Trotskyism (, ) is the political ideology and branch of

Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

developed by Russian revolutionary and

intellectual

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

along with some other members of the

Left Opposition and the

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) was a political international established in France in 1938 by Leon Trotsky and his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union and the Communist International (also known as Comintern or the Third Inte ...

. Trotsky described himself as an

orthodox Marxist, a

revolutionary Marxist, and a

Bolshevik

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

–

Leninist

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

as well as a follower of

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

,

Frederick Engels,

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

,

Karl Liebknecht, and

Rosa Luxemburg

Rosa Luxemburg ( ; ; ; born Rozalia Luksenburg; 5 March 1871 – 15 January 1919) was a Polish and naturalised-German revolutionary and Marxist theorist. She was a key figure of the socialist movements in Poland and Germany in the early 20t ...

. His relations with Lenin have been a source of intense historical debate. However, on balance, scholarly opinion among a range of prominent

historians

A historian is a person who studies and writes about the past and is regarded as an authority on it. Historians are concerned with the continuous, methodical narrative and research of past events as relating to the human species; as well as the ...

and

political scientists

The following is a list of notable political scientists. Political science is the scientific study of politics, a social science dealing with systems of governance and power.

A

* Robert Abelson – Yale University psychologist and political ...

such as

E.H. Carr,

Isaac Deutscher,

Moshe Lewin,

Ronald Suny, Richard B. Day and

W. Bruce Lincoln was that Lenin’s desired “heir” would have been a

collective responsibility in which Trotsky was placed in "an important role and within which

Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

would be dramatically demoted (if not removed)".

Trotsky advocated for a

decentralized form of

economic planning

Economic planning is a resource allocation mechanism based on a computational procedure for solving a constrained maximization problem with an iterative process for obtaining its solution. Planning is a mechanism for the allocation of resources ...

,

,

elected representation of Soviet

socialist parties, mass

soviet

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

democratization

Democratization, or democratisation, is the structural government transition from an democratic transition, authoritarian government to a more democratic political regime, including substantive political changes moving in a democratic direction ...

,

the tactic of a

united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

against

far-right

Far-right politics, often termed right-wing extremism, encompasses a range of ideologies that are marked by ultraconservatism, authoritarianism, ultranationalism, and nativism. This political spectrum situates itself on the far end of the ...

parties,

cultural

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

autonomy for artistic movements,

voluntary

collectivisation, a

transitional program and socialist

internationalism. He supported founding a

vanguard party of the

proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

, and a

dictatorship of the proletariat (as opposed to the "

dictatorship of the bourgeoisie", which Marxists argue is a major component of

capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

) based on working-class self-emancipation and

council democracy. Trotsky also adhered to

scientific socialism

Scientific socialism in Marxism is the application of historical materialism to the development of socialism, as not just a practical and achievable outcome of historical processes, but the only possible outcome. It contrasts with utopian social ...

and viewed this as a conscious expression of historical processes. Trotskyists are

critical of

Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

as they oppose

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

's theory of

socialism in one country in favour of Trotsky's theory of

permanent revolution. Trotskyists criticize the

bureaucracy

Bureaucracy ( ) is a system of organization where laws or regulatory authority are implemented by civil servants or non-elected officials (most of the time). Historically, a bureaucracy was a government administration managed by departments ...

and anti-democratic current developed in the

Soviet Union under Stalin

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

.

Despite their ideological disputes, Trotsky and Lenin were close personally prior to the

London Congress of Social Democrats in 1903 and during the

First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. Lenin and Trotsky were close ideologically and personally during the

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

and its aftermath. Trotskyists and some others call Trotsky its "co-leader".

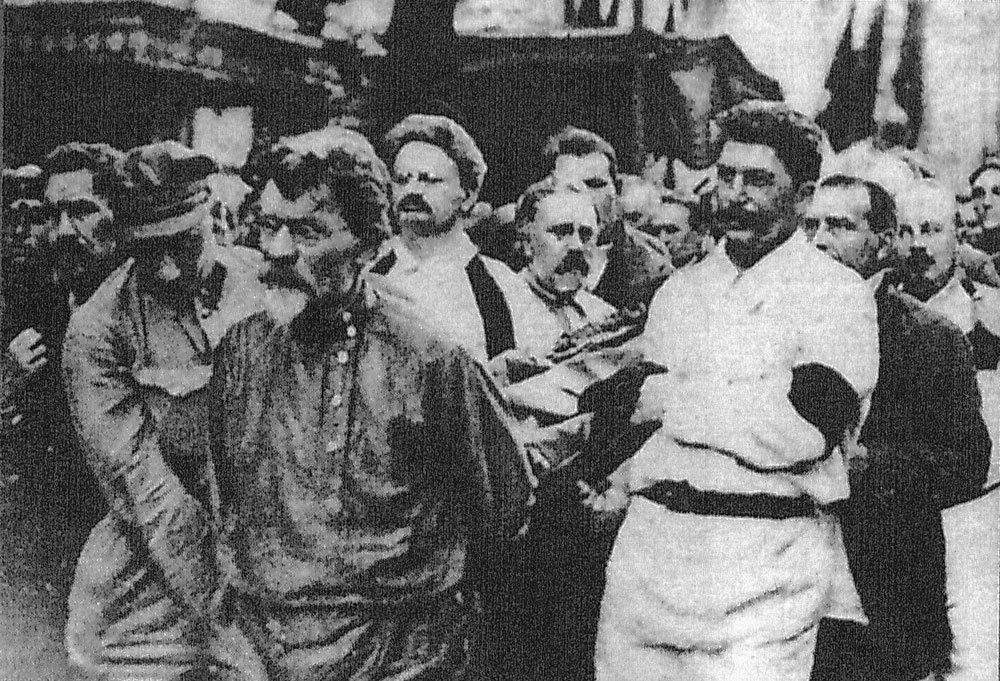

[Lenin and Trotsky were "co-leaders" of the 1917 Russian Revolution.] This was also alluded to by Rosa Luxemburg. Lenin himself never mentioned the concept of "Trotskyism" after Trotsky became a member of the Bolshevik party. Trotsky was the

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

's paramount leader in the Revolutionary period's direct aftermath. Trotsky initially opposed some aspects of

Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

but eventually concluded that unity between the

Mensheviks

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

and

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

was impossible and joined the Bolsheviks. Trotsky played a leading role with Lenin in the

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. Lenin and Trotsky were also both honorary presidents of the

Third International. Trotskyists have traditionally drawn upon

Lenin's testament

Lenin's Testament is a document alleged to have been dictated by Vladimir Lenin in late 1922 and early 1923, during and after his suffering of multiple strokes. In the testament, Lenin proposed changes to the structure of the Soviet governing bod ...

and his alliance with Trotsky in 1922–23 against the

Soviet bureaucracy as primary evidence that Lenin sought to remove Stalin from the position of

General Secretary

Secretary is a title often used in organizations to indicate a person having a certain amount of authority, Power (social and political), power, or importance in the organization. Secretaries announce important events and communicate to the org ...

. Various historians have also cited Lenin's proposal to appoint Trotsky

Vice- of the Soviet Union as further evidence that he intended Trotsky to be his successor as

head of government

In the Executive (government), executive branch, the head of government is the highest or the second-highest official of a sovereign state, a federated state, or a self-governing colony, autonomous region, or other government who often presid ...

.

