Connemara on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Connemara ( ; ) is a region on the

Connemara ( ; ) is a region on the

Retrieved 17 March 2020. During the centuries of

In 1843, Daniel O'Connell, the mastermind of the successful campaign for Catholic emancipation, held a Monster Meeting at Clifden, attended by a crowd reportedly numbering 100,000, before whom he spoke on

In 1843, Daniel O'Connell, the mastermind of the successful campaign for Catholic emancipation, held a Monster Meeting at Clifden, attended by a crowd reportedly numbering 100,000, before whom he spoke on

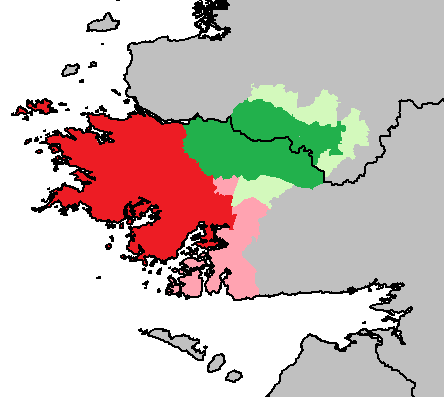

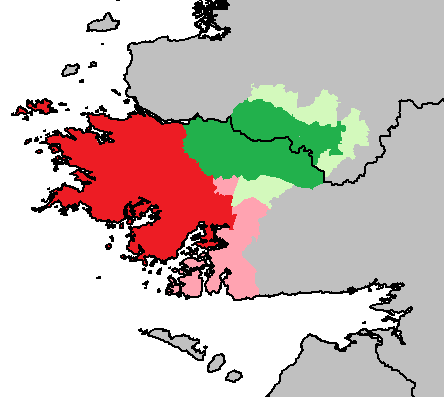

Connemara lies in the territory of , "West Connacht," within the portion of County Galway west of Lough Corrib, and was traditionally divided into North Connemara and South Connemara. The mountains of the Twelve Bens and the Owenglin River, which flows into the sea at / Clifden, marked the boundary between the two parts. Connemara is bounded on the west, south and north by the Atlantic Ocean. In at least some definitions, Connemara's land boundary with the rest of County Galway is marked by the Invermore River otherwise known as (which flows into the north of Kilkieran Bay), Loch Oorid (which lies a few kilometres west of Maam Cross) and the western spine of the Maumturks mountains. In the north of the mountains, the boundary meets the sea at Killary, a few kilometres west of Leenaun.

The coast of Connemara is made up of multiple peninsulas. The peninsula of (sometimes corrupted to ) in the south is the largest and contains the villages of Carna and Kilkieran. The peninsula of Errismore consists of the area west of the village of

Connemara lies in the territory of , "West Connacht," within the portion of County Galway west of Lough Corrib, and was traditionally divided into North Connemara and South Connemara. The mountains of the Twelve Bens and the Owenglin River, which flows into the sea at / Clifden, marked the boundary between the two parts. Connemara is bounded on the west, south and north by the Atlantic Ocean. In at least some definitions, Connemara's land boundary with the rest of County Galway is marked by the Invermore River otherwise known as (which flows into the north of Kilkieran Bay), Loch Oorid (which lies a few kilometres west of Maam Cross) and the western spine of the Maumturks mountains. In the north of the mountains, the boundary meets the sea at Killary, a few kilometres west of Leenaun.

The coast of Connemara is made up of multiple peninsulas. The peninsula of (sometimes corrupted to ) in the south is the largest and contains the villages of Carna and Kilkieran. The peninsula of Errismore consists of the area west of the village of

He spent most of his life in Connemara and is said to have been a heavy drinker. Micheál Mac Suibhne and his brother Toirdhealbhach are said to have moved to the

'' The Irish Post'' 14 March 2018.

Connemara after the Famine

at History Ireland

Bishop Ireland's Connemara Experiment:

'' Minnesota Historical Society''

Connemara News

– Useful source of information for everything related to this area of West Ireland: environment, people, traditions, events, books and movies. {{Coord, 53, 30, N, 9, 45, W, display=title Geography of County Galway Gaeltacht places in County Galway Mass rocks O'Flaherty dynasty Conmaicne Mara

Connemara ( ; ) is a region on the

Connemara ( ; ) is a region on the Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for se ...

coast of western County Galway

County Galway ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region, taking up the south of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. The county population was 276,451 at the 20 ...

, in the west of Ireland. The area has a strong association with traditional Irish culture

The culture of Ireland includes the Irish art, art, Music of Ireland, music, Irish dance, dance, Irish mythology, folklore, Irish clothing, traditional clothing, Irish language, language, Irish literature, literature, Irish cuisine, cuisine ...

and contains much of the Connacht Irish-speaking Gaeltacht

A ( , , ) is a district of Ireland, either individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The districts were first officially recognised ...

, which is a key part of the identity of the region and is the largest Gaeltacht in the country. Historically, Connemara was part of the territory of Iar Connacht (West Connacht). Geographically, it has many mountains (notably the Twelve Pins), peninsulas, coves, islands and small lakes. Connemara National Park is in the northwest. It is mostly rural and its largest settlement is Clifden.

Etymology

"Connemara" derives from the tribal name , which designated a branch of the , an early tribal grouping that had a number of branches located in different parts of . Since this particular branch of the lived by the sea, they became known as the (sea in Irish is ,genitive

In grammar, the genitive case ( abbreviated ) is the grammatical case that marks a word, usually a noun, as modifying another word, also usually a noun—thus indicating an attributive relationship of one noun to the other noun. A genitive can ...

, hence "of the sea").

Definition

One common definition of the area is that it consists of most of west Galway, that is to say the part of the county west of Lough Corrib and Galway city, contained by Killary Harbour, Galway Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Some more restrictive definitions of Connemara define it as the historical territory of , i.e. just the far northwest of County Galway, borderingCounty Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

. The name is also used to describe the (Irish-speaking areas) of western County Galway, though it is argued that this too is inaccurate as some of these areas lie outside of the traditional boundary of Connemara. There are arguments about where Connemara ends as it approaches Galway city, which is definitely not in Connemara – some argue for Barna, on the outskirts of Galway City, some for a line from Oughterard to Maam Cross, and then diagonally down to the coast, all within rural lands.

The wider area of what is today known as Connemara was previously a sovereign kingdom known as , under the kingship of the , until it became part of the English-administered Kingdom of Ireland

The Kingdom of Ireland (; , ) was a dependent territory of Kingdom of England, England and then of Kingdom of Great Britain, Great Britain from 1542 to the end of 1800. It was ruled by the monarchs of England and then List of British monarchs ...

in the 16th century.

History

The main town of Connemara is Clifden, which is surrounded by an area rich withmegalithic

A megalith is a large Rock (geology), stone that has been used to construct a prehistoric structure or monument, either alone or together with other stones. More than 35,000 megalithic structures have been identified across Europe, ranging ...

tombs.

The famous " Connemara Green marble" is found outcropping along a line between Streamstown and Lissoughter. It was a trade treasure used by the inhabitants in prehistoric times. It continues to be of great value today. It is available in large dimensional slabs suitable for buildings as well as for smaller pieces of jewellery.

