Plagiolophus (mammal) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Plagiolophus'' (

"''P. minus''" (= ''Plagiolophus minor'') was amongst the fossil mammal species represented as sculptures in the

"''P. minus''" (= ''Plagiolophus minor'') was amongst the fossil mammal species represented as sculptures in the

In 1852, German palaeontologist

In 1852, German palaeontologist

In 1901, researchers

In 1901, researchers

''Plagiolophus'' belongs to the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major

''Plagiolophus'' belongs to the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major

The Palaeotheriidae is diagnosed in part as generally having

The Palaeotheriidae is diagnosed in part as generally having

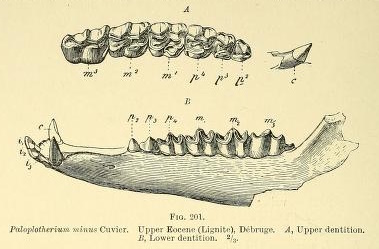

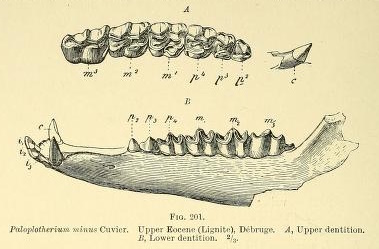

Derived palaeotheres are generally diagnosed as having selenolophodont upper molars and selenodont lower molars that are mesodont, or medium-crowned, in height. The canines strongly protrude and are separated from the premolars by medium to long

Derived palaeotheres are generally diagnosed as having selenolophodont upper molars and selenodont lower molars that are mesodont, or medium-crowned, in height. The canines strongly protrude and are separated from the premolars by medium to long  The oldest species of ''Plagiolophus'' had four upper and lower premolars whereas later species have evolutionarily lost one premolar in each jaw. However, ''P. annectens'' has well-documented deciduous premolars, totaling at four in each of each first permanent molar before they are replaced by the three permanent premolars. Remy argued that the first deciduous premolar was replaced by the first permanent premolar based on juvenille dentition of ''P. annectens'', but Kenneth D. Rose et al. in 2017 argued that the demonstrated evidence did not prove Remy's hypothesis, meaning that it requires further research for proof. Most adult ''P. annectens'' individuals have no reported deciduous or permanent first premolars in either jaw, probably due to displacement by the second premolars. The first premolar, when present, appears to be small, elongated, and narrow. The metacone cusp of P3 evolutionarily shrunk over time, and P4 at least sometimes lost its mesostyle cusp and often lost hypocone cusp. P4 has a high talonid cusp but lacks any entoconid cusp; the entoconid of P3 in comparison is short and a crescentlike shape. Within the molars, the ectoloph crest tends to stick out over the large cusps. The coronal

The oldest species of ''Plagiolophus'' had four upper and lower premolars whereas later species have evolutionarily lost one premolar in each jaw. However, ''P. annectens'' has well-documented deciduous premolars, totaling at four in each of each first permanent molar before they are replaced by the three permanent premolars. Remy argued that the first deciduous premolar was replaced by the first permanent premolar based on juvenille dentition of ''P. annectens'', but Kenneth D. Rose et al. in 2017 argued that the demonstrated evidence did not prove Remy's hypothesis, meaning that it requires further research for proof. Most adult ''P. annectens'' individuals have no reported deciduous or permanent first premolars in either jaw, probably due to displacement by the second premolars. The first premolar, when present, appears to be small, elongated, and narrow. The metacone cusp of P3 evolutionarily shrunk over time, and P4 at least sometimes lost its mesostyle cusp and often lost hypocone cusp. P4 has a high talonid cusp but lacks any entoconid cusp; the entoconid of P3 in comparison is short and a crescentlike shape. Within the molars, the ectoloph crest tends to stick out over the large cusps. The coronal

''P. minor'' is known by a few incomplete skeletons, the first of which was studied originally by Georges Cuvier in 1804. According to Remy, the gypsum skeleton has been lost; he stated that the individual was a pregnant female. It was figured by Cuvier and later Blainville in 1839–1864, and the latter naturalist also figured skeletal elements from the French commune of

''P. minor'' is known by a few incomplete skeletons, the first of which was studied originally by Georges Cuvier in 1804. According to Remy, the gypsum skeleton has been lost; he stated that the individual was a pregnant female. It was figured by Cuvier and later Blainville in 1839–1864, and the latter naturalist also figured skeletal elements from the French commune of

''Plagiolophus'' is characterized by the inclusion of small to medium-sized species, the skull base length ranging from to depending on the species. The length of the P2 to M3 dental row ranges from to . According to Remy, the basicranial (lower part of the skull) length of the Ma-PhQ-349 skull specimen of ''P. minor'' could have measured to long. Despite being a high, wide, and robust skull, ''P. minor'' is the smallest species of its genus, with the basal skull length being less than or equal to and the P2 to M3 dental row measuring . ''P. huerzeleri'' is mentioned to have been 20-25% larger than ''P. ministri'' with a basicranial length of and a P2 to M3 dental row length of to . The mandibular dental row of ''P. fraasi'' could measure to long whereas that of ''P. major'' could reach to long. The former species has an estimated skull length of while the latter's skull length could have measured . ''P. javali'' is known only from a male juvenile mandible with a dental row measuring long. With a potential adult skull length of about , ''P. javali'' is the largest species of ''Plagiolophus''.

Remy in 2004 calculated that the smallest species ''P. minor'' could have weighed less than . He also calculated ''P. huerzeleri'' to have a body weight range of to . ''P. major'' has an estimated weight range of to while ''P. fraasi'' has an estimated weight range of to . ''P. javali'', as the largest species of ''Plagiolophus'', could have had a body weight of over . Later in 2015, he placed a body weight estimate of ''P. annectens'' at about , ''P. cartailhaci'' at , and ''P. mamertensis'' at . Jamie A. MacLaren and Sandra Nauwelaerts in 2020 estimated the weight of ''P. minor'' at , ''P. annectens'' at , and ''P. major'' at . In 2022, Leire Perales-Gogenola et al. made five weight estimates of different populations of ''Plagiolophus''. They stated that ''P. mazateronensis'' from Mazaterón has a body weight of . According to the authors, ''P. minor'' from St. Capraise d'Eymet potentially weighed , and ''P. ministri'' from Villebramar weighed . They also said that ''P. annectens'' from Euzet weighed while the same species from Roc de Santa I measured . The same year, Perales-Gogenola et al. estimated that ''P. mazateronensis'' has a weight estimate range of to .

''Plagiolophus'' is characterized by the inclusion of small to medium-sized species, the skull base length ranging from to depending on the species. The length of the P2 to M3 dental row ranges from to . According to Remy, the basicranial (lower part of the skull) length of the Ma-PhQ-349 skull specimen of ''P. minor'' could have measured to long. Despite being a high, wide, and robust skull, ''P. minor'' is the smallest species of its genus, with the basal skull length being less than or equal to and the P2 to M3 dental row measuring . ''P. huerzeleri'' is mentioned to have been 20-25% larger than ''P. ministri'' with a basicranial length of and a P2 to M3 dental row length of to . The mandibular dental row of ''P. fraasi'' could measure to long whereas that of ''P. major'' could reach to long. The former species has an estimated skull length of while the latter's skull length could have measured . ''P. javali'' is known only from a male juvenile mandible with a dental row measuring long. With a potential adult skull length of about , ''P. javali'' is the largest species of ''Plagiolophus''.

