Carboniferous Insects on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Carboniferous ( ) is a

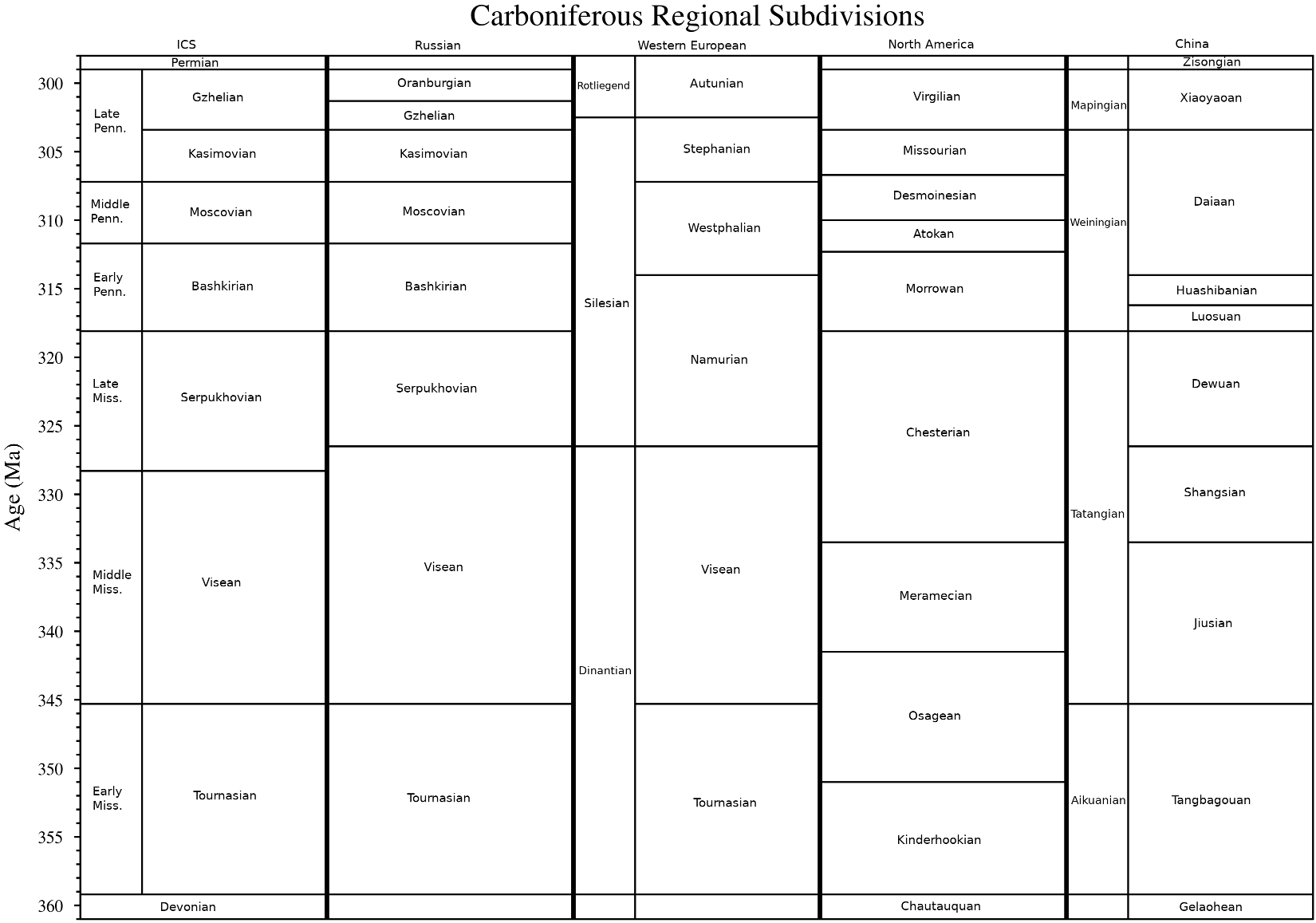

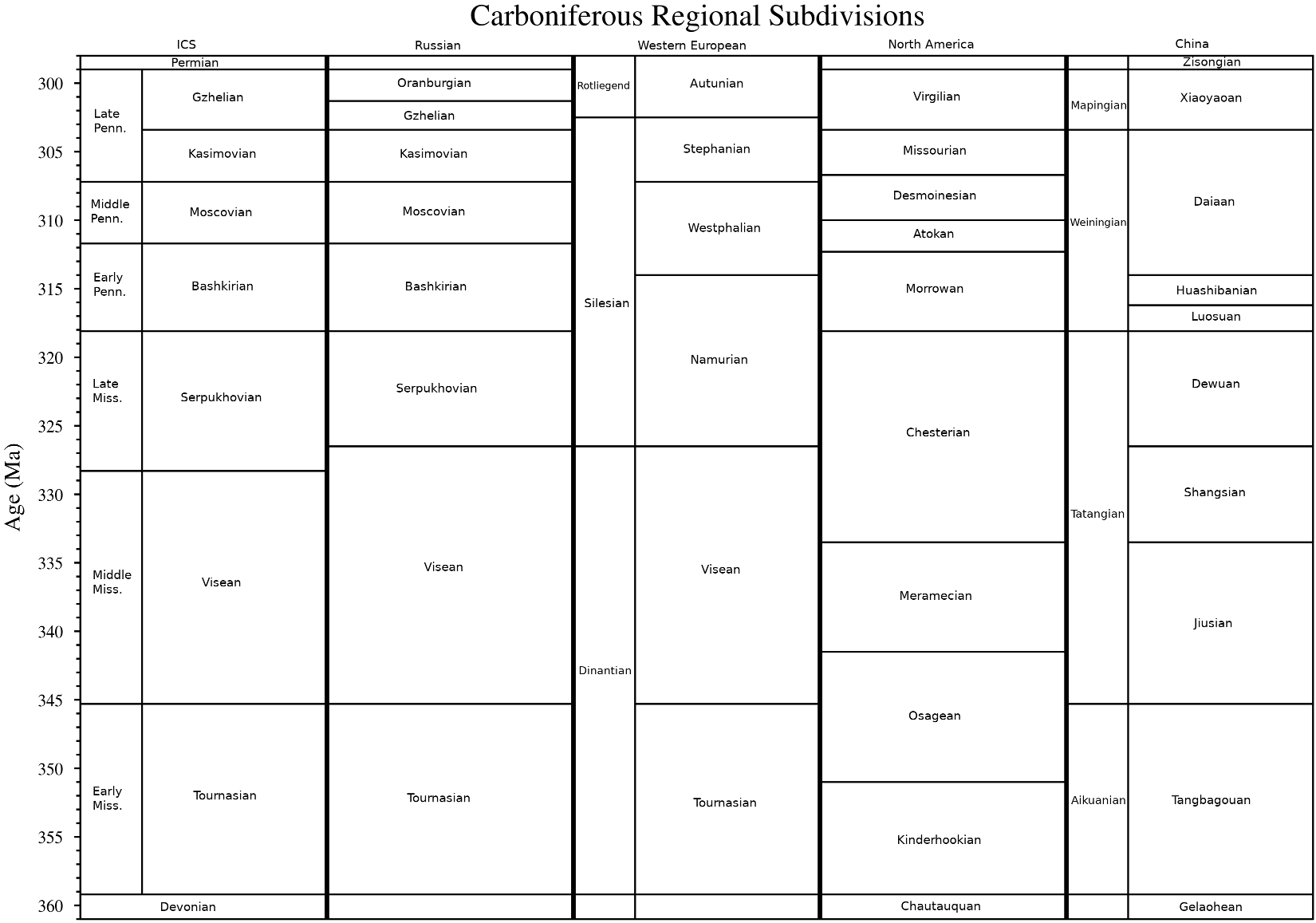

The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart

Episodes 36: 199-204.

In North American stratigraphy, the Mississippian is divided, in ascending order, into the Kinderhookian, Osagean, Meramecian and Chesterian series, while the Pennsylvanian is divided into the Morrowan, Atokan, Desmoinesian, Missourian and Virgilian series.

The Kinderhookian is named after the village of Kinderhook, Pike County, Illinois. It corresponds to the lower part of the Tournasian.

The Osagean is named after the

In North American stratigraphy, the Mississippian is divided, in ascending order, into the Kinderhookian, Osagean, Meramecian and Chesterian series, while the Pennsylvanian is divided into the Morrowan, Atokan, Desmoinesian, Missourian and Virgilian series.

The Kinderhookian is named after the village of Kinderhook, Pike County, Illinois. It corresponds to the lower part of the Tournasian.

