In

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

,

blasphemy

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

is impious utterance or action concerning

God

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

,

but is broader than in normal English usage, including not only the mocking or vilifying of attributes of Islam but denying any of the fundamental beliefs of the religion.

[ Examples include denying that the Quran was divinely revealed,][Lorenz Langer (2014) ''Religious Offence and Human Rights: The Implications of Defamation of Religions Cambridge University Press'' p. 332] insulting an angel

An angel is a spiritual (without a physical body), heavenly, or supernatural being, usually humanoid with bird-like wings, often depicted as a messenger or intermediary between God (the transcendent) and humanity (the profane) in variou ...

, or maintaining God had a son.[

The ]Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

curses those who commit blasphemy and promises blasphemers humiliation in the Hereafter

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's stream of consciousness or identity continues to exist after the death of their physical body. The surviving essential aspect varies bet ...

.[Siraj Khan]

"Blasphemy against the Prophet"

, in ''Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture'' (editors: Coeli Fitzpatrick and Adam Hani Walker). , pp. 59–61. However, whether any Quranic verses prescribe worldly punishments is debated: some Muslims believe that no worldly punishment is prescribed while others disagree.[Siraj Khan]

"Blasphemy against the Prophet"

, in ''Muhammad in History, Thought, and Culture'' (editors: Coeli Fitzpatrick and Adam Hani Walker). , pp. 59–67. The interpretation of hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

s, which are another source of Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

, is similarly debated.death

Death is the end of life; the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain a living organism. Death eventually and inevitably occurs in all organisms. The remains of a former organism normally begin to decompose sh ...

, while others argue that the death penalty applies only to cases where perpetrator commits treasonous crimes, especially during times of war. Different traditional schools of jurisprudence prescribe different punishment for blasphemy, depending on whether the blasphemer is Muslim or non-Muslim, a man or a woman.

In the modern Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

, the laws pertaining to blasphemy vary by country, and some countries prescribe punishments consisting of fines, imprisonment, flogging

Flagellation (Latin , 'whip'), flogging or whipping is the act of beating the human body with special implements such as whips, rods, switches, the cat o' nine tails, the sjambok, the knout, etc. Typically, flogging has been imposed ...

, hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

, or beheading.[P Smith (2003). "Speak No Evil: Apostasy, Blasphemy and Heresy in Malaysian Syariah Law". ''UC Davis Journal Int'l Law & Policy''. 10, pp. 357–73.

* N Swazo (2014). "The Case of Hamza Kashgari: Examining Apostasy, Heresy, and Blasphemy Under Sharia". ''The Review of Faith & International Affairs'' 12(4). pp. 16–26.] Capital punishment for blasphemy was rare in pre-modern Islamic societies. In the modern era some states and radical groups have used charges of blasphemy in an effort to burnish their religious credentials and gain popular support at the expense of liberal Muslim intellectuals and religious minorities.freedom of expression

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

.[ Contemporary accusations of blasphemy against Islam have sparked international controversies and incited mob violence and assassinations.

]

Islamic scripture

In Islamic literature, blasphemy is of many types, and there are many different words for it: (insult) and (abuse, vilification), or (denial), (concoction), or (curse) and (accuse, defame). In Islamic literature, the term "blasphemy" sometimes also overlaps with ("unbelief"), (depravity), (insult), and (apostasy).

Quran

A number of verses in the Qur'an have been interpreted as relating to blasphemy. In these verses God admonishes those who commit blasphemy. Some verses are cited as evidence that the Qur'an does not prescribe punishments for blasphemy,[ while other verses are cited as evidence that it does.

The only verse that directly says blasphemy (''sabb'') is Q6:108.]

Hadith

According to several hadiths, Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

ordered a number of enemies executed "in the hours after Mecca's fall". One of those who was killed was Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf

Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf (; died ) was, according to Islamic texts, a pre-Islamic Arabic poet and contemporary of Muhammad in Medina. Scholars identify him as a Jewish leader.

Biography

Ka'b was born to a father from the Arab Tayy tribe and a mother ...

, because he had insulted Muhammad.[Rubin, Uri. ''The Assassination of Kaʿb b. al-Ashraf.'' Oriens, Vol. 32. (1990), pp. 65–71.]

A variety of punishments, including death, have been instituted in Islamic jurisprudence that draw their sources from hadith literature.Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

ordered the execution of Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf

Ka'b ibn al-Ashraf (; died ) was, according to Islamic texts, a pre-Islamic Arabic poet and contemporary of Muhammad in Medina. Scholars identify him as a Jewish leader.

Biography

Ka'b was born to a father from the Arab Tayy tribe and a mother ...

.Battle of Badr

The Battle of Badr or sometimes called The Raid of Badr ( ; ''Ghazwahu Badr''), also referred to as The Day of the Criterion (, ; ''Yawm al-Furqan'') in the Qur'an and by Muslims, was fought on 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan, 2 AH), near the pre ...

, Ka'b had incited the Quraysh against Muhammad, and also urged them to seek vengeance against Muslims. Another person executed was Abu Rafi', who had actively propagandized against Muslims immediately before the Battle of Ahzab. Both of these men were guilty of insulting Muhammad, and both were guilty of inciting violence. While some have explained that these two men were executed for blaspheming against Muhammad, an alternative explanation is that they were executed for treason and causing disorder (''fasad

''Fasād'' ( ), or ''fasaad'', is an Arabic word meaning 'rottenness', 'corruption', or 'depravity'. In an Islamic context, it can refer to "spreading corruption on Earth" or "spreading mischief in a Muslim land", moral corruption against Allah ...

'') in society.[ One hadith]

Islamic law

Traditional jurisprudence

The Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

curses those who commit blasphemy and promises blasphemers humiliation in the Afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

.fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.[Fiqh](_blank)

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

) of Sunni and Shia madhab

A ''madhhab'' (, , pl. , ) refers to any school of thought within Islamic jurisprudence. The major Sunni ''madhhab'' are Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali.

They emerged in the ninth and tenth centuries CE and by the twelfth century almost all ...

s have declared different punishments for the religious crime of blasphemy, and they vary between schools. These are as follows:Hanafi

The Hanafi school or Hanafism is the oldest and largest Madhhab, school of Islamic jurisprudence out of the four schools within Sunni Islam. It developed from the teachings of the Faqīh, jurist and theologian Abu Hanifa (), who systemised the ...

– views blasphemy as synonymous with apostasy, and therefore, accepts the repentance of apostates. Those who refuse to repent, their punishment is death if the blasphemer is a Muslim man, and if the blasphemer is a woman, she must be imprisoned with coercion (beating) till she repents and returns to Islam. Imam Abu Hanifa

Abu Hanifa (; September 699 CE – 767 CE) was a Muslim scholar, jurist, theologian, ascetic,Pakatchi, Ahmad and Umar, Suheyl, "Abū Ḥanīfa", in: ''Encyclopaedia Islamica'', Editors-in-Chief: Wilferd Madelung and, Farhad Daftary. and epony ...

opined that a non-Muslim can not be killed for committing blasphemy. Other sources say his punishment must be a tazir

In Islamic Law, ''tazir'' (''ta'zeer'' or ''ta'zir'', ) lit. scolding; refers to punishment for offenses at the discretion of the judge (Qadi) or ruler of the state.[Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...]

– view blasphemy as an offense distinct from, and more severe than apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

. Death is mandatory in cases of blasphemy for Muslim men, and repentance is not accepted. For women, death is not the punishment suggested, but she is arrested and punished till she repents and returns to Islam or dies in custody. A non-Muslim who commits blasphemy against Islam must be punished; however, the blasphemer can escape punishment by converting and becoming a devout Muslim.

