Maximilien Robespierre on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre (; ; 6 May 1758 – 28 July 1794) was a French lawyer and statesman, widely recognised as one of the most influential and controversial figures of the French Revolution. Robespierre fervently campaigned for the voting rights of all men and their unimpeded admission to the National Guard. Additionally, he advocated the right to petition, the right to bear arms in self-defence, and the abolition of the

During his three-year study of law at the Sorbonne, Robespierre distinguished himself academically, culminating in his graduation in July 1780, where he received a special prize of 600 for his exceptional academic achievements and exemplary conduct. Admitted to the bar, he was appointed as one of the five judges in the local criminal court in March 1782. However, Robespierre soon resigned, due to his ethical discomfort in adjudicating capital cases, stemming from his opposition to the death penalty.

Robespierre was elected to the literary Academy of Arras in November 1783. The following year, the Academy of Metz honoured him with a medal for his essay pondering collective punishment, thus establishing him as a literary figure. ( Pierre Louis de Lacretelle and Robespierre shared the prize.)

In 1786 Robespierre passionately addressed inequality before the law, criticising the indignities faced by illegitimate or natural children, and later denouncing practices like ''lettres de cachet'' (imprisonment without a trial) and the marginalisation of women in academic circles. Robespierre's social circle expanded to include influential figures such as the lawyer Martial Herman, the officer and engineer Lazare Carnot and the teacher Joseph Fouché, all of whom would hold significance in his later endeavours. His role as the secretary of the Academy of Arras connected him with François-Noël Babeuf, a revolutionary land surveyor in the region.

In August 1788, King Louis XVI summoned the Estates-General to convene on 1 May 1789. Robespierre advocated in his ''Address to the Nation of Artois'' that following the customary mode of election by the members of the provincial estates would fail to adequately represent the people of France in the new Estates-General. In his electoral district, Arras, Robespierre began to assert his influence in politics through his ''Notice to the Residents of the Countryside'' in 1789, targeting local authorities and garnering the support of rural electors. On 26 April 1789, Robespierre secured his place as one of 16 deputies representing French Flanders in the Estates-General.

During his three-year study of law at the Sorbonne, Robespierre distinguished himself academically, culminating in his graduation in July 1780, where he received a special prize of 600 for his exceptional academic achievements and exemplary conduct. Admitted to the bar, he was appointed as one of the five judges in the local criminal court in March 1782. However, Robespierre soon resigned, due to his ethical discomfort in adjudicating capital cases, stemming from his opposition to the death penalty.

Robespierre was elected to the literary Academy of Arras in November 1783. The following year, the Academy of Metz honoured him with a medal for his essay pondering collective punishment, thus establishing him as a literary figure. ( Pierre Louis de Lacretelle and Robespierre shared the prize.)

In 1786 Robespierre passionately addressed inequality before the law, criticising the indignities faced by illegitimate or natural children, and later denouncing practices like ''lettres de cachet'' (imprisonment without a trial) and the marginalisation of women in academic circles. Robespierre's social circle expanded to include influential figures such as the lawyer Martial Herman, the officer and engineer Lazare Carnot and the teacher Joseph Fouché, all of whom would hold significance in his later endeavours. His role as the secretary of the Academy of Arras connected him with François-Noël Babeuf, a revolutionary land surveyor in the region.

In August 1788, King Louis XVI summoned the Estates-General to convene on 1 May 1789. Robespierre advocated in his ''Address to the Nation of Artois'' that following the customary mode of election by the members of the provincial estates would fail to adequately represent the people of France in the new Estates-General. In his electoral district, Arras, Robespierre began to assert his influence in politics through his ''Notice to the Residents of the Countryside'' in 1789, targeting local authorities and garnering the support of rural electors. On 26 April 1789, Robespierre secured his place as one of 16 deputies representing French Flanders in the Estates-General.