Clan system

Before the Tudor and Cromwellian conquests, Connemara, like the rest ofGaelic Ireland

Gaelic Ireland () was the Gaelic political and social order, and associated culture, that existed in Ireland from the late Prehistory of Ireland, prehistoric era until the 17th century. It comprised the whole island before Anglo-Norman invasi ...

, was ruled by Irish clans whose Chiefs and their derbhfine were expected to follow the same code of honour also expected of Scottish clan chief

The Scottish Gaelic word means children. In early times, and possibly even today, Scottish clan members believed themselves to descend from a common ancestor, the founder of the clan, after whom the clan is named. The clan chief (''ceannard ci ...

s.

In his biography of Rob Roy MacGregor, W.H. Murray described the code of honour as follows, "The abiding principle is cast up from the records of detail: that right must be seen to be done, no man left destitute, the given word honoured, the strictest honour observed to all who have given implicit trust, and that a guest's confidence in his safety must never be betrayed by his host, or '' vice versa''. There was more of like kind, and each held as its kernel the simple ideal of trust honoured... Breaches of it were abhorred and damned... The ideal was applied 'with discretion'. Its interpretation went deeply into domestic life, but stayed shallow for war and politics."

The east of what is now Connemara was once called , and was ruled by Kings who claimed descent from the Delbhna and Dál gCais

The Dalcassians ( ) are a Gaels, Gaelic Irish clan, generally accepted by contemporary scholarship as being a branch of the Déisi Muman, that became very powerful in Ireland during the 10th century. Their genealogies claimed descent from Tál ...

of Thomond and kinship with King Brian Boru

Brian Boru (; modern ; 23 April 1014) was the High King of Ireland from 1002 to 1014. He ended the domination of the High King of Ireland, High Kingship of Ireland by the Uí Néill, and is likely responsible for ending Vikings, Viking invasio ...

. The Kings of Delbhna Tír Dhá Locha eventually took the title and surname Mac Con Raoi (since anglicised as Conroy or King).''Medieval Ireland: Territorial, Political and Economic Divisions'', Paul MacCotter, Four Courts Press, 2008, pp. 140–141.

The Chief of the Name of Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

Mac Con Raoi directly ruled as Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of Gnó Mhór, which was later divided into the civil parishes of Kilcummin and Killannin. As was common practice at the time, due to the power they wielded through their war galleys, the Chiefs of Clan Mac Conraoi also fulfilled their duty to be providers for their clan members by demanding and receiving black rent on pain of piracy

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

against ships who fished or traded within the Clan's territory. The Chiefs of Clan Mac Conraoi were accordingly numbered, along with the Chiefs of Clans O'Malley, O'Dowd, and O'Flaherty, among "the Sea Kings of Connacht". The nearby kingdom of Gnó Beag was ruled by the Chief of the Name of Clan Ó hÉanaí (usually anglicised as Heaney or Heeney).

The (Kealy) clan were the rulers of West Connemara. which is a transcription of: Like the Chiefs of Clan clan, the Chiefs of Clan (Conneely) also claimed descent from the .

During the early 13th century, but all four clans were displaced and subjugated by the Chiefs of Clan , who had been driven west from into by the Mac William Uachtar branch of the House of Burgh, during the Hiberno-Norman

Norman Irish or Hiberno-Normans (; ) is a modern term for the descendants of Norman settlers who arrived during the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland in the 12th century. Most came from England and Wales. They are distinguished from the native ...

invasion of .

According to Irish–American historian Bridget Connelly, "By the thirteenth century, the original inhabitants, the clans Conneely, Ó Cadhain, Ó Folan, and MacConroy, had been steadily driven westward from the Moycullen area to the seacoast between Moyrus and the Killaries. And by 1586, with the signing of the Articles of the Composition of Connacht that made Morrough O'Flaherty landlord over all in the name of Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

, the MacConneelys and Ó Folans had sunk beneath the list of chieftains whose names appeared on the document. The Articles deprived all the original Irish clan chieftains not only of their title but also all of the rents, dues, and tribal rights they had possessed under Irish law."

During the 16th century, but legendary local pirate queen Grace O'Malley

Gráinne O'Malley (, ; – ), also known as Grace O'Malley, was the head of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland, and the daughter of Eóghan Dubhdara Ó Máille.

Upon her father's death, she took over active leadership of the lords ...

is on record as having said, with regard to her followers, () ("Better a ship filled with MacConroy and MacAnally clansmen, than a ship filled with gold").Ordnance Survey Letters, Mayo, vol. II, cited in Anne Chambers (2003), ''The Pirate Queen'', but with spelling modernised.

Even though she has traditionally been viewed as a icon of Irish nationalism

Irish nationalism is a nationalist political movement which, in its broadest sense, asserts that the people of Ireland should govern Ireland as a sovereign state. Since the mid-19th century, Irish nationalism has largely taken the form of cult ...

, Grace O'Malley, in reality, sided with Queen Elizabeth I

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last and longest reigning monarch of the House of Tudor. Her eventful reign, and its effect on history ...

against Red Hugh O'Donnell and Aodh Mór Ó Néill during the Nine Years War, after which her known descendants became completely assimilated into the British upper class

The social structure of the United Kingdom has historically been highly influenced by the concept of social class, which continues to affect British society today. British society, like its European neighbours and most societies in world history, ...

. Even though O'Donnell and O'Neill were seeking primarily to end the religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic oppression of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within socie ...

of the Catholic Church in Ireland by the English Queen her officials, O'Malley almost certainly considered herself completely justified under the code of conduct in siding with the Crown of England against them.

The feud began in 1595, when O'Donnell re-instated the Chiefdom of Clan MacWilliam Íochdar of the completely Gaelicised

Gaelicisation, or Gaelicization, is the act or process of making something Gaels, Gaelic or gaining characteristics of the ''Gaels'', a sub-branch of Celticisation. The Gaels are an ethno-linguistic group, traditionally viewed as having spread fro ...

House of Burgh in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

, which had been abolished under the policy of surrender and regrant

During the Tudor conquest of Ireland (c.1540–1603), "surrender and regrant" was the legal mechanism by which Irish clans were to be converted from a power structure rooted in clan and kin loyalties, to a late-Feudalism, feudal system under t ...

. Instead, however, of allowing Clan a Burc to summon a gathering at which the nobles

Nobility is a social class found in many societies that have an aristocracy. It is normally appointed by and ranked immediately below royalty. Nobility has often been an estate of the realm with many exclusive functions and characteristics. T ...

and commons would debate and then choose one of the derbhfine of the last chief to lead them, O'Donnell instead chose to appoint his ally Tiobóid mac Walter Ciotach Búrca as Chief of the Name. By passing over the claim of her son Tiobóid na Long Búrca to the Chiefdom, O'Donnell made himself a permanent and very dangerous enemy out of his mother's former ally; Grace O'Malley. The latter was swift to retaliate by launching an English-backed regime change war, in which she fought against Hugh Roe in order to wrest the White Wand of the Chiefdom away from Tiobóid Mac Walter Ciotach and give it to her son. She was joined in this by the Clan O'Flaherty and the Irish clans of Connemara who followed their mantle.