In October 1927, by order of Stalin,

Trotsky was removed from power. In November of the same year, he was expelled from the

All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)

The Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU),. Abbreviated in Russian as КПСС, ''KPSS''. at some points known as the Russian Communist Party (RCP), All-Union Communist Party and Bolshevik Party, and sometimes referred to as the Soviet ...

(VKP(b)). He was exiled to

Alma-Ata (now Almaty) in January 1928 and then expelled from the

USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

in February 1929. As the head of the

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) was a political international established in France in 1938 by Leon Trotsky and his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union and the Communist International (also known as Comintern or the Third Inte ...

, Trotsky continued in exile to oppose what he termed the

degenerated workers' state in the USSR. On 20 August 1940, Trotsky was attacked in

Mexico City

Mexico City is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Mexico, largest city of Mexico, as well as the List of North American cities by population, most populous city in North America. It is one of the most important cultural and finan ...

by

Ramón Mercader, a Spanish-born

NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (, ), abbreviated as NKVD (; ), was the interior ministry and secret police of the Soviet Union from 1934 to 1946. The agency was formed to succeed the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) se ...

agent, and died the next day in a hospital. His murder is considered a political assassination. Almost all Trotskyists within the VKP(b) were executed in the

Great Purge

The Great Purge, or the Great Terror (), also known as the Year of '37 () and the Yezhovshchina ( , ), was a political purge in the Soviet Union that took place from 1936 to 1938. After the Assassination of Sergei Kirov, assassination of ...

s of 1937–1938, effectively removing all of Trotsky's internal influence in the USSR.

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

had come to power as head of the Communist Party in Ukraine, signing lists of other Trotskyists to be executed. Trotsky and the party of Trotskyists were still recognized as enemies of the USSR during Khrushchev's rule of the USSR after 1956. Trotsky's

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) was a political international established in France in 1938 by Leon Trotsky and his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union and the Communist International (also known as Comintern or the Third Inte ...

was established in the

French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

in 1938 when Trotskyists argued that the

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

or Third International had become irretrievably "lost to Stalinism" and thus incapable of leading the international working class to political power.

Definition

According to Trotsky, his programme could be distinguished from other Marxist theories by five key elements:

* Support for the strategy of

permanent revolution in opposition to the

two-stage theory of his opponents.

* Criticism of the post-1924 leadership of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and analysis of its features, after 1933, also support for

political revolution in the USSR and what Trotskyists term the

degenerated workers' states.

* Support for

social revolution

Social revolutions are sudden changes in the structure and nature of society. These revolutions are usually recognized as having transformed society, economy, culture, philosophy, and technology along with but more than just the political system ...

in the advanced capitalist countries through working-class mass action.

* Support for

proletarian internationalism

Proletarian internationalism, sometimes referred to as international socialism, is the perception of all proletarian revolutions as being part of a single global class struggle rather than separate localized events. It is based on the theory th ...

.

* Use of a transitional programme of demands that bridge between daily struggles of the working class and the maximal ideas of the socialist transformation of society.

On the

political spectrum

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different Politics, political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more Geometry, geometric Coordinate axis, axes that represent independent political ...

of

Marxism

Marxism is a political philosophy and method of socioeconomic analysis. It uses a dialectical and materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to analyse class relations, social conflict, ...

, Trotskyists are usually considered to be on the left. In the 1920s, they called themselves the

Left Opposition, although today's

left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions ...

is distinct and usually non-Bolshevik. The terminological disagreement can be confusing because different versions of a

left-right political spectrum

Left and right or left–right may refer to:

* Left and right directions, body relative directions in terms of an observer

* Left and right as designating different chirality, chiralities, independent of an observer (as in left glove, left-eyed fl ...

are used.

Anti-revisionists consider themselves the ultimate leftists on a spectrum from communism on the left to imperialist capitalism on the right. However, given that

Stalinism

Stalinism (, ) is the Totalitarianism, totalitarian means of governing and Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union (USSR) from History of the Soviet Union (1927–1953), 1927 to 1953 by dictator Jose ...

is often labelled rightist within the communist spectrum and

left communism

Left communism, or the communist left, is a position held by the left wing of communism, which criticises the political ideas and practices held by Marxism–Leninism, Marxist–Leninists and social democrats. Left communists assert positions ...

leftist, anti-revisionists' idea of the left is very different from that of left communism. Despite being Bolshevik-Leninist comrades during the

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution, social change in Russian Empire, Russia, starting in 1917. This period saw Russia Dissolution of the Russian Empire, abolish its mona ...

and

Russian Civil War

The Russian Civil War () was a multi-party civil war in the former Russian Empire sparked by the 1917 overthrowing of the Russian Provisional Government in the October Revolution, as many factions vied to determine Russia's political future. I ...

, Trotsky and Stalin became enemies in the 1920s and, after that, opposed the legitimacy of each other's forms of Leninism. Trotsky was highly

critical of the Stalinist USSR for suppressing democracy and the lack of adequate economic planning.

Overall, Trotsky and the Left-United Opposition factions advocated for rapid

industrialization

Industrialisation (British English, UK) American and British English spelling differences, or industrialization (American English, US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an i ...

, voluntary collectivisation of agriculture, and the expansion of a

worker's democracy.

Theory

Until 1905, some revolutionaries claimed that

Marx's theory of history posited that only a revolution in a European capitalist society would lead to a socialist one. According to this position, a socialist revolution could not occur in a backward, feudal country such as early 20th-century Russia when it had such a small and almost powerless capitalist class. In 1905, Trotsky formulated his theory of

permanent revolution, which later became a defining characteristic of Trotskyism.

The theory of permanent revolution addressed how such feudal regimes were to be overthrown and how socialism could establish itself, given the lack of economic prerequisites. Trotsky argued that only the working class could overthrow feudalism and win the

peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

ry's support in Russia. Furthermore, he argued that the Russian working class would not stop there. They would win their revolution against the weak capitalist class, establish a workers' state in Russia and appeal to the working class in the advanced capitalist countries worldwide. As a result, the global working class would come to Russia's aid, and socialism could develop worldwide.

According to political scientist Baruch Knei-Paz, Trotsky’s theory of “permanent revolution” was grossly misrepresented by

Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

as

defeatist and adventurist during the succession struggle when in fact Trotsky encouraged revolutions in Europe but was not at any time proposing “reckless confrontations” with the capitalist world.

Capitalist or bourgeois-democratic revolution

Revolutions in Britain in the 17th century and in France in 1789 abolished feudalism and established the essential requisites for the development of capitalism. Trotsky argued that these revolutions would not be repeated in Russia.

In ''Results and Prospects'', written in 1906, Trotsky outlines his theory in detail, arguing: "History does not repeat itself. However much one may compare the Russian Revolution with the Great French Revolution, the former can never be transformed into a repetition of the latter." In the

French Revolution of 1789, France experienced what Marxists called a "

bourgeois-democratic revolution"—a regime was established wherein the bourgeoisie overthrew the existing French feudalistic system. The bourgeoisie then moved towards establishing a regime of democratic parliamentary institutions. However, while democratic rights were extended to the bourgeoisie, they were not generally extended to a universal franchise. The freedom for workers to organize unions or to strike was not achieved without considerable struggle.

Passivity of the bourgeoisie

Trotsky argues that countries like Russia had no "enlightened, active" revolutionary

bourgeoisie

The bourgeoisie ( , ) are a class of business owners, merchants and wealthy people, in general, which emerged in the Late Middle Ages, originally as a "middle class" between the peasantry and aristocracy. They are traditionally contrasted wi ...

which could play the same role, and the working class constituted a tiny minority. By the time of the European revolutions of 1848, "the bourgeoisie was already unable to play a comparable role. It did not want and was not able to undertake the revolutionary liquidation of the social system that stood in its path to power."

