A tokamak (; ) is a device which uses a powerful

magnetic field

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular ...

generated by external magnets to confine

plasma in the shape of an axially symmetrical

torus

In geometry, a torus (: tori or toruses) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space one full revolution about an axis that is coplanarity, coplanar with the circle. The main types of toruses inclu ...

. The tokamak is one of several types of

magnetic confinement

Magnetic confinement fusion (MCF) is an approach to generate thermonuclear fusion power that uses magnetic fields to confine fusion fuel in the form of a plasma. Magnetic confinement is one of two major branches of controlled fusion research, alo ...

devices being developed to produce controlled

thermonuclear

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the release or absorption of ener ...

fusion power

Fusion power is a proposed form of power generation that would generate electricity by using heat from nuclear fusion reactions. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, while releasing energy. Devices d ...

. The tokamak concept is currently one of the leading candidates for a practical

fusion reactor

Fusion power is a proposed form of power generation that would generate electricity by using heat from nuclear fusion reactions. In a fusion process, two lighter atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus, while releasing energy. Devices ...

for providing minimally polluting electrical power.

The proposal to use controlled thermonuclear fusion for industrial purposes and a specific scheme using thermal insulation of high-temperature plasma by an electric field was first formulated by the Soviet physicist

Oleg Lavrentiev in a mid-1950 paper. In 1951,

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov (; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet Physics, physicist and a List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, which he was awarded in 1975 for emphasizing human rights around the world.

Alt ...

and

Igor Tamm

Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm (; 8 July 1895 – 12 April 1971) was a Soviet Union, Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov and Ilya Mikhailovich Frank, for their 1934 discovery and demon ...

modified the scheme by proposing a theoretical basis for a thermonuclear reactor, where the plasma would have the shape of a torus and be held by a magnetic field.

The first tokamak was built in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

1954. In 1968 the electronic plasma temperature of 1 keV was reached on the tokamak T-3, built at the

Kurchatov Institute

The Kurchatov Institute (, National Research Centre "Kurchatov Institute") is Russia's leading research and development institution in the field of nuclear power, nuclear energy. It is named after Igor Kurchatov and is located at 1 Kurchatov Sq ...

under the leadership of academician L. A. Artsimovich.

A second set of results was published in 1968, this time claiming performance far in advance of any other machine. When these were also met skeptically, the Soviets invited British scientists from the laboratory in

Culham Centre for Fusion Energy

The Culham Centre for Fusion Energy (CCFE) is the UK's national laboratory for fusion research. It is located at the Culham Science Centre, near Culham, Oxfordshire, and is the site of the Mega Ampere Spherical Tokamak (MAST) and the now closed ...

(Nicol Peacock et al.) to the USSR with their equipment. Measurements on the T-3 confirmed the results, spurring a worldwide stampede of tokamak construction. It had been demonstrated that a

stable plasma equilibrium requires

magnetic field line

A magnetic field (sometimes called B-field) is a physical field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular ...

s that wind around the torus in a

helix

A helix (; ) is a shape like a cylindrical coil spring or the thread of a machine screw. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is for ...

. Devices like the

z-pinch

In fusion power research, the Z-pinch (zeta pinch) is a type of plasma confinement system that uses an electric current in the plasma to generate a magnetic field that compresses it (see pinch). These systems were originally referred to simpl ...

and

stellarator

A stellarator confines Plasma (physics), plasma using external magnets. Scientists aim to use stellarators to generate fusion power. It is one of many types of magnetic confinement fusion devices. The name "stellarator" refers to stars because ...

had attempted this, but demonstrated serious instabilities. It was the development of the concept now known as the

safety factor

In engineering, a factor of safety (FoS) or safety factor (SF) expresses how much stronger a system is than it needs to be for its specified maximum load. Safety factors are often calculated using detailed analysis because comprehensive testing i ...

(labelled ''q'' in mathematical notation) that guided tokamak development; by arranging the reactor so this critical safety factor was always greater than 1, the tokamaks strongly suppressed the instabilities which plagued earlier designs.

By the mid-1960s, the tokamak designs began to show greatly improved performance. The initial results were released in 1965, but were ignored;

Lyman Spitzer

Lyman Spitzer Jr. (June 26, 1914 – March 31, 1997) was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. As a scientist, he carried out research into star formation and plasma physics and in 1946 conceived the idea of telesco ...

dismissed them out of hand after noting potential problems in their system for measuring temperatures.

The Australian National University built and operated the first tokamak outside the Soviet Union in the 1960s.

