HMS Warspite (03) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Warspite'' was one of five s built for the

The 5th Battle Squadron then headed

The 5th Battle Squadron then headed

In 1919, ''Warspite'' joined the 2nd Battle Squadron, part of the newly formed Atlantic Fleet, and undertook regular spring cruises to the

In 1919, ''Warspite'' joined the 2nd Battle Squadron, part of the newly formed Atlantic Fleet, and undertook regular spring cruises to the  Additionally, her superstructure was radically altered, allowing two cranes and an aircraft hangar to be fitted. This could carry four aircraft, but ''Warspite'' typically carried only two: from 1938 to 1941 these were

Additionally, her superstructure was radically altered, allowing two cranes and an aircraft hangar to be fitted. This could carry four aircraft, but ''Warspite'' typically carried only two: from 1938 to 1941 these were

''Warspite''s first task was to escort convoy HX 9 carrying fuel from Nova Scotia to the UK. She was diverted northwards in pursuit of the German battleships and which had sunk the

''Warspite''s first task was to escort convoy HX 9 carrying fuel from Nova Scotia to the UK. She was diverted northwards in pursuit of the German battleships and which had sunk the

''Warspite'' arrived safely in

''Warspite'' arrived safely in

In mid-August, she set out to bombard

In March 1941, to support the planned German invasion of the Balkans, Vice Admiral Angelo Iachino's Italian fleet, led by the battleship , sailed to intercept Allied convoys between Egypt and Greece. Warned of the Italian intentions by intelligence from the

In March 1941, to support the planned German invasion of the Balkans, Vice Admiral Angelo Iachino's Italian fleet, led by the battleship , sailed to intercept Allied convoys between Egypt and Greece. Warned of the Italian intentions by intelligence from the

During the

''Warspite'' joined the

''Warspite'' joined the

Between 2 and 3 September, ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' covered the

Between 2 and 3 September, ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' covered the  On 14 September, Force H was recalled to the UK to begin preparations for the invasion of France, but ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' were detached to provide support for Allied forces at

On 14 September, Force H was recalled to the UK to begin preparations for the invasion of France, but ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' were detached to provide support for Allied forces at

At Rosyth, ''Warspite''s 6-inch guns were removed and plated in, and a concrete caisson covered the hole left by the German missile. One of her boiler rooms and the X turret could not be repaired, remaining out of action for the remainder of her career. She left

At Rosyth, ''Warspite''s 6-inch guns were removed and plated in, and a concrete caisson covered the hole left by the German missile. One of her boiler rooms and the X turret could not be repaired, remaining out of action for the remainder of her career. She left

A memorial stone was placed near the sea wall at

A memorial stone was placed near the sea wall at

Maritimequest HMS Warspite Photo Gallery

* ttps://www.jutlandcrewlists.org/warspite Battle of Jutland Crew Lists Project - HMS Warspite Crew List {{DEFAULTSORT:Warspite (1913) Queen Elizabeth-class battleships Ships built in Plymouth, Devon 1913 ships World War I battleships of the United Kingdom World War II battleships of the United Kingdom Maritime incidents in September 1943 Maritime incidents in 1947

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by Kingdom of England, English and Kingdom of Scotland, Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were foug ...

during the early 1910s. Completed during the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fig ...

in 1915, she was assigned to the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

and participated in the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vic ...

. Other than that battle, and the inconclusive Action of 19 August, her service during the war generally consisted of routine patrols and training in the North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Norway, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium. An epeiric sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian S ...

. During the interwar period the ship was deployed in the Atlantic Ocean

The Atlantic Ocean is the second-largest of the world's five oceans, with an area of about . It covers approximately 20% of Earth#Surface, Earth's surface and about 29% of its water surface area. It is known to separate the "Old World" of Afr ...

and the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

, often serving as flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically the f ...

, and was thoroughly modernised in the mid-1930s.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, ''Warspite'' was involved in the Norwegian Campaign in early 1940 and was transferred to the Mediterranean later that year where the ship participated in fleet actions against the Royal Italian Navy

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the Italian constitutional referendum, 1946, birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' ch ...

() while also escorting convoys and bombarding Italian troops ashore. She was damaged by German aircraft during the Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (german: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta, el, Μάχη της Κρήτης), codenamed Operation Mercury (german: Unternehmen Merkur), was a major Axis airborne and amphibious operation during World War II to capture the islan ...

in mid-1941 and required six months of repairs in the United States. They were completed after the start of the Pacific War in December and the ship sailed across the Pacific

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

to join the Eastern Fleet in the Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

in early 1942. ''Warspite'' returned home in mid-1943 to conduct naval gunfire support

Naval gunfire support (NGFS) (also known as shore bombardment) is the use of naval artillery to provide fire support for amphibious assault and other troops operating within their range. NGFS is one of a number of disciplines encompassed by th ...

as part of Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

during the Italian campaign. She was badly damaged by German radio-controlled

Radio control (often abbreviated to RC) is the use of control signals transmitted by radio to remote control, remotely control a device. Examples of simple radio control systems are garage door openers and keyless entry systems for vehicles, in ...

glider bomb

A glide bomb or stand-off bomb is a standoff weapon with flight control surfaces to give it a flatter, gliding flight path than that of a conventional bomb without such surfaces. This allows it to be released at a distance from the target r ...

s during the landings at Salerno

Operation Avalanche was the codename for the Allied landings near the port of Salerno, executed on 9 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II. The Italians withdrew from the war the day before the invasion, bu ...

and spent most of the next year under repair. The ship bombarded German positions during the Normandy landings

The Normandy landings were the landing operations and associated airborne operations on Tuesday, 6 June 1944 of the Allied invasion of Normandy in Operation Overlord during World War II. Codenamed Operation Neptune and often referred to as ...

and on Walcheren Island in 1944, despite not being fully repaired. These actions earned her the most battle honour

A battle honour is an award of a right by a government or sovereign to a military unit to emblazon the name of a battle or operation on its flags ("colours"), uniforms or other accessories where ornamentation is possible.

In European military t ...

s ever awarded to an individual ship in the Royal Navy. For this and other reasons, ''Warspite'' gained the nickname the ''"Grand Old Lady"'' after a comment made by Admiral Sir Andrew Cunningham in 1943 while she was his flagship.

When she was launched in 1913 the use of oil as fuel and untried 15-inch guns were revolutionary concepts in the naval arms race between Britain and Germany, a considerable risk for Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty

The First Lord of the Admiralty, or formally the Office of the First Lord of the Admiralty, was the political head of the English and later British Royal Navy. He was the government's senior adviser on all naval affairs, responsible for the di ...

, and Admiral of the Fleet Sir Jackie Fisher, who had advocated the design. However, the new "fast battleship

A fast battleship was a battleship which emphasised speed without – in concept – undue compromise of either armor or armament. Most of the early World War I-era dreadnought battleships were typically built with low design speeds, ...

s" proved to be an outstanding success during the First World War. Decommissioned in 1945, ''Warspite'' ran aground under tow to be scrapped in 1947 on rocks near Prussia Cove

Prussia Cove ( kw, Porth Legh), formerly called King's Cove, is a small private estate on the coast of Mount's Bay and to the east of Cudden Point, west Cornwall, England, United Kingdom. Part of the area is designated as a Site of Special Scien ...

, Cornwall

Cornwall (; kw, Kernow ) is a historic county and ceremonial county in South West England. It is recognised as one of the Celtic nations, and is the homeland of the Cornish people. Cornwall is bordered to the north and west by the Atlan ...

, and was eventually broken up nearby.

Design and description

The ''Queen Elizabeth''-class ships were designed to form a fast squadron for the fleet that was intended to operate against the leading ships of the opposingbattleline

The line of battle is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputed—it has been variously claimed for dates ranging from 1502 to 1652. Line-of-battle tacti ...

