Physochlaina on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

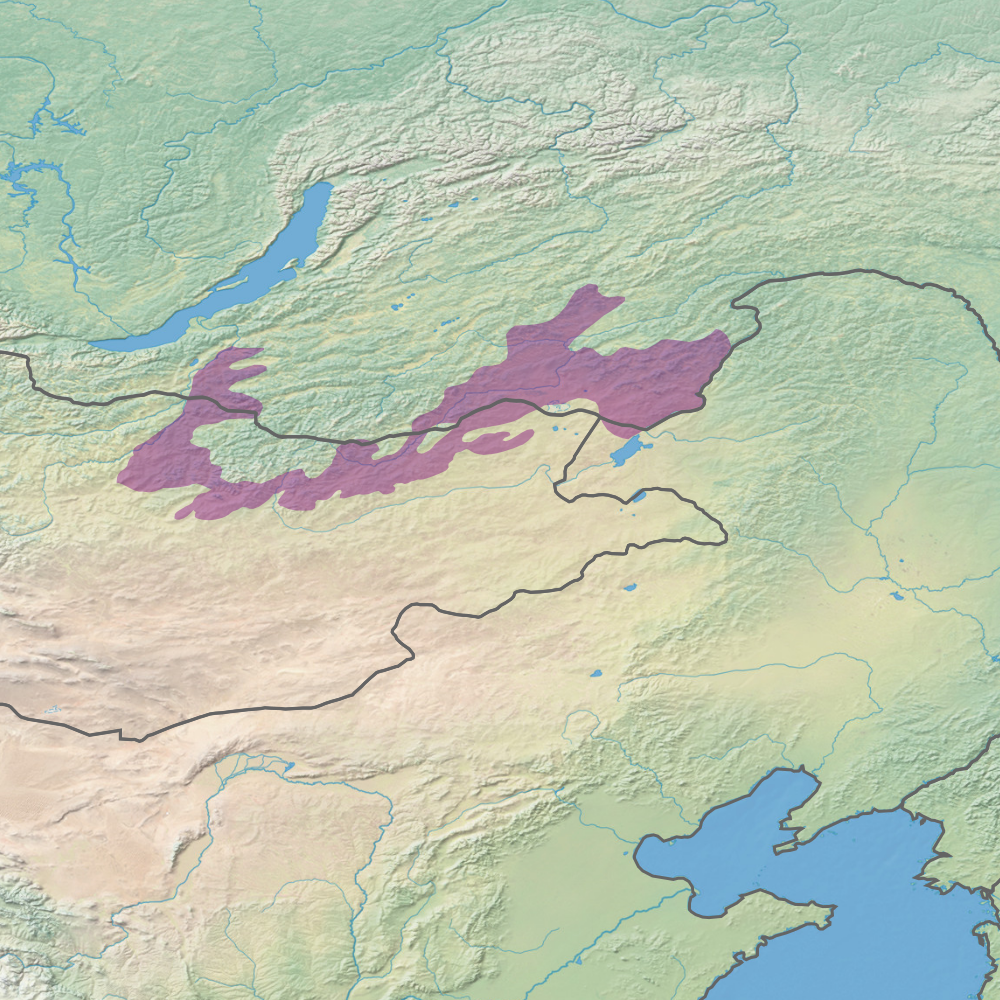

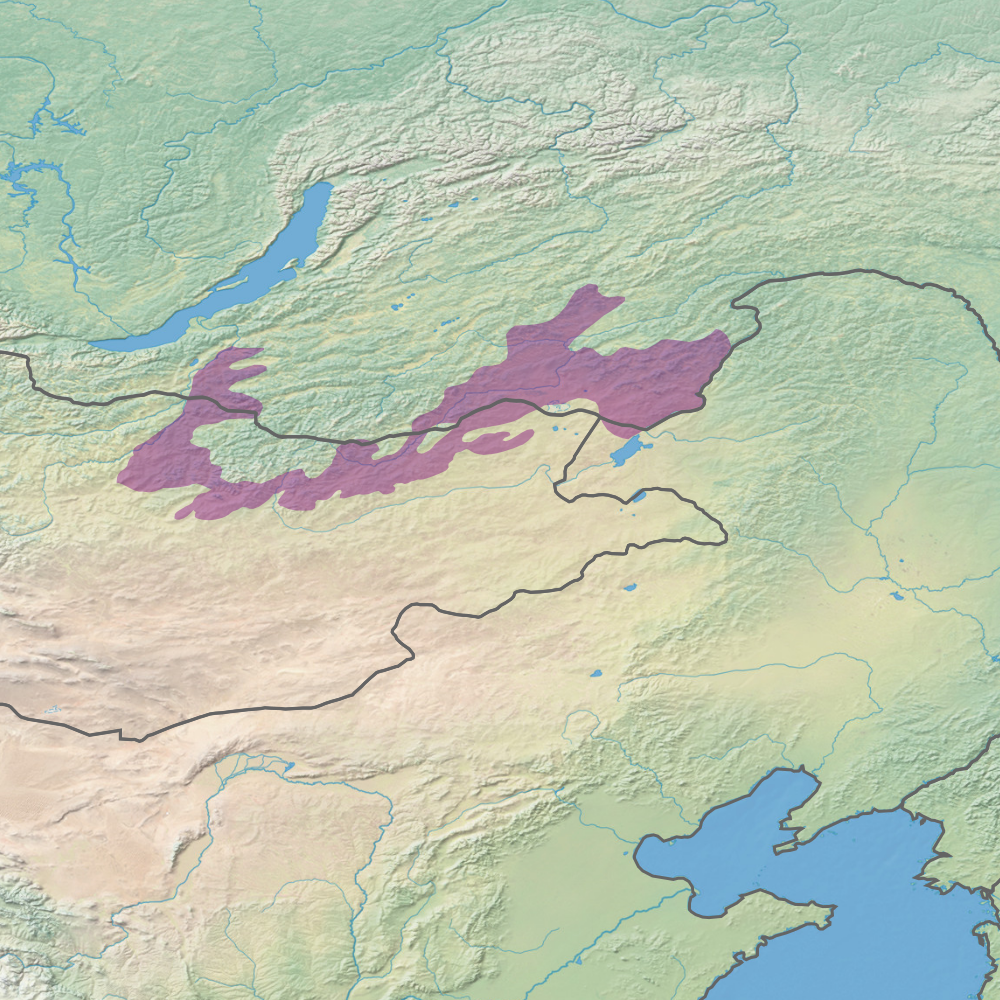

''Physochlaina'' is a small genus of

herbaceous perennial flowering plant

Flowering plants are plants that bear flowers and fruits, and form the clade Angiospermae (). The term angiosperm is derived from the Ancient Greek, Greek words (; 'container, vessel') and (; 'seed'), meaning that the seeds are enclosed with ...

s belonging to the nightshade family,

Solanaceae

Solanaceae (), commonly known as the nightshades, is a family of flowering plants in the order Solanales. It contains approximately 2,700 species, several of which are used as agricultural crops, medicinal plants, and ornamental plants. Many me ...

, found principally in the north-western provinces of

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

(and regions adjoining these in the

Himalaya

The Himalayas, or Himalaya ( ), is a mountain range in Asia, separating the plains of the Indian subcontinent from the Tibetan Plateau. The range has some of the Earth's highest peaks, including the highest, Mount Everest. More than 100 pea ...

and

Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

) although one species occurs in

Western Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

, while others occur in

Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

,

Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

and the Chinese autonomous region of

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

. Some sources maintain that the widespread species ''P. physaloides'' is found also in

Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, but the species is not recorded as being native in one of the few English-language floras of the country. The genus has medicinal value, being rich in

tropane

Tropane is a nitrogenous bicyclic organic compound. It is mainly known for the other alkaloids derived from it, which include atropine and cocaine, among others. Tropane alkaloids occur in plants of the families Erythroxylaceae (including coca) ...

alkaloids, and is also of

ornamental value, three species having been grown for ornament, although hitherto infrequently outside

botanical garden

A botanical garden or botanic gardenThe terms ''botanic'' and ''botanical'' and ''garden'' or ''gardens'' are used more-or-less interchangeably, although the word ''botanic'' is generally reserved for the earlier, more traditional gardens. is ...

s. Furthermore, the genus contains a species (''P. physaloides'' – recorded in older literature under the synonyms ''Hyoscyamus physalodes'', ''Hyoscyamus physaloides'' and ''Scopolia physaloides'') formerly used as an

entheogen

Entheogens are psychoactive substances used in spiritual and religious contexts to induce altered states of consciousness. Hallucinogens such as the psilocybin found in so-called "magic" mushrooms have been used in sacred contexts since ancie ...

in Siberia (re. which see translation of

Gmelin's account of such use below).

