Ascospore on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

In

Ascospores are the defining sexual spores of the division

Ascospores are the defining sexual spores of the division

In many species, the chitin is quickly chemically modified ( deacetylated) into

In many species, the chitin is quickly chemically modified ( deacetylated) into

Ascospore shapes range from simple spheres and ovals to more elaborate forms—such as elongated, hat-shaped (''galeate''), or constricted (''isthmoid'') types. Spore size is also variable; most fall between 5–50

Ascospore shapes range from simple spheres and ovals to more elaborate forms—such as elongated, hat-shaped (''galeate''), or constricted (''isthmoid'') types. Spore size is also variable; most fall between 5–50

Asci shed their spores in two contrasting ways. In many lichens, yeasts and other fungi with prototunicate asci, the enclosing wall is so thin that once spores are mature it simply dissolves or ruptures. Autolytic enzymes—

Asci shed their spores in two contrasting ways. In many lichens, yeasts and other fungi with prototunicate asci, the enclosing wall is so thin that once spores are mature it simply dissolves or ruptures. Autolytic enzymes—

After discharge many ascospores will not germinate straight away, instead passing through a brief after-ripening or a longer dormancy whose length and triggers vary widely. Some lichens ('' Chaenotheca'', '' Cladonia'') shed spores that germinate within hours on a damp surface, oversized muriform spores of '' Ocellularia subpraestans'' start within minutes of release, whereas other taxa remain inert for months until seasonal cues arrive. Field trials show that crustose tropical lichens achieve the highest germination percentages, whereas

After discharge many ascospores will not germinate straight away, instead passing through a brief after-ripening or a longer dormancy whose length and triggers vary widely. Some lichens ('' Chaenotheca'', '' Cladonia'') shed spores that germinate within hours on a damp surface, oversized muriform spores of '' Ocellularia subpraestans'' start within minutes of release, whereas other taxa remain inert for months until seasonal cues arrive. Field trials show that crustose tropical lichens achieve the highest germination percentages, whereas

Mobility takes several forms. Many filamentous ascomycetes hurl spores clear of the substrate; dung dwellers such as '' Podospora'' and '' Triangularia'' regularly shoot them tens of centimetres beyond the manure pile so grazing animals carry the fungus farther. Subterranean truffles invert the strategy: their fragrant ascocarps entice mammals whose chewing ruptures the asci, and the thick-walled spores pass intact through the gut to be deposited in new territory. On bare rock faces lichens release showers of minute, colourless spores; sheer numbers compensate for the added requirement of meeting a suitable photobiont before a new thallus can form.

Dormancy allows the same spores to bridge seasons or catastrophes. In apple orchards, ''

Mobility takes several forms. Many filamentous ascomycetes hurl spores clear of the substrate; dung dwellers such as '' Podospora'' and '' Triangularia'' regularly shoot them tens of centimetres beyond the manure pile so grazing animals carry the fungus farther. Subterranean truffles invert the strategy: their fragrant ascocarps entice mammals whose chewing ruptures the asci, and the thick-walled spores pass intact through the gut to be deposited in new territory. On bare rock faces lichens release showers of minute, colourless spores; sheer numbers compensate for the added requirement of meeting a suitable photobiont before a new thallus can form.

Dormancy allows the same spores to bridge seasons or catastrophes. In apple orchards, ''

Ascomycota—the largest fungal division—shows wide latitude in how many spores a single ascus produces. Eight remains the default (one meiosis followed by one mitosis), yet Saccharomycete yeasts routinely stop at four, while filamentous genera such as '' Gymnoascus'' and '' Basipetospora'' add further post-meiotic divisions to yield 16, 32 or more propagules. Some powdery mildews ('' Erysiphe'') and most Laboulbeniales mature only two spores, and a handful of taxa—including '' Monosporascus'' and '' Cephalotheca''—make just one. At the opposite extreme, repeated budding inside the ascus turns '' Taphrina'' into a miniature sporangium packed with dozens of secondary spores, and individual asci of '' Ascodesmis'' can shelter several thousand minute propagules. Other outliers depart even further from the textbook pattern: the cucurbit pathogen '' Monosporascus cannonballus'' matures a single globose ascospore per ascus, whereas in forest-pathogenic '' Tympanis'' species each primary ascospore buds internally to fill the ascus with hundreds of

Ascomycota—the largest fungal division—shows wide latitude in how many spores a single ascus produces. Eight remains the default (one meiosis followed by one mitosis), yet Saccharomycete yeasts routinely stop at four, while filamentous genera such as '' Gymnoascus'' and '' Basipetospora'' add further post-meiotic divisions to yield 16, 32 or more propagules. Some powdery mildews ('' Erysiphe'') and most Laboulbeniales mature only two spores, and a handful of taxa—including '' Monosporascus'' and '' Cephalotheca''—make just one. At the opposite extreme, repeated budding inside the ascus turns '' Taphrina'' into a miniature sporangium packed with dozens of secondary spores, and individual asci of '' Ascodesmis'' can shelter several thousand minute propagules. Other outliers depart even further from the textbook pattern: the cucurbit pathogen '' Monosporascus cannonballus'' matures a single globose ascospore per ascus, whereas in forest-pathogenic '' Tympanis'' species each primary ascospore buds internally to fill the ascus with hundreds of

Sexual spores initiate many crop epidemics. In cereals, perithecia of ''

Sexual spores initiate many crop epidemics. In cereals, perithecia of ''

Another burgeoning area is the effect of

Another burgeoning area is the effect of

fungi

A fungus (: fungi , , , or ; or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and mold (fungus), molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as one ...

, an ascospore is the sexual spore

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual reproduction, sexual (in fungi) or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for biological dispersal, dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores fo ...

formed inside an ascus

An ascus (; : asci) is the sexual spore-bearing cell produced in ascomycete fungi. Each ascus usually contains eight ascospores (or octad), produced by meiosis followed, in most species, by a mitotic cell division. However, asci in some gen ...

—the sac-like cell that defines the division Ascomycota

Ascomycota is a phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, forms the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi or ascomycetes. It is the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species. The def ...

, the largest and most diverse division of fungi. After two parental nuclei fuse, the ascus undergoes meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

(halving of genetic material) followed by a mitosis

Mitosis () is a part of the cell cycle in eukaryote, eukaryotic cells in which replicated chromosomes are separated into two new Cell nucleus, nuclei. Cell division by mitosis is an equational division which gives rise to genetically identic ...

(cell division), ordinarily producing eight genetically distinct haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell (biology), cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for Autosome, autosomal and Pseudoautosomal region, pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the num ...

spores; most yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

s stop at four ascospores, whereas some mould

A mold () or mould () is one of the structures that certain fungi can form. The dust-like, colored appearance of molds is due to the formation of spores containing fungal secondary metabolites. The spores are the dispersal units of the fungi ...

s carry out extra post-meiotic divisions to yield dozens. Many asci build internal pressure

Internal pressure is a measure of how the internal energy of a system changes when it expands or contracts at constant temperature. It has the same dimensions as pressure, the SI unit of which is the pascal.

Internal pressure is usually given the ...

and shoot their spores clear of the calm thin layer of still air enveloping the fruit body, whereas subterranean truffle

A truffle is the Sporocarp (fungi), fruiting body of a subterranean ascomycete fungus, one of the species of the genus ''Tuber (fungus), Tuber''. More than one hundred other genera of fungi are classified as truffles including ''Geopora'', ''P ...

s depend on animals for dispersal.

Development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development (music), the process by which thematic material is reshaped

* Photographic development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

* Development hell, when a proje ...

shapes both form and endurance of ascospores. A hook-shaped crozier

A crozier or crosier (also known as a paterissa, pastoral staff, or bishop's staff) is a stylized staff that is a symbol of the governing office of a bishop or abbot and is carried by high-ranking prelates of Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholi ...

aligns the paired nuclei; a double-membrane

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

system then parcels each daughter nucleus, and successive wall layers of β-glucan

Beta-glucans, β-glucans comprise a group of β-D-glucose polysaccharides (glucans) naturally occurring in the cell walls of cereals, bacteria, and Fungus, fungi, with significantly differing Physical chemistry, physicochemical properties depen ...

, chitosan

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide composed of randomly distributed β-(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine (deacetylated unit) and ''N''-acetyl-D-glucosamine (acetylated unit). It is made by treating the chitin shells of shrimp and other crusta ...

and lineage-specific armour envelop the incipient spores. The finished walls—smooth, ridged, spiny or gelatinous, and coloured from hyaline

A hyaline substance is one with a glassy appearance. The word is derived from , and .

Histopathology

Hyaline cartilage is named after its glassy appearance on fresh gross pathology. On light microscopy of H&E stained slides, the extracellula ...

to jet-black—let certain ascospores survive pasteurisation

In food processing, pasteurization ( also pasteurisation) is a process of food preservation in which packaged foods (e.g., milk and fruit juices) are treated with mild heat, usually to less than , to eliminate pathogens and extend shelf life ...

