Overview

Large numbers of enslaved Africans and European, mostly Spanish, immigrants came to Fernando Ortiz, the first great Cuban folklorist, described Cuba's musical innovations as arising from the interplay ('transculturation') between enslaved Africans settled on large sugar

Fernando Ortiz, the first great Cuban folklorist, described Cuba's musical innovations as arising from the interplay ('transculturation') between enslaved Africans settled on large sugar 18th and 19th centuries

Among internationally heralded composers of the "serious" genre can be counted the Baroque composer

Among internationally heralded composers of the "serious" genre can be counted the Baroque composer  In the hands of his successor, Ignacio Cervantes Kavanagh, the piano idiom related to the contradanza achieved even greater sophistication. Cervantes was called by

In the hands of his successor, Ignacio Cervantes Kavanagh, the piano idiom related to the contradanza achieved even greater sophistication. Cervantes was called by  During the middle years of the 19th century, a young American musician came to Havana:

During the middle years of the 19th century, a young American musician came to Havana: 20th-century classical and art music

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th a number of composers excel within the Cuban music panorama. They cultivated genres such as the popular song and the concert

Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th a number of composers excel within the Cuban music panorama. They cultivated genres such as the popular song and the concert  The work of José Marín Varona links the Cuban musical activity from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. In 1896, the composer included in his zarzuela "El Brujo" the first Cuban guajira which has been historically documented.

About this piece, composer

The work of José Marín Varona links the Cuban musical activity from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. In 1896, the composer included in his zarzuela "El Brujo" the first Cuban guajira which has been historically documented.

About this piece, composer  After his student days, Caturla lived all his life in the small central town of Remedios, where he became a lawyer to support his growing family. His ''Tres danzas cubanas'' for symphony orchestra was first performed in Spain in 1929. ''Bembe'' was premiered in Havana the same year. His ''Obertura cubana'' won first prize in a national contest in 1938. Caturla was murdered at 34 by a young gambler.

After his student days, Caturla lived all his life in the small central town of Remedios, where he became a lawyer to support his growing family. His ''Tres danzas cubanas'' for symphony orchestra was first performed in Spain in 1929. ''Bembe'' was premiered in Havana the same year. His ''Obertura cubana'' won first prize in a national contest in 1938. Caturla was murdered at 34 by a young gambler.

Founded in 1942 under the guidance of José Ardévol (1911–1981), a Catalan composer established in Cuba since 1930, the "Grupo de Renovación Musical" served as a platform for a group of young composers to develop a proactive movement with the purpose of improving and literally renovating the quality of the Cuban musical environment. During its existence from 1942 to 1948, the group organized numerous concerts at the Havana Lyceum in order to present their avant-garde compositions to the general public and fostered within its members the development of many future conductors, art critics, performers and professors. They also started a process of investigation and reevaluation of the Cuban music in general, discovering the outstanding work of Carlo Borbolla and promoting the compositions of Saumell, Cervantes, Caturla and Roldán. The "Grupo de Renovación Musical" included the following composers: Hilario González, Harold Gramatges,

Founded in 1942 under the guidance of José Ardévol (1911–1981), a Catalan composer established in Cuba since 1930, the "Grupo de Renovación Musical" served as a platform for a group of young composers to develop a proactive movement with the purpose of improving and literally renovating the quality of the Cuban musical environment. During its existence from 1942 to 1948, the group organized numerous concerts at the Havana Lyceum in order to present their avant-garde compositions to the general public and fostered within its members the development of many future conductors, art critics, performers and professors. They also started a process of investigation and reevaluation of the Cuban music in general, discovering the outstanding work of Carlo Borbolla and promoting the compositions of Saumell, Cervantes, Caturla and Roldán. The "Grupo de Renovación Musical" included the following composers: Hilario González, Harold Gramatges,  After the

After the 21st-century classical and art music

During the last decades of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century a new generation of composers emerged into the Cuban classical music panorama. Most of them received a solid musical education provided by the official arts school system created by the Cuban government and graduated from theElectroacoustic music in Cuba

Juan Blanco was the first Cuban composer to create an electroacoustic piece in 1961. This first composition, titled "Musica Para Danza", was produced with just an oscillator and three common tape recorders. As a result of the enormous scarcity generated by the trade embargo placed on Cuba by the United States, access to the necessary technological resources to produce electroacoustic music was always very limited for anyone interested. For this reason, it was not until 1969 that another Cuban composer,Classical guitar in Cuba

From the 16th to the 19th century

The guitar (as it is known today or in one of its historical versions) has been present in Cuba since the discovery of the island by Spain. As early as the 16th century, a musician named Juan Ortiz, from the village of Trinidad, is mentioned by famous chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo as "gran tañedor de vihuela y viola" ("a great performer of the20th century and beyond

Severino López was born in Matanzas. He studied guitar in Cuba with Juan Martín Sabio and Pascual Roch, and in Spain with renowned Catalan guitarist Miguel Llobet. Severino López is considered the initiator in Cuba of the guitar school founded by Francisco Tárrega in Spain. Clara Romero (1888-1951), founder of the modern Cuban School of Guitar, studied in Spain with Nicolás Prats and in Cuba with Félix Guerrero. She inaugurated the guitar department at the Havana Municipal Conservatory in 1931, where she also introduced the teachings of the Cuban folk guitar style. She created the Guitar Society of Cuba (Sociedad Guitarrística de Cuba) in 1940, and also the "Guitar" (Guitarra) magazine, with the purpose of promoting the Society's activities. She was the professor of many Cuban guitarists including her sonModern Cuban Guitar School

After the Cuban revolution in 1959,

After the Cuban revolution in 1959, New generations

Since the 1960s, several generations of guitar performers, professors and composers have been formed under the Cuban Guitar School at educational institutions such as the Havana Municipal Conservatory, the National School of Arts, and the Instituto Superior de Arte. Others, such as Manuel Barrueco, a concertist of international renown, developed their careers outside the country. Among many other guitarists related to the Cuban Guitar School are Carlos Molina, Sergio Vitier, Flores Chaviano, Efraín Amador Piñero, Armando Rodriguez Ruidiaz, Martín Pedreira, Lester Carrodeguas, Mario Daly, José Angel Pérez Puentes and Teresa Madiedo. A younger group includes guitarists Rey Guerra, Aldo Rodríguez Delgado, Pedro Cañas, Leyda Lombard, Ernesto Tamayo, Miguel Bonachea, Joaquín Clerch andClassical piano in Cuba

After its arrival in Cuba at the end of the 18th century, the pianoforte (commonly called piano) rapidly became one of the favorite instruments among the Cuban population. Along with the humble guitar, the piano accompanied the popular Cuban "guarachas" and "contradanzas" (derived from the European Country Dances) at salons and ballrooms in Havana and all over the country. As early as in 1804, a concert program in Havana announced a vocal concert "accompanied at the fortepiano by a distinguished foreigner recently arrived" and in 1832, Juan Federico Edelmann (1795-1848), a renowned pianist, son of a famous Alsatian composer and pianist, arrived in Havana and gave a very successful concert at the Teatro Principal. Encouraged by the warm welcome, Edelmann decided to stay in Havana, and he was very soon promoted to an important position within the Santa Cecilia Philharmonic Society. In 1836, he opened a music store and publishing company.

One of the most prestigious Cuban musicians,

After its arrival in Cuba at the end of the 18th century, the pianoforte (commonly called piano) rapidly became one of the favorite instruments among the Cuban population. Along with the humble guitar, the piano accompanied the popular Cuban "guarachas" and "contradanzas" (derived from the European Country Dances) at salons and ballrooms in Havana and all over the country. As early as in 1804, a concert program in Havana announced a vocal concert "accompanied at the fortepiano by a distinguished foreigner recently arrived" and in 1832, Juan Federico Edelmann (1795-1848), a renowned pianist, son of a famous Alsatian composer and pianist, arrived in Havana and gave a very successful concert at the Teatro Principal. Encouraged by the warm welcome, Edelmann decided to stay in Havana, and he was very soon promoted to an important position within the Santa Cecilia Philharmonic Society. In 1836, he opened a music store and publishing company.

