In

biochemistry

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology, a ...

, a transferase is any one of a class of

enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s that catalyse the transfer of specific

functional group

In organic chemistry, a functional group is any substituent or moiety (chemistry), moiety in a molecule that causes the molecule's characteristic chemical reactions. The same functional group will undergo the same or similar chemical reactions r ...

s (e.g. a

methyl

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula (whereas normal methane has the formula ). In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as ...

or

glycosyl

In organic chemistry, a glycosyl group is a univalent free radical or substituent structure obtained by removing the hydroxyl () group from the hemiacetal () group found in the cyclic form of a monosaccharide and, by extension, of a lower ol ...

group) from one

molecule

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms that are held together by Force, attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions that satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemi ...

(called the donor) to another (called the acceptor). They are involved in hundreds of different

biochemical pathways throughout biology, and are integral to some of life's most important processes.

Transferases are involved in myriad reactions in the cell. Three examples of these reactions are the activity of

coenzyme A

Coenzyme A (CoA, SHCoA, CoASH) is a coenzyme, notable for its role in the Fatty acid metabolism#Synthesis, synthesis and Fatty acid metabolism#.CE.B2-Oxidation, oxidation of fatty acids, and the oxidation of pyruvic acid, pyruvate in the citric ac ...

(CoA)

transferase, which transfers

thiol esters,

the action of

N-acetyltransferase, which is part of the pathway that metabolizes

tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α-carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromat ...

, and the regulation of

pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH), which converts

pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic ...

to

acetyl CoA. Transferases are also utilized during translation. In this case, an amino acid chain is the functional group transferred by a

peptidyl transferase. The transfer involves the removal of the growing

amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although over 500 amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the 22 α-amino acids incorporated into proteins. Only these 22 a ...

chain from the

tRNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

molecule in the

A-site

The A-site (A for aminoacyl) of a ribosome is a binding site for charged t-RNA molecules during protein synthesis. One of three such binding sites, the A-site is the first location the t-RNA binds during the protein synthesis process, the othe ...

of the

ribosome

Ribosomes () are molecular machine, macromolecular machines, found within all cell (biology), cells, that perform Translation (biology), biological protein synthesis (messenger RNA translation). Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order s ...

and its subsequent addition to the amino acid attached to the tRNA in the

P-site.

Mechanistically, an enzyme that catalyzed the following reaction would be a transferase:

:

In the above reaction (where the dash represents a bond, not a minus sign), X would be the donor, and Y would be the acceptor. R denotes the functional group transferred as a result of transferase activity. The donor is often a

coenzyme

A cofactor is a non-protein chemical compound or Metal ions in aqueous solution, metallic ion that is required for an enzyme's role as a catalysis, catalyst (a catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a chemical reaction). Cofactors can ...

.

History

Some of the most important discoveries relating to transferases occurred as early as the 1930s. Earliest discoveries of transferase activity occurred in other classifications of

enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s, including

beta-galactosidase,

protease

A protease (also called a peptidase, proteinase, or proteolytic enzyme) is an enzyme that catalysis, catalyzes proteolysis, breaking down proteins into smaller polypeptides or single amino acids, and spurring the formation of new protein products ...

, and acid/base

phosphatase

In biochemistry, a phosphatase is an enzyme that uses water to cleave a phosphoric acid Ester, monoester into a phosphate ion and an Alcohol (chemistry), alcohol. Because a phosphatase enzyme catalysis, catalyzes the hydrolysis of its Substrate ...

. Prior to the realization that individual enzymes were capable of such a task, it was believed that two or more enzymes enacted functional group transfers.

Transamination

Transamination is a chemical reaction that transfers an amino group to a ketoacid to form new amino acids.This pathway is responsible for the deamination of most amino acids. This is one of the major degradation pathways which convert essential a ...

, or the transfer of an

amine

In chemistry, amines (, ) are organic compounds that contain carbon-nitrogen bonds. Amines are formed when one or more hydrogen atoms in ammonia are replaced by alkyl or aryl groups. The nitrogen atom in an amine possesses a lone pair of elec ...

(or NH

2) group from an amino acid to a

keto acid by an

aminotransferase (also known as a "transaminase"), was first noted in 1930 by

Dorothy M. Needham, after observing the disappearance of

glutamic acid

Glutamic acid (symbol Glu or E; known as glutamate in its anionic form) is an α- amino acid that is used by almost all living beings in the biosynthesis of proteins. It is a non-essential nutrient for humans, meaning that the human body can ...

added to pigeon breast muscle. This observance was later verified by the discovery of its reaction mechanism by Braunstein and Kritzmann in 1937. Their analysis showed that this reversible reaction could be applied to other tissues. This assertion was validated by

Rudolf Schoenheimer's work with

radioisotope

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess numbers of either neutrons or protons, giving it excess nuclear energy, and making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ...

s as

tracers in 1937.

