnei'') should be classified as ''E. coli'' strains, a phenomenon termed taxa in disguise

In bacteriology, a taxon in disguise is a species, genus or higher unit of biological classification whose evolutionary history reveals has evolved from another unit of a similar or lower rank, making the parent unit paraphyly, paraphyletic. That h ...

. Similarly, other strains of ''E. coli'' (e.g. the K-12

K-1 is a professional kickboxing promotion established in 1993 by karateka Kazuyoshi Ishii.

Originally under the ownership of the Fighting and Entertainment Group (FEG), K-1 was considered to be the largest Kickboxing organization in the world. ...

strain commonly used in recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

work) are sufficiently different that they would merit reclassification.

A strain is a subgroup

In group theory, a branch of mathematics, a subset of a group G is a subgroup of G if the members of that subset form a group with respect to the group operation in G.

Formally, given a group (mathematics), group under a binary operation ...

within the species that has unique characteristics that distinguish it from other strains. These differences are often detectable only at the molecular level; however, they may result in changes to the physiology or lifecycle of the bacterium. For example, a strain may gain pathogenic capacity, the ability to use a unique carbon source, the ability to take upon a particular ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of Resource (biology), resources an ...

, or the ability to resist antimicrobial agents

An antimicrobial is an agent that kills microorganisms (microbicide) or stops their growth ( bacteriostatic agent). Antimicrobial medicines can be grouped according to the microorganisms they are used to treat. For example, antibiotics are used ag ...

. Different strains of ''E. coli'' are often host-specific, making it possible to determine the source of fecal contamination in environmental samples. For example, knowing which ''E. coli'' strains are present in a water sample allows researchers to make assumptions about whether the contamination originated from a human, another mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

, or a bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

.

Serotypes

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface

A common subdivision system of ''E. coli'', but not based on evolutionary relatedness, is by serotype, which is based on major surface antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

s (O antigen: part of lipopolysaccharide layer; H: flagellin; K antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

: capsule), e.g. O157:H7). It is, however, common to cite only the serogroup, i.e. the O-antigen. At present, about 190 serogroups are known. The common laboratory strain has a mutation that prevents the formation of an O-antigen and is thus not typeable.

Genome plasticity and evolution

Like all lifeforms, new strains of ''E. coli'' evolve through the natural biological processes ofmutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

, gene duplication

Gene duplication (or chromosomal duplication or gene amplification) is a major mechanism through which new genetic material is generated during molecular evolution. It can be defined as any duplication of a region of DNA that contains a gene ...

, and horizontal gene transfer

Horizontal gene transfer (HGT) or lateral gene transfer (LGT) is the movement of genetic material between organisms other than by the ("vertical") transmission of DNA from parent to offspring (reproduction). HGT is an important factor in the e ...

; in particular, 18% of the genome of the laboratory strain MG1655 was horizontally acquired since the divergence from ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

''. ''E. coli'' K-12 and ''E. coli'' B strains are the most frequently used varieties for laboratory purposes. Some strains develop traits that can be harmful to a host animal. These virulent strains typically cause a bout of diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

that is often self-limiting in healthy adults but is frequently lethal to children in the developing world. More virulent strains, such as O157:H7, cause serious illness or death in the elderly, the very young, or the immunocompromised

Immunodeficiency, also known as immunocompromise, is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious diseases and cancer is compromised or entirely absent. Most cases are acquired ("secondary") due to extrinsic factors that affe ...

.

The genera ''Escherichia

''Escherichia'' ( ) is a genus of Gram-negative, non-Endospore, spore-forming, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultatively anaerobic, rod-shaped bacteria from the family Enterobacteriaceae. In those species which are inhabitants of the gastroin ...

'' and ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

'' diverged around 102 million years ago (credibility interval: 57–176 mya), an event unrelated to the much earlier (see ''Synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

'') divergence of their hosts: the former being found in mammals and the latter in birds and reptiles. This was followed by a split of an ''Escherichia'' ancestor into five species ('' E. albertii'', ''E. coli'', '' E. fergusonii'', '' E. hermannii'', and '' E. vulneris''). The last ''E. coli'' ancestor split between 20 and 30 million years ago.