Derivation of genus name

The name ''Physochlaina'' is a compound of the

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

words φυσα (''phusa''), 'bladder' / 'bubble' / 'inflated thing' and χλαινα ( ''chlaina'' ), 'robe' / 'loose outer garment' / 'cloak' / 'wrapper' – giving the meaning 'clad loosely in a puffed-up bladder' – in reference to the

calyces of the plants, which become enlarged and sometimes bladder-like in fruit – like those of the much better known Solanaceous genera

Physalis,

Withania and

Nicandra, from which they differ in enclosing, not berries, but box-like pyxidial capsules, like those of Hyoscyamus (see below). The variant spelling ''Physochlaena'' – as employed by Professor

Eva Schönbeck-Temesy in her section on the Solanaceae for ''Flora Iranica'' – appears first on page 737 of Volume 22 of the German-language journal ''Linnaea'' for the year 1849.

Publication of genus name

The genus name ''Physochlaina'' was first published in 1838 by

Scottish botanist

George Don ( great-uncle of

Monty Don

Montagu Denis Wyatt Don (born George Montagu Don; 8 July 1955) is an English horticulturist, broadcaster, and writer who is best known as the lead presenter of the BBC gardening television series '' Gardeners' World''.

Born in Germany and rai ...

) on page 470 of volume IV of his four-volume work ''A General System of Gardening and Botany'', often referred to as ''Gen. Hist.'' (an abbreviation of the alternative title ''A General History of the Dichlamydeous Plants'') and written between 1832 and 1838. He included in his new genus the two species hitherto known as ''Hyoscyamus physaloides'' L. and ''Hyoscyamus orientalis'' M. Bieb. – the latter published by Baron

Friedrich August Marschall von Bieberstein

Baron Friedrich August Marschall von Bieberstein (30 July 1768 – 28 June 1826) was an early explorer of the flora and archeology of the southern portion of Imperial Russia, including the Caucasus and Novorossiya. He compiled the first comprehen ...

in his ''Flora taurico-caucasica'' of 1808.

Common names

Not being native to Western Europe, plants belonging to the genus ''Physochlaina'' have no common name of any antiquity in English, nor have they acquired a more recent common name among English-speaking gardeners, despite the passage of two centuries since their introduction to cultivation in the U.K.

Robert Sweet coined the English name ''Oriental Henbane'' for ''P. orientalis'' in his work ''The British Flower Garden'' in 1823, but this is simply a translation of the ( now obsolete ) name ''Hyoscyamus orientalis''. He further coins the name ''Purple-flowered Henbane'' for the Siberian species ''P. physaloides'', but this adds to the confusion, as, not only is the species in question no longer classified as a Henbane ( i.e. ''Hyoscyamus'' ), but there are also a number of ( true ) ''Hyoscyamus'' spp. which bear purple flowers – e.g.

Hyoscyamus muticus.

There is, however, a common name (age unknown) for ''Physochlaina'' in

Russian, namely Пузырница (''Puzeernitsa'') – '

bladder

The bladder () is a hollow organ in humans and other vertebrates that stores urine from the kidneys. In placental mammals, urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra during urination. In humans, the bladder is a distens ...

/

bubble

Bubble, Bubbles or The Bubble may refer to:

Common uses

* Bubble (physics), a globule of one substance in another, usually gas in a liquid

** Soap bubble

* Economic bubble, a situation where asset prices are much higher than underlying fundame ...

plant', qualified Пузырница Физалисовая (''Puzeernitsa Phizalisovaya'') – ''Physalis-like Bladder plant'' in the case of ''P. physaloides ''. The

Swedish common name for the genus – ''Vårbolmört'' – translates as '

Spring(-flowering)

Henbane

Henbane (''Hyoscyamus niger'', also black henbane and stinking nightshade) is a poisonous plant belonging to tribe Hyoscyameae of the nightshade family ''Solanaceae''. Henbane is native to Temperate climate, temperate Europe and Siberia, and natu ...

', while the

Finnish common name ''Kievarinyrtti'' means '

Inn Herb' and the Estonian common name is ''Ida-vullrohu'', meaning 'Eastern Henbane'.

In

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, where the species ''Physochlaina orientalis'' is native to the region abutting the easternmost stretch of Turkey's

Black Sea

The Black Sea is a marginal sea, marginal Mediterranean sea (oceanography), mediterranean sea lying between Europe and Asia, east of the Balkans, south of the East European Plain, west of the Caucasus, and north of Anatolia. It is bound ...

coast, the common name given to the plant is ''Taş Banotu'', meaning ''Stone Henbane'' i.e. "the henbane that grows on/out of, stone" in reference to the plant's ability to thrive in rock crevices

ee section below on ''P. orientalis'' with accompanying image of wild specimen growing in crevices in volcanic rock The late Professor

Turhan Baytop lists the Turkish common name ''Yalancı Banotu'' (= "False Henbane") for the plant in his 1963 work on the medicinal and poisonous plants of Turkey. He does not, however, record any information concerning any medicinal properties attributed to ''Physochlaina orientalis'' or folk medicinal uses of it made in Turkey. While Baytop includes a brief mention of the plant in the section "List of the Medicinal and Poisonous Plants of Turkey" under the family heading "Solanaceae", he does not include it in the section which constitutes the bulk of his work - namely "Principal Medicinal Plants of Turkey" - this in marked contrast to his substantial treatment of the related genus ''Hyoscyamus''.

The list entry for ''P. orientalis'' reads simply " * Physoclaina

ic.orientalis (M.B.) G.Don. - ''Yalancı Banotu'':

Gümüşhane" - the initial asterisk here indicating a plant not only medicinal but actively poisonous, and "Gümüşhane" the

province of Turkey in which the plant is to be found.

In the ancient,

Iranian

Iranian () may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to Iran

** Iranian diaspora, Iranians living outside Iran

** Iranian architecture, architecture of Iran and parts of the rest of West Asia

** Iranian cuisine, cooking traditions and practic ...

language

Ossetian, spoken both to the North and the South of the Greater Caucasus range, plants of the genus Physochlaina have the common name Тыппыргæрдæг – approximate pronunciation ''Typpyrgərdəg'' ( where

schwa stands for the unique Ossetian vowel for which the special letter 'æ' had to be created in the Cyrillic alphabet ). (See also page ''Physochlaina'' in Wikipedia, language: Ирон).

The name Тыппыргæрдæг is composed of the Ossetian elements тыппыр ( ''typpyr'' ) 'swollen' / 'puffed up' and кæрдаг / гæрдаг ( (approx.) ''kerdag'' / ''gerdag'' ) 'grass' / 'herb' (and also - confusingly - 'fungus' / 'mushroom'), thus yielding an English translation of ''bladder-grass'' ( cf. Ossetian таппуз (''tappuz'') 'bladder' / 'bubble' ). This Ossetian common name for the plant is thus very similar in meaning to the Russian ''Puzeernitsa'', but it is not clear whether it arose independently or is simply a translation of the Russian name for the plant. This said,

Abaev lists a second meaning (prevalent particularly in the

Digor dialect) of the Ossetian word ''typpyr'', namely '

kurgan

A kurgan is a type of tumulus (burial mound) constructed over a grave, often characterized by containing a single human body along with grave vessels, weapons, and horses. Originally in use on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, kurgans spread into mu ...

' (burial mound), in which the primary sense of 'swelling' is applied specifically to a swelling in the landscape i.e. a

tumulus

A tumulus (: tumuli) is a mound of Soil, earth and Rock (geology), stones raised over a grave or graves. Tumuli are also known as barrows, burial mounds, mounds, howes, or in Siberia and Central Asia as ''kurgans'', and may be found through ...

or small artificial hill. It is thus possible that the compound ''Typpyrgerdeg'' is translateable as ''grave-grass'' i.e. a herb associated in some way with grave mounds. Such a meaning for this compound would be compatible with a native Ossetian provenance - not unlikely in regard to the name of a plant native to the Caucasus (see below re. ''P. orientalis'').

There are likewise several common names for the Himalayan ''Physochlaina praealta'' in the various languages of

Nepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

, and common names for the genus ''Physochlaina'' and the various ''Physochlaina'' species of Eastern Asiatic provenance in

Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese ( zh, s=现代标准汉语, t=現代標準漢語, p=Xiàndài biāozhǔn hànyǔ, l=modern standard Han speech) is a modern standard form of Mandarin Chinese that was first codified during the republican era (1912–1949). ...

(泡囊草属 ''pao nang ts'ao shu''),

Tibetan (''khyn khors''),

Kazakh (үрмежеміс = (approximately) ''urmezhemis''),

Uzbek (''xiyoli''),

Uyghur

Uyghur may refer to:

* Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group living in Eastern and Central Asia (West China)

** Uyghur language, a Turkic language spoken primarily by the Uyghurs

*** Old Uyghur language, a different Turkic language spoken in the Uyghur K ...

,

Mongolian (''garag chig tav'') and certain

Tungusic languages

The Tungusic languages (also known as Manchu–Tungus and Tungus) form a language family spoken in Eastern Siberia and Manchuria by Tungusic peoples. Many Tungusic languages are endangered. There are approximately 75,000 native speakers of the ...

