Renaissance Italy on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Italian Renaissance ( ) was a period in Italian history between the 14th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader

It was during this period of instability that the first secular authors such as

It was during this period of instability that the first secular authors such as

siege of Florence

when it looked as though the city was doomed to fall, before Giangaleazzo suddenly died and his empire collapsed. This thesis suggests that during these long wars, the leading figures of Florence rallied the people by presenting the war as one between the free republic and a despotic monarchy, between the ideals of the Greek and Roman Republics and those of the Roman Empire and medieval kingdoms. For Baron, the most important figure in crafting this ideology was Leonardo Bruni. This time of crisis in Florence was the period when the most influential figures of the early Renaissance were coming of age, such as Ghiberti,

The main challengers of the Albizzi family were the Medicis, first under Giovanni de' Medici, and later under his son Cosimo de' Medici. The Medici controlled the Medici bank—then Europe's largest bank—and an array of other enterprises in Florence and elsewhere. In 1433, the Albizzi managed to have Cosimo exiled. The next year, however, saw a pro-Medici Signoria elected and Cosimo returned. The Medici became the town's leading family, a position they would hold for the next three centuries. Florence organized the trade routes for commodities between England and the Netherlands, France, and Italy. By the middle of the century, the city had become the banking capital of Europe and thereby obtained vast riches. In 1439,

The main challengers of the Albizzi family were the Medicis, first under Giovanni de' Medici, and later under his son Cosimo de' Medici. The Medici controlled the Medici bank—then Europe's largest bank—and an array of other enterprises in Florence and elsewhere. In 1433, the Albizzi managed to have Cosimo exiled. The next year, however, saw a pro-Medici Signoria elected and Cosimo returned. The Medici became the town's leading family, a position they would hold for the next three centuries. Florence organized the trade routes for commodities between England and the Netherlands, France, and Italy. By the middle of the century, the city had become the banking capital of Europe and thereby obtained vast riches. In 1439,

Renaissance ideals first spread from Florence to the neighbouring states of

Renaissance ideals first spread from Florence to the neighbouring states of

The end of the Italian Renaissance is as imprecisely marked as its starting point. For many, the rise to power in Florence of the austere monk

The end of the Italian Renaissance is as imprecisely marked as its starting point. For many, the rise to power in Florence of the austere monk

One role of

One role of

In painting, the late medieval painter Giotto di Bondone, or

In painting, the late medieval painter Giotto di Bondone, or

In Florence, the Renaissance style was introduced with a revolutionary but incomplete monument by

In Florence, the Renaissance style was introduced with a revolutionary but incomplete monument by

online

. * Burke, Peter. ''The Italian Renaissance: Culture and Society in Italy.'' Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1999. * Capra, Fritjof (2008). ''The Science of Leonardo. Inside the Mind of the Great Genius of the Renaissance.'' Doubleday, . * Ceriani Sebregondi, Giulia. ''On Architectural Practice and Arithmetic Abilities in Renaissance Italy.'' Architectural Histories, vol. 3, no. 1, 2015

online

. * Vincent Cronin, Cronin, Vincent: ** ''The Florentine Renaissance.'' 1967, . ** ''The Flowering of the Renaissance.'' 1969, . ** ''The Renaissance.'' 1992, . * Hagopian, Viola L. "Italy", in Stanley Sadie (ed.). ''The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians.'' London: Macmillan Publishers Ltd., 1980. * Denys Hay, Hay, Denys. ''The Italian Renaissance in Its Historical Background''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977. * Jensen, De Lamar. ''Renaissance Europe.'' 1992. * Jurdjevic, Mark. "Hedgehogs and Foxes: The Present and Future of Italian Renaissance Intellectual History", in ''Past & Present'' 195 (2007), pp. 241–268. * * Lopez, Robert Sabatino. ''The Three Ages of the Italian Renaissance.'' Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1970. * Petrocchi, Alessandra & Joshua Brown. ''Languages and Cross-Cultural Exchanges in Renaissance Italy.'' Turnhout: Brepols, 2023. * Pullan, Brian S. ''History of Early Renaissance Italy.'' London: Lane, 1973. * Raffini, Christine. ''Marsilio Ficino, Pietro Bembo, Baldassare Castiglione: Philosophical, Aesthetic, and Political Approaches in Renaissance Platonism.'' Renaissance and Baroque Studies and Texts 21, Peter Lang Publishing, 1998, . * Ruggiero, Guido. ''The Renaissance in Italy: A Social and Cultural History of the Rinascimento.'' Cambridge University Press, 2015

online review

.

''The Prince by Niccolò Machiavelli''

. {{Authority control Italian Renaissance, 14th-century establishments in Italy 17th-century disestablishments in Italy Renaissance Cultural history of Italy, Renaissance Design history, Italian Renaissance Landscape design history, Italian Renaissanceworks Italian Renaissance gardens, * Renaissance art Renaissance architecture History of art, Italy Architectural history, Italy Environmental design, Italian Renaissance 14th century in Italy, * 15th century in Italy, * 16th century in Italy, *

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) is a Periodization, period of history and a European cultural movement covering the 15th and 16th centuries. It marked the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and was characterized by an effort to revive and sur ...

culture that spread across Western Europe

Western Europe is the western region of Europe. The region's extent varies depending on context.

The concept of "the West" appeared in Europe in juxtaposition to "the East" and originally applied to the Western half of the ancient Mediterranean ...

and marked the transition from the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the 5th to the late 15th centuries, similarly to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire and ...

to modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular Society, socio-Culture, cultural Norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the ...

. Proponents of a "long Renaissance" argue that it started around the year 1300 and lasted until about 1600. In some fields, a Proto-Renaissance, beginning around 1250, is typically accepted. The French word (corresponding to in Italian) means 'rebirth', and defines the period as one of cultural revival and renewed interest in classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

after the centuries during what Renaissance humanists labelled as the "Dark Ages". The Italian Renaissance historian Giorgio Vasari

Giorgio Vasari (30 July 1511 – 27 June 1574) was an Italian Renaissance painter, architect, art historian, and biographer who is best known for his work ''Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects'', considered the ideol ...

used the term ('rebirth') in his ''Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects

''The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects'' () is a series of artist biographies written by 16th-century Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari, which is considered "perhaps the most famous, and even today the ...

'' in 1550, but the concept became widespread only in the 19th century, after the work of scholars such as Jules Michelet

Jules Michelet (; 21 August 1798 – 9 February 1874) was a French historian and writer. He is best known for his multivolume work ''Histoire de France'' (History of France). Michelet was influenced by Giambattista Vico; he admired Vico's emphas ...

and Jacob Burckhardt

Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt (; ; 25 May 1818 – 8 August 1897) was a Swiss historian of art and culture and an influential figure in the historiography of both fields. His best known work is '' The Civilization of the Renaissance in ...

.

The Renaissance began in Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

in Central Italy

Central Italy ( or ) is one of the five official statistical regions of Italy used by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), a first-level NUTS region with code ITI, and a European Parliament constituency. It has 11,704,312 inhabita ...

and centred in the city of Florence

Florence ( ; ) is the capital city of the Italy, Italian region of Tuscany. It is also the most populated city in Tuscany, with 362,353 inhabitants, and 989,460 in Metropolitan City of Florence, its metropolitan province as of 2025.

Florence ...

. The Florentine Republic, one of the several city-states of the peninsula

A peninsula is a landform that extends from a mainland and is only connected to land on one side. Peninsulas exist on each continent. The largest peninsula in the world is the Arabian Peninsula.

