SMS Königsberg (1915) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

SMS was the

After the repair work was completed, steamed to the Baltic to take part in

After the repair work was completed, steamed to the Baltic to take part in

lead ship

The lead ship, name ship, or class leader is the first of a series or class of ships that are all constructed according to the same general design. The term is applicable to naval ships and large civilian vessels.

Large ships are very comple ...

of the of light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

s, built for the German (Imperial Navy) during World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. She took the name of the earlier , which had been destroyed during the Battle of Rufiji Delta

The Battle of the Rufiji Delta was fought in German East Africa (modern Tanzania) from October 1914–July 1915 during the First World War, between the German Navy's light cruiser , and a powerful group of British warships. The battle was a seri ...

in 1915. The new ship was laid down in 1914 at the AG Weser

Aktien-Gesellschaft "Weser" (abbreviated A.G. "Weser") was one of the major Germany, German shipbuilding companies, located at the Weser River in Bremen. Founded in 1872 it was finally closed in 1983. All together, A.G. „Weser" built about 1,4 ...

shipyard, launched in December 1915, and commissioned into the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German Imperial German Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpi ...

in August 1916. Armed with eight 15 cm SK L/45 guns, the ship had a top speed of .

saw action with the II Scouting Group; in September 1917 she participated in Operation Albion

Operation Albion was a German air, land and naval operation in the First World War, against Russian forces in October 1917 to occupy the West Estonian Archipelago. The campaign aimed to occupy the Baltic islands of Saaremaa (Ösel), Hii ...

, a large amphibious operation against the Baltic islands in the Gulf of Riga. Two months later, she was attacked by British battlecruisers

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of attr ...

in the Second Battle of Heligoland Bight

The Second Battle of Heligoland Bight, also the Action in the Helgoland Bight and the , was an inconclusive naval engagement fought between British and German squadrons on 17 November 1917 during the First World War.

Background

British minel ...

. She was hit by the battlecruiser , which caused a large fire and reduced her speed significantly. She escaped behind the cover of two German battleships, however. She was to have taken part in a sortie by the entire High Seas Fleet to attack the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from th ...

in the final days of the war, but unrest broke out that forced the cancellation of the plan. The ship carried Rear Admiral Hugo Meurer

Hugo Meurer (28 May 1869 – 4 January 1960) was a vice-admiral of the Kaiserliche Marine (German Imperial Navy). Meurer was the German naval officer who handled the negotiations of the internment of the German fleet in November 1918 at the end ...

to Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and Hoy. Its sheltered waters have played an impor ...

to negotiate the plan for interning the High Seas Fleet. was not interned, however, so she escaped the scuttling of the German fleet and was instead ceded to France as a war prize

A prize of war (also called spoils of war, bounty or booty) is a piece of enemy property or land seized by a belligerent party during or after a war or battle. This term was used nearly exclusively in terms of captured ships during the 18th and 1 ...

. She was renamed and served with the French Navy until 1933, before being scrapped in 1936.

Design

Design work began on the s before construction had begun on their predecessors of the . The new ships were broadly similar to the earlier cruisers, with only minor alterations in the arrangement of some components, including the forward broadside guns, which were raised a level to reduce their tendency to be washed out in heavy seas. They were also fitted with largerconning tower

A conning tower is a raised platform on a ship or submarine, often armoured, from which an officer in charge can conn (nautical), conn (conduct or control) the vessel, controlling movements of the ship by giving orders to those responsible for t ...

s.

was long overall and had a beam of and a draft

Draft, the draft, or draught may refer to:

Watercraft dimensions

* Draft (hull), the distance from waterline to keel of a vessel

* Draft (sail), degree of curvature in a sail

* Air draft, distance from waterline to the highest point on a v ...

of forward. She displaced normally and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. The ship had a fairly small superstructure

A superstructure is an upward extension of an existing structure above a baseline. This term is applied to various kinds of physical structures such as buildings, bridges, or ships.