, deep-freezing, desiccation

Desiccation is the state of extreme dryness, or the process of extreme drying. A desiccant is a hygroscopic (attracts and holds water) substance that induces or sustains such a state in its local vicinity in a moderately sealed container. The ...

and ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

radiation. Dormant spores can lie inert for years until heat shock

The heat shock response (HSR) is a cell stress response that increases the number of molecular chaperones to combat the negative effects on proteins caused by stressors such as increased temperatures, oxidative stress, and heavy metals. In a norm ...

, seasonal wetting or other cues trigger germ tube

A germ tube is an outgrowth produced by spores of spore-releasing fungi during germination.

The germ tube differentiates, grows, and develops by mitosis to create somatic hyphae.C.J. Alexopolous, Charles W. Mims, M. Blackwell, ''Introductory My ...

emergence. Such structural and developmental traits are mainstays of fungal taxonomy

image:Hierarchical clustering diagram.png, 280px, Generalized scheme of taxonomy

Taxonomy is a practice and science concerned with classification or categorization. Typically, there are two parts to it: the development of an underlying scheme o ...

and phylogenetic inference.

Ascospore biology resonates far beyond the microscope slide. Airborne showers initiate apple scab

Apple scab is a common disease of plants in the rose family (Rosaceae) that is caused by the ascomycete fungus ''Venturia inaequalis''. While this disease affects several plant genera, including '' Sorbus, Cotoneaster,'' and '' Pyrus'', it is ...

epidemics and other plant disease

Plant diseases are diseases in plants caused by pathogens (infectious organisms) and environmental conditions (physiological factors). Organisms that cause infectious disease include fungi, oomycetes, bacteria, viruses, viroids, virus-like or ...

s, heat-resistant spores of ''Talaromyces

''Talaromyces'' is a genus of fungi in the family Trichocomaceae. Described in 1955 by American mycologist Chester Ray Benjamin, species in the genus form soft, cottony fruit bodies ( ascocarps) with cell walls made of tightly interwoven hyphae ...

'' and ''Paecilomyces

''Paecilomyces'' is a genus of fungi. A number of species in this genus are plant pathogens.

Several of the entomopathogenic fungi, entomopathogenic species, such as "''Paecilomyces fumosoroseus''" have now been placed in the genus ''Isaria'', ...

'' spoil shelf-stable fruit products, and geneticists dissect ordered tetrads of ''Saccharomyces

''Saccharomyces'' is a genus of fungi that includes many species of yeasts. ''Saccharomyces'' is from Greek σάκχαρον (sugar) and μύκης (fungus) and means ''sugar fungus''. Many members of this genus are considered very important in f ...

'' to map genes and breed new brewing strains. Industry banks hardy spores of ''Aspergillus

' () is a genus consisting of several hundred mold species found in various climates worldwide.

''Aspergillus'' was first catalogued in 1729 by the Italian priest and biologist Pier Antonio Micheli. Viewing the fungi under a microscope, Miche ...

'' and ''Penicillium

''Penicillium'' () is a genus of Ascomycota, ascomycetous fungus, fungi that is part of the mycobiome of many species and is of major importance in the natural environment, in food spoilage, and in food and drug production.

Some members of th ...

'' to seed cheese-ripening and enzyme production, while aerosol scientists trace melanin

Melanin (; ) is a family of biomolecules organized as oligomers or polymers, which among other functions provide the pigments of many organisms. Melanin pigments are produced in a specialized group of cells known as melanocytes.

There are ...

-laden ascospores in the nocturnal boundary layer, where they seed cloud droplets and even ice at . Because of their combined functions in evolution, ecology, agriculture, biotechnology and atmospheric processes, ascospores are a key means by which many fungi persist and spread.

Terminology and historical context

The term ''ascus'' (plural ''asci'') derives from the Greek , meaning 'sac' or 'wineskin', and was first applied in the 1830s to the distinctive spore-bearing sac of Ascomycota. Long before the terms themselves were formalized,Pier Antonio Micheli

Pier Antonio Micheli (11 December 1679 – 1 January 1737) was a noted Italian botanist, professor of botany in Pisa, curator of the Orto Botanico di Firenze, author of ''Nova plantarum genera iuxta Tournefortii methodum disposita''. He discover ...

's 1729 work ''Nova plantarum genera'' depicted an ascus containing four ellipsoid

An ellipsoid is a surface that can be obtained from a sphere by deforming it by means of directional Scaling (geometry), scalings, or more generally, of an affine transformation.

An ellipsoid is a quadric surface; that is, a Surface (mathemat ...

spores—the earliest known published image of ascospores. In 1788, Johann Hedwig

Johann Hedwig (8 December 1730 – 18 February 1799), also styled as Johannes Hedwig, was a German botanist notable for his studies of mosses. He is sometimes called the "father of bryology". He is known for his particular observations of sexual ...

showed that '' Scutellinia scutellata'' typically produces eight spores per ascus. In 1816, Christian Gottfried Daniel Nees von Esenbeck

Christian Gottfried Daniel Nees von Esenbeck (14 February 1776 – 16 March 1858) was a prolific Germany, German botanist, physician, zoologist, and natural philosopher. He was a contemporary of Goethe and was born within the lifetime of Carl Li ...

redefined the botanical term theca

In biology, a theca (: thecae) is a sheath or a covering.

Botany

In botany, the theca is related to plant's flower anatomy. The theca of an angiosperm consists of a pair of microsporangia that are adjacent to each other and share a common ar ...

to refer only to moss capsules and adopted ''ascus'' for these fungal sacs.

The word ''ascospore'', meaning "spore from an ascus", first appeared in 1875, once microscopists had confirmed that asci hold distinct reproductive spores. Alfred Möller is credited with being the first to grow a lichen thallus ('' Lecanora chlarotera'') from an ascospore in 1887. In the late 1800s, Heinrich Anton de Bary

Heinrich Anton de Bary (26 January 183119 January 1888) was a German surgeon, botanist, microbiologist, and mycologist (fungal systematics and physiology).

He is considered a founding father of plant pathology (phytopathology) as well as the fou ...

proposed that the ascus functions as a sexual organ. This was confirmed in 1894 by P.A. Dangeard, who observed nuclear fusion (karyogamy

Karyogamy is the final step in the process of fusing together two haploid eukaryotic cells, and refers specifically to the fusion of the two cell nucleus, nuclei. Before karyogamy, each haploid cell has one complete copy of the organism's genome. ...

) and meiosis

Meiosis () is a special type of cell division of germ cells in sexually-reproducing organisms that produces the gametes, the sperm or egg cells. It involves two rounds of division that ultimately result in four cells, each with only one c ...

inside ''Peziza'' asci, demonstrating that ascospores are formed through sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction is a type of reproduction that involves a complex life cycle in which a gamete ( haploid reproductive cells, such as a sperm or egg cell) with a single set of chromosomes combines with another gamete to produce a zygote tha ...

. Subsequent work by Harold Wager and A. Harry Harper clarified the nuclear events inside the ascus: two meiotic divisions followed by a mitosis, producing the usual eight ascospores in many species. These findings confirmed that ascospores are the sexual progeny of Ascomycota—comparable to plant seeds—rather than asexual reproductive units.

During the 20th century, fungi without known asci or ascospores were grouped into an artificial category called ''Deuteromycota'', or " fungi imperfecti". Advances in culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

methods and DNA sequencing

DNA sequencing is the process of determining the nucleic acid sequence – the order of nucleotides in DNA. It includes any method or technology that is used to determine the order of the four bases: adenine, thymine, cytosine, and guanine. The ...

later showed that most of these supposedly asexual fungi are actually Ascomycota, even if their sexual stages are rarely seen. Genetic evidence has connected many presumed asexual lineages to ascospore-forming ancestors, reaffirming the central role of the ascus and ascospores in the life cycles to most sac fungi. In response, the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants

The ''International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants'' (ICN or ICNafp) is the set of rules and recommendations dealing with the formal botanical names that are given to plants, fungi and a few other groups of organisms, all tho ...

unified the naming of anamorph and teleomorphs (asexual and sexual forms) under a single scientific name, recognizing that both stages are part of the same species.

Taxonomic context and phylogeny

Ascospores are the defining sexual spores of the division

Ascospores are the defining sexual spores of the division Ascomycota

Ascomycota is a phylum of the kingdom Fungi that, together with the Basidiomycota, forms the subkingdom Dikarya. Its members are commonly known as the sac fungi or ascomycetes. It is the largest phylum of Fungi, with over 64,000 species. The def ...

, which—together with the Basidiomycota

Basidiomycota () is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Basi ...