Etymology

The word ''peninsula'' derives , . T ...

, rose to economic and political prominence by providing credit for European monarchs and by laying down the groundwork for developments in capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

and in banking

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

. Renaissance culture later spread to Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

, the heart of a Mediterranean empire and in control of the trade routes with the east since its participation in the Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

and following the journeys of Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

between 1271 and 1295. Thus Italy renewed contact with the remains of ancient Greek culture, which provided humanist scholars with new texts. Finally the Renaissance had a significant effect on the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

and on Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

, largely rebuilt by humanist

Humanism is a philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The meaning of the term "humanism" ha ...

and Renaissance popes, such as Julius II and Leo X, who frequently became involved in Italian politics, in arbitrating disputes between competing colonial powers and in opposing the Protestant Reformation

The Reformation, also known as the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation, was a time of major theological movement in Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the papacy and ...

, which started .

The Italian Renaissance has a reputation for its achievements in painting

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

, architecture

Architecture is the art and technique of designing and building, as distinguished from the skills associated with construction. It is both the process and the product of sketching, conceiving, planning, designing, and construction, constructi ...

, sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, science

Science is a systematic discipline that builds and organises knowledge in the form of testable hypotheses and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into twoor threemajor branches: the natural sciences, which stu ...

, technology

Technology is the application of Conceptual model, conceptual knowledge to achieve practical goals, especially in a reproducible way. The word ''technology'' can also mean the products resulting from such efforts, including both tangible too ...

, and exploration

Exploration is the process of exploring, an activity which has some Expectation (epistemic), expectation of Discovery (observation), discovery. Organised exploration is largely a human activity, but exploratory activity is common to most organis ...

. Italy became the recognized European leader in all these areas by the late 15th century, during the era of the Peace of Lodi (1454–1494) agreed between Italian states. The Italian Renaissance peaked in the mid-16th century as domestic disputes and foreign invasions plunged the region into the turmoil of the Italian Wars

The Italian Wars were a series of conflicts fought between 1494 and 1559, mostly in the Italian Peninsula, but later expanding into Flanders, the Rhineland and Mediterranean Sea. The primary belligerents were the House of Valois, Valois kings o ...

(1494–1559). However, the ideas and ideals of the Italian Renaissance spread into the rest of Europe, setting off the Northern Renaissance

The Northern Renaissance was the Renaissance that occurred in Europe north of the Alps, developing later than the Italian Renaissance, and in most respects only beginning in the last years of the 15th century. It took different forms in the vari ...

from the late 15th century. Italian explorers from the maritime republics

The maritime republics (), also called merchant republics (), were Italian Thalassocracy , thalassocratic Port city, port cities which, starting from the Middle Ages, enjoyed political autonomy and economic prosperity brought about by their mar ...

served under the auspices of European monarchs, ushering in the Age of Discovery

The Age of Discovery (), also known as the Age of Exploration, was part of the early modern period and overlapped with the Age of Sail. It was a period from approximately the 15th to the 17th century, during which Seamanship, seafarers fro ...

. The most famous voyage was that of Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus (; between 25 August and 31 October 1451 – 20 May 1506) was an Italians, Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed Voyages of Christopher Columbus, four Spanish-based voyages across the At ...

(who sailed for Spain) and laid the foundation for European dominance of the Americas. Other explorers include Giovanni da Verrazzano (for France), Amerigo Vespucci (for Spain), and John Cabot

John Cabot ( ; 1450 – 1499) was an Italians, Italian navigator and exploration, explorer. His 1497 voyage to the coast of North America under the commission of Henry VII of England, Henry VII, King of England is the earliest known Europe ...

(for England). Italian scientists such as Falloppio, Tartaglia, Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

and Torricelli played key roles in the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of History of science, modern science during the early modern period, when developments in History of mathematics#Mathematics during the Scientific Revolution, mathemati ...

, and foreigners such as Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath who formulated a mathematical model, model of Celestial spheres#Renaissance, the universe that placed heliocentrism, the Sun rather than Earth at its cen ...

and Vesalius

Andries van Wezel (31 December 1514 – 15 October 1564), Latinization of names, latinized as Andreas Vesalius (), was an anatomist and physician who wrote ''De humani corporis fabrica, De Humani Corporis Fabrica Libri Septem'' (''On the fabric ...

worked in Italian universities. Historiographers have proposed various events and dates of the 17th century, such as the conclusion of the European wars of religion

The European wars of religion were a series of wars waged in Europe during the 16th, 17th and early 18th centuries. Fought after the Protestant Reformation began in 1517, the wars disrupted the religious and political order in the Catholic Chu ...

in 1648, as marking the end of the Renaissance.

Accounts of proto- Renaissance literature usually begin with the three great Italian writers of the 14th century: Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

(''Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' (, ) is an Italian narrative poetry, narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun and completed around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature and one of ...

''), Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

('' Canzoniere''), and Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio ( , ; ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was s ...

('' Decameron''). Famous vernacular poets of the Renaissance include the epic

Epic commonly refers to:

* Epic poetry, a long narrative poem celebrating heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation

* Epic film, a genre of film defined by the spectacular presentation of human drama on a grandiose scale

Epic(s) ...

authors Luigi Pulci

Luigi Pulci (; 15 August 1432 – 11 November 1484) was an Italian diplomat and poet best known for his '' Morgante'', an epic and parodistic poem about a giant who is converted to Christianity by Orlando and follows the knight in many adventu ...

(''Morgante

''Morgante'' (sometimes also called , the name given to the complete 28-canto, 30,080-line edition published in 1483See Lèbano's introduction to the Tusiani translation, p. xxii.) is an Italian romantic epic by Luigi Pulci which appeared in ...

''), Matteo Maria Boiardo

Matteo Maria Boiardo (, ; 144019/20 December 1494) was an Italian Renaissance poet, best known for his epic poem ''Orlando innamorato''.

Early life

Boiardo was born in 1440, at or near, Scandiano (today's province of Reggio Emilia); the son of G ...

(''Orlando Innamorato

''Orlando Innamorato'' (; known in English language, English as "''Orlando in Love''"; in Italian language, Italian titled "''Orlando innamorato''" as the "I" is never capitalized) is an epic poem written by the Italian Renaissance author Matte ...

''), Ludovico Ariosto

Ludovico Ariosto (, ; ; 8 September 1474 – 6 July 1533) was an Italian poet. He is best known as the author of the romance epic '' Orlando Furioso'' (1516). The poem, a continuation of Matteo Maria Boiardo's ''Orlando Innamorato'', describ ...

(''Orlando Furioso

''Orlando furioso'' (; ''The Frenzy of Orlando'') is an Italian epic poem by Ludovico Ariosto which has exerted a wide influence on later culture. The earliest version appeared in 1516, although the poem was not published in its complete form ...

''), and Torquato Tasso

Torquato Tasso ( , also , ; 11 March 154425 April 1595) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, known for his 1591 poem ''Gerusalemme liberata'' (Jerusalem Delivered), in which he depicts a highly imaginative version of the combats between ...

