The Cultural Revolution, formally known as the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, was a

sociopolitical movement in the

People's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(PRC). It was launched by

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; traditionally Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Mao Tse-tung. (26December 18939September 1976) was a Chinese politician, revolutionary, and political theorist who founded the People's Republic of China (PRC) in ...

in 1966 and lasted until his death in 1976. Its stated goal was to preserve

Chinese socialism by purging remnants of

capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and

traditional elements from

Chinese society.

In May 1966, with the help of the

Cultural Revolution Group

The Central Cultural Revolution Group (CRG or CCRG; ) was formed in May 1966 as a replacement organisation to the Secretariat of the Chinese Communist Party and the Five Man Group, and was initially directly responsible to the Politburo Standi ...

, Mao launched the Revolution and said that

bourgeois elements had infiltrated the government and society with the aim of restoring capitalism. Mao called on young people to

bombard the headquarters, and proclaimed that "to rebel is justified". Mass upheaval began in

Beijing

Beijing, Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Peking, is the capital city of China. With more than 22 million residents, it is the world's List of national capitals by population, most populous national capital city as well as ...

with

Red August in 1966. Many young people, mainly students, responded by forming

cadres of

Red Guards

The Red Guards () were a mass, student-led, paramilitary social movement mobilized by Chairman Mao Zedong in 1966 until their abolition in 1968, during the first phase of the Cultural Revolution, which he had instituted.Teiwes

According to a ...

throughout the country. ''

Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung'' became revered within

his cult of personality. In 1967, emboldened radicals began

seizing power from local governments and party branches, establishing new

revolutionary committees in their place while

smashing public security, procuratorate and judicial systems. These committees often split into rival factions, precipitating

armed clashes among the radicals. After the

fall of Lin Biao in 1971, the

Gang of Four

The Gang of Four () was a Maoist political faction composed of four Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials. They came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and were later charged with a series of treasonous crimes due to th ...

became influential in 1972, and the Revolution continued until Mao's death in 1976, soon followed by the

arrest

An arrest is the act of apprehending and taking a person into custody (legal protection or control), usually because the person has been suspected of or observed committing a crime. After being taken into custody, the person can be question ...

of the Gang of Four.

The Cultural Revolution was characterized by violence and chaos across Chinese society. Estimates of the death toll vary widely, typically ranging from 1–2 million, including

a massacre in Guangxi that included acts of

cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

, as well as massacres in Beijing,

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

,

Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

,

Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

, and

Hunan

Hunan is an inland Provinces of China, province in Central China. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the Administrative divisions of China, province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi to the east, Gu ...

.

Red Guards sought to destroy the

Four Olds

The Four Olds () refer to categories used by the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution to characterize elements of Chinese culture prior to the Chinese Communist Revolution that they were attempting to destroy. The Four Olds were 'old ideas ...

(old ideas, old culture, old customs, and old habits), which often took the form of destroying historical artifacts and cultural and religious sites. Tens of millions were persecuted, including senior officials such as

Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi ( ; 24 November 189812 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary and politician. He was the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 1954 to 1959, first-ranking Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communis ...

,

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

and

Peng Dehuai

Peng Dehuai (October 24, 1898November 29, 1974; also spelled as Peng Teh-Huai) was a Chinese general and politician who was the Minister of National Defense (China), Minister of National Defense from 1954 to 1959. Peng was born into a poor ...

; millions were persecuted for being members of the

Five Black Categories, with intellectuals and scientists labelled as the

Stinking Old Ninth. The country's schools and universities were closed, and the

National College Entrance Examination

The Nationwide Unified Examination for Admissions to General Universities and Colleges (), commonly abbreviated as the Gaokao (), is the annual nationally coordinated undergraduate admission exam in mainland China, held in early June. Despite the ...

s were cancelled. Over 10 million

youth from urban areas were relocated under the

Down to the Countryside Movement

The Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement, often known simply as the Down to the Countryside Movement, was a policy instituted in the China, People's Republic of China between the mid-1950s and 1978. As a result of what he p ...

.

In December 1978, Deng Xiaoping became the new

paramount leader of China

Paramount leader () is an informal term for the most important political figure in the People's Republic of China (PRC). The paramount leader typically controls the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People's Liberation Army (PLA), often ho ...

, replacing Mao's successor

Hua Guofeng

Hua Guofeng (born Su Zhu (); 16 February 1921 – 20 August 2008) was a Chinese politician who served as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party and the 2nd premier of China. The designated successor of Mao Zedong, Hua held the top offices of t ...

. Deng and his allies introduced the ''

Boluan Fanzheng

''Boluan Fanzheng'' () refers to a period of significant sociopolitical reforms starting with the accession of Deng Xiaoping to the paramount leader of China, paramount leadership in China, replacing Hua Guofeng, who had been appointed as Mao Z ...

'' program and initiated

economic reforms, which, together with the

New Enlightenment movement, gradually dismantled the ideology of Cultural Revolution. In 1981, the Communist Party publicly acknowledged numerous failures of the Cultural Revolution, declaring it "responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the people, the country, and the party since the founding of the People's Republic." Given its broad scope and social impact, memories and perspectives of the Cultural Revolution are varied and complex in contemporary China. It is often referred to as the "ten years of chaos" () or "ten years of havoc" ().

Etymology

The terminology of cultural revolution appeared in communist party discourses and newspapers prior to the founding of the People's Republic of China. During this period, the term was used interchangeably with "cultural construction" and referred to eliminating illiteracy in order to widen public participation in civic matters. This usage of "cultural revolution" continued through the 1950s and into the 1960s, and often involved drawing parallels to the

May Fourth Movement

The May Fourth Movement was a Chinese cultural and anti-imperialist political movement which grew out of student protests in Beijing on May 4, 1919. Students gathered in front of Tiananmen to protest the Chinese government's weak response ...

or the

Soviet cultural revolution of 1928–1931.

Background

Creation of the People's Republic

On 1 October 1949, Mao Zedong declared the People's Republic of China, symbolically bringing the decades-long

Chinese Civil War

The Chinese Civil War was fought between the Kuomintang-led Nationalist government, government of the Republic of China (1912–1949), Republic of China and the forces of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Armed conflict continued intermitt ...

to a close. Remaining

Republican forces fled to

Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

and continued to resist the People's Republic in various ways. Many soldiers of the Chinese Republicans were left in mainland China, and Mao Zedong launched the

Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries to eliminate these soldiers left behind, as well as elements of Chinese society viewed as potentially dangerous to Mao's new government.

Great Leap Forward

The Great Leap Forward, similar to the

Five-year plans of the Soviet Union

The five-year plans for the development of the national economy of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) (, ''pyatiletniye plany razvitiya narodnogo khozyaystva SSSR'') consisted of a series of nationwide Centralized planning, centraliz ...

, was Mao Zedong's proposal to make the newly created People's Republic of China an industrial superpower. Beginning in 1958, the Great Leap Forward did produce, at least on the surface, incredible industrialization, but also caused the

Great Chinese Famine, while still falling short of projected goals.

In early 1962, at CCP's

Seven Thousand Cadres Conference, Mao made

self-criticism

Self-criticism involves how an individual evaluates oneself. Self-criticism in psychology is typically studied and discussed as a negative personality trait in which a person has a disrupted self-identity. The opposite of self-criticism would be ...

, after which he took a semi-retired role, leaving future responsibilities to

Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi ( ; 24 November 189812 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary and politician. He was the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 1954 to 1959, first-ranking Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communis ...

and

Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

.