This in turn would pave the way for the possibility that similar transfers were a primary means of producing most amino acids via amino transfer.

Another such example of early transferase research and later reclassification involved the discovery of uridyl transferase. In 1953, the enzyme

UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase was shown to be a transferase, when it was found that it could reversibly produce

UTP and

G1P from

UDP-glucose and an organic

pyrophosphate

In chemistry, pyrophosphates are phosphorus oxyanions that contain two phosphorus atoms in a linkage. A number of pyrophosphate salts exist, such as disodium pyrophosphate () and tetrasodium pyrophosphate (), among others. Often pyrophosphates a ...

.

Another example of historical significance relating to transferase is the discovery of the mechanism of

catecholamine

A catecholamine (; abbreviated CA), most typically a 3,4-dihydroxyphenethylamine, is a monoamine neurotransmitter, an organic compound that has a catechol (benzene with two hydroxyl side groups next to each other) and a side-chain amine.

Cate ...

breakdown by

catechol-O-methyltransferase. This discovery was a large part of the reason for

Julius Axelrod’s 1970

Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

(shared with

Sir Bernard Katz and

Ulf von Euler).

Classification of transferases continues to this day, with new ones being discovered frequently. An example of this is Pipe, a sulfotransferase involved in the dorsal-ventral patterning of ''

Drosophila

''Drosophila'' (), from Ancient Greek δρόσος (''drósos''), meaning "dew", and φίλος (''phílos''), meaning "loving", is a genus of fly, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or p ...

''. Initially, the exact mechanism of Pipe was unknown, due to a lack of information on its substrate. Research into Pipe's catalytic activity eliminated the likelihood of it being a heparan sulfate

glycosaminoglycan. Further research has shown that Pipe targets the ovarian structures for sulfation. Pipe is currently classified as a ''Drosophila''

heparan sulfate 2-O-sulfotransferase.

Nomenclature

Systematic name

A systematic name is a name given in a systematic way to one unique group, organism, object or chemical substance, out of a specific population or collection. Systematic names are usually part of a nomenclature.

A semisystematic name or semitrivi ...

s of transferases are constructed in the form of "donor:acceptor grouptransferase."

For example, methylamine:L-glutamate N-methyltransferase would be the standard naming convention for the transferase

methylamine-glutamate N-methyltransferase, where

methylamine

Methylamine, also known as methanamine, is an organic compound with a formula of . This colorless gas is a derivative of ammonia, but with one hydrogen atom being replaced by a methyl group. It is the simplest primary amine.

Methylamine is sold ...

is the donor,

L-glutamate is the acceptor, and

methyltransferase is the EC category grouping. This same action by the transferase can be illustrated as follows:

:methylamine + L-glutamate

NH3 +

N-methyl-L-glutamate

However, other accepted names are more frequently used for transferases, and are often formed as "acceptor grouptransferase" or "donor grouptransferase." For example, a

DNA methyltransferase

In biochemistry, the DNA methyltransferase (DNA MTase, DNMT) family of enzymes catalyze the transfer of a methyl group to DNA. DNA methylation serves a wide variety of biological functions. All the known DNA methyltransferases use S-adenosyl ...

is a transferase that catalyzes the transfer of a

methyl

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula (whereas normal methane has the formula ). In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as ...

group to a

DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

acceptor. In practice, many molecules are not referred to using this terminology due to more prevalent common names. For example,

RNA polymerase

In molecular biology, RNA polymerase (abbreviated RNAP or RNApol), or more specifically DNA-directed/dependent RNA polymerase (DdRP), is an enzyme that catalyzes the chemical reactions that synthesize RNA from a DNA template.

Using the e ...

is the modern common name for what was formerly known as RNA nucleotidyltransferase, a kind of

nucleotidyl transferase that transfers

nucleotides

Nucleotides are Organic compound, organic molecules composed of a nitrogenous base, a pentose sugar and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers – deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both o ...

to the 3’ end of a growing

RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

strand. In the EC system of classification, the accepted name for RNA polymerase is DNA-directed RNA polymerase.

Classification

Described primarily based on the type of biochemical group transferred, transferases can be divided into ten categories (based on the

EC Number classification).

These categories comprise over 450 different unique enzymes.

In the EC numbering system, transferases have been given a classification of EC2.

Hydrogen

Hydrogen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol H and atomic number 1. It is the lightest and abundance of the chemical elements, most abundant chemical element in the universe, constituting about 75% of all baryon, normal matter ...

is not considered a functional group when it comes to transferase targets; instead, hydrogen transfer is included under

oxidoreductase

In biochemistry, an oxidoreductase is an enzyme that catalyzes the transfer of electrons from one molecule, the reductant, also called the electron donor, to another, the oxidant, also called the electron acceptor. This group of enzymes usually ut ...

s,

[ due to electron transfer considerations.