.

Accepted species

The Plant List

The Plant List was a list of botanical names of species of plants created by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew and the Missouri Botanical Garden and launched in 2010. It was intended to be a comprehensive record of all known names of plant specie ...

, a joint project of

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew

Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a non-departmental public body in the United Kingdom sponsored by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. An internationally important botanical research and education institution, it employs 1,10 ...

and the

Missouri Botanical Garden

The Missouri Botanical Garden is a botanical garden located at 4344 Shaw Boulevard in St. Louis, Missouri. It is also known informally as Shaw's Garden for founder and philanthropy, philanthropist Henry Shaw (philanthropist), Henry Shaw. I ...

, accepts only six species of the genus:

* ''

Physochlaina capitata''

A.M. Lu (common name in Chinese: 伊犁泡囊草 ''yi li pao nang cao'' i.e. "''Physochlaina'' of the Ili River region") :

Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

:

Ili River valley region, encompassing

Borohoro Mountains and S.W.

Tian Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

:

Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture

Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture is an autonomous prefecture in northern Xinjiang, China. Its capital is Yining, also known as Ghulja or Kulja. Covering an area of 268,591 square kilometres (16.18 per cent of Xinjiang), Ili Prefecture shares ...

(principal settlement

Yining City

YiningThe official spelling according to ( zh, s=伊宁), also known as Ghulja () or Kulja ( Kazakh: ), is a county-level city in northwestern Xinjiang, China. It is the administrative seat and largest city of Ili Kazakh Autonomous Prefectur ...

) :

Xinyuan County (known as Künes pre-1946) and

Gongliu County

Gongliu County ( zh, s=巩留县) as the official romanized name, also SASM/GNC romanization#Uyghur, transliterated from Uyghur as Tokkuztara County (; zh, s=特克斯塔留县), is a county situated within the Xinjiang, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomo ...

, growing on grassy slopes and in rock crevices. Corolla : yellow with purple throat or pale purple veined with deeper purple. Flowering time April to May and fruiting from May to June.

* ''

Physochlaina infundibularis''

Kuang : Southeastern and North-Central China : South and West

Henan

Henan; alternatively Honan is a province in Central China. Henan is home to many heritage sites, including Yinxu, the ruins of the final capital of the Shang dynasty () and the Shaolin Temple. Four of the historical capitals of China, Lu ...

,

Qin Mountains of

Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

and South

Shanxi

Shanxi; Chinese postal romanization, formerly romanised as Shansi is a Provinces of China, province in North China. Its capital and largest city of the province is Taiyuan, while its next most populated prefecture-level cities are Changzhi a ...

, growing in valleys and forests at altitude of 800-1600m. Corolla : greenish-yellow, pale purplish at base or yellowish-purple. Flowering time : March to May and fruiting from May to June. It has also been reported as native to

Primorskiy Krai.

[Фитоаптека (Fitoapteka) http://fitoapteka.org/herbs-p/4103-101032-physochlaina-infundibuaris]

* ''

Physochlaina macrocalyx''

Pascher (common name in Chinese 长萼泡囊草 chang e pao nang cao):

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

. Little-known species. Corolla entirely yellow (no trace of violet). Not yet observed in fruit. Only description available the original brief one by

Adolf Pascher, publisher of species name.

* ''

Physochlaina macrophylla''

Bonati : South-Central China : W.

Sichuan

Sichuan is a province in Southwestern China, occupying the Sichuan Basin and Tibetan Plateau—between the Jinsha River to the west, the Daba Mountains to the north, and the Yunnan–Guizhou Plateau to the south. Its capital city is Cheng ...

, growing in forests at altitude of 1900-2400m. Corolla purple. Flowering time :June to July and fruiting from July to August.

* ''

Physochlaina physaloides''

( L.) G.Don : China :

Hebei

Hebei is a Provinces of China, province in North China. It is China's List of Chinese administrative divisions by population, sixth-most populous province, with a population of over 75 million people. Shijiazhuang is the capital city. It bor ...

,

Heilongjiang

Heilongjiang is a province in northeast China. It is the northernmost and easternmost province of the country and contains China's northernmost point (in Mohe City along the Amur) and easternmost point (at the confluence of the Amur and Us ...

,

Inner Mongolia

Inner Mongolia, officially the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of China. Its border includes two-thirds of the length of China's China–Mongolia border, border with the country of Mongolia. ...

and

Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

. Also Kazakhstan, Mongolia and S. Siberia. Grows on grassy slopes and forest margins at around 1000m. Corolla purple. Flowering from April to May and fruiting from May to July.

* ''

Physochlaina praealta''

( Decne.) Miers :

Western Himalaya

The Western Himalayas are the western half of the Himalayas, in Northwestern India, northwestern India and northern Pakistan. Four of the five tributaries of the Indus River in Punjab (Beas River, Beas, Chenab River, Chenab, Jhelum River, Jhelum ...

, N.

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, N.

Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

,

Nepal

Nepal, officially the Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal, is a landlocked country in South Asia. It is mainly situated in the Himalayas, but also includes parts of the Indo-Gangetic Plain. It borders the Tibet Autonomous Region of China Ch ...

and

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

, growing on slopes at altitude of 4200-4500m. Corolla yellow with purple or greenish veins. Flowering from June to July and fruiting from July to August.

The others being rejected mostly as

synonyms

A synonym is a word, morpheme, or phrase that means precisely or nearly the same as another word, morpheme, or phrase in a given language. For example, in the English language, the words ''begin'', ''start'', ''commence'', and ''initiate'' are a ...

.

Royal Botanic Gardens Kew Science Plants of the World online, however, accepts also:

* ''

Physochlaina alaica''

Korotkova ex Kovalevsk :

Tajikistan

Tajikistan, officially the Republic of Tajikistan, is a landlocked country in Central Asia. Dushanbe is the capital city, capital and most populous city. Tajikistan borders Afghanistan to the Afghanistan–Tajikistan border, south, Uzbekistan to ...

,

Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan, officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked country in Central Asia lying in the Tian Shan and Pamir Mountains, Pamir mountain ranges. Bishkek is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Kyrgyzstan, largest city. Kyrgyz ...

and

Uzbekistan

, image_flag = Flag of Uzbekistan.svg

, image_coat = Emblem of Uzbekistan.svg

, symbol_type = Emblem of Uzbekistan, Emblem

, national_anthem = "State Anthem of Uzbekistan, State Anthem of the Republ ...

.

* ''

Physochlaina albiflora''

Grubov : Mongolia

* ''

Physochlaina orientalis''

( M.Bieb.) G.Don : 'Balkan States' (according to Flora of USSR),

Armenia

Armenia, officially the Republic of Armenia, is a landlocked country in the Armenian Highlands of West Asia. It is a part of the Caucasus region and is bordered by Turkey to the west, Georgia (country), Georgia to the north and Azerbaijan to ...

and E. Turkey,

Transcaucasia

The South Caucasus, also known as Transcaucasia or the Transcaucasus, is a geographical region on the border of Eastern Europe and West Asia, straddling the southern Caucasus Mountains. The South Caucasus roughly corresponds to modern Armenia, ...

, Iran and W. Central Asia

* ''

Physochlaina semenowii''

Regel : Meeting point of

Xinjiang

Xinjiang,; , SASM/GNC romanization, SASM/GNC: Chinese postal romanization, previously romanized as Sinkiang, officially the Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (XUAR), is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People' ...

province of

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

and easternmost

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan, officially the Republic of Kazakhstan, is a landlocked country primarily in Central Asia, with a European Kazakhstan, small portion in Eastern Europe. It borders Russia to the Kazakhstan–Russia border, north and west, China to th ...

i.e.

Dzungaria

Dzungaria (; from the Mongolian words , meaning 'left hand'), also known as Northern Xinjiang or Beijiang, is a geographical subregion in Northwest China that corresponds to the northern half of Xinjiang. Bound by the Altai Mountains to the n ...

– notably the

Tarbagatay Mountains (= '

Tarbagan marmot Mountains'), the

Dzungarian Alatau

The Dzungarian Alatau (, ''Züüngaryn Alatau''; ; , ''Jetısu Alatauy''; , ''Dzhungarskiy Alatau'') is a mountain range that lies on the boundary of the Dzungaria region of China and the Jetisu, Zhetysu region of Kazakhstan. It has a length of ...

('Trans-Ilian Alatau' – Semenova) and the

Tian Shan

The Tian Shan, also known as the Tengri Tagh or Tengir-Too, meaning the "Mountains of God/Heaven", is a large system of mountain ranges in Central Asia. The highest peak is Jengish Chokusu at high and located in Kyrgyzstan. Its lowest point is ...

(including the

Borohoro Mountains). Also Kyrgyzstan. Grows in mountains and mountain river valleys. Corolla small (1 cm) tubular and violet. Flowering from May to June.