Impact of international tensions and anti-revisionism

In the early 1950s, the PRC and the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

(USSR) were the world's two largest communist states. Although initially they were mutually supportive, disagreements arose after

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

took power in the USSR. In 1956, Khrushchev

denounced his predecessor Josef Stalin and his policies, and began implementing

economic reforms. Mao and many other CCP members opposed these changes, believing that they would damage the worldwide communist movement.

Mao believed that Khrushchev was a

revisionist, altering

Marxist–Leninist concepts, which Mao claimed would give capitalists control of the USSR. Relations soured. The USSR refused to support China's case for joining the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

and reneged on its pledge to supply China with a nuclear weapon.

[

Mao denounced revisionism in April 1960. Without pointing at the USSR, Mao criticized its Balkan ally, the ]League of Communists of Yugoslavia

The League of Communists of Yugoslavia, known until 1952 as the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, was the founding and ruling party of SFR Yugoslavia. It was formed in 1919 as the main communist opposition party in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats ...

. In turn, the USSR criticized China's Balkan ally, the Party of Labour of Albania

The Party of Labour of Albania (PLA), also referred to as the Albanian Workers' Party (AWP), was the ruling and sole legal party of Albania during the communist period (1945–1991). It was founded on 8 November 1941 as the Communist Party of ...

. In 1963, CCP began to denounce the USSR, publishing nine polemics.[

Other Soviet actions increased concerns about potential fifth columnists. As a result of the tensions following the Sino-Soviet split, Soviet leaders authorized radio broadcasts into China stating that the Soviet Union would assist "genuine communists" who overthrew Mao and his "erroneous course".]North Vietnam

North Vietnam, officially the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRV; ; VNDCCH), was a country in Southeast Asia from 1945 to 1976, with sovereignty fully recognized in 1954 Geneva Conference, 1954. A member of the communist Eastern Bloc, it o ...

, concerned that China's support would lead to the United States to seek out potential Chinese assets.

Views of revolutionary practice

Mao contended that capitalist tendencies had begun to grow in China.Tao Zhu

Tao Zhu (; 16 January 1908 – 30 November 1969) was a member of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

Biography

Tao was born in Qiyang, Qiyang County, Hunan, on 16 January 1908.

He was imprisoned in Nanjing by the K ...

stated:

Socialist Education Movement and ''Hai Rui Dismissed from Office''

In 1963, Mao launched the

In 1963, Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement

__NOTOC__

The Socialist Education Movement (, abbreviated 社教运动 or 社教運動), also known as the Four Cleanups Movement () was a 1963–1965 movement launched by Mao Zedong in the People's Republic of China. Mao sought to remove reactio ...

.Hai Rui Dismissed from Office

''Hai Rui Dismissed from Office'' (; also called ''Dismissal of Hai Jui'' in English) is a stage play, written by Wu Han (1909–1969), notable for its involvement in Chinese politics during the Cultural Revolution. The play itself focused on ...

''. In the play, an honest civil servant

The civil service is a collective term for a sector of government composed mainly of career civil service personnel hired rather than elected, whose institutional tenure typically survives transitions of political leadership. A civil service offic ...

, Hai Rui

Hai Rui (January 23, 1514 – November 13, 1587), courtesy name Ru Xian (), art name Gang Feng (), was a Chinese scholar-official, philosopher and politician of the Ming dynasty, remembered as a model of honesty and integrity in office.

Biograp ...

, is dismissed by a corrupt emperor. While Mao initially praised the play, in February 1965, he secretly commissioned Jiang Qing

Jiang Qing (March 191414 May 1991), also known as Madame Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary, actress, and political figure. She was the fourth wife of Mao Zedong, the Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, Chairman of the Communis ...

and Yao Wenyuan to publish an article criticizing it. Yao described the play as an allegory attacking Mao; flagging Mao as the emperor, and Peng Dehuai, who had previously questioned Mao during the Lushan Conference

The Lushan Conference was a meeting of the top leaders of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) held between July and August 1959. The Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party, CCP Politburo met in an "expanded session" (''Kuoda Huiyi'') between July ...

, as the honest civil servant.Peng Zhen

Peng Zhen (pronounced ; October 12, 1902 – April 26, 1997) was a Chinese politician and leading member of the Chinese Communist Party. He led the party organization in Beijing following the victory of the Communists in the Chinese Civil War i ...

on the defensive. Peng, Wu Han's direct superior, was the head of the Five Man Group

The Five Man Group (; also known as the Group of Five) was an informal committee established in the People's Republic of China in early 1965 to explore the potential for a "cultural revolution" in China. The group was led by Peng Zhen (the mayor ...

, a committee commissioned by Mao to study the potential for a cultural revolution. Peng Zhen, aware that he would be implicated if Wu indeed wrote an "anti-Mao" play, wished to contain Yao's influence. Yao's article was initially published only in select local newspapers. Peng forbade its publication in the nationally distributed ''People's Daily

The ''People's Daily'' ( zh, s=人民日报, p=Rénmín Rìbào) is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP in multiple lan ...

'' and other major newspapers under his control, and not pay heed to Yao's petty politics.Yang Shangkun

Yang Shangkun (3 August 1907 – 14 September 1998) was a Chinese Chinese Communist Party, Communist military and political leader, president of the People's Republic of China from 1988 to 1993, and one of the Eight Elders that dominated the par ...

—director of the party's General Office, an organ that controlled internal communications—making unsubstantiated charges. He installed loyalist Wang Dongxing, head of Mao's security detail. Yang's dismissal likely emboldened Mao's allies to move against their factional rivals.Kang Sheng

Kang Sheng (; 4 November 1898 – 16 December 1975), born Zhang Zongke (), was a Chinese Communist Party (CCP) official, politician and calligrapher best known for having overseen the work of the CCP's internal security and intelligence appara ...

and Chen Boda

Chen Boda (; 29 July 1904 – 20 September 1989), was a Chinese Communist journalist, professor and political theorist who rose to power as the chief interpreter of Maoism (or "Mao Zedong Thought") in the first 20 years of the People's Republi ...

. They accused Peng of opposing Mao, labeled the ''February Outline'' "evidence of Peng Zhen's revisionism", and grouped him with three other disgraced officials as part of the "Peng-Luo-Lu-Yang Anti-Party Clique".

1966: Outbreak

The Cultural Revolution can be divided into two main periods:

* spring 1966 to summer 1968 (when most of the key events took place)

* a tailing period that lasted until fall 1976

Notification

In May 1966, an expanded session of the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

was called in Beijing. The conference was laden with Maoist political rhetoric on class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

and filled with meticulously prepared 'indictments' of recently ousted leaders such as Peng Zhen and Luo Ruiqing

Luo Ruiqing (; May 31, 1906 – August 3, 1978), formerly romanized as Lo Jui-ch'ing, was a People's Republic of China, Chinese army officer and politician, general of the People's Liberation Army. As the first Ministry of Public Security ...

. One of these documents, distributed on 16 May, was prepared with Mao's personal supervision and was particularly damning:

Those representatives of the bourgeoisie who have sneaked into the Party, the government, the army, and various spheres of culture are a bunch of counter-revolutionary revisionists. Once conditions are ripe, they will seize political power and turn the dictatorship of the proletariat into a dictatorship of the bourgeoisie. Some of them we have already seen through; others we have not. Some are still trusted by us and are being trained as our successors, persons like Khrushchev for example, who are still nestling beside us.

Later known as the "16 May Notification", this document summarized Mao's ideological justification for CR. Initially kept secret, distributed only among high-ranking party members, it was later declassified and published in ''People's Daily

The ''People's Daily'' ( zh, s=人民日报, p=Rénmín Rìbào) is the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It provides direct information on the policies and viewpoints of the CCP in multiple lan ...