One of the most prestigious Cuban musicians, Classical violin in Cuba

From the 16th to the 18th century

Bowed stringed instruments have been present in Cuba since the 16th century. Musician Juan Ortiz from the Ville of Trinidad is mentioned by chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo as a "great performer of "vihuela" and "From the 18th to the 19th century

During the transition from the 18th to the 19th centuries, the Havanese Ulpiano Estrada (1777–1847) offered violin lessons and conducted the Teatro Principal orchestra from 1817 to 1820. Apart from his activity as a violinist, Estrada kept a very active musical career as a conductor of numerous orchestras, bands and operas, and composing many contradanzas and other dance pieces, such as minuets and valses. José Vandergutch, Belgian violinist, arrived at Havana along with his father Juan and brother Francisco, also violinists. They returned at a later time to Belgium, but José established his permanent residence in Havana, where he acquired great recognition. Vandergutch offered numerous concerts as a soloist and accompanied by several orchestras, around the mid-19th century. He was a member of the Classical Music Association and also a Director of The "Asociación Musical de Socorro Mutuo de La Habana." Within the universe of the classical Cuban violin during the 19th century, there are two outstanding Masters that may be considered among the greatest violin virtuosos of all time; they are José White Lafitte y Claudio Brindis de Salas Garrido. After receiving his first musical instruction from his father, the virtuoso Cuban violinist José White Lafitte (1835–1918) offered his first concert in Matanzas on March 21, 1854. In that presentation he was accompanied by the famous American pianist and composer

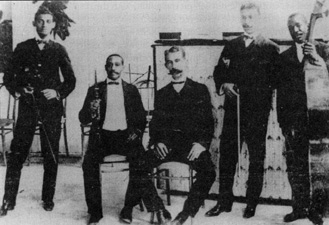

After receiving his first musical instruction from his father, the virtuoso Cuban violinist José White Lafitte (1835–1918) offered his first concert in Matanzas on March 21, 1854. In that presentation he was accompanied by the famous American pianist and composer  Claudio José Domingo Brindis de Salas y Garrido (1852–1911) was a renowned Cuban violinist, son of the also famous violinist, double-bassist and conductor Claudio Brindis de Salas (1800-1972), which conducted one of the most popular orchestras of Havana during the first half of the 19th century, named "La Concha de Oro" (The Golden Conch). Claudio José surpassed the fame and expertise of his father and came to acquire international recognition.

Claudio Brindis de Salas Garrido began his musical studies with his father and continued with Maestros José Redondo and the Belgian José Vandergutch. He offered his first concert in Havana in 1863, in which Vandegutch participated as accompanist. The famous pianist and composer Ignacio Cervantes also participated in that event.

According with the contemporary critique, Brindis de Salas was considered one of the most outstanding violinists of his time at an international level. Alejo Carpentier referred to him as: "The most outstanding black violinist from the 19th century... something without any precedent in the musical history of the continent".

The French government named him member of the

Claudio José Domingo Brindis de Salas y Garrido (1852–1911) was a renowned Cuban violinist, son of the also famous violinist, double-bassist and conductor Claudio Brindis de Salas (1800-1972), which conducted one of the most popular orchestras of Havana during the first half of the 19th century, named "La Concha de Oro" (The Golden Conch). Claudio José surpassed the fame and expertise of his father and came to acquire international recognition.

Claudio Brindis de Salas Garrido began his musical studies with his father and continued with Maestros José Redondo and the Belgian José Vandergutch. He offered his first concert in Havana in 1863, in which Vandegutch participated as accompanist. The famous pianist and composer Ignacio Cervantes also participated in that event.

According with the contemporary critique, Brindis de Salas was considered one of the most outstanding violinists of his time at an international level. Alejo Carpentier referred to him as: "The most outstanding black violinist from the 19th century... something without any precedent in the musical history of the continent".

The French government named him member of the From the 20th to the 21st century

During the first half of the 20th century the name of Amadeo Roldán stands out (1900–1939), because apart from an excellent violinist, professor and conductor, Roldán is considered one of the most important Cuban composers of all time. After his graduation at the(archive from 1 Oc ...

21st century

Already at the beginning of the 21st century the violinists Ilmar López-Gavilán, Mirelys Morgan Verdecia, Ivonne Rubio Padrón, Patricia Quintero and Rafael Machado are worthy of note.Opera in Cuba

Opera has been present in Cuba since the latest part of the 18th century, when the first full-fledged theater, called Coliseo, was built. Since then to present times, the Cuban people have highly enjoyed opera, and many Cuban composers have cultivated the operatic genre, sometimes with great success at an international level. The best Cuban lyrical singer in the 20th century was the operaticThe 19th century

The first documented operatic event inFrom 1901 to 1959

From 1960 to present time

One of the most active and outstanding composers of his generation, Sergio Fernández Barroso (also known asMusicology in Cuba

Throughout the years, the Cuban nation has developed a wealth of musicological material created by numerous investigators and experts on this subject. The work of some authors who provided information about the music in Cuba during the 19th century was usually included in chronicles covering a more general subject. The first investigations and studies specifically dedicated to the musical art and practice did not appear in Cuba until the beginning of the 20th century.http://www.londonmet.ac.uk/library/i18088_3.pdf

A list of important personalities that have contributed to musicological studies in Cuba includes Fernando Ortiz,

Throughout the years, the Cuban nation has developed a wealth of musicological material created by numerous investigators and experts on this subject. The work of some authors who provided information about the music in Cuba during the 19th century was usually included in chronicles covering a more general subject. The first investigations and studies specifically dedicated to the musical art and practice did not appear in Cuba until the beginning of the 20th century.http://www.londonmet.ac.uk/library/i18088_3.pdf

A list of important personalities that have contributed to musicological studies in Cuba includes Fernando Ortiz, Popular music

Hispanic heritage

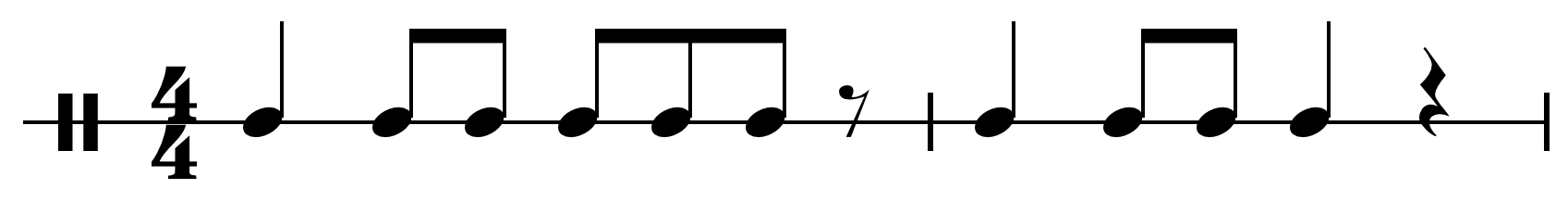

It is obvious that the first popular music played in Cuba after the Spanish conquest was brought by the Spanish conquerors themselves, and was most likely borrowed from the Spanish popular music in vogue during the 16th century. From the 16th to the 18th century some danceable songs that emerged in Spain were associated with Hispanic America, or considered to have originated in America. Some of these songs with picturesque names such as Sarabande, Chaconne, Zambapalo, Retambico and Gurumbé, among others, shared a common trait, its characteristic rhythm called This rhythm has been described as the alternation or superposition of a duple meter and a triple meter (6/8 + 3/4), and its utilization was widespread in the Spanish territory since at least the 13th century, where it appears in one of the Cantigas de Santa María (Como poden per sas culpas).

This rhythm has been described as the alternation or superposition of a duple meter and a triple meter (6/8 + 3/4), and its utilization was widespread in the Spanish territory since at least the 13th century, where it appears in one of the Cantigas de Santa María (Como poden per sas culpas).

Música campesina (peasant music)

It seems that Punto and Zapateo Cubano were the first autochthonous musical genres of the Cuban nation. Although the first printed sample of a Cuban Creole Zapateo (Zapateo Criollo) was not published until 1855 in the "Álbum Regio of Vicente Díaz de Comas", it is possible to find references about the existence of those genres since long time before. Its structural characteristics have survived almost unaltered through a period of more than two hundred years and they are usually considered the most typically Hispanic Cuban popular music genres.

Cuban musicologists María Teresa Linares, Argeliers León and Rolando Antonio Pérez coincide in thinking that Punto and Zapateo are based on Spanish dance –songs (such as chacone and sarabande) that arrived first at the most important population centers such as Havana and Santiago de Cuba and then spread throughout the surrounding rural areas where they were adopted and modified by the peasant (campesino) population at a later time.

It seems that Punto and Zapateo Cubano were the first autochthonous musical genres of the Cuban nation. Although the first printed sample of a Cuban Creole Zapateo (Zapateo Criollo) was not published until 1855 in the "Álbum Regio of Vicente Díaz de Comas", it is possible to find references about the existence of those genres since long time before. Its structural characteristics have survived almost unaltered through a period of more than two hundred years and they are usually considered the most typically Hispanic Cuban popular music genres.

Cuban musicologists María Teresa Linares, Argeliers León and Rolando Antonio Pérez coincide in thinking that Punto and Zapateo are based on Spanish dance –songs (such as chacone and sarabande) that arrived first at the most important population centers such as Havana and Santiago de Cuba and then spread throughout the surrounding rural areas where they were adopted and modified by the peasant (campesino) population at a later time.

