Xiphodon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Xiphodon'' is the

In 1873,

In 1873,

''Xiphodon'' is the

''Xiphodon'' is the

Both ''Xiphodon'' and ''Dichodon'' display complete sets of 3 three

Both ''Xiphodon'' and ''Dichodon'' display complete sets of 3 three

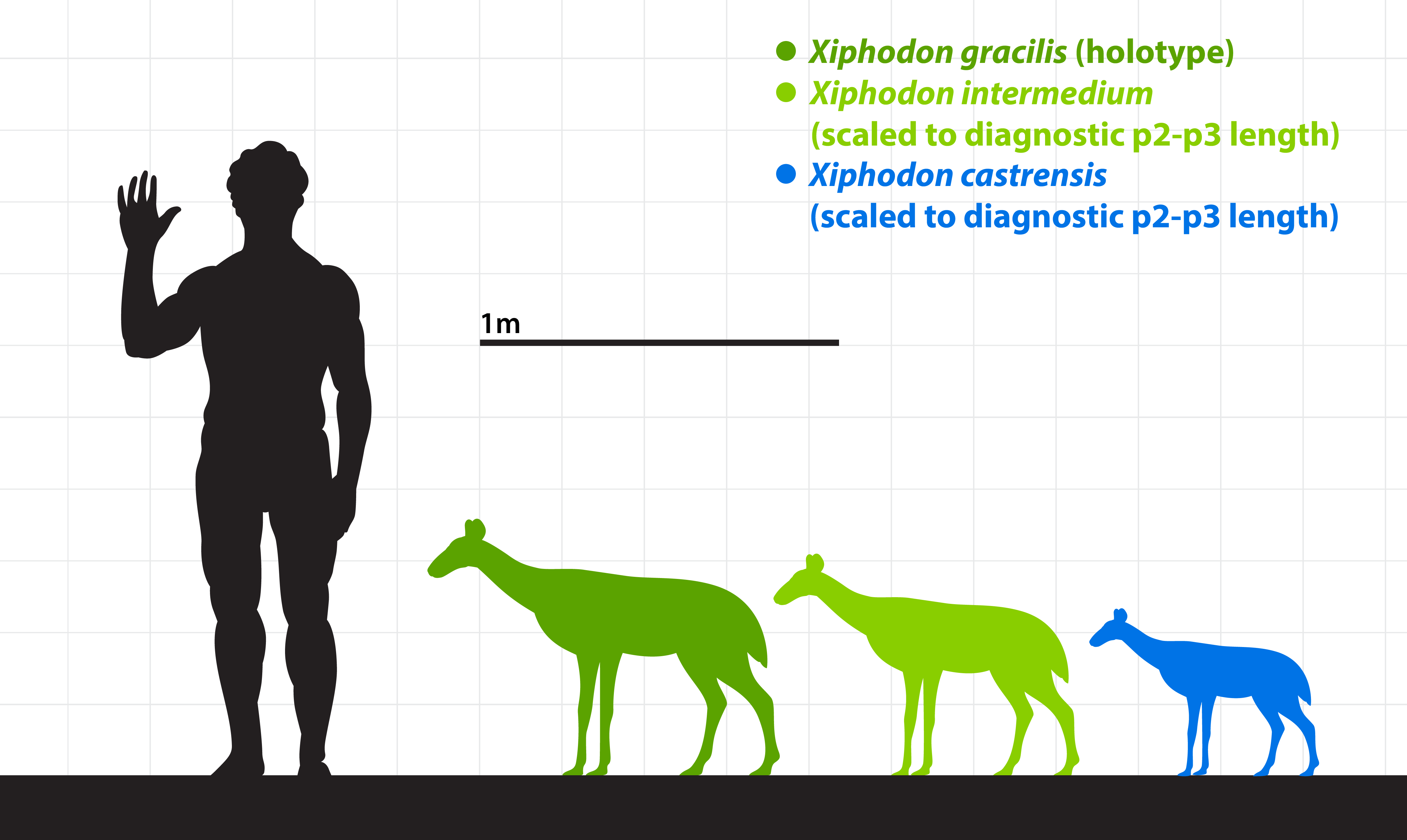

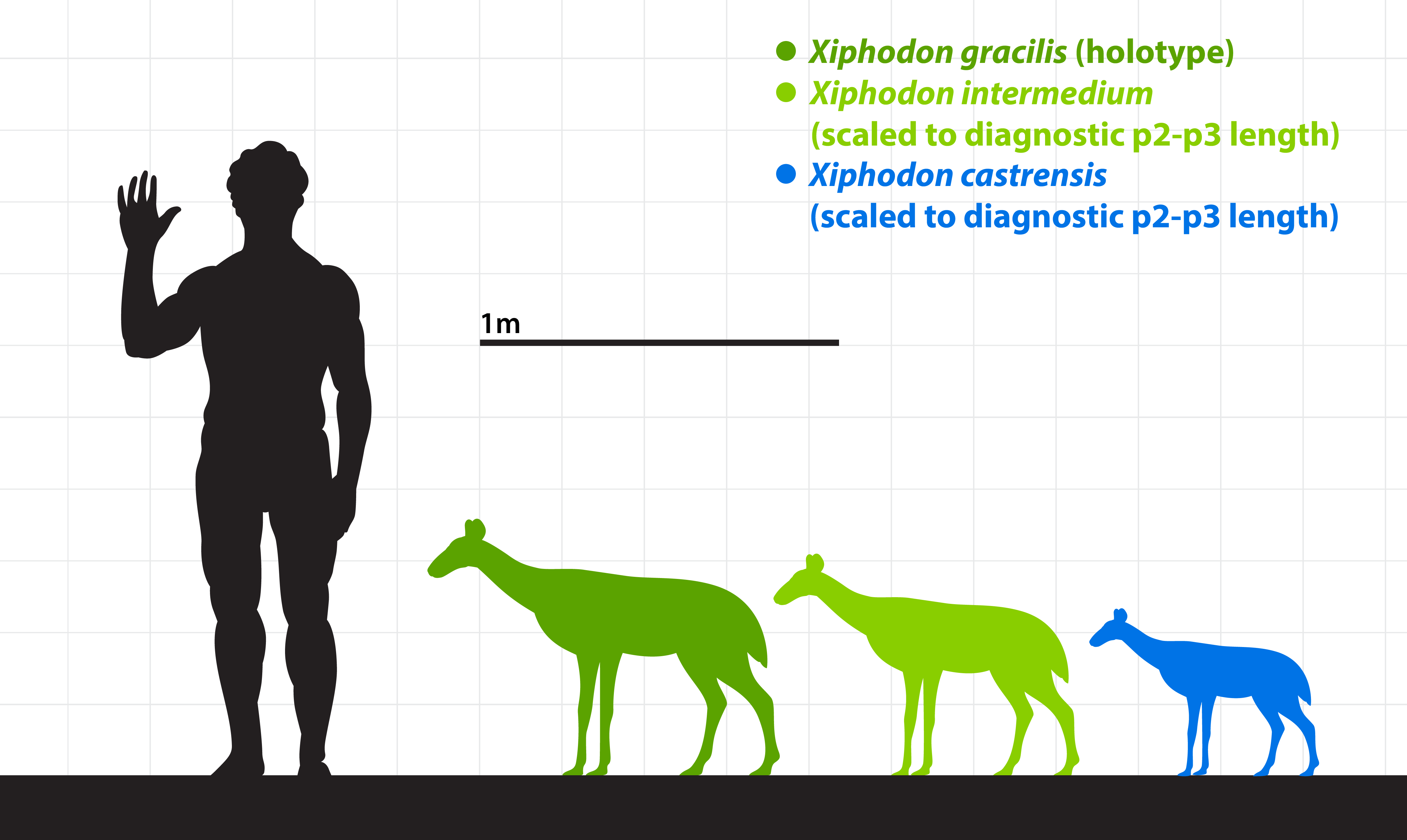

The Xiphodontidae is characterized by its species being very small to medium in size. Speciose xiphodonts such as ''Dichodon'' and ''Haplomeryx'' tended to display evolutionary increases in size. Species belonging to ''Xiphodon'' are diagnosed as being medium-sized artiodactyls. The basal species ''X. castrensis'' is the smallest of the genus followed by ''X. intermedium'' with slightly larger dental measurements. The latest species ''X. gracilis'' was the largest of the three. Sudre pointed out that the size trends point towards evolutionary increases in size.

