Prion De Salvin MHNT on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

A prion () is a misfolded protein that induces misfolding in normal variants of the same protein, leading to

Lay summary: in reference to its ability to self-propagate and transmit its conformation to other proteins. Its main pronunciation is , although , as the

The infectious

The infectious

The first hypothesis that tried to explain how prions replicate in a protein-only manner was the

The first hypothesis that tried to explain how prions replicate in a protein-only manner was the

Lay summary: this report was retracted in 2024. Preliminary evidence supporting the notion that prions can be transmitted through use of urine-derived human menopausal gonadotropin, administered for the treatment of

World Health Organisation

– WHO information on prion diseases

The UK BSE Inquiry

nbsp;– Report of the UK public inquiry into BSE and variant CJD

UK Spongiform Encephalopathy Advisory Committee (SEAC)

* * {{Authority control Infectious diseases Amyloidosis

cellular death

Cell death is the event of a biological cell ceasing to carry out its functions. This may be the result of the natural process of old cells dying and being replaced by new ones, as in programmed cell death, or may result from factors such as di ...

. Prions are responsible for prion diseases, known as transmissible spongiform encephalopathy

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), also known as prion diseases, are a group of progressive, incurable, and fatal conditions that are associated with the prion hypothesis and affect the brain and nervous system of many animals, in ...

(TSEs), which are fatal and transmissible neurodegenerative disease

A neurodegenerative disease is caused by the progressive loss of neurons, in the process known as neurodegeneration. Neuronal damage may also ultimately result in their death. Neurodegenerative diseases include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, mul ...

s affecting both humans and animals. These proteins can misfold sporadically, due to genetic mutations, or by exposure to an already misfolded protein, leading to an abnormal three-dimensional structure that can propagate misfolding in other proteins.

The term ''prion'' comes from "proteinaceous infectious particle". Unlike other infectious agents such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi, prions do not contain nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

s (DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

or RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

). Prions are mainly twisted isoforms

A protein isoform, or "protein variant", is a member of a set of highly similar proteins that originate from a single gene and are the result of genetic differences. While many perform the same or similar biological roles, some isoforms have uniqu ...

of the major prion protein

The major prion protein (PrP) is encoded in the human body by the ''PRNP'' gene also known as CD230 (cluster of differentiation 230). Expression of the protein is most predominant in the nervous system but occurs in many other tissues throughou ...

(PrP), a naturally occurring protein with an uncertain function. They are the hypothesized cause of various TSEs

Tses () is a village in the ǁKaras Region of southern Namibia. It had 2,053 inhabitants in 2023.

Geography

Tses is situated one kilometre off the main B1 highway from Windhoek to Noordoewer, opposite the turning to Berseba and the Brukkaro ...

, including scrapie

Scrapie () is a fatal, degenerative disease affecting the nervous systems of sheep and goats. It is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), and as such it is thought to be caused by a prion. Scrapie has been known sin ...

in sheep, chronic wasting disease

Chronic wasting disease (CWD), sometimes called zombie deer disease, is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) affecting deer. TSEs are a family of diseases thought to be caused by misfolded proteins called prions and include simila ...

(CWD) in deer, bovine spongiform encephalopathy

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease, is an incurable and always fatal neurodegenerative disease of cattle. Symptoms include abnormal behavior, trouble walking, and weight loss. Later in the course of th ...

(BSE) in cattle (mad cow disease), and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is an incurable, always fatal neurodegenerative disease belonging to the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) group. Early symptoms include memory problems, behavioral changes, poor coordination, visu ...

(CJD) in humans.

All known prion diseases in mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s affect the structure of the brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

or other neural

In biology, the nervous system is the highly complex part of an animal that coordinates its actions and sensory information by transmitting signals to and from different parts of its body. The nervous system detects environmental changes t ...

tissues. These diseases are progressive, have no known effective treatment, and are invariably fatal. Most prion diseases were thought to be caused by PrP until 2015 when a prion form of alpha-synuclein

Alpha-synuclein (aSyn) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''SNCA'' gene. It is a neuronal protein involved in the regulation of synaptic vesicle trafficking and the release of neurotransmitters.

Alpha-synuclein is abundant in the brai ...

was linked to multiple system atrophy

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by tremors, slow movement, muscle rigidity, postural instability (collectively known as parkinsonism), autonomic dysfunction and ataxia. This is caused by progr ...

(MSA). Misfolded proteins are also linked to other neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

, Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a neurodegenerative disease primarily of the central nervous system, affecting both motor system, motor and non-motor systems. Symptoms typically develop gradually and non-motor issues become ...

, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND) or—in the United States—Lou Gehrig's disease (LGD), is a rare, Terminal illness, terminal neurodegenerative disease, neurodegenerative disorder that results i ...

(ALS), which are sometimes referred to as ''prion-like diseases''.

Prions are a type of intrinsically disordered protein that continuously changes conformation unless bound to a specific partner, such as another protein. Once a prion binds to another in the same conformation, it stabilizes and can form a fibril

Fibrils () are structural biological materials found in nearly all living organisms. Not to be confused with fibers or protein filament, filaments, fibrils tend to have diameters ranging from 10 to 100 nanometers (whereas fibers are micro to ...

, leading to abnormal protein aggregates called amyloids

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a fibrillar morphology of typically 7–13 nm in diameter, a β-sheet secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be stained by particular dyes, such as Congo red. In the human b ...

. These amyloids accumulate in infected tissue, causing damage and cell death. The structural stability of prions makes them resistant to denaturation by chemical or physical agents, complicating disposal and containment, and raising concerns about iatrogenic spread through medical instruments.

Etymology and pronunciation

The word ''prion'', coined in 1982 by Stanley B. Prusiner, is derived from protein and infection, hence prion, and is short for "proteinaceous infectious particle",Lay summary: in reference to its ability to self-propagate and transmit its conformation to other proteins. Its main pronunciation is , although , as the

homograph

A homograph (from the , and , ) is a word that shares the same written form as another word but has a different meaning. However, some dictionaries insist that the words must also be pronounced differently, while the Oxford English Dictionar ...

ic name of the bird (prions or whalebirds) is pronounced, is also heard. In his 1982 paper introducing the term, Prusiner specified that it is "pronounced ''pree-on''".

Prion protein

Structure

Prions consist of a misfolded form ofmajor prion protein

The major prion protein (PrP) is encoded in the human body by the ''PRNP'' gene also known as CD230 (cluster of differentiation 230). Expression of the protein is most predominant in the nervous system but occurs in many other tissues throughou ...

(PrP), a protein that is a natural part of the bodies of humans and other animals. The PrP found in infectious prions has a different structure

A structure is an arrangement and organization of interrelated elements in a material object or system, or the object or system so organized. Material structures include man-made objects such as buildings and machines and natural objects such as ...

and is resistant to protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s, the enzymes in the body that can normally break down proteins. The normal form of the protein is called PrPC, while the infectious form is called PrPSc – the ''C'' refers to 'cellular' PrP, while the ''Sc'' refers to 'scrapie

Scrapie () is a fatal, degenerative disease affecting the nervous systems of sheep and goats. It is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), and as such it is thought to be caused by a prion. Scrapie has been known sin ...

', the prototypic prion disease, occurring in sheep. PrP can also be induced to fold into other more-or-less well-defined isoforms in vitro; although their relationships to the form(s) that are pathogenic in vivo is often unclear, high-resolution structural analyses have begun to reveal structural features that correlate with prion infectivity.