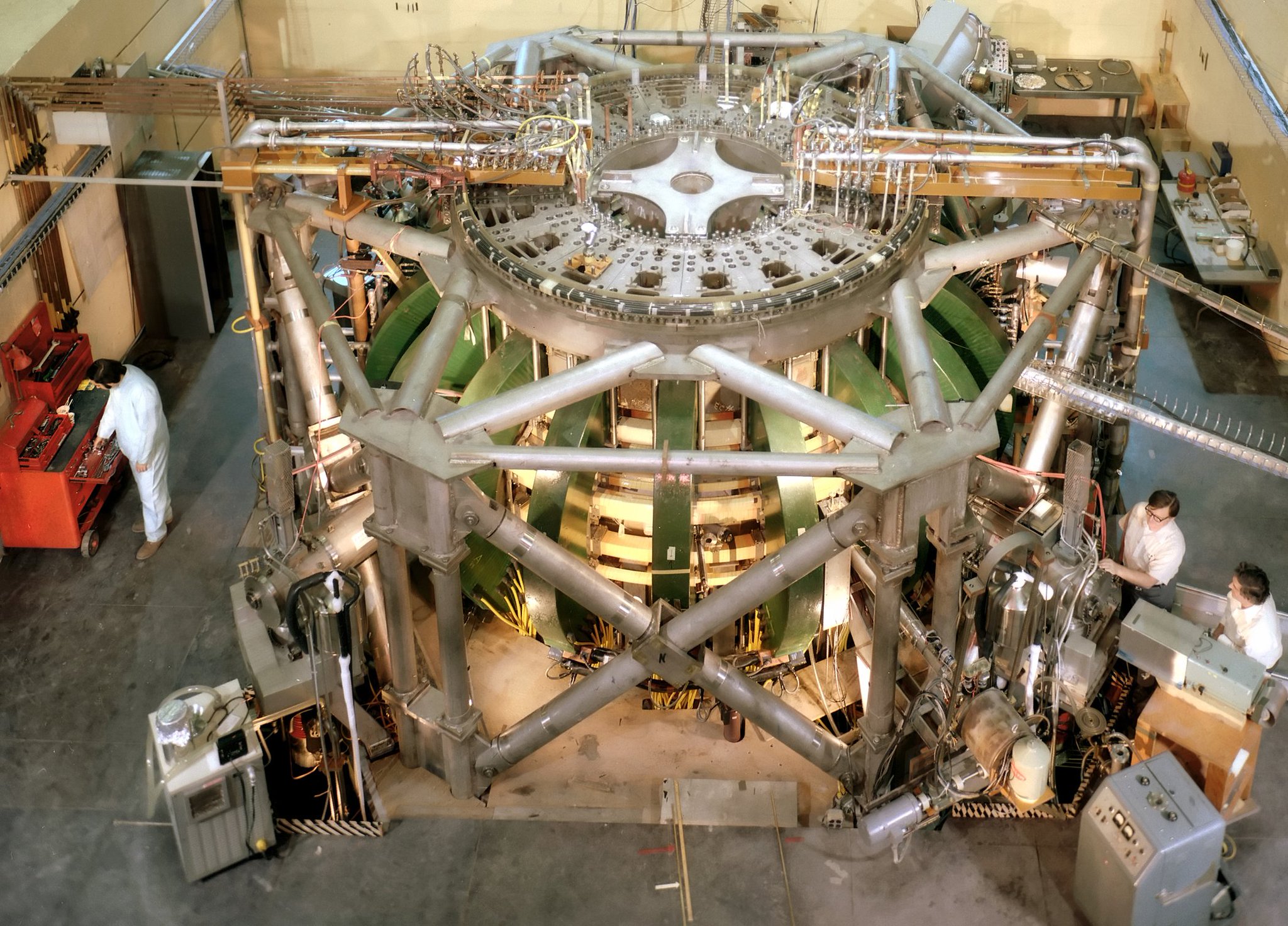

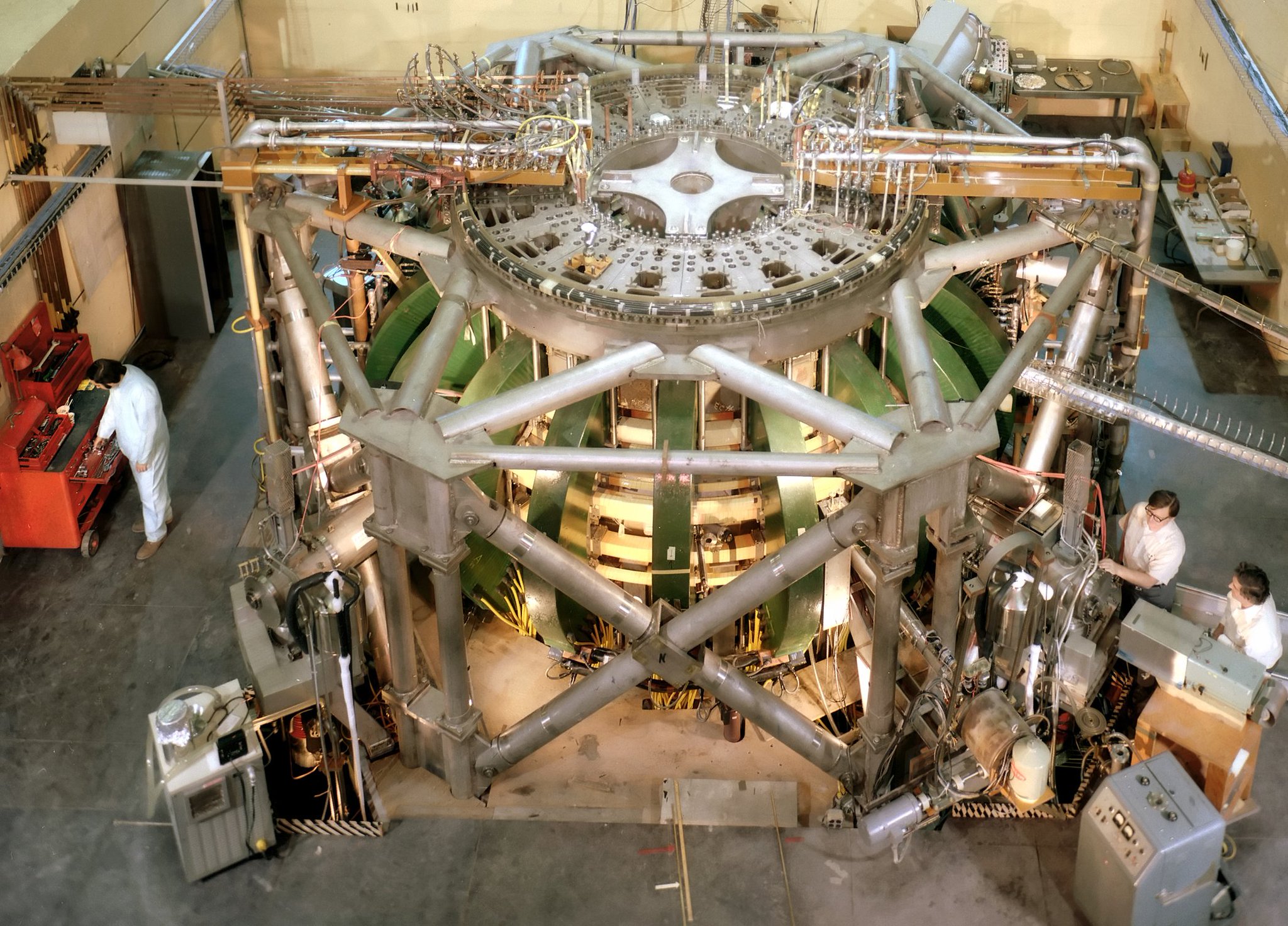

The

Princeton Large Torus

The Princeton Large Torus (or PLT), was an early tokamak built at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). It was one of the first large scale tokamak machines and among the most powerful in terms of current and magnetic fields. Originally ...

(or PLT), was built at the

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory for plasma physics and nuclear fusion science. Its primary mission is research into and development of fusion as an energy source. It is know ...

(PPPL). It was declared operational in December 1975.

It was one of the first large scale tokamak machines and among the most powerful in terms of current and magnetic fields.

It achieved a record for the peak ion temperature, eventually reaching 75 million K, well beyond the minimum needed for a practical fusion device.

By the mid-1970s, dozens of tokamaks were in use around the world. By the late 1970s, these machines had reached all of the conditions needed for practical

fusion, although not at the same time nor in a single

reactor. With the goal of breakeven (a

fusion energy gain factor

A fusion energy gain factor, usually expressed with the symbol ''Q'', is the ratio of fusion power produced in a nuclear fusion reactor to the power required to maintain the plasma in steady state. The condition of ''Q'' = 1, when the ...

equal to 1) now in sight, a new series of machines were designed that would run on a fusion fuel of

deuterium

Deuterium (hydrogen-2, symbol H or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen; the other is protium, or hydrogen-1, H. The deuterium nucleus (deuteron) contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more c ...

and

tritium

Tritium () or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of ~12.33 years. The tritium nucleus (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of the ...

.

