sphenodon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The tuatara (''Sphenodon punctatus'') is a species of

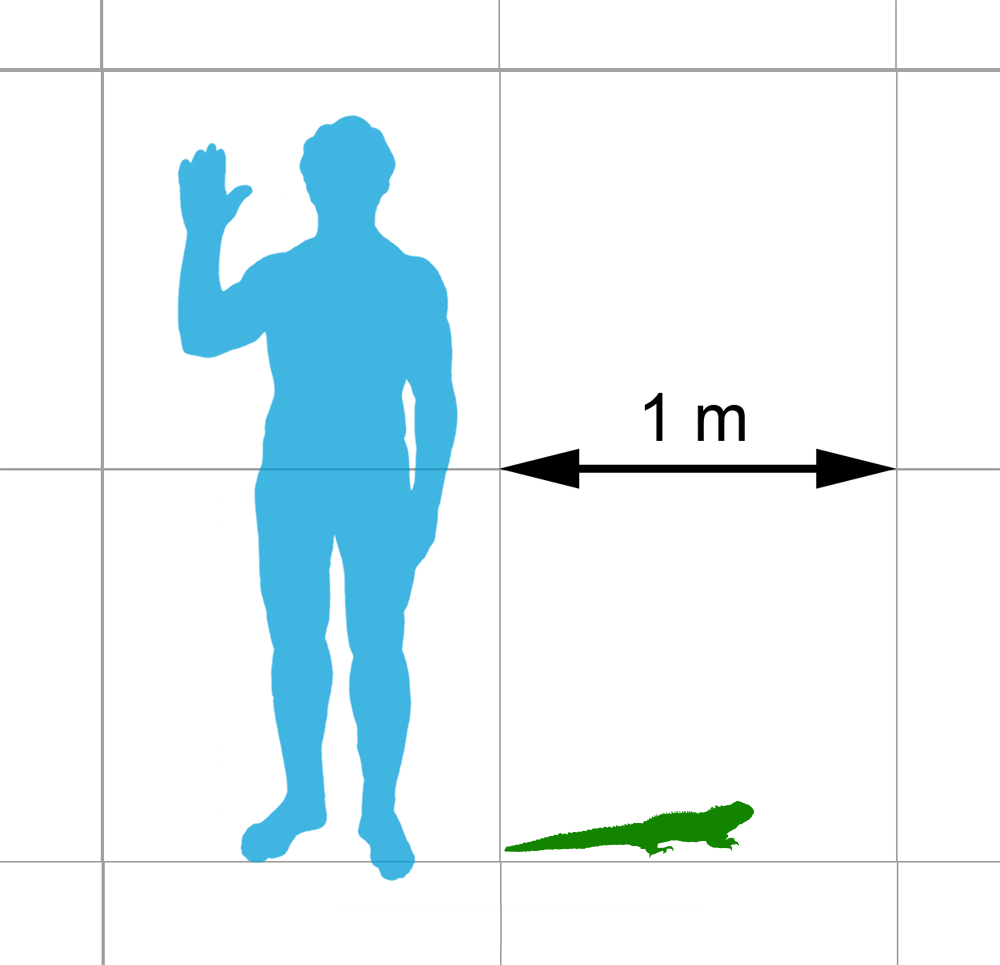

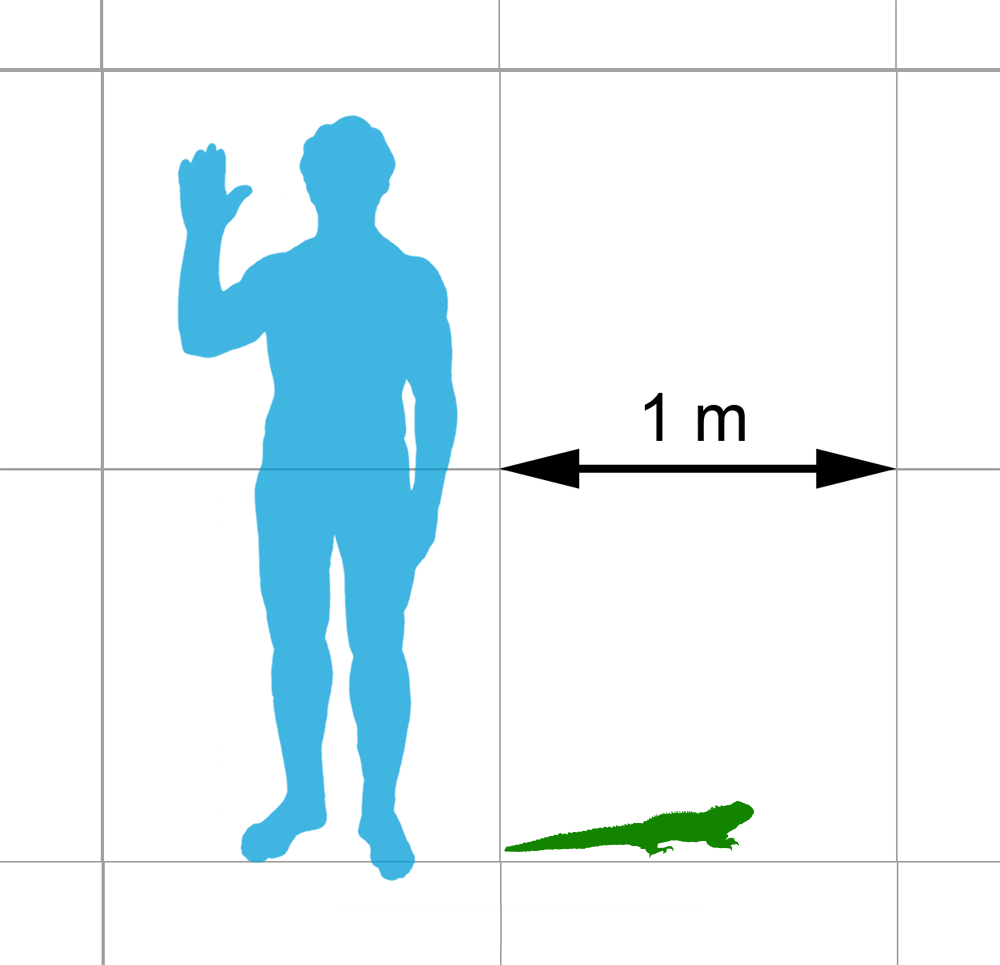

Tuatara are the largest reptiles in New Zealand. Adult ''S. punctatus'' males measure in length and females . Tuatara are

Tuatara are the largest reptiles in New Zealand. Adult ''S. punctatus'' males measure in length and females . Tuatara are

Unlike the vast majority of lizards, the tuatara has a complete lower temporal bar closing the lower temporal fenestra (an opening of the skull behind the eye socket), caused by the fusion of the quadrate/ quadratojugal (which are fused into a single element in adult tuatara) and the

Unlike the vast majority of lizards, the tuatara has a complete lower temporal bar closing the lower temporal fenestra (an opening of the skull behind the eye socket), caused by the fusion of the quadrate/ quadratojugal (which are fused into a single element in adult tuatara) and the

''S. punctatus punctatus'' naturally occurs on 29 islands, and its population is estimated to be over 60,000 individuals. In 1996, 32 adult northern tuatara were moved from Moutoki Island to Moutohora. The carrying capacity of Moutohora is estimated at 8,500 individuals, and the island could allow public viewing of wild tuatara. In 2003, 60 northern tuatara were introduced to

''S. punctatus punctatus'' naturally occurs on 29 islands, and its population is estimated to be over 60,000 individuals. In 1996, 32 adult northern tuatara were moved from Moutoki Island to Moutohora. The carrying capacity of Moutohora is estimated at 8,500 individuals, and the island could allow public viewing of wild tuatara. In 2003, 60 northern tuatara were introduced to

reptile

Reptiles, as commonly defined, are a group of tetrapods with an ectothermic metabolism and Amniotic egg, amniotic development. Living traditional reptiles comprise four Order (biology), orders: Testudines, Crocodilia, Squamata, and Rhynchocepha ...

endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

to New Zealand

New Zealand () is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and List of islands of New Zealand, over 600 smaller islands. It is the List of isla ...