Remy in 2004 calculated that the smallest species ''P. minor'' could have weighed less than . He also calculated ''P. huerzeleri'' to have a body weight range of to . ''P. major'' has an estimated weight range of to while ''P. fraasi'' has an estimated weight range of to . ''P. javali'', as the largest species of ''Plagiolophus'', could have had a body weight of over . Later in 2015, he placed a body weight estimate of ''P. annectens'' at about , ''P. cartailhaci'' at , and ''P. mamertensis'' at . Jamie A. MacLaren and Sandra Nauwelaerts in 2020 estimated the weight of ''P. minor'' at , ''P. annectens'' at , and ''P. major'' at . In 2022, Leire Perales-Gogenola et al. made five weight estimates of different populations of ''Plagiolophus''. They stated that ''P. mazateronensis'' from Mazaterón has a body weight of . According to the authors, ''P. minor'' from St. Capraise d'Eymet potentially weighed , and ''P. ministri'' from Villebramar weighed . They also said that ''P. annectens'' from Euzet weighed while the same species from Roc de Santa I measured . The same year, Perales-Gogenola et al. estimated that ''P. mazateronensis'' has a weight estimate range of to .

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and  The Geiseltal Obere Mittelkhole locality, dating to MP13, records fossils of ''P. cartieri'' along with the herpetotheriid ''

The Geiseltal Obere Mittelkhole locality, dating to MP13, records fossils of ''P. cartieri'' along with the herpetotheriid ''

The Late Eocene marks the latest appearances of ''P. annectens'' and ''P. mazateronensis'' at MP17 followed by the first appearances of ''P. oweni'' and ''P. minor'' at MP18 (the former of which is restricted to the unit). MP20 records both the continuous occurrence of ''P. minor'' and the restricted appearances of ''P. fraasi'' and ''P. major''. Within the late Eocene, the

The Late Eocene marks the latest appearances of ''P. annectens'' and ''P. mazateronensis'' at MP17 followed by the first appearances of ''P. oweni'' and ''P. minor'' at MP18 (the former of which is restricted to the unit). MP20 records both the continuous occurrence of ''P. minor'' and the restricted appearances of ''P. fraasi'' and ''P. major''. Within the late Eocene, the

The

The

Although the Eocene-Oligocene transition marked long-term drastic cooling global climates, western Eurasia was still dominated by humid climates, albeit with dry winter seasons in the Oligocene. Europe during the Oligocene had environments largely adapted to winter-dry seasons and humid seasons that were composed of three separate vegetational belts by latitude, with temperate needleleaf- broadleaved or purely broadleaved deciduous forests aligning with the northernmost belt between 40°N and 50°N, the middle belt of warmth-adapted mixed

Although the Eocene-Oligocene transition marked long-term drastic cooling global climates, western Eurasia was still dominated by humid climates, albeit with dry winter seasons in the Oligocene. Europe during the Oligocene had environments largely adapted to winter-dry seasons and humid seasons that were composed of three separate vegetational belts by latitude, with temperate needleleaf- broadleaved or purely broadleaved deciduous forests aligning with the northernmost belt between 40°N and 50°N, the middle belt of warmth-adapted mixed

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: (oblique) + (crest) meaning "oblique crest") is an extinct genus of equoids belonging to the family Palaeotheriidae

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the livin ...

. It lived in Europe from the middle Oligocene to the early Oligocene. The type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

''P. minor'' was initially described by the French naturalist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

in 1804 based on postcranial material including a now-lost skeleton originally from the Paris Basin

The Paris Basin () is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in ...

. It was classified to ''Palaeotherium

''Palaeotherium'' is an extinct genus of Equoidea, equoid that lived in Europe and possibly the Middle East from the Middle Eocene to the Early Oligocene. It is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, a group exclusive to the Paleogene, Palaeogen ...

'' the same year but was reclassified to the subgenus ''Plagiolophus'', named by Auguste Pomel

Nicolas Auguste Pomel (20 September 1821 – 2 August 1898) was a French geologist, paleontologist and botanist. He worked as a mines engineer in Algeria and became a specialist in north African vertebrate fossils. He was Senator of Algeria for Or ...

in 1847. ''Plagiolophus'' was promoted to genus rank by subsequent palaeontologists and today includes as many as seventeen species. As proposed by the French palaeontologist Jean A. Remy in 2004, it is defined by three subgenera

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

: ''Plagiolophus'', ''Paloplotherium'', and ''Fraasiolophus''.

''Plagiolophus'' is an evolutionarily derived member of its family with tridactyl (or three-toed) forelimbs and hindlimbs. It has longer postcanine diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

ta (gaps between teeth) compared to ''Palaeotherium'' and brachyodont (low-crowned) dentition that evolutionarily progressed towards hypsodonty (high-crowned) in response to climatic trends. It is also defined in part by an elongated facial region, deep nasal notch

In the human skull, the frontal bone or sincipital bone is an unpaired bone which consists of two portions.''Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bony ...

, and orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

s for the eyes that are more positioned backwards compared to those of ''Palaeotherium''. ''Plagiolophus'', as a species-rich genus, has a wide body mass range extending from less than in the smallest species ''P. minor'' to over in the largest species ''P. javali''. The postcranial builds of several species suggest that some had stockier body builds (''P. annectens'', ''P. fraasi'', ''P. javali'') while some others were lightly built for cursorial (running) adaptations (''P. minor'', ''P. ministri'', ''P. huerzeleri'').

''Plagiolophus'' and other members of the Palaeotheriinae likely descended from the earlier subfamily Pachynolophinae in the middle Eocene. Western Europe, where ''Plagiolophus'' was largely present, was an archipelago that was isolated from the rest of Eurasia, meaning that it lived in an environment with various other faunas that also evolved with strong levels of endemism

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

. While many species had short temporal ranges, ''P. minor'' was long-lasting to the extent that researchers observed trends in changes in its dietary habits. More specifically, ''P. minor'' over time was observed to have consumed less hard foods (fruits, seeds) and became more specialized but less selective towards tough, abrasive, and older leaves in response to environmental trends in the late Eocene to early Oligocene. Its dietary habits would have allow it to niche partition with other palaeotheres like ''Palaeotherium'' and '' Leptolophus''. ''Plagiolophus'' was consistently diverse for much of its evolutionary history and survived far past the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

* Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Ar ...

extinction event, likely because some of its species were well-adapted towards major environmental trends as a result of their dietary changes and cursorial nature. It was able to adapt to more seasonal climates after the Grande Coupure and coexisted with immigrant faunas from the faunal turnover event. Its eventual extinction by the later early Oligocene marked the complete extinction of the Palaeotheriidae.

Taxonomy

Research history

Early history

In 1804, the French naturalistGeorges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

, having established the genus ''Palaeotherium

''Palaeotherium'' is an extinct genus of Equoidea, equoid that lived in Europe and possibly the Middle East from the Middle Eocene to the Early Oligocene. It is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, a group exclusive to the Paleogene, Palaeogen ...

'' and some of its species (''P. medium'' and ''P. magnum''), recognized a third species ''Palaeotherium minus'' based on some postcranial fossils from the gypsum quarries of the outskirts of Paris (known as the Paris Basin

The Paris Basin () is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in ...

), although he did not elaborate further on them. In a later journal of the same year, he described a nearly completely skeleton from the quarries of the French commune

A () is a level of administrative division in the French Republic. French are analogous to civil townships and incorporated municipalities in Canada and the United States; ' in Germany; ' in Italy; ' in Spain; or civil parishes in the Uni ...

of Pantin

Pantin () is a Communes of France, commune in the northeastern suburbs of Paris, Île-de-France, France. It is located from the Kilometre Zero, centre of Paris. In 2019 its population was estimated to be 59,846. Pantin is located on the edge of ...