Irish clan chief, historian, and refugee

A refugee, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), is a person "forced to flee their own country and seek safety in another country. They are unable to return to their own country because of feared persecution as ...

in Habsburg Spain

Habsburg Spain refers to Spain and the Hispanic Monarchy (political entity), Hispanic Monarchy, also known as the Rex Catholicissimus, Catholic Monarchy, in the period from 1516 to 1700 when it was ruled by kings from the House of Habsburg. In t ...

Philip O'Sullivan Beare later went on the record as a very harsh critic of Niall Garbh O'Donnell, Tiobóid na Long Búrca, Grace O'Malley

Gráinne O'Malley (, ; – ), also known as Grace O'Malley, was the head of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland, and the daughter of Eóghan Dubhdara Ó Máille.

Upon her father's death, she took over active leadership of the lords ...

, and other members of the Gaelic nobility of Ireland

This article concerns the Gaelic nobility of Ireland from ancient to modern times. It only partly overlaps with Chiefs of the Name because it excludes Scotland and other discussion. It is one of three groups of Irish nobility, the others bei ...

who similarly launched regime change wars within their clans with English backing. Having the benefit of hindsight regarding the long-term fallout from Tiobóid na Long Búrca's uprising against his Chief and many others like it nationwide, O'Sullivan Beare wrote, "The Catholics might have been able to find a remedy for all these evils, had it not been that they were destroyed from within by another and greater internal disease. For most of the families, clans, and towns of the Catholic chiefs, who took up arms in defense of the Catholic Faith, were divided into different factions, each having different leaders and following lords who were fighting for their estates and chieftaincies. The less powerful of them joined the English party in the hope of gaining the chieftainship of their clans, if the existing chieftains were removed from their position and property, and the English craftily held out that hope to them. Thus, short-sighted men, putting their private affairs before the public defence of their Holy Faith, turned their allies, followers, and towns from the Catholic chiefs and transferred to the English great resources, but in the end did not obtain what they wished for, but accomplished what they did not desire. For it was not they, but the English who got the properties of and rich patrimonies of the Catholic nobles and their kinsmen; and the Holy Faith of Christ Jesus, bereft of its defenders, lay open to the barbarous violence and lust of the heretics. There was one device by which the English were able to crush the forces of the Irish Chiefs, by promising their honours and revenues to such of their own kinsmen as would seduce their followers and allies from them, but when the war was over the English did not keep their promises."

Religious persecution

Before the Suppression of the Monasteries was spread to Connemara, theDominican Order

The Order of Preachers (, abbreviated OP), commonly known as the Dominican Order, is a Catholic Church, Catholic mendicant order of pontifical right that was founded in France by a Castilians, Castilian priest named Saint Dominic, Dominic de Gu ...

had a monastery about to the north of what is now Roundstone ().roundstonevillage.ieRetrieved 17 March 2020. During the centuries of

religious persecution

Religious persecution is the systematic oppression of an individual or a group of individuals as a response to their religion, religious beliefs or affiliations or their irreligion, lack thereof. The tendency of societies or groups within socie ...

of the Catholic Church in Ireland that began under Henry VIII

Henry VIII (28 June 149128 January 1547) was King of England from 22 April 1509 until his death in 1547. Henry is known for his Wives of Henry VIII, six marriages and his efforts to have his first marriage (to Catherine of Aragon) annulled. ...

and ended only with Catholic emancipation in 1829, the Irish people

The Irish ( or ''Na hÉireannaigh'') are an ethnic group and nation native to the island of Ireland, who share a common ancestry, history and Culture of Ireland, culture. There have been humans in Ireland for about 33,000 years, and it has be ...

, according to Marcus Tanner, clung to the Tridentine Mass

The Tridentine Mass, also known as the Extraordinary Form of the Roman Rite or ''usus antiquior'' (), Vetus Ordo or the Traditional Latin Mass (TLM) or the Traditional Rite, is the liturgy in the Roman Missal of the Catholic Church codified in ...

, " crossed themselves when they passed Protestant ministers on the road, had to be dragged into Protestant churches and put cotton wool in their ears rather than listen to Protestant sermons."

According to historian and folklorist

Folklore studies (also known as folkloristics, tradition studies or folk life studies in the UK) is the academic discipline devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with its synonyms, gained currency in the 1950s to distinguish the ac ...

Seumas MacManus, "Throughout these dreadful centuries, too, the hunted priest -- who in his youth had been smuggled to the Continent of Europe to receive his training -- tended the flame of faith. He lurked like a thief among the hills. On Sundays and Feast Days he celebrated Mass at a rock, on a remote mountainside, while the congregation knelt on the heather of the hillside, under the open heavens. While he said Mass, faithful sentries watched from all the nearby hilltops, to give timely warning of the approaching priest-hunter and his guard of British soldiers. But sometimes the troops came on them unawares, and the Mass Rock was bespattered with his blood, -- and men, women, and children caught in the crime of worshipping God among the rocks, were frequently slaughtered on the mountainside."

According to historian and folklorist Tony Nugent, several Mass rocks survive in Connemara from this era. There is one located along the boreen named ''Baile Eamoinn'' near Spiddal

Spiddal, also known as Spiddle (Irish language, Irish and official name: , , meaning 'the hospital'), is a village on the shore of Galway Bay in County Galway, Ireland. It is west of Galway city, on the R336 road (Ireland), R336 road. It is o ...

. Two others are located at Barr na Daoire and at Caorán Beag in Carraroe

Carraroe (in Irish language, Irish, and officially, , meaning 'the red quarter') is a village in Connemara, the coastal Irish-speaking region (Gaeltacht) of County Galway, Ireland. It is known for its traditional fishing boats, the Galway Hook ...

. A fourth, Cluain Duibh, is located near Moycullen at Clooniff. The cartographer Tim Robinson has written of a fifth Mass rock, located in the Townland of "An Tulaigh", which also includes two holy well

A holy well or sacred spring is a well, Spring (hydrosphere), spring or small pool of water revered either in a Christianity, Christian or Paganism, pagan context, sometimes both. The water of holy wells is often thought to have healing qualitie ...

s and, formerly, a Christian pilgrimage

Christianity has a strong tradition of pilgrimages, both to sites relevant to the New Testament narrative (especially in the Holy Land) and to sites associated with later saints or miracles.

History

Christian pilgrimages were first made to sit ...

chapel dedicated to St. Columkille, who is said in the oral tradition to have visited the region. The Mass rock was built from several of the many boulders scattered by glaciers around Lough Clurra and is named in Irish ''"Cloch an tSagairt"'' ("Stone of the Priest"), but which was formerly marked as " Druid's altar" and dolmen

A dolmen, () or portal tomb, is a type of single-chamber Megalith#Tombs, megalithic tomb, usually consisting of two or more upright megaliths supporting a large flat horizontal capstone or "table". Most date from the Late Neolithic period (4000 ...

on the old Ordnance Survey

The Ordnance Survey (OS) is the national mapping agency for Great Britain. The agency's name indicates its original military purpose (see Artillery, ordnance and surveying), which was to map Scotland in the wake of the Jacobite rising of ...

maps.

