Signaling Pathways on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events. Proteins responsible for detecting stimuli are generally termed receptors, although in some cases the term sensor is used. The changes elicited by

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a series of molecular events. Proteins responsible for detecting stimuli are generally termed receptors, although in some cases the term sensor is used. The changes elicited by

The basis for signal transduction is the transformation of a certain stimulus into a biochemical signal. The nature of such stimuli can vary widely, ranging from extracellular cues, such as the presence of EGF, to intracellular events, such as the DNA damage resulting from replicative

The basis for signal transduction is the transformation of a certain stimulus into a biochemical signal. The nature of such stimuli can vary widely, ranging from extracellular cues, such as the presence of EGF, to intracellular events, such as the DNA damage resulting from replicative

For example, steroids act directly as transcription factor (gives slow response, as transcription factor must bind DNA, which needs to be transcribed. Produced mRNA needs to be translated, and the produced protein/peptide can undergo

For example, epidermal growth factor (EGF) binds the

Following are some major signaling pathways, demonstrating how ligands binding to their receptors can affect second messengers and eventually result in altered cellular responses.

*

Following are some major signaling pathways, demonstrating how ligands binding to their receptors can affect second messengers and eventually result in altered cellular responses.

*

Netpath - A curated resource of signal transduction pathways in humans

Signal Transduction - The Virtual Library of Biochemistry, Molecular Biology and Cell Biology

TRANSPATH(R)

- A database about signal transduction pathways

''Sciences STKE - Signal Transduction Knowledge Environment

from the journal ''Science'', published by AAAS. *

UCSD-Nature Signaling Gateway

, from Nature Publishing Group

LitInspector

- Signal transduction pathway mining in PubMed abstracts * Huaxian Chen, et al

A Cell Based Immunocytochemical Assay For Monitoring Kinase Signaling Pathways And Drug Efficacy (PDF)

Analytical Biochemistry 338 (2005) 136-142

www.Redoxsignaling.com

Signaling PAthway Database

-

Cell cycle - Homo sapiens (human)

-

Pathway Interaction Database

- National Cancer Institute, NCI

Literature-curated human signaling network, the largest human signaling network database

{{DEFAULTSORT:Signal Transduction Cell biology Cell signaling Neurochemistry

ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's el ...

binding (or signal sensing) in a receptor give rise to a biochemical cascade

A biochemical cascade, also known as a signaling cascade or signaling pathway, is a series of chemical reactions that occur within a biological cell when initiated by a stimulus. This stimulus, known as a first messenger, acts on a receptor that ...

, which is a chain of biochemical events known as a signaling pathway

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the process by which a cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellular life in both prokaryotes and eukary ...

.

When signaling pathways interact with one another they form networks, which allow cellular responses to be coordinated, often by combinatorial signaling events. At the molecular level, such responses include changes in the transcription or translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

of genes, and post-translational and conformational changes in proteins, as well as changes in their location. These molecular events are the basic mechanisms controlling cell growth

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a de ...

, proliferation, metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

and many other processes. In multicellular organisms, signal transduction pathways regulate cell communication

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the process by which a cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellular life in both prokaryotes and eukaryo ...

in a wide variety of ways.

Each component (or node) of a signaling pathway is classified according to the role it plays with respect to the initial stimulus. Ligands

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's ...

are termed ''first messengers'', while receptors are the ''signal transducers'', which then activate ''primary effectors''. Such effectors are typically proteins and are often linked to second messenger

Second messengers are intracellular signaling molecules released by the cell in response to exposure to extracellular signaling molecules—the first messengers. (Intercellular signals, a non-local form of cell signaling, encompassing both first m ...