PrPC

PrPC is a normal protein found on themembranes

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

of cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

, "including several blood components of which platelets

Platelets or thrombocytes () are a part of blood whose function (along with the coagulation factors) is to react to bleeding from blood vessel injury by clumping to form a blood clot. Platelets have no cell nucleus; they are fragments of cyto ...

constitute the largest reservoir in humans." It has 209 amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

s (in humans), one disulfide bond

In chemistry, a disulfide (or disulphide in British English) is a compound containing a functional group or the anion. The linkage is also called an SS-bond or sometimes a disulfide bridge and usually derived from two thiol groups.

In inor ...

, a molecular mass of 35–36 kDa

The dalton or unified atomic mass unit (symbols: Da or u, respectively) is a unit of mass defined as of the mass of an unbound neutral atom of carbon-12 in its nuclear and electronic ground state and at rest. It is a non-SI unit accepted f ...

and a mainly alpha-helical

An alpha helix (or α-helix) is a sequence of amino acids in a protein that are twisted into a coil (a helix).

The alpha helix is the most common structural arrangement in the secondary structure of proteins. It is also the most extreme type of l ...

structure. Several topological

Topology (from the Greek words , and ) is the branch of mathematics concerned with the properties of a geometric object that are preserved under continuous deformations, such as stretching, twisting, crumpling, and bending; that is, wit ...

forms exist; one cell surface form anchored via glycolipid

Glycolipids () are lipids with a carbohydrate attached by a glycosidic (covalent) bond. Their role is to maintain the stability of the cell membrane and to facilitate cellular recognition, which is crucial to the immune response and in the c ...

and two transmembrane

A transmembrane protein is a type of integral membrane protein that spans the entirety of the cell membrane. Many transmembrane proteins function as gateways to permit the transport of specific substances across the membrane. They frequently u ...

forms. The normal protein is not sedimentable; meaning that it cannot be separated by centrifuging techniques. It has a complex function

Function or functionality may refer to:

Computing

* Function key, a type of key on computer keyboards

* Function model, a structured representation of processes in a system

* Function object or functor or functionoid, a concept of object-orie ...

, which continues to be investigated. PrPC binds copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

(II) ion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

s (those in a +2 oxidation state

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical Electrical charge, charge of an atom if all of its Chemical bond, bonds to other atoms are fully Ionic bond, ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons ...

) with high affinity

In biochemistry and pharmacology, a ligand is a substance that forms a complex with a biomolecule to serve a biological purpose. The etymology stems from Latin ''ligare'', which means 'to bind'. In protein-ligand binding, the ligand is usually a ...

. This property is supposed to play a role in PrPC’s anti-oxidative properties via reversible oxidation

Redox ( , , reduction–oxidation or oxidation–reduction) is a type of chemical reaction in which the oxidation states of the reactants change. Oxidation is the loss of electrons or an increase in the oxidation state, while reduction is ...

of the N-terminal’s methionine

Methionine (symbol Met or M) () is an essential amino acid in humans.

As the precursor of other non-essential amino acids such as cysteine and taurine, versatile compounds such as SAM-e, and the important antioxidant glutathione, methionine play ...

residues into sulfoxide

In organic chemistry, a sulfoxide, also called a sulphoxide, is an organosulfur compound containing a sulfinyl () functional group attached to two carbon atoms. It is a polar functional group. Sulfoxides are oxidized derivatives of sulfides. E ...

. Moreover, studies have suggested that, in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

, due to PrPC’s low selectivity

Selectivity may refer to:

Psychology and behaviour

* Choice, making a selection among options

* Discrimination, the ability to recognize differences

* Socioemotional selectivity theory, in social psychology

Engineering

* Selectivity (radio), a ...

to metallic substrates, the protein’s anti oxidative function is impaired when in contact with metals other than copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

. PrPC is readily digested

Digestion is the breakdown of large insoluble food compounds into small water-soluble components so that they can be absorbed into the blood plasma. In certain organisms, these smaller substances are absorbed through the small intestine into th ...

by proteinase K

In molecular biology, Proteinase K (, ''protease K'', ''endopeptidase K'', ''Tritirachium alkaline proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album serine proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album proteinase K'') is a broad-spectrum serine protease. The enzyme was ...

and can be liberated from the cell surface by the enzyme phosphoinositide phospholipase C

Phosphoinositide phospholipase C (PLC, EC 3.1.4.11, triphosphoinositide phosphodiesterase, phosphoinositidase C, 1-phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate phosphodiesterase, monophosphatidylinositol phosphodiesterase, phosphatidylinositol phospho ...

(PI-PLC), which cleaves the glycophosphatidylinositol

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol () or glycophosphatidylinositol (GPI) is a phosphoglyceride that can be attached to the C-terminus of a protein during posttranslational modification. The resulting GPI-anchored proteins play key roles in a wide vari ...

(GPI) glycolipid anchor. PrP plays an important role in cell-cell adhesion and intracellular signaling

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the Biological process, process by which a Cell (biology), cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all Cell (biol ...

''in vivo'', and may therefore be involved in cell-cell communication in the brain.

PrPSc

The infectious

The infectious isoform

A protein isoform, or "protein variant", is a member of a set of highly similar proteins that originate from a single gene and are the result of genetic differences. While many perform the same or similar biological roles, some isoforms have uniqu ...

of PrP, known as PrPSc, or simply the prion, is able to convert normal PrPC proteins into the infectious isoform by changing their conformation, or shape; this, in turn, alters the way the proteins interconnect

In telecommunications, interconnection is the physical linking of a carrier's network with equipment or facilities not belonging to that network. The term may refer to a connection between a carrier's facilities and the equipment belonging to its ...

. PrPSc always causes prion disease. PrPSc has a higher proportion of β-sheet

The beta sheet (β-sheet, also β-pleated sheet) is a common structural motif, motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone chain, backbon ...

structure in place of the normal α-helix

An alpha helix (or α-helix) is a sequence of amino acids in a protein that are twisted into a coil (a helix).

The alpha helix is the most common structural arrangement in the Protein secondary structure, secondary structure of proteins. It is al ...

structure. Several highly infectious, brain-derived PrPSc structures have been discovered by cryo-electron microscopy

Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) is a transmission electron microscopy technique applied to samples cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For biological specimens, the structure is preserved by embedding in an environment of vitreous ice. An ...

. Another brain-derived fibril

Fibrils () are structural biological materials found in nearly all living organisms. Not to be confused with fibers or protein filament, filaments, fibrils tend to have diameters ranging from 10 to 100 nanometers (whereas fibers are micro to ...

structure isolated from humans with Gerstmann-Straussler-Schienker syndrome has also been determined. All of the structures described in high resolution so far are amyloid

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a fibrillar morphology of typically 7–13 nm in diameter, a β-sheet secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be stained by particular dyes, such as Congo red. In the human ...

fibers in which individual PrP molecules are stacked via intermolecular beta sheets. However, 2-D crystalline arrays have also been reported at lower resolution in ''ex vivo'' preparations of prions. In the prion amyloids, the glycolipid

Glycolipids () are lipids with a carbohydrate attached by a glycosidic (covalent) bond. Their role is to maintain the stability of the cell membrane and to facilitate cellular recognition, which is crucial to the immune response and in the c ...

anchors and asparagine

Asparagine (symbol Asn or N) is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. It contains an α-amino group (which is in the protonated −NH form under biological conditions), an α-carboxylic acid group (which is in the depro ...