, originally found by the French naturalist Auguste Nicholas de Saint-Genis. According to Cuvier, the quarry workers previously thought the skeleton to be of a ram, and it was presented as such in public newspapers. The French prefect Nicolas Frochot later acquired it and brought it to the National Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History ( ; abbr. MNHN) is the national natural history museum of France and a of higher education part of Sorbonne University. The main museum, with four galleries, is located in Paris, France, within the ...

, where Cuvier was then able to observe that it must have been a skeleton of a ''Palaeotherium'' species. He noted that the majority of the fossil bones were detached from others and/or damaged but that postcranial fossils such as scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

e, humeri

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of ...

, femora

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The top of the femur fits in ...

, vertebrae

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

, and rib

In vertebrate anatomy, ribs () are the long curved bones which form the rib cage, part of the axial skeleton. In most tetrapods, ribs surround the thoracic cavity, enabling the lungs to expand and thus facilitate breathing by expanding the ...

s were found. The naturalist also provided a figure of the skeleton within the journal.

In 1812, Cuvier published published his drawing of a skeletal reconstruction of ''P. minus'' based on known fossil remains of the species including the mostly complete skeleton. He also suggested theoretical lifestyles of several ''Palaeotherium'' species. In particular, he suggested that ''P. minus'' resembled a tapir

Tapirs ( ) are large, herbivorous mammals belonging to the family Tapiridae. They are similar in shape to a Suidae, pig, with a short, prehensile nose trunk (proboscis). Tapirs inhabit jungle and forest regions of South America, South and Centr ...

, was smaller than a sheep, and was cursorial based on the slender morphologies of its leg bones. Such a behaviour and small size would have differed from other species of ''Palaeotherium'', several of which according to Cuvier had stockier limb bone builds. He also identified that ''P. medium'', ''P. magnum'', ''P. minus'', ''P. crassum'', and ''P. curtum'' were all tridactyl, or three-toed.

"''P. minus''" (= ''Plagiolophus minor'') was amongst the fossil mammal species represented as sculptures in the

"''P. minus''" (= ''Plagiolophus minor'') was amongst the fossil mammal species represented as sculptures in the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are a series of sculptures of dinosaurs and other extinct animals in the London borough of Bromley's Crystal Palace Park. Commissioned in 1852 to accompany the Crystal Palace after its move from the Great Exhi ...

attraction in the Crystal Palace Park

Crystal Palace Park is a park in south-east London, Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. It was laid out in the 1850s as a pleasure ground, centred around the re-location of The Crystal Palace – the largest glass ...

in the United Kingdom, open to the public since 1854 and constructed by English sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (8 February 1807 – 27 January 1894) was an English sculptor and natural history artist renowned for his work on the life-size models of dinosaurs in the Crystal Palace Park in south London. The models, accurately ...

. The ''Plagiolophus'' sculpture is smaller than the ''P. magnum'' and ''P. medium'' sculptures and is in a sitting position unlike the other two. The models' resemblances to tapirs reflected early perceptions that the palaeothere species resembled them in body plan appearances. Despite this, the sculptures differ from living tapirs in several ways, such as shorter plus taller faces, higher eye positions, slender legs, longer tails, and the presence of three toes on the forelimbs unlike the four toes of the forelimbs of tapirs.

Hawkins and other workers seemingly used Cuvier's research for reference to the anatomy of ''P. minor'' and reproduced its size and proportions accordingly. The ''P. minor'' sculpture, sheep-sized, originally had a short head that probably measured about in length and had pointed ears, large eyes, long lips, a stocky proboscis, a muscular neck, and a short plus slender tail. It looks similar to the ''P. medium'' sculpture overall but lacks skin details. Although the original head's form is poorly known, it appeared to have been longer and more robust than that of ''P. medium''. Within the later half of the 20th century, the original head was lost and replaced with a head cast of ''P. medium''. Because the size and form of the head made it difficult to attach to the ''P. minor'' body normally, the back portion of the cranium was removed and the neck lengthened. This resulted in the sculpture appearing to look forward instead of upwards like before. The ''P. minor'' sculpture lost its head twice more, once recently in 2014 when its head was tossed into a lake of the Crystal Palace by an unknown criminal and had to be recovered.

Later 19th century research history

In 1846, French palaeontologistAuguste Aymard

Auguste Aymard (5 December 1808 – 26 June 1889) was a French prehistorian and palaeontologist who lived and died in Puy-en-Velay (Haute-Loire). He described the fossil '' Entelodon magnus'' and the fossil genera ''Anancus

''Anancus'' is an ...

recorded a mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

with teeth from the French department

In the administrative divisions of France, the department (, ) is one of the three levels of government under the national level (" territorial collectivities"), between the administrative regions and the communes. There are a total of 101 ...

of Haute-Loire

Haute-Loire (; or ''Naut Leir''; English: Upper Loire) is a landlocked department in the Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region of south-central France. Named after the Loire River, it is surrounded by the departments of Loire, Ardèche, Lozère, Canta ...

, noting that it was the approximate size of that of ''Palaeotherium curtum'' but had different molar morphologies from it and the small-sized "''P. minus''", establishing the name ''P. ovinum''. The year after in 1847, the French palaeontologist Auguste Pomel

Nicolas Auguste Pomel (20 September 1821 – 2 August 1898) was a French geologist, paleontologist and botanist. He worked as a mines engineer in Algeria and became a specialist in north African vertebrate fossils. He was Senator of Algeria for Or ...

erected the ''Palaeotherium'' subgenus

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

''Plagiolophus'', which he reclassified ''P. minus'' to. The genus name derives in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

from ("oblique") and ("crest") meaning "oblique crest".

British palaeontologist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

in 1848 wrote about a nearly complete lower jaw with both deciduous and permanent dental sets that was uncovered from the Eocene beds of Hordle

Hordle is a village and civil parish in the county of Hampshire, England. It is situated between the Solent coast and the New Forest, and is bordered by the towns of Lymington and New Milton. Like many New Forest parishes Hordle has no vill ...

, England by Alexander Pytts Falconer, observing that it had one less premolar

The premolars, also called premolar Tooth (human), teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the Canine tooth, canine and Molar (tooth), molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per dental terminology#Quadrant, quadrant in ...

for a total of 3 of them than in other species of ''Palaeotherium'' and erecting the genus ''Paloplotherium'' based on the mandible. He then described a cranium

The skull, or cranium, is typically a bony enclosure around the brain of a vertebrate. In some fish, and amphibians, the skull is of cartilage. The skull is at the head end of the vertebrate.

In the human, the skull comprises two prominent ...

belonging to ''Paloplotherium'' that similarly had nearly complete dentition but evolutionarily lost a premolar. After comparing the dentition to those of both ''Palaeotherium'' and ''Anoplotherium

''Anoplotherium'' is the type genus of the extinct Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyl family Anoplotheriidae, which was endemic to Western Europe. It lived from the Late Eocene to the earliest Oligocene. It was the fifth fossil mammal genus to be ...

'', he determined that the dentition of ''Paloplotherium'' was similar to that of the former but differed mainly by the absence of the first premolar. He wrote that the permanent dental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of ''Paloplotherium'' is for a total of 40 teeth and erected the species ''Paloplotherium annectens''. ''Paloplotherium'' derives from the Ancient Greek words παλαιός ("ancient"), ὅπλον ("arms"), and θήρ ("wild beast") meaning "ancient armed beast".

In 1852, German palaeontologist

In 1852, German palaeontologist Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer

Christian Erich Hermann von Meyer (3 September 1801 – 2 April 1869), known as Hermann von Meyer, was a German palaeontologist. He was awarded the 1858 Wollaston medal by the Geological Society of London.

Life

He was born in Frankfurt am ...