'' on 17 May 1967. Effectively it implied that enemies of the Communist cause could be found within the Party: class enemies who "wave the red flag to oppose the red flag." The only way to identify these people was through "the telescope and microscope of Mao Zedong Thought

Maoism, officially Mao Zedong Thought, is a variety of Marxism–Leninism that Mao Zedong developed while trying to realize a socialist revolution in the agricultural, pre-industrial society of the Republic of China and later the People's Re ...

." While the party leadership was relatively united in approving Mao's agenda, many Politburo members were not enthusiastic, or simply confused about the direction.

Mass rallies (May–June)

After the purge of Peng Zhen, the Beijing Party Committee effectively ceased to function, paving the way for disorder in the capital. On 25 May, under the guidance of —wife of Mao loyalist Kang Sheng—Nie Yuanzi

Nie Yuanzi (5 April 1921 – 28 August 2019) was a Chinese academic administrator at Peking University, known for writing a big-character poster criticising the university for being controlled by the bourgeoisie, which is considered to have be ...

, a philosophy lecturer at Peking University

Peking University (PKU) is a Public university, public Types of universities and colleges in China#By designated academic emphasis, university in Haidian, Beijing, China. It is affiliated with and funded by the Ministry of Education of the Peop ...

, authored a big-character poster

Big-character posters () are handwritten posters displaying large Chinese characters, usually mounted on walls in public spaces such as universities, factories, government departments, and sometimes directly on the streets. They are used as a me ...

along with other leftists and posted it to a public bulletin. Nie attacked the university's party administration and its leader Lu Ping. Nie insinuated that the university leadership, much like Peng, were trying to contain revolutionary fervor in a "sinister" attempt to oppose the party and advance revisionism.[

Mao promptly endorsed Nie's poster as "the first Marxist big-character poster in China". Approved by Mao, the poster rippled across educational institutions. Students began to revolt against their school's party establishments. Classes were cancelled in Beijing primary and secondary schools, followed by a decision on 13 June to expand the class suspension nationwide. By early June, throngs of young demonstrators lined the capital's major thoroughfares holding giant portraits of Mao, beating drums, and shouting slogans.][

When the dismissal of Peng and the municipal party leadership became public in early June, confusion was widespread. The public and foreign missions were kept in the dark on the reason for Peng's ousting. Top Party leadership was caught off guard by the sudden protest wave and struggled with how to respond. After seeking Mao's guidance in ]Hangzhou

Hangzhou, , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ; formerly romanized as Hangchow is a sub-provincial city in East China and the capital of Zhejiang province. With a population of 13 million, the municipality comprises ten districts, two counti ...

, Liu Shaoqi

Liu Shaoqi ( ; 24 November 189812 November 1969) was a Chinese revolutionary and politician. He was the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress from 1954 to 1959, first-ranking Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communis ...

and Deng Xiaoping

Deng Xiaoping also Romanization of Chinese, romanised as Teng Hsiao-p'ing; born Xiansheng (). (22 August 190419 February 1997) was a Chinese statesman, revolutionary, and political theorist who served as the paramount leader of the People's R ...

decided to send in 'work teams'—effectively 'ideological guidance' squads of cadres—to the city's schools and ''People's Daily'' to restore some semblance of order and re-establish party control.[

The work teams had a poor understanding of student sentiment. Unlike the political movement of the 1950s that squarely targeted intellectuals, the new movement was focused on established party cadres, many of whom were part of the work teams. As a result, the work teams came under increasing suspicion as thwarting revolutionary fervor.][ Party leadership subsequently became divided over whether or not work teams should continue. Liu Shaoqi insisted on continuing work-team involvement and suppressing the movement's most radical elements, fearing that the movement would spin out of control.][

]

''Bombard the Headquarters'' (July)

In July, Mao, in Wuhan, crossed the Yangtze River, showing his vigor. He then returned from Wuhan to Beijing and criticized party leadership for its handling of the work-teams issue. Mao accused the work teams of undermining the student movement, calling for their full withdrawal on 24 July. Several days later a rally was held at the Great Hall of the People to announce the decision and reveal the tone of the movement to teachers and students. At the rally, Party leaders encouraged the masses to 'not be afraid' and take charge of the movement, free of Party interference.[

The work-teams issue marked a decisive defeat for Liu; it also signaled that disagreement over how to handle the CR's unfolding events would irreversibly split Mao from the party leadership. On 1 August, the Eleventh Plenum of the 8th Central Committee was convened to advance Mao's radical agenda. At the plenum, Mao showed disdain for Liu, repeatedly interrupting him as he delivered his opening day speech.][

On 28 July, Red Guard representatives wrote to Mao, calling for rebellion and upheaval to safeguard the revolution. Mao then responded to the letters by writing his own big-character poster entitled '' Bombard the Headquarters'', rallying people to target the "command centre (i.e., Headquarters) of counterrevolution." Mao wrote that despite having undergone a communist revolution, a "bourgeois" elite was still thriving in "positions of authority" in the government and Party.] Along with the top leadership losing power the entire national Party bureaucracy was purged. The extensive Organization Department, in charge of party personnel, virtually ceased to exist. The top officials in the Propaganda Department were sacked, with many of its functions folded into the CRG.

Along with the top leadership losing power the entire national Party bureaucracy was purged. The extensive Organization Department, in charge of party personnel, virtually ceased to exist. The top officials in the Propaganda Department were sacked, with many of its functions folded into the CRG.[

]

Red August and the Sixteen Points

'' Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung'' led the Red Guards to commit to their objective as China's future.[ By December 1967, 350 million copies had been printed.]

Although the bourgeoisie has been overthrown, it is still trying to use the old ideas, culture, customs and habits of the exploiting classes to corrupt the masses, capture their minds and endeavour to stage a comeback. The proletariat must do the exact opposite: it must meet head-on every challenge of the bourgeoisie ... to change the mental outlook of the whole of society. At present, our objective is to struggle against and overthrow those persons in authority who are taking the capitalist road, to criticize and repudiate the reactionary bourgeois academic "authorities" and the ideology of the bourgeoisie and all other exploiting classes and to transform education, literature and art and all other parts of the superstructure not in correspondence with the socialist economic base, so as to facilitate the consolidation and development of the socialist system.

The implications of the Sixteen Points were far-reaching. It elevated what was previously a student movement to a nationwide mass campaign that would galvanize workers, farmers, soldiers and lower-level party functionaries to rise, challenge authority, and re-shape the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

of society.

On 18 August in Beijing, over a million Red Guards from across the country gathered in and around Tiananmen Square

Tiananmen Square or Tian'anmen Square () is a city square in the city center of Beijing, China, named after the Tiananmen ("''Gate of Heavenly Peace''") located to its north, which separates it from the Forbidden City. The square contains th ...

for an audience with the chairman.[ Mao mingled with Red Guards and encouraged them, donning a Red Guard armband. Lin also took centre stage, denouncing perceived enemies in society that were impeding the "progress of the revolution".][ Subsequently, violence escalated in Beijing and quickly spread.][

The campaign included incidents of torture, murder, and public humiliation. Many people who were indicted as counter-revolutionaries died by suicide. During Red August, 1,772 people were murdered in Beijing; many of the victims were teachers who were attacked or killed by their own students.][ Peng Dehuai was brought to Beijing to be publicly ridiculed.

]

Destruction of the Four Olds (August–November)

Between August and November 1966, eight mass rallies were held, drawing in 12 million people, most of whom were Red Guards.

