Tinoceras on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Uintatherium'' ("Beast of the

Fossils of ''Uintatherium'' were first discovered in the Bridger Basin near Fort Bridger by Lieutenant W. N. Wann in September 1870, and were later described as a new species of ''Titanotherium'', ''Titanotherium anceps'', by

Fossils of ''Uintatherium'' were first discovered in the Bridger Basin near Fort Bridger by Lieutenant W. N. Wann in September 1870, and were later described as a new species of ''Titanotherium'', ''Titanotherium anceps'', by  Many additional discoveries of ''Uintatherium'' have since occurred, making it one of the best-known and popular American fossil mammals.

Many additional discoveries of ''Uintatherium'' have since occurred, making it one of the best-known and popular American fossil mammals.

Uinta Mountains

The Uinta Mountains ( ) are an east-west trending mountain range in northeastern Utah extending a short distance into northwest Colorado and slightly into southwestern Wyoming in the United States. As a subrange of the Rocky Mountains, they are u ...

") is an extinct genus of herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically evolved to feed on plants, especially upon vascular tissues such as foliage, fruits or seeds, as the main component of its diet. These more broadly also encompass animals that eat n ...

dinocerata

Dinocerata, from Ancient Greek (), "terrible", and (), "horn", or Uintatheria, is an extinct order of large herbivorous hoofed mammals with horns and protuberant canine teeth, known from the Paleocene and Eocene of Asia and North America. With ...

n mammal that lived during the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

epoch. Two species are currently recognized: ''U. anceps'' from the United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

during the Early to Middle Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

(50.5-39.7 million years ago) and ''U. insperatus'' of Middle to Late Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

(48–37 million years ago) China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

. The first fossils of ''Uintatherium'' were recovered in the Fort Bridger Basin, and were initially believed to belong to a new species of brontothere

Brontotheriidae is a family of extinct mammals belonging to the order Perissodactyla, the order that includes horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs. Superficially, they looked rather like rhinos with some developing bony nose horns, and were some of ...

. Despite other generic names being assigned, such as Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

's ''Loxolophodon'' and Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of paleontology. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the preeminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or ...

's ''Tinoceras'', and an assortment of attempts at naming new species, ''Uintatherium anceps'' has since come to encompass all of these.

The phylogeny

A phylogenetic tree or phylogeny is a graphical representation which shows the evolutionary history between a set of species or Taxon, taxa during a specific time.Felsenstein J. (2004). ''Inferring Phylogenies'' Sinauer Associates: Sunderland, M ...

of ''Uintatherium'' and other dinoceratans has long been debated. Originally, they were assigned to the now-invalid order

Order, ORDER or Orders may refer to:

* A socio-political or established or existing order, e.g. World order, Ancien Regime, Pax Britannica

* Categorization, the process in which ideas and objects are recognized, differentiated, and understood

...

Amblypoda

Amblypoda was a taxonomic hypothesis uniting a group of extinct, herbivorous mammals. They were considered a suborder of the primitive ungulate mammals and have since been shown to represent a polyphyletic group.

Characteristics

The Amblypoda take ...

, which united various basal ungulates

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined to b ...

from the Palaeogene. Ambylpoda has since fallen out of use. Since then, various hypotheses of dinoceratan phylogeny have been proposed. The most widespread is that they are related to the South American xenungulates, together forming a mirorder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

called Uintatheriamorpha. If this is correct, dinoceratans, and thus ''Uintatherium'', may not be ungulates at all. However, it has been noted that traits shared between the two groups may be the result of convergent evolution. Within Dinocerata itself, ''Uintatherium'' belongs to the family Uintatheriidae, and is one of two members of Uintatheriinae; the other two are ''Eobasileus

''Eobasileus cornutus'' ("horned dawn-king") was a prehistoric species of Dinocerata, dinocerate mammal.

Description

With a skull about in length, and standing some tall at the shoulder, with a weight estimated to be around , ''Eobasileus'' ...

'' and ''Tetheopsis

''Tetheopsis'' is an extinct genus of dinocerates.

References

Taxa named by Edward Drinker Cope

Dinoceratans

Fossil taxa described in 1885

Prehistoric placental genera

{{Paleo-mammal-stub ...

''.

''Uintatherium'' was a very large animal, with ''U. anceps'' having a shoulder height of and a body mass of . The largest ''Uintatherium'' skulls known, originally assigned to ''Loxolophodon'', measure in length. It is overall similar to the other two uintatheriine genera, though it had a broader skull. Like them, ''Uintatherium''canine

Canine may refer to:

Zoology and anatomy

* Animals of the family Canidae, more specifically the subfamily Caninae, which includes dogs, wolves, foxes, jackals and coyotes

** ''Canis'', a genus that includes dogs, wolves, coyotes, and jackals

** Do ...

and cheek teeth

Cheek teeth or postcanines comprise the molar and premolar teeth in mammals. Cheek teeth are multicuspidate (having many folds or tubercles). Mammals have multicuspidate molars (three in placentals, four in marsupials, in each jaw quadrant) and ...

, and one pair toward the back of the skull. ''Eobasileus''sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, and may have been used in display or for defense. Behind the skull, the skeleton of ''Uintatherium'' bears a combination of characteristics often associated with proboscideans

Proboscidea (; , ) is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three liv ...

(elephants and relatives) and rhinocerotids.

''Uintatherium'' evolved during the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum, a period which saw some of the highest global temperatures in Earth's history. Most of the North American continent was covered in closed-canopy forests, with the Bridger Formation

The Bridger Formation is a Formation (geology), geologic formation in southwestern Wyoming. It preserves fossils dating back to the Bridgerian and Uintan North American land mammal age, stages of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period. The formati ...

, one of the localities ''U. anceps'' is best known from, consisting of an inland lake surrounded by birch

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains 3 ...

, elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

and redwood

Sequoioideae, commonly referred to as redwoods, is a subfamily of Pinophyta, coniferous trees within the family (biology), family Cupressaceae, that range in the Northern Hemisphere, northern hemisphere. It includes the List of superlative tree ...

trees. The depositional environment of the later Uinta Formation

The Uinta Formation is a geologic formation in northeastern Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Ariz ...

was interspersed by open savannahs, resulting from a global cooling event which resulted in the gradual aridification

Aridification is the process of a region becoming increasingly arid, or dry. It refers to long term change, rather than seasonal variation.

It is often measured as the reduction of average soil moisture content.

It can be caused by reduced preci ...

of North America. The Chinese ''U. insperatus'' lived in a brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

environment mixed with a semi-arid steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

.

Taxonomy

Early history

Fossils of ''Uintatherium'' were first discovered in the Bridger Basin near Fort Bridger by Lieutenant W. N. Wann in September 1870, and were later described as a new species of ''Titanotherium'', ''Titanotherium anceps'', by

Fossils of ''Uintatherium'' were first discovered in the Bridger Basin near Fort Bridger by Lieutenant W. N. Wann in September 1870, and were later described as a new species of ''Titanotherium'', ''Titanotherium anceps'', by Othniel Charles Marsh

Othniel Charles Marsh (October 29, 1831 – March 18, 1899) was an American professor of paleontology. A prolific fossil collector, Marsh was one of the preeminent paleontologists of the nineteenth century. Among his legacies are the discovery or ...

in 1871. The specimen (YPM 11030) only consisted of several skull pieces, including the right parietal horn, and fragmentary postcrania. The following year, Marsh and Joseph Leidy

Joseph Mellick Leidy (September 9, 1823 – April 30, 1891) was an American paleontologist, parasitologist and anatomist.

Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, later becoming a professor of natural history at Swarth ...

collected in the Eocene Beds near Fort Bridger while Edward Drinker Cope

Edward Drinker Cope (July 28, 1840 – April 12, 1897) was an American zoologist, paleontology, paleontologist, comparative anatomy, comparative anatomist, herpetology, herpetologist, and ichthyology, ichthyologist. Born to a wealthy Quaker fam ...

