Rosalind Franklin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Rosalind Elsie Franklin (25 July 192016 April 1958) was a British

. ''

What Rosalind Franklin truly contributed to the discovery of DNA's structure

''

See als

twitter thread

by Matthew Cobb, 25 April 2023

duplicate thread

by Nathaniel C. Comfort, 25 April 2023 Six weeks of intense efforts followed, as they tried to guess how the nucleotide bases pack into the core of the DNA structure, within the broad parameters set by the experimental data from the team at King's, that the structure should contain one or more helices with a repeat distance of 34 Angstroms, with probably ten elements in each repeat; and that the hydrophilic phosphate groups should be on the outside (though as Watson and Crick struggled to come up with a structure they at times departed from each of these assumptions during the process). Crick and Watson received a further impetus in the middle of February 1953 when Crick's thesis advisor,

Franklin left King's College London in mid-March 1953 for

Franklin left King's College London in mid-March 1953 for

* 2017

* 2017

Rue Rosalind Franklin

made. * 2017, DSM opened the Rosalind Franklin Biotechnology Center in

''The Rosalind Franklin Papers''

in "Profiles in Science", at

ceased publication in 1999

* * (In this article, Franklin cites Moffitt) * * * * * Downloadable free from doi site, or alternatively fro

The Rosalind Franklin Papers

collection at National Library of Medicine * * * * Reprint also available a

* * * * Article access per National Library of Medicine above * * Per National Library of Medicine above * Per National Library of Medicine * Per National Library of Medicine * Per National Library of Medicine * Per National Library of Medicine

Rosalind Franklin and the Double Helix

Photo Finish: Rosalind Franklin and the great DNA race

''The New Yorker'' October * * * * * * * * * Watson, J. Letter to ''

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a graduated scientist trained in the study of chemistry, or an officially enrolled student in the field. Chemists study the composition of ...

and X-ray crystallographer. Her work was central to the understanding of the molecular structures of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

(deoxyribonucleic acid), RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

(ribonucleic acid), viruses

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are found in almo ...

, coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

, and graphite

Graphite () is a Crystallinity, crystalline allotrope (form) of the element carbon. It consists of many stacked Layered materials, layers of graphene, typically in excess of hundreds of layers. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable ...

. Although her works on coal and viruses were appreciated in her lifetime, Franklin's contributions to the discovery of the structure of DNA were largely unrecognised during her life, for which Franklin has been variously referred to as the "wronged heroine", the "dark lady of DNA", the "forgotten heroine", a "feminist icon", and the " Sylvia Plath of molecular biology".

Franklin graduated in 1941 with a degree in natural sciences

Natural science or empirical science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer ...

from Newnham College, Cambridge

Newnham College is a women's constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college was founded in 1871 by a group organising Lectures for Ladies, members of which included philosopher Henry Sidgwick and suffragist campaigner Millicen ...

, and then enrolled for a PhD in physical chemistry

Physical chemistry is the study of macroscopic and microscopic phenomena in chemical systems in terms of the principles, practices, and concepts of physics such as motion, energy, force, time, thermodynamics, quantum chemistry, statistical mech ...

under Ronald George Wreyford Norrish, the 1920 Chair of Physical Chemistry at the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

. Disappointed by Norrish's lack of enthusiasm, she took up a research position under the British Coal Utilisation Research Association (BCURA) in 1942. The research on coal helped Franklin earn a PhD from Cambridge in 1945. Moving to Paris in 1947 as a (postdoctoral researcher) under Jacques Mering at the ''Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'État'', she became an accomplished X-ray crystallographer. After joining King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

in 1951 as a research associate, Franklin discovered some key properties of DNA, which eventually facilitated the correct description of the double helix

In molecular biology, the term double helix refers to the structure formed by base pair, double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double Helix, helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its Nuclei ...

structure of DNA. Owing to disagreement with her director, John Randall, and her colleague Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding ...

, Franklin was compelled to move to Birkbeck College

Birkbeck, University of London (formally Birkbeck College, University of London), is a public research university located in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. Established in 1823 as the London Mechanics' ...

in 1953.

Franklin is best known for her work on the X-ray diffraction images of DNA while at King's College London, particularly Photo 51 '

''Photo 51'' is an X-ray diffraction, X-ray based fiber diffraction image of a paracrystalline gel composed of DNA fiber taken by Raymond Gosling, a postgraduate student working under the supervision of Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin ...

, taken by her student Raymond Gosling

Raymond George Gosling (15 July 1926 – 18 May 2015) was a British scientist. While a PhD student at King's College, London he worked under the supervision of Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. The crystallographic experiments of Frankl ...

, which led to the discovery of the DNA double helix

In molecular biology, the term double helix refers to the structure formed by base pair, double-stranded molecules of nucleic acids such as DNA. The double Helix, helical structure of a nucleic acid complex arises as a consequence of its Nuclei ...

for which Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the Nucleic acid doub ...

, James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biology, molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper in ''Nature (journal), Nature'' proposing the Nucleic acid ...

, and Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding ...

shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine () is awarded yearly by the Nobel Assembly at the Karolinska Institute for outstanding discoveries in physiology or medicine. The Nobel Prize is not a single prize, but five separate prizes that, acco ...

in 1962. While Gosling actually took the famous Photo 51, Maurice Wilkins showed it to James Watson without her permission.

Watson suggested that Franklin would have ideally been awarded a Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

, along with Wilkins but it was not possible because the pre-1974 rule dictated that a Nobel prize could not be awarded posthumously unless the nomination had been made for a then-alive candidate before 1 February of the award year and Franklin died a few years before 1962 when the discovery of the structure of DNA was recognised by the Nobel committee.

Working under John Desmond Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular boo ...