The long-term evolution experiments using ''E. coli'', begun by Richard Lenski in 1988, have allowed direct observation of genome evolution over more than 65,000 generations in the laboratory. For instance, ''E. coli'' typically do not have the ability to grow aerobically with citrate as a carbon source, which is used as a diagnostic criterion with which to differentiate ''E. coli'' from other, closely, related bacteria such as ''Salmonella''. In this experiment, one population of ''E. coli'' unexpectedly evolved the ability to aerobically metabolize citrate, a major evolutionary shift with some hallmarks of microbial speciation

Speciation is the evolutionary process by which populations evolve to become distinct species. The biologist Orator F. Cook coined the term in 1906 for cladogenesis, the splitting of lineages, as opposed to anagenesis, phyletic evolution within ...

. In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as '' Myxococcus xanthus''. In this predator-prey relationship, a parallel evolution of both species is observed through genomic and phenotypic modifications, in the case of ''E. coli'' the modifications are modified in two aspects involved in their virulence such as mucoid production (excessive production of exoplasmic acid alginate ) and the suppression of the OmpT gene, producing in future generations a better adaptation of one of the species that is counteracted by the evolution of the other, following a co-evolutionary model demonstrated by the Red Queen hypothesis.

In the microbial world, a relationship of predation can be established similar to that observed in the animal world. Considered, it has been seen that ''E. coli'' is the prey of multiple generalist predators, such as '' Myxococcus xanthus''. In this predator-prey relationship, a parallel evolution of both species is observed through genomic and phenotypic modifications, in the case of ''E. coli'' the modifications are modified in two aspects involved in their virulence such as mucoid production (excessive production of exoplasmic acid alginate ) and the suppression of the OmpT gene, producing in future generations a better adaptation of one of the species that is counteracted by the evolution of the other, following a co-evolutionary model demonstrated by the Red Queen hypothesis.

Neotype strain

''E. coli'' is the type species of the genus (''Escherichia'') and in turn ''Escherichia'' is the type genus of the familyEnterobacteriaceae

Enterobacteriaceae is a large family (biology), family of Gram-negative bacteria. It includes over 30 genera and more than 100 species. Its classification above the level of Family (taxonomy), family is still a subject of debate, but one class ...

, where the family name does not stem from the genus ''Enterobacter

''Enterobacter'' is a genus of common Gram-negative, Facultative anaerobic organism, facultatively anaerobic, bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, non-spore-forming bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. Cultures are found in soil, water, sewage, ...

'' + "i" (sic.) + " aceae", but from "enterobacterium" + "aceae" (enterobacterium being not a genus, but an alternative trivial name to enteric bacterium).

The original strain described by Escherich is believed to be lost, consequently a new type strain (neotype) was chosen as a representative: the neotype strain is U5/41T, also known under the deposit names DSM 30083, ATCC 11775, and NCTC 9001, which is pathogenic to chickens and has an O1:K1:H7 serotype

A serotype or serovar is a distinct variation within a species of bacteria or virus or among immune cells of different individuals. These microorganisms, viruses, or Cell (biology), cells are classified together based on their shared reactivity ...

. However, in most studies, either O157:H7, K-12 MG1655, or K-12 W3110 were used as a representative ''E. coli''. The genome of the type strain has only lately (2013) been sequenced.

Phylogeny of ''E. coli'' strains

Many strains belonging to this species have been isolated and characterised. In addition to serotype (''vide supra''), they can be classified according to theirphylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

, i.e. the inferred evolutionary history, as shown below where the species is divided into six groups as of 2014. Particularly the use of whole genome sequences yields highly supported phylogenies. The phylogroup structure remains robust to newer methods and sequences, which sometimes adds newer groups, giving 8 or 14 as of 2023.

The link between phylogenetic distance ("relatedness") and pathology is small, ''e.g.'' the O157:H7 serotype strains, which form a clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

("an exclusive group")—group E below—are all enterohaemorragic strains (EHEC), but not all EHEC strains are closely related. In fact, four different species of ''Shigella'' are nested among ''E. coli'' strains (''vide supra''), while '' E. albertii'' and '' E. fergusonii'' are outside this group. Indeed, all ''Shigella'' species were placed within a single subspecies of ''E. coli'' in a phylogenomic study that included the type strain. All commonly used research strains of ''E. coli'' belong to group A and are derived mainly from Clifton's K-12 strain (λ+ F+; O16) and to a lesser degree from d'Herelle's " Bacillus coli" strain (B strain; O7).

There have been multiple proposals to revise the taxonomy to match phylogeny. However, all these proposals need to face the fact that ''Shigella'' remains a widely used name in medicine and find ways to reduce any confusion that can stem from renaming.