The

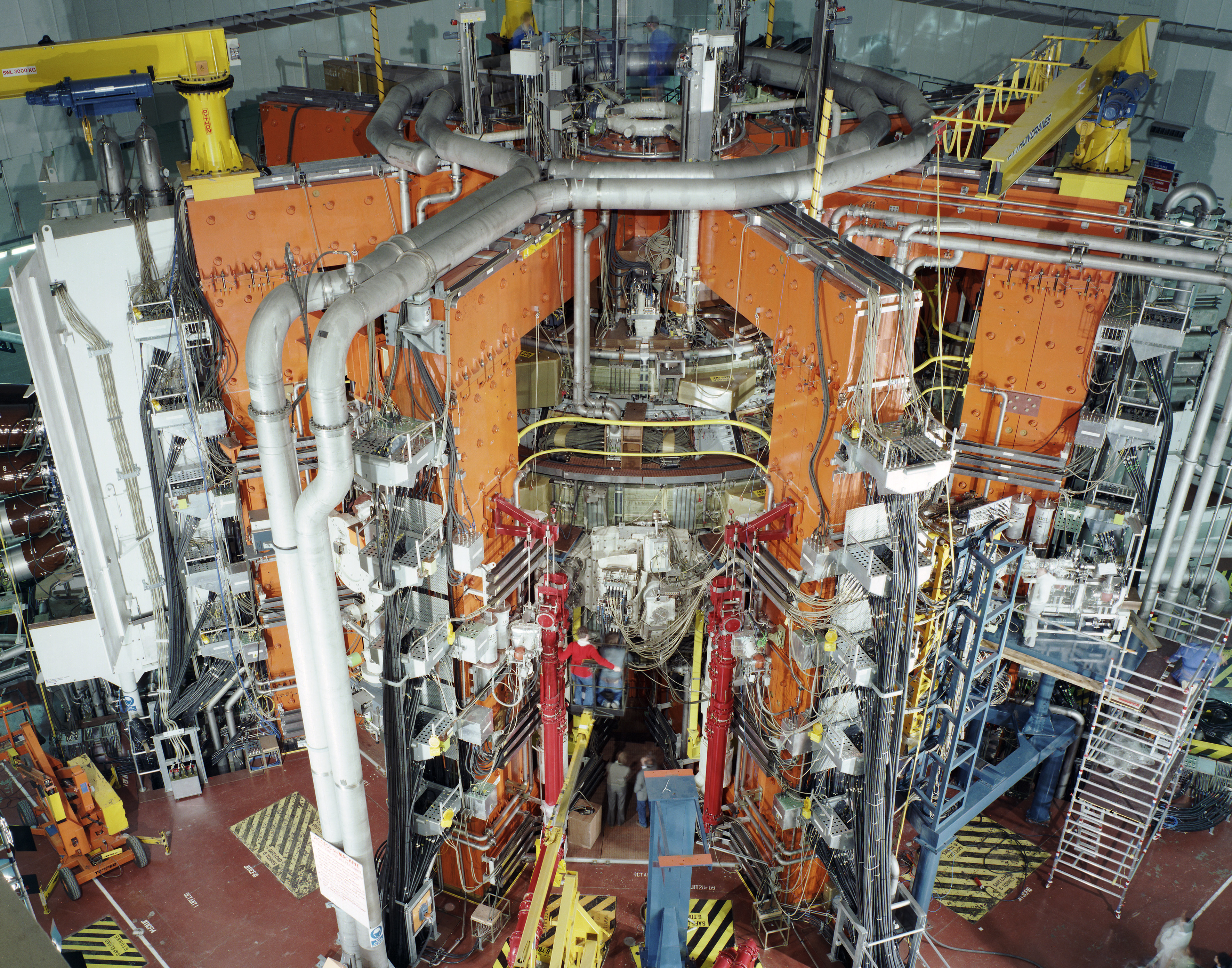

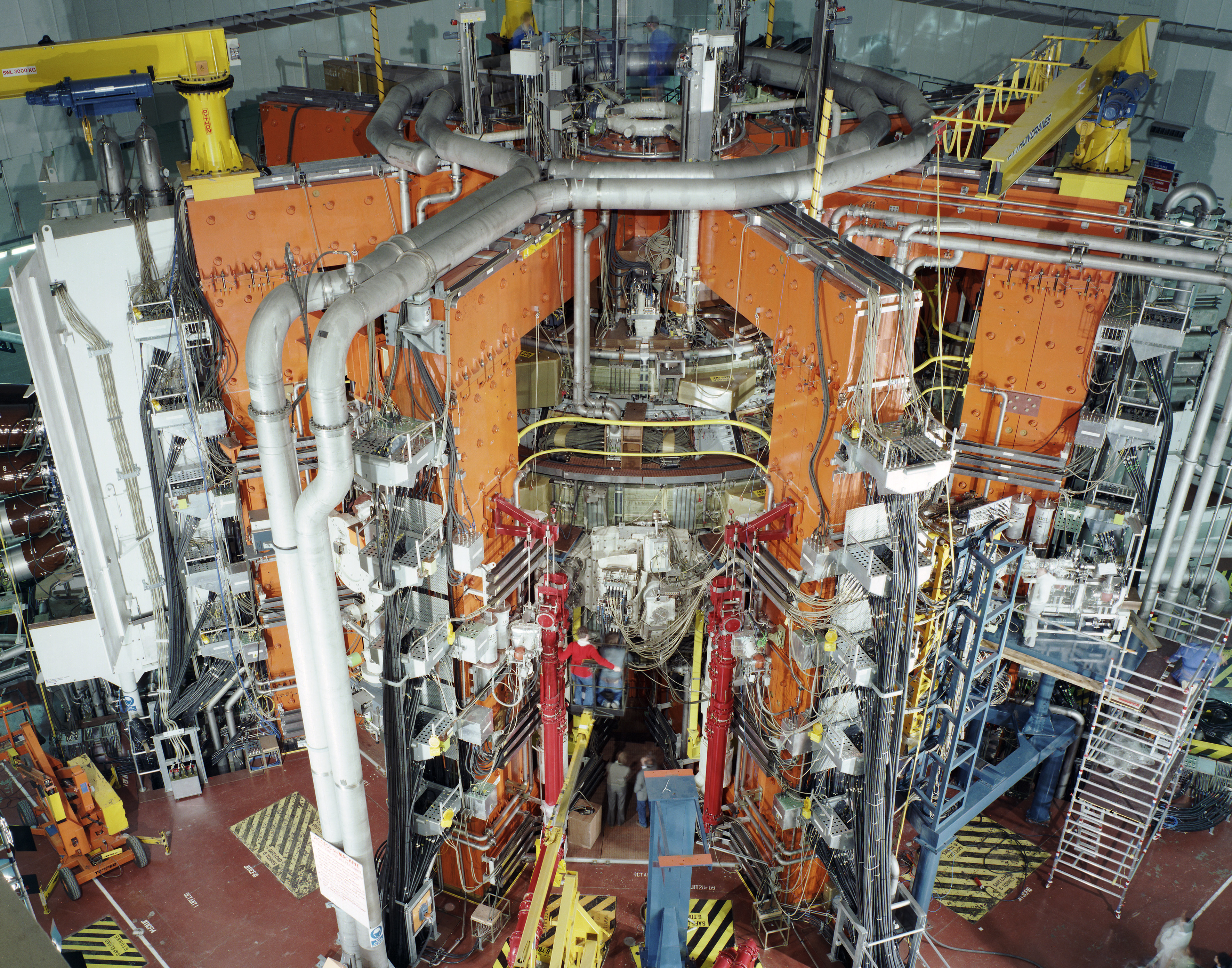

Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor

The Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor (TFTR) was an experimental tokamak built at Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) circa 1980 and entering service in 1982. TFTR was designed with the explicit goal of reaching scientific breakeven, the point w ...

(TFTR),

and the

Joint European Torus

The Joint European Torus (JET) was a magnetically confined plasma physics experiment, located at Culham Centre for Fusion Energy in Oxfordshire, UK. Based on a tokamak design, the fusion research facility was a joint European project with the ...

(JET)

performed extensive experiments studying and prefecting plasma discharges with high energy confinement and high fusion rates.

TFTR discovered new modes of plasma discharges called supershots and enhanced reverse shear discharges. Jet prefected the

High-confinement mode

In plasma physics and magnetic confinement fusion, the high-confinement mode (H-mode) is a phenomenon observed in toroidal fusion plasmas such as tokamaks. In general, plasma energy confinement degrades as the applied heating power is increased. Ab ...

H-mode.

Both performed extensive experimebta campaigns with deuterium and tritium plasmas. they were the only tokamaks to do so. TFTR created 1.6 GJ of fusion energy during the three year campaign.

The peak fusion power in one discharge was 10.3 MW. The peak in JET was 16 MW.

They achieved calculated values for the ratio of fusion power to applied heating power in the plasma center,

Q

of approximately 1.3 in JET and 0.8 in TFTR (discharge 80539).

The achieved values of this ratio averaged over the entire plasmas, Q were 0.63 and 0.28 (discharge 80539) respectively.

, a JET discharge remains the record holder for fusion output, with 69 MJ of energy output over a 5-second period.

Both TFTR and JET resulted in extensive studies of properties of the alpha particles resulting from the deuterium-tritium fusion reactions. The alpha particle heating of the plasma is necessary for sustaining burning conditions.

These machines demonstrated new problems that limited their performance. Solving these would require a much larger and more expensive machine, beyond the abilities of any one country. After an initial agreement between

Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

and

Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

in November 1985, the

International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor

ITER (initially the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, ''iter'' meaning "the way" or "the path" in Latin) is an international nuclear fusion research and engineering megaproject aimed at creating energy through a fusion process s ...

(ITER) effort emerged and remains the primary international effort to develop practical fusion power. Many smaller designs, and offshoots like the

spherical tokamak

A spherical tokamak is a type of fusion power device based on the tokamak principle. It is notable for its very narrow profile, or ''aspect ratio''. A traditional tokamak has a toroidal confinement area that gives it an overall shape similar to ...

, continue to be used to investigate performance parameters and other issues.

Etymology

The word ''tokamak'' is a

transliteration

Transliteration is a type of conversion of a text from one script to another that involves swapping letters (thus '' trans-'' + '' liter-'') in predictable ways, such as Greek → and → the digraph , Cyrillic → , Armenian → or L ...

of the

Russian

Russian(s) may refer to:

*Russians (), an ethnic group of the East Slavic peoples, primarily living in Russia and neighboring countries

*A citizen of Russia

*Russian language, the most widely spoken of the Slavic languages

*''The Russians'', a b ...

word , an acronym of either:

or:

The term "tokamak" was coined in 1957 by

Igor Golovin, a student of academician

Igor Kurchatov

Igor Vasilyevich Kurchatov (; 12 January 1903 – 7 February 1960), was a Soviet physicist who played a central role in organizing and directing the former Soviet program of nuclear weapons, and has been referred to as "father of the Russian ...

. It originally sounded like "tokamag" ("токамаг") — an acronym of the words "''to''roidal ''cha''mber

magnetic

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that occur through a magnetic field, which allows objects to attract or repel each other. Because both electric currents and magnetic moments of elementary particles give rise to a magnetic field, m ...

" ("''то''роидальная ''ка''мера ''маг''нитная"), but

Natan Yavlinsky

Natan Aronovich Yavlinsky (; 13 February 191228 July 1962) was a Russian physicist in the former Soviet Union who invented and developed the first working tokamak.

Early life and career

Yavlinsky was born to a family of doctors on 13 February ...

, the author of the first toroidal system, proposed replacing "-mag" with "-mak" for euphony. Later, this name was borrowed by many languages.

History

First steps

In 1934,

Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

,

Paul Harteck

Paul Karl Maria Harteck (20 July 190222 January 1985) was an Austrian physical chemist. In 1945 under Operation Epsilon in "the big sweep" throughout Germany, Harteck was arrested by the allied British and American Armed Forces for suspicion of ...

and

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

were the first to achieve fusion on Earth, using a

particle accelerator

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel electric charge, charged particles to very high speeds and energies to contain them in well-defined particle beam, beams. Small accelerators are used for fundamental ...

to shoot

deuterium

Deuterium (hydrogen-2, symbol H or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen; the other is protium, or hydrogen-1, H. The deuterium nucleus (deuteron) contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more c ...

nuclei into metal foil containing deuterium or other atoms. This allowed them to measure the

nuclear cross section

The nuclear cross section of a nucleus is used to describe the probability that a nuclear reaction will occur. The concept of a nuclear cross section can be quantified physically in terms of "characteristic area" where a larger area means a larg ...

of various fusion reactions, and determined that the deuterium–deuterium reaction occurred at a lower energy than other reactions, peaking at about 100,000

electronvolt

In physics, an electronvolt (symbol eV), also written electron-volt and electron volt, is the measure of an amount of kinetic energy gained by a single electron accelerating through an Voltage, electric potential difference of one volt in vacuum ...

s (100 keV).

Accelerator-based fusion is not practical because the reactor

cross section

Cross section may refer to:

* Cross section (geometry)

** Cross-sectional views in architecture and engineering 3D

*Cross section (geology)

* Cross section (electronics)

* Radar cross section, measure of detectability

* Cross section (physics)

**A ...

is tiny; most of the particles in the accelerator will scatter off the fuel, not fuse with it. These scatterings cause the particles to lose energy to the point where they can no longer undergo fusion. The energy put into these particles is thus lost, and it is easy to demonstrate this is much more energy than the resulting fusion reactions can release.

To maintain fusion and produce net energy output, the bulk of the fuel must be raised to high temperatures so its atoms are constantly colliding at high speed; this gives rise to the name ''

thermonuclear

Nuclear fusion is a reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the release or absorption of ener ...

'' due to the high temperatures needed to bring it about. In 1944,

Enrico Fermi

Enrico Fermi (; 29 September 1901 – 28 November 1954) was an Italian and naturalized American physicist, renowned for being the creator of the world's first artificial nuclear reactor, the Chicago Pile-1, and a member of the Manhattan Project ...

calculated the reaction would be self-sustaining at about 50,000,000 K; at that temperature, the rate that energy is given off by the reactions is high enough that they heat the surrounding fuel rapidly enough to maintain the temperature against losses to the environment, continuing the reaction.