Between August and November 1966, eight mass rallies were held, drawing in 12 million people, most of whom were Red Guards.[ To aid Red Guards in traveling, the Great Exchange of Revolutionary Experience program, which lasted from September 1966 to early 1967, gave them free food and lodging throughout the country.][

At the rallies, Lin called for the destruction of the Four Olds; namely, old customs, culture, habits, and ideas.]Temple of Confucius

A temple of Confucius or Confucian temple is a temple for the veneration of Confucius and the sages and philosophers of Confucianism in Chinese folk religion and other East Asian religions. They were formerly the site of the administration of ...

in Qufu

Qufu ( ; zh, c=曲阜) is a county-level city in southwestern Shandong province, East China. It is located about south of the provincial capital Jinan and northeast of the prefectural seat at Jining. Qufu has an area of 815 square kilometers, ...

,[ and other historically significant tombs and artifacts.]Buddhism

Buddhism, also known as Buddhadharma and Dharmavinaya, is an Indian religion and List of philosophies, philosophical tradition based on Pre-sectarian Buddhism, teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or ...

as superstition, and religion was looked upon as a means of hostile foreign infiltration, as well as an instrument of the ruling class.cemetery of Confucius

The Cemetery of Confucius () is a cemetery of the Kong clan (the descendants of Confucius) in Confucius' hometown Qufu in eastern Shandong province. Confucius himself and some of his disciples are buried there, as well as many thousands of his ...

was attacked by Red Guards in November 1966.Yongle Emperor

The Yongle Emperor (2 May 1360 – 12 August 1424), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Chengzu of Ming, personal name Zhu Di, was the third List of emperors of the Ming dynasty, emperor of the Ming dynasty, reigning from 1402 to 142 ...

was originally carved in stone, and was destroyed in the Cultural Revolution. A metal replica is in its place.

File:Huineng.jpg, The remains of the 8th century Buddhist monk Huineng

Dajian Huineng or Hui-nengThe Sutra of Hui-neng, Grand Master of Zen, with Hui-neng's Commentary on the Diamond Sutra, translated by Thomas Cleary, Shambhala Publications, 1998 (; February 27, 638 – August 28, 713), also commonly known as the ...

were attacked during the Cultural Revolution.

File:SuzhouGardenFrieze.jpg, A frieze damaged during the Cultural Revolution, originally from a garden house of a rich imperial official in Suzhou.

In September 1966, central Party authorities under Zhou Enlai issued the ''Instructions on Grasping Revolution, Promoting Production'', which directed that "one must grasp revolution on one hand and promote production on the other hand.

Central Work Conference (October)

In October 1966, Mao convened a Central Work Conference, mostly to enlist party leaders who had not yet adopted the latest ideology. Liu and Deng were prosecuted and begrudgingly offered self-criticism.[ After the conference, Liu, once a powerful moderate pundit, was placed under house arrest, then sent to a detention camp, where he was denied medical treatment and died in 1969. Deng was sent away for a period of re-education three times and was eventually sent to work in an engine factory in ]Jiangxi

; Gan: )

, translit_lang1_type2 =

, translit_lang1_info2 =

, translit_lang1_type3 =

, translit_lang1_info3 =

, image_map = Jiangxi in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_caption = Location ...

. Rebellion by party cadres accelerated after the conference.

End of the year

On 5 October, the Central Military Commission and the PLA's Department of General Political Tasks directed military academies to dismiss their classes to allow cadets to become more involved in the Cultural Revolution.Macau

Macau or Macao is a special administrative regions of China, special administrative region of the People's Republic of China (PRC). With a population of about people and a land area of , it is the most List of countries and dependencies by p ...

, rioting broke out during the 12-3 incident.Taipa

Taipa ( zh, t=氹仔, ; , ) is an area in Macau, connected to Coloane through the area known as Cotai, which is largely built from reclaimed land. Located on the northern half of the island, Taipa's population is mostly suburban. Administrativ ...

.melee

A melee ( or ) is a confused hand-to-hand combat, hand-to-hand fight among several people. The English term ''melee'' originated circa 1648 from the French word ' (), derived from the Old French ''mesler'', from which '':wikt:medley, medley'' and ...

. On December 3, 1966, two days of rioting occurred in which hundreds were injured and six to eight were killed, leading to a total clampdown by the Portuguese government. The event set in motion Portugal's de facto abdication of control over Macau, putting Macau on the path to eventual absorption by China.

1967: Seizure of power

Mass organizations coalesced into two factions, the radicals who backed Mao's purge of the Communist party, and the conservatives who backed the moderate party establishment. The "support the left" policy was established in January 1967.Wang Hongwen

Wang Hongwen (December 1935 – 3 August 1992) was a Chinese labour activist and politician who was the youngest member of the Gang of Four. He rose to prominence during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), after organizing the Shanghai Peo ...

organized a far-reaching revolutionary coalition, one that displaced existing Red Guard groups. On 3 January 1967, with support from CRG heavyweights Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, the group of firebrand activists overthrew the Shanghai municipal government under Chen Pixian in what became known as the January Storm, and formed in its place the Shanghai People's Commune

The January Storm, formally known as the January Revolution, was a ''coup d'état'' in Shanghai that occurred between 5 January and 23 February 1967, during the Cultural Revolution. The coup, precipitated by the ''Sixteen Articles'' and unexpe ...

.[ Mao then expressed his approval.]Pan Fusheng

Pan Fusheng (; December 1908 – April 1980) was a Chinese Communist Party, Chinese Communist revolutionary and politician. He was the first Chinese Communist Party Committee Secretary, party secretary of the short-lived Pingyuan Province of t ...

seized power from the party organization under his own leadership. Some leaders even wrote to the CRG asking to be overthrown.[

In Beijing, Jiang Qing and Zhang Chunqiao targeted Vice-Premier ]Tao Zhu

Tao Zhu (; 16 January 1908 – 30 November 1969) was a member of the Politburo Standing Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

Biography

Tao was born in Qiyang, Qiyang County, Hunan, on 16 January 1908.

He was imprisoned in Nanjing by the K ...

. The power-seizure movement was appearing in the military as well. In February, prominent generals Ye Jianying and Chen Yi, as well as Vice-Premier Tan Zhenlin, vocally asserted their opposition to the more extreme aspects of the movement, with some party elders insinuating that the CRG's real motives were to remove the revolutionary old guard. Mao, initially ambivalent, took to the Politburo floor on 18 February to denounce the opposition directly, endorsing the radicals' activities. This resistance was branded the February Countercurrent[—effectively silencing critics within the party.][

Although in early 1967 popular insurgencies were limited outside of the biggest cities, local governments began collapsing all across China.]Zhang Chunqiao

Zhang Chunqiao (; 1 February 1917 – 21 April 2005) was a Chinese political theorist, writer, and politician. He came to the national spotlight during the late stages of the Cultural Revolution, and was a member of the ultra-Maoist group dub ...

admitted that the most crucial factor in the Cultural Revolution was not the Red Guards or the CRG or the "rebel worker" organisations, but the PLA. When the PLA local garrison supported Mao's radicals, they were able to take over the local government successfully, but if they were not cooperative, the takeovers were unsuccessful.Chongqing

ChongqingPostal Romanization, Previously romanized as Chungking ();. is a direct-administered municipality in Southwestern China. Chongqing is one of the four direct-administered municipalities under the State Council of the People's Republi ...

, factional violence was particularly pronounced.weapon of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a biological, chemical, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill or significantly harm many people or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natural structures ( ...

