Qedarites Map on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Qedarites () were an ancient

During the second half of the 9th century BC, the Qedarites were living to the east of Transjordan and to the south-east of

During the second half of the 9th century BC, the Qedarites were living to the east of Transjordan and to the south-east of

Although the Assyriologists

Although the Assyriologists

During the 9th century BCE, the Qedarite confederation was centered around the region of the

During the 9th century BCE, the Qedarite confederation was centered around the region of the  The Assyrian annexation of the kingdoms of Damascus and later of Israel would allow the Qedarites, to expand into the pastures within the settled areas of these states' former territories, which improved their position in the Arabian commercial activities. The Assyrians would allow these nomad groups to graze their camels in the settled areas and integrate them into their control structure of the border regions of Palestine and Syria, which consisted of a network of sentry stations, check posts and fortresses at key positions, and administrative and governmental centres in the cities, and which would ensure that these Arabs would remain loyal to the Assyrians and would prevent the encroachment of other Arab nomads on the settled areas; thus, several letters to Tiglath-Pileser III by two Assyrian officials stationed in the Levant, respectively named Addu-ḫati and Bēl-liqbi, mention the participation of Arabs in several caravanserais in the region, including the one located at

The Assyrian annexation of the kingdoms of Damascus and later of Israel would allow the Qedarites, to expand into the pastures within the settled areas of these states' former territories, which improved their position in the Arabian commercial activities. The Assyrians would allow these nomad groups to graze their camels in the settled areas and integrate them into their control structure of the border regions of Palestine and Syria, which consisted of a network of sentry stations, check posts and fortresses at key positions, and administrative and governmental centres in the cities, and which would ensure that these Arabs would remain loyal to the Assyrians and would prevent the encroachment of other Arab nomads on the settled areas; thus, several letters to Tiglath-Pileser III by two Assyrian officials stationed in the Levant, respectively named Addu-ḫati and Bēl-liqbi, mention the participation of Arabs in several caravanserais in the region, including the one located at

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

tribal confederation centred in their capital Dumat al-Jandal

Dumat al-Jandal (, ), also known as Al-Jawf or Al-Jouf (), which refers to Wadi Sirhan, is an ancient city of ruins and the historical capital of the Al Jawf Province, today in northwestern Saudi Arabia. It is located 37 km from Sakakah.

...

in the present-day Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

n province of Al-Jawf Al-Jawf or Al-Jouf ( ' ) may refer to:

* Al-Jawf Province, region and administrative province of Saudi Arabia

* Al Jawf Governorate, a governorate of Yemen

* Al Jawf, Libya

Al Jawf ( ') is a town in southeastern Libya, the capital of the Kufra D ...

. Attested from the 9th century BC, the Qedarites formed a powerful polity which expanded its territory throughout the 9th to 7th centuries BC to cover a large area in northern Arabia stretching from Transjordan in the west to the western borders of Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

in the east, before later consolidating into a kingdom that stretched from the eastern limits of the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

in the west till Transjordan in the east and covered much of southern Judea

Judea or Judaea (; ; , ; ) is a mountainous region of the Levant. Traditionally dominated by the city of Jerusalem, it is now part of Palestine and Israel. The name's usage is historic, having been used in antiquity and still into the pres ...

(then known as Idumea

Edom (; Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian: , ; Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomites appear in several written sources relating to the ...

), the Negev

The Negev ( ; ) or Naqab (), is a desert and semidesert region of southern Israel. The region's largest city and administrative capital is Beersheba (pop. ), in the north. At its southern end is the Gulf of Aqaba and the resort town, resort city ...

and the Sinai Peninsula

The Sinai Peninsula, or simply Sinai ( ; ; ; ), is a peninsula in Egypt, and the only part of the country located in Asia. It is between the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Red Sea to the south, and is a land bridge between Asia and Afri ...

.Stearns and Langer, 2001, p. 41.

The Qedarites played an important role in the history of the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

and North Arabia, where they enjoyed close relations with the nearby Canaanite and Aramaean

The Arameans, or Aramaeans (; ; , ), were a tribal Semitic people in the ancient Near East, first documented in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. Their homeland, often referred to as the land of Aram, originally covered cent ...

states and became important participants in the trade of spices and aromatics imported into the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

and the Mediterranean world from South Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

. Having engaged in both friendly ties and hostilities with the Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

n powers such as the Neo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

and Neo-Babylonian

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to ancient Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC ...

empires, the Qedarites eventually became integrated within the structure of the Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian peoples, Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, i ...

. Closely associated with the Nabataeans

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ) were an ancient Arabs, Arab people who inhabited northern Arabian Peninsula, Arabia and the southern Levant. Their settlements—most prominently the assumed capital city o ...

