Somalis on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Somali people (, Wadaad: ,

The Somali people (, Wadaad: ,

The origin of the Somali people which was previously theorized to have been from Southern

The origin of the Somali people which was previously theorized to have been from Southern  According to most scholars, the ancient

According to most scholars, the ancient

by James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526 The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the Achaemenid emperor

In the late 19th century, after the

In the late 19th century, after the

*

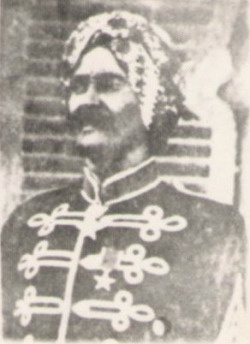

* The Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-1700s and rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly dismantled in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor Osman Mahamuud and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded the Sultanate of Hobyo in 1878. Initially Kenadid wanted to seize control of the neighbouring Sultanate. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavour, and was eventually forced into exile in

Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-1700s and rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly dismantled in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor Osman Mahamuud and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded the Sultanate of Hobyo in 1878. Initially Kenadid wanted to seize control of the neighbouring Sultanate. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavour, and was eventually forced into exile in  In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian

In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian  The Italian Somalis, descendants of Italian colonists and Somali girls were nearly 50,000 in 1940 and were concentrated in the capital

The Italian Somalis, descendants of Italian colonists and Somali girls were nearly 50,000 in 1940 and were concentrated in the capital

countrystudies.us

/ref> Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,Federal Research Division, ''Somalia: A Country Study'', (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p.38 the British ceded official control of the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was brought under British protection via treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the

According to data from the

According to data from the

*N.B. ~60% of 774,389 total pop.

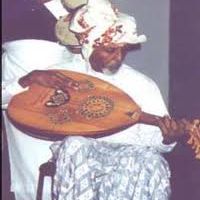

Somali music is a traditional and contemporary art form that plays an important role in cultural expression and social communication. Most Somali songs are pentatonic. That is, they only use five pitches per

Somali music is a traditional and contemporary art form that plays an important role in cultural expression and social communication. Most Somali songs are pentatonic. That is, they only use five pitches per

Somali cinema developed out of the country's strong oral storytelling traditions, with the first feature-length films and film festivals appearing in the early 1960s, soon after Somalia gained independence. The establishment of the Somali Film Agency (SFA) in 1975 marked a key turning point, leading to a period of rapid growth in the national film sector. This era saw the emergence of influential figures such as Hassan Sheikh Mumin, a prominent playwright and composer whose play ''Shabeel Naagood'' (1965) became a cornerstone of Somali literature and theater. The work, later translated into English as ''Leopard Among the Women'', explores themes such as gender roles, education, and societal change. Although the issues it describes were later to some degree redressed, the work remains a mainstay of Somali literature. Mumin composed both the play itself and the music used in it. The piece is regularly featured in various school curricula, including

Somali cinema developed out of the country's strong oral storytelling traditions, with the first feature-length films and film festivals appearing in the early 1960s, soon after Somalia gained independence. The establishment of the Somali Film Agency (SFA) in 1975 marked a key turning point, leading to a period of rapid growth in the national film sector. This era saw the emergence of influential figures such as Hassan Sheikh Mumin, a prominent playwright and composer whose play ''Shabeel Naagood'' (1965) became a cornerstone of Somali literature and theater. The work, later translated into English as ''Leopard Among the Women'', explores themes such as gender roles, education, and societal change. Although the issues it describes were later to some degree redressed, the work remains a mainstay of Somali literature. Mumin composed both the play itself and the music used in it. The piece is regularly featured in various school curricula, including

Hijab and Shayla, a Somali women typically wear the hijab (headscarf), often paired with a long shawl (shayla) referred to as ''shaash'' or jilbab for added modesty. Traditional Arabian garb, such as the jilbab and abaya, is also commonly worn.

* Garbasaar, a large, colorful shawl used to wrap the upper body or head, often used for decoration or to shield from the sun.

* Jewelery, Somali women have a long tradition of wearing

Hijab and Shayla, a Somali women typically wear the hijab (headscarf), often paired with a long shawl (shayla) referred to as ''shaash'' or jilbab for added modesty. Traditional Arabian garb, such as the jilbab and abaya, is also commonly worn.

* Garbasaar, a large, colorful shawl used to wrap the upper body or head, often used for decoration or to shield from the sun.

* Jewelery, Somali women have a long tradition of wearing

Sports play an important role in Somali society, with football being the most popular and widely followed sport. The main domestic competitions include the Somalia League and Somalia Cup, while the national team, known as the Ocean Stars, represents the country in international tournaments. The team is multi ethnic.

Sports play an important role in Somali society, with football being the most popular and widely followed sport. The main domestic competitions include the Somalia League and Somalia Cup, while the national team, known as the Ocean Stars, represents the country in international tournaments. The team is multi ethnic.

Somalis for centuries have practiced a form of

Somalis for centuries have practiced a form of

MtDNA variation in North, East, and Central African populations gives clues to a possible back-migration from the Middle East

, Program of the Seventy-Fourth Annual Meeting of the American Association of Physical Anthropologists (2005) This mitochondrial clade is common among Ethiopians and North Africans, particularly Egyptians and Algerians. M1 is believed to have originated in Asia, where its parent M clade represents the majority of mtDNA lineages.

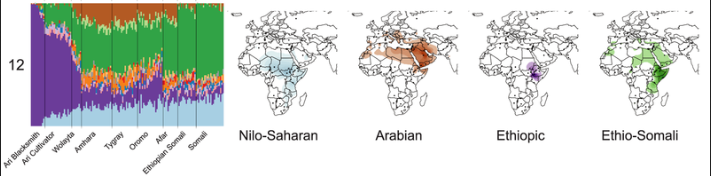

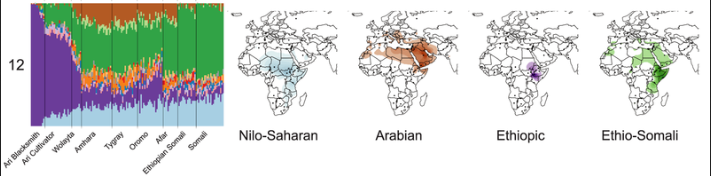

Research shows that Somalis have a mixture of a type of native African ancestry unique and autochthonous to the

Research shows that Somalis have a mixture of a type of native African ancestry unique and autochthonous to the

The scholarly term for research concerning Somalis and Greater Somalia is Somali studies. It consists of several disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, linguistics, historiography and archaeology. The field draws from old Somali literature, Somali chronicles, records and oral literature, in addition to written accounts and traditions about Somalis from explorers and geographers in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East. Since 1980, prominent ''Somalist'' scholars from around the world have also gathered annually to hold the International Congress of Somali Studies.

The scholarly term for research concerning Somalis and Greater Somalia is Somali studies. It consists of several disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, linguistics, historiography and archaeology. The field draws from old Somali literature, Somali chronicles, records and oral literature, in addition to written accounts and traditions about Somalis from explorers and geographers in the Horn of Africa and the Middle East. Since 1980, prominent ''Somalist'' scholars from around the world have also gathered annually to hold the International Congress of Somali Studies.