After taking the island in 1653, the New Model Army

The New Model Army or New Modelled Army was a standing army formed in 1645 by the Parliamentarians during the First English Civil War, then disbanded after the Stuart Restoration in 1660. It differed from other armies employed in the 1639 t ...

of Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English statesman, politician and soldier, widely regarded as one of the most important figures in British history. He came to prominence during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, initially ...

turned the nearby island of Inishbofin, County Galway, into a prison camp for Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' re ...

s arrested while exercising their religious ministry covertly in other parts of Ireland. Inishmore, in the nearby Aran Islands, was used for exactly the same purpose. The last priests held on both islands were finally released following the Stuart Restoration

The Stuart Restoration was the reinstatement in May 1660 of the Stuart monarchy in Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland, and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland. It replaced the Commonwealth of England, established in January 164 ...

in 1662.

One of the last Chiefs of Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

O'Flaherty and Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of Iar Connacht was the 17th-century historian Ruaidhrí Ó Flaithbheartaigh

Roderick O'Flaherty (; 1629–1718 or 1716) was an Irish historian.

Biography

He was born in County Galway and inherited Moycullen Castle and estate.

O'Flaherty was the last ''de jure'' Tigerna, Lord of Iar Connacht, and the last recognised C ...

, who lost the greater part of his ancestral lands during the Cromwellian confiscations of the 1650s.

After being dispossessed, Ó Flaithbheartaigh settled near Spiddal

Spiddal, also known as Spiddle (Irish language, Irish and official name: , , meaning 'the hospital'), is a village on the shore of Galway Bay in County Galway, Ireland. It is west of Galway city, on the R336 road (Ireland), R336 road. It is o ...

wrote a book of Irish history in Neo-Latin

Neo-LatinSidwell, Keith ''Classical Latin-Medieval Latin-Neo Latin'' in ; others, throughout. (also known as New Latin and Modern Latin) is the style of written Latin used in original literary, scholarly, and scientific works, first in Italy d ...

titled ''Ogygia'', which was published in 1685 as ''Ogygia: seu Rerum Hibernicarum Chronologia & etc.'', in 1793 it was translated into English by Rev. James Hely, as ''Ogygia, or a Chronological account of Irish Events (collected from Very Ancient Documents faithfully compared with each other & supported by the Genealogical & Chronological Aid of the Sacred and Profane Writings of the Globe)''. Ogygia

Ogygia (; , or ''Ōgygíā'' ) is an island mentioned in Homer's ''Odyssey'', Book V, as the home of the nymph Calypso (mythology), Calypso, the daughter of the Titan (mythology), Titan Atlas (mythology), Atlas. In Homer's ''Odyssey'', Calyps ...

, the island of Calypso in Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

's ''The Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

'', was used by Ó Flaithbheartaigh as a poetic allegory for Ireland. Drawing from numerous ancient documents, ''Ogygia'' traces Irish history back before Saint Patrick and into Pre-Christian Irish mythology

Irish mythology is the body of myths indigenous to the island of Ireland. It was originally Oral tradition, passed down orally in the Prehistoric Ireland, prehistoric era. In the History of Ireland (795–1169), early medieval era, myths were ...

.

Simultaneously, however, Máirtín Mór Ó Máille, who claimed descent from the derbhfine of the last Chief of the Name of the Clan

A clan is a group of people united by actual or perceived kinship

and descent. Even if lineage details are unknown, a clan may claim descent from a founding member or apical ancestor who serves as a symbol of the clan's unity. Many societie ...

O'Malley and Lord

Lord is an appellation for a person or deity who has authority, control, or power (social and political), power over others, acting as a master, chief, or ruler. The appellation can also denote certain persons who hold a title of the Peerage o ...

of Umhaill as well as kinship with the famous pirate

Piracy is an act of robbery or criminal violence by ship or boat-borne attackers upon another ship or a coastal area, typically with the goal of stealing cargo and valuable goods, or taking hostages. Those who conduct acts of piracy are call ...

queen Grace O'Malley

Gráinne O'Malley (, ; – ), also known as Grace O'Malley, was the head of the Ó Máille dynasty in the west of Ireland, and the daughter of Eóghan Dubhdara Ó Máille.

Upon her father's death, she took over active leadership of the lords ...

, ran much of Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

landlord Richard "Humanity Dick" Martin's estates from his residence at "Keeraun House" and the surrounding region, which are still known locally as "the demesne

A demesne ( ) or domain was all the land retained and managed by a lord of the manor under the feudal system for his own use, occupation, or support. This distinguished it from land subinfeudation, sub-enfeoffed by him to others as sub-tenants. ...

" (), as a "middleman" ().

From the rock known as "O'Malley's Seat () at the mouth of the creek known as ''An Dólain'' near the village of An Caorán Beag in Carraroe

Carraroe (in Irish language, Irish, and officially, , meaning 'the red quarter') is a village in Connemara, the coastal Irish-speaking region (Gaeltacht) of County Galway, Ireland. It is known for its traditional fishing boats, the Galway Hook ...

, Ó Máille also ran, with the enthusiastic collusion of his employer, one of the busiest smuggling operations in South Connemara and regularly unloaded cargoes smuggled in from Guernsey

Guernsey ( ; Guernésiais: ''Guernési''; ) is the second-largest island in the Channel Islands, located west of the Cotentin Peninsula, Normandy. It is the largest island in the Bailiwick of Guernsey, which includes five other inhabited isl ...

. Like many other members of the Gaelic nobility of Ireland

This article concerns the Gaelic nobility of Ireland from ancient to modern times. It only partly overlaps with Chiefs of the Name because it excludes Scotland and other discussion. It is one of three groups of Irish nobility, the others bei ...

before him, Ó Máille was a legendary figure even in his own lifetime, entertaining all guests with several barrels of wine and feasts of roasted sheep and cattle, which were always fully eaten before having to be salted.

This arrangement continued until around 1800. While hosting Rt.-Rev. Edmund Ffrench, the Dominican Warden of Galway and future Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

Bishop of Kilmacduagh and Kilfenora, however, Máirtín Mór Ó Máille presided over an accidental breach of hospitality. As Warden Ffrench's visit was on a Friday, the Friar's was only eating fish and seafood. When one of the household servants of Máirtín Mór accidentally poured a meat gravy upon his plate, the future Bishop understood that it was unintentional and graciously waved the plate away. The future Bishop's cousin, Thomas Ffrench, however, was less forgiving and demanded satisfaction. This resulted in a duel during which Máirtín Mór was mortally wounded.

Sir Richard Martin, who had not been in Connemara at the time, was shocked and angry to hear of his middleman's death, saying, "Ó Máille preferred a hole in his guts to one in his honour, but there wouldn't have been a hole in either if I'd been told of it!"