('' Jerusalem Delivered''). 15th-century writers such as the poet Poliziano

Agnolo (or Angelo) Ambrogini (; 14 July 1454 – 24 September 1494), commonly known as Angelo Poliziano () or simply Poliziano, anglicized as Politian, was an Italian classical scholar and poet of the Florentine Renaissance. His scholars ...

and the Platonist philosopher Marsilio Ficino

Marsilio Ficino (; Latin name: ; 19 October 1433 – 1 October 1499) was an Italian scholar and Catholic priest who was one of the most influential humanist philosophers of the early Italian Renaissance. He was an astrologer, a reviver of Neo ...

made extensive translations from both Latin and Greek. In the early 16th century, Baldassare Castiglione laid out his vision of the ideal gentleman and lady in ''The Book of the Courtier

''The Book of the Courtier'' ( ) by Baldassare Castiglione is a lengthy philosophical dialogue on the topic of what constitutes an ideal courtier or (in the third chapter) court lady, worthy to befriend and advise a prince or political leader. ...

'', while Niccolò Machiavelli

Niccolò di Bernardo dei Machiavelli (3 May 1469 – 21 June 1527) was a Florentine diplomat, author, philosopher, and historian who lived during the Italian Renaissance. He is best known for his political treatise '' The Prince'' (), writte ...

rejected the ideal with an eye on ''la verità effettuale della cosa'' ('the effectual truth of things') in ''The Prince

''The Prince'' ( ; ) is a 16th-century political treatise written by the Italian diplomat, philosopher, and Political philosophy, political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli in the form of a realistic instruction guide for new Prince#Prince as gener ...

'', composed, in humanistic style, chiefly of parallel ancient and modern examples of virtù. Historians of the period include Machiavelli himself, his friend and critic Francesco Guicciardini

Francesco Guicciardini (; 6 March 1483 – 22 May 1540) was an Italian historian and politician, statesman. A friend and critic of Niccolò Machiavelli, he is considered one of the major political writers of the Italian Renaissance. In his maste ...

and Giovanni Botero ('' The Reason of State''). The Aldine Press

The Aldine Press was the printing office started by Aldus Manutius in 1494 in Venice, from which were issued the celebrated Aldine editions of the classics (Latin and Greek masterpieces, plus a few more modern works). The first book that was d ...

, founded in 1494 by the printer Aldo Manuzio, active in Venice, developed Italic type

In typography, italic type is a cursive font based on a stylised form of calligraphic handwriting. Along with blackletter and roman type, it served as one of the major typefaces in the history of Western typography.

Owing to the influence f ...

and pocket editions that one could carry in one's pocket; it became the first to publish printed editions of books in Ancient Greek. Venice also became the birthplace of the ''commedia dell'arte

Commedia dell'arte was an early form of professional theatre, originating from Theatre of Italy, Italian theatre, that was popular throughout Europe between the 16th and 18th centuries. It was formerly called Italian comedy in English and is a ...

''.