Ethnologue population estimates for Somali speakers

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Somali People Cushitic-speaking peoples Indigenous peoples of East Africa Ethnic Somali people, Ethnic groups in Djibouti Ethnic groups in Ethiopia Ethnic groups in Kenya Ethnic groups in Somalia, Muslim communities in Africa Pastoralists Female genital mutilation

The Somali people (, Wadaad: ,

The Somali people (, Wadaad: , Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

: ) are a Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As of 2 ...

ethnic group

An ethnicity or ethnic group is a group of people with shared attributes, which they collectively believe to have, and long-term endogamy. Ethnicities share attributes like language, culture, common sets of ancestry, traditions, society, re ...

and nation

A nation is a type of social organization where a collective Identity (social science), identity, a national identity, has emerged from a combination of shared features across a given population, such as language, history, ethnicity, culture, t ...

native to the Somali Peninsula

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and Geopolitics, geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Pr ...

. who share a common ancestry, culture and history.

The East Cushitic Somali language

Somali is an Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language belonging to the Cushitic languages, Cushitic branch, primarily spoken by the Somalis, Somali people, native to Greater Somalia. It is an official language in Somalia, Somaliland, and Ethio ...

is the shared mother tongue of ethnic Somalis, which is part of the Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As of 2 ...

branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are predominantly Sunni Muslim

Sunni Islam is the largest branch of Islam and the largest religious denomination in the world. It holds that Muhammad did not appoint any successor and that his closest companion Abu Bakr () rightfully succeeded him as the caliph of the Musli ...

.Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, ''Culture and Customs of Somalia'', (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.1 Forming one of the largest ethnic groups on the continent, they cover one of the most expansive landmasses by a single ethnic group in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

.

According to most scholars, the ancient Land of Punt

The Land of Punt (Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pwnt#Egyptian, pwnt''; alternate Egyptian language#Egyptological pronunciation, Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') ) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. ...

and its native inhabitants formed part of the ethnogenesis of the Somali people. This ancient historical kingdom is where a great portion of their cultural traditions and ancestry are said to derive from.Egypt: 3000 Years of Civilization Brought to Life By Christine El MahdyAncient perspectives on Egypt By Roger Matthews, Cornelia Roemer, University College, London.Africa's legacies of urbanization: unfolding saga of a continent By Stefan GoodwinCivilizations: Culture, Ambition, and the Transformation of Nature By Felipe Armesto Fernandez Somalis and their country have long been identified with the term ''Barbar'' (or )—12th-century geographer al-Idrisi

Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Idrisi al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti, or simply al-Idrisi (; ; 1100–1165), was an Arab Muslim geographer and cartographer who served in the court of King Roger II at Palermo, Sicily. Muhammad al-Idrisi was born in C ...

, for example, identified the Somali Peninsula as ''Barbara'', and classical sources from the Greeks and Romans similarly refer to the region as the second ''Barbaria''.

Somalis share many historical and cultural traits with other Cushitic peoples, especially with Lowland East Cushitic people, specifically the Afar and the Saho. Ethnic Somalis are principally concentrated in Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

(around 17.6 million), Somaliland

Somaliland, officially the Republic of Somaliland, is an List of states with limited recognition, unrecognised country in the Horn of Africa. It is located in the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden and bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, E ...

(5.7 million), Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

(4.6 million), Kenya

Kenya, officially the Republic of Kenya, is a country located in East Africa. With an estimated population of more than 52.4 million as of mid-2024, Kenya is the 27th-most-populous country in the world and the 7th most populous in Africa. ...

(2.8 million), and Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

(586,000). Somali diasporas are also found in parts of the Middle East

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

, North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

, Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

, African Great Lakes

The African Great Lakes (; ) are a series of lakes constituting the part of the Rift Valley lakes in and around the East African Rift. The series includes Lake Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world by area; Lake Tangan ...

region, Southern Africa

Southern Africa is the southernmost region of Africa. No definition is agreed upon, but some groupings include the United Nations geoscheme for Africa, United Nations geoscheme, the intergovernmental Southern African Development Community, and ...

and Oceania

Oceania ( , ) is a region, geographical region including Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Outside of the English-speaking world, Oceania is generally considered a continent, while Mainland Australia is regarded as its co ...

.

Etymology

Samaale

Samaale, also spelled Samali or Samale () is traditionally considered to be the common forefather of several major Somali clans and their respective sub-clans. His name is the source of the ethnonym ''Somali''..

As the purported ancestor of most ...

, the legendary common ancestor of several Somali clans, is generally regarded as the source of the ethnonym

An ethnonym () is a name applied to a given ethnic group. Ethnonyms can be divided into two categories: exonyms (whose name of the ethnic group has been created by another group of people) and autonyms, or endonyms (whose name is created and used ...

''Somali''. One other theory is that the name is held to be derived from the words and , which together mean "go and milk". This interpretation differs depending on region, with northern Somalis implying it refers to camel's milk,Who Cares about Somalia: Hassan's Ordeal; Reflections on a Nation's Future, By Hassan Ali Jama, page 92 while southern Somalis use the transliteration which refers to cow's milk. This is a reference to the ubiquitous pastoralism

Pastoralism is a form of animal husbandry where domesticated animals (known as "livestock") are released onto large vegetated outdoor lands (pastures) for grazing, historically by nomadic people who moved around with their herds. The anim ...

of the Somali people. Another plausible etymology

Etymology ( ) is the study of the origin and evolution of words—including their constituent units of sound and meaning—across time. In the 21st century a subfield within linguistics, etymology has become a more rigorously scientific study. ...

proposes that the term ''Somali'' is derived from the Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

word for ''wealthy'' (), referring to Somali riches in livestock. Alternatively, the ethnonym is believed to have been derived from the Automoli (Asmach), a group of warriors from ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

described by Herodotus

Herodotus (; BC) was a Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus (now Bodrum, Turkey), under Persian control in the 5th century BC, and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria, Italy. He wrote the '' Histori ...

. ''Asmach'' is thought to have been their Egyptian

''Egyptian'' describes something of, from, or related to Egypt.

Egyptian or Egyptians may refer to:

Nations and ethnic groups

* Egyptians, a national group in North Africa

** Egyptian culture, a complex and stable culture with thousands of year ...

name, with ''Automoli'' being a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

derivative of the Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

word (meaning 'on the left hand side'). However, historian Mohamed A. Rirash maintains that the most accurate etymology of the ethnonym derives from the compound term —with meaning 'to herd' and referring to 'livestock'—initially serving as an occupational label for Somali pastoralists before evolving into the collective name for all ethnic Somalis.

A Tang Chinese document from the 9th century CE referred to the northern Somalia coast—which was then part of a broader region in Northeast Africa

Northeast Africa, or Northeastern Africa, or Northern East Africa as it was known in the past, encompasses the countries of Africa situated in and around the Red Sea. The region is intermediate between North Africa and East Africa, and encompasses ...

known as Barbaria, in reference to the area's Barbar (Cushitic

The Cushitic languages are a branch of the Afroasiatic language family. They are spoken primarily in the Horn of Africa, with minorities speaking Cushitic languages to the north in Egypt and Sudan, and to the south in Kenya and Tanzania. As of 2 ...