Meanwhile another branch of the Gaelic nobility, who claimed descent from the derbhfine of the last O'Flaherty Chiefs, similarly lived in a thatch

Thatching is the craft of building a roof with dry vegetation such as straw, Phragmites, water reed, Cyperaceae, sedge (''Cladium mariscus''), Juncus, rushes, Calluna, heather, or palm branches, layering the vegetation so as to shed water away fr ...

-covered long house at Renvyle and acted as both clan leaders and "middlemen" for the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

Blake family of Galway City, who were granted much of the region under the Acts of Settlement in 1677. This arrangement continued until 1811, when Henry Blake ended a 130-year-long tradition of his family acting as absentee landlord

In economics, an absentee landlord is a person who owns and rents out a profit-earning property, but does not live within the property's local economic region. The term "absentee ownership" was popularised by economist Thorstein Veblen's 1923 b ...

s and evicted 86-year-old Anthony O'Flaherty, his relatives, and his retainers. Henry Blake then demolished Anthony O'Flaherty's longhouse and built Renvyle House on the site.

Direct British rule

Even though Henry Blake later termed the eviction of Anthony O'Flaherty in ''Letters from the Irish Highlands'', as "the dawn of law in Cunnemara" ( sic), the Anglo-Irish Blake family, who remained in the region until the 1920s, are recalled in Connemara, as, "famously bad landlords" with an alleged sense of sexual entitlement regarding the female tenants on their estates and as enthusiastic supporters of the anti-Catholic activities of the local Irish Church Missions, which, "caused much unrest and bitterness". Local Irish folklore accordingly glorifies a local rapparee known as Scorach Ghlionnáin, who was allegedly born illegitimately in a seaside cave in the Townland of An Tulaigh. He is said to often and successfully have stolen from the Blake family and their land agents and given to the poor, until enlisting in theBritish Army

The British Army is the principal Army, land warfare force of the United Kingdom. the British Army comprises 73,847 regular full-time personnel, 4,127 Brigade of Gurkhas, Gurkhas, 25,742 Army Reserve (United Kingdom), volunteer reserve perso ...

and losing his life in the Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720–1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

. The Blake family are also said in the local oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

to have been permanently banished from the region by a curse put on them by a local Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' re ...

who dabbled in Pre-Christian sorcery. Elsewhere in Connemara, Anglo-Irish landlord John D'Arcy (1785-1839), who bankrupted both himself and his heirs to found the town of Clifden, is recalled much more fondly.

In 1843, Daniel O'Connell, the mastermind of the successful campaign for Catholic emancipation, held a Monster Meeting at Clifden, attended by a crowd reportedly numbering 100,000, before whom he spoke on

In 1843, Daniel O'Connell, the mastermind of the successful campaign for Catholic emancipation, held a Monster Meeting at Clifden, attended by a crowd reportedly numbering 100,000, before whom he spoke on repeal

A repeal (O.F. ''rapel'', modern ''rappel'', from ''rapeler'', ''rappeler'', revoke, ''re'' and ''appeler'', appeal) is the removal or reversal of a law. There are two basic types of repeal; a repeal with a re-enactment is used to replace the law ...

of the Act of Union.

Connemara was drastically depopulated during the Great Famine in the late 1840s, with the lands of the Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

Martin family being greatly affected and the bankrupted landlord being forced to auction off the estate in 1849:

The Sean nós song '' Johnny Seoighe'' is one of the few Irish songs from the era of the Great Famine that still survives. The events of the Great Irish Famine in Connemara have since inspired the recent Irish-language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenou ...

films '' Black '47'', directed by Lance Daly, and '' Arracht'', which was directed by Tomás Ó Súilleabháin.

The Irish Famine of 1879 similarly caused mass starvation, evictions, and violence in Connemara against the abuses of power by local Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

landlords, bailiffs, and the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

.

According to Tim Robinson, " Michael Davitt, founder of the Land League... visited An Cheathrú Rua n 1879and... found that the tenantry was reduced to eating the seed-potatoes on which the next seasons crop depended. In January 1880 after another tour of Connemara, he reported that the Poor Law Unions of the coastal areas were providing no outdoor relief (i.e. road-building schemes, etc.), and that the people faced starvation in the months before the summer. Not only was potato-blight prevalent, but it seems the kelp

Kelps are large brown algae or seaweeds that make up the order (biology), order Laminariales. There are about 30 different genus, genera. Despite its appearance and use of photosynthesis in chloroplasts, kelp is technically not a plant but a str ...

market had failed, and for most small tenants of the coastal areas it was the price they got for their kelp that paid the rent."

In response, Father Patrick Grealy, the Roman Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in common English usage ''priest'' re ...

assigned to Carna, selected ten, "very destitute but industrious and virtuous families", from his parish to emigrate to America and be settled upon frontier homesteads in Moonshine Township, near Graceville, Minnesota

Graceville is a city in Big Stone County, Minnesota, United States. The population was 529 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census.

History

Graceville was founded in the 1870s by a colony of Catholics and named for Thomas Grace (bishop o ...

, by Bishop John Ireland of the Roman Catholic Diocese of St. Paul.

In 1880 efforts by landlord Martin S. Kirwan to evict his starving tenants resulted in "The Battle of Carraroe" (), which Tim Robinson has dubbed, "the most dramatic event of the Land War in Connemara." During the famous battle, Mr. Fenton, the landlord's process server, arrived to serve evictions with the protection and support of an estimated 260 officers of the Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

. They were met by the violent resistance of an estimated 2000 members of the local population. Tim Robinson writes, "Local ''Seanchas'' has it that there were many unfamiliar faces in the crowd – the dead, come up from the Old graveyard at Barr an Doire to protect the homes of their descendants, it was said." () After escalating violence forced him to retreat to the RIC barracks before completing the third eviction, Mr. Fenton wrote a letter to the land agent at Roundstone (); announcing his refusal to serve more evictions.

According to historian Cormac Ó Comhraí, between the Land War and the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, politics in Connemara was largely dominated by the pro-Home Rule

Home rule is the government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governan ...

Irish Parliamentary Party and its ally, the United Irish League. At the same time, though, despite an almost complete absence of the Sinn Fein political party in Connemara, the militantly anti-monarchist Irish Republican Brotherhood had a number of active units throughout the region. Furthermore, many County Galway

County Galway ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region, taking up the south of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. The county population was 276,451 at the 20 ...

veterans of the subsequent Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

traced their belief in Irish republicanism

Irish republicanism () is the political movement for an Irish Republic, Irish republic, void of any British rule in Ireland, British rule. Throughout its centuries of existence, it has encompassed various tactics and identities, simultaneously ...

to a father or grandfather who had been in the IRB.

The first transatlantic flight, piloted by British aviators John Alcock and Arthur Brown, landed in a boggy area near Clifden in 1919.

War of Independence

At the beginning of theIrish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

, the IRA in Connemara had active service companies in Shanafaraghaun, Maam, Kilmilkin, Cornamona, Clonbur, Carraroe

Carraroe (in Irish language, Irish, and officially, , meaning 'the red quarter') is a village in Connemara, the coastal Irish-speaking region (Gaeltacht) of County Galway, Ireland. It is known for its traditional fishing boats, the Galway Hook ...