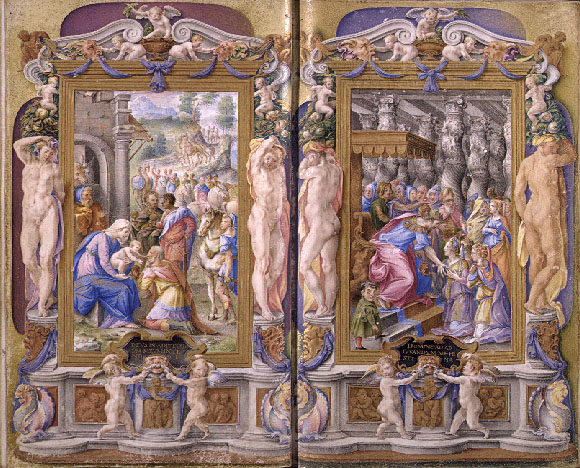

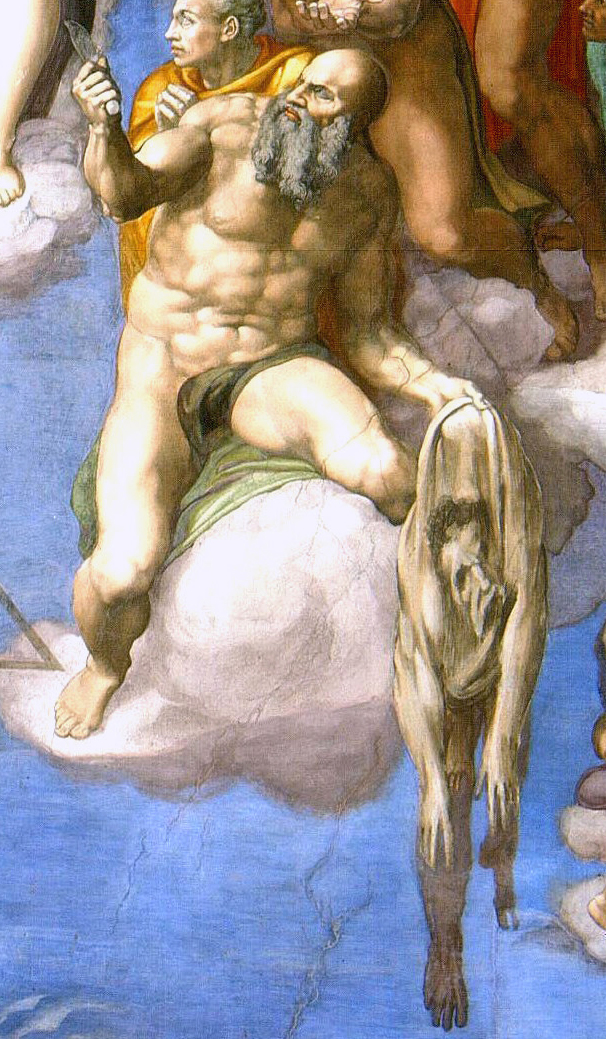

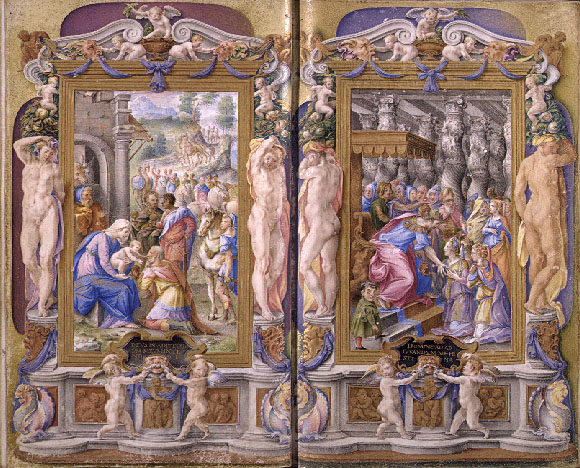

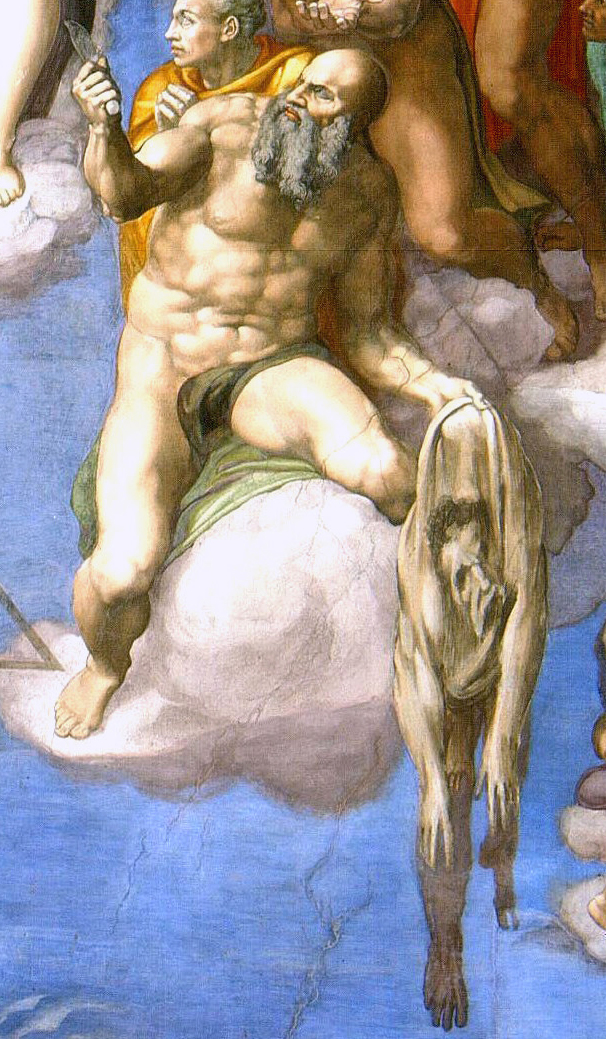

Italian Renaissance art exercised a dominant influence on subsequent European painting and sculpture for centuries afterwards, with artists such as Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci (15 April 1452 - 2 May 1519) was an Italian polymath of the High Renaissance who was active as a painter, draughtsman, engineer, scientist, theorist, sculptor, and architect. While his fame initially rested o ...

, Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

, Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), now generally known in English as Raphael ( , ), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. List of paintings by Raphael, His work is admired for its cl ...

, Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), known mononymously as Donatello (; ), was an Italian Renaissance sculpture, Italian sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Republic of Florence, Florence, he studied classical sc ...

, Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto, was an List of Italian painters, Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the International Gothic, Gothic and Italian Ren ...

, Masaccio

Masaccio (, ; ; December 21, 1401 – summer 1428), born Tommaso di Ser Giovanni di Simone, was a Florentine artist who is regarded as the first great List of Italian painters, Italian painter of the Quattrocento period of the Italian Renaiss ...

, Fra Angelico, Piero della Francesca

Piero della Francesca ( , ; ; ; – 12 October 1492) was an Italian Renaissance painter, Italian painter, mathematician and List of geometers, geometer of the Early Renaissance, nowadays chiefly appreciated for his art. His painting is charact ...

, Domenico Ghirlandaio, Perugino

Pietro Perugino ( ; ; born Pietro Vannucci or Pietro Vanucci; – 1523), an Italian Renaissance painter of the Umbrian school, developed some of the qualities that found classic expression in the High Renaissance. Raphael became his most famous ...

, Botticelli

Alessandro di Mariano di Vanni Filipepi ( – May 17, 1510), better known as Sandro Botticelli ( ; ) or simply known as Botticelli, was an Italian painter of the Early Renaissance. Botticelli's posthumous reputation suffered until the late 1 ...

, and Titian

Tiziano Vecellio (; 27 August 1576), Latinized as Titianus, hence known in English as Titian ( ), was an Italian Renaissance painter, the most important artist of Renaissance Venetian painting. He was born in Pieve di Cadore, near Belluno.

Ti ...

. Italian Renaissance architecture

Renaissance architecture is the European architecture of the period between the early 15th and early 16th centuries in different regions, demonstrating a conscious revival and development of certain elements of Ancient Greece, ancient Greek and ...

had a similar Europe-wide impact, as practised by Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi ( ; ) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to ...

, Leon Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, Catholic priest, priest, linguistics, linguist, philosopher, and cryptography, cryptographer; he epitomised the natu ...

, Andrea Palladio

Andrea Palladio ( , ; ; 30 November 1508 – 19 August 1580) was an Italian Renaissance architect active in the Venetian Republic. Palladio, influenced by Roman and Greek architecture, primarily Vitruvius, is widely considered to be on ...

, and Bramante. Their works include the Florence Cathedral

Florence Cathedral (), formally the Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Flower ( ), is the cathedral of the Catholic Archdiocese of Florence in Florence, Italy. Commenced in 1296 in the Gothic style to a design of Arnolfo di Cambio and completed b ...

, St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, and the Tempio Malatestiano

The Tempio Malatestiano () is the Unfinished building, unfinished cathedral church of Rimini, Italy. Officially named for Francis of Assisi, St. Francis, it takes the popular name from Sigismondo Pandolfo Malatesta, who commissioned its reconstr ...

in Rimini

Rimini ( , ; or ; ) is a city in the Emilia-Romagna region of Northern Italy.

Sprawling along the Adriatic Sea, Rimini is situated at a strategically-important north-south passage along the coast at the southern tip of the Po Valley. It is ...

, as well as several private residences. The musical era of the Italian Renaissance featured composers such as Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina

Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (between 3 February 1525 and 2 February 1526 – 2 February 1594) was an Italian composer of late Renaissance music. The central representative of the Roman School, with Orlande de Lassus and Tomás Luis de V ...

, the Roman School and later the Venetian School, and the birth of opera through figures like Claudio Monteverdi

Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi (baptized 15 May 1567 – 29 November 1643) was an Italian composer, choirmaster and string instrument, string player. A composer of both Secular music, secular and Church music, sacred music, and a pioneer ...

in Florence. In philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, thinkers such as Galileo, Machiavelli, Giordano Bruno

Giordano Bruno ( , ; ; born Filippo Bruno; January or February 1548 – 17 February 1600) was an Italian philosopher, poet, alchemist, astrologer, cosmological theorist, and esotericist. He is known for his cosmological theories, which concep ...

and Pico della Mirandola emphasized naturalism and humanism

Humanism is a philosophy, philosophical stance that emphasizes the individual and social potential, and Agency (philosophy), agency of human beings, whom it considers the starting point for serious moral and philosophical inquiry.

The me ...

, thus rejecting dogma and scholasticism

Scholasticism was a medieval European philosophical movement or methodology that was the predominant education in Europe from about 1100 to 1700. It is known for employing logically precise analyses and reconciling classical philosophy and Ca ...

.

Origins and background

Northern and Central Italy in the Late Middle Ages

By theLate Middle Ages

The late Middle Ages or late medieval period was the Periodization, period of History of Europe, European history lasting from 1300 to 1500 AD. The late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period ( ...

(), Latium

Latium ( , ; ) is the region of central western Italy in which the city of Rome was founded and grew to be the capital city of the Roman Empire.

Definition

Latium was originally a small triangle of fertile, volcanic soil (Old Latium) on whic ...

, the former heartland of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ruled the Mediterranean and much of Europe, Western Asia and North Africa. The Roman people, Romans conquered most of this during the Roman Republic, Republic, and it was ruled by emperors following Octavian's assumption of ...

, and southern Italy

Southern Italy (, , or , ; ; ), also known as () or (; ; ; ), is a macroregion of Italy consisting of its southern Regions of Italy, regions.

The term "" today mostly refers to the regions that are associated with the people, lands or cultu ...

were generally poorer than the North. Rome

Rome (Italian language, Italian and , ) is the capital city and most populated (municipality) of Italy. It is also the administrative centre of the Lazio Regions of Italy, region and of the Metropolitan City of Rome. A special named with 2, ...

was a city of ancient ruins, and the Papal States

The Papal States ( ; ; ), officially the State of the Church, were a conglomeration of territories on the Italian peninsula under the direct sovereign rule of the pope from 756 to 1870. They were among the major states of Italy from the 8th c ...

were loosely administered and vulnerable to external interference, particularly by France, and later Spain. The Papacy was affronted when the Avignon Papacy

The Avignon Papacy (; ) was the period from 1309 to 1376 during which seven successive popes resided in Avignon (at the time within the Kingdom of Arles, part of the Holy Roman Empire, now part of France) rather than in Rome (now the capital of ...

was created in southern France as a consequence of pressure from King Philip the Fair of France. In the south, Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

had for some time been under foreign domination, by the Arabs and then the Normans. Sicily had prospered for 150 years during the Emirate of Sicily

The island of SicilyIn Arabic, the island was known as (). was under Islam, Islamic rule from the late ninth to the late eleventh centuries. It became a prosperous and influential commercial power in the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean, with ...

and later for two centuries during the Norman Kingdom and the Hohenstaufen Kingdom, but had declined by the Late Middle Ages.