The Osagean is named after the

Mid-Carboniferous, a drop in sea level precipitated a major marine extinction, one that hit

Mid-Carboniferous, a drop in sea level precipitated a major marine extinction, one that hit

Average global temperatures in the Early Carboniferous Period were high: approximately 20 °C (68 °F). However, cooling during the Middle Carboniferous reduced average global temperatures to about 12 °C (54 °F). Atmospheric

Average global temperatures in the Early Carboniferous Period were high: approximately 20 °C (68 °F). However, cooling during the Middle Carboniferous reduced average global temperatures to about 12 °C (54 °F). Atmospheric

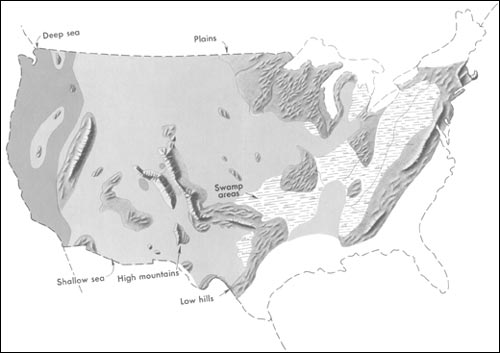

Carboniferous rocks in Europe and eastern North America largely consist of a repeated sequence of

Carboniferous rocks in Europe and eastern North America largely consist of a repeated sequence of

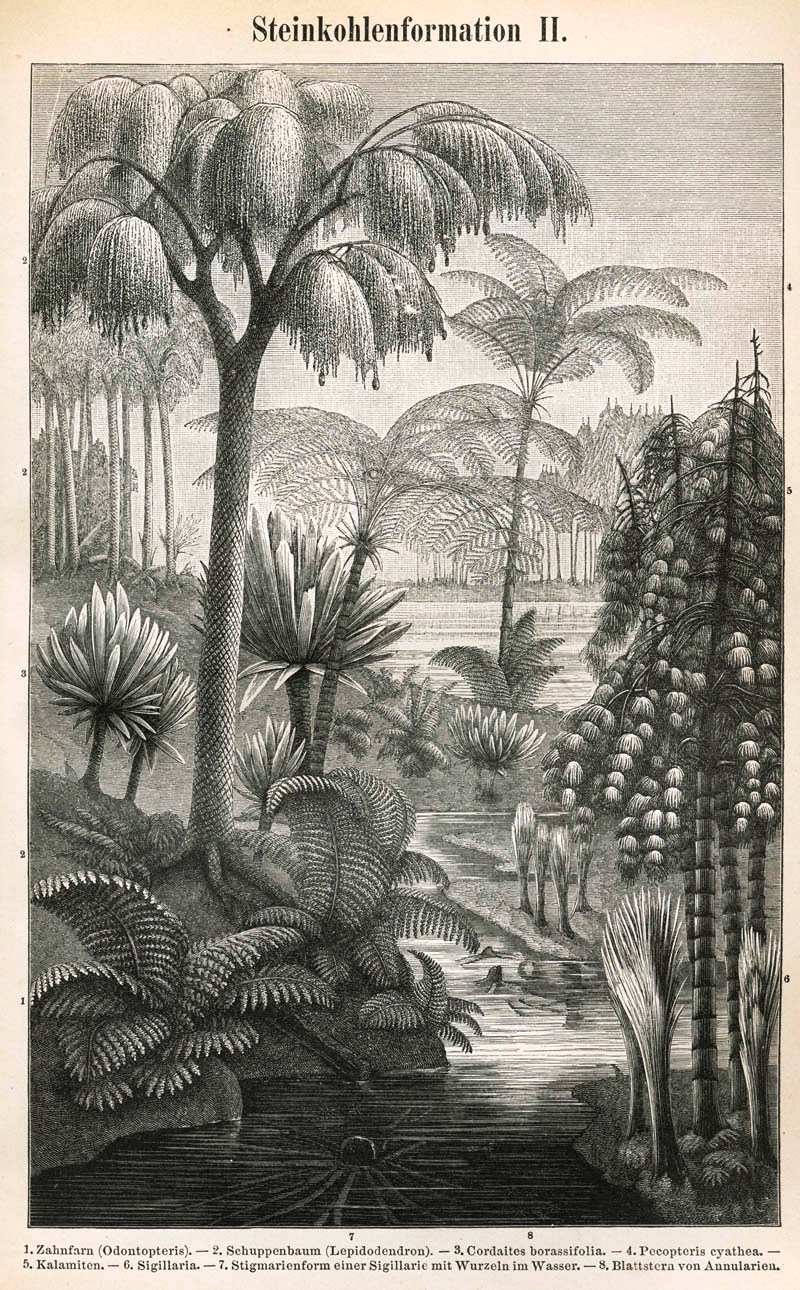

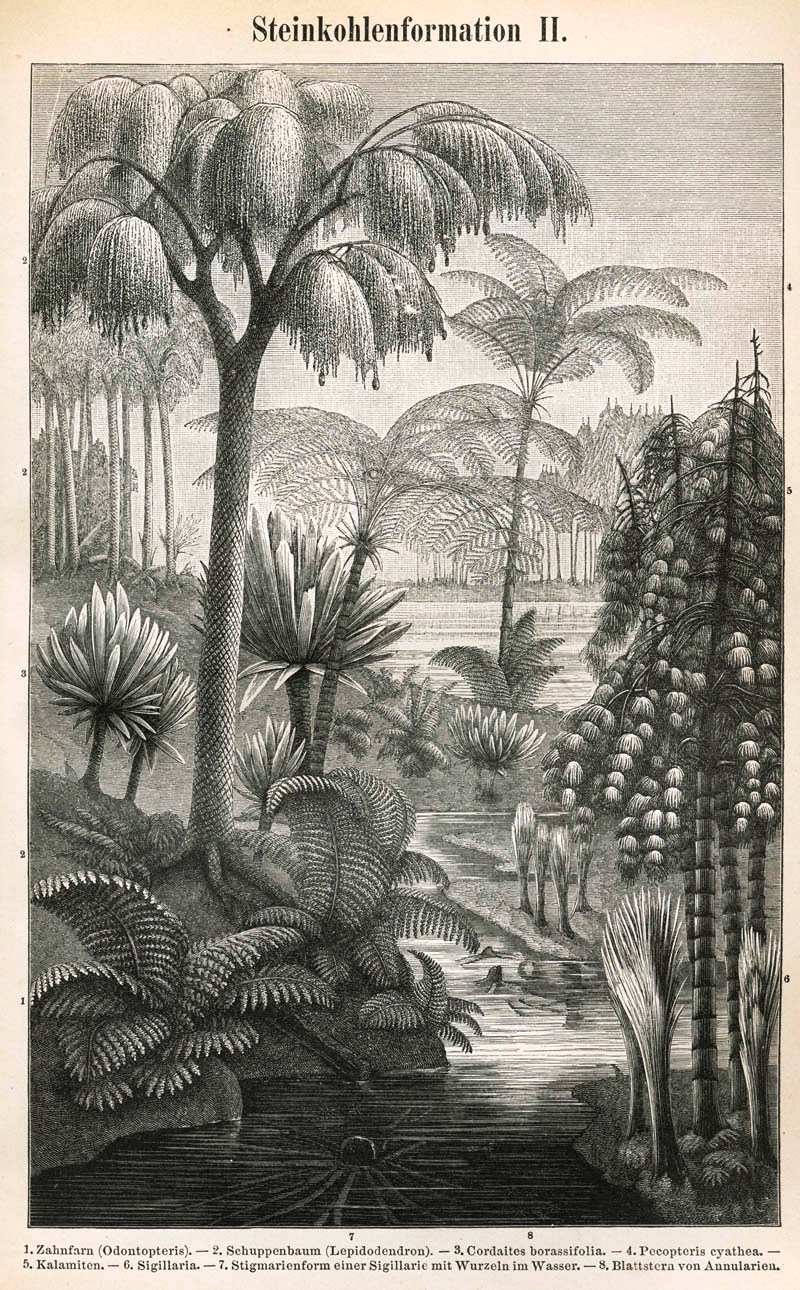

The Carboniferous lycophytes of the order Lepidodendrales, which are cousins (but not ancestors) of the tiny club-moss of today, were huge trees with trunks 30 meters high and up to 1.5 meters in diameter. These included ''

The Carboniferous lycophytes of the order Lepidodendrales, which are cousins (but not ancestors) of the tiny club-moss of today, were huge trees with trunks 30 meters high and up to 1.5 meters in diameter. These included ''

File:Aviculopecten subcardiformis01.JPG, ''Aviculopecten subcardiformis''; a

The

The

File:Meganeura monyi au Museum de Toulouse.jpg, The late Carboniferous giant dragonfly-like insect ''

File:Stethacanthus BW.jpg, '' Akmonistion'' of the

File:Pederpes22small.jpg, The

Examples of Carboniferous Fossils60+ images of Carboniferous Foraminifera

{{Authority control Geological periods

geologic period

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochr ...

and system

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its environment, is described by its boundaries, structure and purpose and express ...

of the Paleozoic

The Paleozoic (or Palaeozoic) Era is the earliest of three geologic eras of the Phanerozoic Eon.