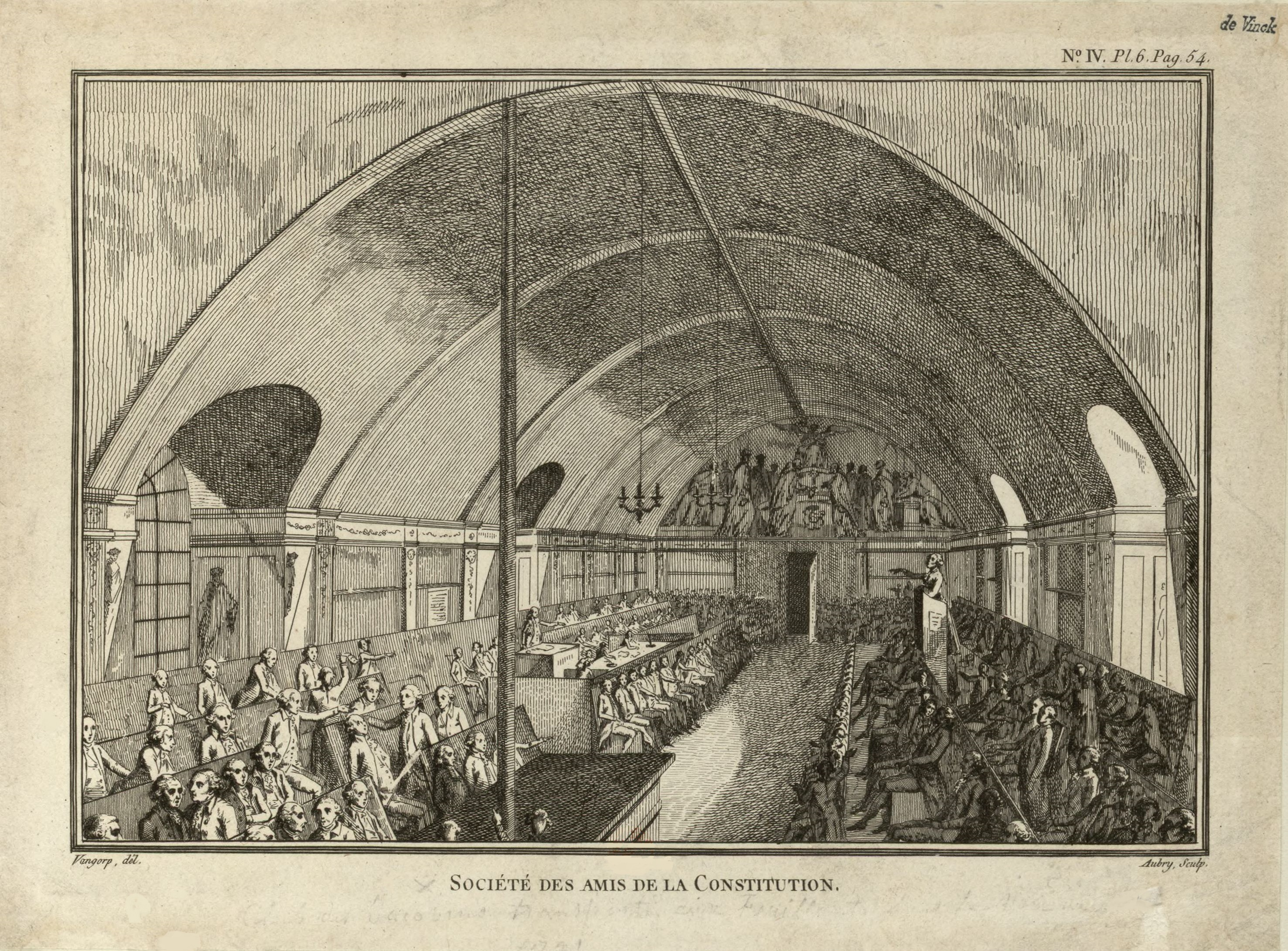

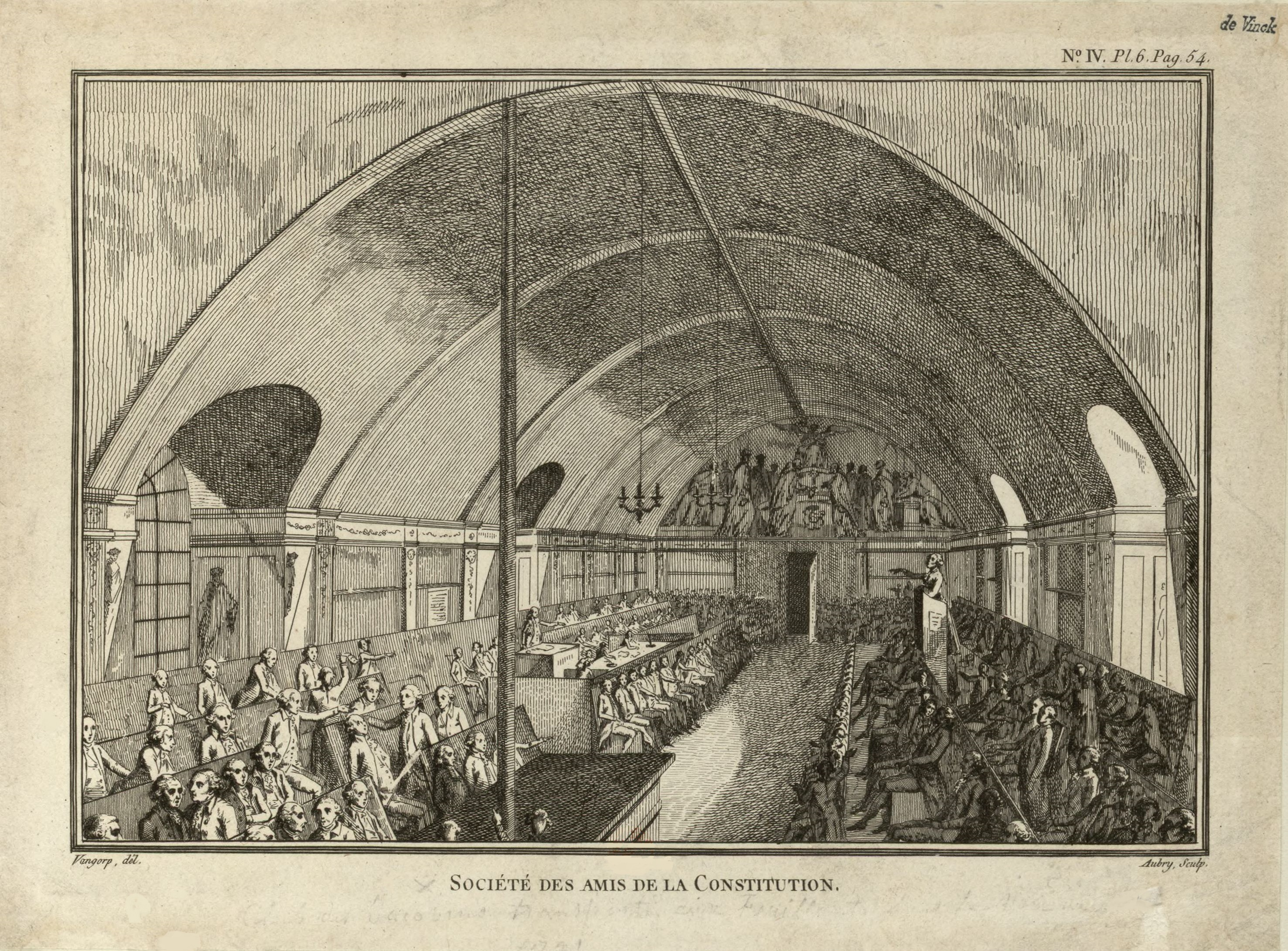

Following the forcible relocation of the King and National Constituent Assembly from Versailles to Paris, Robespierre lived at 30 Rue de Saintonge in Le Marais, a district with relatively wealthy inhabitants. He shared an apartment on the third floor with Pierre Villiers who was his secretary for several months. Robespierre associated with the new Society of the Friends of the Constitution, commonly known as the Jacobin Club. Among these 1,200 men, Robespierre found a sympathetic audience. Equality before the law was the keystone of the Jacobin ideology. Beginning in October and continuing through January he made several speeches in response to proposals for property qualifications for voting and officeholding under the proposed constitution. This was a position he vigorously opposed, arguing in a speech on 22 October the position that he derived from Rousseau:

Following the forcible relocation of the King and National Constituent Assembly from Versailles to Paris, Robespierre lived at 30 Rue de Saintonge in Le Marais, a district with relatively wealthy inhabitants. He shared an apartment on the third floor with Pierre Villiers who was his secretary for several months. Robespierre associated with the new Society of the Friends of the Constitution, commonly known as the Jacobin Club. Among these 1,200 men, Robespierre found a sympathetic audience. Equality before the law was the keystone of the Jacobin ideology. Beginning in October and continuing through January he made several speeches in response to proposals for property qualifications for voting and officeholding under the proposed constitution. This was a position he vigorously opposed, arguing in a speech on 22 October the position that he derived from Rousseau:

The Declaration of Pillnitz issued by Austria and Prussia on 27 August 1791 warned the people of France not to harm Louis XVI or these nations would "militarily intervene". Brissot rallied the support of the Legislative Assembly for war with Austria. As Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Danton and Robespierre had not been elected in the new legislature, thanks to the Self-Denying Ordinance, anti-war politics mainly took place outside the Assembly. On 18 December 1791, Robespierre gave a second speech at the Jacobin club against war, warning against the threat of dictatorship stemming from it:

At the end of December, Guadet, the chairman of the Assembly, suggested that a war would be a benefit to the nation and boost the economy. Marat and Robespierre opposed him, arguing that victory would create a dictatorship, while defeat would restore the king to his former powers.

This opposition from expected allies irritated the Girondins, and the war became a major point of contention between the factions. In his third speech on the war, Robespierre countered on 25 January 1792 in the Jacobin club, "A revolutionary war must be waged to free subjects and slaves from unjust tyranny, not for the traditional reasons of defending dynasties and expanding frontiers..." Robespierre argued such a war could only favour the forces of counter-revolution, since it would play into the hands of those who opposed the sovereignty of the people. The risks of Caesarism were clear: "in troubled periods of history, generals often became the arbiters of the fate of their countries." Robespierre failed to gather a majority, but his speech was nevertheless published and sent to all clubs and Jacobin societies of France.

On 10 February 1792, Robespierre gave a speech on how to save the State and Liberty. He advocated specific measures to strengthen, not so much the national defences as the forces that could be relied on to defend the revolution. Robespierre promoted a people's army, continuously under arms and able to impose its will on Feuillants and Girondins in the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI and the Legislative Assembly. The Jacobins decided to study his speech before deciding whether it should be printed.

On 26 March, Guadet accused Robespierre of superstition, relying on divine providence. Shortly after Robespierre was accused by Brissot and Guadet of "trying to become the idol of the people". Being against the war, Robespierre was also accused of acting as a secret agent for the " Austrian Committee". The Girondins planned strategies to out-maneuver Robespierre's influence among the Jacobins. On 27 April, as part of his speech responding to the accusations by Brissot and Guadet against him, he threatened to leave the Jacobins, claiming he preferred to continue his mission as an ordinary citizen.

On 17 May, Robespierre released the first issue of his weekly periodical (''The Defender of the Constitution''). In this publication, he criticised Brissot and expressed his scepticism over the war movement. The periodical, printed by his neighbour Nicolas, served multiple purposes: to print his speeches, to counter the influence of the royal court in public policy, to defend him from the accusations of Girondist leaders; and to give voice to the economic and democratic interests of the broader masses in Paris and defend their rights.

The Declaration of Pillnitz issued by Austria and Prussia on 27 August 1791 warned the people of France not to harm Louis XVI or these nations would "militarily intervene". Brissot rallied the support of the Legislative Assembly for war with Austria. As Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Danton and Robespierre had not been elected in the new legislature, thanks to the Self-Denying Ordinance, anti-war politics mainly took place outside the Assembly. On 18 December 1791, Robespierre gave a second speech at the Jacobin club against war, warning against the threat of dictatorship stemming from it:

At the end of December, Guadet, the chairman of the Assembly, suggested that a war would be a benefit to the nation and boost the economy. Marat and Robespierre opposed him, arguing that victory would create a dictatorship, while defeat would restore the king to his former powers.

This opposition from expected allies irritated the Girondins, and the war became a major point of contention between the factions. In his third speech on the war, Robespierre countered on 25 January 1792 in the Jacobin club, "A revolutionary war must be waged to free subjects and slaves from unjust tyranny, not for the traditional reasons of defending dynasties and expanding frontiers..." Robespierre argued such a war could only favour the forces of counter-revolution, since it would play into the hands of those who opposed the sovereignty of the people. The risks of Caesarism were clear: "in troubled periods of history, generals often became the arbiters of the fate of their countries." Robespierre failed to gather a majority, but his speech was nevertheless published and sent to all clubs and Jacobin societies of France.

On 10 February 1792, Robespierre gave a speech on how to save the State and Liberty. He advocated specific measures to strengthen, not so much the national defences as the forces that could be relied on to defend the revolution. Robespierre promoted a people's army, continuously under arms and able to impose its will on Feuillants and Girondins in the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI and the Legislative Assembly. The Jacobins decided to study his speech before deciding whether it should be printed.

On 26 March, Guadet accused Robespierre of superstition, relying on divine providence. Shortly after Robespierre was accused by Brissot and Guadet of "trying to become the idol of the people". Being against the war, Robespierre was also accused of acting as a secret agent for the " Austrian Committee". The Girondins planned strategies to out-maneuver Robespierre's influence among the Jacobins. On 27 April, as part of his speech responding to the accusations by Brissot and Guadet against him, he threatened to leave the Jacobins, claiming he preferred to continue his mission as an ordinary citizen.

On 17 May, Robespierre released the first issue of his weekly periodical (''The Defender of the Constitution''). In this publication, he criticised Brissot and expressed his scepticism over the war movement. The periodical, printed by his neighbour Nicolas, served multiple purposes: to print his speeches, to counter the influence of the royal court in public policy, to defend him from the accusations of Girondist leaders; and to give voice to the economic and democratic interests of the broader masses in Paris and defend their rights.