-linked glycans, when present, project outward from the lateral surfaces of the fiber cores. Often PrPSc is bound to cellular membranes, presumably via its array of glycolipid anchors, however, sometimes the fibers are dissociated from membranes and accumulate outside of cells in the form of plaques. The end of each fiber acts as a template onto which free protein molecules may attach, allowing the fiber to grow. This growth process requires complete refolding of PrPC. Different prion strains have distinct templates, or conformations, even when composed of PrP molecules of the same amino acid sequence

Protein primary structure is the linear sequence of amino acids in a peptide or protein. By convention, the primary structure of a protein is reported starting from the amino-terminal (N) end to the carboxyl-terminal (C) end. Protein biosynthe ...

, as occurs in a particular host genotype

The genotype of an organism is its complete set of genetic material. Genotype can also be used to refer to the alleles or variants an individual carries in a particular gene or genetic location. The number of alleles an individual can have in a ...

. Under most circumstances, only PrP molecules with an identical amino acid sequence to the infectious PrPSc are incorporated into the growing fiber. However, cross-species transmission

Cross-species transmission (CST), also called interspecies transmission, host jump, or spillover, is the transmission of an infectious pathogen, such as a virus, between hosts belonging to different species. Once introduced into an individual o ...

also happens rarely.

PrPres

Protease-resistant PrPSc-like protein (PrPres) is the name given to any isoform of PrPc which is structurally altered and converted into a misfoldedproteinase K

In molecular biology, Proteinase K (, ''protease K'', ''endopeptidase K'', ''Tritirachium alkaline proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album serine proteinase'', ''Tritirachium album proteinase K'') is a broad-spectrum serine protease. The enzyme was ...

-resistant form. To model conversion of PrPC to PrPSc ''in vitro'', Kocisko ''et al''. showed that PrPSc could cause PrPC to convert to PrPres under cell-free conditions and Soto ''et al''. demonstrated sustained amplification of PrPres and prion infectivity by a procedure involving cyclic amplification of protein misfolding. The term "PrPres" may refer either to protease-resistant forms of PrPSc, which is isolated from infectious tissue and associated with the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy agent, or to other protease-resistant forms of PrP that, for example, might be generated ''in vitro''. Accordingly, unlike PrPSc, PrPres may not necessarily be infectious.

Normal function of PrP

The physiological function of the prion protein remains poorly understood. While data from in vitro experiments suggest many dissimilar roles, studies on PrPknockout mice

A knockout mouse, or knock-out mouse, is a genetically modified mouse (''Mus musculus'') in which researchers have inactivated, or " knocked out", an existing gene by replacing it or disrupting it with an artificial piece of DNA. They are importan ...

have provided only limited information because these animals exhibit only minor abnormalities. In research done in mice, it was found that the cleavage of PrP in peripheral nerves causes the activation of myelin

Myelin Sheath ( ) is a lipid-rich material that in most vertebrates surrounds the axons of neurons to insulate them and increase the rate at which electrical impulses (called action potentials) pass along the axon. The myelinated axon can be lik ...

repair in Schwann cells

Schwann cells or neurolemmocytes (named after German physiologist Theodor Schwann) are the principal glia of the peripheral nervous system (PNS). Glial cells function to support neurons and in the PNS, also include Satellite glial cell, satellite ...

and that the lack of PrP proteins caused demyelination in those cells.

PrP and regulated cell death

MAVS, RIP1, and RIP3 are prion-like proteins found in other parts of the body. They also polymerise into filamentous amyloid fibers which initiate regulated cell death in the case of a viral infection to prevent the spread ofvirions

A virion (plural, ''viria'' or ''virions'') is an inert virus particle capable of invading a cell. Upon entering the cell, the virion disassembles and the genetic material from the virus takes control of the cell infrastructure, thus enabling th ...

to other, surrounding cells.

PrP and long-term memory

A review of evidence in 2005 suggested that PrP may have a normal function in the maintenance oflong-term memory

Long-term memory (LTM) is the stage of the Atkinson–Shiffrin memory model in which informative knowledge is held indefinitely. It is defined in contrast to sensory memory, the initial stage, and short-term or working memory, the second stage ...

. As well, a 2004 study found that mice lacking genes for normal cellular PrP protein show altered hippocampal

The hippocampus (: hippocampi; via Latin from Greek , 'seahorse'), also hippocampus proper, is a major component of the brain of humans and many other vertebrates. In the human brain the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus, and the subiculum ar ...

long-term potentiation

In neuroscience, long-term potentiation (LTP) is a persistent strengthening of synapses based on recent patterns of activity. These are patterns of synaptic activity that produce a long-lasting increase in signal transmission between two neuron ...

. A recent study that also suggests why this might be the case, found that neuronal protein CPEB

CPEB, or cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein, is a highly conserved RNA-binding protein that promotes the elongation of the polyadenine tail of messenger RNA. CPEB is present at postsynaptic sites and dendrites where it stimulat ...

has a similar genetic sequence to yeast prion proteins. The prion-like formation of CPEB is essential for maintaining long-term synaptic changes associated with long-term memory formation.

PrP and stem cell renewal

A 2006 article from the Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research indicates that PrP expression on stem cells is necessary for an organism's self-renewal ofbone marrow

Bone marrow is a semi-solid biological tissue, tissue found within the Spongy bone, spongy (also known as cancellous) portions of bones. In birds and mammals, bone marrow is the primary site of new blood cell production (or haematopoiesis). It i ...

. The study showed that all long-term hematopoietic stem cell

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) are the stem cells that give rise to other blood cells. This process is called haematopoiesis. In vertebrates, the first definitive HSCs arise from the ventral endothelial wall of the embryonic aorta within the ...

s express PrP on their cell membrane and that hematopoietic tissues with PrP-null stem cells exhibit increased sensitivity to cell depletion.

PrP and innate immunity

There is some evidence that PrP may play a role ininnate immunity

The innate immune system or nonspecific immune system is one of the two main immunity strategies in vertebrates (the other being the adaptive immune system). The innate immune system is an alternate defense strategy and is the dominant immune s ...

, as the expression of PRNP

The major prion protein (PrP) is encoded in the human body by the ''PRNP'' gene also known as CD230 (cluster of differentiation 230). Expression of the protein is most predominant in the nervous system but occurs in many other tissues throughou ...

, the PrP gene, is upregulated in many viral infections and PrP has antiviral properties against many viruses, including HIV

The human immunodeficiency viruses (HIV) are two species of '' Lentivirus'' (a subgroup of retrovirus) that infect humans. Over time, they cause acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), a condition in which progressive failure of the im ...

.

Replication

The first hypothesis that tried to explain how prions replicate in a protein-only manner was the

The first hypothesis that tried to explain how prions replicate in a protein-only manner was the heterodimer

In biochemistry, a protein dimer is a macromolecular complex or multimer formed by two protein monomers, or single proteins, which are usually non-covalently bound. Many macromolecules, such as proteins or nucleic acids, form dimers. The word ...

model. This model assumed that a single PrPSc molecule binds to a single PrPC molecule and catalyzes

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

its conversion into PrPSc. The two PrPSc molecules then come apart and can go on to convert more PrPC. However, a model of prion replication must explain both how prions propagate, and why their spontaneous appearance is so rare. Manfred Eigen

Manfred Eigen (; 9 May 1927 – 6 February 2019) was a German biophysical chemist who won the 1967 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for work on measuring fast chemical reactions.

Eigen's research helped solve major problems in physical chemistry and ...

showed that the heterodimer model requires PrPSc to be an extraordinarily effective catalyst, increasing the rate of the conversion reaction by a factor of around 1015. This problem does not arise if PrPSc exists only in aggregated forms such as amyloid

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a fibrillar morphology of typically 7–13 nm in diameter, a β-sheet secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be stained by particular dyes, such as Congo red. In the human ...