. This required maximum offensive power and a speed several knots

A knot is a fastening in rope or interwoven lines.

Knot may also refer to:

Places

* Knot, Nancowry, a village in India

Archaeology

* Knot of Isis (tyet), symbol of welfare/life.

* Minoan snake goddess figurines#Sacral knot

Arts, entertainmen ...

faster than any other battleship to allow them to defeat any type of ship.

''Warspite'' had a length overall of , a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

* Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

** Laser beam

* Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially localized g ...

of and a deep draught of . She had a normal displacement

Displacement may refer to:

Physical sciences

Mathematics and Physics

*Displacement (geometry), is the difference between the final and initial position of a point trajectory (for instance, the center of mass of a moving object). The actual path ...

of and displaced at deep load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into we ...

. She was powered by two sets of Parsons steam turbine

A steam turbine is a machine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work on a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Charles Parsons in 1884. Fabrication of a modern steam turb ...

s, each driving two shafts using steam from 24 Yarrow boiler

Yarrow boilers are an important class of high-pressure water-tube boilers. They were developed by

Yarrow & Co. (London), Shipbuilders and Engineers and were widely used on ships, particularly warships.

The Yarrow boiler design is characteristic ...

s. The turbines were rated at and intended to reach a maximum speed of . The ship had a range of at a cruising speed of . Her crew numbered 1,025 officers and ratings in 1915 and 1,220 in 1920.

The ''Queen Elizabeth'' class was equipped with eight breech-loading

A breechloader is a firearm in which the user loads the ammunition ( cartridge or shell) via the rear (breech) end of its barrel, as opposed to a muzzleloader, which loads ammunition via the front ( muzzle).

Modern firearms are generally b ...

(BL) Mk I guns in four twin-gun turret

A gun turret (or simply turret) is a mounting platform from which weapons can be fired that affords protection, visibility and ability to turn and aim. A modern gun turret is generally a rotatable weapon mount that houses the crew or mechani ...

s, in two superfiring pairs fore and aft of the superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

, designated 'A', 'B', 'X', and 'Y' from front to rear. Twelve of the fourteen BL Mk XII guns were mounted in casemate

A casemate is a fortified gun emplacement or armored structure from which guns are fired, in a fortification, warship, or armoured fighting vehicle.Webster's New Collegiate Dictionary

When referring to antiquity, the term "casemate wall" mean ...

s along the broadside of the vessel amidships

This glossary of nautical terms is an alphabetical listing of terms and expressions connected with ships, shipping, seamanship and navigation on water (mostly though not necessarily on the sea). Some remain current, while many date from the 17th ...

; the remaining pair were mounted on the forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is the phrase " b ...

deck near the aft funnel

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its construc ...

and were protected by gun shield

A U.S. Marine manning an M240 machine gun equipped with a gun shield

A gun shield is a flat (or sometimes curved) piece of armor designed to be mounted on a crew-served weapon such as a machine gun

A machine gun is a fully automatic, ri ...

s. The anti-aircraft (AA) armament were composed of two quick-firing (QF) 20 cwt Mk I"Cwt" is the abbreviation for hundredweight

The hundredweight (abbreviation: cwt), formerly also known as the centum weight or quintal, is a British imperial and US customary unit of weight or mass. Its value differs between the US and British imperial systems. The two values are distin ...

, 20 cwt referring to the weight of the gun. guns. The ships were fitted with four submerged 21-inch (533 mm) torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed abo ...

s, two on each broadside.

''Warspite'' was completed with two fire-control directors fitted with rangefinder

A rangefinder (also rangefinding telemeter, depending on the context) is a device used to measure distances to remote objects. Originally optical devices used in surveying, they soon found applications in other fields, such as photography an ...

s. One was mounted above the conning tower, protected by an armoured hood, and the other was in the spotting top above the tripod mast

The tripod mast is a type of mast used on warships from the Edwardian era onwards, replacing the pole mast. Tripod masts are distinctive using two large (usually cylindrical) support columns spread out at angles to brace another (usually vertical ...

. Each turret was also fitted with a 15-foot rangefinder. The main armament could be controlled by 'B' turret as well. The secondary armament was primarily controlled by directors mounted on each side of the compass platform on the foremast once they were fitted in July 1917.

The waterline belt of the ''Queen Elizabeth'' class consisted of Krupp cemented armour (KC) that was thick over the ships' vitals. The gun turrets were protected by of KC armour and were supported by barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protectio ...

s thick. The ships had multiple armoured decks that ranged from in thickness. The main conning tower was protected by 13 inches of armour. After the Battle of Jutland, 1 inch of high-tensile steel

Carbon steel is a steel with carbon content from about 0.05 up to 2.1 percent by weight. The definition of carbon steel from the American Iron and Steel Institute (AISI) states:

* no minimum content is specified or required for chromium, cobal ...

was added to the main deck over the magazines

A magazine is a periodical publication, generally published on a regular schedule (often weekly or monthly), containing a variety of content. They are generally financed by advertising, purchase price, prepaid subscriptions, or by a combina ...

and additional anti-flash equipment was added in the magazines.

The ship was fitted with flying-off platforms mounted on the roofs of 'B' and 'X' turrets in 1918, from which fighters and reconnaissance aircraft could launch. Exactly when the platforms were removed is unknown, but no later than ''Warspite''s 1934–1937 reconstruction.

Construction and career

''Warspite'', the sixth warship of the Royal Navy to carry the name, waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

on 21 October 1912 at Devonport Royal Dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Devonport (HMNB Devonport) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Portsmouth) and is the sole nuclear repair and refuelling facility for the R ...

, launched on 26 November 1913, and completed in April 1915 under the command of Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

Edward Phillpotts. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 30. ''Warspite'' joined the 2nd Battle Squadron

The 2nd Battle Squadron was a naval squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 2nd Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet. After World War I the Grand Fleet was reverted to its original name, ...

of the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

following a number of acceptance trials, including gunnery trials, which saw Churchill present when she fired her 15-inch (381 mm) guns. Churchill was suitably impressed with their accuracy and power. In late 1915, ''Warspite'' was grounded in the River Forth

The River Forth is a major river in central Scotland, long, which drains into the North Sea on the east coast of the country. Its drainage basin covers much of Stirlingshire in Scotland's Central Belt. The Gaelic name for the upper reach of ...

causing some damage to her hull; she had been led by her escorting destroyers down the small ships channel. After undergoing repairs for two months at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style subur ...

and Jarrow

Jarrow ( or ) is a town in South Tyneside in the county of Tyne and Wear, England. It is east of Newcastle upon Tyne. It is situated on the south bank of the River Tyne, about from the east coast. It is home to the southern portal of the ...

, she rejoined the Grand Fleet, this time as part of the new 5th Battle Squadron

The 5th Battle Squadron was a squadron of the British Royal Navy consisting of battleships. The 5th Battle Squadron was initially part of the Royal Navy's Second Fleet. During the First World War, the Home Fleet was renamed the Grand Fleet.

Hi ...

which had been created for ''Queen Elizabeth''-class ships. In early December, ''Warspite'' was involved in another incident when, during an exercise, she collided with her sister ship , which caused considerable damage to ''Warspite''s bow. She made it back to Scapa Flow and from there to Devonport for more repair work, rejoining the fleet on Christmas Eve 1915.

First World War

Battle of Jutland (1916)

Following the German raid on Lowestoft in April 1916, ''Warspite'' and the 5th Battle Squadron were temporarily assigned to Vice-Admiral David Beatty'sBattlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of at ...

Force. On 31 May, ''Warspite'' was deployed with the squadron to fight in the Battle of Jutland

The Battle of Jutland (german: Skagerrakschlacht, the Battle of the Skagerrak) was a naval battle fought between Britain's Royal Navy Grand Fleet, under Admiral Sir John Jellicoe, and the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet, under Vic ...