On 2 September, the 1792 French National Convention election began. Meanwhile Paris was organising its defence against the Prussians, but there was a lack of arms for the thousands of volunteers. Danton delivered a speech in which he said: "We ask that anyone who refuses to serve in person, or surrender their weapons, is punished with death." His speech acted as a call for direct action among the citizens, as well as a strike against the external enemy. Not long after, the September Massacres began. Robespierre and Manuel, the public prosecutor, responsible for the police administration, visited the Temple prison to check on the safety of the royal family.

In Paris, suspected Girondin and royalist candidates were excluded both before and after the vote due to "Robespierre's unabashed vote rigging"; Robespierre contributed to the failure of Brissot and his associates Pétion and Condorcet to be elected in Paris. On 5 September, Robespierre was elected deputy to the National Convention but Danton and Collot d'Herbois received more votes than Robespierre. Madame Roland wrote to a friend: "We are under the knife of Robespierre and Marat, those who would agitate the people." The election was not the triumph for the Jacobins that they had anticipated, but during the next nine months they gradually eliminated their opponents and gained control of the Convention.

On 2 September, the 1792 French National Convention election began. Meanwhile Paris was organising its defence against the Prussians, but there was a lack of arms for the thousands of volunteers. Danton delivered a speech in which he said: "We ask that anyone who refuses to serve in person, or surrender their weapons, is punished with death." His speech acted as a call for direct action among the citizens, as well as a strike against the external enemy. Not long after, the September Massacres began. Robespierre and Manuel, the public prosecutor, responsible for the police administration, visited the Temple prison to check on the safety of the royal family.

In Paris, suspected Girondin and royalist candidates were excluded both before and after the vote due to "Robespierre's unabashed vote rigging"; Robespierre contributed to the failure of Brissot and his associates Pétion and Condorcet to be elected in Paris. On 5 September, Robespierre was elected deputy to the National Convention but Danton and Collot d'Herbois received more votes than Robespierre. Madame Roland wrote to a friend: "We are under the knife of Robespierre and Marat, those who would agitate the people." The election was not the triumph for the Jacobins that they had anticipated, but during the next nine months they gradually eliminated their opponents and gained control of the Convention.

File:La chute des Girondins.jpg, , an engraving of the Convention surrounded by National Guards.

File:The elimination of Girondins.jpg, The uprising of the Parisian sans-culottes from 31 May to 2 June 1793. The scene takes place in front of the Deputies Chamber in the Tuileries. The depiction shows Marie-Jean Hérault de Séchelles and Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud.

File:Général François Hanriot.jpg, François Hanriot ( Rue Mouffetard); drawing by Gabriel in the Carnavalet Museum

On 12 December, Robespierre attacked the wealthy foreigner Cloots in the Jacobin club of being a Prussian spy. Robespierre denounced the "de-Christianisers" as foreign enemies. The Indulgents mounted an attack on the Committee of Public Safety, accusing them of being murderers.

Desmoulins addressed Robespierre directly, writing, "My dear Robespierre... my old school friend... Remember the lessons of history and philosophy: love is stronger, more lasting than fear."

On 25 December, provoked by Desmoulins' insistent challenges, Robespierre produced his "Report on the Principles of Revolutionary Government". Robespierre replied to the plea for an end to the Terror, justifying the collective authority of the National Convention, administrative centralisation, and the purging of local authorities. He said he had to avoid two cliffs: indulgence and severity. He could not consult the 18th-century political authors, because they had not foreseen such a course of events. He protested against the various factions that he believed threatened the government, such as the Hébertists and Dantonists. Robespierre strongly believed that the strict legal system was still necessary:

Robespierre would suppress chaos and anarchy: "the Government has to defend itself" gainst conspiratorsand "to the enemies of the people it owes only death". According to R. R. Palmer and Donald C. Hodges, this was the first important statement in modern times of a philosophy of dictatorship. Others see it as a natural consequence of political instability and conspiracy.

On 12 December, Robespierre attacked the wealthy foreigner Cloots in the Jacobin club of being a Prussian spy. Robespierre denounced the "de-Christianisers" as foreign enemies. The Indulgents mounted an attack on the Committee of Public Safety, accusing them of being murderers.

Desmoulins addressed Robespierre directly, writing, "My dear Robespierre... my old school friend... Remember the lessons of history and philosophy: love is stronger, more lasting than fear."

On 25 December, provoked by Desmoulins' insistent challenges, Robespierre produced his "Report on the Principles of Revolutionary Government". Robespierre replied to the plea for an end to the Terror, justifying the collective authority of the National Convention, administrative centralisation, and the purging of local authorities. He said he had to avoid two cliffs: indulgence and severity. He could not consult the 18th-century political authors, because they had not foreseen such a course of events. He protested against the various factions that he believed threatened the government, such as the Hébertists and Dantonists. Robespierre strongly believed that the strict legal system was still necessary:

Robespierre would suppress chaos and anarchy: "the Government has to defend itself" gainst conspiratorsand "to the enemies of the people it owes only death". According to R. R. Palmer and Donald C. Hodges, this was the first important statement in modern times of a philosophy of dictatorship. Others see it as a natural consequence of political instability and conspiracy.

File:Cécile Renault arrêtée chez Robespierre.jpeg, The arrest of Cécile Renaud in the courtyard of Duplay's house on 22 May 1794, etching by Matthias Gottfried Eichler after a drawing by Jean Duplessis-Bertaux.

File:Tuileries, façade regardant la cour du Carrousel (dessin) – Destailleur Paris tome 6, 1292 – Gallica 2013 (adjusted).jpg, The Committee of General Security was located in Hôtel de Brionne on the right; it gathered on the first floor. (The Tuileries Palace, which housed the Convention, is on the left).

File:Jean Marie Collot d'Herbois.jpg, Collot d'Herbois

File:Тальен на трибуне 9 термидора.jpg, On 9 Thermidor Tallien threatened in the Convention to use his dagger if the National Convention would not order the arrest of Robespierre.

File:Max Adamo Sturz Robespierres.JPG, The Fall of Robespierre in the Convention on 27 July 1794

At noon, Saint-Just entered the Convention and prepared to place blame on Billaud, Collot d'Herbois, and Carnot. After a few minutes, Tallien (who had a double reason for desiring Robespierre's end following Robespierre's refusal, the evening before, to release Theresa Cabarrus) interrupted him and began to speak against him. According to Tallien, "Robespierre wanted to attack us by turns, to isolate us, and finally he would be left one day only with the base and abandoned and debauched men who serve him". Almost thirty-five deputies spoke against Robespierre that day, most of them from The Mountain. As the accusations began to pile up, Saint-Just remained silent. Robespierre rushed toward the rostrum, appealed to the Plain to defend him against the Montagnards, but his voice was shouted down. Robespierre rushed to the benches of the Left but someone cried: "Get away from here; Condorcet used to sit here". He soon found himself at a loss for words after Vadier gave a mocking impression of him referring to the discovery of a letter under the mattress of the illiterate Catherine Théot.

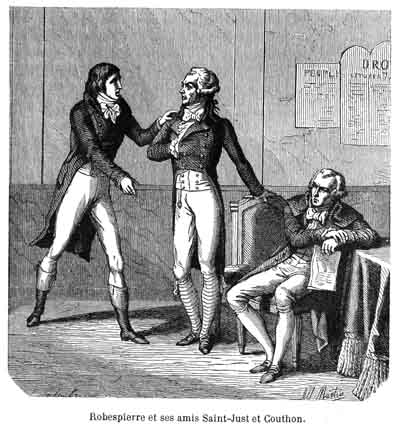

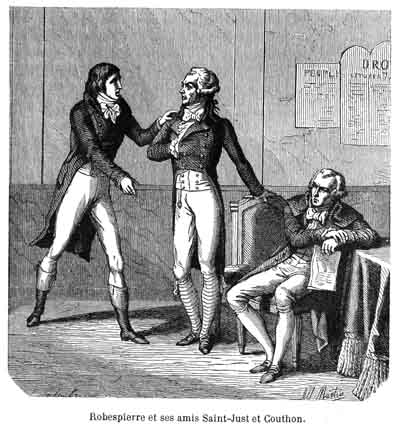

When Robespierre, very upset, was unable to speak, Garnier shouted, "The blood of Danton chokes him!" Robespierre then regained his voice: "Is it Danton you regret?... Cowards! Why didn't you defend him?" At some time called for Robespierre's arrest; Augustin Robespierre demanded to share his fate. The whole Convention agreed, including Couthon, and Saint-Just. Le Bas decided to join Saint-Just. Robespierre shouted that the revolution was lost when he descended the tribune. The five deputies were taken to the Committee of General Security and questioned.

Not long after, Hanriot was ordered to appear in the Convention; he warned the sections that there would be an attempt to murder Robespierre, and mobilised 2,400 National Guards in front of the town hall. What had happened was not very clear to their officers; either the Convention was closed down or the Paris Commune. Around six o'clock, the city council summoned an immediate meeting to consider the dangers threatening the fatherland. It gave orders to close the gates and to ring the tocsin. For the Convention, that was an illegal action without the permission of the two committees. It was decreed that anyone leading an "armed force" against the Convention would be regarded as an outlaw. The city council was in league with the Jacobins to bring off an insurrection, asking them to send over reinforcements from the galleries, "even the women who are regulars there".