, recognizing ''Plagiolophus'' as a distinct genus and emending ''Plagiolophus minus'' to ''Plagiolophus minor'', erected the species ''P. fraasi'' based on fossils from the German locality of Frohnstetten originally found by Oscar Fraas

Oscar Friedrich von Fraas (17 January 1824 in Lorch (Württemberg) – 22 November 1897 in Stuttgart) was a German clergyman, paleontologist and geologist. He was the father of geologist Eberhard Fraas (1862–1915).

Biography

He studied theol ...

. Fraas had studied fossils of palaeotheres

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the living ...

from Frohnstetten since 1851, assembling a complete skeleton of ''P. minor'' using fossils from there in 1853. In 1853, Pomel listed in the genus ''Plagiolophus'' multiple previously recognized species, namely ''P. ovinus'' (reclassified from ''Palaeotherium'' and emended from ''P. ovinum''), ''P. minor'', and ''P. annectens'' (by extent synonymizing ''Paloplotherium'' with ''Plagiolophus''). He also erected another species ''P. tenuirostris''. In 1862, Swiss palaeontologist Ludwig Ruetimeyer

(Karl) Ludwig Rütimeyer (26 February 1825 in Biglen, Canton of Bern – 25 November 1895 in Basel) was a Swiss zoologist, anatomist and paleontologist, who is considered one of the fathers of zooarchaeology.

Career

Rütimeyer studied at the Univ ...

established ''P. minutus'' based on dental remains from the Swiss locality of Egerkingen

Egerkingen is a Municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the district of Gäu (district), Gäu in the Cantons of Switzerland, canton of Solothurn (canton), Solothurn in Switzerland.

History

Egerkingen is first mentioned in 1201 as ''in Egri ...

.

Not all taxonomists agreed on ''Paloplotherium'' as a synonymous genus. In 1865 for example, French palaeontologist Jean Albert Gaudry

Jean Albert Gaudry (16 September 1827 – 27 November 1908) was a French geologist and palaeontologist. He was born at St Germain-en-Laye, and was educated at the Catholic Collège Stanislas de Paris. He was a notable proponent of theistic evolu ...

recognized ''Paloplotherium'' as valid genus instead of ''Plagiolophus'', grouping ''P. minor'', ''P. ovinus'', and ''P. annectens'' into it and erecting another species ''P. codiciense''. In 1869, Swiss palaeontologists François Jules Pictet de la Rive

François-Jules Pictet de la Rive (27 September 180915 March 1872) was a Switzerland, Swiss zoologist and palaeontologist.

Biography

He was born in Geneva. He graduated B. Sc. at Geneva in 1829, and pursued his studies for a short time at Paris, ...

and Aloïs Humbert

Aloïs Humbert (22 September 1829 – 13 May 1887) was a Swiss naturalist and paleontologist who specialized in the study of myriapods. He also described new vertebrates (fishes, reptiles, mammals), molluscs and flatworms.

Biography

Humbert was ...

wrote that ''Palaeotherium'', ''Paloplotherium'', and ''Plagiolophus'' were all valid genera and erected two species for the latter: ''P. siderolithicus'' using fossil molars from a museum collection and ''P. valdensis'' based on a mandible that was smaller in proportion than that of ''P. minor''. In 1877, French naturalist Henri Filhol

Henri Filhol

Henri Filhol (13 May 1843 – 28 April 1902) was a French medical doctor, malacologist and naturalist born in Toulouse. He was the son of Édouard Filhol (1814-1883), curator of the Muséum de Toulouse.

After receiving his early e ...

erected ''Paloplotherium Javalii'' based on fossil jaws including that from the fossil collection of the French official Ernest Javal, who he named the species after. Ruetimeyer in 1891 erected another species ''Paloplotherium magnum'', stating that its size based on fossil material would have been that of ''Palaeotherium magnum''.

20th-21st century taxonomy

In 1901, researchers

In 1901, researchers Charles Depéret

Charles Jean Julien Depéret (25 June 1854 – 18 May 1929) was a French geologist and paleontologist. He was a member of the French Academy of Sciences, the Société géologique de France

and G. Carrière designated the species name ''Paloplotherium lugdunense'' to fossil material originally from the fossil deposits from the French commune of Lissieu

Lissieu () is a commune in the Metropolis of Lyon in Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region in eastern France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Metropolis of Lyon

The following is a list of the 58 communes of the Lyon Metropolis, France

F ...

. They said that the species was barely larger than ''P. codiciense'' and that it was also known from the locality of Robiac. The year after in 1902, Swiss palaeontologist Hans Georg Stehlin

Hans Georg Stehlin (1870–1941) was a Swiss paleontologist and geologist.

Stehlin specialized in vertebrate paleontology, particularly the study of Cenozoic mammals. He published numerous scientific papers on primates and ungulates. He was presid ...

erected ''Paloplotherium Rütimeyeri'', but he only wrote that it was known from Egerkingen and did not elaborate further on it. In 1904, Swiss palaeontologist Hans Georg Stehlin

Hans Georg Stehlin (1870–1941) was a Swiss paleontologist and geologist.

Stehlin specialized in vertebrate paleontology, particularly the study of Cenozoic mammals. He published numerous scientific papers on primates and ungulates. He was presid ...

synonymized ''Paloplotherium magnum'' with ''Palaeotherium castrense'' and erected two species of ''Plagiolophus'': ''P. Nouleti'' from a fossil mandible from the French commune of Viviers-lès-Montagnes

Viviers-lès-Montagnes (; ) is a commune in the Tarn department in southern France.

See also

*Communes of the Tarn department

The following is a list of the 314 communes of the Tarn department of France.

The communes cooperate in the fo ...

and ''P. Cartailhaci'' using fossils from the commune of Peyregoux. In one of his monographies, written the same year, Stehlin erected ''Palaeotherium Rütimeyeri'' with official fossil descriptions to replace the previous species name and synonymized ''Paloplotherium javali'' with ''Plagiolophus fraasi''. He also erected the species ''P. cartieri'' based on Egerkingen fossils, arguing that its size was between ''P. annectens'' and ''P. minor'' plus that its fossils resembled those of ''P. codidiciensis''. In 1917, French palaeontologist Charles Depéret

Charles Jean Julien Depéret (25 June 1854 – 18 May 1929) was a French geologist and paleontologist. He was a member of the French Academy of Sciences, the Société géologique de France

erected the species ''P. Oweni'' (also recognizing it by the name ''P. annectens'' mut. ''Oweni'' from fossils in the commune of Gargas, arguing that it was a more advanced species of ''Plagiolophus'' based on the size and morphology of its premolars. He also reclassified "''Paloplotherium''" ''codiciense'' into its own genus '' Paraplagiolophus''. In 1965, French palaeontologist Jean Albert Remy erected the genus '' Leptolophus'', reclassifying ''P. nouleti'' into the taxon.