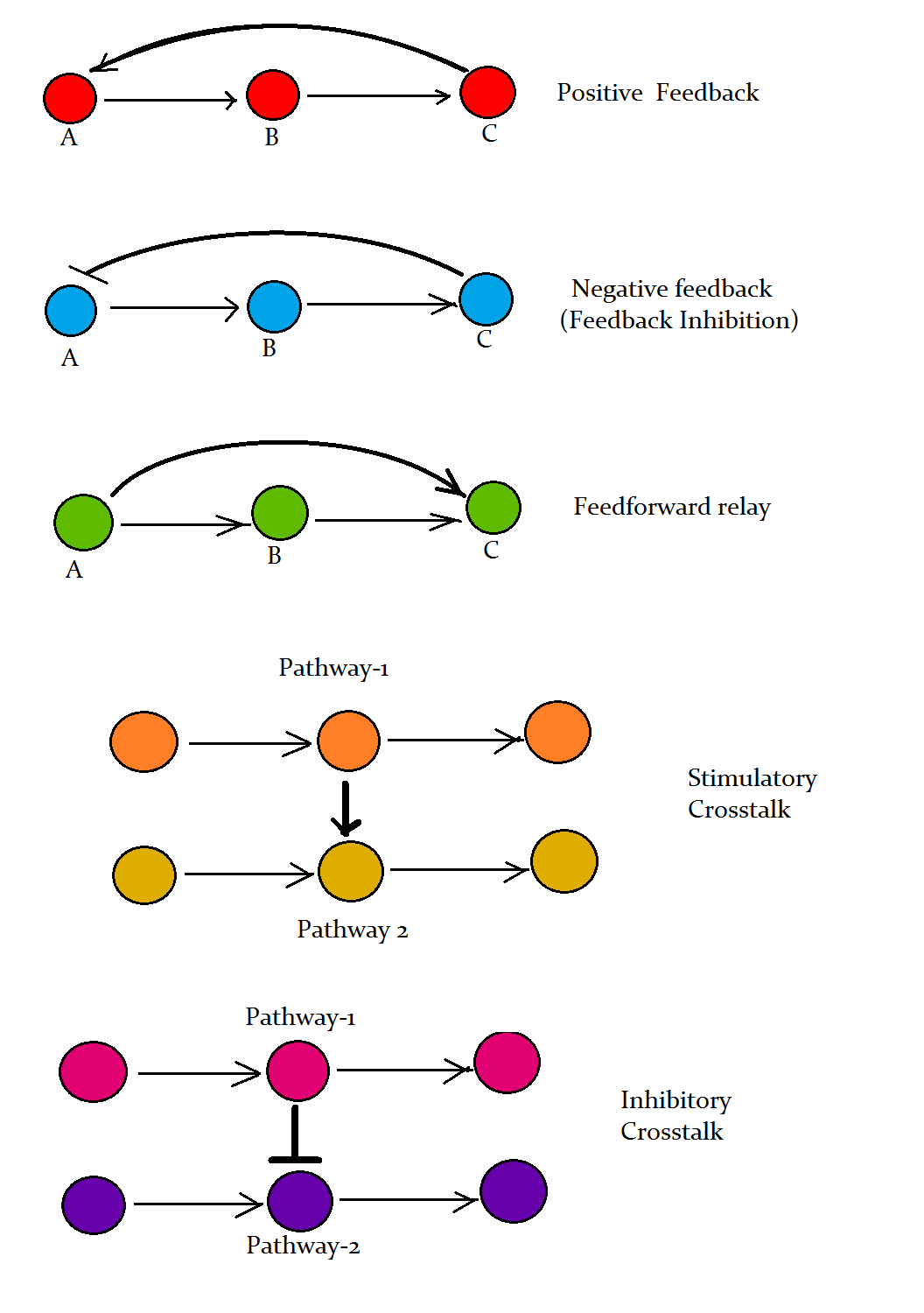

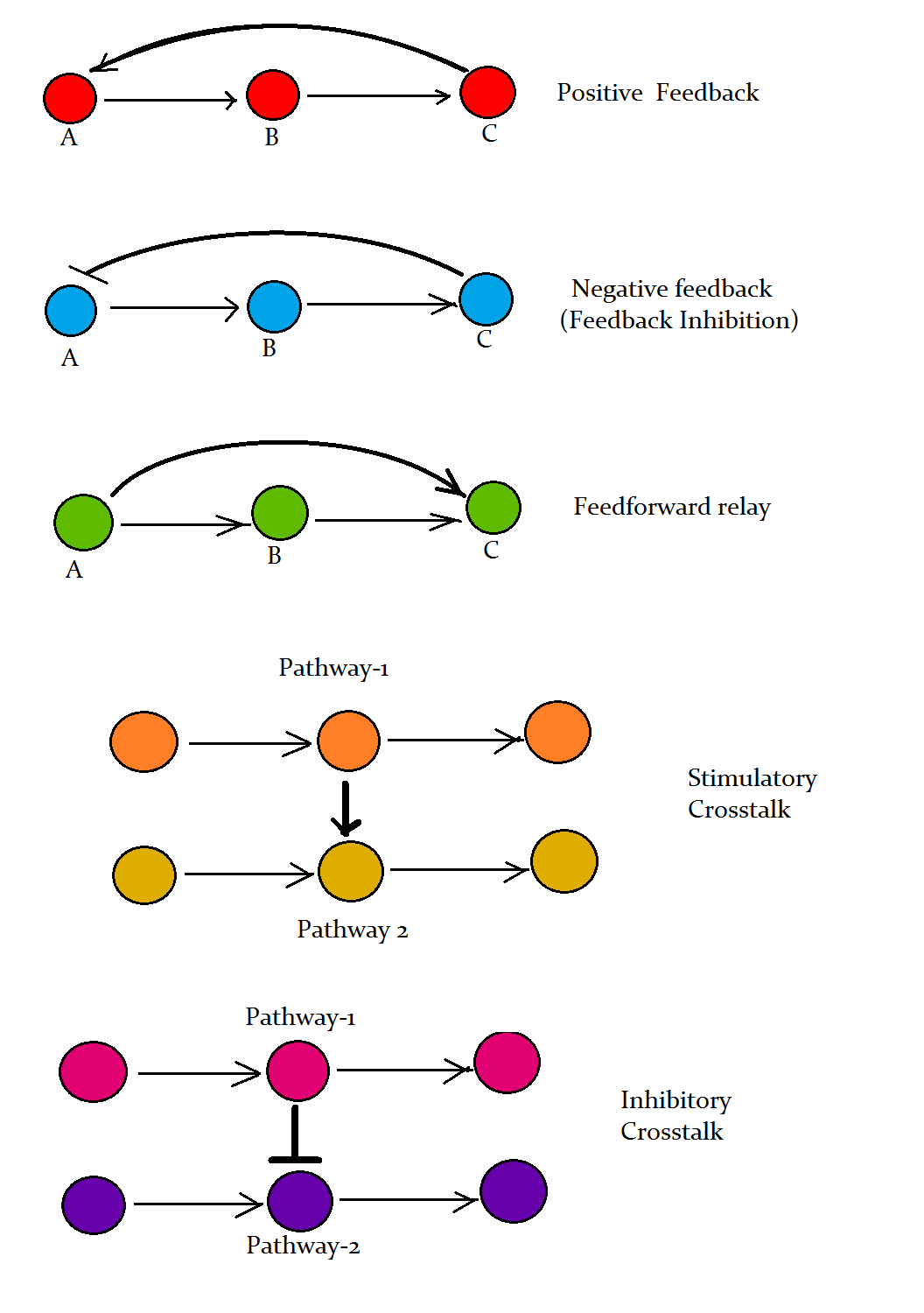

s, which can activate ''secondary effectors'', and so on. Depending on the efficiency of the nodes, a signal can be amplified (a concept known as signal gain), so that one signaling molecule can generate a response involving hundreds to millions of molecules. As with other signals, the transduction of biological signals is characterised by delay, noise, signal feedback and feedforward and interference, which can range from negligible to pathological. With the advent of computational biology

Computational biology refers to the use of techniques in computer science, data analysis, mathematical modeling and Computer simulation, computational simulations to understand biological systems and relationships. An intersection of computer sci ...

, the analysis

Analysis (: analyses) is the process of breaking a complex topic or substance into smaller parts in order to gain a better understanding of it. The technique has been applied in the study of mathematics and logic since before Aristotle (38 ...

of signaling pathways and networks has become an essential tool to understand cellular functions and disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

, including signaling rewiring mechanisms underlying responses to acquired drug resistance.

Stimuli

The basis for signal transduction is the transformation of a certain stimulus into a biochemical signal. The nature of such stimuli can vary widely, ranging from extracellular cues, such as the presence of EGF, to intracellular events, such as the DNA damage resulting from replicative

The basis for signal transduction is the transformation of a certain stimulus into a biochemical signal. The nature of such stimuli can vary widely, ranging from extracellular cues, such as the presence of EGF, to intracellular events, such as the DNA damage resulting from replicative telomere

A telomere (; ) is a region of repetitive nucleotide sequences associated with specialized proteins at the ends of linear chromosomes (see #Sequences, Sequences). Telomeres are a widespread genetic feature most commonly found in eukaryotes. In ...

attrition. Traditionally, signals that reach the central nervous system are classified as sense

A sense is a biological system used by an organism for sensation, the process of gathering information about the surroundings through the detection of Stimulus (physiology), stimuli. Although, in some cultures, five human senses were traditio ...

s. These are transmitted from neuron

A neuron (American English), neurone (British English), or nerve cell, is an membrane potential#Cell excitability, excitable cell (biology), cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network (biology), neural net ...

to neuron in a process called synaptic transmission

Neurotransmission (Latin: ''transmissio'' "passage, crossing" from ''transmittere'' "send, let through") is the process by which signaling molecules called neurotransmitters are released by the axon terminal of a neuron (the presynaptic neuron) ...

. Many other intercellular signal relay mechanisms exist in multicellular organisms, such as those that govern embryonic development.

Ligands

The majority of signal transduction pathways involve the binding of signaling molecules, known as ligands, to receptors that trigger events inside the cell. The binding of a signaling molecule with a receptor causes a change in the conformation of the receptor, known as ''receptor activation''. Most ligands are soluble molecules from the extracellular medium which bind tocell surface receptors

Cell surface receptors (membrane receptors, transmembrane receptors) are receptor (biochemistry), receptors that are embedded in the cell membrane, plasma membrane of cell (biology), cells. They act in cell signaling by receiving (binding to) ex ...

. These include growth factors

A growth factor is a naturally occurring substance capable of stimulating cell proliferation, wound healing, and occasionally cellular differentiation. Usually it is a secreted protein or a steroid hormone. Growth factors are important for regu ...

, cytokines

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

and neurotransmitters

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotransmitters are rele ...

. Components of the extracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix (ICM), is a network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide structural and bio ...

such as fibronectin

Fibronectin is a high- molecular weight (~500-~600 kDa) glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix that binds to membrane-spanning receptor proteins called integrins. Fibronectin also binds to other extracellular matrix proteins such as col ...

and hyaluronan

Hyaluronic acid (; abbreviated HA; conjugate acid, conjugate base hyaluronate), also called hyaluronan, is an anion#Anions and cations, anionic, Sulfation, nonsulfated glycosaminoglycan distributed widely throughout connective tissue, connective ...

can also bind to such receptors (integrins

Integrins are transmembrane receptors that help cell–cell and cell– extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion. Upon ligand binding, integrins activate signal transduction pathways that mediate cellular signals such as regulation of the cell cycle, ...

and CD44, respectively). In addition, some molecules such as steroid hormones are lipid-soluble and thus cross the plasma membrane to reach cytoplasmic or nuclear receptors

In the field of molecular biology, nuclear receptors are a class of proteins responsible for sensing steroid hormone, steroids, thyroid hormone, thyroid hormones, vitamins, and certain other molecules. These intracellular receptor (biochemistry) ...