Aboard ships and large boats

On water craft, the superstruct ...

that consisted primarily of a conning tower forward. She was fitted with a pair of pole masts, the fore just aft of the conning tower and the mainmast further aft. Her hull

Hull may refer to:

Structures

* The hull of an armored fighting vehicle, housing the chassis

* Fuselage, of an aircraft

* Hull (botany), the outer covering of seeds

* Hull (watercraft), the body or frame of a sea-going craft

* Submarine hull

Ma ...

had a long forecastle

The forecastle ( ; contracted as fo'c'sle or fo'c's'le) is the upper deck (ship), deck of a sailing ship forward of the foremast, or, historically, the forward part of a ship with the sailors' living quarters. Related to the latter meaning is t ...

that extended for the first third of the ship, stepping down to main deck

The main deck of a ship is the uppermost complete deck extending from bow to stern. A steel ship's hull may be considered a structural beam with the main deck forming the upper flange of a box girder and the keel forming the lower strength mem ...

level just aft of the conning tower, before reducing a deck further at the mainmast for a short quarterdeck

The quarterdeck is a raised deck behind the main mast of a sailing ship. Traditionally it was where the captain commanded his vessel and where the ship's colours were kept. This led to its use as the main ceremonial and reception area on bo ...

. The ship had a crew of 17 officers and 458 enlisted men.

Her propulsion system consisted of two sets of steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s that drove a pair of screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

s. Steam was provided by ten coal-fired and two oil-fired Marine-type water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-generat ...

s that were vented through three funnels

A funnel is a tube or pipe that is wide at the top and narrow at the bottom, used for guiding liquid or powder into a small opening.

Funnels are usually made of stainless steel, aluminium, glass, or plastic. The material used in its constructi ...

. The engines were rated to produce , which provided a top speed of . At a more economical cruising speed of , the ship had a range of .

The ship was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

of eight SK L/45 guns in single pedestal mounts. Two were placed side by side forward on the forecastle, four were located amidships, two on either side, and two were arranged in a superfiring pair aft. They were supplied with 1,040 rounds of ammunition, for 130 shells per gun. also carried two 8.8 cm SK L/45 anti-aircraft guns mounted on the centerline

Center line, centre line or centerline may refer to:

Sports

* Center line, marked in red on an ice hockey rink

* Centre line (football), a set of positions on an Australian rules football field

* Centerline, a line that separates the service cour ...

astern of the funnels. She was also equipped with a pair of torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s with eight torpedoes in deck-mounted swivel launchers amidships. She also carried 200 mines

Mine, mines, miners or mining may refer to:

Extraction or digging

*Miner, a person engaged in mining or digging

*Mining, extraction of mineral resources from the ground through a mine

Grammar

*Mine, a first-person English possessive pronoun

Mi ...

.

The ship was protected by a waterline armor belt

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

that was thick amidships. Protection for the ship's internals was reinforced with a curved armor deck that was 60 mm thick; the deck sloped downward at the sides and connected to the bottom edge of the belt armor. The conning tower had thick sides.

Service history

was ordered under the contract name " ", and waslaid down

Laying the keel or laying down is the formal recognition of the start of a ship's construction. It is often marked with a ceremony attended by dignitaries from the shipbuilding company and the ultimate owners of the ship.

Keel laying is one ...

at the AG Weser

Aktien-Gesellschaft "Weser" (abbreviated A.G. "Weser") was one of the major Germany, German shipbuilding companies, located at the Weser River in Bremen. Founded in 1872 it was finally closed in 1983. All together, A.G. „Weser" built about 1,4 ...

shipyard in Bremen

Bremen (Low German also: ''Breem'' or ''Bräm''), officially the City Municipality of Bremen (, ), is the capital of the States of Germany, German state of the Bremen (state), Free Hanseatic City of Bremen (), a two-city-state consisting of the c ...

on 22 August 1914, less than a month after the outbreak of World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. She was launched on 18 December 1915 without fanfare, after which fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work commenced. She was commissioned into the High Seas Fleet

The High Seas Fleet () was the battle fleet of the German Empire, German Imperial German Navy, Imperial Navy and saw action during the First World War. In February 1907, the Home Fleet () was renamed the High Seas Fleet. Admiral Alfred von Tirpi ...

on 12 August 1916, and on 29 October she joined II Scouting Group as its new flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

. The following day, (''KzS''—Captain at Sea) Ludwig von Reuter

Hans Hermann Ludwig von Reuter (9 February 1869 – 18 December 1943) was a German admiral who commanded the High Seas Fleet when it was interned at Scapa Flow in the north of Scotland at the end of World War I. On 21 June 1919 he ordered t ...

hoisted his flag aboard the ship and thereafter the ship participated in coastal defense patrols in the German Bight

The German Bight ( ; ; ); ; ; sometimes also the German Bay) is the southeastern bight of the North Sea bounded by the Netherlands and Germany to the south, and Denmark and Germany to the east (the Jutland peninsula). To the north and west i ...