In 1986, British palaeontologist Jerry J. Hooker listed ''Paloplotherium'' as a synonym of ''Palaeotherium'' and listed ''P. minor'', ''P. cartieri'', ''P. lugdunensis'' (emended name), ''P. cartailhaci'', ''P. annectens'', ''P. fraasi'', and ''P. javalii'' as valid species, although he doubted that ''P. javalii'' was distinct from ''P. fraasi''. He also erected ''P. curtisi'' using fossils from fragmentary cranial remains from the Barton Beds

Barton Beds (now the Barton Group) is the name given to a series of grey and brown clays, with layers of sand, of Upper Eocene age (around 40 million years old), which are found in the Hampshire Basin of southern England. They are particularly we ...

of the United Kingdom and recognized two subspecies: ''P. curtisi curtisi'' and ''P. curtisi creechensis''. The species was named after an individual named R.J. Curtis, who found the specimens for the former subspecies. In 1989, palaeontologists Michel Brunet Michel Brunet may refer to:

* Michel Brunet (historian) (1917–1985), Canadian historian

* Michel Brunet (paleontologist)

Michel Brunet (born April 6, 1940) is a French paleontologist and a professor at the Collège de France between 2008 and 20 ...

and Yves Jehenne considered ''Paloplotherium'' to be distinct from ''Palaeotherium'' and erected for the former genus two additional species: ''P. majus'' from the fossil collections of the Quercy Phosphorites Formation

The Quercy Phosphorites Formation (French language, French: ''Phosphorites du Quercy''; ) is a Formation (geology), geologic formation and lagerstätte in Occitania (administrative region), Occitanie, southern France. It preserves fossils dated to ...

and ''P. ministri'' from the French commune of Villebramar. Remy in 1994, however, rejected the claim by Brunet and Jehenne that ''Paloplotherium'' was a distinct genus from ''Plagiolophus'', instead suggesting to convert the former into a ''Plagiolophus'' subgenus.

In 1994, Spanish palaeontologist Miguel Ángel Cuesta Ruiz-Colmenares erected two ''Plagiolophus'' species, the first being ''P. casasecaensis'', named after the Spanish municipality of Casaseca de Campeán within the Duero Basin. The second species he recognized was ''P. mazateronensis'', also from the Duero Basin; it was named after the Mazaterón province in the municipality of Soria

Soria () is a municipality and a Spanish city, located on the Douro river in the east of the autonomous community of Castile and León and capital of the province of Soria. Its population is 38,881 ( INE, 2017), 43.7% of the provincial populatio ...

. In 1997, another Spanish palaeontologist Lluís Checa Soler analyzed a dental specimen, stating his belief that it belonged to ''Plagiolophus'' and that the species would be defined by its smaller size and primitive characteristics compared to other species. He proposed the name ''P. plesiomorphicus'' but sought to not formally define it until more complete material assigned to the species was found.

In 2000, Remy described a skull of a male ''Plagiolophus'' individual that was within a sandstone block originally from the French department of Vaucluse

Vaucluse (; or ) is a department in the southeastern French region of Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur. It had a population of 561,469 as of 2019.

, assigning it the new species name ''P. huerzeleri''. The species was named after Johannes Hürzeler, Swiss palaeontologist and former director of the oteology department of the Natural History Museum of Basel

Natural History Museum Basel () is a natural history museum in Basel, Switzerland that houses wide-ranging collections focused on the fields of zoology, entomology, mineralogy, anthropology, osteology and paleontology. It has over 11 million obje ...

. Remy had also emended ''P. majus'' to ''P. major'' and suggested both ''Plagiolophus'' and ''Paloplotherium'' as valid subgenera for ''Plagiolophus''. Remy, in 2004, followed up by erecting ''P. ringeadei'', named after Ruch fossil deposit discoverer Michel Ringead and known by a skull of an adult female with cheek teeth, and ''P. mamertensis'', which was assigned a left maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

with partial dentition from Robiac for a holotype

A holotype (Latin: ''holotypus'') is a single physical example (or illustration) of an organism used when the species (or lower-ranked taxon) was formally described. It is either the single such physical example (or illustration) or one of s ...

specimen. He also listed ''P. minutus'' and ''P. plesiomorphicus'' both as '' nomen dubia'' (doubtful taxon names). Remy reiterated both ''Plagiolophus'' and ''Paloplotherium'' as defined subgenera for ''Plagiolophus'' and created a third subgenus ''Fraasiolophus''.

Classification

''Plagiolophus'' belongs to the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major

''Plagiolophus'' belongs to the Palaeotheriidae, largely considered to be one of two major hippomorph

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of ungulates. The order includes about 17 living species divided into three families: Equidae (horses, asses, and zebras), Rhinocerotidae (rhinoceroses), and Tapiridae (tapirs). They typi ...

families in the superfamily Equoidea

Equoidea is a superfamily of hippomorph perissodactyls containing the Equidae, Palaeotheriidae, and other basal equoids of unclear affinities, of which members of the genus '' Equus'' are the only extant species. The earliest fossil record of ...

, the other being the Equidae

Equidae (commonly known as the horse family) is the Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic Family (biology), family of Wild horse, horses and related animals, including Asinus, asses, zebra, zebras, and many extinct species known only from fossils. The fa ...

. Alternatively, some authors have proposed that equids are more closely related to the Tapiromorpha

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of ungulates. The order includes about 17 living species divided into three families: Equidae (horses, asses, and zebras), Rhinocerotidae (rhinoceroses), and Tapiridae (tapirs). They typi ...

than to the Palaeotheriidae. It is also usually thought to consist of two families, the Palaeotheriinae and Pachynolophinae

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the living ...

; a few authors alternatively have argued that pachynolophines are more closely related to other perissodactyl groups than to palaeotheriines. Some authors have also considered the Plagiolophinae to be a separate subfamily, while others group its genera into the Palaeotheriinae. ''Plagiolophus'' has also been suggested to belong to the tribe Plagiolophini

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the living ...

, one of three proposed tribes within the Palaeotheriinae along with the Leptolophini

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the living ...

and Palaeotheriini. The Eurasian distribution of the palaeotheriids (or palaeotheres) were in contrast to equids, which are generally thought to have been an endemic radiation in North America. Some of the most basal equoids of the European landmass are of uncertain affinities, with some genera being thought to potentially belong to the Equidae. Palaeotheriids are well-known for having lived in western Europe during much of the Palaeogene but were also present in eastern Europe, possibly the Middle East, and, in the case of pachynolophines (or pachynolophs), Asia.

The Perissodactyla makes its earliest known appearance in the European landmass in the MP7 faunal unit of the Mammal Palaeogene zones. During the temporal unit, many genera of basal equoids such as ''Hyracotherium

''Hyracotherium'' ( ; "hyrax-like beast") is an extinction, extinct genus of small (about 60 cm in length) perissodactyl ungulates that was found in the London Clay formation. This small, fox-sized animal is (for some scientists) considered t ...

'', ''Pliolophus

''Pliolophus'' is an extinct equid that lived in the Early Eocene of Britain.

See also

* Evolution of the horse

The evolution of the horse, a mammal of the family Equidae, occurred over a geologic time scale of 50 million years, transformin ...

'', ''Cymbalophus

Tapiroidea is a superfamily of perissodactyls which includes the modern tapirs and their extinct relatives. Taxonomically, they are placed in suborder Ceratomorpha along with the rhino superfamily, Rhinocerotoidea. The first members of Tapiroide ...

'', and ''Hallensia

''Hallensia'' is an extinct genus of perissodactyl

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of Ungulate, ungulates. The order includes about 17 living species divided into three Family (biology), families: Equidae (wild horse ...

'' made their first appearances there. A majority of the genera persisted to the MP8-MP10 units, and pachynolophines such as ''Propalaeotherium

''Propalaeotherium'' was an early genus of perissodactyl Endemism, endemic to Europe and Asia during the early Eocene. There are currently six recognised species within the genus, with ''P. isselanum'' as the type species (named by Georges Cuvier ...

'' and '' Orolophus'' arose by MP10. The MP13 unit saw the appearances of later pachynolophines such as '' Pachynolophus'' and '' Anchilophus'' along with definite records of the first palaeotheriines such as ''Palaeotherium'' and ''Paraplagiolophus''. The palaeotheriine ''Plagiolophus'' has been suggested to have potentially made an appearance by MP12. It was by MP14 that the subfamily proceeded to diversify, and the pachynolophines were generally replaced but still reached the late Eocene. In addition to more widespread palaeothere genera such as ''Plagiolophus'', ''Palaeotherium'', and ''Leptolophus'', some of their species reaching medium to large sizes, various other palaeothere genera that were endemic to the Iberian Peninsula, such as '' Cantabrotherium'', '' Franzenium'', and '' Iberolophus'', appeared by the middle Eocene.