, the largest naval encounter between Britain and Germany during the war. Following a signalling error, the battleships were left trailing Beatty's fast ships during the battlecruiser action, and the 5th Battle Squadron was exposed to heavy fire from the German High Seas Fleet as the force turned away to the north, although ''Warspite'' was able to score her first hit on the battlecruiser .

The 5th Battle Squadron then headed

The 5th Battle Squadron then headed north

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating direction or geography.

Etymology

The word ''no ...

, exchanging fire with both Hipper's battlecruiser force and the leading elements of Scheer's battleships, damaging . When the squadron turned to join the Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from the ...

, the damage from a shell hitting the port-wing engine room caused ''Warspite''s steering to jam as she attempted to avoid her sister ships and . Ballantyne, 2013, p. 50. Captain Phillpotts decided to maintain course, in effect circling, rather than come to a halt and reverse. This decision exposed ''Warspite'' and made her a tempting target; she was hit multiple times, but inadvertently diverted attention from the armoured cruiser , which had been critically damaged whilst attacking the leading elements of the German fleet. This action gained her the admiration of ''Warrior''s surviving crew, who believed that ''Warspite''s movement had been intentional.

The crew regained control of ''Warspite'' after two full circles. Their efforts to end the circular motion placed her on a course which took her towards the German fleet. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 51. The rangefinders and the transmission station were non-functional and only "A" turret could fire, albeit under local control with 12 salvos falling short of their target. Sub Lieutenant Herbert Annesley Packer

Admiral Sir Herbert ("Bertie") Annesley Packer KCB, CBE (9 October 1894 – 23 September 1962) was an officer in the British Royal Navy and ended his career as an Admiral and Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic.

Family background

The only son ...

was subsequently promoted for his command of "A" turret. Rather than continue, ''Warspite'' was stopped for ten minutes so the crew could make repairs. They succeeded in correcting the problem, but the ship would be plagued with steering irregularities for the rest of her naval career. As the light faded the Grand Fleet crossed ahead of the German battle line and opened fire, forcing the High Seas Fleet to retreat and allowing ''Warspite'' to slip away.

''Warspite'' was hit fifteen times during the battle, and had 14 killed and 16 wounded; among the latter warrant officer Walter Yeo

Walter Ernest O'Neil Yeo (20 October 1890 – December 1960) was an English sailor in the First World War, who is thought to have been one of the first people to benefit from advanced plastic surgery, namely a skin flap.

Early life

Yeo was bo ...

, who became one of the first men to receive facial reconstruction via plastic surgery

Plastic surgery is a surgical specialty involving the restoration, reconstruction or alteration of the human body. It can be divided into two main categories: reconstructive surgery and cosmetic surgery. Reconstructive surgery includes cranio ...

. Although she had been extensively damaged, ''Warspite'' could still raise steam and was ordered back to Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style subur ...

during the evening of 31 May by Rear-Admiral Hugh Evan-Thomas, commander of the 5th Battle Squadron. Whilst travelling across the North Sea the ship came under attack from a German U-boat

U-boats were naval submarines operated by Germany, particularly in the First and Second World Wars. Although at times they were efficient fleet weapons against enemy naval warships, they were most effectively used in an economic warfare ro ...

. The U-boat fired three torpedoes, all of which missed their target. ''Warspite'' later attempted to ram a surfaced U-boat. She signalled ahead for escorts and a squadron of torpedo boats came out to meet her. They were too slow to screen her effectively, but there were no more encounters with German vessels and she reached Rosyth safely on the morning of 1 June, where it took two months to repair the damage.

1916–1918

Upon the completion of her repairs, ''Warspite'' rejoined the 5th Battle Squadron. Further misfortune struck soon afterwards, when she collided with ''Valiant'' after a night-shooting exercise, necessitating more repair work at Rosyth. Captain Philpotts avoided reprimand on this occasion, but was moved to a shore-based job as Naval Assistant to the new First Sea Lord, Admiral Jellicoe. Ballantyne, 2013, pp. 65–66. He was replaced by Captain de Bartolome in December 1916. Watton, 1996, p. 8. In June 1917, ''Warspite'' collided with a destroyer, but did not require major repairs. Early in April 1918 she joined the Grand Fleet in a fruitless pursuit of the German High Seas Fleet which had been hunting for a convoy near Norway. In 1918, ''Warspite'' had to spend four months being repaired after a boiler room caught fire. CaptainHubert Lynes

Rear Admiral Hubert Lynes, (27 November 1874 – 10 November 1942) was a British admiral whose First World War service was notable for his direction of the Zeebrugge and Ostend raids designed to neutralise the German-held port of Bruges, whi ...

relieved Captain de Bartolome and on 21 November he took ''Warspite'' out to escort the German High Seas Fleet into internment at Scapa Flow following the signing of the Armistice.

Interbellum (1919–1939)

In 1919, ''Warspite'' joined the 2nd Battle Squadron, part of the newly formed Atlantic Fleet, and undertook regular spring cruises to the

In 1919, ''Warspite'' joined the 2nd Battle Squadron, part of the newly formed Atlantic Fleet, and undertook regular spring cruises to the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on th ...

. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 71. In 1924, she attended a Royal Fleet Review

A fleet review or naval review is an event where a gathering of ships from a particular navy is paraded and reviewed by an incumbent head of state and/or other official civilian and military dignitaries. A number of national navies continue to ...

at Spithead

Spithead is an area of the Solent and a roadstead off Gilkicker Point in Hampshire, England. It is protected from all winds except those from the southeast. It receives its name from the Spit, a sandbank stretching south from the Hampshir ...

, presided over by King George V

George V (George Frederick Ernest Albert; 3 June 1865 – 20 January 1936) was King of the United Kingdom and the British Dominions, and Emperor of India, from 6 May 1910 until his death in 1936.

Born during the reign of his grandmother Q ...

. Later in the year, ''Warspite'' underwent a partial modernisation that altered her superstructure by trunking her two funnels into one, enhanced her armour protection with torpedo bulges, swapped the high-angle 3-inch guns with new 4-inch anti-aircraft guns, and removed half her torpedo tubes. After the process finished in 1926, ''Warspite'' assumed the role of flagship of the Commander-in-Chief and Second-in-Command, Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

. In 1927, under the command of Captain James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval suppo ...

, she struck an uncharted rock in the Aegean and was ordered to return to Portsmouth for repairs. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 73. In 1930, ''Warspite'' rejoined the Atlantic Fleet. She was at sea when the crews of a number of warships mutinied at Invergordon in September 1931, although three sailors were later dismissed from the ship. In March 1933, she was rammed in fog by a Romanian passenger ship off Portugal, but did not require major repairs. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 79.

Between March 1934 and March 1937, she underwent a major reconstruction in Portsmouth at a cost of £2,363,000. This refit gave the Admiralty a virtually new warship, replacing internal machinery and significantly changing the battleship's appearance and capabilities.

* Propulsion: The reconstruction project replaced her propulsion machinery and installed six individual boiler rooms, with Admiralty three-drum boilers, in place of 24 Yarrow boilers; geared Parsons turbines were fitted in four new engine rooms and gearing rooms. This increased fuel efficiency, reducing fuel consumption from 41 tons per hour to 27 at almost 24 knots, and gave the warship 80,000 shp. The weight saving on the lighter machinery was used to increase protection and armament. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 80.

* Armour: of armour were added, improving coverage forward of A turret and the boiler rooms, as well as an increase to 5 inches over the magazines and 3.5 inches over the machinery. Better sub-division of the engineering rooms strengthened the hull and improved its integrity. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 81.