The estimated body mass of ''X. intermedium'' has been calculated by Helder Gomes Rodrigues et al. in 2019 based on an astragalus from the

The Xiphodontidae is characterized by its species being very small to medium in size. Speciose xiphodonts such as ''Dichodon'' and ''Haplomeryx'' tended to display evolutionary increases in size. Species belonging to ''Xiphodon'' are diagnosed as being medium-sized artiodactyls. The basal species ''X. castrensis'' is the smallest of the genus followed by ''X. intermedium'' with slightly larger dental measurements. The latest species ''X. gracilis'' was the largest of the three. Sudre pointed out that the size trends point towards evolutionary increases in size.

The estimated body mass of ''X. intermedium'' has been calculated by Helder Gomes Rodrigues et al. in 2019 based on an astragalus from the

The Xiphodontidae is a selenodont artiodactyl group in western Europe, meaning that the family was likely adapted for

The Xiphodontidae is a selenodont artiodactyl group in western Europe, meaning that the family was likely adapted for

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and  ''Xiphodon'' made its earliest known appearance in MP16 based on the locality of Robiac in France as ''X. castrensis''. The species is restricted to MP16 localities. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (

''Xiphodon'' made its earliest known appearance in MP16 based on the locality of Robiac in France as ''X. castrensis''. The species is restricted to MP16 localities. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (

The next species of ''Xiphodon'' to appear in the fossil record was ''X. intermedium'' of MP17a, where it is exclusive to. After a brief fossil record gap in MP17b, the latest species to have appeared was ''X. gracilis'' by MP18. The xiphodont largely coexisted with the same artiodactyl families as well as the Palaeotheriidae within western Europe, although the Cainotheriidae and the derived anoplotheriids ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' all made their first fossil record appearances by MP18. In addition, several migrant mammal groups had reached western Europe by MP17a-MP18, namely the

The next species of ''Xiphodon'' to appear in the fossil record was ''X. intermedium'' of MP17a, where it is exclusive to. After a brief fossil record gap in MP17b, the latest species to have appeared was ''X. gracilis'' by MP18. The xiphodont largely coexisted with the same artiodactyl families as well as the Palaeotheriidae within western Europe, although the Cainotheriidae and the derived anoplotheriids ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' all made their first fossil record appearances by MP18. In addition, several migrant mammal groups had reached western Europe by MP17a-MP18, namely the

The Grande Coupure event during the latest Eocene to earliest Oligocene (MP20-MP21) is one of the largest and most abrupt faunal turnovers in the Cenozoic of Western Europe and coincident with

The Grande Coupure event during the latest Eocene to earliest Oligocene (MP20-MP21) is one of the largest and most abrupt faunal turnovers in the Cenozoic of Western Europe and coincident with

type genus

In biological taxonomy, the type genus (''genus typica'') is the genus which defines a biological family and the root of the family name.

Zoological nomenclature

According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, "The name-bearin ...

of the extinct Palaeogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

family Xiphodontidae

Xiphodontidae is an extinct family (biology), family of herbivorous even-toed ungulates (order (biology), order Artiodactyla), endemic to Europe during the Eocene 40.4—33.9 million years ago, existing for about 7.5 million years. ''P ...

. It, like other xiphodonts, was endemic to Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

and lived from the Middle Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

up to the earliest Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

. Fossils from Montmartre

Montmartre ( , , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement of Paris, 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Rive Droite, Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for its a ...

in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, France that belonged to ''X. gracilis'' were first described by the French naturalist Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

in 1804. Although he assigned the species to ''Anoplotherium

''Anoplotherium'' is the type genus of the extinct Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyl family Anoplotheriidae, which was endemic to Western Europe. It lived from the Late Eocene to the earliest Oligocene. It was the fifth fossil mammal genus to be ...

'', he recognized that it differed from ''A. commune'' by its dentition and limb bones, later moving it to its own subgenus in 1822. ''Xiphodon'' was promoted to genus rank by other naturalists in later decades. It is today defined by the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

''X. gracilis'' and two other species, ''X. castrensis'' and ''X. intermedium''.

Literally meaning "sword tooth" in Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

, ''Xiphodon'' had specialized bladelike selenodont

Selenodont teeth are the type of molars and premolars commonly found in ruminant herbivores. They are characterized by low crowns, and crescent-shaped cusps when viewed from above (crown view).

The term comes from the Ancient Greek roots (, ' ...

dentition, with its brachyodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone tooth ...

(low-crowned) incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s, canines, and premolars

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mout ...

having sharp edges for cutting through higher vegetation such as leaves and shrubs. It also retained primitive molars compared to its relative '' Dichodon'', indicating different dietary specializations. ''Xiphodon'' is also the only xiphodontid to be known from postcranial fossils. Its skull morphology, combined with slender and elongated limbs, suggest similar behaviours to North American Palaeogene camelid

Camelids are members of the biological family (biology), family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant taxon, extant members of this group are: dromedary, dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bac ...

s such as ''Poebrotherium

''Poebrotherium'' ( ) is an extinct genus of camelid, endemic to North America. They lived from the Eocene to Miocene epochs, 46.3—13.6 mya, existing for approximately .

Discovery and history

''Poebrotherium'' was first named by scientist J ...

'', including cursoriality

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often ...

(running adaptations). However, the full extent of its behaviour and evolutionary relationships remain uncertain, and its resemblances to camelids are probably an instance of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

.

''Xiphodon'' lived in western Europe back when it was an archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

that was isolated from the rest of Eurasia, meaning that it lived in an environment with various other endemic faunas. The xiphodont made its first appearance in the Middle Eocene shortly before a shift towards drier but still subhumid conditions, which led to increasingly abrasive plants. Species of ''Xiphodon'' were relatively small with the second-appearing species ''X. intermedium'' having an estimated weight of . ''X. gracilis'' was the last and largest species within the genus in an evolutionary size increase trend.

It and other xiphodont genera went extinct by the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

* Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Ar ...

extinction/faunal turnover event, coinciding with shifts towards further glaciation and seasonality plus dispersals of Asian immigrant faunas into western Europe. The causes of its extinction are attributed to negative interactions with immigrant faunas (resource competition, predation), environmental turnover from climate change, or some combination of the two.

Taxonomy

Research history

Early history

In 1804, the French naturalistGeorges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

established multiple fossil species as belonging to the genus ''Anoplotherium

''Anoplotherium'' is the type genus of the extinct Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyl family Anoplotheriidae, which was endemic to Western Europe. It lived from the Late Eocene to the earliest Oligocene. It was the fifth fossil mammal genus to be ...

'' other than ''A. commune''. One of the species he named was ''A. medium'', which he said had slender, elongated, and didactyl (two-toed) feet. He thought that ''Anoplotherium'' had didactyl hooves instead of tridactyl (three-toed) hooves, which would have separated it from the other " pachyderm" ''Palaeotherium

''Palaeotherium'' is an extinct genus of Equoidea, equoid that lived in Europe and possibly the Middle East from the Middle Eocene to the Early Oligocene. It is the type genus of the Palaeotheriidae, a group exclusive to the Paleogene, Palaeogen ...

''. Based on the hooves and dentition, he concluded that ''Anoplotherium'' was similar to ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s or camelid

Camelids are members of the biological family (biology), family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant taxon, extant members of this group are: dromedary, dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bac ...

s. In 1807, Cuvier gave further elaboration to his thoughts on the limb bones, suggesting that it superficially resembles those of llama

The llama (; or ) (''Lama glama'') is a domesticated South American camelid, widely used as a List of meat animals, meat and pack animal by Inca empire, Andean cultures since the pre-Columbian era.