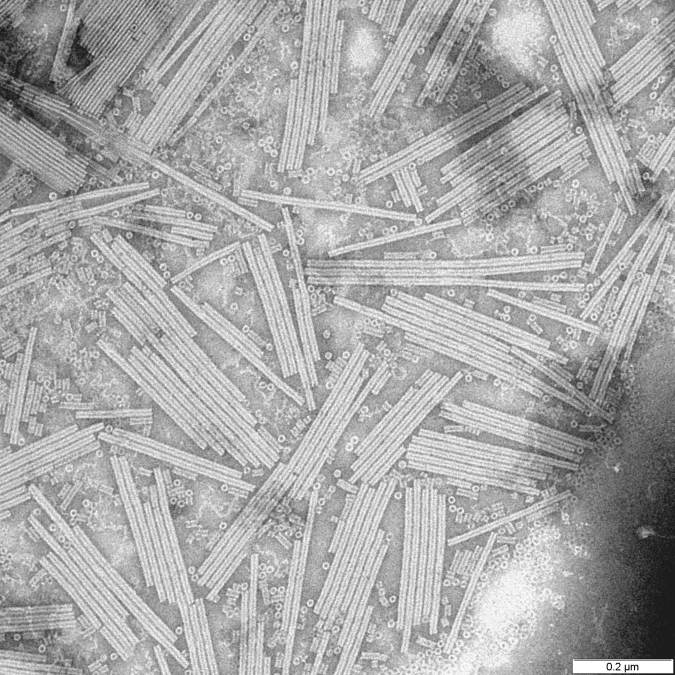

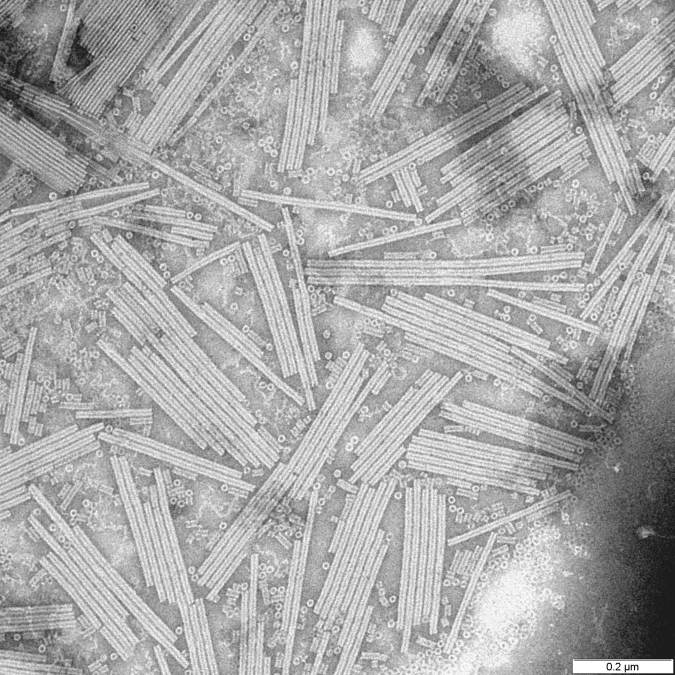

, Franklin led pioneering work at Birkbeck on the molecular structures of viruses. On the day before she was to unveil the structure of tobacco mosaic virus

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus species in the genus '' Tobamovirus'' that infects a wide range of plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characteris ...

at an international fair in Brussels, Franklin died of ovarian cancer at the age of 37 in 1958. Her team member Aaron Klug

Sir Aaron Klug (11 August 1926 – 20 November 2018) was a British biophysicist and chemist. He was a winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of biol ...

continued her research, winning the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982.

Early life

Franklin was born in 50 Chepstow Villas,Notting Hill

Notting Hill is a district of West London, England, in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. Notting Hill is known for being a wikt:cosmopolitan, cosmopolitan and multiculturalism, multicultural neighbourhood, hosting the annual Notting ...

, London, into an affluent and influential British Jewish family.

Family

Franklin's father,Ellis Arthur Franklin

Ellis Arthur Franklin (28 March 1894 – 16 January 1964) was an English merchant banker.

Early life

Franklin was born in Kensington, London into an affluent Anglo-Jewish family. He was the son of Arthur Ellis Franklin, a merchant banker an ...

, was a politically liberal London merchant banker who taught at the city's Working Men's College

The Working Men's College (also known as the St Pancras Working Men's College, WMC, The Camden College or WM College), is among the earliest adult education institutions established in the United Kingdom, and Europe's oldest extant centre for adu ...

, and her mother was Muriel Frances Waley. Rosalind was the elder daughter and the second child in the family of five children. David was the eldest brother while Colin, Roland

Roland (; ; or ''Rotholandus''; or ''Rolando''; died 15 August 778) was a Frankish military leader under Charlemagne who became one of the principal figures in the literary cycle known as the Matter of France. The historical Roland was mil ...

, and Jenifer were her younger siblings.Glynn, p. 1.

Franklin's paternal great-uncle was Herbert Samuel (later Viscount Samuel), who was the Home Secretary

The secretary of state for the Home Department, more commonly known as the home secretary, is a senior minister of the Crown in the Government of the United Kingdom and the head of the Home Office. The position is a Great Office of State, maki ...

in 1916 and the first practising Jew to serve in the British Cabinet.Maddox, p. 7. Her aunt, Helen Caroline Franklin, known in the family as Mamie, was married to Norman de Mattos Bentwich, who was the Attorney General

In most common law jurisdictions, the attorney general (: attorneys general) or attorney-general (AG or Atty.-Gen) is the main legal advisor to the government. In some jurisdictions, attorneys general also have executive responsibility for law enf ...

in the British Mandate of Palestine. Helen was active in trade union organisation and the women's suffrage movement

Women's suffrage is the women's rights, right of women to Suffrage, vote in elections. Several instances occurred in recent centuries where women were selectively given, then stripped of, the right to vote. In Sweden, conditional women's suffra ...

and was later a member of the London County Council

The London County Council (LCC) was the principal local government body for the County of London throughout its existence from 1889 to 1965, and the first London-wide general municipal authority to be directly elected. It covered the area today ...

.Maddox, p. 40. Franklin's uncle, Hugh Franklin, was another prominent figure in the suffrage movement, although his actions therein embarrassed the Franklin family. Rosalind's middle name, "Elsie", was in memory of Hugh's first wife, who died in the 1918 flu pandemic

The 1918–1920 flu pandemic, also known as the Great Influenza epidemic or by the common misnomer Spanish flu, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the Influenza A virus subtype H1N1, H1N1 subtype of the influenz ...

. Her family was actively involved with the Working Men's College

The Working Men's College (also known as the St Pancras Working Men's College, WMC, The Camden College or WM College), is among the earliest adult education institutions established in the United Kingdom, and Europe's oldest extant centre for adu ...

, where her father taught the subjects of electricity, magnetism, and the history of the Great War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

in the evenings, later becoming the vice principal.

Franklin's parents helped settle Jewish refugees from Europe who had escaped the Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

, particularly those from the ''Kindertransport

The ''Kindertransport'' (German for "children's transport") was an organised rescue effort of children from Nazi

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, total ...

''. They took in two Jewish children to their home, and one of them, a nine-year-old Austrian, Evi Eisenstädter, shared Jenifer's room.

Education

From early childhood, Franklin showed exceptional scholastic abilities. At age six, she joined her brother Roland at Norland Place School, a private day school in West London. At that time, her aunt Mamie (Helen Bentwich), described her to her husband: "Rosalind is alarmingly clever – she spends all her time doing arithmetic for pleasure, and invariably gets her sums right." Franklin also developed an early interest incricket

Cricket is a Bat-and-ball games, bat-and-ball game played between two Sports team, teams of eleven players on a cricket field, field, at the centre of which is a cricket pitch, pitch with a wicket at each end, each comprising two Bail (cr ...

and hockey

''Hockey'' is a family of List of stick sports, stick sports where two opposing teams use hockey sticks to propel a ball or disk into a goal. There are many types of hockey, and the individual sports vary in rules, numbers of players, apparel, ...

. At age nine, she entered a boarding school, Lindores School for Young Ladies in Sussex. The school was near the seaside, and the family wanted a good environment for Franklin's delicate health.

Franklin was 11 when she went to St Paul's Girls' School in Hammersmith

Hammersmith is a district of West London, England, southwest of Charing Cross. It is the administrative centre of the London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham, and identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

It ...

, west London, one of the few girls' schools in London that taught physics and chemistry. At St Paul's, she excelled in science, Latin, and sports. Franklin also learned German, and became fluent in French, a language she would later find useful. Franklin topped her classes, and won annual awards. Her only educational weakness was in music, for which the school music director, the composer Gustav Holst

Gustav Theodore Holst (born Gustavus Theodore von Holst; 21 September 1874 – 25 May 1934) was an English composer, arranger and teacher. Best known for his orchestral suite ''The Planets'', he composed many other works across a range ...

, once called upon her mother to enquire whether she might have suffered from hearing problems or tonsillitis

Tonsillitis is inflammation of the tonsils in the upper part of the throat. It can be acute or chronic. Acute tonsillitis typically has a rapid onset. Symptoms may include sore throat, fever, enlargement of the tonsils, trouble swallowing, and en ...

. With six distinctions, Franklin passed her matriculation in 1938, winning a scholarship for university, the School Leaving Exhibition of £30 a year for three years, and £5 from her grandfather. Franklin's father asked her to give the scholarship to a deserving refugee student.

Cambridge and World War II

Franklin went toNewnham College, Cambridge

Newnham College is a women's constituent college of the University of Cambridge.

The college was founded in 1871 by a group organising Lectures for Ladies, members of which included philosopher Henry Sidgwick and suffragist campaigner Millicen ...