) inhabitantsDavid D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, ''Somalia: Nation in Search of a State'', (Westview Press: 1987), p. 5.—as ''Po-pa-li''.Nagendra Kr Singh, ''International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties'', (Anmol Publications PVT. LTD., 2002), p. 524.

The first clear written reference of the sobriquet

A sobriquet ( ) is a descriptive nickname, sometimes assumed, but often given by another. A sobriquet is distinct from a pseudonym in that it is typically a familiar name used in place of a real name without the need for explanation; it may beco ...

''Somali'' dates back to the early 15th century CE during the reign of Ethiopian Emperor Yeshaq I who had one of his court officials compose a hymn

A hymn is a type of song, and partially synonymous with devotional song, specifically written for the purpose of adoration or prayer, and typically addressed to a deity or deities, or to a prominent figure or personification. The word ''hymn'' d ...

celebrating a military victory over the Sultanate of Ifat. ''Simur'' was also an ancient Harari alias for the Somali people.

Somalis overwhelmingly prefer the demonym

A demonym (; ) or 'gentilic' () is a word that identifies a group of people ( inhabitants, residents, natives) in relation to a particular place. Demonyms are usually derived from the name of the place ( hamlet, village, town, city, region, ...

''Somali'' over the incorrect ''Somalian'' since the former is an endonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

, while the latter is an exonym

An endonym (also known as autonym ) is a common, name for a group of people, individual person, geographical place, language, or dialect, meaning that it is used inside a particular group or linguistic community to identify or designate them ...

with double suffixes. The hypernym

Hypernymy and hyponymy are the semantic relations between a generic term (''hypernym'') and a more specific term (''hyponym''). The hypernym is also called a ''supertype'', ''umbrella term'', or ''blanket term''. The hyponym names a subtype of ...

of the term ''Somali'' from a geopolitical sense is '' Horner'' and from an ethnic sense, it is '' Cushite''.

History

The origin of the Somali people which was previously theorized to have been from Southern

The origin of the Somali people which was previously theorized to have been from Southern Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, is a landlocked country located in the Horn of Africa region of East Africa. It shares borders with Eritrea to the north, Djibouti to the northeast, Somalia to the east, Ken ...

since 1000 BC or from the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

in the eleventh century has now been overturned by newer archeological and linguistic studies which puts the original homeland of the Somali people in Somaliland

Somaliland, officially the Republic of Somaliland, is an List of states with limited recognition, unrecognised country in the Horn of Africa. It is located in the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden and bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, E ...

region, which concludes that the Somalis are the indigenous inhabitants of the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

for the last 7000 years.

Ancient rock paintings, which date back 5000 years (estimated), have been found in Somaliland

Somaliland, officially the Republic of Somaliland, is an List of states with limited recognition, unrecognised country in the Horn of Africa. It is located in the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden and bordered by Djibouti to the northwest, E ...

region. These engravings depict early life in the territory. The most famous of these is the Laas Geel complex. It contains some of the earliest known rock art

In archaeology, rock arts are human-made markings placed on natural surfaces, typically vertical stone surfaces. A high proportion of surviving historic and prehistoric rock art is found in caves or partly enclosed rock shelters; this type al ...

on the African continent and features many elaborate pastoralist sketches of animal and human figures. In other places, such as the Dhambalin region, a depiction of a man on a horse is postulated as being one of the earliest known examples of a mounted huntsman.

Inscriptions have been found beneath many of the rock paintings, but archaeologist

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of Artifact (archaeology), artifacts, architecture, biofact (archaeology), biofacts or ecofacts, ...

s have so far been unable to decipher this form of ancient writing. During the Stone Age

The Stone Age was a broad prehistory, prehistoric period during which Rock (geology), stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended b ...

, the Doian and Hargeisa

Hargeisa ( ; ; ) is the capital and largest city of the Republic of Somaliland, a ''List of states with limited recognition, de facto'' sovereign state in the Horn of Africa, still considered internationally to be part of Somalia. It is also th ...

n cultures flourished here with their respective industries and factories.

The oldest evidence of burial customs in the Horn of Africa comes from cemeteries

A cemetery, burial ground, gravesite, graveyard, or a green space called a memorial park or memorial garden, is a place where the remains of many dead people are buried or otherwise entombed. The word ''cemetery'' (from Greek ) implies th ...

in Somalia dating back to 4th millennium BC

File:4th millennium BC montage.jpg, 400x400px, From top left clockwise: The Temple of Ġgantija, one of the oldest freestanding structures in the world; Warka Vase; Bronocice pot with one of the earliest known depictions of a wheeled vehicle; Kish ...

. The stone implements from the ''Jalelo'' site

Site most often refers to:

* Archaeological site

* Campsite, a place used for overnight stay in an outdoor area

* Construction site

* Location, a point or an area on the Earth's surface or elsewhere

* Website, a set of related web pages, typical ...

in Somalia are said to be the most important link in evidence of the universality in palaeolithic

The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic ( years ago) ( ), also called the Old Stone Age (), is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehist ...

times between the East

East is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from west and is the direction from which the Sun rises on the Earth.

Etymology

As in other languages, the word is formed from the fact that ea ...

and the West

West is one of the four cardinal directions or points of the compass. It is the opposite direction from east and is the direction in which the Sun sets on the Earth.

Etymology

The word "west" is a Germanic word passed into some Romance langu ...

.

In antiquity, the ancestors of the Somali people were an important link in the Horn of Africa connecting the region's commerce with the rest of the ancient world. Somali sailors and merchants were the main suppliers of frankincense

Frankincense, also known as olibanum (), is an Aroma compound, aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus ''Boswellia'' in the family (biology), family Burseraceae. The word is from Old French ('high-quality in ...

, myrrh

Myrrh (; from an unidentified ancient Semitic language, see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a few small, thorny tree species of the '' Commiphora'' genus, belonging to the Burseraceae family. Myrrh resin has been used ...

and spice

In the culinary arts, a spice is any seed, fruit, root, Bark (botany), bark, or other plant substance in a form primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of pl ...

s, items which were considered valuable luxuries by the Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egypt () was a cradle of civilization concentrated along the lower reaches of the Nile River in Northeast Africa. It emerged from prehistoric Egypt around 3150BC (according to conventional Egyptian chronology), when Upper and Lower E ...

ians, Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns, Mycenaeans and Babylon

Babylon ( ) was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern-day Hillah, Iraq, about south of modern-day Baghdad. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian-s ...

ians. According to most scholars, the ancient

According to most scholars, the ancient Land of Punt

The Land of Punt (Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pwnt#Egyptian, pwnt''; alternate Egyptian language#Egyptological pronunciation, Egyptological readings ''Pwene''(''t'') ) was an ancient kingdom known from Ancient Egyptian trade records. ...

and its native inhabitants formed part of the ethnogenesis

Ethnogenesis (; ) is the formation and development of an ethnic group. This can originate by group self-identification or by outside identification.

