A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive

warhead

A warhead is the section of a device that contains the explosive agent or toxic (biological, chemical, or nuclear) material that is delivered by a missile, rocket (weapon), rocket, torpedo, or bomb.

Classification

Types of warheads include:

*E ...

designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such a device was called an automotive, automobile, locomotive, or fish torpedo; colloquially, a ''fish''. The term ''torpedo'' originally applied to a variety of devices, most of which would today be called

mines

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

*Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

Mi ...

. From about 1900, ''torpedo'' has been used strictly to designate a self-propelled underwater explosive device.

While the 19th-century

battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

had evolved primarily with a view to engagements between armored warships with

large-caliber guns, the invention and refinement of torpedoes from the 1860s onwards allowed small

torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s and other lighter

surface vessel

A watercraft or waterborne vessel is any vehicle designed for travel across or through water bodies, such as a boat, ship, hovercraft, submersible or submarine.

Types

Historically, watercraft have been divided into two main categories.

*Rafts ...

s,

submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s/

submersible

A submersible is an underwater vehicle which needs to be transported and supported by a larger ship, watercraft or dock, platform. This distinguishes submersibles from submarines, which are self-supporting and capable of prolonged independent ope ...

s, even improvised

fishing boat

A fishing vessel is a boat or ship used to catch fish and other valuable nektonic aquatic animals (e.g. shrimps/prawns, krills, coleoids, etc.) in the sea, lake or river. Humans have used different kinds of surface vessels in commercial, arti ...

s or

frogmen

A frogman is someone who is trained in scuba diving or swimming underwater. The term often applies more to professional rather than recreational divers, especially those working in a tactical capacity that includes military, and in some Europea ...

, and later

light aircraft

A light aircraft is an aircraft that has a Maximum Takeoff Weight, maximum gross takeoff weight of or less.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition'', page 308. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997.

Light aircraft are use ...

, to destroy large ships without the need of large guns, though sometimes at the risk of being hit by longer-range artillery fire.

Modern torpedoes are classified variously as lightweight, heavyweight, straight-running, autonomous homers, and wire-guided types. They can be launched from a variety of platforms. In modern warfare, a submarine-launched torpedo is almost certain to hit its target; the best defense is a counterattack using another torpedo.

Etymology

The word ''torpedo'' was first used as a name for

electric rays

The electric rays are a group of rays, flattened cartilaginous fish with enlarged pectoral fins, composing the order Torpediniformes . They are known for being capable of producing an electric discharge, ranging from 8 to 220 volts, depending ...

(in the order ''

Torpediniformes Fernando de Buen y Lozano was a Spanish ichthyologist

Ichthyology is the branch of zoology devoted to the study of fish, including bony fish (Osteichthyes), cartilaginous fish (Chondrichthyes), and jawless fish (Agnatha). According to FishBase, ...

''), which in turn comes from the Latin word ''

torp─ōd┼Ź'' ("lethargy" or "sluggishness"). In naval usage, the American inventor

David Bushnell David Bushnell may refer to:

* David Bushnell (inventor) (1740 ŌĆō 1824), American inventor, inventor of the ''Turtle'' submersible

* David Bushnell (historian) (1923 ŌĆō 2010), American historian

* David P. Bushnell (1913 ŌĆō 2005), American en ...

was reported to have first used the term as the name of a submarine of his own design, the "American Turtle or Torpedo." This usage likely inspired

Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 ŌĆō February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboat ...

's use of the term to describe his stationary

mines

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

*Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

Mi ...

, and later

Robert Whitehead's naming of the first self-propelled torpedo.

History

Middle Ages

Torpedo-like weapons were first proposed many centuries before they were successfully developed. For example, in 1275, engineer

Hasan al-Rammah

Hasan al-Rammah (, died 1295) was a Syrian Arab chemist and engineer during the Mamluk Sultanate who studied gunpowders and explosives, and sketched prototype instruments of warfare, including the first torpedo. Al-Rammah called his early torpedo " ...

ŌĆō who worked as a military scientist for the

Mamluk Sultanate

The Mamluk Sultanate (), also known as Mamluk Egypt or the Mamluk Empire, was a state that ruled Egypt, the Levant and the Hejaz from the mid-13th to early 16th centuries, with Cairo as its capital. It was ruled by a military caste of mamluks ...

of Egypt ŌĆō wrote that it might be possible to create a projectile resembling "an egg", which propelled itself through water, whilst carrying "fire".

Early naval mines

In modern language, a "torpedo" is an underwater self-propelled explosive, but historically, the term also applied to primitive naval mines and

spar torpedoes

A spar torpedo is a weapon consisting of a bomb placed at the end of a long pole, or spar, and attached to a boat. The weapon is used by running the end of the spar into the enemy ship. Spar torpedoes were often equipped with a barbed spear at ...

. These were used on an ad-hoc basis during the early modern period up to the late 19th century.

In the early 17th century, the Dutchman

Cornelius Drebbel

Cornelis Jacobszoon Drebbel (; 1572 ŌĆō 7 November 1633) was a Dutch engineer and inventor. He was the builder of the first operational submarine in 1620 and an innovator who contributed to the development of measurement and control systems, opti ...

, in the employ of

King James I of England

James VI and I (James Charles Stuart; 19 June 1566 ŌĆō 27 March 1625) was King of Scotland as James VI from 24 July 1567 and King of England and Ireland as James I from the union of the Scottish and English crowns on 24 March 1603 until ...

, invented the spar torpedo; he attached explosives to the end of a beam affixed to one of his submarines. These were used (to little effect) during the English

expeditions to La Rochelle in 1626.

The first use of a torpedo by a submarine was in 1775, by the American , which attempted to lay a bomb with a timed fuse on the hull of during the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 ŌĆō September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

, but failed in the attempt.

In the early 1800s, the American inventor

Robert Fulton

Robert Fulton (November 14, 1765 ŌĆō February 24, 1815) was an American engineer and inventor who is widely credited with developing the world's first commercially successful steamboat, the (also known as ''Clermont''). In 1807, that steamboat ...

, while in France, "conceived the idea of destroying ships by introducing floating mines under their bottoms in submarine boats". He employed the term "torpedo" for the explosive charges with which he outfitted his submarine ''

Nautilus

A nautilus (; ) is any of the various species within the cephalopod family Nautilidae. This is the sole extant family of the superfamily Nautilaceae and the suborder Nautilina.

It comprises nine living species in two genera, the type genus, ty ...

''. However, both the French and the Dutch governments were uninterested in the submarine. Fulton then concentrated on developing the torpedo-like weapon independent of a submarine deployment, and in 1804 succeeded in convincing the British government to employ his "catamaran" against the French.

An April 1804 torpedo attack on French ships anchored at

Boulogne

Boulogne-sur-Mer (; ; ; or ''Bononia''), often called just Boulogne (, ), is a coastal city in Hauts-de-France, Northern France. It is a Subprefectures in France, sub-prefecture of the Departments of France, department of Pas-de-Calais. Boul ...

, and a

follow-up attack in October, produced several explosions but no significant damage, and the weapon was abandoned.

Fulton carried out a demonstration for the US government on 20 July 1807, destroying a vessel in

New York's harbor. Further development languished as Fulton focused on his "steam-boat matters". After the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 was fought by the United States and its allies against the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, United Kingdom and its allies in North America. It began when the United States United States declaration of war on the Uni ...

broke out, the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

established a blockade of the

East Coast of the United States

The East Coast of the United States, also known as the Eastern Seaboard, the Atlantic Coast, and the Atlantic Seaboard, is the region encompassing the coast, coastline where the Eastern United States meets the Atlantic Ocean; it has always pla ...