]

Role

EC 2.1: single carbon transferases

EC 2.1 includes enzymes that transfer single-carbon groups. This category consists of transfers of methyl

In organic chemistry, a methyl group is an alkyl derived from methane, containing one carbon atom bonded to three hydrogen atoms, having chemical formula (whereas normal methane has the formula ). In formulas, the group is often abbreviated as ...

, hydroxymethyl, formyl, carboxy, carbamoyl, and amido groups. Carbamoyltransferases, as an example, transfer a carbamoyl group from one molecule to another. Carbamoyl groups follow the formula NH2CO. In ATCase such a transfer is written as carbamoyl phosphate + L-aspartate

Aspartic acid (symbol Asp or D; the ionic form is known as aspartate), is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. The L-isomer of aspartic acid is one of the 22 proteinogenic amino acids, i.e., the building blocks of protein ...

L-carbamoyl aspartate + phosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

.

EC 2.2: aldehyde and ketone transferases

Enzymes that transfer aldehyde or ketone groups and included in EC 2.2. This category consists of various transketolases and transaldolases. Transaldolase, the namesake of aldehyde transferases, is an important part of the pentose phosphate pathway. The reaction it catalyzes consists of a transfer of a dihydroxyacetone functional group to glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate, also known as triose phosphate or 3-phosphoglyceraldehyde and abbreviated as G3P, GA3P, GADP, GAP, TP, GALP or PGAL, is a metabolite that occurs as an intermediate in several central pathways of all organisms.Nelson, D ...

(also known as G3P). The reaction is as follows: sedoheptulose 7-phosphate + glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate erythrose 4-phosphate + fructose 6-phosphate.

EC 2.3: acyl transferases

Transfer of acyl groups or acyl groups that become alkyl groups during the process of being transferred are key aspects of EC 2.3. Further, this category also differentiates between amino-acyl and non-amino-acyl groups. Peptidyl transferase is a ribozyme

Ribozymes (ribonucleic acid enzymes) are RNA molecules that have the ability to Catalysis, catalyze specific biochemical reactions, including RNA splicing in gene expression, similar to the action of protein enzymes. The 1982 discovery of ribozy ...

that facilitates formation of peptide bonds during translation

Translation is the communication of the semantics, meaning of a #Source and target languages, source-language text by means of an Dynamic and formal equivalence, equivalent #Source and target languages, target-language text. The English la ...

.aminoacyl-tRNA

Aminoacyl-tRNA (also aa-tRNA or charged tRNA) is tRNA to which its cognate amino acid is chemically bonded (charged). The aa-tRNA, along with particular elongation factors, deliver the amino acid to the ribosome for incorporation into the polyp ...

, following this reaction: peptidyl-tRNAA + aminoacyl-tRNAB tRNAA + peptidyl aminoacyl-tRNAB.