, Lettermore, Gorumna, Rosmuc, Letterfrack, and Renvyle. The Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

(RIC), on the other hand, was based at fortified barracks at Clifden, Letterfrack, Leenane, Clonbur, Rosmuc, and Maam.

IRA veteran Jack Feehan later recalled of the region at the outbreak of the conflict, "In South Connemara from Spiddal

Spiddal, also known as Spiddle (Irish language, Irish and official name: , , meaning 'the hospital'), is a village on the shore of Galway Bay in County Galway, Ireland. It is west of Galway city, on the R336 road (Ireland), R336 road. It is o ...

to Lettermullen the brewing (of poitín) was very strong and it went out as far as Carna. The people there were against the RIC more or less because they used to search for poitín, save in the Leenane area where the tourists came and Clifden were there were tourists and people who wanted to be friendly to law and good money."

According to both historian Kathleen Villiers-Tuthill and former West Connemara Brigade IRA O/C Peter J. McDonnell, one of the IRA's most valuable intelligence officers during the ensuing conflict was Letterfrack native Jack Conneely, who had served as a Sergeant in the Royal Engineers

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Following the Armistice, Conneely had returned to Connemara and accepted a position as the driver for the Leenane Hotel. Due to his war record, Conneely was trusted completely by oblivious Special Constables of the Black and Tans

The Black and Tans () were constables recruited into the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as reinforcements during the Irish War of Independence. Recruitment began in Great Britain in January 1920, and about 10,000 men enlisted during the conflic ...

. Crown security forces often requested rides from Conneely, who covertly used the opportunity to ask questions about secret military operations during the drive. On one occasion, two Special Constables accepted a ride to Leenane from Conneely without realizing that they were sitting the whole time next to crates filled with guns and ammunition. After dropping both men off, Conneely delivered the arms shipment to a safe house along Killary Harbour, where the arms were picked up and carried by sea to the IRA in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

.

But the national leadership of the Irish Volunteers was so dissatisfied by the inefficiency and internal squabbling of the IRA in Connemara that, in September 1920, Brigade Commandant Peter McDonnell was summoned to a secret meeting at Kilmilkin with IRA Chief of Staff Richard Mulcahy, who promoted MacDonnell on the spot to Officer Commanding

The commanding officer (CO) or commander, or sometimes, if the incumbent is a general officer, commanding general (CG), is the officer in command of a military unit. The commanding officer has ultimate authority over the unit, and is usually giv ...

of the West Connemara Brigade.

Burning of Clifden

The assassination of 14 British Intelligence officers from the Cairo Gang in Dublin on Bloody Sunday, was followed by the arrest andcourt-martial

A court-martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of members of the arme ...

of Connemara-native Thomas Whelan for high treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its d ...

and the first degree murder

Murder is the unlawful killing of another human without justification (jurisprudence), justification or valid excuse (legal), excuse committed with the necessary Intention (criminal law), intention as defined by the law in a specific jurisd ...

of Captain B.T. Baggelly at 119 Lower Baggot Street. Whelan, however, was a Volunteer in the IRA's Dublin Brigade but was not involved with Michael Collins' Squad

In military terminology, a squad is among the smallest of Military organization, military organizations and is led by a non-commissioned officer. NATO and United States, U.S. doctrine define a squad as an organization "larger than a fireteam, ...

, which had carried out the assassinations that morning. Therefore, in a break from typical IRA practice in such trials, Whelan recognized the court, pled not guilty, and accepted the services of a defense attorney, who introduced the sworn testimony of multiple alibi witnesses who stated that Whelan had attended a late morning Mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

and had been seen to receive Holy Communion in Ringsend on Bloody Sunday. Despite this testimony and the efforts of the Archbishop of Dublin and of Monsignor Joseph MacAlpine, the parish priest of St. Joseph's Roman Catholic Church in Clifden and Irish Parliamentary Party political boss of the surrounding region, to save his life out of a firm believe that he had not been involved in Captain Baggelly's assassination, Whelan was found guilty and subjected to execution by hanging on 14 March 1921.

In retaliation, Peter J. McDonnell and the West Connemara Brigade decided to follow the IRA's "Two for One" policy by assassinating two Royal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

officers in Whelan's birthplace of Clifden, which until then had been, according to Rosmuc IRA commander Colm Ó Gaora, ''"gach uile lá riamh dílis do dhlí Shasana"'', ("ever single day that ever was, loyal to England's law").

According to Peter McDonnell, the night of 15 March 1921 was selected, "to go into Clifden, get grub, and have a crack at the patrol." At the time, between 18 and 20 policemen were always stationed in the town. After finding the police had returned to barracks, the IRA withdrew temporarily, spent the night at, "the little lodge of Jim King near Kilcock" ( sic), and, on the evening of 16 March 1921, the patrol reentered Clifden from the south. A party of six IRA men then approached RIC Constables Charles Reynolds and Thomas Sweeney near "Eddie King's Pub". McDonnell later recalled, "I saw two RIC against Eddie King's window and they noticed us. One of them made a dive for his gun as I passed and we wheeled and opened up. They were shot." As both officers lay dying, the IRA men were seen to bend over them and remove their weapons and ammunition, before withdrawing from the scene with other RIC Constables in pursuit.

Peter Joseph McDonnell later recalled, "They had a rifle and a revolver, fifty rounds of ammo, and belts and pouches." Canon Joseph MacAlpine was immediately summoned and gave both Constables the Last Rites before their deaths.

Believing that an attack on their barracks was imminent, the Clifden RIC sent out a request for assistance over Clifden's Trans-Atlantic Marconi wireless station. In a British war crime that is still known as "The Burning of Clifden" and in response to the request, a trainload of "Special Constables" from the Black and Tans

The Black and Tans () were constables recruited into the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) as reinforcements during the Irish War of Independence. Recruitment began in Great Britain in January 1920, and about 10,000 men enlisted during the conflic ...

arrived via the Galway to Clifden railway in the early hours of St Patrick's Day, 17 March 1921. While making a half-hearted search for Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( ; ; ) is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active in both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The History of Sinn Féin, original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur Griffit ...

supporters, the Tans committed arson and burned down fourteen houses and businesses. Other Clifden residents later testified about being beaten and robbed at gunpoint and were granted compensation by the courts. John J. McDonnell, a decorated former sergeant major

Sergeant major is a senior Non-commissioned officer, non-commissioned Military rank, rank or appointment in many militaries around the world.

History

In 16th century Spain, the ("sergeant major") was a general officer. He commanded an army's ...

in the Connaught Rangers during World War I, was shot dead by security forces; most likely for the incorrigibly bad luck of having the same surname as the O.C. of the IRA West Connemara Brigade. Local businessman Peter Clancy was shot in the face and neck, but survived. Before leaving the town, British security forces left graffiti

Graffiti (singular ''graffiti'', or ''graffito'' only in graffiti archeology) is writing or drawings made on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view. Graffiti ranges from simple written "monikers" to elabor ...

outside Eddie King's pub, "Clifden will remember and so will the RIC", as well as, "Shoot another member of the RIC and up goes the town".