The name ''Paleozoic'' ( ;) was coined by the British geologist Adam Sedgwick in 1838

by combining the Greek words ''palaiós'' (, "old") and ...

that spans 60 million years from the end of the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

Period million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.9 Mya. It is the last period of the Paleo ...

Period, million years ago. The name ''Carboniferous'' means "coal-bearing", from the Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

'' carbō'' ("coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

") and '' ferō'' ("bear, carry"), and refers to the many coal beds formed globally during that time.

The first of the modern 'system' names, it was coined by geologists William Conybeare and William Phillips William Phillips may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Phillips (editor) (1907–2002), American editor and co-founder of ''Partisan Review''

* William T. Phillips (1863–1937), American author

* William Phillips (director), Canadian film-make ...

in 1822, based on a study of the British rock succession. The Carboniferous is often treated in North America as two geological periods, the earlier Mississippian and the later Pennsylvanian.

Terrestrial animal life was well established by the Carboniferous Period. Tetrapod

Tetrapods (; ) are four-limbed vertebrate animals constituting the superclass Tetrapoda (). It includes extant and extinct amphibians, sauropsids ( reptiles, including dinosaurs and therefore birds) and synapsids ( pelycosaurs, extinct t ...

s (four limbed vertebrates), which had originated from lobe-finned fish

Sarcopterygii (; ) — sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii () — is a taxon (traditionally a class or subclass) of the bony fishes known as the lobe-finned fishes. The group Tetrapoda, a mostly terrestrial superclass includ ...

during the preceding Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

, became pentadactylous

In biology, dactyly is the arrangement of digits (fingers and toes) on the hands, feet, or sometimes wings of a tetrapod animal. It comes from the Greek word δακτυλος (''dáktylos'') = "finger".

Sometimes the ending "-dactylia" is use ...

in and diversified during the Carboniferous, including early amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

lineages such as temnospondyls, with the first appearance of amniote

Amniotes are a clade of tetrapod vertebrates that comprises sauropsids (including all reptiles and birds, and extinct parareptiles and non-avian dinosaurs) and synapsids (including pelycosaurs and therapsids such as mammals). They are dis ...

s, including synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes reptil ...

s (the group to which modern mammals belong) and reptile

Reptiles, as most commonly defined are the animals in the class Reptilia ( ), a paraphyletic grouping comprising all sauropsids except birds. Living reptiles comprise turtles, crocodilians, squamates ( lizards and snakes) and rhynchocephalia ...

s during the late Carboniferous. The period is sometimes called the Age of Amphibians, during which amphibians became dominant land vertebrates and diversified into many forms including lizard-like, snake-like, and crocodile-like.

Insects would undergo a major radiation during the late Carboniferous. Vast swaths of forest covered the land, which would eventually be laid down and become the coal beds characteristic of the Carboniferous stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers ( strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

evident today.

The later half of the period experienced glaciation

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate bet ...

s, low sea level, and mountain building

Mountain formation refers to the geological processes that underlie the formation of mountains. These processes are associated with large-scale movements of the Earth's crust (tectonic plates). Folding, faulting, volcanic activity, igneous intr ...

as the continents collided to form Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

. A minor marine and terrestrial extinction event, the Carboniferous rainforest collapse, occurred at the end of the period, caused by climate change.

Etymology and history

The term "Carboniferous" had first been used as an adjective by Irish geologist Richard Kirwan in 1799, and later used in a heading entitled "Coal-measures or Carboniferous Strata" byJohn Farey Sr.

John Farey Sr. (24 September 1766 – 6 January 1826) was an English geologist and writer best known for Farey sequence, a mathematical construct that is named after him.

Biography Youth and early career

Farey was born on 24 September 1766 at ...

in 1811, becoming an informal term referring to coal-bearing sequences in Britain and elsewhere in Western Europe. Four units were originally ascribed to the Carboniferous, in ascending order, the Old Red Sandstone

The Old Red Sandstone is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the northeastern seaboard of North America. It also exte ...

, Carboniferous Limestone

Carboniferous Limestone is a collective term for the succession of limestones occurring widely throughout Great Britain and Ireland that were deposited during the Dinantian epoch (geology), Epoch of the Carboniferous period (geology), Period. T ...

, Millstone Grit and the Coal Measures

In lithostratigraphy, the coal measures are the coal-bearing part of the Upper Carboniferous System. In the United Kingdom, the Coal Measures Group consists of the Upper Coal Measures Formation, the Middle Coal Measures Formation and the Lower Coa ...

. These four units were placed into a formalised Carboniferous unit by William Conybeare and William Phillips William Phillips may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Phillips (editor) (1907–2002), American editor and co-founder of ''Partisan Review''

* William T. Phillips (1863–1937), American author

* William Phillips (director), Canadian film-make ...

in 1822, and later into the Carboniferous System by Phillips in 1835. The Old Red Sandstone was later considered Devonian in age. Subsequently, separate stratigraphic schemes were developed in Western Europe, North America, and Russia. The first attempt to build an international timescale for the Carboniferous was during the Eighth International Congress on Carboniferous Stratigraphy and Geology in Moscow in 1975, when all of the modern ICS stages were proposed.

Stratigraphy

The Carboniferous is divided into two subsystems, the lower Mississippian and upper Pennsylvanian, which are sometimes treated as separate geological periods in North American stratigraphy. Stages can be defined globally or regionally. For global stratigraphic correlation, theInternational Commission on Stratigraphy

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), sometimes referred to unofficially as the "International Stratigraphic Commission", is a daughter or major subcommittee grade scientific daughter organization that concerns itself with stratigr ...

(ICS) ratify global stages based on a Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point

A Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP) is an internationally agreed upon reference point on a stratigraphic section which defines the lower boundary of a stage on the geologic time scale. The effort to define GSSPs is conducted ...

(GSSP) from a single formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondar ...

(a stratotype A stratotype or type section in geology is the physical location or outcrop of a particular reference exposure of a stratigraphic sequence or stratigraphic boundary. If the stratigraphic unit is layered, it is called a stratotype, whereas the stan ...

) identifying the lower boundary of the stage. The ICS subdivisions from youngest to oldest are as follows:Cohen, K.M., Finney, S.C., Gibbard, P.L. & Fan, J.-X. (2013; updatedThe ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart

Episodes 36: 199-204.

ICS units

The Mississippian was first proposed byAlexander Winchell

Alexander Winchell (December 31, 1824, in North East, New York – February 19, 1891, in Ann Arbor, Michigan) was a United States geologist who contributed to this field mainly as an educator and a popular lecturer and author. His views on evolu ...

, and the Pennsylvanian was proposed by J. J. Stevenson

John James Stevenson FRSE FSA FRIBA (24 August 1831 – 5 May 1908), usually referred to as J. J. Stevenson, was a British architect of the late-Victorian era. Born in Glasgow, he worked in Glasgow, Edinburgh and London. He is particularly assoc ...

in 1888, and both were proposed as distinct and independent systems by H. S. Williams in 1881.

The Tournaisian was named after the Belgian city of Tournai

Tournai or Tournay ( ; ; nl, Doornik ; pcd, Tornai; wa, Tornè ; la, Tornacum) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies southwest of Brussels on the river Scheldt. Tournai is part of Eurome ...

. It was introduced in scientific literature by Belgian geologist André Hubert Dumont

André — sometimes transliterated as Andre — is the French and Portuguese form of the name Andrew, and is now also used in the English-speaking world. It used in France, Quebec, Canada and other French-speaking countries. It is a variation ...

in 1832. The GSSP for the base of the Tournaisian is located at the La Serre

La Serre (; oc, La Sèrra) is a commune in the Aveyron department in southern France.

Population

The GSSP Golden Spike for the Tournaisian is in La Serre, with the first appearance of the conodont '' Siphonodella sulcata''. In 2006 it w ...

section in Montagne Noire

The Montagne Noire ( oc, Montanha Negra, known as the 'Black Mountain' in English) is a mountain range in central southern France. It is located at the southwestern end of the Massif Central at the juncture of the Tarn, Hérault and Aude departm ...

, southern France. It is defined by the first appearance datum

First appearance datum (FAD) is a term used by geologists and paleontologists to designate the first appearance of a species in the geologic record. FADs are determined by identifying the geologically oldest fossil discovered, to date, of a particu ...

of the conodont

Conodonts ( Greek ''kōnos'', " cone", + ''odont'', "tooth") are an extinct group of agnathan (jawless) vertebrates resembling eels, classified in the class Conodonta. For many years, they were known only from their tooth-like oral elements, whi ...

''Siphonodella sulcata

''Siphonodella'' is an extinct genus of conodonts.

