Staph. Aureus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a

''Staphylococcus aureus'' (,

''Staphylococcus aureus'' (,

While ''S. aureus'' usually acts as a commensal bacterium, asymptomatically colonizing about 30% of the human population, it can sometimes cause disease. In particular, ''S. aureus'' is one of the most common causes of

While ''S. aureus'' usually acts as a commensal bacterium, asymptomatically colonizing about 30% of the human population, it can sometimes cause disease. In particular, ''S. aureus'' is one of the most common causes of

;Staphylococcal pigments

Some strains of ''S. aureus'' are capable of producing staphyloxanthin – a golden-coloured

;Staphylococcal pigments

Some strains of ''S. aureus'' are capable of producing staphyloxanthin – a golden-coloured

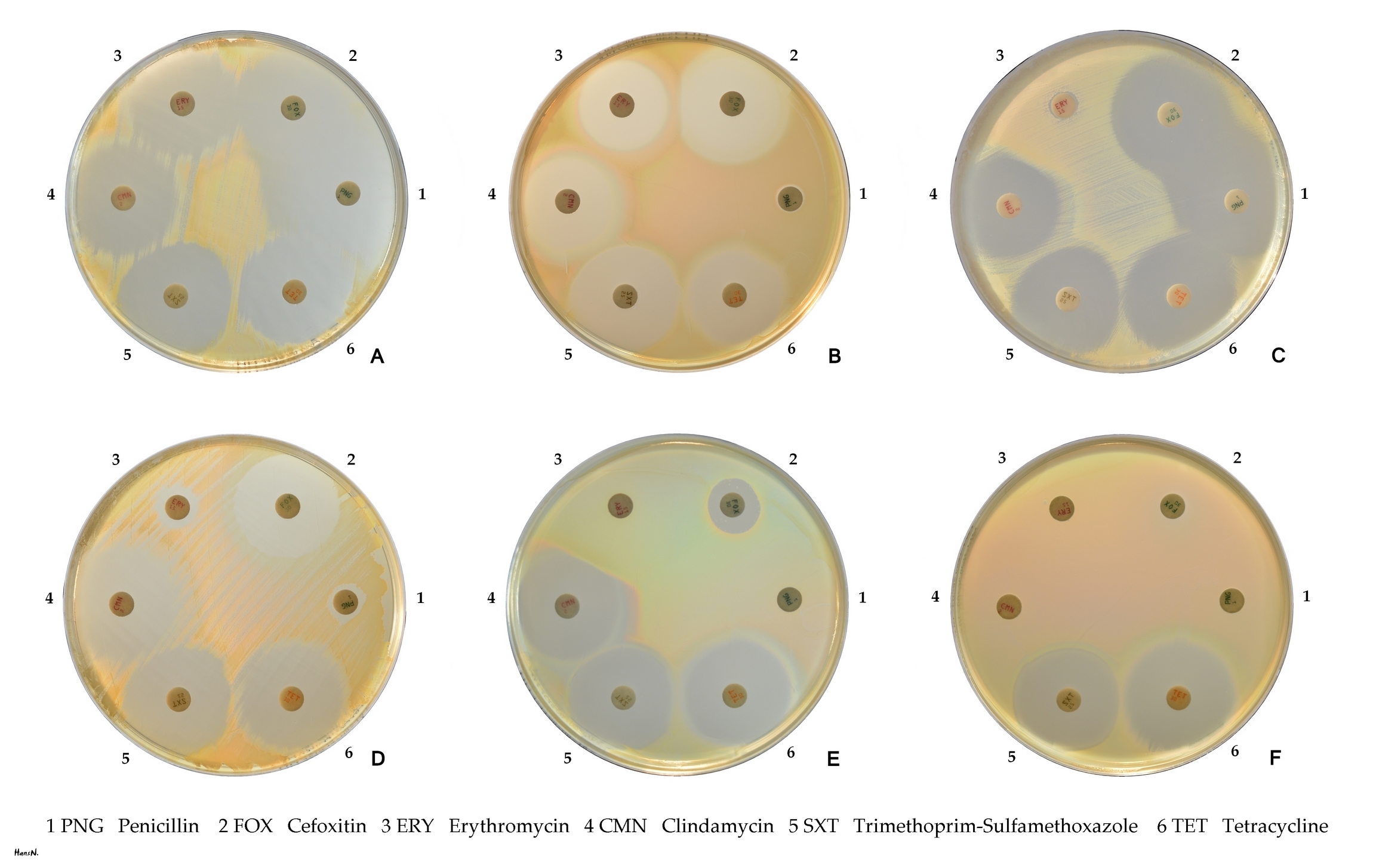

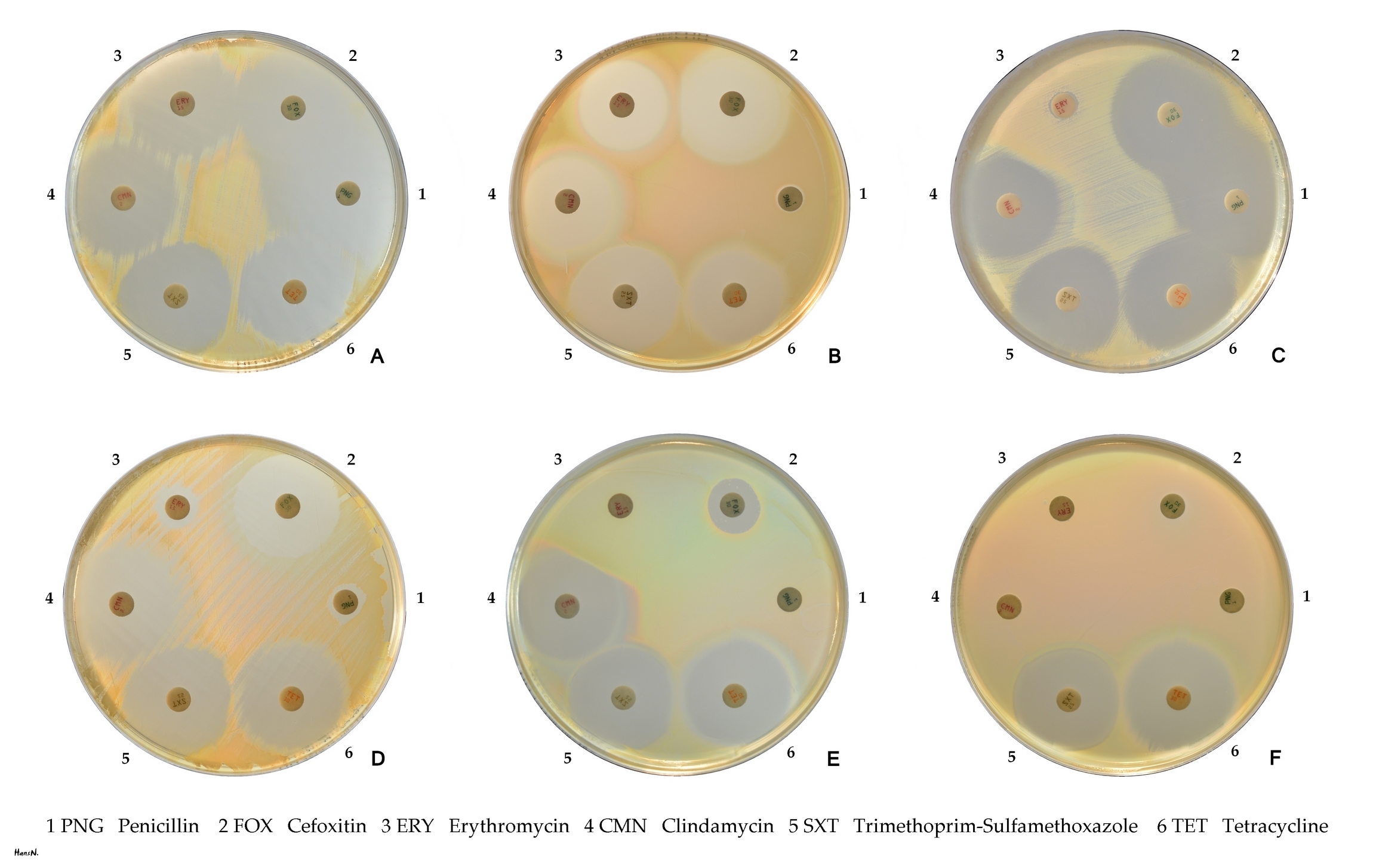

Depending upon the type of infection present, an appropriate specimen is obtained accordingly and sent to the laboratory for definitive identification by using biochemical or enzyme-based tests. A