Punto guajiro

Punto guajiro orZapateo

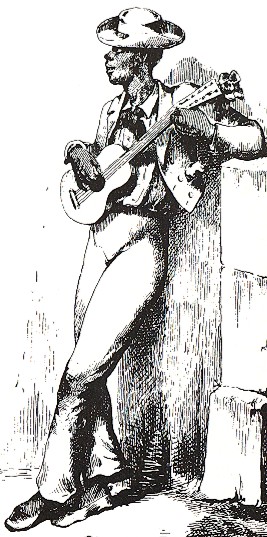

Zapateo is a typical dance of the Cuban "campesino" or "guajiro," of Spanish origin. It is a dance of pairs, involving tapping of the feet, mostly performed by the male partner. Illustrations exist from previous centuries and today it survives cultivated by Folk Music Groups as a fossil genre. It was accompanied by

Zapateo is a typical dance of the Cuban "campesino" or "guajiro," of Spanish origin. It is a dance of pairs, involving tapping of the feet, mostly performed by the male partner. Illustrations exist from previous centuries and today it survives cultivated by Folk Music Groups as a fossil genre. It was accompanied by Guajira

A genre of Cuban song similar to theCriolla

Criolla is a genre of Cuban music which is closely related to the music of the Cuban Coros de Clave and a genre of Cuban popular music called Clave. The Clave became a very popular genre in the Cuban vernacular theater and was created by composer Jorge Anckermann based on the style of the Coros de Clave. The Clave served, in turn, as a model for the creation of a new genre called Criolla. According to musicologist Helio Orovio, "Carmela", the first Criolla, was composed by Luis Casas Romero in 1909, which also created one of the most famous Criollas of all time, "El Mambí".African heritage

Origins of Cuban African groups

Clearly, the origin of African groups in Cuba is due to the island's long history of slavery. Compared to the US, slavery started in Cuba much earlier and continued for decades afterwards. Cuba was the last country in the Americas to abolish the importation of slaves, and the second last to free the slaves. In 1807 theSubsequent organization

The roots of most Afro-Cuban musical forms lie in the cabildos, self-organized social clubs for the African slaves, separate cabildos for separate cultures. The cabildos were formed mainly from four groups: the Yoruba (the Lucumi in Cuba); theAfrican sacred music in Cuba

All these African cultures had musical traditions, which survive erratically to the present day, not always in detail, but in general style. The best preserved are the African polytheistic religions, where, in Cuba at least, the instruments, the language, the chants, the dances and their interpretations are quite well preserved. In what other American countries are the religious ceremonies conducted in the old language(s) of Africa? They certainly are in Lucumí ceremonies, though of course, back in Africa the language has moved on. What unifies all genuine forms of African music is the unity of polyrhythmic percussion, voice (call-and-response) and dance in well-defined social settings, and the absence of melodic instruments of an Arabic or European kind.Yoruba and Congolese rituals

Religious traditions of African origin have survived in Cuba, and are the basis of ritual music, song and dance quite distinct from the secular music and dance. The religion of Yoruban origin is known as ''Lucumí'' or ''Regla de Ocha''; the religion of Congolese origin is known as ''Clave

The clave

The clave Cuban Carnival

In Cuba, the word '' comparsa'' refers to the "Cabildos de Nación" neighbourhood groups that took part in theTumba francesa

Immigrants fromContradanza

The Contradanza is an important precursor of several later popular dances. It arrived in Cuba in the late 18th century from Europe where it had been developed first as the English country dance, and then as the French contradanse. The origin of the word is a corruption of the English term "country dance". The contradanza supplanted the minuet as the most popular dance until from 1842 on, it gave way to the habanera, a quite different style.

The contradanza supplanted the minuet as the most popular dance until from 1842 on, it gave way to the habanera, a quite different style.

Danza

This genere, the offspring of the contradanza, was also danced in lines or squares. It was also a brisk form of music and dance in double or triple time. A repeated 8-bar paseo was followed by two 16-bar sections called the primera and segunda. One famous composer of danzas was Ignacio Cervantes, whose forty-one danzas cubanas were a landmark in musical nationalism. This type of dance was eventually replaced by the danzón, which was, like the habanera, much slower and more sedate.Habanera

The habanera developed out of theDanzón

The European influence on Cuba's later musical development is represented by

The European influence on Cuba's later musical development is represented by  From time to time in its 'career', the danzón acquired African influences in its musical structure. It became more

From time to time in its 'career', the danzón acquired African influences in its musical structure. It became more Danzonete

Early Danzons were purely instrumental. The first to introduce a vocal part in aGuaracha

On January 20, 1801, Buenaventura Pascual Ferrer published a note in a newspaper called "El Regañón de La Habana," in which he refers to certain chants that "run outside there through vulgar voices". Between them he mentioned a "guaracha" named "La Guabina", about which he says: "in the voice of those that sings it, tastes like any thing dirty, indecent or disgusting that you can think about." At a later time, in an undetermined date, "La Guabina" appears published between the first musical scores printed in Havana at the beginning of the 19th century.Linares, María teresa: La guaracha cubana. Imagen del humor criollo. .

According to the commentaries published in "El Regañón de La Habana", it can be concluded that those "guarachas" were very popular within the Havana population at that time, because in the same previously mentioned article the author says: "but most importantly, what bothers me most is the liberty with which a number of chants are sung throughout the streets and town homes, where innocence is insulted and morals offended ... by many individuals, not just of the lowest class, but also by some people that are supposed to be called well educated." Therefore, it can be said that those "guarachas" of a very audacious content, were apparently already sung within a wide social sector of the Havana population.

According to Alejo Carpentier (quoting Buenaventura Pascual Ferrer), at the beginning of the 19th century there were held in Havana up to fifty dance parties every day, where the famous "guaracha" was sung and danced, among other popular pieces.

The

On January 20, 1801, Buenaventura Pascual Ferrer published a note in a newspaper called "El Regañón de La Habana," in which he refers to certain chants that "run outside there through vulgar voices". Between them he mentioned a "guaracha" named "La Guabina", about which he says: "in the voice of those that sings it, tastes like any thing dirty, indecent or disgusting that you can think about." At a later time, in an undetermined date, "La Guabina" appears published between the first musical scores printed in Havana at the beginning of the 19th century.Linares, María teresa: La guaracha cubana. Imagen del humor criollo. .

According to the commentaries published in "El Regañón de La Habana", it can be concluded that those "guarachas" were very popular within the Havana population at that time, because in the same previously mentioned article the author says: "but most importantly, what bothers me most is the liberty with which a number of chants are sung throughout the streets and town homes, where innocence is insulted and morals offended ... by many individuals, not just of the lowest class, but also by some people that are supposed to be called well educated." Therefore, it can be said that those "guarachas" of a very audacious content, were apparently already sung within a wide social sector of the Havana population.

According to Alejo Carpentier (quoting Buenaventura Pascual Ferrer), at the beginning of the 19th century there were held in Havana up to fifty dance parties every day, where the famous "guaracha" was sung and danced, among other popular pieces.

The Musical theatre

From the 18th century (at least) to modern times, popular theatrical formats used, and gave rise to, music and dance. Many famous composers and musicians had their careers launched in the theatres, and many famous compositions got their first airing on the stage. In addition to staging some European operas and operettas, Cuban composers gradually developed ideas that better suited their audience.

From the 18th century (at least) to modern times, popular theatrical formats used, and gave rise to, music and dance. Many famous composers and musicians had their careers launched in the theatres, and many famous compositions got their first airing on the stage. In addition to staging some European operas and operettas, Cuban composers gradually developed ideas that better suited their audience. Zarzuela

Zarzuela is a small-scale light operetta format. Starting off with imported Spanish content (List of zarzuela composers), it developed into a running commentary on Cuba's social and political events and problems. Zarzuela has the distinction of providing Cuba's first recordings: the soprano Chalía Herrera (1864–1968) made, outside Cuba, the first recordings by a Cuban artist. She recorded numbers from the zarzuela ''Cádiz (zarzuela), Cádiz'' in 1898 on unnumbered Gianni Bettini, Bettini cylinders. Zarzuela reached its peak in the first half of the 20th century. A string of front-rank composers such as

Zarzuela reached its peak in the first half of the 20th century. A string of front-rank composers such as Bufo theatre

Cuban ''bufo theatre'' is a form of comedy, ribald and satirical, with stock figures imitating types that might be found anywhere in the country. Bufo had its origin around 1800-15 as an older form, ''tonadilla'', began to vanish from Havana. Francisco Covarrubias the 'caricaturist' (1775–1850) was its creator. Gradually, the comic types threw off their European models and became more and more creolized and Cuban. Alongside, the music followed. Argot from slave barracks and poor barrios found its way into lyrics that are those of theOther theatrical forms

Vernacular theatre of various types often includes music. Formats rather like the British Music Hall, or the American Vaudeville, still occur, where an audience is treated to a potpourri of singers, comedians, bands, sketches and speciality acts. Even in cinemas during the silent movies, singers and instrumentalists appeared in the interval, and a pianist played during the films. Bola de Nieve and María Teresa Vera played in cinemas in their early days. Burlesque was also common in Havana before 1960.The Black Curros (Negros Curros)

In reference to the emergence of the Guaracha and, at a later time, also of the Urban Rumba in Havana and Matanzas, it is important to mention an important and picturesque social sector called Black Curros (Negros Curros). Composed of free blacks that had arrived from Seville on an undetermined date, this group was integrated to the population of free blacks and mulattos that lived in the marginal zones of the city of Havana.