The term ''ethnogenesis'' was originally a mid-19th-century neologism that was later introduce ...

of the Somali people. The ancient Puntites were a nation of people that had close relations with Pharaonic Egypt during the times of Pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian language, Egyptian: ''wikt:pr ꜥꜣ, pr ꜥꜣ''; Meroitic language, Meroitic: 𐦲𐦤𐦧, ; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') was the title of the monarch of ancient Egypt from the First Dynasty of Egypt, First Dynasty ( ...

Sahure

Sahure (also Sahura, meaning "He who is close to Ra, Re"; died 2477 BC) was a pharaoh, king of ancient Egypt and the second ruler of the Fifth dynasty of Egypt, Fifth Dynasty ( – BC). He reigned for around 13 years in the early 25th&nbs ...

and Queen

Queen most commonly refers to:

* Queen regnant, a female monarch of a kingdom

* Queen consort, the wife of a reigning king

* Queen (band), a British rock band

Queen or QUEEN may also refer to:

Monarchy

* Queen dowager, the widow of a king

* Q ...

Hatshepsut

Hatshepsut ( ; BC) was the sixth pharaoh of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt, Egypt, ruling first as regent, then as queen regnant from until (Low Chronology) and the Great Royal Wife of Pharaoh Thutmose II. She was Egypt's second c ...

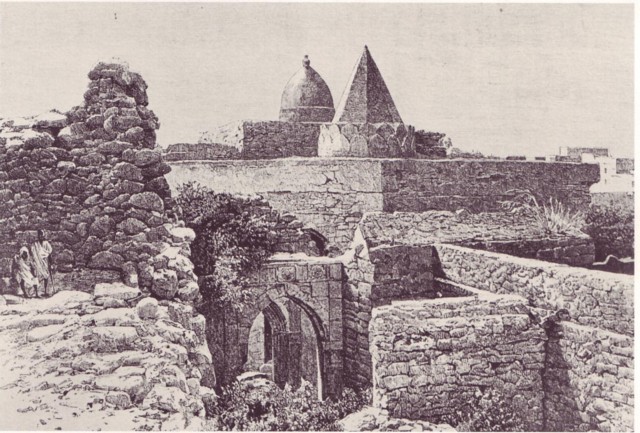

. The pyramidal structures, temples and ancient houses of dressed stone littered around Somalia may date from this period.Man, God and Civilization pg 216

In classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

, the Macrobians, who may have been ancestral to the Automoli or ancient Somalis, established a powerful tribal kingdom that ruled large parts of modern Somalia

Somalia, officially the Federal Republic of Somalia, is the easternmost country in continental Africa. The country is located in the Horn of Africa and is bordered by Ethiopia to the west, Djibouti to the northwest, Kenya to the southwest, th ...

. They were reputed for their longevity and wealth, and were said to be the "tallest and handsomest of all men".The Geography of Herodotus: Illustrated from Modern Researches and Discoveriesby James Talboys Wheeler, pg 1xvi, 315, 526 The Macrobians were warrior herders and seafarers. According to Herodotus' account, the Achaemenid emperor

Cambyses II

Cambyses II () was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire, reigning 530 to 522 BCE. He was the son of and successor to Cyrus the Great (); his mother was Cassandane. His relatively brief reign was marked by his conquests in North Afric ...

, upon his conquest of Egypt in 525 BCE, sent ambassadors to Macrobia, bringing luxury gifts for the Macrobian king to entice his submission. The Macrobian ruler, who was elected based on his stature and beauty, replied instead with a challenge for his Persian counterpart in the form of an unstrung bow: if the Persians could manage to draw it, they would have the right to invade his country; but until then, they should thank the gods that the Macrobians never decided to invade their empire.John Kitto, James Taylor, ''The popular cyclopædia of Biblical literature: condensed from the larger work'', (Gould and Lincoln: 1856), p.302. The Macrobians were a regional power reputed for their advanced architecture and gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

wealth, which was so plentiful that they shackled their prisoners in golden chains.

Several ancient city-states, such as Opone, Essina, Sarapion, Nikon

(, ; ) is a Japanese optics and photographic equipment manufacturer. Nikon's products include cameras, camera lenses, binoculars, microscopes, ophthalmic lenses, measurement instruments, rifle scopes, spotting scopes, and equipment related to S ...

, Malao, Damo and Mosylon near Cape Guardafui, which competed with the Sabaeans

Sheba, or Saba, was an ancient South Arabian kingdom that existed in Yemen from to . Its inhabitants were the Sabaeans, who, as a people, were indissociable from the kingdom itself for much of the 1st millennium BCE. Modern historians agree th ...

, Parthia

Parthia ( ''Parθava''; ''Parθaw''; ''Pahlaw'') is a historical region located in northeastern Greater Iran. It was conquered and subjugated by the empire of the Medes during the 7th century BC, was incorporated into the subsequent Achaemeni ...

ns and Axumites for the wealthy Indo-Greco-Roman

The Greco-Roman world , also Greco-Roman civilization, Greco-Roman culture or Greco-Latin culture (spelled Græco-Roman or Graeco-Roman in British English), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and co ...

trade, also flourished in Somalia.

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

was introduced to the area early on by the first Muslims of Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

fleeing prosecution during the first Hejira with Masjid al-Qiblatayn being built before the Qibla

The qibla () is the direction towards the Kaaba in the Great Mosque of Mecca, Sacred Mosque in Mecca, which is used by Muslims in various religious contexts, particularly the direction of prayer for the salah. In Islam, the Kaaba is believed to ...

h faced towards Mecca

Mecca, officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, is the capital of Mecca Province in the Hejaz region of western Saudi Arabia; it is the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red Sea, in a narrow valley above ...

. The town of Zeila

Zeila (, ), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila with the Biblical location of Havilah. Most modern schola ...

's two-mihrab

''Mihrab'' (, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "''qibla'' wall".

...

Masjid al-Qiblatayn dates to the 7th century, and is one of the oldest mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

s in Africa.

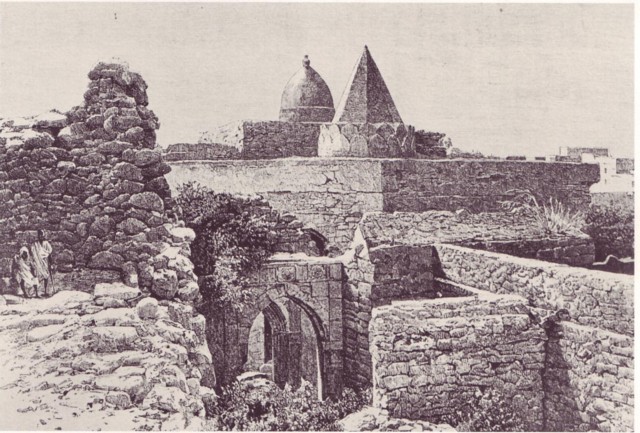

Consequently, the Somalis were some of the earliest non-Arabs that converted to Islam. The peaceful conversion of the Somali population by Somali Muslim scholars in the following centuries, the ancient city-states eventually transformed into Islamic Mogadishu

Mogadishu, locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Ocean for millennia and has ...

, Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

, Zeila

Zeila (, ), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila with the Biblical location of Havilah. Most modern schola ...

, Barawa, Hafun and Merca

Merca (, ) is the capital city of the Lower Shebelle province of Somalia, a historic port city in the region. It is located approximately to the southwest of the nation's capital Mogadishu. Merca is the traditional home territory of the Bimal c ...

, which were part of the Berberi civilization. The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the ''City of Islam'', and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries.

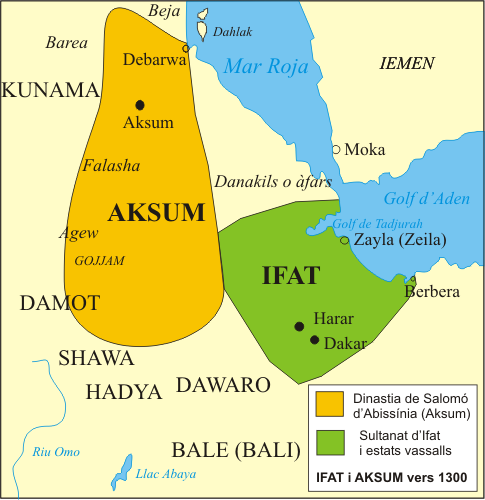

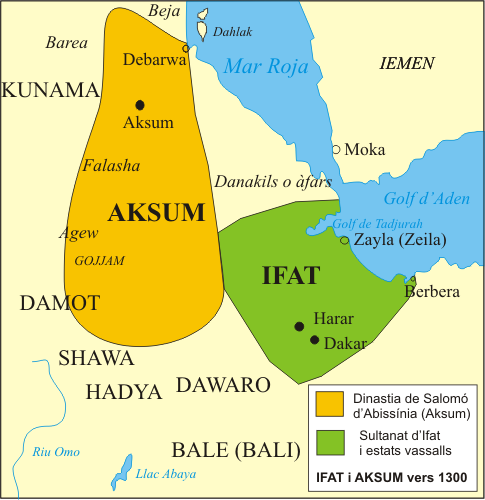

The Sultanate of Ifat, led by the Walashma dynasty

The Walashma dynasty was a medieval Muslim dynasty of the Horn of Africa founded in Ifat (historical region), Ifat (modern eastern Shewa). Founded in the 13th century, it governed the Sultanate of Ifat, Ifat and Adal Sultanate, Adal Sultanates in ...

with its capital at Zeila

Zeila (, ), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila with the Biblical location of Havilah. Most modern schola ...

, ruled over parts of what is now eastern Ethiopia, Djibouti and Somaliland. The historian al-Umari records that Ifat was situated near the Red Sea

The Red Sea is a sea inlet of the Indian Ocean, lying between Africa and Asia. Its connection to the ocean is in the south, through the Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and the Gulf of Aden. To its north lie the Sinai Peninsula, the Gulf of Aqaba, and th ...

coast, and states its size as 15 days travel by 20 days travel. Its army numbered 15,000 horsemen and 20,000 foot soldiers. Al-Umari also credits Ifat with seven "mother cities": Belqulzar, Kuljura, Shimi, Shewa, Adal, Jamme and Laboo.

In the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

, several powerful Somali empires dominated the regional trade including the Ajuran Sultanate

The Ajuran Sultanate (, ), natively referred to as Ajuuraan, and often simply Ajuran/Ajur, was a Muslims, Muslim empire in the Horn of Africa that thrived from the Late Middle Ages, late medieval and Early modern period, early modern period. F ...

, which excelled in hydraulic engineering

Hydraulic engineering as a sub-discipline of civil engineering is concerned with the flow and conveyance of fluids, principally water and sewage. One feature of these systems is the extensive use of gravity as the motive force to cause the move ...

and fortress

A fortification (also called a fort, fortress, fastness, or stronghold) is a military construction designed for the defense of territories in warfare, and is used to establish rule in a region during peacetime. The term is derived from L ...

building, the Adal Sultanate

The Adal Sultanate, also known as the Adal Empire or Barr Saʿad dīn (alt. spelling ''Adel Sultanate'', ''Adal Sultanate'') (), was a medieval Sunni Muslim empire which was located in the Horn of Africa. It was founded by Sabr ad-Din III on th ...

, whose general Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi

Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (, Harari: አሕመድ ኢብራሂም አል-ጋዚ, ; 21 July 1506 – 10 February 1543) was the Imam of the Adal Sultanate from 1527 to 1543. Commonly named Ahmed ''Gragn'' in Amharic and ''Gurey'' in Somali, ...

(Ahmed Gurey) was the first commander

Commander (commonly abbreviated as Cmdr.) is a common naval officer rank as well as a job title in many army, armies. Commander is also used as a rank or title in other formal organizations, including several police forces. In several countri ...

to use cannon warfare on the continent during Adal's conquest of the Ethiopian Empire

The Ethiopian Empire, historically known as Abyssinia or simply Ethiopia, was a sovereign state that encompassed the present-day territories of Ethiopia and Eritrea. It existed from the establishment of the Solomonic dynasty by Yekuno Amlak a ...

, and the Sultanate of the Geledi

The Sultanate of the Geledi (, ) also known as the Gobroon dynasty,Somali Sultanate: The Geledi City-state Over 150 Years - Virginia Luling (2002) Page 229 was a Somali kingdom that ruled parts of the Horn of Africa during the late-17th century ...

, whose military dominance forced governors of the Omani empire

The Omani Empire () was a maritime empire, vying with Portugal and Britain for trade and influence in the Persian Gulf and Indian Ocean. After rising as a regional power in the 18th century, the empire at its peak in the 19th century saw its i ...

north of the city of Lamu to pay tribute to the Somali Sultan Ahmed Yusuf. The Harla

The Harla, also known as Harala, Haralla were an ethnic group that once inhabited Ethiopia, Somalia, and Djibouti. They spoke the Harla language, which belonged to either the Cushitic or Semitic branches of the Afroasiatic family.

History

The ...

, an early group who inhabited parts of Somalia, Tchertcher and other areas in the Horn, also erected various tumuli

A tumulus (: tumuli) is a mound of Soil, earth and Rock (geology), stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, mounds, howes, or in Siberia and Central Asia as ''kurgans'', and may be found through ...

. These masons are believed to have been ancestral to the Somalis ("proto-Somali").

Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

was the most important port in the Horn of Africa

The Horn of Africa (HoA), also known as the Somali Peninsula, is a large peninsula and geopolitical region in East Africa.Robert Stock, ''Africa South of the Sahara, Second Edition: A Geographical Interpretation'', (The Guilford Press; 2004), ...

between the 18th–19th centuries. For centuries, Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

had extensive trade relations with several historic ports in the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

. Additionally, the Somali and Ethiopian interiors were very dependent on Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

for trade, where most of the goods for export arrived from. During the 1833 trading season, the port town swelled to over 70,000 people, and upwards of 6,000 camels laden with goods arrived from the interior within a single day. Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

was the main marketplace in the entire Somali seaboard for various goods procured from the interior, such as livestock

Livestock are the Domestication, domesticated animals that are raised in an Agriculture, agricultural setting to provide labour and produce diversified products for consumption such as meat, Egg as food, eggs, milk, fur, leather, and wool. The t ...