, Marsh's competitor

Competition is a rivalry where two or more parties strive for a common goal which cannot be shared: where one's gain is the other's loss (an example of which is a zero-sum game). Competition can arise between entities such as organisms, individ ...

, excavated in the Washakie Basin. In August 1872, Leidy named ''Uintatherium robustum'' based on a posterior skull and partial mandibles (ANSP 12607). Another specimen discovered by Leidy's crews consisting of a canine was named ''Uintamastix atrox'' and was thought to have been a saber-toothed and carnivorous.

Eighteen days after the description of ''Uintatherium'', Cope and Marsh both named new genera of Uinta dinocerata

Dinocerata, from Ancient Greek (), "terrible", and (), "horn", or Uintatheria, is an extinct order of large herbivorous hoofed mammals with horns and protuberant canine teeth, known from the Paleocene and Eocene of Asia and North America. With ...

ns, Cope naming ''Loxolophodon'' in his "garbled" telegram and Marsh dubbed ''Tinoceras''. Due to ''Uintatherium'' being named first, Cope and Marsh's genera are synonymous with ''Uintatherium''. Cope described two genera in his telegram, ''Loxolophodon'' and ''Eobasileus

''Eobasileus cornutus'' ("horned dawn-king") was a prehistoric species of Dinocerata, dinocerate mammal.

Description

With a skull about in length, and standing some tall at the shoulder, with a weight estimated to be around , ''Eobasileus'' ...

''; the latter is currently considered separate from ''Uintatherium''. ''Tinoceras'' was a new genus made for ''Titanotherium anceps'' by Marsh. Several days later, Marsh erected the genus ''Dinoceras''. ''Dinoceras'' and ''Tinoceras'' would receive several additional species by Marsh throughout the 1870s and 1880s, many based on fragmentary material. Several complete skulls were found by Cope and Marsh crews, leading to theories like Cope's proboscidean assessment. Because of Cope and Marsh's rivalry, the two would often publish scathing criticisms of each other's work, stating their respective genera were valid. The trio would name 25 species now considered synonymous with Marsh's original species, ''Titanotherium anceps'', which was placed in Leidy's genus, ''Uintatherium''. In 1876, William Henry Flower

Sir William Henry Flower (30 November 18311 July 1899) was an English surgeon, museum curator and comparative anatomist, who became a leading authority on mammals and especially on the primate brain. He supported Thomas Henry Huxley in an ...

, Hunterian Professor of Comparative Anatomy, wrote a letter in ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' wherein he formally suggested incorporating all of Cope's, Leidy's, and Marsh's taxa into ''Uintatherium'', due to it being named first (which would make it a senior synonym

In taxonomy, the scientific classification of living organisms, a synonym is an alternative scientific name for the accepted scientific name of a taxon. The botanical and zoological codes of nomenclature treat the concept of synonymy differently.

...

), and a lack of convincing evidence for their separation.

Many additional discoveries of ''Uintatherium'' have since occurred, making it one of the best-known and popular American fossil mammals.

Many additional discoveries of ''Uintatherium'' have since occurred, making it one of the best-known and popular American fossil mammals. Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

launched expeditions to the Eocene beds of Wyoming in the 1870s and 1880s, discovering several partial since skulls and naming several species of uintatheres that are now considered synonyms of ''U. anceps''. Major reassessment came in the 1960s by Walter Wheeler, who synonymized and redescribed many of the ''Uintatherium'' fossils discovered during the 19th century A cast of a ''Uintatherium'' skeleton

A skeleton is the structural frame that supports the body of most animals. There are several types of skeletons, including the exoskeleton, which is a rigid outer shell that holds up an organism's shape; the endoskeleton, a rigid internal fra ...

is on display at the Utah Field House of Natural History State Park. A skeleton of ''Uintatherium'' is also on display at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History

The National Museum of Natural History (NMNH) is a natural history museum administered by the Smithsonian Institution, located on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., United States. It has free admission and is open 364 days a year. With ...

in Washington, DC.

Fossils assigned tentatively to ''Uintatherium'' have been described from parts of Asia since 1962, when Zhou Mingzhen and Y. S. Zhou reported teeth (the third upper molar and two upper canines) closely resembling those of the genus from Xintai

Xintai () is a county-level city in the central part of Shandong province, People's Republic of China. It is the easternmost county-level division of the prefecture-level city of Tai'an and is located about to the southeast of downtown Tai'an.

...

, Shandong

Shandong is a coastal Provinces of China, province in East China. Shandong has played a major role in Chinese history since the beginning of Chinese civilization along the lower reaches of the Yellow River. It has served as a pivotal cultural ...

, China. In 1977, Gabounia reported fossils possibly referrable to ''Uintatherium'' had been recovered from Tschaibulak, near Zaisan, Kazakhstan. These were both referred to an indeterminate position within Uintatheriidae, not to ''Uintatherium'' itself, though the former was documented as cf. ''Uintatherium'' sp. In November of 1978, the first unambiguous Asian specimen of ''Uintatherium'' was recovered. Wang Daning, Tong Shuisheng, and Wang Chuanqiao, working at strata from the lower part of the Lushi Formation (Henan Province

Henan; alternatively Honan is a province in Central China. Henan is home to many heritage sites, including Yinxu, the ruins of the final capital of the Shang dynasty () and the Shaolin Temple. Four of the historical capitals of China, Luo ...

, China), recovered an almost intact skull. Aside from damage to the nasal bone

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

and zygomatic arches

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the opening of the ear) and the temporal ...

, it was essentially complete. The latter two wrote that the skull likely belonged to an elderly individual due to the condition of the teeth, which were severely worn. In 1981, the specimen was described. It was assigned to a new species of ''Uintatherium'', ''U. insperatus''.

Classification

''Uintatherium'' was initially regarded by Marsh as abrontothere

Brontotheriidae is a family of extinct mammals belonging to the order Perissodactyla, the order that includes horses, rhinoceroses, and tapirs. Superficially, they looked rather like rhinos with some developing bony nose horns, and were some of ...

. However, similarities to proboscideans

Proboscidea (; , ) is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three liv ...

(relatives of elephants), noted by various authors,'''' lead Cope to classify it as a member of that group. While he acknowledged Marsh's reasoning, he nonetheless believed that it stemmed from "unusual sources", and that: "The absence of incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

teeth no more relates these animals to the Artiodactyla than it relates the sloth

Sloths are a Neotropical realm, Neotropical group of xenarthran mammals constituting the suborder Folivora, including the extant Arboreal locomotion, arboreal tree sloths and extinct terrestrial ground sloths. Noted for their slowness of move ...

to the same order ..the presence of paired horns no more constitutes affinity to the ruminants than it does in the case of the ' horned-toad'." It has since been recognised that similarities to proboscideans are likely the product of convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last comm ...

. ''Uintatherium'' was reclassified by Henry Fairfield Osborn in 1881 as part of the order Dinocerata

Dinocerata, from Ancient Greek (), "terrible", and (), "horn", or Uintatheria, is an extinct order of large herbivorous hoofed mammals with horns and protuberant canine teeth, known from the Paleocene and Eocene of Asia and North America. With ...

. At the time, dinocerates were believed to be part of Amblypoda

Amblypoda was a taxonomic hypothesis uniting a group of extinct, herbivorous mammals. They were considered a suborder of the primitive ungulate mammals and have since been shown to represent a polyphyletic group.

Characteristics

The Amblypoda take ...

, a group uniting an assortment of basal ungulates from the Palaeogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

, and were sometimes referred to simply as "dinoceratous amblypods".

The group Amblypoda has since fallen out of use, and is generally regarded as polyphyletic

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as Homoplasy, homoplasies ...

, meaning that it was an unnatural group consisting of an assortment of distantly related clades. Dinocerata, however, has persisted, though the precise relationships of the order have been the subject of debate. Relationships with South American native ungulates

South American native ungulates, commonly abbreviated as SANUs, are extinct ungulate-like mammals that were indigenous to South America from the Paleocene (from at least 63 million years ago) until the end of the Late Pleistocene (~12,000 years a ...