Depending upon the type of infection present, an appropriate specimen is obtained accordingly and sent to the laboratory for definitive identification by using biochemical or enzyme-based tests. A

Resistance to methicillin is mediated via the ''mec''

Resistance to methicillin is mediated via the ''mec''

StopMRSANow.org

— Discusses how to prevent the spread of MRSA

TheMRSA.com

— Understand what the MRSA infection is all about. * *

Type strain of ''Staphylococcus aureus'' at Bac''Dive'' – the Bacterial Diversity Metadatabase

{{Authority control Food microbiology

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

The Gram stain is ...

spherically shaped bacterium

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the ...

, a member of the Bacillota

The Bacillota (synonym Firmicutes) are a phylum of bacteria, most of which have Gram-positive cell wall structure. They have round cells, called cocci (singular coccus), or rod-like forms (bacillus). A few Bacillota, such as '' Megasphaera'', ...

, and is a usual member of the microbiota

Microbiota are the range of microorganisms that may be commensal, mutualistic, or pathogenic found in and on all multicellular organisms, including plants. Microbiota include bacteria, archaea, protists, fungi, and viruses, and have been found ...

of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract

The respiratory tract is the subdivision of the respiratory system involved with the process of conducting air to the alveoli for the purposes of gas exchange in mammals. The respiratory tract is lined with respiratory epithelium as respiratory ...

and on the skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

. It is often positive for catalase

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. It is a very important enzyme in protecting ...

and nitrate reduction and is a facultative anaerobe

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

, meaning that it can grow without oxygen. Although ''S. aureus'' usually acts as a commensal

Commensalism is a long-term biological interaction (symbiosis) in which members of one species gain benefits while those of the other species neither benefit nor are harmed. This is in contrast with mutualism, in which both organisms benefit f ...

of the human microbiota, it can also become an opportunistic pathogen, being a common cause of skin infection A skin infection is an infection of the skin in humans and other animals, that can also affect the associated soft tissues such as loose connective tissue and mucous membranes. They comprise a category of infections termed skin and skin structure i ...

s including abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body, usually caused by bacterial infection. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pre ...

es, respiratory infections

Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) are infectious diseases involving the lower or upper respiratory tract. An infection of this type usually is further classified as an upper respiratory tract infection (URI or URTI) or a lower respiratory tract ...

such as sinusitis

Sinusitis, also known as rhinosinusitis, is an inflammation of the mucous membranes that line the sinuses resulting in symptoms that may include production of thick nasal mucus, nasal congestion, facial congestion, facial pain, facial pressure ...

, and food poisoning

Foodborne illness (also known as foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the contamination of food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease), and toxins such ...

. Pathogenic strains often promote infection

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

s by producing virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

s such as potent protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

toxins

A toxin is a naturally occurring poison produced by metabolic activities of living cells or organisms. They occur especially as proteins, often conjugated. The term was first used by organic chemist Ludwig Brieger (1849–1919), derived ...

, and the expression of a cell-surface protein that binds and inactivates antibodies

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as bacteria and viruses, including those that caus ...

. ''S. aureus'' is one of the leading pathogens for deaths associated with antimicrobial resistance and the emergence of antibiotic-resistant

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR or AR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from antimicrobials, which are drugs used to treat infections. This resistance affects all classes of microbes, including bacteria (antibiotic resista ...

strains, such as methicillin-resistant ''S. aureus'' (MRSA). The bacterium is a worldwide problem in clinical medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

. Despite much research and development

Research and development (R&D or R+D), known in some countries as OKB, experiment and design, is the set of innovative activities undertaken by corporations or governments in developing new services or products. R&D constitutes the first stage ...

, no vaccine

A vaccine is a biological Dosage form, preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious disease, infectious or cancer, malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verifi ...

for ''S. aureus'' has been approved.

An estimated 21% to 30% of the human population are long-term carriers of ''S. aureus'', which can be found as part of the normal skin microbiota, in the nostril

A nostril (or naris , : nares ) is either of the two orifices of the nose. They enable the entry and exit of air and other gasses through the nasal cavities. In birds and mammals, they contain branched bones or cartilages called turbinates ...

s, and as a normal inhabitant

In law and conflict of laws, domicile is relevant to an individual's "personal law", which includes the law that governs a person's status and their property. It is independent of a person's nationality. Although a domicile may change from time t ...

of the lower reproductive tract

The reproductive system of an organism, also known as the genital system, is the biological system made up of all the anatomical organs involved in sexual reproduction. Many non-living substances such as fluids, hormones, and pheromones are als ...

of females. ''S. aureus'' can cause a range of illnesses, from minor skin infections, such as pimple

A pimple or zit is a kind of comedo that results from excess sebum and dead skin cells getting trapped in the pores of the skin. In its aggravated state, it may evolve into a pustule or papule. Pimples can be treated by acne medications, anti ...

s, impetigo

Impetigo is a contagious bacterial infection that involves the superficial skin. The most common presentation is yellowish crusts on the face, arms, or legs. Less commonly there may be large blisters which affect the groin or armpits. The les ...

, boil

A boil, also called a furuncle, is a deep folliculitis, which is an infection of the hair follicle. It is most commonly caused by infection by the bacterium ''Staphylococcus aureus'', resulting in a painful swollen area on the skin caused by ...

s, cellulitis

Cellulitis is usually a bacterial infection involving the inner layers of the skin. It specifically affects the dermis and subcutaneous fat. Signs and symptoms include an area of redness which increases in size over a few days. The borders of ...

, folliculitis

Folliculitis is the infection and inflammation of one or more hair follicles. The condition may occur anywhere on hair-covered skin. The rash may appear as pimples that come to white tips on the face, chest, back, arms, legs, buttocks, or head.

A ...

, carbuncle

A carbuncle is a cluster of boils caused by bacterial infection, most commonly with ''Staphylococcus aureus'' or ''Streptococcus pyogenes''. The presence of a carbuncle is a sign that the immune system is active and fighting the infection. The ...

s, scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is a dermatological condition caused by ''Staphylococcus aureus''.

Signs and symptoms

The disease presents with the widespread formation of fluid-filled blisters that are thin walled and easily ruptured ...

, and abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body, usually caused by bacterial infection. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pre ...

es, to life-threatening diseases such as pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

, meningitis

Meningitis is acute or chronic inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, collectively called the meninges. The most common symptoms are fever, intense headache, vomiting and neck stiffness and occasion ...

, osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is the infectious inflammation of bone marrow. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The feet, spine, and hips are the most commonly involved bones in adults.

The cause is ...

, endocarditis

Endocarditis is an inflammation of the inner layer of the heart, the endocardium. It usually involves the heart valves. Other structures that may be involved include the interventricular septum, the chordae tendineae, the mural endocardium, o ...

, toxic shock syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a condition caused by Exotoxin, bacterial toxins. Symptoms may include fever, rash, skin peeling, and low blood pressure. There may also be symptoms related to the specific underlying infection such as mastitis, ...

, bacteremia

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are infections of blood caused by blood-borne pathogens. The detection of microbes in the blood (most commonly accomplished by blood cultures) is always abnormal. A bloodstream infection is different from sepsis, wh ...