José Victoriano Betancourt a Cuban "costumbrista" writer from the 19th century described them as follows: "they [the curros] had a peculiar aspect, and was enough to look at them to recognize them as curros: their long hunks of kinky braids, falling over their face and neck like big millipedes, their teeth cut (sharp and pointed) to the carabalí style, their fine embroidered cloth shirts, their pants, almost always white, or with colored stripes, narrow at the waist and very wide in the legs; the canvas shoes, cut low with silver buckles, the short jacket with pointed tail, the exaggerated straw hat, with black hanging silk tassles, and the thick gold hoops that they wore in their ears, from which they hung harts and padlocks of the same metal, forming an ornament that only they wear; ... those were the curros of El Manglar (The mangrove neighborhood)."

The curro was dedicated to laziness, theft and procuring, while his companion, the curra, also called "mulata de rumbo", exercised the prostitution in Cuba. According to Carlos Noreña, she was well known for the use of burato shawls of meticulous work and plaited fringes, for which they used to pay from nine to ten ounces of gold", as well as by the typical clacking (chancleteo) they produced with their wooden slippers.

But the Curros also provided entertainment, including songs and dances to the thousands of Spanish men that came to the Island every year in the ships that followed the "Carrera de Indias", a route established by the Spanish Crown for their galleons in order to avoid attacks from pirates and privateers, and stayed for months until they returned to the Port of Seville.

Being subject to the influence of both the Spanish and the African culture from birth, they are supposed to have played an important role in the creolization of the Spanish song-dances original proto-type (copla-estribillo) that originated the Cuban Guaracha. The Black curro and the Mulata de Rumbo (Black Curra) disappeared since the mid-19th century by integrating to the Havana general population, but their picturesque images survived in social prototypes manifested in the characters of the Bufo Theater.

The famous "Mulatas de Rumbo" (mulatto characters) Juana Chambicú and María La O, as well as the black "cheches" (bullies) José Caliente "who rips in half those who oppose him," Candela, "negrito that flies and cuts with the knife," as well as the Black Curro Juán Cocuyo, were strongly linked to the characteristic image of the Black Curro and to the ambiance of the Guaracha and the Rumba.

In reference to the emergence of the Guaracha and, at a later time, also of the Urban Rumba in Havana and Matanzas, it is important to mention an important and picturesque social sector called Black Curros (Negros Curros). Composed of free blacks that had arrived from Seville on an undetermined date, this group was integrated to the population of free blacks and mulattos that lived in the marginal zones of the city of Havana.

José Victoriano Betancourt a Cuban "costumbrista" writer from the 19th century described them as follows: "they [the curros] had a peculiar aspect, and was enough to look at them to recognize them as curros: their long hunks of kinky braids, falling over their face and neck like big millipedes, their teeth cut (sharp and pointed) to the carabalí style, their fine embroidered cloth shirts, their pants, almost always white, or with colored stripes, narrow at the waist and very wide in the legs; the canvas shoes, cut low with silver buckles, the short jacket with pointed tail, the exaggerated straw hat, with black hanging silk tassles, and the thick gold hoops that they wore in their ears, from which they hung harts and padlocks of the same metal, forming an ornament that only they wear; ... those were the curros of El Manglar (The mangrove neighborhood)."

The curro was dedicated to laziness, theft and procuring, while his companion, the curra, also called "mulata de rumbo", exercised the prostitution in Cuba. According to Carlos Noreña, she was well known for the use of burato shawls of meticulous work and plaited fringes, for which they used to pay from nine to ten ounces of gold", as well as by the typical clacking (chancleteo) they produced with their wooden slippers.

But the Curros also provided entertainment, including songs and dances to the thousands of Spanish men that came to the Island every year in the ships that followed the "Carrera de Indias", a route established by the Spanish Crown for their galleons in order to avoid attacks from pirates and privateers, and stayed for months until they returned to the Port of Seville.

Being subject to the influence of both the Spanish and the African culture from birth, they are supposed to have played an important role in the creolization of the Spanish song-dances original proto-type (copla-estribillo) that originated the Cuban Guaracha. The Black curro and the Mulata de Rumbo (Black Curra) disappeared since the mid-19th century by integrating to the Havana general population, but their picturesque images survived in social prototypes manifested in the characters of the Bufo Theater.

The famous "Mulatas de Rumbo" (mulatto characters) Juana Chambicú and María La O, as well as the black "cheches" (bullies) José Caliente "who rips in half those who oppose him," Candela, "negrito that flies and cuts with the knife," as well as the Black Curro Juán Cocuyo, were strongly linked to the characteristic image of the Black Curro and to the ambiance of the Guaracha and the Rumba.

Rumba

The word Rumba is an abstract term that has been applied with different purposes to a wide variety of subjects for a very long time. From a semantic point of view, the term rumba is included in a group of words with similar meaning such as conga, milonga, bomba, tumba, samba, bamba, mambo, tambo, tango, cumbé, cumbia and candombe. All of them denote a Congolese origin due to the utilization of sound combinations such as, mb, ng and nd, that are typical of the Niger-Congo linguistic complex. Maybe the most ancient and general of its meanings is that of a feast or "holgorio". As far as the second half of the 19th century, this word can be found used several times to represent a feast in a short story called "La mulata de rumbo", from the Cuban folklorist Francisco de Paula Gelabert: "I have more enjoyment and fun in a rumbita with those of my color and class", or "Leocadia was going to bed, as I was telling you, nothing less than at twelve noon, when one of his friends from the rumbas arrived, along with another young man that he wanted to introduce to her." According to Alejo Carpentier "it is significant that the word rumba have passed to the Cuban language as a synonym of holgorio, lewd dance, merrymaking with low class women (mujeres del rumbo)." As an example, In the case of the Yuka, Makuta and Changüí feasts in Cuba, as well as the Milonga and the Tango in Argentina, the word rumba was originally utilized to nominate a festive gathering; and after some time it was used to name the musical and dance genres that were played at those gatherings. Among many others, some ultizations of the term "rumba include a cover-all term for faster Cuban music which started in the early 1930s with ''The Peanut Vendor''. This term was replaced during the 1970s by Salsa (music), salsa, which is also a cover-all term for marketing the Cuban music and other Hispano-Caribbean genres to non-Cubans. In the international Latin-American dance syllabus rumba is a misnomer for the slow Cuban rhythm more accurately called bolero-son.Rumba and guaracha

Some scholars have pointed out that in reference to the utilization of the terms rumba and guaracha, there is possibly a case of synonymy, or the use of two different words to denominate the same thing. According to María Teresa Linares: "during the first years of the 20th century, there were used at the end of the vernacular (Bufo) theater plays some musical fragments that the authors sang, and that were called closing rumba (rumba final)" and she continues explaining that those (rumbas) "were certainly guarachas." The musical pieces used to close those plays may have been indistinctly called rumbas or guarachas, because those terms didn't denote any generic or structural difference between them. Linares also said in reference to this subject: "Some recordings of guarachas and rumbas have been preserved that do not differentiate between them in the guitar parts – when it was a small group, duo or trio, or by the theater orchestra or a piano. The labels of the recordings stated: dialogue and rumba (diálogo y rumba)."Urban rumba

Urban rumba (also called Rumba (de solar o de cajón)), is an amalgamation of several African drumming and dance traditions, combined with Spanish influences. According to Cuban musicologist Argeliers León: "In the feast that constituted a rumba concurred, therefore, determined African contributions, but also converged other elements from Hispanic roots, that were already incorporated to the expressions that appeared in the new population emerging in the Island."

Rumba (de solar o de cajón) is a secular musical style from the docks and the less prosperous areas of Havana and

Urban rumba (also called Rumba (de solar o de cajón)), is an amalgamation of several African drumming and dance traditions, combined with Spanish influences. According to Cuban musicologist Argeliers León: "In the feast that constituted a rumba concurred, therefore, determined African contributions, but also converged other elements from Hispanic roots, that were already incorporated to the expressions that appeared in the new population emerging in the Island."