. Despite its close resemblance to lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s, it is actually the only extant member of a distinct lineage, the previously highly diverse order Rhynchocephalia. The name is derived from the Māori language

Māori (; endonym: 'the Māori language', commonly shortened to ) is an Eastern Polynesian languages, Eastern Polynesian language and the language of the Māori people, the indigenous population of mainland New Zealand. The southernmost membe ...

and means "peaks on the back".

The single extant species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of tuatara is the only surviving member of its order, which was highly diverse during the Mesozoic

The Mesozoic Era is the Era (geology), era of Earth's Geologic time scale, geological history, lasting from about , comprising the Triassic, Jurassic and Cretaceous Period (geology), Periods. It is characterized by the dominance of archosaurian r ...

era. Rhynchocephalians first appeared in the fossil record during the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.5 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago ( Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.4 Mya. The Triassic is t ...

, around 240 million years ago, and reached worldwide distribution and peak diversity during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

, when they represented the world's dominant group of small reptiles. Rhynchocephalians declined during the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

, with their youngest records outside New Zealand dating to the Paleocene

The Paleocene ( ), or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), ...

. Their closest living relatives are squamates (lizards and snake

Snakes are elongated limbless reptiles of the suborder Serpentes (). Cladistically squamates, snakes are ectothermic, amniote vertebrates covered in overlapping scales much like other members of the group. Many species of snakes have s ...

s). Tuatara are of interest for studying the evolution of reptiles.

Tuatara are greenish brown and grey, and measure up to from head to tail-tip and weigh up to with a spiny crest along the back, especially pronounced in males. They have two rows of teeth in the upper jaw overlapping one row on the lower jaw, which is unique among living species. They are able to hear, although no external ear is present, and have unique features in their skeleton.

Tuatara are sometimes referred to as "living fossil

A living fossil is a Deprecation, deprecated term for an extant taxon that phenotypically resembles related species known only from the fossil record. To be considered a living fossil, the fossil species must be old relative to the time of or ...

s". This term is currently deprecated among paleontologists and evolutionary biologists. Although tuatara have preserved the morphological characteristics of their Mesozoic ancestors (240–230 million years ago), there is no evidence of a continuous fossil record to support the idea that the species has survived unchanged since that time.

The species has between five and six billion base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

s of DNA sequence

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases within the nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. This succession is denoted by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of the nu ...

, nearly twice that of humans.

The tuatara has been protected by law since 1895. Tuatara, like many of New Zealand's native animals, are threatened by habitat loss and introduced predators, such as the Polynesian rat

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), or , is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. Contrary to its vernacular name, the Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asi ...

''(Rattus exulans)''. Tuatara were extinct on the mainland, with the remaining populations confined to 32 offshore islands, until the first North Island release into the heavily fenced and monitored Karori Wildlife Sanctuary (now named "Zealandia") in 2005. During routine maintenance work at Zealandia

Zealandia (pronounced ), also known as (Māori language, Māori) or Tasmantis (from Tasman Sea), is an almost entirely submerged continent, submerged mass of continental crust in Oceania that subsided after breaking away from Gondwana 83� ...

in late 2008, a tuatara nest was uncovered, with a hatchling found the following autumn. This is thought to be the first case of tuatara successfully breeding in the wild on New Zealand's North Island in over 200 years.

Taxonomy and evolution

Relationships of the tuatara to other living reptiles and birds, after Simões et al. 2022 Tuatara, along with other now-extinct members of the order Rhynchocephalia, belong to the superorderLepidosauria

The Lepidosauria (, from Greek meaning ''scaled lizards'') is a Order (biology), superorder or Class (biology), subclass of reptiles, containing the orders Squamata and Rhynchocephalia. Squamata also includes Lizard, lizards and Snake, snakes. Sq ...

, as do the order Squamata

Squamata (, Latin ''squamatus'', 'scaly, having scales') is the largest Order (biology), order of reptiles; most members of which are commonly known as Lizard, lizards, with the group also including Snake, snakes. With over 11,991 species, it i ...

, which includes lizards and snakes. Squamates and tuatara both show caudal autotomy (loss of the tail-tip when threatened), and have transverse cloaca

A cloaca ( ), : cloacae ( or ), or vent, is the rear orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive (rectum), reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles, birds, cartilagin ...

l slits.

Tuatara were originally classified as lizards in 1831 when the British Museum

The British Museum is a Museum, public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is the largest in the world. It documents the story of human cu ...

received a skull. John Edward Gray

John Edward Gray (12 February 1800 – 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray (1766–1828). The same is used for a z ...

used the name ''Sphenodon'' to describe the skull; this remains the current scientific name for the genus. ''Sphenodon'' is derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

for "wedge" (σφήν, σφηνός/''sphenos'') and "tooth" (ὀδούς, ὀδόντος/''odontos''). In 1842, Gray described a member of the species as ''Hatteria punctata'', not realising that it and the skull he received in 1831 were both tuatara.

The genus remained misclassified as a lizard until 1867, when Albert C. L. G. Günther of the British Museum noted features similar to birds, turtles, and crocodiles. He proposed the order Rhynchocephalia (meaning "beak head") for the tuatara and its fossil relatives. Since 1869, ''Sphenodon punctatus'' (or the variation ''Sphenodon punctatum'' in some earlier sources) has been used as the scientific name for the species.

At one point, many disparate species were incorrectly referred to the Rhynchocephalia, resulting in what taxonomists call a "wastebasket taxon

Wastebasket taxon (also called a wastebin taxon, dustbin taxon or catch-all taxon) is a term used by some taxonomists to refer to a taxon that has the purpose of classifying organisms that do not fit anywhere else. They are typically defined by e ...

". Williston in 1925 proposed the Sphenodontia to include only tuatara and their closest fossil relatives. However, Rhynchocephalia is the older name and in widespread use today. Many scholars use Sphenodontia as a subset of Rhynchocephalia, including almost all members of Rhynchocephalia, apart from the most primitive representatives of the group.