Llamas are social animals and live with ...

s. He explained that the third phalanx

The phalanx (: phalanxes or phalanges) was a rectangular mass military formation, usually composed entirely of heavy infantry armed with spears, pikes, sarissas, or similar polearms tightly packed together. The term is particularly used t ...

of ''A. medium'' differed from those of llamas by its slightly larger proportions. He put forward his argument that because its third phalanx more closely resembled those of ruminants, it was more closely related to the mammal group than ''A. commune'' was to them. Cuvier also said that other postcranial morphologies of the femoral head

The femoral head (femur head or head of the femur) is the highest part of the thigh bone (femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the ...

and tibia

The tibia (; : tibiae or tibias), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two Leg bones, bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outsi ...

more closely resembled those of ruminants than those of camel

A camel (from and () from Ancient Semitic: ''gāmāl'') is an even-toed ungulate in the genus ''Camelus'' that bears distinctive fatty deposits known as "humps" on its back. Camels have long been domesticated and, as livestock, they provid ...

s. He attributed damaged lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe t ...

to ''A. medium'' in 1808.

Cuvier published his drawings of skeletal reconstructions of two species of ''Anoplotherium'' in 1812 based on known fossil remains including ''A. medium''. He noted that he had no evidence for torso

The torso or trunk is an anatomical terminology, anatomical term for the central part, or the core (anatomy), core, of the body (biology), body of many animals (including human beings), from which the head, neck, limb (anatomy), limbs, tail an ...

or tail bones of ''A. medium'' but that he had fossils of its skull, neck, tibia, and tarsus bone, adding to the hind foot evidence that he described years prior. He stated that in contrast to the more robust ''A. commune'', ''A. medium'' was more gracile in form and therefore would have been built for cursoriality similar to extant ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s such as gazelle

A gazelle is one of many antelope species in the genus ''Gazella'' . There are also seven species included in two further genera; '' Eudorcas'' and '' Nanger'', which were formerly considered subgenera of ''Gazella''. A third former subgenus, ' ...

s or roe deer. He hypothesized, therefore, that unlike ''A. commune'' which he thought had semi-aquatic habits, ''A. medium'' could not have lived in marshes or ponds. Instead, he said, it would have grazed on herbs and shrubs on dry lands and had more "timid" behaviours not unlike gracile ruminants. Cuvier also proposed that it probably did not have a long tail unlike ''A. commune'' and that it had mobile ears like deer for hearing danger in advance. ''A. medium'', according to the naturalist, had short fur and probably did not ruminate.

In 1822, Cuvier established the subgenus ''Xiphodon'' for the genus ''Anoplotherium'' and changed the species name ''Anoplotherium medium'' to ''Xiphodon gracile'' because he felt that it was a more fitting species name. He argued that the species has a head roughly the shape plus shape of the "corinne" (an archaic term for the dorcas gazelle

The dorcas gazelle (''Gazella dorcas''), also known as the ariel gazelle, is a small and common gazelle. The dorcas gazelle stands about at the shoulder, with a head and body length of and a weight of . The numerous subspecies survive on veget ...

) with sharp snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, Rostrum (anatomy), rostrum, beak or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the n ...

s and differs from ''A. commune'' on the basis of long and sharp molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

. However, he also suggested that the two species do not differ on the genus level. It alongside other Paris Basin

The Paris Basin () is one of the major geological regions of France. It developed since the Triassic over remnant uplands of the Variscan orogeny (Hercynian orogeny). The sedimentary basin, no longer a single drainage basin, is a large sag in ...

fossil species were depicted in 1822 drawings by the French palaeontologist Charles Léopold Laurillard

Charles Léopold Laurillard (21 January 1783 – 1853) was a French zoologist and paleontologist. His father died when he was 13, but he was able continue his studies. In 1803 he moved to Paris, and the following year he met Frédéric Cuvie ...

under the direction of Cuvier, although the restorations were not as detailed as Cuvier's. The genus name ''Xiphodon'' means "sword tooth" and is a compound of the Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

words (, 'sword') and (, 'tooth').

In 1848, the French naturalist Paul Gervais

Paul Gervais (full name: François Louis Paul Gervais) (26 September 1816 – 10 February 1879) was a French palaeontologist and entomologist.

Biography

Gervais was born in Paris, where he obtained the diplomas of doctor of science and of medic ...

affirmed that ''Xiphodon'' was a distinct genus from ''Anoplotherium''. He similarly conveyed that ''X. gracile'' was slender like antelope

The term antelope refers to numerous extant or recently extinct species of the ruminant artiodactyl family Bovidae that are indigenous to most of Africa, India, the Middle East, Central Asia, and a small area of Eastern Europe. Antelopes do ...

s but was slightly smaller than dorcas gazelles. He erected the second species ''X. gelyense'' from the French commune of Saint-Gély-du-Fesc

Saint-Gély-du-Fesc (; or ) is a Communes of France, commune in the Departments of France, department of Hérault, Occitania (administrative region), Occitania, southern France.

The origin of this city is from Saint Gilles, a Christian of the 8 ...

. He also reclassified ''Hyopotamus'' (= ''Bothriodon

''Bothriodon'' (Greek: "pit" (botros), "teeth" (odontes)) is an extinct genus of anthracotheriid artiodactyl from the late Eocene to early Oligocene of Asia, Europe, and North America. It was about the size of a large pig

The pig (''Sus d ...

'') ''crispus'' into ''Xiphodon''. The validity of ''Xiphodon'' as a genus was also supported by the British naturalist Richard Owen

Sir Richard Owen (20 July 1804 – 18 December 1892) was an English biologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist and paleontology, palaeontologist. Owen is generally considered to have been an outstanding naturalist with a remarkabl ...

the same year, who also erected '' Dichodon''. Owen emended the species ''X. gracile'' and ''X. gelyense'' to ''X. gracilis'' and ''X. Gelyensis'', respectively in 1857.

''X. gracilis'' was amongst the fossil taxa depicted in the Crystal Palace Dinosaurs

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs are a series of sculptures of dinosaurs and other extinct animals in the London borough of Bromley's Crystal Palace Park. Commissioned in 1852 to accompany the Crystal Palace after its move from the Great Exhi ...

assemblage in the Crystal Palace Park

Crystal Palace Park is a park in south-east London, Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens. It was laid out in the 1850s as a pleasure ground, centred around the re-location of The Crystal Palace – the largest glass ...

in the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, open to the public since 1854 and constructed by English sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins

Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins (8 February 1807 – 27 January 1894) was an English sculptor and natural history artist renowned for his work on the life-size models of dinosaurs in the Crystal Palace Park in south London. The models, accurately ...

. Benjamin apparently either refused to acknowledge the genus name or was unaware of it, meaning that sculptures of the species were referred to as "''A. gracile''". The extant sculptures of ''A. commune'' were historically confused with "''A. gracile''", the result of both species having been listed in the earliest Crystal Palace guidebooks. An illustration of Hawkins' workshop reveals that four sculptures representing "''A. gracile''" were constructed by him, three of which vanished without any traces.

The fourth sculpture was mistaken as a ''Megaloceros giganteus

The Irish elk (''Megaloceros giganteus''), also called the giant deer or Irish deer, is an extinct species of deer in the genus ''Megaloceros'' and is one of the largest deer that ever lived. Its range extended across northern Eurasia during the ...

'' fawn and was associated with the ''Megaloceros

''Megaloceros'' (from Greek: + , literally "Great Horn"; see also Lister (1987)) is an extinct genus of deer whose members lived throughout Eurasia from the Pleistocene to the early Holocene. The type and only undisputed member of the genus ...

'' sculptures for an unknown amount of time. The sole surviving sculpture measures long from the snout to the tail and has a llama-like appearance given its long neck, small head, large eyes, robust body, camel-like nose, branched lips, and a narrow snout. The sculpture's appearance overall matches up with Cuvier's anatomical description of the species, the main inaccuracy being the reconstruction of additional small digits similar to ''A. commune''. Its design and intended representation as a herd were likely inspired by South American llama appearances and behaviours. The illustration of Hawkins' workshop implies that the ''Xiphodon gracilis'' sculptures were intended to represent a relaxed herd.