, where cooperativity

Cooperativity is a phenomenon displayed by systems involving identical or near-identical elements, which act dependently of each other, relative to a hypothetical standard non-interacting system in which the individual elements are acting indepen ...

may act as a barrier to spontaneous conversion. What is more, despite considerable effort, infectious monomeric PrPSc has never been isolated.

An alternative model assumes that PrPSc exists only as fibril

Fibrils () are structural biological materials found in nearly all living organisms. Not to be confused with fibers or protein filament, filaments, fibrils tend to have diameters ranging from 10 to 100 nanometers (whereas fibers are micro to ...

s, and that fibril ends bind PrPC and convert it into PrPSc. If this were all, then the quantity of prions would increase linearly, forming ever longer fibrils. But exponential growth

Exponential growth occurs when a quantity grows as an exponential function of time. The quantity grows at a rate directly proportional to its present size. For example, when it is 3 times as big as it is now, it will be growing 3 times as fast ...

of both PrPSc and the quantity of infectious particles is observed during prion disease. This can be explained by taking into account fibril breakage. A mathematical solution for the exponential growth rate resulting from the combination of fibril growth and fibril breakage has been found. The exponential growth rate depends largely on the square root

In mathematics, a square root of a number is a number such that y^2 = x; in other words, a number whose ''square'' (the result of multiplying the number by itself, or y \cdot y) is . For example, 4 and −4 are square roots of 16 because 4 ...

of the PrPC concentration. The incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

is determined by the exponential growth rate, and in vivo

Studies that are ''in vivo'' (Latin for "within the living"; often not italicized in English) are those in which the effects of various biological entities are tested on whole, living organisms or cells, usually animals, including humans, an ...

data on prion diseases in transgenic mice

A genetically modified mouse, genetically engineered mouse model (GEMM) or transgenic mouse is a mouse (''Mus musculus'') that has had its genome altered through the use of genetic engineering techniques. Genetically modified mice are commonly use ...

match this prediction. The same square root dependence is also seen in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

in experiments with a variety of different amyloid proteins.

The mechanism of prion replication has implications for designing drugs. Since the incubation period of prion diseases is so long, an effective drug does not need to eliminate all prions, but simply needs to slow down the rate of exponential growth. Models predict that the most effective way to achieve this, using a drug with the lowest possible dose, is to find a drug that binds to fibril ends and blocks them from growing any further.

Researchers at Dartmouth College discovered that endogenous host cofactor molecules such as the phospholipid molecule (e.g. phosphatidylethanolamine) and polyanions

Polyelectrolytes are polymers whose repeating units bear an electrolyte group. Polycations and polyanions are polyelectrolytes. These groups dissociate in aqueous solutions (water), making the polymers charged. Polyelectrolyte properties are th ...

(e.g. single stranded RNA molecules) are necessary to form PrPSc molecules with high levels of specific infectivity ''in vitro'', whereas protein-only PrPSc molecules appear to lack significant levels of biological infectivity.

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

Prions cause neurodegenerative disease by aggregating extracellularly within thecentral nervous system

The central nervous system (CNS) is the part of the nervous system consisting primarily of the brain, spinal cord and retina. The CNS is so named because the brain integrates the received information and coordinates and influences the activity o ...

to form plaques known as amyloids

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a fibrillar morphology of typically 7–13 nm in diameter, a β-sheet secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be stained by particular dyes, such as Congo red. In the human b ...

, which disrupt the normal tissue structure. This disruption is characterized by "holes" in the tissue with resultant spongy architecture due to the vacuole

A vacuole () is a membrane-bound organelle which is present in Plant cell, plant and Fungus, fungal Cell (biology), cells and some protist, animal, and bacterial cells. Vacuoles are essentially enclosed compartments which are filled with water ...

formation in the neurons. Other histological changes include astrogliosis

Astrogliosis (also known as astrocytosis or referred to as reactive astrogliosis) is an abnormal increase in the number of astrocytes due to the destruction of nearby neurons from central nervous system (CNS) trauma (medicine), trauma, infection, ...

and the absence of an inflammatory reaction. While the incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

for prion diseases is relatively long (5 to 20 years), once symptoms appear the disease progresses rapidly, leading to brain damage and death. Neurodegenerative symptoms can include convulsion

A convulsion is a medical condition where the body muscles contract and relax rapidly and repeatedly, resulting in uncontrolled shaking. Because epileptic seizures typically include convulsions, the term ''convulsion'' is often used as a synony ...

s, dementia

Dementia is a syndrome associated with many neurodegenerative diseases, characterized by a general decline in cognitive abilities that affects a person's ability to perform activities of daily living, everyday activities. This typically invo ...

, ataxia

Ataxia (from Greek α- negative prefix+ -τάξις rder= "lack of order") is a neurological sign consisting of lack of voluntary coordination of muscle movements that can include gait abnormality, speech changes, and abnormalities in e ...

(balance and coordination dysfunction), and behavioural or personality changes.

Many different mammalian species can be affected by prion diseases, as the prion protein (PrP) is very similar in all mammals. Due to small differences in PrP between different species it is unusual for a prion disease to transmit from one species to another. The human prion disease variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease, however, is thought to be caused by a prion that typically infects cattle, causing bovine spongiform encephalopathy

Bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE), commonly known as mad cow disease, is an incurable and always fatal neurodegenerative disease of cattle. Symptoms include abnormal behavior, trouble walking, and weight loss. Later in the course of th ...

and is transmitted through infected meat.

All known prion diseases are untreatable and fatal.

Until 2015 all known mammalian prion diseases were considered to be caused by the prion protein, PrP. After 2015 this remains true for diseases in the category of "transmissible spongiform encephalopathy" (TSE), which is transmissible and causes a specific sponge-like appearance of infected brain tissue. The endogenous, properly folded form of the prion protein is denoted PrPC (for ''Common'' or ''Cellular''), whereas the disease-linked, misfolded form is denoted PrPSc (for ''Scrapie''), after one of the diseases first linked to prions and neurodegeneration. The precise structure of the prion is not known, though they can be formed spontaneously by combining PrPC, homopolymeric polyadenylic acid, and lipids in a protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA) reaction even in the absence of pre-existing infectious prions. This result is further evidence that prion replication does not require genetic information.

Transmission

It has been recognized that prion diseases can arise in three different ways: acquired, familial, or sporadic. It is often assumed that the diseased form directly interacts with the normal form to make it rearrange its structure. One idea, the "Protein X" hypothesis, is that an as-yet unidentified cellular protein (Protein X) enables the conversion of PrPC to PrPSc by bringing a molecule of each of the two together into a complex. The primary method of infection in animals is through ingestion. It is thought that prions may be deposited in the environment through the remains of dead animals and via urine, saliva, and other body fluids. They may then linger in the soil by binding to clay and other minerals. AUniversity of California

The University of California (UC) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university, research university system in the U.S. state of California. Headquartered in Oakland, California, Oakland, the system is co ...

research team has provided evidence for the theory that infection can occur from prions in manure. And, since manure is present in many areas surrounding water reservoirs, as well as used on many crop fields, it raises the possibility of widespread transmission. Although it was initially reported in January 2011 that researchers had discovered prions spreading through airborne transmission on aerosol

An aerosol is a suspension (chemistry), suspension of fine solid particles or liquid Drop (liquid), droplets in air or another gas. Aerosols can be generated from natural or Human impact on the environment, human causes. The term ''aerosol'' co ...

particles in an animal testing

Animal testing, also known as animal experimentation, animal research, and ''in vivo'' testing, is the use of animals, as model organisms, in experiments that seek answers to scientific and medical questions. This approach can be contrasted ...

experiment focusing on scrapie

Scrapie () is a fatal, degenerative disease affecting the nervous systems of sheep and goats. It is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), and as such it is thought to be caused by a prion. Scrapie has been known sin ...

infection in laboratory mice

The laboratory mouse or lab mouse is a small mammal of the order Rodentia which is bred and used for scientific research or feeders for certain pets. Laboratory animal sources for these mice are usually of the species ''Mus musculus''. They a ...