The earliest rhynchocephalian, '' Wirtembergia'', is known from the Middle Triassic

In the geologic timescale, the Middle Triassic is the second of three epoch (geology), epochs of the Triassic period (geology), period or the middle of three series (stratigraphy), series in which the Triassic system (stratigraphy), system is di ...

of Germany, around 240 million years ago. During the Late Triassic

The Late Triassic is the third and final epoch (geology), epoch of the Triassic geologic time scale, Period in the geologic time scale, spanning the time between annum, Ma and Ma (million years ago). It is preceded by the Middle Triassic Epoch a ...

, rhynchocephalians greatly diversified, going on to become the world's dominant group of small reptiles during the Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

period, when the group was represented by a diversity of forms, including the aquatic pleurosaurs and the herbivorous eilenodontines. The earliest members of Sphenodontinae, the clade which includes the tuatara, are known from the Early Jurassic

The Early Jurassic Epoch (geology), Epoch (in chronostratigraphy corresponding to the Lower Jurassic series (stratigraphy), Series) is the earliest of three epochs of the Jurassic Period. The Early Jurassic starts immediately after the Triassic� ...

of North America. The earliest representatives of this group are already very similar to the modern tuatara. Rhynchocephalians declined during the Cretaceous

The Cretaceous ( ) is a geological period that lasted from about 143.1 to 66 mya (unit), million years ago (Mya). It is the third and final period of the Mesozoic Era (geology), Era, as well as the longest. At around 77.1 million years, it is the ...

period, possibly due to competition with mammals and lizards, with their youngest record outside of New Zealand being of '' Kawasphenodon'', known from the Paleocene

The Paleocene ( ), or Palaeocene, is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 66 to 56 mya (unit), million years ago (mya). It is the first epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), ...

of Patagonia in South America.

A species of sphenodontine is known from the Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first epoch (geology), geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and mea ...

Saint Bathans fauna from Otago

Otago (, ; ) is a regions of New Zealand, region of New Zealand located in the southern half of the South Island and administered by the Otago Regional Council. It has an area of approximately , making it the country's second largest local go ...

in the South Island of New Zealand. Whether it is referable to ''Sphenodon'' proper is not entirely clear, but it is likely to be closely related to tuatara. The ancestors of the tuatara were likely already present in New Zealand prior to its separation from Antarctica around 82–60 million years ago.

Cladogram of the position of the tuatara within Sphenodontia, after Simoes et al., 2022:

Species

While there is currently considered to be only one living species of tuatara, two species were previously identified: ''Sphenodon punctatus'', or northern tuatara, and the much rarer ''Sphenodon guntheri'', or Brothers Island tuatara, which is confined to North Brother Island in theCook Strait

Cook Strait () is a strait that separates the North Island, North and South Islands of New Zealand. The strait connects the Tasman Sea on the northwest with the South Pacific Ocean on the southeast. It is wide at its narrowest point,McLintock, ...

. The specific name ''punctatus'' is Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

for "spotted", and ''guntheri'' refers to German-born British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

herpetologist

Herpetology (from Ancient Greek ἑρπετόν ''herpetón'', meaning "reptile" or "creeping animal") is a branch of zoology concerned with the study of amphibians (including frogs, salamanders, and caecilians (Gymnophiona)) and reptiles (in ...

Albert Günther

Albert Karl Ludwig Gotthilf Günther , also Albert Charles Lewis Gotthilf Günther (3October 18301February 1914), was a German-born British zoologist, ichthyologist, and herpetologist. Günther is ranked the second-most productive reptile tax ...

. A 2009 paper re-examined the genetic bases used to distinguish the two supposed species of tuatara, and concluded they represent only geographic variants, and only one species should be recognised. Consequently, the northern tuatara was re-classified as ''Sphenodon punctatus punctatus'' and the Brothers Island tuatara as ''Sphenodon punctatus guntheri''. The Brothers Island tuatara has olive brown skin with yellowish patches, while the colour of the northern tuatara ranges from olive green through grey to dark pink or brick red, often mottled, and always with white spots. In addition, the Brothers Island tuatara is considerably smaller. However, individuals from Brothers Island could not be distinguished from other modern and fossil samples on the basis of jaw morphology.

An extinct species of ''Sphenodon'' was identified in November 1885 by William Colenso, who was sent an incomplete subfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

specimen from a local coal mine. Colenso named the new species ''S. diversum''. Fawcett and Smith (1970) consider it a synonym to the subspecies, based on a lack of distinction.

Description

Tuatara are the largest reptiles in New Zealand. Adult ''S. punctatus'' males measure in length and females . Tuatara are

Tuatara are the largest reptiles in New Zealand. Adult ''S. punctatus'' males measure in length and females . Tuatara are sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where sexes of the same species exhibit different Morphology (biology), morphological characteristics, including characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most dioecy, di ...

, males being larger. The San Diego Zoo

The San Diego Zoo is a zoo in San Diego, California, United States, located in Balboa Park (San Diego), Balboa Park. It began with a collection of animals left over from the 1915 Panama–California Exposition that were brought together by its ...

even cites a length of up to . Males weigh up to , and females up to . Brothers Island tuatara are slightly smaller, weighing up to 660 g (1.3 lb).

Their lungs have a single chamber with no bronchi

A bronchus ( ; : bronchi, ) is a passage or airway in the lower respiratory tract that conducts air into the lungs. The first or primary bronchi to branch from the trachea at the carina are the right main bronchus and the left main bronchus. Thes ...

.

The tuatara's greenish brown colour matches its environment, and can change over its lifetime. Tuatara shed their skin at least once per year as adults, and three or four times a year as juveniles. Tuatara sexes differ in more than size. The spiny crest on a tuatara's back, made of triangular, soft folds of skin, is larger in males, and can be stiffened for display. The male abdomen is narrower than the female's.

Skull

jugal bone

The jugal is a skull bone found in most reptiles, amphibians and birds. In mammals, the jugal is often called the malar or zygomatic bone, zygomatic. It is connected to the quadratojugal and maxilla, as well as other bones, which may vary by spe ...

s of the skull. This is similar to the condition found in primitive diapsid reptiles. However, because more primitive rhynchocephalians have an open lower temporal fenestra with an incomplete temporal bar, this is thought to be derived characteristic of the tuatara and other members of the clade Sphenodontinae, rather than a primitive trait retained from early diapsids. The complete bar is thought to stabilise the skull during biting.

The tip of the upper jaw is chisel- or beak-like and separated from the remainder of the jaw by a notch, this structure is formed from fused premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

ry teeth, and is also found in many other advanced rhynchocephalians. The teeth of the tuatara, and almost all other rhynchocephalians, are described as acrodont, as they are attached to the apex of the jaw bone. This contrast with the pleurodont condition found in the vast majority of lizards, where the teeth are attached to the inward-facing surface of the jaw. The teeth of the tuatara are extensively fused to the jawbone, making the boundary between the tooth and jaw difficult to discern, and the teeth lack roots and are not replaced during the lifetime of the animal, unlike those of pleurodont lizards. It is a common misconception that tuatara lack teeth and instead have sharp projections on the jaw bone; histology shows that they have true teeth with enamel and dentine with pulp cavities. As their teeth wear down, older tuatara have to switch to softer prey, such as earthworm

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class (or subclass, depending on the author) Oligochaeta. In classical systems, they we ...

s, larva

A larva (; : larvae ) is a distinct juvenile form many animals undergo before metamorphosis into their next life stage. Animals with indirect development such as insects, some arachnids, amphibians, or cnidarians typically have a larval phase ...

e, and slug

Slug, or land slug, is a common name for any apparently shell-less Terrestrial mollusc, terrestrial gastropod mollusc. The word ''slug'' is also often used as part of the common name of any gastropod mollusc that has no shell, a very reduced ...

s, and eventually have to chew their food between smooth jaw bones.