(SANUs), specifically xenungulates, have been suggested, with Spencer G. Lucas and Robert M. Schoch in 1998 supporting the complete removal of both clades from Ungulata. If dinoceratans and xenungulates are indeed related, they may constitute the mirorder

Order () is one of the eight major hierarchical taxonomic ranks in Linnaean taxonomy. It is classified between family and class. In biological classification, the order is a taxonomic rank used in the classification of organisms and recognized ...

Uintatheriamorpha. However, it has been stated that no strong evidence for this relationship exists, and that similarities may simply be the result of convergence. Prothero, Manning, and Fischer, in 1988, suggested that dinoceratans and pyrotheres were part of Paenungulata

Paenungulata (from Latin ''paene'' "almost" + ''ungulātus'' "having hoofs") is a clade of "sub- ungulates", which groups three extant mammal orders: Proboscidea (including elephants), Sirenia ( sea cows, including dugongs and manatees), and ...

(now consisting solely of hyracoid

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, stout, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the family Procaviidae within the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Modern hyraxes are typically between in length an ...

and tethythere afrotheres), which by their definition also included perissodactyls. Bruce J. Shockey and Federico Anaya Daza, in 2003, rejected the use of the term Uintatheriamorpha, considering the supporting data too weak. Regardless, a phylogenetic analysis published in 2019 by Thomas Halliday et al. recovered ''Uintatherium'' (the only dinoceratan included in the dataset) within a clade consisting entirely of SANUs, as the most basal branch of a clade otherwise consisting of ''Astraponotus

''Astraponotus'' is an extinct genus of astrapotheriids. It lived during the Middle-Late Eocene (in the Mustersan and Tinguirirican of the South American land mammal ages (SALMA), 48-33.9 million years ago) and its fossil remains have been fou ...

'', ''Carodnia

''Carodnia'' is an extinct genus of South American ungulate known from the Early Eocene of Brazil, Argentina, and Peru.

''Carodnia'' is placed in the order Xenungulata together with '' Etayoa'' and '' Notoetayoa''.

''Carodnia'' is the largest ...

'', ''Parastrapotherium

''Parastrapotherium'' is an extinct genus of South American land mammal that existed from the Late Oligocene (Deseadan SALMA) to the Early Miocene (Colhuehuapian SALMA). The genus includes some of the largest and smallest known astrapotherians, ...

'', and ''Pyrotherium

''Pyrotherium'' ('fire beast') is an extinct genus of South American ungulate in the order Pyrotheria, that lived in what is now Argentina and Bolivia during the Late Oligocene.

A cladogram showing the phylogenetic position of ''Uintatherium'', after Halliday et al. (2019), is as follows:Dinocerata has historically been divided into two families: Prodinoceratidae, and Uintatheriidae. The latter family consists of the majority of dinocerate genera, and has itself been divided into Gobiatheriinae and Uintatheriinae; occasionally, the latter has been divided even further, down to

The skull of ''Uintatherium'' is roughly three times longer than it is wide. Most ''U. anceps'' skulls range from in length, whereas the only known ''U. insperatus'' skull measures . Some specimens have skulls which, when measured at the

The skull of ''Uintatherium'' is roughly three times longer than it is wide. Most ''U. anceps'' skulls range from in length, whereas the only known ''U. insperatus'' skull measures . Some specimens have skulls which, when measured at the