:Hanbali

The Hanbali school or Hanbalism is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence, belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It is named after and based on the teachings of the 9th-century scholar, jurist and tradit ...

– view blasphemy as an offense distinct from, and more severe than apostasy. Death is mandatory in cases of blasphemy, for both Muslim men and women.

:Shafi'i

The Shafi'i school or Shafi'i Madhhab () or Shafi'i is one of the four major schools of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It was founded by the Muslim scholar, jurist, and traditionis ...

– recognizes blasphemy as a separate offense from apostasy, but accepts the repentance of blasphemers. If the blasphemer does not repent, the punishment is death.Zahiri

The Zahiri school or Zahirism is a school of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was named after Dawud al-Zahiri and flourished in Spain during the Caliphate of Córdoba under the leadership of Ibn Hazm. It was also followed by the majo ...

– views insulting God or Islamic prophets as apostasy.

:Ja'fari

The Jaʿfarī school, also known as the Jafarite school, Jaʿfarī fiqh () or Ja'fari jurisprudence, is a prominent school of jurisprudence (''fiqh'') within Twelver and Ismaili (including Nizari) Shia Islam, named after the sixth Imam, Ja'far ...

(Shia) – views blasphemy against Islam, the Prophet, or any of the Imams, to be punishable with death, if the blasphemer is a Muslim. In case the blasphemer is a non-Muslim, he is given a chance to convert to Islam, or else killed.

Some jurists suggest that the sunnah in and provide a basis for a death sentence for the crime of blasphemy, even if someone claims not to be an apostate, but has committed the crime of blasphemy.blasphemy law

A blasphemy law is a law prohibiting blasphemy, which is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of Reverence (attitude), reverence to a deity, or sacred objects, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable. According to Pew Re ...

, stating that Muslim jurists

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

made the offense part of Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

.Ibn Abbas

ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbbās (; c. 619 – 687 CE), also known as Ibn ʿAbbās, was one of the cousins of the Prophets and messengers in Islam, prophet Muhammad. He is considered to be the greatest Tafsir#Conditions, mufassir of the Quran, Qur'an. ...

, a prominent jurist and companion of Muhammad, are frequently cited to justify the death penalty as punishment blasphemy:Hudud

''Hudud'' is an Arabic word meaning "borders, boundaries, limits".

The word is applied in classical Islamic literature to punishments (ranging from public lashing, public stoning to death, amputation of hands, crucifixion, depending on the c ...

and Taz'ir cover punishment for blasphemous acts.

Blasphemy as apostasy

Because blasphemy in Islam included rejection of fundamental doctrines,[ blasphemy has historically been seen as an evidence of rejection of Islam, that is, the religious crime of ]apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

. Some jurists believe that blasphemy by a Muslim who automatically implies the Muslim has left the fold of Islam. A Muslim may find himself accused of being a blasphemer, and thus an apostate on the basis of the same action or utterance.

Modern state laws

The punishments for different instances of blasphemy in Islam vary by jurisdiction,

The punishments for different instances of blasphemy in Islam vary by jurisdiction,[See ]Blasphemy law

A blasphemy law is a law prohibiting blasphemy, which is the act of insulting or showing contempt or lack of Reverence (attitude), reverence to a deity, or sacred objects, or toward something considered sacred or inviolable. According to Pew Re ...

. but may be very severe. A convicted blasphemer may, among other penalties, lose all legal rights. The loss of rights may cause a blasphemer's marriage to be dissolved, religious acts to be rendered worthless, and claims to property—including any inheritance—to be rendered void. Repentance, in some Fiqhs, may restore lost rights except for marital rights; lost marital rights are regained only by remarriage. Women have blasphemed and repented to end a marriage. Muslim women may be permitted to repent, and may receive a lesser punishment than would befall a Muslim man who committed the same offense.

History

Early and medieval Islam

According to Islamic sources Nadr ibn al-Harith

Al-Naḍr ibn al-Ḥārith ibn ʿAlqama ibn Kalada ibn ʿAbd Manāf ibn Abd al-Dār ibn Quṣayy (, d. 624 CE) was an Arab pagan physician who is considered one of the greatest Qurayshi opponents to the Islamic prophet Muhammad. He was captured a ...

, who was an Arab Pagan doctor from Taif, used to tell stories of Rustam and Isfandiyar to the Arabs and scoffed Muhammad. After the battle of Badr

The Battle of Badr or sometimes called The Raid of Badr ( ; ''Ghazwahu Badr''), also referred to as The Day of the Criterion (, ; ''Yawm al-Furqan'') in the Qur'an and by Muslims, was fought on 13 March 624 CE (17 Ramadan, 2 AH), near the pre ...

, al-Harith was captured and, in retaliation, Muhammad ordered his execution in hands of Ali

Ali ibn Abi Talib (; ) was the fourth Rashidun caliph who ruled from until his assassination in 661, as well as the first Shia Imam. He was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Born to Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib an ...

.Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

ordered a number of enemies executed. Based on this early jurists postulated that ''sabb al-Nabi'' (abuse of the Prophet) was a crime "so heinous that repentance was disallowed and summary execution

In civil and military jurisprudence, summary execution is the putting to death of a person accused of a crime without the benefit of a free and fair trial. The term results from the legal concept of summary justice to punish a summary offense, a ...

was required".Sadakat Kadri

Sadakat Kadri (born 1964 in London) is a lawyer, author, travel writer and journalist. One of his foremost roles as a barrister was to assist in the prosecution of former Malawian president Hastings Banda. As a member of the New York Bar he has ...

writes that the actual prosecutions for blasphemy in the Muslim historical record "are vanishingly infrequent". One of the "few known cases" was that of a Christian accused of insulting the Islamic Prophet Muhammad. It ended in an acquittal in 1293, though it was followed by a protest against a decision led by the famed and strict jurist Ibn Taymiyya

Ibn Taymiyya (; 22 January 1263 – 26 September 1328)Ibn Taymiyya, Taqi al-Din Ahmad, The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195125580.001.0001/acref-9780195125580-e-959 was a Sunni Muslim schola ...

.

In the 20th and 21st century

In recent decades Islamic revival

Islamic revival ('' '', lit., "regeneration, renewal"; also ', "Islamic awakening") refers to a revival of the Islamic religion, usually centered around enforcing sharia. A leader of a revival is known in Islam as a '' mujaddid''.

Within the Is ...

ists have called for its enforcement on the grounds that criminalizing hostility toward Islam will safeguard communal cohesion.[ In one country where strict laws on blaspheme were introduced in the 1980s, ]Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

, over 1300 people have been accused of blasphemy from 1987 to 2014, (mostly non-Muslim religious minorities), mostly for allegedly desecrating the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

.Salman Taseer

Salman Taseer (; 4 January 2011) was a Pakistani businessman and politician, who served as the 34th Governor of Punjab from 2008 until his assassination in 2011.

A member of the Pakistan Peoples Party since the 1980s, he was elected to the ...

, the former governor of Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

, and Shahbaz Bhatti

Clement Shahbaz Bhatti (9 September 19682 March 2011) was a Pakistani politician and the first Christian Federal Minister for Minorities Affairs. He was elected as a member of the National Assembly in 2008 for the Pakistan People's Party. Bhatt ...