—comprises one of the two major lineages of the fungal kingdom. Ascospory probably originated early in the divergence

In vector calculus, divergence is a vector operator that operates on a vector field, producing a scalar field giving the rate that the vector field alters the volume in an infinitesimal neighborhood of each point. (In 2D this "volume" refers to ...

of Ascomycota from other fungi. Its presence is a synapomorphic trait—one that defines and unites this lineage. Comparative studies indicate that ascospore-producing fungi (ascomycetes) and basidiospore

A basidiospore is a reproductive spore produced by basidiomycete fungi, a grouping that includes mushrooms, shelf fungi, rusts, and smuts. Basidiospores typically each contain one haploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromos ...

-producing fungi (basidiomycetes) share a common ancestor with a dikaryotic stage, but evolved different spore-producing structures and dispersal strategies. About two-thirds of all described fungal species—around 100,000—belong to Ascomycota. Molecular surveys suggest that millions more ascospore-producing species remain undiscovered, particularly among microscopic endophyte

An endophyte is an endosymbiont, often a bacterium or fungus, that lives within a plant for at least part of its life cycle without causing apparent disease. Endophytes are ubiquitous and have been found in all species of plants studied to date; ...

s and soil-dwelling saprobes.

Historically, ascospore traits—such as size, colour, septation, and surface texture—were central to fungal classification. In modern analyses, DNA-based phylogenies are primary, but ascospore morphology still aids in defining species boundaries. Molecular identification usually begins with sequencing the internal transcribed spacer

Internal transcribed spacer (ITS) is the spacer DNA situated between the small-subunit ribosomal RNA (rRNA) and large-subunit rRNA genes in the chromosome or the corresponding transcribed region in the polycistronic rRNA precursor transcript.

...

(ITS) region, the standard DNA barcode for fungi. Additional markers, such as LSU, RPB2, TEF1, are often used to separate cryptic species that share similar ascospore traits. DNA barcodes are compared to reference libraries like UNITE and GenBank

The GenBank sequence database is an open access, annotated collection of all publicly available nucleotide sequences and their protein translations. It is produced and maintained by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI; a par ...

. MycoBank

MycoBank is an online database, documenting new mycological names and combinations, eventually combined with descriptions and illustrations. It is run by the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute in Utrecht.

Each novelty, after being screene ...

links these sequences to formal species names and physical specimens, preserving the connection between morphology and genetic identity. Molecular phylogenies have generally supported traditional groupings based on ascus and ascospore traits. However, many spore forms are homoplasious—traits that evolved multiple times independently—prompting taxonomic revision. An exception is the thick-walled, spores of the lichen families Physciaceae and Teloschistaceae, whose shared structure reflects true evolutionary kinship.

The oldest unambiguous ascospore fossils occur in the Early Devonian

The Early Devonian is the first of three Epoch (geology), epochs comprising the Devonian period, corresponding to the Lower Devonian Series (stratigraphy), series. It lasted from and began with the Lochkovian Stage , which was followed by the Pr ...

-era Rhynie chert

The Rhynie chert is a Lower Devonian Sedimentary rock, sedimentary deposit exhibiting extraordinary fossil detail or completeness (a Lagerstätte). It is exposed near the village of Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, Scotland; a second unit, the Windyfield ...

, where preserved perithecia contain asci filled with lens-shaped spores. Molecular clock

The molecular clock is a figurative term for a technique that uses the mutation rate of biomolecules to deduce the time in prehistory when two or more life forms diverged. The biomolecular data used for such calculations are usually nucleot ...

studies, using these and a few Carboniferous

The Carboniferous ( ) is a Geologic time scale, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era that spans 60 million years, from the end of the Devonian Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the ...

fossils for calibration, estimate that ascospory arose in the late Neoproterozoic

The Neoproterozoic Era is the last of the three geologic eras of the Proterozoic geologic eon, eon, spanning from 1 billion to 538.8 million years ago, and is the last era of the Precambrian "supereon". It is preceded by the Mesoproterozoic era an ...

to Cambrian

The Cambrian ( ) is the first geological period of the Paleozoic Era, and the Phanerozoic Eon. The Cambrian lasted 51.95 million years from the end of the preceding Ediacaran period 538.8 Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Ordov ...

, no unambiguous fossils are known from before the Devonian.

Development and cytology

Ascus types and arrangement

Four main multicellularfruit body

The sporocarp (also known as fruiting body, fruit body or fruitbody) of fungi is a multicellular structure on which spore-producing structures, such as basidia or asci, are borne. The fruitbody is part of the sexual phase of a fungal life cyc ...

types occur in Ascomycota—cleistothecia, perithecia, apothecia and pseudothecia, each housing asci in a different architecture. Apothecia

An ascocarp, or ascoma (: ascomata), is the fruiting body ( sporocarp) of an ascomycete phylum fungus. It consists of very tightly interwoven hyphae and millions of embedded asci, each of which typically contains four to eight ascospores. As ...

are open cup- or disc-shaped fruit bodies where the spore-bearing layer (call the ''hymenium

The hymenium is the tissue layer on the hymenophore of a fungal fruiting body where the cells develop into basidia or asci, which produce spores. In some species all of the cells of the hymenium develop into basidia or asci, while in oth ...

'') is fully exposed. Perithecia

An ascocarp, or ascoma (: ascomata), is the fruiting body ( sporocarp) of an ascomycete phylum fungus. It consists of very tightly interwoven hyphae and millions of embedded asci, each of which typically contains four to eight ascospores. Ascoc ...

are enclosed, flask-shaped structures that discharge ascospores through a small opening at the top, known as an ''ostiole

An ''ostiole'' is a small hole or opening through which algae or fungi release their mature spores.

The word is a diminutive of wikt:ostium, "ostium", "opening".

The term is also used in higher plants, for example to denote the opening of the ...

''. Cleistothecia stay entirely sealed until their walls break open or decay. Pseudothecia—also called ''ascostromata''—contain asci embedded in chambers (locules) that form within a dense fungal tissue called a stroma. A fifth architecture—naked asci borne directly on the fungal filaments (hypha

A hypha (; ) is a long, branching, filamentous structure of a fungus, oomycete, or actinobacterium. In most fungi, hyphae are the main mode of vegetative growth, and are collectively called a mycelium.

Structure

A hypha consists of one o ...

e)—is found in early-diverging groups like Taphrinomycetes

The Taphrinomycetes are a class of ascomycete fungi belonging to the subdivision Taphrinomycotina. It includes the single order Taphrinales, which includes 2 families, 8 genera and 140 species

A species () is often defined as the largest ...

and in some yeasts. These complete the typical set of ascospore-producing structures.

Each ascus structure supports a different ecological strategy. The apothecia of cup fungi (e.g. '' Sarcoscypha'', '' Cladonia'') provide a broad, exposed surface that allows wind to carry off the forcibly ejected spores. Perithecia and pseudothecia, common in wood- and leaf-inhabiting fungi, protect the asci until pressure builds and shoots the spores through the narrow ostiole—an effective way to escape crowded or enclosed surfaces. Cleistothecia—found in powdery mildew

Powdery mildew is a fungus, fungal disease that affects a wide range of plants. Powdery mildew diseases are caused by many different species of Ascomycota, ascomycete fungi in the order Erysiphales. Powdery mildew is one of the easier plant disea ...

s and underground truffles—shield their asci from drying out and from UV damage, but they rely on external forces like weathering or animals to break open and release their spores. Species with naked asci, such as some yeasts and the leaf parasite ''Taphrina'', skip fruit body formation entirely. Their spores are released on site and spread by rain, insects, or direct contact.

Ascus development

In filamentous ascomycetes, sexual development begins when two compatible cells fuse their cytoplasm—a process called ''plasmogamy

Plasmogamy is a stage in the sexual reproduction of fungi, in which the protoplasm of two parent cells (usually from the mycelia) fuse without the fusion of nuclei, effectively bringing two haploid nuclei close together in the same cell. This st ...

''—forming a filament (hypha) where each cell contains a pair of nuclei. This stage is called ''dikaryotic''. Near the growing tip, a hook-shaped cell known as a ''crozier

A crozier or crosier (also known as a paterissa, pastoral staff, or bishop's staff) is a stylized staff that is a symbol of the governing office of a bishop or abbot and is carried by high-ranking prelates of Roman Catholic, Eastern Catholi ...

'' forms. This structure organizes the nuclei so they can fuse and divide correctly. In most filamentous fungi, sexual development begins when nutrients like carbon or nitrogen run low. The ascus mother cell—where spores form—is the only diploid

Ploidy () is the number of complete sets of chromosomes in a cell, and hence the number of possible alleles for autosomal and pseudoautosomal genes. Here ''sets of chromosomes'' refers to the number of maternal and paternal chromosome copies, ...

stage in the life-cycle, and it remains diploid only briefly. In most filamentous fungi, sexual development begins when nutrients like carbon or nitrogen run low. High levels of glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

or ammonium

Ammonium is a modified form of ammonia that has an extra hydrogen atom. It is a positively charged (cationic) polyatomic ion, molecular ion with the chemical formula or . It is formed by the protonation, addition of a proton (a hydrogen nucleu ...

suppress this process, whereas blue light can guide the direction in which the fruit body develops.