Genomics

The first complete

The first complete DNA sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nu ...

of an ''E. coli'' genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

(laboratory strain K-12 derivative MG1655) was published in 1997. It is a circular DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

molecule 4.6 million base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s in length, containing 4288 annotated protein-coding genes (organized into 2584 operons), seven ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

(rRNA) operons, and 86 transfer RNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

(tRNA) genes. Despite having been the subject of intensive genetic analysis for about 40 years, many of these genes were previously unknown. The coding density was found to be very high, with a mean distance between genes of only 118 base pairs. The genome was observed to contain a significant number of transposable genetic elements, repeat elements, cryptic prophages, and bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

remnants. Most genes have only a single copy.

More than three hundred complete genomic sequences of ''Escherichia'' and ''Shigella'' species are known. The genome sequence of the type strain of ''E. coli'' was added to this collection before 2014. Comparison of these sequences shows a remarkable amount of diversity; only about 20% of each genome represents sequences present in every one of the isolates, while around 80% of each genome can vary among isolates. Each individual genome contains between 4,000 and 5,500 genes, but the total number of different genes among all of the sequenced ''E. coli'' strains (the pangenome) exceeds 16,000. This very large variety of component genes has been interpreted to mean that two-thirds of the ''E. coli'' pangenome originated in other species and arrived through the process of horizontal gene transfer.

Gene nomenclature

Genes in ''E. coli'' are usually named in accordance with the uniform nomenclature proposed by Demerec et al. Gene names are 3-letter acronyms that derive from their function (when known) or mutant phenotype and are italicized. When multiple genes have the same acronym, the different genes are designated by a capital later that follows the acronym and is also italicized. For instance, ''recA'' is named after its role inhomologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in Cell (biology), cellular organi ...

plus the letter A. Functionally related genes are named ''recB'', ''recC'', ''recD'' etc. The proteins are named by uppercase acronyms, e.g. RecA, RecB, etc. When the genome of ''E. coli'' strain K-12 substr. MG1655 was sequenced, all known or predicted protein-coding genes were numbered (more or less) in their order on the genome and abbreviated by b numbers, such as b2819 (= ''recD''). The "b" names were created after Fred Blattner, who led the genome sequence effort. Another numbering system was introduced with the sequence of another ''E. coli'' K-12 substrain, W3110, which was sequenced in Japan and hence uses numbers starting by JW... (Japanese W3110), e.g. JW2787 (= ''recD''). Hence, ''recD'' = b2819 = JW2787. Note, however, that most databases have their own numbering system, e.g. the EcoGene database uses EG10826 for ''recD''. Finally, ECK numbers are specifically used for alleles in the MG1655 strain of ''E. coli'' K-12. Complete lists of genes and their synonyms can be obtained from databases such as EcoGene or Uniprot

UniProt is a freely accessible database of protein sequence and functional information, many entries being derived from genome sequencing projects. It contains a large amount of information about the biological function of proteins derived fro ...

.

Proteomics

Proteome

The genome sequence of ''E. coli'' predicts 4288 protein-coding genes, of which 38 percent initially had no attributed function. Comparison with five other sequenced microbes reveals ubiquitous as well as narrowly distributed gene families; many families of similar genes within ''E. coli'' are also evident. The largest family of paralogous proteins contains 80 ABC transporters. The genome as a whole is strikingly organized with respect to the local direction of replication; guanines, oligonucleotides possibly related to replication and recombination, and most genes are so oriented. The genome also contains insertion sequence (IS) elements, phage remnants, and many other patches of unusual composition indicating genome plasticity through horizontal transfer. Several studies have experimentally investigated theproteome

A proteome is the entire set of proteins that is, or can be, expressed by a genome, cell, tissue, or organism at a certain time. It is the set of expressed proteins in a given type of cell or organism, at a given time, under defined conditions. P ...

of ''E. coli''. By 2006, 1,627 (38%) of the predicted proteins ( open reading frames, ORFs) had been identified experimentally. Mateus et al. 2020 detected 2,586 proteins with at least 2 peptides (60% of all proteins).