, the Federal Minister for Minorities) have been assassinated.[

As of 2011, all Islamic majority nations, worldwide, had criminal laws on blasphemy. Over 125 non-Muslim nations worldwide did not have any laws relating to blasphemy. In Islamic nations, thousands of individuals have been arrested and punished for blasphemy of Islam. Moreover, several Islamic nations have argued in the United Nations that blasphemy against Muhammad is unacceptable, and that laws should be passed worldwide to proscribe it. In September 2012, the ]Organisation of Islamic Conference

The Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC; ; ), formerly the Organisation of the Islamic Conference, is an intergovernmental organisation founded in 1969. It consists of 57 member states, 48 of which are Muslim-majority. The Pew Forum on ...

(OIC), who has sought for a universal blasphemy law over a decade, revived these attempts. Separately, the Human Rights Commission of the OIC called for "an international code of conduct for media and social media to disallow the dissemination of incitement material". Non-Muslim nations that do not have blasphemy laws, have pointed to abuses of blasphemy laws in Islamic nations, and have disagreed.

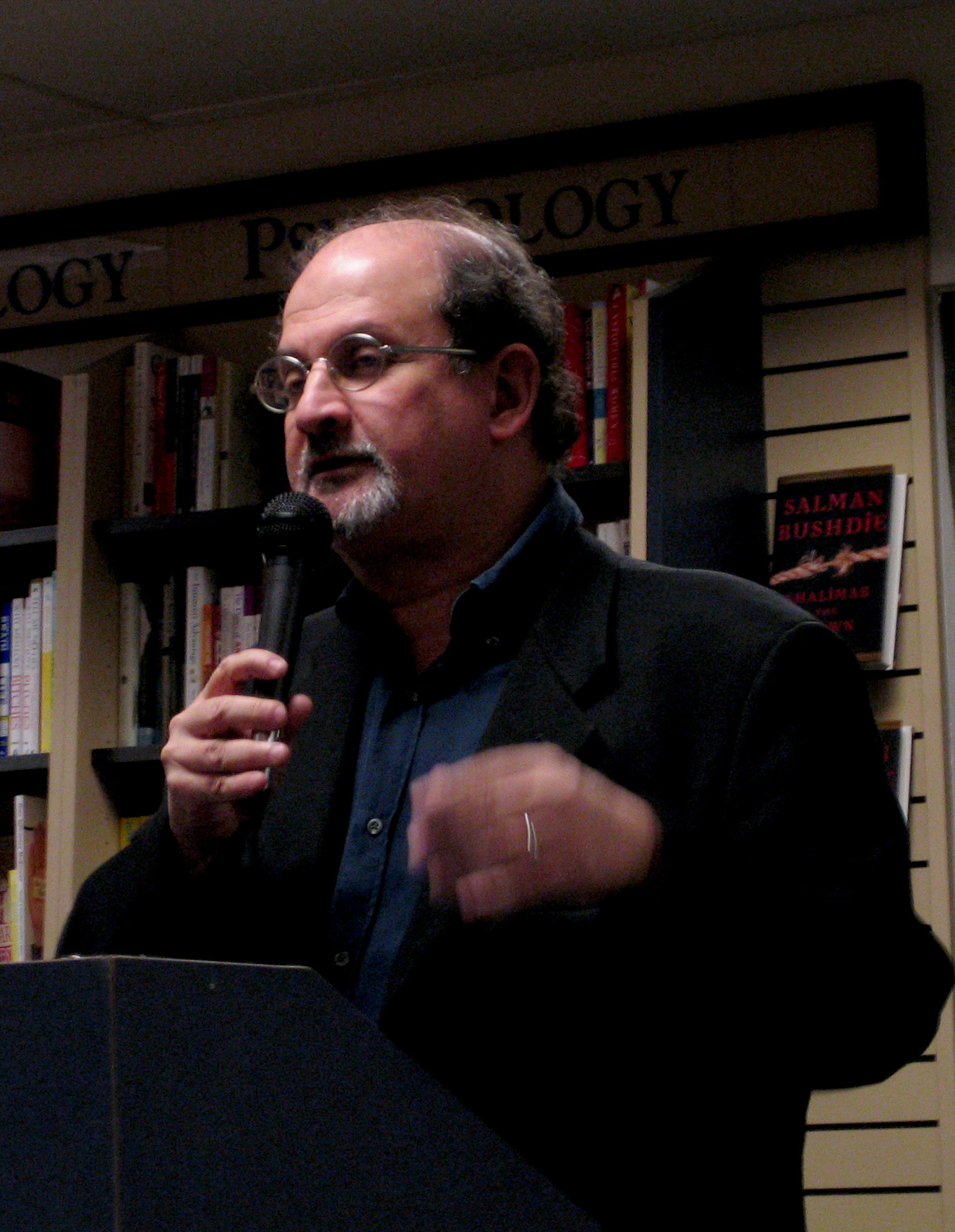

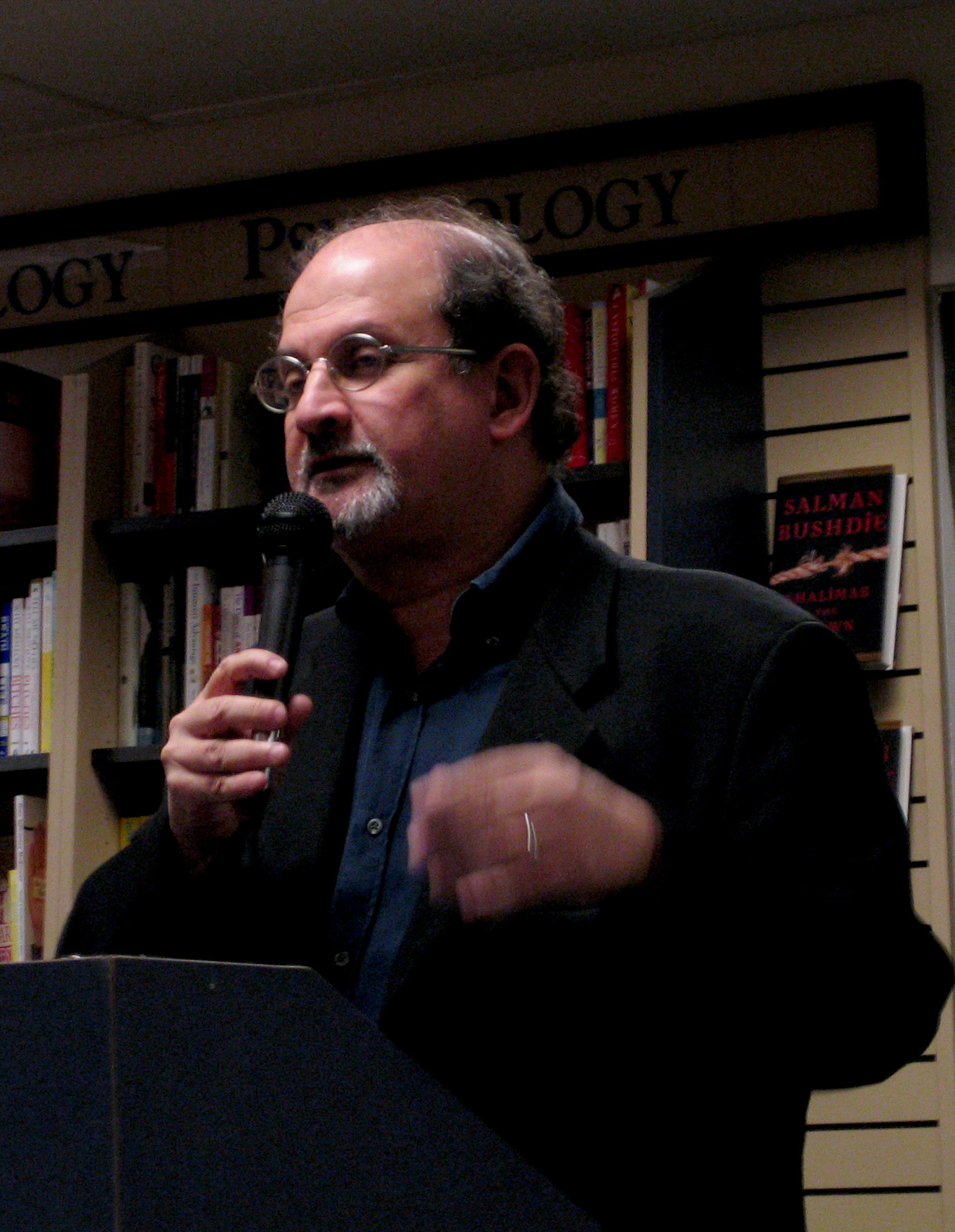

Notwithstanding, controversies raised in the non-Muslim world, especially over depictions of Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