* Armament: The last pair of torpedo tubes were removed and the 6 inch guns had their protection reduced; four guns were removed from the fore and aft ends of the batteries. Eight 4 inch high-angle guns in four twin mountings and two octuple 2 pdr pom-poms were added to her anti-aircraft defences, as well as additional .50 calibre machine guns on two of the main turrets. The original 15-inch turrets were upgraded to increase the elevation of the guns by ten degrees (from 20° to 30°), providing a further 9,000 yards of range to a maximum of with a 6crh shell. The fire control was also modernised to include the HACS Mk III* AA fire control system and the Admiralty Fire Control Table Admiralty Fire Control Table in the transmitting station of .The Admiralty Fire Control Table (A.F.C.T.) was an electromechanical analogue computer fire-control system that calculated the correct elevation and deflection of the main armament of a R ...

Mk VII for surface fire control of the main armament.

Additionally, her superstructure was radically altered, allowing two cranes and an aircraft hangar to be fitted. This could carry four aircraft, but ''Warspite'' typically carried only two: from 1938 to 1941 these were

Additionally, her superstructure was radically altered, allowing two cranes and an aircraft hangar to be fitted. This could carry four aircraft, but ''Warspite'' typically carried only two: from 1938 to 1941 these were Swordfish

Swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as broadbills in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are a popular sport fish of the billfish category, though elusive. Swordfi ...

floatplanes and from 1942 to 1943 Walrus

The walrus (''Odobenus rosmarus'') is a large flippered marine mammal with a discontinuous distribution about the North Pole in the Arctic Ocean and subarctic seas of the Northern Hemisphere. The walrus is the only living species in the f ...

flying boats. Her tripod mast was removed and a distinctive armoured citadel built up to enclose the bridge and to provide space for her to operate as a flagship.

After completion of the refit, ''Warspite'' was recommissioned under the command of Captain Victor Crutchley. The intention was for her to become the flagship of Admiral Dudley Pound

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Alfred Dudley Pickman Rogers Pound, (29 August 1877 – 21 October 1943) was a British senior officer of the Royal Navy. He served in the First World War as a battleship commander, taking part in the Battle of Jutland ...

's Mediterranean Fleet

The British Mediterranean Fleet, also known as the Mediterranean Station, was a formation of the Royal Navy. The Fleet was one of the most prestigious commands in the navy for the majority of its history, defending the vital sea link between t ...

, but trials revealed problems with propulsion machinery and steering, a legacy of Jutland, which continued to beset ''Warspite'' and delayed her departure. These delays and the work required to rectify them also affected the crew's leave arrangements and led to some sailors airing their views in national newspapers, angering Pound. ''Warspite'' finally entered Grand Harbour

The Grand Harbour ( mt, il-Port il-Kbir; it, Porto Grande), also known as the Port of Valletta, is a natural harbour on the island of Malta. It has been substantially modified over the years with extensive docks ( Malta Dockyard), wharves, a ...

, in Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

, on 14 January 1938 and continued gunnery practice and training. At the end of one anti-aircraft exercise, a junior midshipman independently discharged his pom-pom

A pom-pom – also spelled pom-pon, pompom or pompon – is a decorative ball or tuft of fibrous material.

The term may refer to large tufts used by cheerleaders, or a small, tighter ball attached to the top of a hat, also known as a ...

gun after a towing aircraft flew low overhead to display its attached target to the crew. ''Warspite'' had turned towards Valletta

Valletta (, mt, il-Belt Valletta, ) is an administrative unit and capital of Malta. Located on the main island, between Marsamxett Harbour to the west and the Grand Harbour to the east, its population within administrative limits in 2014 was ...

on the exercise's conclusion and the shells hurtled towards the city. The shells landed harmlessly at a gunnery range where a platoon of the Green Howards

The Green Howards (Alexandra, Princess of Wales's Own Yorkshire Regiment), frequently known as the Yorkshire Regiment until the 1920s, was a line infantry regiment of the British Army, in the King's Division. Raised in 1688, it served under vario ...

was exercising. For the remainder of the year, she cruised the Aegean, Adriatic and Mediterranean seas, leading an intensive series of fleet exercises in August due to rising international tension. She undertook another cruise of the western Mediterranean in the spring of 1939. In June 1939, Vice Admiral Andrew Cunningham replaced Dudley Pound and took ''Warspite'' to Istanbul for talks with the Turkish government. When war was declared in September, the Mediterranean remained quiet and ''Warspite'' was recalled to join the Home Fleet

The Home Fleet was a fleet of the Royal Navy that operated from the United Kingdom's territorial waters from 1902 with intervals until 1967. In 1967, it was merged with the Mediterranean Fleet creating the new Western Fleet.

Before the Fi ...

following the loss of .

Second World War

Atlantic and Narvik (1939–1940)

''Warspite''s first task was to escort convoy HX 9 carrying fuel from Nova Scotia to the UK. She was diverted northwards in pursuit of the German battleships and which had sunk the

''Warspite''s first task was to escort convoy HX 9 carrying fuel from Nova Scotia to the UK. She was diverted northwards in pursuit of the German battleships and which had sunk the armed merchant cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

north of the Faroe Islands

The Faroe Islands ( ), or simply the Faroes ( fo, Føroyar ; da, Færøerne ), are a North Atlantic archipelago, island group and an autonomous territory of the Danish Realm, Kingdom of Denmark.

They are located north-northwest of Scotlan ...

, but failed to make contact.

In April 1940, ''Warspite'' had started her voyage back to the Mediterranean when the Germans invaded Denmark and Norway; she rejoined the Home Fleet on 10 April and proceeded towards Narvik

( se, Áhkanjárga) is the third-largest municipality in Nordland county, Norway, by population. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Narvik. Some of the notable villages in the municipality include Ankenesstranda, Ba ...

. On 13 April, Vice-Admiral William Whitworth William Whitworth may refer to:

* Sir William Whitworth (Royal Navy officer) (1884–1973)

* William Whitworth (journalist) (born 1937), American journalist and editor

* William Whitworth (politician) (1813–1886), British cotton manufacturer and ...

hoisted his flag in ''Warspite'' and led nine destroyers, three sweeping mines and six in an offensive role, into Ofotfjord to neutralise a force of eight German destroyers trapped near the port of Narvik

( se, Áhkanjárga) is the third-largest municipality in Nordland county, Norway, by population. The administrative centre of the municipality is the town of Narvik. Some of the notable villages in the municipality include Ankenesstranda, Ba ...

. Her Fairey Swordfish

The Fairey Swordfish is a biplane torpedo bomber, designed by the Fairey Aviation Company. Originating in the early 1930s, the Swordfish, nicknamed "Stringbag", was principally operated by the Fleet Air Arm of the Royal Navy. It was also use ...

float-plane sank the German U-boat with 250 lb bombs, becoming the first aircraft to sink a U-boat in the war. The Swordfish continued to provide accurate spotting reports during the early afternoon which were, arguably, more important to the course of the battle than the ''Warspite's'' guns. O'Hara, 2013, p. 54. The British destroyers soon opened fire on their counterparts, which had almost exhausted their fuel and ammunition following the First Naval Battle of Narvik. All were sunk during the action. ''Warspite'' destroyed the heavily damaged with broadsides, while damaging and . ''Diether von Roeder'' had to be scuttled while ''Erich Giese'' was sunk in conjunction with destroyers. The Second Naval Battle of Narvik was considered a success. She remained in Norwegian waters, participating in several shore bombardments around Narvik on 24

April, but these proved ineffectual and she returned to Scapa Flow prior to being redeployed to the Mediterranean on 28 April.