At noon, Saint-Just entered the Convention and prepared to place blame on Billaud, Collot d'Herbois, and Carnot. After a few minutes, Tallien (who had a double reason for desiring Robespierre's end following Robespierre's refusal, the evening before, to release Theresa Cabarrus) interrupted him and began to speak against him. According to Tallien, "Robespierre wanted to attack us by turns, to isolate us, and finally he would be left one day only with the base and abandoned and debauched men who serve him". Almost thirty-five deputies spoke against Robespierre that day, most of them from The Mountain. As the accusations began to pile up, Saint-Just remained silent. Robespierre rushed toward the rostrum, appealed to the Plain to defend him against the Montagnards, but his voice was shouted down. Robespierre rushed to the benches of the Left but someone cried: "Get away from here; Condorcet used to sit here". He soon found himself at a loss for words after Vadier gave a mocking impression of him referring to the discovery of a letter under the mattress of the illiterate Catherine Théot.

When Robespierre, very upset, was unable to speak, Garnier shouted, "The blood of Danton chokes him!" Robespierre then regained his voice: "Is it Danton you regret?... Cowards! Why didn't you defend him?" At some time called for Robespierre's arrest; Augustin Robespierre demanded to share his fate. The whole Convention agreed, including Couthon, and Saint-Just. Le Bas decided to join Saint-Just. Robespierre shouted that the revolution was lost when he descended the tribune. The five deputies were taken to the Committee of General Security and questioned.

Not long after, Hanriot was ordered to appear in the Convention; he warned the sections that there would be an attempt to murder Robespierre, and mobilised 2,400 National Guards in front of the town hall. What had happened was not very clear to their officers; either the Convention was closed down or the Paris Commune. Around six o'clock, the city council summoned an immediate meeting to consider the dangers threatening the fatherland. It gave orders to close the gates and to ring the tocsin. For the Convention, that was an illegal action without the permission of the two committees. It was decreed that anyone leading an "armed force" against the Convention would be regarded as an outlaw. The city council was in league with the Jacobins to bring off an insurrection, asking them to send over reinforcements from the galleries, "even the women who are regulars there".

In the early evening, the five deputies were taken in a cab to different prisons; Robespierre to the Palais du Luxembourg, Couthon to "La Bourbe" and Saint-Just to the "Écossais". Augustin Robespierre was taken from Prison Saint-Lazare to La Force Prison, like Le Bas, who was refused at the Conciergerie. Around 8 p.m., Hanriot appeared at the Place du Carrousel in front of the Convention with forty armed men on horses, but was taken prisoner. After 9 p.m., the vice-president of the Tribunal Coffinhal went to the Committee of General Security with 3,000 men and their artillery. As Robespierre and his allies had been taken to a prison in the meantime, he succeeded only in freeing Hanriot and his adjutants.

How the five deputies escaped from prison was disputed. According to Le Moniteur Universel, the jailers refused to follow the order of arrest, taken by the Convention. According to Courtois and Fouquier-Tinville, the police administration was responsible for any in custody or release. Around 8 p.m., Robespierre was taken to the police administration on Île de la Cité, but refused to go to the Hôtel de Ville and insisted on being received in a prison. He hesitated for legal reasons for possibly two hours. At around 10 p.m., the mayor sent a second delegation to go and convince Robespierre to join the Commune movement. Robespierre was taken to the Hôtel de Ville. The Convention declared the five deputies (plus the supporting members) to be outlaws. It then appointed Barras and ordered troops totalling 4,000 men to be called out.

After a whole evening spent waiting in vain for action by the Commune, losing time in fruitless deliberation without supplies or instructions, the armed sections began to disperse. Around 400 men seem to have stayed on the Place de Grève, according to Courtois. At around 2 a.m., Barras and Bourdon, accompanied by several members of the Convention, arrived in two columns. Barras deliberately advanced slowly, in the hope of avoiding conflict by a display of force. Then Grenadiers burst into the Hôtel de Ville, followed by Léonard Bourdon and the Gendarmes. Fifty-one insurgents were gathering on the first floor. Robespierre and his allies withdrew to the smaller ''secrétariat''.

There are many stories about what happened next, but it seems in order to avoid capture, Augustin Robespierre took off his shoes and jumped from a broad cornice. He landed on some bayonets and a citizen, resulting in a pelvic fracture, several serious head contusions, and an alarming state of "weakness and anxiety". Le Bas handed a pistol to Robespierre, then killed himself with another pistol. According to Barras and Courtois, Robespierre wounded himself when he tried to commit suicide by pointing the pistol at his mouth, but the gendarme Méda prevented him from killing himself successfully. Couthon was found lying at the bottom of a staircase. Saint-Just gave himself up without a word. According to Méda, Hanriot tried to escape by a concealed staircase. Most sources say that Hanriot was thrown out of a window by Coffinhal after being accused of the disaster. (According to Ernest Hamel, it is one of the many legends spread by Barère.) Whatever the case, Hanriot landed in a small courtyard on a heap of glass. He had strength enough to crawl into a drain where he was found twelve hours later and taken to the Conciergerie. Coffinhal, who had successfully escaped, was arrested seven days later.

In the early evening, the five deputies were taken in a cab to different prisons; Robespierre to the Palais du Luxembourg, Couthon to "La Bourbe" and Saint-Just to the "Écossais". Augustin Robespierre was taken from Prison Saint-Lazare to La Force Prison, like Le Bas, who was refused at the Conciergerie. Around 8 p.m., Hanriot appeared at the Place du Carrousel in front of the Convention with forty armed men on horses, but was taken prisoner. After 9 p.m., the vice-president of the Tribunal Coffinhal went to the Committee of General Security with 3,000 men and their artillery. As Robespierre and his allies had been taken to a prison in the meantime, he succeeded only in freeing Hanriot and his adjutants.

How the five deputies escaped from prison was disputed. According to Le Moniteur Universel, the jailers refused to follow the order of arrest, taken by the Convention. According to Courtois and Fouquier-Tinville, the police administration was responsible for any in custody or release. Around 8 p.m., Robespierre was taken to the police administration on Île de la Cité, but refused to go to the Hôtel de Ville and insisted on being received in a prison. He hesitated for legal reasons for possibly two hours. At around 10 p.m., the mayor sent a second delegation to go and convince Robespierre to join the Commune movement. Robespierre was taken to the Hôtel de Ville. The Convention declared the five deputies (plus the supporting members) to be outlaws. It then appointed Barras and ordered troops totalling 4,000 men to be called out.

After a whole evening spent waiting in vain for action by the Commune, losing time in fruitless deliberation without supplies or instructions, the armed sections began to disperse. Around 400 men seem to have stayed on the Place de Grève, according to Courtois. At around 2 a.m., Barras and Bourdon, accompanied by several members of the Convention, arrived in two columns. Barras deliberately advanced slowly, in the hope of avoiding conflict by a display of force. Then Grenadiers burst into the Hôtel de Ville, followed by Léonard Bourdon and the Gendarmes. Fifty-one insurgents were gathering on the first floor. Robespierre and his allies withdrew to the smaller ''secrétariat''.

There are many stories about what happened next, but it seems in order to avoid capture, Augustin Robespierre took off his shoes and jumped from a broad cornice. He landed on some bayonets and a citizen, resulting in a pelvic fracture, several serious head contusions, and an alarming state of "weakness and anxiety". Le Bas handed a pistol to Robespierre, then killed himself with another pistol. According to Barras and Courtois, Robespierre wounded himself when he tried to commit suicide by pointing the pistol at his mouth, but the gendarme Méda prevented him from killing himself successfully. Couthon was found lying at the bottom of a staircase. Saint-Just gave himself up without a word. According to Méda, Hanriot tried to escape by a concealed staircase. Most sources say that Hanriot was thrown out of a window by Coffinhal after being accused of the disaster. (According to Ernest Hamel, it is one of the many legends spread by Barère.) Whatever the case, Hanriot landed in a small courtyard on a heap of glass. He had strength enough to crawl into a drain where he was found twelve hours later and taken to the Conciergerie. Coffinhal, who had successfully escaped, was arrested seven days later.

File:Sketch of Robespierre.jpg, Robespierre on the day of his execution; Sketch attributed to Jacques Louis David

File:Execution de Robespierre full.jpg, The execution of Couthon; the body of Adrien Nicolas Gobeau, ex-substitute of the public accuser Fouquier and member of the Commune, the first who suffered, is shown lying on the ground; Robespierre (#10) is shown holding a handkerchief to his mouth. Hanriot (#9) is covering his eye, which came out of its socket when he was arrested.

His reputation peaked in the 1920s, during the Third French Republic, when the influential French historian Albert Mathiez rejected the common view of Robespierre as demagogic, dictatorial, and fanatical. Mathiez argued he was an eloquent spokesman for the poor and oppressed, an enemy of royalist intrigues, a vigilant adversary of dishonest and corrupt politicians, a guardian of the First French Republic, an intrepid leader of the French Revolutionary government, and a prophet of a socially responsible state. Lenin referred to Robespierre as a " Bolshevik '' avant la lettre''" (before the term was coined) and erected the Robespierre Monument to him in 1918. In the Soviet Union, he was used as an example of a revolutionary figure. However the Marxist approach that portrayed Robespierre as a hero has largely faded away.