Description

Perennial herbs, differing in their type of inflorescence – a terminal,

cymose panicle

In botany, a panicle is a much-branched inflorescence. (softcover ). Some authors distinguish it from a compound spike inflorescence, by requiring that the flowers (and fruit) be pedicellate (having a single stem per flower). The branches of a p ...

or

corymb

Corymb is a botanical term for an inflorescence with the flowers growing in such a fashion that the outermost are borne on longer pedicels than the inner, bringing all flowers up to a common level. A corymb has a flattish top with a superficial re ...

ose

raceme

A raceme () or racemoid is an unbranched, indeterminate growth, indeterminate type of inflorescence bearing flowers having short floral stalks along the shoots that bear the flowers. The oldest flowers grow close to the base and new flowers are ...

– from the other five genera of subtribe Hyoscyaminae within tribe Hyoscyameae of the Solanaceae. Flowers pedunculate (not

secund,

sessile/subsessile as in

Hyoscyamus). Calyx lobes subequal or unequal;

corolla campanulate (bell-shaped) or infundibuliform (funnel-shaped), lobes subequal or sometimes unequal,

imbricate

Aestivation or estivation is the positional arrangement of the parts of a flower within a flower bud before it has opened. Aestivation is also sometimes referred to as praefoliation or prefoliation, but these terms may also mean vernation: the ar ...

in bud; stamens inserted at the middle of corolla tube; disk conspicuous; fruiting calyx lobes nonspinescent apically (i.e. lacking the spiny points characteristic of the calyces of the related genus Hyoscyamus – the Henbanes), fruiting calyx inflated, bladder-like or campanulate, loosely enclosing the capsular fruit. Fruit a pyxidium (i.e. dry capsule opening by a distinct

operculum ( = lid ) – as in the other five genera of the Hyoscyaminae).

Pollen grain polymorphic, usually subspheroidal, oval in polar view, circular-triangular in equatorial view.

Horticultural merit as ornamental

A gifted botanist blessed also with a gardener's eye for beauty, George Don was enthusiastic in his praise for the two plant species for which he created the new genus ''Physochlaina'', noting in his ' ''A General History...'' ' of 1838 :

'The species of ''Physochlaina'' are extremely desirable plants; being early flowerers, and elegant when in blossom. They will grow in any soil, and are readily propagated by divisions of the root, or by seed. They are well adapted for decorating borders in early spring'.

In regard to the soil type favoured by wild populations, volume 22 of ''Linnaea'' (in surprisingly geological vein) provides the observation that ''Physochlaina orientalis'' is to be found growing on soils underlain by

trachyte

Trachyte () is an extrusive igneous rock composed mostly of alkali feldspar. It is usually light-colored and aphanite, aphanitic (fine-grained), with minor amounts of mafic minerals, and is formed by the rapid cooling of lava (or shallow intrus ...

s (

volcanic rock

Volcanic rocks (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) are rocks formed from lava erupted from a volcano. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic rock is artificial, and in nature volcanic rocks grade into hypabyssal and me ...

s of a type notably rich in the chemical element

potassium

Potassium is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol K (from Neo-Latin ) and atomic number19. It is a silvery white metal that is soft enough to easily cut with a knife. Potassium metal reacts rapidly with atmospheric oxygen to ...

, a plant macronutrient essential for the production of flowers and fruit and, in a specifically Solanaceous context, the main ingredient of liquid feed for

tomato

The tomato (, ), ''Solanum lycopersicum'', is a plant whose fruit is an edible Berry (botany), berry that is eaten as a vegetable. The tomato is a member of the nightshade family that includes tobacco, potato, and chili peppers. It originate ...

plants).

Use in traditional Chinese medicine

At least three species of ''Physochlaina'' are currently used in

traditional Chinese medicine

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) is an alternative medicine, alternative medical practice drawn from traditional medicine in China. A large share of its claims are pseudoscientific, with the majority of treatments having no robust evidence ...

: ''P. infundibularis'', ''P. physaloides'' and ''P. praealta''.

''Physochlaina infundibularis''

漏斗泡囊草 ''Lou-dou Pao-nang-ts'ao'' / ''lou dou pao nang cao'' (= 'Funnel-shaped ''Physochlaina'' '). The inhabitants of the neighbouring provinces of

Shaanxi

Shaanxi is a Provinces of China, province in north Northwestern China. It borders the province-level divisions of Inner Mongolia to the north; Shanxi and Henan to the east; Hubei, Chongqing, and Sichuan to the south; and Gansu and Ningxia to t ...

(rendered formerly 'Shensi') and

Henan

Henan; alternatively Honan is a province in Central China. Henan is home to many heritage sites, including Yinxu, the ruins of the final capital of the Shang dynasty () and the Shaolin Temple. Four of the historical capitals of China, Lu ...

hold ''P. infundibularis'' in high esteem as a medicinal plant, regarding it as a kind of

ginseng

Ginseng () is the root of plants in the genus ''Panax'', such as South China ginseng (''Panax notoginseng, P. notoginseng''), Korean ginseng (''Panax ginseng, P. ginseng''), and American ginseng (''American ginseng, P. quinquefol ...

: most unusually for a toxic

Solanaceous plant (totally unrelated botanically to the

Araliaceous ginseng genus

Panax) it is considered to be a 'general tonic' ( =

adaptogen

Adaptogens, or adaptogenic substances, are used in herbal medicine for the purported stabilization of physiological processes and promotion of homeostasis. The concept of adaptogens is not accepted in mainstream science and is not approved as a ...

). The Chinese element 参 ''shen'' (= ''ginseng'') forms a part of two of the common names for the plant, namely 华山参 ''Hua-shan-shen'' (= ''ginseng of

Mount Hua'') and ''Je-shen'' (= ''hot ginseng'' – from its hot, sweet, slightly bitter and astringent taste).

As with Panax, it is the fleshy root of ''Physochlaina infundibularis'' that forms the drug : the fresh, raw roots are first peeled and then boiled in a sugar solution containing small quantities of three other herbal drugs, before being dried, ready for storage and use. The three drugs added to the boiling solution are the root of ''

Glycyrrhiza uralensis'', the

rhizome

In botany and dendrology, a rhizome ( ) is a modified subterranean plant stem that sends out roots and Shoot (botany), shoots from its Node (botany), nodes. Rhizomes are also called creeping rootstalks or just rootstalks. Rhizomes develop from ...

of ''

Ophiopogon japonicus'' and the fruits of ''

Gardenia jasminoides

''Gardenia jasminoides'', commonly known as gardenia and cape jasmine, is an evergreen flowering plant in the coffee family Rubiaceae. It is native to the subtropical and northern tropical parts of the Far East. Wild plants range from 30 centime ...

''. This peeling, boiling and addition of 'cooling',

'yin' drugs is undertaken to mitigate the 'heat' / toxicity of the ''Physochlaina infundibularis'' roots.

In addition to its use as an adaptogen, ''P. infundibularis'' is used (in traditional Chinese medicine) in the treatment of

asthma

Asthma is a common long-term inflammatory disease of the airways of the lungs. It is characterized by variable and recurring symptoms, reversible airflow obstruction, and easily triggered bronchospasms. Symptoms include episodes of wh ...

,

chronic bronchitis

Bronchitis is inflammation of the bronchi (large and medium-sized airways) in the lungs that causes coughing. Bronchitis usually begins as an infection in the nose, ears, throat, or sinuses. The infection then makes its way down to the bronchi. ...

,

abdominal pain

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues. Since the abdomen contains most of the body's vital organs, it can be an indicator of a wide variety of diseases. Given th ...

,

palpitations

Palpitations occur when a person becomes aware of their heartbeat. The heartbeat may feel hard, fast, or uneven in their chest.

Symptoms include a very fast or irregular heartbeat. Palpitations are a sensory symptom. They are often described as ...

and

insomnia

Insomnia, also known as sleeplessness, is a sleep disorder where people have difficulty sleeping. They may have difficulty falling asleep, or staying asleep for as long as desired. Insomnia is typically followed by daytime sleepiness, low ene ...

and as a

sedative

A sedative or tranquilliser is a substance that induces sedation by reducing irritability or Psychomotor agitation, excitement. They are central nervous system (CNS) Depressant, depressants and interact with brain activity, causing its decelera ...

. The drug is also used to treat

diarrhea

Diarrhea (American English), also spelled diarrhoea or diarrhœa (British English), is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements in a day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration d ...

of the kind considered in traditional Chinese medicine to be 'diarrhea due to deficiency of vital energy with symptoms of cold'.

The nomenclatural association of ''P. infundibularis'' with

Mount Hua – 'West Great Mountain' of the

Five Great Mountains of China of

Taoism

Taoism or Daoism (, ) is a diverse philosophical and religious tradition indigenous to China, emphasizing harmony with the Tao ( zh, p=dào, w=tao4). With a range of meaning in Chinese philosophy, translations of Tao include 'way', 'road', ' ...