, in 1938 and studied chemistry within the Natural Sciences Tripos. There, she met the spectroscopist Bill Price, who worked with her as a laboratory demonstrator and who later became one of her senior colleagues at King's College London. In 1941 Franklin was awarded second-class honours

The British undergraduate degree classification system is a grading structure used for undergraduate degrees or bachelor's degrees and integrated master's degrees in the United Kingdom. The system has been applied, sometimes with significant var ...

from her final exams. The distinction was accepted as a bachelor's degree in qualifications for employment. Cambridge began awarding titular BA and MA degrees to women from 1947 and the previous women graduates retroactively received these earned degrees. In her last year at Cambridge, Franklin met a French refugee Adrienne Weill, a former student of Marie Curie

Maria Salomea Skłodowska-Curie (; ; 7 November 1867 – 4 July 1934), known simply as Marie Curie ( ; ), was a Polish and naturalised-French physicist and chemist who conducted pioneering research on radioactivity.

She was List of female ...

, who had a huge influence on her life and career and who helped her to improve her conversational French.

Franklin was awarded a research fellowship at Newnham College, with which she joined the physical chemistry laboratory of the University of Cambridge

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

to work under Ronald George Wreyford Norrish, who later won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

The Nobel Prize in Chemistry () is awarded annually by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to scientists in the various fields of chemistry. It is one of the five Nobel Prizes established by the will of Alfred Nobel in 1895, awarded for outst ...

. In her one year of work there, Franklin did not have much success. As described by his biographer, Norrish was "obstinate and almost perverse in argument, overbearing and sensitive to criticism". He could not decide upon the assignment of work for her. At that time Norrish was succumbing due to heavy drinking. Franklin wrote that he made her despise him completely.

Resigning from Norrish's Lab, Franklin fulfilled the requirements of the National Service Acts by working as an assistant research officer at the British Coal Utilisation Research Association (BCURA) in 1942. The BCURA was located on the Coombe Springs Estate near Kingston upon Thames

Kingston upon Thames, colloquially known as Kingston, is a town in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames, south-west London, England. It is situated on the River Thames, south-west of Charing Cross. It is an ancient market town, notable as ...

near the southwestern boundary of London. Norrish acted as advisor to the military at BCURA. John G. Bennett was the director. Marcello Pirani and Victor Goldschmidt

Victor Moritz Goldschmidt (27 January 1888 – 20 March 1947) was a Norwegian mineralogist considered (together with Vladimir Vernadsky) to be the founder of modern geochemistry and crystal chemistry, developer of the Goldschmidt Classificatio ...

, both refugees from the Nazis, were consultants and lectured at BCURA while Franklin worked there.

During her BCURA research Franklin initially stayed at Adrienne Weill's boarding house in Cambridge until her cousin, Irene Franklin, proposed that they share living quarters at a vacated house in Putney

Putney () is an affluent district in southwest London, England, in the London Borough of Wandsworth, southwest of Charing Cross. The area is identified in the London Plan as one of 35 major centres in Greater London.

History

Putney is an ...

that belonged to her uncle. With Irene, Rosalind volunteered as an Air Raid Warden and regularly made patrols to see the welfare of people during air raids.

Franklin studied the porosity

Porosity or void fraction is a measure of the void (i.e. "empty") spaces in a material, and is a fraction of the volume of voids over the total volume, between 0 and 1, or as a percentage between 0% and 100%. Strictly speaking, some tests measure ...

of coal using helium to determine its density. Through this, she discovered the relationship between the fine constrictions in the pores of coals and the permeability of the porous space. By concluding that substances were expelled in order of molecular size as temperature increased, she helped classify coals and accurately predict their performance for fuel purposes and for production of wartime devices such as gas masks

A gas mask is a piece of personal protective equipment used to protect the wearer from inhaling airborne pollutants and toxic gases. The mask forms a sealed cover over the nose and mouth, but may also cover the eyes and other vulnerable soft ...

. This work was the basis of Franklin's PhD thesis ''The physical chemistry of solid organic colloid

A colloid is a mixture in which one substance consisting of microscopically dispersed insoluble particles is suspended throughout another substance. Some definitions specify that the particles must be dispersed in a liquid, while others exte ...

s with special reference to coal'' for which the University of Cambridge awarded her a PhD in 1945. It was also the basis of several papers.

Career and research

Paris

With World War II ending in 1945, Franklin asked Adrienne Weill for help and to let her know of job openings for "a physical chemist who knows very little physical chemistry, but quite a lot about the holes in coal." At a conference in the autumn of 1946, Weill introduced Franklin to Marcel Mathieu, a director of theCentre national de la recherche scientifique

The French National Centre for Scientific Research (, , CNRS) is the French state research organisation and is the largest fundamental science agency in Europe.

In 2016, it employed 31,637 staff, including 11,137 tenured researchers, 13,415 eng ...

(CNRS), the network of institutes that comprises the major part of the scientific research laboratories supported by the French government. This led to her appointment with Jacques Mering at the Laboratoire Central des Services Chimiques de l'État in Paris. Franklin joined the ''labo'' (as referred to by the staff) of Mering on 14 February 1947 as one of the fifteen ''chercheurs'' (researchers).

Mering was an X-ray crystallographer who applied X-ray diffraction

X-ray diffraction is a generic term for phenomena associated with changes in the direction of X-ray beams due to interactions with the electrons around atoms. It occurs due to elastic scattering, when there is no change in the energy of the waves. ...

to the study of rayon and other amorphous substances, in contrast to the thousands of regular crystals that had been studied by this method for many years. He taught her the practical aspects of applying X-ray crystallography to amorphous substances. This presented new challenges in the conduct of experiments and the interpretation of results. Franklin applied them to further problems related to coal and to other carbonaceous materials, in particular the changes to the arrangement of atoms when these are converted to graphite. She published several further papers on this work which has become part of the mainstream of the physics and chemistry of coal and carbon. Franklin coined the terms graphitising and non-graphitising carbon. The coal work was covered in a 1993 monograph, and in the regularly published textbook ''Chemistry and Physics of Carbon''. Mering continued the study of carbon in various forms, using X-ray diffraction and other methods.

King's College London

In 1950 Franklin was granted a three-year Turner & Newall Fellowship to work atKing's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

. In January 1951 she started working as a research associate in the Medical Research Council's (MRC) Biophysics Unit, directed by John Randall. She was originally appointed to work on X-ray diffraction of protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s and lipid

Lipids are a broad group of organic compounds which include fats, waxes, sterols, fat-soluble vitamins (such as vitamins A, D, E and K), monoglycerides, diglycerides, phospholipids, and others. The functions of lipids include storing ...

s in solution, but Randall redirected Franklin's work to DNA fibres because of new developments in the field, and she was to be the only experienced experimental diffraction researcher at King's at the time. Randall made this reassignment, even before Franklin started working at King's, because of the pioneering work by DNA researcher Maurice Wilkins

Maurice Hugh Frederick Wilkins (15 December 1916 – 5 October 2004) was a New Zealand-born British biophysicist and Nobel laureate whose research spanned multiple areas of physics and biophysics, contributing to the scientific understanding ...

, and he reassigned Raymond Gosling

Raymond George Gosling (15 July 1926 – 18 May 2015) was a British scientist. While a PhD student at King's College, London he worked under the supervision of Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. The crystallographic experiments of Frankl ...

, the graduate student who had been working with Wilkins, to be her assistant.

In 1950 Swiss chemist Rudolf Signer in Berne prepared a highly purified DNA sample from calf thymus

The thymus (: thymuses or thymi) is a specialized primary lymphoid organ of the immune system. Within the thymus, T cells mature. T cells are critical to the adaptive immune system, where the body adapts to specific foreign invaders. The thymus ...