Rumba (de solar o de cajón) is a secular musical style from the docks and the less prosperous areas of Havana and  From the many rumba styles that began to appear during the end of the 19th century called "Spanish times" (Tiempo'españa), such as tahona, jiribilla, palatino and resedá, three basic Rumba forms have survived: the Cuban rumba#Columbia, Columbia, the guaguancó and the yambú. The Columbia, played in 6/8 time, is often as a solo dance performed only by a male performer. It is fast and swift and also includes aggressive and acrobatic moves. The guaguancó is danced by a pair of one man and one woman. The dance simulates the man's pursuit of the woman. The yambú, now a relic, featured a burlesque imitation of an old man walking with a stick. All forms of rumba are accompanied by song or chants.

Rumba (de solar o de cajón) is today a fossil genre usually seen in Cuba in performances of professional groups. There are also amateur groups based on ''Casas de Cultura'' (Culture Centers), and on work groups. Like all aspects of life in Cuba, dance and music are organised by the state through Ministries and their various committees.

From the many rumba styles that began to appear during the end of the 19th century called "Spanish times" (Tiempo'españa), such as tahona, jiribilla, palatino and resedá, three basic Rumba forms have survived: the Cuban rumba#Columbia, Columbia, the guaguancó and the yambú. The Columbia, played in 6/8 time, is often as a solo dance performed only by a male performer. It is fast and swift and also includes aggressive and acrobatic moves. The guaguancó is danced by a pair of one man and one woman. The dance simulates the man's pursuit of the woman. The yambú, now a relic, featured a burlesque imitation of an old man walking with a stick. All forms of rumba are accompanied by song or chants.

Rumba (de solar o de cajón) is today a fossil genre usually seen in Cuba in performances of professional groups. There are also amateur groups based on ''Casas de Cultura'' (Culture Centers), and on work groups. Like all aspects of life in Cuba, dance and music are organised by the state through Ministries and their various committees.

Coros de Clave

Coros de Clave were popular choral groups that emerged at the beginning of the 20th century in Havana and other Cuban cities. The Cuban government only allowed black people, slaves or free, to cultivate their cultural traditions within the boundaries of certain mutual aid societies, which were founded during the 16th century. According to David H. Brown, those societies, called Cabildos, "provided in times of sickness and death, held masses for deceased members, collected funds to buy nation-brethren out of slavery, held regular dances and diversions on Sundays and feast days, and sponsored religious masses, processions and dancing carnival groups (now called comparsas) around the annual cycle of Catholic festival days." Within the Cabildos of certain neighborhoods from Havana,Rural rumba

In a similar way as the first Spanish song-dances spread from the cities to the countryside, also the characteristics of the Cuban Guaracha, that enjoyed great popularity in Havana, began to spread to the rural areas in an undetermined time during the 19th century. This process was not difficult at all if one considers how close one to the other were the urban and the rural areas in Cuba at that time. That was why the Cuban peasants (guajiros) began to include in their parties called "guateques" or "changüís", and in feasts such as the "fiestas patronales" (patron saint celebrations) and the "parrandas", some Rumbitas (little rumbas) that were very similar to the urban Guarachas, which binary meter contrasted with the ternary beat of their traditional "tonadas" and "zapateos".

Those little rural rumbas have been called by renowned musicologist Danilo Orozco "proto-sones", "soncitos primigenios", "rumbitas", "nengones"or "marchitas," and some of them, such as: Caringa, Papalote, Doña Joaquina, Anda Pepe and the Tingotalango have been preserved until the present time.

The Rumbitas were considered as Proto-sones (primeval Sones), because of the evident analogy that its structural components show with the Son, which emerged in Havana during the first decades of the 20th century. The Rumbitas may be considered as the original prototype of this popular genre.

According to musicologist Virtudes Feliú, those Rumbitas appeared in cities and towns throughout the entire territory of the Island, such as: Ciego de Ávila, Sancti Espíritus, Cienfuegos, Camagüey, Puerta de Golpe in Pinar del Río and Bejucal in Havana, as well as Remedios in Villa Clara and Isla de Pinos (Pines Island).

There are many references to the Cuban Independence Wars (1868-1898), related to the rural Rumbitas, in the Eastern region of the country as well as in the Western region and Isla de Pinos, which suggest that their emergence took place approximately during the second half of the 19th century.

The rural Rumbitas included a greater number of African characteristics in comparison with the Cuban Guaracha, due to the gradual integration of free Afro-Cuban citizens to the rural environment.

Since the 16th century, thanks to a government approved program called "manumisión", the black slaves were allowed to pay for their freedom with their own savings. Therefore, a larger number of free blacks were dedicated to the manual labors in the fields than in the cities and some of them were also able to become proprietaries of land and slaves.

In a similar way as the first Spanish song-dances spread from the cities to the countryside, also the characteristics of the Cuban Guaracha, that enjoyed great popularity in Havana, began to spread to the rural areas in an undetermined time during the 19th century. This process was not difficult at all if one considers how close one to the other were the urban and the rural areas in Cuba at that time. That was why the Cuban peasants (guajiros) began to include in their parties called "guateques" or "changüís", and in feasts such as the "fiestas patronales" (patron saint celebrations) and the "parrandas", some Rumbitas (little rumbas) that were very similar to the urban Guarachas, which binary meter contrasted with the ternary beat of their traditional "tonadas" and "zapateos".

Those little rural rumbas have been called by renowned musicologist Danilo Orozco "proto-sones", "soncitos primigenios", "rumbitas", "nengones"or "marchitas," and some of them, such as: Caringa, Papalote, Doña Joaquina, Anda Pepe and the Tingotalango have been preserved until the present time.

The Rumbitas were considered as Proto-sones (primeval Sones), because of the evident analogy that its structural components show with the Son, which emerged in Havana during the first decades of the 20th century. The Rumbitas may be considered as the original prototype of this popular genre.

According to musicologist Virtudes Feliú, those Rumbitas appeared in cities and towns throughout the entire territory of the Island, such as: Ciego de Ávila, Sancti Espíritus, Cienfuegos, Camagüey, Puerta de Golpe in Pinar del Río and Bejucal in Havana, as well as Remedios in Villa Clara and Isla de Pinos (Pines Island).

There are many references to the Cuban Independence Wars (1868-1898), related to the rural Rumbitas, in the Eastern region of the country as well as in the Western region and Isla de Pinos, which suggest that their emergence took place approximately during the second half of the 19th century.

The rural Rumbitas included a greater number of African characteristics in comparison with the Cuban Guaracha, due to the gradual integration of free Afro-Cuban citizens to the rural environment.

Since the 16th century, thanks to a government approved program called "manumisión", the black slaves were allowed to pay for their freedom with their own savings. Therefore, a larger number of free blacks were dedicated to the manual labors in the fields than in the cities and some of them were also able to become proprietaries of land and slaves.

Characteristics of the rural rumba

One of the most salient characteristics of the rural Rumbitas was its own form, very similar to the African typical song structure. In this case, the entire piece was based on a single musical fragment or phrase of short duration that was repeated, with some variations, time and time again; often alternating with a choir. This style was called "Montuno" (literally "from the countryside") due to its rural origin.

One of the most salient characteristics of the rural Rumbitas was its own form, very similar to the African typical song structure. In this case, the entire piece was based on a single musical fragment or phrase of short duration that was repeated, with some variations, time and time again; often alternating with a choir. This style was called "Montuno" (literally "from the countryside") due to its rural origin.

Another characteristic of the new genre was the superposition of different rhythmic patterns simultaneously executed, similarly to the way it is utilized in the Urban Rumba, which is also a common trait of the African musical tradition. Those layers or "franjas de sonoridades" according to Argeliers León, were assigned to different instruments that were gradually incorporated to the group. Therefore, the ensemble grew from the traditional Tiple and Güiro, to a one that included: guitar, "bandurria", Cuban lute, claves, and other instruments such as the"tumbandera", the "marímbula", the "botija", the bongoes, the common "machete" (cutlass) and the accordion.

Some important musical functions were assigned to the sonority layers, such as the: "Time Line" or Clave Rhythm performed by the claves, a "1-eighth note + 2-sixteenth notes" rhythm played by the güiro or the machete, the patterns of the "guajeo" by the Tres (instrument), the improvisation on the bongoes and the anticipated bass on the "tumbandera" or the "botija".

Another characteristic of the new genre was the superposition of different rhythmic patterns simultaneously executed, similarly to the way it is utilized in the Urban Rumba, which is also a common trait of the African musical tradition. Those layers or "franjas de sonoridades" according to Argeliers León, were assigned to different instruments that were gradually incorporated to the group. Therefore, the ensemble grew from the traditional Tiple and Güiro, to a one that included: guitar, "bandurria", Cuban lute, claves, and other instruments such as the"tumbandera", the "marímbula", the "botija", the bongoes, the common "machete" (cutlass) and the accordion.

Some important musical functions were assigned to the sonority layers, such as the: "Time Line" or Clave Rhythm performed by the claves, a "1-eighth note + 2-sixteenth notes" rhythm played by the güiro or the machete, the patterns of the "guajeo" by the Tres (instrument), the improvisation on the bongoes and the anticipated bass on the "tumbandera" or the "botija".