Additional species and synonyms

In 1873,

In 1873, Vladimir Kovalevsky

Vladimir Ivanovich Kovalevsky (; 10 November 1848, Balakliia, Novo-Serpukhov, Russian Empire – 2 November 1935, Leningrad, USSR) was a Russian statesman, scientist and entrepreneur. He was the author of numerous articles and works on agricultu ...

rejected Gervais' reclassification of ''Hyopotamus crispus'' (= ''Elomeryx

''Elomeryx'' is an extinct genus of artiodactyl ungulate, and is among the earliest known anthracotheres. The genus was extremely widespread, first being found in Asia in the middle Eocene, in Europe during the latest Eocene, and having spread t ...

crispus'') into ''Xiphodon''. In 1876, British naturalist William Henry Flower

Sir William Henry Flower (30 November 18311 July 1899) was an English surgeon, museum curator and comparative anatomist, who became a leading authority on mammals and especially on the primate brain. He supported Thomas Henry Huxley in an ...

expressed being unsure whether ''Dichodon'' was distinct enough from ''Xiphodon''. As he disliked the concept of having multiple closely related genera, he chose to place in ''Xiphodon'' the newly erected species ''X. platyceps''. The same year, Kovalevsky erected a newly determined smaller species that he named ''X. castrense'' after the French commune of Castres

Castres (; ''Castras'' in the Languedocian dialect, Languedocian dialect of Occitan language, Occitan) is the sole Subprefectures in France, subprefecture of the Tarn (department), Tarn Departments of France, department in the Occitania (adminis ...

. He also stated that its sharp premolar

The premolars, also called premolar Tooth (human), teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the Canine tooth, canine and Molar (tooth), molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per dental terminology#Quadrant, quadrant in ...

s justified the genus etymology "sword tooth". Gervais erected another species that he tentatively assigned to ''Xiphodon'' the same year as well, naming it ''X? tragulinum''. In 1884, the French naturalist Henri Filhol

Henri Filhol

Henri Filhol (13 May 1843 – 28 April 1902) was a French medical doctor, malacologist and naturalist born in Toulouse. He was the son of Édouard Filhol (1814-1883), curator of the Muséum de Toulouse.

After receiving his early e ...

erected the species ''X. magnum'' based on a lower jaw fossil, arguing that the species was larger than ''X. gracilis''.

The British naturalist Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

reviewed the known species of ''Dichodon'' and ''Xiphodon'' in 1885, confirming that both are distinct genera. He also reaffirmed the validities of both ''X. gracilis'' and ''X. gelyensis'' then synonymized ''Xiphodontherium'', erected previously by Filhol in 1877, with ''Xiphodon'', thus reclassifying ''Xiphodontherium secundarius'' into ''Xiphodon''. He also suggested that ''Xiphodon platyceps'' may be synonymous with ''Dacrytherium

''Dacrytherium'' (Ancient Greek: (tear, teardrop) + (beast or wild animal) meaning "tear beast") is an extinct genus of Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyls belonging to the family Anoplotheriidae. It occurred from the Middle to Late Eocene of W ...

ovinum''. He did not reference ''X. castrense'' in his catalogue. In 1886, the German palaeontologist Max Schlosser transferred "''X. gelyense''" into the newer genus '' Phaneromeryx''.

In 1910, the Swiss palaeontologist Hans Georg Stehlin

Hans Georg Stehlin (1870–1941) was a Swiss paleontologist and geologist.

Stehlin specialized in vertebrate paleontology, particularly the study of Cenozoic mammals. He published numerous scientific papers on primates and ungulates. He was presid ...

synonymized ''Xiphodontherium'' with '' Amphimeryx'', also making ''X. primaevum'' and ''X. secundarium'' synonymous with ''A. murinus'' in the process. He stated that ''X. platyceps'' was most likely synonymous with ''Dichodon cuspidatum'', considered ''X? tragulinum'' to be a dubious name, and expressed doubt that ''X. magnum'' if valid truly belongs to ''Xiphodon''. He also created the species ''X. intermedium'' based on dental measurements intermediate between the smaller ''X. castrense'' and the larger ''X. gracile''.

In 2000, Jerry J. Hooker and Marc Weidmann listed ''X. castrensis'' as an emended name for ''X. castrense''. According to Jörg Erfurt and Grégoire Métais in 2007, ''X. castrensis'' and ''X. intermedium'' lack definite differential diagnoses other than dental sizes.

Classification

''Xiphodon'' is the

''Xiphodon'' is the type genus

In biological taxonomy, the type genus (''genus typica'') is the genus which defines a biological family and the root of the family name.

Zoological nomenclature

According to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, "The name-bearin ...

of the Xiphodontidae

Xiphodontidae is an extinct family (biology), family of herbivorous even-toed ungulates (order (biology), order Artiodactyla), endemic to Europe during the Eocene 40.4—33.9 million years ago, existing for about 7.5 million years. ''P ...

, a Palaeogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

family endemic to western Europe that lived from the Middle Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

to the Early Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

(~44 Ma to 33 Ma). Like the other contemporary endemic artiodactyl families of western Europe, the evolutionary origins of the Xiphodontidae are poorly known. While ''Xiphodon'' had been thought to have appeared as early as MP10 of the Mammal Palaeogene zones based on one locality, this allocation is based on very poor fossil material. Instead, the Xiphodontidae is generally thought to have first appeared by MP14, making them the first selenodont dentition artiodactyl representatives to have appeared in the landmass along with the Amphimerycidae. More specifically, the first xiphodont representatives to appear were the genera ''Dichodon'' and ''Haplomeryx

''Haplomeryx'' is an extinct genus of Palaeogene artiodactyls belonging to the family Xiphodontidae. It was endemic to Western Europe and lived from the Middle Eocene up to the earliest Oligocene. ''Haplomeryx'' was first established as a genus ...

''. ''Dichodon'' and ''Haplomeryx'' continued to persist into the Late Eocene while ''Xiphodon'' made its first appearance by MP16. Another xiphodont '' Paraxiphodon'' is known to have occurred only in MP17a localities. The former three genera lived up to the Early Oligocene where they have been recorded to have all gone extinct as a result of the Grande Coupure faunal turnover event.

The phylogenetic relations of the Xiphodontidae as well as the Anoplotheriidae

Anoplotheriidae is an extinct family of artiodactyl ungulates. They were endemic to Europe during the Eocene and Oligocene epochs about 44—30 million years ago. Its name is derived from the ("unarmed") and θήριον ("beast"), translating ...

, Mixtotheriidae and Cainotheriidae

Cainotheriidae is an extinct family of artiodactyls known from the Late Eocene to Middle Miocene of Europe. They are mostly found preserved in karstic deposits.

These animals were small in size, and generally did not exceed in height at the s ...

have been elusive due to the selenodont

Selenodont teeth are the type of molars and premolars commonly found in ruminant herbivores. They are characterized by low crowns, and crescent-shaped cusps when viewed from above (crown view).

The term comes from the Ancient Greek roots (, ' ...

morphologies (or having crescent-shaped ridges) of the molars, which were convergent with tylopod

Tylopoda (meaning "calloused foot") is a suborder of terrestrial herbivorous even-toed ungulates belonging to the order Artiodactyla. They are found in the wild in their native ranges of South America and Asia, while Australian feral camels are ...

s or ruminants. Some researchers considered the selenodont families Anoplotheriidae, Xiphodontidae, and Cainotheriidae to be within Tylopoda due to postcranial features that were similar to the tylopods from North America in the Palaeogene. Other researchers tie them as being more closely related to ruminants than tylopods based on dental morphology. Different phylogenetic analyses

In biology, phylogenetics () is the study of the evolutionary history of life using observable characteristics of organisms (or genes), which is known as Computational phylogenetics, phylogenetic inference. It infers the relationship among organ ...

have produced different results for the " derived" (or of new evolutionary traits) selenodont Eocene European artiodactyl families, making it uncertain whether they were closer to the Tylopoda or Ruminantia. Possibly, the Xiphodontidae may have arisen from an unknown dichobunoid group, thus making its resemblance to tylopods an instance of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

.