. During the war, American forces unsuccessfully attempted to destroy the British

ship-of-the-line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

HMS ''Ramillies'' while it was lying at anchor in

New London, Connecticut

New London is a seaport city and a port of entry on the northeast coast of the United States, located at the outlet of the Thames River (Connecticut), Thames River in New London County, Connecticut, which empties into Long Island Sound. The cit ...

's harbor with torpedoes launched from small boats. This prompted the captain of ''Ramillies'',

Sir Thomas Hardy, 1st Baronet

Vice-Admiral Sir Thomas Masterman Hardy, 1st Baronet, GCB (5 April 1769 ŌĆō 20 September 1839) was a Royal Navy officer who served in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars. He took part in the Battle of Cape St. Vincent in February 1 ...

, to warn the Americans to cease using this "cruel and unheard-of warfare" or he would "order every house near the shore to be destroyed". The fact that Hardy had been previously so lenient and considerate to the Americans led them to abandon such attempts with immediate effect.

Torpedoes were used by the

Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

during the

Crimean War

The Crimean War was fought between the Russian Empire and an alliance of the Ottoman Empire, the Second French Empire, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, and the Kingdom of Sardinia (1720ŌĆō1861), Kingdom of Sardinia-Piedmont fro ...

in 1855 against British warships in the

Gulf of Finland

The Gulf of Finland (; ; ; ) is the easternmost arm of the Baltic Sea. It extends between Finland to the north and Estonia to the south, to Saint PetersburgŌĆöthe second largest city of RussiaŌĆöto the east, where the river Neva drains into it. ...

. They used an early form of chemical detonator. During the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, the term ''torpedo'' was used for what is today called a

contact mine

A naval mine is a self-contained explosive weapon placed in water to damage or destroy surface ships or submarines. Similar to anti-personnel and other land mines, and unlike purpose launched naval depth charges, they are deposited and left to ...

, floating on or below the water surface using an air-filled

demijohn

A carboy, also known as a demijohn or a lady jeanne, is a rigid container with a typical capacity of . Carboys are primarily used for transporting liquids, often drinking water or chemicals.

They are also used for in-home fermentation of bev ...

or similar flotation device. These devices were very primitive and apt to prematurely explode. They would be detonated on contact with the ship or after a set time, although electrical detonators were also occasionally used. In 1862, the became the first warship to be sunk by an electrically-detonated mine. Spar torpedoes were also used; an explosive device was mounted at the end of a spar up to long projecting forward underwater from the bow of the attacking vessel, which would then ram the opponent with the explosives. These were used by the

Confederate

A confederation (also known as a confederacy or league) is a political union of sovereign states united for purposes of common action. Usually created by a treaty, confederations of states tend to be established for dealing with critical issu ...

submarine to sink the , although the weapon was apt to cause as much harm to its user as to its target.

Rear Admiral

Rear admiral is a flag officer rank used by English-speaking navies. In most European navies, the equivalent rank is called counter admiral.

Rear admiral is usually immediately senior to commodore and immediately below vice admiral. It is ...

David Farragut

David Glasgow Farragut (; also spelled Glascoe; July 5, 1801 ŌĆō August 14, 1870) was a flag officer of the United States Navy during the American Civil War. He was the first Rear admiral (United States), rear admiral, Vice admiral (United State ...

's famous/apocryphal command during the

Battle of Mobile Bay

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was a naval and land engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fle ...

in 1864, "

Damn the torpedoes, full speed ahead!

The Battle of Mobile Bay of August 5, 1864, was a naval and land engagement of the American Civil War in which a Union fleet commanded by Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, assisted by a contingent of soldiers, attacked a smaller Confederate fle ...

", refers to a minefield laid at

Mobile, Alabama

Mobile ( , ) is a city and the county seat of Mobile County, Alabama, United States. The population was 187,041 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. After a successful vote to annex areas west of the city limits in July 2023, Mobil ...

.

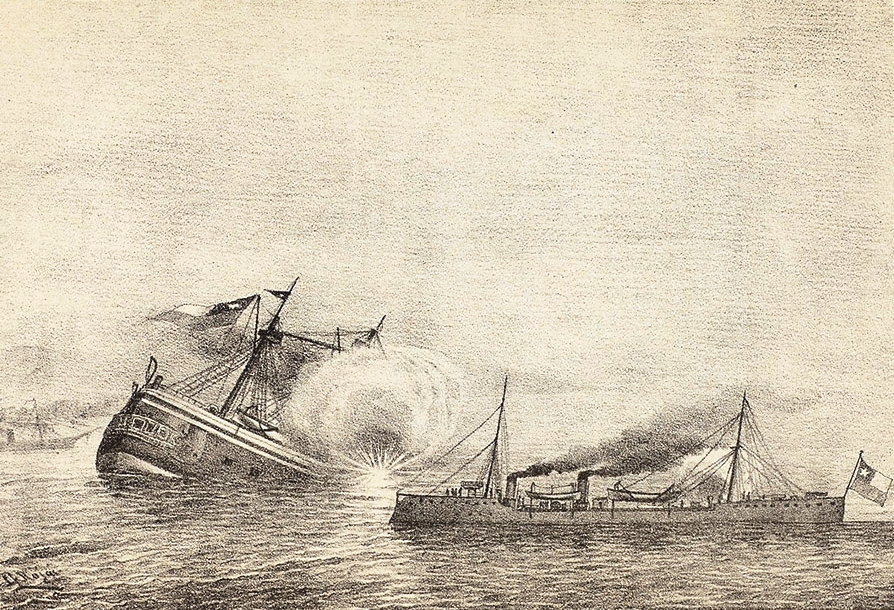

On 26 May 1877, during the

Romanian War of Independence

The Romanian War of Independence () is the name used in Romanian historiography to refer to the phase of the Russo-Turkish War (1877ŌĆō78), in which Romania, fighting on the Russian side of the war, gained independence from the Ottoman Empire. On ...

, the Romanian spar torpedo boat attacked and sank the Ottoman

river monitor

River monitors are military craft designed to patrol rivers.

They are normally the largest of all riverine warships in river flotillas, and mount the heaviest weapons. The name originated from the US Navy's , which made her first appearance in ...

''Seyfi''. This was the first instance in history when a torpedo boat sank its targets without also sinking.

Invention of the modern torpedo

A prototype of the self-propelled torpedo was created on a commission placed by

Giovanni Luppis

Giovanni (Ivan) Biagio Luppis Freiherr von Rammer (27 August 1813 – 11 January 1875), sometimes also known by the Croatian name of Vuki─ć, was an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Navy who headed a commission to develop the first prototypes o ...

, an

Austro-Hungarian naval officer from

Rijeka

Rijeka (;

Fiume ( łfju╦Éme in Italian and in Fiuman dialect, Fiuman Venetian) is the principal seaport and the List of cities and towns in Croatia, third-largest city in Croatia. It is located in Primorje-Gorski Kotar County on Kvarner Ba ...

(modern-day

Croatia

Croatia, officially the Republic of Croatia, is a country in Central Europe, Central and Southeast Europe, on the coast of the Adriatic Sea. It borders Slovenia to the northwest, Hungary to the northeast, Serbia to the east, Bosnia and Herze ...