. He freely distributed the DNA sample, later referred to as the Signer DNA, in early May 1950 at the meeting of the Faraday Society in London, and Wilkins was one of the recipients. Even using crude equipment, Wilkins and Gosling had obtained a good-quality diffraction picture of the DNA sample which sparked further interest in this molecule.Professor Raymond Gosling, DNA scientist – obituary. ''

The Daily Telegraph

''The Daily Telegraph'', known online and elsewhere as ''The Telegraph'', is a British daily broadsheet conservative newspaper published in London by Telegraph Media Group and distributed in the United Kingdom and internationally. It was found ...

''. 22 May 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2019. But Randall had not indicated to them that he had asked Franklin to take over both the DNA diffraction work and guidance of Gosling's thesis. It was while Wilkins was away on holiday that Randall, in a letter in December 1950, assured Franklin that "as far as the experimental X-ray effort there would be for the moment only yourself and Gosling." Randall's lack of communication about this reassignment significantly contributed to the well-documented friction that developed between Wilkins and Franklin. When Wilkins returned, he handed over the Signer DNA and Gosling to Franklin.

Franklin, now working with Gosling, started to apply her expertise in X-ray diffraction techniques to the structure of DNA. She used a new fine-focus X-ray tube and microcamera ordered by Wilkins, but which she refined, adjusted and focused carefully. Drawing upon her physical chemistry background, a critical innovation Franklin applied was making the camera chamber that could be controlled for its humidity

Humidity is the concentration of water vapor present in the air. Water vapor, the gaseous state of water, is generally invisible to the human eye. Humidity indicates the likelihood for precipitation (meteorology), precipitation, dew, or fog t ...

using different saturated salt solutions. When Wilkins enquired about this improved technique, she replied in terms which offended him as she had "an air of cool superiority".

Franklin's habit of intensely looking people in the eye while being concise, impatient and direct unnerved many of her colleagues. In stark contrast, Wilkins was very shy, and slowly calculating in speech while he avoided looking anyone directly in the eye.Elkin p. 45. With the ingenious humidity-controlling camera, Franklin was soon able to produce X-ray images of better quality than those of Wilkins. She immediately discovered that the DNA sample could exist in two forms: at a relative humidity higher than 75%, the DNA fibre became long and thin; when it was drier, it became short and fat. She originally referred to the former as "wet" and the latter as "crystalline."

On the structure of the crystalline DNA, Franklin first recorded the analysis in her notebook, which reads: "Evidence for spiral eaning helicalstructure. Straight chain untwisted is highly improbable. Absence of reflections on meridian in χtalline rystallineform suggests spiral structure." An immediate discovery from this was that the phosphate group

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosp ...

lies outside the main DNA chain; Franklin, however could not make out whether there could be two or three chains. She presented their data at a lecture in November 1951, in King's College London. In her lecture notes, Franklin wrote the following:The results suggest a helical structure (which must be very closely packed) containing 2, 3 or 4 co-axial nucleic acid chains per helical unit, and having the phosphate groups near the outside.Franklin then named " A" and "B" respectively for the "crystalline" and "wet" forms. (The biological functions of A-DNA were discovered only 60 years later.) Because of the intense personality conflict developing between Franklin and Wilkins, Randall divided the work on DNA. Franklin chose the data rich "A" form while Wilkins selected the "B" form.Maddox, p. 155.Wilkins, p. 158. By the end of 1951 it became generally accepted at King's that the B-DNA was a

helix

A helix (; ) is a shape like a cylindrical coil spring or the thread of a machine screw. It is a type of smooth space curve with tangent lines at a constant angle to a fixed axis. Helices are important in biology, as the DNA molecule is for ...

, but after Franklin had recorded an asymmetrical image in May 1952, Franklin became unconvinced that the A-DNA was a helix.Wilkins, p. 176. In July 1952, as a practical joke on Wilkins (who frequently expressed his view that both forms of DNA were helical), Franklin and Gosling produced a funeral notice regretting the 'death' of helical A-DNA, which runs:It is with great regret that we have to announce the death, on Friday 18th July 1952 of DNA helix (crystalline). Death followed a protracted illness which an intensive course of Besselised eferring to Bessel function that was used to analyse the X-ray diffraction patterns">Bessel_function.html" ;"title="eferring to Bessel function">eferring to Bessel function that was used to analyse the X-ray diffraction patternsinjections had failed to relieve. A memorial service will be held next Monday or Tuesday. It is hoped that Dr M H F Wilkins will speak in memory of the late helix. [Signed Rosalind Franklin and Raymond Gosling.]During 1952 they worked at applying the Patterson function to the X-ray pictures of DNA they had produced. This was a long and labour-intensive approach but would yield significant insight into the structure of the molecule. Franklin was fully committed to experimental data and was sternly against theoretical or model buildings, as she said, "We are not going to speculate, we are going to wait, we are going to let the spots on this photograph tell us what the NAstructure is." The X-ray diffraction pictures, including the landmark ''

Photo 51 '

''Photo 51'' is an X-ray diffraction, X-ray based fiber diffraction image of a paracrystalline gel composed of DNA fiber taken by Raymond Gosling, a postgraduate student working under the supervision of Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin ...

'' taken by Gosling at this time, have been called by John Desmond Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular boo ...

as "amongst the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken".Maddox, p. 153.

By January 1953 Franklin had reconciled her conflicting data, concluding that both DNA forms had two helices, and had started to write a series of three draft manuscripts, two of which included a double-helical DNA backbone (see below). Franklin's two A-DNA manuscripts reached ''Acta Crystallographica

''Acta Crystallographica'' is a series of peer-reviewed scientific journals, with articles centred on crystallography, published by the International Union of Crystallography (IUCr). Originally established in 1948 as a single journal called ''A ...

'' in Copenhagen

Copenhagen ( ) is the capital and most populous city of Denmark, with a population of 1.4 million in the Urban area of Copenhagen, urban area. The city is situated on the islands of Zealand and Amager, separated from Malmö, Sweden, by the ...

on 6 March 1953, the day before Crick and Watson had completed their model on B-DNA. Franklin must have mailed them while the Cambridge team was building their model, and certainly had written them before she knew of their work.Maddox, p. 199. On 8 July 1953 Franklin modified one of these "in proof" ''Acta'' articles, "in light of recent work" by the King's and Cambridge research teams.

The third draft paper was on the B-DNA, dated 17 March 1953, which was discovered years later amongst her papers, by Franklin's Birkbeck colleague, Aaron Klug

Sir Aaron Klug (11 August 1926 – 20 November 2018) was a British biophysicist and chemist. He was a winner of the 1982 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of biol ...

. He then published in 1974 an evaluation of the draft's close correlation with the third of the original trio of 25 April 1953 ''Nature'' DNA articles. Klug designed this paper to complement the first article he had written in 1968 defending Franklin's significant contribution to DNA structure. Klug had written this first article in response to the incomplete picture of Franklin's work depicted in James Watson

James Dewey Watson (born April 6, 1928) is an American molecular biology, molecular biologist, geneticist, and zoologist. In 1953, he co-authored with Francis Crick the academic paper in ''Nature (journal), Nature'' proposing the Nucleic acid ...

's 1968 memoir, ''The Double Helix

''The Double Helix: A Personal Account of the Discovery of the Structure of DNA'' is an autobiographical account of the discovery of the double helix structure of DNA written by James D. Watson and published in 1968. It has earned both critical ...

''.

As vividly described by Watson, he travelled to King's on 30 January 1953 carrying a preprint of Linus Pauling

Linus Carl Pauling ( ; February 28, 1901August 19, 1994) was an American chemist and peace activist. He published more than 1,200 papers and books, of which about 850 dealt with scientific topics. ''New Scientist'' called him one of the 20 gre ...