– is an interesting one and merits further study : in common with other mountains regarded in China as

numinous

Numinous () means "arousing spiritual or religious emotion; mysterious or awe-inspiring";Collins English Dictionary - 7th ed. - 2005 also "supernatural" or "appealing to the aesthetic sensibility." The term was given its present sense by the Ger ...

/

Xian ling, Mount Hua (a precipitous assemblage of five (counted anciently only as three) peaks in the

Qin range) is held to be a source of rare medicinal plants and life-prolonging

elixirs. Furthermore, at the foot of the West Peak of Mount Hua (known as Lianhua Feng (蓮花峰) or Furong Feng (芙蓉峰), both meaning

Lotus Flower

''Nelumbo nucifera'', also known as the pink lotus, sacred lotus, Indian lotus, or simply lotus, is one of two extant taxon, extant species of aquatic plant in the Family (biology), family Nelumbonaceae. It is sometimes colloquially called a ...

Summit) stood, from as early as the second century BCE, a

Taoist temple which was the site of

shamanic

Shamanism is a spiritual practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with the spirit world through Altered state of consciousness, altered states of consciousness, such as trance. The goal of this is usually to direct spiri ...

practices undertaken by

spirit mediums (see also

Wu (shaman)) to contact an (unnamed) God of the

Underworld

The underworld, also known as the netherworld or hell, is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions and myths, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

...

and his minions, believed to dwell in the heart of the mountain.(See also

Chinese folk religion

Chinese folk religion comprises a range of traditional religious practices of Han Chinese, including the Chinese diaspora. This includes the veneration of ''Shen (Chinese folk religion), shen'' ('spirits') and Chinese ancestor worship, ances ...

). Tropane-containing, Solanaceous plants (such as ''

Datura

''Datura'' is a genus of nine species of highly poisonous, Vespertine (biology), vespertine-flowering plants belonging to the nightshade family (Solanaceae). They are commonly known as thornapples or jimsonweeds, but are also known as devil's t ...

'' and ''

Hyoscyamus'' spp.) have a long history of use as entheogens in shamanic practices – including Taoist practices- and indeed ''Physochlaina physaloides'' is known definitely to have been used as an entheogen by certain Tungus tribes ( see section below ), so the possible use of its sister species ''P. infundibularis'' in Taoist, shamanic practices at Mount Hua might prove a topic worthy of consideration.

In addition to its being considered a kind of ginseng in its own right, the root of ''Physochlaina infundibularis'' ('Physochlainae Radix') is sometimes passed off in the ginseng trade as a substitute for the more costly roots of the true ginsengs ''

Panax ginseng

''Panax ginseng'', ginseng, also known as Asian ginseng, Chinese ginseng or Korean ginseng, is a species of plant whose root is the original source of ginseng. It is a perennial plant that grows in the mountains of East Asia. It is mainly cultiv ...

'' and ''

Panax quinquefolius'' – a dangerous practice which could lead to the (potentially fatal),

anticholinergic

Anticholinergics (anticholinergic agents) are substances that block the action of the acetylcholine (ACh) neurotransmitter at synapses in the central nervous system, central and peripheral nervous system.

These agents inhibit the parasympatheti ...

poisoning of unwitting users of these famous tonics, although the substitution tends to be a feature of local, Chinese (rather than international) trade.

ote: as indicated previously, above, ''Physochlaina infundibularis'' is claimed (in a Russian language website) also to be native to what was once the extreme northeast of China (see Outer Manchuria), but is now the

Primorskiy Krai region of the Russian Far East.] The Russian name for the plant is given as Пузырница воронковидная (''Puzeernitsa Voronkovidnaya'') i.e. "funnel-shaped bladder plant" / "the bladder-bearing plant with funnel-shaped flowers", which, like the Chinese ''lou dou pao nang cao'' is simply a translation of the scientific name for the plant.

The plant illustrated in the image on the website page resembles ''Physochlaina physaloides'' but the description provided pertains to ''P. infundibularis''.]

''Physochlaina macrophylla''

大叶泡囊草 ''Da-ye Pao-nang-t'sao'' / ''da ye pao nang cao'' (= "big-leaf ''Physochlaina''" - translating the specific name ''macrophylla'' - Greek for "(having) large leaves" (the disproportionately large leaves dwarf the modest violet flowers)). Like the root of ''Physochlaina infundibularis'', that of ''P. macrophylla'' has also (apparently) occasionally been passed off as that of ''Panax'' in the Chinese ginseng trade : '(The root of) ''Physochlaina macrophylla'' Bonati, a native of

Henan, Honan, China, in appearance is very much like ginseng but slightly red; one should avoid using it as a substitute for ginseng as its alkaloid causes vomiting'.

''Physochlaina physaloides''

泡囊草 ''Pao-nang-ts'ao'' / ''pao nang cao'' (= "(common) ''Physochlaina''") is the

Standard Chinese

Standard Chinese ( zh, s=现代标准汉语, t=現代標準漢語, p=Xiàndài biāozhǔn hànyǔ, l=modern standard Han speech) is a modern standard form of Mandarin Chinese that was first codified during the republican era (1912–1949). ...

name of the widespread species ''P. physaloides'' and the drug derived from it, which is used in the traditional medicine of

Mongolia

Mongolia is a landlocked country in East Asia, bordered by Russia to the north and China to the south and southeast. It covers an area of , with a population of 3.5 million, making it the world's List of countries and dependencies by po ...

, where the plant has the common name ''Yagaan Khyn Khors'' and is also sometimes known by the Tibetan name ''Tampram''. In the traditional systems of medicine in China and Mongolia it is considered to have the effects of 'combatting weakness', 'warming up the

stomach

The stomach is a muscular, hollow organ in the upper gastrointestinal tract of Human, humans and many other animals, including several invertebrates. The Ancient Greek name for the stomach is ''gaster'' which is used as ''gastric'' in medical t ...

', 'soothing the mental condition' and relieving asthma. It is also used for treating 'diarrhea due to deficiency of vital energy with symptoms of cold' and 'cough or asthma caused by excessive

phlegm

Phlegm (; , ''phlégma'', "inflammation", "humour caused by heat") is mucus produced by the respiratory system, excluding that produced by the throat nasal passages. It often refers to respiratory mucus expelled by coughing, otherwise known as ...

or

neurasthenia'.

Note : the medical concept neurasthenia – now largely abandoned in Western medicine – is expressed in Chinese as ''shenjing shuairuo'' (simplified Chinese: 神经衰弱), a compound of ''shenjing'' 'nervous' and ''shuairuo'' 'weakness', and the Chinese condition so described is a

culture-bound syndrome

In medicine and medical anthropology, a culture-bound syndrome, culture-specific syndrome, or folk illness is a combination of psychiatric and somatic symptoms that are considered to be a recognizable disease only within a specific society or c ...

encompassing debility, emotional turmoil, excitement, tension-induced pain and sleep disturbances, caused by a depletion of

qi ('vital energy') and impaired functioning of the

''wuzang'' (= 'five vital organs').

A recent chemical analysis of the plant revealed the presence of the following compounds: in the above-ground parts, the

flavonoid

Flavonoids (or bioflavonoids; from the Latin word ''flavus'', meaning yellow, their color in nature) are a class of polyphenolic secondary metabolites found in plants, and thus commonly consumed in the diets of humans.

Chemically, flavonoids ...

s neoisorutin, glucoepirutin,

rutin

Rutin (rutoside, quercetin-3-O-rutinoside or sophorin) is the glycoside combining the flavonol quercetin and the disaccharide rutinose (α-L-rhamnopyranosyl-(1→6)-β-D-glucopyranose). It is a flavonoid glycoside found in a wide variety of pla ...

,

quercetin

Quercetin is a plant flavonol from the flavonoid group of polyphenols. It is found in many fruits, vegetables, leaves, seeds, and grains; capers, red onions, and kale are common foods containing appreciable amounts of it. It has a bitter flavor ...

-

3-O-β-D-glucofuranosyl-(6→I)-α-L-

rhamnopyranoside-7-α-L-rhamnopyranoside and the alkaloids

hyoscyamine

Hyoscyamine (also known as daturine or duboisine) is a naturally occurring tropane alkaloid and plant toxin. It is a secondary metabolite found in certain plants of the family Solanaceae, including Hyoscyamus niger, henbane, Mandragora officina ...

,

scopolamine and 6-hydroxyatropine; while the underground organs yielded the flavonoids

liquiritigenin, guaiaverine,

coumarin

Coumarin () or 2''H''-chromen-2-one is an aromatic organic chemical compound with formula . Its molecule can be described as a benzene molecule with two adjacent hydrogen atoms replaced by an unsaturated lactone ring , forming a second six-me ...

,

scopolin, fabriatrin,

scopoletin,

umbelliferone, and also

β-sitosterol, 3-O-β-D-

glucopyranoside-β-sitosterol and the alkaloids

atropine

Atropine is a tropane alkaloid and anticholinergic medication used to treat certain types of nerve agent and pesticide poisonings as well as some types of slow heart rate, and to decrease saliva production during surgery. It is typically give ...