, were seized during conflicts, but not directly used. Citizens wrote letters to the Zhongnanhai

Zhongnanhai () is a compound that houses the offices of and serves as a residence for the leadership of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the State Council of the People's Republic of China, State Council. It was a former imperial gard ...

residence of government leaders, warning of attacks on facilities that stored pathogenic bacteria

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and many are Probiotic, beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The nu ...

, poisonous plant samples, radioactive substances, poison gas, toxicants, and other dangerous substances. In Changchun

Changchun is the capital and largest city of Jilin, Jilin Province, China, on the Songliao Plain. Changchun is administered as a , comprising seven districts, one county and three county-level cities. At the 2020 census of China, Changchun ha ...

, rebels working in geological institutes developed and tested a dirty bomb, a crude radiological weapon, testing two "radioactive self-defense bombs" and two "radioactive self-defense mines" on 6 and 11 August.Xiamen

Xiamen,), also known as Amoy ( ; from the Zhangzhou Hokkien pronunciation, zh, c=, s=, t=, p=, poj=Ē͘-mûi, historically romanized as Amoy, is a sub-provincial city in southeastern Fujian, People's Republic of China, beside the Taiwan Stra ...

, and Changchun

Changchun is the capital and largest city of Jilin, Jilin Province, China, on the Songliao Plain. Changchun is administered as a , comprising seven districts, one county and three county-level cities. At the 2020 census of China, Changchun ha ...

, tanks, armored vehicles and even warships were deployed in combat.hygiene

Hygiene is a set of practices performed to preserve health.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), "Hygiene refers to conditions and practices that help to maintain health and prevent the spread of diseases." Personal hygiene refer ...

, preventive healthcare

Preventive healthcare, or prophylaxis, is the application of healthcare measures to prevent diseases.Hugh R. Leavell and E. Gurney Clark as "the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting physical and mental health a ...

, and family planning

Family planning is the consideration of the number of children a person wishes to have, including the choice to have no children, and the age at which they wish to have them. Things that may play a role on family planning decisions include marit ...

and treated common illnesses.

1968: Purges

In May 1968, Mao launched a massive political purge. Many people were sent to the countryside to work in reeducation camps. Generally, the campaign targeted rebels from the CR's earlier, more populist, phase.

Mao meets with Red Guard leaders (July)

As the Red Guard movement had waned over the preceding year, violence by the remaining Red Guards increased on some Beijing campuses. Violence was particularly pronounced at Tsinghua University

Tsinghua University (THU) is a public university in Haidian, Beijing, China. It is affiliated with and funded by the Ministry of Education of China. The university is part of Project 211, Project 985, and the Double First-Class Constructio ...

, where a few thousand hardliners of two factions continued to fight. At Mao's initiative, on 27 July 1968, tens of thousands of workers entered the Tsinghua campus shouting slogans in opposition to the violence. Red Guards attacked the workers, who remained peaceful. Ultimately, the workers disarmed the students and occupied the campus.

Mao's cult of personality and "mango fever" (August)

In the spring of 1968, a massive campaign aimed at enhancing Mao's reputation began. On 4 August, Mao was presented with mangoes by the Pakistani foreign minister Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada, in an apparent diplomatic gesture.Tsinghua University

Tsinghua University (THU) is a public university in Haidian, Beijing, China. It is affiliated with and funded by the Ministry of Education of China. The university is part of Project 211, Project 985, and the Double First-Class Constructio ...

on 5 August, who were stationed there to quiet strife among Red Guard factions.Chengdu

Chengdu; Sichuanese dialects, Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: ; Chinese postal romanization, previously Romanization of Chinese, romanized as Chengtu. is the capital city of the Chinese province of Sichuan. With a ...

. Badges and wall posters featuring the mangoes and Mao were produced in the millions.

Down to the Countryside Movement (December)

In December 1968, Mao began the Down to the Countryside Movement. During this movement, which lasted for the following decade, young bourgeoisie living in cities were ordered to go to the countryside to experience working life. The term "young intellectuals" was used to refer to recent college graduates. In the late 1970s, these students returned to their home cities. Many students who were previously Red Guard supported the movement and Mao's vision. This movement was thus in part a means of moving Red Guards from the cities to the countryside, where they would cause less social disruption. It also served to spread revolutionary ideology geographically.

1969–1971: Lin Biao

The 9th National Congress was held in April 1969. It served as a means to "revitalize" the party with fresh thinking—as well as new cadres, after much of the old guard had been destroyed in the struggles of the preceding years.[ The party framework established two decades earlier broke down almost entirely: rather than through an election by party members, delegates for this Congress were effectively selected by Revolutionary Committees.][ Representation of the military increased by a large margin from the previous Congress, reflected in the election of more PLA members to the new Central Committee—over 28%. Many officers now elevated to senior positions were loyal to PLA Marshal Lin Biao, which would open a new rift between the military and civilian leadership.][

Reflecting this, Lin was officially elevated to become the Party's preeminent figure outside of Mao, with his name written into the party constitution as his "closest comrade-in-arms" and "universally recognized successor".][ At the time, no other Communist parties or governments anywhere in the world had adopted the practice of enshrining a successor to the current leader into their constitutions. Lin delivered the keynote address at the Congress: a document drafted by hardliner leftists Yao Wenyuan and Zhang Chunqiao under Mao's guidance.][

The report was heavily critical of Liu Shaoqi and other "counter-revolutionaries" and drew extensively from quotations in the ''Little Red Book''. The Congress solidified the central role of Maoism within the party, re-introducing Maoism as the official guiding ideology in the party constitution. The Congress elected a new Politburo with Mao, Lin, Chen, Zhou Enlai and Kang as the members of the new Politburo Standing Committee.][

Lin, Chen, and Kang were all beneficiaries of the Cultural Revolution. Zhou, who was demoted in rank, voiced his unequivocal support for Lin at the Congress.][ Mao restored the function of some formal party institutions, such as the operations of the Politburo, which ceased functioning between 1966 and 1968 because the CCRG held de facto control.][

In early 1970, the nationwide "]One Strike-Three Anti Campaign The One Strike-Three Anti campaign () was a national campaign launched by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in early 1970 during the Cultural Revolution. The campaign aimed to consolidate central power by targeting "counte ...

" was launched by Mao and the Communist Party Central, aiming to consolidate the new organs of power by targeting counterrevolutionary thoughts and actions.

PLA encroachment

Mao's efforts at re-organizing party and state institutions generated mixed results. The situation in some of the provinces remained volatile, even as the political situation in Beijing stabilized. Factional struggles, many violent, continued at a local level despite the declaration that the 9th National Congress marked a temporary victory for the CR.