), at the time a port city of the

Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

Austria-Hungary, also referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the Dual Monarchy or the Habsburg Monarchy, was a multi-national constitutional monarchy in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. A military and diplomatic alliance, it consist ...

and

Robert Whitehead, an English engineer who was the manager of a town factory, ''Stabilimento Tecnico di Fiume'' (STF). In 1864, Luppis presented Whitehead with the plans of the ''

Salvacoste

Giovanni (Ivan) Biagio Luppis Freiherr von Rammer (27 August 1813 – 11 January 1875), sometimes also known by the Croatian name of Vuki─ć, was an officer of the Austro-Hungarian Navy who headed a commission to develop the first prototypes o ...

'' ("Coastsaver"), a floating weapon driven by ropes from the land that had been dismissed by the naval authorities due to the impractical steering and propulsion mechanisms.

In 1866, Whitehead invented the first effective self-propelled torpedo, the eponymous

Whitehead torpedo

The Whitehead torpedo was the first self-propelled or "locomotive" torpedo ever developed. It was perfected in 1866 by British engineer Robert Whitehead from a rough design conceived by Giovanni Luppis of the Austro-Hungarian Navy in Fiume. I ...

, the first modern torpedo. French and German inventions followed closely, and the term ''torpedo'' came to describe self-propelled projectiles that traveled under or on water. By 1900, the term no longer included mines and booby-traps, as the navies of the world added submarines,

torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s, and

torpedo boat destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived in ...

s to their fleets.

Whitehead was unable to improve the machine substantially, since the clockwork motor, attached ropes, and surface attack mode all contributed to a slow and cumbersome weapon. However, he kept considering the problem after the contract had finished, and eventually developed a tubular device, designed to run underwater on its own, and powered by compressed air. The result was a submarine weapon, the ''Minenschiff'' (mine ship), the first modern self-propelled torpedo, officially presented to the Austrian Imperial Naval commission on 21 December 1866.

The first trials were not successful, as the weapon was unable to maintain a course at a steady depth. After much work, Whitehead introduced his "secret" in 1868 which overcame this. It was a mechanism consisting of a

hydrostatic valve and pendulum that caused the torpedo's hydroplanes to be adjusted to maintain a preset depth.

Production and spread

The Austrian government decided to invest in the invention, and the factory in Rijeka started producing more Whitehead torpedoes. In 1870, he improved the devices to travel up to approximately at a speed of up to .

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

(RN) representatives visited Rijeka for a demonstration in late 1869, and in 1870 a batch of torpedoes was ordered. In 1871, the British Admiralty paid Whitehead

┬Ż15,000 for certain of his developments, and production started at the Royal Laboratories in

Woolwich

Woolwich () is a town in South London, southeast London, England, within the Royal Borough of Greenwich.

The district's location on the River Thames led to its status as an important naval, military and industrial area; a role that was mainta ...

the following year.

The company in Fiume went bankrupt in 1873, but was reformed as

Whitehead Torpedo Works Whitehead Torpedo Works was a company established in the 19th century by Robert Whitehead (engineer), Robert Whitehead that developed the Whitehead torpedo. It grew from its initial location at Fiume to Wyke Regis and to Livorno, but the former two ...

a few years later, and by 1881 it was exporting torpedoes to ten other countries. The torpedo was powered by compressed air and had an explosive charge of

gun-cotton

Nitrocellulose (also known as cellulose nitrate, flash paper, flash cotton, guncotton, pyroxylin and flash string, depending on form) is a highly flammable compound formed by nitrating cellulose through exposure to a mixture of nitric acid and ...

. Whitehead went on to develop more efficient devices, demonstrating torpedoes capable of in 1876, in 1886, and, finally, in 1890.

In the 1880s, a British committee, informed by hydrodynamicist Dr.

R. E. Froude, conducted comparative tests and determined that a blunt nose, contrary to prior assumptions, did not hinder speed: in fact, the blunt nose provided a speed advantage of approximately one knot compared to the traditional pointed-nose design. This discovery allowed for larger explosive payloads and increased air storage for propulsion without compromising speed.

Whitehead opened a new factory adjacent to

Portland Harbour

Portland Harbour is beside the Isle of Portland, Dorset, on the south coast of England. Construction of the harbour began in 1849; when completed in 1872, its surface area made it the largest human-made harbour in the world, and it remains ...

, England, in 1890, which continued making torpedoes until the end of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 ŌĆō 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. Because orders from the RN were not as large as expected, torpedoes were mostly exported. A series of devices was produced at Rijeka, with diameters from upward. The largest Whitehead torpedo was in diameter and long, made of polished steel or

phosphor bronze

A phosphor is a substance that exhibits the optical phenomenon, phenomenon of luminescence; it emits light when exposed to some type of radiant energy. The term is used both for fluorescence, fluorescent or phosphorescence, phosphorescent sub ...

, with a gun-cotton warhead. It was propelled by a three-cylinder

Brotherhood

Brotherhood or The Brotherhood may refer to:

Family, relationships, and organizations

* Fraternity (philosophy) or brotherhood, an ethical relationship between people, which is based on love and solidarity

* Fraternity or brotherhood, a male ...

radial engine, using compressed air at around and driving two

contra-rotating

Contra-rotating, also referred to as coaxial contra-rotating, is a technique whereby parts of a mechanism rotate in opposite directions about a common axis, usually to minimise the effect of torque. Examples include some aircraft propellers, r ...

propellers, and was designed to self-regulate its course and depth as far as possible. By 1881, nearly 1,500 torpedoes had been produced. Whitehead also opened a factory at

St Tropez

Saint-Tropez ( , ; ) is a commune in the Var department and the region of Provence-Alpes-C├┤te d'Azur, Southern France. It is west of Nice and east of Marseille, on the French Riviera, of which it is one of the best-known towns. In 2018, S ...

in 1890 that exported torpedoes to Brazil, the Netherlands, Turkey, and Greece.

Whitehead purchased rights to the

gyroscope

A gyroscope (from Ancient Greek ╬│ß┐”Žü╬┐Žé ''g┼Ęros'', "round" and Žā╬║╬┐ŽĆ╬ŁŽē ''skop├®┼Ź'', "to look") is a device used for measuring or maintaining Orientation (geometry), orientation and angular velocity. It is a spinning wheel or disc in ...

of

Ludwig Obry

Ludwig Obry was an Austrian engineer and naval officer of the Austrian Navy who invented a gyroscopic device for steering a torpedo in 1895.

The gyroscope had been invented by Leon Foucault in 1851, but industry ignored the device for nearly ...

in 1888, but it was not sufficiently accurate, so in 1890 he purchased a better design to improve control of his designs, which came to be called the "Devil's Device". The firm of

L. Schwartzkopff in Germany also produced torpedoes and exported them to Russia, Japan, and Spain. In 1885, Britain ordered a batch of 50 as torpedo production at home and Rijeka could not meet demand.

In 1893, Royal Navy torpedo production was transferred to the

Royal Gun Factory

The Royal Arsenal, Woolwich is an establishment on the south bank of the River Thames in Woolwich in south-east London, England, that was used for the manufacture of armaments and ammunition, proofing, and explosives research for the British ...

. The British later established a

Torpedo Experimental Establishment

The Torpedo Experimental Establishment (T.E.E.) also known as the Admiralty Torpedo Experimental Establishment was a former research department of the British Department of Admiralty from 1947 to 1959. It was responsible for the design, developm ...

at and a production facility at the

Royal Naval Torpedo Factory,

Greenock

Greenock (; ; , ) is a town in Inverclyde, Scotland, located in the west central Lowlands of Scotland. The town is the administrative centre of Inverclyde Council. It is a former burgh within the historic county of Renfrewshire, and forms ...