,Lay summary: this report was retracted in 2024. Preliminary evidence supporting the notion that prions can be transmitted through use of urine-derived human menopausal gonadotropin, administered for the treatment of

infertility

In biology, infertility is the inability of a male and female organism to Sexual reproduction, reproduce. It is usually not the natural state of a healthy organism that has reached sexual maturity, so children who have not undergone puberty, whi ...

, was published in 2011.

Genetic susceptibility

The majority of human prion diseases are classified as sporadic Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (sCJD). Genetic research has identified an association between susceptibility to sCJD and a polymorphism at codon 129 in the PRNP gene, which encodes the prion protein (PrP). A homozygous methionine/methionine (MM) genotype at this position has been shown to significantly increase the risk of developing sCJD when compared to a heterozygous methionine/valine (MV) genotype. Analysis of multiple studies has shown that individuals with the MM genotype are approximately five times more likely to develop sCJD than those with the MV genotype.Prions in plants

In 2015, researchers atThe University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston

The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (UTHealth Houston) is a public academic health science center in Houston, Texas, United States. It was created in 1972 by The University of Texas System Board of Regents. It is located ...

found that plants can be a vector for prions. When researchers fed hamsters grass that grew on ground where a deer that died with chronic wasting disease

Chronic wasting disease (CWD), sometimes called zombie deer disease, is a transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) affecting deer. TSEs are a family of diseases thought to be caused by misfolded proteins called prions and include simila ...

(CWD) was buried, the hamsters became ill with CWD, suggesting that prions can bind to plants, which then take them up into the leaf and stem structure, where they can be eaten by herbivores, thus completing the cycle. It is thus possible that there is a progressively accumulating number of prions in the environment.

Sterilization

Infectious particles possessingnucleic acid

Nucleic acids are large biomolecules that are crucial in all cells and viruses. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomer components: a pentose, 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main classes of nuclei ...

are dependent upon it to direct their continued replication. Prions, however, are infectious by their effect on normal versions of the protein. Sterilizing prions, therefore, requires the denaturation of the protein to a state in which the molecule is no longer able to induce the abnormal folding of normal proteins. In general, prions are quite resistant to protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s, heat, ionizing radiation

Ionizing (ionising) radiation, including Radioactive decay, nuclear radiation, consists of subatomic particles or electromagnetic waves that have enough energy per individual photon or particle to ionization, ionize atoms or molecules by detaching ...

, and formaldehyde

Formaldehyde ( , ) (systematic name methanal) is an organic compound with the chemical formula and structure , more precisely . The compound is a pungent, colourless gas that polymerises spontaneously into paraformaldehyde. It is stored as ...

treatments, although their infectivity can be reduced by such treatments. Effective prion decontamination relies upon protein hydrolysis

Hydrolysis (; ) is any chemical reaction in which a molecule of water breaks one or more chemical bonds. The term is used broadly for substitution reaction, substitution, elimination reaction, elimination, and solvation reactions in which water ...

or reduction or destruction of protein tertiary structure

Protein tertiary structure is the three-dimensional shape of a protein. The tertiary structure will have a single polypeptide chain "backbone" with one or more protein secondary structures, the protein domains. Amino acid side chains and the b ...

. Examples include sodium hypochlorite

Sodium hypochlorite is an alkaline inorganic chemical compound with the formula (also written as NaClO). It is commonly known in a dilute aqueous solution as bleach or chlorine bleach. It is the sodium salt of hypochlorous acid, consisting of ...

, sodium hydroxide

Sodium hydroxide, also known as lye and caustic soda, is an inorganic compound with the formula . It is a white solid ionic compound consisting of sodium cations and hydroxide anions .

Sodium hydroxide is a highly corrosive base (chemistry), ...

, and strongly acidic detergent

A detergent is a surfactant or a mixture of surfactants with Cleanliness, cleansing properties when in Concentration, dilute Solution (chemistry), solutions. There are a large variety of detergents. A common family is the alkylbenzene sulfonate ...

s such as LpH.

The World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

recommends any of the following three procedures for the sterilization of all heat-resistant surgical instruments to ensure that they are not contaminated with prions:

# Immerse in 1N sodium hydroxide and place in a gravity-displacement autoclave at 121 °C for 30 minutes; clean; rinse in water; and then perform routine sterilization processes.

# Immerse in 1N sodium hypochlorite (20,000 parts per million available chlorine) for 1 hour; transfer instruments to water; heat in a gravity-displacement autoclave at 121 °C for 1 hour; clean; and then perform routine sterilization processes.

# Immerse in 1N sodium hydroxide or sodium hypochlorite (20,000 parts per million available chlorine) for 1 hour; remove and rinse in water, then transfer to an open pan and heat in a gravity-displacement (121 °C) or in a porous-load (134 °C) autoclave for 1 hour; clean; and then perform routine sterilization processes.

for 18 minutes in a pressurized steam autoclave

An autoclave is a machine used to carry out industrial and scientific processes requiring elevated temperature and pressure in relation to ambient pressure and/or temperature. Autoclaves are used before surgical procedures to perform steriliza ...

has been found to be somewhat effective in deactivating the agent of disease. Ozone

Ozone () (or trioxygen) is an Inorganic compound, inorganic molecule with the chemical formula . It is a pale blue gas with a distinctively pungent smell. It is an allotrope of oxygen that is much less stable than the diatomic allotrope , break ...

sterilization has been studied as a potential method for prion denaturation and deactivation. Other approaches being developed include thiourea

Thiourea () is an organosulfur compound with the formula and the structure . It is structurally similar to urea (), with the oxygen atom replaced by sulfur atom (as implied by the '' thio-'' prefix). The properties of urea and thiourea differ s ...

-urea

Urea, also called carbamide (because it is a diamide of carbonic acid), is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two Amine, amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest am ...

treatment, guanidinium chloride

Guanidinium chloride or guanidine hydrochloride, usually abbreviated GdmCl and sometimes GdnHCl or GuHCl, is the hydrochloride salt of guanidine.

Structure

Guanidinium chloride on a weighing boat

Guanidinium chloride crystallizes in orthorho ...

treatment, and special heat-resistant subtilisin

Subtilisin is a protease (a protein-digesting enzyme) initially obtained from ''Bacillus subtilis''.

Subtilisins belong to subtilases, a group of serine proteases that – like all serine proteases – initiate the nucleophilic attack on the ...

combined with heat and detergent. A number of decontamination reagents have been commercially manufactured with significant differences in efficacy among methods. A method sufficient for sterilizing prions on one material may fail on another.

Renaturation of a completely denatured prion to infectious status has not yet been achieved; however, partially denatured prions can be renatured to an infective status under certain artificial conditions.