. In the case of steroid hormone receptors, their stimulation leads to binding to the promoter region of steroid-responsive genes.

Not all classifications of signaling molecules take into account the molecular nature of each class member. For example, odorants belong to a wide range of molecular classes, as do neurotransmitters, which range in size from small molecules such as dopamine

Dopamine (DA, a contraction of 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine) is a neuromodulatory molecule that plays several important roles in cells. It is an organic chemical of the catecholamine and phenethylamine families. It is an amine synthesized ...

to neuropeptides

Neuropeptides are chemical messengers made up of small chains of amino acids that are synthesized and released by neurons. Neuropeptides typically bind to G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) to modulate neural activity and other tissues like the ...

such as endorphins

Endorphins (contracted from endogenous morphine) are peptides produced in the brain that block the perception of pain and increase feelings of wellbeing. They are produced and stored in the pituitary gland of the brain. Endorphins are endogeno ...

. Moreover, some molecules may fit into more than one class, e.g. epinephrine

Adrenaline, also known as epinephrine, is a hormone and medication which is involved in regulating visceral functions (e.g., respiration). It appears as a white microcrystalline granule. Adrenaline is normally produced by the adrenal glands a ...

is a neurotransmitter when secreted by the central nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

and a hormone when secreted by the adrenal medulla

The adrenal medulla () is the inner part of the adrenal gland. It is located at the center of the gland, being surrounded by the adrenal cortex. It is the innermost part of the adrenal gland, consisting of chromaffin cells that secrete catecho ...

.

Some receptors such as HER2

Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase erbB-2 is a protein that normally resides in the membranes of cells and is encoded by the ''ERBB2'' gene. ERBB is abbreviated from erythroblastic oncogene B, a gene originally isolated from the avian genome. The ...

are capable of ligand-independent activation when overexpressed or mutated. This leads to constitutive activation of the pathway, which may or may not be overturned by compensation mechanisms. In the case of HER2, which acts as a dimerization partner of other EGFRs, constitutive activation leads to hyperproliferation and cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

.

Mechanical forces

The prevalence of basement membranes in the tissues of Eumetazoans means that most cell types require attachment to survive. This requirement has led to the development of complex mechanotransduction pathways, allowing cells to sense the stiffness of the substratum. Such signaling is mainly orchestrated in focal adhesions, regions where theintegrin

Integrins are transmembrane receptors that help cell–cell and cell–extracellular matrix (ECM) adhesion. Upon ligand binding, integrins activate signal transduction pathways that mediate cellular signals such as regulation of the cell cycle, o ...

-bound actin

Actin is a family of globular multi-functional proteins that form microfilaments in the cytoskeleton, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells, where it may be present at a concentration of ...

cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

detects changes and transmits them downstream through YAP1. Calcium-dependent cell adhesion molecules

Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) are a subset of cell surface proteins that are involved in the binding of cells with other cells or with the extracellular matrix (ECM), in a process called cell adhesion. In essence, CAMs help cells stick to each ...

such as cadherin

Cadherins (named for "calcium-dependent adhesion") are cell adhesion molecules important in forming adherens junctions that let cells adhere to each other. Cadherins are a class of type-1 transmembrane proteins, and they depend on calcium (Ca2+) ...

s and selectins can also mediate mechanotransduction. Specialised forms of mechanotransduction within the nervous system are responsible for mechanosensation

Mechanosensation is the transduction of mechanical stimuli into neural signals. Mechanosensation provides the basis for the senses of light touch, hearing, proprioception, and pain. Mechanoreceptors found in the skin, called cutaneous mechanorecept ...

: hearing

Hearing, or auditory perception, is the ability to perceive sounds through an organ, such as an ear, by detecting vibrations as periodic changes in the pressure of a surrounding medium. The academic field concerned with hearing is auditory sci ...

, touch

The somatosensory system, or somatic sensory system is a subset of the sensory nervous system. The main functions of the somatosensory system are the perception of external stimuli, the perception of internal stimuli, and the regulation of bo ...

, proprioception

Proprioception ( ) is the sense of self-movement, force, and body position.

Proprioception is mediated by proprioceptors, a type of sensory receptor, located within muscles, tendons, and joints. Most animals possess multiple subtypes of propri ...

and balance

Balance may refer to:

Common meanings

* Balance (ability) in biomechanics

* Balance (accounting)

* Balance or weighing scale

* Balance, as in equality (mathematics) or equilibrium

Arts and entertainment Film

* Balance (1983 film), ''Balance'' ( ...

.

Osmolarity

Cellular and systemic control ofosmotic pressure

Osmotic pressure is the minimum pressure which needs to be applied to a Solution (chemistry), solution to prevent the inward flow of its pure solvent across a semipermeable membrane.

It is also defined as the measure of the tendency of a soluti ...

(the difference in osmolarity

Osmotic concentration, formerly known as osmolarity, is the measure of solute concentration, defined as the number of osmoles (Osm) of solute per litre (L) of solution (osmol/L or Osm/L). The osmolarity of a solution is usually expressed as Osm/ ...

between the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells ( intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

and the extracellular medium) is critical for homeostasis. There are three ways in which cells can detect osmotic stimuli: as changes in macromolecular crowding, ionic strength, and changes in the properties of the plasma membrane or cytoskeleton (the latter being a form of mechanotransduction). These changes are detected by proteins known as osmosensors or osmoreceptors. In humans, the best characterised osmosensors are transient receptor potential channel

Transient receptor potential channels (TRP channels) are a group of ion channels located mostly on the plasma membrane of numerous animal cell types. Most of these are grouped into two broad groups: Group 1 includes TRPC ( "C" for canonical), TRP ...

s present in the primary cilium of human cells. In yeast, the HOG pathway has been extensively characterised.

Temperature

The sensing of temperature in cells is known as thermoception and is primarily mediated bytransient receptor potential channel

Transient receptor potential channels (TRP channels) are a group of ion channels located mostly on the plasma membrane of numerous animal cell types. Most of these are grouped into two broad groups: Group 1 includes TRPC ( "C" for canonical), TRP ...

s. Additionally, animal cells contain a conserved mechanism to prevent high temperatures from causing cellular damage, the heat-shock response. Such response is triggered when high temperatures cause the dissociation of inactive HSF1 from complexes with heat shock proteins Hsp40/ Hsp70 and Hsp90

Hsp90 (heat shock protein 90) is a chaperone (protein), chaperone protein that assists other proteins to protein folding, fold properly, stabilizes proteins against heat stress, and aids in protein degradation. It also stabilizes a number of ...

. With help from the ncRNA ''hsr1'', HSF1 then trimerizes, becoming active and upregulating the expression of its target genes. Many other thermosensory mechanisms exist in both prokaryotes

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' ...

and eukaryotes

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of ...

.

Light

In mammals,light

Light, visible light, or visible radiation is electromagnetic radiation that can be visual perception, perceived by the human eye. Visible light spans the visible spectrum and is usually defined as having wavelengths in the range of 400– ...

controls the sense of sight

Visual perception is the ability to detect light and use it to form an image of the surrounding Biophysical environment, environment. Photodetection without image formation is classified as ''light sensing''. In most vertebrates, visual percept ...

and the circadian clock

A circadian clock, or circadian oscillator, also known as one’s internal alarm clock is a biochemical oscillator that cycles with a stable phase and is synchronized with solar time.

Such a clock's ''in vivo'' period is necessarily almost exact ...

by activating light-sensitive proteins in photoreceptor cell

A photoreceptor cell is a specialized type of neuroepithelial cell found in the retina that is capable of visual phototransduction. The great biological importance of photoreceptors is that they convert light (visible electromagnetic radiation ...

s in the eye

An eye is a sensory organ that allows an organism to perceive visual information. It detects light and converts it into electro-chemical impulses in neurons (neurones). It is part of an organism's visual system.