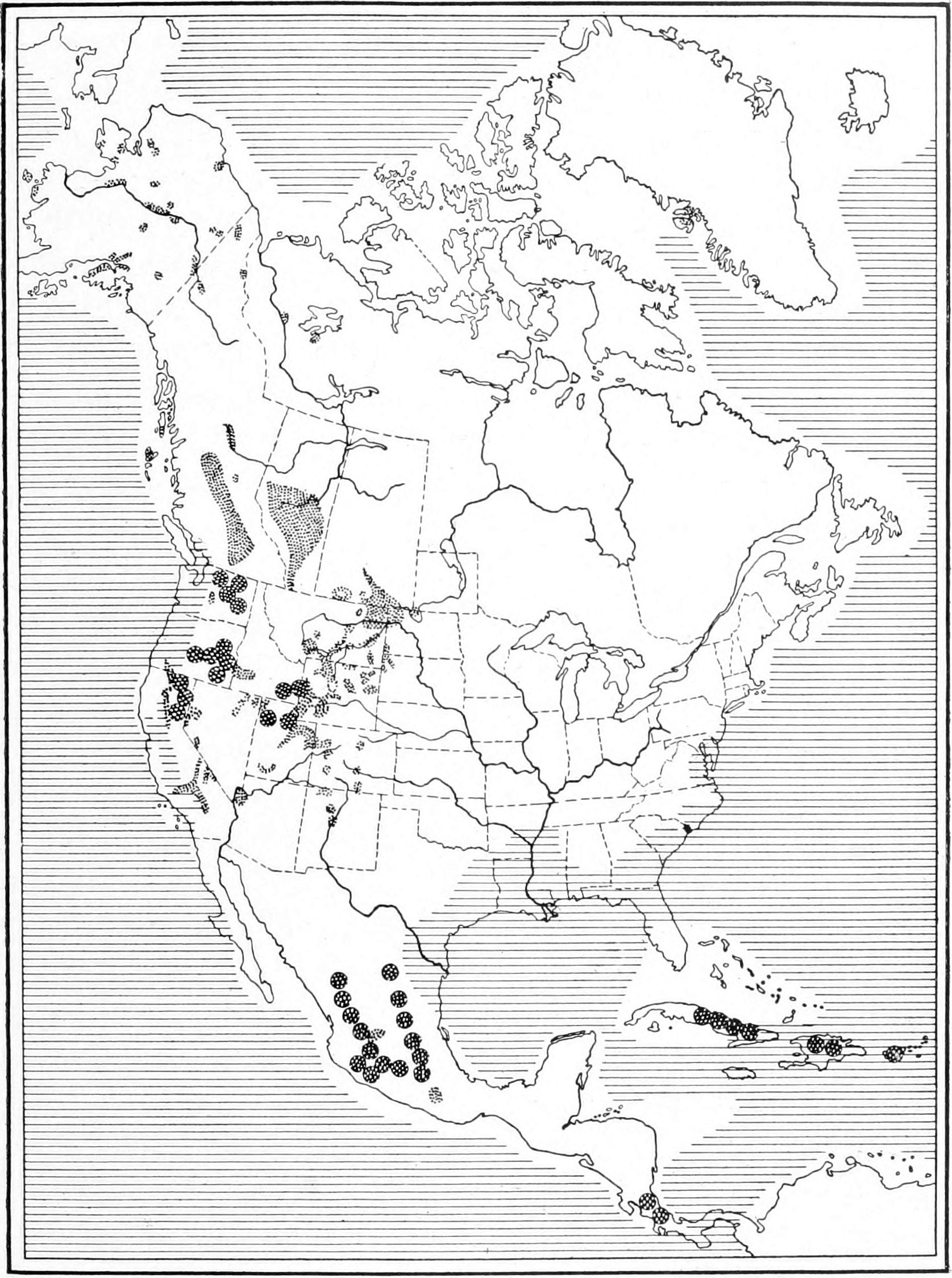

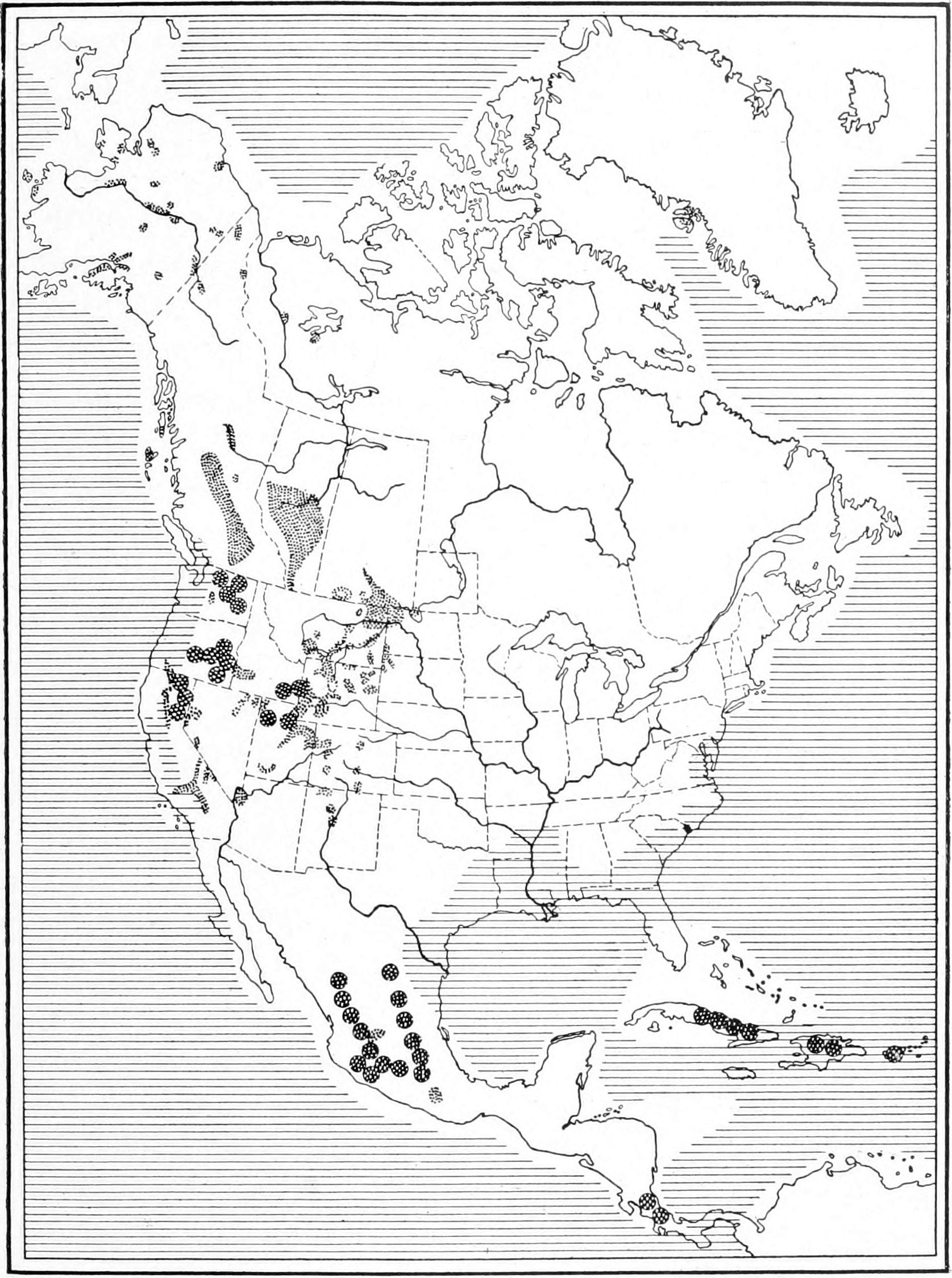

''Uintatherium anceps'' is known from various

''Uintatherium anceps'' is known from various  In the transition from the Bridgerian to the Uintan, several of these animals became extinct and new forms emerged. The oxyaenids and phenacodontids disappeared during this transition and new groups like the oromerycids and the earliest

In the transition from the Bridgerian to the Uintan, several of these animals became extinct and new forms emerged. The oxyaenids and phenacodontids disappeared during this transition and new groups like the oromerycids and the earliest

Academy of Natural SciencesWood, Horace Elmer 1923, The problem of the Uintatherium molars, Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History; v. 48, article 18

{{Taxonbar, from=Q131558 Dinoceratans Eocene mammals of North America Fossil taxa described in 1872 Taxa named by Joseph Leidy Paleontology in Wyoming Paleontology in Utah Paleontology in Henan Prehistoric placental genera Eocene mammals of Asia

tribe

The term tribe is used in many different contexts to refer to a category of human social group. The predominant worldwide use of the term in English is in the discipline of anthropology. The definition is contested, in part due to conflict ...

level (Bathyopsini and Uintatheriini) Walter H. Wheeler suggested in 1961 that the taxa now classed as uintatheriines formed a primarily anagenetic

Anagenesis is the gradual evolution of a species that continues to exist as an interbreeding population. This contrasts with cladogenesis, which occurs when branching or splitting occurs, leading to two or more lineages and resulting in separate ...

lineage, and that ''Uintatherium'' was one of few diverging genera, possibly evolving from '' Bathyopsis middleswarti'' (which he believed to be ancestral to both ''Uintatherium'' and later dinocerates). Robert M. Shoch and Spencer G. Lucas, in 1985, performed a phylogenetic analysis of Dinocerata, and recovered ''Uintatherium'' as the sister taxon to a clade consisting of ''Eobasileus

''Eobasileus cornutus'' ("horned dawn-king") was a prehistoric species of Dinocerata, dinocerate mammal.

Description

With a skull about in length, and standing some tall at the shoulder, with a weight estimated to be around , ''Eobasileus'' ...

'' and ''Tetheopsis

''Tetheopsis'' is an extinct genus of dinocerates.

References

Taxa named by Edward Drinker Cope

Dinoceratans

Fossil taxa described in 1885

Prehistoric placental genera

{{Paleo-mammal-stub ...

'', slightly more derived than ''Bathyopsis''. William D. Turnbull, however, suggested in 2002 that both ''Tetheopsis'' species could be lumped into ''Eobasileus'', and that Uintatheriini might thus consist exclusively of ''Eobasileus'' and ''Uintatherium''.

Description

''Uintatherium'' was a large animal, with ''U. anceps'' standing at the shoulder. Several body mass estimates have been proposed for the genus. In a 1963 work, Harry J. Jerison provided various mass estimates for a multitude of Palaeogene taxa. An average of two estimates resulted in a mass of , while the use of scale models resulted in a range of . John Damuth, using head–body length and data from teeth recovered considerably a smaller body mass of . Using Jerison's methods and additional data provided by Damuth, in 2002, William D. Turnbull proposed an estimate of . He recovered larger masses in other analyses, though expressed his belief that these were overestimates due to the methodologies applied. Nevertheless, in 1998, Spencer G. Lucas and Robert M. Shoch provided an even larger body mass of for ''U. anceps''. The size of ''U. insperatus'' is not certain, though it is believed to have been smaller. Despite its size, ''U. anceps'' was exceeded in sized by related taxa such as ''Eobasileus''. ''Uintatherium'' as a whole appears to have exhibited strong sexual dimorphism: males had larger canines, larger flanges on the lower jaws, larger sagittal crests, larger horns, and an overall larger body size. As it was a fairly large mammal which lived mostly in temperate environments,William Berryman Scott

William Berryman Scott (February 12, 1858 – March 29, 1947) was an American vertebrate paleontologist, authority on mammals, and principal author of the White River Oligocene monographs. He was a professor of geology and paleontology at Pr ...

suggested that ''Uintatherium'' may have been predominantly hairless, though noted that there is no direct evidence.

Skull

The skull of ''Uintatherium'' is roughly three times longer than it is wide. Most ''U. anceps'' skulls range from in length, whereas the only known ''U. insperatus'' skull measures . Some specimens have skulls which, when measured at the

The skull of ''Uintatherium'' is roughly three times longer than it is wide. Most ''U. anceps'' skulls range from in length, whereas the only known ''U. insperatus'' skull measures . Some specimens have skulls which, when measured at the zygomatic arches

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the opening of the ear) and the temporal ...