. At the time, II Scouting Group also included the light cruisers , , , and . The ships were primarily tasked with supporting the defenses of the German North Sea

The North Sea lies between Great Britain, Denmark, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, Belgium, and France. A sea on the European continental shelf, it connects to the Atlantic Ocean through the English Channel in the south and the Norwegian Se ...

coast, as the fleet commander, (''VAdm''—Vice Admiral) Reinhard Scheer

Carl Friedrich Heinrich Reinhard Scheer (30 September 1863 – 26 November 1928) was an Admiral in the Imperial German Navy (''Kaiserliche Marine''). Scheer joined the navy in 1879 as an officer cadet and progressed through the ranks, commandi ...

had by that time abandoned offensive operations with the surface fleet in favor of the U-boat campaign

The U-boat campaign from 1914 to 1918 was the World War I naval campaign fought by German U-boats against the trade routes of the Allies, largely in the seas around the British Isles and in the Mediterranean, as part of a mutual blockade betwe ...

. In 1917, patrol duties were interrupted with individual and unit training in the Baltic Sea

The Baltic Sea is an arm of the Atlantic Ocean that is enclosed by the countries of Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Russia, Sweden, and the North European Plain, North and Central European Plain regions. It is the ...

from 22 February to 4 March and again from 20 May to 2 June. went to the shipyard in Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshaven'') is a coastal town in Lower Saxony, Germany. It is situated on the western side of the Jade Bight, a bay of the North Sea, and has a population of 76,089. Wilhelmsha ...

for repairs from 16 August to 9 September.