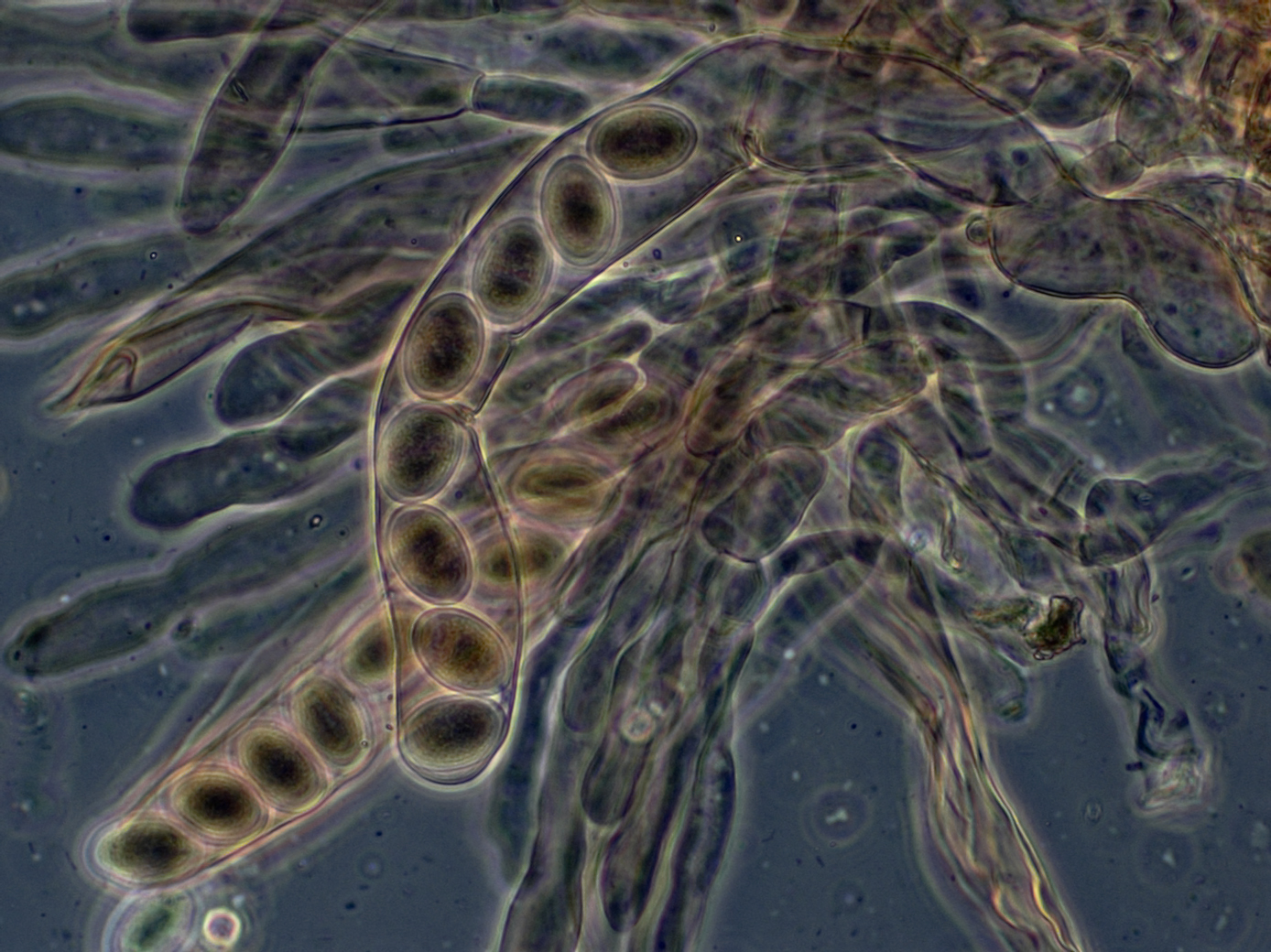

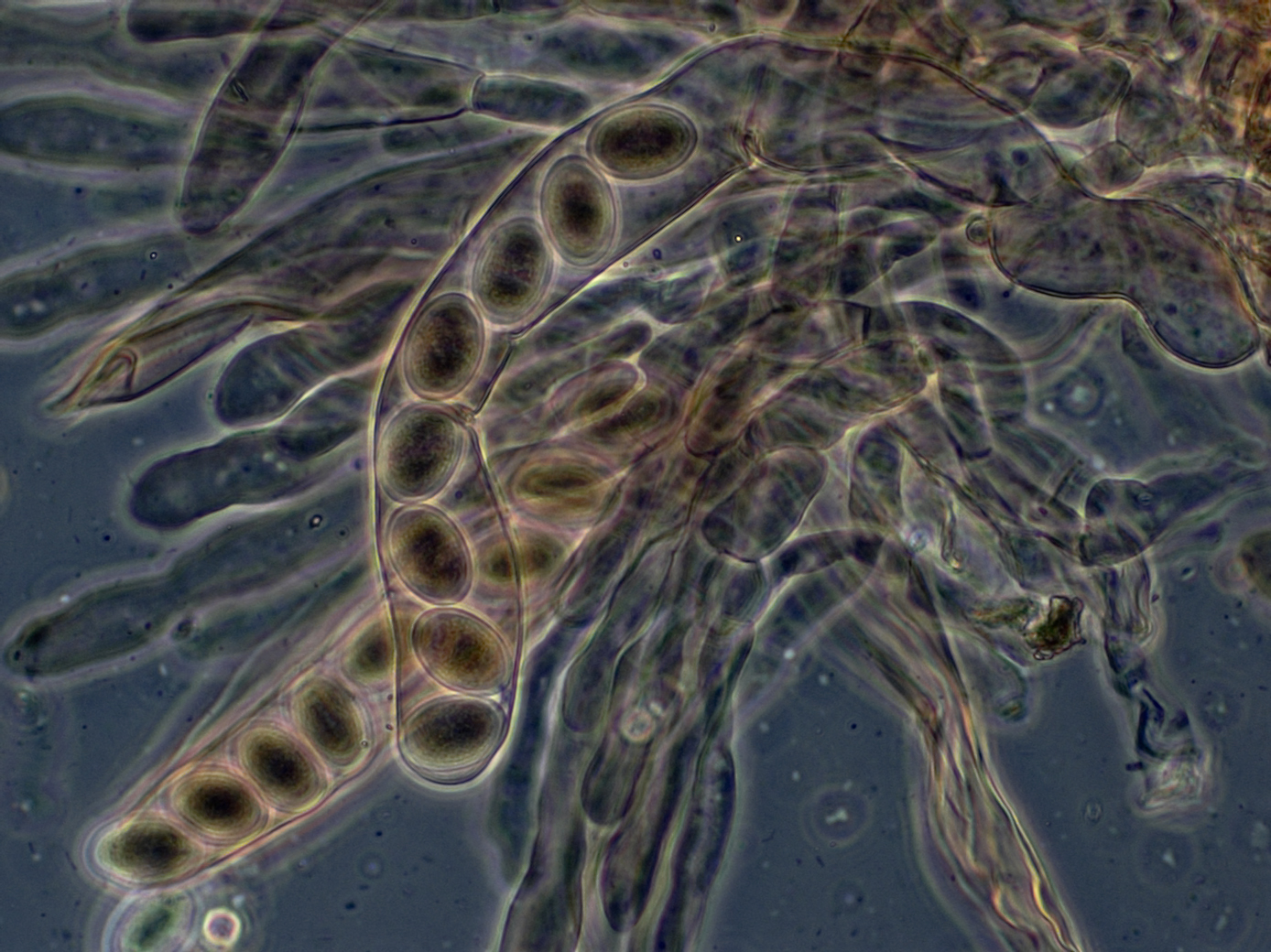

After the crozier sets up the ascus mother cell and the paired nuclei fuse (karyogamy), the ascus begins dividing its cytoplasm. A double-membrane system forms around each future spore. Electron-microscope work on '' Lophodermella sulcigena'' shows that this delimiting double membrane is continuous with the ascus plasmalemma rather than derived from the nuclear envelope. The developing ascus wraps its contents in membranes to form individual spores. Specialists refer to these as or modes, depending on how the membranes form. In some fungi, all eight spores are first enclosed together in a shared membrane tube that later divides. In others, each spore is wrapped separately from the beginning. Both strategies produce eight membrane-bounded compartments ready for wall building. The residual epiplasm trapped above those membranes constitutes the ocular chamber (or oculus), a lens-shaped pocket ringed by the thickened bourrelet at the ascus apex; its diameter and amyloid reaction are taxonomically diagnostic in several Pezizales

The Pezizales are an order of the subphylum Pezizomycotina within the phylum Ascomycota. The order contains 16 families, 199 genera, and 1683 species. It contains a number of species of economic importance, such as morels, the black and whit ...

genera.