, scopolamine and

cuscohygrine.

[''Medicinal Plants in Mongolia'' pub. World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific Region 2013]

retrieved at 13.01 on 2/11/19.

''Physochlaina praealta''

西藏泡囊草 (''H'si-Tsang-pao-nang-ts'ao'' / ''xi zang pao nang cao'' = "Tibetan ''Physochlaina''") is the Standard Chinese name given both to ''Physochlaina praealta'' (Decne) Miers. and the drug prepared from its roots and aerial parts. This has been used in

Tibet

Tibet (; ''Böd''; ), or Greater Tibet, is a region in the western part of East Asia, covering much of the Tibetan Plateau and spanning about . It is the homeland of the Tibetan people. Also resident on the plateau are other ethnic groups s ...

as a substitute for ''Tsang-ch'ieh'' (transliterated also as Zang Qie) –

Anisodus tanguticus, more commonly known in China as ''shān làngdàng'' (= 山莨菪 = 'mountain

henbane

Henbane (''Hyoscyamus niger'', also black henbane and stinking nightshade) is a poisonous plant belonging to tribe Hyoscyameae of the nightshade family ''Solanaceae''. Henbane is native to Temperate climate, temperate Europe and Siberia, and natu ...

'). Unsurprisingly, for a tropane-containing plant, ''P. praealta'' has been recognised in India to have the

belladonna-like property of causing

mydriasis

Mydriasis is the Pupillary dilation, dilation of the pupil, usually having a non-physiological cause, or sometimes a physiological pupillary response. Non-physiological causes of mydriasis include disease, Physical trauma, trauma, or the use of c ...

and is also used there as a

topical medication

A topical medication is a medication that is applied to a particular place on or in the body. Most often topical medication means application to body surface area, body surfaces such as the skin or mucous membranes to treat ailments via a large ...

in the treatment of

boil

A boil, also called a furuncle, is a deep folliculitis, which is an infection of the hair follicle. It is most commonly caused by infection by the bacterium ''Staphylococcus aureus'', resulting in a painful swollen area on the skin caused by ...

s.

[Sharma, B.M. and Singh, Pratap, (1975) Pharmacognostic study of ''Physochlaina praealta'' Miers. ''Quarterly Journal of Crude Drug Research'', 13, pps. 77–84.]

Corroboration of the possession of antiseptic properties by ''Physochlaina praealta'' was provided recently by the publication (in 2019) of a paper entitled (most unhelpfully in this context) ''Isolation of Anemonin from Pulsatilla wallichiana and its Biological Activities''. In a manner not so much as hinted at by its title, this paper discusses not only the effects of aqueous extracts of the eponymous

Pulsatilla species but also of

methanol

Methanol (also called methyl alcohol and wood spirit, amongst other names) is an organic chemical compound and the simplest aliphatic Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol, with the chemical formula (a methyl group linked to a hydroxyl group, often ab ...

extracts of ''Physochlaina praealta'' on various pathogens and medical conditions.

[Iftikhar Ali, Sakeena Khatoon, Faiza Amber, Qamar Abbas, Muhammad Ismail, Nadja Engel, and Viqar Uddin Ahmad ''Isolation of Anemonin from Pulsatilla wallichiana and its Biological Activities'' J. Chem. Soc. Pak., Vol. 41, No. 02, 2019 pps. 325-333.]

In their prefatory remarks, Iftikhar et al. note that, in

Baltistan

Baltistan (); also known as Baltiyul or Little Tibet, is a mountainous region in the Pakistani-administered territory of Gilgit-Baltistan and constitutes a northern portion of the larger Kashmir region that has been the subject of a dispute bet ...

, the plant, known locally as ''Luntung'', is known to be poisonous and to have medicinal properties beneficial to both animals and humans, its leaves being used as antiseptic

bedding material in

cattle

Cattle (''Bos taurus'') are large, domesticated, bovid ungulates widely kept as livestock. They are prominent modern members of the subfamily Bovinae and the most widespread species of the genus '' Bos''. Mature female cattle are calle ...

shed

A shed is typically a simple, single-storey (though some sheds may have two or more stories and or a loft) roofed structure, often used for storage, for hobby, hobbies, or as a workshop, and typically serving as outbuilding, such as in a bac ...

s and its seeds and flowers being used to treat

toothache

Toothaches, also known as dental pain or tooth pain,Segen JC. (2002). ''McGraw-Hill Concise Dictionary of Modern Medicine''. The McGraw-Hill Companies. is pain in the teeth or their supporting structures, caused by dental diseases or referred ...

The methanolic extract of P. praealta was studied for the following biological activities:

antibacterial

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the treatment and prevention ...

,

antifungal

An antifungal medication, also known as an antimycotic medication, is a pharmaceutical fungicide or fungistatic used to treat and prevent mycosis such as athlete's foot, ringworm, candidiasis (thrush), serious systemic infections such as ...

,

anti-inflammatory

Anti-inflammatory is the property of a substance or treatment that reduces inflammation, fever or swelling. Anti-inflammatory drugs, also called anti-inflammatories, make up about half of analgesics. These drugs reduce pain by inhibiting mechan ...

,

anticancer An anticarcinogen (also known as a carcinopreventive agent) is a substance that counteracts the effects of a carcinogen or inhibits the development of cancer. Anticarcinogens are different from anticarcinoma agents (also known as anticancer or ant ...

,

cytotoxic

Cytotoxicity is the quality of being toxic to cells. Examples of toxic agents are toxic metals, toxic chemicals, microbe neurotoxins, radiation particles and even specific neurotransmitters when the system is out of balance. Also some types of dr ...

,

phytotoxic,

brine shrimp

''Artemia'' is a genus of aquatic crustaceans also known as brine shrimp or ''Sea-Monkeys, sea monkeys''. It is the only genus in the Family (biology), family Artemiidae. The first historical record of the existence of ''Artemia'' dates back to t ...

lethality and

insecticidal properties.

The results of the tests for antibacterial activity revealed that the extract exhibited the highest percentage inhibition against ''

Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

'' (68.54%), followed by ''

Escherichia coli

''Escherichia coli'' ( )Wells, J. C. (2000) Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. Harlow ngland Pearson Education Ltd. is a gram-negative, facultative anaerobic, rod-shaped, coliform bacterium of the genus '' Escherichia'' that is commonly fo ...

'' (10.04%), ''

Bacillus subtilis

''Bacillus subtilis'' (), known also as the hay bacillus or grass bacillus, is a gram-positive, catalase-positive bacterium, found in soil and the gastrointestinal tract of ruminants, humans and marine sponges. As a member of the genus ''Bacill ...

'' (06.96%) and ''

Salmonella typhi'' (01.04%) while it remained inactive against ''

Shigella flexneri'' and ''

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common Bacterial capsule, encapsulated, Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-negative, Aerobic organism, aerobic–facultative anaerobe, facultatively anaerobic, Bacillus (shape), rod-shaped bacteria, bacterium that can c ...

''.

In tests for antifungal activity the extract proved inactive against the species ''

Candida albicans'', ''

Trichophyton rubrum

''Trichophyton rubrum'' is a dermatophytic fungus in the phylum Ascomycota. It is an exclusively clonal, anthropophilic saprotroph that colonizes the upper layers of dead skin, and is the most common cause of athlete's foot, fungal infection of ...

'', ''

Aspergillus niger

''Aspergillus niger'' is a mold classified within the ''Nigri'' section of the ''Aspergillus'' genus. The ''Aspergillus'' genus consists of common molds found throughout the environment within soil and water, on vegetation, in fecal matter, on de ...

'', ''

Microsporum canis

''Microsporum canis'' is a pathogenic, asexual fungus in the phylum Ascomycota that infects the upper, dead layers of skin on domesticated cats, and occasionally dogs and humans. The species has a worldwide distribution.

Taxonomy and evolution

...

'' and ''

Fusarium lini''.

In the test for anti-inflammatory activity the extract exhibited 17.6% inhibition at a concentration 25 mg/mL,

Ibuprofen

Ibuprofen is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) that is used to relieve pain, fever, and inflammation. This includes dysmenorrhea, painful menstrual periods, migraines, and rheumatoid arthritis. It can be taken oral administration, ...

being used as a standard drug for comparison and showing 73.2% inhibition at the same concentration.

In the first test for anticancer activity

doxorubicin was used as the standard drug of comparison against

HeLa cell lines, showing 73% inhibition at 30 μg/mL concentration. At the same concentration, the extract exhibited 30% inhibition and was deemed inactive against HeLa cell lines by comparison.

The second test involved testing for anticancer activity on highly

metastatic

Metastasis is a pathogenic agent's spreading from an initial or primary site to a different or secondary site within the host's body; the term is typically used when referring to metastasis by a cancerous tumor. The newly pathological sites, ...

cancer cells - for which the

alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma

Alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma (ARMS) is a subtype of the rhabdomyosarcoma family of soft tissue cancers whose lineage is from mesenchymal cells and are related to skeletal muscle cells. ARMS tumors resemble the alveolar tissue in the lungs. Tum ...

cell line Rh30 was chosen. After treatment with 50 μg/mL, far from a hoped-for decrease in cell viability, the ''P. praealta'' methanolic extract actually slightly increased the cell viability up to 10%.