The theory of permanent revolution considers that in many countries that are thought under Trotskyism to have not yet completed a bourgeois-democratic revolution, the capitalist class opposes the creation of any revolutionary situation. They fear stirring the working class into fighting for its revolutionary aspirations against their exploitation by capitalism. In Russia, the working class, although a small minority in a predominantly peasant-based society, was organised in vast factories owned by the capitalist class and into large working-class districts. During the Russian Revolution of 1905, the capitalist class found it necessary to ally with reactionary elements such as the essentially feudal landlords and, ultimately, the existing Czarist Russian state forces. This was to protect their ownership of their property—factories, banks, etc.—from expropriation by the revolutionary working class.

Therefore, according to the theory of permanent revolution, the capitalist classes of economically backward countries are weak and incapable of carrying through revolutionary change. As a result, they are linked to and rely on the feudal landowners in many ways. Thus, Trotsky argues that because a majority of the branches of industry in Russia originated under the direct influence of government measures—sometimes with the help of government subsidies—the capitalist class was again tied to the ruling elite. The capitalist class was subservient to European capital.

The incapability of the peasantry

The theory of permanent revolution further considers that the

peasantry

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasan ...

as a whole cannot take on the task of carrying through the revolution because it is dispersed in small holdings throughout the country and forms a heterogeneous grouping, including the rich peasants who employ rural workers and aspire to

landlord

A landlord is the owner of property such as a house, apartment, condominium, land, or real estate that is rented or leased to an individual or business, known as a tenant (also called a ''lessee'' or ''renter''). The term landlord appli ...

ism as well as the poor peasants who aspire to own more land. Trotsky argues: "All historical experience

..shows that the peasantry are absolutely incapable of taking up an independent political role".

The key role of the proletariat

Trotskyists differ on the extent to which this is true today. However, even the most orthodox tend to recognise in the late twentieth century a new development in the revolts of the rural poor: the self-organising struggles of the landless, along with many other struggles that in some ways reflect the militant united, organised struggles of the working class, which to various degrees do not bear the marks of class divisions typical of the heroic peasant struggles of previous epochs. However, orthodox Trotskyists today still argue that the town- and city-based working-class struggle is central to the task of a successful socialist revolution linked to these struggles of the rural poor. They argue that the working class learns of the necessity to conduct a collective struggle, for instance, in trade unions, arising from its social conditions in the factories and workplaces; and that the collective consciousness it achieves as a result is an essential ingredient of the socialist reconstruction of society.

Trotsky himself argued that only the

proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

or working class were capable of achieving the tasks of that bourgeois revolution. In 1905, the working class in Russia, a generation brought together in vast factories from the relative isolation of peasant life, saw the result of its labour as a vast collective effort, also seeing the only means of struggling against its oppression in terms of a collective effort, forming workers councils (

soviets) in the course of the revolution of that year. In 1906, Trotsky argued:

For instance, the

Putilov Factory numbered 12,000 workers in 1900 and, according to Trotsky, 36,000 in July 1917.

Although only a tiny minority in Russian society, the proletariat would lead a revolution to emancipate the peasantry and thus "secure the support of the peasantry" as part of that revolution, on whose support it will rely.

[Trotsky adds that the revolution must raise the cultural and political consciousness of the peasantry.] However, to improve their conditions, the working class must create a revolution of their own, which would accomplish the bourgeois revolution and establish a workers' state.

International revolution

Only fully developed capitalist conditions prepare the basis for socialism. According to

classical Marxism

Classical Marxism is the body of economic, philosophical, and sociological theories expounded by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in their works, as contrasted with orthodox Marxism, Marxism–Leninism, and autonomist Marxism which emerged after t ...

, a revolution in peasant-based countries such as Russia ultimately prepares the ground for capitalism's development since the liberated peasants become small owners, producers, and traders. This leads to the growth of commodity markets, from which a new capitalist class emerges.

Trotsky agreed that a new socialist state and economy in a country like Russia would not be able to hold out against the pressures of a hostile capitalist world and the internal pressures of its backward economy. Trotsky argued that the revolution must quickly spread to capitalist countries, bringing about a socialist revolution that must spread worldwide. In this way, the revolution is "permanent", moving out of necessity first, from the bourgeois revolution to the workers' revolution and from there uninterruptedly to European and worldwide revolutions.

An

internationalist outlook of permanent revolution is found in the works of

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

. The term "permanent revolution" is taken from a remark of Marx in his March 1850 Address: "it is our task", Marx said:

His biographer, Isaac Deutscher, has explicitly contrasted his support for proletarian internationalism against his opposition to revolution by

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. Militaries are typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with their members identifiable by a d ...

conquest

Conquest involves the annexation or control of another entity's territory through war or Coercion (international relations), coercion. Historically, conquests occurred frequently in the international system, and there were limited normative or ...