In higher organisms, the ey ...

's retina

The retina (; or retinas) is the innermost, photosensitivity, light-sensitive layer of tissue (biology), tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some Mollusca, molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focus (optics), focused two-dimensional ...

. In the case of vision, light is detected by rhodopsin

Rhodopsin, also known as visual purple, is a protein encoded by the ''RHO'' gene and a G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR). It is a light-sensitive receptor protein that triggers visual phototransduction in rod cells. Rhodopsin mediates dim ...

in rod and cone cells. In the case of the circadian clock, a different photopigment

Photopigments are unstable pigments that undergo a chemical change when they absorb light. The term is generally applied to the non-protein chromophore Moiety (chemistry), moiety of photosensitive chromoproteins, such as the pigments involved in ph ...

, melanopsin

Melanopsin is a type of photopigment belonging to a larger family of light-sensitive retinylidene protein, retinal proteins called opsins and encoded by the gene ''Opn4''. In the mammalian retina, there are two additional categories of opsins, b ...

, is responsible for detecting light in intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells

Intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (ipRGCs), also called photosensitive retinal ganglion cells (pRGC), or melanopsin-containing retinal ganglion cells (mRGCs), are a type of neuron in the retina of the mammalian eye. The presence ...

.

Receptors

Receptors can be roughly divided into two major classes:intracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

and extracellular

This glossary of biology terms is a list of definitions of fundamental terms and concepts used in biology, the study of life and of living organisms. It is intended as introductory material for novices; for more specific and technical definitions ...

receptors.

Extracellular receptors

Extracellular receptors are integral transmembrane proteins and make up most receptors. They span theplasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

of the cell, with one part of the receptor on the outside of the cell and the other on the inside. Signal transduction occurs as a result of a ligand binding to the outside region of the receptor (the ligand does not pass through the membrane). Ligand-receptor binding induces a change in the conformation of the inside part of the receptor, a process sometimes called "receptor activation". This results in either the activation of an enzyme domain of the receptor or the exposure of a binding site for other intracellular signaling proteins within the cell, eventually propagating the signal through the cytoplasm.

In eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

cells, most intracellular proteins activated by a ligand/receptor interaction possess an enzymatic activity; examples include tyrosine kinase

A tyrosine kinase is an enzyme that can transfer a phosphate group from ATP to the tyrosine residues of specific proteins inside a cell. It functions as an "on" or "off" switch in many cellular functions.

Tyrosine kinases belong to a larger cla ...

and phosphatase

In biochemistry, a phosphatase is an enzyme that uses water to cleave a phosphoric acid Ester, monoester into a phosphate ion and an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. Because a phosphatase enzyme catalysis, catalyzes the hydrolysis of its Substrate ...

s. Often such enzymes are covalently linked to the receptor. Some of them create second messenger

Second messengers are intracellular signaling molecules released by the cell in response to exposure to extracellular signaling molecules—the first messengers. (Intercellular signals, a non-local form of cell signaling, encompassing both first m ...

s such as cyclic AMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP, cyclic AMP, or 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate) is a second messenger, or cellular signal occurring within cells, that is important in many biological processes. cAMP is a derivative of adenosine triph ...

and IP3, the latter controlling the release of intracellular calcium stores into the cytoplasm. Other activated proteins interact with adaptor proteins that facilitate signaling protein interactions and coordination of signaling complexes necessary to respond to a particular stimulus. Enzymes and adaptor proteins are both responsive to various second messenger molecules.

Many adaptor proteins and enzymes activated as part of signal transduction possess specialized protein domains

In molecular biology, a protein domain is a region of a protein's polypeptide chain that is self-stabilizing and that folds independently from the rest. Each domain forms a compact folded three-dimensional structure. Many proteins consist of se ...

that bind to specific secondary messenger molecules. For example, calcium ions bind to the EF hand

The EF hand is a helix–loop–helix structural domain or ''motif'' found in a large family of calcium-binding proteins.

The EF-hand motif contains a helix–loop–helix topology, much like the spread thumb and forefinger of the human hand, in ...

domains of calmodulin

Calmodulin (CaM) (an abbreviation for calcium-modulated protein) is a multifunctional intermediate calcium-binding messenger protein expressed in all Eukaryote, eukaryotic cells. It is an intracellular target of the Second messenger system, sec ...

, allowing it to bind and activate calmodulin-dependent kinase. PIP3 and other phosphoinositides do the same thing to the Pleckstrin homology domains of proteins such as the kinase protein AKT.

G protein–coupled receptors

G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) are a family of integral transmembrane proteins that possess seven transmembrane domains and are linked to a heterotrimericG protein

G proteins, also known as guanine nucleotide-binding proteins, are a Protein family, family of proteins that act as molecular switches inside cells, and are involved in transmitting signals from a variety of stimuli outside a cell (biology), ...

. With nearly 800 members, this is the largest family of membrane proteins and receptors in mammals. Counting all animal species, they add up to over 5000. Mammalian GPCRs are classified into 5 major families: rhodopsin-like, secretin-like, metabotropic glutamate, adhesion

Adhesion is the tendency of dissimilar particles or interface (matter), surfaces to cling to one another. (Cohesion (chemistry), Cohesion refers to the tendency of similar or identical particles and surfaces to cling to one another.)

The ...

and frizzled

Frizzled is a family of atypical G protein-coupled receptor, G protein-coupled receptors that serve as receptors in the Wnt signaling pathway and other signaling pathways. When activated, Frizzled leads to activation of Dishevelled in the cytosol ...

/ smoothened, with a few GPCR groups being difficult to classify due to low sequence similarity, e.g. vomeronasal receptors. Other classes exist in eukaryotes, such as the ''Dictyostelium

''Dictyostelium'' is a genus of single- and multi-celled eukaryotic, phagotrophic bacterivores. Though they are Protista and in no way fungal, they traditionally are known as "slime molds". They are present in most terrestrial ecosystems a ...

'' cyclic AMP receptors and fungal mating pheromone receptors.

Signal transduction by a GPCR begins with an inactive G protein coupled to the receptor; the G protein exists as a heterotrimer consisting of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits. Once the GPCR recognizes a ligand, the conformation of the receptor changes to activate the G protein, causing Gα to bind a molecule of GTP and dissociate from the other two G-protein subunits. The dissociation exposes sites on the subunits that can interact with other molecules. The activated G protein subunits detach from the receptor and initiate signaling from many downstream effector proteins such as phospholipase

A phospholipase is an enzyme that hydrolyzes phospholipids into fatty acids and other lipophilic substances. There are four major classes, termed A, B, C, and D, which are distinguished by the type of reaction which they catalyze:

*Phospholipase ...

s and ion channels

Ion channels are pore-forming membrane proteins that allow ions to pass through the channel pore. Their functions include establishing a resting membrane potential, shaping action potentials and other electrical signals by gating the flow of ...

, the latter permitting the release of second messenger molecules. The total strength of signal amplification by a GPCR is determined by the lifetimes of the ligand-receptor complex and receptor-effector protein complex and the deactivation time of the activated receptor and effectors through intrinsic enzymatic activity; e.g. via protein kinase phosphorylation or b-arrestin-dependent internalization.

A study was conducted where a point mutation

A point mutation is a genetic mutation where a single nucleotide base is changed, inserted or deleted from a DNA or RNA sequence of an organism's genome. Point mutations have a variety of effects on the downstream protein product—consequences ...

was inserted into the gene encoding the chemokine receptor CXCR2; mutated cells underwent a malignant transformation

Malignant transformation is the process by which cells acquire the properties of cancer. This may occur as a primary process in normal tissue, or secondarily as ''malignant degeneration'' of a previously existing benign tumor.

Causes

There are ...

due to the expression of CXCR2 in an active conformation despite the absence of chemokine-binding. This meant that chemokine receptors can contribute to cancer development.