Mediterranean (1940–1941)

Calabria ''Warspite'' arrived safely in

''Warspite'' arrived safely in Alexandria

Alexandria ( or ; ar, ٱلْإِسْكَنْدَرِيَّةُ ; grc-gre, Αλεξάνδρεια, Alexándria) is the second largest city in Egypt, and the largest city on the Mediterranean coast. Founded in by Alexander the Great, Alexandr ...

before Italy entered the war on 10 June 1940. Admiral Cunningham took the fleet to sea on 7 July to meet two convoys travelling from Malta to Alexandria, knowing that part of the Italian fleet was escorting its own convoy to Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

. Cunningham hoped to draw the Regia Marina

The ''Regia Marina'' (; ) was the navy of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1861 to 1946. In 1946, with the birth of the Italian Republic (''Repubblica Italiana''), the ''Regia Marina'' changed its name to ''Marina Militare'' (" ...

into battle by sailing towards the "toe" of Italy to cut them off from their base at Taranto

Taranto (, also ; ; nap, label=Tarantino dialect, Tarantino, Tarde; Latin: Tarentum; Old Italian: ''Tarento''; Ancient Greek: Τάρᾱς) is a coastal city in Apulia, Southern Italy. It is the capital of the Province of Taranto, serving as an ...

. The two fleets eventually met 30 miles from Punta Stilo at the Battle of Calabria

The Battle of Calabria, known to the Italian Navy as the Battle of Punta Stilo, was a naval battle during the Battle of the Mediterranean in the Second World War. Ships of the Italian ''Regia Marina'' were opposed by vessels of the British Roya ...

on 9 July 1940. Initially, the Allied cruisers, armed with 6-inch guns, were outranged by the 8-inch guns of their heavier Italian counterparts and disengaged. Seeing that they were under pressure, Cunningham took ''Warspite'' ahead to assist his cruisers. The Italian cruisers turned away under a smoke screen while the battleships and closed on ''Warspite'' before ''Malaya'' and could catch up. Ballantyne, 2013, p. 110.

During the battle ''Warspite'' achieved one of the longest range gunnery hits from a moving ship to a moving target in history, hitting ''Giulio Cesare'' at a range of approximately , the other being a shot from Scharnhorst which hit at approximately the same distance in June 1940. The shell pierced ''Giulio Cesare's'' rear funnel and detonated inside it, blowing out a hole nearly across, while fragments started several fires and their smoke was drawn into the boiler rooms, forcing four boilers off-line as their operators could not breathe which reduced the ship's speed to . Uncertain how severe the damage was, Campioni ordered his battleships to turn away in the face of superior British numbers and they disengaged behind a smoke screen laid by Italian destroyers. The destroyers and cruisers on both sides continued shooting for half an hour but with ''Malaya'' and ''Royal Sovereign'' coming into range, the Italian fleet disengaged. Over 125 aircraft of the Regia Aeronautica

The Italian Royal Air Force (''Regia Aeronautica Italiana'') was the name of the air force of the Kingdom of Italy. It was established as a service independent of the Regio Esercito, Royal Italian Army from 1923 until 1946. In 1946, the mon ...

attacked the ships over the next three hours but caused no damage. ''Warspite'' returned to Alexandria on 13 July.

TarantoIn mid-August, she set out to bombard

Bardia

Bardia, also El Burdi or Barydiyah ( ar, البردية, lit=, translit=al-Bardiyya or ) is a Mediterranean seaport in the Butnan District of eastern Libya, located near the border with Egypt. It is also occasionally called ''Bórdi Slemán''.

...

and on 6 November she sailed from Alexandria to provide cover for the Battle of Taranto

The Battle of Taranto took place on the night of 11–12 November 1940 during the Second World War between British naval forces, under Admiral Andrew Cunningham, and Italian naval forces, under Admiral Inigo Campioni. The Royal Navy launched ...

, a torpedo-bomber attack on ships in Taranto harbour. As a result of this attack, ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' were able to bombard the Italian supply base in the Adriatic port of Vlorë

Vlorë ( , ; sq-definite, Vlora) is the third most populous city of the Republic of Albania and seat of Vlorë County and Vlorë Municipality. Located in southwestern Albania, Vlorë sprawls on the Bay of Vlorë and is surrounded by the foot ...

in mid-December. On 10 January 1941, ''Warspite'' was lightly damaged by a bomb while operating with Force A during Operation Excess

Operation Excess was a series of British supply convoys to Malta, Alexandria and Greece in January 1941. The operation encountered the first presence of ''Luftwaffe'' anti-shipping aircraft in the Mediterranean Sea. All the convoyed freighters re ...

.

MatapanGovernment Code and Cypher School

Government Communications Headquarters, commonly known as GCHQ, is an intelligence and security organisation responsible for providing signals intelligence (SIGINT) and information assurance (IA) to the government and armed forces of the Unit ...

at Bletchley Park

Bletchley Park is an English country house and estate in Bletchley, Milton Keynes (Buckinghamshire) that became the principal centre of Allied code-breaking during the Second World War. The mansion was constructed during the years following ...

, Admiral Cunningham took his fleet to sea on 27 March 1941, flying his flag on ''Warspite''. On 28 March, the British cruisers encountered the Italian fleet and were forced to turn away by the heavy guns of ''Vittorio Veneto''. To save his cruisers Cunningham ordered an air attack, prompting Iachino to retreat. Subsequent air attacks damaged the battleship and the cruiser , slowing the former and crippling the latter. ''Vittorio Veneto'' escaped to the west as dusk fell but the British pursued through the night, first detecting ''Pola'' on radar and then two of her sister ships. ''Warspite'', ''Valiant'' and ''Barham'' closed on the unsuspecting Italian ships and aided by searchlights, destroyed the heavy cruisers and and two destroyers at point blank range. ''Pola'' was also sunk once her crew had been taken off. Having established by aerial reconnaissance that the rest of the Italian fleet had escaped, ''Warspite'' returned to Alexandria on 29 March, surviving air attacks without suffering casualties.

The Battle of Cape Matapan

The Battle of Cape Matapan ( el, Ναυμαχία του Ταινάρου) was a naval battle during the Second World War between the Allies, represented by the navies of the United Kingdom and Australia, and the Royal Italian navy, from 27 ...

had a paralysing effect on the ''Regia Marina'', providing the Royal Navy with an opportunity to tighten its grip on the Mediterranean, as evidenced by the unequal Battle of the Tarigo Convoy near the Kerkennah Islands on 16 April. This was not enough and the success of the ''Afrika Korps

The Afrika Korps or German Africa Corps (, }; DAK) was the German expeditionary force in Africa during the North African Campaign of World War II. First sent as a holding force to shore up the Italian defense of its African colonies, the ...

'' in North Africa induced Churchill to order a desperate attack on Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

to block the Axis supply route by sinking a battleships in the harbour. Cunningham rejected this plan, but on 21 April he sailed with ''Warspite'' to bombard the harbour in company with and , the cruiser and several destroyers. The raid was ineffectual, partly because of poor visibility created by dust from an earlier RAF bombing raid; the fleet returned to Alexandria without damage. The futility of the mission and the exposure of his battleships led to a tense exchange of letters between Cunningham and Churchill.

CreteDuring the

Battle of Crete

The Battle of Crete (german: Luftlandeschlacht um Kreta, el, Μάχη της Κρήτης), codenamed Operation Mercury (german: Unternehmen Merkur), was a major Axis airborne and amphibious operation during World War II to capture the islan ...

, ''Warspite'' was used as a floating anti-aircraft battery and like many other ships, suffered severe damage from German air attacks on 22 May. A 500 lb bomb damaged her starboard 4-inch and 6-inch batteries, ripped open the ship's side and killed 38 men. The attack was carried out by ''Jagdgeschwader 77

''Jagdgeschwader'' 77 (JG 77) ''Herz As'' ("Ace of Hearts") was a Luftwaffe fighter wing during World War II. It served in all the German theaters of war, from Western Europe to the Eastern Front, and from the high north in Norway to the Mediterr ...