Mao's efforts at re-organizing party and state institutions generated mixed results. The situation in some of the provinces remained volatile, even as the political situation in Beijing stabilized. Factional struggles, many violent, continued at a local level despite the declaration that the 9th National Congress marked a temporary victory for the CR.[ Furthermore, despite Mao's efforts to put on a show of unity at the Congress, the factional divide between Lin's PLA camp and the Jiang-led radical camp was intensifying. Indeed, a personal dislike of Jiang drew many civilian leaders, including Chen, closer to Lin.]Ussuri River

The Ussuri ( ; ) or Wusuli ( ) is a river that runs through Khabarovsk and Primorsky Krais, Russia and the southeast region of Northeast China in the province of Heilongjiang. It rises in the Sikhote-Alin mountain range, flowing north and for ...

in March 1969 as Chinese leaders prepared for all-out war.[ In June 1969, the PLA's enforcement of political discipline and suppression of the factions that had emerged during the Cultural Revolution became intertwined with the central Party's efforts to accelerate Third Front. Those who did not return to work would be viewed as engaging in 'schismatic activity' which risked undermining preparations to defend China from potential invasion.][ Some evidence suggests that Mao was pushed to seek closer relations with the US as a means to avoid PLA dominance that would result from a military confrontation with the Soviet Union.][ During his later meeting with ]Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

in 1972, Mao hinted that Lin had opposed better relations with the U.S.[

]

Restoration of State Chairman position

After Lin was confirmed as Mao's successor, his supporters focused on the restoration of the position of State Chairman, which had been abolished by Mao after Liu's purge. They hoped that by allowing Lin to ease into a constitutionally sanctioned role, whether Chairman or vice-chairman, Lin's succession would be institutionalized. The consensus within the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

was that Mao should assume the office with Lin as vice-chairman; but perhaps wary of Lin's ambitions or for other unknown reasons, Mao voiced his explicit opposition.[

Factional rivalries intensified at the Second Plenum of the Ninth Congress in Lushan held in late August 1970. Chen, now aligned with the PLA faction loyal to Lin, galvanized support for the restoration of the office of President of China, despite Mao's wishes. Moreover, Chen launched an assault on Zhang, a staunch Maoist who embodied the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, over the evaluation of Mao's legacy.][

The attacks on Zhang found favour with many Plenum attendees and may have been construed by Mao as an indirect attack on the CR. Mao confronted Chen openly, denouncing him as a "false Marxist",][ and removed him from the Politburo Standing Committee. In addition to the purge of Chen, Mao asked Lin's principal generals to write self-criticisms on their political positions as a warning to Lin. Mao also inducted several of his supporters to the Central Military Commission and placed loyalists in leadership roles of the ]Beijing Military Region

The Beijing Military Region was one of seven military regions for the Chinese People's Liberation Army. From the mid-1980s to 2017, it had administration of all military affairs within Beijing city, Tianjin city, Hebei province, Shanxi province, ...

.[

]

Project 571

By 1971, the diverging interests of the civilian and military leaders was apparent. Mao was troubled by the PLA's newfound prominence, and the purge of Chen marked the beginning of a gradual scaling-down of the PLA's political involvement.[ According to official sources, sensing the reduction of Lin's power base and his declining health, Lin's supporters plotted to use the military power still at their disposal to oust Mao in a coup.][

Lin's son Lin Liguo, along with other high-ranking military conspirators, formed a coup apparatus in Shanghai and dubbed the plan to oust Mao ''Outline for Project 571''in the original Mandarin, the phrase sounds similar to the term for 'military uprising'. It is disputed whether Lin Biao was directly involved in this process. While official sources maintain that Lin did plan and execute the coup attempt, scholars such as Jin Qiu portray Lin as passive, cajoled by elements among his family and supporters. Qiu contests that Lin Biao was ever personally involved in drafting the ''Outline'', with evidence suggesting that Lin Liguo was directly responsible for the draft.]

Lin's flight and plane crash

According to the official narrative, on 13 September Lin Biao, his wife Ye Qun, Lin Liguo, and members of his staff attempted to flee to the USSR ostensibly to seek political asylum. En route, Lin's plane crashed in Mongolia, killing all on board. The plane apparently ran out of fuel. A Soviet investigative team was not able to determine the cause of the crash but hypothesized that the pilot was flying low to evade radar and misjudged the plane's altitude.

The account was questioned by those who raised doubts over Lin's choice of the USSR as a destination, the plane's route, the identity of the passengers, and whether or not a coup was actually taking place.

According to the official narrative, on 13 September Lin Biao, his wife Ye Qun, Lin Liguo, and members of his staff attempted to flee to the USSR ostensibly to seek political asylum. En route, Lin's plane crashed in Mongolia, killing all on board. The plane apparently ran out of fuel. A Soviet investigative team was not able to determine the cause of the crash but hypothesized that the pilot was flying low to evade radar and misjudged the plane's altitude.

The account was questioned by those who raised doubts over Lin's choice of the USSR as a destination, the plane's route, the identity of the passengers, and whether or not a coup was actually taking place.[

On 13 September, the Politburo met in an emergency session to discuss Lin. His death was confirmed in Beijing only on 30 September, which led to the cancellation of the National Day celebration events the following day. The Central Committee did not release news of Lin's death to the public until two months later. Many Lin supporters sought refuge in Hong Kong. Those who remained on the mainland were purged.][

The event caught the party leadership off guard: the concept that Lin could betray Mao de-legitimized a vast body of Cultural Revolution political rhetoric and by extension, Mao's absolute authority. For several months following the incident, the party information apparatus struggled to find a "correct way" to frame the incident for public consumption, but as the details came to light, the majority of the Chinese public felt disillusioned and realised they had been manipulated for political purposes.][

]

1972–1976: The Gang of Four

Mao became depressed and reclusive after the Lin incident. Sensing a sudden loss of direction, Mao reached out to old comrades whom he had denounced in the past. Meanwhile, in September 1972, Mao transferred a 38-year-old cadre from Shanghai, Wang Hongwen, to Beijing and made him Party vice-chairman. Wang, a former factory worker from a peasant background,[ was seemingly getting groomed for succession.][

Jiang's position strengthened after Lin's flight. She held tremendous influence with the radical camp. With Mao's health on the decline, Jiang's political ambitions began to emerge. She allied herself with Wang and propaganda specialists Zhang Chunqiao and Yao Wenyuan, forming a political clique later pejoratively dubbed as the ]Gang of Four

The Gang of Four () was a Maoist political faction composed of four Chinese Communist Party (CCP) officials. They came to prominence during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) and were later charged with a series of treasonous crimes due to th ...

.[ China's economy had fallen into disarray, which led to the rehabilitation of purged lower-level officials. The party's core became heavily dominated by Cultural Revolution beneficiaries and radicals, whose focus remained ideological purity over economic productivity. The economy remained mostly Zhou's domain, one of the few remaining moderates. Zhou attempted to restore the economy, but was resented by the Gang of Four, who identified him as their primary political succession threat.

In late 1973, to weaken Zhou's political position and to distance themselves from Lin's apparent betrayal, the Criticize Lin, Criticize Confucius campaign began under Jiang's leadership.][ Its stated goals were to purge China of New Confucianist thinking and denounce Lin's actions as traitorous and regressive.][

]

Deng Xiaoping's rehabilitation (1975)

Deng Xiaoping returned to the political scene, assuming the post of Vice-Premier in March 1973, in the first of a series of Mao-approved promotions. After Zhou withdrew from active politics in January 1975, Deng was effectively put in charge of the government, party, and military, then adding the additional titles of PLA General Chief of Staff, Vice Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party, and vice-chairman of the Central Military Commission.[

Mao wanted to use Deng as a counterweight to the military faction in government to suppress former Lin loyalists. In addition, Mao had also lost confidence in the Gang of Four and saw Deng as the alternative. Leaving the country in grinding poverty would damage the positive legacy of the CR, which Mao worked hard to protect. Deng's return set the scene for a protracted factional struggle between the radical Gang of Four and moderates led by Zhou and Deng.