Tyrosine, Ser/Thr and Histidine-specific protein kinases

Receptor tyrosine kinase

Receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) are the high-affinity cell surface receptors for many polypeptide growth factors, cytokines, and hormones. Of the 90 unique tyrosine kinase genes identified in the human genome, 58 encode receptor tyrosine kinas ...

s (RTKs) are transmembrane proteins with an intracellular kinase

In biochemistry, a kinase () is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of phosphate groups from high-energy, phosphate-donating molecules to specific substrates. This process is known as phosphorylation, where the high-energy ATP molecule don ...

domain and an extracellular domain that binds ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's el ...

s; examples include growth factor

A growth factor is a naturally occurring substance capable of stimulating cell proliferation, wound healing, and occasionally cellular differentiation. Usually it is a secreted protein or a steroid hormone. Growth factors are important for ...

receptors such as the insulin receptor. To perform signal transduction, RTKs need to form dimers in the plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

; the dimer is stabilized by ligands binding to the receptor. The interaction between the cytoplasmic domains stimulates the autophosphorylation

In biochemistry, phosphorylation is described as the "transfer of a phosphate group" from a donor to an acceptor. A common phosphorylating agent (phosphate donor) is ATP and a common family of acceptor are alcohols:

:

This equation can be writ ...

of tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a conditionally essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is ...

residues within the intracellular kinase domains of the RTKs, causing conformational changes. Subsequent to this, the receptors' kinase domains are activated, initiating phosphorylation

In biochemistry, phosphorylation is described as the "transfer of a phosphate group" from a donor to an acceptor. A common phosphorylating agent (phosphate donor) is ATP and a common family of acceptor are alcohols:

:

This equation can be writ ...

signaling cascades of downstream cytoplasmic molecules that facilitate various cellular processes such as cell differentiation

Cellular differentiation is the process in which a stem cell changes from one type to a differentiated one. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation happens multiple times during the development of a multicellular ...

and metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

. Many Ser/Thr and dual-specificity protein kinases

A protein kinase is a kinase which selectively modifies other proteins by covalently adding phosphates to them (phosphorylation) as opposed to kinases which modify lipids, carbohydrates, or other molecules. Phosphorylation usually results in a fun ...

are important for signal transduction, either acting downstream of eceptor tyrosine kinases or as membrane-embedded or cell-soluble versions in their own right. The process of signal transduction involves around 560 known protein kinases

A protein kinase is a kinase which selectively modifies other proteins by covalently adding phosphates to them (phosphorylation) as opposed to kinases which modify lipids, carbohydrates, or other molecules. Phosphorylation usually results in a fun ...

and pseudokinases, encoded by the human kinome

As is the case with GPCRs, proteins that bind GTP play a major role in signal transduction from the activated RTK into the cell. In this case, the G proteins are members of the Ras, Rho

Rho (; uppercase Ρ, lowercase ρ or ; or ) is the seventeenth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 100. It is derived from Phoenician alphabet, Phoenician letter resh . Its uppercase form uses the same ...

, and Raf families, referred to collectively as small G proteins. They act as molecular switches usually tethered to membranes by isoprenyl groups linked to their carboxyl ends. Upon activation, they assign proteins to specific membrane subdomains where they participate in signaling. Activated RTKs in turn activate small G proteins that activate guanine nucleotide exchange factor

Guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) are proteins or protein domains that activate monomeric GTPases by stimulating the release of guanosine diphosphate (GDP) to allow binding of guanosine triphosphate (GTP). A variety of unrelated structu ...

s such as SOS1

Son of sevenless homolog 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''SOS1'' gene.

Function

SOS1 is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF) which interacts with Ras protein, Ras proteins to phosphorylate GDP into GTP, or from an inacti ...

. Once activated, these exchange factors can activate more small G proteins, thus amplifying the receptor's initial signal. The mutation of certain RTK genes, as with that of GPCRs, can result in the expression of receptors that exist in a constitutively activated state; such mutated genes may act as oncogenes

An oncogene is a gene that has the potential to cause cancer. In tumor cells, these genes are often mutated, or expressed at high levels.

.

Histidine-specific protein kinases are structurally distinct from other protein kinases and are found in prokaryotes, fungi, and plants as part of a two-component signal transduction mechanism: a phosphate group from ATP is first added to a histidine residue within the kinase, then transferred to an aspartate residue on a receiver domain on a different protein or the kinase itself, thus activating the aspartate residue.

Integrins

Integrins are produced by a wide variety of cells; they play a role in cell attachment to other cells and theextracellular matrix

In biology, the extracellular matrix (ECM), also called intercellular matrix (ICM), is a network consisting of extracellular macromolecules and minerals, such as collagen, enzymes, glycoproteins and hydroxyapatite that provide structural and bio ...

and in the transduction of signals from extracellular matrix components such as fibronectin

Fibronectin is a high- molecular weight (~500-~600 kDa) glycoprotein of the extracellular matrix that binds to membrane-spanning receptor proteins called integrins. Fibronectin also binds to other extracellular matrix proteins such as col ...

and collagen

Collagen () is the main structural protein in the extracellular matrix of the connective tissues of many animals. It is the most abundant protein in mammals, making up 25% to 35% of protein content. Amino acids are bound together to form a trip ...

. Ligand binding to the extracellular domain of integrins changes the protein's conformation, clustering it at the cell membrane to initiate signal transduction. Integrins lack kinase activity; hence, integrin-mediated signal transduction is achieved through a variety of intracellular protein kinases and adaptor molecules, the main coordinator being integrin-linked kinase. As shown in the adjacent picture, cooperative integrin-RTK signaling determines the timing of cellular survival, apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, proliferation, and differentiation.

Important differences exist between integrin-signaling in circulating blood cells and non-circulating cells such as epithelial cell

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of Cell (biology), cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial (Mesothelium, mesothelial) tissues line ...

s; integrins of circulating cells are normally inactive. For example, cell membrane integrins on circulating leukocytes

White blood cells (scientific name leukocytes), also called immune cells or immunocytes, are cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign entities. White blood cells are genera ...

are maintained in an inactive state to avoid epithelial cell attachment; they are activated only in response to stimuli such as those received at the site of an inflammatory response

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

. In a similar manner, integrins at the cell membrane of circulating platelets

Platelets or thrombocytes () are a part of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping to form a blood clot. Platelets have no cell nucleus; they are fragments of cyto ...

are normally kept inactive to avoid thrombosis

Thrombosis () is the formation of a Thrombus, blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thrombocytes) and fib ...

. Epithelial cells (which are non-circulating) normally have active integrins at their cell membrane, helping maintain their stable adhesion to underlying stromal cells that provide signals to maintain normal functioning.

In plants, there are no bona fide integrin receptors identified to date; nevertheless, several integrin-like proteins were proposed based on structural homology with the metazoan receptors. Plants contain integrin-linked kinases that are very similar in their primary structure with the animal ILKs. In the experimental model plant ''Arabidopsis thaliana

''Arabidopsis thaliana'', the thale cress, mouse-ear cress or arabidopsis, is a small plant from the mustard family (Brassicaceae), native to Eurasia and Africa. Commonly found along the shoulders of roads and in disturbed land, it is generally ...

'', one of the integrin-linked kinase genes, ''ILK1'', has been shown to be a critical element in the plant immune response to signal molecules from bacterial pathogens and plant sensitivity to salt and osmotic stress. ILK1 protein interacts with the high-affinity potassium transporter HAK5 and with the calcium sensor CML9.

Toll-like receptors

When activated, toll-like receptors (TLRs) take adapter molecules within the cytoplasm of cells in order to propagate a signal. Four adaptor molecules are known to be involved in signaling, which areMyd88

Myeloid differentiation primary response 88 (MYD88) is a protein that, in humans, is encoded by the ''MYD88'' gene. originally discovered in the laboratory of Dan A. Liebermann (Lord et al. Oncogene 1990) as a Myeloid differentiation primary resp ...