's incorrect proposal for DNA structure. Since Wilkins was not in his office, Watson went to Franklin's lab with his urgent message that they should all collaborate before Pauling discovered his error. The unimpressed Franklin became angry when Watson suggested she did not know how to interpret her own data. Watson hastily retreated, backing into Wilkins who had been attracted by the commotion. Wilkins commiserated with his harried friend and then showed Watson Franklin's DNA X-ray image. Watson, in turn, showed Wilkins a prepublication manuscript by Pauling and Robert Corey

Robert Brainard Corey (August 19, 1897 – April 23, 1971) was an American biochemist, mostly known for his role in discovery of the α-helix and the β-sheet with Linus Pauling. Also working with Pauling was Herman Branson. Their discoveries ...

, which contained a DNA structure remarkably like their first incorrect model.

Discovery of DNA structure

In November 1951 James Watson and Francis Crick of theCavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is named ...

in Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209, the University of Cambridge is the List of oldest universities in continuous operation, wo ...

had started to build a molecular model

A molecular model is a physical model of an atomistic system that represents molecules and their processes. They play an important role in understanding chemistry and generating and testing hypotheses. The creation of mathematical models of mole ...

of the B-DNA using data similar to that available to both teams at King's. Based on Franklin's lecture in November 1951 that DNA was helical with either two or three stands, they constructed a triple-helix model, which was immediately proven to be flawed. In particular, the model had the phosphate backbone of the molecules forming a central core. But Franklin pointed out that the progressive solubility of DNA crystals in water meant that the strongly hydrophilic

A hydrophile is a molecule or other molecular entity that is attracted to water molecules and tends to be dissolved by water.Liddell, H.G. & Scott, R. (1940). ''A Greek-English Lexicon'' Oxford: Clarendon Press.

In contrast, hydrophobes are n ...

phosphate groups were likely to be on the outside of the structure; while the experimental failure to titrate the CO- and NH2 groups of the bases meant that these were more likely to be inaccessible in the interior of the structure. This initial setback led Watson and Crick to focus on other topics for most of the next year.

Model building had been applied successfully in the elucidation of the structure of the alpha helix

An alpha helix (or α-helix) is a sequence of amino acids in a protein that are twisted into a coil (a helix).

The alpha helix is the most common structural arrangement in the Protein secondary structure, secondary structure of proteins. It is al ...

by Linus Pauling in 1951, but Franklin was opposed to prematurely building theoretical models, until sufficient data were obtained to properly guide the model building. She took the view that building a model was to be undertaken only after enough of the structure was known. Franklin's conviction was only reinforced when Pauling and Corey also came up with an erroneous triple-helix model in their late-1952 paper (published in February 1953). Ever cautious, Franklin wanted to eliminate misleading possibilities. Photographs of her Birkbeck work table show that Franklin routinely used small molecular models of DNA, although certainly not ones on the grand scale successfully used at Cambridge.

The arrival in Cambridge of Linus Pauling's flawed paper in January 1953 prompted the head of the Cavendish Laboratory, Lawrence Bragg

Sir William Lawrence Bragg (31 March 1890 – 1 July 1971) was an Australian-born British physicist who shared the 1915 Nobel Prize in Physics with his father William Henry Bragg "for their services in the analysis of crystal structure by m ...

, to encourage Watson and Crick to resume their own model building. Cobb, Matthew and Comfort, Nathaniel (25 April 2023)What Rosalind Franklin truly contributed to the discovery of DNA's structure

''

Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'', 616 657–660See als

twitter thread

by Matthew Cobb, 25 April 2023

duplicate thread

by Nathaniel C. Comfort, 25 April 2023 Six weeks of intense efforts followed, as they tried to guess how the nucleotide bases pack into the core of the DNA structure, within the broad parameters set by the experimental data from the team at King's, that the structure should contain one or more helices with a repeat distance of 34 Angstroms, with probably ten elements in each repeat; and that the hydrophilic phosphate groups should be on the outside (though as Watson and Crick struggled to come up with a structure they at times departed from each of these assumptions during the process). Crick and Watson received a further impetus in the middle of February 1953 when Crick's thesis advisor,

Max Perutz

Max Ferdinand Perutz (19 May 1914 – 6 February 2002) was an Austrian-born British molecular biologist, who shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Chemistry with John Kendrew, for their studies of the structures of haemoglobin and myoglobin. He went ...

, gave Crick a copy of a report written for a Medical Research Council biophysics committee visit to King's in December 1952, containing many of Franklin's crystallographic calculations. This decisively confirmed the 34 Angstrom repeat distance; and established that the structure had C2 symmetry, immediately confirming to Crick that it must contain an equal number of parallel and anti-parallel strands running in opposite directions.

Since Franklin had decided to transfer to Birkbeck College and Randall had insisted that all DNA work must stay at King's, Wilkins was given copies of Franklin's diffraction photographs by Gosling. By 28 February 1953 Watson and Crick felt they had solved the problem enough for Crick to proclaim (in the local pub) that they had "found the secret of life". However, they knew they must complete their model before they could be certain. The closeness of fit to the experimental data from King's was an essential corroboration of the structure.

Watson and Crick finished building their model on 7 March 1953, a day before they received a letter from Wilkins stating that Franklin was finally leaving and they could put "all hands to the pump". This was also one day after Franklin's two A-DNA papers had reached ''Acta Crystallographica''. Wilkins came to see the model the following week, according to Franklin's biographer Brenda Maddox, on 12 March, and allegedly informed Gosling on his return to King's.Maddox, p. 207.

One of the most critical and overlooked moments in DNA research was how and when Franklin realised and conceded that B-DNA was a double-helical molecule. When Klug first examined Franklin's documents after her death, he initially came to an impression that Franklin was not convinced of the double-helical nature until the knowledge of the Cambridge model. But Klug later discovered the original draft of the manuscript (dated 17 March 1953) from which it became clear that Franklin had already resolved the correct structure. The news of Watson–Crick model reached King's the next day, 18 March, suggesting that Franklin would have learned of it much later since she had moved to Birkbeck. Further scrutiny of her notebook revealed that Franklin had already thought of the helical structure for B-DNA in February 1953 but was not sure of the number of strands, as she wrote: "Evidence for 2-chain (or 1-chain helix)."Olby, p. 418. Her conclusion on the helical nature was evident, though she failed to understand the complete organisation of the DNA strands, as the possibility of two strands running in opposite directions did not occur to her.

Towards the end of February Franklin began to work out the indications of double strands, as she noted: "Structure B does not fit single helical theory, even for low layer-lines." It soon dawned to her that the B-DNA and A-DNA were structurally similar, and perceived A-DNA as an "unwound version" of B-DNA. Franklin and Gosling wrote a five-paged manuscript on 17 March titled "A Note on Molecular Configuration of Sodium Thymonucleate." After the Watson–Crick model was known, there appeared to be only one (hand-written) modification after the typeset at the end of the text which states that their data was consistent with the model, and appeared as such in the trio of the 25th of April 1953 ''Nature

Nature is an inherent character or constitution, particularly of the Ecosphere (planetary), ecosphere or the universe as a whole. In this general sense nature refers to the Scientific law, laws, elements and phenomenon, phenomena of the physic ...

'' articles; the other modification being a deletion of "A Note on" from the title. eproduction with interpretation: /ref>

As Franklin considered the double helix, she also realised that the structure would not depend on the detailed order of the bases, and noted that "an infinite variety of nucleotide sequences would be possible to explain the biological specificity of DNA". However she did not yet see the complementarity of the base-pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DNA ...

ing – Crick and Watson's breakthrough of 28 February, with all its biological significance; nor indeed at this point did she have the correct structures of the bases, so even if she had tried, she would not have been able to make a satisfactory structure. Science historians Nathaniel C. Comfort, of Johns Hopkins University

The Johns Hopkins University (often abbreviated as Johns Hopkins, Hopkins, or JHU) is a private university, private research university in Baltimore, Maryland, United States. Founded in 1876 based on the European research institution model, J ...