At the time, Jiang and associates held effective control of mass media and the party's propaganda network, while Zhou and Deng held control of most government organs. On some decisions, Mao sought to mitigate the Gang's influence, but on others, he acquiesced to their demands. The Gang of Four's political and media control did not prevent Deng from enacting his economic policies. Deng emphatically opposed Party factionalism, and his policies aimed to promote unity to restore economic productivity. Much like the post-Great Leap restructuring led by Liu Shaoqi, Deng streamlined the railway system, steel production, etc. By late 1975, however, Mao saw that Deng's economic restructuring might negate the CR's legacy and launched the Counterattack the Right-Deviationist Reversal-of-Verdicts Trend, a campaign to oppose "rehabilitating the case for the rightists", alluding to Deng as the country's foremost "rightist". Mao directed Deng to write self-criticisms in November 1975, a move lauded by the Gang of Four.][

]

Death of Zhou Enlai

On 8 January 1976, Zhou Enlai died of bladder cancer. On 15 January, Deng delivered Zhou's eulogy in a funeral attended by all of China's most senior leaders with the notable absence of Mao, who had grown increasingly critical of Zhou.Hua Guofeng

Hua Guofeng (born Su Zhu (); 16 February 1921 – 20 August 2008) was a Chinese politician who served as chairman of the Chinese Communist Party and the 2nd premier of China. The designated successor of Mao Zedong, Hua held the top offices of t ...

instead of a member of the Gang of Four or Deng to become Premier.

The Gang of Four grew apprehensive that spontaneous, large-scale popular support for Zhou could turn the political tide against them. They acted through the media to impose restrictions on public displays of mourning for Zhou. Years of resentment over the CR, the public persecution of Deng—seen as Zhou's ally—and the prohibition against public mourning led to a rise in popular discontent against Mao and the Gang of Four. Official attempts to enforce the mourning restrictions included removing public memorials and tearing down posters commemorating Zhou's achievements. On 25 March 1976, Shanghai's '' Wen Hui Bao'' published an article calling Zhou "the capitalist roader inside the Party howanted to help the unrepentant capitalist roader engregain his power." These propaganda efforts at smearing Zhou's image, however, only strengthened public attachment to Zhou's memory.[

]

Tiananmen incident

On 4 April 1976, on the eve of China's annual Qingming Festival

The Qingming Festival or Ching Ming Festival, also known as Tomb-Sweeping Day in English (sometimes also called Chinese Memorial Day, Ancestors' Day, the Clear Brightness Festival, or the Pure Brightness Festival), is a traditional Chines ...

, a traditional day of mourning, thousands of people gathered around the Monument to the People's Heroes

The Monument to the People's Heroes () is a ten-story obelisk that was erected as a national monument of China to the Martyr (China), martyrs of revolutionary struggle during the 19th and 20th centuries. It is located in the southern part of Tiana ...

in Tiananmen Square to commemorate Zhou. They honored Zhou by laying wreaths, banners, poems, placards, and flowers at the foot of the Monument.[ The most apparent purpose of this memorial was to eulogize Zhou, but the Gang of Four were also attacked for their actions against the Premier. A small number of slogans left at Tiananmen even attacked Mao and his Cultural Revolution.][

Up to two million people may have visited Tiananmen Square on 4 April. All levels of society, from the most impoverished peasants to high-ranking PLA officers and the children of high-ranking cadres, were represented in the activities. Those who participated were motivated by a mixture of anger over Zhou's treatment, revolt against the Cultural Revolution and apprehension for China's future. The event did not appear to have coordinated leadership.][

The Central Committee, under the leadership of Jiang Qing, labelled the event 'counter-revolutionary' and cleared the square of memorial items shortly after midnight on April 6. Attempts to suppress the mourners led to a riot. Police cars were set on fire, and a crowd of over 100,000 people forced its way into several government buildings surrounding the square. Many of those arrested were later sentenced to prison. Similar incidents occurred in other major cities. Jiang and her allies attacked Deng as the incident's 'mastermind', and issued reports on official media to that effect. Deng was formally stripped of all positions inside and outside the Party on 7 April. This marked Deng's second purge.][

]

Death of Mao Zedong and the Gang of Four's downfall

On 9 September 1976, Mao Zedong died. To Mao's supporters, his death symbolized the loss of China's revolutionary foundation. His death was announced on 9 September. The nation descended into grief and mourning, with people weeping in the streets and public institutions closing for over a week. Hua Guofeng chaired the Funeral Committee and delivered the memorial speech.

Shortly before dying, Mao had allegedly written the message " With you in charge, I'm at ease," to Hua. Hua used this message to substantiate his position as successor. Hua had been widely considered to be lacking in political skill and ambitions, and seemingly posed no serious threat to the Gang of Four in the race for succession. However, the Gang's radical ideas also clashed with influential elders and many Party reformers. With army backing and the support of Marshal Ye Jianying, Director of Central Office Wang Dongxing, Vice Premier Li Xiannian

Li Xiannian (; 23 June 1909 – 21 June 1992) was a Chinese Chinese Communist Party, Communist military and political leader, president of China from 1983 to 1988 under paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and then chairman of the Chinese People's Politi ...

and party elder Chen Yun

Chen Yun (13 June 1905 – 10 April 1995) was a statesman of the Chinese Communist Party and the People's Republic of China. He was one of the most prominent leaders during the periods when China was governed by Mao Zedong and later by Deng Xia ...

, on 6 October, the Central Security Bureau's Special Unit 8341 had all members of the Gang of Four arrested in a bloodless coup.

After Mao's death, people characterized as 'beating-smashing-looting elements', who were seen as having disturbed the social order during the CR, were purged or punished. "Beating-smashing-looting elements" had typically been aligned with rebel factions.

Aftermath

Transitional period

Although Hua denounced the Gang of Four in 1976, he continued to invoke Mao's name to justify Mao-era policies. Hua spearheaded what became known as the Two Whatevers

The "Two Whatevers" ( zh, s=两个凡是, p=Liǎng gè fán shì) refers to the statement that "We will resolutely uphold whatever policy decisions Chairman Mao made, and unswervingly follow whatever instructions Chairman Mao gave" ().

This stat ...

.Li Xiannian

Li Xiannian (; 23 June 1909 – 21 June 1992) was a Chinese Chinese Communist Party, Communist military and political leader, president of China from 1983 to 1988 under paramount leader Deng Xiaoping and then chairman of the Chinese People's Politi ...

and Wang Dongxing as new members of the Politburo Standing Committee.

Repudiation and reform under Deng

Deng Xiaoping first proposed what he called ''Boluan Fanzheng'' in September 1977 in order to correct the mistakes of the Cultural Revolution. In May 1978, Deng seized the opportunity to elevate his protégé

Deng Xiaoping first proposed what he called ''Boluan Fanzheng'' in September 1977 in order to correct the mistakes of the Cultural Revolution. In May 1978, Deng seized the opportunity to elevate his protégé Hu Yaobang

Hu Yaobang (20 November 1915 – 15 April 1989) was a Chinese politician who was a high-ranking official of the People's Republic of China. He held the Leader of the Chinese Communist Party, top office of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) from ...

to power. Hu published an article in the ''Guangming Daily

The ''Guangming Daily'', also known as the ''Enlightenment Daily'', is a national Chinese-language daily newspaper published in the People's Republic of China. It was established in 1949 as the official paper of the China Democratic League. S ...

'', making clever use of Mao's quotations, while lauding Deng's ideas. Following this article, Hua began to shift his tone in support of Deng. On 1 July, Deng publicized Mao's self-criticism report of 1962 regarding the failure of the Great Leap Forward. As his power base expanded, in September Deng began openly attacking Hua Guofeng's "Two Whatevers".humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

and universal values, while opposing the ideology of Cultural Revolution.

On 18 December 1978, Third Plenum of the 11th Central Committee was held. Deng called for "a liberation of thoughts" and urged the party to "seek truth from facts

"Seek truth from facts" is a historically established idiomatic expression ('' chengyu'') in the Chinese language that first appeared in the '' Book of Han''. Originally, it described an attitude toward study and research. Popularized by Chinese ...