The Kilmilkin ambush

In the Irish folklore of Connemara, it was often said that one of last battles in a successful struggle for Irish independence would be fought in the hills near Kilmilkin. The IRA West Connemara Brigade's ambush of aRoyal Irish Constabulary

The Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC, ; simply called the Irish Constabulary 1836–67) was the police force in Ireland from 1822 until 1922, when all of the island was part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom. A sep ...

convoy on 21 April 1921 was later seen as the fulfilment of that legend.

Irish Civil War

The Truce

Shortly after the signing of theAnglo-Irish Treaty

The 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty (), commonly known in Ireland as The Treaty and officially the Articles of Agreement for a Treaty Between Great Britain and Ireland, was an agreement between the government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain an ...

on 6 December 1921, Connaught IRA commanders Peter J. McDonnell, Jack Feehan, and Michael Kilroy had a meeting with Michael Collins at the Gaelic League headquarters. McDonnell later recalled, "There was a conference on and he (Collins) had arranged to meet us. Jack had been in Dublin

Dublin is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. Situated on Dublin Bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, and is bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, pa ...

as he was the Divisional Quartermaster and he told us why we should accept the Treaty for we out of ammunition and the only choice we had was to accept the Treaty. All he wanted himself, Collins said, was to accept the Treaty for six months, get in arms, and then we could tell the British to go to blazes. We couldn't carry on the fight for we had no hope of carrying it out successfully. I represented West Connemara, was Brigade O/C and Deputy O/C of the Division; Jack Feehan was Divisional Quartermaster; Michael Kilroy, O/C Western Division there. We told Collins we didn't agree with what he said and he didn't say much."

In the lead up to the Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

, Pro-Treaty rallies were held in Clifden, Roundstone, and Cashel, while a massive anti-Treaty rally was addressed by Eamon de Valera at Market Square in Oughterard on 23 April 1922.

Following the anti-Treaty IRA's occupation of the Four Courts

The Four Courts () is Ireland's most prominent courts building, located on Inns Quay in Dublin. The Four Courts is the principal seat of the Supreme Court, the Court of Appeal, the High Court and the Dublin Circuit Court. Until 2010 the build ...

in Dublin on 13 April 1922, however, local anti-Treaty IRA units took action to raise money by simultaneous armed robbery of the post offices in Ballyconneely

Ballyconneely () is a village and small ribbon development in west Connemara, County Galway Ireland.

Name

19th century antiquarian John O'Donovan documents a number of variants of the village, including Ballyconneely, Baile 'ic Conghaile, Bal ...

, Clifden, and Cleggan on Good Friday

Good Friday, also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday, or Friday of the Passion of the Lord, is a solemn Christian holy day commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary (Golgotha). It is observed during ...

. Furthermore, after Anglo-Irish landlord Talbott Clifton fled the country following a gun battles against local anti-Treaty IRA members, his home at Kylemore House was requisitioned and barricaded against expected attack by soldiers from the newly founded Irish Army

The Irish Army () is the land component of the Defence Forces (Ireland), Defence Forces of Republic of Ireland, Ireland.The Defence Forces are made up of the Permanent Defence Forces – the standing branches – and the Reserve Defence Forces. ...

. Mark O'Malley later recalled that he deeply regretted that the anti-Treaty IRA never found Mr. Clifton's supply of guns and ammunition, which were widely believed to be hidden nearby.

Hostilities

Renvyle House was burned down by the Anti-Treaty IRA during theIrish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

, but later rebuilt by Oliver St John Gogarty and turned into a hotel.

Geography

Ballyconneely

Ballyconneely () is a village and small ribbon development in west Connemara, County Galway Ireland.

Name

19th century antiquarian John O'Donovan documents a number of variants of the village, including Ballyconneely, Baile 'ic Conghaile, Bal ...

. Errisbeg peninsula lies to the south of the village of Roundstone. The Errislannan peninsula lies just south of the town of Clifden. The peninsulas of Kingstown, Coolacloy, Aughrus, Cleggan and Renvyle are found in Connemara's north-west. Connemara includes numerous islands, the largest of which is Inis mór which is the biggest island, County Galway Inis mór; other islands include Omey Omey may refer to the following: France

* Omey (commune), a commune in north-eastern France.

Ireland

*Omey (civil parish), a civil parish in County Galway.

*Omey Island, an island in County Galway

Surname

* Tom Omey, retired Belgian athlete

{ ...

, Inishark, High Island, Friars Island, Feenish and Maínis.

The territory contains the civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

es of Moyrus, Ballynakill, Omey, Ballindoon and Inishbofin (the last parish was for a time part of the territory of the , the O Malley Lords of Umhaill, County Mayo), and the Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

parishes of Carna, Clifden (Omey and Ballindoon), Ballynakill, Kilcumin (Oughterard and Rosscahill), Roundstone and Inishbofin.

Irish language, literature, and folklore

The population of Connemara is 32,000. There are between 20,000–24,000 native Irish speakers in the region, making it the largest Irish-speaking . The Enumeration Districts with the most Irish speakers in all of Ireland, as a percentage of population, can be seen in the South Connemara area. Those of school age (5–19 years old) are the most likely to be identified as speakers. Writing in 1994, John Ardagh described "the Galway Gaeltacht" of South Connemara, as a region, "where narrow bumpy roads lead from one little whitewashed village to another, through a rough landscape of green hills, bogs, and little lakes, past a straggling coast of deep inlets and tiny rocky islands." Due the many close similarities between the landscape, language, history, and culture of WestCounty Galway

County Galway ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region, taking up the south of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. The county population was 276,451 at the 20 ...

with those of the Gàidhealtachd of Scotland

Scotland is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It contains nearly one-third of the United Kingdom's land area, consisting of the northern part of the island of Great Britain and more than 790 adjac ...

, the Connemara Gaeltacht

A ( , , ) is a district of Ireland, either individually or collectively, where the Irish government recognises that the Irish language is the predominant vernacular, or language of the home.

The districts were first officially recognised ...

during the Victorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the reign of Queen Victoria, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. Slightly different definitions are sometimes used. The era followed the ...

was often called "The Irish Highlands". Connemara has accordingly wielded an enormous influence upon Irish culture

The culture of Ireland includes the Irish art, art, Music of Ireland, music, Irish dance, dance, Irish mythology, folklore, Irish clothing, traditional clothing, Irish language, language, Irish literature, literature, Irish cuisine, cuisine ...

, literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, mythology

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

, and folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

.

Micheál Mac Suibhne (), a Connacht Irish bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is an oral repository and professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's a ...

mainly associated with Cleggan, remains a locally revered figure, due to his genius level contribution to oral poetry, Modern literature in Irish, and sean-nós singing in Connacht Irish. Mac Suibhne was born near the ruined Abbey

An abbey is a type of monastery used by members of a religious order under the governance of an abbot or abbess. Abbeys provide a complex of buildings and land for religious activities, work, and housing of Christians, Christian monks and nun ...

of Cong, then part of County Galway

County Galway ( ; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. It is in the Northern and Western Region, taking up the south of the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht. The county population was 276,451 at the 20 ...