In an article published in 2019, Romain Weppe et al. conducted a phylogenetic analysis on the Cainotherioidea within the Artiodactyla based on mandibular and dental characteristics, specifically in terms of relationships with artiodactyls of the Palaeogene. The results retrieved that the superfamily was closely related to the Mixtotheriidae and Anoplotheriidae. They determined that the Cainotheriidae, Robiacinidae, Anoplotheriidae, and Mixtotheriidae formed a clade that was the sister group to the Ruminantia while Tylopoda, along with the Amphimerycidae and Xiphodontidae split earlier in the tree. The phylogenetic tree published in the article and another work about the cainotherioids is outlined below:

In 2020, Vincent Luccisano et al. created a phylogenetic tree of the basal artiodactyls, a majority endemic to western Europe, from the Palaeogene. In one clade, the "bunoselenodont endemic European" Mixtotheriidae, Anoplotheriidae, Xiphodontidae, Amphimerycidae, Cainotheriidae, and Robiacinidae are grouped together with the Ruminantia. The phylogenetic tree as produced by the authors is shown below:

In 2022, Weppe created a phylogenetic analysis in his academic thesis regarding Palaeogene artiodactyl lineages, focusing most specifically on the endemic European families. He stated that his phylogeny was the first formal one to propose affinities of the Xiphodontidae and Anoplotheriidae. He found that the Anoplotheriidae, Mixtotheriidae, and Cainotherioidea form a clade based on synapomorphic

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to hav ...

dental traits (traits thought to have originated from their most recent common ancestor). The result, Weppe mentioned, matches up with previous phylogenetic analyses on the Cainotherioidea with other endemic European Palaeogene artiodactyls that support the families as a clade. As a result, he argued that the proposed superfamily Anoplotherioidea, composing of the Anoplotheriidae and Xiphodontidae as proposed by Alan W. Gentry and Hooker in 1988, is invalid due to the polyphyly

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which ar ...

of the lineages in the phylogenetic analysis. However, the Xiphodontidae was still found to compose part of a wider clade with the three other groups. Within the Xiphodontidae, Weppe's phylogeny tree classified ''Haplomeryx'' as a sister taxon to the clade consisting of ''Xiphodon'' plus ''Dichodon''.

Description

Skull

''Xiphodon'' is diagnosed as having an elongated skull that is convex in the upwards area leading up to theorbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

. The orbits themselves are wide open in their back areas. The muzzle (or snout) is elongated and has a rounded appearance. In the xiphodont genus also are large tympanic parts of the temporal bone and visible periotic bone

The periotic bone is the single bone that surrounds the inner ear of birds and mammals. It is formed from the fusion of the prootic, epiotic, and opisthotic bones, and in Cetacea forms a complex with the tympanic bone

The tympanic part of the ...

s. The palatine foramen are extensive in size from the I3 to P1 teeth. The mandible

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

appears to be low horizontally, giving off a rectilinear outline.

The maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

constitutes the majority of the side areas of the skull while the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

extends to the alveolar process

The alveolar process () is the portion of bone containing the tooth sockets on the jaw bones (in humans, the maxilla and the mandible). The alveolar process is covered by gums within the mouth, terminating roughly along the line of the mandibu ...

es. The nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

s are narrow and elongated, its passages barely extending over the openings of the external nostril

A nostril (or naris , : nares ) is either of the two orifices of the nose. They enable the entry and exit of air and other gasses through the nasal cavities. In birds and mammals, they contain branched bones or cartilages called turbinates ...

s and forming with it a narrow bony strip. In the back view, the snout appears to have a U-shaped outline. The snout of ''Xiphodon'' is similar to that of ''Dichodon'' but differs from it by its elongation plus rounded appearance and the maxillae constituting part of the snout being less extensive in height. The snout of ''Dichodon'' in comparison is shorter and narrower.

The hard palate

The hard palate is a thin horizontal bony plate made up of two bones of the facial skeleton, located in the roof of the mouth. The bones are the palatine process of the maxilla and the horizontal plate of palatine bone. The hard palate spans ...

for the upper mouth appears concave and has a visible premaxillary-maxillary suture extending from the outer edge of the jaw to the back. Both palatine foramen types of ''Xiphodon'' have similar proportions and positions to the palatine foramen of ''Dichodon'', but those of ''Xiphodon'' are greater in length and have different morphologies to those of ''Dichodon''.

In addition to the large and hollow tympanic bulla

The tympanic part of the temporal bone is a curved plate of bone lying below the squamous part of the temporal bone, in front of the mastoid process, and surrounding the external part of the ear canal.

It originates as a separate bone (tympanic ...

e, the ear canal

The ear canal (external acoustic meatus, external auditory meatus, EAM) is a pathway running from the outer ear to the middle ear. The adult human ear canal extends from the auricle to the eardrum and is about in length and in diameter.

S ...

has elevated edges and opens in a slanted position slightly in front of the suture of the occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...

. The squamosal bone

The squamosal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians, and birds. In fishes, it is also called the pterotic bone.

In most tetrapods, the squamosal and quadratojugal bones form the cheek series of the skull. The bone forms an ancestral ...

forms a major component of the cranial vault

The cranial vault is the space in the skull within the neurocranium, occupied by the brain.

Development

In humans, the cranial vault is imperfectly composed in newborns, to allow the large human head to pass through the birth canal. During bir ...

of ''Xiphodon''. A ridge above the external area of the ear canal extends up to the upper convex edge of the zygomatic arch

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of temporal bone, zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the ...

. The upper ear canal's morphology in ''Xiphodon'' is similar to that of the Palaeogene camelid ''Poebrotherium

''Poebrotherium'' ( ) is an extinct genus of camelid, endemic to North America. They lived from the Eocene to Miocene epochs, 46.3—13.6 mya, existing for approximately .

Discovery and history

''Poebrotherium'' was first named by scientist J ...

''. The back area of the zygomatic arches are narrow and close to the cranial vault. The mandibular fossa

The mandibular fossa, also known as the glenoid fossa in some dental literature, is the depression in the temporal bone that articulates with the mandible.

Structure

In the temporal bone, the mandibular fossa is bounded anteriorly by the arti ...

appears flat and horizontal, with a small postglenoid process

A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic.

Things called a process include:

Business and management

* Business process, activities that produce a specific s ...

(or projection) taking the shape of a spoon.

Endocast anatomy

A partial endocast of ''X. gracilis'' from theNational Museum of Natural History, France

The French National Museum of Natural History ( ; abbr. MNHN) is the national natural history museum of France and a of higher education part of Sorbonne University. The main museum, with four galleries, is located in Paris, France, within the ...

was first observed by Colette Dechaseaux in 1963, which had a visible neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, ...

. The suprasylvian sulcus (or suprasylvia) has a high position within the neocortex but may have had an even higher position within the brain. The lateral sulcus

The lateral sulcus (or lateral fissure, also called Sylvian fissure, after Franciscus Sylvius) is the most prominent sulcus (neuroanatomy), sulcus of each cerebral hemisphere in the human brain. The lateral sulcus (neuroanatomy), sulcus is a deep ...

is long and distinct, and a gyrus

In neuroanatomy, a gyrus (: gyri) is a ridge on the cerebral cortex. It is generally surrounded by one or more sulci (depressions or furrows; : sulcus). Gyri and sulci create the folded appearance of the brain in humans and other mammals.

...

in front of it appears to have been elevated. The entolateral sulcus does not appear extensive in length. The gyrus between the lateral sulcus and the entolateral sulcus is narrow compared to that between the lateral sulcus and the suprasylvia. All three sulci are distinctly deep in elevation within the neocortex, giving it a hill-like appearance. The neocortex has a similar appearance to those of Palaeogene tylopods like ''Poebrotherium''.