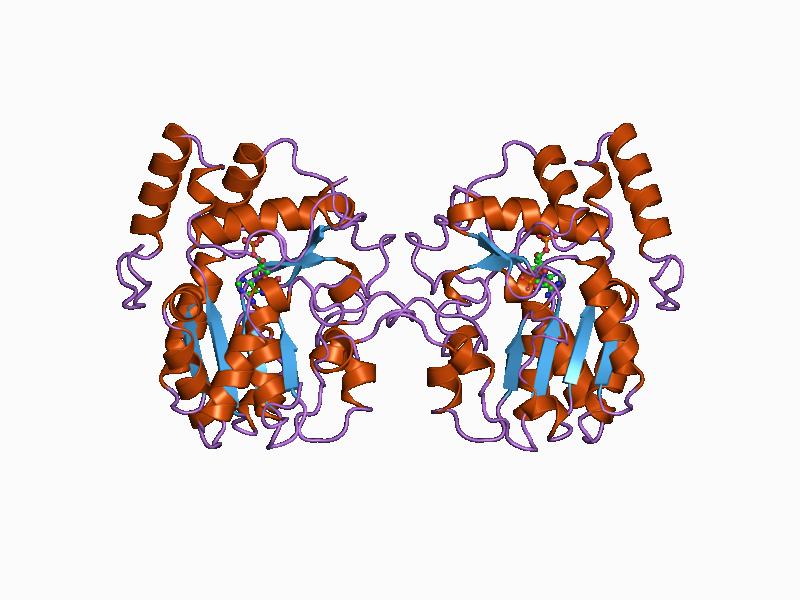

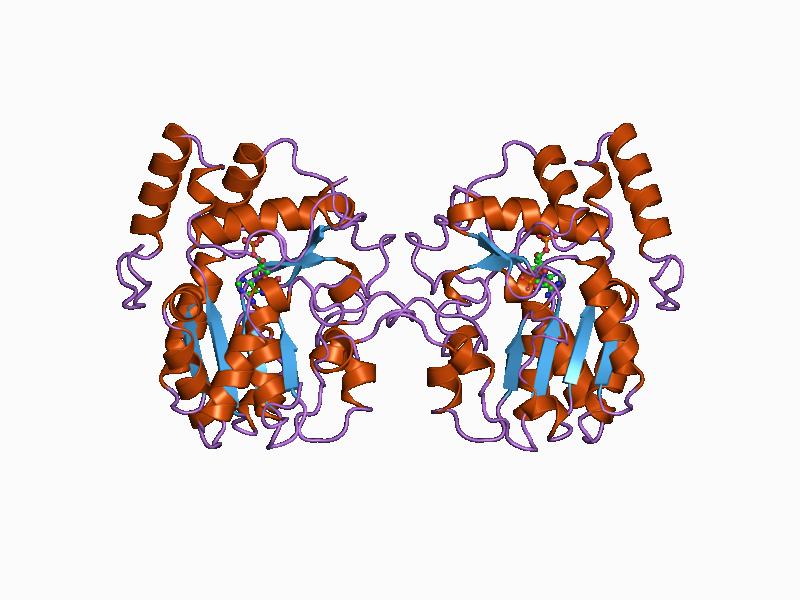

EC 2.4: glycosyl, hexosyl, and pentosyl transferases

EC 2.4 includes enzymes that transfer glycosyl

In organic chemistry, a glycosyl group is a univalent free radical or substituent structure obtained by removing the hydroxyl () group from the hemiacetal () group found in the cyclic form of a monosaccharide and, by extension, of a lower ol ...

groups, as well as those that transfer hexose and pentose. Glycosyltransferase is a subcategory of EC 2.4 transferases that is involved in biosynthesis

Biosynthesis, i.e., chemical synthesis occurring in biological contexts, is a term most often referring to multi-step, enzyme-Catalysis, catalyzed processes where chemical substances absorbed as nutrients (or previously converted through biosynthe ...

of disaccharides

A disaccharide (also called a double sugar or ''biose'') is the sugar formed when two monosaccharides are joined by glycosidic linkage. Like monosaccharides, disaccharides are simple sugars soluble in water. Three common examples are sucrose, l ...

and polysaccharides

Polysaccharides (), or polycarbohydrates, are the most abundant carbohydrates found in food. They are long-chain polymeric carbohydrates composed of monosaccharide units bound together by glycosidic linkages. This carbohydrate can react with wat ...

through transfer of monosaccharides to other molecules. An example of a prominent glycosyltransferase is lactose synthase which is a dimer possessing two protein subunit

In structural biology, a protein subunit is a polypeptide chain or single protein molecule that assembles (or "''coassembles''") with others to form a protein complex.

Large assemblies of proteins such as viruses often use a small number of t ...

s. Its primary action is to produce lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

from glucose

Glucose is a sugar with the Chemical formula#Molecular formula, molecular formula , which is often abbreviated as Glc. It is overall the most abundant monosaccharide, a subcategory of carbohydrates. It is mainly made by plants and most algae d ...

and UDP-galactose.

EC 2.5: alkyl and aryl transferases

EC 2.5 relates to enzymes that transfer alkyl or aryl groups, but does not include methyl groups. This is in contrast to functional groups that become alkyl groups when transferred, as those are included in EC 2.3. EC 2.5 currently only possesses one sub-class: Alkyl and aryl transferases. Cysteine synthase, for example, catalyzes the formation of acetic acids and cysteine

Cysteine (; symbol Cys or C) is a semiessential proteinogenic amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . The thiol side chain in cysteine enables the formation of Disulfide, disulfide bonds, and often participates in enzymatic reactions as ...

from O3-acetyl-L-serine and hydrogen sulfide

Hydrogen sulfide is a chemical compound with the formula . It is a colorless chalcogen-hydride gas, and is toxic, corrosive, and flammable. Trace amounts in ambient atmosphere have a characteristic foul odor of rotten eggs. Swedish chemist ...

: O3-acetyl-L-serine + H2S L-cysteine + acetate.

EC 2.6: nitrogenous transferases

The grouping consistent with transfer of nitrogenous

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a nonmetal and the lightest member of group 15 of the periodic table, often called the pnictogens. It is a common element in the universe, estimated at seventh ...

groups is EC 2.6. This includes enzymes like transaminase

Transaminases or aminotransferases are enzymes that catalyze a transamination reaction between an amino acid and an α-keto acid. They are important in the synthesis of amino acids, which form proteins.

Function and mechanism

An amino acid con ...

(also known as "aminotransferase"), and a very small number of oximinotransferases and other nitrogen group transferring enzymes. EC 2.6 previously included amidinotransferase but it has since been reclassified as a subcategory of EC 2.1 (single-carbon transferring enzymes). In the case of aspartate transaminase

Aspartate transaminase (AST) or aspartate aminotransferase, also known as AspAT/ASAT/AAT or (serum) glutamic oxaloacetic transaminase (GOT, SGOT), is a pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent transaminase enzyme () that was first described by Arthur ...