, and sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

. It is still one of the five most common causes of hospital-acquired infection

A hospital-acquired infection, also known as a nosocomial infection (from the Greek , meaning "hospital"), is an infection that is acquired in a hospital or other health care, healthcare facility. To emphasize both hospital and nonhospital sett ...

s and is often the cause of wound infections following surgery

Surgery is a medical specialty that uses manual and instrumental techniques to diagnose or treat pathological conditions (e.g., trauma, disease, injury, malignancy), to alter bodily functions (e.g., malabsorption created by bariatric surgery s ...

. Each year, around 500,000 hospital patients in the United States contract a staphylococcal infection

A staphylococcal infection or staph infection is an infection caused by members of the ''Staphylococcus'' genus of bacteria.

These bacteria commonly inhabit the skin and nose where they are innocuous, but may enter the body through cuts or abrasi ...

, chiefly by ''S. aureus''. Up to 50,000 deaths each year in the U.S. are linked to staphylococcal infection.

History

Discovery

In 1880, Alexander Ogston, a Scottish surgeon, discovered that ''Staphylococcus'' can cause wound infections after noticing groups of bacteria in pus from a surgical abscess during a procedure he was performing. He named it ''Staphylococcus'' after its clustered appearance evident under a microscope. Then, in 1884, German scientistFriedrich Julius Rosenbach

Friedrich Julius Rosenbach, also known as Anton Julius Friedrich Rosenbach, (16 December 1842 – 6 December 1923) was a German physician and microbiologist. He is credited for differentiating ''Staphylococcus aureus'' and ''Staphylococcus albus' ...

identified ''Staphylococcus aureus'', discriminating and separating it from '' Staphylococcus albus'', a related bacterium. In the early 1930s, doctors began to use a more streamlined test to detect the presence of an ''S. aureus'' infection by the means of coagulase

Coagulase is a protein enzyme produced by several microorganisms that enables the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. In the laboratory, it is used to distinguish between different types of ''Staphylococcus'' isolates. Importantly, '' S. aureus' ...

testing, which enables detection of an enzyme produced by the bacterium. Prior to the 1940s, ''S. aureus'' infections were fatal in the majority of patients. However, doctors discovered that the use of penicillin could cure ''S. aureus'' infections. Unfortunately, by the end of the 1940s, penicillin resistance became widespread amongst this bacterium population and outbreaks of the resistant strain began to occur.

Evolution

''Staphylococcus aureus'' can be sorted into ten dominant human lineages. There are numerous minor lineages as well, but these are not seen in the population as often. Genomes of bacteria within the same lineage are mostly conserved, with the exception ofmobile genetic elements

Mobile genetic elements (MGEs), sometimes called selfish genetic elements, are a type of genetic material that can move around within a genome, or that can be transferred from one species or replicon to another. MGEs are found in all organisms. In ...

. Mobile genetic elements that are common in ''S. aureus'' include bacteriophages, pathogenicity island Pathogenicity islands (PAIs), as termed in 1990, are a distinct class of genomic islands acquired by microorganisms through horizontal gene transfer. Pathogenicity islands are found in both animal and plant pathogens. Additionally, PAIs are found i ...

s, plasmids

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

, transposons

A transposable element (TE), also transposon, or jumping gene, is a type of mobile genetic element, a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome.

The discovery of mobile genetic elements earned Barbara McClinto ...

, and staphylococcal cassette chromosomes. These elements have enabled ''S. aureus'' to continually evolve and gain new traits. There is a great deal of genetic variation within the ''S. aureus'' species''.'' A study by Fitzgerald et al. (2001) revealed that approximately 22% of the ''S. aureus'' genome is non-coding and thus can differ from bacterium to bacterium. An example of this difference is seen in the species' virulence. Only a few strains of ''S. aureus'' are associated with infections in humans. This demonstrates that there is a large range of infectious ability within the species.

It has been proposed that one possible reason for the great deal of heterogeneity within the species could be due to its reliance on heterogeneous infections. This occurs when multiple different types of ''S. aureus'' cause an infection within a host. The different strains can secrete different enzymes or bring different antibiotic resistances to the group, increasing its pathogenic ability. Thus, there is a need for a large number of mutations and acquisitions of mobile genetic elements.

Another notable evolutionary process within the ''S. aureus'' species is its co-evolution with its human hosts. Over time, this parasitic relationship has led to the bacterium's ability to be carried in the nasopharynx

The pharynx (: pharynges) is the part of the throat behind the mouth and nasal cavity, and above the esophagus and trachea (the tubes going down to the stomach and the lungs respectively). It is found in vertebrates and invertebrates, though its ...

of humans without causing symptoms or infection. This allows it to be passed throughout the human population, increasing its fitness as a species. However, only approximately 50% of the human population are carriers of ''S. aureus'', with 20% as continuous carriers and 30% as intermittent. This leads scientists to believe that there are many factors that determine whether ''S. aureus'' is carried asymptomatically in humans, including factors that are specific to an individual person. According to a 1995 study by Hofman et al., these factors may include age, sex, diabetes

Diabetes mellitus, commonly known as diabetes, is a group of common endocrine diseases characterized by sustained high blood sugar levels. Diabetes is due to either the pancreas not producing enough of the hormone insulin, or the cells of th ...

, and smoking. They also determined some genetic variations in humans that lead to an increased ability for ''S. aureus'' to colonize, notably a polymorphism in the glucocorticoid receptor

The glucocorticoid receptor (GR or GCR) also known by its gene name ''NR3C1'' ( nuclear receptor subfamily 3, group C, member 1) is the steroid receptor for glucocorticoids such as cortisol.

The GR is expressed in almost every cell in the bod ...

gene that results in larger corticosteroid

Corticosteroids are a class of steroid hormones that are produced in the adrenal cortex of vertebrates, as well as the synthetic analogues of these hormones. Two main classes of corticosteroids, glucocorticoids and mineralocorticoids, are invo ...

production. In conclusion, there is evidence that any strain of this bacterium can become invasive, as this is highly dependent upon human factors.

Though ''S. aureus'' has quick reproductive and micro-evolutionary rates, there are multiple barriers that prevent evolution with the species. One such barrier is AGR, which is a global accessory gene regulator within the bacteria. This such regulator has been linked to the virulence level of the bacteria. Loss of function mutations within this gene have been found to increase the fitness of the bacterium containing it. Thus, ''S. aureus'' must make a trade-off to increase their success as a species, exchanging reduced virulence for increased drug resistance. Another barrier to evolution is the Sau1 Type I restriction modification (RM) system. This system exists to protect the bacterium from foreign DNA by digesting it. Exchange of DNA between the same lineage is not blocked, since they have the same enzymes and the RM system does not recognize the new DNA as foreign, but transfer between different lineages is blocked.

Microbiology

''Staphylococcus aureus'' (,

''Staphylococcus aureus'' (, Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, ) is a facultative anaerobic

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

, Gram-positive coccal (round) bacterium also known as "golden staph" and "oro staphira". ''S. aureus'' is nonmotile and does not form spores

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual (in fungi) or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plant ...

. In medical literature, the bacterium is often referred to as ''S. aureus'', ''Staph aureus'' or ''Staph a.''. ''S. aureus'' appears as staphylococci (grape-like clusters) when viewed through a microscope, and has large, round, golden-yellow colonies, often with hemolysis

Hemolysis or haemolysis (), also known by #Nomenclature, several other names, is the rupturing (lysis) of red blood cells (erythrocytes) and the release of their contents (cytoplasm) into surrounding fluid (e.g. blood plasma). Hemolysis may ...

, when grown on blood agar plate

An agar plate is a Petri dish that contains a growth medium solidified with agar, used to culture microorganisms. Sometimes selective compounds are added to influence growth, such as antibiotics.

Individual microorganisms placed on the plate wil ...

s. ''S. aureus'' reproduces asexually by binary fission

Binary may refer to:

Science and technology Mathematics

* Binary number, a representation of numbers using only two values (0 and 1) for each digit

* Binary function, a function that takes two arguments

* Binary operation, a mathematical o ...