Dechaseaux later uncovered a large spherical flocculus

The flocculus (Latin: ''tuft of wool'', diminutive) is a small lobe of the cerebellum at the posterior border of the middle cerebellar peduncle anterior to the biventer lobule. Like other parts of the cerebellum, the flocculus is involved in moto ...

of the cerebrum

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfac ...

from the same endocast in 1967. The flocculus is separated from the cerebellar hemisphere

The cerebellum consists of three parts, a median and two lateral, which are continuous with each other, and are substantially the same in structure. The median portion is constricted, and is called the vermis, from its annulated appearance which ...

and occupies space within the petrous part of the temporal bone

The petrous part of the temporal bone is pyramid-shaped and is wedged in at the base of the skull between the sphenoid and occipital bones. Directed medially, forward, and a little upward, it presents a base, an apex, three surfaces, and three ...

within the periotic bone of the ear. It also gives off an enclosed appearance within its outer edges.

Dentition

Both ''Xiphodon'' and ''Dichodon'' display complete sets of 3 three

Both ''Xiphodon'' and ''Dichodon'' display complete sets of 3 three incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s, 1 canine

Canine may refer to:

Zoology and anatomy

* Animals of the family Canidae, more specifically the subfamily Caninae, which includes dogs, wolves, foxes, jackals and coyotes

** ''Canis'', a genus that includes dogs, wolves, coyotes, and jackals

** Do ...

, 4 premolars, and 3 molars on each half of the upper and lower jaws, consistent with the primitive placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguished ...

mammal dental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of for a total of 44 teeth. As members of the Xiphodontidae, they share both small incisors and the absences of distinct diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

ta. They are also characterized by indistinct canines in comparison to other teeth and elongated premolars. Xiphodontids additionally have molariform P4 teeth, upper molars with 4 to 5 crescent-shaped cusps, and selenodont lower molars with 4 ridges, compressed lingual cuspids, and crescent-shaped labial cuspids.

The dentition of ''Xiphodon'' is brachyodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone tooth ...

in form. Its premolars are both elongated and unspecialized while its upper molars are quadrangular in shape, display W-shaped ectolophs, and show size increases from M1 to M3. They display five cusps, four of which are crescent-shaped. The paraconule and metaconule cusps connect to the parastyle and metastyle cusps, respectively. The protocone cusp is more isolated from other cuspids and has a short preprotocrista ridge.

The third incisors resemble canines but project slightly forward and are separated from the canines by tiny diastemata. The first two other incisors are not known, but based on their round alveolar

Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* M ...

s, they would be projected slightly forward just like the third incisors. The canine of ''Xiphodon'' is premolariform with its sharpness similar to the premolars but differ from them by the smaller mesiodistal diameter and asymmetry. All three front premolars appear compressed on the labiolingual side of the teeth, with the second premolar being the most elongated of the three. They appear sharp the closer they are to the canine, with the first premolar appearing to be the sharpest as a result. The similarities of the third incisors, canines, and premolars of ''Xiphodon'' reveal that the artiodactyl had specialized bladelike dentition.

Jean Sudre in 1978 argued that ''Xiphodon'' displayed the evolutionary trend of the molars becoming more quadrangular in shape and that their selenodont forms were already present in the most basal species ''X. castrensis''.

Postcranial skeleton

''Xiphodon'' is the only member of its family for which postcranial evidence is known, primarily represented by the gypsum quarries ofMontmartre

Montmartre ( , , ) is a large hill in Paris's northern 18th arrondissement of Paris, 18th arrondissement. It is high and gives its name to the surrounding district, part of the Rive Droite, Right Bank. Montmartre is primarily known for its a ...

in the case of ''X. gracilis'' as previously described by Cuvier. The cervical vertebrae

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In saurop ...

, represented by the axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

and two proceeding vertebrae, reach nearly 70% of the total length of the skull, indicating a long neck.

The forelimbs of the xiphodont are thin and elongated. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

and ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

are more elongated than the humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

. The feet of ''Xiphodon'' have two prominent digits: digit III and digit IV. The side digits II and V are heavily reduced. As a result, ''Xiphodon'' is a didactyl, or two-toed, genus. Its side metapodial

Metapodials are long bone

The long bones are those that are longer than they are wide. They are one of five types of bones: long, short, flat, irregular and sesamoid. Long bones, especially the femur and tibia, are subjected to most of the l ...

s are reduced while the cuboid bone

In the human body, the cuboid bone is one of the seven tarsal bones of the foot.

Structure

The cuboid bone is the most lateral of the bones in the distal row of the tarsus. It is roughly cubical in shape, and presents a prominence in its infer ...

and navicular bone

The navicular bone is a small bone found in the feet of most mammals.

Human anatomy

The navicular bone in humans is one of the tarsus (skeleton), tarsal bones, found in the foot. Its name derives from the human bone's resemblance to a small ...

are not fused with each other. The long legs may have supported a high-hanging body. The postcranial characteristics of ''Xiphodon'' are thought to be similar to those of Palaeogene camelids like ''Poebrotherium'', although whether ''Xiphodon'' is more primitive or more derived in relation to the North American tylopods is unclear. The astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

originally assigned to ''Xiphodon'' is narrow plus elongated in form, its tibial groove appearing narrow but deep. The back calcaneal facet, occupying a significant portion of the astragalus' back face, is wide compared to those of ''Dacrytherium''. The calcaneum

In humans and many other primates, the calcaneus (; from the Latin ''calcaneus'' or ''calcaneum'', meaning heel; : calcanei or calcanea) or heel bone is a bone of the tarsus of the foot which constitutes the heel. In some other animals, it is t ...

appears similar to that of ''Dacrytherium'' but differs by a more elongated back tuberosity. However, the postcranial fossils were later reassigned to ''Leptotheridium

''Leptotheridium'' is an extinct genus of Palaeogene artiodactyl endemic to western Europe that lived from the Middle to Late Eocene. It was erected by the Swiss palaeontologist Hans Georg Stehlin in 1910 and contains the species ''L. lugeoni'' a ...

'' while the astragalus originally assigned to ''Dichodon'' was reclassified to ''Xiphodon''. The astragalus reassigned to ''Xiphodon'' had been described as being narrow and elongated and having a deep tibial groove.

Size

The Xiphodontidae is characterized by its species being very small to medium in size. Speciose xiphodonts such as ''Dichodon'' and ''Haplomeryx'' tended to display evolutionary increases in size. Species belonging to ''Xiphodon'' are diagnosed as being medium-sized artiodactyls. The basal species ''X. castrensis'' is the smallest of the genus followed by ''X. intermedium'' with slightly larger dental measurements. The latest species ''X. gracilis'' was the largest of the three. Sudre pointed out that the size trends point towards evolutionary increases in size.

The estimated body mass of ''X. intermedium'' has been calculated by Helder Gomes Rodrigues et al. in 2019 based on an astragalus from the

The Xiphodontidae is characterized by its species being very small to medium in size. Speciose xiphodonts such as ''Dichodon'' and ''Haplomeryx'' tended to display evolutionary increases in size. Species belonging to ''Xiphodon'' are diagnosed as being medium-sized artiodactyls. The basal species ''X. castrensis'' is the smallest of the genus followed by ''X. intermedium'' with slightly larger dental measurements. The latest species ''X. gracilis'' was the largest of the three. Sudre pointed out that the size trends point towards evolutionary increases in size.

The estimated body mass of ''X. intermedium'' has been calculated by Helder Gomes Rodrigues et al. in 2019 based on an astragalus from the University of Lyon

The University of Lyon ( , or UdL) is a university system ( ''ComUE'') based in Lyon, France. It comprises 12 members and 9 associated institutions. The 3 main constituent universities in this center are: Claude Bernard University Lyon 1, which f ...

that measured long and wide, yielding . The body mass formula based on astragali was previously established by Jean-Noël Martinez and Sudre in 1995 for Palaeogene artiodactyls, although ''Xiphodon'' was not included in the initial study.