, coffee

Coffee is a beverage brewed from roasted, ground coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content, but decaffeinated coffee is also commercially a ...

, frankincense

Frankincense, also known as olibanum (), is an Aroma compound, aromatic resin used in incense and perfumes, obtained from trees of the genus ''Boswellia'' in the family (biology), family Burseraceae. The word is from Old French ('high-quality in ...

, myrrh

Myrrh (; from an unidentified ancient Semitic language, see '' § Etymology'') is a gum-resin extracted from a few small, thorny tree species of the '' Commiphora'' genus, belonging to the Burseraceae family. Myrrh resin has been used ...

, acacia gum, saffron

Saffron () is a spice derived from the flower of '' Crocus sativus'', commonly known as the "saffron crocus". The vivid crimson stigma and styles, called threads, are collected and dried for use mainly as a seasoning and colouring agent ...

, feathers

Feathers are epidermis (zoology), epidermal growths that form a distinctive outer covering, or plumage, on both Bird, avian (bird) and some non-avian dinosaurs and other archosaurs. They are the most complex integumentary structures found in ...

, ghee

Ghee is a type of clarified butter, originating from South Asia. It is commonly used for cooking, as a Traditional medicine of India, traditional medicine, and for Hinduism, Hindu religious rituals.

Description

Ghee is typically prepared by ...

, hide (skin)

A hide or skin is an animal skin treated for human use.

The word "hide" is related to the German word , which means skin. The industry defines hides as "skins" of large animals ''e.g''. cow, buffalo; while skins refer to "skins" of smaller animals ...

, gold

Gold is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol Au (from Latin ) and atomic number 79. In its pure form, it is a brightness, bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile metal. Chemically, gold is a transition metal ...

and ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and Tooth, teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mamm ...

. Historically, the port of Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

was controlled indigenously between the mercantile

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cred ...

Reer Ahmed Nur and Reer Yunis Nuh sub-clans of the Habar Awal.

According to a trade journal published in 1856, Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

was described as "the freest port in the world, and the most important trading place on the whole Arabian Gulf.":

As a tributary of Mocha, which in turn was part of the Ottoman possessions in Western Arabia, the port of Zeila

Zeila (, ), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila with the Biblical location of Havilah. Most modern schola ...

had seen several men placed as governors over the years. The Ottomans based in Yemen held nominal authority of Zeila when Sharmarke Ali Saleh, who was a successful and ambitious Somali merchant, purchased the rights of the town from the Ottoman governor of Mocha and Hodeida.

Allee Shurmalkee li Sharmarkehas since my visit either seized or purchased this town, and hoisted independent colours upon its walls; but as I know little or nothing save the mere fact of its possession by that Soumaulee chief, and as this change occurred whilst I was in Abyssinia, I shall not say anything more upon the subject.However, the previous governor was not eager to relinquish his control of Zeila. Hence in 1841, Sharmarke chartered two dhows (ships) along with fifty Somali

Matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of flammable cord or twine that is in contact with the gunpowder through a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or Tri ...

men and two cannons

A cannon is a large-caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder during t ...

to target Zeila

Zeila (, ), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila with the Biblical location of Havilah. Most modern schola ...

and depose its Arab Governor, Syed Mohammed Al Barr. Sharmarke initially directed his cannons at the city walls which frightened Al Barr's followers and caused them to abandon their posts and succeeded Al Barr as the ruler of Zeila. Sharmarke's governorship had an instant effect on the city, as he maneuvered to monopolize as much of the regional trade as possible, with his sights set as far as Harar

Harar (; Harari language, Harari: ሀረር / ; ; ; ), known historically by the indigenous as Harar-Gey or simply Gey (Harari: ጌይ, ݘٛىيْ, ''Gēy'', ), is a List of cities with defensive walls, walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is al ...

and the Ogaden

Ogaden (pronounced and often spelled ''Ogadēn''; , ) is one of the historical names used for the modern Somali Region. It is also natively referred to as Soomaali Galbeed (). The region forms the eastern portion of Ethiopia and borders Somalia ...

.

In 1845, Sharmarke deployed a few matchlock men to wrest control of neighboring Berbera from that town's then feuding Somali local authorities. Sharmarke's influence was not limited to the Somali coast as he had allies and influence in the interior of the Somali country, the Danakil coast and even further afield in Abyssinia. Among his allies were the Kings of Shewa. When there was tension between the Amir of Harar Abu Bakr II ibn `Abd al-Munan and Sharmarke, as a result of the Amir arresting one of his agents in Harar

Harar (; Harari language, Harari: ሀረር / ; ; ; ), known historically by the indigenous as Harar-Gey or simply Gey (Harari: ጌይ, ݘٛىيْ, ''Gēy'', ), is a List of cities with defensive walls, walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is al ...

, Sharmarke persuaded the son of Sahle Selassie, ruler of Shewa, to imprison on his behalf about 300 citizens of Harar then resident in Shewa, for a length of two years.

In the late 19th century, after the

In the late 19th century, after the Berlin Conference

The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885 was a meeting of colonial powers that concluded with the signing of the General Act of Berlin,

had ended, the Scramble for Africa

The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, conquest, and colonialism, colonisation of most of Africa by seven Western European powers driven by the Second Industrial Revolution during the late 19th century and early 20th century in the era of ...

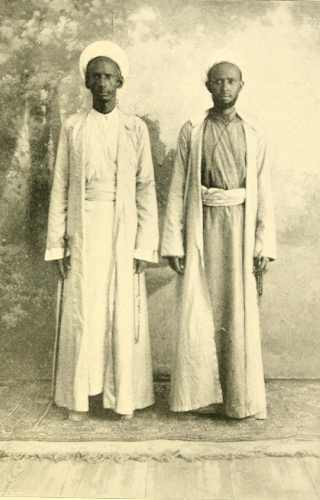

reached the Horn of Africa. Increasing foreign influence in the region culminated in the creation of the first ''Darawiish,'' an armed resistance movement calling for the independence from the European powers.**

* The

Dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from ) in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity (''tariqah''), or more narrowly to a religious mendicant, who chose or accepted material poverty. The latter usage is found particularly in Persi ...

had their leaders, Mohammed Abdullah Hassan

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monotheistic teachings of Adam, Noah, Abraham, Moses, ...

, Haji Sudi and Sultan Nur Ahmed Aman, who sought a state in the Nugaal and began one of the longest African conflicts in modern history.

The news of the incident that sparked the 21 year long Dervish rebellion, according to the consul-general James Hayes Sadler, was spread or as he claimed was concocted by Sultan Nur of the Habr Yunis. The incident in question was that of a group of Somali children who were converted to Christianity and adopted by the French Catholic Mission at Berbera

Berbera (; , ) is the capital of the Sahil, Somaliland, Sahil region of Somaliland and is the main sea port of the country, located approximately 160 km from the national capital, Hargeisa. Berbera is a coastal city and was the former capital of t ...

in 1899. Whether Sultan Nur experienced the incident first hand or whether he was told of it is not clear but what is known is that he propagated the incident in June 1899, precipitating the religious rebellion of the Dervishes.