. Complete separation of the daughter cells is mediated by ''S. aureus'' autolysin

Autolysins are endogenous lytic enzymes that break down the peptidoglycan components of biological cells which enables the separation of daughter cells following cell division. They are involved in cell growth, cell wall metabolism, cell division ...

, and in its absence or targeted inhibition, the daughter cells remain attached to one another and appear as clusters.

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is catalase-positive (meaning it can produce the enzyme catalase). Catalase converts hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscosity, viscous than Properties of water, water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usua ...

() to water and oxygen. Catalase-activity tests are sometimes used to distinguish staphylococci from enterococci

''Enterococcus'' is a large genus of lactic acid bacteria of the phylum Bacillota. Enterococci are Gram-positive cocci that often occur in pairs (diplococci) or short chains, and are difficult to distinguish from streptococci on physical charac ...

and streptococci

''Streptococcus'' is a genus of gram-positive spherical bacteria that belongs to the family Streptococcaceae, within the order Lactobacillales (lactic acid bacteria), in the phylum Bacillota. Cell division in streptococci occurs along a sing ...

. Previously, ''S. aureus'' was differentiated from other staphylococci by the coagulase test. However, not all ''S. aureus'' strains are coagulase-positive and incorrect species identification can impact effective treatment and control measures.

Natural genetic transformation is a reproductive process involving DNA transfer from one bacterium to another through the intervening medium, and the integration of the donor sequence into the recipient genome by homologous recombination

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in Cell (biology), cellular organi ...

. ''S. aureus'' was found to be capable of natural genetic transformation, but only at low frequency under the experimental conditions employed. Further studies suggested that the development of competence for natural genetic transformation may be substantially higher under appropriate conditions, yet to be discovered.

Role in health

In humans, ''S. aureus'' can be present in the upper respiratory tract, gut mucosa, and skin as a member of the normalmicrobiota

Microbiota are the range of microorganisms that may be commensal, mutualistic, or pathogenic found in and on all multicellular organisms, including plants. Microbiota include bacteria, archaea, protists, fungi, and viruses, and have been found ...

. However, because ''S. aureus'' can cause disease under certain host and environmental conditions, it is characterized as a pathobiont.

In the United States, MRSA infections alone are estimated to cost the healthcare system over $3.2 billion annually. These infections account for nearly 20,000 deaths each year in the U.S., exceeding those caused by HIV/AIDS, Parkinson's disease, and homicide. Annually, over 119,000 bloodstream infections in the U.S. are attributed to ''S. aureus''. ''S. aureus'' infections are ranked as one of the costliest healthcare-associated infections (HAIs), with each case averaging $23,000 to $46,000 in treatment and hospital resource utilization.

On average, patients with MRSA infections experience a lengthened hospital stay of approximately 6 to 11 days, which drives up inpatient care costs. The burden extends beyond direct healthcare expenses. Indirect costs, such as lost wages, reduced productivity, and long-term disability, can significantly amplify the overall economic toll. Severe ''S. aureus'' infections, including bacteremia, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis, often require prolonged recovery and rehabilitation, affecting patients' ability to return to work or perform daily activities.

Hospitals also invest heavily in infection control protocols to limit the spread of ''S. aureus'', especially drug-resistant strains. These measures include routine screening, isolation practices, use of personal protective equipment, and antibiotic stewardship programs, which collectively contribute to rising operational costs. These necessary preventative measures can raise hospital costs by tens of thousands of dollars.

Role in disease

While ''S. aureus'' usually acts as a commensal bacterium, asymptomatically colonizing about 30% of the human population, it can sometimes cause disease. In particular, ''S. aureus'' is one of the most common causes of

While ''S. aureus'' usually acts as a commensal bacterium, asymptomatically colonizing about 30% of the human population, it can sometimes cause disease. In particular, ''S. aureus'' is one of the most common causes of bacteremia

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are infections of blood caused by blood-borne pathogens. The detection of microbes in the blood (most commonly accomplished by blood cultures) is always abnormal. A bloodstream infection is different from sepsis, wh ...

and infective endocarditis

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the inner surface of the heart (endocardium), usually the heart valve, valves. Signs and symptoms may include fever, petechia, small areas of bleeding into the skin, heart murmur, feeling tired, and anem ...

. Additionally, it can cause various skin

Skin is the layer of usually soft, flexible outer tissue covering the body of a vertebrate animal, with three main functions: protection, regulation, and sensation.

Other animal coverings, such as the arthropod exoskeleton, have different ...

and soft-tissue infections, particularly when skin or mucosal barriers have been breached.

''Staphylococcus aureus'' infections can spread

Spread may refer to:

Places

* Spread, West Virginia

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''Spread'' (film), a 2009 film.

* ''$pread'', a quarterly magazine by and for sex workers

* "Spread", a song by OutKast from their 2003 album ''Speakerboxxx/T ...

through contact with pus

Pus is an exudate, typically white-yellow, yellow, or yellow-brown, formed at the site of inflammation during infections, regardless of cause. An accumulation of pus in an enclosed tissue space is known as an abscess, whereas a visible collect ...

from an infected wound, skin-to-skin contact with an infected person, and contact with objects used by an infected person such as towels, sheets, clothing, or athletic equipment. Joint replacement

Joint replacement is a procedure of orthopedic surgery known also as arthroplasty, in which an arthritic or dysfunctional joint surface is replaced with an orthopedic prosthesis. Joint replacement is considered as a treatment when severe joint pai ...

s put a person at particular risk of septic arthritis

Acute septic arthritis, infectious arthritis, suppurative arthritis, pyogenic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or joint infection is the invasion of a joint by an infectious agent resulting in joint inflammation. Generally speaking, symptoms typica ...

, staphylococcal endocarditis

Endocarditis is an inflammation of the inner layer of the heart, the endocardium. It usually involves the heart valves. Other structures that may be involved include the interventricular septum, the chordae tendineae, the mural endocardium, o ...

(infection of the heart valves), and pneumonia

Pneumonia is an Inflammation, inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as Pulmonary alveolus, alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of Cough#Classification, productive or dry cough, ches ...

.

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a significant cause of chronic biofilm infections on medical implants, and the repressor

In molecular genetics, a repressor is a DNA- or RNA-binding protein that inhibits the expression of one or more genes by binding to the operator or associated silencers. A DNA-binding repressor blocks the attachment of RNA polymerase to the ...

of toxins is part of the infection pathway.

''Staphylococcus aureus'' can lie dormant in the body for years undetected. Once symptoms begin to show, the host is contagious for another two weeks, and the overall illness lasts a few weeks. If untreated, though, the disease can be deadly. Deeply penetrating ''S. aureus'' infections can be severe.

Skin infections

Skin infections are the most common form of ''S. aureus'' infection. This can manifest in various ways, including small benignboil

A boil, also called a furuncle, is a deep folliculitis, which is an infection of the hair follicle. It is most commonly caused by infection by the bacterium ''Staphylococcus aureus'', resulting in a painful swollen area on the skin caused by ...

s, folliculitis

Folliculitis is the infection and inflammation of one or more hair follicles. The condition may occur anywhere on hair-covered skin. The rash may appear as pimples that come to white tips on the face, chest, back, arms, legs, buttocks, or head.

A ...

, impetigo

Impetigo is a contagious bacterial infection that involves the superficial skin. The most common presentation is yellowish crusts on the face, arms, or legs. Less commonly there may be large blisters which affect the groin or armpits. The les ...

, cellulitis

Cellulitis is usually a bacterial infection involving the inner layers of the skin. It specifically affects the dermis and subcutaneous fat. Signs and symptoms include an area of redness which increases in size over a few days. The borders of ...

, and more severe, invasive soft-tissue infections.

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is extremely prevalent in persons with atopic dermatitis

Atopic dermatitis (AD), also known as atopic eczema, is a long-term type of inflammation of the skin. Atopic dermatitis is also often called simply eczema but the same term is also used to refer to dermatitis, the larger group of skin conditi ...