, who may have eventually assimilated the Qedarites at the end of the Hellenistic period.

The Qedarites also feature within the scriptures of Abrahamic religions

The term Abrahamic religions is used to group together monotheistic religions revering the Biblical figure Abraham, namely Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The religions share doctrinal, historical, and geographic overlap that contrasts them wit ...

, where they appear in the Hebrew and Christian Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

and the Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

as the eponymous descendants of '' Qaydar'', the second son of Isma'il

Ishmael ( ) is regarded by Muslims as an Islamic prophet. Born to Abraham and Hagar, he is the namesake of the Ishmaelites, who were descended from him. In Islam, he is associated with Mecca and the construction of the Kaaba within today's Mas ...

, himself the son of Ibrahim. Within Islamic tradition, some scholars claim that the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

was descended from Isma'il through Qaydar.

Name

The name of the Qedarites is recorded inOld Arabic

Old Arabic is the name for any Arabic language or dialect continuum before Islam. Various forms of Old Arabic are attested in scripts like Safaitic, Hismaic, Nabataean alphabet, Nabatean, and even Greek alphabet, Greek.

Alternatively, the term ha ...

inscriptions written using the Ancient North Arabian

Languages and scripts in the 1st Century Arabia

Ancient North Arabian (ANA) is a collection of scripts and a language or family of languages under the North Arabian languages branch along with Old Arabic that were used in north and central Ara ...

script as (), and in Classical Arabic

Classical Arabic or Quranic Arabic () is the standardized literary form of Arabic used from the 7th century and throughout the Middle Ages, most notably in Umayyad Caliphate, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphate, Abbasid literary texts such as poetry, e ...

as () and ().

The name of the Qedarites is recorded in Aramaic

Aramaic (; ) is a Northwest Semitic language that originated in the ancient region of Syria and quickly spread to Mesopotamia, the southern Levant, Sinai, southeastern Anatolia, and Eastern Arabia, where it has been continually written a ...

as () in Achaemenid and Hellenistic period ostraca found at Maresha

Maresha was an Iron Age city mentioned in the Hebrew Bible, whose remains have been excavated at Tell Sandahanna (Arabic name), an Tell (archaeology), archaeological mound or 'tell' renamed after its identification to Tel Maresha (). The ancient ...

.

Assyrian records have transcribed in Neo-Assyrian Akkadian various variants of the name of the Qedar tribe under the forms of , , , , , , , and . In one Neo-Assyrian letter, the Qedarites are referred to as , reflecting the use of a voiced , similarly to the one used in the present-day Hejazƒ´ dialect of Arabic.

In the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Hebrew Hebrew (; '' ø√ébrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

as (; ).

The Qedarites were also mentioned in . '' Hebrew Hebrew (; '' ø√ébrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

Old South Arabian

Ancient South Arabian (ASA; also known as Old South Arabian, Epigraphic South Arabian, ·π¢ayhadic, or Yemenite) is a group of four closely related extinct languages ( Sabaean/Sabaic, Qatabanic, Hadramitic, Minaic) spoken in the far southern ...

inscriptions as the ( or ).

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

sources mention the Qedarites as the .

Geography

During the second half of the 9th century BC, the Qedarites were living to the east of Transjordan and to the south-east of

During the second half of the 9th century BC, the Qedarites were living to the east of Transjordan and to the south-east of Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

, within the southwestern Syrian Desert

The Syrian Desert ( ''Bādiyat Ash-Shām''), also known as the North Arabian Desert, the Jordanian steppe, or the Badiya, is a region of desert, semi-desert, and steppe, covering about of West Asia, including parts of northern Saudi Arabia, ea ...

in the region of the Wadi Sirhan

Wadi Sirhan (; translation: "Valley of Sirhan") is a wide depression in the northwestern Arabian Peninsula. It runs from the Aljouf Oasis in Saudi Arabia northwestward into Jordan. It historically served as a major trade and transportation rou ...

, more specifically in the Jauf depression in its eastern part, where was located the Qedarites' main centre of D≈´mat or ad-D≈´mat (; recorded in Akkadian as ). D≈´mat's location halfway between Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

and Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

and halfway between the Persian Gulf

The Persian Gulf, sometimes called the Arabian Gulf, is a Mediterranean seas, mediterranean sea in West Asia. The body of water is an extension of the Arabian Sea and the larger Indian Ocean located between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula.Un ...

and the Gulf of Aqaba

The Gulf of Aqaba () or Gulf of Eilat () is a large gulf at the northern tip of the Red Sea, east of the Sinai Peninsula and west of the Arabian Peninsula. Its coastline is divided among four countries: Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

...