In contrast, Northern and Central Italy had become far more prosperous, and it has been calculated that the region was among the richest in Europe. The Crusades

The Crusades were a series of religious wars initiated, supported, and at times directed by the Papacy during the Middle Ages. The most prominent of these were the campaigns to the Holy Land aimed at reclaiming Jerusalem and its surrounding t ...

had built trade links to the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, and the Fourth Crusade

The Fourth Crusade (1202–1204) was a Latin Christian armed expedition called by Pope Innocent III. The stated intent of the expedition was to recapture the Muslim-controlled city of Jerusalem, by first defeating the powerful Egyptian Ayyubid S ...

had done much to destroy the Byzantine Empire

The Byzantine Empire, also known as the Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire centred on Constantinople during late antiquity and the Middle Ages. Having survived History of the Roman Empire, the events that caused the ...

as a commercial rival to the Venetians and the Genoese. The main trade routes from the east passed through the Byzantine Empire or the Arab lands and onward to the ports of Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, and Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. Luxury goods bought in the Levant, such as spices, dyes, and silks were imported to Italy and then resold throughout Europe. Moreover, the inland city-state

A city-state is an independent sovereign city which serves as the center of political, economic, and cultural life over its contiguous territory. They have existed in many parts of the world throughout history, including cities such as Rome, ...

s profited from the rich agricultural land of the Po Valley. From France, Germany, and the Low Countries, through the medium of the Champagne fairs, land and river trade routes brought goods such as wool, wheat, and precious metals into the region. The extensive trade, which stretched from Egypt to the Baltic

Baltic may refer to:

Peoples and languages

*Baltic languages, a subfamily of Indo-European languages, including Lithuanian, Latvian and extinct Old Prussian

*Balts (or Baltic peoples), ethnic groups speaking the Baltic languages and/or originatin ...

, generated substantial surpluses that allowed significant investment in mining and agriculture. By the 14th century, the city of Venice had become an emporium for lands as far as Cyprus

Cyprus (), officially the Republic of Cyprus, is an island country in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Situated in West Asia, its cultural identity and geopolitical orientation are overwhelmingly Southeast European. Cyprus is the List of isl ...

; it boasted a naval fleet of over 5000 ships thanks to its arsenal, a vast complex of shipyards that was the first European facility to mass-produce commercial and military vessels. Genoa also had become a maritime power. Thus, while northern Italy was not richer in resources than many other parts of Europe, the level of development, stimulated by trade, allowed it to prosper. Florence became one of the wealthiest of the cities of Northern Italy, mainly due to its woollen textile production, developed under the supervision of its dominant trade guild

A guild ( ) is an association of artisans and merchants who oversee the practice of their craft/trade in a particular territory. The earliest types of guild formed as organizations of tradespeople belonging to a professional association. They so ...

, the '' Arte della Lana''. Wool was imported from Northern Europe (and in the 16th century from Spain) and together with dyes from the east were used to make high-quality textiles.

The Italian trade routes that covered the Mediterranean and beyond were also major conduits of culture and knowledge. The recovery of lost Greek classics brought to Italy by refugee Byzantine scholars, who migrated during and following the Ottoman conquest of the Byzantine Empire in the 15th century, were important in sparking the new linguistic studies of the Renaissance, in newly created academies in Florence and Venice. Humanist scholars searched monastic libraries for ancient manuscripts and recovered Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

Tacitus’ two major historical works, ''Annals'' ( ...

and other Latin authors. The rediscovery of Vitruvius

Vitruvius ( ; ; –70 BC – after ) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work titled . As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissan ...

meant that the architectural principles of Antiquity could be observed once more, and Renaissance artists were encouraged, in the atmosphere of humanist optimism, to excel in the achievements of the Ancients, like Apelles

Apelles of Kos (; ; fl. 4th century BC) was a renowned Painting, painter of ancient Greece. Pliny the Elder, to whom much of modern scholars' knowledge of this artist is owed (''Natural History (Pliny), Naturalis Historia'' 35.36.79–97 and '' ...

, of whom they read.

Religious background

After thefall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

in the fifth century AD, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

filled the subsequent vacuum. In the Middle Ages, the Church was considered to be the will of God, and it regulated the standard of behaviour in life. A lack of literacy and prohibitions against translations of the Bible required most people to rely on the priestly explanation of Biblical ethics and laws.

In the eleventh century, the Church persecuted many groups including pagans, Jews, and lepers in order to eliminate irregularities in society and strengthen Church power. In response to the laity's challenge to Church authority, bishops played an important role as they gradually lost control of secular authority. To regain the power of discourse, they adopted extreme control methods, such as persecuting infidels.

The Church also collected wealth from believers in the Middle Ages, such as through the sale of indulgences, although this mainly occurred in northern Europe. It also did not pay taxes, making the Church's wealth greater than some kings.

Thirteenth century

In the 13th century, much of Europe experienced strong economic growth. The trade routes of the Italian states linked with those of established Mediterranean ports and eventually theHanseatic League

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

of the Baltic and northern regions of Europe to create a network economy in Europe for the first time since the 4th century. The city-states of Italy expanded greatly during this period and grew in power to become de facto fully independent of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

; and apart from the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

, outside powers kept their armies out of Italy. Crucially, during this period, since Christians had not been allowed to lend money nor the Jews to farm, the Jewish communities developed a modern commercial infrastructure, with double-entry book-keeping, joint stock companies, an international banking

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

system, systematized foreign exchange market

The foreign exchange market (forex, FX, or currency market) is a global decentralized or over-the-counter (OTC) market for the trading of currencies. This market determines foreign exchange rates for every currency. By trading volume, ...

, insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to protect ...

, government debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occu ...

(and would one day finance the voyages of Christopher Columbus through the pooling of resources and financial risk). Florence became the centre of this financial industry, and the gold florin

The Florentine florin was a gold coin (in Italian ''Fiorino d'oro'') struck from 1252 to 1533 with no significant change in its design or metal content standard during that time.

It had 54 grains () of nominally pure or 'fine' gold with a pu ...

became the main currency of international trade.

The new mercantile governing class, who gained their position through the loss of two-thirds of the Western European population in recurring plagues (followed by the Muslim sale of over a million Christian slaves into Africa) left acute labor shortages and a civilization able to demand higher pay and even private land ownership in return. The smaller population ultimately replaced the feudal

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was a combination of legal, economic, military, cultural, and political customs that flourished in Middle Ages, medieval Europe from the 9th to 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of struc ...

aristocratic model that had dominated Europe in the Middle Ages.