'' (JG 77—Fighter Wing 77). '' Oberleutnant'' Kurt Ubben, a future flying ace

A flying ace, fighter ace or air ace is a military aviator credited with shooting down five or more enemy aircraft during aerial combat. The exact number of aerial victories required to officially qualify as an ace is varied, but is usually co ...

with 110 enemy aircraft shot down, claimed a hit on the warship. She was able to make it back to port under her own steam, but the damage could not be repaired in Alexandria and it was decided that she would have to be sent to Bremerton on the west coast of the United States.

Repair and refit

In June 1941, ''Warspite'' departed Alexandria for the Bremerton Naval Shipyard in the United States, arriving there on 11 August, having travelled through the Suez Canal, across the Indian Ocean toCeylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, stopping at Manila

Manila ( , ; fil, Maynila, ), officially the City of Manila ( fil, Lungsod ng Maynila, ), is the capital city, capital of the Philippines, and its second-most populous city. It is Cities of the Philippines#Independent cities, highly urbanize ...

, then Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the ...

and finally Esquimalt

The Township of Esquimalt is a municipality at the southern tip of Vancouver Island, in British Columbia, Canada. It is bordered to the east by the provincial capital, Victoria, to the south by the Strait of Juan de Fuca, to the west by Esq ...

along the way. Repairs and modifications began in August, including the replacement of her deteriorated 15 in guns, the addition of more anti-aircraft weapons, improvements to the bridge, and new surface and anti-aircraft radar. ''Warspite'' was still at the shipyard when the Japanese Navy attacked Pearl Harbor

The attack on Pearl HarborAlso known as the Battle of Pearl Harbor was a surprise military strike by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service upon the United States against the naval base at Pearl Harbor in Honolulu, Territory of Hawaii, ...

and went on alert as she would have been one of the few ships in the harbour which could have provided anti-aircraft defence should the Japanese have struck east. She was recommissioned on 28 December and undertook sea trials near Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the city, up from 631,486 in 2016. Th ...

before sailing down the west coast of the U.S. and Mexico, crossing the equator and arriving in Sydney on 20 February 1942. She joined the Eastern Fleet

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

* Eastern Air ...

at Trincomalee

Trincomalee (; ta, திருகோணமலை, translit=Tirukōṇamalai; si, ත්රිකුණාමළය, translit= Trikuṇāmaḷaya), also known as Gokanna and Gokarna, is the administrative headquarters of the Trincomalee Dis ...

in March 1942.

Indian Ocean (1942–1943)

''Warspite'' joined the

''Warspite'' joined the Eastern Fleet

Eastern may refer to:

Transportation

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 1926 to 1991

* Eastern Air ...

as flagship of Admiral Sir James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville, (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing naval suppo ...

, who had commanded her in 1927. Initially, ''Warspite'' was based in Ceylon

Sri Lanka (, ; si, ශ්රී ලංකා, Śrī Laṅkā, translit-std=ISO (); ta, இலங்கை, Ilaṅkai, translit-std=ISO ()), formerly known as Ceylon and officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, is an ...

, forming a fast group with the aircraft carriers and , four cruisers and six destroyers. In March, Somerville received intelligence indicating the Japanese Fast Carrier Strike Force was heading towards the Indian Ocean and he relocated his base to Addu Atoll

Addu Atoll, also known as Seenu Atoll, is the southernmost atoll of the Maldives. Addu Atoll, together with Fuvahmulah, located 40 km north of Addu Atoll, extend the Maldives into the Southern Hemisphere. Addu Atoll is located 540 ...

in the Maldives

The Maldives, officially the Republic of Maldives,, ) and historically known as the Maldive Islands, is a country and archipelagic state in South Asia in the Indian Ocean. The Maldives is southwest of Sri Lanka and India, about from the A ...

.

Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo used five carriers and four battleships in the Indian Ocean raid

The Indian Ocean raid, also known as Operation C or Battle of Ceylon in Japanese, was a naval sortie carried out by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) from 31 March to 10 April 1942. Japanese aircraft carriers under Admiral Chūichi Nagum ...

a naval sortie into the Indian Ocean in April, attacking Allied shipping and bases in the Indian Ocean and the Bay of Bengal. Somerville's fleet was outnumbered and outclassed but he hoped to get close enough to launch a night-time torpedo bomber attack. ''Warspite''s fast group set sail to intercept on 4 April, detecting the Japanese attack on the cruisers and and later, a scouting aircraft from the cruiser . The fleets did not meet; ''Warspite'' withdrew to Addu Atoll and then to Kilindini

Kilindini Harbour is a large, natural deep-water inlet extending inland from Mombasa, Kenya. It is at its deepest center, although the controlling depth is the outer channel in the port approaches with a dredged depth of . It serves as the harbo ...

on the East African coast to protect the convoy routes. The Japanese believed that she was still in Sydney and ordered the Attack on Sydney Harbour

In late May and early June 1942, during World War II, Imperial Japanese Navy submarines made a series of attacks on the Australian cities of Sydney and Newcastle. On the night of 31 May – 1 June, three ''Ko-hyoteki''-class midget submarin ...

.

During May and June, ''Warspite'' continued to act as Somerville's flagship, carrying out exercises with other elements of the fleet and shore-based aircraft in Ceylon. In early June, she was sent to hunt the Japanese auxiliary cruisers and ''Hōkoku Maru

was an that served as an armed merchant cruiser in the Second World War. She was launched in 1939 and completed in 1940 for Osaka Shosen Lines.

In 1941 she was commissioned into the Imperial Japanese Navy. She served as a commerce raider and ...

'' near the Chagos Archipelago

The Chagos Archipelago () or Chagos Islands (formerly the Bassas de Chagas, and later the Oil Islands) is a group of seven atolls comprising more than 60 islands in the Indian Ocean about 500 kilometres (310 mi) south of the Maldives archi ...

but failed to find them.

In August, she was involved in Operation Stab

Operation Stab was a British naval deception during the Second World War to distract Japanese units for the forthcoming Guadalcanal Campaign, Guadalcanal campaign by the US armed forces.

Background

Admiral Ernest King, the head of the United ...

, a simulated attack on the Andaman Islands

The Andaman Islands () are an archipelago in the northeastern Indian Ocean about southwest off the coasts of Myanmar's Ayeyarwady Region. Together with the Nicobar Islands to their south, the Andamans serve as a maritime boundary between th ...

to distract the Japanese from U.S. preparations to attack Guadalcanal. She covered the landings at Mahajanga

Mahajanga (French: Majunga) is a city and an administrative district on the northwest coast of Madagascar. The city of Mahajanga (Mahajanga I) is the capital of the Boeny Region. The district (identical to the city) had a population of 220,629 ...

and Tamatave

Toamasina (), meaning "like salt" or "salty", unofficially and in French Tamatave, is the capital of the Atsinanana region on the east coast of Madagascar on the Indian Ocean. The city is the chief seaport of the country, situated northeast of its ...

during the Battle of Madagascar

The Battle of Madagascar (5 May – 6 November 1942) was a British campaign to capture the Vichy French-controlled island Madagascar during World War II. The seizure of the island by the British was to deny Madagascar's ports to the Imperial ...

an Allied invasion, in September. Her surface radar was replaced in Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

in October and Captain Packer, her former Assistant Gunnery Officer at Jutland, took command in January 1943. The remainder of ''Warspite''s cruise was uneventful. She underwent a short refit in Durban in April and returned to the UK in May 1943, having sailed approximately 160,000 miles since the war began.