, are roughly wide, suggesting a very large overall skull size. Furthermore, some specimens initially referred to ''Loxolophodon'' have skull lengths of up to , nearly a third larger than most others. The skull of ''U. anceps'' can be distinguished from those of other uintatheriins (if that clade exists) by its broadness, while that of ''U. insperatus'' was slenderer. ''Eobasileus'' and ''Tetheopsis'' have skulls which are relatively longer and slenderer than ''U. anceps''nasal bones

The nasal bones are two small oblong bones, varying in size and form in different individuals; they are placed side by side at the middle and upper part of the face and by their junction, form the bridge of the upper one third of the nose.

Eac ...

of ''Uintatherium'' are very long, comprising roughly half of the total length of the skull. They project far enough that they completely overhang the external nares

A nostril (or naris , : nares ) is either of the two orifices of the nose. They enable the entry and exit of air and other gasses through the nasal cavities. In birds and mammals, they contain branched bones or cartilages called turbinates, wh ...

. ''Uintatherium'' had large zygomatic arches

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the opening of the ear) and the temporal ...

, of which the maxilla comprised the anterior (front) portion, similar to proboscideans

Proboscidea (; , ) is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three liv ...

. Like other dinoceratans, the skull of ''Uintatherium'' lacked a postorbital process. At the back of ''Uintatherium''occipital condyles

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the Atlas (anatomy), atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape ...

. To either side of the occipital crest sat a pair of very large parasagittal crests. In some specimens, the lacrimal, the above the orbits (eye sockets), was distally (outwardly) expanded, overhanging the zygomatic arches; in others, those formerly referred to ''Loxolophodon'', the zygomatic arches projected beyond them. Much like other dinoceratans, ''Uintatherium''maxillae

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxillar ...

, sits directly above the diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

(gap) separating the canines and premolars

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mout ...

. The last, the so-called parietal horns, sits far anterior

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position pro ...

to (in front of) the occipital bone

The occipital bone () is a neurocranium, cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lob ...

, on the parasagittal crests. This differs from the related ''Eobasileus'' and ''Tetheopsis'', in which the parietal horns are closer to the occipital. Furthermore, in those two genera, the maxillary set of horns sits above the premolars

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mout ...

, meaning the portion of the snout anterior to the maxillary horns is far longer; in ''Uintatherium'', the portion of the snout anterior to the maxillary horns is fairly short. In ''U. anceps'', the maxillary and parietal horns projected outward slightly, while in ''U. insperatus'', they were essentially erect. Contrary to their occasional description as horns, it is unlikely that any of these outgrowths were cornified (reinforced by keratin), as there is no evidence of the vascularization

Vascularisation is the physiological process through which blood vessels form in tissues or organs. Vascularisation is crucial to supply the organs and tissues with an adequate supply of oxygen and nutrients and for removing waste products.

Bloo ...

necessary for a keratinous covering. It is likely that they were covered only by skin. Nevertheless, Othniel Charles Marsh noted damage to several ''Uintatherium'' horn cores, likely inflicted while the animals were still alive, suggesting that they used their horns in agonistic behaviors. Like other animals with extensive cranial ornamentation, ''Uintatherium''sinuses

Paranasal sinuses are a group of four paired air-filled spaces that surround the nasal cavity. The maxillary sinuses are located under the eyes; the frontal sinuses are above the eyes; the ethmoidal sinuses are between the eyes and the sphenoi ...

, though not to the same extent.

''Uintatherium''proboscis

A proboscis () is an elongated appendage from the head of an animal, either a vertebrate or an invertebrate. In invertebrates, the term usually refers to tubular arthropod mouthparts, mouthparts used for feeding and sucking. In vertebrates, a pr ...

was suggested early on, based on alleged affinities to proboscideans, the structure of the ethmoturbinal bones of the nasal passage

The nasal cavity is a large, air-filled space above and behind the nose in the middle of the face. The nasal septum divides the cavity into two cavities, also known as fossae. Each cavity is the continuation of one of the two nostrils. The nasal c ...

and the structure of the olfactory nerves

The olfactory nerve, also known as the first cranial nerve, cranial nerve I, or simply CN I, is a cranial nerve that contains sensory nerve fibers relating to the sense of smell.

The afferent nerve fibers of the olfactory receptor neurons ...

suggest that no such structure existed. In its place, there may have been a flexible upper lip, analogous to that of modern rhinocerotids.

Projecting from the anteroventral (towards the front and at the bottom) portion of ''Uintatherium''mandibles

In jawed vertebrates, the mandible (from the Latin ''mandibula'', 'for chewing'), lower jaw, or jawbone is a bone that makes up the lowerand typically more mobilecomponent of the mouth (the upper jaw being known as the maxilla).

The jawbone i ...

(lower jaws) are a pair of large flanges. In most specimens, these would have provided support to the large upper canines, though specimens formerly referred to ''Loxolophodon'' had smaller flanges which did not extend as far. It has been suggested that the observed difference in flange size is the result of sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, with larger-flanged jaws belonging to males. Similar structures are observed in the related ''Bathyopsis''. Flanges aside, the lower jaw of ''Uintatherium'' is fairly slender. Unlike most other ungulates, the condyles are deflected posteriorly, likely to accommodate the large upper tusks: without such a modification, the jaws would be unable to fully open. This condition is otherwise only seen in some marsupials

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a ...

and members of the former order Insectivora

The Order (biology), order Insectivora (from Latin ''insectum'' "insect" and ''vorare'' "to eat") is a now-abandoned biological grouping within the class of mammals. Some species have now been moved out, leaving the remaining ones in the order ...

. The mandible's coronoid process is large, curves posteriorly, and is pointed dorsally (at the top). The mandibular condyles are small and convex, and sit slightly above the level of the cheek teeth. Below the condyles, the posterior border of the mandible is very rough, due tothe attachment of the pterygoid muscles.

Dentition

''Uintatherium'' has a dental formula of , though one early record provided a dental formula of . Uintatheriids in general lack upperincisors

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

, and ''Uintatherium'' was no exception. The loss of the upper incisors likely indicates the presence of a firm elastic pad on the ventral portion of the premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

, similar to that of ruminants

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by Enteric fermentation, fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principa ...

. The lower incisors are bilobate, bearing crowns which are split into two distinctive cusps. The lower canines were somewhat incisiform, meaning that they resemble conventional incisors, while the upper canines are large and have been compared to sabres

A sabre is a type of sword.

Sabre, Sabres, saber, or SABRE may also refer to:

Weapons and weapon systems

* Sabre (fencing), a sporting sword

* Sabre (tank), a modern British armoured reconnaissance vehicle

* Chinese sabre or ''dao'', a variet ...

. ''Eobasileus'' and ''Tetheopsis'' have similar canines. The size of the canines, as with their supporting flanges, appears to have been sexually dimorphic, and they may have served a display function or been used in defense. Between the canines and cheek teeth, there is a large gap, the diastema. Behind the diastema are three upper premolars

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mout ...

and three upper molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

, all of which were fairly small. All of ''Uintatherium''brachyodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone tooth ...

, meaning they have short crowns and well-developed roots

A root is the part of a plant, generally underground, that anchors the plant body, and absorbs and stores water and nutrients.

Root or roots may also refer to:

Art, entertainment, and media

* ''The Root'' (magazine), an online magazine focusin ...

; Horace Elmer Wood, in 1923, described them as "inadequate-appearing". The first upper premolar appears to have completely disappeared, with only the occasional preservation of the alveolus

Alveolus (; pl. alveoli, adj. alveolar) is a general anatomical term for a concave cavity or pit.

Uses in anatomy and zoology

* Pulmonary alveolus, an air sac in the lungs

** Alveolar cell or pneumocyte

** Alveolar duct

** Alveolar macrophage

* M ...

(tooth socket); reduced first premolars, on both upper and lower jaws, are a diagnostic trait of dinoceratans. Whether or not the first lower premolar is retained in ''Uintatherium'' is uncertain, as some sources report it as present, while others report it as absent. The third lower molar is very short, with reduced ectoconid and hypoconulid

Many different terms have been proposed for features of the tooth crown in mammals.