A feature of the High Middle Ages in Northern Italy was the rise of the urban communes which had broken from the control by bishops and local counts. In much of the region, the landed nobility

Landed nobility or landed aristocracy is a category of nobility in the history of various countries, for which landownership was part of their noble privileges. The landed nobility show noblesse oblige, they have duty to fulfill their social resp ...

was poorer than the urban patriarchs in the high medieval money economy, whose inflationary rise left land-holding aristocrats impoverished. The increase in trade during the early Renaissance enhanced these characteristics. The sharp decline in population led to a new class that replaced the serfs of feudalism and the rise of cities were synergistic; the demand for luxury goods, for example, led to an increase in trade, which led to greater numbers of tradesmen becoming wealthy, who, in turn, created a demand for spices and luxury goods. This change gave the merchants almost complete control of the governments of the Italian city-states, again enhancing trade. This atmosphere created a demand for visual symbols of wealth.

In other words, the middle class was born.

One of the most important effects of political control was security. Those who grew extremely wealthy in a feudal state ran the constant risk of running afoul of the monarchy and having their lands confiscated, as famously happened to Jacques Cœur in France. The northern states also kept many medieval laws that severely hampered commerce, such as those against usury

Usury () is the practice of making loans that are seen as unfairly enriching the lender. The term may be used in a moral sense—condemning taking advantage of others' misfortunes—or in a legal sense, where an interest rate is charged in e ...

, and prohibitions on trading with non-Christians. In the city-states of Italy, these laws were repealed or rewritten.

Fourteenth-century collapse

The 14th century saw a series of catastrophes that caused the European economy to go into recession. TheMedieval Warm Period

The Medieval Warm Period (MWP), also known as the Medieval Climate Optimum or the Medieval Climatic Anomaly, was a time of warm climate in the North Atlantic region that lasted from about to about . Climate proxy records show peak warmth occu ...

was ending as climate change began the Little Ice Age

The Little Ice Age (LIA) was a period of regional cooling, particularly pronounced in the North Atlantic region. It was not a true ice age of global extent. The term was introduced into scientific literature by François E. Matthes in 1939. Mat ...

. A colder climate saw agricultural output decline significantly, leading to repeated famine

A famine is a widespread scarcity of food caused by several possible factors, including, but not limited to war, natural disasters, crop failure, widespread poverty, an Financial crisis, economic catastrophe or government policies. This phenom ...

s, exacerbated by the rapid population growth of the prior era. The Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (; 1337–1453) was a conflict between the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England and Kingdom of France, France and a civil war in France during the Late Middle Ages. It emerged from feudal disputes over the Duchy ...

between England and France disrupted trade throughout northwest Europe, most notably when, in 1345, King Edward III of England

Edward III (13 November 1312 – 21 June 1377), also known as Edward of Windsor before his accession, was King of England from January 1327 until his death in 1377. He is noted for his military success and for restoring royal authority after t ...

repudiated his debts, contributing to the collapse of the two largest Florentine banks, those of the Bardi and Peruzzi

The Peruzzi family were bankers of Florence, among the leading families of the city in the 14th century, before the rise to prominence of the Medici. Their modest antecedents stretched back to the mid 11th century, according to the family's gen ...

.

In the east, war against Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

had disrupted trade routes as the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

expanded throughout the region. But most devastating was the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

that decimated the populations of the densely populated cities of Northern Italy and returned at intervals thereafter. Florence, for instance, which had a pre-plague population of 45,000 decreased over the next 47 years by 25–50%. Widespread disorder followed, including a revolt of Florentine textile workers, the '' ciompi'', in 1378.

It was during this period of instability that the first secular authors such as

It was during this period of instability that the first secular authors such as Dante

Dante Alighieri (; most likely baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri; – September 14, 1321), widely known mononymously as Dante, was an Italian Italian poetry, poet, writer, and philosopher. His ''Divine Comedy'', originally called ...

and Petrarch

Francis Petrarch (; 20 July 1304 – 19 July 1374; ; modern ), born Francesco di Petracco, was a scholar from Arezzo and poet of the early Italian Renaissance, as well as one of the earliest Renaissance humanism, humanists.

Petrarch's redis ...

lived, and the stirrings of Renaissance art were to be seen, notably in the realism of Giotto

Giotto di Bondone (; – January 8, 1337), known mononymously as Giotto, was an List of Italian painters, Italian painter and architect from Florence during the Late Middle Ages. He worked during the International Gothic, Gothic and Italian Ren ...

. These disasters would help bring about the Renaissance. As the Black Death

The Black Death was a bubonic plague pandemic that occurred in Europe from 1346 to 1353. It was one of the list of epidemics, most fatal pandemics in human history; as many as people perished, perhaps 50% of Europe's 14th century population. ...

wiped out a third of Europe's population, the resulting labour shortage increased wages and the remaining population became much wealthier, better fed, and, significantly, had more surplus money to spend on luxury goods.

As incidences of the plague began to decline in the early 15th century, Europe's devastated population once again began to grow. The new demand for products and services also helped create a growing class of bankers

A bank is a financial institution that accepts Deposit account, deposits from the public and creates a demand deposit while simultaneously making loans. Lending activities can be directly performed by the bank or indirectly through capital m ...

, merchants, and skilled artisan

An artisan (from , ) is a skilled craft worker who makes or creates material objects partly or entirely by hand. These objects may be functional or strictly decorative, for example furniture, decorative art, sculpture, clothing, food ite ...

s. The horrors of the Black Death and the seeming inability of the Church to provide relief would contribute to a decline of church influence. Additionally, the collapse of the Bardi and Peruzzi

The Peruzzi family were bankers of Florence, among the leading families of the city in the 14th century, before the rise to prominence of the Medici. Their modest antecedents stretched back to the mid 11th century, according to the family's gen ...

banks would open the way for the Medici

The House of Medici ( , ; ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first consolidated power in the Republic of Florence under Cosimo de' Medici and his grandson Lorenzo "the Magnificent" during the first half of the 15th ...

doges to rise to prominence in Florence. Roberto Sabatino Lopez argues that this economic collapse was the chief cause of the Renaissance. According to this view, in a more prosperous era, businessmen would have quickly reinvested their earnings in order to make more money in a climate favourable to investment. However, in the leaner years of the 14th century, the wealthy found few promising investment opportunities for their earnings and instead chose to spend more on culture and art. Unlike Roman texts, which had been preserved and studied in Western Europe since late antiquity, the study of ancient Greek texts was very limited in medieval Italy. Ancient Greek works on science, maths and philosophy had been studied since the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the periodization, period of European history between and ; it was preceded by the Early Middle Ages and followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended according to historiographical convention ...

in Western Europe and in the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century.

This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign o ...

(normally in translation), but Greek literary, oratorical and historical works (such as Homer

Homer (; , ; possibly born ) was an Ancient Greece, Ancient Greek poet who is credited as the author of the ''Iliad'' and the ''Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Despite doubts about his autho ...

, the Greek dramatists, Demosthenes

Demosthenes (; ; ; 384 – 12 October 322 BC) was a Greek statesman and orator in ancient Athens. His orations constitute a significant expression of contemporary Athenian intellectual prowess and provide insight into the politics and cu ...

and Thucydides

Thucydides ( ; ; BC) was an Classical Athens, Athenian historian and general. His ''History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts Peloponnesian War, the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been d ...