Post-translational modifications (PTMs)

Although much fewer bacterial proteins seem to havepost-translational modification

In molecular biology, post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent process of changing proteins following protein biosynthesis. PTMs may involve enzymes or occur spontaneously. Proteins are created by ribosomes, which translation (biolog ...

s (PTMs) compared to eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

proteins, a substantial number of proteins are modified in ''E. coli''. For instance, Potel et al. (2018) found 227 phosphoproteins of which 173 were phosphorylated on histidine

Histidine (symbol His or H) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an Amine, α-amino group (which is in the protonated –NH3+ form under Physiological condition, biological conditions), a carboxylic ...

. The majority of phosphorylated amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s were serine (1,220 sites) with only 246 sites on histidine

Histidine (symbol His or H) is an essential amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an Amine, α-amino group (which is in the protonated –NH3+ form under Physiological condition, biological conditions), a carboxylic ...

and 501 phosphorylated threonine

Threonine (symbol Thr or T) is an amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form when dissolved in water), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated −COO− ...

s and 162 tyrosines.

Interactome

The interactome of ''E. coli'' has been studied by affinity purification andmass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry (MS) is an analytical technique that is used to measure the mass-to-charge ratio of ions. The results are presented as a ''mass spectrum'', a plot of intensity as a function of the mass-to-charge ratio. Mass spectrometry is used ...

(AP/MS) and by analyzing the binary interactions among its proteins.

Protein complexes. A 2006 study purified 4,339 proteins from cultures of strain K-12 and found interacting partners for 2,667 proteins, many of which had unknown functions at the time. A 2009 study found 5,993 interactions between proteins of the same ''E. coli'' strain, though these data showed little overlap with those of the 2006 publication.

Binary interactions. Rajagopala ''et al.'' (2014) have carried out systematic yeast two-hybrid screens with most ''E. coli'' proteins, and found a total of 2,234 protein-protein interactions. This study also integrated genetic interactions and protein structures and mapped 458 interactions within 227 protein complexes

A protein complex or multiprotein complex is a group of two or more associated polypeptide chains. Protein complexes are distinct from multidomain enzymes, in which multiple catalytic domains are found in a single polypeptide chain.

Protein c ...

.

Normal microbiota

''E. coli'' belongs to a group of bacteria informally known as coliforms that are found in the gastrointestinal tract of warm-blooded animals. ''E. coli'' normally colonizes an infant'sgastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

within 40 hours of birth, arriving with food or water or from the individuals handling the child. In the bowel, ''E. coli'' adheres to the mucus

Mucus (, ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both Serous fluid, serous and muc ...

of the large intestine

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the Digestion, digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces befor ...

. It is the primary facultative anaerobe of the human gastrointestinal tract. ( Facultative anaerobes are organisms that can grow in either the presence or absence of oxygen.) As long as these bacteria do not acquire genetic elements encoding for virulence factors, they remain benign commensals.

Therapeutic use

Due to the low cost and speed with which it can be grown and modified in laboratory settings, ''E. coli'' is a popular expression platform for the production of recombinant proteins used in therapeutics. One advantage to using ''E. coli'' over another expression platform is that ''E. coli'' naturally does not export many proteins into the periplasm, making it easier to recover a protein of interest without cross-contamination. The ''E. coli'' K-12 strains and their derivatives (DH1, DH5α, MG1655, RV308 and W3110) are the strains most widely used by the biotechnology industry. Nonpathogenic ''E. coli'' strain Nissle 1917 (EcN), (Mutaflor) and ''E. coli'' O83:K24:H31 (Colinfant)) are used as probiotic agents in medicine, mainly for the treatment of variousgastrointestinal disease

Gastrointestinal diseases (abbrev. GI diseases or GI illnesses) refer to diseases involving the Human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract, namely the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine and rectum; and the accessory or ...

s, including inflammatory bowel disease

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a group of inflammatory conditions of the colon and small intestine, with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis (UC) being the principal types. Crohn's disease affects the small intestine and large intestine ...

. It is thought that the EcN strain might impede the growth of opportunistic pathogens, including ''Salmonella

''Salmonella'' is a genus of bacillus (shape), rod-shaped, (bacillus) Gram-negative bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae. The two known species of ''Salmonella'' are ''Salmonella enterica'' and ''Salmonella bongori''. ''S. enterica'' ...

'' and other coliform enteropathogens, through the production of microcin proteins the production of siderophores.

Role in disease

Most ''E. coli'' strains do not cause disease, naturally living in the gut, but virulent strains can causegastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea, is an inflammation of the Human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract including the stomach and intestine. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of ...

, urinary tract infections, neonatal meningitis, hemorrhagic colitis, and Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms often include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, abdominal distension, and weight loss. Complications outside of the ...