, questioning issues relating to the religious offense

Religion is a range of social- cultural systems, including designated behaviors and practices, morals, beliefs, worldviews, texts, sanctified places, prophecies, ethics, or organizations, that generally relate humanity to supernatural, ...

to minorities in secular countries. A key case was the 1989 fatwa against English author Salman Rushdie

Sir Ahmed Salman Rushdie ( ; born 19 June 1947) is an Indian-born British and American novelist. His work often combines magic realism with historical fiction and primarily deals with connections, disruptions, and migrations between Eastern wor ...

for his 1988 book entitled ''The Satanic Verses

''The Satanic Verses'' is the fourth novel from the Indian-British writer Salman Rushdie. First published in September 1988, the book was inspired by the life of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. As with his previous books, Rushdie used magical re ...

'', the title of which refers to an account that Muhammad, in the course of revealing the Quran, received a revelation from Satan and incorporated it therein until made by Allah to retract it. Several translators of his book into foreign languages have been murdered.

Notable modern cases involving individuals

Assassination of Farag Foda

Farag Foda

Farag Foda ( ; 20 August 1945 – 8 June 1992) was a prominent Egyptian professor, writer, columnist, and human rights activist.

He was assassinated on 8 June 1992 by members of the Islamist group al-Jama'a al-Islamiyya after being accused of b ...

(also Faraj Fawda; 1946 – 9 June 1992), was a prominent Egyptian professor, writer, columnist,al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya

(, "Islamic Group") is an Egyptian Sunni Islamist movement, and is considered a terrorism, terrorist organization by the United Kingdom and the European Union, but was removed from the United States list of Foreign Terrorist Organizations i ...

after being accused of blasphemy by a committee of clerics (''ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

'') at Al-Azhar University

The Al-Azhar University ( ; , , ) is a public university in Cairo, Egypt. Associated with Al-Azhar Al-Sharif in Islamic Cairo, it is Egypt's oldest degree-granting university and is known as one of the most prestigious universities for Islamic ...

.Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

(Islamic law).

Imprisonment of Arifur Rahman

In September 2007, Bangladeshi cartoonist Arifur Rahman

Arifur Rahman (born August 8, 1984) is a Bangladeshis, Bangladeshi-Norwegians, Norwegian political cartoonist, illustrator and animator. He is a self-taught cartoonist who is renowned for his contribution to cartoons both on the internet and in ...

depicted in the daily ''Prothom Alo

''Prothom Alo'' () is a Bengali language, Bengali-language daily newspaper in Bangladesh, published from Dhaka. It is one of the largest circulated newspaper in Bangladesh. According to the National Media Survey of 2018, conducted by Kantar MRB ...

'' a boy holding a cat conversing with an elderly man. The man asks the boy his name, and he replies "Babu". The older man chides him for not mentioning the name of Muhammad before his name. He then points to the cat and asks the boy what it is called, and the boy replies "Muhammad the cat". Bangladesh does not have a blasphemy law but groups said the cartoon ridiculed Muhammad, torched copies of the paper and demanded that Rahman be executed for blasphemy. As a result, Bangladeshi police detained Rahman and confiscated copies of ''Prothom Alo'' in which the cartoon appeared.

Sudanese teddy bear blasphemy case

In November 2007, British schoolteacher Gillian Gibbons Gillian may refer to:

Places

* Gillian Settlement, Arkansas, an unincorporated community

People

Gillian (variant Jillian) is an English feminine given name, frequently shortened to Gill.

It originates as a feminine form of the name Julian, Julio, ...

, who taught middle-class Muslim and Christian children in Sudan,Friday prayers

Friday prayer, or congregational prayer (), is the meeting together of Muslims for communal prayer and service at midday every Friday. In Islam, the day itself is called ''Yawm al-Jum'ah'' (shortened to ''Jum'ah''), which translated from Arabic me ...

. Many Muslim organizations in other countries publicly condemned the Sudanese over their reactions as Gibbons did not set out to cause offence. She was released into the care of the British embassy in Khartoum and left Sudan after two British Muslim members of the House of Lords

The House of Lords is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Like the lower house, the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminster in London, England. One of the oldest ext ...

met President Omar al-Bashir

Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir (born 1 January 1944) is a Sudanese former military officer and politician who served as Head of state of Sudan, Sudan's head of state under various titles from 1989 until 2019, when he was deposed in 2019 Sudanese c ...

.

Asia Bibi blasphemy case

The Asia Bibi blasphemy case

In 2010, a Pakistani Christian woman, Aasiya Noreen (, ; born ), commonly known as Asia Bibi () or Aasia Bibi, was convicted of Islam and blasphemy, blasphemy by a Pakistani court and was sentenced to death by hanging.

In October 2018, the S ...

involved a Pakistani Christian woman, Aasiya Noreen (born 1971;hanging

Hanging is killing a person by suspending them from the neck with a noose or ligature strangulation, ligature. Hanging has been a standard method of capital punishment since the Middle Ages, and has been the primary execution method in numerou ...

in 2010. In June 2009, Noreen was involved in an argument with a group of Muslim women with whom she had been harvesting berries after the other women grew angry with her for drinking the same water as them. She was subsequently accused of insulting the Islamic Prophet

Prophets in Islam () are individuals in Islam who are believed to spread God's message on Earth and serve as models of ideal human behaviour. Some prophets are categorized as messengers (; sing. , ), those who transmit divine revelation, mos ...

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

, a charge she denied, and was arrested and imprisoned. In November 2010, a Sheikhupura

Sheikhupura (Punjabi language, Punjabi / ; ) also known as Qila Sheikhupura, is a city and district in the Pakistani province of Punjab, Pakistan, Punjab. Founded by the Mughal Empire, Mughal Emperor Jahangir in 1607, Sheikhupura is the List of ...

judge sentenced her to death. If executed, Noreen would have been the first woman in Pakistan to be lawfully killed for blasphemy.Pope Benedict XVI

Pope BenedictXVI (born Joseph Alois Ratzinger; 16 April 1927 – 31 December 2022) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 19 April 2005 until his resignation on 28 February 2013. Benedict's election as p ...

publicly called for the charges against her to be dismissed. She received less sympathy from her neighbors and Islamic religious leaders in the country, some of whom adamantly called for her to be executed. Christian minorities minister Shahbaz Bhatti

Clement Shahbaz Bhatti (9 September 19682 March 2011) was a Pakistani politician and the first Christian Federal Minister for Minorities Affairs. He was elected as a member of the National Assembly in 2008 for the Pakistan People's Party. Bhatt ...

and Muslim politician Salmaan Taseer were both assassinated for advocating on her behalf and opposing the blasphemy laws. Noreen's family went into hiding after receiving death threats, some of which threatened to kill Asia if released from prison.Shahbaz Bhatti