, TIRAP, TRIF, and TRAM

A tram (also known as a streetcar or trolley in Canada and the United States) is an urban rail transit in which Rolling stock, vehicles, whether individual railcars or multiple-unit trains, run on tramway tracks on urban public streets; some ...

. These adapters activate other intracellular molecules such as IRAK1

Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK-1) is an enzyme in humans encoded by the ''IRAK1'' gene. IRAK-1 plays an important role in the regulation of the expression of inflammatory genes by immune cells, such as monocytes and macrophages, ...

, IRAK4

IRAK-4 (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 4), in the IRAK family, is a protein kinase involved in signaling innate immune responses from Toll-like receptors. It also supports signaling from T-cell receptors. IRAK4 contains domain structure ...

, TBK1, and IKKi that amplify the signal, eventually leading to the induction or suppression of genes that cause certain responses. Thousands of genes are activated by TLR signaling, implying that this method constitutes an important gateway for gene modulation.

Ligand-gated ion channels

A ligand-gated ion channel, upon binding with a ligand, changes conformation to open a channel in the cell membrane through which ions relaying signals can pass. An example of this mechanism is found in the receiving cell of a neuralsynapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

. The influx of ions that occurs in response to the opening of these channels induces action potentials

An action potential (also known as a nerve impulse or "spike" when in a neuron) is a series of quick changes in voltage across a cell membrane. An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell rapidly rises and falls. ...

, such as those that travel along nerves, by depolarizing the membrane of post-synaptic cells, resulting in the opening of voltage-gated ion channels.

An example of an ion allowed into the cell during a ligand-gated ion channel opening is Ca2+; it acts as a second messenger initiating signal transduction cascades and altering the physiology of the responding cell. This results in amplification of the synapse response between synaptic cells by remodelling the dendritic spines involved in the synapse.

Intracellular receptors

Intracellular receptors, such asnuclear receptor

In the field of molecular biology, nuclear receptors are a class of proteins responsible for sensing steroids, thyroid hormones, vitamins, and certain other molecules. These intracellular receptors work with other proteins to regulate the ex ...

s and cytoplasmic receptors, are soluble proteins localized within their respective areas. The typical ligands for nuclear receptors are non-polar hormones like the steroid

A steroid is an organic compound with four fused compound, fused rings (designated A, B, C, and D) arranged in a specific molecular configuration.

Steroids have two principal biological functions: as important components of cell membranes t ...

hormones testosterone

Testosterone is the primary male sex hormone and androgen in Male, males. In humans, testosterone plays a key role in the development of Male reproductive system, male reproductive tissues such as testicles and prostate, as well as promoting se ...

and progesterone

Progesterone (; P4) is an endogenous steroid and progestogen sex hormone involved in the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and embryogenesis of humans and other species. It belongs to a group of steroid hormones called the progestogens and is the ma ...

and derivatives of vitamins A and D. To initiate signal transduction, the ligand must pass through the plasma membrane by passive diffusion. On binding with the receptor, the ligands pass through the nuclear membrane

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer polar membrane, membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the Cell nucleus, nucleus, which encloses the genome, genetic material.

The nuclear envelope con ...

into the nucleus, altering gene expression.

Activated nuclear receptors attach to the DNA at receptor-specific hormone-responsive element (HRE) sequences, located in the promoter region of the genes activated by the hormone-receptor complex. Due to their enabling gene transcription, they are alternatively called inductors of gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

. All hormones that act by regulation of gene expression have two consequences in their mechanism of action; their effects are produced after a characteristically long period of time and their effects persist for another long period of time, even after their concentration has been reduced to zero, due to a relatively slow turnover of most enzymes and proteins that would either deactivate or terminate ligand binding onto the receptor.

Nucleic receptors have DNA-binding domains containing zinc finger

A zinc finger is a small protein structural motif that is characterized by the coordination of one or more zinc ions (Zn2+) which stabilizes the fold. The term ''zinc finger'' was originally coined to describe the finger-like appearance of a ...

s and a ligand-binding domain; the zinc fingers stabilize DNA binding by holding its phosphate backbone. DNA sequences that match the receptor are usually hexameric repeats of any kind; the sequences are similar but their orientation and distance differentiate them. The ligand-binding domain is additionally responsible for dimerization of nucleic receptors prior to binding and providing structures for transactivation used for communication with the translational apparatus.

Steroid receptors are a subclass of nuclear receptors located primarily within the cytosol. In the absence of steroids, they associate in an aporeceptor complex containing chaperone or heatshock proteins (HSPs). The HSPs are necessary to activate the receptor by assisting the protein to fold in a way such that the signal sequence enabling its passage into the nucleus is accessible. Steroid receptors, on the other hand, may be repressive on gene expression when their transactivation domain is hidden. Receptor activity can be enhanced by phosphorylation of serine

Serine

(symbol Ser or S) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α- amino group (which is in the protonated − form under biological conditions), a carboxyl group (which is in the deprotonated − ...

residues at their N-terminal as a result of another signal transduction pathway, a process called crosstalk

In electronics, crosstalk (XT) is a phenomenon by which a signal transmitted on one circuit or channel of a transmission system creates an undesired effect in another circuit or channel. Crosstalk is usually caused by undesired capacitive, ...

.

Retinoic acid receptor

The retinoic acid receptor (RAR) is a type of nuclear receptor which can also act as a ligand-activated transcription factor that is activated by both all-trans retinoic acid and 9-cis retinoic acid, retinoid active derivatives of Vitamin A. ...

s are another subset of nuclear receptors. They can be activated by an endocrine-synthesized ligand that entered the cell by diffusion, a ligand synthesised from a precursor like retinol

Retinol, also called vitamin A1, is a fat-soluble vitamin in the vitamin A family that is found in food and used as a dietary supplement. Retinol or other forms of vitamin A are needed for vision, cellular development, maintenance of skin and ...

brought to the cell through the bloodstream or a completely intracellularly synthesised ligand like prostaglandin

Prostaglandins (PG) are a group of physiology, physiologically active lipid compounds called eicosanoids that have diverse hormone-like effects in animals. Prostaglandins have been found in almost every Tissue (biology), tissue in humans and ot ...

. These receptors are located in the nucleus and are not accompanied by HSPs. They repress their gene by binding to their specific DNA sequence when no ligand binds to them, and vice versa.

Certain intracellular receptors of the immune system are cytoplasmic receptors; recently identified NOD-like receptors (NLRs) reside in the cytoplasm of some eukaryotic

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the Domain (biology), domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose Cell (biology), cells have a membrane-bound cell nucleus, nucleus. All animals, plants, Fungus, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms ...

cells and interact with ligands using a leucine-rich repeat

A leucine-rich repeat (LRR) is a protein structural motif that forms an α/β horseshoe tertiary structure, fold. It is composed of repeating 20–30 amino acid stretches that are unusually rich in the hydrophobic amino acid leucine. These Pr ...

(LRR) motif similar to TLRs. Some of these molecules like NOD2 interact with RIP2 kinase that activates NF-κB

Nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NF-κB) is a family of transcription factor protein complexes that controls transcription (genetics), transcription of DNA, cytokine production and cell survival. NF-κB is found i ...

signaling, whereas others like NALP3 interact with inflammatory caspases and initiate processing of particular cytokine

Cytokines () are a broad and loose category of small proteins (~5–25 kDa) important in cell signaling.

Cytokines are produced by a broad range of cells, including immune cells like macrophages, B cell, B lymphocytes, T cell, T lymphocytes ...

s like interleukin-1

The Interleukin-1 family (IL-1 family) is a group of 11 cytokines that plays a central role in the regulation of immune and inflammatory responses to infections or sterile insults.

Discovery

Discovery of these cytokines began with studies on t ...