. Common signs and symptoms include severe abdominal cramps, diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, vomiting, and sometimes fever. In rarer cases, virulent strains are also responsible for bowel necrosis (tissue death) and perforation without progressing to hemolytic–uremic syndrome, peritonitis, mastitis, sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

, and gram-negative pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

. Very young children are more susceptible to develop severe illness, such as hemolytic uremic syndrome; however, healthy individuals of all ages are at risk to the severe consequences that may arise as a result of being infected with ''E. coli''.

Some strains of ''E. coli'', for example O157:H7, can produce Shiga toxin. The Shiga toxin causes inflammatory responses in target cells of the gut, leaving behind lesions which result in the bloody diarrhea that is a symptom of a Shiga toxin-producing ''E. coli'' (STEC) infection. This toxin further causes premature destruction of the red blood cells, which then clog the body's filtering system, the kidneys, in some rare cases (usually in children and the elderly) causing hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), which may lead to kidney failure and even death. Signs of hemolytic uremic syndrome include decreased frequency of urination, lethargy, and paleness of cheeks and inside the lower eyelids. In 25% of HUS patients, complications of nervous system occur, which in turn causes stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

s. In addition, this strain causes the buildup of fluid (since the kidneys do not work), leading to edema around the lungs, legs, and arms. This increase in fluid buildup especially around the lungs impedes the functioning of the heart, causing an increase in blood pressure.

Uropathogenic ''E. coli'' (UPEC) is one of the main causes of urinary tract infections. It is part of the normal microbiota in the gut and can be introduced in many ways. In particular for females, the direction of wiping after defecation (wiping back to front) can lead to fecal contamination of the urogenital orifices. Anal intercourse can also introduce this bacterium into the male urethra, and in switching from anal to vaginal intercourse, the male can also introduce UPEC to the female urogenital system.

Enterotoxigenic ''E. coli'' (ETEC) is the most common cause of traveler's diarrhea, with as many as 840 million cases worldwide in developing countries each year. The bacteria, typically transmitted through contaminated food or drinking water, adheres to the intestinal lining, where it secretes either of two types of enterotoxins, leading to watery diarrhea. The rate and severity of infections are higher among children under the age of five, including as many as 380,000 deaths annually.

In May 2011, one ''E. coli'' strain, O104:H4, was the subject of a bacterial outbreak that began in Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

. Certain strains of ''E. coli'' are a major cause of foodborne illness

Foodborne illness (also known as foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the contamination of food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease), and toxins such ...

. The outbreak started when several people in Germany were infected with enterohemorrhagic ''E. coli'' (EHEC) bacteria, leading to hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS), a medical emergency that requires urgent treatment. The outbreak did not only concern Germany, but also 15 other countries, including regions in North America. On 30 June 2011, the German ''Bundesinstitut für Risikobewertung (BfR)'' (Federal Institute for Risk Assessment, a federal institute within the German Federal Ministry of Food, Agriculture and Consumer Protection) announced that seeds of fenugreek from Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

were likely the cause of the EHEC outbreak.

Some studies have demonstrated an absence of ''E. coli'' in the gut flora of subjects with the metabolic disorder Phenylketonuria. It is hypothesized that the absence of these normal bacterium impairs the production of the key vitamins B2 (riboflavin) and K2 (menaquinone) – vitamins which are implicated in many physiological roles in humans such as cellular and bone metabolism – and so contributes to the disorder.

Carbapenem-resistant ''E. coli'' (carbapenemase-producing ''E. coli'') that are resistant to the carbapenem

Carbapenems are a class of very effective antibiotic agents most commonly used for treatment of severe bacterial infections. This class of antibiotics is usually reserved for known or suspected multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections. Si ...

class of antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

, considered the drugs of last resort for such infections. They are resistant because they produce an enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

called a carbapenemase that disables the drug molecule.