During the

Manhattan Project

The Manhattan Project was a research and development program undertaken during World War II to produce the first nuclear weapons. It was led by the United States in collaboration with the United Kingdom and Canada.

From 1942 to 1946, the ...

, the first practical way to reach these temperatures was created, using an

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

. In 1944, Fermi gave a talk on the physics of fusion in the context of a then-hypothetical

hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H-bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lo ...

. However, some thought had already been given to a ''controlled'' fusion device, and

James L. Tuck

James Leslie Tuck (9 January 1910 – 15 December 1980) was a British physicist, working on the applications of explosives as part of the British delegation to the Manhattan Project.

Tuck was born in Manchester, England, and educated at the Vic ...

and

Stanislaw Ulam Stanislav and variants may refer to:

People

*Stanislav (given name), a Slavic given name with many spelling variations (Stanislaus, Stanislas, Stanisław, etc.)

Places

* Stanislav, Kherson Oblast, a coastal village in Ukraine

* Stanislaus County, ...

had attempted such using

shaped charge

A shaped charge, commonly also hollow charge if shaped with a cavity, is an explosive charge shaped to focus the effect of the explosive's energy. Different types of shaped charges are used for various purposes such as cutting and forming metal, ...

s driving a metal foil infused with deuterium, although without success.

The first attempts to build a practical fusion machine took place in the

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, where

George Paget Thomson

Sir George Paget Thomson (; 3 May 1892 – 10 September 1975) was an English physicist who shared the 1937 Nobel Prize in Physics with Clinton Davisson “for their experimental discovery of the diffraction of electrons by crystals”.

Educa ...

had selected the

pinch effect

A pinch (or: Bennett pinch (after Willard Harrison Bennett), electromagnetic pinch, magnetic pinch, pinch effect, or plasma pinch.) is the compression of an electrically conducting Electrical filament, filament by magnetic forces, or a device tha ...

as a promising technique in 1945. After several failed attempts to gain funding, he gave up and asked two graduate students, Stanley (Stan) W. Cousins and Alan Alfred Ware (1924–2010), to build a device out of surplus

radar

Radar is a system that uses radio waves to determine the distance ('' ranging''), direction ( azimuth and elevation angles), and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It is a radiodetermination method used to detect and track ...

equipment. This was successfully operated in 1948, but showed no clear evidence of fusion and failed to gain the interest of the

Atomic Energy Research Establishment

The Atomic Energy Research Establishment (AERE), also known as Harwell Laboratory, was the main Headquarters, centre for nuclear power, atomic energy research and development in the United Kingdom from 1946 to the 1990s. It was created, owned ...

.

Lavrentiev's letter

In 1950,

Oleg Lavrentiev, then a

Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Republic and, from 1922, the Soviet Union. The army was established in January 1918 by a decree of the Council of People ...

sergeant stationed on

Sakhalin

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, p=səxɐˈlʲin) is an island in Northeast Asia. Its north coast lies off the southeastern coast of Khabarovsk Krai in Russia, while its southern tip lies north of the Japanese island of Hokkaido. An islan ...

, wrote a letter to the

Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union

The Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union was the Central committee, highest organ of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) between Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Congresses. Elected by the ...

. The letter outlined the idea of using an

atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission or atomic bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear weapon), producing a nuclear expl ...

to ignite a fusion fuel, and then went on to describe a system that used

electrostatic

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies slow-moving or stationary electric charges.

Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word (), mean ...

fields to contain a hot plasma in a steady state for energy production.

The letter was sent to

Andrei Sakharov

Andrei Dmitrievich Sakharov (; 21 May 192114 December 1989) was a Soviet Physics, physicist and a List of Nobel Peace Prize laureates, Nobel Peace Prize laureate, which he was awarded in 1975 for emphasizing human rights around the world.

Alt ...

for comment. Sakharov noted that "the author formulates a very important and not necessarily hopeless problem", and found his main concern in the arrangement was that the plasma would hit the electrode wires, and that "wide meshes and a thin current-carrying part which will have to reflect almost all incident nuclei back into the reactor. In all likelihood, this requirement is incompatible with the mechanical strength of the device."

Some indication of the importance given to Lavrentiev's letter can be seen in the speed with which it was processed; the letter was received by the Central Committee on 29 July, Sakharov sent his review in on 18 August, by October, Sakharov and

Igor Tamm

Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm (; 8 July 1895 – 12 April 1971) was a Soviet Union, Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov and Ilya Mikhailovich Frank, for their 1934 discovery and demon ...

had completed the first detailed study of a fusion reactor, and they had asked for funding to build it in January 1951.

Magnetic confinement

When heated to fusion temperatures, the

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

s in atoms dissociate, resulting in a fluid of nuclei and electrons known as

plasma. Unlike electrically neutral atoms, a plasma is electrically conductive, and can, therefore, be manipulated by electrical or magnetic fields.

Sakharov's concern about the electrodes led him to consider using magnetic confinement instead of electrostatic. In the case of a magnetic field, the particles will circle around the

lines of force

In the history of physics, a line of force in Michael Faraday's extended sense is synonymous with James Clerk Maxwell's line of induction. According to J.J. Thomson, Faraday usually discusses ''lines of force'' as chains of polarized particles in ...

. As the particles are moving at high speed, their resulting paths look like a helix. If one arranges a magnetic field so lines of force are parallel and close together, the particles orbiting adjacent lines may collide, and fuse.

Such a field can be created in a

solenoid

upright=1.20, An illustration of a solenoid

upright=1.20, Magnetic field created by a seven-loop solenoid (cross-sectional view) described using field lines

A solenoid () is a type of electromagnet formed by a helix, helical coil of wire whos ...

, a cylinder with magnets wrapped around the outside. The combined fields of the magnets create a set of parallel magnetic lines running down the length of the cylinder. This arrangement prevents the particles from moving sideways to the wall of the cylinder, but it does not prevent them from running out the end. The obvious solution to this problem is to bend the cylinder around into a donut shape, or torus, so that the lines form a series of continual rings. In this arrangement, the particles circle endlessly.

Sakharov discussed the concept with

Igor Tamm

Igor Yevgenyevich Tamm (; 8 July 1895 – 12 April 1971) was a Soviet Union, Soviet physicist who received the 1958 Nobel Prize in Physics, jointly with Pavel Alekseyevich Cherenkov and Ilya Mikhailovich Frank, for their 1934 discovery and demon ...

, and by the end of October 1950 the two had written a proposal and sent it to

Igor Kurchatov

Igor Vasilyevich Kurchatov (; 12 January 1903 – 7 February 1960), was a Soviet physicist who played a central role in organizing and directing the former Soviet program of nuclear weapons, and has been referred to as "father of the Russian ...

, the director of the atomic bomb project within the USSR, and his deputy,

Igor Golovin. However, this initial proposal ignored a fundamental problem; when arranged along a straight solenoid, the external magnets are evenly spaced, but when bent around into a torus, they are closer together on the inside of the ring than the outside. This leads to uneven forces that cause the particles to drift away from their magnetic lines.

During visits to the

Laboratory of Measuring Instruments of the USSR Academy of Sciences (LIPAN), the Soviet

nuclear research

Nuclear physics is the field of physics that studies atomic nuclei and their constituents and interactions, in addition to the study of other forms of nuclear matter.

Nuclear physics should not be confused with atomic physics, which studies the ...

centre, Sakharov suggested two possible solutions to this problem. One was to suspend a current-carrying ring in the centre of the torus. The current in the ring would produce a magnetic field that would mix with the one from the magnets on the outside. The resulting field would be twisted into a helix, so that any given particle would find itself repeatedly on the outside, then inside, of the torus. The drifts caused by the uneven fields are in opposite directions on the inside and outside, so over the course of multiple

orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an ...

s around the long axis of the

torus

In geometry, a torus (: tori or toruses) is a surface of revolution generated by revolving a circle in three-dimensional space one full revolution about an axis that is coplanarity, coplanar with the circle. The main types of toruses inclu ...

, the opposite drifts would cancel out. Alternately, he suggested using an external magnet to induce a current in the

plasma itself, instead of a separate metal ring, which would have the same effect.

In January 1951, Kurchatov arranged a meeting at LIPAN to consider Sakharov's concepts. They found widespread interest and support, and in February a report on the topic was forwarded to

Lavrentiy Beria

Lavrentiy Pavlovich Beria ka, ლავრენტი პავლეს ძე ბერია} ''Lavrenti Pavles dze Beria'' ( – 23 December 1953) was a Soviet politician and one of the longest-serving and most influential of Joseph ...

, who oversaw the atomic efforts in the USSR. For a time, nothing was heard back.

Richter and the birth of fusion research

On 25 March 1951, Argentine President

Juan Perón

Juan Domingo Perón (, , ; 8 October 1895 – 1 July 1974) was an Argentine military officer and Statesman (politician), statesman who served as the History of Argentina (1946-1955), 29th president of Argentina from 1946 to Revolución Libertad ...

announced that a former German scientist,

Ronald Richter

Ronald Richter (1909–1991) was an Austrian-born German, later Argentine citizen, scientist who became infamous in connection with the Argentine Huemul Project and the National Atomic Energy Commission (CNEA). The project was intended to gener ...