The tuatara possesses palatal dentition (teeth growing from the bones of the roof of the mouth), which is ancestrally present in reptiles (and tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s generally). While many of the original palatal teeth present in reptiles have been lost, as in all other known rhynchocephalians, the row of teeth growing from the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal species, located above the uvula in the throat. Together with the maxilla, they comprise the hard palate.

Stru ...

s in the tuatara have been enlarged, and as in other members of Sphenodontinae the palatine teeth are orientated parallel to the teeth in the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

; during biting the teeth of the lower jaw slot between the two upper tooth rows. The structure of the jaw joint allows the lower jaw to slide forwards after it has closed between the two upper rows of teeth. This mechanism allows the jaws to shear through chitin

Chitin (carbon, C8hydrogen, H13oxygen, O5nitrogen, N)n ( ) is a long-chain polymer of N-Acetylglucosamine, ''N''-acetylglucosamine, an amide derivative of glucose. Chitin is the second most abundant polysaccharide in nature (behind only cell ...

and bone.

The brain of ''Sphenodon'' fills only half of the volume of its endocranium

The endocranium in comparative anatomy is a part of the skull base in vertebrates and it represents the basal, inner part of the cranium. The term is also applied to the outer layer of the dura mater in human anatomy.

Structure

Structurally, t ...

. This proportion has been used by paleontologists trying to estimate the volume of dinosaur brains based on fossils. However, the proportion of the tuatara endocranium occupied by its brain may not be a very good guide to the same proportion in Mesozoic dinosaurs since modern birds are surviving dinosaurs but have brains which occupy a much greater relative volume in the endocranium.

Sensory organs

Eyes

The eyes canfocus

Focus (: foci or focuses) may refer to:

Arts

* Focus or Focus Festival, former name of the Adelaide Fringe arts festival in East Australia Film

*Focus (2001 film), ''Focus'' (2001 film), a 2001 film based on the Arthur Miller novel

*Focus (2015 ...

independently, and are specialised with three types of photoreceptive cells, all with fine structural characteristics of retinal cone cell

Cone cells or cones are photoreceptor cells in the retina of the vertebrate eye. Cones are active in daylight conditions and enable photopic vision, as opposed to rod cells, which are active in dim light and enable scotopic vision. Most v ...

s used for both day and night vision, and a ''tapetum lucidum

The ; ; : tapeta lucida) is a layer of tissue in the eye of many vertebrates and some other animals. Lying immediately behind the retina, it is a retroreflector. It Reflection (physics), reflects visible light back through the retina, increas ...

'' which reflects onto the retina to enhance vision in the dark. There is also a third eyelid on each eye, the nictitating membrane

The nictitating membrane (from Latin '' nictare'', to blink) is a transparent or translucent third eyelid present in some animals that can be drawn across the eye from the medial canthus to protect and moisten it while maintaining vision. Most ...

. Five visual opsin

Animal opsins are G-protein-coupled receptors and a group of proteins made light-sensitive via a chromophore, typically retinal. When bound to retinal, opsins become retinylidene proteins, but are usually still called opsins regardless. Most pro ...

genes are present, suggesting good colour vision

Color vision, a feature of visual perception, is an ability to perceive differences between light composed of different frequencies independently of light intensity.

Color perception is a part of the larger visual system and is mediated by a co ...

, possibly even at low light levels.

Parietal eye (third eye)

Like some other living vertebrates, including some lizards, the tuatara has a third eye on the top of its head called the parietal eye (also called a pineal or third eye) formed by the parapineal organ, with an accompanying opening in the skull roof called the pineal or parietal foramen, enclosed by theparietal bone

The parietal bones ( ) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four bord ...

s. It has its own lens, a parietal plug which resembles a cornea

The cornea is the transparency (optics), transparent front part of the eyeball which covers the Iris (anatomy), iris, pupil, and Anterior chamber of eyeball, anterior chamber. Along with the anterior chamber and Lens (anatomy), lens, the cornea ...

, retina

The retina (; or retinas) is the innermost, photosensitivity, light-sensitive layer of tissue (biology), tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some Mollusca, molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focus (optics), focused two-dimensional ...

with rod-like structures, and degenerated nerve connection to the brain. The parietal eye is visible only in hatchlings, which have a translucent patch at the top centre of the skull. After four to six months, it becomes covered with opaque scales and pigment. While capable of detecting light, it is probably not capable of detecting movement or forming an image. It likely serves to regulate the circadian rhythm

A circadian rhythm (), or circadian cycle, is a natural oscillation that repeats roughly every 24 hours. Circadian rhythms can refer to any process that originates within an organism (i.e., Endogeny (biology), endogenous) and responds to the env ...

and possibly detect seasonal changes, and help with thermoregulation

Thermoregulation is the ability of an organism to keep its body temperature within certain boundaries, even when the surrounding temperature is very different. A thermoconforming organism, by contrast, simply adopts the surrounding temperature ...

.

Of all extant tetrapods, the parietal eye is most pronounced in the tuatara. It is part of the pineal complex, another part of which is the pineal gland

The pineal gland (also known as the pineal body or epiphysis cerebri) is a small endocrine gland in the brain of most vertebrates. It produces melatonin, a serotonin-derived hormone, which modulates sleep, sleep patterns following the diurnal c ...

, which in tuatara secretes melatonin at night. Some salamander

Salamanders are a group of amphibians typically characterized by their lizard-like appearance, with slender bodies, blunt snouts, short limbs projecting at right angles to the body, and the presence of a tail in both larvae and adults. All t ...

s have been shown to use their pineal bodies to perceive polarised light, and thus determine the position of the sun, even under cloud cover, aiding navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

.

Hearing

Together withturtle

Turtles are reptiles of the order (biology), order Testudines, characterized by a special turtle shell, shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Crypt ...

s, the tuatara has the most primitive hearing organs among the amniotes. There is no tympanum (eardrum

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit changes in pres ...

) and no earhole, and the middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles (malleus, incus, and stapes), which transfer the vibrations ...

cavity is filled with loose tissue, mostly adipose (fatty) tissue. The stapes

The ''stapes'' or stirrup is a bone in the middle ear of humans and other tetrapods which is involved in the conduction of sound vibrations to the inner ear. This bone is connected to the oval window by its annular ligament, which allows the f ...

comes into contact with the quadrate (which is immovable), as well as the hyoid

The hyoid-bone (lingual-bone or tongue-bone) () is a horseshoe-shaped bone situated in the anterior midline of the neck between the chin and the thyroid-cartilage. At rest, it lies between the base of the mandible and the third cervical verte ...

and squamosal. The hair cell

Hair cells are the sensory receptors of both the auditory system and the vestibular system in the ears of all vertebrates, and in the lateral line organ of fishes. Through mechanotransduction, hair cells detect movement in their environment. ...

s are unspecialised, innervated by both afferent and efferent nerve fibres, and respond only to low frequencies. Though the hearing organs are poorly developed and primitive with no visible external ears, they can still show a frequency response from 100 to 800 Hz, with peak sensitivity of 40 dB at 200 Hz.