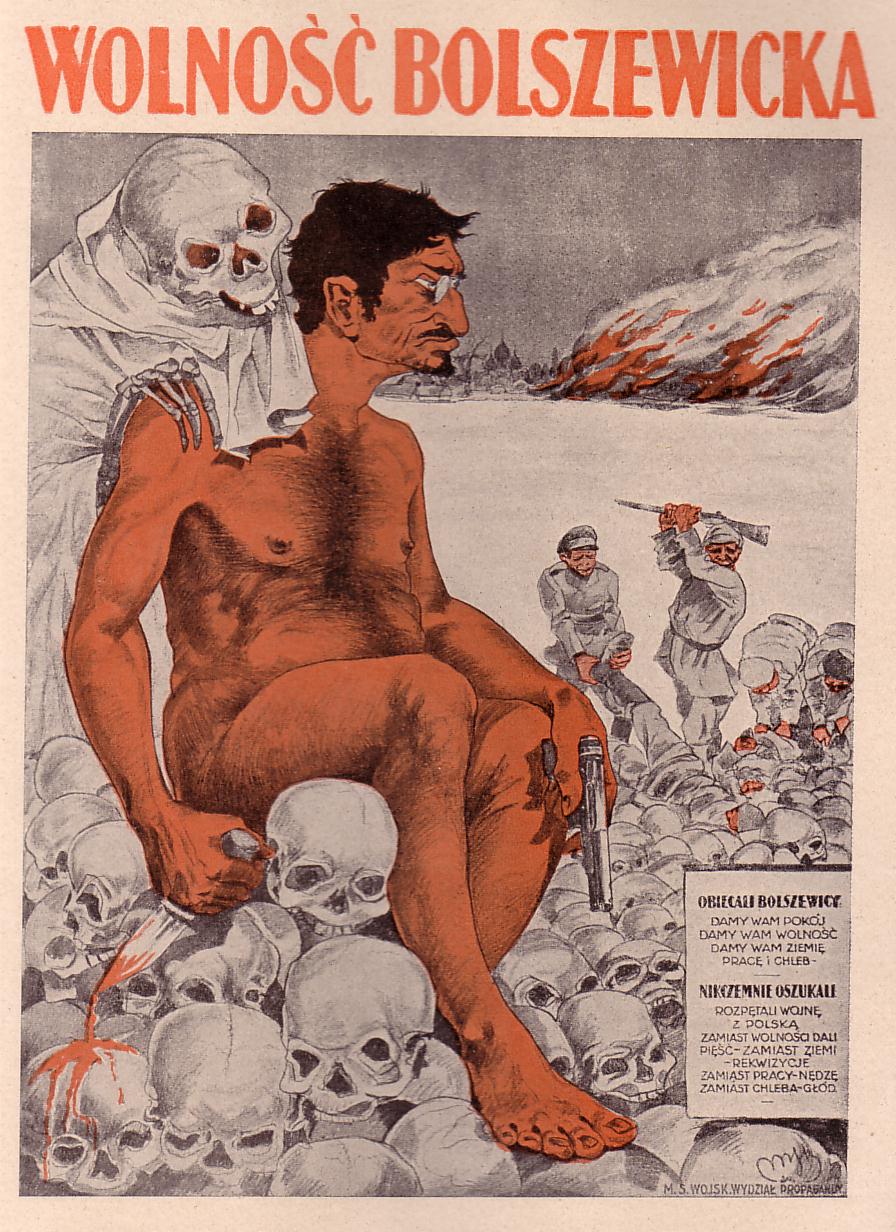

as seen with his documented opposition to the

war with Poland in 1920, proposed armistice with the

Entente and temperance with staging

anti-British revolts in the Middle East. Historian

Robert Vincent Daniels believed that the practical differences, in the domain of

international policy, between the Left Opposition and other factions had been exaggerated and he contended that Trotsky was no more prepared than other Bolshevik figures to risk

war or for the loss of

trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

Traders generally negotiate through a medium of cr ...

opportunities despite his support for

world revolution.

Socialist democracy and Workers' Control

Prior to the October Revolution, Trotsky had been part of a tendency toward

radical democracy

Radical democracy is a type of democracy that advocates the radical extension of equality and liberty. Radical democracy is concerned with a radical extension of equality and freedom, following the idea that democracy is an unfinished, inclusive, ...

which included both Left

Mensheviks

The Mensheviks ('the Minority') were a faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with Vladimir Lenin's Bolshevik faction at the Second Party Congress in 1903. Mensheviks held more moderate and reformist ...

and Left

Bolsheviks

The Bolsheviks, led by Vladimir Lenin, were a radical Faction (political), faction of the Marxist Russian Social Democratic Labour Party (RSDLP) which split with the Mensheviks at the 2nd Congress of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, ...

. His work, ''

Our Political Tasks'', published in 1904 reviewed issues related to party organisation,

mass participation and the potential dangers of

substitutionism which he foresaw in a Leninist party model. Trotsky would also assume a central role in the

1905 revolution and serve as the Chairman of the Petersburg Soviet of Workers' Delegates in which he wrote several proclamations urging for improved

economic conditions,

political rights and the use of

strike action

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to Working class, work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Str ...

against the

Tsarist regime on behalf of workers.

In 1917, he had proposed the election of a new Soviet

presidium with other

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

parties on the basis of

proportional representation

Proportional representation (PR) refers to any electoral system under which subgroups of an electorate are reflected proportionately in the elected body. The concept applies mainly to political divisions (Political party, political parties) amon ...

. On the other hand, he had accepted the ban on rival parties in Moscow during the Russian Civil War due to their opposition to the

October Revolution

The October Revolution, also known as the Great October Socialist Revolution (in Historiography in the Soviet Union, Soviet historiography), October coup, Bolshevik coup, or Bolshevik revolution, was the second of Russian Revolution, two r ...

. Yet, he also opposed the extension of the ban to the Mensheviks in

Soviet Georgia.

In 1922, Lenin allied with

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

against the party's growing

bureaucratisation and the influence of

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

. In 1923, Trotsky and a number of

Old Bolsheviks

The Old Bolsheviks (), also called the Old Bolshevik Guard or Old Party Guard, were members of the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party prior to the Russian Revolution of 1917. Many Old Bolsheviks became leading politi ...

who signed

The Declaration of 46 raised concerns to the Poliburo concerning intra-party democracy which shared similarities with Lenin's

proposed party reforms before his death. The signatories of the 46 letter expressed grievances related to the provincial conferences, party congresses and the election of committees. Separately, Trotsky would develop his views further with the publication of the ''

New Course'' in 1924.

In 1927, Trotsky and the

United Opposition had argued for the expansion of

industrial democracy with their joint platform which demanded majority representation of workers in trade union congresses including the

All-Union Congress and an increase of non-party workers to one-third of representation in these elected organs. They also supported legal protection for worker's right to criticise such as the right to make independent proposals. According to historian

Vadim Rogovin

Vadim Zakharovich Rogovin (; 10 May 1937 – 18 September 1998) was a Russian Marxist (Trotskyist) historian and sociologist, Ph.D. in philosophy, Leading Researcher at the Institute of Sociology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the auth ...

, these proposals would have developed democracy in the sphere of

production and facilitated the establishment of worker's control over economic management.

Following Stalin's consolidation of power in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

and static centralization of political power, Trotsky condemned the Soviet government's policies for lacking widespread democratic participation on the part of the population and for suppressing

workers' self-management

Workers' self-management, also referred to as labor management and organizational self-management, is a form of organizational management based on self-directed work processes on the part of an organization's workforce. Self-managed economy, ...

and democratic participation in the management of the economy. Because these authoritarian political measures were inconsistent with the organizational precepts of socialism, Trotsky characterized the Soviet Union as a deformed workers' state that would not be able to effectively transition to socialism. Ostensibly socialist states where democracy is lacking, yet the economy is largely in the hands of the state, are termed by

orthodox Trotskyist theories as

degenerated or

deformed workers' states and not socialist states.

In 1931, Trotsky

wrote a pamphlet on the

Spanish Revolution and called for the creation of worker’s juntas in emulation of

elected soviets as an expression of

working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

organisation. Trotsky stipulated the need for shared participation of the communist factions,

anarcho-syndicalists

Anarcho-syndicalism is an anarchism, anarchist organisational model that centres trade unions as a vehicle for class conflict. Drawing from the theory of libertarian socialism and the practice of syndicalism, anarcho-syndicalism sees trade uni ...

and

socialists

Socialism is an economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes the economic, political, and socia ...

.

In 1936, Trotsky argued in his work, ''

The Revolution Betrayed

''The Revolution Betrayed: What is the Soviet Union and Where is it Going?'' () is a book published in 1936 by the former Soviet leader Leon Trotsky.

The book criticized the Soviet Union's actions and development following the death of Vladimir ...

'', for the restoration of the right of criticism in areas such as

economic matters, the revitalization of

trade unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

and free elections of the

Soviet parties. Trotsky also argued that the excessive

authoritarianism

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in democracy, separation of powers, civil liberties, and ...

under Stalin had undermined the implementation of the

First five-year plan. He noted that several engineers and economists who had created the plan were themselves later put on trial as "

conscious wreckers who had acted on the instructions of a foreign power".

Polish historian and biographer,

Isaac Deutscher, viewed his inner-party reforms in 1923–24 as arguably the first act in the restoration of free Soviet institutions which the party had sought to establish in 1917 and the return of

worker's democracy which would correspond with a gradual dismantlement of the

single-party system.

At the same time, Deutscher noted that Trotsky's attitude towards democracy could be characterised as inconsistent and hesitant by opponents but this stemmed from a range of reasons such as the

ill timing after the failed revolutions in the West and controversies around party schisms.