Clement Shahbaz Bhatti (9 September 19682 March 2011) was a Pakistani politician and the first Christian Federal Minister for Minorities Affairs. He was elected as a member of the National Assembly in 2008 for the Pakistan People's Party. Bhatt ...

both publicly supported Noreen, with the latter saying, "I will go to every knock for justice on her behalf and I will take all steps for her protection."[ She also received support from Pakistani political scientist Rasul Baksh Rais and local priest Samson Dilawar.]liberal Muslims

Liberal and progressive ideas within Islam is a range of interpretation of Islamic understanding and practice, ranging from centrist to left-wing perspectives. Some Muslims have created a considerable body of progressive interpretation of I ...

were also unnerved by her sentencing.Shahbaz Bhatti

Clement Shahbaz Bhatti (9 September 19682 March 2011) was a Pakistani politician and the first Christian Federal Minister for Minorities Affairs. He was elected as a member of the National Assembly in 2008 for the Pakistan People's Party. Bhatt ...

said that he was first threatened with death in June 2010 when he was told that he would be beheaded if he attempted to change the blasphemy laws. In response, he told reporters that he was "committed to the principle of justice for the people of Pakistan" and willing to die fighting for Noreen's release.[ On 2 March 2011, Bhatti was shot dead by gunmen who ambushed his car near his residence in Islamabad, presumably because of his position on the blasphemy laws. He had been the only Christian member of Pakistan's cabinet.][Sana Saleem]

"Salmaan Taseer: murder in an extremist climate"

, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

, 5 January 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011.[Aleem Maqbool and ]Orla Guerin

Orla Guerin Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire, MBE ( ; born 15 May 1966) is an Irish people, Irish journalist. She is a Senior International correspondent working for BBC News broadcasting around the world and across the U ...

"Salman Taseer: Thousands mourn Pakistan governor"

: "One small religious party, the Jamaat-e-Ahl-e-Sunnat Pakistan, warned that anyone who expressed grief over the assassination could suffer the same fate. 'No Muslim should attend the funeral or even try to pray for Salman Taseer or even express any kind of regret or sympathy over the incident,' the party said in a statement. It said anyone who expressed sympathy over the death of a blasphemer was also committing blasphemy." ''BBC News South Asia'', 5 January 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2011. Supporters of Mumtaz Qadri blocked police attempting to bring him to the courts and some showered him with rose petals.

Imprisonment of Fatima Naoot

In 2014, an Egyptian state prosecutor pressed charges against a former candidate for parliament, writer and poet Fatima Naoot, of blaspheming Islam when she posted a Facebook message which criticized the slaughter of animals during Eid al-Adha

Eid al-Adha () is the second of the two main festivals in Islam alongside Eid al-Fitr. It falls on the 10th of Dhu al-Hijja, the twelfth and final month of the Islamic calendar. Celebrations and observances are generally carried forward to the ...

, a major Islamic festival. Naoot was sentenced on 26 January 2016 to three years in prison for "contempt of religion." The prison sentence was effective immediately.

Murder of Farkhunda Malikzada

Farkhunda Malikzada was a 27-year-old Afghan

Afghan or Afgan may refer to:

Related to Afghanistan

*Afghans, historically refers to the Pashtun people. It is both an ethnicity and nationality. Ethnicity wise, it refers to the Pashtuns. In modern terms, it means both the citizens of Afghanist ...

woman who was publicly beaten and slain by a mob of hundreds of people in Kabul

Kabul is the capital and largest city of Afghanistan. Located in the eastern half of the country, it is also a municipality, forming part of the Kabul Province. The city is divided for administration into #Districts, 22 municipal districts. A ...

on 19 March 2015.mosque

A mosque ( ), also called a masjid ( ), is a place of worship for Muslims. The term usually refers to a covered building, but can be any place where Salah, Islamic prayers are performed; such as an outdoor courtyard.

Originally, mosques were si ...

where she worked as a religious teacher,[ about his practice of selling charms at the ]Shah-Do Shamshira Mosque

Shah-Do Shamshira Mosque (, ), (lit. Mosque of the King of Two Swords), is a yellow two-story mosque in Kabul, Afghanistan (District 2) on Andarabi Road, just off the Kabul River and the Shah-Do Shamshira bridge in the center of the city. It was ...

, the Shrine of the King of Two Swords,Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

turned to shock and anger.women's rights in Afghanistan

Women's rights in Afghanistan are severely restricted by the Taliban. In 2023, the United Nations termed Afghanistan as the world's most repressive country for women. Since the 2020–2021 U.S. troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, US troops with ...

.

Death sentence for Ahmad Al Shamri's atheism

Ahmad Al Shamri

Ahmad Al Shamri is an imprisoned Saudi dissident facing the death penalty for alleged apostasy and blasphemy. He was born in the city of Hafar al-Batin, Saudi Arabia. His case was first brought to religious authorities in 2014 after he allegedly ...

from the town of Hafar al-Batin

Hafar al-Batin ( '), also frequently spelled ''Hafr al-Batin'', is a city in the Hafar al-Batin Governorate, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia, Eastern Province, Saudi Arabia. It is located 430 km north of Riyadh, 94.2 km from the Kuwait b ...

, Saudi Arabia, was arrested on charges of atheism and blasphemy after allegedly use social media to state that he renounced Islam and the Prophet Mohammed, he was sentenced to death in February 2015.

Death of Mashal Khan

Mashal Khan was a Pakistani student at the Abdul Wali Khan University Mardan who was killed by an angry mob in the premises of the university in April 2017 over allegations of posting blasphemous content online.

Imprisonment of the governor of Jakarta

In 2017 in Indonesia, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama

Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (, Pha̍k-fa-sṳ: ''Chûng Van-ho̍k''; born 29 June 1966) is an Indonesian businessman, politician, and former governor of Jakarta. He is colloquially known by his Hakka Chinese name, Ahok (). He was the first ethnic C ...

during his tenure as the governor of Jakarta

Jakarta (; , Betawi language, Betawi: ''Jakartè''), officially the Special Capital Region of Jakarta (; ''DKI Jakarta'') and formerly known as Batavia, Dutch East Indies, Batavia until 1949, is the capital and largest city of Indonesia and ...

, made a controversial speech while introducing a government project at Thousand Islands

The Thousand Islands (, ) constitute a North American archipelago of 1,864 islands that straddles the Canada–US border in the Saint Lawrence River as it emerges from the northeast corner of Lake Ontario. They stretch for about downstream fr ...

in which he referenced a verse from the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

. His opponents criticized this speech as blasphemous

Blasphemy refers to an insult that shows contempt, disrespect or lack of Reverence (emotion), reverence concerning a deity, an object considered sacred, or something considered Sanctity of life, inviolable. Some religions, especially Abrahamic o ...

, and reported him to the police. He was later convicted of blasphemy against Islam by the North Jakarta District Court and sentenced to two years imprisonment.

Notable international controversies

Protests against depicting Muhammad

In December 1999, the German news magazine ''

In December 1999, the German news magazine ''Der Spiegel

(, , stylized in all caps) is a German weekly news magazine published in Hamburg. With a weekly circulation of about 724,000 copies in 2022, it is one of the largest such publications in Europe. It was founded in 1947 by John Seymour Chaloner ...

'' printed on the same page pictures of "moral apostles" Muhammad, Jesus

Jesus (AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ, Jesus of Nazareth, and many Names and titles of Jesus in the New Testament, other names and titles, was a 1st-century Jewish preacher and religious leader. He is the Jesus in Chris ...