Odorant receptors

Animals that depend on the sense of smell to capture prey, escape from predators or simply interact with the environment they inhabit, usually have many odorant receptors. These receptors are expressed in the dendritic membranes of the neurons for the detection of odours. The tuatara has around 472 receptors, a number more similar to what birds have than to the large number of receptors that turtles and crocodiles may have.Spine and ribs

The tuatara spine is made up of hourglass-shaped amphicoelous vertebrae, concave both before and behind. This is the usual condition of fish vertebrae and some amphibians, but is unique to tuatara within the amniotes. The vertebral bodies have a tiny hole through which a constricted remnant of the notochord passes; this was typical in early fossil reptiles, but lost in most other amniotes. The tuatara has gastralia, rib-like bones also called gastric or abdominal ribs, the presumed ancestral trait of diapsids. They are found in somelizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s, where they are mostly made of cartilage, as well as crocodiles and the tuatara, and are not attached to the spine or thoracic ribs. The true ribs are small projections, with small, hooked bones, called uncinate processes, found on the rear of each rib. This feature is also present in birds. The tuatara is the only living tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

with well-developed gastralia and uncinate processes.

In the early tetrapods, the gastralia and ribs with uncinate processes, together with bony elements such as bony plates in the skin (osteoderms) and clavicle

The clavicle, collarbone, or keybone is a slender, S-shaped long bone approximately long that serves as a strut between the scapula, shoulder blade and the sternum (breastbone). There are two clavicles, one on each side of the body. The clavic ...

s (collar bone), would have formed a sort of exoskeleton around the body, protecting the belly and helping to hold in the guts and inner organs. These anatomical details most likely evolved from structures involved in locomotion even before the vertebrates ventured onto land. The gastralia may have been involved in the breathing process in early amphibians and reptiles. The pelvis and shoulder girdles are arranged differently from those of lizards, as is the case with other parts of the internal anatomy and its scales.

Tail and back

The spiny plates on the back and tail of the tuatara resemble those of a crocodile more than a lizard, but the tuatara shares with lizards the ability to break off its tail when caught by a predator, and then regenerate it. The regrowth takes a long time and differs from that of lizards. Well illustrated reports on tail regeneration in tuatara have been published by Alibardi and Meyer-Rochow. The cloacal glands of tuatara have a uniqueorganic compound

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

named tuataric acid.

Age determination

Currently, there are two means of determining the age of tuatara. Using microscopic inspection, hematoxylinophilic rings can be identified and counted in both the phalanges and the femur. Phalangeal hematoxylinophilic rings can be used for tuatara up to ages 12–14 years, as they cease to form around this age. Femoral rings follow a similar trend, however they are useful for tuatara up to ages 25–35 years. Around that age, femoral rings cease to form. Further research on age determination methods for tuatara is required, as tuatara have lifespans much longer than 35 years (ages up to 60 are common, and captive tuatara have lived to over 100 years). One possibility could be via examination of tooth wear, as tuatara have fused sets of teeth.Physiology

Adult tuatara are terrestrial andnocturnal

Nocturnality is a ethology, behavior in some non-human animals characterized by being active during the night and sleeping during the day. The common adjective is "nocturnal", versus diurnality, diurnal meaning the opposite.

Nocturnal creatur ...

reptiles, though they will often bask in the sun to warm their bodies. Hatchlings hide under logs and stones, and are diurnal, likely because adults are cannibalistic. Juveniles are typically active at night, but can be found active during the day. The juveniles' movement pattern is attributed to genetic hardwire of conspecifics for predator avoidance and thermal restrictions. Tuatara thrive in temperatures much lower than those tolerated by most reptiles, and hibernate during winter. They remain active at temperatures as low as , while temperatures over are generally fatal. The optimal body temperature for the tuatara is from , the lowest of any reptile. The body temperature of tuatara is lower than that of other reptiles, ranging from over a day, whereas most reptiles have body temperatures around . The low body temperature results in a slower metabolism

Metabolism (, from ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cellular processes; the co ...

.

Ecology

Burrowing seabirds such aspetrel

Petrels are tube-nosed seabirds in the phylogenetic order Procellariiformes.

Description

Petrels are a monophyletic group of marine seabirds, sharing a characteristic of a nostril arrangement that results in the name "tubenoses". Petrels enco ...

s, prions, and shearwaters share the tuatara's island habitat during the birds' nesting seasons. The tuatara use the bird

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class (biology), class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the Oviparity, laying of Eggshell, hard-shelled eggs, a high Metabolism, metabolic rate, a fou ...

s' burrows for shelter when available, or dig their own. The seabirds' guano

Guano (Spanish from ) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. Guano is a highly effective fertiliser due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. Guano was also, to a le ...

helps to maintain invertebrate populations on which tuatara predominantly prey, including beetle

Beetles are insects that form the Taxonomic rank, order Coleoptera (), in the superorder Holometabola. Their front pair of wings are hardened into wing-cases, elytra, distinguishing them from most other insects. The Coleoptera, with about 40 ...

s, crickets

Crickets are orthopteran insects which are related to bush crickets and more distantly, to grasshoppers. In older literature, such as Imms,Imms AD, rev. Richards OW & Davies RG (1970) ''A General Textbook of Entomology'' 9th Ed. Methuen 886 ...

, spider

Spiders (order (biology), order Araneae) are air-breathing arthropods that have eight limbs, chelicerae with fangs generally able to inject venom, and spinnerets that extrude spider silk, silk. They are the largest order of arachnids and ran ...

s, wētā

Wētā (also spelled weta in English) is the common name for a group of about 100 insect species in the families Anostostomatidae and Rhaphidophoridae endemism, endemic to New Zealand. They are giant wingless insect, flightless cricket (insect ...

s, earthworm

An earthworm is a soil-dwelling terrestrial invertebrate that belongs to the phylum Annelida. The term is the common name for the largest members of the class (or subclass, depending on the author) Oligochaeta. In classical systems, they we ...

s, and snail

A snail is a shelled gastropod. The name is most often applied to land snails, terrestrial molluscs, terrestrial pulmonate gastropod molluscs. However, the common name ''snail'' is also used for most of the members of the molluscan class Gas ...

s. Their diets also consist of frog

A frog is any member of a diverse and largely semiaquatic group of short-bodied, tailless amphibian vertebrates composing the order (biology), order Anura (coming from the Ancient Greek , literally 'without tail'). Frog species with rough ski ...

s, lizard

Lizard is the common name used for all Squamata, squamate reptiles other than snakes (and to a lesser extent amphisbaenians), encompassing over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most Island#Oceanic isla ...

s, and bird's eggs and chicks. Young tuatara are also occasionally cannibalised. The diet of the tuatara varies seasonally, and they consume mainly fairy prions and their eggs in the summer. In total darkness no feeding attempt was observed, and the lowest light intensity at which an attempt to snatch a beetle was observed occurred under 0.0125 lux. The eggs and young of seabirds that are seasonally available as food for tuatara may provide beneficial fatty acids. Tuatara of both sexes defend territories, and will threaten and eventually bite intruders. The bite can cause serious injury. Tuatara will bite when approached, and will not let go easily. Female tuatara rarely exhibit parental behaviour by guarding nests on islands with high rodent populations.