After karyogamy, the resulting diploid nucleus (zygote

A zygote (; , ) is a eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cell formed by a fertilization event between two gametes.

The zygote's genome is a combination of the DNA in each gamete, and contains all of the genetic information of a new individ ...

) undergoes meiosis to produce four haploid nuclei. An additional mitotic division usually follows, yielding eight nuclei—four pairs of genetically identical "twins". These sister nuclei form adjacent spores, a feature exploited in classical genetics

Classical genetics is the branch of genetics based solely on visible results of reproductive acts. It is the oldest discipline in the field of genetics, going back to the experiments on Mendelian inheritance by Gregor Mendel who made it possible ...

experiments like ''Neurospora'' tetrad analysis. In species that lay down internal cross-walls, further mitotic cycles continue inside each developing ascospore so that every compartment ultimately carries its own nucleus, establishing a multicellular yet genetically uniform propagule. Each nucleus

Nucleus (: nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucleu ...

is packaged into an "ascospore initial"—a small, membrane-bound bubble of cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

within the ascus. The membrane system that forms these packets usually comes from either the ascus's plasma membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

, although in some yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

s it originates from the nuclear membrane

The nuclear envelope, also known as the nuclear membrane, is made up of two lipid bilayer polar membrane, membranes that in eukaryotic cells surround the Cell nucleus, nucleus, which encloses the genome, genetic material.

The nuclear envelope con ...

. This pair of membranes is known as the ''enveloping-membrane system'' (EMS). As the spore wall forms, the inner membrane becomes the spore's own cell membrane. The outer one remains outside the spore and helps anchor the first threads of its protective wall. In most budding yeasts ( Saccharomycetales) the EMS wraps all the nuclei in a single vesicle that splits apart later. In filamentous ascomycetes, by contrast, individual spore membranes form separately from the beginning. This membrane system divides the ascus cytoplasm into as many compartments as there are nuclei—effectively creating the young spores. Each spore then builds its own membrane and wall, while the leftover cytoplasm (called ''epiplasm'') remains to support their growth. In the lichen Trypetheliaceae, each ascospore starts by forming a single true cross-wall (''euseptum''). Additional cross-walls () grow outward from the centre. Temporary wall thickenings appear through this process but are ultimately resorbed.

Wall maturation and chemistry

Developing ascospores build thick, durablecell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

s that differ significantly from the walls of ordinary fungal hyphae. These walls are usually multi-layered. The inner layers contain glucan

A glucan is a polysaccharide derived from D-glucose, linked by glycosidic bonds. Glucans are noted in two forms: alpha glucans and beta glucans. Many beta-glucans are medically important. They represent a drug target for antifungal medications of ...

s and other polysaccharide

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

s, similar to typical fungal cells, while the outer layers are specialized for durability. In baker's yeast (''Saccharomyces cerevisiae

''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' () (brewer's yeast or baker's yeast) is a species of yeast (single-celled fungal microorganisms). The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have be ...

''), for example, the spore wall includes a chitosan

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide composed of randomly distributed β-(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine (deacetylated unit) and ''N''-acetyl-D-glucosamine (acetylated unit). It is made by treating the chitin shells of shrimp and other crusta ...

-rich layer and a tough outer coat made of cross-linked dityrosine, an amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

polymer. This structure gives the spores exceptional resistance to heat, drying, and enzymes that would normally break down cells. Residual cytoplasm (epiplasm) within the ascus often contributes materials that shape surface ornamentation—such as ridges or spines—on the outer wall of ornamented ascospores. In yeasts, the original cell transforms into an ascus containing four spores. In filamentous fungi, by contrast, the ascus is a new, specialized cell that typically holds eight spores. Despite these differences, the underlying cytology

Cell biology (also cellular biology or cytology) is a branch of biology that studies the structure, function, and behavior of cells. All living organisms are made of cells. A cell is the basic unit of life that is responsible for the living an ...

– karyogamy followed by meiotic sporogenesis within a single mother cell – is shared. By the time an ascus is ready to discharge its spores, each ascospore is a discrete, walled cell harbouring a haploid nucleus (or nuclei) and any preparatory food reserves. The ascus may then rupture or develop a pore through which the ascospores exit, leaving behind only empty ascus husks.

Structurally, the ascospore wall is a layered composite. Its innermost layers resemble the standard fungal cell wall, while its outer layers are unique to the spore stage. The inner wall is built from a framework of β-glucan

Beta-glucans, β-glucans comprise a group of β-D-glucose polysaccharides (glucans) naturally occurring in the cell walls of cereals, bacteria, and Fungus, fungi, with significantly differing Physical chemistry, physicochemical properties depen ...

woven with chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

, laid down as soon as the young spore is sealed off from the surrounding ascus.chitosan

Chitosan is a linear polysaccharide composed of randomly distributed β-(1→4)-linked D-glucosamine (deacetylated unit) and ''N''-acetyl-D-glucosamine (acetylated unit). It is made by treating the chitin shells of shrimp and other crusta ...

; in ''Saccharomyces cerevisiae'' the Chs3–Cda1/Cda2 pathway, assisted by the chitosan-modifying proteins Cts1 and Cts2, converts almost the entire chitin fraction, creating a positively charged base that helps anchor later wall layers. Filamentous ascomycetes follow a similar process, though their chitosan layer is thinner and often contains β-1,6-glucan. Many lichen fungi and '' Taphrina'' species add a second layer rich in mannoproteins or galactomannans—sugar-containing proteins that add further strength or function. In many soil saprobes a lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

-rich middle layer adds further protection against drying.

Exterior to those carbohydrate zones the wall acquires lineage-specific reinforcements. In some species, a tough dityrosine polymer—built in the ascus cytoplasm and transported outward—forms a UV-blocking, waterproof outer coat. In contrast, many Dothideomycetes

Dothideomycetes is the largest and most diverse class of ascomycete fungi. It comprises 11 orders 90 families, 1,300 genera and over 19,000 known species.

Wijayawardene et al. in 2020 added more orders to the class.

Traditionally, most of it ...

and Xylariales embed melanin-like pigments into the wall, giving rise to the dark brown or black spores familiar to field mycologists. Another approach is to build outer walls from tough polyaromatic

A Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) is any member of a class of organic compounds that is composed of multiple fused aromatic rings. Most are produced by the incomplete combustion of organic matter— by engine exhaust fumes, tobacco, incine ...

compounds like sporopollenin, a material known for its extreme chemical resistance. Chemical studies of yeast spores have also identified an unknown component—tentatively called the "Chi polymer"—which lies between the chitosan and dityrosine layers. In ''Aspergillus nidulans'', the red anthraquinone

Anthraquinone, also called anthracenedione or dioxoanthracene, is an aromatic hydrocarbon, aromatic organic compound with formula . Several isomers exist but these terms usually refer to 9,10-anthraquinone (IUPAC: 9,10-dioxoanthracene) wherein th ...

pigment asperthecin, is built into the ascospore wall; mutants lacking the pigment form hyaline, misshapen spores that are about 100-fold more sensitive to UVC light, underscoring the protective role of wall-bound chromophore

A chromophore is the part of a molecule responsible for its color. The word is derived .

The color that is seen by our eyes is that of the light not Absorption (electromagnetic radiation), absorbed by the reflecting object within a certain wavele ...

s. Finally, decorative surface features are laid on top of these protective layers. These include spines, ridges, or hydrophobin rodlets that often require electron microscopy to see. The proteins that sculpt these structures can by used to help identify species, for instance, the distinctive rodlet proteins of ''Chaetomium

''Chaetomium'' is a genus of fungi in the Chaetomiaceae family. It is a dematiaceous (dark-walled) Mold (fungus), mold normally found in soil, air, cellulose and plant debris. According to the ''Dictionary of the Fungi'' (10th edition, 2008), th ...

'' and ''Talaromyces

''Talaromyces'' is a genus of fungi in the family Trichocomaceae. Described in 1955 by American mycologist Chester Ray Benjamin, species in the genus form soft, cottony fruit bodies ( ascocarps) with cell walls made of tightly interwoven hyphae ...

''.

These biochemical differences among Ascomycota are reflected in their survival strategies. Lichen

A lichen ( , ) is a hybrid colony (biology), colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among hypha, filaments of multiple fungus species, along with yeasts and bacteria embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualism (biology), m ...

-forming fungi often produce outer walls coated in galactose

Galactose (, ''wikt:galacto-, galacto-'' + ''wikt:-ose#Suffix 2, -ose'', ), sometimes abbreviated Gal, is a monosaccharide sugar that is about as sweetness, sweet as glucose, and about 65% as sweet as sucrose. It is an aldohexose and a C-4 epime ...