, had succeeded in producing fusion at a laboratory scale as part of what is now known as the

Huemul Project. Scientists around the world were excited by the announcement, but soon concluded it was not true; simple calculations showed that his experimental setup could not produce enough energy to heat the fusion fuel to the needed temperatures.

Although dismissed by nuclear researchers, the widespread news coverage meant politicians were suddenly aware of, and receptive to, fusion research. In the UK, Thomson was suddenly granted considerable funding. Over the next months, two projects based on the pinch system were up and running. In the US,

Lyman Spitzer

Lyman Spitzer Jr. (June 26, 1914 – March 31, 1997) was an American theoretical physicist, astronomer and mountaineer. As a scientist, he carried out research into star formation and plasma physics and in 1946 conceived the idea of telesco ...

read the Huemul story, realized it was false, and set about designing a machine that would work. In May he was awarded $50,000 to begin research on his

stellarator

A stellarator confines Plasma (physics), plasma using external magnets. Scientists aim to use stellarators to generate fusion power. It is one of many types of magnetic confinement fusion devices. The name "stellarator" refers to stars because ...

concept. Jim Tuck had returned to the UK briefly and saw Thomson's pinch machines. When he returned to Los Alamos he also received $50,000 directly from the Los Alamos budget.

Similar events occurred in the

USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

. In mid-April, Dmitri Efremov of the Scientific Research Institute of Electrophysical Apparatus stormed into Kurchatov's study with a magazine containing a story about Richter's work, demanding to know why they were beaten by the Argentines.

Kurchatov immediately contacted Beria with a proposal to set up a separate fusion research laboratory with

Lev Artsimovich

Lev Andreyevich Artsimovich ( Russian: Лев Андреевич Арцимович, February 25, 1909 – March 1, 1973), also transliterated Arzimowitsch, was a Soviet physicist known for his contributions to the Tokamak— a device that produ ...

as director. Only days later, on 5 May, the proposal had been signed by

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Dzhugashvili; 5 March 1953) was a Soviet politician and revolutionary who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until Death and state funeral of Joseph Stalin, his death in 1953. He held power as General Secret ...

.

New ideas

By October, Sakharov and Tamm had completed a much more detailed consideration of their original proposal, calling for a device with a major radius (of the torus as a whole) of and a minor radius (the interior of the cylinder) of . The proposal suggested the system could produce of

tritium

Tritium () or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of ~12.33 years. The tritium nucleus (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of the ...

a day, or breed of U233 a day.

As the idea was further developed, it was realized that a current in the plasma could create a field that was strong enough to confine the plasma as well, removing the need for the external coils. At this point, the Soviet researchers had re-invented the pinch system being developed in the UK, although they had come to this design from a very different starting point.

Once the idea of using the pinch effect for confinement had been proposed, a much simpler solution became evident. Instead of a large toroid, one could simply induce the current into a linear tube, which could cause the plasma within to collapse down into a filament. This had a huge advantage; the current in the plasma would heat it through normal

resistive heating

Joule heating (also known as resistive heating, resistance heating, or Ohmic heating) is the process by which the passage of an electric current through a conductor produces heat.

Joule's first law (also just Joule's law), also known in countr ...

, but this would not heat the plasma to fusion temperatures. However, as the plasma collapsed, the

adiabatic process

An adiabatic process (''adiabatic'' ) is a type of thermodynamic process that occurs without transferring heat between the thermodynamic system and its Environment (systems), environment. Unlike an isothermal process, an adiabatic process transf ...

would result in the temperature rising dramatically, more than enough for fusion. With this development, only Golovin and

Natan Yavlinsky

Natan Aronovich Yavlinsky (; 13 February 191228 July 1962) was a Russian physicist in the former Soviet Union who invented and developed the first working tokamak.

Early life and career

Yavlinsky was born to a family of doctors on 13 February ...

continued considering the more static toroidal arrangement.

Instability

On 4 July 1952, Nikolai Filippov's group measured

neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

s being released from a linear pinch machine.

Lev Artsimovich

Lev Andreyevich Artsimovich ( Russian: Лев Андреевич Арцимович, February 25, 1909 – March 1, 1973), also transliterated Arzimowitsch, was a Soviet physicist known for his contributions to the Tokamak— a device that produ ...

demanded that they check everything before concluding fusion had occurred, and during these checks, they found that the neutrons were not from fusion at all. This same linear arrangement had also occurred to researchers in the UK and US, and their machines showed the same behaviour. But the great secrecy surrounding the type of research meant that none of the groups were aware that others were also working on it, let alone having the identical problem.

After much study, it was found that some of the released neutrons were produced by instabilities in the plasma. There were two common types of instability, the ''sausage'' that was seen primarily in linear machines, and the ''kink'' which was most common in the toroidal machines.

[ Groups in all three countries began studying the formation of these instabilities and potential ways to address them.]Martin David Kruskal

Martin David Kruskal (; September 28, 1925 – December 26, 2006) was an American mathematician and physicist. He made fundamental contributions in many areas of mathematics and science, ranging from plasma physics to general relativity and ...

and Martin Schwarzschild

Martin Schwarzschild (May 31, 1912 – April 10, 1997) was a German-American astrophysicist. The Schwarzschild criterion, for the stability of stellar gas against convention, is named after him.

Biography

Schwarzschild was born in Potsdam ...

in the US, and Shafranov in the USSR.

One idea that came from these studies became known as the "stabilized pinch". This concept added additional coils to the outside of the chamber, which created a magnetic field that would be present in the plasma before the pinch discharge. In most concepts, the externally induced field was relatively weak, and because a plasma is diamagnetic

Diamagnetism is the property of materials that are repelled by a magnetic field; an applied magnetic field creates an induced magnetic field in them in the opposite direction, causing a repulsive force. In contrast, paramagnetic and ferromagn ...

, it penetrated only the outer areas of the plasma.[ When the pinch discharge occurred and the plasma quickly contracted, this field became "frozen in" to the resulting filament, creating a strong field in its outer layers. In the US, this was known as "giving the plasma a backbone".

Sakharov revisited his original toroidal concepts and came to a slightly different conclusion about how to stabilize the plasma. The layout would be the same as the stabilized pinch concept, but the role of the two fields would be reversed. Instead of weak externally induced magnetic fields providing stabilization and a strong pinch current responsible for confinement, in the new layout, the external field would be much more powerful in order to provide the majority of confinement, while the current would be much smaller and responsible for the stabilizing effect.

]

Steps toward declassification

In 1955, with the linear approaches still subject to instability, the first toroidal device was built in the USSR. TMP was a classic pinch machine, similar to models in the UK and US of the same era. The vacuum chamber was made of ceramic, and the spectra of the discharges showed silica, meaning the plasma was not perfectly confined by magnetic field and hitting the walls of the chamber. Two smaller machines followed, using copper shells.

In 1955, with the linear approaches still subject to instability, the first toroidal device was built in the USSR. TMP was a classic pinch machine, similar to models in the UK and US of the same era. The vacuum chamber was made of ceramic, and the spectra of the discharges showed silica, meaning the plasma was not perfectly confined by magnetic field and hitting the walls of the chamber. Two smaller machines followed, using copper shells.Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and the Premier of the Soviet Union, Chai ...

and Nikolai Bulganin

Nikolai Alexandrovich Bulganin (; – 24 February 1975) was the Premier of the Soviet Union from 1955 to 1958. He also served as Minister of Defense (Soviet Union), Minister of Defense, following service in the Red Army during World War II.

...

. He offered to give a talk at Atomic Energy Research Establishment, at the former RAF Harwell

Royal Air Force Harwell or more simply RAF Harwell is a former Royal Air Force station, near the village of Harwell, located south east of Wantage, Oxfordshire and north west of Reading, Berkshire, England.

The site is now the Harwell Sc ...

, where he shocked the hosts by presenting a detailed historical overview of the Soviet fusion efforts. He took time to note, in particular, the neutrons seen in early machines and warned that neutrons did not mean fusion.

Unknown to Kurchatov, the British ZETA

Zeta (, ; uppercase Ζ, lowercase ζ; , , classical or ''zē̂ta''; ''zíta'') is the sixth letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 7. It was derived from the Phoenician alphabet, Phoenician letter zay ...

stabilized pinch machine was being built at the far end of the former runway. ZETA was, by far, the largest and most powerful fusion machine to date. Supported by experiments on earlier designs that had been modified to include stabilization, ZETA intended to produce low levels of fusion reactions. This was apparently a great success, and in January 1958, they announced the fusion had been achieved in ZETA based on the release of neutrons and measurements of the plasma temperature.

Vitaly Shafranov

Vitaly Dmitrievich Shafranov (; December 1, 1929 – June 9, 2014) was a Russian theoretical physicist and Academician who worked with plasma physics and thermonuclear fusion research.

Life

Vitaly Dmitrievich Shafranov was born in the village o ...

and Stanislav Braginskii examined the news reports and attempted to figure out how it worked. One possibility they considered was the use of weak "frozen in" fields, but rejected this, believing the fields would not last long enough. They then concluded ZETA was essentially identical to the devices they had been studying, with strong external fields.