Tuataras are parasitised by the tuatara tick (''Archaeocroton sphenodonti''), a tick

Ticks are parasitic arachnids of the order Ixodida. They are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, and species, but can become larger when engorged. Ticks a ...

that directly depends on tuataras. These ticks tend to be more prevalent on larger males, as they have larger home ranges than smaller and female tuatara and interact with other tuatara more in territorial displays.

Reproduction

Tuatara reproduce very slowly, taking 10 to 20 years to reach sexual maturity. Though their reproduction rate is slow, tuatara have the fastest swimming sperm by two to four times compared to all reptiles studied earlier. Mating occurs in midsummer; females mate and layegg

An egg is an organic vessel grown by an animal to carry a possibly fertilized egg cell (a zygote) and to incubate from it an embryo within the egg until the embryo has become an animal fetus that can survive on its own, at which point the ...

s once every four years. During courtship, a male makes his skin darker, raises his crests, and parades toward the female. He slowly walks in circles around the female with stiffened legs. The female will either allow the male to mount her, or retreat to her burrow. Males do not have a penis; they have rudimentary hemipenes; meaning that intromittent organs are used to deliver sperm to the female during copulation. They reproduce by the male lifting the tail of the female and placing his vent

Vent or vents may refer to:

Science and technology Biology

*Vent, the cloaca region of an animal

*Vent DNA polymerase, a thermostable DNA polymerase

Geology

*Hydrothermal vent, a fissure in a planet's surface from which geothermally heated water ...

over hers. This process is sometimes referred to as a "cloacal kiss". The sperm

Sperm (: sperm or sperms) is the male reproductive Cell (biology), cell, or gamete, in anisogamous forms of sexual reproduction (forms in which there is a larger, female reproductive cell and a smaller, male one). Animals produce motile sperm ...

is then transferred into the female, much like the mating process in birds. Along with birds, the tuatara is one of the few members of Amniota

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolved from amphibious stem tetrapod ancestors during the C ...

to have lost the ancestral penis.

Tuatara eggs have a soft, parchment-like 0.2 mm thick shell that consists of calcite crystals embedded in a matrix of fibrous layers. It takes the females between one and three years to provide eggs with yolk, and up to seven months to form the shell. It then takes between 12 and 15 months from copulation to hatching. This means reproduction occurs at two- to five-year intervals, the slowest in any reptile. Survival of embryos has also been linked to having more success in moist conditions. Wild tuatara are known to be still reproducing at about 60 years of age; " Henry", a male tuatara at Southland Museum in Invercargill

Invercargill ( , ) is the southernmost and westernmost list of cities in New Zealand, city in New Zealand, and one of the Southernmost settlements, southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland Region, Southlan ...

, New Zealand, became a father (possibly for the first time) on 23 January 2009, at age 111, with an 80 year-old female.

The sex of a hatchling depends on the temperature of the egg, with warmer eggs tending to produce male tuatara, and cooler eggs producing females. Eggs incubated at have an equal chance of being male or female. However, at , 80% are likely to be males, and at , 80% are likely to be females; at all hatchlings will be females. Some evidence indicates sex determination in tuatara is determined by both genetic and environmental factors.

Tuatara probably have the slowest growth rates of any reptile, continuing to grow larger for the first 35 years of their lives. The average lifespan is about 60 years, but they can live to be well over 100 years old; tuatara could be the reptile with the second longest lifespan after tortoises. Some experts believe that captive tuatara could live as long as 200 years. This may be related to genes that offer protection against reactive oxygen species. The tuatara genome has 26 genes that encode selenoproteins and 4 selenocysteine

Selenocysteine (symbol Sec or U, in older publications also as Se-Cys) is the 21st proteinogenic amino acid. Selenoproteins contain selenocysteine residues. Selenocysteine is an analogue of the more common cysteine with selenium in place of the ...

-specific tRNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

genes. In humans, selenoproteins have a function of antioxidation, redox regulation and synthesis of thyroid hormones. It is not fully demonstrated, but these genes may be related to the longevity of this animal or may have emerged as a result of the low levels of selenium and other trace elements in the New Zealand terrestrial systems.

Genomic characteristics

The most abundantLINE element

In geometry, the line element or length element can be informally thought of as a line segment associated with an infinitesimal displacement vector in a metric space. The length of the line element, which may be thought of as a differential arc ...

in the tuatara is L2 (10%). Most of them are interspersed and can remain active. The longest L2 element found is 4 kb long and 83% of the sequences had ORF2p completely intact. The CR1 element is the second most repeated (4%). Phylogenetic analysis shows that these sequences are very different from those found in other nearby species such as lizards. Finally, less than 1% are elements belonging to L1, a low percentage since these elements tend to predominate in placental mammals. Usually, the predominant LINE elements are the CR1, contrary to what has been seen in the tuatara. This suggests that perhaps the genome repeats of sauropsids were very different compared to mammals, birds and lizards.

The genes of the major histocompatibility complex

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a large Locus (genetics), locus on vertebrate DNA containing a set of closely linked polymorphic genes that code for Cell (biology), cell surface proteins essential for the adaptive immune system. The ...

(MHC) are known to play roles in disease resistance, mate choice

Mate choice is one of the primary mechanisms under which evolution can occur. It is characterized by a "selective response by animals to particular stimuli" which can be observed as behavior.Bateson, Paul Patrick Gordon. "Mate Choice." Mate Choi ...

, and kin recognition in various vertebrate species. Among known vertebrate genomes, MHCs are considered one of the most polymorphic. In the tuatara, 56 MHC genes have been identified; some of which are similar to MHCs of amphibians and mammals. Most MHCs that were annotated in the tuatara genome are highly conserved, however there is large genomic rearrangement observed in distant lepidosaur lineages.

Many of the elements that have been analyzed are present in all amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s, most are mammalian interspersed repeats or MIR, specifically the diversity of MIR subfamilies is the highest that has been studied so far in an amniote. 16 families of SINEs that were recently active have also been identified.

The tuatara has 24 unique families of DNA transposon DNA transposons are DNA sequences, sometimes referred to "jumping genes", that can move and integrate to different locations within the genome. They are class II transposable elements (TEs) that move through a DNA intermediate, as opposed to class I ...

s, and at least 30 subfamilies were recently active. This diversity is greater than what has been found in other amniotes and in addition, thousands of identical copies of these transposons have been analyzed, suggesting to researchers that there is recent activity.