The structures within the molars receive different names according to their position and morphology. This nomenclature was developed by Henry Fairfield Osborn i ...

crests. The paraconids and paracristids of all teeth from the third upper premolar to the second upper molar are greatly reduced. As a whole, it has been noted that ''Uintatherium''Vertebral column

Uintatheriines as a whole are characterised by their heavy and robust skeletons, often historically compared toproboscideans

Proboscidea (; , ) is a taxonomic order of afrotherian mammals containing one living family (Elephantidae) and several extinct families. First described by J. Illiger in 1811, it encompasses the elephants and their close relatives. Three liv ...

, though compared by Turnbull to hippopotamuses

The hippopotamus (''Hippopotamus amphibius;'' ; : hippopotamuses), often shortened to hippo (: hippos), further qualified as the common hippopotamus, Nile hippopotamus and river hippopotamus, is a large semiaquatic Mammal, mammal native to su ...

. With the exception of parts of the skull, the known parts of ''Uintatherium''pachyostosis

Pachyostosis is a non-pathological condition in vertebrate animals in which the bones experience a thickening, generally caused by extra layers of lamellar bone. It often occurs together with bone densification ( osteosclerosis), reducing inner c ...

. ''Uintatherium''atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of world map, maps of Earth or of a continent or region of Earth. Advances in astronomy have also resulted in atlases of the celestial sphere or of other planets.

Atlases have traditio ...

, and the second cervical vertebra, the axis

An axis (: axes) may refer to:

Mathematics

*A specific line (often a directed line) that plays an important role in some contexts. In particular:

** Coordinate axis of a coordinate system

*** ''x''-axis, ''y''-axis, ''z''-axis, common names ...

, are particularly proboscidean-like. The atlas in particular is massive, while the axis is short and robust. The rest of the cervical ceries is more elongated than in proboscideans, though still short in relation to the axis. The vertebral centra

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

are taller than they are long, and are in turn wider than they are tall. All of the dorsal (back) vertebrae are opishthocoelous, convex anteriorly and concave posteriorly; the same condition is seen in proboscideans, but in them, it is more extreme. The first thoracic vertebra

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebra (anatomy), vertebrae of intermediate size between the ce ...

has a fairly small neural spine

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spinal ...

and short transverse processes

Each vertebra (: vertebrae) is an irregular bone with a complex structure composed of bone and some hyaline cartilage, that make up the vertebral column or spine, of vertebrates. The proportions of the vertebrae differ according to their spina ...

. Further back in the thoracic column, the vertebrae are much larger, and have bigger neural spines. The lumbar vertebrae

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe t ...

have wedge-shaped centra and weak, laterally-compressed neural spines, with thin transverse processes. Four vertebrae were present in the sacrum

The sacrum (: sacra or sacrums), in human anatomy, is a triangular bone at the base of the spine that forms by the fusing of the sacral vertebrae (S1S5) between ages 18 and 30.

The sacrum situates at the upper, back part of the pelvic cavity, ...

. Only four of ''Uintatherium''caudal

Caudal may refer to:

Anatomy

* Caudal (anatomical term) (from Latin ''cauda''; tail), used to describe how close something is to the trailing end of an organism

* Caudal artery, the portion of the dorsal aorta of a vertebrate that passes into th ...

(tail) vertebrae are known. They were bore long, narrow centra, decreasing in size the further they are posteriorly. Despite their relative slenderness, the caudal vertebrae are quite broad in comparison to those of proboscideans. The ribs of ''Uintatherium'' also resembled proboscideans, and have been compared to mastodons

A mastodon, from Ancient Greek μαστός (''mastós''), meaning "breast", and ὀδούς (''odoús'') "tooth", is a member of the genus ''Mammut'' (German for 'mammoth'), which was endemic to North America and lived from the late Miocene to ...

specifically, while the sternum

The sternum (: sternums or sterna) or breastbone is a long flat bone located in the central part of the chest. It connects to the ribs via cartilage and forms the front of the rib cage, thus helping to protect the heart, lungs, and major bl ...

more closely resembles certain artiodactyls

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other thre ...

.

Limbs

As with much of the postcranial skeleton, ''Uintatherium''scapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

(shoulder blade) of ''Uintatherium'' resembles that of proboscideans, though is less developed above the glenoid fossa

The glenoid fossa of the scapula or the glenoid cavity is a bone part of the shoulder. The word ''glenoid'' is pronounced or (both are common) and is from , "socket", reflecting the shoulder joint's ball-and-socket form. It is a shallow, pyrifo ...

. The humerus

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius (bone), radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extrem ...

is fairly short and massively built. Its great tuberosity is slightly compressed and does not extend above the humeral head

The humerus (; : humeri) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of ...

. The lower portion of the humerus resembles that of rhinocerotids. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius (: radii or radiuses) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its Centre (geometry), center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The radius of a regular polygon is th ...

and ulna

The ulna or ulnar bone (: ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone in the forearm stretching from the elbow to the wrist. It is on the same side of the forearm as the little finger, running parallel to the Radius (bone), radius, the forearm's other long ...

are essentially equal in size. The ulna has a small face where it articulates with the lunate

Lunate is a crescent or moon-shaped microlith. In the specialized terminology of lithic reduction, a lunate flake is a small, crescent-shaped lithic flake, flake removed from a stone tool during the process of pressure flaking.

In the Natufian cu ...

, again similar to proboscideans. Where ''Uintatherium''carpal

The carpal bones are the eight small bones that make up the wrist (carpus) that connects the hand to the forearm. The terms "carpus" and "carpal" are derived from the Latin carpus and the Greek καρπός (karpós), meaning "wrist". In huma ...

(wrist) bones, which interlock, similar to perissodactyls. ''Uintatherium''scaphoid bone

The scaphoid bone is one of the carpal bones of the wrist. It is situated between the hand and forearm on the thumb side of the wrist (also called the lateral or radial side). It forms the radial border of the carpal tunnel. The scaphoid b ...

is somewhat like elephants, though is shorter and stouter, and has a rounded proximal

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to describe unambiguously the anatomy of humans and other animals. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position prov ...

(near) end. The smallest bone of the carpus is the trapezoid

In geometry, a trapezoid () in North American English, or trapezium () in British English, is a quadrilateral that has at least one pair of parallel sides.

The parallel sides are called the ''bases'' of the trapezoid. The other two sides are ...

. Unlike elephants and proboscideans, the unciform bone articulates with both the cuneiform and lunar bones. The phalanges

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digit (anatomy), digital bones in the hands and foot, feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the Thumb, thumbs and Hallux, big toes have two phalanges while the other Digit (anatomy), digits have three phalanges. ...

(digit bones) are short, and grew increasingly rugose distally (away from the centre of the body). Overall, ''Uintatherium''manus

Manus may refer to:

Relating to locations around New Guinea

*Manus Island, a Papua New Guinean island in the Admiralty Archipelago

** Manus languages, languages spoken on Manus and islands close by

** Manus Regional Processing Centre, an offshore ...

anatomy somewhat resembled that of the pantodont ''Coryphodon

''Coryphodon'' (from Greek , "point", and , "tooth", meaning ''peaked tooth'', referring to "the development of the angles of the ridges into points

''. In life, it is likely that all four of ''Uintatherium''n the molars

N, or n, is the fourteenth letter of the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages, and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''en'' (pronounced ), plural ''ens''.

History

...

") is an extinct genus of pantodonts of the family Coryphodontidae.

''Coryphodo ...pelvis

The pelvis (: pelves or pelvises) is the lower part of an Anatomy, anatomical Trunk (anatomy), trunk, between the human abdomen, abdomen and the thighs (sometimes also called pelvic region), together with its embedded skeleton (sometimes also c ...

is very large, with a sub-oval outline, only superficially resembling that of proboscideans. Its width suggests that it supported a greatly enlarged hindgut

The hindgut (or epigaster) is the posterior ( caudal) part of the alimentary canal. In mammals, it includes the distal one third of the transverse colon and the splenic flexure, the descending colon, sigmoid colon and up to the ano-rectal junct ...