''Siphonodella banraiensis'' is from the Late Devonian of Thailand. ''Siphonodella nandongensis'' is from the Early Carboniferous of the Baping Formation in China.New material of the Early Car ...

'', which was ratified in 1990. However, the GSSP was later shown to have issues, with ''Siphonodella sulcata'' being shown to occur 0.45 m below the proposed boundary.

The Viséan Stage was introduced by André Dumont in 1832. Dumont named this stage after the city of Visé

Visé (; nl, Wezet, ; wa, Vizé) is a city and municipality of Wallonia, located on the river Meuse in the province of Liège, Belgium.

The municipality consists of the following districts: Argenteau, Cheratte, Lanaye, Lixhe, Richelle ...

in Belgium's Liège Province

Liège (; wa, Lîdje ; nl, Luik ; german: Lüttich ) is the easternmost province of the Wallonia region of Belgium.

Liège Province is the only Belgian province that has borders with three countries. It borders (clockwise from the north) the ...

. The GSSP for the Visean is located in Bed 83 at the Pengchong section, Guangxi

Guangxi (; ; alternately romanized as Kwanghsi; ; za, Gvangjsih, italics=yes), officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region (GZAR), is an autonomous region of the People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam ...

, southern China, which was ratified in 2012. The GSSP for the base of the Viséan is the first appearance datum of fusulinid

The Fusulinida is an extinct order within the Foraminifera in which the tests are traditionally considered to have been composed of microgranular calcite. Like all forams, they were single-celled organisms. In advanced forms the test wall was dif ...

(an extinct group of forams

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly an ...

) '' Eoparastaffella simplex.''

The Serpukhovian Stage was proposed in 1890 by Russian stratigrapher Sergei Nikitin. It is named after the city of Serpukhov

Serpukhov ( rus, Серпухов, p=ˈsʲɛrpʊxəf) is a city in Moscow Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Oka and the Nara Rivers, south from Moscow ( from Moscow Ring Road) on the Moscow—Simferopol highway. The Moscow—Tul ...

, near Moscow

Moscow ( , US chiefly ; rus, links=no, Москва, r=Moskva, p=mɐskˈva, a=Москва.ogg) is the capital and largest city of Russia. The city stands on the Moskva River in Central Russia, with a population estimated at 13.0 million ...

. The Serpukhovian Stage currently lacks a defined GSSP. The proposed definition for the base of the Serpukhovian is the first appearance of conodont ''Lochriea ziegleri

''Lochriea'' is an extinct genus of conodonts.

Use in stratigraphy

The Visean, the second age of the Mississippian, contains four conodont biozones, two of which are named after ''Lochriea'' species:

* the zone of ''Lochriea nodosa''

* the ...

.''

The Bashkirian was named after Bashkiria, the then Russian name of the republic of Bashkortostan

The Republic of Bashkortostan or Bashkortostan ( ba, Башҡортостан Республикаһы, Bashqortostan Respublikahy; russian: Республика Башкортостан, Respublika Bashkortostan),; russian: Респу́блик� ...

in the southern Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

of Russia. The stage was introduced by Russian stratigrapher Sofia Semikhatova

Sofia ( ; bg, София, Sofiya, ) is the capital and largest city of Bulgaria. It is situated in the Sofia Valley at the foot of the Vitosha mountain in the western parts of the country. The city is built west of the Iskar river, and has ...

in 1934. The GSSP for the base of the Bashkirian is located at Arrow Canyon in Nevada, USA, which was ratified in 1996. The GSSP for the base of the Bashkirian is defined by the first appearance of the conodont ''Declinognathodus noduliferus''.''''

The Moscovian is named after Moscow, Russia, and was first introduced by Sergei Nikitin in 1890. The Moscovian currently lacks a defined GSSP.

The Kasimovian is named after the Russian city of Kasimov

Kasimov (russian: Каси́мов; tt-Cyrl, Касыйм;, Ханкирмән,Ханкирмән, Хан-Кермень, means "Khan's fortress" historically Gorodets Meshchyorsky, Novy Nizovoy) is a town in Ryazan Oblast, Russia, located on the ...

, and originally included as part of Nikitin's original 1890 definition of the Moscovian. It was first recognised as a distinct unit by A.P. Ivanov in 1926, who named it the "'' Tiguliferina''" Horizon after a kind of brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, w ...

. The Kasimovian currently lacks a defined GSSP.

The Gzhelian is named after the Russian village of Gzhel

Gzhel is a Russian style of blue and white ceramics which takes its name from the village of Gzhel and surrounding area, where it has been produced since 1802.

Overview

About thirty villages located southeast of Moscow produce pottery and sh ...

(russian: Гжель), nearby Ramenskoye, not far from Moscow. The name and type locality were defined by Sergei Nikitin in 1890. The base of the Gzhelian currently lacks a defined GSSP.

The GSSP for the base of the Permian is located in the Aidaralash River valley near Aqtöbe

Aktobe ( kz, Ақтөбе, Aqtöbe; russian: Актобе, Aktobe) is a city on the Ilek River in Kazakhstan. It is the administrative center of Aktobe Region. In 2020, it had a population of 500,757 people.

Aktobe is located in the west of K ...

, Kazakhstan, which was ratified in 1996. The beginning of the stage is defined by the first appearance of the conodont '' Streptognathodus postfusus.''

Regional stratigraphy

North America

In North American stratigraphy, the Mississippian is divided, in ascending order, into the Kinderhookian, Osagean, Meramecian and Chesterian series, while the Pennsylvanian is divided into the Morrowan, Atokan, Desmoinesian, Missourian and Virgilian series.

The Kinderhookian is named after the village of Kinderhook, Pike County, Illinois. It corresponds to the lower part of the Tournasian.

The Osagean is named after the

In North American stratigraphy, the Mississippian is divided, in ascending order, into the Kinderhookian, Osagean, Meramecian and Chesterian series, while the Pennsylvanian is divided into the Morrowan, Atokan, Desmoinesian, Missourian and Virgilian series.

The Kinderhookian is named after the village of Kinderhook, Pike County, Illinois. It corresponds to the lower part of the Tournasian.

The Osagean is named after the Osage River

The Osage River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map, accessed May 31, 2011 tributary of the Missouri River in central Missouri in the United States. The eighth-largest river ...

in St. Clair County, Missouri. It corresponds to the upper part of the Tournaisian and the lower part of the Viséan.

The Meramecian is named after the Meramec Highlands Quarry, located the near the Meramec River

The Meramec River (), sometimes spelled Maramec River, is one of the longest free-flowing waterways in the U.S. state of Missouri, draining Blanc, Caldwell, and Hawk. "Location" while wandering Blanc, Caldwell, and Hawk. "Executive Summary" f ...

, southwest of St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

, Missouri. It corresponds to the mid Viséan.

The Chesterian is named after the Chester Group

Chester is a cathedral city and the county town of Cheshire, England. It is located on the River Dee, close to the English–Welsh border. With a population of 79,645 in 2011,"2011 Census results: People and Population Profile: Chester Local ...

, a sequence of rocks named after the town of Chester, Illinois

Chester is a city in and the county seat of Randolph County, Illinois, United States, on a bluff above the Mississippi River. The population was 6,814 at the 2020 census. It lies south of St. Louis, Missouri.

History Founding

Samuel Smith is ...

. It corresponds to the upper Viséan and all of the Serpukhovian.

The Morrowan is named after the Morrow Formation located in NW Arkansas, it corresponds to the lower Bashkirian.

The Atokan was originally a formation named after the town of Atoka in southwestern Oklahoma. It corresponds to the upper Bashkirian and lower Moscovian

The Desmoinesian is named after the Des Moines Formation

The Des Moines Formation is a geologic formation in Illinois. It preserves fossils dating back to the Carboniferous period

Period may refer to:

Common uses

* Era, a length or span of time

* Full stop (or period), a punctuation mark

Arts, enter ...

found near the Des Moines River

The Des Moines River () is a tributary of the Mississippi River in the upper Midwestern United States that is approximately long from its farther headwaters.U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe Na ...

in central Iowa. It corresponds to the middle and upper Moscovian and lower Kasimovian.

The Missourian was named at the same time as the Desmoinesian. It corresponds to the middle and upper Kasimovian.

The Virgilian is named after the town of Virgil, Kansas

Virgil is a city in Greenwood County, Kansas, United States. As of the 2020 census, the population of the city was 48. It is located approximately 8 miles east of the city of Hamilton.

History

The first post office in Virgil was established ...

, it corresponds to the Gzhelian.

Europe

The European Carboniferous is divided into the lowerDinantian

Dinantian is the name of a series or epoch from the Lower Carboniferous system in Europe. It can stand for a series of rocks in Europe or the time span in which they were deposited.

The Dinantian is equal to the lower part of the Mississippian ...

and upper Silesian, the former being named for the Belgian city of Dinant

Dinant () is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Namur, Belgium. On the shores of river Meuse, in the Ardennes, it lies south-east of Brussels, south-east of Charleroi and south of the city of Namur. Dinant is situ ...