In 1941 Marc Bloch, a French historian, sighed disillusioned (a year before he decided to join the French Resistance): "Robespierrists, anti-robespierrists ... for pity's sake, just tell us who was Robespierre?" According to R. R. Palmer: the easiest way to justify Robespierre is to represent the other Revolutionists in an unfavourable or disgraceful light. This was the method used by Robespierre himself. Soboul argues that Robespierre and Saint-Just "were too preoccupied in defeating the interest of the bourgeoisie to give their total support to the sans-culottes, and yet too attentive to the needs of the sans-culottes to get support from the middle class". For Peter McPhee, Robespierre's achievements were monumental, but so was the tragedy of his final weeks of indecision. The members of the committee, together with members of the Committee of General Security, were as much responsible for the running of the Terror as Robespierre. They may have exaggerated his role to downplay their own contribution, and used him as a scapegoat after his death. Jean-Clément Martin and McPhee interpret the repression of the revolutionary government as a response to anarchy and popular violence, and not as the assertion of a precise ideology. Martin holds Tallien responsible for Robespierre's bad reputation, and that the " Thermidorians" invented the "Terror" as there is no law that proves its introduction.

He is a major figure in the history of France, and a controversial subject, studied by the favourable Jacobin School and the unfavorable neo-liberal school, by "lawyers and prosecutors". François Crouzet collected many interesting details from French historians dealing with Robespierre. In an interview Marcel Gauchet said that Robespierre confused his private opinion and virtue. The sale at Sotheby's in 2011 of selected manuscripts, including speeches, draft newspaper articles, drafts of reports to be read at the Convention, a fragment of the speech of 8 Thermidor, and a letter on virtue and happiness, kept by the Le Bas family after the death of Robespierre, sparked interest among historians and politicians; Pierre Serna published an article entitled: "We must save Robespierre!" in '' Le Monde'', and the Society of Robespierrist Studies launched a call for subscriptions, while the French Communist Party, the Socialist Party and the Radical Party of the Left alerted the French Ministry of Culture.

Many historians neglected Robespierre's attitude towards the French National Guard from July 1789, and as " public accuser", responsible for the officers within the police till April 1792. He then began promoting civilian armament and the creation of a revolutionary army of 23,000 men in his periodical. He defended the right of revolution and promoted a revolutionary armed force. Dubois-Crancé described Robespierre as the general of the Sans-culottes. The revisionist historian Furet thought that Terror was inherent in the ideology of the French Revolution and was not just a violent episode. Equally important is his conclusion that revolutionary violence is connected with extreme voluntarism. Furet was especially critical of the "Marxist line" of Albert Soboul.

Historians in support of Robespierre have been at pains to try to prove that he was not the dictator of France in the year II. McPhee stated that on several previous occasions, Robespierre had admitted that he was worn out; his personal and tactical judgement, once so acute, seem to have deserted him.

The assassination attempts made him suspicious to the point of obsession. There is a long line of historians "who blame Robespierre for all the less attractive episodes of the Revolution." Robespierre was not part of the celebrations of the bicentenary of the revolution. Jonathan Israel is sharply critical of Robespierre for repudiating the true values of the radical Enlightenment. He argues, "Jacobin ideology and culture under Robespierre was an obsessive Rousseauiste moral Puritanism steeped in authoritarianism, anti-intellectualism, and xenophobia, and it repudiated free expression, basic human rights, and democracy." He refers to the Girondin deputies Thomas Paine, Condorcet, Daunou, Cloots, Destutt and Abbé Gregoire denouncing Robespierre's ruthlessness, hypocrisy, dishonesty, lust for power, and intellectual mediocrity. According to Jeremy Popkin, he was undone by his obsession with the vision of an ideal republic. Zhu Xueqin became famous for his 1994 book titled ''The Demise of the Republic of Virtue: From Rousseau to Robespierre.'' For

His reputation peaked in the 1920s, during the Third French Republic, when the influential French historian Albert Mathiez rejected the common view of Robespierre as demagogic, dictatorial, and fanatical. Mathiez argued he was an eloquent spokesman for the poor and oppressed, an enemy of royalist intrigues, a vigilant adversary of dishonest and corrupt politicians, a guardian of the First French Republic, an intrepid leader of the French Revolutionary government, and a prophet of a socially responsible state. Lenin referred to Robespierre as a " Bolshevik '' avant la lettre''" (before the term was coined) and erected the Robespierre Monument to him in 1918. In the Soviet Union, he was used as an example of a revolutionary figure. However the Marxist approach that portrayed Robespierre as a hero has largely faded away.

In 1941 Marc Bloch, a French historian, sighed disillusioned (a year before he decided to join the French Resistance): "Robespierrists, anti-robespierrists ... for pity's sake, just tell us who was Robespierre?" According to R. R. Palmer: the easiest way to justify Robespierre is to represent the other Revolutionists in an unfavourable or disgraceful light. This was the method used by Robespierre himself. Soboul argues that Robespierre and Saint-Just "were too preoccupied in defeating the interest of the bourgeoisie to give their total support to the sans-culottes, and yet too attentive to the needs of the sans-culottes to get support from the middle class". For Peter McPhee, Robespierre's achievements were monumental, but so was the tragedy of his final weeks of indecision. The members of the committee, together with members of the Committee of General Security, were as much responsible for the running of the Terror as Robespierre. They may have exaggerated his role to downplay their own contribution, and used him as a scapegoat after his death. Jean-Clément Martin and McPhee interpret the repression of the revolutionary government as a response to anarchy and popular violence, and not as the assertion of a precise ideology. Martin holds Tallien responsible for Robespierre's bad reputation, and that the " Thermidorians" invented the "Terror" as there is no law that proves its introduction.

He is a major figure in the history of France, and a controversial subject, studied by the favourable Jacobin School and the unfavorable neo-liberal school, by "lawyers and prosecutors". François Crouzet collected many interesting details from French historians dealing with Robespierre. In an interview Marcel Gauchet said that Robespierre confused his private opinion and virtue. The sale at Sotheby's in 2011 of selected manuscripts, including speeches, draft newspaper articles, drafts of reports to be read at the Convention, a fragment of the speech of 8 Thermidor, and a letter on virtue and happiness, kept by the Le Bas family after the death of Robespierre, sparked interest among historians and politicians; Pierre Serna published an article entitled: "We must save Robespierre!" in '' Le Monde'', and the Society of Robespierrist Studies launched a call for subscriptions, while the French Communist Party, the Socialist Party and the Radical Party of the Left alerted the French Ministry of Culture.

Many historians neglected Robespierre's attitude towards the French National Guard from July 1789, and as " public accuser", responsible for the officers within the police till April 1792. He then began promoting civilian armament and the creation of a revolutionary army of 23,000 men in his periodical. He defended the right of revolution and promoted a revolutionary armed force. Dubois-Crancé described Robespierre as the general of the Sans-culottes. The revisionist historian Furet thought that Terror was inherent in the ideology of the French Revolution and was not just a violent episode. Equally important is his conclusion that revolutionary violence is connected with extreme voluntarism. Furet was especially critical of the "Marxist line" of Albert Soboul.

Historians in support of Robespierre have been at pains to try to prove that he was not the dictator of France in the year II. McPhee stated that on several previous occasions, Robespierre had admitted that he was worn out; his personal and tactical judgement, once so acute, seem to have deserted him.

The assassination attempts made him suspicious to the point of obsession. There is a long line of historians "who blame Robespierre for all the less attractive episodes of the Revolution." Robespierre was not part of the celebrations of the bicentenary of the revolution. Jonathan Israel is sharply critical of Robespierre for repudiating the true values of the radical Enlightenment. He argues, "Jacobin ideology and culture under Robespierre was an obsessive Rousseauiste moral Puritanism steeped in authoritarianism, anti-intellectualism, and xenophobia, and it repudiated free expression, basic human rights, and democracy." He refers to the Girondin deputies Thomas Paine, Condorcet, Daunou, Cloots, Destutt and Abbé Gregoire denouncing Robespierre's ruthlessness, hypocrisy, dishonesty, lust for power, and intellectual mediocrity. According to Jeremy Popkin, he was undone by his obsession with the vision of an ideal republic. Zhu Xueqin became famous for his 1994 book titled ''The Demise of the Republic of Virtue: From Rousseau to Robespierre.'' For

''Discours couronné par la Société royale des arts et des sciences de Metz, sur les questions suivantes, proposeés pour sujet du prix de l'année 1784''

* 1791 �

''Adresse de Maximilien Robespierre aux Français''

* 1792–1793 �

''Lettres de Maximilien Robespierre, membre de la Convention nationale de France, à ses commettans''

* 1794 �

''Lettre de Robespierre, au général Pichegru. Paris le 3 Thermidor, (21 Juillet) l'an 2 de la République Françoise = Brief van Robespierre, aan den generaal Pichegru. Parys, den 3 Thermidor, (21 July) het 2de jaar der Fransche Republiek''

* 1828 �

''Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint–Just, Payan ...: supprimés ou omis par Courtois: précédés du Rapport de ce député à la Convention Nationale''. Tome premierTome secondTome troisième

* 1830 �

''Mémoires authentiques de Maximilien de Robespierre, ornés de son portrait, et de facsimile de son écriture extraits de ses mémoirs''. Tome premierTome deuxième

* 1912–2022 – ''Œuvres complètes de Maximilien Robespierre'', 10 volumes, Société des études robespierristes, 1912–1967. Réimpression Société des études robespierristes, Phénix Éditions, 2000, 10 volumes. Réédition avec une nouvelle introduction de Claude Mazauric, Édition du Centenaire de la Société des études robespierristes, Éditions du Miraval, Enghien-les-Bains, 2007, 10 volumes et 1 volume de Compléments. Un onzième volume, paru en 2007, regroupe les textes omis lors de l'édition initiale.