The genome is the second largest known to reptiles. Only the Greek tortoise

Greek tortoise (''Testudo graeca''), also known as the spur-thighed tortoise or Moorish tortoise, is a species of tortoise in the family Testudinidae. It is a medium sized herbivorous testudinae, widely distributed in the Mediterranean basin, M ...

genome is larger. Around 7,500 LTRs have been identified, including 450 endogenous retrovirus

Endogenous retroviruses (ERVs) are endogenous viral elements in the genome that closely resemble and can be derived from retroviruses. They are abundant in the genomes of jawed vertebrates, and they comprise up to 5–8% of the human genome ( ...

es (ERVs). Studies in other Sauropsida

Sauropsida (Greek language, Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the Class (biology), class Reptile, Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern repti ...

have recognised a similar number but nevertheless, in the genome of the tuatara it has been found a very old clade of retrovirus known as Spumavirus.

More than 8,000 non-coding RNA

A non-coding RNA (ncRNA) is a functional RNA molecule that is not Translation (genetics), translated into a protein. The DNA sequence from which a functional non-coding RNA is transcribed is often called an RNA gene. Abundant and functionally imp ...

-related elements have been identified in the tuatara genome, of which the vast majority, about 6,900, are derived from recently active transposable element

A transposable element (TE), also transposon, or jumping gene, is a type of mobile genetic element, a nucleic acid sequence in DNA that can change its position within a genome.

The discovery of mobile genetic elements earned Barbara McClinto ...

s. The rest are related to ribosomal, spliceosomal and signal recognition particle RNA.

The mitochondrial genome of the genus ''Sphenodon'' is approximately 18,000 bp in size and consists of 13 protein-coding genes, 2 ribosomal RNA

Ribosomal ribonucleic acid (rRNA) is a type of non-coding RNA which is the primary component of ribosomes, essential to all cells. rRNA is a ribozyme which carries out protein synthesis in ribosomes. Ribosomal RNA is transcribed from ribosomal ...

and 22 transfer RNA

Transfer ribonucleic acid (tRNA), formerly referred to as soluble ribonucleic acid (sRNA), is an adaptor molecule composed of RNA, typically 76 to 90 nucleotides in length (in eukaryotes). In a cell, it provides the physical link between the gene ...

genes.

DNA methylation

DNA methylation is a biological process by which methyl groups are added to the DNA molecule. Methylation can change the activity of a DNA segment without changing the sequence. When located in a gene promoter (genetics), promoter, DNA methylati ...

is a very common modification in animals and the distribution of CpG sites within genomes affects this methylation. Specifically, 81% of these CpG sites have been found to be methylated in the tuatara genome. Recent publications propose that this high level of methylation may be due to the amount of repeating elements that exist in the genome of this animal. This pattern is closer to what occurs in organisms such as zebrafish, about 78%, while in humans it is only 70%.

Conservation

Tuatara are absolutely protected under New Zealand'sWildlife Act 1953

Wildlife Act 1953 is an Act of Parliament in New Zealand. Under the act, the majority of native New Zealand vertebrate species are protected by law, and may not be hunted, killed, eaten or possessed. Violations may be punished with fines of up t ...

. The species is also listed under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

Convention may refer to:

* Convention (norm), a custom or tradition, a standard of presentation or conduct

** Treaty, an agreement in international law

** Convention (political norm), uncodified legal or political tradition

* Convention (meeting ...

(CITES) meaning commercial international trade in wild sourced specimens is prohibited and all other international trade (including in parts and derivatives) is regulated by the CITES permit system.

Distribution and threats

Tuatara were once widespread on New Zealand's main North and South Islands, wheresubfossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

remains have been found in sand dunes, caves, and Māori midden

A midden is an old dump for domestic waste. It may consist of animal bones, human excrement, botanical material, mollusc shells, potsherds, lithics (especially debitage), and other artifacts and ecofacts associated with past human oc ...

s. Wiped out from the main islands before European settlement, they were long confined to 32 offshore islands free of mammals. The islands are difficult to get to, and are colonised by few animal species, indicating that some animals absent from these islands may have caused tuatara to disappear from the mainland. However, ''kiore'' (Polynesian rats) had recently become established on several of the islands, and tuatara were persisting, but not breeding, on these islands. Additionally, tuatara were much rarer on the rat-inhabited islands. Prior to conservation work, 25% of the distinct tuatara populations had become extinct in the past century.

The recent discovery of a tuatara hatchling on the mainland indicates that attempts to re-establish a breeding population on the New Zealand mainland have had some success. The total population of tuatara is estimated to be between 60,000 and 100,000.

Climate change

Tuatara have temperature-dependent sex determination meaning that the temperature of the egg determines the sex of the animal. For tuatara, lower egg incubation temperatures lead to females while higher temperatures lead to males. Since global temperatures are increasing, climate change may be skewing the male to female ratio of tuatara. Current solutions to this potential future threat are the selective removal of adults and the incubation of eggs.Eradication of rats

Tuatara were removed from Stanley, Red Mercury and Cuvier Islands in 1990 and 1991, and maintained in captivity to allow Polynesian rats to be eradicated on those islands. All three populations bred in captivity, and after successful eradication of the rats, all individuals, including the new juveniles, were returned to their islands of origin. In the 1991–92 season,Little Barrier Island

Little Barrier Island, or Hauturu in Māori language, Māori (the official Māori title is ''Te Hauturu-o-Toi''), lies off the northeastern coast of New Zealand's North Island. Located to the north of Auckland, the island is separated from the ...

was found to hold only eight tuatara, which were taken into ''in situ

is a Latin phrase meaning 'in place' or 'on site', derived from ' ('in') and ' ( ablative of ''situs'', ). The term typically refers to the examination or occurrence of a process within its original context, without relocation. The term is use ...

'' captivity, where females produced 42 eggs, which were incubated at Victoria University. The resulting offspring were subsequently held in an enclosure on the island, then released into the wild in 2006 after rats were eradicated there.

In the Hen and Chicken Islands

The Hen and Chicken Islands, usually known as the Hen and Chickens, lie to the east of the North Auckland Peninsula off the coast of northern New Zealand. They lie east of Bream Head and south-east of Whangārei with a total area of .

H ...

, Polynesian rats were eradicated on Whatupuke in 1993, Lady Alice Island in 1994, and Coppermine Island in 1997. Following this program, juveniles have once again been seen on the latter three islands. In contrast, rats persist on Hen Island of the same group, and no juvenile tuatara have been seen there as of 2001. In the Alderman Islands, Middle Chain Island holds no tuatara, but it is considered possible for rats to swim between Middle Chain and other islands that do hold tuatara, and the rats were eradicated in 1992 to prevent this. Another rodent eradication was carried out on the Rangitoto Islands east of D'Urville Island, to prepare for the release of 432 Cook Strait tuatara juveniles in 2004, which were being raised at Victoria University as of 2001.

Brothers Island tuatara

''Sphenodon punctatus guntheri'' is present naturally on one small island with a population of approximately 400. In 1995, 50 juvenile and 18 adult Brothers Island tuatara were moved to Titi Island inCook Strait

Cook Strait () is a strait that separates the North Island, North and South Islands of New Zealand. The strait connects the Tasman Sea on the northwest with the South Pacific Ocean on the southeast. It is wide at its narrowest point,McLintock, ...