, which can act on tyrosine

-Tyrosine or tyrosine (symbol Tyr or Y) or 4-hydroxyphenylalanine is one of the 20 standard amino acids that are used by cells to synthesize proteins. It is a conditionally essential amino acid with a polar side group. The word "tyrosine" is ...

, phenylalanine

Phenylalanine (symbol Phe or F) is an essential α-amino acid with the chemical formula, formula . It can be viewed as a benzyl group substituent, substituted for the methyl group of alanine, or a phenyl group in place of a terminal hydrogen of ...

, and tryptophan

Tryptophan (symbol Trp or W)

is an α-amino acid that is used in the biosynthesis of proteins. Tryptophan contains an α-amino group, an α-carboxylic acid group, and a side chain indole, making it a polar molecule with a non-polar aromat ...

, it reversibly transfers an amino group from one molecule to the other.

EC 2.7: phosphorus transferases

While EC 2.7 includes enzymes that transfer phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

-containing groups, it also includes nuclotidyl transferases as well. Sub-category phosphotransferase is divided up in categories based on the type of group that accepts the transfer.cyclin-dependent kinase

Cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) are a predominant group of serine/threonine protein kinases involved in the regulation of the cell cycle and its progression, ensuring the integrity and functionality of cellular machinery. These regulatory enzym ...

(CDK), which comprises a sub-family of protein kinase

A protein kinase is a kinase which selectively modifies other proteins by covalently adding phosphates to them ( phosphorylation) as opposed to kinases which modify lipids, carbohydrates, or other molecules. Phosphorylation usually results in a f ...

s. As their name implies, CDKs are heavily dependent on specific cyclin

Cyclins are proteins that control the progression of a cell through the cell cycle by activating cyclin-dependent kinases (CDK).

Etymology

Cyclins were originally discovered by R. Timothy Hunt in 1982 while studying the cell cycle of sea urch ...

molecules for activation

In chemistry and biology, activation is the process whereby something is prepared or excited for a subsequent reaction.

Chemistry

In chemistry, "activation" refers to the reversible transition of a molecule into a nearly identical chemical or ...

.

EC 2.8: sulfur transferases

Transfer of sulfur-containing groups is covered by EC 2.8 and is subdivided into the subcategories of sulfurtransferases, sulfotransferases, and CoA-transferases, as well as enzymes that transfer alkylthio groups. A specific group of sulfotransferases are those that use PAPS as a sulfate group donor. Within this group is alcohol sulfotransferase which has a broad targeting capacity. Due to this, alcohol sulfotransferase is also known by several other names including "hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase," "steroid sulfokinase," and "estrogen sulfotransferase." Decreases in its activity has been linked to human liver disease. This transferase acts via the following reaction: 3'-phosphoadenylyl sulfate + an alcohol adenosine 3',5'bisphosphate + an alkyl sulfate.

Transfer of sulfur-containing groups is covered by EC 2.8 and is subdivided into the subcategories of sulfurtransferases, sulfotransferases, and CoA-transferases, as well as enzymes that transfer alkylthio groups. A specific group of sulfotransferases are those that use PAPS as a sulfate group donor. Within this group is alcohol sulfotransferase which has a broad targeting capacity. Due to this, alcohol sulfotransferase is also known by several other names including "hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase," "steroid sulfokinase," and "estrogen sulfotransferase." Decreases in its activity has been linked to human liver disease. This transferase acts via the following reaction: 3'-phosphoadenylyl sulfate + an alcohol adenosine 3',5'bisphosphate + an alkyl sulfate.

EC 2.9: selenium transferases

EC 2.9 includes enzymes that transfer selenium

Selenium is a chemical element; it has symbol (chemistry), symbol Se and atomic number 34. It has various physical appearances, including a brick-red powder, a vitreous black solid, and a grey metallic-looking form. It seldom occurs in this elem ...

-containing groups. This category only contains two transferases, and thus is one of the smallest categories of transferase. Selenocysteine synthase, which was first added to the classification system in 1999, converts seryl-tRNA(Sec UCA) into selenocysteyl-tRNA(Sec UCA).

EC 2.10: metal transferases

The category of EC 2.10 includes enzymes that transfer molybdenum

Molybdenum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Mo (from Neo-Latin ''molybdaenum'') and atomic number 42. The name derived from Ancient Greek ', meaning lead, since its ores were confused with lead ores. Molybdenum minerals hav ...

or tungsten

Tungsten (also called wolfram) is a chemical element; it has symbol W and atomic number 74. It is a metal found naturally on Earth almost exclusively in compounds with other elements. It was identified as a distinct element in 1781 and first ...