Degradation resistance in nature

Overwhelming evidence shows that prions resist degradation and persist in the environment for years, andprotease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

s do not degrade them. Experimental evidence shows that ''unbound'' prions degrade over time, while soil-bound prions remain at stable or increasing levels, suggesting that prions likely accumulate in the environment. One 2015 study by US scientists found that repeated drying and wetting may render soil bound prions less infectious, although this was dependent on the soil type they were bound to.

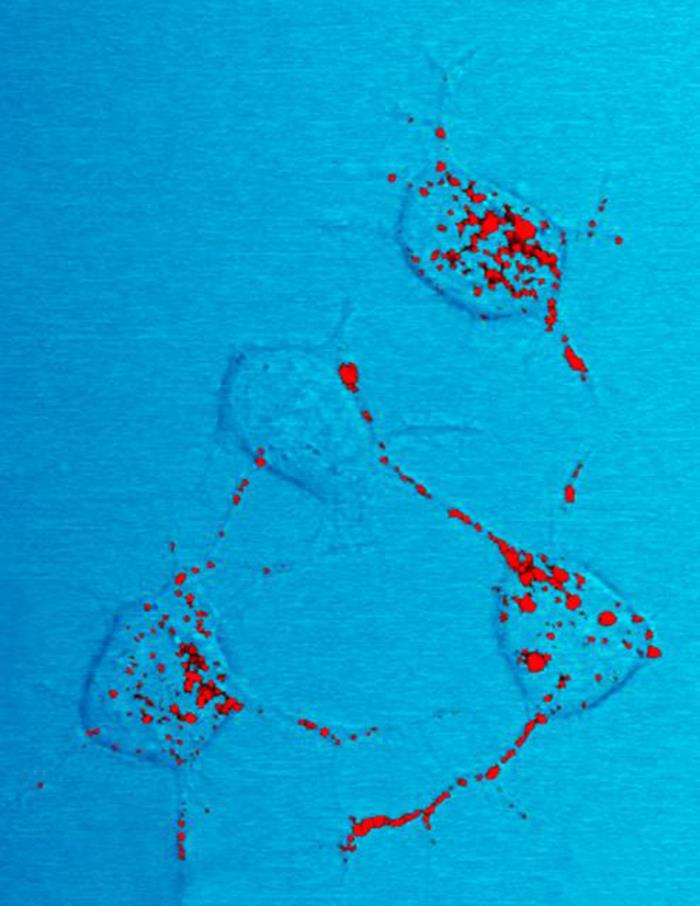

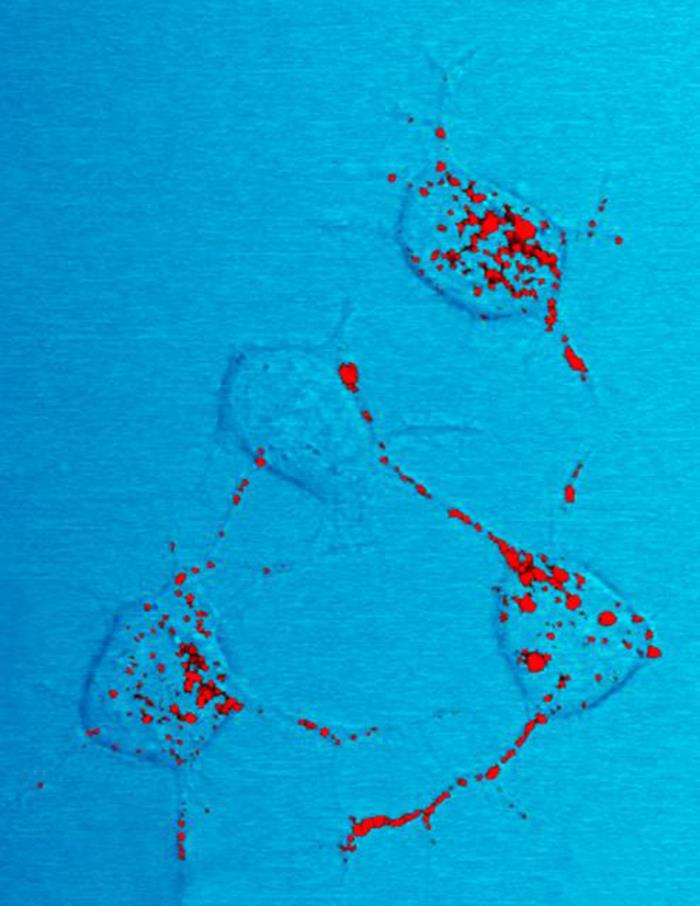

Degradation by living beings

More recent studies suggest scrapie prions can be degraded by diverse cellular machinery of the affected animal cell. In an infected cell, extracellular lysosomal PrPSc does not tend to accumulate and is rapidly cleared by thelysosome

A lysosome () is a membrane-bound organelle that is found in all mammalian cells, with the exception of red blood cells (erythrocytes). There are normally hundreds of lysosomes in the cytosol, where they function as the cell’s degradation cent ...

via the endosome

Endosomes are a collection of intracellular sorting organelles in eukaryotic cells. They are parts of the endocytic membrane transport pathway originating from the trans Golgi network. Molecules or ligands internalized from the plasma membra ...

. The intracellular portion is harder to clear and tends to build up. The ubiquitin proteasome system appears to be able to degrade small enough aggregates. Autophagy

Autophagy (or autophagocytosis; from the Greek language, Greek , , meaning "self-devouring" and , , meaning "hollow") is the natural, conserved degradation of the cell that removes unnecessary or dysfunctional components through a lysosome-depe ...

plays a bigger role by accepting PrPSc from the ER lumen and degrading it. Altogether these mechanisms allow the cell to delay its death from being overwhelmed by misfolded proteins. Inhibition of autophagy accelerates prion accumulation whereas encouragement of autophagy promotes prion clearance. Some autophagy-promoting compounds have shown promise in animal models by delaying disease onset and death.

In addition, keratinase

Keratinases are proteolytic enzymes that digest keratin. They hold industrial promise, as they can turn keratin-rich farm waste such as feather meal into more digestible fragments.

History

They were initially classified as 'proteinases of unk ...

from ''B. licheniformis'', alkaline serine protease

Serine proteases (or serine endopeptidases) are enzymes that cleave peptide bonds in proteins. Serine serves as the nucleophilic amino acid at the (enzyme's) active site.

They are found ubiquitously in both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Serin ...

from ''Streptomyces sp'', subtilisin

Subtilisin is a protease (a protein-digesting enzyme) initially obtained from ''Bacillus subtilis''.

Subtilisins belong to subtilases, a group of serine proteases that – like all serine proteases – initiate the nucleophilic attack on the ...

-like pernisine from '' Aeropyrum pernix'', alkaline protease from ''Nocardiopsis

''Nocardiopsis'' is a bacterial genus from the family Nocardiopsaceae which can produces some antimicrobial compounds, including thiopeptides. ''Nocardiopsis'' occur mostly in saline and alkaline soils.

Phylogeny

The currently accepted taxonomy ...

sp'', nattokinase

Nattokinase (pronounced ) is an enzyme extracted and purified from a Japanese food called nattō. Nattō is produced by fermentation (biochemistry), fermentation by adding the bacterium ''Bacillus subtilis#Uses, Bacillus subtilis'' Bacillus subtil ...

from '' B. subtilis'', engineered subtilisins from ''B. lentus'' and serine protease from three lichen species have been found to degrade PrPSc.