-rich polysaccharides. These swell into mucilage when wet, aiding both water retention and attachment to surfaces. These chemical modifications explain why ascospore walls differ so much in permeability, staining

Staining is a technique used to enhance contrast in samples, generally at the Microscope, microscopic level. Stains and dyes are frequently used in histology (microscopic study of biological tissue (biology), tissues), in cytology (microscopic ...

behaviour, trace metal binding, and ecological function, allowing some spores to survive intense UV light high in the atmosphere, while others pass unharmed through the digestive tracts of animals like truffle-eating mammals.

Morphology and ornamentation

Ascospores display tremendous variation in form, offering key features used by mycologists for classification. Their shapes range from spherical () toellipsoid

An ellipsoid is a surface that can be obtained from a sphere by deforming it by means of directional Scaling (geometry), scalings, or more generally, of an affine transformation.

An ellipsoid is a quadric surface; that is, a Surface (mathemat ...

, cylindrical, needle-like, and even spiral or helical forms. Most mature ascospores are single-celled (non-septate

In biology, a septum (Latin for ''something that encloses''; septa) is a wall, dividing a cavity or structure into smaller ones. A cavity or structure divided in this way may be referred to as septate.

Examples

Human anatomy

* Interatrial se ...

), though many species produce spores with one or more internal divisions. Immature spores are often colourless and translucent (hyaline

A hyaline substance is one with a glassy appearance. The word is derived from , and .

Histopathology

Hyaline cartilage is named after its glassy appearance on fresh gross pathology. On light microscopy of H&E stained slides, the extracellula ...

), but many darken as they mature, gaining yellow, brown, olive, or black pigmentation

A pigment is a powder used to add or alter color or change visual appearance. Pigments are completely or nearly insoluble and chemically unreactive in water or another medium; in contrast, dyes are colored substances which are soluble or go in ...

often through melanin deposition, which helps shield the spore from ultraviolet radiation and environmental stress.

Spore walls are often multi-layered, with thickness and texture differing among species. Some ascospores are smooth and almost glassy-like, appearing highly refractive

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenome ...

under the microscope, whereas others are covered in surface ornamentation. Under light microscopy or scanning electron microscopy

A scanning electron microscope (SEM) is a type of electron microscope that produces images of a sample by scanning the surface with a focused beam of electrons. The electrons interact with atoms in the sample, producing various signals that ...

, ascospores may show an array of ornamentation. For example, spores of ''Tuber'' truffles bear dense spines or a net-like (reticulate) surface pattern. Other spores may display ridges, warts, spiral grooves, or carry gelatinous sheaths and threadlike appendages. A distinct gelatinous envelope is termed a ' or ''halo'', and such spores are described as '. In addition to shape and colour, these features of the spore wall are often critical for species identification. Diagnostic traits may also include the number of wall layers, presence of mucilage, reaction to iodine

Iodine is a chemical element; it has symbol I and atomic number 53. The heaviest of the stable halogens, it exists at standard conditions as a semi-lustrous, non-metallic solid that melts to form a deep violet liquid at , and boils to a vi ...

stains (amyloid

Amyloids are aggregates of proteins characterised by a fibrillar morphology of typically 7–13 nm in diameter, a β-sheet secondary structure (known as cross-β) and ability to be stained by particular dyes, such as Congo red. In the human ...

or not), and the presence of internal oil droplets (guttules).

These morphological traits remain essential for taxonomy and species recognition. Traditional fungal identification key

In biology, an identification key, taxonomic key, or frequently just key, is a printed or computer-aided device that aids in the identification of biological organisms.

Historically, the most common type of identification key is the dichotomous k ...

s often with ascospore features such as size, shape, septation, and colour. For example, the lichen family Sagiolechiaceae is partly defined by its colourless spores, which are transversely septate or —divided into a grid by both transverse and longitudinal walls. The number of internal cells can also distinguish genera: many lichen-forming ascomycetes have multicellular (septate) spores, while yeasts like ''Saccharomyces

''Saccharomyces'' is a genus of fungi that includes many species of yeasts. ''Saccharomyces'' is from Greek σάκχαρον (sugar) and μύκης (fungus) and means ''sugar fungus''. Many members of this genus are considered very important in f ...

'' produce simple, single-celled oval ascospores.

Ascospore shapes range from simple spheres and ovals to more elaborate forms—such as elongated, hat-shaped (''galeate''), or constricted (''isthmoid'') types. Spore size is also variable; most fall between 5–50

Ascospore shapes range from simple spheres and ovals to more elaborate forms—such as elongated, hat-shaped (''galeate''), or constricted (''isthmoid'') types. Spore size is also variable; most fall between 5–50 micrometre

The micrometre (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American English), also commonly known by the non-SI term micron, is a uni ...

s (one thousandth of a millimetre, abbreviated μm) in length, though extremes reaching over 200 μm long and 75 μm wide are known. Some lichen-forming fungi greatly exceed typical size ranges: '' Ocellularia subpraestans'' routinely produces ascospores 750 × 50 μm and exceptionally up to 880 × 65 μm—the longest yet recorded for any fungus. The largest measured spore volume belongs to '' Pertusaria melanochlora'' (300 × 200 μm, equivalent to 0.05 cubic millimetres). The ascospore wall is often a complex, multilayered structure that can be smooth or exhibit various ornamentations. These may include surface patterns, such as the rodlet patterning found in some ''Chaetomium

''Chaetomium'' is a genus of fungi in the Chaetomiaceae family. It is a dematiaceous (dark-walled) Mold (fungus), mold normally found in soil, air, cellulose and plant debris. According to the ''Dictionary of the Fungi'' (10th edition, 2008), th ...

'' species, or distinct structures like appendages. In marine fungi such as '' Halosphaeria'' and '' Lulworthia'', spores are encased in gelatinous sheaths or caps that swell into threadlike appendages when wet. These structures enlarge surface area to slow sinking and later act as sticky anchors, attaching the spore to submerged wood or seagrass

Seagrasses are the only flowering plants which grow in marine (ocean), marine environments. There are about 60 species of fully marine seagrasses which belong to four Family (biology), families (Posidoniaceae, Zosteraceae, Hydrocharitaceae and ...

. The morphological diversity of ascospores reflects adaptations to various ecological niches and dispersal strategies, and often provides important taxonomic characteristics for fungal classification. Some species even produce spores of different sizes or colours within a single ascus. For example, '' Podospora arizonensis'' produces both large, pigmented spores and small, hyaline spores within the same ascus. This dimorphism may serve as a bet-hedging strategy, allowing the fungus to exploit different ecological opportunities.

Even missing traits can be diagnostic—for example, '' Taphrina'' ascospores lack true walls and bud

In botany, a bud is an undeveloped or Plant embryogenesis, embryonic Shoot (botany), shoot and normally occurs in the axil of a leaf or at the tip of a Plant stem, stem. Once formed, a bud may remain for some time in a dormancy, dormant conditi ...

like yeast cells. Microscopic techniques such as phase-contrast

__NOTOC__

Phase-contrast microscopy (PCM) is an optical microscopy technique that converts phase shifts in light passing through a transparent specimen to brightness changes in the image. Phase shifts themselves are invisible, but become visible ...

or differential interference contrast microscopy

Differential interference contrast (DIC) microscopy, also known as Nomarski interference contrast (NIC) or Nomarski microscopy, is an optical microscopy technique used to enhance the contrast in unstained, transparent samples. DIC works on the ...

help reveal these details of ascospore ornamentation and septation. In practice, mycologists often stain

A stain is a discoloration that can be clearly distinguished from the surface, material, or medium it is found upon. They are caused by the chemical or physical interaction of two dissimilar materials. Accidental staining may make materials app ...

spores with dyes such as lactofuchsin or cotton blue to observe shape and internal septa, test a drop of iodine (Melzer's reagent

Melzer's reagent (also known as Melzer's iodine reagent, Melzer's solution or informally as Melzer's) is a chemical reagent used by mycologists to assist with the identification of fungi, and by phytopathologists for fungi that are plant pathogens ...

) for any amyloid blueing reaction, and note surface ornamentation at high magnification. These features—often preserved even in dried herbarium

A herbarium (plural: herbaria) is a collection of preserved plant biological specimen, specimens and associated data used for scientific study.

The specimens may be whole plants or plant parts; these will usually be in dried form mounted on a sh ...

specimens—have long been central to defining ascomycete taxa. Modern approaches, including electron microscopy

An electron microscope is a microscope that uses a beam of electrons as a source of illumination. It uses electron optics that are analogous to the glass lenses of an optical light microscope to control the electron beam, for instance focusing i ...