-containing groups. However, as of 2011, only one enzyme has been added: molybdopterin molybdotransferase. This enzyme is a component of MoCo biosynthesis in ''Escherichia coli''. The reaction it catalyzes is as follows: adenylyl- molybdopterin + molybdate molybdenum cofactor + AMP.

Role in histo-blood group

The A and B transferases are the foundation of the human ABO blood group system. Both A and B transferases are glycosyltransferases, meaning they transfer a sugar molecule onto an H-antigen.glycoprotein

Glycoproteins are proteins which contain oligosaccharide (sugar) chains covalently attached to amino acid side-chains. The carbohydrate is attached to the protein in a cotranslational or posttranslational modification. This process is known a ...

and glycolipid

Glycolipids () are lipids with a carbohydrate attached by a glycosidic (covalent) bond. Their role is to maintain the stability of the cell membrane and to facilitate cellular recognition, which is crucial to the immune response and in the c ...

conjugates that are known as the A/B antigens

In immunology, an antigen (Ag) is a molecule, moiety, foreign particulate matter, or an allergen, such as pollen, that can bind to a specific antibody or T-cell receptor. The presence of antigens in the body may trigger an immune response.

An ...

.galactose

Galactose (, ''wikt:galacto-, galacto-'' + ''wikt:-ose#Suffix 2, -ose'', ), sometimes abbreviated Gal, is a monosaccharide sugar that is about as sweetness, sweet as glucose, and about 65% as sweet as sucrose. It is an aldohexose and a C-4 epime ...

molecule to H-antigen, creating B-antigen.Homo sapiens

Humans (''Homo sapiens'') or modern humans are the most common and widespread species of primate, and the last surviving species of the genus ''Homo''. They are Hominidae, great apes characterized by their Prehistory of nakedness and clothing ...

'' to have any of four different blood type

A blood type (also known as a blood group) is based on the presence and absence of antibody, antibodies and Heredity, inherited antigenic substances on the surface of red blood cells (RBCs). These antigens may be proteins, carbohydrates, glycop ...

s: Type A (express A antigens), Type B (express B antigens), Type AB (express both A and B antigens) and Type O (express neither A nor B antigens). The gene for A and B transferases is located on chromosome 9.exon

An exon is any part of a gene that will form a part of the final mature RNA produced by that gene after introns have been removed by RNA splicing. The term ''exon'' refers to both the DNA sequence within a gene and to the corresponding sequence ...

s and six intron

An intron is any nucleotide sequence within a gene that is not expressed or operative in the final RNA product. The word ''intron'' is derived from the term ''intragenic region'', i.e., a region inside a gene."The notion of the cistron .e., gen ...

s

Deficiencies

.

Transferase deficiencies are at the root of many common illness

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

es. The most common result of a transferase deficiency is a buildup of a cellular product.

SCOT deficiency

Succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid CoA transferase deficiency (or SCOT deficiency) leads to a buildup of ketone

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

s.

Ketones

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

are created upon the breakdown of fats in the body and are an important energy source.ketones

In organic chemistry, a ketone is an organic compound with the structure , where R and R' can be a variety of carbon-containing substituents. Ketones contain a carbonyl group (a carbon-oxygen double bond C=O). The simplest ketone is acetone ( ...

leads to intermittent ketoacidosis, which usually first manifests during infancy.mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

in the gene OXCT1.

CPT-II deficiency

Carnitine palmitoyltransferase II deficiency (also known as CPT-II deficiency) leads to an excess long chain fatty acids

In chemistry, in particular in biochemistry, a fatty acid is a carboxylic acid with an aliphatic chain, which is either saturated or unsaturated. Most naturally occurring fatty acids have an unbranched chain of an even number of carbon atoms, ...

, as the body lacks the ability to transport fatty acids into the mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

to be processed as a fuel source. The disease is caused by a defect in the gene CPT2.

Galactosemia

Galactosemia

Galactosemia (British galactosaemia, from Greek γαλακτόζη + αίμα, meaning galactose + blood, accumulation of galactose in blood) is a rare genetics, genetic Metabolism, metabolic Disease, disorder that affects an individual's ability t ...

results from an inability to process galactose, a simple sugar

Monosaccharides (from Greek '' monos'': single, '' sacchar'': sugar), also called simple sugars, are the simplest forms of sugar and the most basic units ( monomers) from which all carbohydrates are built.

Chemically, monosaccharides are poly ...

. This deficiency occurs when the gene for galactose-1-phosphate uridylyltransferase

Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (or GALT, G1PUT) is an enzyme () responsible for converting ingested galactose to glucose.

Galactose-1-phosphate uridyltransferase (GALT) catalyzes the second step of the Leloir pathway of galactose meta ...