, and the latter for the Silesia

Silesia (, also , ) is a historical region of Central Europe that lies mostly within Poland, with small parts in the Czech Silesia, Czech Republic and Germany. Its area is approximately , and the population is estimated at around 8,000,000. S ...

region of Central Europe. The boundary between the two subdivisions is older than the Mississippian-Pennsylvanian boundary, lying within the lower Serpukhovian. The boundary has traditionally been marked by the first appearance of the ammonoid '' Cravenoceras leion.'' In Europe, the Dinantian is primarily marine, the so-called "Carboniferous Limestone", while the Silesian primarily known for its coal measures.

The Dinantian is divided up into two stages, the Tournaisian and Viséan. The Tournaisian is the same length as the ICS stage, but the Viséan is longer, extending into the lower Serpukhovian.

The Silesian is divided into three stages, in ascending order, the Namurian

The Namurian is a stage in the regional stratigraphy of northwest Europe with an age between roughly 326 and 313 Ma (million years ago). It is a subdivision of the Carboniferous system or period and the regional Silesian series. The Namurian ...

, Westphalian, Stephanian. The Autunian, which corresponds to the middle and upper Gzhelian, is considered a part of the overlying Rotliegend

The Rotliegend, Rotliegend Group or Rotliegendes (german: the underlying red) is a lithostratigraphic unit (a sequence of rock strata) of latest Carboniferous to Guadalupian (middle Permian) age that is found in the subsurface of large areas in wes ...

.

The Namurian is named after the city of Namur

Namur (; ; nl, Namen ; wa, Nameur) is a city and municipality in Wallonia, Belgium. It is both the capital of the province of Namur and of Wallonia, hosting the Parliament of Wallonia, the Government of Wallonia and its administration.

Na ...

in Belgium. It corresponds to the middle and upper Serpukhovian and the lower Bashkirian.

The Westphalian is named after the region of Westphalia

Westphalia (; german: Westfalen ; nds, Westfalen ) is a region of northwestern Germany and one of the three historic parts of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. It has an area of and 7.9 million inhabitants.

The territory of the regio ...

in Germany it corresponds to the upper Bashkirian and all but the uppermost Moscovian.

The Stephanian is named after the city of Saint-Étienne

Saint-Étienne (; frp, Sant-Etiève; oc, Sant Estève, ) is a city and the prefecture of the Loire department in eastern-central France, in the Massif Central, southwest of Lyon in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region.

Saint-Étienne is the ...

in eastern France. It corresponds to the uppermost Moscovian, the Kasimovian, and the lower Gzhelian.

Palaeogeography

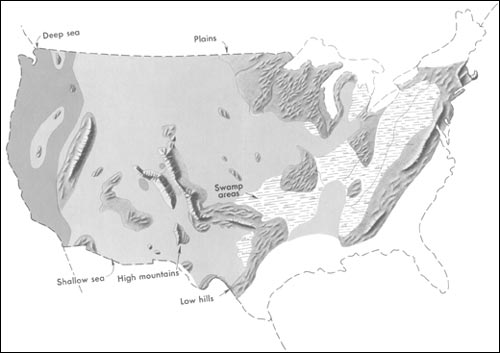

A global drop insea level

Mean sea level (MSL, often shortened to sea level) is an average surface level of one or more among Earth's coastal bodies of water from which heights such as elevation may be measured. The global MSL is a type of vertical datuma standardis ...

at the end of the Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

reversed early in the Carboniferous; this created the widespread inland seas

An inland sea (also known as an epeiric sea or an epicontinental sea) is a continental body of water which is very large and is either completely surrounded by dry land or connected to an ocean by a river, strait, or "arm of the sea". An inland se ...

and the carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid (H2CO3), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word ''carbonate'' may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate ...

deposition of the Mississippian. There was also a drop in south polar temperatures; southern Gondwana

Gondwana () was a large landmass, often referred to as a supercontinent, that formed during the late Neoproterozoic (about 550 million years ago) and began to break up during the Jurassic period (about 180 million years ago). The final sta ...

land was glaciated

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such as ...

for much of the period, though it is uncertain if the ice sheets were a holdover from the Devonian or not. These conditions apparently had little effect in the deep tropics, where lush swamps, later to become coal, flourished to within 30 degrees of the northernmost glacier

A glacier (; ) is a persistent body of dense ice that is constantly moving under its own weight. A glacier forms where the accumulation of snow exceeds its ablation over many years, often centuries. It acquires distinguishing features, such a ...

s.

Mid-Carboniferous, a drop in sea level precipitated a major marine extinction, one that hit

Mid-Carboniferous, a drop in sea level precipitated a major marine extinction, one that hit crinoids

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

and ammonites

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefis ...

especially hard. This sea level drop and the associated unconformity

An unconformity is a buried erosional or non-depositional surface separating two rock masses or strata of different ages, indicating that sediment deposition was not continuous. In general, the older layer was exposed to erosion for an interval ...

in North America separate the Mississippian Subperiod from the Pennsylvanian Subperiod. This happened about 323 million years ago, at the onset of the Permo-Carboniferous Glaciation

The Permo-Carboniferous refers to the time period including the latter parts of the Carboniferous and early part of the Permian period. Permo-Carboniferous rocks are in places not differentiated because of the presence of transitional fossils, and ...

.

The Carboniferous was a time of active mountain-building

Orogeny is a mountain building process. An orogeny is an event that takes place at a convergent plate margin when plate motion compresses the margin. An ''orogenic belt'' or ''orogen'' develops as the compressed plate crumples and is uplifted t ...

as the supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which leav ...

Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 million y ...

came together. The southern continent

A continent is any of several large landmasses. Generally identified by convention rather than any strict criteria, up to seven geographical regions are commonly regarded as continents. Ordered from largest in area to smallest, these seven ...

s remained tied together in the supercontinent Gondwana, which collided with North America–Europe (Laurussia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pan ...

) along the present line of eastern North America. This continental collision resulted in the Hercynian orogeny

The Variscan or Hercynian orogeny was a geologic mountain-building event caused by Late Paleozoic continental collision between Euramerica (Laurussia) and Gondwana to form the supercontinent of Pangaea.

Nomenclature

The name ''Variscan'', comes f ...

in Europe, and the Alleghenian orogeny

The Alleghanian orogeny or Appalachian orogeny is one of the geological mountain-forming events that formed the Appalachian Mountains and Allegheny Mountains. The term and spelling Alleghany orogeny was originally proposed by H.P. Woodward in 195 ...

in North America; it also extended the newly uplifted Appalachians

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

southwestward as the Ouachita Mountains

The Ouachita Mountains (), simply referred to as the Ouachitas, are a mountain range in western Arkansas and southeastern Oklahoma. They are formed by a thick succession of highly deformed Paleozoic strata constituting the Ouachita Fold and Thru ...

. In the same time frame, much of present eastern Eurasian plate

The Eurasian Plate is a tectonic plate that includes most of the continent of Eurasia (a landmass consisting of the traditional continents of Europe and Asia), with the notable exceptions of the Indian subcontinent, the Arabian subcontinent an ...

welded itself to Europe along the line of the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

. Most of the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era ( ), also called the Age of Reptiles, the Age of Conifers, and colloquially as the Age of the Dinosaurs is the second-to-last era of Earth's geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretace ...

supercontinent of Pangea was now assembled, although North China (which would collide in the Latest Carboniferous), and South China

South China () is a geographical and cultural region that covers the southernmost part of China. Its precise meaning varies with context. A notable feature of South China in comparison to the rest of China is that most of its citizens are not n ...

continents were still separated from Laurasia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around ( Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during the breakup of Pa ...

. The Late Carboniferous Pangaea was shaped like an "O".

There were two major oceans in the Carboniferous: Panthalassa

Panthalassa, also known as the Panthalassic Ocean or Panthalassan Ocean (from Greek "all" and "sea"), was the superocean that surrounded the supercontinent Pangaea, the latest in a series of supercontinents in the history of Earth. During th ...

and Paleo-Tethys

The Paleo-Tethys or Palaeo-Tethys Ocean was an ocean located along the northern margin of the paleocontinent Gondwana that started to open during the Middle Cambrian, grew throughout the Paleozoic, and finally closed during the Late Triassic; exi ...

, which was inside the "O" in the Carboniferous Pangaea. Other minor oceans were shrinking and eventually closed: the Rheic Ocean

The Rheic Ocean was an ocean which separated two major palaeocontinents, Gondwana and Laurussia (Laurentia- Baltica-Avalonia). One of the principal oceans of the Palaeozoic, its sutures today stretch from Mexico to Turkey and its closure result ...