The phylogenetic tree for several members of the family Palaeotheriidae within the order Perissodactyla (including three outgroups) as created by Remy in 2017 and followed by Remy et al. in 2019 is defined below:

As shown in the above phylogeny, the Palaeotheriidae is defined as a monophyletic

In biological cladistics for the classification of organisms, monophyly is the condition of a taxonomic grouping being a clade – that is, a grouping of organisms which meets these criteria:

# the grouping contains its own most recent co ...

clade, meaning that it did not leave any derived descendant groups in its evolutionary history. ''Hyracotherium'' ''sensu stricto'' (in a strict sense) is defined as amongst the first offshoots of the family and a member of the Pachynolophinae. "''H.''" ''remyi'', formerly part of the now-invalid genus ''Propachynolophus'', is defined as a sister taxon to more derived palaeotheriids. Both ''Pachynolophus'' and '' Lophiotherium'', defined as pachynolophines, are defined as monophyletic genera. The other pachynolophines ''Eurohippus

''Eurohippus'' is an extinct genus of equoid ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with t ...

'' and ''Propalaeotherium'' consistute a paraphyletic clade in relation to members of the derived and monophyletic subfamily Palaeotheriinae (''Leptolophus'', ''Plagiolophus'', and ''Palaeotherium''), thus making Pachynolophinae a paraphyletic subfamily clade.

List of lineages

Unlike ''Palaeotherium'' where many species have subspecies, ''Plagiolophus'' only has one species with defined subspecies, ''P. curtisi''. All species of ''Plagiolophus'' are classified in one of three subgenera. The following table defines the species and subspecies of ''Plagiolophus'' and additional information about them:Description

Skull

The Palaeotheriidae is diagnosed in part as generally having

The Palaeotheriidae is diagnosed in part as generally having orbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an physical body, object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an satellite, artificia ...

that are wide open in the back area and are located in the middle of the skull or in a slight frontal area of it. The nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

s are slightly extensive to very extensive in depth. ''Plagiolophus'' is diagnosed in part as having skull lengths that vary by species and range from to . It is also defined by many other unique cranial traits, among them being the skull's elongated facial region, especially in later species, that is more well-developed compared to that of ''Palaeotherium''. The maxilla, at the area with the canine, is wide; the muzzle in comparison is thin. The nasal notch

In the human skull, the frontal bone or sincipital bone is an unpaired bone which consists of two portions.''Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bony ...

, found on the front lower edge of the maxilla, is generally deep, ranges from P1 to M1, and has its lower edges formed from those of the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

and maxilla. The zygomatic arch

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of temporal bone, zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the ...

is narrow and elevates up to the back of the orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

. The mandibular symphysis

In human anatomy, the facial skeleton of the skull the external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the mandibular symphysis (Latin: ''symphysis menti'') or line of junction where the two lateral ha ...

, the middle of the mandible, is elongated and contains projecting incisors. The horizontal ramus (or body) of the mandible is wide from front to back and has a prominent coronoid process. The subgenus ''Plagiolophus'' is defined by a shallow nasal notch that is always located in front of P2, the lack of any preorbital fossa and a thinner body of the mandible compared to that of ''Paloplotherium''. ''Paloplotherium'' contrasts from ''Plagiolophus'' in having a deep nasal notch is always behind P2 and a larger skull size, but the former also shares the lack of any preorbital fossae. ''Plagiolophus'' also differs from ''Paloplotherium'' in having a thinner horizontal ramus of the mandible. ''Fraasiolophus'' differs from the other two subgenera solely by the presence of a deep preorbital fossa.

The skull of ''Plagiolophus'' appears slightly triangular in shape, has a maximum width either above or in front of where the mandible articulates with other skull bones, and has a wider front area compared to that of ''Leptolophus''. The skull length of ''Plagiolophus'' generally increases over time as part of an evolutionary trend of species. For instance, the skull of ''P. huerzeleri'', one of the latest species to have existed, has a more elongated and skull (making it more equinelike) than that of ''P. annectens'', an earlier-appearing species; the former species also has a longer anterior orbital region, a higher orbit position, implying different arrangements of facial muscles compared to the latter. The orbit of ''Plagiolophus'' is slightly behind the midlength of the skull, making its position more similar to that of the Palaeogene equid ''Mesohippus

''Mesohippus'' (Greek language, Greek: / meaning "middle" and / meaning "horse") is an extinct genus of early horse. It lived 37 to 32 million years ago in the Early Oligocene. Like many fossil horses, ''Mesohippus'' was common in North America. ...

'' than the more forward orbit of ''Palaeotherium''. The nasal opening in ''Plagiolophus'' is positioned higher than that of ''Propalaeotherium'' and varies in form by species, generally becoming less hollow in later species contrary to the evolutionary trends observed in ''Palaeotherium''.

The body of the premaxilla is elongated but low height and hosts all the incisors. The palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the throat. Together with the maxilla, they comprise the hard palate.

Stru ...

stretches up to the lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bones are two small and fragile bones of the facial skeleton; they are roughly the size of the little fingernail and situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. They each have two surfaces and four borders. Several bon ...

. The optic foramen

The ''optic foramen'' is the opening to the optic canal. The canal is located in the sphenoid bone; it is bounded medially by the body of the sphenoid and laterally by the lesser wing of the sphenoid.

The superior surface of the sphenoid bone is ...

, located in the sphenoid bone

The sphenoid bone is an unpaired bone of the neurocranium. It is situated in the middle of the skull towards the front, in front of the basilar part of occipital bone, basilar part of the occipital bone. The sphenoid bone is one of the seven bon ...

, is larger than that of ''Palaeotherium''; it is separated from other foramen like in other palaeotheres and stretches more forwards compared to equines. Those of ''P. annectens'' and ''P. minor'' pierce through the skull and connect with each other as part of a single optic canal path; those of ''P. cartieri'' and species originating from the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

have thick septa

SEPTA, the Southeastern Pennsylvania Transportation Authority, is a regional public transportation authority that operates bus, rapid transit, commuter rail, light rail, and electric trolleybus services for nearly four million people througho ...

, or anatomical walls that separate them and therefore lead to two different optic canals for each foramen. The sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

(midline of skull's top) and nuchal lines

The nuchal lines are four curved lines on the external surface of the occipital bone:

* The upper, often faintly marked, is named the highest nuchal line, but is sometimes referred to as the Mempin line or linea suprema, and it attaches to the ep ...

are both well-developed, the latter displaying stronger sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

in males. The post-orbital constriction

In physical anthropology, post-orbital constriction is the narrowing of the cranium (skull) just behind the eye sockets (the orbits, hence the name) found in most non-human primates and early hominins. This constriction is very noticeable in non-hu ...

occurs behind the postorbital process

The postorbital process is a projection on the frontal bone near the rear upper edge of the eye socket. In many mammals, it reaches down to the zygomatic arch, forming the postorbital bar.

References

See also

* Orbital process

In the human s ...

like in most other palaeotheres but unlike in ''Palaeotherium''.

The postglenoid process, located in the squamous part of the temporal bone, is large in both ''Plagiolophus'' and ''Palaeotherium'' and has parallel front and back walls. The process is where the hollowing of the ear canal

The ear canal (external acoustic meatus, external auditory meatus, EAM) is a pathway running from the outer ear to the middle ear. The adult human ear canal extends from the auricle to the eardrum and is about in length and in diameter.