Mediterranean (1943–1944)

She underwent a short refit in May in another attempt to fix her steering problem, then joinedForce H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place within the ...

at Scapa Flow, departing on 9 June for Gibraltar in company with five other battleships, two carriers and twelve destroyers. Assigned to Division 2 with ''Valiant'' and ''Formidable'', she returned to Alexandria on 5 July in preparation for Operation Husky

Operation or Operations may refer to:

Arts, entertainment and media

* ''Operation'' (game), a battery-operated board game that challenges dexterity

* Operation (music), a term used in musical set theory

* ''Operations'' (magazine), Multi-Ma ...

, the Allied invasion of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

. Division One and Two rendezvoused in the Gulf of Sirte

The Gulf of Sidra ( ar, خليج السدرة, Khalij as-Sidra, also known as the Gulf of Sirte ( ar, خليج سرت, Khalij Surt, is a body of water in the Mediterranean Sea on the northern coast of Libya, named after the oil port of Sidra or ...

on 9 July and covered the assembling convoys. ''Warspite'' was detached to refuel at Malta on 12 July, the first visit by a British battleship since December 1940. On 17 July, she bombarded Catania in support of an unsuccessful attack by the 8th Army, although her steering problem temporarily delayed her taking up position. She returned to Malta at high speed on 18 July, avoiding several air attacks during the night. On her return, Admiral Cunningham inadvertently coined the nickname by which she would be known thereafter when he signalled: "''Operation well carried out. There is no question when the old lady lifts her skirts she can run.''"

Between 2 and 3 September, ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' covered the

Between 2 and 3 September, ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' covered the assault

An assault is the act of committing physical harm or unwanted physical contact upon a person or, in some specific legal definitions, a threat or attempt to commit such an action. It is both a crime and a tort and, therefore, may result in cri ...

across the Straits of Messina

The Strait of Messina ( it, Stretto di Messina, Sicilian: Strittu di Missina) is a narrow strait between the eastern tip of Sicily ( Punta del Faro) and the western tip of Calabria (Punta Pezzo) in Southern Italy. It connects the Tyrrhenian ...

and bombarded the Italian coastal batteries near Reggio. Between 8 and 9 September, Force H, covering the landings at Salerno

Operation Avalanche was the codename for the Allied landings near the port of Salerno, executed on 9 September 1943, part of the Allied invasion of Italy during World War II. The Italians withdrew from the war the day before the invasion, bu ...

, came under fierce German air-attack and narrowly avoided being torpedoed. The resolve of the Italian Government had already been wavering by the time of the Allies victory in North Africa; the invasion of Sicily and aerial attacks on mainland Italy encouraged negotiations. They signed an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the ...

on 3 September, which took effect on 8 September. Anxious to ensure that the Germans did not acquire an additional 200 warships, the Allies insisted that the Regia Marina must sail for Allied ports. Three days later, ''Warspite'' met and led elements of the Italian Fleet, including ''Vittorio Veneto'' and ''Italia'', into internment at Malta. She repeated this process on 12 September for her opponent from the Battle of Calabria, ''Giulio Cesare''.

On 14 September, Force H was recalled to the UK to begin preparations for the invasion of France, but ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' were detached to provide support for Allied forces at

On 14 September, Force H was recalled to the UK to begin preparations for the invasion of France, but ''Warspite'' and ''Valiant'' were detached to provide support for Allied forces at Salerno

Salerno (, , ; nap, label= Salernitano, Saliernë, ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' in Campania (southwestern Italy) and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after ...

. Although the Italians had surrendered, the Germans had anticipated this and moved forces into position to block the Allied landings. The American forces near Battipaglia

Battipaglia () is a municipality ('' comune'') in the province of Salerno, Campania, south-western Italy.

Famed as a production place of buffalo mozzarella, Battipaglia is the economic hub of the Sele plain.

History

Formerly part of the an ...

were in a precarious situation following German counter-attacks. After arriving off Salerno on 15 September, ''Warspite'' bombarded an ammunition dump and other positions around Altavilla Silentina

Altavilla Silentina is a town and ''comune'' located in the province of Salerno, Campania, some 100 km south of Naples, Italy.

Geography

Altavilla Silentina is spread on two ridges of a hill. It is shielded on the northeastern side by the ...

, demoralising the German forces and providing time for Allied reinforcements to arrive. Overnight, the fleet came under intense air attack, but she was able to continue bombardment duties the next day. However, early in the afternoon she was attacked by a Luftwaffe squadron of Focke-Wulf Fw 190

The Focke-Wulf Fw 190, nicknamed ''Würger'' ("Shrike") is a German single-seat, single-engine fighter aircraft designed by Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf in the late 1930s and widely used during World War II. Along with its well-known counterpart, th ...

fighter bombers and then, from high altitude, by three Dornier Do 217

The Dornier Do 217 was a bomber used by the Nazi Germany, German ''Luftwaffe'' during World War II as a more powerful development of the Dornier Do 17, known as the ''Fliegender Bleistift'' (German: "flying pencil"). Designed in 1937 and 1938 as ...

bombers from KG 100

''Kampfgeschwader'' 100 (KG 100) was a ''Luftwaffe'' medium and heavy bomber wing of World War II and the first military aviation unit to use a precision-guided munition (the Fritz X anti-ship glide bomb) in combat to sink a warship (the Itali ...

armed with an early guided bomb, the Fritz X

Fritz X was the most common name for a German guided anti-ship glide bomb used during World War II. ''Fritz X'' was the world's first precision guided weapon deployed in combat and the first to sink a ship in combat. ''Fritz X'' was a nickname us ...