" and abandon ideological dogma. The Plenum officially marked the beginning of the economic reform era. Hua Guofeng engaged in self-criticism and called his "Two Whatevers" a mistake. At the Plenum, the Party reversed its verdict on the Tiananmen Incident. Former Chinese president Liu Shaoqi was given a belated state funeral. Peng Dehuai, who was persecuted to death during the Cultural Revolution was rehabilitated in 1978.

At the Fifth Plenum held in 1980, Peng Zhen, He Long and other leaders who had been purged during the Cultural Revolution were rehabilitated. Hu Yaobang became head of the party secretariat as its secretary-general

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

. In September, Hua Guofeng resigned, and Zhao Ziyang, another Deng ally, was named premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of govern ...

. Hua remained on the Central Military Commission, but formal power was transferred to a new generation of pragmatic reformers, who reversed Cultural Revolution policies to a large extent. Within a few years, Deng and Hu helped rehabilitate over 3 million "unjust, false, erroneous" cases. In particular, the trial of the Gang of Four took place in Beijing from 1980 to 1981, and the court stated that 729,511 people had been persecuted by the Gang, of whom 34,800 were said to have died.

In 1981, the Chinese Communist Party passed a resolution and declared that the Cultural Revolution was "responsible for the most severe setback and the heaviest losses suffered by the Party, the country, and the people since the founding of the People's Republic."

Atrocities

Death toll

Fatality estimates vary across different sources, ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions, or even tens of millions.

Fatality estimates vary across different sources, ranging from hundreds of thousands to millions, or even tens of millions.1975 Banqiao Dam failure

In August 1975, the Banqiao Dam and 61 others throughout Henan, China, collapsed following the landfall of Typhoon Nina (1975), Typhoon Nina. The dam collapse created the List of natural disasters by death toll#Floods, third-deadliest flood in hi ...

, also caused many deaths.

Literature review

A literature review is an overview of previously published works on a particular topic. The term can refer to a full scholarly paper or a section of a scholarly work such as books or articles. Either way, a literature review provides the rese ...

s of the overall death toll due to the Cultural Revolution usually include the following:

Massacres

Massacres took place across China, including in

Massacres took place across China, including in Guangxi

Guangxi,; officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam (Hà Giang Province, Hà Giang, Cao Bằn ...

, Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

, Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

, Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

, Hunan

Hunan is an inland Provinces of China, province in Central China. Located in the middle reaches of the Yangtze watershed, it borders the Administrative divisions of China, province-level divisions of Hubei to the north, Jiangxi to the east, Gu ...

, Ruijin, and Qinghai

Qinghai is an inland Provinces of China, province in Northwestern China. It is the largest provinces of China, province of China (excluding autonomous regions) by area and has the third smallest population. Its capital and largest city is Xin ...

, as well as Red August in Beijing.Guangxi

Guangxi,; officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam (Hà Giang Province, Hà Giang, Cao Bằn ...

and Guangdong

) means "wide" or "vast", and has been associated with the region since the creation of Guang Prefecture in AD 226. The name "''Guang''" ultimately came from Guangxin ( zh, labels=no, first=t, t= , s=广信), an outpost established in Han dynasty ...

were among the most serious. In Guangxi, the official annals of at least 43 counties have records of massacres, with 15 of them reporting a death toll of over 1,000, while in Guangdong at least 28 county annals record massacres, with 6 of them reporting a death toll of over 1,000.Dao County

Dao County () is a county in Hunan Province, China. It is under the administration of Yongzhou prefecture-level City.

Located on the southern margin of the province, it is adjacent to the northeastern border of Guangxi. The county borders to the ...

, Hunan, a total of 7,696 people were killed from 13 August to 17 October 1967, in addition to 1,397 forced to commit suicide, and 2,146 becoming permanently disabled.

In the Guangxi Massacre, the official record shows an estimated death toll from 100,000 to 150,000 as well as cannibalism

Cannibalism is the act of consuming another individual of the same species as food. Cannibalism is a common ecological interaction in the animal kingdom and has been recorded in more than 1,500 species. Human cannibalism is also well document ...

primarily between 1967 and 1968 in Guangxi,Yunnan

Yunnan; is an inland Provinces of China, province in Southwestern China. The province spans approximately and has a population of 47.2 million (as of 2020). The capital of the province is Kunming. The province borders the Chinese provinces ...

around the town of Shadian, targeting Hui people

The Hui people are an East Asian ethnoreligious group predominantly composed of Islam in China, Chinese-speaking adherents of Islam. They are distributed throughout China, mainly in the Northwest China, northwestern provinces and in the Zhongy ...

, resulting in the deaths of more than 1,600 civilians, including 300 children, and the destruction of 4,400 homes.

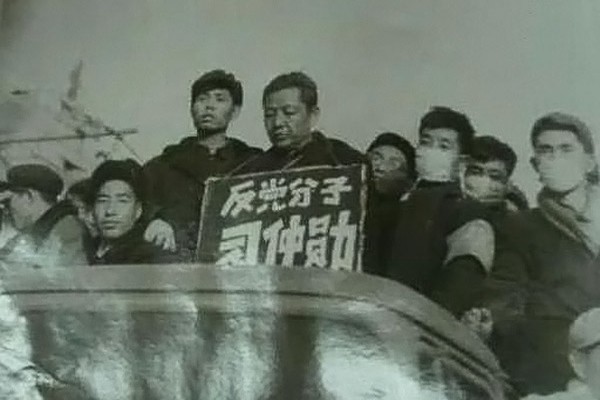

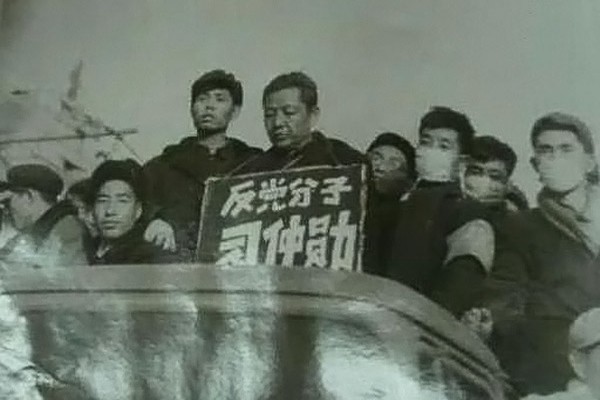

Violent struggles, struggle sessions, and purges

''Violent struggles'' were factional conflicts (mostly among Red Guards and "rebel groups") that began in Shanghai and then spread to other areas in 1967. They brought the country to a state of civil war.Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

, and in Xuzhou

Xuzhou ( zh, s=徐州), also known as Pengcheng () in ancient times, is a major city in northwestern Jiangsu province, China. The city, with a recorded population of 9,083,790 at the 2020 Chinese census, 2020 census (3,135,660 of which lived in ...

.lynching

Lynching is an extrajudicial killing by a group. It is most often used to characterize informal public executions by a mob in order to punish an alleged or convicted transgressor or to intimidate others. It can also be an extreme form of i ...

or other forms of persecution. From 1968 to 1969, the Cleansing the Class Ranks purge caused the deaths of at least 500,000 people.One Strike-Three Anti Campaign The One Strike-Three Anti campaign () was a national campaign launched by Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in early 1970 during the Cultural Revolution. The campaign aimed to consolidate central power by targeting "counte ...

and the campaign towards the May Sixteenth elements

May Sixteenth elements () were named after the so-called May Sixteenth Army Corps (五一六兵团; 1967–1968), ultra-left Red Guards in Beijing during the early years of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976) who targeted Zhou Enlai with the bac ...

were launched in the 1970s.

Repression of ethnic minorities