. The femur

The femur (; : femurs or femora ), or thigh bone is the only long bone, bone in the thigh — the region of the lower limb between the hip and the knee. In many quadrupeds, four-legged animals the femur is the upper bone of the hindleg.

The Femo ...

is fairly short, lacked a pit to accommodate the round ligament, and had a great trochanter

The greater trochanter of the femur is a large, irregular, quadrilateral eminence and a part of the skeletal system.

It is directed lateral and medially and slightly posterior. In the adult it is about 2–4 cm lower than the femoral head.Sta ...

which was flat and recurved. Distally, the femur was more strongly laterally compressed than in a proboscidean. It has femur condyles around the same size. In life, ''Uintatherium'' would have held its hind leg essentially straight, as in elephants and humans. The patella (kneecap) is oval-shaped. The fibula

The fibula (: fibulae or fibulas) or calf bone is a leg bone on the lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long bones. ...

is slender, with prominent articular faces for the elements of the tarsus (ankle and foot). The astragalus

Astragalus may refer to:

* ''Astragalus'' (plant), a large genus of herbs and small shrubs

*Astragalus (bone)

The talus (; Latin for ankle or ankle bone; : tali), talus bone, astragalus (), or ankle bone is one of the group of foot bones known ...

, or talus, is more like perissodactyls than proboscideans, in that its anterior portion has articular faces for both the cuboid

In geometry, a cuboid is a hexahedron with quadrilateral faces, meaning it is a polyhedron with six Face (geometry), faces; it has eight Vertex (geometry), vertices and twelve Edge (geometry), edges. A ''rectangular cuboid'' (sometimes also calle ...

and navicular bones. ''Uintatherium''Paleoecology

Diet and lifestyle

Like other uintatheriids, the molars of ''Uintatherium'' werebilophodont

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone toot ...

(two-ridged). Cheek teeth with this morphology often belong to browsing

Browsing is a kind of orienting strategy. It is supposed to identify something of relevance for the browsing organism. In context of humans, it is a metaphor taken from the animal kingdom. It is used, for example, about people browsing open sh ...

(feeding on leaves, shoots and twigs of relatively high-growing plants) animals. It has therefore been suggested that ''Uintatherium'' adopted a similar lifestyle. However, in 2002, Turnbull suggested that it, and other late-stage dinoceratans, were more ecologically analogous to hippopotamuses, citing traits such as pachyostosis, short legs, and a barrel-shaped ribcage as supporting evidence. As C4 grasses, on which hippopotamuses often feed, became widespread only fairly recently, and dinoceratan teeth were not suited for grazing, he noted that they likely fed quite differently to hippopotamuses. Whereas most modern ungulates ferment plant matter in their foregut

The foregut in humans is the anterior part of the alimentary canal, from the distal esophagus to the first half of the duodenum, at the entrance of the bile duct. Beyond the stomach, the foregut is attached to the abdominal walls by mesentery. ...

, Turnbull suggested based on pelvic anatomy that ''Uintatherium'' was instead a hindgut fermenter, similar to proboscideans and perissodactyls. He further proposed that late-stage dinoceratans had digestive systems analogous to sirenians

The Sirenia (), commonly referred to as sea cows or sirenians, are an order (biology), order of fully aquatic, herbivorous mammals that inhabit swamps, rivers, estuaries, marine wetlands, and coastal marine waters. The extant Sirenia comprise tw ...

(sea cows). If this model is accurate, the processing of food would have occurred primarily in the hindgut, reducing demands on the cheek teeth and resulting in the "inadequate appearance" observed by Wood.

Paleoenvironment

''Uintatherium'' evolved during a period in Earth's climatic history called the Paleocene-Eocene thermal maximum. This period saw some of the highest average temperatures in Earth's history with temperatures in Colorado (where ''Uintatherium'' fossils have been found) reaching an annual average of —much higher than today where the mean annual temperature in Colorado is only around . Although global average temperatures declined throughout the Eocene, the average temperatures in North America remained relatively consistent for the first half of the period, and only cooled slightly towards the end of the Eocene. North America did see considerable climatic developments dutring the course of the Eocene in spite of the relatively constant regional average temperatures. The uplifting of theRocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in great-circle distance, straight-line distance from the northernmost part of Western Can ...

and their associated volcanism lad to considerable drying in the North American interior. The arid scrublands which characterize the western United States today (as exemplified by Arizona

Arizona is a U.S. state, state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States, sharing the Four Corners region of the western United States with Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah. It also borders Nevada to the nort ...

, Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

, and New Mexico

New Mexico is a state in the Southwestern United States, Southwestern region of the United States. It is one of the Mountain States of the southern Rocky Mountains, sharing the Four Corners region with Utah, Colorado, and Arizona. It also ...

) began to emerge during this period.

When ''Uintatherium'' first appeared in North America, most of the continent was covered primarily closed-canopy forests. This environment is exemplified by the Bridger Formation

The Bridger Formation is a Formation (geology), geologic formation in southwestern Wyoming. It preserves fossils dating back to the Bridgerian and Uintan North American land mammal age, stages of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period. The formati ...

, which consisted of inland lakes surrounded by dense forests. This is inferred by the abundance of plant fossils and the presence of a great diversity of primate fossils, which are predominantly arboreal. Fossils of redwoods

Sequoioideae, commonly referred to as redwoods, is a subfamily of coniferous trees within the family Cupressaceae, that range in the northern hemisphere. It includes the largest and tallest trees in the world. The trees in the subfamily are a ...

, elm

Elms are deciduous and semi-deciduous trees comprising the genus ''Ulmus'' in the family Ulmaceae. They are distributed over most of the Northern Hemisphere, inhabiting the temperate and tropical- montane regions of North America and Eurasia, ...

s, and birch trees

A birch is a thin-leaved deciduous hardwood tree of the genus ''Betula'' (), in the family Betulaceae, which also includes alders, hazels, and hornbeams. It is closely related to the beech- oak family Fagaceae. The genus ''Betula'' contains ...

are known from throughout North America during this period, suggesting that the amount of precipitation did not vary considerably across latitudes. Most of North America was likely covered by temperate forest

A temperate forest is a forest found between the tropical and boreal regions, located in the temperate zone. It is the second largest terrestrial biome, covering 25% of the world's forest area, only behind the boreal forest, which covers about 3 ...

s and temperate rainforest

Temperate rainforests are rainforests with coniferous or Broad-leaved tree, broadleaf forests that occur in the temperate zone and receive heavy rain.

Temperate rainforests occur in oceanic moist regions around the world: the Pacific temperate ...

s. Even organisms more typically adapted to low-latitude environments, such as palm tree

The Arecaceae () is a family of perennial, flowering plants in the monocot order Arecales. Their growth form can be climbers, shrubs, tree-like and stemless plants, all commonly known as palms. Those having a tree-like form are colloquially c ...

s and crocodylia

Crocodilia () is an Order (biology), order of semiaquatic, predatory reptiles that are known as crocodilians. They first appeared during the Late Cretaceous and are the closest living relatives of birds. Crocodilians are a type of crocodylomorp ...

ns have fossils preserved as far North as Alaska

Alaska ( ) is a non-contiguous U.S. state on the northwest extremity of North America. Part of the Western United States region, it is one of the two non-contiguous U.S. states, alongside Hawaii. Alaska is also considered to be the north ...

and Ellesmere Island

Ellesmere Island (; ) is Canada's northernmost and List of Canadian islands by area, third largest island, and the List of islands by area, tenth largest in the world. It comprises an area of , slightly smaller than Great Britain, and the total ...

, exemplifying the extreme climatic conditions of the early and middle Eocene.

By the time of the Uinta Formation

The Uinta Formation is a geologic formation in northeastern Utah

Utah is a landlocked state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is one of the Four Corners states, sharing a border with Ariz ...

, the landscape had changed considerably. The large lakes emblematic of the earlier Eocene had shrunk, and the majority of deposition was the product of low-volume streams. Insectivorous

A robber fly eating a hoverfly

An insectivore is a carnivorous animal or plant which eats insects. An alternative term is entomophage, which can also refer to the human practice of eating insects.