, Confucius

Confucius (; pinyin: ; ; ), born Kong Qiu (), was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Much of the shared cultural heritage of the Sinosphere originates in the phil ...

, and Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (born Emanuel Kant; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German Philosophy, philosopher and one of the central Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works ...

. Few weeks later, the magazine received protests, petitions and threats against publishing depictions of Muhammad

The permissibility of depictions of Muhammad in Islam has been a contentious issue. Oral and written descriptions of Muhammad are readily accepted by all traditions of Islam, but there is disagreement about visual depictions. The Quran does no ...

. The Turkish TV station Show TV

Show TV is a Turkish free-to-air national television channel, established in 1991 by Erol Aksoy, Dinç Bilgin, Haldun Simavi and Erol Simavi, owned by the Can Holding.

History

The channel replaces Cine5's now-defunct frequencies, and it was ...

broadcast the telephone number of an editor who then received daily calls. A picture of Muhammad had been published by the magazine once before in 1998 in a special edition on Islam, without evoking similar protests.

In 2008, several Muslims protested against the inclusion of Muhammad's depictions in the English Wikipedia

The English Wikipedia is the primary English-language edition of Wikipedia, an online encyclopedia. It was created by Jimmy Wales and Larry Sanger on 15 January 2001, as Wikipedia's first edition.

English Wikipedia is hosted alongside o ...

's ''Muhammad'' article.online petition

An online petition (or Internet petition, or e-petition) is a form of petition which is signed online, usually through a form on a website. Visitors to the online petition sign the petition by adding their details such as name and email address. T ...

opposed a reproduction of a 17th-century Ottoman copy of a 14th-century Ilkhanate

The Ilkhanate or Il-khanate was a Mongol khanate founded in the southwestern territories of the Mongol Empire. It was ruled by the Il-Khans or Ilkhanids (), and known to the Mongols as ''Hülegü Ulus'' (). The Ilkhanid realm was officially known ...

manuscript image depicting Muhammad as he prohibited Nasīʾ. Jeremy Henzell-Thomas of ''The American Muslim'' deplored the petition as one of "these mechanical knee-jerk reactions hich

Ij () is a village in Golabar Rural District of the Central District in Ijrud County, Zanjan province, Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran (IRI) and also known as Persia, is a country in West Asia. It borders Iraq ...

are gifts to those who seek every opportunity to decry Islam and ridicule Muslims and can only exacerbate a situation in which Muslims and the Western media seem to be locked in an ever-descending spiral of ignorance and mutual loathing."

The Muhammad cartoons crisis

In September 2005, in the tense aftermath of the assassination of Dutch film director Theo van Gogh, killed for his views on Islam, Danish news service Ritzau

Ritzaus Bureau A/S, or Ritzau for short, sometimes stylized as /ritzau/, is a Denmark, Danish news agency founded by Erik Ritzau in 1866. It collaborates with three other Scandinavian news agencies to provide Nordic News, an English-language Scan ...

published an article discussing the difficulty encountered by the writer Kåre Bluitgen

Kåre Bluitgen (10 May 1959) is a Danish writer and journalist whose works include a biography of Muhammad. In the 1970s Bluitgen was politically active on the Danish left, namely within the Left Socialists.

Education and career

Kåre Bluitgen r ...

to find an illustrator to work on his children's book ''The Qur'an and the life of the Prophet Muhammad'' (Danish: ''Koranen og profeten Muhammeds liv'').Flemming Rose

Flemming Rose (born 11 March 1958) is a Danish journalist, author and Senior Fellow at the Cato Institute. He previously served as foreign affairs editor at the Danish newspaper ''Jyllands-Posten''. As culture editor of the same newspaper, he was ...

, an editor at the Danish newspaper ''Jyllands-Posten

(; English: ''The Morning Newspaper "The Jutland Post"''), commonly shortened to or ''JP'', is a Danish daily broadsheet newspaper. It is based in Aarhus C, Jutland, and with a weekday circulation of approximately 120,000 copies.[criticism of Islam

Criticism of Islam can take many forms, including academic critiques, political criticism, religious criticism, and personal opinions. Subjects of criticism include Islamic beliefs, practices, and doctrines.

Criticism of Islam has been present ...]

and self-censorship. On 30 September 2005, the ''Jyllands-Posten'' published 12 editorial cartoons, most of which depicted the Prophet Muhammad. One cartoon by Kurt Westergaard

Kurt Westergaard (born Kurt Vestergaard; 13 July 1935 – 14 July 2021) was a Danish cartoonist. In 2005 he drew a cartoon of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, wearing a bomb in his turban as a part of the ''Jyllands-Posten'' Muhammad cartoons, whic ...

depicted Muhammad with a bomb in his turban, which resulted in the ''Jyllands-Posten'' Muhammad cartoons controversy (or Muhammad cartoons crisis) (Danish: ''Muhammedkrisen'') i.e. complains by Muslim groups in Denmark

Denmark is a Nordic countries, Nordic country in Northern Europe. It is the metropole and most populous constituent of the Kingdom of Denmark,, . also known as the Danish Realm, a constitutionally unitary state that includes the Autonomous a ...

, the withdrawal of the ambassadors of Libya, Saudi Arabia and Syria from Denmark, protests around the world including violent demonstrations and riots in some Muslim countries

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is p ...

as well as consumer boycotts of Danish products. Carsten Juste, editor-in-chief at the ''Jyllands-Posten'', claimed the international furor over the cartoons amounted to a victory for opponents of free expression. "Those who have won are dictatorships in the Middle East, in Saudi Arabia, where they cut criminals' hands and give women no rights," Juste told The Associated Press. "The dark dictatorships have won." Commenting the cartoon that initiated the diplomatic crisis, American scholar John Woods expressed worries about Westergaard-like association of the Prophet with terrorism, that was beyond satire and offensive to a vast majority of Muslims.[

In Sweden, an online caricature competition was announced in support of ''JyllandsPosten'', but foreign minister Laila Freivalds pressured the provider to shut the page down (in 2006, her involvement was revealed to the public and she had to resign).

] In France, satirical magazine ''

In France, satirical magazine ''Charlie Hebdo

''Charlie Hebdo'' (; ) is a French satirical weekly magazine, featuring cartoons, reports, polemics, and jokes. The publication has been described as anti-racist, sceptical, secular, libertarian, and within the tradition of left-wing radicalism ...

'' republished the ''Jyllands-Posten'' cartoons of Muhammad. It was taken to court by Islamic organisations under French hate speech laws; it was ultimately acquitted of charges that it incited hatred.Lars Vilks

Lars Endel Roger Vilks (20 June 1946 – 3 October 2021) was a Swedish visual artist and activist who was known for Lars Vilks Muhammad drawings controversy, the controversy surrounding his drawings of Muhammad. Many years earlier he had created ...

depicting Muhammad as a roundabout dog

A roundabout dog () is a form of street installation that began in Sweden during the autumn of 2006 and continued for the rest of the year. There have been sporadic subsequent recurrences. The phenomenon consists of anonymous people placing home ...

. While Swedish newspapers had published them already, the drawings gained international attention after the newspaper '' Nerikes Allehanda'' published one of them on 18 August to illustrate an editorial on the "right to ridicule a religion".

English translation: [ ] and by the intergovernmental Organisation of the Islamic Conference. In 2006, the American comedy program ''

In 2006, the American comedy program ''South Park

''South Park'' is an American animated sitcom created by Trey Parker and Matt Stone, and developed by Brian Graden for Comedy Central. The series revolves around four boysStan Marsh, Kyle Broflovski, Eric Cartman, and Kenny McCormickand the ...