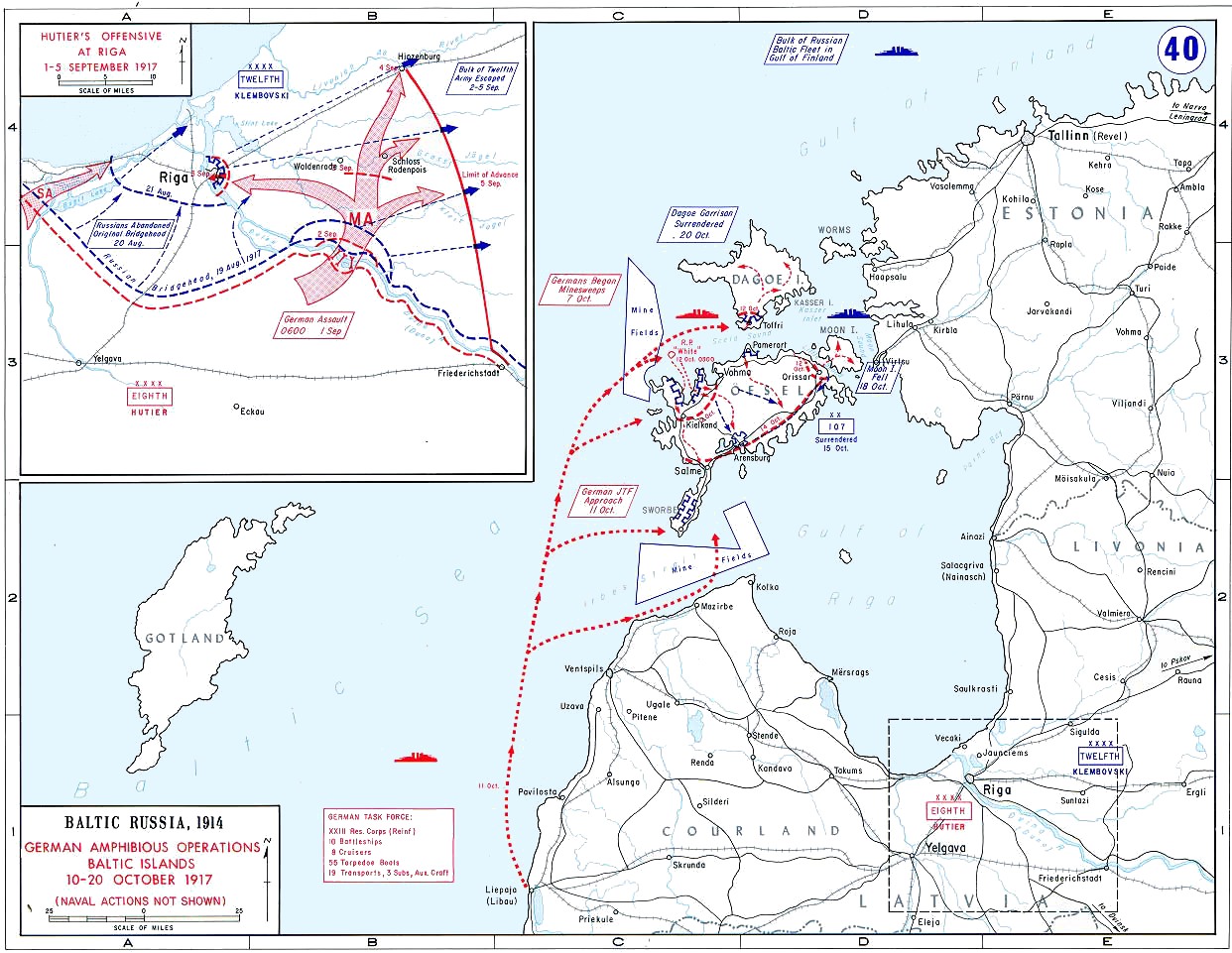

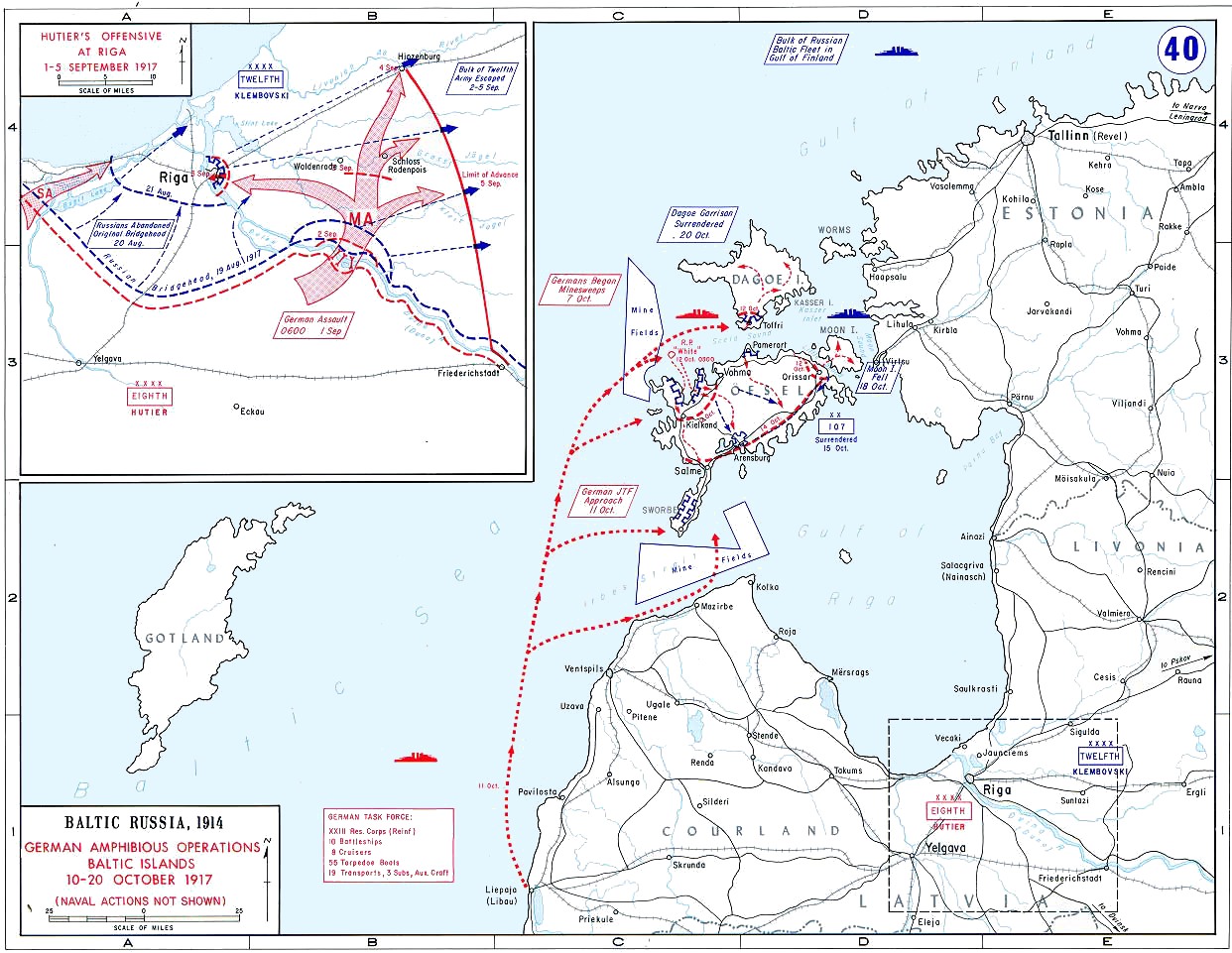

Operation Albion

After the repair work was completed, steamed to the Baltic to take part in

After the repair work was completed, steamed to the Baltic to take part in Operation Albion

Operation Albion was a German air, land and naval operation in the First World War, against Russian forces in October 1917 to occupy the West Estonian Archipelago. The campaign aimed to occupy the Baltic islands of Saaremaa (Ösel), Hii ...

, the amphibious assault on the islands in the Gulf of Riga

The Gulf of Riga, Bay of Riga, or Gulf of Livonia (, , ) is a bay of the Baltic Sea between Latvia and Estonia.

The island of Saaremaa (Estonia) partially separates it from the rest of the Baltic Sea. The main connection between the gulf and t ...

after the German Army captured the city during the Battle of Riga the month before. In addition, the German fleet sought to eliminate the Russian naval forces in the Gulf of Riga that still threatened German forces in the city. The (the Navy High Command) planned an operation to seize the Baltic island of Ösel

Saaremaa (; ) is the largest and most populous island in Estonia. Measuring , its population is 31,435 (as of January 2020). The main island of the West Estonian archipelago (Moonsund archipelago), it is located in the Baltic Sea, south of Hi ...

, and specifically the Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula. The ship joined the task force in Kiel on 23 September; she and the rest of II Scouting Group were tasked with escorting the troop transport Troop transport may be:

* Troopship

* Military Railway Service (United States)

* Military transport aircraft

A military transport aircraft, military cargo aircraft or airlifter is a military aircraft, military-owned transport aircraft used ...

s and was also made the flagship of IV Transport Group for the operation. (Lieutenant General) Ludwig von Estorff

Ludwig Gustav Adolf von Estorff (25 December 1859 – 5 October 1943) was a German military officer who notably served as a Schutztruppe commander in Africa; and later as an Imperial German Army general in World War I. He also was a recipient ...