In the ''

Transitional Program'', which was drafted in 1938 during the founding congress of the

Fourth International

The Fourth International (FI) was a political international established in France in 1938 by Leon Trotsky and his supporters, having been expelled from the Soviet Union and the Communist International (also known as Comintern or the Third Inte ...

, Trotsky reiterated the need for the legalization of the

Soviet parties and

worker's control of production.

Uneven and combined development

The concept of uneven and combined development derived from the political theories of Trotsky. This concept was developed in combination with the related theory of permanent revolution to explain the historical context of Russia. He would later elaborate on this theory to explain the specific laws of uneven development in 1930 and the conditions for a possible revolutionary scenario. According to biographer Ian Thatcher, this theory would be later generalised to "the entire history of mankind".

Political scientists Emanuele Saccarelli and Latha Varadarajan valued his theory as a "signal contribution" to the discipline of

international relations

International relations (IR, and also referred to as international studies, international politics, or international affairs) is an academic discipline. In a broader sense, the study of IR, in addition to multilateral relations, concerns al ...

. They argued his theory presented "a specific understanding of capitalist development as "uneven", insofar as it systematically featured geographically divergent "advanced" and "backward" regions" across the

world economy

The world economy or global economy is the economy of all humans in the world, referring to the global economic system, which includes all economic activities conducted both within and between nations, including production (economics), producti ...

.

Socialist culture

In ''

Literature and Revolution'', Trotsky examined aesthetic issues in relation to class and the Russian revolution. Soviet scholar Robert Bird considered his work as the "first systematic treatment of art by a Communist leader" and a catalyst for later, Marxist cultural and critical theories. He had also defended intellectual autonomy in relation to the Russian

literary movements

Literary movements are a way to divide literature into categories of similar philosophical, topical, or aesthetic features, as opposed to divisions by literary genre, genre or period. Like other categorizations, literary movements provide languag ...

and scientific theories such as

Freudian psychoanalytic theory along with

Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

’s

theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

during the succession period. However, these theories were increasingly marginalised during the Stalin era.

In ''"

Problems of Everyday Life

''Problems of Everyday Life: Creating the Foundations for A New Society in Revolutionary Russia'' or Problems of Every Day Life: And Other Writings on Culture and Science are a selection of articles and party speeches by Russian revolutionary L ...

"'', a contemporaneous book which further articulated his views on culture and science, Trotsky argued that cultural development would accentuate industrial and technical progress. He viewed both elements to be interrelated components as part of dialectical interaction in which he viewed the low level of Russian

technique

Technique or techniques may refer to:

Music

* The Techniques, a Jamaican rocksteady vocal group of the 1960s

* Technique (band), a British female synth pop band in the 1990s

* ''Technique'' (album), by New Order, 1989

* ''Techniques'' (album), by ...

and

expertise

An expert is somebody who has a broad and deep understanding and competence in terms of knowledge, skill and experience through practice and education in a particular field or area of study. Informally, an expert is someone widely recognized a ...

to be a function of cultural backwardness. According to Trotsky, Western industrial techniques and products such as the radio should not be rejected due to their status as a product of a capitalist system but rather absorbed into the Soviet socialist framework to facilitate new forms of techniques and cultural production. In this interpretation, the

transference of techniques brought new cultural changes in terms of rationalism,

efficiency

Efficiency is the often measurable ability to avoid making mistakes or wasting materials, energy, efforts, money, and time while performing a task. In a more general sense, it is the ability to do things well, successfully, and without waste.

...

, exactitude and

quality

Quality may refer to:

Concepts

*Quality (business), the ''non-inferiority'' or ''superiority'' of something

*Quality (philosophy), an attribute or a property

*Quality (physics), in response theory

*Energy quality, used in various science discipli ...

.

Trotsky would later co-author the 1938 ''

Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art'' with the endorsement of prominent artists

Andre Breton and

Diego Rivera

Diego Rivera (; December 8, 1886 – November 24, 1957) was a Mexican painter. His large frescoes helped establish the Mexican muralism, mural movement in Mexican art, Mexican and international art.

Between 1922 and 1953, Rivera painted mural ...

. Trotsky's writings on literature such as his 1923 survey which advocated tolerance, limited censorship and respect for literary tradition had strong appeal to the

New York Intellectuals.

Trotsky presented a critique of contemporary literary movements such as

Futurism

Futurism ( ) was an Art movement, artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the ...

and emphasised a need of cultural autonomy for the development of a socialist culture. According to literary critic

Terry Eagleton, Trotsky recognised "like Lenin on the need for a socialist culture to absorb the finest products of bourgeois art".

Trotsky himself viewed the proletarian culture as "temporary and transitional" which would provide the foundations for a culture above classes. He also argued that the pre-conditions for artistic creativity were economic well-being and emancipation from material constraints.

Political scientist, Baruch Knei-Paz, characterised

his view on the role of the party as transmitters of culture to the masses and raising the standards of education, as well as entry into the cultural sphere, but that the process of artistic creation in terms of language and presentation should be the domain of the practitioner. Knei-Paz also noted key distinctions between Trotsky's approach on cultural matters and

Stalin's policy in the 1930s.

Economics

Trotsky was an early proponent of economic planning since 1923 and favored an accelerated pace of industrialization.

In 1921, he had also been a prominent supporter of

Gosplan

The State Planning Committee, commonly known as Gosplan ( ), was the agency responsible for economic planning, central economic planning in the Soviet Union. Established in 1921 and remaining in existence until the dissolution of the Soviet Unio ...

as a newly established body and called for the strengthening of its formal responsibilities to support a balanced level of economic reconstruction after the Civil War. Lenin and

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

members had also proposed he served as deputy chairman with a focus on economic matters related to the either

STO, Gosplan or the Council of National Economy.

Trotsky had urged economic

decentralisation between the state,

oblast

An oblast ( or ) is a type of administrative division in Bulgaria and several post-Soviet states, including Belarus, Russia and Ukraine. Historically, it was used in the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The term ''oblast'' is often translated i ...

regions and factories to counter structural inefficiency and the problem of bureaucracy.

He had proposed the principles underlying the

N.E.P. in 1920 to the

Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

to mitigate urgent economic matters arising from war communism. He would later reproach Lenin privately about the delayed government response in 1921-1922. However, his position also differed from the majority of Soviet leaders at the time who fully supported the

New Economic policy.

Comparatively, Trotsky believed that planning and N.E.P should develop within a mixed framework until the socialist sector gradually superseded the private industry. He found allies among a circle of economic theorists and administrators which included

Evgenii Preobazhensky along

Georgy Pyatakov, deputy chairman of the

Council of the National Economy and had more broadly the support of many party

intellectuals

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking, research, and Human self-reflection, reflection about the nature of reality, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative problems. Coming from the wor ...

.

Trotsky had specified the need for the "overall guidance in planning i.e. the systematic co-ordination of the fundamental sectors of the state economy in the process of adapting to the present market" and urged for a national plan alongside currency stabilization. He also rejected the Stalinist conception of industrialisation which favoured

heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

. Rather, he proposed the use of

foreign trade

International trade is the exchange of Capital (economics), capital, goods, and Service (economics), services across international borders or territories because there is a need or want of goods or services. (See: World economy.)

In most countr ...

as an accelerator and to direct investments by means of a system of comparative

coefficients

In mathematics, a coefficient is a multiplicative factor involved in some term of a polynomial, a series, or any other type of expression. It may be a number without units, in which case it is known as a numerical factor. It may also be a ...

.