In the cytotoxicity test, the extract exhibited 22% inhibition, and was considered nontoxic against

3T3 cell lines at the concentration 30 μg/mL, while the standard drug 'cycroamide'

ypo in Iftikhar paper re.cyclophosphamide?">cyclophosphamide.html" ;"title="ypo in Iftikhar paper re.cyclophosphamide">ypo in Iftikhar paper re.cyclophosphamide?used for purposes of comparison, showed a 70% inhibition against 3T3 cell lines when applied at a similar concentration.

In the phytotoxicity test, the Lemnoideae">duckweed

Lemnoideae is a subfamily of flowering aquatic plants, known as duckweeds, water lentils, or water lenses. They float on or just beneath the surface of still or slow-moving bodies of fresh water and wetlands. Also known as bayroot, they arose fr ...

''Lemna minor'' was used as the test species and the herbicide paraquat [mis-spelled 'parquet' in Iftikhar paper] was used for purposes of comparison. The activity was determined at concentrations of 10, 100 and 1000 μg/mL. The ''P. praealta'' extract showed moderate phytotoxic activity at the highest concentrations.

In the

brine shrimp

''Artemia'' is a genus of aquatic crustaceans also known as brine shrimp or ''Sea-Monkeys, sea monkeys''. It is the only genus in the Family (biology), family Artemiidae. The first historical record of the existence of ''Artemia'' dates back to t ...

lethality test, the ''P. praealta'' extract failed to show any significant

activity.

'') they failed to do so in the case of ''Physochlaina praealta''. This is particularly unfortunate in the light of the above-quoted account of the use of the plant as a cattle bedding material in which an insecticidal aspect (e.g. the control of fleas, lice etc.) might be expected in addition to some antiseptic activity (proven in the course of the Iftikhar study - particularly in relation to ''Staphylococcus aureus'')].

Iftikhar notes helpfully the existence of three previous papers devoted to the investigation of the chemistry and biology of ''Physochlaina praealta''

Use in traditional medicine of Tibet and Mongolia

''Physochlaina'' species have a long history of use in the systems of traditional medicine of Tibet and Mongolia as drugs having powerful anti-inflammatory effects against skin diseases and

sexually transmitted diseases

A sexually transmitted infection (STI), also referred to as a sexually transmitted disease (STD) and the older term venereal disease (VD), is an infection that is spread by sexual activity, especially vaginal intercourse, anal sex, oral ...

, in addition to their beneficial effects – both soothing and energizing – upon nervous disorders.

In the traditional system of classification of herbal drugs in Mongolian folk medicine, the plant is described as "bitter in taste with a cool, oily potency". It is used currently as an "antibacterial", an

analgesic

An analgesic drug, also called simply an analgesic, antalgic, pain reliever, or painkiller, is any member of the group of drugs used for pain management. Analgesics are conceptually distinct from anesthetics, which temporarily reduce, and in s ...

, an

anticonvulsant

Anticonvulsants (also known as antiepileptic drugs, antiseizure drugs, or anti-seizure medications (ASM)) are a diverse group of pharmacological agents used in the treatment of epileptic seizures. Anticonvulsants are also used in the treatme ...

, an

antipyretic

An antipyretic (, from ''anti-'' 'against' and ' 'feverish') is a substance that reduces fever. Antipyretics cause the hypothalamus to override a prostaglandin-induced increase in temperature. The body then works to lower the temperature, which r ...

, an anti-parasitic, against

anthrax

Anthrax is an infection caused by the bacterium '' Bacillus anthracis'' or ''Bacillus cereus'' biovar ''anthracis''. Infection typically occurs by contact with the skin, inhalation, or intestinal absorption. Symptom onset occurs between one ...

, against

encephalitis

Encephalitis is inflammation of the Human brain, brain. The severity can be variable with symptoms including reduction or alteration in consciousness, aphasia, headache, fever, confusion, a stiff neck, and vomiting. Complications may include se ...

, against

glanders

Glanders is a contagious, zoonotic infectious disease caused by the bacterium '' Burkholderia mallei'', which primarily occurs in horses, mules, and donkeys, but can also be contracted by dogs and cats, pigs, goats, and humans. The term ''glan ...

, against

parasitic worm

Parasitic worms, also known as helminths, are a polyphyletic group of large macroparasites; adults can generally be seen with the naked eye. Many are intestinal worms that are soil-transmitted and infect the gastrointestinal tract. Other par ...

s of the skin and the

gastrointestinal tract

The gastrointestinal tract (GI tract, digestive tract, alimentary canal) is the tract or passageway of the Digestion, digestive system that leads from the mouth to the anus. The tract is the largest of the body's systems, after the cardiovascula ...

against

tumors

A neoplasm () is a type of abnormal and excessive growth of tissue. The process that occurs to form or produce a neoplasm is called neoplasia. The growth of a neoplasm is uncoordinated with that of the normal surrounding tissue, and persists ...

and to treat

sexual unresponsiveness,

aspermia

Aspermia is the complete lack of semen with ejaculation (not to be confused with azoospermia, the lack of sperm cells in the semen). It is associated with infertility.

One of the causes of aspermia is retrograde ejaculation, because of that the ...

,

abdominal pain

Abdominal pain, also known as a stomach ache, is a symptom associated with both non-serious and serious medical issues. Since the abdomen contains most of the body's vital organs, it can be an indicator of a wide variety of diseases. Given th ...

and

hypothermia

Hypothermia is defined as a body core temperature below in humans. Symptoms depend on the temperature. In mild hypothermia, there is shivering and mental confusion. In moderate hypothermia, shivering stops and confusion increases. In severe ...

. On the negative side, it is said to be "ulcerogenic" i.e. to have the potential to cause

ulcer

An ulcer is a discontinuity or break in a bodily membrane that impedes normal function of the affected organ. According to Robbins's pathology, "ulcer is the breach of the continuity of skin, epithelium or mucous membrane caused by sloughin ...

s of unspecified type

W.H.O. text - the drug may be used

against ulcers, rather than causing them">World Health Organization">W.H.O. text - the drug may be used

against ulcers, rather than causing them

Hallucinogenic use of ''Physochlaina physaloides'' in Central Siberia

Intrepid German naturalist, botanist and geographer

Johann Georg Gmelin records in his ''Reise durch Sibirien'' of 1752 a remarkable account of the intoxicating properties of ''Physochlaina physaloides'', which bears repetition in its entirety.

On 11 August of the year 1738, Gmelin and his fellow explorer

Stepan Krasheninnikov were negotiating the cataracts of the lower reaches of the

Angara river – then known as the Upper Tunguska – in the

Yenisei Basin, when they encountered a waterfall with a curious name:

...we came to Bessanova or Pyanovskaya D. which lies on the left bank of the river, and, two versts down, to another falls – Pyanoy Porog Russian: Пьаной Порог: 'The Drunken Rapids' ..They were christened The Drunken Rapids by the first Yeniseian Cossacks to travel up from Yeniseisk on the stream and pass through them.

They found in the vicinity of these rapids a herb, which they took, from the appearance of its leaves and flowers, to be Lungwort ussian: Медуница: Medunitsaand so used the leaves in the preparation of a vegetable soup and the roots to make a purée

A purée (or mash) is cooked food, usually vegetables, fruits or legumes, that has been ground, pressed, blended or sieved to the consistency of a creamy paste or liquid. Purées of specific foods are often known by specific names, e.g., appl ...

and, partaking of these dishes, grew so utterly intoxicated that they knew not what they were doing. When they had returned to their senses, they named these falls The Drunken Rapids and, because one suffers a headache

A headache, also known as cephalalgia, is the symptom of pain in the face, head, or neck. It can occur as a migraine, tension-type headache, or cluster headache. There is an increased risk of Depression (mood), depression in those with severe ...

after such a debauch, they named the falls that they encountered next Pokhmelnoy Porog Hungover Rapids ">Hangover">Hungover Rapids

His curiosity aroused, Gmelin investigated, and discovered an attractive new species:

This account has given me the opportunity to reveal the identity of the beautiful plant involved, which was unknown to any botanist before me: '' Hyoscyamus foliis integerrimis calicibus inflatis subglobosis '' [Botanical Latin: 'The Henbane having simple, untoothed leaves and (fruiting ) calyces that are more or less round and inflated' [ i.e. like those of a Physalis Linn. h. Ups. 44. 2.

Having identified the ( Linnaean ) genus Hyoscyamus to which the intoxicating plant of The Drunken Rapids ( since moved by Don to the genus Physochlaina ) belonged, Gmelin went on to quiz his local guides and learned the following concerning its intentional consumption:

If one steeps the leaves or even the finely-chopped roots of this plant in brewed beer – or, better yet, in beer that is still undergoing fermentation

Fermentation is a type of anaerobic metabolism which harnesses the redox potential of the reactants to make adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and organic end products. Organic molecules, such as glucose or other sugars, are catabolized and reduce ...