An Introduction to the French Revolution and a Brief History of France (34 videos)

The Thermidorian Reaction (Part 1/2)

25. The Armies of the Revolution and Dumoriez's Betrayal

* La Révolution française (film) by

The French Revolution – Part 2 – English subtitles

{{DEFAULTSORT:Robespierre, Maximilien 1758 births 1794 deaths Maximilien 18th-century French male writers 18th-century French lawyers 18th-century French philosophers People from Arras Lycée Louis-le-Grand alumni 18th-century French jurists People of the War of the First Coalition Jacobins Montagnards French radicals French republicans French revolutionaries French deists Critics of atheism Critics of the Catholic Church People on the Committee of Public Safety French political philosophers Liberalism in France Left-wing politics in France Presidents of the National Convention Regicides of Louis XVI People of the Reign of Terror French social philosophers French people executed by guillotine during the French Revolution Executed French mass murderers Executed revolutionaries Leaders ousted by a coup Founders of religions French founders French religious leaders Politicide perpetrators

Atlantic slave trade

The Atlantic slave trade or transatlantic slave trade involved the transportation by slave traders of Slavery in Africa, enslaved African people to the Americas. European slave ships regularly used the triangular trade route and its Middle Pass ...

.

A radical Jacobin leader, Robespierre was elected as a deputy to the National Convention in September 1792, and in July 1793, he was appointed a member of the Committee of Public Safety. Robespierre faced growing disillusionment due in part to the politically motivated violence associated with him. Increasingly, members of the Convention turned against him, and accusations came to a head on 9 Thermidor. Robespierre was arrested and with around 90 others, he was executed without trial.

A figure deeply divisive during his lifetime, Robespierre's views and policies continue to evoke controversy. His legacy has been heavily influenced by his actual or perceived participation in repression of the Revolution's opponents, but he is notable for his progressive views for the time. Academic and popular discourse continues to engage in debates surrounding his legacy and reputation, particularly his ideas of virtue in regards to the revolution and its violence.

Early life

Maximilien de Robespierre was baptised on 6 May 1758 in Arras, Artois. His father, François Maximilien Barthélémy de Robespierre, a lawyer, married Jacqueline Marguerite Carrault, the daughter of a brewer, in January 1758. Maximilien, the eldest of four children, was born four months later. His siblings were Charlotte Robespierre, Henriette Robespierre, and Augustin Robespierre. Robespierre's mother died on 16 July 1764, after delivering a stillborn son at age 29. Charlotte's memoirs indicate that she believed that the death of their mother had a major effect on her brother. About three years after the death of his wife, their father left the children in Arras. Maximilien and his brother were raised by their maternal grandparents and his sisters were raised by their unmarried paternal aunts. Demonstrating literacy at an early age, Maximilien commenced his education at the Arras College when he was only eight. In October 1769, recommended by the bishop , he secured a scholarship at the prestigious Collège Louis-le-Grand in Paris. Among his peers were Camille Desmoulins and Stanislas Fréron. During his schooling, he developed a profound admiration for theRoman Republic

The Roman Republic ( ) was the era of Ancient Rome, classical Roman civilisation beginning with Overthrow of the Roman monarchy, the overthrow of the Roman Kingdom (traditionally dated to 509 BC) and ending in 27 BC with the establis ...

and the rhetoric skills of Cicero, Cato and Lucius Junius Brutus. In 1776 he earned the first prize for rhetoric.

His appreciation for the classics inspired him to aspire to Roman virtues, particularly the embodiment of Rousseau's citizen-soldier. Robespierre was drawn to the concepts of the influential '' philosophe'' regarding political reforms expounded in his work, '' The Social Contract''. Aligning with Rousseau, he considered the general will of the people as the foundation of political legitimacy. Robespierre's vision of revolutionary virtue and his strategy for establishing political authority through direct democracy can be traced back to the ideologies of Montesquieu and Mably. While some claim Robespierre coincidentally met Rousseau before the latter's passing, others argue that this account was apocryphal.

Formative years, 1780–1789

During his three-year study of law at the Sorbonne, Robespierre distinguished himself academically, culminating in his graduation in July 1780, where he received a special prize of 600 for his exceptional academic achievements and exemplary conduct. Admitted to the bar, he was appointed as one of the five judges in the local criminal court in March 1782. However, Robespierre soon resigned, due to his ethical discomfort in adjudicating capital cases, stemming from his opposition to the death penalty.

Robespierre was elected to the literary Academy of Arras in November 1783. The following year, the Academy of Metz honoured him with a medal for his essay pondering collective punishment, thus establishing him as a literary figure. ( Pierre Louis de Lacretelle and Robespierre shared the prize.)

In 1786 Robespierre passionately addressed inequality before the law, criticising the indignities faced by illegitimate or natural children, and later denouncing practices like ''lettres de cachet'' (imprisonment without a trial) and the marginalisation of women in academic circles. Robespierre's social circle expanded to include influential figures such as the lawyer Martial Herman, the officer and engineer Lazare Carnot and the teacher Joseph Fouché, all of whom would hold significance in his later endeavours. His role as the secretary of the Academy of Arras connected him with François-Noël Babeuf, a revolutionary land surveyor in the region.

In August 1788, King Louis XVI summoned the Estates-General to convene on 1 May 1789. Robespierre advocated in his ''Address to the Nation of Artois'' that following the customary mode of election by the members of the provincial estates would fail to adequately represent the people of France in the new Estates-General. In his electoral district, Arras, Robespierre began to assert his influence in politics through his ''Notice to the Residents of the Countryside'' in 1789, targeting local authorities and garnering the support of rural electors. On 26 April 1789, Robespierre secured his place as one of 16 deputies representing French Flanders in the Estates-General.

During his three-year study of law at the Sorbonne, Robespierre distinguished himself academically, culminating in his graduation in July 1780, where he received a special prize of 600 for his exceptional academic achievements and exemplary conduct. Admitted to the bar, he was appointed as one of the five judges in the local criminal court in March 1782. However, Robespierre soon resigned, due to his ethical discomfort in adjudicating capital cases, stemming from his opposition to the death penalty.

Robespierre was elected to the literary Academy of Arras in November 1783. The following year, the Academy of Metz honoured him with a medal for his essay pondering collective punishment, thus establishing him as a literary figure. ( Pierre Louis de Lacretelle and Robespierre shared the prize.)

In 1786 Robespierre passionately addressed inequality before the law, criticising the indignities faced by illegitimate or natural children, and later denouncing practices like ''lettres de cachet'' (imprisonment without a trial) and the marginalisation of women in academic circles. Robespierre's social circle expanded to include influential figures such as the lawyer Martial Herman, the officer and engineer Lazare Carnot and the teacher Joseph Fouché, all of whom would hold significance in his later endeavours. His role as the secretary of the Academy of Arras connected him with François-Noël Babeuf, a revolutionary land surveyor in the region.

In August 1788, King Louis XVI summoned the Estates-General to convene on 1 May 1789. Robespierre advocated in his ''Address to the Nation of Artois'' that following the customary mode of election by the members of the provincial estates would fail to adequately represent the people of France in the new Estates-General. In his electoral district, Arras, Robespierre began to assert his influence in politics through his ''Notice to the Residents of the Countryside'' in 1789, targeting local authorities and garnering the support of rural electors. On 26 April 1789, Robespierre secured his place as one of 16 deputies representing French Flanders in the Estates-General.

1789

On 6 June, Robespierre delivered his maiden speech in the Estates General, targeting the hierarchical structure of the church. His impassioned oratory prompted observers to comment, "This young man is as yet inexperienced; unaware of when to cease, but possesses an eloquence that sets him apart from the rest." By 13 June, Robespierre aligned with deputies, who later proclaimed themselves the National Assembly, asserting representation for 96% of the nation. On 9 July, the Assembly relocated to Paris and began deliberating a new constitution and taxation system. On 13 July, the National Assembly proposed reinstating the "bourgeois militia" in Paris to quell the unrest. The following day, the populace demanded weapons and stormed both the Hôtel des Invalides and the Bastille. The local militia transitioned into the National Guard, a move that distanced the most impoverished citizens from active involvement. During an altercation with Lally-Tollendal who advocated law and order, Robespierre reminded the citizens of their "recent defense of liberty", which paradoxically restricted their access to it. In October, alongside Louvet, Robespierre supported Maillard following the Women's March on Versailles. That same month, while the Constituent Assembly deliberated on male census suffrage on 22 October, Robespierre and a select few deputies opposed property requirements for voting and holding office. Through December and January Robespierre notably drew attention from marginalised groups, particularly Protestants,Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, people of African descent, domestic servants, and actors. A frequent orator in the Assembly, Robespierre championed the ideals in the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen but his views rarely garnered majority support among fellow deputies.