, have supplemented these criteria with ultrastructural characters (such as wall layering patterns), but classical ascospore morphology remains one of the most reliable tools for identifying and classifying Ascomycota.

Discharge and dispersal mechanics

Asci shed their spores in two contrasting ways. In many lichens, yeasts and other fungi with prototunicate asci, the enclosing wall is so thin that once spores are mature it simply dissolves or ruptures. Autolytic enzymes—

Asci shed their spores in two contrasting ways. In many lichens, yeasts and other fungi with prototunicate asci, the enclosing wall is so thin that once spores are mature it simply dissolves or ruptures. Autolytic enzymes—acid phosphatase

Acid phosphatase (EC 3.1.3.2, systematic name ''phosphate-monoester phosphohydrolase (acid optimum)'') is an enzyme that frees attached phosphoryl groups from other molecules during digestion. It can be further classified as a phosphoric monoeste ...

is a marker—drive that wall deliquescence, and relative humidity decides when it begins. Because each ascus collapses on its own schedule, thalli such as '' Chaenotheca chrysocephala'' drip spores into the air for days, extending the window for interception by wind or rain splash. Aquatic relatives adapt the same principle for flotation: '' Halosarpheia'' and '' Torpedospora'' grow thread-like sails or parachutes that keep the newly freed spores suspended, while arenicolous (beach-dwelling) '' Corollospora'' spores collect in sea foam before sticking to fresh strand lines.

Fungi with unitunicate or bitunicate asci take the opposite tack, turning each ascus into a pressurised cannon. During the final seconds before firing the cell imbibes water, stretches up to four times its resting length and reaches about 0.3 MPa

MPA or mPa may refer to:

Academia

Academic degrees

* Master of Performing Arts

* Master of Professional Accountancy

* Master of Public Administration

* Master of Public Affairs

Schools

* Mesa Preparatory Academy

* Morgan Park Academy

* M ...

of turgor, fuelled by polyol

In organic chemistry, a polyol is an organic compound containing multiple hydroxyl groups (). The term "polyol" can have slightly different meanings depending on whether it is used in food science or polymer chemistry. Polyols containing two, th ...

s such as glycerol

Glycerol () is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, sweet-tasting, viscous liquid. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids known as glycerides. It is also widely used as a sweetener in the food industry and as a humectant in pha ...

or mannitol

Mannitol is a type of sugar alcohol used as a sweetener and medication. It is used as a low calorie sweetener as it is poorly absorbed by the intestines. As a medication, it is used to decrease pressure in the eyes, as in glaucoma, and to l ...

. When the apical operculum, amyloid ring or pore unlatches, spores shoot out at 20–30 metres per second (m/s)—accelerations that top 10,000 g and finish in under a millisecond. Hundreds of asci in a single perithecium can fire almost together after a humidity dip; their combined jet of moist air lifts later-firing spores clear of the still-air boundary layer

In physics and fluid mechanics, a boundary layer is the thin layer of fluid in the immediate vicinity of a Boundary (thermodynamic), bounding surface formed by the fluid flowing along the surface. The fluid's interaction with the wall induces ...

. In the bright-orange cup fungus '' Cookeina sulcipes'' roughly 1.7 million spores erupt from every square centimetre of hymenial surface in a single "puff".

Ballistic launch is tuned just to clear near-field obstacles—up to in crustose lichens and about in dung fungi such as ''Ascobolus''. Bitunicate asci often travel farther because the elastic inner wall balloons through the rigid exotunica before tearing. Once aloft, range depends on spore mass, ornamentation and any gelatinous sheath: needle-shaped spores of '' Sordaria'' slip through the air more efficiently than globose, mucilage-coated spores. Perithecia of '' Cyphelium inquinans'' need gusts above 5 m/s to detach their spores, whereas strong polar winds can loft discharged spores kilometres down-range.

Forcibly ejected ascospores form a conspicuous share of the 2–20 μm biological aerosol over cropland and woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with woody plants (trees and shrubs), or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the '' plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunli ...

canopies—especially during calm, humid nights. Their hydrophilic

A hydrophile is a molecule or other molecular entity that is attracted to water molecules and tends to be dissolved by water.Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon'' Oxford: Clarendon Press.

In contrast, hydrophobes are n ...

multilayered walls let them act as efficient cloud condensation nuclei

Cloud condensation nuclei (CCNs), also known as cloud seeds, are small particles typically 0.2 μm, or one hundredth the size of a cloud droplet. CCNs are a unique subset of aerosols in the atmosphere on which water vapour condenses. This c ...

, and melanised varieties nucleate ice at temperatures as warm as . Current aerosol-climate models assign 5–20 % of all ice-nucleating particles active at to fungal spores, most of them ascomycetous.

Germination biology

After discharge many ascospores will not germinate straight away, instead passing through a brief after-ripening or a longer dormancy whose length and triggers vary widely. Some lichens ('' Chaenotheca'', '' Cladonia'') shed spores that germinate within hours on a damp surface, oversized muriform spores of '' Ocellularia subpraestans'' start within minutes of release, whereas other taxa remain inert for months until seasonal cues arrive. Field trials show that crustose tropical lichens achieve the highest germination percentages, whereas

After discharge many ascospores will not germinate straight away, instead passing through a brief after-ripening or a longer dormancy whose length and triggers vary widely. Some lichens ('' Chaenotheca'', '' Cladonia'') shed spores that germinate within hours on a damp surface, oversized muriform spores of '' Ocellularia subpraestans'' start within minutes of release, whereas other taxa remain inert for months until seasonal cues arrive. Field trials show that crustose tropical lichens achieve the highest germination percentages, whereas foliose

A foliose lichen is a lichen with flat, leaf-like , which are generally not firmly bonded to the substrate on which it grows. It is one of the three most common lichen growth forms, growth forms of lichens. It typically has distinct upper and lo ...

(leafy) forms often germinate poorly even when they discharge readily. In temperate pathogens such as apple scab (''Venturia inaequalis

''Venturia inaequalis'' is an ascomycota, ascomycete fungus that causes the apple scab disease.

Systematics

''Venturia inaequalis'' anamorphs have been described under the names ''Fusicladium dendriticum'' and ''Spilocaea pomi''. Whether ''V. in ...

'') a winter-long chill followed by spring rain ends dormancy and synchronises infection of young leaves. Many spores stockpile trehalose

Trehalose (from Turkish '' tıgala'' – a sugar derived from insect cocoons + -ose) is a sugar consisting of two molecules of glucose. It is also known as mycose or tremalose. Some bacteria, fungi, plants and invertebrate animals synthesize it ...

, newly identified trehalose-based oligosaccharide

An oligosaccharide (; ) is a carbohydrate, saccharide polymer containing a small number (typically three to ten) of monosaccharides (simple sugars). Oligosaccharides can have many functions including Cell–cell recognition, cell recognition and ce ...

s, and lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s; they vitrify into a glass-like cytoplasm (the glass relaxes within minutes once water re-enters) and can stay viable for up to nine years in dry storage.

Some fungi impose specialised activation barriers. Fire-followers such as ''Neurospora crassa

''Neurospora crassa'' is a type of red bread mold of the phylum Ascomycota. The genus name, meaning 'nerve spore' in Greek, refers to the characteristic striations on the spores. The first published account of this fungus was from an infestatio ...

'' germinate only after a brief heat shock that mimics passing flames, while soil moulds ''Talaromyces

''Talaromyces'' is a genus of fungi in the family Trichocomaceae. Described in 1955 by American mycologist Chester Ray Benjamin, species in the genus form soft, cottony fruit bodies ( ascocarps) with cell walls made of tightly interwoven hyphae ...

'' and '' Neosartorya'' withstand pasteurisation-level heat—ascospores of '' Talaromyces macrosporus'' survive 100 minutes at —and germinate once competitors are killed. High-pressure processing (600 MPa, 70 °C) likewise activates a fraction of these spores; survivors germinate synchronously. Other species wait for chemical or mechanical signals: the volatile substance 1-octen-3-ol

1-Octen-3-ol, octenol for short and also known as mushroom alcohol, is a chemical that attracts biting insects such as mosquitoes. It is contained in human breath and sweat, and it is believed that insect repellent DEET works by blocking the i ...

released by packed spores inhibits germination until air flow disperses it, and thick-walled truffle spores may need abrasion or passage through an animal gut before growth can begin.

Once the wall re-hydrates the germination sequence unfolds rapidly. Trehalose, its oligosaccharide derivatives and mannitol dissolve, lowering cytoplasmic viscosity and fuelling the first ATP burst; the spore swells as the wall softens, then a germ pore or slit opens and a germ tube emerges. Growth patterns differ: tropical lichens show random, bipolar or segmental tube formation; heat-activated ''Neurospora'' spores shoot a short tube, pause, then resume hyphal extension; yeasts such as '' Dipodascus'' and '' Taphrina'' may bud secondary propagules directly from the primary ascospore. Under favourable conditions a visible mycelium

Mycelium (: mycelia) is a root-like structure of a fungus consisting of a mass of branching, thread-like hyphae. Its normal form is that of branched, slender, entangled, anastomosing, hyaline threads. Fungal colonies composed of mycelium are fo ...

can arise within one or two days.