(closed by the assembly of South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both east and west.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

and North America), the small, shallow Ural Ocean

The Ural Ocean (also called the Uralic Ocean) was a small, ancient ocean that was situated between Siberia and Baltica. The ocean formed in the Late Ordovician epoch, when large islands from Siberia collided with Baltica, which was then part of ...

(which was closed by the collision of Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, ...

and Siberia continents, creating the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

), and the Proto-Tethys Ocean

The Proto-Tethys or Theic Ocean was an ancient ocean that existed from the latest Ediacaran to the Carboniferous (550–330 Ma).

History of concept

The name "Proto-Tethys" has been used inconsistently for several concepts for a supposed predecess ...

(closed by North China

North China, or Huabei () is a geographical region of China, consisting of the provinces of Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Shanxi and Inner Mongolia. Part of the larger region of Northern China (''Beifang''), it lies north of the Qinling–Hu ...

collision with Siberia

Siberia ( ; rus, Сибирь, r=Sibir', p=sʲɪˈbʲirʲ, a=Ru-Сибирь.ogg) is an extensive geographical region, constituting all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has been a part ...

/Kazakhstania

Kazakhstania ( kk, Qazaqstaniya), the Kazakh terranes, or the Kazakhstan Block, is a geological region in Central Asia which consists of the area roughly centered on Lake Balkhash, north and east of the Aral Sea, south of the Siberian craton and ...

).

Climate

Average global temperatures in the Early Carboniferous Period were high: approximately 20 °C (68 °F). However, cooling during the Middle Carboniferous reduced average global temperatures to about 12 °C (54 °F). Atmospheric

Average global temperatures in the Early Carboniferous Period were high: approximately 20 °C (68 °F). However, cooling during the Middle Carboniferous reduced average global temperatures to about 12 °C (54 °F). Atmospheric carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide ( chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is t ...

levels fell during the Carboniferous Period from roughly 8 times the current level in the beginning, to a level similar to today's at the end. The Carboniferous is considered part of the Late Palaeozoic Ice Age, which began in the latest Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

with the formation of small glaciers in Gondwana. During the Tournaisian the climate warmed, before cooling, there was another warm interval during the Viséan, but cooling began again during the early Serpukhovian. At the beginning of the Pennsylvanian around 323 million years ago, glaciers began to form around the South Pole

The South Pole, also known as the Geographic South Pole, Terrestrial South Pole or 90th Parallel South, is one of the two points where Earth's axis of rotation intersects its surface. It is the southernmost point on Earth and lies antipod ...

, which would grow to cover a vast area of Gondwana. This area extended from the southern reaches of the Amazon basin

The Amazon basin is the part of South America drained by the Amazon River and its tributaries. The Amazon drainage basin covers an area of about , or about 35.5 percent of the South American continent. It is located in the countries of Boli ...

and covered large areas of southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost subregion of the African continent, south of the Congo and Tanzania. The physical location is the large part of Africa to the south of the extensive Congo River basin. Southern Africa is home to a number o ...

, as well as most of Australia and Antarctica. Cyclothems

In geology, cyclothems are alternating stratigraphic sequences of marine and non-marine sediments, sometimes interbedded with coal seams. Historically, the term was defined by the European coal geologists who worked in coal basins formed during ...

, which began around 313 million years ago, and continue into the following Permian indicate that the size of the glaciers were controlled by Milankovitch cycles

Milankovitch cycles describe the collective effects of changes in the Earth's movements on its climate over thousands of years. The term was coined and named after Serbian geophysicist and astronomer Milutin Milanković. In the 1920s, he hypot ...

akin to recent ice age

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and gre ...

s, with glacial period

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betwe ...

s and interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

s. Deep ocean temperatures during this time were cold due to the influx of cold bottom waters generated by seasonal melting of the ice cap.

The cooling and drying of the climate led to the Carboniferous Rainforest Collapse (CRC) during the late Carboniferous. Tropical rainforests fragmented and then were eventually devastated by climate change.

Rocks and coal

limestone

Limestone ( calcium carbonate ) is a type of carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different crystal forms of . Limestone forms w ...

, sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicat ...

, shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolin, Al2 Si2 O5( OH)4) and tiny fragments (silt-sized particles) of other minerals, especiall ...

and coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal is formed when ...

beds. In North America, the early Carboniferous is largely marine limestone, which accounts for the division of the Carboniferous into two periods in North American schemes. The Carboniferous coal beds provided much of the fuel for power generation during the Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was the transition to new manufacturing processes in Great Britain, continental Europe, and the United States, that occurred during the period from around 1760 to about 1820–1840. This transition included going f ...

and are still of great economic importance.

The large coal deposits of the Carboniferous may owe their existence primarily to two factors. The first of these is the appearance of wood

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin ...

tissue and bark

Bark may refer to:

* Bark (botany), an outer layer of a woody plant such as a tree or stick

* Bark (sound), a vocalization of some animals (which is commonly the dog)

Places

* Bark, Germany

* Bark, Warmian-Masurian Voivodeship, Poland

Arts, e ...

-bearing trees. The evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

of the wood fiber lignin

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants. Lignins are particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because they lend rigidity a ...

and the bark-sealing, waxy substance suberin

Suberin, cutin and lignins are complex, higher plant epidermis and periderm cell-wall macromolecules, forming a protective barrier. Suberin, a complex polyester biopolymer, is lipophilic, and composed of long chain fatty acids called suberin aci ...

variously opposed decay organisms so effectively that dead materials accumulated long enough to fossilise on a large scale. The second factor was the lower sea levels that occurred during the Carboniferous as compared to the preceding Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

Period. This fostered the development of extensive lowland swamp

A swamp is a forested wetland.Keddy, P.A. 2010. Wetland Ecology: Principles and Conservation (2nd edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK. 497 p. Swamps are considered to be transition zones because both land and water play a role in ...

s and forest

A forest is an area of land dominated by trees. Hundreds of definitions of forest are used throughout the world, incorporating factors such as tree density, tree height, land use, legal standing, and ecological function. The United Nations' ...

s in North America and Europe. Based on a genetic analysis of mushroom fungi, it was proposed that large quantities of wood

Wood is a porous and fibrous structural tissue found in the stems and roots of trees and other woody plants. It is an organic materiala natural composite of cellulose fibers that are strong in tension and embedded in a matrix of lignin ...

were buried during this period because animals and decomposing bacteria

Bacteria (; singular: bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were am ...

and fungi had not yet evolved

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variati ...

enzymes that could effectively digest the resistant phenolic lignin polymers and waxy suberin polymers. They suggest that fungi that could break those substances down effectively only became dominant towards the end of the period, making subsequent coal formation much rarer. The delayed fungal evolution hypothesis is controversial, however, and has been challenged by other researchers, who conclude that a combination of vast depositional systems present on the continents during the formation of Pangaea and widespread humid, tropical conditions were responsible for the high rate of coal formation.

The Carboniferous trees made extensive use of lignin. They had bark to wood ratios of 8 to 1, and even as high as 20 to 1. This compares to modern values less than 1 to 4. This bark, which must have been used as support as well as protection, probably had 38% to 58% lignin. Lignin is insoluble, too large to pass through cell walls, too heterogeneous for specific enzymes, and toxic, so that few organisms other than Basidiomycetes

Basidiomycota () is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Bas ...

fungi can degrade it. To oxidize it requires an atmosphere of greater than 5% oxygen, or compounds such as peroxides. It can linger in soil for thousands of years and its toxic breakdown products inhibit decay of other substances. One possible reason for its high percentages in plants at that time was to provide protection from insects in a world containing very effective insect herbivores (but nothing remotely as effective as modern plant eating insects) and probably many fewer protective toxins produced naturally by plants than exist today. As a result, undegraded carbon built up, resulting in the extensive burial of biologically fixed carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon ma ...

, leading to an increase in oxygen

Oxygen is the chemical element with the symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group in the periodic table, a highly reactive nonmetal, and an oxidizing agent that readily forms oxides with most elements ...

levels in the atmosphere; estimates place the peak oxygen content as high as 35%, as compared to 21% today. This oxygen level may have increased wildfire

A wildfire, forest fire, bushfire, wildland fire or rural fire is an unplanned, uncontrolled and unpredictable fire in an area of combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identi ...

activity. It also may have promoted gigantism

Gigantism ( el, γίγας, ''gígas'', " giant", plural γίγαντες, ''gígantes''), also known as giantism, is a condition characterized by excessive growth and height significantly above average. In humans, this condition is caused by ov ...

of insect

Insects (from Latin ') are pancrustacean hexapod invertebrates of the class Insecta. They are the largest group within the arthropod phylum. Insects have a chitinous exoskeleton, a three-part body ( head, thorax and abdomen), three pa ...

s and amphibian

Amphibians are four-limbed and ectothermic vertebrates of the class Amphibia. All living amphibians belong to the group Lissamphibia. They inhabit a wide variety of habitats, with most species living within terrestrial, fossorial, arbo ...

s, creatures whose size is today limited by their respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies gre ...

systems' ability to transport and distribute oxygen at lower atmospheric concentrations.