The Dervish movement successfully stymied British forces four times and forced them to retreat to the coastal region. As a result of its successes against the British, the Dervish movement received support from the Ottomans

Ottoman may refer to:

* Osman I, historically known in English as "Ottoman I", founder of the Ottoman Empire

* Osman II, historically known in English as "Ottoman II"

* Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empir ...

and Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

. The Ottoman government also named Hassan Emir

Emir (; ' (), also Romanization of Arabic, transliterated as amir, is a word of Arabic language, Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocratic, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person po ...

of the Somali nation, and the German government promised to officially recognise any territories the Dervishes were to acquire.

After a quarter of a century of military successes against the British, the Dervishes were finally defeated by Britain in 1920 in part due to the successful deployment of the newly-formed Royal Air Force

The Royal Air Force (RAF) is the Air force, air and space force of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies. It was formed towards the end of the World War I, First World War on 1 April 1918, on the merger of t ...

by the British government

His Majesty's Government, abbreviated to HM Government or otherwise UK Government, is the central government, central executive authority of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland.

.

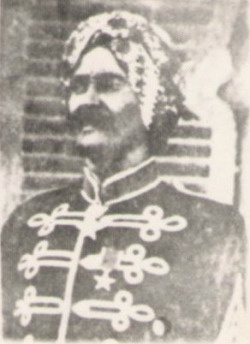

Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-1700s and rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly dismantled in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor Osman Mahamuud and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded the Sultanate of Hobyo in 1878. Initially Kenadid wanted to seize control of the neighbouring Sultanate. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavour, and was eventually forced into exile in

Majeerteen Sultanate was founded in the early-1700s and rose to prominence in the following century, under the reign of the resourceful Boqor (King) Osman Mahamuud. Helen Chapin Metz, ed., ''Somalia: a country study'', (The Division: 1993), p.10. His Kingdom controlled Bari Karkaar, Nugaaal, and also central Somalia in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The Majeerteen Sultanate maintained a robust trading network, entered into treaties with foreign powers, and exerted strong centralized authority on the domestic front.''Horn of Africa'', Volume 15, Issues 1–4, (Horn of Africa Journal: 1997), p.130.''Transformation towards a regulated economy'', (WSP Transition Programme, Somali Programme: 2000) p.62.

The Majeerteen Sultanate was nearly dismantled in the late-1800s by a power struggle between Boqor Osman Mahamuud and his ambitious cousin, Yusuf Ali Kenadid who founded the Sultanate of Hobyo in 1878. Initially Kenadid wanted to seize control of the neighbouring Sultanate. However, he was unsuccessful in this endeavour, and was eventually forced into exile in Yemen

Yemen, officially the Republic of Yemen, is a country in West Asia. Located in South Arabia, southern Arabia, it borders Saudi Arabia to Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, the north, Oman to Oman–Yemen border, the northeast, the south-eastern part ...

. Both sultanates maintained written records of their activities, which still exist.

In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian

In late 1888, Sultan Yusuf Ali Kenadid entered into a treaty with the Italian government, making his Sultanate of Hobyo an Italian protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

known as Italian Somalia

Italian Somaliland (; ; ) was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia, which was ruled in the 19th century by the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Majeerteen Sultanate in the north, and by the Hiraab Imamate an ...

. His rival Boqor Osman Mahamuud was to sign a similar agreement vis-a-vis his own Majeerteen Sultanate the following year. In signing the agreements, both rulers also hoped to exploit the rival objectives of the European imperial powers so as to more effectively assure the continued independence of their territories. The Italians, for their part, were interested in the territories mainly because of its port

A port is a maritime facility comprising one or more wharves or loading areas, where ships load and discharge cargo and passengers. Although usually situated on a sea coast or estuary, ports can also be found far inland, such as Hamburg, Manch ...

s specifically Port of Bosaso which could grant them access to the strategically important Suez Canal

The Suez Canal (; , ') is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, Indo-Mediterranean, connecting the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea through the Isthmus of Suez and dividing Africa and Asia (and by extension, the Sinai Peninsula from the rest ...

and the Gulf of Aden

The Gulf of Aden (; ) is a deepwater gulf of the Indian Ocean between Yemen to the north, the Arabian Sea to the east, Djibouti to the west, and the Guardafui Channel, the Socotra Archipelago, Puntland in Somalia and Somaliland to the south. ...

.Fitzgerald, Nina J. ''Somalia'' (New York: Nova Science, 2002), p 33 The terms of each treaty specified that Italy was to steer clear of any interference in the Sultanates' respective administrations. In return for Italian arms and an annual subsidy, the Sultans conceded to a minimum of oversight and economic concessions. The Italians also agreed to dispatch a few ambassadors to promote both the Sultanates' and their own interests. The new protectorates were thereafter managed by Vincenzo Filonardi through a chartered company

A chartered company is an association with investors or shareholders that is Incorporation (business), incorporated and granted rights (often Monopoly, exclusive rights) by royal charter (or similar instrument of government) for the purpose of ...

. An Anglo-Italian border protocol was later signed on 5 May 1894, followed by an agreement in 1906 between Cavalier Pestalozza and General Swaine acknowledging that Baran fell under the Majeerteen Sultanate's administration. With the gradual extension into northern Somalia of Italian colonial rule, both Kingdoms were eventually annexed in the early 20th century.The Majeerteen Sultanates However, unlike the southern territories, the northern sultanates were not subject to direct rule due to the earlier treaties they had signed with the Italians.

By the end of 1927, following a two-year military campaign

A military campaign is large-scale long-duration significant military strategy plan incorporating a series of interrelated military operations or battles forming a distinct part of a larger conflict often called a war. The term derives from th ...

against Somali rebels, Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

finally asserted full authority over the entirety of Italian Somaliland. In 1936, the region was integrated into Italian East Africa as the Somalia Governorate.

In urban areas, "Somalia italiana" was one of the most developed on the continent in terms of standard of living. In the late 1930s the triangle area between Mogadishu, Merca

Merca (, ) is the capital city of the Lower Shebelle province of Somalia, a historic port city in the region. It is located approximately to the southwest of the nation's capital Mogadishu. Merca is the traditional home territory of the Bimal c ...

and Villabruzzi was fully developed in agriculture (with a growing export of bananas to all western Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the Northern Hemisphere and mostly in the Eastern Hemisphere. It is bordered by the Arctic Ocean to the north, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, the Mediterranean Sea to the south, and Asia to the east ...

), and was even experiencing an initial industrial development.

The Italian Somalis, descendants of Italian colonists and Somali girls were nearly 50,000 in 1940 and were concentrated in the capital

The Italian Somalis, descendants of Italian colonists and Somali girls were nearly 50,000 in 1940 and were concentrated in the capital Mogadishu

Mogadishu, locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port connecting traders across the Indian Ocean for millennia and has ...