Role in fungal life cycles

The ascospore is more than a reproductive cell: it is a compact "seed' that packages a recombined haploid genome, protective wall layers, and energy reserves in a form built to travel and to wait. Meiosis inside the ascus shuffles parental chromosomes, so every spore leaves the fruit-body with a unique genotype, giving populations the raw material for adaptation whenever those spores outcross with compatible partners. Because the spore is often the only structure that can detach from the feeding mycelium and survive environmental stress, its formation marks the real start of the next fungal generation. Mobility takes several forms. Many filamentous ascomycetes hurl spores clear of the substrate; dung dwellers such as '' Podospora'' and '' Triangularia'' regularly shoot them tens of centimetres beyond the manure pile so grazing animals carry the fungus farther. Subterranean truffles invert the strategy: their fragrant ascocarps entice mammals whose chewing ruptures the asci, and the thick-walled spores pass intact through the gut to be deposited in new territory. On bare rock faces lichens release showers of minute, colourless spores; sheer numbers compensate for the added requirement of meeting a suitable photobiont before a new thallus can form.

Dormancy allows the same spores to bridge seasons or catastrophes. In apple orchards, ''

Mobility takes several forms. Many filamentous ascomycetes hurl spores clear of the substrate; dung dwellers such as '' Podospora'' and '' Triangularia'' regularly shoot them tens of centimetres beyond the manure pile so grazing animals carry the fungus farther. Subterranean truffles invert the strategy: their fragrant ascocarps entice mammals whose chewing ruptures the asci, and the thick-walled spores pass intact through the gut to be deposited in new territory. On bare rock faces lichens release showers of minute, colourless spores; sheer numbers compensate for the added requirement of meeting a suitable photobiont before a new thallus can form.

Dormancy allows the same spores to bridge seasons or catastrophes. In apple orchards, ''Venturia inaequalis

''Venturia inaequalis'' is an ascomycota, ascomycete fungus that causes the apple scab disease.

Systematics

''Venturia inaequalis'' anamorphs have been described under the names ''Fusicladium dendriticum'' and ''Spilocaea pomi''. Whether ''V. in ...

'' survives winter as asci on fallen leaves and launches spores with the first spring rain, providing the primary inoculum of each epidemic. Fire-adapted moulds such as ''Neurospora

''Neurospora'' is a genus of Ascomycete fungi. The genus name, meaning "nerve spore" refers to the characteristic striations on the spores that resemble axons.

The best known species in this genus is '' Neurospora crassa'', a common model organ ...

'' keep a soil seed-bank of heat-resistant spores that germinate en masse after a burn and rapidly colonise the charred wood. Light, melanised spores of saprobes like ''Chaetomium

''Chaetomium'' is a genus of fungi in the Chaetomiaceae family. It is a dematiaceous (dark-walled) Mold (fungus), mold normally found in soil, air, cellulose and plant debris. According to the ''Dictionary of the Fungi'' (10th edition, 2008), th ...

'' and ''Xylaria

''Xylaria'' is a genus of ascomycetous fungi commonly found growing on dead wood. The name comes from the Greek ''xýlon'' meaning ''wood'' (see xylem).

'Outline of Fungi and fungus-like taxa' by Wijayawardene et al. lists up to (ca. 571) spe ...

'' tolerate high-altitude transport; atmospheric surveys recover them thousands of kilometres from land, showing how they seed distant ecosystems and help homogenise fungal floras on a continental scale.

Soil and sediment spore banks

Permanent 'spore banks' parallel the seed banks of plants: vast reserves of dormant ascospores accumulate in substrates and germinate only when conditions turn favourable. Incalcareous

Calcareous () is an adjective meaning "mostly or partly composed of calcium carbonate", in other words, containing lime (mineral), lime or being chalky. The term is used in a wide variety of Science, scientific disciplines.

In zoology

''Calcare ...

truffle orchards, for example, systematic post-season digs show that roughly 30–40 % of black truffle (''Tuber melanosporum

''Tuber melanosporum'', called the black truffle, Périgord truffle or French black truffle, is a species of truffle native to Southern Europe. It is one of the most expensive edible fungi in the world. In 2013, the truffle cost between 1,000 a ...

'') ascocarps remain undetected by foragers or animals; their thick-walled spores persist in the upper of soil and form a standing inoculum that can span multiple years. Similar long-term reservoirs occur in aquatic settings: metabarcoding of a 10.5-kyr sediment core from Lake Lielais Svētiņu (Latvia) recovered diverse Ascomycota ITS sequences, including coprophilous and saprotrophic taxa, showing that ascospores are routinely incorporated into lacustrine sediments and can survive burial over millennial timescales before re-entry into the water column by mixing.

Diversity across Ascomycota

conidium

A conidium ( ; : conidia), sometimes termed an asexual chlamydospore or chlamydoconidium (: chlamydoconidia), is an Asexual reproduction, asexual, non-motility, motile spore of a fungus. The word ''conidium'' comes from the Ancient Greek word f ...

-like propagules before dehiscence. '' Cordyceps'' takes a different route: each of its eight primary, filiform spores fragments into roughly 100 parts, so a single stroma carrying roughly 800 perithecia may disseminate more than 60 million infectious units—an output that compensates for scarce insect hosts.

Size, septation and wall architecture broaden that diversity still further. Yeasts such as '' Eremothecium'' release spheroidal spores barely 1 μm across, whereas certain ''Neurospora

''Neurospora'' is a genus of Ascomycete fungi. The genus name, meaning "nerve spore" refers to the characteristic striations on the spores that resemble axons.

The best known species in this genus is '' Neurospora crassa'', a common model organ ...

'' relatives exceed 200 μm. The ancestral state is aseptate and persists in Eurotiomycetes

Eurotiomycetes is a large class of ascomycetes with cleistothecial ascocarps within the subphylum Pezizomycotina, currently containing around 3810 species according to the Catalogue of Life. It is the third largest lichenized class, with more th ...

(e.g. ''Aspergillus

' () is a genus consisting of several hundred mold species found in various climates worldwide.

''Aspergillus'' was first catalogued in 1729 by the Italian priest and biologist Pier Antonio Micheli. Viewing the fungi under a microscope, Miche ...

'', ''Penicillium

''Penicillium'' () is a genus of Ascomycota, ascomycetous fungus, fungi that is part of the mycobiome of many species and is of major importance in the natural environment, in food spoilage, and in food and drug production.

Some members of th ...

''), but many Dothideomycetes

Dothideomycetes is the largest and most diverse class of ascomycete fungi. It comprises 11 orders 90 families, 1,300 genera and over 19,000 known species.

Wijayawardene et al. in 2020 added more orders to the class.

Traditionally, most of it ...

and lichen-forming Lecanoromycetes insert one or many cross-walls. Some '' Graphis'' species discharge long, multiseptate needles, whereas '' Diploschistes'' and related genera form muriform spores partitioned in both directions; these dark "megalospores", often more than 400 × 50 μm, have evolved independently in several families and are thought to strengthen the wall while compartmentalising nutrients. In many Pleosporales

The Pleosporales is the largest order (biology), order in the fungal class Dothideomycetes. By a 2008 estimate, it contained 23 family (biology), families, 332 genera and more than 4700 species. The majority of species are saprobes on decaying pl ...

the two cells of a thick-septate, brown spore are unequal, with a swollen distal cell and a smaller, darker basal cell.

Programmed attrition adds another layer of complexity. In '' Coniochaeta tetraspora'' half the eight spores self-destruct, leaving a fertile four-spored ascus, while "spore-killer" drive elements in '' Podospora'', ''Neurospora

''Neurospora'' is a genus of Ascomycete fungi. The genus name, meaning "nerve spore" refers to the characteristic striations on the spores that resemble axons.

The best known species in this genus is '' Neurospora crassa'', a common model organ ...

'' and other genera bias survival so only nuclei bearing the killer allele

An allele is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or Locus (genetics), locus, on a DNA molecule.

Alleles can differ at a single position through Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), ...

remain, reshaping population genetics

Population genetics is a subfield of genetics that deals with genetic differences within and among populations, and is a part of evolutionary biology. Studies in this branch of biology examine such phenomena as Adaptation (biology), adaptation, s ...

and hastening reproductive isolation

The mechanisms of reproductive isolation are a collection of evolutionary mechanisms, ethology, behaviors and physiology, physiological processes critical for speciation. They prevent members of different species from producing offspring, or ensu ...

. Life-style correlates reinforce these trends: cup fungi (Pezizomycetes

Pezizomycetes are a class of fungi within the division Ascomycota.