Trotsky and the Left Opposition developed a number of economic proposals in response to the

scissor crisis which had undermined relations between the workers and peasants in 1923–1924. This included a

progressive tax

A progressive tax is a tax in which the tax rate increases as the taxable amount increases. The term ''progressive'' refers to the way the tax rate progresses from low to high, with the result that a taxpayer's average tax rate is less than the ...

on the wealthier sections of populations such as the

kulak

Kulak ( ; rus, кула́к, r=kulák, p=kʊˈɫak, a=Ru-кулак.ogg; plural: кулаки́, ''kulakí'', 'fist' or 'tight-fisted'), also kurkul () or golchomag (, plural: ), was the term which was used to describe peasants who owned over ...

s and

NEPmen alongside an equilibrium of the import-export balance to access accumulated reserves to purchase machinery from abroad to increase the pace of industrialization. The policy was later adopted by members of the United Opposition which also advocated a programme of rapid industrialization during the debates of 1924 and 1927. The United Opposition proposed a progressive tax on wealthier peasants, the encouragement of

agricultural cooperatives

An agricultural cooperative, also known as a farmers' co-op, is a producer cooperative in which farmers pool their resources in certain areas of activities.

A broad typology of agricultural cooperatives distinguishes between agricultural servic ...

and the formation of collective farms on a voluntary basis.

Trotsky as president of the

electrification

Electrification is the process of powering by electricity and, in many contexts, the introduction of such power by changing over from an earlier power source. In the context of history of technology and economic development, electrification refe ...

commission along with members of the Opposition bloc had also put forward an electrification plan which involved the construction of the

hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other Renewable energ ...

Dnieprostroi dam. According to historian

Sheila Fitzpatrick

Sheila Mary Fitzpatrick (born June 4, 1941) is an Australian historian, whose main subjects are history of the Soviet Union and history of modern Russia, especially the Stalin era and the Great Purges, of which she proposes a " history from b ...

, the scholarly consensus was that Stalin appropriated the position of the Left Opposition on such matters as

industrialisation

Industrialisation ( UK) or industrialization ( US) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive reorganisation of an economy for th ...

and

collectivisation. In exile, Trotsky maintained that the disproportions and imbalances which became characteristic of Stalinist planning in the 1930s such as the underdeveloped

consumer base along with the priority focus on

heavy industry

Heavy industry is an industry that involves one or more characteristics such as large and heavy products; large and heavy equipment and facilities (such as heavy equipment, large machine tools, huge buildings and large-scale infrastructure); o ...

were due to a number of avoidable problems. He argued that the industrial drive had been enacted under more severe circumstances, several years later and in a less rational manner than originally conceived by the Left Opposition.

Ernest Mandel

Ernest Ezra Mandel (; 5 April 1923 – 20 July 1995), also known by various pseudonyms such as Ernest Germain, Pierre Gousset, Henri Vallin, Walter, was a Belgian Marxian economist, Trotskyist activist and theorist, and Holocaust survivor. He f ...

argued the economic programme of Trotsky differed from the forced

policy of collectivisation implemented by Stalin after 1928 due to the levels of brutality associated with its enforcement. Notably, Trotsky sought to raise taxation on wealthier farmers and encourage farm labourers along with poor peasants to form collective farms on a voluntary basis in conjunction with the allocation of state resources to agricultural

machinery

A machine is a physical system that uses power to apply forces and control movement to perform an action. The term is commonly applied to artificial devices, such as those employing engines or motors, but also to natural biological macromolec ...

,

fertilizers

A fertilizer or fertiliser is any material of natural or synthetic origin that is applied to soil or to plant tissues to supply plant nutrition, plant nutrients. Fertilizers may be distinct from Liming (soil), liming materials or other non- ...

,

credit

Credit (from Latin verb ''credit'', meaning "one believes") is the trust which allows one party to provide money or resources to another party wherein the second party does not reimburse the first party immediately (thereby generating a debt) ...

and

agronomic assistance.

In 1932–33, Trotsky insisted upon the need for mass participation in the operationalisation of the planned economy:

"Insoluble without the daily experience of millions, without their critical review of their own collective experience, without their expression of their needs and demands and could not be carried out within the confines of the official sanctums.... even if the Politburo

A politburo () or political bureau is the highest organ of the central committee in communist parties. The term is also sometimes used to refer to similar organs in socialist and Islamist parties, such as the UK Labour Party's NEC or the Poli ...

consisted of seven universal geniuses, of seven Marxes, or seven Lenins, it will still be unable, all on its own, with all its creative imagination, to assert command over the economy

An economy is an area of the Production (economics), production, Distribution (economics), distribution and trade, as well as Consumption (economics), consumption of Goods (economics), goods and Service (economics), services. In general, it is ...

of 170 million people".

British

cybernetician Stafford Beer

Anthony Stafford Beer (25 September 1926 – 23 August 2002) was a British theorist, consultant and professor at Manchester Business School. He is known for his work in the fields of operational research and management cybernetics, and for his ...

who worked on a

decentralized form of economic planning,

Project Cybersyn from 1970 to 1973, was reported to have read and been influenced by Trotsky's critique of the

Soviet bureaucracy.

The economic platform of a

planned economy

A planned economy is a type of economic system where investment, production and the allocation of capital goods takes place according to economy-wide economic plans and production plans. A planned economy may use centralized, decentralized, ...

combined with an authentic

worker's democracy as originally advocated by Trotsky has constituted the programme of the Fourth International and the modern Trotskyist movement.

Transitional program

Trotsky drafted the transitional programme as a programmatic document for the founding congress of the Fourth International in 1938.

He explicitly emphasised the core need for the programme::

"It is explicitly necessary to help the masses in the process of the daily struggle to find the bridge between present demands and the socialist program of the revolution. This bridge should include a system of transitional demands, stemming from today's conditions and from today's consciousness of wide layers of the working class and unalterably leading to one final conclusion: the conquest of power by the proletariat".

The transitional programme features three types of proposals for action. This includes democratic demands such as

the right of unions and

self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

; immediate demands which are concerned with everyday struggles such as

wage increases and transitional demands which are directed at the capitalist system such as

worker's control of production .

Scientific socialism

In his collection of texts, ''

In Defence of Marxism'',

Leon Trotsky

Lev Davidovich Bronstein ( – 21 August 1940), better known as Leon Trotsky,; ; also transliterated ''Lyev'', ''Trotski'', ''Trockij'' and ''Trotzky'' was a Russian revolutionary, Soviet politician, and political theorist. He was a key figure ...

defended the

dialectical method of scientific socialism during the factional schisms within the American Trotskyist movement during 1939–40. Trotsky viewed dialectics as an essential method of analysis to discern the class nature of the Soviet Union. Specifically, he described scientific socialism as the "conscious expression of the unconscious historical process". According to Daniels, Trotsky conceived historical revolutions as a long, interrelated process of political and social struggle which undergo various stages with national and international dimensions.

Prior to his expulsion from the Soviet Union, Trotsky had encouraged

empirical

Empirical evidence is evidence obtained through sense experience or experimental procedure. It is of central importance to the sciences and plays a role in various other fields, like epistemology and law.

There is no general agreement on how t ...

studies with the use of Marxist methods for social and historical development. He also insisted on the need for a

freedom of science, including theoretical research, in 1925 for socially useful purposes. Trotsky defended

Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

’s

theory of relativity

The theory of relativity usually encompasses two interrelated physics theories by Albert Einstein: special relativity and general relativity, proposed and published in 1905 and 1915, respectively. Special relativity applies to all physical ph ...

in Soviet intellectual circles but this became an anathema during the Stalin era and was only rehabilitated following the latter's death.