, and Matthew Cobb, of the University of Manchester

The University of Manchester is a public university, public research university in Manchester, England. The main campus is south of Manchester city centre, Manchester City Centre on Wilmslow Road, Oxford Road. The University of Manchester is c ...

, explained that "She did not have time to make these final leaps, because Watson and Crick beat her to the answer."

Weeks later, on 10 April, Franklin wrote to Crick for permission to see their model. Franklin retained her scepticism for premature model building even after seeing the Watson–Crick model, and remained unimpressed. She is reported to have commented, "It's very pretty, but how are they going to prove it?" As an experimental scientist, Franklin seems to have been interested in producing far greater evidence before publishing-as-proven a proposed model. Accordingly, her response to the Watson–Crick model was in keeping with her cautious approach to science.

Crick and Watson published their model in ''Nature'' on 25 April 1953, in an article describing the double-helical structure of DNA with only a footnote acknowledging "having been stimulated by a general knowledge of Franklin and Wilkins' 'unpublished' contribution." Actually, although it was the bare minimum, they had just enough specific knowledge of Franklin and Gosling's data upon which to base their model. As a result of a deal struck by the two laboratory directors, articles by Wilkins and Franklin, which included their X-ray diffraction data, were modified and then published second and third in the same issue of ''Nature'', seemingly only in support of the Crick and Watson theoretical paper which proposed a model for the B-DNA. Most of the scientific community hesitated several years before accepting the double-helix proposal. At first mainly geneticists embraced the model because of its obvious genetic implications.

Birkbeck College

Franklin left King's College London in mid-March 1953 for

Franklin left King's College London in mid-March 1953 for Birkbeck College

Birkbeck, University of London (formally Birkbeck College, University of London), is a public research university located in London, England, and a member institution of the University of London. Established in 1823 as the London Mechanics' ...

, in a move that had been planned for some time and that she described (in a letter to Adrienne Weill in Paris) as "moving from a palace to the slums ... but pleasanter all the same". She was recruited by physics department chair John Desmond Bernal, a crystallographer who was a communist, known for promoting female crystallographers. Her new laboratories were housed in 21 Torrington Square, one of a pair of dilapidated and cramped Georgian houses containing several different departments; Franklin frequently took Bernal to task over the careless attitudes of some of the other laboratory staff, notably on one occasion after workers in the Pharmacy department flooded her first-floor laboratory with water.

Despite the parting words of Bernal to stop her interest in nucleic acids, Franklin helped Gosling to finish his thesis, although she was no longer his official supervisor. Together, they published the first evidence of double helix in the A form of DNA in the 25 July issue of ''Nature''. At the end of 1954, Bernal secured funding for Franklin from the Agricultural Research Council (ARC), which enabled her to work as a senior scientist supervising her own research group.Brown, pp. 356–357. John Finch, a physics student from King's College London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public university, public research university in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of George IV of the United Kingdom, King George IV ...

, subsequently joined Franklin's group, followed by Kenneth Holmes, a Cambridge graduate, in July 1955. Despite the ARC funding, Franklin wrote to Bernal that the existing facilities remained highly unsuited for conducting research:

...my desk and lab are on the fourth floor, my X-ray tube in the basement, and I am responsible for the work of four people distributed over the basement, first and second floors on two different staircases.

RNA research

Franklin continued to explore another major nucleic acid,RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule that is essential for most biological functions, either by performing the function itself (non-coding RNA) or by forming a template for the production of proteins (messenger RNA). RNA and deoxyrib ...

, a molecule equally central to life as DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

. She again used X-ray crystallography to study the structure of the tobacco mosaic virus

Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) is a positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus species in the genus '' Tobamovirus'' that infects a wide range of plants, especially tobacco and other members of the family Solanaceae. The infection causes characteris ...

(TMV), an RNA virus

An RNA virus is a virus characterized by a ribonucleic acid (RNA) based genome. The genome can be single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) or double-stranded (Double-stranded RNA, dsRNA). Notable human diseases caused by RNA viruses include influenza, SARS, ...

. Her meeting with Aaron Klug in early 1954 led to a longstanding and successful collaboration. Klug had just then earned his PhD from Trinity College, Cambridge

Trinity College is a Colleges of the University of Cambridge, constituent college of the University of Cambridge. Founded in 1546 by King Henry VIII, Trinity is one of the largest Cambridge colleges, with the largest financial endowment of any ...

, and joined Birkbeck in late 1953. In 1955, Franklin published her first major works on TMV in ''Nature'', where she described that all TMV virus particles were of the same length. This was in direct contradiction to the ideas of the eminent virologist Norman Pirie, though Franklin's observation ultimately proved correct.

Franklin assigned the study of the complete structure of TMV to her PhD student Holmes. They soon discovered (published in 1956) that the covering of TMV was protein molecules arranged in helices. Her colleague Klug worked on spherical viruses with his student Finch, with Franklin coordinating and overseeing the work. As a team, from 1956 they started publishing seminal works on TMV, cucumber virus 4 and turnip yellow mosaic virus.

Franklin also had a research assistant

A research assistant (RA) is a researcher employed, often on a temporary contract, by a university, research institute, or privately held organization to provide assistance in academic or private research endeavors. Research assistants work under ...

, James Watt, subsidised by the National Coal Board

The National Coal Board (NCB) was the statutory corporation created to run the nationalised coal mining industry in the United Kingdom. Set up under the Coal Industry Nationalisation Act 1946, it took over the United Kingdom's collieries on "ve ...

and was now the leader of the ARC group at Birkbeck. The Birkbeck team members continued working on RNA viruses affecting several plants, including potato, turnip, tomato and pea. In 1955 the team was joined by an American post-doctoral student Donald Caspar. He worked on the precise location of RNA molecules in TMV. In 1956, Caspar and Franklin published individual but complementary papers in the 10 March issue of ''Nature'', in which they showed that the RNA in TMV is wound along the inner surface of the hollow virus. Caspar was not an enthusiastic writer, and Franklin had to write the entire manuscript for him.

Franklin's research grant from ARC expired at the end of 1957, and she was never given the full salary proposed by Birkbeck. After Bernal requested ARC chairman Lord Rothschild, she was given a one-year extension ending in March 1958.

Expo 58

Expo 58, also known as the 1958 Brussels World's Fair (; ), was a world's fair held on the Heysel/Heizel Plateau in Brussels, Belgium, from 17 April to 19 October 1958. It was the first major world's fair registered under the Bureau Internati ...

, the first major international fair after World War II, was to be held in Brussels in 1958. Franklin was invited to make a five-foot high model of TMV, which she started in 1957. Her materials included table tennis balls and plastic bicycle handlebar grips. The Brussels world's fair, with an exhibit of her virus model at the International Science Pavilion, opened on 17 April, one day after she died.

Polio virus

In 1956 Franklin visited theUniversity of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, where colleagues suggested her group research the polio virus. In 1957 she applied for a grant from the United States Public Health Service

The United States Public Health Service (USPHS or PHS) is a collection of agencies of the Department of Health and Human Services which manages public health, containing nine out of the department's twelve operating divisions. The Assistant Se ...

of the National Institutes of Health

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the primary agency of the United States government responsible for biomedical and public health research. It was founded in 1887 and is part of the United States Department of Health and Human Service ...