Palaeobiology

The Xiphodontidae is a selenodont artiodactyl group in western Europe, meaning that the family was likely adapted for

The Xiphodontidae is a selenodont artiodactyl group in western Europe, meaning that the family was likely adapted for folivorous

In zoology, a folivore is a herbivore that specializes in eating leaves. Mature leaves contain a high proportion of hard-to-digest cellulose, less energy than other types of foods, and often toxic compounds.Jones, S., Martin, R., & Pilbeam, D. (1 ...

(leaf-eating) dietary habits. This was especially the case with ''Xiphodon'', which displayed specialized dentition made for feeding on leaves, tree shoots, and shrubs. ''Xiphodon'' retained the primitive trait of having molars with five cusps and shifted towards cutting dentition, while ''Dichodon'' had progressively molarized premolars for the function of grinding food, meaning that the two genera had different types of ecological specializations. Dechaseaux considered that the two xiphodontid genera may have been more derived than North American Palaeogene tylopods.

The forelimbs of ''Xiphodon'' appear to be similar to those of Palaeogene camelids, which had adaptations towards cursoriality

A cursorial organism is one that is adapted specifically to run. An animal can be considered cursorial if it has the ability to run fast (e.g. cheetah) or if it can keep a constant speed for a long distance (high endurance). "Cursorial" is often ...

. Because of the dental and postcranial similarities, ''Xiphodon'' could have been a European ecological counterpart. However, whether ''Xiphodon'' had pacing locomotion like camelids cannot be proven. Due to the lack of postcranial evidence of other xiphodonts, it is not possible to prove that their postcranial morphologies are similar to those of ''Xiphodon''.

Palaeoecology

Middle Eocene

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and Primates

Primates is an order of mammals, which is further divided into the strepsirrhines, which include lemurs, galagos, and lorisids; and the haplorhines, which include tarsiers and simians ( monkeys and apes). Primates arose 74–63 ...

(or the suborder Euprimates) appeared already by the Early Eocene, diversifying rapidly and developing dentitions specialized for folivory. The omnivorous

An omnivore () is an animal that regularly consumes significant quantities of both plant and animal matter. Obtaining energy and nutrients from plant and animal matter, omnivores digest carbohydrates, protein, fat, and fiber, and metabolize ...

forms mostly either switched to folivorous diets or went extinct by the Middle Eocene (47–37 million years ago) along with the archaic "condylarths

Condylarthra is an informal group – previously considered an order – of extinct placental mammals, known primarily from the Paleocene and Eocene epochs. They are considered early, primitive ungulates and is now largely considered to be a wast ...

". By the Late Eocene (approx. 37–33 mya), most of the ungulate form dentitions shifted from bunodont (or rounded) cusps to cutting ridges (i.e. lophs) for folivorous diets.

Land connections between western Europe and North America were interrupted around 53 Ma. From the Early Eocene up until the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

* Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Ar ...

extinction event (56–33.9 mya), western Eurasia was separated into three landmasses: western Europe (an archipelago), Balkanatolia

For some 10 million years until the end of the Eocene, Balkanatolia was an island continent or a series of islands, separate from Asia and also from Western Europe. The area now comprises approximately the modern Balkans and Anatolia. Fossil mammal ...

(in-between the Paratethys Sea

The Paratethys sea, Paratethys ocean, Paratethys realm or just Paratethys (meaning "beside Tethys"), was a large shallow inland sea that covered much of mainland Europe and parts of western Asia during the middle to late Cenozoic, from the lat ...

of the north and the Neotethys Ocean

The Tethys Ocean ( ; ), also called the Tethys Sea or the Neo-Tethys, was a prehistoric ocean during much of the Mesozoic Era and early-mid Cenozoic Era. It was the predecessor to the modern Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean Sea, and the Eurasian ...

of the south), and eastern Eurasia. The Holarctic

The Holarctic realm is a biogeographic realm that comprises the majority of habitats found throughout the continents in the Northern Hemisphere. It corresponds to the floristic Boreal Kingdom. It includes both the Nearctic zoogeographical reg ...

mammalian faunas of western Europe were therefore mostly isolated from other landmasses including Greenland, Africa, and eastern Eurasia, allowing for endemism to develop. Therefore, the European mammals of the Late Eocene (MP17–MP20 of the Mammal Palaeogene zones) were mostly descendants of endemic Middle Eocene groups.

''Xiphodon'' made its earliest known appearance in MP16 based on the locality of Robiac in France as ''X. castrensis''. The species is restricted to MP16 localities. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (

''Xiphodon'' made its earliest known appearance in MP16 based on the locality of Robiac in France as ''X. castrensis''. The species is restricted to MP16 localities. By then, it would have coexisted with perissodactyls (Palaeotheriidae

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the livin ...

, Lophiodontidae

Lophiodontidae is a family of browsing, herbivorous, mammals in the Perissodactyla suborder Ancylopoda that show long, curved and cleft claws. They lived in Southern Europe during the Eocene epoch. Previously thought to be related to tapirs, it ...

, and Hyrachyidae), non-endemic artiodactyls (Dichobunidae

Dichobunidae is an extinct family of basal artiodactyl mammals from the early Eocene to late Oligocene of North America, Europe, and Asia. The Dichobunidae include some of the earliest known artiodactyls, such as ''Diacodexis''.

Description

T ...

and Tapirulidae), endemic European artiodactyls (Choeropotamidae

Choeropotamidae, also known as Haplobunodontidae, are a family (biology), family of extinct mammal herbivores, belonging to the artiodactyls. They lived between the lower/middle Eocene and lower Oligocene (about 48 - 30 million years ago) and th ...

(possibly polyphyletic, however), Cebochoeridae, Mixtotheriidae, Anoplotheriidae, Amphimerycidae, and other members of Xiphodontidae), and primates (Adapidae

Adapidae is a family of extinct primates that primarily radiated during the Eocene epoch between about 55 and 34 million years ago.

Adapid systematics and evolutionary relationships are controversial, but there is fairly good evidence from the ...

, Omomyidae

Omomyidae is a group of early primates that radiated during the Eocene epoch between about (mya). Fossil omomyids are found in North America, Europe & Asia, making it one of two groups of Eocene primates with a geographic distribution spanning ...

). It also cooccurred with metatheria

Metatheria is a mammalian clade that includes all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. First proposed by Thomas Henry Huxley in 1880, it is a more inclusive group than the marsupials; it contains all marsupials as wel ...

ns (Herpetotheriidae

Herpetotheriidae is an extinct family of metatherians, closely related to marsupials. Species of this family are generally reconstructed as terrestrial, and are considered morphologically similar to modern opossums. They are suggested to have b ...

), rodents ( Ischyromyidae, Theridomyoidea, Gliridae), eulipotyphla

Eulipotyphla (, from '' eu-'' + '' Lipotyphla'', meaning truly lacking blind gut; sometimes called true insectivores) is an order of mammals comprising the Erinaceidae ( hedgehogs and gymnures); Solenodontidae (solenodons); Talpidae ( mole ...

ns, bats, apatotheria

Apatemyidae is an extinct family of placental mammals that took part in the first placental evolutionary radiation together with other early mammals, such as the leptictids. Their relationships to other mammal groups are controversial; a 2010 st ...

ns, carnivoraformes

Carnivoramorpha ("carnivoran-like forms") is a clade of placental mammals of clade Pan-Carnivora from mirorder Ferae, that includes the modern order Carnivora and its extinct stem-relatives.Bryant, H.N., and M. Wolson (2004“Phylogenetic Nomenc ...

(Miacidae

Miacidae ("small points") is a former paraphyletic family of extinct primitive placental mammals that lived in North America, Europe and Asia during the Paleocene and Eocene epochs, about 65–33.9 million years ago.IRMNG (2018). Miacidae Cope, ...