, in 1910. These are now closed.

By World War I, Whitehead's torpedo remained a worldwide success, and his company was able to maintain a monopoly on torpedo production. By that point, his torpedo had grown to a diameter of with a maximum speed of with a warhead weighing .

Whitehead faced competition from the American

Lieutenant Commander John A. Howell, whose

design

A design is the concept or proposal for an object, process, or system. The word ''design'' refers to something that is or has been intentionally created by a thinking agent, and is sometimes used to refer to the inherent nature of something ...

, driven by a

flywheel

A flywheel is a mechanical device that uses the conservation of angular momentum to store rotational energy, a form of kinetic energy proportional to the product of its moment of inertia and the square of its rotational speed. In particular, a ...

, was simpler and cheaper. It was produced from 1885 to 1895, and it ran straight, leaving no wake. A Torpedo Test Station was set up in

Rhode Island

Rhode Island ( ) is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders Connecticut to its west; Massachusetts to its north and east; and the Atlantic Ocean to its south via Rhode Island Sound and Block Is ...

in 1870. The Howell torpedo was the only

United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

model until an American company,

Bliss and Williams, secured manufacturing rights to produce Whitehead torpedoes. These were put into service for the U.S. Navy in 1892. Five varieties were produced, all in diameter.

The Royal Navy introduced the Brotherhood wet heater engine in 1907 with the

Mk. VII & VII*, which greatly increased the speed and range over compressed-air engines, and wet heater type engines became the standard in many major navies up to and during the Second World War.

Torpedo boats and guidance systems

Ships of the line

A ship of the line was a type of naval warship constructed during the Age of Sail from the 17th century to the mid-19th century. The ship of the line was designed for the naval tactic known as the line of battle, which involved the two column ...

were superseded by

ironclads

An ironclad was a steam-propelled warship protected by steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or incendiary shells. The firs ...

, large steam-powered ships with heavy gun armament and heavy armor, in the mid-19th century. Ultimately this line of development led to the

dreadnought

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

category of all-big-gun battleships, starting with .

Although these ships were incredibly powerful, the new weight of armor slowed them down, and the huge guns needed to penetrate that armor fired at very slow rates. The development of torpedoes allowed for the possibility that small and fast vessels could credibly threaten if not sink even the most powerful battleships. While such attacks would carry enormous risks to the attacking boats and their crews (which would likely need to expose themselves to artillery fire which their small vessels were not designed to withstand), this was offset by the ability to construct large numbers of small vessels far more quickly and for a much lower unit cost compared to a capital ship.

The first boat designed to fire the self-propelled

Whitehead torpedo

The Whitehead torpedo was the first self-propelled or "locomotive" torpedo ever developed. It was perfected in 1866 by British engineer Robert Whitehead from a rough design conceived by Giovanni Luppis of the Austro-Hungarian Navy in Fiume. I ...

was , completed in 1877. The

French Navy

The French Navy (, , ), informally (, ), is the Navy, maritime arm of the French Armed Forces and one of the four military service branches of History of France, France. It is among the largest and most powerful List of navies, naval forces i ...

followed suit in 1878 with , launched in 1878, though she had been ordered in 1875. The first torpedo boats were built at the shipyards of Sir

John Thornycroft and gained recognition for their effectiveness.

At the same time, inventors were working on building a guided torpedo. Prototypes were built by

John Ericsson

John Ericsson (born Johan Ericsson; July 31, 1803 ŌĆō March 8, 1889) was a Swedish-American engineer and inventor. He was active in England and the United States.

Ericsson collaborated on the design of the railroad steam locomotive Novelty (lo ...

,

John Louis Lay

John Louis Lay (January 14, 1833 ŌĆō April 17, 1899) was an American inventor, and a pioneer of the torpedo.

Biography

Lay was born in Buffalo, New York. He was appointed 2nd assistant engineer in the Union Navy on July 8, 1862, and was promoted ...

, and Victor von Scheliha, but the first practical guided missile was patented by

Louis Brennan

Louis Brennan (28 January 1852 ŌĆō 17 January 1932) was an Irish-Australian mechanical engineer and inventor. He is best known for inventing the Brennan Torpedo, one of the earliest wire-guided torpedoes, which was adopted by the British Army i ...

, an emigre to Australia, in 1877.

[

It was designed to run at a consistent depth of , and was fitted with an indicator mast that just broke the surface of the water. At night the mast had a small light, visible only from the rear. Two steel drums were mounted one behind the other inside the torpedo, each carrying several thousand metres of high-tensile steel wire. The drums connected via a ]differential gear

A differential is a gear train with three drive shafts that has the property that the rotational speed of one shaft is the average of the speeds of the others. A common use of differentials is in motor vehicles, to allow the wheels at each en ...

to twin contra-rotating

Contra-rotating, also referred to as coaxial contra-rotating, is a technique whereby parts of a mechanism rotate in opposite directions about a common axis, usually to minimise the effect of torque. Examples include some aircraft propellers, r ...

propellers. If one drum was rotated faster than the other, then the rudder was activated. The other ends of the wires were connected to steam-powered winding engines, which were arranged so that speeds could be varied within fine limits, giving sensitive steering control for the torpedo.

The torpedo attained a speed of using a wire in diameter, but later this was changed to to increase the speed to . The torpedo was fitted with elevators controlled by a depth-keeping mechanism, and the fore and aft rudders operated by the differential between the drums.[The Brennan Torpedo by Alec Beanse ]

Brennan traveled to Britain, where the Admiralty examined the torpedo and found it unsuitable for shipboard use. However, the War Office

The War Office has referred to several British government organisations throughout history, all relating to the army. It was a department of the British Government responsible for the administration of the British Army between 1857 and 1964, at ...

proved more amenable, and in early August 1881, a special Royal Engineer

The Corps of Royal Engineers, usually called the Royal Engineers (RE), and commonly known as the ''Sappers'', is the engineering arm of the British Army. It provides military engineering and other technical support to the British Armed Forces ...

committee was instructed to inspect the torpedo at Chatham and report back directly to the Secretary of State for War, Hugh Childers

Hugh Culling Eardley Childers (25 June 1827 ŌĆō 29 January 1896) was a British Liberal statesman of the nineteenth century. He is perhaps best known for his reform efforts at the Admiralty and the War Office. Later in his career, as Chancel ...

. The report strongly recommended that an improved model be built at government expense. In 1883 an agreement was reached between the Brennan Torpedo Company and the government. The newly appointed Inspector-General of Fortifications in England, Sir Andrew Clarke, appreciated the value of the torpedo, and in spring 1883 an experimental station was established at Garrison Point Fort

Garrison Point Fort is a former artillery fort situated at the end of the Garrison Point peninsula at Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. Built in the 1860s in response to concerns about a possible French invasion, it was the last in a ser ...

, Sheerness

Sheerness () is a port town and civil parish beside the mouth of the River Medway on the north-west corner of the Isle of Sheppey in north Kent, England. With a population of 13,249, it is the second largest town on the island after the nearby ...

, on the River Medway

The River Medway is a river in South East England. It rises in the High Weald AONB, High Weald, West Sussex and flows through Tonbridge, Maidstone and the Medway conurbation in Kent, before emptying into the Thames Estuary near Sheerness, a to ...