, the commander of the 42nd Division, came aboard the ship during the cruise from Kiel. The invasion fleet stopped in Libau on 25 September to make final preparations, and on 11 October the Germans began the voyage to the Gulf.

The operation began on the morning of 12 October, when and the III Squadron ships engaged Russian positions in Tagga Bay while IV Squadron shelled Russian gun batteries on the Sworbe Peninsula on Saaremaa. steamed in Tagga Bay, where Estorff coordinated the operations of the German infantry, who quickly subdued Russian opposition. On 18–19 October, and the rest of II Scouting Group covered minesweepers

A minesweeper is a small warship designed to remove or detonate naval mines. Using various mechanisms intended to counter the threat posed by naval mines, minesweepers keep waterways clear for safe shipping.

History

The earliest known usage of ...

operating off the island of Dagö, but due to insufficient minesweepers and bad weather, the operation was postponed. On the 19th, , her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

, and the cruiser were sent to intercept two Russian torpedo boat

A torpedo boat is a relatively small and fast naval ship designed to carry torpedoes into battle. The first designs were steam-powered craft dedicated to ramming enemy ships with explosive spar torpedoes. Later evolutions launched variants of ...

s reported to be in the area. Reuter could not locate the vessels and so broke off the operation. By 20 October, the islands were under German control and the Russian naval forces had either been destroyed or forced to withdraw. The ordered the naval component to return to the North Sea. On 28 October, returned to Libau and proceeded back to the North Sea to resume her guard duties there with the rest of II Scouting Group.

Second Battle of Helgoland Bight

On 17 November, saw action at theSecond Battle of Helgoland Bight

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of Time in physics, time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the Internati ...

. Along with three other cruisers from II Scouting Group and a group of torpedo boats, escorted minesweepers clearing paths in minefields laid by the British in the area of Horns Rev

Horns Rev is a shallow sandy reef of glacial deposits in the eastern North Sea, about off the westernmost point of Denmark, Blåvands Huk.