β.

Second messengers

First messengers are the signaling molecules (hormones, neurotransmitters, and paracrine/autocrine agents) that reach the cell from the extracellular fluid and bind to their specific receptors. Second messengers are the substances that enter the cytoplasm and act within the cell to trigger a response. In essence, second messengers serve as chemical relays from the plasma membrane to the cytoplasm, thus carrying out intracellular signal transduction.Calcium

The release of calcium ions from theendoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a part of a transportation system of the eukaryote, eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. The word endoplasmic means "within the cytoplasm", and reticulum is Latin for ...

into the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells ( intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

results in its binding to signaling proteins that are then activated; it is then sequestered in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum and the mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

. Two combined receptor/ion channel proteins control the transport of calcium: the InsP3-receptor that transports calcium upon interaction with inositol triphosphate

Inositol trisphosphate or inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate abbreviated InsP3 or Ins3P or IP3 is an inositol phosphate signaling molecule. It is made by hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a phospholipid that is located in the p ...

on its cytosolic side; and the ryanodine receptor

Ryanodine receptors (RyR) make up a class of high-conductance, intracellular calcium channels present in various forms, such as animal muscles and neurons. There are three major isoforms of the ryanodine receptor, which are found in different tissu ...

named after the alkaloid

Alkaloids are a broad class of natural product, naturally occurring organic compounds that contain at least one nitrogen atom. Some synthetic compounds of similar structure may also be termed alkaloids.

Alkaloids are produced by a large varie ...

ryanodine, similar to the InsP3 receptor but having a feedback mechanism

Feedback occurs when outputs of a system are routed back as inputs as part of a chain of cause and effect that forms a circuit or loop. The system can then be said to ''feed back'' into itself. The notion of cause-and-effect has to be handled ...

that releases more calcium upon binding with it. The nature of calcium in the cytosol means that it is active for only a very short time, meaning its free state concentration is very low and is mostly bound to organelle molecules like calreticulin when inactive.

Calcium is used in many processes including muscle contraction, neurotransmitter release from nerve endings, and cell migration

Cell migration is a central process in the development and maintenance of multicellular organisms. Tissue formation during embryogenesis, embryonic development, wound healing and immune system, immune responses all require the orchestrated movemen ...

. The three main pathways that lead to its activation are GPCR pathways, RTK pathways, and gated ion channels; it regulates proteins either directly or by binding to an enzyme.

Lipid messengers

Lipophilic second messenger molecules are derived from lipids residing in cellular membranes; enzymes stimulated by activated receptors activate the lipids by modifying them. Examples include diacylglycerol andceramide

Ceramides are a family of waxy lipid molecules. A ceramide is composed of sphingosine and a fatty acid joined by an amide bond. Ceramides are found in high concentrations within the cell membrane of Eukaryote, eukaryotic cells, since they are co ...

, the former required for the activation of protein kinase C

In cell biology, protein kinase C, commonly abbreviated to PKC (EC 2.7.11.13), is a family of protein kinase enzymes that are involved in controlling the function of other proteins through the phosphorylation of hydroxyl groups of serine and t ...

.

Nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (NO) acts as a second messenger because it is afree radical

A daughter category of ''Ageing'', this category deals only with the biological aspects of ageing.

Ageing

Biogerontology

Biological processes

Causes of death

Cellular processes

Gerontology

Life extension

Metabolic disorders

Metabolism

...

that can diffuse through the plasma membrane and affect nearby cells. It is synthesised from arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidinium, guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) a ...

and oxygen by the NO synthase and works through activation of soluble guanylyl cyclase, which when activated produces another second messenger, cGMP. NO can also act through covalent modification of proteins or their metal co-factors; some have a redox mechanism and are reversible. It is toxic in high concentrations and causes damage during stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

, but is the cause of many other functions like the relaxation of blood vessels, apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

, and penile erection

An erection (clinically: penile erection or penile tumescence) is a Physiology, physiological phenomenon in which the penis becomes firm, engorged, and enlarged. Penile erection is the result of a complex interaction of psychological, neural, ...

s.

Redox signaling

In addition to nitric oxide, other electronically activated species are also signal-transducing agents in a process calledredox signaling

''Antioxidants & Redox Signaling '' is a peer-reviewed scientific journal covering reduction–oxidation (redox) signaling and antioxidant research. It covers topics such as reactive oxygen species/reactive nitrogen species (ROS/RNS) as messenger ...

. Examples include superoxide

In chemistry, a superoxide is a compound that contains the superoxide ion, which has the chemical formula . The systematic name of the anion is dioxide(1−). The reactive oxygen ion superoxide is particularly important as the product of t ...

, hydrogen peroxide

Hydrogen peroxide is a chemical compound with the formula . In its pure form, it is a very pale blue liquid that is slightly more viscosity, viscous than Properties of water, water. It is used as an oxidizer, bleaching agent, and antiseptic, usua ...

, carbon monoxide

Carbon monoxide (chemical formula CO) is a poisonous, flammable gas that is colorless, odorless, tasteless, and slightly less dense than air. Carbon monoxide consists of one carbon atom and one oxygen atom connected by a triple bond. It is the si ...

, and hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

. Redox signaling also includes active modulation of electronic flows in semiconductive biological macromolecules.

Cellular responses

Gene activations and metabolism alterations are examples of cellular responses to extracellular stimulation that require signal transduction. Gene activation leads to further cellular effects, since the products of responding genes include instigators of activation; transcription factors produced as a result of a signal transduction cascade can activate even more genes. Hence, an initial stimulus can trigger the expression of a large number of genes, leading to physiological events like the increased uptake of glucose from the blood stream and the migration of neutrophils to sites of infection. The set of genes and their activation order to certain stimuli is referred to as a genetic program. Mammalian cells require stimulation for cell division and survival; in the absence ofgrowth factor

A growth factor is a naturally occurring substance capable of stimulating cell proliferation, wound healing, and occasionally cellular differentiation. Usually it is a secreted protein or a steroid hormone. Growth factors are important for ...

, apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

ensues. Such requirements for extracellular stimulation are necessary for controlling cell behavior in unicellular and multicellular organisms; signal transduction pathways are perceived to be so central to biological processes that a large number of diseases are attributed to their dysregulation.

Three basic signals determine cellular growth:

* Stimulatory (growth factors)

** Transcription dependent responseFor example, steroids act directly as transcription factor (gives slow response, as transcription factor must bind DNA, which needs to be transcribed. Produced mRNA needs to be translated, and the produced protein/peptide can undergo

posttranslational modification

In molecular biology, post-translational modification (PTM) is the covalent process of changing proteins following protein biosynthesis. PTMs may involve enzymes or occur spontaneously. Proteins are created by ribosomes, which translate mRNA ...

(PTM))

** Transcription independent responseFor example, epidermal growth factor (EGF) binds the

epidermal growth factor receptor

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR; ErbB-1; HER1 in humans) is a transmembrane protein that is a receptor (biochemistry), receptor for members of the epidermal growth factor family (EGF family) of extracellular protein ligand (biochemistry ...

(EGFR), which causes dimerization and autophosphorylation of the EGFR, which in turn activates the intracellular signaling pathway .

* Inhibitory (cell-cell contact)

* Permissive (cell-matrix interactions)

The combination of these signals is integrated into altered cytoplasmic machinery which leads to altered cell behaviour.

Major pathways

Following are some major signaling pathways, demonstrating how ligands binding to their receptors can affect second messengers and eventually result in altered cellular responses.

*

Following are some major signaling pathways, demonstrating how ligands binding to their receptors can affect second messengers and eventually result in altered cellular responses.

* MAPK/ERK pathway

The MAPK/ERK pathway (also known as the Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway) is a chain of proteins in the cell (biology), cell that communicates a signal from a Receptor (biochemistry), receptor on the surface of the cell to the DNA in the nucleus of the cel ...