, but now in County Mayo

County Mayo (; ) is a Counties of Ireland, county in Republic of Ireland, Ireland. In the West Region, Ireland, West of Ireland, in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Connacht, it is named after the village of Mayo, County Mayo, Mayo, now ge ...

. The names of his parents are not recorded, but his ancestors are said to have migrated from Ulster

Ulster (; or ; or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional or historic provinces of Ireland, Irish provinces. It is made up of nine Counties of Ireland, counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United Kingdom); t ...

as refugees from the Cromwellian conquest of Ireland.Dictionary of Irish Biography: Micheál Mac SuibhneHe spent most of his life in Connemara and is said to have been a heavy drinker. Micheál Mac Suibhne and his brother Toirdhealbhach are said to have moved to the

civil parish

In England, a civil parish is a type of administrative parish used for local government. It is a territorial designation which is the lowest tier of local government. Civil parishes can trace their origin to the ancient system of parishes, w ...

of Ballinakill, between Letterfrack and Clifden, where the poet was employed as a blacksmith

A blacksmith is a metalsmith who creates objects primarily from wrought iron or steel, but sometimes from #Other metals, other metals, by forging the metal, using tools to hammer, bend, and cut (cf. tinsmith). Blacksmiths produce objects such ...

by an Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the State rel ...

landlord named Steward. It is not known whether Mac Suibhne ever married, but he is believed to have died in poverty at Fahy, near Clifden, around the year 1820. His burial place, however, remains unknown.

In 1846, James Hardiman wrote of Micheál Mac Suibhne: "By the English-speaking portion of the people, Mac Sweeney was the 'Bard of the West.' He composed, in his native language, several poems and songs of considerable merit; which have become such favourites, that there are few who cannot repeat some of them from memory. Many of these have been collected by the Editor; and if space shall permit, one or more of the most popular will be inserted in the Additional Notes, as a specimen of modern Irish versification, and of those compositions which afford so much social pleasure to the good people of Iar-Connacht." In his "Additional Notes to ''Iar or West Connacht''" (1846), Hardiman published the full texts of '' Abhrán an Phúca'', the '' Banais Pheigi Ní Eaghra'' (commonly known under the English title "The Connemara Wedding"), and '' Eóghain Cóir'' (lit. "Honest Owen"), a mock-lament over the recent death of a notoriously corrupt and widely disliked land agent. Following the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

and Irish Civil War

The Irish Civil War (; 28 June 1922 – 24 May 1923) was a conflict that followed the Irish War of Independence and accompanied the establishment of the Irish Free State, an entity independent from the United Kingdom but within the British Emp ...

, Professor Tomás Ó Máille collected from the local oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another.Jan Vansina, Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (19 ...

, edited, and published all of Micheál Mac Suibhne's poems in 1934

Events

January–February

* January 1 – The International Telecommunication Union, a specialist agency of the League of Nations, is established.

* January 15 – The 8.0 1934 Nepal–Bihar earthquake, Nepal–Bihar earthquake strik ...

.

After emigrating from Connemara to the United States during the 1860s, Bríd Ní Mháille, a Bard

In Celtic cultures, a bard is an oral repository and professional story teller, verse-maker, music composer, oral historian and genealogist, employed by a patron (such as a monarch or chieftain) to commemorate one or more of the patron's a ...

in the Irish language outside Ireland and sean-nós singer from the village of Trá Bhán, Isle of Garmna, composed the '' caoine'' '' Amhrán na Trá Báine''. The song is about the drowning of her three brothers after their '' currach'' was rammed and sunk while they were out at sea. Ní Mháille's lament for her brothers was first performed at a ceilidh in South Boston, Massachusetts

South Boston (colloquially known as Southie) is a densely populated neighborhood of Boston, Massachusetts, United States, located south and east of the Fort Point Channel and abutting Dorchester Bay (Boston Harbor), Dorchester Bay. It has under ...

before being brought back to Connemara, where it is considered an ''Amhrán Mór'' ("Big Song") and remains a very popular song among both performers and fans of both sean-nós singing and Irish traditional music.

During the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival () was the late-nineteenth-century national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including folklore, mythology, sports, music, arts, etc.). Irish had diminished as a sp ...

, Irish teacher and nationalist Patrick Pearse, who would go on to lead the 1916 Easter Rising

The Easter Rising (), also known as the Easter Rebellion, was an armed insurrection in Ireland during Easter Week in April 1916. The Rising was launched by Irish republicans against British rule in Ireland with the aim of establishing an ind ...

before being executed by firing squad

Execution by firing squad, in the past sometimes called fusillading (from the French , rifle), is a method of capital punishment, particularly common in the military and in times of war. Some reasons for its use are that firearms are usually re ...

, owned a cottage at Rosmuc, where he spent his summers learning the Irish language

Irish (Standard Irish: ), also known as Irish Gaelic or simply Gaelic ( ), is a Celtic language of the Indo-European language family. It is a member of the Goidelic languages of the Insular Celtic sub branch of the family and is indigenous ...

and writing. According to '' Innti'' poet and literary critic

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature' ...

Louis de Paor, despite Pearse's enthusiasm for the '' Conamara Theas'' dialect of Connacht Irish spoken around his summer cottage, he chose to follow the usual practice of the Gaelic revival

The Gaelic revival () was the late-nineteenth-century national revival of interest in the Irish language (also known as Gaelic) and Irish Gaelic culture (including folklore, mythology, sports, music, arts, etc.). Irish had diminished as a sp ...

by writing in Munster Irish, which was considered less Anglicized

Anglicisation or anglicization is a form of cultural assimilation whereby something non-English becomes assimilated into or influenced by the culture of England. It can be sociocultural, in which a non-English place adopts the English language ...

than other Irish dialects. At the same time, however, Pearse's reading of the radically experimental poetry of Walt Whitman and of the French Symbolists led him to introduce Modernist poetry into the Irish language. As a literary critic

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature' ...

, Pearse also left behind a very detailed blueprint for the decolonization

Decolonization is the undoing of colonialism, the latter being the process whereby Imperialism, imperial nations establish and dominate foreign territories, often overseas. The meanings and applications of the term are disputed. Some scholar ...

of Irish literature, particularly in the Irish language.

During the aftermath of the Irish War of Independence

The Irish War of Independence (), also known as the Anglo-Irish War, was a guerrilla war fought in Ireland from 1919 to 1921 between the Irish Republican Army (1919–1922), Irish Republican Army (IRA, the army of the Irish Republic) and Unite ...

and the Civil War

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, Connemara was a major center for the work of the Irish Folklore Commission in recording Ireland's endangered folklore

Folklore is the body of expressive culture shared by a particular group of people, culture or subculture. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, myths, legends, proverbs, Poetry, poems, jokes, and other oral traditions. This also ...

, mythology

Myth is a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society. For scholars, this is very different from the vernacular usage of the term "myth" that refers to a belief that is not true. Instead, the ...

, and oral literature

Oral literature, orature, or folk literature is a genre of literature that is spoken or sung in contrast to that which is written, though much oral literature has been transcribed. There is no standard definition, as anthropologists have used v ...