.

During the late 1930s the area around Mogadishu had a huge development (with new roads, railways, airport, etc..), becoming one of the best in all Africa. The British conquest of Italian Somalia in 1941 destroyed part of the infrastructure created, like the Mogadishu–Villabruzzi Railway.

Following World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Britain retained control of both British Somaliland

British Somaliland, officially the Somaliland Protectorate (), was a protectorate of the United Kingdom in modern Somaliland. It was bordered by Italian Somalia, French Somali Coast and Ethiopian Empire, Abyssinia (Italian Ethiopia from 1936 ...

and Italian Somalia

Italian Somaliland (; ; ) was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia, which was ruled in the 19th century by the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Majeerteen Sultanate in the north, and by the Hiraab Imamate an ...

as protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over ...

s. In 1945, during the Potsdam Conference, the United Nations granted Italy trusteeship of Italian Somalia, but only under close supervision and on the condition — first proposed by the Somali Youth League (SYL) and other nascent Somali political organizations, such as Hizbia Digil Mirifle Somali (HDMS) and the Somali National League (SNL) — that Somalia achieve independence within ten years.Gates, Henry Louis, ''Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience'', (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1749 British Somalia remained a protectorate of Britain until 1960.Tripodi, Paolo. ''The Colonial Legacy in Somalia'' p. 68 New York, 1999.

To the extent that Italy held the territory by UN mandate, the trusteeship provisions gave the Somalis the opportunity to gain experience in political education and self-government. These were advantages that British Somaliland, which was to be incorporated into the new Somali Republic

The Somali Republic (; ; ) was formed by the union of the Trust Territory of Somaliland (formerly Italian Somaliland) and the State of Somaliland (formerly British Somaliland). A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa Mohamud and Muhammad ...

state, did not have. Although in the 1950s British colonial officials attempted, through various administrative development efforts, to make up for past neglect, the protectorate stagnated. The disparity between the two territories in economic development and political experience would cause serious difficulties when it came time to integrate the two parts.Helen Chapin Metz, ed. Somalia: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress, 1992countrystudies.us

/ref> Meanwhile, in 1948, under pressure from their World War II allies and to the dismay of the Somalis,Federal Research Division, ''Somalia: A Country Study'', (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2004), p.38 the British ceded official control of the Haud (an important Somali grazing area that was brought under British protection via treaties with the Somalis in 1884 and 1886) and the

Ogaden

Ogaden (pronounced and often spelled ''Ogadēn''; , ) is one of the historical names used for the modern Somali Region. It is also natively referred to as Soomaali Galbeed (). The region forms the eastern portion of Ethiopia and borders Somalia ...

to Ethiopia, based on a treaty they signed in 1897 in which the British ceded Somali territory to the Ethiopian Emperor Menelik in exchange for his help against raids by Somali clans.David D. Laitin, ''Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience'', (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.73 Britain included the proviso that the Somali nomads would retain their autonomy, but Ethiopia immediately claimed sovereignty over them.Zolberg, Aristide R., et al., ''Escape from Violence: Conflict and the Refugee Crisis in the Developing World'', (Oxford University Press: 1992), p.106 This prompted an unsuccessful bid by Britain in 1956 to purchase back the Somali lands it had turned over. The British government also granted administration of the almost exclusively Somali-inhabited Northern Frontier District (NFD) to the Kenyan government despite an informal plebiscite

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a direct vote by the electorate (rather than their representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either binding (resulting in the adoption of a new policy) or adv ...

demonstrating the overwhelming desire of the region's population to join the newly formed Somali Republic.

A referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

was held in neighboring Djibouti

Djibouti, officially the Republic of Djibouti, is a country in the Horn of Africa, bordered by Somalia to the south, Ethiopia to the southwest, Eritrea in the north, and the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden to the east. The country has an area ...

(then known as French Somaliland

French Somaliland (; ; ) was a French colony in the Horn of Africa. It existed between 1884 and 1967, at which became the French Territory of the Afars and the Issas. The Republic of Djibouti is its legal successor state.

History

French Somalil ...

) in 1958, on the eve of Somalia's independence in 1960, to decide whether or not to join the Somali Republic or to remain with France. The referendum turned out in favour of a continued association with France, largely due to a combined yes vote by the sizable Afar ethnic group and resident Europeans. There was also widespread vote rigging, with the French expelling thousands of Somalis before the referendum reached the polls.Kevin Shillington, ''Encyclopedia of African history'', (CRC Press: 2005), p.360. The majority of those who voted no were Somalis who were strongly in favour of joining a united Somalia, as had been proposed by Mahmoud Harbi, Vice President of the Government Council. Harbi was killed in a plane crash two years later.Barrington, Lowell, ''After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States'', (University of Michigan Press: 2006), p.115 Djibouti finally gained its independence from France

France, officially the French Republic, is a country located primarily in Western Europe. Overseas France, Its overseas regions and territories include French Guiana in South America, Saint Pierre and Miquelon in the Atlantic Ocean#North Atlan ...

in 1977, and Hassan Gouled Aptidon

Hassan Gouled Aptidon (; ; October 15, 1916 – November 21, 2006) was the first President of Djibouti from 1977 to 1999.

Biography

He was born in the small village of Gerisa in the Lughaya district in British Somaliland. He was born into the ...

, a Somali who had campaigned for a yes vote in the referendum of 1958, eventually wound up as Djibouti's first president (1977–1991).

British Somaliland became independent on 26 June 1960 as the State of Somaliland

Somaliland, officially the State of Somaliland (), was an independent country in the territory of the present-day unilaterally declared Republic of Somaliland, which regards itself as its legal successor. It existed on the territory of former ...

, and the Trust Territory of Somalia (the former Italian Somalia) followed suit five days later. On 1 July 1960, the two territories united to form the Somali Republic

The Somali Republic (; ; ) was formed by the union of the Trust Territory of Somaliland (formerly Italian Somaliland) and the State of Somaliland (formerly British Somaliland). A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa Mohamud and Muhammad ...

, albeit within boundaries drawn up by Italy and Britain. A government was formed by Abdullahi Issa Mohamud and Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal other members of the trusteeship and protectorate governments, with Haji Bashir Ismail Yusuf as president of the Somali National Assembly, Aden Abdullah Osman Daar as the president

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

of the Somali Republic and Abdirashid Ali Shermarke as Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

(later to become president from 1967 to 1969). On 20 July 1961 and through a popular referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

, the people of Somalia ratified a new constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

, which was first drafted in 1960. The constitution was rejected by the people of Somaliland. In 1967, Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal became Prime Minister, a position to which he was appointed by Shermarke.

On 15 October 1969, while paying a visit to the northern town of Las Anod

Las Anod (; ) is the administrative capital of the Sool region, currently controlled by Khatumo State forces aligned with Somalia.

Territorial dispute

The city is disputed by Puntland and Somaliland. The former bases its claim due to the kins ...

, Somalia's then President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke was shot dead by one of his own bodyguards. His assassination was quickly followed by a military coup d'état