, and a workshop for Brennan was set up at the Chatham Barracks, the home of the Royal Engineers. Between 1883 and 1885 the Royal Engineers held trials, and in 1886 the torpedo was recommended for adoption as a harbor defense torpedo. It was used throughout the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

for more than fifteen years.

Use in conflict

The

The Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

frigate was the first naval vessel to fire a self-propelled torpedo in anger during the Battle of Pacocha

The Battle of Pacocha was a naval battle that took place on 29 May 1877 between the rebel-held Peruvian monitor ''Hu├Īscar'' and the British ships and . The vessels did not inflict significant damage on each other, however the battle is nota ...

against rebel Peruvian ironclad on 29 May 1877. The Peruvian ship successfully outran the device. On 16 January 1878, the Turkish steamer ''Intibah'' became the first vessel to be sunk by self-propelled torpedoes, launched from torpedo boats operating from the tender under the command of Stepan Osipovich Makarov

Stepan Osipovich Makarov (, ; ŌĆō ) was a Russian vice-admiral, commander in the Imperial Russian Navy, oceanographer, member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and author of several books. He was a pioneer of insubmersibility theory (the ...

during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877ŌĆō78.

In another early use of the torpedo, during the War of the Pacific

The War of the Pacific (), also known by War of the Pacific#Etymology, multiple other names, was a war between Chile and a Treaty of Defensive Alliance (BoliviaŌĆōPeru), BolivianŌĆōPeruvian alliance from 1879 to 1884. Fought over Atacama Desert ...

, the Peruvian ironclad

An ironclad was a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by iron armour, steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or ince ...

Hu├Īscar

Hu├Īscar (; Quechua: ''Waskar Inka'') also Guazcar (before 15271532) was Sapa Inca of the Inca Empire from 1527 to 1532. He succeeded his father, Huayna Capac and his brother Ninan Cuyochi, both of whom died of smallpox during the same year ...

commanded by captain Miguel Grau

Miguel Mar├Ła Grau Seminario (27 July 1834 ŌĆō 8 October 1879) was a Peruvian Navy officer and politician best known for his actions during the War of the Pacific. He was nicknamed "Gentleman of the Seas" for his kind and chivalrous treatment ...

attacked the Chilean corvette Abtao

The corvette ''Abtao'' was a wooden ship built in Scotland during 1864 of 1.600 tons and 800 IHP. She fought in the War of the Pacific and was in service for the Chilean Navy until 1922.

__TOC__

Two hulls in Glasgow

During the Chincha Islands ...

on 28 August 1879 at Antofagasta

Antofagasta () is a port city in northern Chile, about north of Santiago. It is the capital of Antofagasta Province and Antofagasta Region. According to the 2015 census, the city has a population of 402,669.

Once claimed by Bolivia follo ...

with a self-propelled Lay torpedo

Lay or LAY may refer to:

Places

*Lay Range, a subrange of mountains in British Columbia, Canada

*Lay, Loire, a French commune

*Lay (river), France

*Lay, Iran, a village

*Lay, Kansas, United States, an unincorporated community

*Lay Dam, Alabama, ...

only to have it reverse course. The ''Huascar'' was saved when an officer jumped overboard to divert it.

The Chilean ironclad

An ironclad was a steam engine, steam-propelled warship protected by iron armour, steel or iron armor constructed from 1859 to the early 1890s. The ironclad was developed as a result of the vulnerability of wooden warships to explosive or ince ...

was sunk on 23 April 1891 by a self-propelled torpedo from the ''Almirante Lynch'', during the Chilean Civil War of 1891

The Chilean Civil War of 1891 (also known as Revolution of 1891) was a civil war in Chile fought between forces supporting Congress of Chile, Congress and forces supporting the President of Chile, President, Jos├® Manuel Balmaceda from 16 Ja ...

, becoming the first ironclad warship sunk by this weapon. The Chinese turret ship

Turret ships were a 19th-century type of warship, the earliest to have their guns mounted in a revolving gun turret, instead of a broadside arrangement.

Background

Before the development of large-calibre, long-range guns in the mid-19th centur ...

was purportedly hit and disabled by a torpedo after numerous attacks by Japanese torpedo boats during the First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 189417 April 1895), or the First ChinaŌĆōJapan War, was a conflict between the Qing dynasty of China and the Empire of Japan primarily over influence in Joseon, Korea. In Chinese it is commonly known as th ...

in 1894. At this time torpedo attacks were still very close range and very dangerous to the attackers.

Several western sources reported that the Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing, was a Manchu-led Dynasties of China, imperial dynasty of China and an early modern empire in East Asia. The last imperial dynasty in Chinese history, the Qing dynasty was preceded by the ...

Imperial Chinese military, under the direction of Li Hongzhang

Li Hongzhang, Marquess Suyi ( zh, t=µØÄķ┤╗ń½Ā; also Li Hung-chang; February 15, 1823 ŌĆō November 7, 1901) was a Chinese statesman, general and diplomat of the late Qing dynasty. He quelled several major rebellions and served in importan ...

, acquired ''electric torpedoes,'' which they deployed in numerous waterways, along with fortresses and numerous other modern military weapons acquired by China. At the Tientsin

Tianjin is a direct-administered municipality in northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities, with a total population of 13,866,009 inhabitants at the time of the 2020 Chinese census. Its metropoli ...

Arsenal in 1876, the Chinese developed the capacity to manufacture these "electric torpedoes" on their own. Although a form of Chinese art, the Nianhua

A New Year picture () is a popular Banhua in China. It is a form of colored woodblock print, used for decoration and the performance of rituals during the Chinese New Year Holiday. In the 19th and 20th centuries some printers began to use the g ...

, depict such torpedoes being used against Russian ships during the Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, was an anti-foreign, anti-imperialist, and anti-Christian uprising in North China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by the Society of Righteous and Harmonious F ...

, whether they were actually used in battle against them is undocumented and unknown.

The Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 ŌĆō 5 September 1905) was fought between the Russian Empire and the Empire of Japan over rival imperial ambitions in Manchuria and the Korean Empire. The major land battles of the war were fought on the ...

(1904ŌĆō1905) was the first great war of the 20th century. During the war, the Imperial Russian

The Russian Empire was an empire that spanned most of northern Eurasia from its establishment in November 1721 until the proclamation of the Russian Republic in September 1917. At its height in the late 19th century, it covered about , roughl ...

and Imperial Japanese

The Empire of Japan, also known as┬Āthe Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was the Japanese nation state that existed from the Meiji Restoration on January 3, 1868, until the Constitution of Japan took effect on May 3, 1947. From 1910 to 19 ...

navies launched nearly 300 torpedoes at each other, all of them of the "self-propelled automotive" type. The deployment of these new underwater weapons resulted in one battleship, two armored cruisers, and two destroyers being sunk in action, with the remainder of the roughly 80 warships being sunk by the more conventional methods of gunfire, mines, and scuttling

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vessel ...

.

On 27 May 1905, during the Battle of Tsushima

The Battle of Tsushima (, ''Tsusimskoye srazheniye''), also known in Japan as the , was the final naval battle of the Russo-Japanese War, fought on 27ŌĆō28 May 1905 in the Tsushima Strait. A devastating defeat for the Imperial Russian Navy, the ...

, Admiral Rozhestvensky

Zinovy Petrovich Rozhestvensky (, Romanization of Russian, tr. ; ŌĆō January 14, 1909) was a Imperial Russia, Russian admiral of the Imperial Russian Navy. He was in command of the Second Pacific Squadron in the Battle of Tsushima, during the R ...

's flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

, the battleship , had been gunned to a wreck by Admiral T┼Źg┼Ź's battleline

The line of battle or the battle line is a tactic in naval warfare in which a fleet of ships (known as ships of the line) forms a line end to end. The first example of its use as a tactic is disputedŌĆöit has been variously claimed for date ...

. With the Russians sunk and scattering, T┼Źg┼Ź prepared for pursuit, and while doing so ordered his torpedo boat destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived in ...

s (TBDs) (mostly referred to as just ''destroyers'' in most written accounts) to finish off the Russian battleship. ''Knyaz Suvorov'' was set upon by seventeen torpedo-firing warships, ten of which were destroyers and four torpedo boats. Twenty-one torpedoes were launched at the pre-dreadnought

Pre-dreadnought battleships were sea-going battleships built from the mid- to late- 1880s to the early 1900s. Their designs were conceived before the appearance of in 1906 and their classification as "pre-dreadnought" is retrospectively appl ...

, and three struck home, one fired from the destroyer and two from torpedo boats ''No. 72'' and ''No. 75''. The flagship slipped under the waves shortly thereafter, taking over 900 men with her to the bottom.

On December 9, 1912, the Greek submarine "Dolphin" launched a torpedo against the Ottoman cruiser "Medjidieh".

Aerial torpedo

The end of the Russo-Japanese War fueled new theories, and the idea of dropping lightweight torpedoes from aircraft was conceived in the early 1910s by Bradley A. Fiske, an officer in the

The end of the Russo-Japanese War fueled new theories, and the idea of dropping lightweight torpedoes from aircraft was conceived in the early 1910s by Bradley A. Fiske, an officer in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

.[Hopkins, Albert Allis. ''The Scientific American War Book: The Mechanism and Technique of War'', Chapter XLV: Aerial Torpedoes and Torpedo Mines. Munn & Company, Incorporated, 1915] Awarded a patent in 1912,[Hart, Albert Bushnell. ''Harper's pictorial library of the world war, Volume 4''. Harper, 1920, p. 335.] Fiske worked out the mechanics of carrying and releasing the aerial torpedo

An aerial torpedo (also known as an airborne torpedo or air-dropped torpedo) is a torpedo launched from a torpedo bomber aircraft into the water, after which the weapon propels itself to the target.

First used in World War I, air-dropped torped ...

from a bomber

A bomber is a military combat aircraft that utilizes

air-to-ground weaponry to drop bombs, launch aerial torpedo, torpedoes, or deploy air-launched cruise missiles.

There are two major classifications of bomber: strategic and tactical. Strateg ...

, and defined tactics that included a night-time approach so that the target ship would be less able to defend itself. Fiske determined that the notional torpedo bomber

A torpedo bomber is a military aircraft designed primarily to attack ships with aerial torpedoes. Torpedo bombers came into existence just before the World War I, First World War almost as soon as aircraft were built that were capable of carryin ...

should descend rapidly in a sharp spiral to evade enemy guns, then when about above the water, the aircraft would straighten its flight long enough to line up with the torpedo's intended path. The aircraft would release the torpedo at a distance of from the target.[ Fiske reported in 1915 that, using this method, enemy fleets could be attacked within their harbors if there was enough room for the torpedo track.

Meanwhile, the ]Royal Naval Air Service

The Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) was the air arm of the Royal Navy, under the direction of the Admiralty (United Kingdom), Admiralty's Air Department, and existed formally from 1 July 1914 to 1 April 1918, when it was merged with the British ...

began actively experimenting with this possibility. The first successful aerial torpedo drop was performed by Gordon Bell in 1914 ŌĆō dropping a Whitehead torpedo from a Short S.64 seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

. The success of these experiments led to the construction of the first purpose-built operational torpedo aircraft, the Short Type 184

The Short Admiralty Type 184, often called the Short 225 after the power rating of the engine first fitted, was a British two-seat reconnaissance, bombing and torpedo carrying folding-wing seaplane designed by Horace Short of Short Brothers. It ...

, built-in 1915.

An order for ten aircraft was placed, and 936 aircraft were built by ten different British aircraft companies during the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 ŌĆō 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The two prototype aircraft were embarked upon , which sailed for the Aegean on 21 March 1915 to take part in the Gallipoli campaign. On 12 August 1915 one of these, piloted by Flight Commander

A flight commander is the leader of a constituent portion of an aerial squadron in aerial operations, often into combat. That constituent portion is known as a flight, and usually contains six or fewer aircraft, with three or four being a common ...

Charles Edmonds

Air Vice Marshal Charles Humphrey Kingsman Edmonds, (20 April 1891 ŌĆō 26 September 1954) was an air officer of the Royal Air Force (RAF).

He first served in the Royal Navy and was a naval aviator during the First World War, taking part in the ...

, was the first aircraft in the world to attack an enemy ship with an air-launched torpedo.tug

A tugboat or tug is a marine vessel that manoeuvres other vessels by pushing or pulling them, with direct contact or a tow line. These boats typically tug ships in circumstances where they cannot or should not move under their own power, suc ...

close by, taxied up to it and released his torpedo, sinking the tug. Without the weight of the torpedo, Dacre was able to take off and return to ''Ben-My-Chree''.

World War I

Torpedoes were widely used in World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 ŌĆō 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, both against shipping and against submarines.[ Two Royal Italian Navy ]torpedo boats

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

scored a success against an Austrian-Hungarian squadron, sinking the battleship with two torpedoes.

The Royal Navy had been experimenting with ways to further increase the range of torpedoes during World War 1 using pure oxygen instead of compressed air, this work ultimately leading to the development of the oxygen-enriched air Mk. I intended originally for the s and battleships of 1921, both of which were cancelled due to the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

.

Initially, the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, Potsdam Declaration, when it was dissolved followin ...

purchased Whitehead or Schwartzkopf torpedoes but by 1917, like the Royal Navy, they were conducting experiments with pure oxygen instead of compressed air. Because of explosions, they abandoned the experiments but resumed them in 1926 and by 1933 had a working torpedo. They also used conventional wet heater

Wet may refer to:

* Moisture, the condition of containing liquid or being covered or saturated in liquid

* Wetting (or wetness), a measure of how well a liquid sticks to a solid rather than forming a sphere on the surface

Wet or WET may also refe ...

torpedoes.

World War II

In the inter-war years

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period, also known as the interbellum (), lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days) ŌĆō from the end of World War I (WWI) to the beginning of World War II ( ...

, financial stringency caused nearly all navies to skimp on testing their torpedoes. Only the British and Japanese had fully tested new technologies for torpedoes (in particular the Type 93, nicknamed ''Long Lance'' postwar by the US official historian Samuel E. Morison)Pacific Theater

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean, or, depending on the definition, to Antarctica in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

. One possible exception to the pre-war neglect of torpedo development was the , 1931-premiered Japanese Type 91 torpedo

The Type 91 was an aerial torpedo of the Imperial Japanese Navy. It was in service from 1931 to 1945. It was used in naval battles in World War II and was specially developed for attacks on ships in shallow harbours.

The Type 91 aerial torped ...

, the sole aerial torpedo (''Koku Gyorai'') developed and brought into service by the Japanese Empire before the war. The Type 91 had an advanced PID controller

PID or Pid may refer to:

Medicine

* Pelvic inflammatory disease or pelvic inflammatory disorder, an infection of the upper part of the female reproductive system

* Primary immune deficiency, disorders in which part of the body's immune system is ...

and jettisonable, wooden '' Kyoban'' aerial stabilizing surfaces which released upon entering the water, making it a formidable anti-ship weapon; Nazi Germany considered manufacturing it as the ''Luftorpedo LT 850'' after August 1942.