: A pathway that couples intracellular responses to the binding of growth factor

A growth factor is a naturally occurring substance capable of stimulating cell proliferation, wound healing, and occasionally cellular differentiation. Usually it is a secreted protein or a steroid hormone. Growth factors are important for ...

s to cell surface receptor

Receptor may refer to:

* Sensory receptor, in physiology, any neurite structure that, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and respond ...

s. This pathway is very complex and includes many protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

components. In many cell types, activation of this pathway promotes cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

, and many forms of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

are associated with aberrations in it.

* cAMP-dependent pathway

In the field of molecular biology, the cAMP-dependent pathway, also known as the adenylyl cyclase pathway, is a G protein-coupled receptor-triggered signaling cascade used in cell communication.

Discovery

cAMP was discovered by Earl Sutherla ...

: In humans, cAMP works by activating protein kinase A (PKA, cAMP-dependent protein kinase

In cell biology, protein kinase A (PKA) is a family of serine-threonine kinases whose activity is dependent on cellular levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP). PKA is also known as cAMP-dependent protein kinase (). PKA has several functions in the cell, ...

) (see picture), and, thus, further effects depend mainly on cAMP-dependent protein kinase

In cell biology, protein kinase A (PKA) is a family of serine-threonine kinases whose activity is dependent on cellular levels of cyclic AMP (cAMP). PKA is also known as cAMP-dependent protein kinase (). PKA has several functions in the cell, ...

, which vary based on the type of cell.

* IP3/DAG pathway: PLC cleaves the phospholipid

Phospholipids are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate or PtdIns(4,5)''P''2, also known simply as PIP2 or PI(4,5)P2, is a minor phospholipid component of cell membranes. PtdIns(4,5)''P''2 is enriched at the plasma membrane where it is a substrate for a number of ...

(PIP2), yielding diacyl glycerol (DAG) and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate

Inositol trisphosphate or inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate abbreviated InsP3 or Ins3P or IP3 is an inositol phosphate signaling molecule. It is made by hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a phospholipid that is located in the p ...

(IP3). DAG remains bound to the membrane, and IP3 is released as a soluble structure into the cytosol

The cytosol, also known as cytoplasmic matrix or groundplasm, is one of the liquids found inside cells ( intracellular fluid (ICF)). It is separated into compartments by membranes. For example, the mitochondrial matrix separates the mitochondri ...

. IP3 then diffuses through the cytosol to bind to IP3 receptors, particular calcium channel

A calcium channel is an ion channel which shows selective permeability to calcium ions. It is sometimes synonymous with voltage-gated calcium channel, which are a type of calcium channel regulated by changes in membrane potential. Some calcium chan ...

s in the endoplasmic reticulum

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is a part of a transportation system of the eukaryote, eukaryotic cell, and has many other important functions such as protein folding. The word endoplasmic means "within the cytoplasm", and reticulum is Latin for ...

(ER). These channels are specific to calcium

Calcium is a chemical element; it has symbol Ca and atomic number 20. As an alkaline earth metal, calcium is a reactive metal that forms a dark oxide-nitride layer when exposed to air. Its physical and chemical properties are most similar to it ...

and allow the passage of only calcium to move through. This causes the cytosolic concentration of Calcium to increase, causing a cascade of intracellular changes and activity. In addition, calcium and DAG together works to activate PKC, which goes on to phosphorylate other molecules, leading to altered cellular activity. End-effects include taste, manic depression, tumor promotion, etc.

History

The earliest notion of signal transduction can be traced back to 1855, whenClaude Bernard

Claude Bernard (; 12 July 1813 – 10 February 1878) was a French physiologist. I. Bernard Cohen of Harvard University called Bernard "one of the greatest of all men of science". He originated the term ''milieu intérieur'' and the associated c ...

proposed that ductless glands such as the spleen

The spleen (, from Ancient Greek '' σπλήν'', splḗn) is an organ (biology), organ found in almost all vertebrates. Similar in structure to a large lymph node, it acts primarily as a blood filter.

The spleen plays important roles in reg ...

, the thyroid

The thyroid, or thyroid gland, is an endocrine gland in vertebrates. In humans, it is a butterfly-shaped gland located in the neck below the Adam's apple. It consists of two connected lobes. The lower two thirds of the lobes are connected by ...

and adrenal gland

The adrenal glands (also known as suprarenal glands) are endocrine glands that produce a variety of hormones including adrenaline and the steroids aldosterone and cortisol. They are found above the kidneys. Each gland has an outer adrenal corte ...

s, were responsible for the release of "internal secretions" with physiological effects.Bradshaw & Dennis (2010) p. 1. Bernard's "secretions" were later named "hormones

A hormone (from the Greek participle , "setting in motion") is a class of signaling molecules in multicellular organisms that are sent to distant organs or tissues by complex biological processes to regulate physiology and behavior. Hormones a ...

" by Ernest Starling

Ernest Henry Starling (17 April 1866 – 2 May 1927) was a British physiologist who contributed many fundamental ideas to this subject. These ideas were important parts of the British contribution to physiology, which at that time led the world. ...

in 1905. Together with William Bayliss

Sir William Maddock Bayliss (2 May 1860 – 27 August 1924) was an English physiologist.

Life

He was born in Wednesbury, Staffordshire but shortly thereafter his father, a successful merchant of ornamental ironwork, moved his family to a ...

, Starling had discovered secretin Secretin is a hormone that regulates water homeostasis throughout the body and influences the environment of the duodenum by regulating secretions in the stomach, pancreas, and liver. It is a peptide hormone produced in the S cells of the duodenum ...

in 1902. Although many other hormones, most notably insulin

Insulin (, from Latin ''insula'', 'island') is a peptide hormone produced by beta cells of the pancreatic islets encoded in humans by the insulin (''INS)'' gene. It is the main Anabolism, anabolic hormone of the body. It regulates the metabol ...

, were discovered in the following years, the mechanisms remained largely unknown.

The discovery of nerve growth factor

Nerve growth factor (NGF) is a neurotrophic factor and neuropeptide primarily involved in the regulation of growth, maintenance, proliferation, and survival of certain target neurons. It is perhaps the prototypical growth factor, in that it was ...

by Rita Levi-Montalcini

Rita Levi-Montalcini ( , ; 22 April 1909 – 30 December 2012) was an Italian neurobiologist. She was awarded the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine jointly with colleague Stanley Cohen for the discovery of nerve growth factor ( ...

in 1954, and epidermal growth factor by Stanley Cohen in 1962, led to more detailed insights into the molecular basis of cell signaling, in particular growth factor

A growth factor is a naturally occurring substance capable of stimulating cell proliferation, wound healing, and occasionally cellular differentiation. Usually it is a secreted protein or a steroid hormone. Growth factors are important for ...

s. Their work, together with Earl Wilbur Sutherland

Earl Wilbur Sutherland Jr. (November 19, 1915 – March 9, 1974) was an American pharmacologist and biochemist born in Burlingame, Kansas. Sutherland won a Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1971 "for his discoveries concerning the mechan ...

's discovery of cyclic AMP

Cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP, cyclic AMP, or 3',5'-cyclic adenosine monophosphate) is a second messenger, or cellular signal occurring within cells, that is important in many biological processes. cAMP is a derivative of adenosine triph ...

in 1956, prompted the redefinition of endocrine signaling to include only signaling from glands, while the terms autocrine

Autocrine signaling is a form of cell signaling in which a cell secretes a hormone or chemical messenger (called the autocrine agent) that binds to autocrine receptors on that same cell, leading to changes in the cell. This can be contrasted with ...

and paracrine

In cellular biology, paracrine signaling is a form of cell signaling, a type of cellular communication (biology), cellular communication in which a Cell (biology), cell produces a signal to induce changes in nearby cells, altering the behaviour of ...