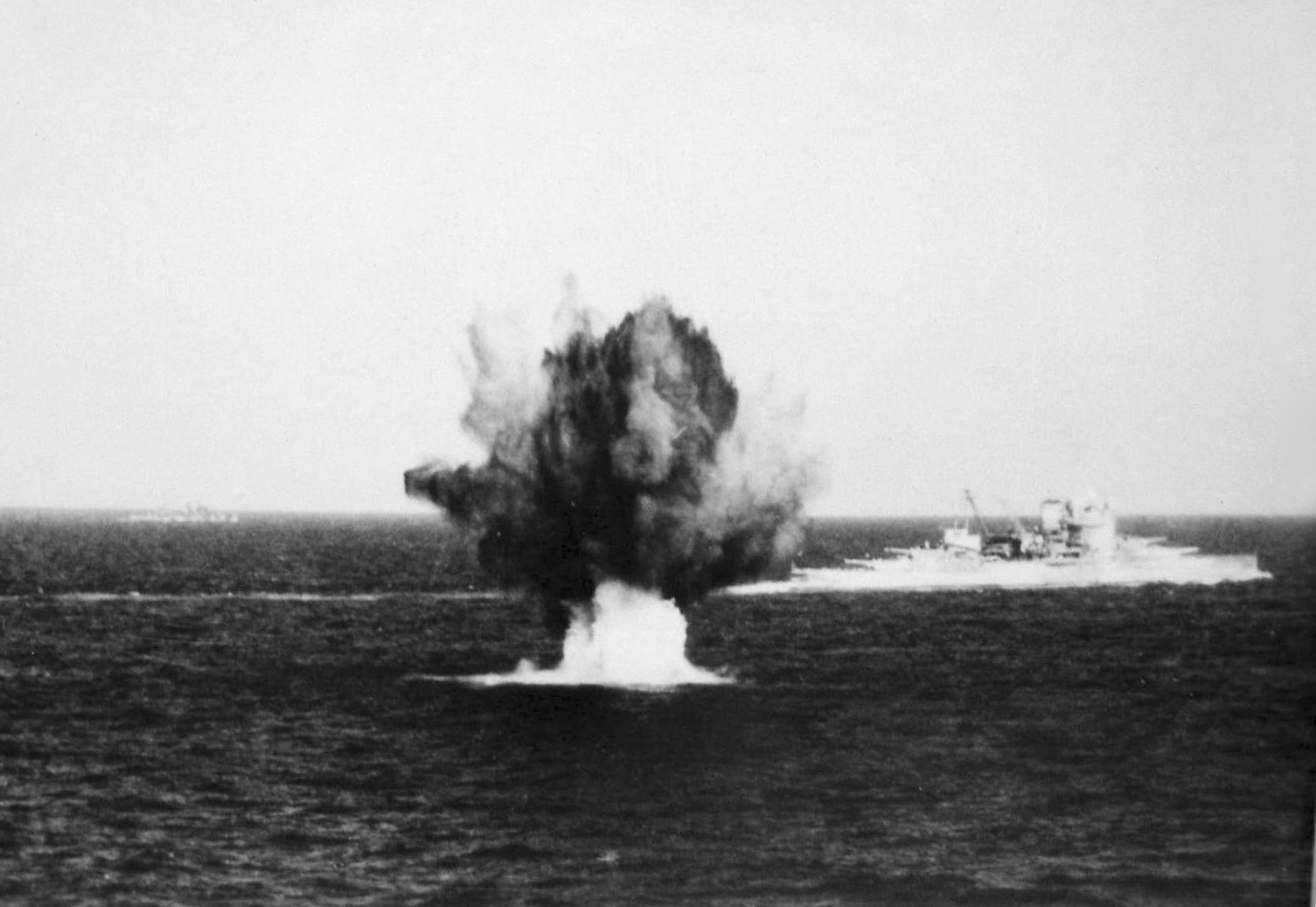

. She was hit directly once; a second near-miss ripped open the torpedo bulges while the third missed altogether. The bombs that did hit her struck near the funnel, cutting through her decks and making a 20-foot hole in the bottom of her hull, crippling her. Although the damage had been considerable, ''Warspite''s casualties amounted to only nine killed and fourteen wounded.

She was soon on the journey to Malta, escorted by the anti-aircraft cruiser and four destroyers, while being towed by United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

tugs. Towing a ship of ''Warspite''s dimensions proved difficult, and at one stage she broke all tow lines and drifted sideways through the Straits of Messina. She reached Malta on 19 September and undertook emergency repairs before being towed to Gibraltar on 12 November. ''Warspite'' returned to Britain in March 1944 to continue her repairs at Rosyth

Rosyth ( gd, Ros Fhìobh, "headland of Fife") is a town on the Firth of Forth, south of the centre of Dunfermline. According to the census of 2011, the town has a population of 13,440.

The new town was founded as a Garden city-style subur ...

. Captain Packer was mentioned in despatches for his actions bringing the ship to Malta, the second time he had limped into port on board a heavily damaged ''Warspite''.

North-Western Europe (1944–1945)

At Rosyth, ''Warspite''s 6-inch guns were removed and plated in, and a concrete caisson covered the hole left by the German missile. One of her boiler rooms and the X turret could not be repaired, remaining out of action for the remainder of her career. She left

At Rosyth, ''Warspite''s 6-inch guns were removed and plated in, and a concrete caisson covered the hole left by the German missile. One of her boiler rooms and the X turret could not be repaired, remaining out of action for the remainder of her career. She left Greenock

Greenock (; sco, Greenock; gd, Grianaig, ) is a town and administrative centre in the Inverclyde council area in Scotland, United Kingdom and a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, located in the west central Lowlands of ...

on 2 June 1944 with six 15-inch guns, eight 4-inch anti-aircraft guns and forty pom poms, joining Bombardment Force D of the Eastern Task Force of the Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

invasion fleet off Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymout ...

two days later.

At 0500 on 6 June 1944, ''Warspite'' was the first ship to open fire, Ballantyne, 2013, p. 188. bombarding the German battery at Villerville from a position 26,000 yards offshore, to support landings by the British 3rd Division on Sword Beach

Sword, commonly known as Sword Beach, was the code name given to one of the five main landing areas along the Normandy coast during the initial assault phase, Operation Neptune, of Operation Overlord. The Allied invasion of German-occupied Fra ...

. She continued bombardment duties on 7 June, but after firing over 300 shells she had to rearm and crossed the Channel to Portsmouth

Portsmouth ( ) is a port and city status in the United Kingdom, city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. The city of Portsmouth has been a Unitary authorities of England, unitary authority since 1 April 1997 and is admi ...

. She returned to Normandy on 9 June to support American forces at Utah Beach

Utah, commonly known as Utah Beach, was the code name for one of the five sectors of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on June 6, 1944 (D-Day), during World War II. The westernmost of the five code-named ...

and then, on 11 June, she took up position off Gold Beach

Gold, commonly known as Gold Beach, was the code name for one of the five areas of the Allied invasion of German-occupied France in the Normandy landings on 6 June 1944, during the Second World War. Gold, the central of the five areas, was l ...

to support the British 69th Infantry Brigade

The 69th Infantry Brigade was an infantry brigade of the British Army in the Second World War. It was a second-line Territorial Army formation, and fought in the Battle of France with the 23rd (Northumbrian) Division. The brigade was later part ...

near Cristot

Cristot is a commune in the Calvados department and Normandy region of north-western France.

Population

See also

*Communes of the Calvados department

The following is a list of the 528 communes of the Calvados department of France.

The ...

. On 12 June, she returned to Portsmouth to rearm, but her guns were worn out so she was ordered to sail to Rosyth via the Straits of Dover, the first British battleship to have done so since the war began. She evaded German coastal batteries, partly due to effective radar jamming, but hit a mine 28 miles off Harwich

Harwich is a town in Essex, England, and one of the Haven ports on the North Sea coast. It is in the Tendring district. Nearby places include Felixstowe to the north-east, Ipswich to the north-west, Colchester to the south-west and Clacton- ...

early on 13 June. Repairs to her propeller shafts and the replacement of the guns took until early August; she sailed to Scapa Flow to calibrate the new barrels with only three functional shafts, limiting her top speed to 15 knots, although by now the Admiralty considered her main role was that of a bombardment vessel.

''Warspite'' arrived off Ushant

Ushant (; br, Eusa, ; french: Ouessant, ) is a French island at the southwestern end of the English Channel which marks the westernmost point of metropolitan France. It belongs to Brittany and, in medieval terms, Léon. In lower tiers of gover ...

on 25 August 1944 and attacked the coastal batteries at Le Conquet

Le Conquet (; br, Konk-Leon) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in north-western France. This is the westernmost town of mainland France. Only three insular towns— Ouessant, Île-Molène and Ile de Sein—are further west ...

and Pointe Saint-Mathieu The pointe Saint-Mathieu (Lok Mazé in Breton) is a headland located near Le Conquet in the territory of the commune of Plougonvelin in France, flanked by 20m high cliffs.

Village

At present, there are only a few houses on the point, grouped aroun ...

during the Battle for Brest

The Battle for Brest was fought in August and September 1944 on the Western Front during World War II. Part of the overall Battle for Brittany and the Allied plan for the invasion of mainland Europe called for the capture of port facilities, ...

. The U.S. VIII Corps eventually captured "Festung Brest" on 19 September, but by then ''Warspite'' had moved on to the next port. In company with the monitor

Monitor or monitor may refer to:

Places

* Monitor, Alberta

* Monitor, Indiana, town in the United States

* Monitor, Kentucky

* Monitor, Oregon, unincorporated community in the United States

* Monitor, Washington

* Monitor, Logan County, West ...

, she carried out a preparatory bombardment of targets around Le Havre

Le Havre (, ; nrf, Lé Hâvre ) is a port city in the Seine-Maritime department in the Normandy region of northern France. It is situated on the right bank of the estuary of the river Seine on the Channel southwest of the Pays de Caux, ver ...

prior to Operation Astonia

Operation Astonia was the codename for an Allied attack on the German-held Channel port of Le Havre in France, during the Second World War. The city had been declared a ''Festung'' (fortress) by Hitler, to be held to the last man. Fought from 10 t ...