Despite his commitment to democratic principles, Robespierre did not adopt the change of dress influenced by the Revolution; instead he persistently donned knee-breeches and retained a meticulously groomed appearance with powdered, curled, and perfumed wig tied in a queue in line with the old-fashioned style of the 18th century. Some accounts described him as "nervous, timid, and suspicious".

Following the forcible relocation of the King and National Constituent Assembly from Versailles to Paris, Robespierre lived at 30 Rue de Saintonge in Le Marais, a district with relatively wealthy inhabitants. He shared an apartment on the third floor with Pierre Villiers who was his secretary for several months. Robespierre associated with the new Society of the Friends of the Constitution, commonly known as the Jacobin Club. Among these 1,200 men, Robespierre found a sympathetic audience. Equality before the law was the keystone of the Jacobin ideology. Beginning in October and continuing through January he made several speeches in response to proposals for property qualifications for voting and officeholding under the proposed constitution. This was a position he vigorously opposed, arguing in a speech on 22 October the position that he derived from Rousseau:

Following the forcible relocation of the King and National Constituent Assembly from Versailles to Paris, Robespierre lived at 30 Rue de Saintonge in Le Marais, a district with relatively wealthy inhabitants. He shared an apartment on the third floor with Pierre Villiers who was his secretary for several months. Robespierre associated with the new Society of the Friends of the Constitution, commonly known as the Jacobin Club. Among these 1,200 men, Robespierre found a sympathetic audience. Equality before the law was the keystone of the Jacobin ideology. Beginning in October and continuing through January he made several speeches in response to proposals for property qualifications for voting and officeholding under the proposed constitution. This was a position he vigorously opposed, arguing in a speech on 22 October the position that he derived from Rousseau: ... sovereignty resides in the people, in all the individuals of the people. Each individual therefore has the right to participate in making the law which governs him and in the administration of the public good which is his own. If not, it is not true that all men are equal in rights, that every man is a citizen.

1790

During the continuing debate on suffrage, Robespierre ended his speech of 25 January 1790 with a demand that "all Frenchmen must be admissible to all public positions without any other distinction than that of virtues and talents". On 31 March 1790 he was elected as president of the Jacobin Club. Robespierre supported the cooperation of all the National Guards in a general federation on 11 May. On 19 June he was elected secretary of the National Assembly. In July Robespierre demanded "fraternal equality" in salaries. Before the end of the year, he was seen as one of the leaders of the small body of the extreme left of the Assembly, known as "the thirty voices". On 5 December Robespierre delivered another speech on the National Guard. "To be armed for personal defence is the right of every man, to be armed to defend freedom and the existence of the common fatherland is the right of every citizen". Robespierre also coined the famous motto by adding the word fraternity on the flags of the National Guard.1791

In 1791, Robespierre gave 328 speeches, almost one a day. On 28 January, in the Assembly, he spoke on the organisation of the National Guard, On 27 and 28 April, Robespierre opposed plans to reorganise it and to restrict its membership to active citizens. He demanded that it should be reconstituted on a democratic basis, with an end to military decorations and an equal number of officers and soldiers in courts martial. He argued that the National Guard had to become the instrument of defending liberty rather than a threat to it. In the same month Robespierre published a pamphlet in which he argued the case for universal manhood suffrage. On 15 May, the Constituent Assembly declared full and equal citizenship for all free people of colour. In the debate Robespierre said: "I feel that I am here to defend the rights of men; I cannot consent to any amendment and I ask that the principle be adopted in its entirety." He descended from the rostrum in the middle of the repeated applause of the left and of all the galleries. On 16–18 May when the elections began, Robespierre proposed and carried the motion that no deputy who sat in the Constituent assembly could sit in the succeeding Legislative assembly. A tactical purpose of this self-denying ordinance was to block the ambitions of the old leaders of the Jacobins, Antoine Barnave, Adrien Duport, and Alexandre de Lameth, who aspired to create a constitutional monarchy roughly similar to that of England. On 28 May, Robespierre proposed all Frenchmen should be declared active citizens and eligible to vote. On 30 May, he delivered a speech on abolishing the death penalty, which the Assembly did not support. On 10 June, Robespierre delivered a speech on the state of the police and proposed to dismiss officers. On 11 June 1791 he was elected or nominated as (substitute) public prosecutor in the criminal tribunal preparing indictments. On 15 June, Pétion de Villeneuve became president of the "tribunal criminel provisoire", after Duport refused to work with Robespierre. After Louis XVI's flight to Varennes, the Assembly suspended the king from his duties on 25 June. Robespierre declared in the Jacobin Club on 13 July: "The current French constitution is a republic with a monarch. She is therefore neither a monarchy nor a republic. She is both." After the Champ de Mars massacre, the authorities ordered numerous arrests. Robespierre, after attending the Jacobin club, did not go back to the Rue Saintonge where he lodged, and asked Laurent Lecointre if he knew a patriot near the Tuileries who could put him up for the night. Lecointre suggested Duplay's house and took him there. Maurice Duplay, a cabinetmaker and ardent admirer, lived at 398 Rue Saint-Honoré near the Tuileries. After a few days, Robespierre decided to move in permanently, motivated by a desire to live closer to the Assembly and the Jacobin club. Robespierre took up residence in the back house where he was distracted by the noises of work. In September, the French Constitution of 1791 was accepted and the Assembly had therefore completed its task. On 30 September, the day of the dissolution of the Assembly, Robespierre opposed Jean Le Chapelier, who wanted to proclaim an end to the revolution and restrict freedom of expression. He succeeded in getting any requirement for inspection out of the constitution's guarantee of freedom of expression: "The freedom of every man to speak, to write, to print and publish his thoughts, without the writings having to be subject to censorship or inspection prior to their publication..." Pétion and Robespierre were brought back in triumph to their homes. Madame Roland labelled Pétion de Villeneuve, François Buzot, and Robespierre the "incorruptibles" in honour of their principles, their modest ways of living, and their refusal to take bribes. On 16 October, Robespierre delivered a speech in Arras; one week later in Béthune. On 28 November, he was back in the Jacobin club, where he met with a triumphant reception. Collot d'Herbois gave his chair to Robespierre, who presided that evening. On 5 December he gave a speech on the organisation of the Garde National, which he saw as a unique institution born from the ideals of the French Revolution. On 11 December, Robespierre was finally installed as '' accusateur public''.Opposition to war with Austria, 1791–1792

The Declaration of Pillnitz issued by Austria and Prussia on 27 August 1791 warned the people of France not to harm Louis XVI or these nations would "militarily intervene". Brissot rallied the support of the Legislative Assembly for war with Austria. As Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Danton and Robespierre had not been elected in the new legislature, thanks to the Self-Denying Ordinance, anti-war politics mainly took place outside the Assembly. On 18 December 1791, Robespierre gave a second speech at the Jacobin club against war, warning against the threat of dictatorship stemming from it:

At the end of December, Guadet, the chairman of the Assembly, suggested that a war would be a benefit to the nation and boost the economy. Marat and Robespierre opposed him, arguing that victory would create a dictatorship, while defeat would restore the king to his former powers.

This opposition from expected allies irritated the Girondins, and the war became a major point of contention between the factions. In his third speech on the war, Robespierre countered on 25 January 1792 in the Jacobin club, "A revolutionary war must be waged to free subjects and slaves from unjust tyranny, not for the traditional reasons of defending dynasties and expanding frontiers..." Robespierre argued such a war could only favour the forces of counter-revolution, since it would play into the hands of those who opposed the sovereignty of the people. The risks of Caesarism were clear: "in troubled periods of history, generals often became the arbiters of the fate of their countries." Robespierre failed to gather a majority, but his speech was nevertheless published and sent to all clubs and Jacobin societies of France.

On 10 February 1792, Robespierre gave a speech on how to save the State and Liberty. He advocated specific measures to strengthen, not so much the national defences as the forces that could be relied on to defend the revolution. Robespierre promoted a people's army, continuously under arms and able to impose its will on Feuillants and Girondins in the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI and the Legislative Assembly. The Jacobins decided to study his speech before deciding whether it should be printed.

On 26 March, Guadet accused Robespierre of superstition, relying on divine providence. Shortly after Robespierre was accused by Brissot and Guadet of "trying to become the idol of the people". Being against the war, Robespierre was also accused of acting as a secret agent for the " Austrian Committee". The Girondins planned strategies to out-maneuver Robespierre's influence among the Jacobins. On 27 April, as part of his speech responding to the accusations by Brissot and Guadet against him, he threatened to leave the Jacobins, claiming he preferred to continue his mission as an ordinary citizen.