. The dreadnought battleship

The dreadnought was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an effect when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her were referred to as "dreadnoughts", ...

s and stood by in distant support. Reuter had sent forward while he remained further back with the ships of II (Minesweeper Flotilla). The British 1st Cruiser Squadron

The First Cruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy squadron of cruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during World War I, then later as part of the Mediterranean during the Interwar period and World War II. It was first established in 1 ...

and the 6th Light Cruiser Squadron, supported by the 1st Battlecruiser Squadron

The First Battlecruiser Squadron was a Royal Navy squadron of battlecruisers that saw service as part of the Grand Fleet during the First World War. It was created in 1909 as the First Cruiser Squadron and was renamed in 1913 to First Battle Cr ...

, sortied to attack the operation. After the British opened fire, Reuter sought to use his ships to distract the British from the minesweepers while laying a smoke screen to cover their withdrawal. He also hoped to draw the British cruisers toward the two dreadnoughts.

As the battle developed, the British battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

s , , and joined the action. Once and arrived on the scene, Reuter launched a counterattack, during which ''Repulse'' scored a hit on with a shell at 10:58. The shell knocked all three of her funnels over and caused a fire, which significantly reduced her speed to . Reuter transferred to while withdrew so her crew could fight the fire; after the fire was suppressed she rejoined the German squadron. The presence of the German battleships led the British to break off the attack. Further German reinforcements arrived, including the battlecruisers and at 13:30 and the dreadnoughts and at 13:50.

With these forces assembled, the IV Battle Squadron

IV may refer to:

Businesses and organizations In the United States

*Immigration Voice, an activist organization

*Intellectual Ventures, a privately held intellectual property company

*InterVarsity Christian Fellowship

Elsewhere

*Federation of Aus ...

commander aboard , ''VAdm'' Wilhelm Souchon

Wilhelm Anton Souchon (; 2 June 1864 – 13 January 1946) was a German admiral in World War I. Souchon commanded the '' Kaiserliche Marine''s Mediterranean squadron in the early days of the war. His initiatives played a major part in the entry ...

, conducted a sweep for any remaining British vessels but could find none. At 15:00, the German ships withdrew from the area and anchored in the Schillig

Schillig () is a village in the Friesland district of Lower Saxony in Germany. It is situated on the west coast of Jade Bay and is north of the town of Wilhelmshaven

Wilhelmshaven (, ''Wilhelm's Harbour''; Northern Low Saxon: ''Willemshave ...

roadstead

A roadstead or road is a sheltered body of water where ships can lie reasonably safely at anchor without dragging or snatching.United States Army technical manual, TM 5-360. Port Construction and Rehabilitation'. Washington: United States. Gove ...

at 19:05. In the course of the battle, had suffered twenty-three casualties, of whom eight died. The commander of , Kurt Graßhoff

Kurt is a male given name in Germanic languages. ''Kurt'' or ''Curt'' originated as short forms of the Germanic Konrad/Conrad, depending on geographical usage, with meanings including counselor or advisor. Like Conrad, it can also a surname an ...

, was later criticized for failing to intervene quickly enough, leading to the development of new guidelines for placing battleships closer to minesweeper groups in the future. From 19 November to 15 December, was in the shipyard in Wilhelmshaven for repairs.

Later operations

Reuter came back aboard his flagship and resumed patrol duties in the German Bight on 17 December. On 20 January 1918, Reuter was replaced by ''KzS'' Magnus von Levetzow. II Scouting Group conducted exercises in the Baltic from 21 January to 7 February, after which they returned to the North Sea. They took part in the abortive fleet operation on 23–24 April to attack British convoys to Norway.I Scouting Group

The I Scouting Group () was a special reconnaissance unit within the German '' Kaiserliche Marine''. The unit was famously commanded by Admiral Franz von Hipper during World War I. The I Scouting Group was one of the most active formations in th ...

and II Scouting Group, along with the Second Torpedo-Boat Flotilla were to attack a heavily guarded British convoy to Norway, with the rest of the High Seas Fleet steaming in support. While steaming off the Utsira Lighthouse

Utsira Lighthouse () is a coastal lighthouse in Rogaland county, Norway. It sits on the western side of the island of Utsira in the municipality of Utsira.