, which approved £10,000 (equivalent to £ in ) for three years, the largest fund ever received at Birkbeck. In her grant application, Franklin mentioned her new interest in animal virus research. She obtained Bernal's consent in July 1957, though serious concerns were raised after Franklin disclosed her intentions to research live, instead of killed, polio virus at Birkbeck. Eventually, Bernal arranged for the virus to be safely stored at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

The London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) is a public university, public research university in Bloomsbury, central London, and a constituent college, member institution of the University of London that specialises in public hea ...

during the group's research. With her group, Franklin then commenced deciphering the structure of the polio virus while it was in a crystalline state. She attempted to mount the virus crystals in capillary tubes for X-ray studies, but was forced to end her work due to her rapidly failing health.

After Franklin's death Klug succeeded her as group leader, and he, Finch and Holmes continued researching the structure of the polio virus. They eventually succeeded in obtaining extremely detailed X-ray images of the virus. In June 1959 Klug and Finch published the group's findings, revealing the polio virus to have icosahedral symmetry, and in the same paper suggested the possibility for all spherical viruses to possess the same symmetry, as it permitted the greatest possible number (60) of identical structural units. The team moved to the Laboratory of Molecular Biology

The Medical Research Council (MRC) Laboratory of Molecular Biology (LMB) is a research institute in Cambridge, England, involved in the revolution in molecular biology which occurred in the 1950–60s. Since then it has remained a major medical r ...

, Cambridge, in 1962 and the old Torrington Square laboratories were demolished four years later, in May 1966.

Personal life

Franklin was best described as an agnostic. Her lack of religious faith apparently did not stem from anyone's influence, rather from her own line of thinking. She developed her scepticism as a young child. Her mother recalled that she refused to believe in theexistence of God

The existence of God is a subject of debate in the philosophy of religion and theology. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God (with the same or similar arguments also generally being used when talking about the exis ...

, and remarked, "Well, anyhow, how do you know He isn't She?" She later made her position clear, now based on her scientific experience, and wrote to her father in 1940:

However, Franklin did not abandon Jewish traditions. As the only Jewish student at Lindores School, she had Hebrew lessons on her own while her friends went to church. She joined the Jewish Society while in her first term at Cambridge, out of respect of her grandfather's request. Franklin confided to her sister that she was "always consciously a Jew".

Franklin loved travelling abroad, particularly trekking

Backpacking is the outdoor recreation of carrying gear on one's back while hiking for more than a day. It is often an extended journey and may involve camping outdoors. In North America, tenting is common, where simple shelters and mountain hu ...

. She first "qualified" at Christmas 1929 for a vacation at Menton

Menton (; in classical norm or in Mistralian norm, , ; ; or depending on the orthography) is a Commune in France, commune in the Alpes-Maritimes department in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur region on the French Riviera, close to the Italia ...

, France, where her grandfather went to escape the English winter. Her family frequently spent vacations in Wales or Cornwall. A trip to France in 1938 gave Franklin a lasting love for France and its language. She considered the French lifestyle at that time as "vastly superior to that of English".Polcovar, p. 33. In contrast, Franklin described English people as having "vacant stupid faces and childlike complacency". Her family was almost stuck in Norway in 1939, as World War II was declared on their way home. In another instance, Franklin trekked the French Alps with Jean Kerslake in 1946, which almost cost her her life. Franklin slipped off a slope, and was barely rescued. But she wrote to her mother, "I am quite sure I could wander happily in France forever. I love the people, the country and the food."Polcovar, p. 41. Of note are also Franklin's visits to Yugoslavia

, common_name = Yugoslavia

, life_span = 1918–19921941–1945: World War II in Yugoslavia#Axis invasion and dismemberment of Yugoslavia, Axis occupation

, p1 = Kingdom of SerbiaSerbia

, flag_p ...

. She collaborated with Slovenian chemist whom she met at King's College in 1951. In the 1950s, she visited Slovenia

Slovenia, officially the Republic of Slovenia, is a country in Central Europe. It borders Italy to the west, Austria to the north, Hungary to the northeast, Croatia to the south and southeast, and a short (46.6 km) coastline within the Adriati ...

one or more times where she held a lecture on coal in Ljubljana

{{Infobox settlement

, name = Ljubljana

, official_name =

, settlement_type = Capital city

, image_skyline = {{multiple image

, border = infobox

, perrow = 1/2/2/1

, total_widt ...

and visited the Julian Alps

The Julian Alps (, , , , ) are a mountain range of the Southern Limestone Alps that stretches from northeastern Italy to Slovenia, where they rise to 2,864 m at Mount Triglav, the highest peak in Slovenia. A large part of the Julian Alps is inclu ...

(Triglav

Triglav (; ; ), with an elevation of , is the highest mountain in Slovenia and the highest peak of the Julian Alps. The mountain is the pre-eminent symbol of the Slovene nation, appearing on the Coat of arms of Slovenia, coat of arms and Flag ...

and Bled). Her best-known trekking photograph was presumably created by Hadži in May 1952 and depicts Franklin against the background of the natural rock formation of Heathen Maiden. She also collaborated with the Croatian physicist Katarina Kranjc. She held lectures in Zagreb

Zagreb ( ) is the capital (political), capital and List of cities and towns in Croatia#List of cities and towns, largest city of Croatia. It is in the Northern Croatia, north of the country, along the Sava river, at the southern slopes of the ...

and Belgrade

Belgrade is the Capital city, capital and List of cities in Serbia, largest city of Serbia. It is located at the confluence of the Sava and Danube rivers and at the crossroads of the Pannonian Basin, Pannonian Plain and the Balkan Peninsula. T ...

and visited Dalmatia

Dalmatia (; ; ) is a historical region located in modern-day Croatia and Montenegro, on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea. Through time it formed part of several historical states, most notably the Roman Empire, the Kingdom of Croatia (925 ...

.

Franklin made several professional trips to the United States, and was particularly jovial among her American friends and constantly displayed her sense of humour. William Ginoza of the University of California, Los Angeles

The University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) is a public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Los Angeles, California, United States. Its academic roots were established in 1881 as a normal school the ...

, later recalled that Franklin was the opposite of Watson's description of her, and as Maddox comments, Americans enjoyed her "sunny side".

In his book ''The Double Helix'', Watson provides his first-person account of the search for and discovery of DNA. He paints a sympathetic but sometimes critical portrait of Franklin. He praises her intellect and scientific acumen, but portrays Franklin as difficult to work with and careless with her appearance. After introducing her in the book as "Rosalind", he writes that he and his male colleagues usually referred to her as "Rosy", the name people at King's College London used behind her back. Franklin did not want to be called by that name because she had a great-aunt, Rosy. In the family, she was called "Ros". To others, Franklin was simply "Rosalind". She made it clear to an American visiting friend, Dorothea Raacke, while sitting with her at Crick's table in The Eagle pub in Cambridge: Raacke asked her how she would like to be addressed, she replied, "I'm afraid it will have to be Rosalind", adding "Most definitely not ''Rosy''."Maddox, p. 288.

Franklin often expressed her political views. She initially blamed Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 1874 – 24 January 1965) was a British statesman, military officer, and writer who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1940 to 1945 (Winston Churchill in the Second World War, ...

for inciting the war but later admired him for his speeches. Franklin actively supported Professor John Ryle as an independent candidate for parliament in the 1940 Cambridge University by-election, but he was unsuccessful.Glynn, p. 52.

Franklin did not seem to have an intimate relationship with anyone and always kept her deepest personal feelings to herself. After her younger days, she avoided close friendship with the opposite sex. In her later years, Evi Ellis, who had shared her bedroom when she was a child refugee and who was then married to Ernst Wohlgemuth and had moved to Notting Hill from Chicago, tried matchmaking her with Ralph Miliband but failed. Franklin once told Evi that a man who had a flat on the same floor as hers asked if she would like to come in for a drink, but she did not understand the intention. She was quite infatuated by her French mentor Mering, who had a wife and a mistress. Mering also admitted that he was captivated by her "intelligence and beauty". According to Anne Sayre, Franklin did confess her feeling for Mering when she was undergoing a second surgery, but Maddox reported that the family denied this. Mering wept when he visited her later, and destroyed all her letters after her death.