The Royal Navy's oxygen-enriched air torpedo saw service in the two battleships, although by World War II, the use of enriched oxygen had been discontinued due to safety concerns.['' Washington's Cherry trees, The Evolution of the British 1921-22 Capital Ships'', NJM Campbell, Warship Volume 1, Conway Maritime Press, Greenwich, , pp. 9-10.] In the final phase of the action against , fired a pair of torpedoes from her port-side tube and claimed one hit. According to Ludovic Kennedy

Sir Ludovic Henry Coverley Kennedy, (3 November 191918 October 2009) was a Scottish journalist, broadcaster, humanist and author. As well as his wartime service in the Royal Navy, he is known for presenting many current affairs programmes and ...

, "if true, his isthe only instance in history of one battleship torpedoing another". The Royal Navy continued the development of oxygen-enriched air torpedoes with the Mk. VII of the 1920s designed for the s although once again these were converted to run on normal air at the start of World War II. Around this time too the Royal Navy were perfecting the Brotherhood burner cycle engine which offered a performance as good as the oxygen-enriched air engine but without the issues arising from the oxygen equipment and which was first used in the extremely successful and long-lived Mk. VIII torpedo of 1925. This torpedo served throughout WWII (with 3,732 being fired by September 1944) and is still in limited service in the 21st century. The improved Mark VIII** was used in two particularly notable incidents: on 6 February 1945, the only intentional wartime sinking of one submarine by another while both were submerged took place when HMS ''Venturer'' sank the German submarine ''U-864'' with four Mark VIII** torpedoes, and on 2 May 1982 the Royal Navy submarine sank the Argentine cruiser with two Mark VIII** torpedoes during the Falklands War

The Falklands War () was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British Overseas Territories, British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and Falkland Islands Dependenci ...

.India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

n frigate and the South Korean corvette ROKS ''Cheonan''.

Many classes of surface ships, submarines, and aircraft were armed with torpedoes. Naval strategy at the time was to use torpedoes, launched from submarines or warships, against enemy warships in a fleet action on the high seas. There were concerns that torpedoes would be ineffective against warships' heavy armor; an answer to this was to detonate torpedoes underneath a ship, badly damaging its

Many classes of surface ships, submarines, and aircraft were armed with torpedoes. Naval strategy at the time was to use torpedoes, launched from submarines or warships, against enemy warships in a fleet action on the high seas. There were concerns that torpedoes would be ineffective against warships' heavy armor; an answer to this was to detonate torpedoes underneath a ship, badly damaging its keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

and the other structural members in the hull, commonly called "breaking its back". This was demonstrated by magnetic influence mines in World War I. The torpedo would be set to run at a depth just beneath the ship, relying on a magnetic exploder to activate at the appropriate time.

Germany, Britain, and the U.S. independently devised ways to do this; German and American torpedoes, however, suffered problems with their depth-keeping mechanisms, coupled with faults in magnetic pistol

Magnetic pistol is the term for the device on a torpedo or naval mine that detects its target by its magnetic field, and triggers the fuse for detonation. A device to detonate a torpedo or mine on ''contact'' with a ship or submarine is known as a ...

s shared by all designs. Inadequate testing had failed to reveal the effect of the Earth's magnetic field on ships and exploder mechanisms, which resulted in premature detonation. The ''Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871ŌĆō1918) and the inter-war (1919ŌĆō1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official military branch, branche ...

'' and Royal Navy promptly identified and eliminated the problems. In the United States Navy (USN), there was an extended wrangle over the problems plaguing the Mark 14 torpedo

The Mark 14 torpedo was the United States Navy's standard submarine-launched anti-ship torpedo of World War II. This weapon was plagued with many problems which crippled its performance early in the war. It was supplemented by the Mark 18 el ...

(and its Mark 6 exploder

The Mark 6 exploder was a United States Navy torpedo exploder developed in the 1920s. It was the standard exploder of the Navy's Mark 14 torpedo and Mark 15 torpedo.

Development

Early torpedoes used contact exploders. A typical exploder had a ...

). Cursory trials had allowed bad designs to enter service, and both the Navy Bureau of Ordnance

The Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) was a United States Navy organization, which was responsible for the procurement, storage, and deployment of all naval weapons, between the years 1862 and 1959.

History

The Bureau of Ordnance was established as part ...

and the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature, legislative branch of the federal government of the United States. It is a Bicameralism, bicameral legislature, including a Lower house, lower body, the United States House of Representatives, ...

were too busy protecting their interests to correct the errors. Fully functioning torpedoes only became available to the USN twenty-one months into the Pacific War.

British submarines used torpedoes to interdict the Axis supply shipping to North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

, while Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is the naval aviation component of the United Kingdom's Royal Navy (RN). The FAA is one of five :Fighting Arms of the Royal Navy, RN fighting arms. it is a primarily helicopter force, though also operating the Lockhee ...

Swordfish

The swordfish (''Xiphias gladius''), also known as the broadbill in some countries, are large, highly migratory predatory fish characterized by a long, flat, pointed bill. They are the sole member of the Family (biology), family Xiphiidae. They ...

sank three Italian battleships at Taranto by a torpedo and (after a mistaken, but abortive, attack on ) scored one crucial hit in the hunt for the German battleship . Large tonnages of merchant shipping were sunk by submarines with torpedoes in both the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allies of World War II, ...

and the Pacific War.

Torpedo boats, such as MTBs, PT boat

A PT boat (short for patrol torpedo boat) was a motor torpedo boat used by the United States Navy in World War II. It was small, fast, and inexpensive to build, and it was valued for its maneuverability and speed. However, PT boats were hampe ...

s, or S-boats, enabled the relatively small but fast craft to carry enough firepower, in theory, to destroy a larger ship, though this rarely occurred in practice. The largest warship sunk by torpedoes from small craft in World War II was the British cruiser , sunk by Italian MAS boats on the night of 12/13 August 1942 during Operation Pedestal

Operation Pedestal (, Battle of mid-August), known in Malta as (), was a British operation to carry supplies to the island of Malta in August 1942, during the Second World War. British ships, submarines and aircraft from Malta attacked Axis p ...

. Destroyers of all navies were also armed with torpedoes to attack larger ships. In the Battle off Samar

The Battle off Samar was the centermost action of the Battle of Leyte Gulf, one of the largest naval battle in history, largest naval battles in history, which took place in the Philippine Sea off Samar (island), Samar Island, in the Philippin ...

, destroyer torpedoes from the escorts of the American task force "Taffy 3" showed effectiveness at defeating armor. Damage and confusion caused by torpedo attacks were instrumental in beating back a superior Japanese force of battleships and cruisers. In the Battle of the North Cape

The Battle of the North Cape was a Second World War naval battle that occurred on 26 December 1943, as part of the Arctic campaign. The , on an operation to attack Arctic convoys of war materiel from the western Allies to the Soviet Union, ...

in December 1943, torpedo hits from British destroyers and slowed the German battleship enough for the British battleship to catch and sink her, and in May 1945 the British 26th Destroyer Flotilla (coincidentally led by ''Saumarez'' again) ambushed and sank Japanese heavy cruiser .