History

The lighthouse was first lit in 1844, and listed as a protected site in 1999. ...

in southern Norway, had a serious accident with her machinery, which led Scheer to break off the operation and return to port.

From 10 to 13 May, and the rest of II Scouting Group escorted the minelayer while the latter vessel laid a defensive minefield to block British submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s form operating in the German Bight. The ships conducted additional training in the Baltic from 11 to 12 July. Levetzow left the unit later in July for the meetings that led to the formation of the (''SKL''—Maritime Warfare Command); during this period, s commander served as the commander of the group. Levetzow returned on 5 August, though he was replaced the following day by ''KzS'' Victor Harder, who also used as his flagship.

In October 1918, and the rest of II Scouting Group were to lead a final attack on the British navy. , , , and were to attack merchant shipping in the Thames estuary

The Thames Estuary is where the River Thames meets the waters of the North Sea, in the south-east of Great Britain.

Limits

An estuary can be defined according to different criteria (e.g. tidal, geographical, navigational or in terms of salinit ...

while , , and were to bombard targets in Flanders

Flanders ( or ; ) is the Dutch language, Dutch-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, la ...

, to draw out the British Grand Fleet

The Grand Fleet was the main battlefleet of the Royal Navy during the First World War. It was established in August 1914 and disbanded in April 1919. Its main base was Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands.

History

Formed in August 1914 from th ...

. Scheer, promoted to and placed in charge of the ''SKL'', and the new fleet commander Admiral Franz von Hipper

Franz Ritter von Hipper (born Franz Hipper; 13 September 1863 – 25 May 1932) was an admiral in the German Imperial Navy, (''Kaiserliche Marine'') who played an important role in the naval warfare of World War I. Franz von Hipper joined th ...

intended to inflict as much damage as possible on the British navy, in order to secure a better bargaining position for Germany, whatever the cost to the fleet. On the morning of 29 October 1918, the order was given to sail from Wilhelmshaven the following day. Starting on the night of 29 October, sailors on and then on several other battleships mutinied

Mutiny is a revolt among a group of people (typically of a military or a crew) to oppose, change, or remove superiors or their orders. The term is commonly used for insubordination by members of the military against an officer or superior, bu ...

. The unrest ultimately forced Hipper and Scheer to cancel the operation. When informed of the situation, the Kaiser stated, "I no longer have a navy."

While disorder consumed the bulk of the fleet, Andreas Michelsen

Andreas Heinrich Michelsen (19 February 1869 – 8 April 1932) was a German Vizeadmiral and military commander. During World War I, he commanded several torpedo boats and the submarine fleet, participated in the Battle of Jutland, as well as bein ...

organized a group to attack any British attempt to take advantage of the fleet's disarray. He pieced together a group of around sixty ships, including and several other light cruisers. On 9 November, reports of British activity in the German Bight prompted and several destroyers to make a sweep. After the reports proved false, the flotilla returned to Borkum

Borkum (; ) is an island and a municipality in the Leer District in Lower Saxony, northwestern Germany. It is situated east of Rottumeroog and west of Juist.

Geography

Borkum is bordered to the west by the Westerems strait (which forms the ...

, where they learned of the Kaiser's abdication. Following the Armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from t ...

that ended the fighting, took Rear Admiral Hugo Meurer

Hugo Meurer (28 May 1869 – 4 January 1960) was a vice-admiral of the Kaiserliche Marine (German Imperial Navy). Meurer was the German naval officer who handled the negotiations of the internment of the German fleet in November 1918 at the end ...

to Scapa Flow

Scapa Flow (; ) is a body of water in the Orkney Islands, Scotland, sheltered by the islands of Mainland, Graemsay, Burray,S. C. George, ''Jutland to Junkyard'', 1973. South Ronaldsay and Hoy. Its sheltered waters have played an impor ...

to negotiate with Admiral David Beatty, the commander of the Grand Fleet, for the place of internment of the German fleet. The ship arrived in Scapa Flow on 15 November, flying a white flag. The accepted arrangement was for the High Seas Fleet to meet the combined Allied fleet in the North Sea and proceed to the Firth of Forth

The Firth of Forth () is a firth in Scotland, an inlet of the North Sea that separates Fife to its north and Lothian to its south. Further inland, it becomes the estuary of the River Forth and several other rivers.