'', which had previously depicted Muhammad as a superhero (" Super Best Friends)" and has depicted Muhammad in the opening sequence since then, attempted to satirize the Danish newspaper incident. They intended to show Muhammad handing a salmon helmet to ''Family Guy

''Family Guy'' is an American animated sitcom created by Seth MacFarlane for the Fox Broadcasting Company. The series premiered on January 31, 1999, following Super Bowl XXXIII, with the rest of the first season airing from April 11, 1999. Th ...

'' character Peter Griffin

Peter Löwenbräu Griffin Sr. ( né Justin Peter Griffin) is a fictional character and the protagonist of the American animated sitcom ''Family Guy''. He is voiced by the series' creator, Seth MacFarlane, and first appeared on television, a ...

(" Cartoon Wars Part II"). However, Comedy Central

Comedy Central is an American Cable television in the United States, cable television channel, channel owned by Paramount Global through its Paramount Media Networks, network division's Paramount Media Networks#MTV Entertainment Group, MTV Ente ...

who airs the series rejected the scene and its creators reacted by satirizing double standard

A double standard is the application of different sets of principles for situations that are, in principle, the same. It is often used to describe treatment whereby one group is given more latitude than another. A double standard arises when two ...

for broadcast acceptability.

In April 2010, animators Trey Parker

Randolph Severn "Trey" Parker III (born October 19, 1969) is an American actor, animator, writer, producer, director, and musician. He is best known for co-creating ''South Park'' (1997) and '' The Book of Mormon'' (2011) with his creative part ...

and Matt Stone

Matthew Richard Stone (born May 26, 1971) is an American actor, animator, writer, producer, and musician. He is best known for co-creating ''South Park'' (since 1997) and ''The Book of Mormon (musical), The Book of Mormon'' (2011) with his cre ...

planned to make episodes satirizing controversies over previous episodes, including Comedy Central's refusal to show images of Muhammad following the 2005 Danish controversy. After they faced Internet death threats, Comedy Central modified their version of the episode, obscuring all images and bleeping all references to Muhammad. In reaction, cartoonist Molly Norris created the Everybody Draw Mohammed Day

Everybody Draw Mohammed Day (or Draw Mohammed Day) was a 2010 event in support of artists threatened with violence for drawing representations of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It stemmed from a protest against censorship of the American telev ...

, claiming that if many people draw pictures of Muhammad, threats to murder them all would become unrealistic.

On 2 November 2011, ''Charlie Hebdo'' was firebombed right before its 3 November issue was due; the issue was called ''Charia Hebdo

''Charlie Hebdo'' issue 1011 is an issue of the French satirical newspaper ''Charlie Hebdo'' published on 2 November 2011. Several attacks against ''Charlie Hebdo'', including an arson attack at its headquarters, were motivated by ...

'' and satirically featured Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

as guesteditor. The editor, Stéphane Charbonnier

Stéphane Jean-Abel Michel Charbonnier (; 21 August 1967 – 7 January 2015), better known as Charb (), was a French Satire, satirical Caricature, caricaturist and journalist. He was assassinated during the Charlie Hebdo shooting, ''Charlie ...

, known as Charb, and two co-workers at ''Charlie Hebdo'' subsequently received police protection. In September 2012, the newspaper published a series of satirical cartoons of Muhammad, some of which feature nude caricatures of him. In January 2013, ''Charlie Hebdo'' announced that they would make a comic book

A comic book, comic-magazine, or simply comic is a publication that consists of comics art in the form of sequential juxtaposed panel (comics), panels that represent individual scenes. Panels are often accompanied by descriptive prose and wri ...

on the life of Muhammad.

In March 2013, Al-Qaeda's branch in Yemen, commonly known as Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula ( or : Tanẓīm Qā‘idat al-Jihād fī Jazīrat al-‘Arab, . Organization of Jihad's Base in the Arabian Peninsula), or AQAP is a Sunni Islam, Sunni Islamic extremism, Islamist militant organization which s ...

(AQAP), released a hit list in an edition of their English-language magazine ''Inspire

Inspiration, inspire, INSPIRE, or inspired commonly refers to:

* Artistic inspiration, sudden creativity in artistic production

* Biblical inspiration, a Christian doctrine on the origin of the Bible

* Inhalation, breathing in

Inspiration and rel ...

''. The list included Kurt Westergaard, Lars Vilks, Carsten Juste, Flemming Rose, Charb and Molly Norris, and others whom AQAP accused of insulting Islam. On 7 January 2015, two masked gunmen opened fire on Charlie Hebdo

''Charlie Hebdo'' (; ) is a French satirical weekly magazine, featuring cartoons, reports, polemics, and jokes. The publication has been described as anti-racist, sceptical, secular, libertarian, and within the tradition of left-wing radicalism ...

staff and police officers as vengeance for its continued caricatures of Muhammad,[Kim Willsher et al. (7 January 2015]

Paris terror attack: huge manhunt under way after gunmen kill 12

''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in Manchester in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'' and changed its name in 1959, followed by a move to London. Along with its sister paper, ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardi ...

''

Kamlesh Tiwari case

In October 2019, Kamlesh Tiwari, an Indian politician, was killed in a planned attack in Lucknow

Lucknow () is the List of state and union territory capitals in India, capital and the largest city of the List of state and union territory capitals in India, Indian state of Uttar Pradesh and it is the administrative headquarters of the epon ...

, Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh ( ; UP) is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. With over 241 million inhabitants, it is the List of states and union territories of India by population, most populated state in In ...

, for his views on Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

.Samajwadi Party

The Samajwadi Party ( SP; ) is a Socialism, socialist political party in India. It was founded on 4 October 1992 by former Janata Dal politician Mulayam Singh Yadav and is headquartered in New Delhi. It is the third-largest political party in ...

, stated that Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS,, ) is an Indian right-wing politics, right-wing, Hindutva, Hindu nationalist volunteer paramilitary organisation. It is the progenitor and leader of a large body of organisations called the Sangh Parivar ( ...

members are homosexuals and that is why they do not get married.[ Thousands of Muslims protested in Muzaffarnagar and demanded the death penalty for Tiwari,][ with some demanding that he be "beheaded" for "insulting" Muhammad.][ Tiwari was arrested in Lucknow on 3 December 2015 by Uttar Pradesh Police.][Who was Kamlesh Tiwari, the Hindu Samaj Party leader killed in broad daylight in Lucknow?]

, India Today (October 18, 2019) He was detained under National Security Act by the Samajwadi Party

The Samajwadi Party ( SP; ) is a Socialism, socialist political party in India. It was founded on 4 October 1992 by former Janata Dal politician Mulayam Singh Yadav and is headquartered in New Delhi. It is the third-largest political party in ...

–led state government in Uttar Pradesh

Uttar Pradesh ( ; UP) is a States and union territories of India, state in North India, northern India. With over 241 million inhabitants, it is the List of states and union territories of India by population, most populated state in In ...

.[Kamlesh Tiwari may contest U.P. bypolls]

, Mohammad Ali, The Hindu (September 20, 2016), Quote: "Mr. Tiwari, who was granted bail last week by a Lucknow court, will remain in jail until the Allahabad High Court decides on his plea against the slapping of the National Security Act (NSA) on him by the State government." Tiwari spent several months in jail for his comment. He was charged under Indian Penal Code sections 153-A (promoting enmity between groups on the grounds of religion and doing acts prejudicial to maintenance of harmony) and 295-A (deliberate and malicious acts, intended to outrage religious feelings of any class by insulting its religion or religious beliefs). Protest rallies against his statement were held by several Islamic groups in other parts of India, most of them demanding the death penalty.