First tokamaks

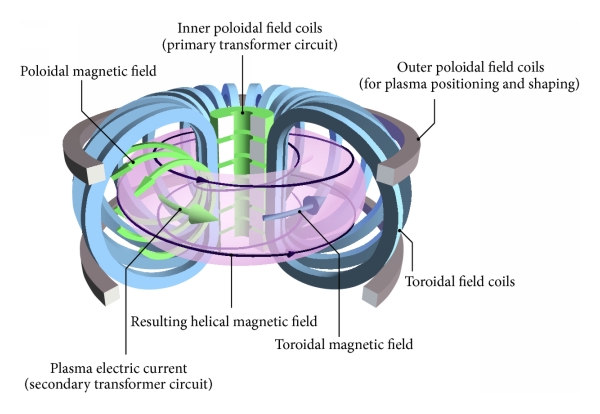

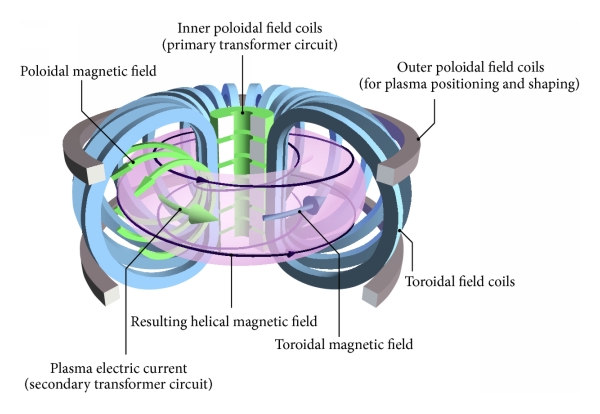

By this time, Soviet researchers had decided to build a larger toroidal machine along the lines suggested by Sakharov. In particular, their design considered one important point found in Kruskal's and Shafranov's works; if the helical path of the particles made them circulate around the plasma's circumference more rapidly than they circulated the long axis of the torus, the kink instability would be strongly suppressed.[

(To be clear, Electrical current in coils wrapping around the torus produces a toroidal magnetic field inside the torus; a pulsed magnetic field through the hole in the torus induces the axial current in the torus which has a poloidal magnetic field surrounding it; there may also be rings of current above and below the torus that create additional poloidal magnetic field. The combined magnetic fields form a helical magnetic structure inside the torus.)

Today this basic concept is known as the '']safety factor

In engineering, a factor of safety (FoS) or safety factor (SF) expresses how much stronger a system is than it needs to be for its specified maximum load. Safety factors are often calculated using detailed analysis because comprehensive testing i ...

''. The ratio of the number of times the particle orbits the major axis compared to the minor axis is denoted ''q'', and the ''Kruskal-Shafranov Limit'' stated that the kink will be suppressed as long as ''q'' > 1. This path is controlled by the relative strengths of the externally induced magnetic field compared to the field created by the internal current. To have ''q'' > 1, the external magnets must be much more powerful, or alternatively, the internal current has to be reduced.[

Following this criterion, design began on a new reactor, T-1, which today is known as the first real tokamak.][ T-1 used both stronger external magnetic fields and a reduced current compared to stabilized pinch machines like ZETA. The success of the T-1 resulted in its recognition as the first working tokamak.]Lenin Prize

The Lenin Prize (, ) was one of the most prestigious awards of the Soviet Union for accomplishments relating to science, literature, arts, architecture, and technology. It was originally created on June 23, 1925, and awarded until 1934. During ...

and the Stalin Prize in 1958. Yavlinskii was already preparing the design of an even larger model, later built as T-3. With the apparently successful ZETA announcement, Yavlinskii's concept was viewed very favourably.

Details of ZETA became public in a series of articles in ''Nature'' later in January. To Shafranov's surprise, the system did use the "frozen in" field concept. He remained sceptical, but a team at the Ioffe Institute

The Ioffe Physical-Technical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (for short, Ioffe Institute, ) is one of Russia's largest research centers specialized in physics and technology. The institute was established in 1918 in Petrograd (now St. ...

in St. Petersberg began plans to build a similar machine known as Alpha. Only a few months later, in May, the ZETA team issued a release stating they had not achieved fusion, and that they had been misled by erroneous measures of the plasma temperature.

T-1 began operation at the end of 1958. It demonstrated very high energy losses through radiation. This was traced to impurities in the plasma due to the vacuum system causing outgassing from the container materials. In order to explore solutions to this problem, another small device was constructed, T-2. This used an internal liner of corrugated metal that was baked at to cook off trapped gasses.

Atoms for Peace and the doldrums

As part of the second Atoms for Peace

"Atoms for Peace" was the title of a speech delivered by U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower to the UN General Assembly in New York City on December 8, 1953.

The United States then launched an "Atoms for Peace" program that supplied equipment ...

meeting in Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

in September 1958, the Soviet delegation released many papers covering their fusion research. Among them was a set of initial results on their toroidal machines, which at that point had shown nothing of note.

The "star" of the show was a large model of Spitzer's stellarator, which immediately caught the attention of the Soviets. In contrast to their designs, the stellarator produced the required twisted paths in the plasma without driving a current through it, using a series of external coils (producing internal magnetic fields) that could operate in the steady state rather than the pulses of the induction system that produced the axial current. Kurchatov began asking Yavlinskii to change their T-3 design to a stellarator, but they convinced him that the current provided a useful second role in heating, something the stellarator lacked.

At the time of the show, the stellarator had suffered a long string of minor problems that were just being solved. Solving these revealed that the diffusion rate of the plasma was much faster than theory predicted. Similar problems were seen in all the contemporary designs, for one reason or another. The stellarator, various pinch concepts and the magnetic mirror

A magnetic mirror, also known as a magnetic trap or sometimes as a pyrotron, is a type of magnetic confinement fusion device used in fusion power to trap high temperature Plasma (physics), plasma using magnetic fields. The mirror was one of the e ...

machines in both the US and USSR all demonstrated problems that limited their confinement times.

From the first studies of controlled fusion, there was a problem lurking in the background. During the Manhattan Project, David Bohm

David Joseph Bohm (; 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American scientist who has been described as one of the most significant Theoretical physics, theoretical physicists of the 20th centuryDavid Peat Who's Afraid of Schrödinger' ...

had been part of the team working on isotopic separation of uranium

Uranium is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Ura ...

. In the post-war era he continued working with plasmas in magnetic fields. Using basic theory, one would expect the plasma to diffuse across the lines of force at a rate inversely proportional to the square of the strength of the field, meaning that small increases in force would greatly improve confinement. But based on their experiments, Bohm developed an empirical formula, now known as Bohm diffusion The diffusion of plasma across a magnetic field was conjectured to follow the Bohm diffusion scaling as indicated from the early plasma experiments of very lossy machines. This predicted that the rate of diffusion was linear with temperature and in ...

, that suggested the rate was linear with the magnetic force, not its square.

If Bohm's formula was correct, there was no hope one could build a fusion reactor based on magnetic confinement. To confine the plasma at the temperatures needed for fusion, the magnetic field would have to be orders of magnitude greater than any known magnet. Spitzer ascribed the difference between the Bohm and classical diffusion rates to turbulence in the plasma, and believed the steady fields of the stellarator would not suffer from this problem. Various experiments at that time suggested the Bohm rate did not apply, and that the classical formula was correct.

But by the early 1960s, with all of the various designs leaking plasma at a prodigious rate, Spitzer himself concluded that the Bohm scaling was an inherent quality of plasmas, and that magnetic confinement would not work. The entire field descended into what became known as "the doldrums", a period of intense pessimism.

Progress in the 1960s

In contrast to the other designs, the experimental tokamaks appeared to be progressing well, so well that a minor theoretical problem was now a real concern. In the presence of gravity, there is a small pressure gradient in the plasma, formerly small enough to ignore but now becoming something that had to be addressed. This led to the addition of yet another set of coils in 1962, which produced a vertical magnetic field that offset these effects. These were a success, and by the mid-1960s the machines began to show signs that they were beating the Bohm limit.

At the 1965 Second International Atomic Energy Agency

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) is an intergovernmental organization that seeks to promote the peaceful use of nuclear technology, nuclear energy and to inhibit its use for any military purpose, including nuclear weapons. It was ...

Conference on fusion at the UK's newly opened Culham Centre for Fusion Energy

The Culham Centre for Fusion Energy (CCFE) is the UK's national laboratory for fusion research. It is located at the Culham Science Centre, near Culham, Oxfordshire, and is the site of the Mega Ampere Spherical Tokamak (MAST) and the now closed ...

, Artsimovich reported that their systems were surpassing the Bohm limit by 10 times. Spitzer, reviewing the presentations, suggested that the Bohm limit may still apply; the results were within the range of experimental error of results seen on the stellarators, and the temperature measurements, based on the magnetic fields, were simply not trustworthy.

The next major international fusion meeting was held in August 1968 in Novosibirsk

Novosibirsk is the largest city and administrative centre of Novosibirsk Oblast and the Siberian Federal District in Russia. As of the 2021 Russian census, 2021 census, it had a population of 1,633,595, making it the most populous city in Siber ...

. By this time two additional tokamak designs had been completed, TM-2 in 1965, and T-4 in 1968. Results from T-3 had continued to improve, and similar results were coming from early tests of the new reactors. At the meeting, the Soviet delegation announced that T-3 was producing electron temperatures of 1000 eV (equivalent to 10 million degrees Celsius) and that confinement time was at least 50 times the Bohm limit.