Fungi

Proteins showing prion-type behavior are also found in somefungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, which has been useful in helping to understand mammalian prions. Fungal prion

A fungal prion is a prion that infects hosts which are fungi. Fungal prions are naturally occurring proteins that can switch between multiple, structurally distinct conformations, at least one of which is self-propagating and transmissible to oth ...

s do not always cause disease in their hosts. In yeast, protein refolding to the prion configuration is assisted by chaperone proteins such as Hsp104

Hsp104 is a heat-shock protein. It is known to reverse toxicity of mutant α-synuclein, TDP-43, FUS (gene), FUS, and TAF15 in yeast cells. Conserved in prokaryotes (ClpB), fungi, plants and as well as animal mitochondria, there is yet to see hsp10 ...

. All known prions induce the formation of an amyloid

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a fibrillar morphology of typically 7–13 nm in diameter, a β-sheet secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be stained by particular dyes, such as Congo red. In the human ...

fold, in which the protein polymerises into an aggregate consisting of tightly packed beta sheet

The beta sheet (β-sheet, also β-pleated sheet) is a common motif of the regular protein secondary structure. Beta sheets consist of beta strands (β-strands) connected laterally by at least two or three backbone hydrogen bonds, forming a gene ...

s. Amyloid aggregates are fibrils, growing at their ends, and replicate when breakage causes two growing ends to become four growing ends. The incubation period

Incubation period (also known as the latent period or latency period) is the time elapsed between exposure to a pathogenic organism, a chemical, or ionizing radiation, radiation, and when symptoms and signs are first apparent. In a typical infect ...

of prion diseases is determined by the exponential growth

Exponential growth occurs when a quantity grows as an exponential function of time. The quantity grows at a rate directly proportional to its present size. For example, when it is 3 times as big as it is now, it will be growing 3 times as fast ...

rate associated with prion replication, which is a balance between the linear growth and the breakage of aggregates.

Fungal proteins that exhibit templated structural change were discovered in the yeast ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungal microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have be ...

'' by Reed Wickner in the early 1990s. For their mechanistic similarity to mammalian prions, they were termed yeast prions. Subsequent to this, a prion has also been found in the fungus ''Podospora anserina

''Podospora anserina'' is a filamentous ascomycete fungus from the order Sordariales. It is considered a model organism for the study of molecular biology of senescence (aging), prions, sexual reproduction, and meiotic drive. It has an obligate ...

''. These prions behave similarly to PrP, but, in general, are nontoxic to their hosts. Susan Lindquist's group at the Whitehead Institute

Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research is a non-profit research institute located in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States that is dedicated to improving human health through basic biomedical research. It was founded as a fiscally indep ...

has argued some of the fungal prions are not associated with any disease state, but may have a useful role; however, researchers at the NIH have also provided arguments suggesting that fungal prions could be considered a diseased state. There is evidence that fungal proteins have evolved specific functions that are beneficial to the microorganism that enhance their ability to adapt to their diverse environments. Further, within yeasts, prions can act as vectors of epigenetic

In biology, epigenetics is the study of changes in gene expression that happen without changes to the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix ''epi-'' (ἐπι- "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "on top of" or "in ...

inheritance, transferring traits to offspring without any genomic

Genomics is an interdisciplinary field of molecular biology focusing on the structure, function, evolution, mapping, and editing of genomes. A genome is an organism's complete set of DNA, including all of its genes as well as its hierarchical, ...

change.

Research into fungal prion

A fungal prion is a prion that infects hosts which are fungi. Fungal prions are naturally occurring proteins that can switch between multiple, structurally distinct conformations, at least one of which is self-propagating and transmissible to oth ...

s has given strong support to the protein-only concept, since purified protein extracted from cells with a prion state has been demonstrated to convert the normal form of the protein into a misfolded form ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

'', and in the process, preserve the information corresponding to different strains of the prion state. It has also shed some light on prion domains, which are regions in a protein that promote the conversion into a prion. Fungal prions have helped to suggest mechanisms of conversion that may apply to all prions, though fungal prions appear distinct from infectious mammalian prions in the lack of cofactor required for propagation. The characteristic prion domains may vary between species – e.g., characteristic fungal prion domains are not found in mammalian prions.

Treatments

There are no effective treatments for prion diseases as of 2018. Clinical trials in humans have not met with success and have been hampered by the rarity of prion diseases. Many possible treatments work in the test-tube but not in lab animals. One treatment that prolongs the incubation period in lab mice has failed in human patients diagnosed with definite or probable vCJD. Another treatment that works in mice was only tried in 6 human patients before it went out of stock, all of which died. There was no significant increase in lifespan, but autopsy suggests that the drug has partially worked. While there is no known way to extend the life of a prion disease patient, some drugs can be prescribed to control specific symptoms of the disease and accommodations can be given to improve quality of life.In other diseases

Prion-like domains have been found in a variety of other mammalian proteins. Some of these proteins have been implicated in the ontogeny of age-related neurodegenerative disorders such asamyotrophic lateral sclerosis

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND) or—in the United States—Lou Gehrig's disease (LGD), is a rare, Terminal illness, terminal neurodegenerative disease, neurodegenerative disorder that results i ...

(ALS), frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions (FTLD-U), Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

, Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a neurodegenerative disease primarily of the central nervous system, affecting both motor system, motor and non-motor systems. Symptoms typically develop gradually and non-motor issues become ...

, and Huntington's disease

Huntington's disease (HD), also known as Huntington's chorea, is an incurable neurodegenerative disease that is mostly Genetic disorder#Autosomal dominant, inherited. It typically presents as a triad of progressive psychiatric, cognitive, and ...

. They are also implicated in some forms of systemic amyloidosis

Amyloidosis is a group of diseases in which abnormal proteins, known as amyloid fibrils, build up in tissue. There are several non-specific and vague signs and symptoms associated with amyloidosis. These include fatigue, peripheral edema, weigh ...

including AA amyloidosis

AA amyloidosis is a form of amyloidosis, a disease characterized by the abnormal deposition of fibers of insoluble protein in the extracellular space of various tissues and organs. In AA amyloidosis, the deposited protein is serum amyloid A prote ...

that develops in humans and animals with inflammatory and infectious diseases such as tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB), also known colloquially as the "white death", or historically as consumption, is a contagious disease usually caused by ''Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can al ...

, Crohn's disease

Crohn's disease is a type of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that may affect any segment of the gastrointestinal tract. Symptoms often include abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, abdominal distension, and weight loss. Complications outside of the ...

, rheumatoid arthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a long-term autoimmune disorder that primarily affects synovial joint, joints. It typically results in warm, swollen, and painful joints. Pain and stiffness often worsen following rest. Most commonly, the wrist and h ...

, and HIV/AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

. AA amyloidosis, like prion disease, may be transmissible. This has given rise to the 'prion paradigm', where otherwise harmless proteins can be converted to a pathogenic form by a small number of misfolded, nucleating proteins.

The definition of a prion-like domain arises from the study of fungal prions. In yeast, prionogenic proteins have a portable prion domain that is both necessary and sufficient for self-templating and protein aggregation. This has been shown by attaching the prion domain to a reporter protein, which then aggregates like a known prion. Similarly, removing the prion domain from a fungal prion protein inhibits prionogenesis. This modular view of prion behaviour has led to the hypothesis that similar prion domains are present in animal proteins, in addition to PrP. These fungal prion domains have several characteristic sequence features. They are typically enriched in asparagine, glutamine, tyrosine and glycine residues, with an asparagine bias being particularly conducive to the aggregative property of prions. Historically, prionogenesis has been seen as independent of sequence and only dependent on relative residue content. However, this has been shown to be false, with the spacing of prolines and charged residues having been shown to be critical in amyloid formation.