(GALT) has any number of mutations, leading to a deficiency in the amount of GALT produced.sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

, failure to grow, and mental impairment, among others. Buildup of a second toxic substance, galactitol, occurs in the lenses of the eyes, causing cataract

A cataract is a cloudy area in the lens (anatomy), lens of the eye that leads to a visual impairment, decrease in vision of the eye. Cataracts often develop slowly and can affect one or both eyes. Symptoms may include faded colours, blurry or ...

s. Currently, the only available treatment is early diagnosis followed by adherence to a diet devoid of lactose, and prescription of antibiotics for infections that may develop.

Choline acetyltransferase deficiencies

Choline acetyltransferase (also known as ChAT or CAT) is an important enzyme which produces the neurotransmitter

A neurotransmitter is a signaling molecule secreted by a neuron to affect another cell across a Chemical synapse, synapse. The cell receiving the signal, or target cell, may be another neuron, but could also be a gland or muscle cell.

Neurotra ...

acetylcholine

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic compound that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals (including humans) as a neurotransmitter. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Par ...

.acetyl group

In organic chemistry, an acetyl group is a functional group denoted by the chemical formula and the structure . It is sometimes represented by the symbol Ac (not to be confused with the element actinium). In IUPAC nomenclature, an acetyl grou ...

from acetyl co-enzyme A to choline in the synapse

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

s of nerve

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of nerve fibers (called axons). Nerves have historically been considered the basic units of the peripheral nervous system. A nerve provides a common pathway for the Electrochemistry, electrochemical nerv ...

cells and exists in two forms: soluble and membrane bound.

Alzheimer's disease

Decreased expression of ChAT is one of the hallmarks of Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease and the cause of 60–70% of cases of dementia. The most common early symptom is difficulty in remembering recent events. As the disease advances, symptoms can include problems wit ...

. Patients with Alzheimer's disease show a 30 to 90% reduction in activity in several regions of the brain, including the temporal lobe

The temporal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The temporal lobe is located beneath the lateral fissure on both cerebral hemispheres of the mammalian brain.

The temporal lobe is involved in pr ...

, the parietal lobe

The parietal lobe is one of the four Lobes of the brain, major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The parietal lobe is positioned above the temporal lobe and behind the frontal lobe and central sulcus.

The parietal lobe integra ...

and the frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a Sulcus (neur ...

.

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease)

Patients with ALS

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as motor neuron disease (MND) or—in the United States—Lou Gehrig's disease (LGD), is a rare, terminal neurodegenerative disorder that results in the progressive loss of both upper and low ...

show a marked decrease in ChAT activity in motor neurons in the spinal cord

The spinal cord is a long, thin, tubular structure made up of nervous tissue that extends from the medulla oblongata in the lower brainstem to the lumbar region of the vertebral column (backbone) of vertebrate animals. The center of the spinal c ...

and brain

The brain is an organ (biology), organ that serves as the center of the nervous system in all vertebrate and most invertebrate animals. It consists of nervous tissue and is typically located in the head (cephalization), usually near organs for ...

.

Huntington's disease

Patients with Huntington's also show a marked decrease in ChAT production. Though the specific cause of the reduced production is not clear, it is believed that the death of medium-sized motor neurons with spiny dendrite

A dendrite (from Ancient Greek language, Greek δένδρον ''déndron'', "tree") or dendron is a branched cytoplasmic process that extends from a nerve cell that propagates the neurotransmission, electrochemical stimulation received from oth ...

s leads to the lower levels of ChAT production.

Schizophrenia

Patients with Schizophrenia also exhibit decreased levels of ChAT, localized to the mesopontine tegment of the brain and the nucleus accumbens

The nucleus accumbens (NAc or NAcc; also known as the accumbens nucleus, or formerly as the ''nucleus accumbens septi'', Latin for ' nucleus adjacent to the septum') is a region in the basal forebrain rostral to the preoptic area of the hypo ...

,

Sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS)

Recent studies have shown that SIDS infants show decreased levels of ChAT in both the hypothalamus

The hypothalamus (: hypothalami; ) is a small part of the vertebrate brain that contains a number of nucleus (neuroanatomy), nuclei with a variety of functions. One of the most important functions is to link the nervous system to the endocrin ...

and the striatum

The striatum (: striata) or corpus striatum is a cluster of interconnected nuclei that make up the largest structure of the subcortical basal ganglia. The striatum is a critical component of the motor and reward systems; receives glutamat ...

.cardiovascular

In vertebrates, the circulatory system is a system of organs that includes the heart, blood vessels, and blood which is circulated throughout the body. It includes the cardiovascular system, or vascular system, that consists of the heart a ...

and respiratory systems.

Congenital myasthenic syndrome (CMS)

CMS is a family of diseases that are characterized by defects in neuromuscular transmission which leads to recurrent bouts of apnea

Apnea (also spelled apnoea in British English) is the temporary cessation of breathing. During apnea, there is no movement of the muscles of inhalation, and the volume of the lungs initially remains unchanged. Depending on how blocked the ...