On 17 May, Robespierre released the first issue of his weekly periodical (''The Defender of the Constitution''). In this publication, he criticised Brissot and expressed his scepticism over the war movement. The periodical, printed by his neighbour Nicolas, served multiple purposes: to print his speeches, to counter the influence of the royal court in public policy, to defend him from the accusations of Girondist leaders; and to give voice to the economic and democratic interests of the broader masses in Paris and defend their rights.

The Declaration of Pillnitz issued by Austria and Prussia on 27 August 1791 warned the people of France not to harm Louis XVI or these nations would "militarily intervene". Brissot rallied the support of the Legislative Assembly for war with Austria. As Jean-Paul Marat, Georges Danton and Robespierre had not been elected in the new legislature, thanks to the Self-Denying Ordinance, anti-war politics mainly took place outside the Assembly. On 18 December 1791, Robespierre gave a second speech at the Jacobin club against war, warning against the threat of dictatorship stemming from it:

At the end of December, Guadet, the chairman of the Assembly, suggested that a war would be a benefit to the nation and boost the economy. Marat and Robespierre opposed him, arguing that victory would create a dictatorship, while defeat would restore the king to his former powers.

This opposition from expected allies irritated the Girondins, and the war became a major point of contention between the factions. In his third speech on the war, Robespierre countered on 25 January 1792 in the Jacobin club, "A revolutionary war must be waged to free subjects and slaves from unjust tyranny, not for the traditional reasons of defending dynasties and expanding frontiers..." Robespierre argued such a war could only favour the forces of counter-revolution, since it would play into the hands of those who opposed the sovereignty of the people. The risks of Caesarism were clear: "in troubled periods of history, generals often became the arbiters of the fate of their countries." Robespierre failed to gather a majority, but his speech was nevertheless published and sent to all clubs and Jacobin societies of France.

On 10 February 1792, Robespierre gave a speech on how to save the State and Liberty. He advocated specific measures to strengthen, not so much the national defences as the forces that could be relied on to defend the revolution. Robespierre promoted a people's army, continuously under arms and able to impose its will on Feuillants and Girondins in the Constitutional Cabinet of Louis XVI and the Legislative Assembly. The Jacobins decided to study his speech before deciding whether it should be printed.

On 26 March, Guadet accused Robespierre of superstition, relying on divine providence. Shortly after Robespierre was accused by Brissot and Guadet of "trying to become the idol of the people". Being against the war, Robespierre was also accused of acting as a secret agent for the " Austrian Committee". The Girondins planned strategies to out-maneuver Robespierre's influence among the Jacobins. On 27 April, as part of his speech responding to the accusations by Brissot and Guadet against him, he threatened to leave the Jacobins, claiming he preferred to continue his mission as an ordinary citizen.

On 17 May, Robespierre released the first issue of his weekly periodical (''The Defender of the Constitution''). In this publication, he criticised Brissot and expressed his scepticism over the war movement. The periodical, printed by his neighbour Nicolas, served multiple purposes: to print his speeches, to counter the influence of the royal court in public policy, to defend him from the accusations of Girondist leaders; and to give voice to the economic and democratic interests of the broader masses in Paris and defend their rights.

Insurrectionary Commune of Paris, 1792

February–July 1792

On 15 February, Robespierre failed to get elected to the city council (''Conseil général''); on the same day the installation of the criminal trial court of the department of Paris took place. For Robespierre this meant a thankless position as public prosecutor. Robespierre was responsible for the coordination of the local and the federal police in the department and the sections. When the Legislative Assembly declared war against Austria on 20 April 1792, Robespierre stated that the French people must arm themselves, whether to fight abroad or to prevent despotism at home. An isolated Robespierre responded by working to reduce the political influence of the officer class and the king. On 23 April Robespierre demanded that Marquis de Lafayette, the head of the Army of the Centre, step down. While arguing for the welfare of common soldiers, Robespierre urged new promotions to mitigate the domination of the officer class by the aristocratic and royalist École Militaire and the conservative National Guard. Along with other Jacobins, he urged the creation of an in Paris, consisting of at least 20,000–23,000 men, to defend the city, "liberty" (the revolution), maintain order and educate the members in democratic and republican principles, an idea he borrowed fromJean-Jacques Rousseau

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (, ; ; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Republic of Geneva, Genevan philosopher (''philosophes, philosophe''), writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Age of Enlightenment through ...

. According to Jean Jaures, he considered this even more important than the right to strike.

On 29 May 1792, the Assembly dissolved the Constitutional Guard, suspecting it of royalist and counter-revolutionary sympathies. In early June 1792, Robespierre proposed an end to the monarchy and the subordination of the Assembly to the general will. The monarchy faced an abortive demonstration of 20 June.

Because French forces suffered disastrous defeats and a series of defections at the onset of the war, Robespierre and Marat feared the possibility of a military coup d'état. One was led by Lafayette, head of the National Guard, who at the end of June advocated the suppression of the Jacobin Club. Robespierre publicly attacked him in scathing terms:

On 2 July, the Assembly authorised the National Guard to go to the Festival of Federation on 14 July, circumventing a royal veto. On 11 July, the Jacobins won an emergency vote in the wavering Assembly, declaring the nation in danger and drafting all Parisians with pikes into the National Guard. On 15 July, Billaud-Varenne in the Jacobin club outlined the program for the next insurrection: the deportation of the Bourbons and "enemies of the people", the cleansing of the National Guard, the election of a Convention, the "transfer of the Royal veto to the people", and exemption of the poorest from taxation. On 24 July a "Central Office of Co-ordination" was formed and the sections received the right to be in a "permanent" session. On 25 July, according to the , Carnot promoted the use of pikes and provided to every citizen. On 29 July Robespierre called for the deposition of the King and the election of a Convention.

August 1792

On 1 August, the Assembly voted on Carnot's proposal, enforcing the distribution of pikes to all citizens, excluding vagabonds. By 3 August, the mayor and 47 sections demanded the removal of the king. On 5 August Robespierre disclosed the discovery of a plan for the king to escape to Château de Gaillon. Aligning with Robespierre's stance, almost all sections in Paris rallied for the dethronement of the king and issued a decisive ultimatum. Brissot urged the preservation of the constitution, advocating against both the dethronement of the king and the election of a new assembly. Simultaneously, the Council of Ministers recommended the arrest of Danton, Marat and Robespierre if they attended the Jacobin club. In the early hours of Friday, 10 August 30,000 Fédérés (volunteers hailing from the countryside) and sans-culottes (militant citizens from the Paris) mounted a successful assault upon the royal palace of the Tuileries. Robespierre considered it a triumph for the "passive" (non-voting) citizens. The Assembly, rattled by the events, suspended the king's powers and authorised the election of a new National Convention in the light of the changing role of the monarchy. On the night of 11 August, Robespierre secured a position in the Paris Commune, representing the ''Section de Piques'', his residential district. The governing committee advocated universal male suffrage in the election of the new National Convention. Despite Camille Desmoulins' belief that the turmoil had concluded, Robespierre asserted that it marked merely the beginning. By 13 August, Robespierre openly opposed the reinforcement of the départements. Subsequently, Danton invited him to join the Council of Justice. Robespierre published the twelfth and final edition of ''Le Défenseur de la Constitution'', serving as an account and political testament. On 16 August, Robespierre submitted a petition to the Legislative Assembly, endorsed by the Paris Commune, urging the establishment of a provisional Revolutionary Tribunal specifically tasked with dealing with perceived "traitors" and " enemies of the people". The following day, he was appointed as one of eight judges for this tribunal. However, citing a lack of impartiality, Robespierre declined to preside over it. This decision drew criticism. The Prussian army crossed the French frontier on 19 August. To fortify defence, the Paris armed sections were integrated into 48 battalions of the National Guard under Santerre's command. The Assembly decreed that all the nonjuring priests must leave Paris within a week and leave the country within two weeks. On 28 August, the assembly ordered a curfew for the next two days. The city gates were closed; all communication with the country was stopped. At the behest of Justice Minister Danton, thirty commissioners from the sections were ordered to search every suspect house for weapons, munitions, swords, carriages, and horses. "As a result of this inquisition, more than 1,000 "suspects" were added to the immense body of political prisoners already confined in the jails and convents of the city". Marat and Robespierre both disliked Condorcet who proposed that the " enemies of the people" belonged to the whole nation and should be judged constitutionally in its name. On 30 August the interim minister of Interior Roland and Guadet tried to suppress the influence of the Commune because the searches of suspect houses had been completed. The Assembly, tired of the pressures, declared the Commune illegal and suggested the organisation of communal elections. Robespierre was no longer willing to cooperate with Brissot and Roland. On Sunday morning 2 September the members of the Commune, gathering in the town hall to proceed the election of deputies to the National Convention, decided to maintain their seats and have Roland and Brissot arrested.National Convention

Elections

On 2 September, the 1792 French National Convention election began. Meanwhile Paris was organising its defence against the Prussians, but there was a lack of arms for the thousands of volunteers. Danton delivered a speech in which he said: "We ask that anyone who refuses to serve in person, or surrender their weapons, is punished with death." His speech acted as a call for direct action among the citizens, as well as a strike against the external enemy. Not long after, the September Massacres began. Robespierre and Manuel, the public prosecutor, responsible for the police administration, visited the Temple prison to check on the safety of the royal family.