Proto-son

The origin of the Cuban son can be traced to the rural rumbas, called proto-sones (primeval sones) by musicologist Danilo Orozco. They show, in a partial or embryonic form, all the characteristics that at a later time were going to identify the Son style: The repetition of a phrase called ''montuno'', the clave pattern, a rhythmic counterpoint between different layers of the musical texture, the ''guajeo'' from the Tres, the rhythms from the guitar, the bongoes and the double bass and the call and response (music), call and response style between soloist and choir. According to Radamés Giro: at a later time the refrain (estribillo) or ''montuno'' was tied to a quatrain (cuarteta – copla) called ''regina'', which was how the peasants from the Eastern side of the country called the quatrain. In this way, the structure ''refrain–quatrain–refrain'' appears at a very early stage in the ''Son Oriental,'' like in one of the most ancient Sones called "Son de Máquina" (Machine Son) which comprises three ''reginas'' with its correspondent refrains. During an investigative project about the Valera-Miranda family (old Soneros) conducted by Danilo Orozco in the region of Guantánamo, he recorded a sample of Nengón, which is considered an ancestor of the Changüí. It shows the previously mentioned ''refrain–quatrain–refrain'' structure. In this case, the several repetitions of the refrain constitute a true "montuno." Refrain: Yo he nacido para ti nengón, yo he nacido para ti nengón, yo he nacido para ti Nengón... (I was born for you Nengón...)Nengón

The "Nengón" is considered a Proto-Son, precursor of the Changüí and also of the Oriental Son. Its main characteristic is the alternance of improvised verses between a soloist and a choir. The Nengón is played with Tres, Guitar, Güiro and Tingotalango or Tumbandera.Changüí

Changüí is a type of son from the eastern provinces (area ofSucu-Sucu

We can also find in Isla de Pinos, at the opposite Western side of the Island a primeval Proto-Son called Sucu-Sucu, which also shows the same structure of the Oriental Proto-Sones. According to Maria Teresa Linares, In the Sucu-Sucu the music is similar to a Son Montuno in its formal, melodic, instrumental and harmonic structure. A soloist alternates with a choir and improvises on a quatrain or a "décima." The instrumental section is introduced by the Tres, gradually joined by the other instruments. The introduction of eight measures is followed by the refrain by the choir that alternates with the soloist several times. An urban legend claims that the name "Sucu Sucu" came from the grandmother of one of the local musicians in la Isla de Juventud. The band was playing in the patio, and the dances were dancing while shuffling their feet on the sandy floor. The grandmother came out of the house to say "Please stop making noise with all that sucu sucu," referring to the sound of shuffling feet on a sandy floor. The legend claim that the name stuck, and the music the dancers were dancing too started to be named "Sucu Sucu".Trova

In the 19th century, Santiago de Cuba became the focal point of a group of itinerant musicians, troubadours, who moved around earning their living by singing and playing the guitar. They were of great importance as composers, and their songs have been transcribed for all genres of Cuban music Pepe Sánchez (trova), Pepe Sánchez, born José Sánchez (1856–1918), is known as the father of the ''trova'' style and the creator of the Cuban bolero.Orovio, Helio 1995. ''El bolero latino''. La Habana. He had no formal training in music. With remarkable natural talent, he composed numbers in his head and never wrote them down. As a result, most of these numbers are now lost for ever, though some two dozen or so survive because friends and disciples transcribed them. His first bolero, ''Tristezas'', is still remembered today. He also created advertisement jingles before radio was born. He was the model and teacher for the great trovadores who followed him. The first, and one of the longest-lived, was Sindo Garay (1867–1968). He was an outstanding composer of trova songs, and his best have been sung and recorded many times. Garay was also musically illiterate – in fact, he only taught himself the alphabet at 16 – but in his case not only were scores recorded by others, but there are recordings. Garay settled in Havana in 1906, and in 1926 joined Rita Montaner and others to visit Paris, spending three months there. He broadcast on radio, made recordings and survived into modern times. He used to say "Not many men have shaken hands with both José Martí and

The first, and one of the longest-lived, was Sindo Garay (1867–1968). He was an outstanding composer of trova songs, and his best have been sung and recorded many times. Garay was also musically illiterate – in fact, he only taught himself the alphabet at 16 – but in his case not only were scores recorded by others, but there are recordings. Garay settled in Havana in 1906, and in 1926 joined Rita Montaner and others to visit Paris, spending three months there. He broadcast on radio, made recordings and survived into modern times. He used to say "Not many men have shaken hands with both José Martí and Bolero

This is a song and dance form quite different from its Spanish namesake. It originated in the last quarter of the 19th century with the founder of the traditional trova, Pepe Sánchez (trova), Pepe Sánchez. He wrote the first bolero, ''Tristezas'', which is still sung today. The bolero has always been a staple part of the trova musician's repertoire. Originally, there were two sections of 16 bars in 2/4 time separated by an instrumental section on the Spanish guitar called the ''pasacalle''. The bolero proved to be exceptionally adaptable, and led to many variants. Typical was the introduction of sychopation leading to the bolero-moruno, bolero-beguine, bolero-mambo, bolero-cha. The bolero-son became for several decades the most popular rhythm for dancing in Cuba, and it was this rhythm that the international dance community picked up and taught as the wrongly-named 'rumba'.

The Cuban bolero was exported all over the world, and is still popular. Leading composers of the bolero were Sindo Garay, Rosendo Ruiz, Carlos Puebla, and Agustín Lara (Mexico).

Originally, there were two sections of 16 bars in 2/4 time separated by an instrumental section on the Spanish guitar called the ''pasacalle''. The bolero proved to be exceptionally adaptable, and led to many variants. Typical was the introduction of sychopation leading to the bolero-moruno, bolero-beguine, bolero-mambo, bolero-cha. The bolero-son became for several decades the most popular rhythm for dancing in Cuba, and it was this rhythm that the international dance community picked up and taught as the wrongly-named 'rumba'.

The Cuban bolero was exported all over the world, and is still popular. Leading composers of the bolero were Sindo Garay, Rosendo Ruiz, Carlos Puebla, and Agustín Lara (Mexico).

Canción

''Canción'' means 'song' in Spanish. It is a popular genre of Latin American music, particularly in Cuba, where many of the compositions originate. Its roots lie in Spanish, French and Italian popular song forms. Originally highly stylized, with "intricate melodies and dark, enigmatic and elaborate lyrics" The canción was democratized by the trova movement in the latter part of the 19th century, when it became a vehicle for the aspirations and feelings of the population. Canción gradually fused with other forms of Cuban music, such as the bolero.Tropical waltz

TheSon

Cuban jazz

The history of jazz in Cuba was obscured for many years, but it has become clear that its history in Cuba is virtually as long as its history in the US.Giro Radamés 2007. ''Diccionario enciclopédico de la música en Cuba''. La Habana. Extensive essay on Cuban jazz in vol 2, p261–269.Roberts, John Storm 1979. ''The Latin tinge: the influence of Latin American music on the United States''. Oxford.Roberts, John Storm 1999. ''Latin jazz: the first of the fusions, 1880s to today''. Schirmer, N.Y.Isabelle Leymarie 2002. ''Cuban fire: the story of salsa and Latin jazz''. Continuum, London.Schuller, Gunther 1986. ''Early jazz: its roots and musical development''. Oxford, N.Y. Much more is now known about Early Cuban bands#Early Cuban jazz bands, early Cuban jazz bands, but a full assessment is plagued by the lack of recordings. Migrations and visits to and from the US and the mutual exchange of recordings and sheet music kept musicians in the two countries in touch. In the first part of the 20th century, there were close relations between musicians in Cuba and those inEarly Cuban jazz bands

The Jazz Band Sagua was founded in Sagua la Grande in 1914 by Pedro Stacholy (director & piano). Members: Hipólito Herrera (trumpet); Norberto Fabelo (cornet); Ernesto Ribalta (flute & sax); Humberto Domínguez (violin); Luciano Galindo (trombone); Antonio Temprano (tuba); Tomás Medina (drum kit); Marino Rojo (güiro). For fourteen years they played at the ''Teatro Principal de Sagua''. Stacholy studied under Antonio Fabré in Sagua, and completed his studies in New York, where he stayed for three years.Giro Radamés 2007. ''Diccionario enciclopédico de la música en Cuba''. La Habana. vol 2, p. 261.

The Cuban Jazz Band was founded in 1922 by Jaime Prats in Havana. The personnel included his son Rodrigo Prats on violin, the great flautist Alberto Socarrás on flute and saxophone and Pucho Jiménez on slide trombone. The line-up would probably have included double bass, kit drum, banjo, cornet at least. Earlier works cited this as the first jazz band in Cuba, but evidently there were earlier groups.