Bioinformatic screens have predicted that over 250 human proteins contain prion-like domains (PrLD). These domains are hypothesized to have the same transmissible, amyloidogenic properties of PrP and known fungal proteins. As in yeast, proteins involved in gene expression and RNA binding seem to be particularly enriched in PrLD's, compared to other classes of protein. In particular, 29 of the known 210 proteins with an RNA recognition motif also have a putative prion domain. Meanwhile, several of these RNA-binding proteins have been independently identified as pathogenic in cases of ALS, FTLD-U, Alzheimer's disease, and Huntington's disease.

Role in neurodegenerative disease

The pathogenicity of prions and proteins with prion-like domains is hypothesized to arise from their self-templating ability and the resulting exponential growth of amyloid fibrils. The presence ofamyloid

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a fibrillar morphology of typically 7–13 nm in diameter, a β-sheet secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be stained by particular dyes, such as Congo red. In the human ...

fibrils in patients with degenerative diseases has been well documented. These amyloid fibrils are seen as the result of pathogenic proteins that self-propagate and form highly stable, non-functional aggregates. While this does not necessarily imply a causal relationship between amyloid and degenerative diseases, the toxicity of certain amyloid forms and the overproduction of amyloid in familial cases of degenerative disorders supports the idea that amyloid formation is generally toxic.

TDP-43

Specifically, aggregation ofTDP-43

Transactive response DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TAR DNA-binding protein 43 or TDP-43) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''TARDBP'' gene.

Structure

TDP-43 is 414 amino acid residues long. It consists of four domains: an N-ter ...

, an RNA-binding protein, has been found in ALS/MND patients, and mutations in the genes coding for these proteins have been identified in familial cases of ALS/MND. These mutations promote the misfolding of the proteins into a prion-like conformation. The misfolded form of TDP-43 forms cytoplasmic inclusions in affected neurons, and is found depleted in the nucleus. In addition to ALS/MND and FTLD-U, TDP-43 pathology is a feature of many cases of Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease and Huntington's disease. The misfolding of TDP-43 is largely directed by its prion-like domain. This domain is inherently prone to misfolding, while pathological mutations in TDP-43 have been found to increase this propensity to misfold, explaining the presence of these mutations in familial cases of ALS/MND. As in yeast, the prion-like domain of TDP-43 has been shown to be both necessary and sufficient for protein misfolding and aggregation.

RNPA2B1, RNPA1

Similarly, pathogenic mutations have been identified in the prion-like domains of heterogeneous nuclear riboproteins hnRNPA2B1 and hnRNPA1 in familial cases of muscle, brain, bone and motor neuron degeneration. The wild-type form of all of these proteins show a tendency to self-assemble into amyloid fibrils, while the pathogenic mutations exacerbate this behaviour and lead to excess accumulation.Alpha-synuclein

Bothmultiple system atrophy

Multiple system atrophy (MSA) is a rare neurodegenerative disorder characterized by tremors, slow movement, muscle rigidity, postural instability (collectively known as parkinsonism), autonomic dysfunction and ataxia. This is caused by progr ...

(MSA) and Parkinson's disease (PD) are associated with misfolded alpha-synuclein. In 2015, it was found that mice engineered to have a susceptible human version of alpha-synuclein become sick with MSA when injected in the brain with the brain homogenate of human MSA patients, but they do not get PD when injected with the brain homogenate of human PD patients. This suggests that the two diseases are different, with MSA being more transmissible. Misfolded alpha-synuclein from either Parkinson's disease or MSA can be detected by protein misfolding cyclic amplification (PMCA). The two forms, after PMCA, show different levels of fluorescence when bound to thioflavin T. This allows for distinguishing between the two diseases.

Weaponization

Prions could theoretically be employed as a weaponized agent. With potential fatality rates of 100%, prions could be an effective bioweapon, sometimes called a "biochemical weapon", because a prion is a biochemical. An unfavorable aspect is prions' very long incubation periods. Persistent heavy exposure of prions to theintestine

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascular system. T ...

might shorten the overall onset. Another aspect of using prions in warfare is the difficulty of detection and decontamination

Decontamination (sometimes abbreviated as decon, dcon, or decontam) is the process of removing contaminants on an object or area, including chemicals, micro-organisms, and/or radioactive substances. This may be achieved by chemical reaction, dis ...

.

History

In the 18th and 19th centuries, exportation of sheep from Spain was observed to coincide with a disease calledscrapie

Scrapie () is a fatal, degenerative disease affecting the nervous systems of sheep and goats. It is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), and as such it is thought to be caused by a prion. Scrapie has been known sin ...

. This disease caused the affected animals to ''"lie down, bite at their feet and legs, rub their backs against posts, fail to thrive, stop feeding and finally become lame"''. The disease was also observed to have the long incubation period that is a key characteristic of transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs). Although the cause of scrapie was not known back then, it is probably the first transmissible spongiform encephalopathy to be recorded.

In the 1950s, Carleton Gajdusek began research which eventually showed that kuru could be transmitted to chimpanzees by what was possibly a new infectious agent, work for which he eventually won the 1976 Nobel Prize

The Nobel Prizes ( ; ; ) are awards administered by the Nobel Foundation and granted in accordance with the principle of "for the greatest benefit to humankind". The prizes were first awarded in 1901, marking the fifth anniversary of Alfred N ...

. During the 1960s, two London-based researchers, radiation biologist Tikvah Alper

Tikvah Alper (22 January 1909 – 2 February 1995) trained as a physicist and became a distinguished radiobiologist. Among many other initiatives and discoveries, she was among the first to find evidence indicating that the infectious agent

...

and biophysicist John Stanley Griffith

John Stanley Griffith (1928–1972) was a British chemist, mathematician and biophysicist. He was the nephew of the distinguished British bacteriologist Frederick Griffith.

Career

Beginning as an undergraduate in mathematics at Trinity College, ...

, developed the hypothesis that the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies

Transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), also known as prion diseases, are a group of progressive, incurable, and fatal conditions that are associated with the prion hypothesis and affect the brain and nervous system of many animals, in ...

are caused by an infectious agent consisting solely of proteins. Earlier investigations by E.J. Field into scrapie

Scrapie () is a fatal, degenerative disease affecting the nervous systems of sheep and goats. It is one of several transmissible spongiform encephalopathies (TSEs), and as such it is thought to be caused by a prion. Scrapie has been known sin ...

and kuru had found evidence for the transfer of pathologically inert polysaccharides that only become infectious post-transfer, in the new host. Alper and Griffith wanted to account for the discovery that the mysterious infectious agent causing the diseases scrapie and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease

Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) is an incurable, always fatal neurodegenerative disease belonging to the transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE) group. Early symptoms include memory problems, behavioral changes, poor coordination, visu ...

resisted ionizing radiation

Ionizing (ionising) radiation, including Radioactive decay, nuclear radiation, consists of subatomic particles or electromagnetic waves that have enough energy per individual photon or particle to ionization, ionize atoms or molecules by detaching ...

. Griffith proposed three ways in which a protein could be a pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

.

In the first hypothesis

A hypothesis (: hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. A scientific hypothesis must be based on observations and make a testable and reproducible prediction about reality, in a process beginning with an educated guess o ...

, he suggested that if the protein is the product of a normally suppressed gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

, and introducing the protein could induce the gene's expression, that is, wake the dormant gene up, then the result would be a process indistinguishable from replication, as the gene's expression would produce the protein, which would then wake the gene in other cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network