In line with the scientific outlook of Marxist philosophy, Trotsky placed a heavy emphasis on science to alleviate the level of backwardness among the Soviet masses. Concurrently, he viewed socialism as a progressive struggle for

science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, culture and morality in which science should be given the maximum scope for development. In 1918, he had supported

Taylorism

Scientific management is a theory of management that analyzes and synthesizes workflows. Its main objective is improving economic efficiency, especially labor productivity. It was one of the earliest attempts to apply science to the engineer ...

along with Lenin as a means of scientifically managing industries with the support of foreign engineers. Multiple historians have stressed the

technocratic nature of his governance proposals compared to Stalin and Bukharin with a higher reliance on "bourgeois" experts and specialists.

Trotskyists have emphasised the dialectical relationship between

objective,

material conditions and

subjective factors such as party, leadership in understanding the nature of change in historical events.

United front and theory of fascism

Trotsky was a central figure in the

Comintern

The Communist International, abbreviated as Comintern and also known as the Third International, was a political international which existed from 1919 to 1943 and advocated world communism. Emerging from the collapse of the Second Internatio ...

during its first four congresses. During this time, he helped to generalize the strategy and tactics of the Bolsheviks to newly formed Communist parties across Europe and further afield. From 1921 onwards, the

united front

A united front is an alliance of groups against their common enemies, figuratively evoking unification of previously separate geographic fronts or unification of previously separate armies into a front. The name often refers to a political and/ ...

, a method of uniting revolutionaries and reformists in the common struggle while winning some of the workers to revolution, was the central tactic put forward by the Comintern after the defeat of the German revolution.

After he was exiled and politically marginalized by Stalinism, Trotsky continued to argue for a united front against fascism in Germany and Spain. According to Joseph Choonara of the British

Socialist Workers Party in ''

International Socialism

''International Socialism'' is a British-based quarterly journal established in 1960 and published in London by the Socialist Workers Party which discusses socialist theory. It is currently edited by Joseph Choonara who replaced Alex Callini ...

'', his articles on the united front represent an essential part of his political legacy.

Trotsky also formulated a theory of fascism based on a dialectical interpretation of events to analyze the manifestation of

Italian fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

and the early emergence of Nazi Germany from 1930 to 1933.

Marxist theorist and economist

Hillel Ticktin argued that his political strategy and approach to fascism such as the emphasis on an organisational bloc between the

German Communist Party and

Social-Democratic party during the interwar period would very likely have prevented

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

from ascending to political power.

Political ethics and morality

In 1938, Trotsky had written ''

Their Morals and Ours'' which consisted of

ethical polemics in response to criticisms around his actions concerning the

Kronstadt rebellion

The Kronstadt rebellion () was a 1921 insurrection of Soviet sailors, Marines, naval infantry, and civilians against the Bolsheviks, Bolshevik government in the Russian port city of Kronstadt. Located on Kotlin Island in the Gulf of Finland, ...

and wider questions posed around the perceived, "

amoral" methods of the Bolsheviks. Critics believed these methods seemed to emulate the

Jesuit

The Society of Jesus (; abbreviation: S.J. or SJ), also known as the Jesuit Order or the Jesuits ( ; ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

maxim

Maxim or Maksim may refer to:

Entertainment

*Maxim (magazine), ''Maxim'' (magazine), an international men's magazine

** Maxim (Australia), ''Maxim'' (Australia), the Australian edition

** Maxim (India), ''Maxim'' (India), the Indian edition

*Maxim ...

that the "

ends justifies the means". Trotsky argued that Marxism situated the foundation of morality as a product of society to

serve social interests rather than “"eternal moral truths" proclaimed by institutional religions. On the other hand, he regarded it as farcical to assert that an end could justify any criminal means and viewed this to be a distorted representation of the Jesuit maxim. Instead, Trotsky believed that the means and ends frequently “exchanged places” as when

democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

is sought by the

working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

as an instrument to actualize socialism. He also viewed revolution to be deducible from the

laws of the development and primarily the

class struggle

In political science, the term class conflict, class struggle, or class war refers to the economic antagonism and political tension that exist among social classes because of clashing interests, competition for limited resources, and inequali ...

but this did not mean all means are permissible. Fundamentally, Trotsky argued that ends "rejects" means which are incompatible with itself. In other words,

socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

cannot be furthered through

fraud

In law, fraud is intent (law), intentional deception to deprive a victim of a legal right or to gain from a victim unlawfully or unfairly. Fraud can violate Civil law (common law), civil law (e.g., a fraud victim may sue the fraud perpetrato ...

,

deceit or

the worship of leaders but through honesty and integrity as essential elements of

revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

morality in dealing with the working masses.

History

Origins

According to Trotsky, the term "Trotskyism" was coined by

Pavel Milyukov (sometimes transliterated as Paul Miliukoff), the ideological leader of the

Constitutional Democratic Party (Kadets) in Russia. Milyukov waged a bitter war against Trotskyism "as early as 1905".

Trotsky was elected chairman of the

St. Petersburg Soviet during the

Russian Revolution of 1905

The Russian Revolution of 1905, also known as the First Russian Revolution, was a revolution in the Russian Empire which began on 22 January 1905 and led to the establishment of a constitutional monarchy under the Russian Constitution of 1906, t ...

. He pursued a policy of

proletarian revolution

A proletarian revolution or proletariat revolution is a social revolution in which the working class attempts to overthrow the bourgeoisie and change the previous political system. Proletarian revolutions are generally advocated by socialist ...

at a time when other socialist trends advocated a transition to a "bourgeois" (capitalist) regime to replace the essentially feudal Romanov state. This year, Trotsky developed the theory of

permanent revolution, as it later became known (see below). In 1905, Trotsky quotes from a postscript to a book by Milyukov, ''The Elections to the Second State Duma'', published no later than May 1907:

Milyukov suggests that the mood of the "democratic public" was in support of Trotsky's policy of the overthrow of the Romanov regime alongside a workers' revolution to overthrow the capitalist owners of industry, support for strike action and the establishment of democratically elected

workers' councils or "soviets". This differed from variations of

Council Communism

Council communism or councilism is a current of communism, communist thought that emerged in the 1920s. Inspired by the German Revolution of 1918–1919, November Revolution, council communism was opposed to state socialism and advocated wor ...

in

Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

due to the Russian Peasantry and the role they have in overall

Leninism

Leninism (, ) is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the Dictatorship of the proletariat#Vladimir Lenin, dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary Vangu ...

including Trotskyism compared to the role they have in Council Communism

Trotskyism and the 1917 Russian Revolution

During his leadership of the Russian revolution of 1905, Trotsky argued that once it became clear that the Tsar's army would not come out in support of the workers, it was necessary to retreat before the armed might of the state in as good an order as possible. In 1917, Trotsky was again elected chairman of the Petrograd soviet, but this time soon came to lead the