The protests demanding capital punishment for Tiwari triggered counter-protests by Hindu groups who accused Muslim groups of demanding enforcement of Islamic law

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' refers to immutable, intan ...

of blasphemy in India.[ His detention under National Security Act was revoked by ]Allahabad High Court

Allahabad High Court, officially known as High Court of Judicature at Allahabad, is the high court based in the city of Prayagraj, formerly known as Allahabad, that has jurisdiction over the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh. It was established o ...

in 2016.

On 18 October 2019, Tiwari was murdered by two Muslim assailants, Farid-ud-din Shaikh and Ashfak Shaikh, in his office-cum-residence at Lucknow. The assailants came dressed in saffron kurta

A ''kurta'' is a loose collarless shirt or tunic worn in many regions of South Asia, (subscription required) Quote: "A loose shirt or tunic worn by men and women." Quote: "Kurta: a loose shirt without a collar, worn by women and men from South ...

s to give him a sweets box with an address of a sweet shop in Surat

Surat (Gujarati Language, Gujarati: ) is a city in the western Indian States and territories of India, state of Gujarat. The word Surat directly translates to ''face'' in Urdu, Gujarati language, Gujarati and Hindi. Located on the banks of t ...

city in Gujarat

Gujarat () is a States of India, state along the Western India, western coast of India. Its coastline of about is the longest in the country, most of which lies on the Kathiawar peninsula. Gujarat is the List of states and union territories ...

.

''Innocence of Muslims''

''Innocence of Muslims

''Innocence of Muslims'' is a 2012 anti-Islamic short film that was written and produced by Nakoula Basseley Nakoula. Two versions of the 14-minute video were uploaded to YouTube in July 2012, under the titles "The Real Life of Muhammad" and "M ...

'' is an anti-Islamic short film that was written and produced by Nakoula Basseley Nakoula

Mark Basseley Youssef (, born 1957), formerly known as Nakoula Basseley Nakoula (), is an Egyptian Americans, Egyptian-American writer, producer, and promoter of ''Innocence of Muslims'', a film which was Criticisms of Islam, critical of Islam a ...

.YouTube

YouTube is an American social media and online video sharing platform owned by Google. YouTube was founded on February 14, 2005, by Steve Chen, Chad Hurley, and Jawed Karim who were three former employees of PayPal. Headquartered in ...

in July 2012, under the titles ''The Real Life of Muhammad'' and ''Muhammad Movie Trailer''.Arabic

Arabic (, , or , ) is a Central Semitic languages, Central Semitic language of the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family spoken primarily in the Arab world. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) assigns lang ...

were uploaded during early September 2012.post-production

Post-production, also known simply as post, is part of the process of filmmaking, video production, audio production, and photography. Post-production includes all stages of production occurring after principal photography or recording indivi ...

by dubbing, without the actors' knowledge.

What was perceived as denigrating of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

resulted in demonstrations and violent protests against the video to break out on 11 September in Egypt and spread to other Arab and Muslim nations and to some western countries. The protests have led to hundreds of injuries and over 50 deaths. Fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

s calling for the harm of the video's participants have been issued and Pakistani government minister Bashir Ahmad Bilour

Bashir Ahmad Bilour (; 1 August 1943 – 22 December 2012) was a Pakistan, Pakistani member of the Provincial Assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, provincial assembly of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa and Senior Minister for Local Government ...

offered a bounty for the killing of Nakoula, the producer. The film has sparked debates about freedom of speech

Freedom of speech is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or a community to articulate their opinions and ideas without fear of retaliation, censorship, or legal sanction. The rights, right to freedom of expression has been r ...

and Internet censorship

Internet censorship is the legal control or suppression of what can be accessed, published, or viewed on the Internet. Censorship is most often applied to specific internet domains (such as ''Wikipedia.org'', for example) but exceptionally may ...

.

Blasphemy in Sweden during Turkish-Sweden tensions

The incident happened amid rising diplomatic tension between the two countries and Turkey's objections to Sweden joining NATO. Turkey had earlier canceled a visit by Sweden's defense minister and is seeking political concessions, including the deportation of critics and Kurds. The act was described by Sweden's Foreign Minister as "appalling" and does not imply government support for the opinion expressed.

Examples

A variety of actions, speeches or behavior can constitute blasphemy in Islam. Some examples include insulting or cursing Allah, or Muhammad; mockery or disagreeable behavior towards beliefs and customs common in Islam; criticism of Islam's holy personages.

A variety of actions, speeches or behavior can constitute blasphemy in Islam. Some examples include insulting or cursing Allah, or Muhammad; mockery or disagreeable behavior towards beliefs and customs common in Islam; criticism of Islam's holy personages. Apostasy

Apostasy (; ) is the formal religious disaffiliation, disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that is contrary to one's previous re ...

, that is, the act of abandoning Islam, or finding faults or expressing doubts about Allah (''ta'til'') and Qur'an, rejection of Muhammed or any of his teachings, or leaving the Muslim community to become an atheist is a form of blasphemy. Questioning religious opinions (fatwa) and normative Islamic views can also be construed as blasphemous. Improper dress, drawing offensive cartoons, tearing or burning holy literature of Islam, creating or using music or painting or video or novels to mock or criticize Muhammad are some examples of blasphemous acts. In the context of those who are non-Muslims, the concept of blasphemy includes all aspects of infidel

An infidel (literally "unfaithful") is a person who is accused of disbelief in the central tenets of one's own religion, such as members of another religion, or irreligious people.

Infidel is an ecclesiastical term in Christianity around which th ...

ity (kufr).

Individuals have been accused of blasphemy or of insulting Islam for a variety of actions and words.

Blasphemy against holy personages

* speaking ill of Allah.

* finding fault with Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

.Prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

who is mentioned in the Qur'an, or slighting a member of Muhammad's family.

Blasphemy against beliefs and customs

* finding fault with Islam.Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

is full of lies (Indonesia).

* believing in transmigration of the soul or reincarnation

Reincarnation, also known as rebirth or transmigration, is the Philosophy, philosophical or Religion, religious concept that the non-physical essence of a living being begins a new lifespan (disambiguation), lifespan in a different physical ...

or disbelieving in the afterlife

The afterlife or life after death is a purported existence in which the essential part of an individual's Stream of consciousness (psychology), stream of consciousness or Personal identity, identity continues to exist after the death of their ...

(Indonesia).

* expressing an atheist or a secular point of viewyoga

Yoga (UK: , US: ; 'yoga' ; ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines that originated with its own philosophy in ancient India, aimed at controlling body and mind to attain various salvation goals, as pra ...

(Malaysia).Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

or of Zoroastrians.

Blasphemy against mosques

See also

; Islam

; Secular topics

References

Further reading

*

*

{{DEFAULTSORT:Islam And Blasphemy

Islamic jurisprudence

Blasphemy

Islam-related controversies

fr:Blasphème#Islam

In

In  In December 1999, the German news magazine ''

In December 1999, the German news magazine '' In France, satirical magazine ''

In France, satirical magazine '' In 2006, the American comedy program ''

In 2006, the American comedy program '' A variety of actions, speeches or behavior can constitute blasphemy in Islam. Some examples include insulting or cursing Allah, or Muhammad; mockery or disagreeable behavior towards beliefs and customs common in Islam; criticism of Islam's holy personages.

A variety of actions, speeches or behavior can constitute blasphemy in Islam. Some examples include insulting or cursing Allah, or Muhammad; mockery or disagreeable behavior towards beliefs and customs common in Islam; criticism of Islam's holy personages.