(AD), more commonly known as eczema. It is mostly found in fertile, active places, including the armpits, hair, and scalp. Large pimples that appear in those areas may exacerbate the infection if lacerated. Colonization of ''S. aureus'' drives inflammation of AD. ''S. aureus'' is believed to exploit defects in the skin barrier of persons with atopic dermatitis, triggering cytokine

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

expression and therefore exacerbating symptoms. This can lead to staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is a dermatology, dermatological condition caused by ''Staphylococcus aureus''.

Signs and symptoms

The disease presents with the widespread formation of fluid-filled blisters that are thin walled and ea ...

, a severe form of which can be seen in newborns

In common terminology, a baby is the very young offspring of adult human beings, while infant (from the Latin word ''infans'', meaning 'baby' or 'child') is a formal or specialised synonym. The terms may also be used to refer to juveniles of ...

.

The role of ''S. aureus'' in causing itching

An itch (also known as pruritus) is a sensation that causes a strong desire or reflex to scratch. Itches have resisted many attempts to be classified as any one type of sensory experience. Itches have many similarities to pain, and while both ...

in atopic dermatitis has been studied.

Antibiotics are commonly used to target overgrowth of ''S. aureus'' but their benefit is limited and they increase the risk of antimicrobial resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR or AR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from antimicrobials, which are drugs used to treat infections. This resistance affects all classes of microbes, including bacteria (antibiotic resista ...

. For these reasons, they are only recommended for people who not only present symptoms on the skin but feel systematically unwell.

Food poisoning

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is also responsible forfood poisoning

Foodborne illness (also known as foodborne disease and food poisoning) is any illness resulting from the contamination of food by pathogenic bacteria, viruses, or parasites,

as well as prions (the agents of mad cow disease), and toxins such ...

and achieves this by generating toxins in the food, which is then ingested. Its incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

lasts 30 minutes to eight hours, with the illness itself lasting from 30 minutes to 3 days. Preventive measures one can take to help prevent the spread of the disease include washing hands thoroughly with soap and water before preparing food. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is the National public health institutes, national public health agency of the United States. It is a Federal agencies of the United States, United States federal agency under the United S ...

recommends staying away from any food if ill, and wearing gloves if any open wounds occur on hands or wrists while preparing food. If storing food for longer than 2 hours, it is recommended to keep the food below 4.4 or above 60 °C (below 40 or above 140 °F).

Bone and joint infections

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a common cause of major bone and joint infections, includingosteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is the infectious inflammation of bone marrow. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The feet, spine, and hips are the most commonly involved bones in adults.

The cause is ...

, septic arthritis

Acute septic arthritis, infectious arthritis, suppurative arthritis, pyogenic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or joint infection is the invasion of a joint by an infectious agent resulting in joint inflammation. Generally speaking, symptoms typica ...

, and infections following joint replacement

Joint replacement is a procedure of orthopedic surgery known also as arthroplasty, in which an arthritic or dysfunctional joint surface is replaced with an orthopedic prosthesis. Joint replacement is considered as a treatment when severe joint pai ...

surgeries.

Bacteremia

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a leading cause ofbloodstream infection

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are infections of blood caused by blood-borne pathogens. The detection of microbes in the blood (most commonly accomplished by blood cultures) is always abnormal. A bloodstream infection is different from sepsis, w ...

s throughout much of the industrialized world. Infection is generally associated with breaks in the skin or mucosal membranes due to surgery, injury, or use of intravascular

Blood vessels are the tubular structures of a circulatory system that transport blood throughout many animals’ bodies. Blood vessels transport blood cells, nutrients, and oxygen to most of the tissues of a body. They also take waste and c ...

devices such as cannula

A cannula (; Latin meaning 'little reed'; : cannulae or cannulas) is a tube that can be inserted into the body, often for the delivery or removal of fluid or for the gathering of samples. In simple terms, a cannula can surround the inner or out ...

s, hemodialysis

Hemodialysis, American and British English spelling differences#ae and oe, also spelled haemodialysis, or simply ''"'dialysis'"'', is a process of filtering the blood of a person whose kidneys are not working normally. This type of Kidney dialys ...

machines, or hypodermic needle

A hypodermic needle (from Greek Language, Greek ὑπο- (''hypo-'' = under), and δέρμα (''derma'' = skin)) is a very thin, hollow tube with one sharp tip. As one of the most important intravenous inventions in the field of drug admini ...

s. Once the bacteria have entered the bloodstream, they can infect various organs, causing infective endocarditis

Infective endocarditis is an infection of the inner surface of the heart (endocardium), usually the heart valve, valves. Signs and symptoms may include fever, petechia, small areas of bleeding into the skin, heart murmur, feeling tired, and anem ...

, septic arthritis

Acute septic arthritis, infectious arthritis, suppurative arthritis, pyogenic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or joint infection is the invasion of a joint by an infectious agent resulting in joint inflammation. Generally speaking, symptoms typica ...

, and osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is the infectious inflammation of bone marrow. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The feet, spine, and hips are the most commonly involved bones in adults.

The cause is ...

. This disease is particularly prevalent and severe in the very young and very old.

Without antibiotic treatment, ''S. aureus'' bacteremia has a case fatality rate

In epidemiology, case fatality rate (CFR) – or sometimes more accurately case-fatality risk – is the proportion of people who have been diagnosed with a certain disease and end up dying of it. Unlike a disease's mortality rate, the CFR does ...

around 80%. With antibiotic treatment, case fatality rates range from 15% to 50% depending on the age and health of the patient, as well as the antibiotic resistance of the ''S. aureus'' strain.

Medical implant infections

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is often found inbiofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s formed on medical devices implanted in the body or on human tissue. It is commonly found with another pathogen, ''Candida albicans

''Candida albicans'' is an opportunistic pathogenic yeast that is a common member of the human gut flora. It can also survive outside the human body. It is detected in the gastrointestinal tract and mouth in 40–60% of healthy adults. It is usu ...

'', forming multispecies biofilms. The latter is suspected to help ''S. aureus'' penetrate human tissue. A higher mortality is linked with multispecies biofilms.

''Staphylococcus aureus'' biofilm is the predominant cause of orthopedic implant-related infections, but is also found on cardiac implants, vascular grafts, various catheter

In medicine, a catheter ( ) is a thin tubing (material), tube made from medical grade materials serving a broad range of functions. Catheters are medical devices that can be inserted in the body to treat diseases or perform a surgical procedure. ...

s, and cosmetic surgical implants. After implantation, the surface of these devices becomes coated with host proteins, which provide a rich surface for bacterial attachment and biofilm formation. Once the device becomes infected, it must be completely removed, since ''S. aureus'' biofilm cannot be destroyed by antibiotic treatments.

Current therapy for ''S. aureus'' biofilm-mediated infections involves surgical removal of the infected device followed by antibiotic treatment. Conventional antibiotic treatment alone is not effective in eradicating such infections. An alternative to postsurgical antibiotic treatment is using antibiotic-loaded, dissolvable calcium sulfate beads, which are implanted with the medical device. These beads can release high doses of antibiotics at the desired site to prevent the initial infection.

Novel treatments for ''S. aureus'' biofilm involving nano silver particles, bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

s, and plant-derived antibiotic agents are being studied. These agents have shown inhibitory effects against ''S. aureus'' embedded in biofilms. A class of enzymes have been found to have biofilm matrix-degrading ability, thus may be used as biofilm dispersal agents in combination with antibiotics.

Animal infections

''Staphylococcus aureus'' can survive on dogs, cats, and horses, and can cause bumblefoot in chickens. Some believe health-care workers' dogs should be considered a significant source of antibiotic-resistant ''S. aureus'', especially in times of outbreak. In a 2008 study by Boost, O'Donoghue, and James, it was found that just about 90% of ''S. aureus'' colonized within pet dogs presented as resistant to at least one antibiotic. The nasal region has been implicated as the most important site of transfer between dogs and humans. ''Staphylococcus aureus'' is one of the causal agents ofmastitis

Mastitis is inflammation of the breast or udder, usually associated with breastfeeding. Symptoms typically include local pain and redness. There is often an associated fever and general soreness. Onset is typically fairly rapid and usually occ ...

in dairy cow

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are called co ...

s. Its large polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

capsule protects the organism from recognition by the cow's immune defenses.