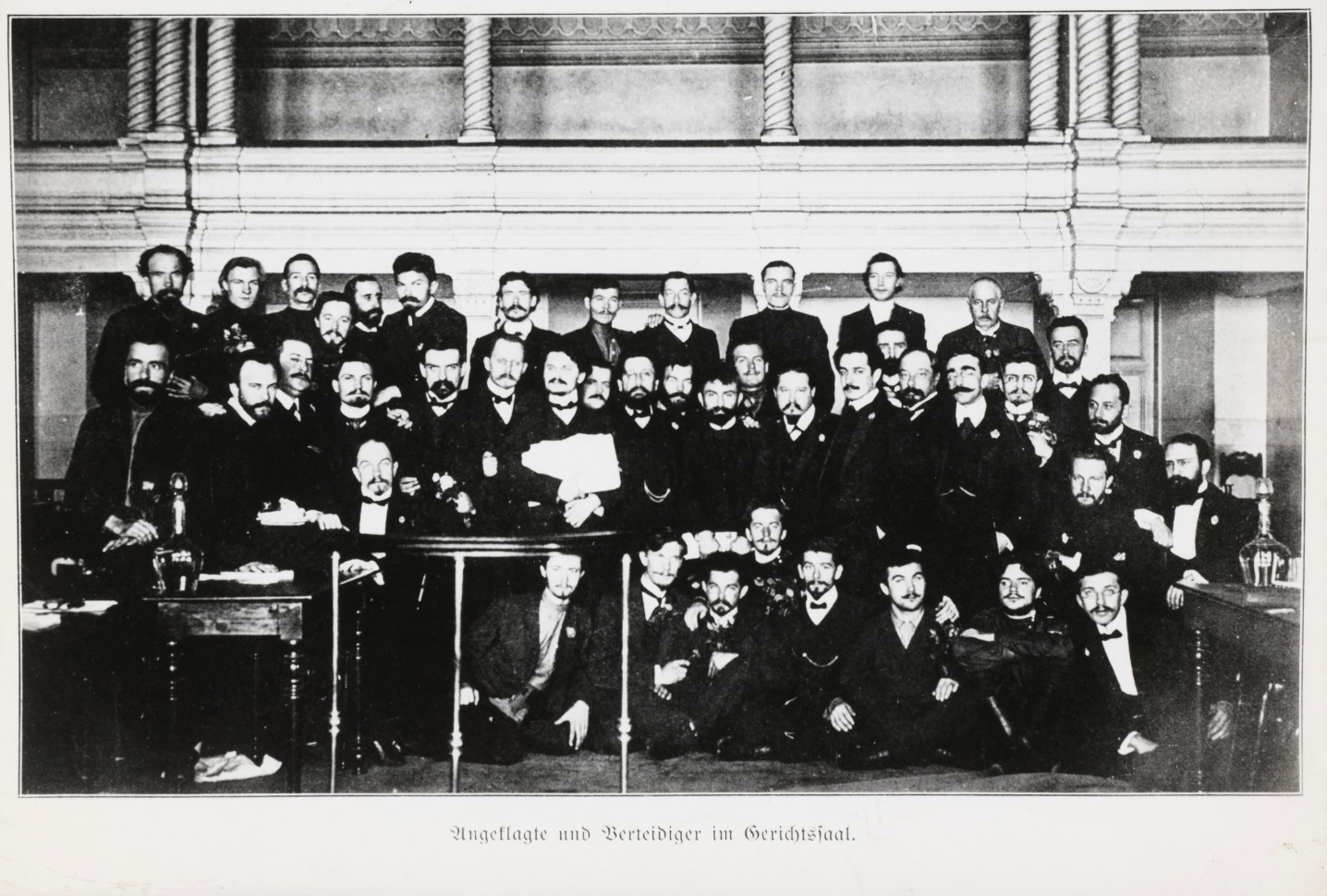

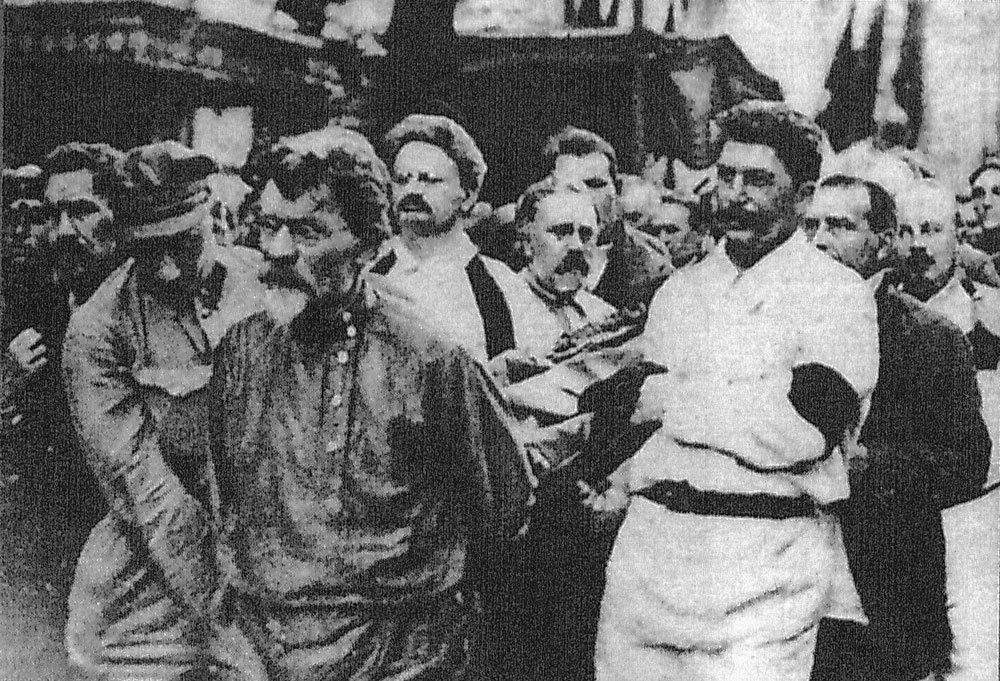

Military Revolutionary Committee, which had the allegiance of the Petrograd garrison and carried through the October 1917 insurrection. Stalin wrote:

As a result of his role in the Russian Revolution of 1917, the theory of permanent revolution was embraced by the young Soviet state until 1924.

The Russian revolution of 1917 was marked by two revolutions: the relatively spontaneous February 1917 revolution and the 25 October 1917 seizure of power by the Bolsheviks, who had gained the leadership of the Petrograd soviet.

Before the February 1917 Russian revolution, Lenin had formulated a slogan calling for the "democratic dictatorship of the proletariat and the peasantry", but after the February revolution, through his April Theses, Lenin instead called for "all power to the Soviets". Nevertheless, Lenin continued to emphasise (as did Trotsky) the classical Marxist position that the peasantry formed a basis for the development of capitalism, not socialism.

Also, before February 1917, Trotsky had not accepted the importance of a Bolshevik-style organisation. Once the February 1917 Russian revolution had broken out, Trotsky admitted the importance of a Bolshevik organisation and joined the Bolsheviks in July 1917. Although many, like Stalin, saw Trotsky's role in the October 1917 Russian revolution as central, Trotsky wrote that without Lenin and the Bolshevik Party, the October revolution of 1917 would not have taken place.

Other Bolshevik figures such as

Anatoly Lunacharsky

Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky (, born ''Anatoly Aleksandrovich Antonov''; – 26 December 1933) was a Russian Marxist revolutionary and the first Soviet People's Commissariat for Education, People's Commissar (minister) of Education, as well ...

,

Moisei Uritsky and

Dmitry Manuilsky agreed that Lenin's influence on the Bolshevik party was decisive but the October insurrection was carried out according to Trotsky's, not to Lenin's plan.

As a result, since 1917, Trotskyism as a political theory has been fully committed to a Leninist style of