S ...

's roof is located, taking different shapes in different species. The underside of the ear canal does not take a canalized form except in ''P. huerzeleri''. The petrous part of the temporal bone

The petrous part of the temporal bone is pyramid-shaped and is wedged in at the base of the skull between the sphenoid and occipital bones. Directed medially, forward, and a little upward, it presents a base, an apex, three surfaces, and three ...

largely contacts the basilar part of the occipital bone and is slightly hollowed.

The horizontal ramus of the manible is robust but varies in such based on factors pertaining to species morphology and sexual dimorphism, its underside being mostly convex but also straight at the front area. The vertical ramus is extensive like in ''Palaeotherium'' but is wider at the area of articulation. The condyloid process

The condyloid process or condylar process is the process on the human and other mammalian species' mandibles that ends in a condyle, the mandibular condyle. It is thicker than the coronoid process of the mandible and consists of two portions: the ...

of the mandible, which articulates with the temporal bone

The temporal bone is a paired bone situated at the sides and base of the skull, lateral to the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex.

The temporal bones are overlaid by the sides of the head known as the temples where four of the cranial bone ...

, is narrow, elongated, and sloped. The coronoid process of the mandible is wide like in ''Palaeotherium'' but may sometimes be wider; it is able to support temporalis muscle

In anatomy, the temporalis muscle, also known as the temporal muscle, is one of the muscles of mastication (chewing). It is a broad, fan-shaped convergent muscle on each side of the head that fills the temporal fossa, superior to the zygomatic a ...

s well for chewing.

Dentition

diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

ta and from the incisors by short ones in both the upper and lower dentition. The other teeth are paired closely with each other in both the upper and lower rows. ''Plagiolophus'' is defined by brachyodont dentitions that became progressively hypsodont (high-crowned) to semi-hypsodont evolutionarily, the premolars being semi-molarized and the molars increasing in size from the front end to the back end of the dental row. The dental formula of ''Plagiolophus'' is , totaling at 42 to 44 teeth present. It differs from ''Leptolophus'' is appearing less lophodont and lesser degree of heterodonty in its cheek teeth. ''Plagiolophus'' also differs from ''Paraplagiolophus'' in having cheek teeth that appear narrower and more lophodont. The postcanine diastemata of ''Plagiolophus'' are longer than those of ''Palaeotherium'' but display varying degrees of such based on sex and species. The subgenus ''Plagiolophus'' differs from ''Paloplotherium'' by its longer postcanine diastemata and greater degree of hypsodonty, and the former has proportionally narrow and oblique lingual lophs in its upper cheek teeth compared to that of the latter. The latter also has a stronger degree of heterodonty from its premolars and smaller internal cusps compared to the former.

While not all species of ''Plagiolophus'' are currently known by fossil incisors, the incisors of known species reveal a common trait of chisel-like shapes typical of the equoids. The outermost edges of the incisors are of identical lengths but take different forms from each other. The edges of the incisors are sharp and thin, giving them flat appearances. The frontmost incisors, the first incisors, have elongated labial (or front in relation to the mouth) faces that are equal in size to that of ''Palaeotherium'' but smaller than that of ''Leptolophus''. The lingual (back) face is shorter than the labial face, takes a concave shape, and is surrounded by a cingulum that ascends up to the outermost edge of the incisor. I1 is inclined and appears to project forward. The second and third incisors have less symmetrical crown shapes compared to the first. Both I2 and I2 have somewhat oblique outermost edges. The third incisors appear to be the most differentiated incisor variants and are the smallest ones. The canines have labial surfaces that are convex compared to their lingual counterparts. The widths of the canines vary because of sexual dimorphism. While the upper canines appear to be inclined forward and outwards due to the positions of their roots, the lower canines and their crowns have straighter positions, although the crowns diverge as well.

cementum

Cementum is a specialized calcified substance covering the root of a tooth. The cementum is the part of the periodontium that attaches the teeth to the alveolar bone by anchoring the periodontal ligament.

Structure

The cells of cementum are ...

on the cheek teeth tend to thicken from the front end to the back end of the dental arch, and it tended to grow evolutionarily thicker over time. ''Paloplotherium'' sometimes lacks any coronal cementum. Within the upper molars, each ectoloph lobe has a middle rib developed on them. The paraconule cusp is separated from the protocone cusp, and the metaloph ridge only touches the ectoloph at advanced stages of dental wear. The crescents of the lower molars are separate from each other. Except for those in deciduous molars, the metastylid and metaconid cusps are nearly identical to each other. The internal cingulid

A cingulid is a term used to describe the structure of some mammalian cheek teeth which refers to a ridge that runs around the base of the crown of a lower molar. The equivalent structure on upper molars is called the cingulum. The presence or a ...

s of the lower molars are reduced or gone.

Postcranial skeleton

Monthyon

Monthyon () is a commune in the Seine-et-Marne department of the Île-de-France region in north-central France.

Notable residents

The Belgian painter Eugène Boch lived in the Villa La Grimpette. In 1959, French actor Jean-Claude Brialy acquir ...

surrounding the skeleton whose whereabouts are also unclear. ''P. minor'' is also known from another assembled skeleton that was originally documented by Fraas in the later 19th century, although Stehlin referenced that Fraas paid little attention to studying the limb bones. Remy in 2004 noted that the postcranial bones of palaeotheriids are not as well-studied, meaning that future studies would require studying traits of postcranial fossils of palaeotheres at the genus level.

According to Remy, if the skeletal images as drawn by Cuvier and Blainville are accurate, then the back of ''P. minor'' appears convex, its peak being on par with the last thoracic vertebrae

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebra (anatomy), vertebrae of intermediate size between the ce ...

and its spinous processes of its lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe t ...

facing forward. Its arched back appears to be more similar to modern reconstructions of ''Propalaeotherium'' than to those of ''Palaeotherium''. The cervical vertebrae of both ''Plagiolophus'' and ''Palaeotherium'' are elongated. It tail, composed of caudal vertebrae

Caudal vertebrae are the vertebrae of the tail in many vertebrates. In birds, the last few caudal vertebrae fuse into the pygostyle, and in apes, including humans, the caudal vertebrae are fused into the coccyx.

In many reptiles, some of the caud ...

, has high spinous processes and appears pointed at its end. The tail is short in length and slender in spite of being made up of many vertebrae.

''Plagiolophus'' has several limb bone fossils attributed to it, although it is unclear as to whether the tarsal and metatarsal

The metatarsal bones or metatarsus (: metatarsi) are a group of five long bones in the midfoot, located between the tarsal bones (which form the heel and the ankle) and the phalanges ( toes). Lacking individual names, the metatarsal bones are ...

bones from the Spanish locality of Roc de Santa are attributable to ''P. annectens'' or ''Anchilophus dumasi''. It is tridactyl, or three-toed, in its forelimbs and hindlimbs like most species of the fellow palaeotheriine ''Palaeotherium'' and unlike the earlier pachynolophine ''Propalaeotherium''. The scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

is forward-facing with a slightly narrow neck (its back being wider than its front) and a shortened upper edge. The iliac crest

The crest of the ilium (or iliac crest) is the superior border of the wing of ilium and the superolateral margin of the greater pelvis.