In 1924 Moisés Simons (piano) founded a group which played on the roof garden of the Plaza Hotel in Havana, and consisted of piano, violin, two saxes, banjo, double bass, drums and timbales. Its members included Virgilio Diago (violin); Alberto Soccarás (alto saz, flute); José Ramón Betancourt (tenor sax); Pablo O'Farrill (d. bass). In 1928, still at the same venue, Simons hired Julio Cueva, a famous trumpeter, and Enrique Santiesteban, a future media star, as vocalist and drummer. These were top instrumentalists, attracted by top fees of $8 a day.p28

During the 1930s, several bands played Jazz in Havana, such as those of Armando Romeu, Isidro Pérez, Chico O'Farrill and Germán Lebatard. Their most important contribution was its own instrumental format itself, which introduced the typical Jazz sonority to the Cuban audience. Another important element within this process were the arrangements of Cuban musicians such as Romeu, O'Farrill, Bebo Valdés, Peruchín Jústiz and Leopoldo "Pucho" Escalante.

The Jazz Band Sagua was founded in Sagua la Grande in 1914 by Pedro Stacholy (director & piano). Members: Hipólito Herrera (trumpet); Norberto Fabelo (cornet); Ernesto Ribalta (flute & sax); Humberto Domínguez (violin); Luciano Galindo (trombone); Antonio Temprano (tuba); Tomás Medina (drum kit); Marino Rojo (güiro). For fourteen years they played at the ''Teatro Principal de Sagua''. Stacholy studied under Antonio Fabré in Sagua, and completed his studies in New York, where he stayed for three years.Giro Radamés 2007. ''Diccionario enciclopédico de la música en Cuba''. La Habana. vol 2, p. 261.

The Cuban Jazz Band was founded in 1922 by Jaime Prats in Havana. The personnel included his son Rodrigo Prats on violin, the great flautist Alberto Socarrás on flute and saxophone and Pucho Jiménez on slide trombone. The line-up would probably have included double bass, kit drum, banjo, cornet at least. Earlier works cited this as the first jazz band in Cuba, but evidently there were earlier groups.

In 1924 Moisés Simons (piano) founded a group which played on the roof garden of the Plaza Hotel in Havana, and consisted of piano, violin, two saxes, banjo, double bass, drums and timbales. Its members included Virgilio Diago (violin); Alberto Soccarás (alto saz, flute); José Ramón Betancourt (tenor sax); Pablo O'Farrill (d. bass). In 1928, still at the same venue, Simons hired Julio Cueva, a famous trumpeter, and Enrique Santiesteban, a future media star, as vocalist and drummer. These were top instrumentalists, attracted by top fees of $8 a day.p28

During the 1930s, several bands played Jazz in Havana, such as those of Armando Romeu, Isidro Pérez, Chico O'Farrill and Germán Lebatard. Their most important contribution was its own instrumental format itself, which introduced the typical Jazz sonority to the Cuban audience. Another important element within this process were the arrangements of Cuban musicians such as Romeu, O'Farrill, Bebo Valdés, Peruchín Jústiz and Leopoldo "Pucho" Escalante.

Afro-Cuban jazz

Afro-Cuban jazz is the earliest form of Latin jazz and mixes Afro-Cuban clave-based rhythms with jazz harmonies and techniques of improvisation. Afro-Cuban jazz first emerged in the early 1940s, with the Cuban musicians Mario Bauza and Frank Grillo "Machito" in the band Machito and his Afro-Cubans, based in New York City. In 1947 the collaborations of bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie with Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo brought Afro-Cuban rhythms and instruments, most notably the tumbadora and the bongo, into the East Coast jazz scene. Early combinations of jazz with Cuban music, such as Dizzy's and Pozo's "Manteca" and Charlie Parker's and Machito's "Mangó Mangüé", were commonly referred to as "Cubop", short for Cuban bebop. During its first decades, the Afro-Cuban jazz movement was stronger in the United States than in Cuba itself. In the early 1970s, the Orquesta Cubana de Música Moderna and later Irakere brought Afro-Cuban jazz into the Cuban music scene, influencing new styles such as songo.

Afro-Cuban jazz is the earliest form of Latin jazz and mixes Afro-Cuban clave-based rhythms with jazz harmonies and techniques of improvisation. Afro-Cuban jazz first emerged in the early 1940s, with the Cuban musicians Mario Bauza and Frank Grillo "Machito" in the band Machito and his Afro-Cubans, based in New York City. In 1947 the collaborations of bebop innovator Dizzy Gillespie with Cuban percussionist Chano Pozo brought Afro-Cuban rhythms and instruments, most notably the tumbadora and the bongo, into the East Coast jazz scene. Early combinations of jazz with Cuban music, such as Dizzy's and Pozo's "Manteca" and Charlie Parker's and Machito's "Mangó Mangüé", were commonly referred to as "Cubop", short for Cuban bebop. During its first decades, the Afro-Cuban jazz movement was stronger in the United States than in Cuba itself. In the early 1970s, the Orquesta Cubana de Música Moderna and later Irakere brought Afro-Cuban jazz into the Cuban music scene, influencing new styles such as songo.

Diversification and popularization

Cuban music enters the United States

In 1930, Don Azpiazú had the first million-selling record of Cuban music: ''The Peanut Vendor'' (El Manisero), with Antonio Machín as the singer. This number had been orchestrated and included in N.Y. theatre by Azpiazú before recording, which no doubt helped with the publicity. The1940s and '50s

In the 1940s, Chano Pozo formed part of the bebop revolution inThe big band era

The big band era arrived in Cuba in the 1940s, and became a dominant format that survives. Two great arranger-bandleaders deserve special credit for this, Armando Romeu Jr. and Damaso Perez Prado. Armando Romeu Jr. led the ''Tropicana Club, Tropicana Cabaret'' orchestra for 25 years, starting in 1941. He had experience playing with visiting American jazz groups as well as a complete mastery of Cuban forms of music. In his hands the Tropicana presented not only Afrocuban and other popular Cuban music, but also Cuban jazz and American big band compositions. Later he conducted the ''Orquesta Cubana de Musica Moderna''.Acosta, Leonardo 2003. ''Cubano be, cubano bop: one hundred years of jazz in Cuba''. Transl. Daniel S. Whitesell. Smithsonian, Washington, D.C. Damaso Perez Prado had a number of hits, and sold more 78s than any other Latin music of the day. He took over the role of pianist/arranger for the Orquesta ''Casino de la Playa'' in 1944, and immediately began introducing new elements into its sound. The orchestra began to sound more Afrocuban, and at the same time Prado took influences from Stravinsky, Stan Kenton and elsewhere. By the time he left the orchestra in 1946 he had put together the elements of his big band mambo.: "Above all, we must point out the work of Perez Prado as an arranger, or better yet, composer and arranger, and his clear influence on most other Cuban arrangers from then on."p86 Benny Moré, considered by many as the greatest Cuban singer of all time, was in his heyday in the 1950s. He had an innate musicality and fluid tenor voice, which he colored and phrased with great expressivity. Although he could not read music, Moré was a master of all the genres, including son montuno, mambo, guaracha, guajira, cha cha cha, afro, canción, guaguancó, and bolero. His orchestra, the Banda Gigante, and his music, was a development – more flexible and fluid in style – of the Perez Prado orchestra, which he sang with in 1949–1950.Cuban music in the US

Three great innovations based on Cuban music hit the US after World War II: the first was Cubop, the latest latin jazz fusion. In this, Mario Bauza and the Machito orchestra on the Cuban side and Dizzy Gillespie on the American side were prime movers. The rumbustious conguero Chano Pozo was also important, for he introduced jazz musicians to basic Cuban rhythms. Cuban jazz has continued to be a significant influence. The mambo first entered the United States around 1950, though ideas had been developing in Cuba and Mexico City for some time. The mambo as understood in the United States and Europe was considerably different from the danzón-mambo of Orestes "Cachao" Lopez, which was a danzon with extra syncopation in its final part. The mambo—which became internationally famous—was a big band product, the work of Perez Prado, who made some sensational recordings for RCA in their new recording studios in Mexico City in the late 1940s. About 27 of those recordings had Benny Moré as the singer, though the best sellers were mainly instrumentals. The big hits included "Que rico el mambo" (Mambo Jambo); "Mambo No. 5"; "Mambo #8"; "Cherry Pink (and Apple Blossom White)". The later (1955) hit "Patricia (1955 song), Patricia" was a mambo/rock fusion. Mambo of the Prado kind was more a descendant of the son and the guaracha than the danzón. In the U.S. the mambo craze lasted from about 1950 to 1956, but its influence on the bugaloo and Salsa (music), salsa that followed it was considerable. Violinist Enrique Jorrín invented the chachachá in the early 1950s. This was developed from the danzón by increased syncopation. The chachachá became more popular outside Cuba when the big bands of Perez Prado and Tito Puente produced arrangements that attracted American and European audiences.