– then it takes but a single glass of such beer to make a man exceedingly foolish: it is surely a strange draught that he quaffs, for he is robbed of all his senses, or at least finds his senses grossly disordered, mistaking tiny things for huge ones: a straw for the thickest of beams, a drop of water for a mighty ocean and a mouse for an elephant. Wherever he goes he encounters what he imagines to be insurmountable obstacles. He pictures continually to himself the cruellest and most dreadful imaginings of an inevitable death awaiting him, and, as it seems, all this fills him with despair, because his senses are withering away; thus, should one such drunkard go to step over a beam, he will take a great stride out of all proportion to the actual size of it, while another will see deep water in front of him where there is only shallow such that he dare not venture into it.

In conclusion, Gmelin then adds, concerning the plant itself:

The local inhabitants often use these roots when they want to play a prank upon each other. The Russian merchants often bring these roots back with them when they return to Russia, because they maintain them to be a sovereign remedy for bleeding haemorrhoids and also against the haematuria

Hematuria or haematuria is defined as the presence of blood or red blood cells in the urine. "Gross hematuria" occurs when urine appears red, brown, or tea-colored due to the presence of blood. Hematuria may also be subtle and only detectable with ...

– a claim which I have been unable to verify.

Gmelin's ''Reise durch Sibirien'' – with its evocative account of his findings concerning the plant now known to science as ''Physochlaina physaloides'' – received a translation into French which was published as part of Volume 18 of

Abbé Prévost's monumental ''Histoire générale des voyages'' – a compendium of eighteenth century exploration by land and sea, continued beyond the original fifteen volumes, by other authors following the death of Prévost in 1763. The ''Histoire'' translation is by no means always a word-for-word rendering of Gmelin's original text, and, in the passage concerning Physochlaina, a sentence entirely absent from the Gmelin account has been added, which nonetheless has been retained in subsequent retellings of the passage in question:

Il parle continuellement sans savoir ce qu'il dit. ranslation: 'He speaks continually, without knowing what he is saying' – said of the man intoxicated by a single glass of potent Physochlaina beer

The first work devoted exclusively to recreational drugs to draw on Prévost's translation of Gmelin's account of Evenki Physochlaina use was ''A History of Tobacco with notes on the use of all Excitants currently known'' by Italian botanist Professor

Orazio Comes, written in French and published in Naples in 1900.

Comes's summary of the Prévost translation was included by German Botanist

Carl Hartwich in his classic and influential work of 1911 ''Die Menschlichen Genussmittel'' (= 'The Pleasure-drugs of Mankind'),

[Carl Hartwich ''Die Menschlichen Genussmittel, ihre herkunft, verbreitung, geschichte, anwendung, bestandteile und wirkung'' ( Translation: ''The Pleasure-drugs of Mankind – their origins, spread, history, application, ingredients and effects'' ), pub. Leipzig 1911 Chr. Herm. Tauchnitz. Page 522 under heading 3: 'Daß Hyoscyamus'.] which, in turn, was quoted by 21st century expert on hallucinogens Dr. Christian Rätsch in his ''Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants'' of 2005. Hartwich speaks only of 'Hyoscyamus' with no indication of the species involved and, while Rätsch uses the correct species name ''physaloides'' he still includes the plant in his discussion of the various Hyoscyamus species – seemingly unaware that the plant was actually made the

type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of the new genus Physochlaina by George Don as far back as the year 1838.

Physochlaina and Amanita: similarities in descriptions of macropsia in accounts of two Siberian hallucinogens

There exist curious similarities between Gmelin's account of the effects of Physochlaina beer – as detailed above – and his student and fellow traveller Krasheninnikov's account of the effects of a very different, and better-known, Siberian hallucinogen, namely ''

Amanita muscaria

''Amanita muscaria'', commonly known as the fly agaric or fly amanita, is a basidiomycete fungus of the genus ''Amanita''. It is a large white-lamella (mycology), gilled, white-spotted mushroom typically featuring a bright red cap covered with ...

'', the fly agaric. Gmelin and Krasheninnikov's accounts of the effects of intoxication by the plant and mushroom in question both derive from their participation in the extraordinary

Great Northern Expedition (known also as the Second

Kamchatka

The Kamchatka Peninsula (, ) is a peninsula in the Russian Far East, with an area of about . The Pacific Ocean and the Sea of Okhotsk make up the peninsula's eastern and western coastlines, respectively.

Immediately offshore along the Pacific ...

Expedition). As described above, they were travelling together in Central Siberia in the summer of 1738 on the occasion of Gmelin's discovery of ''Physochlaina physaloides'' and learning from the Evenk of the curious effects produced by the beer which they prepared from it. Gmelin was, at the time, one of three professors heading the Academic Group of the expedition, and his particular area of expertise within that group concerned the animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms, his brief being to document the fauna, flora and mineral wealth of Siberia encountered in their travels. After many adventures, including the encounter with ''Physochlaina physaloides'' on the Angara river near

Yeniseysk, Professors Gmelin and

Müller

Müller may refer to:

Companies

* Müller (company), a German multinational dairy company

** Müller Milk & Ingredients, a UK subsidiary of the German company

* Müller (store), a German retail chain

* GMD Müller, a Swiss aerial lift manufacturi ...

, student Krasheninnikov and many other expedition members gathered at

Vitus Bering

Vitus Jonassen Bering ( , , ; baptised 5 August 1681 – 19 December 1741),All dates are here given in the Julian calendar, which was in use throughout Russia at the time. also known as Ivan Ivanovich Bering (), was a Danish-born Russia ...

's base at

Yakutsk

Yakutsk ( ) is the capital and largest city of Sakha, Russia, located about south of the Arctic Circle. Fueled by the mining industry, Yakutsk has become one of Russia's most rapidly growing regional cities, with a population of 355,443 at the ...

. It was from here that Gmelin sent Krasheninnikov ahead to

Okhotsk and Kamchatka to reconnoitre, make preliminary observations and prepare accommodation, and it was thus that he came to be the member of the expedition with the most extensive knowledge of the Kamchatka peninsula, publishing his observations in 1755 in the work ''Описание земли Камчатки'' (''Description of the Land of Kamchatka'') – from Chapter 14 of which the following passage is translated:

...persons thus intoxicated y ''Amanita muscaria''have hallucinations, as if in a fever; they are subject to various visions, terrifying or felicitous, depending on differences in temperament, owing to which some jump, some dance, others cry and suffer great terrors, while some might deem a small crack to be as wide as a door, and a tub of water as deep as the sea.

To the above may readily be compared Gmelin's ''mistaking a drop of water for a mighty ocean'' and ''He pictures continually to himself the cruellest and most dreadful imaginings of an inevitable death awaiting him''.

The phenomenon, described in similar terms by Gmelin and Krasheninnikov in their respective accounts, is that of

macropsia

Macropsia is a neurological condition affecting human visual perception, in which objects within an affected section of the visual field appear larger than normal, causing the person to feel smaller than they actually are. Macropsia, along with its ...

- whereby small objects are perceived as being enormous - a symptom of (among other conditions, both natural and self-inflicted) the use of psychoactive drugs (see also

dysmetropsia

Alice in Wonderland Syndrome (AIWS), also known as Todd's Syndrome or Dysmetropsia, is a neurological disorder that distorts perception. People with this syndrome may experience distortions in their visual perception of objects, such as appear ...

).

It is not clear, in this context, whether the similarity between the two accounts is due simply to the fungal and the plant drug eliciting similar symptoms or whether there has been a borrowing of phraseology from one author to another (in which direction it is hard to say). The inference would likely be that any borrowing were from the Physochlaina account to the Amanita account, were it not for the fact that accounts of macropsia caused by tropane-containing Solanaceae are rare, while those of macropsia caused by ''Amanita muscaria'' are common (or perhaps merely oft-repeated, from a few early sources).

To this question one may further adduce the account of ''Amanita muscaria''-induced macropsia in another early source, namely that of

Georg Heinrich von Langsdorff, which seems as close in tone to Gmelin's account as does that of Krasheninnikov:

The nerves are highly stimulated, and in this state the slightest effort of will produces very powerful effects. Consequently, if one wishes to step over a small stick or straw, he steps and jumps as though the obstacles were tree trunks. If a man is ordinarily talkative...he involuntarily blurts out secrets, fully conscious of his actions and aware of his secret but unable to hold his nerves in check. The muscles are controlled by an uncoordinated activity of the nerves themselves, uninfluenced by and unconnected with the higher willpower of the brain, and thus it has occasionally happened that persons in this stage of intoxication found themselves driven irresistibly into ditches, streams, ponds and the like, seeing the impending danger before their eyes but unable to avoid certain death except by the assistance of friends who rushed to their aid.