) were not studied in either the Latin nor the medieval Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

s; in the Middle Ages these sorts of texts were studied only by Byzantine scholars. Some argue that the Timurid Renaissance

The Timurid Renaissance was a historical period in Asian history, Asian and Islamic history spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries. Following the Islamic Golden Age, the Timurid Empire, based in Central Asia and ruled by ...

in Samarkand

Samarkand ( ; Uzbek language, Uzbek and Tajik language, Tajik: Самарқанд / Samarqand, ) is a city in southeastern Uzbekistan and among the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest continuously inhabited cities in Central As ...

was linked with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, whose conquests led to the migration of Greek scholars to Italy.The Connoisseur – Volume 219, p. 128Europe in the second millenium: a hegemony achieved? p. 58Encyclopædia Britannica, ''Renaissance'', 2008, O.Ed.Har, Michael H. ''History of Libraries in the Western World'', Scarecrow Press Incorporate, 1999,

One of the greatest achievements of Italian Renaissance scholars was to bring this entire class of Greek cultural works back into Western Europe for the first time since late antiquity.

Another popular explanation for the Italian Renaissance is the thesis, first advanced by historian Hans Baron, claims that the primary impetus of the early Renaissance was the long-running series of wars

War is an armed conflict between the armed forces of State (polity), states, or between governmental forces and armed groups that are organized under a certain command structure and have the capacity to sustain military operations, or betwe ...

between Florence and Milan. By the late 14th century, Milan had become a centralized monarchy under the control of the Visconti family. Giangaleazzo Visconti, who ruled the city from 1378 to 1402, was renowned both for his cruelty and for his abilities, and set about building an empire in Northern Italy. He launched a long series of wars, with Milan steadily conquering neighbouring states and defeating the various coalitions led by Florence that sought in vain to halt the advance. This culminated in the 140siege of Florence

when it looked as though the city was doomed to fall, before Giangaleazzo suddenly died and his empire collapsed. This thesis suggests that during these long wars, the leading figures of Florence rallied the people by presenting the war as one between the free republic and a despotic monarchy, between the ideals of the Greek and Roman Republics and those of the Roman Empire and medieval kingdoms. For Baron, the most important figure in crafting this ideology was Leonardo Bruni. This time of crisis in Florence was the period when the most influential figures of the early Renaissance were coming of age, such as Ghiberti,

Donatello

Donato di Niccolò di Betto Bardi ( – 13 December 1466), known mononymously as Donatello (; ), was an Italian Renaissance sculpture, Italian sculptor of the Renaissance period. Born in Republic of Florence, Florence, he studied classical sc ...

, Masolino, and Brunelleschi

Filippo di ser Brunellesco di Lippo Lapi (1377 – 15 April 1446), commonly known as Filippo Brunelleschi ( ; ) and also nicknamed Pippo by Leon Battista Alberti, was an Italian architect, designer, goldsmith and sculptor. He is considered to ...

. Inculcated with this republican ideology, they went on to advocate republican ideas that were to have an enormous impact on the Renaissance and the rise of the West.

Development

International relationships

Northern Italy and upper Central Italy were divided into a number of warring city-states, the most powerful beingMilan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

, Florence, Pisa

Pisa ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Tuscany, Central Italy, straddling the Arno just before it empties into the Ligurian Sea. It is the capital city of the Province of Pisa. Although Pisa is known worldwide for the Leaning Tow ...

, Siena

Siena ( , ; traditionally spelled Sienna in English; ) is a city in Tuscany, in central Italy, and the capital of the province of Siena. It is the twelfth most populated city in the region by number of inhabitants, with a population of 52,991 ...

, Genoa

Genoa ( ; ; ) is a city in and the capital of the Italian region of Liguria, and the sixth-largest city in Italy. As of 2025, 563,947 people live within the city's administrative limits. While its metropolitan city has 818,651 inhabitan ...

, Ferrara

Ferrara (; ; ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Emilia-Romagna, Northern Italy, capital of the province of Ferrara. it had 132,009 inhabitants. It is situated northeast of Bologna, on the Po di Volano, a branch channel of the main ...

, Mantua

Mantua ( ; ; Lombard language, Lombard and ) is a ''comune'' (municipality) in the Italian region of Lombardy, and capital of the Province of Mantua, eponymous province.

In 2016, Mantua was designated as the "Italian Capital of Culture". In 2 ...

, Verona

Verona ( ; ; or ) is a city on the Adige, River Adige in Veneto, Italy, with 255,131 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region, and is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and in Northeast Italy, nor ...

and Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...

. High Medieval Northern Italy was further divided by the long-running battle for supremacy between the forces of the Papacy and of the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire, also known as the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation after 1512, was a polity in Central and Western Europe, usually headed by the Holy Roman Emperor. It developed in the Early Middle Ages, and lasted for a millennium ...

: each city aligned itself with one faction or the other, yet was divided internally between the two warring parties, Guelfs and Ghibellines. Warfare between the states was common, and invasion from outside Italy was confined to intermittent sorties of Holy Roman Emperors. Renaissance politics developed from this background. Since the 13th century, as armies became primarily composed of mercenaries

A mercenary is a private individual who joins an War, armed conflict for personal profit, is otherwise an outsider to the conflict, and is not a member of any other official military. Mercenaries fight for money or other forms of payment rath ...

, prosperous city-states could field considerable forces, despite their low populations. In the course of the 15th century, the most powerful city-states annexed their smaller neighbours. Florence took Pisa in 1406, Venice captured Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

and Verona

Verona ( ; ; or ) is a city on the Adige, River Adige in Veneto, Italy, with 255,131 inhabitants. It is one of the seven provincial capitals of the region, and is the largest city Comune, municipality in the region and in Northeast Italy, nor ...

, while the Duchy of Milan

The Duchy of Milan (; ) was a state in Northern Italy, created in 1395 by Gian Galeazzo Visconti, then the lord of Milan, and a member of the important Visconti of Milan, Visconti family, which had been ruling the city since 1277. At that time, ...

annexed a number of nearby areas including Pavia

Pavia ( , ; ; ; ; ) is a town and comune of south-western Lombardy, in Northern Italy, south of Milan on the lower Ticino (river), Ticino near its confluence with the Po (river), Po. It has a population of c. 73,086.

The city was a major polit ...

and Parma

Parma (; ) is a city in the northern Italian region of Emilia-Romagna known for its architecture, Giuseppe Verdi, music, art, prosciutto (ham), Parmesan, cheese and surrounding countryside. With a population of 198,986 inhabitants as of 2025, ...

.

The first part of the Renaissance saw almost constant warfare on land and sea as the city-states vied for preeminence. On land, these wars were primarily fought by armies of mercenaries known as '' condottieri'', bands of soldiers drawn from around Europe, but especially Germany and Switzerland, led largely by Italian captains. The mercenaries were not willing to risk their lives unduly, and war became one largely of sieges and manoeuvring, occasioning few pitched battles. It was also in the interest of mercenaries on both sides to prolong any conflict, to continue their employment. Mercenaries were also a constant threat to their employers; if not paid, they often turned on their patron. If it became obvious that a state was entirely dependent on mercenaries, the temptation was great for the mercenaries to take over the running of it themselves—this occurred on a number of occasions. Neutrality was maintained with France, which found itself surrounded by enemies when Spain disputed Charles VIII's claim to the Kingdom of Naples

The Kingdom of Naples (; ; ), officially the Kingdom of Sicily, was a state that ruled the part of the Italian Peninsula south of the Papal States between 1282 and 1816. It was established by the War of the Sicilian Vespers (1282–1302). Until ...

. Peace with France ended when Charles VIII invaded Italy to take Naples.