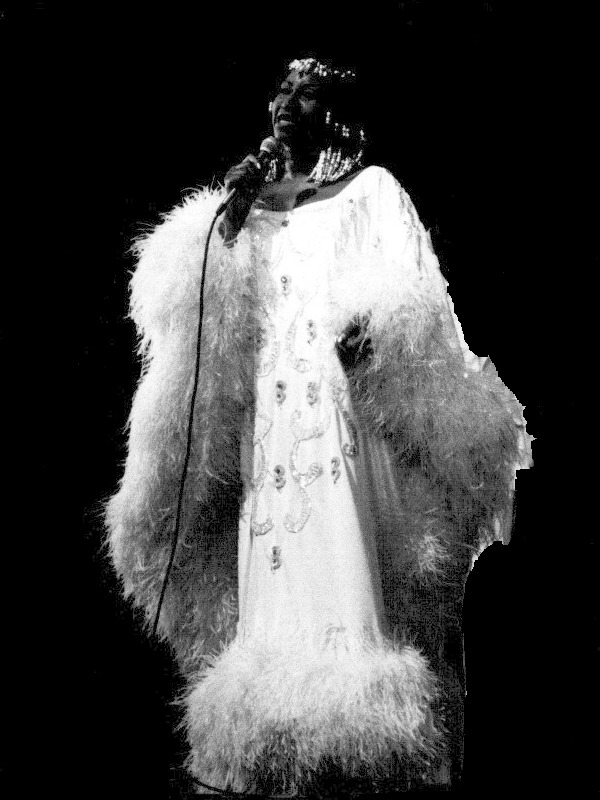

Along with "Nuyoricans" Ray Barretto and Tito Puente and others, several waves of Cuban immigrants introduced their ideas into US music. Among these was Celia Cruz, a

Violinist Enrique Jorrín invented the chachachá in the early 1950s. This was developed from the danzón by increased syncopation. The chachachá became more popular outside Cuba when the big bands of Perez Prado and Tito Puente produced arrangements that attracted American and European audiences.

Along with "Nuyoricans" Ray Barretto and Tito Puente and others, several waves of Cuban immigrants introduced their ideas into US music. Among these was Celia Cruz, a Mambo

Mambo (music), Mambo is a musical genre and dance style that developed originally in Cuba. The word "Mambo", similarly to other afroamerican musical denominations as conga, milonga, bomba, tumba, samba, bamba, bamboula, tambo, tango, cumbé, cumbia and candombe, denote an African origin, particularly from Congo, due to the presence of certain characteristic combinations of sounds, such as mb, ng and nd, which belong to the Niger-Congo linguistic complex. The earliest roots of the Cuban Mambo can be traced to the "Danzón de Nuevo Ritmo" (Danzón with a new rhythm) made popular by the orchestra "Arcaño y sus Maravillas" conducted by famous bandleader Antonio Arcaño. He was the first to denominate a section of the popular CubanChachachá

Chachachá is a genre of Cuban music. It has been a popular dance music which developed from the Danzón-mambo in the early 1950s, and became widely popular throughout the entire world.

Chachachávis a Cuban music genre whose creation has been traditionally attributed to Cuban composer and violinist Enrique Jorrín, which began his career playing for the Charanga (Cuba), charanga band Orquesta América.

According to the testimony of Enrique Jorrín, he composed some "Danzones" in which the musician of the orchestra had to sing short refrains, and this style was very successful. In the Danzón "Constancia" he introduced some montunos and the audience was motivated to join in singing the refrains. Jorrín also asked the members of the orchestra to sing in unison so the lyrics may be heard more clearly and achieve a greater impact in the audience. That way of singing also helped to mask the poor singing skills of the orchestra members.

Since its inception, Chachachá music had a close relationship with the dancer's steps. The well-known name Chachachá came into being with the help of the dancers at the Silver Star Club in Havana. When the dance was coupled to the rhythm of the music, it became evident that the dancer's feet were making a peculiar sound as they grazed the floor on three successive beats. It was like an onomatopoeia that sounded as: Chachachá. From this peculiar sound, a music genre was born which motivated people from around the world to dance at its catchy rhythm.

According to Olavo ALén: "During the 1950s, Chachachá maintained its popularity thanks to the efforts of many Cuban composers who were familiar with the technique of composing ''Danzón, danzones'' and who unleashed their creativity on the Chachachá", such as Rosendo Ruiz, Jr. ("Los Marcianos" and "Rico Vacilón"), Félix Reina ("Dime Chinita," "Como Bailan Cha-cha-chá los Mexicanos"), Richard Egűes ("El Bodeguero" and "La Cantina") and Rafael Lay ("Cero Codazos, Cero Cabezazos").

The Chachachá was first presented to the public through the instrumental medium of the ''Charanga (Cuba), charanga,'' a typical Cuban dance band format made up of a flute, strings, piano, bass and percussion. The popularity of the Chachachá also revived the popularity of this kind of orchestra.

Chachachá is a genre of Cuban music. It has been a popular dance music which developed from the Danzón-mambo in the early 1950s, and became widely popular throughout the entire world.

Chachachávis a Cuban music genre whose creation has been traditionally attributed to Cuban composer and violinist Enrique Jorrín, which began his career playing for the Charanga (Cuba), charanga band Orquesta América.

According to the testimony of Enrique Jorrín, he composed some "Danzones" in which the musician of the orchestra had to sing short refrains, and this style was very successful. In the Danzón "Constancia" he introduced some montunos and the audience was motivated to join in singing the refrains. Jorrín also asked the members of the orchestra to sing in unison so the lyrics may be heard more clearly and achieve a greater impact in the audience. That way of singing also helped to mask the poor singing skills of the orchestra members.

Since its inception, Chachachá music had a close relationship with the dancer's steps. The well-known name Chachachá came into being with the help of the dancers at the Silver Star Club in Havana. When the dance was coupled to the rhythm of the music, it became evident that the dancer's feet were making a peculiar sound as they grazed the floor on three successive beats. It was like an onomatopoeia that sounded as: Chachachá. From this peculiar sound, a music genre was born which motivated people from around the world to dance at its catchy rhythm.

According to Olavo ALén: "During the 1950s, Chachachá maintained its popularity thanks to the efforts of many Cuban composers who were familiar with the technique of composing ''Danzón, danzones'' and who unleashed their creativity on the Chachachá", such as Rosendo Ruiz, Jr. ("Los Marcianos" and "Rico Vacilón"), Félix Reina ("Dime Chinita," "Como Bailan Cha-cha-chá los Mexicanos"), Richard Egűes ("El Bodeguero" and "La Cantina") and Rafael Lay ("Cero Codazos, Cero Cabezazos").

The Chachachá was first presented to the public through the instrumental medium of the ''Charanga (Cuba), charanga,'' a typical Cuban dance band format made up of a flute, strings, piano, bass and percussion. The popularity of the Chachachá also revived the popularity of this kind of orchestra.

Filin

Filin was a Cuban fashion of the 1940s and 1950s, influenced by popular music in the US. The word is derived from ''feeling''. It describes a style of post-microphone jazz-influenced romantic song (crooning). Its Cuban roots were in the bolero and the canción. Some Cuban quartets, such as Cuarteto d'Aida and Los Zafiros, modelled themselves on U.S. close-harmony groups. Others were singers who had heard Ella Fitzgerald, Sarah Vaughan and Nat King Cole. A house in Havana, where the trovador Tirso Díaz lived, became a meeting-place for singers and musicians interested in filin such as: Luis Yañez, César Portillo de la Luz, José Antonio Méndez, Niño Rivera, José Antonio Ñico Rojas, Elena Burke, Froilán, Aida Diestro and Frank Emilio Flynn. Here lyricists and singers could meet arrangers, such as Bebo Valdés, El Niño Rivera (Andrés Hechavarria), Peruchín (Pedro Justiz), and get help to develop their work. Filin singers included César Portillo de la Luz, José Antonio Méndez, who spent a decade in Mexico from 1949 to 1959, Frank Domínguez, the blind pianist Frank Emilio Flynn, and the great singers of boleros Elena Burke and the still-performing Omara Portuondo, who both came from the Cuarteto d'Aida. The filin movement originally had a place every afternoon on ''Radio Mil Diez''. Some of its most prominent singers, such as Pablo Milanés, took up the banner of the Nueva Trova at a later time.1960s and 70s

Modern Cuban music is known for its relentless mixing of musical genres, genres. For example, the 1970s saw Los Irakere use batá in a big band setting; this became known as son-batá or batá-rock. Later artists created the mozambique (music), mozambique, which mixed conga and Mambo (music), mambo, and batá-rumba, which mixed rumba and batá drum music. Mixtures including elements of hip hop music, hip hop,Revolutionary Cuba and Cuban exiles