Virulence factors

Enzymes

''Staphylococcus aureus'' produces various enzymes such ascoagulase

Coagulase is a protein enzyme produced by several microorganisms that enables the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin. In the laboratory, it is used to distinguish between different types of ''Staphylococcus'' isolates. Importantly, '' S. aureus' ...

(bound and free coagulases) which facilitates the conversion of fibrinogen to fibrin to cause clots which is important in skin infections. Hyaluronidase

Hyaluronidases are a family of enzymes that catalyse the degradation of hyaluronic acid. Karl Meyer classified these enzymes in 1971, into three distinct groups, a scheme based on the enzyme reaction products. The three main types of hyaluroni ...

(also known as spreading factor) breaks down hyaluronic acid

Hyaluronic acid (; abbreviated HA; conjugate base hyaluronate), also called hyaluronan, is an anionic, nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan distributed widely throughout connective, epithelial, and neural tissues. It is unique among glycosaminog ...

and helps in spreading it. Deoxyribonuclease

Deoxyribonuclease (DNase, for short) refers to a group of glycoprotein endonucleases which are enzymes that catalyze the hydrolytic cleavage of phosphodiester linkages in the DNA backbone, thus degrading DNA. The role of the DNase enzyme in cells ...

, which breaks down the DNA, protects ''S. aureus'' from neutrophil extracellular trap-mediated killing. ''S. aureus'' also produces lipase

In biochemistry, lipase ( ) refers to a class of enzymes that catalyzes the hydrolysis of fats. Some lipases display broad substrate scope including esters of cholesterol, phospholipids, and of lipid-soluble vitamins and sphingomyelinases; howe ...

to digest lipids, staphylokinase to dissolve fibrin and aid in spread, and beta-lactamase

Beta-lactamases (β-lactamases) are enzymes () produced by bacteria that provide multi-resistance to beta-lactam antibiotics such as penicillins, cephalosporins, cephamycins, monobactams and carbapenems ( ertapenem), although carbapene ...

for drug resistance.

Toxins

Depending on the strain, ''S. aureus'' is capable of secreting severalexotoxin

An exotoxin is a toxin secreted by bacteria. An exotoxin can cause damage to the host by destroying cells or disrupting normal cellular metabolism. They are highly potent and can cause major damage to the host. Exotoxins may be secreted, or, sim ...

s, which can be categorized into three groups. Many of these toxins are associated with specific diseases.

;Superantigens

:Antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

s known as superantigen

(SAgs) are a class of antigens that result in excessive activation of the immune system. Specifically they cause non-specific activation of T-cells resulting in polyclonal T cell activation and massive cytokine release. Superantigens act by ...

s can induce toxic shock syndrome

Toxic shock syndrome (TSS) is a condition caused by Exotoxin, bacterial toxins. Symptoms may include fever, rash, skin peeling, and low blood pressure. There may also be symptoms related to the specific underlying infection such as mastitis, ...

(TSS). This group comprises 25 staphylococcal enterotoxins (SEs) which have been identified to date and named alphabetically (SEA–SEZ), including enterotoxin type B

In the field of molecular biology, enterotoxin type B, also known as Staphylococcal enterotoxin B (SEB), is an enterotoxin produced by the gram-positive bacteria ''Staphylococcus aureus''. It is a common cause of food poisoning, with severe ...

as well as the toxic shock syndrome toxin TSST-1 which causes TSS associated with tampon

A tampon is a menstrual product designed to absorb blood and vaginal secretions by insertion into the vagina during menstruation. Unlike a pad, it is placed internally, inside of the vaginal canal. Once inserted correctly, a tampon is held ...

use. Toxic shock syndrome is characterized by fever

Fever or pyrexia in humans is a symptom of an anti-infection defense mechanism that appears with Human body temperature, body temperature exceeding the normal range caused by an increase in the body's temperature Human body temperature#Fever, s ...

, erythematous rash, low blood pressure

Hypotension, also known as low blood pressure, is a cardiovascular condition characterized by abnormally reduced blood pressure. Blood pressure is the force of blood pushing against the walls of the arteries as the heart pumps out blood and is ...

, shock

Shock may refer to:

Common uses

Healthcare

* Acute stress reaction, also known as psychological or mental shock

** Shell shock, soldiers' reaction to battle trauma

* Circulatory shock, a medical emergency

** Cardiogenic shock, resulting from ...

, multiple organ failure

Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) is altered organ function in an acutely ill patient requiring immediate medical intervention.

There are different stages of organ dysfunction for certain different organs, both in acute and in chronic ...

, and skin peeling. Lack of antibody to TSST-1 plays a part in the pathogenesis of TSS. Other strains of ''S. aureus'' can produce an enterotoxin

An enterotoxin is a protein exotoxin released by a microorganism that targets the intestines. They can be chromosomally or plasmid encoded. They are heat labile (> 60 °C), of low molecular weight and water-soluble. Enterotoxins are frequently cy ...

that is the causative agent of a type of gastroenteritis

Gastroenteritis, also known as infectious diarrhea, is an inflammation of the Human gastrointestinal tract, gastrointestinal tract including the stomach and intestine. Symptoms may include diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Fever, lack of ...

. This form of gastroenteritis is self-limiting, characterized by vomiting and diarrhea 1–6 hours after ingestion of the toxin, with recovery in 8 to 24 hours. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and major abdominal pain.

;Exfoliative toxins

: Exfoliative toxins are exotoxins implicated in the disease staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome

Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS) is a dermatology, dermatological condition caused by ''Staphylococcus aureus''.

Signs and symptoms

The disease presents with the widespread formation of fluid-filled blisters that are thin walled and ea ...

(SSSS), which occurs most commonly in infants and young children. It also may occur as epidemics in hospital nurseries. The protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

activity of the exfoliative toxins causes peeling of the skin observed with SSSS.

;Other toxins

: Staphylococcal toxins that act on cell membranes include alpha toxin, beta toxin, delta toxin, and several bicomponent toxins. Strains of ''S. aureus'' can host phage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structures tha ...

s, such as the prophage

A prophage is a bacteriophage (often shortened to "phage") genome that is integrated into the circular bacterial chromosome or exists as an extrachromosomal plasmid within the bacterial cell (biology), cell. Integration of prophages into the bacte ...

Φ-PVL that produces Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), to increase virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most cases, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its abili ...

. The bicomponent toxin PVL is associated with severe necrotizing pneumonia in children. The genes encoding the components of PVL are encoded on a bacteriophage

A bacteriophage (), also known informally as a phage (), is a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria. The term is derived . Bacteriophages are composed of proteins that Capsid, encapsulate a DNA or RNA genome, and may have structu ...

found in community-associated MRSA strains.

Type VII secretion system

A secretion system is a highly specialised multi-protein unit that is embedded in the cell envelope with the function of translocating effector proteins from inside of the cell to the extracellular space or into a target host cytosol. The exact structure and function of T7SS is yet to be fully elucidated. Currently, four proteins are known components of ''S. aureus'' type VII secretion system; EssC is a large integral membraneATPase

ATPases (, Adenosine 5'-TriPhosphatase, adenylpyrophosphatase, ATP monophosphatase, triphosphatase, ATP hydrolase, adenosine triphosphatase) are a class of enzymes that catalyze the decomposition of ATP into ADP and a free phosphate ion or ...

– which most likely powers the secretion systems and has been hypothesised forming part of the translocation channel. The other proteins are EsaA, EssB, EssA, that are membrane proteins that function alongside EssC to mediate protein secretion. The exact mechanism of how substrates reach the cell surface is unknown, as is the interaction of the three membrane proteins with each other and EssC.