These results were at least 10 times that of any other machine. If correct, they represented an enormous leap for the fusion community. Spitzer remained skeptical, noting that the temperature measurements were still based on the indirect calculations from the magnetic properties of the plasma. Many concluded they were due to an effect known as runaway electrons

The term runaway electrons (RE) is used to denote electrons that undergo free fall acceleration into the realm of relativistic particles. REs may be classified as thermal (lower energy) or relativistic. The study of runaway electrons is thought to ...

, and that the Soviets were measuring only those extremely energetic electrons and not the bulk temperature. The Soviets countered with several arguments suggesting the temperature they were measuring was Maxwellian, and the debate raged.

Culham Five

In the aftermath of ZETA, the UK teams began the development of new plasma diagnostic tools to provide more accurate measurements. Among these was the use of a laser

A laser is a device that emits light through a process of optical amplification based on the stimulated emission of electromagnetic radiation. The word ''laser'' originated as an acronym for light amplification by stimulated emission of radi ...

to directly measure the temperature of the bulk electrons using Thomson scattering

Thomson scattering is the elastic scattering of electromagnetic radiation by a free charged particle, as described by classical electromagnetism. It is the low-energy limit of Compton scattering: the particle's kinetic energy and photon frequency ...

. This technique was well known and respected in the fusion community; Artsimovich had publicly called it "brilliant". Artsimovich invited Bas Pease, the head of Culham, to use their devices on the Soviet reactors. At the height of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, in what is still considered a major political manoeuvre on Artsimovich's part, British physicists were allowed to visit the Kurchatov Institute, the heart of the Soviet nuclear bomb effort.

The British team, nicknamed "The Culham Five", arrived late in 1968. After a lengthy installation and calibration process, the team measured the temperatures over a period of many experimental runs. Initial results were available by August 1969; the Soviets were correct, their results were accurate. The team phoned the results home to Culham, who then passed them along in a confidential phone call to Washington. The final results were published in ''Nature'' in November 1969.electrical resistance

The electrical resistance of an object is a measure of its opposition to the flow of electric current. Its reciprocal quantity is , measuring the ease with which an electric current passes. Electrical resistance shares some conceptual paral ...

of a plasma was reduced as the temperature increased,

US turmoil

One of the people attending the Novosibirsk meeting in 1968 was Amasa Stone Bishop

Amasa Stone Bishop (1921 – May 21, 1997) was an American Nuclear physics, nuclear physicist specializing in Nuclear fusion, fusion physics. He received his B.S. in physics from the California Institute of Technology in 1943. From 1943 to 1946 h ...

, one of the leaders of the US fusion program. One of the few other devices to show clear evidence of beating the Bohm limit at that time was the multipole

A multipole expansion is a mathematical series representing a function that depends on angles—usually the two angles used in the spherical coordinate system (the polar and azimuthal angles) for three-dimensional Euclidean space, \R^3. Multipol ...

concept. Both Lawrence Livermore and the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory

Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) is a United States Department of Energy national laboratory for plasma physics and nuclear fusion science. Its primary mission is research into and development of fusion as an energy source. It is know ...

(PPPL), home of Spitzer's stellarator, were building variations on the multipole design. While moderately successful on their own, T-3 greatly outperformed either machine. Bishop was concerned that the multipoles were redundant and thought the US should consider a tokamak of its own.

When he raised the issue at a December 1968 meeting, directors of the labs refused to consider it. Melvin B. Gottlieb of Princeton was exasperated, asking "Do you think that this committee can out-think the scientists?" With the major labs demanding they control their own research, one lab found itself left out. Oak Ridge had originally entered the fusion field with studies for reactor fueling systems, but branched out into a mirror program of their own. By the mid-1960s, their DCX designs were running out of ideas, offering nothing that the similar program at the more prestigious and politically powerful Livermore did not. This made them highly receptive to new concepts.

After a considerable internal debate, Herman Postma

Herman Postma (March 29, 1933 – November 7, 2004) was an American scientist and educational leader. Born in Wilmington, North Carolina, he moved to Oak Ridge, Tennessee, in 1959 after attending Duke, Harvard and MIT. Much of Postma's career was ...

formed a small group in early 1969 to consider the tokamak. They came up with a new design, later christened Ormak, that had several novel features. Primary among them was the way the external field was created in a single large copper block, fed power from a large transformer

In electrical engineering, a transformer is a passive component that transfers electrical energy from one electrical circuit to another circuit, or multiple Electrical network, circuits. A varying current in any coil of the transformer produces ...

below the torus. This was as opposed to traditional designs that used electric current windings on the outside. They felt the single block would produce a much more uniform field. It would also have the advantage of allowing the torus to have a smaller major radius, lacking the need to route cables through the donut hole, leading to a lower ''aspect ratio

The aspect ratio of a geometry, geometric shape is the ratio of its sizes in different dimensions. For example, the aspect ratio of a rectangle is the ratio of its longer side to its shorter side—the ratio of width to height, when the rectangl ...

'', which the Soviets had already suggested would produce better results.

Tokamak race in the US

In early 1969, Artsimovich visited MIT

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Established in 1861, MIT has played a significant role in the development of many areas of modern technology and sc ...

, where he was hounded by those interested in fusion. He finally agreed to give several lectures in April and then allowed lengthy question-and-answer sessions. As these went on, MIT itself grew interested in the tokamak, having previously stayed out of the fusion field for a variety of reasons. Bruno Coppi was at MIT at the time, and following the same concepts as Postma's team, came up with his own low-aspect-ratio concept, Alcator. Instead of Ormak's toroidal transformer, Alcator used traditional ring-shaped magnetic field coils but required them to be much smaller than existing designs. MIT's Francis Bitter Magnet Laboratory was the world leader in magnet design and they were confident they could build them.

During 1969, two additional groups entered the field. At General Atomics

General Atomics (GA) is an American energy and defense corporation headquartered in San Diego, California, that specializes in research and technology development. This includes physics research in support of nuclear fission and nuclear fusion en ...

, Tihiro Ohkawa

was a Japanese physicist whose field of work was in plasma physics and fusion power. He was a pioneer in developing ways to generate electricity by nuclear fusion when he worked at General Atomics. Ohkawa died September 27, 2014, in La Jolla, Cal ...

had been developing multipole reactors, and submitted a concept based on these ideas. This was a tokamak that would have a non-circular plasma cross-section; the same math that suggested a lower aspect-ratio would improve performance also suggested that a C or D-shaped plasma would do the same. He called the new design Doublet. Meanwhile, a group at University of Texas at Austin

The University of Texas at Austin (UT Austin, UT, or Texas) is a public university, public research university in Austin, Texas, United States. Founded in 1883, it is the flagship institution of the University of Texas System. With 53,082 stud ...

was proposing a relatively simple tokamak to explore heating the plasma through deliberately induced turbulence, the Texas Turbulent Tokamak.

When the members of the Atomic Energy Commissions' Fusion Steering Committee met again in June 1969, they had "tokamak proposals coming out of our ears". The only major lab working on a toroidal design that was not proposing a tokamak was Princeton, who refused to consider it in spite of their Model C stellarator being just about perfect for such a conversion. They continued to offer a long list of reasons why the Model C should not be converted. When these were questioned, a furious debate broke out about whether the Soviet results were reliable.

Watching the debate take place, Gottlieb had a change of heart. There was no point moving forward with the tokamak if the Soviet electron temperature measurements were not accurate, so he formulated a plan to either prove or disprove their results. While swimming in the pool during the lunch break, he told Harold Furth his plan, to which Furth replied: "well, maybe you're right." After lunch, the various teams presented their designs, at which point Gottlieb presented his idea for a "stellarator-tokamak" based on the Model C.

The Standing Committee noted that this system could be complete in six months, while Ormak would take a year. It was only a short time later that the confidential results from the Culham Five were released. When they met again in October, the Standing Committee released funding for all of these proposals. The Model C's new configuration, soon named Symmetrical Tokamak

Symmetry () in everyday life refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, the term has a more precise definition and is usually used to refer to an object that is invariant under some transformations ...

, intended to simply verify the Soviet results, while the others would explore ways to go well beyond T-3.

Heating: US takes the lead

Experiments on the Symmetric Tokamak began in May 1970, and by early the next year they had confirmed the Soviet results and then surpassed them. The stellarator was abandoned, and PPPL turned its considerable expertise to the problem of heating the plasma. Two concepts seemed to hold promise. PPPL proposed using magnetic compression, a pinch-like technique to compress a warm plasma to raise its temperature, but providing that compression through magnets rather than current. Oak Ridge suggested

Experiments on the Symmetric Tokamak began in May 1970, and by early the next year they had confirmed the Soviet results and then surpassed them. The stellarator was abandoned, and PPPL turned its considerable expertise to the problem of heating the plasma. Two concepts seemed to hold promise. PPPL proposed using magnetic compression, a pinch-like technique to compress a warm plasma to raise its temperature, but providing that compression through magnets rather than current. Oak Ridge suggested neutral beam injection

Neutral-beam injection (NBI) is one method used to heat Plasma (physics), plasma inside a Tokamak, fusion device consisting in a beam of high-energy neutral particles that can enter the magnetic confinement field. When these neutral particles are i ...

, small particle accelerators that would shoot fuel atoms through the surrounding magnetic field where they would collide with the plasma and heat it.