At sea, Italian city-states sent many fleets out to do battle. The main contenders were Pisa, Genoa, and Venice, but after a long conflict, the Genoese succeeded in reducing Pisa. Venice proved to be a more powerful adversary, and with the decline of Genoese power during the 15th century Venice became pre-eminent on the seas. In response to threats from the landward side, from the early 15th century Venice developed an increased interest in controlling the ''terrafirma'' as the Venetian Renaissance

The Venetian Renaissance had a distinct character compared to the general Italian Renaissance elsewhere. The Republic of Venice was topographically distinct from the rest of the city-states of Italian Renaissance, Renaissance Italy as a result of ...

opened.

On land, decades of fighting saw Florence, Milan, and Venice emerge as the dominant players, and these three powers finally set aside their differences and agreed to the Peace of Lodi in 1454, which saw relative calm brought to the region for the first time in centuries. This peace would hold for the next forty years, and Venice's unquestioned hegemony over the sea also led to unprecedented peace for much of the rest of the 15th century. At the beginning of the 15th century, adventurers and traders such as Niccolò Da Conti (1395–1469) travelled as far as Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, southeastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of China, east of the Indian subcontinent, and northwest of the Mainland Au ...

and back, bringing fresh knowledge on the state of the world, presaging further European voyages of exploration in the years to come.

Florence under the Medici

Until the late 14th century, prior to the Medici, Florence's leading family were the House of Albizzi. In 1293 the Ordinances of Justice were enacted which effectively became the constitution of the Republic of Florence throughout the Italian Renaissance. The city's numerous luxurious palazzi were becoming surrounded by townhouses, built by the ever prospering merchant class. In 1298, one of the leading banking families of Europe, the Bonsignoris, were bankrupted and so the city of Siena lost her status as the banking centre of Europe to Florence. The main challengers of the Albizzi family were the Medicis, first under Giovanni de' Medici, and later under his son Cosimo de' Medici. The Medici controlled the Medici bank—then Europe's largest bank—and an array of other enterprises in Florence and elsewhere. In 1433, the Albizzi managed to have Cosimo exiled. The next year, however, saw a pro-Medici Signoria elected and Cosimo returned. The Medici became the town's leading family, a position they would hold for the next three centuries. Florence organized the trade routes for commodities between England and the Netherlands, France, and Italy. By the middle of the century, the city had become the banking capital of Europe and thereby obtained vast riches. In 1439,

The main challengers of the Albizzi family were the Medicis, first under Giovanni de' Medici, and later under his son Cosimo de' Medici. The Medici controlled the Medici bank—then Europe's largest bank—and an array of other enterprises in Florence and elsewhere. In 1433, the Albizzi managed to have Cosimo exiled. The next year, however, saw a pro-Medici Signoria elected and Cosimo returned. The Medici became the town's leading family, a position they would hold for the next three centuries. Florence organized the trade routes for commodities between England and the Netherlands, France, and Italy. By the middle of the century, the city had become the banking capital of Europe and thereby obtained vast riches. In 1439, Byzantine Emperor

The foundation of Constantinople in 330 AD marks the conventional start of the Eastern Roman Empire, which Fall of Constantinople, fell to the Ottoman Empire in 1453 AD. Only the emperors who were recognized as legitimate rulers and exercised s ...

John VIII Palaiologos attended a council in Florence in an attempt to unify the Eastern and Western Churches. This brought books and, especially after the fall of the Byzantine Empire in 1453, an influx of scholars to the city. Ancient Greece began to be studied with renewed interest, especially the Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

school of thought, which was the subject of an academy established by the Medici.

Florence remained a republic until 1532 (see Duchy of Florence), traditionally marking the end of the High Renaissance

In art history, the High Renaissance was a short period of the most exceptional artistic production in the Italian states, particularly Rome, capital of the Papal States, and in Florence, during the Italian Renaissance. Most art historians stat ...

in Florence, but the instruments of republican government were firmly under the control of the Medici and their allies, save during the intervals after 1494 and 1527. Cosimo and Lorenzo de' Medici

Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici (), known as Lorenzo the Magnificent (; 1 January 1449 – 9 April 1492), was an Italian statesman, the ''de facto'' ruler of the Florentine Republic, and the most powerful patron of Renaissance culture in Italy. Lore ...

rarely held official posts but were the unquestioned leaders. Cosimo was highly popular among the citizenry, mainly for bringing an era of stability and prosperity to the town. One of his most important accomplishments was negotiating the Peace of Lodi with Francesco Sforza ending the decades of war with Milan and bringing stability to much of Northern Italy. Cosimo was also an important patron of the arts, directly and indirectly, by the influential example he set.

Cosimo was succeeded by his sickly son Piero de' Medici, who died after five years in charge of the city. In 1469 the reins of power passed to Cosimo's 21-year-old grandson Lorenzo, who would become known as "Lorenzo the Magnificent." Lorenzo was the first of the family to be educated from an early age in the humanist tradition and is best known as one of the Renaissance's most important patrons of the arts. Lorenzo reformed Florence's ruling council from 100 members to 70, formalizing the Medici rule. The republican institutions continued, but they lost all power. Lorenzo was less successful than his illustrious forebears in business, and the Medici commercial empire was slowly eroded. Lorenzo continued the alliance with Milan, but relations with the papacy soured, and in 1478, Papal agents allied with the Pazzi

The Pazzi were a powerful family in the Republic of Florence. Their main trade during the fifteenth century was banking. In the aftermath of the Pazzi conspiracy in 1478, members of the family were banished from Florence and their property was ...

family in an attempt to assassinate Lorenzo. Although the Pazzi conspiracy failed, Lorenzo's young brother, Giuliano, was killed at Easter Sunday mass in the city's cathedral. The failed assassination led to a war with the Papacy and was used as justification to further centralize power in Lorenzo's hands.

Spread

Renaissance ideals first spread from Florence to the neighbouring states of

Renaissance ideals first spread from Florence to the neighbouring states of Tuscany

Tuscany ( ; ) is a Regions of Italy, region in central Italy with an area of about and a population of 3,660,834 inhabitants as of 2025. The capital city is Florence.

Tuscany is known for its landscapes, history, artistic legacy, and its in ...

such as Siena

Siena ( , ; traditionally spelled Sienna in English; ) is a city in Tuscany, in central Italy, and the capital of the province of Siena. It is the twelfth most populated city in the region by number of inhabitants, with a population of 52,991 ...

and Lucca

Città di Lucca ( ; ) is a city and ''comune'' in Tuscany, Central Italy, on the Serchio River, in a fertile plain near the Ligurian Sea. The city has a population of about 89,000, while its Province of Lucca, province has a population of 383,9 ...

. The Tuscan culture soon became the model for all the states of Northern Italy, and the Tuscan dialect

Tuscan ( ; ) is a set of Italo-Dalmatian varieties of Romance spoken in Tuscany, Corsica, and Sardinia.

Standard Italian is based on Tuscan, specifically on its Florentine dialect, and it became the language of culture throughout Italy be ...

came to predominate throughout the region, especially in literature. In 1447 Francesco Sforza came to power in Milan

Milan ( , , ; ) is a city in northern Italy, regional capital of Lombardy, the largest city in Italy by urban area and the List of cities in Italy, second-most-populous city proper in Italy after Rome. The city proper has a population of nea ...

and rapidly transformed that still medieval city into a major centre of art and learning that drew Leone Battista Alberti

Leon Battista Alberti (; 14 February 1404 – 25 April 1472) was an Italian Renaissance humanist author, artist, architect, poet, priest, linguist, philosopher, and cryptographer; he epitomised the nature of those identified now as polymaths. H ...

. Venice

Venice ( ; ; , formerly ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 islands that are separated by expanses of open water and by canals; portions of the city are li ...