In eastern North America, marine beds are more common in the older part of the period than the later part and are almost entirely absent by the late Carboniferous. More diverse geology existed elsewhere, of course. Marine life is especially rich in crinoids

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

and other echinoderms

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the ...

. Brachiopods

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, wh ...

were abundant. Trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three lobes") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. Trilobites form one of the earliest-known groups of arthropods. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the ...

s became quite uncommon. On land, large and diverse plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae excl ...

populations existed. Land vertebrates

Vertebrates () comprise all animal taxa within the subphylum Vertebrata () (chordates with backbones), including all mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. Vertebrates represent the overwhelming majority of the phylum Chordata, with ...

included large amphibians.

Life

Plants

Early Carboniferous

Early may refer to:

History

* The beginning or oldest part of a defined historical period, as opposed to middle or late periods, e.g.:

** Early Christianity

** Early modern Europe

Places in the United States

* Early, Iowa

* Early, Texas

* Ear ...

land plants, some of which were preserved in coal balls, were very similar to those of the preceding Late Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a geologic period and system of the Paleozoic era, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the Silurian, million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Carboniferous, Mya. It is named after Devon, England, wh ...

, but new groups also appeared at this time.

The main Early Carboniferous plants were the Equisetales

Equisetales is an order of subclass Equisetidae with only one living family, Equisetaceae, containing the genus '' Equisetum'' (horsetails).

Classification

In the molecular phylogenetic classification of Smith et al. in 2006, Equisetales, in i ...

(horse-tails), Sphenophyllales

Sphenophyllales is an extinct order of articulate land plants and a sister group to the present-day Equisetales (horsetails). They are fossils dating from the Devonian to the Triassic. They were common during the Late Pennsylvanian to Early P ...

(scrambling plants), Lycopodiales (club mosses), Lepidodendrales

Lepidodendrales (from the Greek for "scale tree") were primitive, vascular, heterosporous, arborescent (tree-like) plants related to present day lycopsids. Members of Lepidodendrales are the best understood of the fossil lycopsids due to the vas ...

(scale trees), Filicales (ferns), Medullosales

The Medullosales is an extinct order of pteridospermous seed plants characterised by large ovules with circular cross-section and a vascularised nucellus, complex pollen-organs, stems and rachides with a dissected stele, and frond-like leaves. ...

(informally included in the "seed ferns

A seed is an Plant embryogenesis, embryonic plant enclosed in a testa (botany), protective outer covering, along with a food reserve. The formation of the seed is a part of the process of reproduction in seed plants, the spermatophytes, includ ...

", an assemblage of a number of early gymnosperm

The gymnosperms ( lit. revealed seeds) are a group of seed-producing plants that includes conifers, cycads, '' Ginkgo'', and gnetophytes, forming the clade Gymnospermae. The term ''gymnosperm'' comes from the composite word in el, γυμν ...

groups) and the Cordaitales. These continued to dominate throughout the period, but during late Carboniferous

Late may refer to:

* LATE, an acronym which could stand for:

** Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy, a proposed form of dementia

** Local-authority trading enterprise, a New Zealand business law

** Local average treatment effe ...

, several other groups, Cycadophyta

Cycads are seed plants that typically have a stout and woody (ligneous) trunk with a crown of large, hard, stiff, evergreen and (usually) pinnate leaves. The species are dioecious, that is, individual plants of a species are either male o ...

(cycads), the Callistophytales

The Callistophytales was an order of mainly scrambling and lianescent plants found in the wetland "coal swamps" of Euramerica and Cathaysia. They were characterised by having bilaterally-symmetrical, non-cupulate ovules attached to the underside ...

(another group of "seed ferns"), and the Voltziales (related to and sometimes included under the conifers

Conifers are a group of cone-bearing seed plants, a subset of gymnosperms. Scientifically, they make up the division Pinophyta (), also known as Coniferophyta () or Coniferae. The division contains a single extant class, Pinopsida. All ext ...

), appeared.

The Carboniferous lycophytes of the order Lepidodendrales, which are cousins (but not ancestors) of the tiny club-moss of today, were huge trees with trunks 30 meters high and up to 1.5 meters in diameter. These included ''

The Carboniferous lycophytes of the order Lepidodendrales, which are cousins (but not ancestors) of the tiny club-moss of today, were huge trees with trunks 30 meters high and up to 1.5 meters in diameter. These included ''Lepidodendron

''Lepidodendron'' is an extinct genus of primitive vascular plants belonging to the family Lepidodendraceae, part of a group of Lycopodiopsida known as scale trees or arborescent lycophytes, related to quillworts and lycopsids (club mosses). Th ...

'' (with its cone called Lepidostrobus), '' Anabathra'', '' Lepidophloios'' and ''Sigillaria

''Sigillaria'' is a genus of extinct, spore-bearing, arborescent (tree-like) plants. It was a lycopodiophyte, and is related to the lycopsids, or club-mosses, but even more closely to quillworts, as was its associate ''Lepidodendron''.

Fossil ...

''. The roots of several of these forms are known as Stigmaria

''Stigmaria'' is a form taxon for common fossils found in Carboniferous rocks. They represent the underground rooting structures of coal forest lycopsid trees such as '' Sigillaria'' and '' Lepidodendron''. These swamp forest trees grew to ...

. Unlike present-day trees, their secondary growth took place in the cortex

Cortex or cortical may refer to:

Biology

* Cortex (anatomy), the outermost layer of an organ

** Cerebral cortex, the outer layer of the vertebrate cerebrum, part of which is the ''forebrain''

*** Motor cortex, the regions of the cerebral cortex i ...

, which also provided stability, instead of the xylem

Xylem is one of the two types of transport tissue in vascular plants, the other being phloem. The basic function of xylem is to transport water from roots to stems and leaves, but it also transports nutrients. The word ''xylem'' is derived from ...

. The Cladoxylopsids were large trees, that were ancestors of ferns, first arising in the Carboniferous.

The fronds of some Carboniferous ferns are almost identical with those of living species. Probably many species were epiphytic. Fossil ferns and "seed ferns" include ''Pecopteris

''Pecopteris'' is a very common form genus of leaves. Most ''Pecopteris'' leaves and fronds are associated with the marattialean tree fern ''Psaronius''. However, ''Pecopteris''-type foliage also is borne on several filicalean ferns, and at le ...

'', '' Cyclopteris'', '' Neuropteris'', '' Alethopteris'', and '' Sphenopteris''; '' Megaphyton'' and '' Caulopteris'' were tree ferns.

The Equisetales included the common giant form ''Calamites

''Calamites'' is a genus of extinct arborescent (tree-like) horsetails to which the modern horsetails (genus '' Equisetum'') are closely related. Unlike their herbaceous modern cousins, these plants were medium-sized trees, growing to heights o ...

'', with a trunk diameter of 30 to and a height of up to . ''Sphenophyllum

''Sphenophyllum'' is a genus in the order Sphenophyllales

Sphenophyllales is an extinct order of articulate land plants and a sister group to the present-day Equisetales (horsetails). They are fossils dating from the Devonian to the Triassi ...

'' was a slender climbing plant with whorls of leaves, which was probably related both to the calamites and the lycopods.

''Cordaites

''Cordaites'' is an important genus of extinct gymnosperms which grew on wet ground similar to the Everglades in Florida. Brackish water mussels and crustacea are found frequently between the roots of these trees. The fossils are found in rock s ...

'', a tall plant (6 to over 30 meters) with strap-like leaves, was related to the cycads and conifers; the catkin

A catkin or ament is a slim, cylindrical flower cluster (a spike), with inconspicuous or no petals, usually wind-pollinated (anemophilous) but sometimes insect-pollinated (as in '' Salix''). They contain many, usually unisexual flowers, arrang ...

-like reproductive organs, which bore ovules/seeds, is called '' Cardiocarpus''. These plants were thought to live in swamps. True coniferous trees ('' Walchia'', of the order Voltziales) appear later in the Carboniferous, and preferred higher drier ground.

Marine invertebrates

In the oceans themarine invertebrate

Marine invertebrates are the invertebrates that live in marine habitats. Invertebrate is a blanket term that includes all animals apart from the vertebrate members of the chordate phylum. Invertebrates lack a vertebral column, and some hav ...

groups are the Foraminifera

Foraminifera (; Latin for "hole bearers"; informally called "forams") are single-celled organisms, members of a phylum or class of amoeboid protists characterized by streaming granular ectoplasm for catching food and other uses; and commonly ...

, corals

Corals are marine invertebrates within the class Anthozoa of the phylum Cnidaria. They typically form compact colonies of many identical individual polyps. Coral species include the important reef builders that inhabit tropical oceans and sec ...

, Bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary colonies. Typically about long, they have a special feeding structure called a ...

, Ostracoda

Ostracods, or ostracodes, are a class of the Crustacea (class Ostracoda), sometimes known as seed shrimp. Some 70,000 species (only 13,000 of which are extant) have been identified, grouped into several orders. They are small crustaceans, typica ...

, brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, w ...

s, ammonoids

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

, hederelloids, microconchids and echinoderm

An echinoderm () is any member of the phylum Echinodermata (). The adults are recognisable by their (usually five-point) radial symmetry, and include starfish, brittle stars, sea urchins, sand dollars, and sea cucumbers, as well as the ...

s (especially crinoid

Crinoids are marine animals that make up the class Crinoidea. Crinoids that are attached to the sea bottom by a stalk in their adult form are commonly called sea lilies, while the unstalked forms are called feather stars or comatulids, which are ...

s). The diversity of brachiopods and fusilinid foraminiferans, surged beginning in the Visean, continuing through the end of the Carboniferous, although cephalopod and nektonic conodont diversity declined. For the first time foraminifera take a prominent part in the marine faunas. The large spindle-shaped genus Fusulina and its relatives were abundant in what is now Russia, China, Japan, North America; other important genera include ''Valvulina'', ''Endothyra'', ''Archaediscus'', and ''Saccammina'' (the latter common in Britain and Belgium). Some Carboniferous genera are still extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

. The first true priapulid

Priapulida (priapulid worms, from Gr. πριάπος, ''priāpos'' 'Priapus' + Lat. ''-ul-'', diminutive), sometimes referred to as penis worms, is a phylum of unsegmented marine worms. The name of the phylum relates to the Greek god of fertility ...

s appeared during this period.

The microscopic shells of radiolaria

The Radiolaria, also called Radiozoa, are protozoa of diameter 0.1–0.2 mm that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into the inner and outer portions of endoplasm and ectoplasm. The el ...

ns are found in chert

Chert () is a hard, fine-grained sedimentary rock composed of microcrystalline or cryptocrystalline quartz, the mineral form of silicon dioxide (SiO2). Chert is characteristically of biological origin, but may also occur inorganically as a ...

s of this age in the Culm of Devon

Devon ( , historically known as Devonshire , ) is a ceremonial and non-metropolitan county in South West England. The most populous settlement in Devon is the city of Plymouth, followed by Devon's county town, the city of Exeter. Devo ...

and Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a Historic counties of England, historic county and Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people ...

, and in Russia, Germany and elsewhere. Sponges

Sponges, the members of the phylum Porifera (; meaning 'pore bearer'), are a basal animal clade as a sister of the diploblasts. They are multicellular organisms that have bodies full of pores and channels allowing water to circulate through t ...

are known from spicule

Spicules are any of various small needle-like anatomical structures occurring in organisms

Spicule may also refer to:

*Spicule (sponge), small skeletal elements of sea sponges

*Spicule (nematode), reproductive structures found in male nematodes ( ...

s and anchor ropes, and include various forms such as the Calcispongea ''Cotyliscus'' and ''Girtycoelia'', the demosponge

Demosponges (Demospongiae) are the most diverse class in the phylum Porifera. They include 76.2% of all species of sponges with nearly 8,800 species worldwide (World Porifera Database). They are sponges with a soft body that covers a har ...

''Chaetetes'', and the genus of unusual colonial glass sponges ''Titusvillia

''Titusvillia'' is an extinct genus of colonial glass sponges that existed during the carboniferous period around 300 million years ago. It is represented by a single species, ''Titusvillia drakei''.

Taxonomy

It is uncertain if taxa in the clade ...

''.

Both reef

A reef is a ridge or shoal of rock, coral or similar relatively stable material, lying beneath the surface of a natural body of water. Many reefs result from natural, abiotic processes—deposition of sand, wave erosion planing down rock ...

-building and solitary corals diversify and flourish; these include both rugose (for example, '' Caninia'', ''Corwenia'', ''Neozaphrentis''), heterocorals, and tabulate

Tabulata, commonly known as tabulate corals, are an order of extinct forms of coral. They are almost always colonial, forming colonies of individual hexagonal cells known as corallites defined by a skeleton of calcite, similar in appearance to a ...

(for example, ''Chladochonus'', ''Michelinia'') forms. Conularids

Conulariida is a poorly understood fossil group that has possible affinity with the Cnidaria. Their exact position as a taxon of extinct medusozoan cnidarians is highly speculative. Members of the Conulariida are commonly referred to as conulari ...

were well represented by ''Conularia''

Bryozoa

Bryozoa (also known as the Polyzoa, Ectoprocta or commonly as moss animals) are a phylum of simple, aquatic invertebrate animals, nearly all living in sedentary colonies. Typically about long, they have a special feeding structure called a ...

are abundant in some regions; the fenestellids including ''Fenestella'', ''Polypora'', and ''Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientis ...

'', so named because it is in the shape of an Archimedean screw

The Archimedes screw, also known as the Archimedean screw, hydrodynamic screw, water screw or Egyptian screw, is one of the earliest hydraulic machines. Using Archimedes screws as water pumps (Archimedes screw pump (ASP) or screw pump) dates bac ...

. Brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of trochozoan animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear end, w ...

s are also abundant; they include productids, some of which reached very large for brachiopods size and had very thick shells (for example, the -wide ''Gigantoproductus

''Gigantoproductus'' is a genus of extinct brachiopods in the order Productida and the family Monticuliferidae. The species were the largest of the carboniferous brachiopods, with the largest known species reaching in shell width. Such huge i ...

''), while others like ''Chonetes

''Chonetes'' is an extinct genus of brachiopods. It ranged from the Late Ordovician to the Middle Jurassic.

Species

The following species of ''Chonetes'' have been described:

* ''C. (Paeckelmannia)''

* ''C. baragwanathi''

* ''C. billingsi'' ...

'' were more conservative in form. Athyridids, spiriferids, rhynchonellids, and terebratulids are also very common. Inarticulate forms include '' Discina'' and '' Crania''. Some species and genera had a very wide distribution with only minor variations.

Annelid

The annelids (Annelida , from Latin ', "little ring"), also known as the segmented worms, are a large phylum, with over 22,000 extant species including ragworms, earthworms, and leeches. The species exist in and have adapted to various ecol ...

s such as ''Serpulites'' are common fossils in some horizons. Among the mollusca, the bivalve

Bivalvia (), in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of marine and freshwater Mollusca, molluscs that have laterally compressed bodies enclosed by a shell consisting of two hing ...

s continue to increase in numbers and importance. Typical genera include ''Aviculopecten

''Aviculopecten'' is an extinct genus of bivalve mollusc that lived from the Early Devonian to the Late Triassic in Asia, Australia, Europe, North America, and South America.Posidonomya

The Posidonia Shale (german: Posidonienschiefer, also called Schistes Bitumineux in Luxembourg) geologically known as the Sachrang Formation, is an Early Jurassic (Toarcian) geological formation of southwestern and northeast Germany, northern Swi ...

'', ''Nucula

''Nucula'' is a genus of very small saltwater clams. They are part of the family Nuculidae.

Fossil records

This genus is very ancient. Fossils are known from the Arenig to the Quaternary (age range: from 478.6 to 0.0 million years ago). Fossils ...

'', '' Carbonicola'', ''Edmondia'', and ''Modiola''. Gastropod

The gastropods (), commonly known as snails and slugs, belong to a large taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, from freshwater, and from land. T ...

s are also numerous, including the genera ''Murchisonia'', '' Euomphalus'', ''Naticopsis''. Nautiloid

Nautiloids are a group of marine cephalopods (Mollusca) which originated in the Late Cambrian and are represented today by the living ''Nautilus'' and '' Allonautilus''. Fossil nautiloids are diverse and speciose, with over 2,500 recorded specie ...

cephalopod

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda ( Greek plural , ; "head-feet") such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head ...

s are represented by tightly coiled nautilids, with straight-shelled and curved-shelled forms becoming increasingly rare. Goniatite

Goniatids, informally goniatites, are ammonoid cephalopods that form the order Goniatitida, derived from the more primitive Agoniatitida during the Middle Devonian some 390 million years ago (around Eifelian stage). Goniatites (goniatitids) survi ...

ammonoids

Ammonoids are a group of extinct marine mollusc animals in the subclass Ammonoidea of the class Cephalopoda. These molluscs, commonly referred to as ammonites, are more closely related to living coleoids (i.e., octopuses, squid and cuttlefish) ...

such as Aenigmatoceras

''Aenigmatoceras'' is a genus of ammonite cephalopods from the Carboniferous of Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the ...

are common.

Trilobite

Trilobites (; meaning "three lobes") are extinct marine arthropods that form the class Trilobita. Trilobites form one of the earliest-known groups of arthropods. The first appearance of trilobites in the fossil record defines the base of the ...