Incubation period

The time between ingesting the STEC bacteria and feeling sick is called the "incubation period". The incubation period is usually 3–4 days after the exposure, but may be as short as 1 day or as long as 10 days. The symptoms often begin slowly with mild belly pain or non-bloody diarrhea that worsens over several days. HUS, if it occurs, develops an average 7 days after the first symptoms, when the diarrhea is improving.Diagnosis

Diagnosis of infectious diarrhea and identification of antimicrobial resistance is performed using a stool culture with subsequent antibiotic sensitivity testing. It requires a minimum of 2 days and maximum of several weeks to culture gastrointestinal pathogens. The sensitivity (true positive) and specificity (true negative) rates for stool culture vary by pathogen, although a number of human pathogens can not be cultured. For culture-positive samples, antimicrobial resistance testing takes an additional 12–24 hours to perform. Current point of care molecular diagnostic tests can identify ''E. coli'' and antimicrobial resistance in the identified strains much faster than culture and sensitivity testing. Microarray-based platforms can identify specific pathogenic strains of ''E. coli'' and ''E. coli''-specific AMR genes in two hours or less with high sensitivity and specificity, but the size of the test panel (i.e., total pathogens and antimicrobial resistance genes) is limited. Newer metagenomics-based infectious disease diagnostic platforms are currently being developed to overcome the various limitations of culture and all currently available molecular diagnostic technologies.Treatment

The mainstay of treatment is the assessment ofdehydration

In physiology, dehydration is a lack of total body water that disrupts metabolic processes. It occurs when free water loss exceeds intake, often resulting from excessive sweating, health conditions, or inadequate consumption of water. Mild deh ...

and replacement of fluid and electrolytes. Administration of antibiotics

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

has been shown to shorten the course of illness and duration of excretion of enterotoxigenic ''E. coli'' (ETEC) in adults in endemic areas and in traveller's diarrhea, though the rate of resistance to commonly used antibiotics is increasing and they are generally not recommended. The antibiotic used depends upon susceptibility patterns in the particular geographical region. Currently, the antibiotics of choice are fluoroquinolones or azithromycin

Azithromycin, sold under the brand names Zithromax (in oral form) and Azasite (as an eye drop), is an antibiotic medication used for the treatment of several bacterial infections. This includes otitis media, middle ear infections, strep throa ...

, with an emerging role for rifaximin

Rifaximin is a non-absorbable, broad-spectrum antibiotic mainly used to treat travelers' diarrhea. It is based on the rifamycin antibiotics family. Since its approval in Italy in 1987, it has been licensed in more than 30 countries for the t ...

. Rifaximin, a semisynthetic rifamycin derivative, is an effective and well-tolerated antibacterial for the management of adults with non-invasive traveller's diarrhea. Rifaximin was significantly more effective than placebo and no less effective than ciprofloxacin

Ciprofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections. This includes bone and joint infections, intra-abdominal infections, certain types of infectious diarrhea, respiratory tract infections, skin ...

in reducing the duration of diarrhea. While rifaximin is effective in patients with ''E. coli''-predominant traveller's diarrhea, it appears ineffective in patients infected with inflammatory or invasive enteropathogens.

Prevention

ETEC is the type of ''E. coli'' that most vaccine development efforts are focused on.Antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

against the LT and major CFs of ETEC provide protection against LT-producing, ETEC-expressing homologous CFs. Oral inactivated vaccines consisting of toxin antigen and whole cells, i.e. the licensed recombinant cholera B subunit (rCTB)-WC cholera vaccine Dukoral, have been developed. There are currently no licensed vaccines for ETEC, though several are in various stages of development. In different trials, the rCTB-WC cholera vaccine provided high (85–100%) short-term protection. An oral ETEC vaccine candidate consisting of rCTB and formalin inactivated ''E. coli'' bacteria expressing major CFs has been shown in clinical trials to be safe, immunogenic, and effective against severe diarrhoea in American travelers but not against ETEC diarrhoea in young children in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

. A modified ETEC vaccine consisting of recombinant ''E. coli'' strains over-expressing the major CFs and a more LT-like hybrid toxoid called LCTBA, are undergoing clinical testing.

Other proven prevention methods for ''E. coli'' transmission include handwashing and improved sanitation and drinking water, as transmission occurs through fecal contamination of food and water supplies. Additionally, thoroughly cooking meat and avoiding consumption of raw, unpasteurized beverages, such as juices and milk are other proven methods for preventing ''E. coli''. Lastly, cross-contamination of utensils and work spaces should be avoided when preparing food.

Model organism in life science research

Because of its long history of laboratory culture and ease of manipulation, ''E. coli'' plays an important role in modern biological engineering andindustrial microbiology

Industrial microbiology is a branch of biotechnology that applies microbial sciences to create industrial products in mass quantities, often using Microbial cell factory, microbial cell factories. There are multiple ways to manipulate a microorgani ...