, and their establishment monitored. Two years later, more than half of the animals had been seen again and of those all but one had gained weight. In 1998, 34 juveniles from captive breeding and 20 wild-caught adults were similarly transferred to Matiu/Somes Island, a more publicly accessible location in Wellington Harbour. The captive juveniles were from induced layings from wild females.

In late October 2007, 50 tuatara collected as eggs from North Brother Island and hatched at Victoria University were being released onto Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

in the outer Marlborough Sounds

The Marlborough Sounds (Māori language, te reo Māori: ''Te Tauihu-o-te-Waka'') are an extensive network of ria, sea-drowned valleys at the northern end of the South Island of New Zealand. The Marlborough Sounds were created by a combination ...

. The animals had been cared for at Wellington Zoo for the previous five years and had been kept in secret in a specially built enclosure at the zoo, off display.

There is another out of country population of Brothers Island tuatara that was given to the San Diego Zoological Society and is housed off-display at the San Diego Zoo

The San Diego Zoo is a zoo in San Diego, California, United States, located in Balboa Park (San Diego), Balboa Park. It began with a collection of animals left over from the 1915 Panama–California Exposition that were brought together by its ...

facility in Balboa. No successful reproductive efforts have been reported yet.

Northern tuatara

''S. punctatus punctatus'' naturally occurs on 29 islands, and its population is estimated to be over 60,000 individuals. In 1996, 32 adult northern tuatara were moved from Moutoki Island to Moutohora. The carrying capacity of Moutohora is estimated at 8,500 individuals, and the island could allow public viewing of wild tuatara. In 2003, 60 northern tuatara were introduced to

''S. punctatus punctatus'' naturally occurs on 29 islands, and its population is estimated to be over 60,000 individuals. In 1996, 32 adult northern tuatara were moved from Moutoki Island to Moutohora. The carrying capacity of Moutohora is estimated at 8,500 individuals, and the island could allow public viewing of wild tuatara. In 2003, 60 northern tuatara were introduced to Tiritiri Matangi Island

Tiritiri Matangi Island is located in the Hauraki Gulf of New Zealand, east of the Whangaparāoa Peninsula in the North Island and north east of Auckland. The island is an open nature reserve managed by the Supporters of Tiritiri Matangi Incor ...

from Middle Island in the Mercury group. They are occasionally seen sunbathing by visitors to the island.

A mainland release of ''S.p. punctatus'' occurred in 2005 in the heavily fenced and monitored Karori Sanctuary. The second mainland release took place in October 2007, when a further 130 were transferred from Stephens Island to the Karori Sanctuary. In early 2009, the first recorded wild-born offspring were observed.

Captive breeding

The first successful breeding of tuatara in captivity is believed to have achieved by Sir Algernon Thomas at either his University offices or residence in Symonds Street in the late 1880s or his new home, Trewithiel, in Mount Eden in the early 1890s. Several tuatara breeding programmes are active in New Zealand. Southland Museum and Art Gallery inInvercargill

Invercargill ( , ) is the southernmost and westernmost list of cities in New Zealand, city in New Zealand, and one of the Southernmost settlements, southernmost cities in the world. It is the commercial centre of the Southland Region, Southlan ...

was the first institution to have a tuatara breeding programme; starting in 1986 they bred ''S. punctatus'' and have focused on ''S. guntheri'' more recently.

Hamilton Zoo, Auckland Zoo and Wellington Zoo also breed tuatara for release into the wild. At Auckland Zoo in the 1990s it was discovered that tuatara have temperature-dependent sex determination

Temperature-dependent sex determination (TSD) is a type of environmental sex determination in which the temperatures experienced during embryonic/larval development determine the sex of the offspring. It is observed in reptiles and teleost fish, ...

.

The Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington (), also known by its shorter names "VUW" or "Vic", is a public university, public research university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of New Zealand Parliament, Parliament, and w ...

maintains a research programme into the captive breeding of tuatara, and the Pūkaha / Mount Bruce National Wildlife Centre keeps a pair and a juvenile.

The WildNZ Trust has a tuatara breeding enclosure at Ruawai. One notable captive breeding success story took place in January 2009, when all 11 eggs belonging to 110 year-old tuatara Henry and 80 year-old tuatara Mildred hatched. This story is especially remarkable as Henry required surgery to remove a cancerous tumour in order to successfully breed.

In January 2016, Chester Zoo

Chester Zoo is a zoo in Upton-by-Chester, Cheshire, England. Chester Zoo was opened in 1931 by George Mottershead and his family. The zoo is one of the UK's largest zoos at and the zoo has a total land holding of approximately .

Chester Zoo ...

, England, announced that they succeeded in breeding the tuatara in captivity for the first time outside its homeland.

Cultural significance

Tuatara feature in a number of indigenous legends, and are held as ''ariki'' (God forms). Tuatara are regarded as the messengers of Whiro, thegod

In monotheistic belief systems, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. In polytheistic belief systems, a god is "a spirit or being believed to have created, or for controlling some part of the un ...

of death and disaster, and Māori women are forbidden to eat them. Tuatara also indicate ''tapu'' (the borders of what is sacred and restricted), beyond which there is ''mana'', meaning there could be serious consequences if that boundary is crossed. Māori women would sometimes tattoo images of lizards, some of which may represent tuatara, near their genitals. Today, tuatara are regarded as a ''taonga

''Taonga'' or ''taoka'' (in South Island Māori) is a Māori-language word that refers to a treasured possession in Māori culture. It lacks a direct translation into English, making its use in the Treaty of Waitangi significant. The current ...

'' (special treasure) along with being viewed as the kaitiaki

Kaitiakitanga is a New Zealand Māori term used for the concept of guardianship of the sky, the sea, and the land. A kaitiaki is a guardian, and the process and practices of protecting and looking after the environment are referred to as k ...

(guardian) of knowledge.

The tuatara was featured on one side of the New Zealand five-cent coin, which was phased out in October 2006. ''Tuatara'' was also the name of the ''Journal of the Biological Society'' of Victoria University College and subsequently Victoria University of Wellington

Victoria University of Wellington (), also known by its shorter names "VUW" or "Vic", is a public university, public research university in Wellington, New Zealand. It was established in 1897 by Act of New Zealand Parliament, Parliament, and w ...

, published from 1947 until 1993. It has now been digitised by the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre, also at Victoria.

In popular culture

* A tuatara named "Tua" is prominently featured in the 2017 novel '' Turtles All the Way Down'' byJohn Green

John Michael Green (born August 24, 1977) is an American author and YouTuber. His books have more than 50 million copies in print worldwide, including ''The Fault in Our Stars'' (2012), which is one of the List of best-selling books#Bet ...

.

* There is a brand of New Zealand craft beer named after the Tuatara which particularly references the third eye in its advertising.

* In the season one finale of '' Abbott Elementary'' an old tuatara named Duster is used to represent themes of ageing and transition.

* In the 2023 animated movie '' Leo'', the main character is a tuatara named Leo.

See also

* * *Notes

References

Further reading

* * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{Taxonbar, from=Q163283 Endemic fauna of New Zealand Endemic reptiles of New Zealand Extant Late Pleistocene first appearances Māori culture Rhynchocephalia Taxa named by John Edward Gray