T7 dependent effector proteins

EsaD is DNA endonuclease

In molecular biology, endonucleases are enzymes that cleave the phosphodiester bond within a polynucleotide chain (namely DNA or RNA). Some, such as deoxyribonuclease I, cut DNA relatively nonspecifically (with regard to sequence), while man ...

toxin secreted by ''S. aureus'', has been shown to inhibit growth of competitor ''S. aureus'' strain ''in vitro''. EsaD is cosecreted with chaperone EsaE, which stabilises EsaD structure and brings EsaD to EssC for secretion. Strains that produce EsaD also co-produce EsaG, a cytoplasmic anti-toxin that protects the producer strain from EsaD's toxicity.

TspA is another toxin that mediates intraspecies competition. It is a bacteriostatic toxin that has a membrane depolarising activity facilitated by its C-terminal domain

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, carboxy tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein or polypeptide), terminated by a free carboxyl group (-COOH). When t ...

. Tsai is a transmembrane protein that confers immunity to the producer strain of TspA, as well as the attacked strains. There is genetic variability of the C-terminal domain of TspA therefore, it seems like the strains may produce different TspA variants to increase competitiveness.

Toxins that play a role in intraspecies competition confers an advantage by promoting successful colonisation in polymicrobial communities such as the nasopharynx and lung by outcompeting lesser strains.

There are also T7 effector proteins that play role a in pathogenesis, for example mutational studies of ''S. aureus'' have suggested that EsxB and EsxC contribute to persistent infection in a murine abscess model.

EsxX has been implicated in neutrophil

Neutrophils are a type of phagocytic white blood cell and part of innate immunity. More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. Their functions vary in differe ...

lysis, therefore suggested as contributing to the evasion of host immune system. Deletion of ''essX'' in ''S. aureus'' resulted in significantly reduced resistance to neutrophils and reduced virulence in murine skin and blood infection models.

Altogether, T7SS and known secreted effector proteins are a strategy of pathogenesis by improving fitness against competitor ''S. aureus'' species as well as increased virulence via evading the innate immune system and optimising persistent infections.

Small RNA

The list ofsmall RNA

Small RNA (sRNA) are polymeric RNA molecules that are less than 200 nucleotides in length, and are usually non-coding RNA, non-coding. RNA silencing is often a function of these molecules, with the most common and well-studied example being RNA int ...

s involved in the control of bacterial virulence in ''S. aureus'' is growing. This can be facilitated by factors such as increased biofilm formation in the presence of increased levels of such small RNAs. For example, RNAIII

RNAIII is a stable 514 nt regulatory RNA transcribed by the P3 promoter of the ''Staphylococcus aureus'' quorum-sensing '' agr'' system ). It is the major effector of the ''agr'' regulon, which controls the expression of many '' S. aureus'' gene ...

, SprD, SprC, RsaE, SprA1, SSR42, ArtR, SprX, Teg49, and IsrR.

DNA repair

Hostneutrophil

Neutrophils are a type of phagocytic white blood cell and part of innate immunity. More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. Their functions vary in differe ...

s cause DNA double-strand breaks in ''S. aureus'' through the production of reactive oxygen species

In chemistry and biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (), water, and hydrogen peroxide. Some prominent ROS are hydroperoxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl ...

. For infection of a host to be successful, ''S. aureus'' must survive such damages caused by the hosts' defenses. The two protein complex RexAB encoded by ''S. aureus'' is employed in the recombinational repair

Homologous recombination is a type of genetic recombination in which genetic information is exchanged between two similar or identical molecules of double-stranded or single-stranded nucleic acids (usually DNA as in Cell (biology), cellular organi ...

of DNA double-strand breaks.

Strategies for post-transcriptional regulation by 3'untranslated region

Many mRNAs in ''S. aureus'' carrythree prime untranslated region

In molecular genetics, the three prime untranslated region (3′-UTR) is the section of messenger RNA (mRNA) that immediately follows the translation termination codon. The 3′-UTR often contains regulatory regions that post-transcriptionally ...

s (3'UTR) longer than 100 nucleotide

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

s, which may potentially have a regulatory function.

Further investigation of i''caR'' mRNA (mRNA coding for the repressor of the main expolysaccharidic compound of the bacteria biofilm matrix) demonstrated that the 3'UTR binding to the 5' UTR

The 5′ untranslated region (also known as 5′ UTR, leader sequence, transcript leader, or leader RNA) is the region of a messenger RNA (mRNA) that is directly Upstream and downstream (DNA), upstream from the initiation codon. This region is im ...

can interfere with the translation initiation complex and generate a double stranded substrate for RNase III

Ribonuclease III (RNase III or RNase C) (BREND3.1.26.3 is a type of ribonuclease that recognizes dsRNA and cleaves it at specific targeted locations to transform them into mature RNAs. These enzymes are a group of endoribonucleases that are cha ...

. The interaction is between the UCCCCUG motif in the 3'UTR and the Shine-Dalagarno region at the 5'UTR. Deletion of the motif resulted in IcaR repressor accumulation and inhibition of biofilm development. The biofilm formation is the main cause of ''Staphylococcus'' implant infections.

Biofilm

Biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s are groups of microorganisms, such as bacteria, that attach to each other and grow on wet surfaces.Vidyasagar, A. (2016). What Are Biofilms? ''Live Science.'' The ''S. aureus'' biofilm is embedded in a glycocalyx

The glycocalyx (: glycocalyces or glycocalyxes), also known as the pericellular matrix and cell coat, is a layer of glycoproteins and glycolipids which surround the cell membranes of bacteria, epithelial cells, and other cells.

Animal epithe ...

slime layer and can consist of teichoic acid

Teichoic acids (''cf.'' Greek τεῖχος, ''teīkhos'', "wall", to be specific a fortification wall, as opposed to τοῖχος, ''toīkhos'', a regular wall) are bacterial copolymers of glycerol phosphate or ribitol phosphate and carbohyd ...

s, host proteins, extracellular DNA (eDNA) and sometimes polysaccharide intercellular antigen (PIA). S. aureus biofilms are important in disease pathogenesis, as they can contribute to antibiotic resistance and immune system evasion. ''S. aureus'' biofilm has high resistance to antibiotic treatments and host immune response. One hypothesis for explaining this is that the biofilm matrix protects the embedded cells by acting as a barrier to prevent antibiotic penetration. However, the biofilm matrix is composed with many water channels, so this hypothesis is becoming increasingly less likely, but a biofilm matrix possibly contains antibiotic‐degrading enzymes such as β-lactamases, which can prevent antibiotic penetration. Another hypothesis is that the conditions in the biofilm matrix favor the formation of persister cells, which are highly antibiotic-resistant, dormant bacterial cells. ''S. aureus'' biofilms also have high resistance to host immune response. Though the exact mechanism of resistance is unknown, ''S. aureus'' biofilms have increased growth under the presence of cytokine

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

s produced by the host immune response. Host antibodies are less effective for ''S. aureus'' biofilm due to the heterogeneous antigen

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

...

distribution, where an antigen may be present in some areas of the biofilm, but completely absent from other areas.

Studies in biofilm development have shown to be related to changes in gene expression. There are specific genes that were found to be crucial in the different biofilm growth stages. Two of these genes include rocD and gudB, which encode for the enzyme's ornithine-oxo-acid transaminase and glutamate dehydrogenase

Glutamate dehydrogenase (GLDH, GDH) is an enzyme observed in both prokaryotes and eukaryotic mitochondria. The aforementioned reaction also yields ammonia, which in eukaryotes is canonically processed as a substrate in the urea cycle. Typic ...

, which are important for amino acid metabolism. Studies have shown biofilm development rely on amino acids glutamine

Glutamine (symbol Gln or Q) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Its side chain is similar to that of glutamic acid, except the carboxylic acid group is replaced by an amide. It is classified as a charge-neutral ...

and glutamate

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; known as glutamate in its anionic form) is an α-amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a Essential amino acid, non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that ...

for proper metabolic functions.