. The work of Stanley Norman Cohen and Herbert Boyer in ''E. coli'', using plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

s and restriction enzyme

A restriction enzyme, restriction endonuclease, REase, ENase or'' restrictase '' is an enzyme that cleaves DNA into fragments at or near specific recognition sites within molecules known as restriction sites. Restriction enzymes are one class o ...

s to create recombinant DNA

Recombinant DNA (rDNA) molecules are DNA molecules formed by laboratory methods of genetic recombination (such as molecular cloning) that bring together genetic material from multiple sources, creating sequences that would not otherwise be fo ...

, became a foundation of biotechnology.

''E. coli'' is a very versatile host for the production of heterologous protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s, and various protein expression systems have been developed which allow the production of recombinant proteins in ''E. coli''. Researchers can introduce genes into the microbes using plasmids which permit high level expression of protein, and such protein may be mass-produced in industrial fermentation

Industrial fermentation is the intentional use of fermentation in manufacturing processes. In addition to the mass production of fermented foods and drinks, industrial fermentation has widespread applications in chemical industry. Commodity ch ...

processes. One of the first useful applications of recombinant DNA technology was the manipulation of ''E. coli'' to produce human insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

.

Many proteins previously thought difficult or impossible to be expressed in ''E. coli'' in folded form have been successfully expressed in ''E. coli''. For example, proteins with multiple disulphide bonds may be produced in the periplasmic space or in the cytoplasm of mutants rendered sufficiently oxidizing to allow disulphide-bonds to form, while proteins requiring post-translational modification

In molecular biology, post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent process of changing proteins following protein biosynthesis. PTMs may involve enzymes or occur spontaneously. Proteins are created by ribosomes, which translation (biolog ...

such as glycosylation

Glycosylation is the reaction in which a carbohydrate (or ' glycan'), i.e. a glycosyl donor, is attached to a hydroxyl or other functional group of another molecule (a glycosyl acceptor) in order to form a glycoconjugate. In biology (but not ...

for stability or function have been expressed using the N-linked glycosylation system of ''Campylobacter jejuni

''Campylobacter jejuni'' is a species of pathogenic bacteria that is commonly associated with poultry, and is also often found in animal feces. This species of microbe is one of the most common causes of food poisoning in Europe and in the US, w ...

'' engineered into ''E. coli''.

Modified ''E. coli'' cells have been used in vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

development, bioremediation

Bioremediation broadly refers to any process wherein a biological system (typically bacteria, microalgae, fungi in mycoremediation, and plants in phytoremediation), living or dead, is employed for removing environmental pollutants from air, wate ...

, production of biofuels

Biofuel is a fuel that is produced over a short time span from biomass, rather than by the very slow natural processes involved in the formation of fossil fuels such as oil. Biofuel can be produced from plants or from agricultural, domestic ...

, lighting, and production of immobilised enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s.

Strain K-12 is a mutant form of ''E. coli'' that over-expresses the enzyme Alkaline phosphatase (ALP). The mutation arises due to a defect in the gene that constantly codes for the enzyme. A gene that is producing a product without any inhibition is said to have constitutive activity. This particular mutant form is used to isolate and purify the aforementioned enzyme.

Strain OP50 of ''Escherichia coli'' is used for maintenance of ''Caenorhabditis elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a Hybrid word, blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''r ...

'' cultures.

Strain JM109 is a mutant form of ''E. coli'' that is recA and endA deficient. The strain can be utilized for blue/white screening when the cells carry the fertility factor episome. Lack of recA decreases the possibility of unwanted restriction of the DNA of interest and lack of endA inhibit plasmid DNA decomposition. Thus, JM109 is useful for cloning and expression systems.

Model organism

''E. coli'' is frequently used as a model organism in

''E. coli'' is frequently used as a model organism in microbiology

Microbiology () is the branches of science, scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular organism, unicellular (single-celled), multicellular organism, multicellular (consisting of complex cells), or non-cellular life, acellula ...

studies. Cultivated strains (e.g. ''E. coli'' K12) are well-adapted to the laboratory environment, and, unlike wild-type

The wild type (WT) is the phenotype of the typical form of a species as it occurs in nature. Originally, the wild type was conceptualized as a product of the standard "normal" allele at a locus, in contrast to that produced by a non-standard, " ...

strains, have lost their ability to thrive in the intestine. Many laboratory strains lose their ability to form biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s. These features protect wild-type strains from antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...