PPPL's Adiabatic Toroidal Compressor (ATC) began operation in May 1972, followed shortly thereafter by a neutral-beam equipped Ormak. Both demonstrated significant problems, but PPPL leapt past Oak Ridge by fitting beam injectors to ATC and provided clear evidence of successful heating in 1973. This success "scooped" Oak Ridge, who fell from favour within the Washington Steering Committee.

By this time a much larger design based on beam heating was under construction, the Princeton Large Torus

The Princeton Large Torus (or PLT), was an early tokamak built at the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL). It was one of the first large scale tokamak machines and among the most powerful in terms of current and magnetic fields. Originally ...

, or PLT. PLT was designed specifically to "give a clear indication whether the tokamak concept plus auxiliary heating can form a basis for a future fusion reactor".[

These experiments, especially PLT, put the US far in the lead in tokamak research. This is due largely to budget; a tokamak cost about $500,000 and the US annual fusion budget was around $25 million at that time. They could afford to explore all of the promising methods of heating, ultimately discovering neutral beams to be among the most effective.

During this period, Robert Hirsch took over the Directorate of fusion development in the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission. Hirsch felt that the program could not be sustained at its current funding levels without demonstrating tangible results. He began to reformulate the entire program. What had once been a lab-led effort of mostly scientific exploration was now a Washington-led effort to build a working power-producing reactor. This was given a boost by the ]1973 oil crisis

In October 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) announced that it was implementing a total oil embargo against countries that had supported Israel at any point during the 1973 Yom Kippur War, which began after Eg ...

, which led to greatly increased research into alternative energy

Renewable energy (also called green energy) is energy made from renewable resource, renewable natural resources that are replenished on a human lifetime, human timescale. The most widely used renewable energy types are solar energy, wind pow ...

systems.

1980s: great hope, great disappointment

By the late-1970s, tokamaks had reached all the conditions needed for a practical fusion reactor; in 1978 PLT had demonstrated ignition temperatures, the next year the Soviet T-7 successfully used

By the late-1970s, tokamaks had reached all the conditions needed for a practical fusion reactor; in 1978 PLT had demonstrated ignition temperatures, the next year the Soviet T-7 successfully used superconducting

Superconductivity is a set of physical properties observed in superconductors: materials where electrical resistance vanishes and magnetic fields are expelled from the material. Unlike an ordinary metallic conductor, whose resistance decreases g ...

magnets for the first time, Doublet proved to be a success and led to almost all future designs adopting this "shaped plasma" approach. It appeared all that was needed to build a power-producing reactor was to put all of these design concepts into a single machine, one that would be capable of running with the radioactive tritium

Tritium () or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of ~12.33 years. The tritium nucleus (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of the ...

in its fuel mix.

During the 1970s, four major second-generation proposals were funded worldwide. The Soviets continued their development lineage with the T-15, while a pan-European effort was developing the Joint European Torus

The Joint European Torus (JET) was a magnetically confined plasma physics experiment, located at Culham Centre for Fusion Energy in Oxfordshire, UK. Based on a tokamak design, the fusion research facility was a joint European project with the ...

(JET) and Japan began the JT-60

JT-60 (short for Japan Torus-60) is a large research tokamak, the flagship of the Japanese National Institute for Quantum Science and Technology's fusion energy directorate. As of 2023 the device is known as JT-60SA and is the largest operat ...

effort (originally known as the "Breakeven Plasma Test Facility"). In the US, Hirsch began formulating plans for a similar design, skipping over proposals for another stepping-stone design directly to a tritium-burning one. This emerged as the Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor

The Tokamak Fusion Test Reactor (TFTR) was an experimental tokamak built at Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory (PPPL) circa 1980 and entering service in 1982. TFTR was designed with the explicit goal of reaching scientific breakeven, the point w ...

(TFTR), run directly from Washington and not linked to any specific lab. Originally favouring Oak Ridge as the host, Hirsch moved it to PPPL after others convinced him they would work the hardest on it because they had the most to lose.

The excitement was so widespread that several commercial ventures to produce commercial tokamaks began around this time. Best known among these, in 1978, Bob Guccione

Robert Charles Joseph Edward Sabatini Guccione ( ; December 17, 1930 – October 20, 2010) was an American visual artist, photographer and publisher. He founded the adult magazine '' Penthouse'' in 1965. This was aimed at competing with ''Playbo ...

, publisher of Penthouse Magazine

''Penthouse'' is a List of men's magazines, men's magazine founded by Bob Guccione and published by Los Angeles–based Penthouse World Media, LLC. It combines urban lifestyle articles and Softcore pornography, softcore pornographic pictures of ...

, met Robert Bussard

Robert W. Bussard (August 11, 1928 – October 6, 2007) was an American physicist who worked primarily in nuclear fusion energy research. He was the recipient of the Schreiber-Spence Achievement Award for STAIF-2004. He was also a fellow of th ...

and became the world's biggest and most committed private investor in fusion technology, ultimately putting $20 million of his own money into Bussard's Compact Tokamak. Funding by the Riggs Bank

Riggs Bank was a bank headquartered in Washington, D.C. For most of its history, it was the largest bank headquartered in that city. On May 13, 2005, after the exposure of several money laundering scandals, the bank was acquired by PNC Financia ...

led to this effort being known as the Riggatron.

TFTR won the construction race and began operation in 1982, followed shortly by JET in 1983 and JT-60 in 1985. JET quickly took the lead in critical experiments, moving from test gases to deuterium and increasingly powerful "shots". But it soon became clear that none of the new systems were working as expected. A host of new instabilities appeared, along with a number of more practical problems that continued to interfere with their performance. On top of this, dangerous "excursions" of the plasma hitting with the walls of the reactor were evident in both TFTR and JET. Even when working perfectly, plasma confinement at fusion temperatures, the so-called "fusion triple product

The Lawson criterion is a figure of merit used in nuclear fusion research. It compares the rate of energy being generated by fusion reactions within the fusion fuel to the rate of energy losses to the environment. When the rate of production is ...

", continued to be far below what would be needed for a practical reactor design.

Through the mid-1980s the reasons for many of these problems became clear, and various solutions were offered. However, these would significantly increase the size and complexity of the machines. A follow-on design incorporating these changes would be both enormous and vastly more expensive than either JET or TFTR. A new period of pessimism descended on the fusion field.

ITER

At the same time these experiments were demonstrating problems, much of the impetus for the US's massive funding disappeared; in 1986 Ronald Reagan

Ronald Wilson Reagan (February 6, 1911 – June 5, 2004) was an American politician and actor who served as the 40th president of the United States from 1981 to 1989. He was a member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican Party a ...

declared the 1970s energy crisis

The 1970s energy crisis occurred when the Western world, particularly the United States, Canada, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, faced substantial petroleum shortages as well as elevated prices. The two worst crises of this period wer ...

was over, and funding for advanced energy sources had been slashed in the early 1980s.

Some thought of an international reactor design had been ongoing since June 1973 under the name INTOR, for INternational TOkamak Reactor. This was originally started through an agreement between Richard Nixon

Richard Milhous Nixon (January 9, 1913April 22, 1994) was the 37th president of the United States, serving from 1969 until Resignation of Richard Nixon, his resignation in 1974. A member of the Republican Party (United States), Republican ...

and Leonid Brezhnev

Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev (19 December 190610 November 1982) was a Soviet politician who served as the General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1964 until Death and state funeral of Leonid Brezhnev, his death in 1982 as w ...

, but had been moving slowly since its first real meeting on 23 November 1978.

During the Geneva Summit in November 1985, Reagan raised the issue with Mikhail Gorbachev

Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev (2 March 1931 – 30 August 2022) was a Soviet and Russian politician who served as the last leader of the Soviet Union from 1985 to dissolution of the Soviet Union, the country's dissolution in 1991. He served a ...

and proposed reforming the organization. "... The two leaders emphasized the potential importance of the work aimed at utilizing controlled thermonuclear fusion for peaceful purposes and, in this connection, advocated the widest practicable development of international cooperation in obtaining this source of energy, which is essentially inexhaustible, for the benefit for all mankind."

The next year, an agreement was signed between the US, Soviet Union, European Union and Japan, creating the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor

ITER (initially the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, ''iter'' meaning "the way" or "the path" in Latin) is an international nuclear fusion research and engineering megaproject aimed at creating energy through a fusion process s ...

organization.

Design work began in 1988, and since that time the ITER reactor has been the primary tokamak design effort worldwide.

High Field Tokamaks

It has been known for a long time that stronger field magnets would enable high energy gain in a much smaller tokamak, with concepts such a

FIRE, IGNITOR

and the Compact Ignition Tokamak (CIT) being proposed decades ago.

The commercial availability of high temperature superconductors (HTS) in the 2010s opened a promising pathway to building the higher field magnets required to achieve ITER-like levels of energy gain in a compact device. To leverage this new technology, the MIT Plasma Science and Fusion Center (PSFC) and MIT spinout Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS) successfully built and tested th

Toroidal Field Model Coil (TFMC)

in 2021 to demonstrate the necessary 20 Tesla magnetic field needed to build SPARC, a device designed to achieve a similar fusion gain as ITER but with only ~1/40th ITER's plasma volume.

British startup Tokamak Energy is also planning on building a net-energy tokamak using HTS magnets, but with the spherical tokamak variant.