), and hyaenodont

Hyaenodonta ("hyena teeth") is an extinct order of hypercarnivorous placental mammals of clade Pan-Carnivora from mirorder Ferae. Hyaenodonts were important mammalian predators that arose during the early Paleocene in Europe and persisted well i ...

s (Hyainailourinae

Hyainailourinae ("hyena-like Felidae, cats") is a Paraphyly, paraphyletic subfamily of Hyaenodonta, hyaenodonts from extinct paraphyletic family Hyainailouridae. They arose during the Bartonian, Middle Eocene in Africa, and persisted well into th ...

, Proviverrinae).

Within Robiac, fossils of ''X. castrensis'' were found with those of other mammals like the herpetotheriids ''Peratherium

''Peratherium'' is a genus of metatherian mammals in the family Herpetotheriidae that lived in Europe and Africa from the Early Eocene to the Early Miocene

The Early Miocene (also known as Lower Miocene) is a sub-epoch of the Miocene epoch (ge ...

'' and ''Amphiperatherium

''Amphiperatherium'' is an extinct genus of metatherian mammal, closely related to marsupials. It ranged from the Early Eocene to the Middle Miocene in Europe. It is the most recent metatherian known from the continent.

Description

Like modern ...

'', apatemyid ''Heterohyus

''Heterohyus'' is an extinct genus of apatemyid from the early to late Eocene. A small, tree-dwelling creature with elongated fore- and middle fingers, in these regards it somewhat resembled a modern-day aye-aye.

Three skeletons have been found ...

'', nyctithere '' Saturninia'', rodents ('' Glamys'', '' Elfomys'', '' Plesiarctomys'', '' Remys''), omomyids '' Pseudoloris'' and ''Necrolemur

''Necrolemur'' is a small bodied omomyid with body mass estimations ranging from . ''Necrolemur''’s teeth feature broad basins and blunt cusps, suggesting their diet consisted of mostly Frugivore, soft fruit, though examination of microwear patt ...

'', adapid ''Adapis

''Adapis'' is an extinct adapiform primate from the Eocene of Europe. While this genus has traditionally contained five species (''A. magnus, A. bruni, A. collinsonae, A. parisiensis,'' and ''A. sudrei''), recent research has recognized at least ...

'', hyaenodonts '' Paroxyaena'' and ''Cynohyaenodon

''Cynohyaenodon'' ("dog-like ''Hyaenodon''") is an extinct paraphyletic genus of placental mammals from extinct family Hyaenodontidae that lived from the early to middle Eocene in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the North ...

'', carnivoraformes '' Paramiacis'' and '' Simamphicyon'', palaeotheres (''Palaeotherium'', '' Plagiolophus'', '' Anchilophus'', '' Leptolophus''), lophiodont ''Lophiodon

''Lophiodon'' (from , 'crest' and 'tooth') is an extinct genus of mammal related to chalicotheres. It lived in Eocene Europe , and was previously thought to be closely related to ''Hyrachyus''. ''Lophiodon'' was named and described by Georges ...

'', hyrachyid '' Chasmotherium'', cebochoerids '' Acotherulum'' and '' Cebochoerus'', choeropotamid '' Choeropotamus'', tapirulid '' Tapirulus'', anoplotheriids ''Dacrytherium'' and ''Catodontherium

''Catodontherium'' is an extinct genus of Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyl belonging to the family Anoplotheriidae. It was endemic to Western Europe and had a temporal range exclusive to the middle Eocene, although its earliest appearance depe ...

'', dichobunid '' Mouillacitherium'', robiacinid ''Robiacina'', amphimerycid '' Pseudamphimeryx'', and the other xiphodonts ''Dichodon'' and ''Haplomeryx''.

By MP16, a faunal turnover occurred, marking the disappearances of the lophiodonts and European hyrachyids as well as the extinctions of all European crocodylomorph

Crocodylomorpha is a group of pseudosuchian archosaurs that includes the crocodilians and their extinct relatives. They were the only members of Pseudosuchia to survive the end-Triassic extinction. Extinct crocodylomorphs were considerably mor ...

s except for the alligatoroid

Alligatoroidea is one of three superfamilies of crocodylians, the other two being Crocodyloidea and Gavialoidea. Alligatoroidea evolved in the Late Cretaceous period, and consists of the alligators and caimans, as well as extinct members more c ...

''Diplocynodon

''Diplocynodon'' is an extinct genus of eusuchian, either an alligatoroid crocodilian or a stem-group crocodilian, that lived during the Paleocene to Middle Miocene in Europe. Some species may have reached lengths of , while others probably did ...

''. The causes of the faunal turnover have been attributed to a shift from humid and highly tropical environments to drier and more temperate forests with open areas and more abrasive vegetation. The surviving herbivorous faunas shifted their dentitions and dietary strategies accordingly to adapt to abrasive and seasonal vegetation. The environments were still subhumid and full of subtropical evergreen forests, however. The Palaeotheriidae was the sole remaining European perissodactyl group, and frugivorous-folivorous or purely folivorous artiodactyls became the dominant group in western Europe.

Late Eocene

The next species of ''Xiphodon'' to appear in the fossil record was ''X. intermedium'' of MP17a, where it is exclusive to. After a brief fossil record gap in MP17b, the latest species to have appeared was ''X. gracilis'' by MP18. The xiphodont largely coexisted with the same artiodactyl families as well as the Palaeotheriidae within western Europe, although the Cainotheriidae and the derived anoplotheriids ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' all made their first fossil record appearances by MP18. In addition, several migrant mammal groups had reached western Europe by MP17a-MP18, namely the

The next species of ''Xiphodon'' to appear in the fossil record was ''X. intermedium'' of MP17a, where it is exclusive to. After a brief fossil record gap in MP17b, the latest species to have appeared was ''X. gracilis'' by MP18. The xiphodont largely coexisted with the same artiodactyl families as well as the Palaeotheriidae within western Europe, although the Cainotheriidae and the derived anoplotheriids ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' all made their first fossil record appearances by MP18. In addition, several migrant mammal groups had reached western Europe by MP17a-MP18, namely the Anthracotheriidae

Anthracotheriidae is a paraphyletic family of extinct, hippopotamus-like artiodactyl ungulates related to hippopotamuses and whales. The oldest genus, '' Elomeryx'', first appeared during the middle Eocene in Asia. They thrived in Africa and Eura ...

, Hyaenodontinae

Hyaenodontinae ("hyena teeth") is an extinct subfamily of predatory placental mammals from extinct family Hyaenodontidae. Fossil remains of these mammals are known from early Eocene to early Miocene deposits in Europe, Asia and North America

...

, and Amphicyonidae

Amphicyonidae is an extinct family of terrestrial carnivorans belonging to the suborder Caniformia. They first appeared in North America in the middle Eocene (around 45 mya), spread to Europe by the late Eocene (35 mya), and further spread to As ...

. In addition to snakes, frogs, and salamandrids, rich assemblage of lizards are known in western Europe as well from MP16-MP20, representing the Iguanidae

The Iguanidae is a family of lizards composed of the iguanas, chuckwallas, and their prehistoric relatives, including the widespread green iguana.

Taxonomy

Iguanidae is thought to be the sister group to the Crotaphytidae, collared lizards (fam ...

, Lacertidae

The Lacertidae are the family of the wall lizards, true lizards, or sometimes simply lacertas, which are native to Afro-Eurasia. It is a diverse family with at about 360 species in 39 genera. They represent the dominant group of reptiles found ...

, Gekkonidae

Gekkonidae (the common geckos) is the largest family of geckos, containing over 950 described species in 62 genera. The Gekkonidae contain many of the most widespread gecko species, including house geckos (''Hemidactylus''), the tokay gecko (''Ge ...

, Agamidae

Agamidae is a family containing 582 species in 64 genera of iguanian lizards indigenous to Africa, Asia, Australia, and a few locations in Southern Europe. Many species are commonly called dragons or dragon lizards.

Overview

Phylogenetically ...

, Scincidae, Helodermatidae

The Helodermatidae or beaded lizards are a small family of lizards endemic to North America today, mainly found in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in Oaxaca, the central lowlands of Chiapas, on the border of Guatemala, and in the Nentón River Valley, ...

, and Varanoidea