Other immunoevasive strategies

;Protein AProtein A

Protein A is a 42 kDa surface protein originally found in the cell wall of the bacteria ''Staphylococcus aureus''. It is encoded by the ''spa'' gene and its regulation is controlled by DNA topology, cellular osmolarity, and a two-component syst ...

is anchored to staphylococcal peptidoglycan

Peptidoglycan or murein is a unique large macromolecule, a polysaccharide, consisting of sugars and amino acids that forms a mesh-like layer (sacculus) that surrounds the bacterial cytoplasmic membrane. The sugar component consists of alternating ...

pentaglycine bridges (chains of five glycine

Glycine (symbol Gly or G; ) is an amino acid that has a single hydrogen atom as its side chain. It is the simplest stable amino acid. Glycine is one of the proteinogenic amino acids. It is encoded by all the codons starting with GG (G ...

residues) by the transpeptidase sortase A. Protein A, an IgG

Immunoglobulin G (IgG) is a type of antibody. Representing approximately 75% of serum antibodies in humans, IgG is the most common type of antibody found in blood circulation. IgG molecules are created and released by plasma B cells. Each IgG ant ...

-binding protein, binds to the Fc region

The fragment crystallizable region (Fc region) is the tail region of an antibody that interacts with cell surface receptors called Fc receptors and some proteins of the complement system. This region allows antibodies to activate the immune sys ...

of an antibody

An antibody (Ab) or immunoglobulin (Ig) is a large, Y-shaped protein belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily which is used by the immune system to identify and neutralize antigens such as pathogenic bacteria, bacteria and viruses, includin ...

. In fact, studies involving mutation of genes coding for protein A resulted in a lowered virulence of ''S. aureus'' as measured by survival in blood, which has led to speculation that protein A-contributed virulence requires binding of antibody Fc regions.

Protein A in various recombinant forms has been used for decades to bind and purify a wide range of antibodies by immunoaffinity chromatography. Transpeptidases, such as the sortases responsible for anchoring factors like protein A to the staphylococcal peptidoglycan, are being studied in hopes of developing new antibiotics to target MRSA infections.

;Staphylococcal pigments

Some strains of ''S. aureus'' are capable of producing staphyloxanthin – a golden-coloured

;Staphylococcal pigments

Some strains of ''S. aureus'' are capable of producing staphyloxanthin – a golden-coloured carotenoid

Carotenoids () are yellow, orange, and red organic pigments that are produced by plants and algae, as well as several bacteria, archaea, and fungi. Carotenoids give the characteristic color to pumpkins, carrots, parsnips, corn, tomatoes, cana ...

pigment

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly solubility, insoluble and reactivity (chemistry), chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored sub ...

. This pigment acts as a virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

, primarily by being a bacterial antioxidant

Antioxidants are Chemical compound, compounds that inhibit Redox, oxidation, a chemical reaction that can produce Radical (chemistry), free radicals. Autoxidation leads to degradation of organic compounds, including living matter. Antioxidants ...

which helps the microbe evade the reactive oxygen species

In chemistry and biology, reactive oxygen species (ROS) are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive chemicals formed from diatomic oxygen (), water, and hydrogen peroxide. Some prominent ROS are hydroperoxide (H2O2), superoxide (O2−), hydroxyl ...

which the host immune system uses to kill pathogens.

Mutant strains of ''S. aureus'' modified to lack staphyloxanthin are less likely to survive incubation with an oxidizing chemical, such as hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscosity, viscous than Properties of water, water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usua ...

, than pigmented strains. Mutant colonies are quickly killed when exposed to human neutrophils

Neutrophils are a type of phagocytic white blood cell and part of innate immunity. More specifically, they form the most abundant type of granulocytes and make up 40% to 70% of all white blood cells in humans. Their functions vary in different ...

, while many of the pigmented colonies survive. In mice, the pigmented strains cause lingering abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body, usually caused by bacterial infection. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pre ...

es when inoculated into wounds, whereas wounds infected with the unpigmented strains quickly heal.

These tests suggest the ''Staphylococcus'' strains use staphyloxanthin as a defence against the normal human immune system. Drugs designed to inhibit the production of staphyloxanthin may weaken the bacterium and renew its susceptibility to antibiotics. In fact, because of similarities in the pathways for biosynthesis of staphyloxanthin and human cholesterol

Cholesterol is the principal sterol of all higher animals, distributed in body Tissue (biology), tissues, especially the brain and spinal cord, and in Animal fat, animal fats and oils.

Cholesterol is biosynthesis, biosynthesized by all anima ...

, a drug developed in the context of cholesterol-lowering therapy was shown to block ''S. aureus'' pigmentation and disease progression in a mouse infection model.

;Resistance to Hypothiocyanous Acid (HOSCN)

''Staphylococcus aureus'' has developed an adaptive mechanism to tolerate hypothiocyanous acid

Hypothiocyanite is the anion SCN�� and the conjugate base of hypothiocyanous acid (HOSCN). It is an organic compound part of the thiocyanates as it contains the functional group SCN. It is formed when an oxygen is singly bonded to the thiocyan ...

(HOSCN), a potent oxidant produced by the human immune system. Compared to other methicillin-resistant ''S. aureus'' (MRSA

Methicillin-resistant ''Staphylococcus aureus'' (MRSA) is a group of gram-positive bacteria that are genetically distinct from other strains of ''Staphylococcus aureus''. MRSA is responsible for several difficult-to-treat infections in humans. ...

) strains and bacterial pathogens such as ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Aerobic organism, aerobic–facultative anaerobe, facultatively anaerobic, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped bacteria, bacterium that can c ...

'', ''Escherichia coli'', and ''Streptococcus pneumoniae

''Streptococcus pneumoniae'', or pneumococcus, is a Gram-positive, spherical bacteria, hemolysis (microbiology), alpha-hemolytic member of the genus ''Streptococcus''. ''S. pneumoniae'' cells are usually found in pairs (diplococci) and do not f ...

'', ''S. aureus'' exhibits greater resistance to HOSCN.

This resistance is linked to the ''merA'' gene, which encodes a flavoprotein disulfide reductase (FDR) enzyme. ''S. aureus'' MerA shares similarities with HOSCN reductases from other bacteria, including ''S. pneumoniae'' (50% sequence identity

In bioinformatics, a sequence alignment is a way of arranging the sequences of DNA, RNA, or protein to identify regions of similarity that may be a consequence of functional, structural, or evolutionary relationships between the sequences. Align ...

, 66% positives) and RclA in ''E. coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus ''Escherichia'' that is commonly foun ...

'' (50% sequence identity, 65% positives). These enzymes play a crucial role in oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal ...

defense by using NADPH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate, abbreviated NADP or, in older notation, TPN (triphosphopyridine nucleotide), is a cofactor used in anabolic reactions, such as the Calvin cycle and lipid and nucleic acid syntheses, which require N ...

as a cofactor to reduce disulfide bonds

In chemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) is a compound containing a functional group or the anion. The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and usually derived from two thiol groups.

In in ...

, thereby mitigating the oxidative damage

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal r ...

caused by HOSCN. This mechanism enhances ''S. aureus'' survival within the host by counteracting the immune system’s oxidative attack.

Functional characterization of MerA has revealed that the amino acid residue Cys43 (C43) is essential for its enzymatic activity against HOSCN. Additionally, the expression of ''merA'' in ''S. aureus'' is regulated by the ''hypR'' gene, a transcriptional suppressor that modulates the bacterial response to oxidative stress.

Classical diagnosis

Gram stain

Gram stain (Gram staining or Gram's method), is a method of staining used to classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. It may also be used to diagnose a fungal infection. The name comes ...

is first performed to guide the way, which should show typical Gram-positive

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

The Gram stain is ...

bacteria, cocci, in clusters. Second, the isolate is cultured on mannitol salt agar, which is a selective medium with 7.5% NaCl

Sodium chloride , commonly known as edible salt, is an ionic compound with the chemical formula NaCl, representing a 1:1 ratio of sodium and chloride ions. It is transparent or translucent, brittle, hygroscopic, and occurs as the mineral hali ...

that allows ''S. aureus'' to grow, producing yellow-colored colonies as a result of mannitol