Name

''Firth'' is a cognate ...

before transferring to Scapa Flow, where they would be interned. Most of the High Seas Fleet's ships, including s sister ships , , and , were interned in the British naval base in Scapa Flow, under the command of Reuter. instead remained in Germany, returning Meurer from the negotiations with Beatty by the time the fleet left for internment.

Service with the French Navy

Following thescuttling of the German fleet in Scapa Flow

On 21 June 1919, shortly after the end of the First World War, the Imperial German Navy's High Seas Fleet was Scuttling, scuttled by its sailors while held off the harbour of the British Royal Navy base at Scapa Flow, in the Orkney Islands of ...

in June 1919, the Allied powers issued a demand on 1 November for the surrender of five cruisers, including , to replace vessels that had been sunk. was stricken from the naval register

A Navy Directory, Navy List or Naval Register is an official list of naval officers, their ranks and seniority, the ships which they command or to which they are appointed, etc., that is published by the government or naval authorities of a co ...

on 31 May 1920 and on 14 July, she left Germany in company with the cruisers , , and and four torpedo-boats. They arrived in Cherbourg

Cherbourg is a former Communes of France, commune and Subprefectures in France, subprefecture located at the northern end of the Cotentin peninsula in the northwestern French departments of France, department of Manche. It was merged into the com ...

, France, over the course of 19–20 July. She was ceded to France as "''A''" and was renamed on 6 October for service with the French fleet. She was not significantly modified in French service, the primary change being the replacement of her 8.8 cm guns with anti-aircraft guns. She also had her submerged torpedo tubes removed and the above-water tubes were replaced with versions. After entering service in November 1921, was assigned to the Atlantic Light Division, but she served here only briefly before being transferred to the French Mediterranean Fleet

The French Commander-in-Chief, Mediterranean, also known as CECMED (French for ''Commandant en chef pour la Méditerranée'') is a French Armed Forces regional commander. He commands the zone, the region and the Mediterranean maritime ''arrondiss ...

in early 1922. Here, she served with the other ex-German cruisers and and the ex-Austro-Hungarian in the 3rd Light Division (which was renamed the 2nd Light division in December 1926).

In October 1922 she carried Henry Franklin-Bouillon to Turkey to take part in the negotiations that led to the Treaty of Lausanne

The Treaty of Lausanne (, ) is a peace treaty negotiated during the Lausanne Conference of 1922–1923 and signed in the Palais de Rumine in Lausanne, Switzerland, on 24 July 1923. The treaty officially resolved the conflict that had initially ...

, which finally ended World War I for Turkey, which had spawned the Turkish War of Independence

, strength1 = May 1919: 35,000November 1920: 86,000Turkish General Staff, ''Türk İstiklal Harbinde Batı Cephesi'', Edition II, Part 2, Ankara 1999, p. 225August 1922: 271,000Celâl Erikan, Rıdvan Akın: ''Kurtuluş Savaşı tarih ...

of 1919–1922. In the mid-1920s, she participated in the Rif War

The Rif War (, , ) was an armed conflict fought from 1921 to 1926 between Spain (joined by France in 1924) and the Berber tribes of the mountainous Rif region of northern Morocco.

Led by Abd el-Krim, the Riffians at first inflicted several ...

. On 7 September 1925, she and the battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

and another ex-German cruiser, , supported a landing of French troops in North Africa. The three ships provided heavy gunfire support to the landing troops. In 1927, was transferred to the French Atlantic Fleet, though she served here only through 1928 when the entire division of ex-German cruisers was deactivated and stationed in Brest; this coincided with the commissioning of the new light cruisers. While there, had her aft funnels and her main mast removed. In 1929, the ship transferred to Landévennec

Landévennec (; ) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in north-western France.

Population

Geography

Landévennec is located on the Crozon peninsula, southeast of Brest. The river Aulne forms a natural boundary to the ea ...

, still in reserve. She was stricken from the naval register on 18 August 1933 and sold to ship breaker

Ship breaking (also known as ship recycling, ship demolition, ship scrapping, ship dismantling, or ship cracking) is a type of ship disposal involving the breaking up of ships either as a source of Interchangeable parts, parts, which can be sol ...

s in 1934. While in the breakers' yard in December that year, caught fire. Scrapping work was completed by 1936 at Brest.

Notes

Footnotes

Citations

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Konigsberg (1915), SMS Königsberg-class cruisers (1915) Ships built in Bremen (state) 1915 ships World War I cruisers of Germany Cruisers of the French Navy