Structure

The iliac crest stretches posteriorly from the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS) to the posterio ...

of the hip bone

The hip bone (os coxae, innominate bone, pelvic bone or coxal bone) is a large flat bone, constricted in the center and expanded above and below. In some vertebrates (including humans before puberty) it is composed of three parts: the Ilium (bone) ...

in ''Plagiolophus'' is concave in shape, contrasting with that of ''Palaeotherium'' which is convex. The foot bones of ''Plagiolophus'' are distinguished from those ''Palaeotherium'' based on its foot bones being more slender and its side toes being lesser-developed (or smaller and thinner) compared to its middle toe, suggesting that the digits are not well-supported anatomically. ''P. minor'' has particularly slender foot bones; the morphologies of the limb bones suggest that it was better-adapted to cursoriality than any species of ''Palaeotherium'' and other palaeothere genera. The cursoriality adaptation in multiple ''Plagiolophus'' spp. along with ''Palaeotherium medium'' is supported by the elongated and gracile metacarpal bones

In human anatomy, the metacarpal bones or metacarpus, also known as the "palm bones", are the appendicular bones that form the intermediate part of the hand between the phalanges (fingers) and the carpal bones ( wrist bones), which articulate ...

which are of equal proportional lengths. ''P. ministri'' has similarly tall and narrow astragali, suggesting that its limb bone morphologies could have been similar to those of ''P. minor''. The astragali of ''P. huerzeleri'' are slightly shorter and wider compared to those of ''P. ministri''. Both species have slender limb bones roughly corresponding to those of ''P. minor''. ''P. fraasi'' differs from the aforementioned ''Plagiolophus'' species by the side metapodial

Metapodials are long bone

The long bones are those that are longer than they are wide. They are one of five types of bones: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid. Long bones, especially the femur and tibia, are subjected to most of the l ...

bones being visible from the foot's front and the neck of the astragalus being visible. The astragali of ''P. javali'' and ''P. annectens'' are both short and stocky. The limb bone morphologies of ''P. annectens'', ''P. fraasi'', and ''P. javali'' point towards short and robust legs that were less adapted towards cursoriality.

Footprints

Palaeotheriids are known from footprint tracks assigned toichnotaxa

An ichnotaxon (plural ichnotaxa) is "a taxon based on the fossilized work of an organism", i.e. the non-human equivalent of an artifact. ''Ichnotaxon'' comes from the Ancient Greek (''íchnos'') meaning "track" and English , itself derived from ...

, among them being the ichnogenus '' Plagiolophustipus'', named in 1989–1990 by R. Santamaria et al. and suggested to have belonged to ''Plagiolophus''. The ichonogenus is dated to the early Oligocene of Spain and may originated from the locality of Montfalco d'Agramunt, which the sole species name ''Plagiolophustipus montfalcoensis'' derives from. As a tridactyl footprint, it is diagnosed as having a middle digit that is much longer and wider than its two somewhat asymmetrical side digits. The ichonospecies measures between and total. The assignment of the ichnogenus to ''Plagiolophus'' is based on its middle digit being longer and wider than the other digits unlike that of ''Palaeotherium'' which has roughly equal sizes in all three of its toes.

By extent, the ichnogenus '' Palaeotheriipus'', assigned to ''Palaeotherium'', differs from ''Plagiolophustipus'' by its smaller and wider digits. '' Lophiopus'', likely produced by ''Lophiodon

''Lophiodon'' (from , 'crest' and 'tooth') is an extinct genus of mammal related to chalicotheres. It lived in Eocene Europe , and was previously thought to be closely related to ''Hyrachyus''. ''Lophiodon'' was named and described by Georges ...

'', has more divergent outer digit imprints, while '' Rhinoceripeda'', attributed to the Rhinocerotidae

A rhinoceros ( ; ; ; : rhinoceros or rhinoceroses), commonly abbreviated to rhino, is a member of any of the five extant taxon, extant species (or numerous extinct species) of odd-toed ungulates (perissodactyls) in the family (biology), famil ...

, differs by its oval shape and varying from three to five digits. ''Palaeotheriipus'' is known from both France and Iran whereas ''Plagiolophustipus'' is currently known from Spain. It is possible that the ichnospecies is correlated with ''P. huerzeleri'' or another medium to large species based on their temporal ranges.

''Plagiolophustipus'' is also known by ''Plagiolophustipus'' ichsp. from the Spanish municipality of Mues in the province of Navarre

Navarre ( ; ; ), officially the Chartered Community of Navarre, is a landlocked foral autonomous community and province in northern Spain, bordering the Basque Autonomous Community, La Rioja, and Aragon in Spain and New Aquitaine in France. ...

, dating to the Oligocene. It is similar to ''Plagiolophustipus montfalcoensis'' because of the presence of three digits, the middle one of which is longer and wider than the other two side digits. The undefined ichnospecies could potentially have belonged a small to medium-sized palaeothere such as ''Plagiolophus''.

Size

''Plagiolophus'' is characterized by the inclusion of small to medium-sized species, the skull base length ranging from to depending on the species. The length of the P2 to M3 dental row ranges from to . According to Remy, the basicranial (lower part of the skull) length of the Ma-PhQ-349 skull specimen of ''P. minor'' could have measured to long. Despite being a high, wide, and robust skull, ''P. minor'' is the smallest species of its genus, with the basal skull length being less than or equal to and the P2 to M3 dental row measuring . ''P. huerzeleri'' is mentioned to have been 20-25% larger than ''P. ministri'' with a basicranial length of and a P2 to M3 dental row length of to . The mandibular dental row of ''P. fraasi'' could measure to long whereas that of ''P. major'' could reach to long. The former species has an estimated skull length of while the latter's skull length could have measured . ''P. javali'' is known only from a male juvenile mandible with a dental row measuring long. With a potential adult skull length of about , ''P. javali'' is the largest species of ''Plagiolophus''.

Remy in 2004 calculated that the smallest species ''P. minor'' could have weighed less than . He also calculated ''P. huerzeleri'' to have a body weight range of to . ''P. major'' has an estimated weight range of to while ''P. fraasi'' has an estimated weight range of to . ''P. javali'', as the largest species of ''Plagiolophus'', could have had a body weight of over . Later in 2015, he placed a body weight estimate of ''P. annectens'' at about , ''P. cartailhaci'' at , and ''P. mamertensis'' at . Jamie A. MacLaren and Sandra Nauwelaerts in 2020 estimated the weight of ''P. minor'' at , ''P. annectens'' at , and ''P. major'' at . In 2022, Leire Perales-Gogenola et al. made five weight estimates of different populations of ''Plagiolophus''. They stated that ''P. mazateronensis'' from Mazaterón has a body weight of . According to the authors, ''P. minor'' from St. Capraise d'Eymet potentially weighed , and ''P. ministri'' from Villebramar weighed . They also said that ''P. annectens'' from Euzet weighed while the same species from Roc de Santa I measured . The same year, Perales-Gogenola et al. estimated that ''P. mazateronensis'' has a weight estimate range of to .

''Plagiolophus'' is characterized by the inclusion of small to medium-sized species, the skull base length ranging from to depending on the species. The length of the P2 to M3 dental row ranges from to . According to Remy, the basicranial (lower part of the skull) length of the Ma-PhQ-349 skull specimen of ''P. minor'' could have measured to long. Despite being a high, wide, and robust skull, ''P. minor'' is the smallest species of its genus, with the basal skull length being less than or equal to and the P2 to M3 dental row measuring . ''P. huerzeleri'' is mentioned to have been 20-25% larger than ''P. ministri'' with a basicranial length of and a P2 to M3 dental row length of to . The mandibular dental row of ''P. fraasi'' could measure to long whereas that of ''P. major'' could reach to long. The former species has an estimated skull length of while the latter's skull length could have measured . ''P. javali'' is known only from a male juvenile mandible with a dental row measuring long. With a potential adult skull length of about , ''P. javali'' is the largest species of ''Plagiolophus''.