(inability to breathe) that can be fatal. ChAT deficiency is implicated in myasthenia syndromes where the transition problem occurs presynaptic

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that allows a neuron (or nerve cell) to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or a target effector cell. Synapses can be classified as either chemical or electrical, depending o ...

ally.acetylcholine

Acetylcholine (ACh) is an organic compound that functions in the brain and body of many types of animals (including humans) as a neurotransmitter. Its name is derived from its chemical structure: it is an ester of acetic acid and choline. Par ...

.

Uses in biotechnology

Terminal transferases

Terminal transferases are transferases that can be used to label DNA or to produce plasmid vectors.

Glutathione transferases

The family of glutathione transferases (GST) is extremely diverse, and therefore can be used for a number of biotechnological purposes. Plants use glutathione transferases as a means to segregate toxic metals from the rest of the cell.biosensor

A biosensor is an analytical device, used for the detection of a chemical substance, that combines a biological component with a physicochemical detector.

The ''sensitive biological element'', e.g. tissue, microorganisms, organelles, cell rece ...

s to detect contaminants such as herbicides and insecticides.drug resistance

Drug resistance is the reduction in effectiveness of a medication such as an antimicrobial or an antineoplastic in treating a disease or condition. The term is used in the context of resistance that pathogens or cancers have "acquired", that is ...

.transgenic

A transgene is a gene that has been transferred naturally, or by any of a number of genetic engineering techniques, from one organism to another. The introduction of a transgene, in a process known as transgenesis, has the potential to change the ...

cultigen

A cultigen (), or cultivated plant, is a plant that has been deliberately altered or selected by humans, by means of genetic modification, graft-chimaeras, plant breeding, or wild or cultivated plant selection. These plants have commercial val ...

s.

Rubber transferases

Currently the only available commercial source of natural rubber

Rubber, also called India rubber, latex, Amazonian rubber, ''caucho'', or ''caoutchouc'', as initially produced, consists of polymers of the organic compound isoprene, with minor impurities of other organic compounds.

Types of polyisoprene ...

is the '' Hevea'' plant (''Hevea brasiliensis''). Natural rubber is superior to synthetic rubber

A synthetic rubber is an artificial elastomer. They are polymers synthesized from petroleum byproducts. About of rubber is produced annually in the United States, and of that amount two thirds are synthetic. Synthetic rubber, just like natural ru ...

in a number of commercial uses.tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

and sunflower

The common sunflower (''Helianthus annuus'') is a species of large annual forb of the daisy family Asteraceae. The common sunflower is harvested for its edible oily seeds, which are often eaten as a snack food. They are also used in the pr ...

.

Membrane-associated transferases

Many transferases associate with biological membranes as peripheral membrane proteins or anchored to membranes through a single transmembrane helix,Superfamilies of single-pass transmembrane transferases

in Membranome database for example numerous

glycosyltransferases in

Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic Cell (biology), cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it protein targeting, packages proteins ...

. Some others are multi-span

transmembrane proteins, for example certain

oligosaccharyltransferases or microsomal

glutathione S-transferase

Glutathione ''S''-transferases (GSTs), previously known as ligandins, are a family of eukaryote, eukaryotic and prokaryote, prokaryotic Biotransformation#Phase II reaction, phase II metabolic isozymes best known for their ability to Catalysis, ...

from

MAPEG family.

References

{{Portal bar, Biology, border=no

Transfer of sulfur-containing groups is covered by EC 2.8 and is subdivided into the subcategories of sulfurtransferases, sulfotransferases, and CoA-transferases, as well as enzymes that transfer alkylthio groups. A specific group of sulfotransferases are those that use PAPS as a sulfate group donor. Within this group is alcohol sulfotransferase which has a broad targeting capacity. Due to this, alcohol sulfotransferase is also known by several other names including "hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase," "steroid sulfokinase," and "estrogen sulfotransferase." Decreases in its activity has been linked to human liver disease. This transferase acts via the following reaction: 3'-phosphoadenylyl sulfate + an alcohol adenosine 3',5'bisphosphate + an alkyl sulfate.

Transfer of sulfur-containing groups is covered by EC 2.8 and is subdivided into the subcategories of sulfurtransferases, sulfotransferases, and CoA-transferases, as well as enzymes that transfer alkylthio groups. A specific group of sulfotransferases are those that use PAPS as a sulfate group donor. Within this group is alcohol sulfotransferase which has a broad targeting capacity. Due to this, alcohol sulfotransferase is also known by several other names including "hydroxysteroid sulfotransferase," "steroid sulfokinase," and "estrogen sulfotransferase." Decreases in its activity has been linked to human liver disease. This transferase acts via the following reaction: 3'-phosphoadenylyl sulfate + an alcohol adenosine 3',5'bisphosphate + an alkyl sulfate.