Franklin's closest personal affair was probably with her once post-doctoral student Donald Caspar. In 1956, she visited him at his home in Colorado after her tour to University of California, Berkeley

The University of California, Berkeley (UC Berkeley, Berkeley, Cal, or California), is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Berkeley, California, United States. Founded in 1868 and named after t ...

, and she was known to remark later that Caspar was one "she might have loved, might have married". In her letter to Sayre, Franklin described him as "an ideal match".

Illness, death, and burial

In mid-1956, while on a work-related trip to the United States, Franklin first began to suspect a health problem. While in New York, she found difficulty in zipping her skirt; her stomach had bulged. Back in London, Franklin consulted Mair Livingstone, who asked her, "You're not pregnant?" to which she retorted, "I wish I were." Her case was marked "URGENT". An operation on 4 September of the same year revealed two tumors in her abdomen. After this period and other periods of hospitalisation, Franklin spent time convalescing with various friends and family members. These included Anne Sayre, Francis Crick, his wife Odile, with whom Franklin had formed a strong friendship, and finally with the Roland and Nina Franklin family where Rosalind's nieces and nephews bolstered her spirits. Franklin chose not to stay with her parents because her mother's uncontrollable grief and crying upset her too much. Even while undergoing cancer treatment, Franklin continued to work, and her group continued to produce results – seven papers in 1956 and six more in 1957. At the end of 1957 Franklin again fell ill and she was admitted to the Royal Marsden Hospital. On 2 December she made her will. Franklin named her three brothers as executors and made her colleague Aaron Klug the principal beneficiary, who would receive £3,000 and her Austin car. Of her other friends, Mair Livingstone would get £2,000, Anne Piper £1,000, and her nurse Miss Griffith £250. The remainder of the estate was to be used for charities. Franklin returned to work in January 1958 and was also given a promotion to Research Associate in Biophysics on 25 February. She fell ill again on 30 March and died a few weeks later on 16 April 1958 in Chelsea, London, ofbronchopneumonia

Bronchopneumonia is a subtype of pneumonia. It is the acute inflammation of the Bronchus, bronchi, accompanied by inflamed patches in the nearby lobules of the lungs. citing: Webster's New World College Dictionary, Fifth Edition, Copyright 2014

...

, secondary carcinomatosis, and ovarian cancer. Exposure to X-ray radiation is sometimes considered to be a possible factor in Franklin's illness.Along with genetic predisposition; opinion of CSU's Lynne Osman Elkin; see also March 2003 ''Physics Today''

Other members of her family have died of cancer, and the incidence of gynaecological cancer

Gynaecology or gynecology (see American and British English spelling differences) is the area of medicine concerned with conditions affecting the female reproductive system. It is often paired with the field of obstetrics, which focuses on pre ...

is known to be disproportionately high among Ashkenazi Jews

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; also known as Ashkenazic Jews or Ashkenazim) form a distinct subgroup of the Jewish diaspora, that emerged in the Holy Roman Empire around the end of the first millennium CE. They traditionally speak Yiddish, a language ...

. Franklin's death certificate states: ''A Research Scientist, Spinster, Daughter of Ellis Arthur Franklin, a Banker.'' She was interred on 17 April 1958 in the family plot at Willesden United Synagogue Cemetery at Beaconsfield Road in London Borough of Brent

Brent () is a London boroughs, borough in north-west London, England. It is known for landmarks such as Wembley Stadium, the BAPS Shri Swaminarayan Mandir London, Swaminarayan Temple and the Kiln Theatre. It also contains the Brent Reservoir, W ...

. The inscription on her tombstone reads:

IN MEMORY OFFranklin's will was proven on 30 June with her estate assessed for probate at £11,278 10s. 9d. (equivalent to £ in ).

ROSALIND ELSIE FRANKLIN

מ' רחל בת ר' יהודה ochel/Rachel daughter of Yehuda, her father's Hebrew namebr /> DEARLY LOVED ELDER DAUGHTER OF

ELLIS AND MURIEL FRANKLIN

25TH JULY 1920 – 16TH APRIL 1958

SCIENTIST

HER RESEARCH AND DISCOVERIES ON

VIRUSES REMAIN OF LASTING BENEFIT

TO MANKIND

ת נ צ ב ה ebrew initials for "her soul shall be bound in the bundle of life"

Controversies after death

Alleged sexism toward Franklin

Anne Sayre, Franklin's friend and one of her biographers, says in her 1975 book, '' Rosalind Franklin and DNA: '' "In 1951 ... King's College London as an institution, was not distinguished for the welcome that it offered to women ... Rosalind ... was unused to '' purdah'' religious and social institution of female seclusionnbsp;... there was one other female on the laboratory staff". Themolecular biologist

Molecular biology is a branch of biology that seeks to understand the molecule, molecular basis of biological activity in and between Cell (biology), cells, including biomolecule, biomolecular synthesis, modification, mechanisms, and interactio ...

Andrzej Stasiak notes: "Sayre's book became widely cited in feminist circles for exposing rampant sexism in science." Farooq Hussain says: "there were seven women in the biophysics department ... Jean Hanson became an FRS, Dame Honor B. Fell, Director of Strangeways Laboratory, supervised the biologists". Maddox, Franklin's biographer, states: " Randall ... did have many women on his staff ... they found him ... sympathetic and helpful."Maddox, p. 135.

Sayre asserts that "while the male staff at King's lunched in a large, comfortable, rather clubby dining room" the female staff of all ranks "lunched in the student's hall or away from the premises". However, Elkin claims that most of the MRC group (including Franklin) typically ate lunch together in the mixed dining room discussed below. And Maddox says, of Randall: "He liked to see his flock, men and women, come together for morning coffee, and at lunch in the joint dining room, where he ate with them nearly every day." Francis Crick also commented that "her colleagues treated men and women scientists alike".

Sayre also discusses at length Franklin's struggle in pursuing science, particularly her father's concern about women in academic professions. This account had led to accusations of sexism in regard to Ellis Franklin's attitude to his daughter. A good deal of information explicitly claims that he strongly opposed her entering Newnham College. The Public Broadcasting Service

The Public Broadcasting Service (PBS) is an American public broadcaster and non-commercial, free-to-air television network based in Arlington, Virginia

Arlington County, or simply Arlington, is a County (United States), county in the ...

(PBS) biography of Franklin goes further, stating that he refused to pay her fees, and that an aunt stepped in to do that for her. Her sister, Jenifer Glynn, has stated that those stories are myths, and that her parents fully supported Franklin's entire career.

Sexism is said to pervade the memoir of one peer, James Watson, in his book ''The Double Helix'', published 10 years after Franklin's death and after Watson had returned from Cambridge to Harvard. His Cambridge colleague, Peter Pauling, wrote in a letter, "Morris 'sic''Wilkins is supposed to be doing this work; Miss Franklin is evidently a fool." Crick acknowledges later, "I'm afraid we always used to adopt – let's say, a ''patronizing'' attitude towards her."

Glynn accuses Sayre of erroneously making her sister a feminist heroine, and sees Watson's ''The Double Helix'' as the root of what she calls the "Rosalind Industry". She conjectures that the stories of alleged sexism would "have embarrassed her osalind Franklinalmost as much as Watson's account would have upset her", and declared that "she osalindwas never a feminist." Klug and Crick have also concurred that Franklin was definitely not a feminist.