The first vertebrate insectivores we ...

and frugivorous

A frugivore ( ) is an animal that thrives mostly on raw fruits or succulent fruit-like produce of plants such as roots, shoots, nuts and seeds. Approximately 20% of mammalian herbivores eat fruit. Frugivores are highly dependent on the abundance ...

mammals (especially primates) declined in diversity alongside a rise of folivorous

In zoology, a folivore is a herbivore that specializes in eating leaves. Mature leaves contain a high proportion of hard-to-digest cellulose, less energy than other types of foods, and often toxic compounds.Jones, S., Martin, R., & Pilbeam, D. (1 ...

artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s, which is interpreted as reflecting an increase in more open habitats resulting in a gradual decline in tree cover. Considerable forests existed, likely alongside the numerous waterways, but these were probably interspersed by open savannah environments. This trend towards aridifcation was facilitated by a general decline in the amount of precipitation in North America while average annual temperatures remained high. It would not be until the later parts of the Eocene that the global cooling began to affect North American ecosystems, by which point, ''Uintatherium'' was already extinct.

''U. inseparatus'' appeared in Asia during the middle part of the Eocene. Its fossils are known from the Lushi Basin in China, which consisted of large, deep lakes that preserve fossils of bivalve

Bivalvia () or bivalves, in previous centuries referred to as the Lamellibranchiata and Pelecypoda, is a class (biology), class of aquatic animal, aquatic molluscs (marine and freshwater) that have laterally compressed soft bodies enclosed b ...

s and gastropod

Gastropods (), commonly known as slugs and snails, belong to a large Taxonomy (biology), taxonomic class of invertebrates within the phylum Mollusca called Gastropoda ().

This class comprises snails and slugs from saltwater, freshwater, and fro ...

s. These lakes were surrounded by forests and swamps and were interspersed by semi-arid steppe

In physical geography, a steppe () is an ecoregion characterized by grassland plains without closed forests except near rivers and lakes.

Steppe biomes may include:

* the montane grasslands and shrublands biome

* the tropical and subtropica ...

. Variations in sea-levels and intermittent flooding at the time also produced brackish

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estuari ...

lakes and swamps. The inland lakes varied in size over the course of the middle Eocene before eventually disappearing completely and being replaced by rivers and floodplain

A floodplain or flood plain or bottomlands is an area of land adjacent to a river. Floodplains stretch from the banks of a river channel to the base of the enclosing valley, and experience flooding during periods of high Discharge (hydrolog ...

s.

Contemporary fauna

North America

''Uintatherium anceps'' is known from various

''Uintatherium anceps'' is known from various strata

In geology and related fields, a stratum (: strata) is a layer of Rock (geology), rock or sediment characterized by certain Lithology, lithologic properties or attributes that distinguish it from adjacent layers from which it is separated by v ...

from the Bridgerian

The Bridgerian North American Stage on the geologic timescale is the North American faunal stage according to the North American Land Mammal Ages chronology (NALMA), typically set from 50,300,000 to 46,200,000 years BP lasting .

It is usually c ...

and Uintan

The Uintan North American Stage is the North American faunal stage, typically set from 46,200,000 to 42,000,000 years before present lasting 4.2 million years. The Uintan Stage is a key part of the North American land mammal age, North American Lan ...

North American land mammal ages

The North American land mammal ages (NALMA) establishes a geologic timescale for North American fauna beginning during the Late Cretaceous and continuing through to the present. These periods are referred to as ages or intervals (or stages when ref ...

. This corresponds to the interval between 50.5 and 39.7 million years ago—a span of just over 10 million years within the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

. The oldest remains confidently assigned to this species are from the faunal zone "BR3" of the Bridger Formation

The Bridger Formation is a Formation (geology), geologic formation in southwestern Wyoming. It preserves fossils dating back to the Bridgerian and Uintan North American land mammal age, stages of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period. The formati ...

, which is at the end of the Bridgerian land mammal age.

In the Bridger Formation, ''U. anceps'' coexisted with a variety of primitive ungulate

Ungulates ( ) are members of the diverse clade Euungulata ("true ungulates"), which primarily consists of large mammals with Hoof, hooves. Once part of the clade "Ungulata" along with the clade Paenungulata, "Ungulata" has since been determined ...

s including helohyids, homacodontids, brontotheriids, amynodontids, and hyopsodontid

Hyopsodontidae is an extinct Family (biology), family of primitive mammals, initially assigned to the order Condylarthra, living from the Paleocene to the Eocene in North America and Eurasia. Condylarthra is now thought to be a wastebasket taxon ...

s. The environment was also host to some of the ancestors of modern perissodactyl

Perissodactyla (, ), or odd-toed ungulates, is an order of Ungulate, ungulates. The order includes about 17 living species divided into three Family (biology), families: Equidae (wild horse, horses, Asinus, asses, and zebras), Rhinocerotidae ( ...

groups including ''Hyrachyus

''Hyrachyus'' (from ''Hyrax'' and "pig") is an extinct genus of perissodactyl mammal that lived in Eocene Europe, North America, and Asia. Its remains have also been found in Jamaica. It is closely related to ''Lophiodon''.Hayden, F.V''Report of ...

'' (a primitive relative of rhinos), ''Helaletes

''Helaletes'' is a genus of an extinct perissodactyls closely related to tapirs. Fossils have been found in North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. N ...

'' (an early relative of tapirs), and several species of ''Orohippus

''Orohippus'' (from the Greek , 'mountain' and , 'horse') is an extinct equid that lived in the Eocene (about 50 million years ago). Its fossils have been unearthed in Oregon, Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming.

Description

It is believed to hav ...

'' (a primitive horse). North America at the time also had a diverse assemblage of early primates including '' Microsyops'', ''Notharctus

''Notharctus'' is a genus of Adapiformes, adapiform primate that lived in North America and Europe during the late to middle Eocene.

The body form of ''Notharctus'' is similar to that of modern rats. Its fingers were elongated for clamping onto ...

'', ''Smilodectes

''Smilodectes'' is a genus of Adapiformes, adapiform primate that lived in North America during the middle Eocene. It possesses a post-orbital bar and grasping thumbs and toes. ''Smilodectes'' has a small cranium size and the foramen magnum was l ...

'', and the members of Omomyidae

Omomyidae is a group of early primates that radiated during the Eocene epoch between about (mya). Fossil omomyids are found in North America, Europe & Asia, making it one of two groups of Eocene primates with a geographic distribution spanning ...

(relatives of modern tarsier

Tarsiers ( ) are haplorhine primates of the family Tarsiidae, which is the lone extant family within the infraorder Tarsiiformes. Although the group was prehistorically more globally widespread, all of the existing species are restricted to M ...

s). Mammalian predators of the region included mesonychid

Mesonychidae (meaning "middle claws") is an extinct family of small to large-sized omnivorous-carnivorous mammals. They were endemic to North America and Eurasia during the Early Paleocene to the Early Oligocene, and were the earliest group of la ...

s like ''Mesonyx

''Mesonyx'' ("middle claw") is a genus of extinct mesonychid mesonychian mammal. Fossils of the various species are found in Early to Late Eocene-age strata in the United States and Early Eocene-aged strata in China, 51.8—51.7 Ma ( AEO).

De ...

'' and ''Harpagolestes

''Harpagolestes'' ("hooked thief") is an extinct genus of hyena like, bear sized mesonychid mesonychian that lived in Central and Eastern Asia and western and central North America during the middle to late Eocene. It has been suggested that ''H ...

'', hyaenodontids like ''Limnocyon

''Limnocyon'' ("swamp dog") is an extinct paraphyletic genus of limnocyonin hyaenodonts that lived in North America during the middle Eocene. Fossils of this animal have been found in California, Utah and Wyoming

Wyoming ( ) is a landlo ...

'' and '' Sinopa'', oxyaenid