As a result of the "Channel Dash

The Channel Dash (, Operation Cerberus) was a German naval operation during the Second World War. A (German Navy) squadron comprising two s, and , the heavy cruiser and their escorts was evacuated from Brest in Brittany to German ports. '' ...

" of 1942, when three German warships successfully evaded Royal Navy and Royal Air Force attacks and passed the length of the English Channel

The English Channel, also known as the Channel, is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that separates Southern England from northern France. It links to the southern part of the North Sea by the Strait of Dover at its northeastern end. It is the busi ...

from the Atlantic to the North Sea, Britain's Ministry of Aircraft Production

Ministry may refer to:

Government

* Ministry (collective executive), the complete body of government ministers under the leadership of a prime minister

* Ministry (government department), a department of a government

Religion

* Christian mi ...

commissioned the Helmover torpedo

The Helmover torpedo or Helmore projector was a British air-launched, radio-directed torpedo developed in 1944. It was intended for action against enemy shipping but was not brought into military use because of the surrender of the Japanese navy in ...

, a five-ton air-launched weapon, but it did not enter service until 1945 and saw no action.

Frequency-hopping

During World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 ŌĆō 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, Hedy Lamarr

Hedy Lamarr (; born Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler; November 9, 1914 January 19, 2000) was an Austrian-born American actress and inventor. After a brief early film career in Czechoslovakia, including the controversial erotic romantic drama '' Ecstasy ...

and composer George Antheil

George Johann Carl Antheil ( ; July 8, 1900 ŌĆō February 12, 1959) was an American avant-garde composer, pianist, author, and inventor whose modernist musical compositions explored the sounds ŌĆō musical, industrial, and mechanical ŌĆō of the ear ...

developed a radio guidance system for Allied torpedoes; it intended to use frequency-hopping

Frequency-hopping spread spectrum (FHSS) is a method of transmitting radio signals by rapidly changing the carrier frequency among many frequencies occupying a large spectral band. The changes are controlled by a code known to both transmitter ...

technology to defeat the threat of jamming by the Axis powers

The Axis powers, originally called the RomeŌĆōBerlin Axis and also RomeŌĆōBerlinŌĆōTokyo Axis, was the military coalition which initiated World War II and fought against the Allies of World War II, Allies. Its principal members were Nazi Ge ...

. As radio guidance had been abandoned some years earlier, it was not pursued.US Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the naval warfare, maritime military branch, service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is the world's most powerful navy with the largest Displacement (ship), displacement, at 4.5 millio ...

never adopted the technology, it did, in the 1960s, investigate various spread-spectrum techniques. Spread-spectrum techniques are incorporated into Bluetooth

Bluetooth is a short-range wireless technology standard that is used for exchanging data between fixed and mobile devices over short distances and building personal area networks (PANs). In the most widely used mode, transmission power is li ...

technology and are similar to methods used in legacy versions of Wi-Fi

Wi-Fi () is a family of wireless network protocols based on the IEEE 802.11 family of standards, which are commonly used for Wireless LAN, local area networking of devices and Internet access, allowing nearby digital devices to exchange data by ...

.["Hollywood star whose invention paved the way for Wi-Fi"](_blank)

''New Scientist'', December 8, 2011; retrieved February 4, 2014.National Inventors Hall of Fame

The National Inventors Hall of Fame (NIHF) is an American not-for-profit organization, founded in 1973, which recognizes individual engineers and inventors who hold a US patent of significant technology. Besides the Hall of Fame, it also operate ...

in 2014.

PostŌĆōWorld War II

Because of improved submarine strength and speed, torpedoes had to be given improved warheads and better motors. During the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, torpedoes were an important asset with the advent of nuclear-powered submarine

A nuclear submarine is a submarine powered by a nuclear reactor, but not necessarily nuclear-armed.

Nuclear submarines have considerable performance advantages over "conventional" (typically diesel-electric) submarines. Nuclear propulsion, ...

s, which did not have to surface often, particularly those carrying strategic nuclear missile

Nuclear weapons delivery is the technology and systems used to place a nuclear weapon at the position of detonation, on or near its target. All nine nuclear states have developed some form of medium- to long-range delivery system for their nuc ...

s.

Several navies have launched torpedo strikes since World War II, including:

* During the Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 ŌĆō 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, the United States Navy successfully attacked a dam with air-launched torpedoes.

* Israeli Navy fast attack craft crippled the American electronic intelligence vessel USS ''Liberty'' with gunfire and torpedoes during the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War, also known as the June War, 1967 ArabŌĆōIsraeli War or Third ArabŌĆōIsraeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states, primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, Syria, and Jordan from 5 to 10June ...

, resulting in the loss of 34 crew.

* A Pakistan Navy

The Pakistan Navy (PN) (; ''romanized'': P─ükist─ün Bahr├Ł'a; ) is the naval warfare branch of the Pakistan Armed Forces. The Chief of the Naval Staff, a four-star admiral, commands the navy and is a member of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Com ...

sank the Indian frigate on 9 December 1971 during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, with the loss of over 18 officers and 176 sailors.

* The British Royal Navy nuclear attack submarine sank the Argentine Navy

The Argentine Navy (ARA; ). This forms the basis for the navy's ship prefix "ARA". is the navy of Argentina. It is one of the three branches of the Armed Forces of the Argentine Republic, together with the Argentine Army, Army and the Argentine ...

light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

on 2 May 1982 with two Mark 8

Mark 8 is the eighth chapter of the Gospel of Mark in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It contains two miracles of Jesus, Peter's confession that he believes Jesus is the Messiah, and Jesus' first prediction of his own death and resurr ...

torpedoes during the Falklands War

The Falklands War () was a ten-week undeclared war between Argentina and the United Kingdom in 1982 over two British Overseas Territories, British dependent territories in the South Atlantic: the Falkland Islands and Falkland Islands Dependenci ...

with the loss of 323 lives.

* On 16 June 1982, during the Lebanon War, an unnamed Israeli submarine torpedoed and sank the Lebanese coaster ''Transit'',Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

, in the belief that the vessel was evacuating anti-Israeli militias. The ship was hit by two torpedoes, managed to run aground but eventually sank. There were 25 dead, including her captain. The Israeli Navy

The Israeli Navy (, ''ßĖżeil HaYam HaYisraeli'', ; ) is the Israel Defense Forces#Arms, naval warfare service arm of the Israel Defense Forces, operating primarily in the Mediterranean Sea theater as well as the Gulf of Eilat and the Red Sea th ...

disclosed the incident in November 2018.Croatian Navy

The Croatian Navy (HRM; ) is the naval force branch of the Croatian Armed Forces. It was formed in 1991 from what Croatian forces managed to capture from the Yugoslav Navy during the breakup of Yugoslavia and Croatian War of Independence. In ad ...

disabled the Yugoslav patrol boat P─ī-176 ''Mukos'' with a torpedo launched by Croatian naval commandos from an improvised device during the Battle of the Dalmatian channels

The Battle of the Dalmatian Channels was a three-day confrontation between three tactical groups of Yugoslav Navy ships and coastal artillery, and a detachment of naval commandos of the Croatian Navy fought on 14ŌĆō16 November 1991 during the C ...

on 14 November 1991, in the course of the Croatian War of Independence

The Croatian War of Independence) and (rarely) "War in Krajina" ( sr-Cyrl-Latn, ąĀą░čé čā ąÜčĆą░čśąĖąĮąĖ, Rat u Krajini) are used. was an armed conflict fought in Croatia from 1991 to 1995 between Croats, Croat forces loyal to the Governmen ...