, as well as its relative water richness and its orchards made it the most important oasis of all North Arabia and gave it the position of being a main stop on the roads which connected Al-Hirah

Al-Hira ( Middle Persian: ''Hērt'' ) was an ancient Lakhmid Arabic city in Mesopotamia located south of what is now Kufa in south-central Iraq.

The Sasanian Empire, Sasanian government established the Lakhmid state (Al-Hirah) on the edge of the ...

, Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

and Yathrib

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

.

At the time of the 7th century BC, the Qedarites had expanded eastwards so that their kingdom adjoined the western border of Babylonia

Babylonia (; , ) was an Ancient history, ancient Akkadian language, Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Kuwait, Syria and Iran). It emerged as a ...

, In the western Syrian Desert, the Qedarites adjoined the western section of the Fertile Crescent

The Fertile Crescent () is a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East, spanning modern-day Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria, together with northern Kuwait, south-eastern Turkey, and western Iran. Some authors also include ...

on the eastern border of the Levant, and before the conquest of Syria by the Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

, the neighbours of the Qedarite Arabs to the west were the Aramaean

The Arameans, or Aramaeans (; ; , ), were a tribal Semitic people in the ancient Near East, first documented in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. Their homeland, often referred to as the land of Aram, originally covered cent ...

kingdom of Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

and the Canaanite kingdoms of Ammon

Ammon (; Ammonite language, Ammonite: ê§èê§åê§ç '' ªAmƒÅn''; '; ) was an ancient Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking kingdom occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Wadi Mujib, Arnon and Jabbok, in present-d ...

, Edom

Edom (; Edomite language, Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian language, Akkadian: , ; Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomi ...

, Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, and Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

. After the Neo-Babylonian Empire

The Neo-Babylonian Empire or Second Babylonian Empire, historically known as the Chaldean Empire, was the last polity ruled by monarchs native to ancient Mesopotamia. Beginning with the coronation of Nabopolassar as the King of Babylon in 626 BC a ...

destroyed the Canaanite kingdoms of Ammon

Ammon (; Ammonite language, Ammonite: ê§èê§åê§ç '' ªAmƒÅn''; '; ) was an ancient Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking kingdom occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Wadi Mujib, Arnon and Jabbok, in present-d ...

, Judah, and Moab, followed by the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

Achaemenid

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire, also known as the Persian Empire or First Persian Empire (; , , ), was an Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great of the Achaemenid dynasty in 550 BC. Based in modern-day Iran, it was the large ...

's annexation of Babylonia, the Qedarites expanded westwards into the eastern and southern Levant until their territory included the northern Sinai and they controlled the desert region which bordered ancient Israel and the eastern border of Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and of the Nile Delta

The Nile Delta (, or simply , ) is the River delta, delta formed in Lower Egypt where the Nile River spreads out and drains into the Mediterranean Sea. It is one of the world's larger deltas—from Alexandria in the west to Port Said in the eas ...

.

Identification

The Qedarites were an Arab tribal confederation who were closely related to the other ancient Arabian populations of North Arabia and the Syrian Desert. Under the reigns of theNeo-Assyrian

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

kings Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (, also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: '' æƒísar-·∏§add≈çn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 681 to 669 BC. The third king of the S ...

and Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (, meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir")—or Osnappar ()—was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the th ...

, Assyrian records referred to the Qedarites as being almost synonymous with the Arabs as a whole.

Friedrich Delitzsch

Friedrich Delitzsch (; 3 September 1850 – 19 December 1922) was a German Assyriologist. He was the son of Lutheran theologian Franz Delitzsch (1813–1890).

Born in Erlangen, he studied in Leipzig and Berlin, gaining his habilitation in 1874 as ...

, R.C. Thompson and Julius Lewy had identified the Qedarite tribe of the () with the Biblical Ishmaelites

The Ishmaelites (; ) were a collection of various Arab tribes, tribal confederations and small kingdoms described in Abrahamic tradition as being descended from and named after Ishmael, a prophet according to the Quran, the first son of Abraha ...

() and considered the Akkadian name as derivative of , the scholar Israel Eph øal has criticised this identification on several grounds:

* Eph øal's criticism of the identification on historical grounds rests on three arguments:

** The term "Ishmaelites" only appear in Biblical sources relating to the period before the reign of the Israelite

Israelites were a Hebrew language, Hebrew-speaking ethnoreligious group, consisting of tribes that lived in Canaan during the Iron Age.

Modern scholarship describes the Israelites as emerging from indigenous Canaanites, Canaanite populations ...

king David

David (; , "beloved one") was a king of ancient Israel and Judah and the third king of the United Monarchy, according to the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament.

The Tel Dan stele, an Aramaic-inscribed stone erected by a king of Aram-Dam ...

;

** The term "Arabs" starts appearing for the first time in Mesopotamian sources the middle of the 9th century BCE;

** Neither the Assyrian nor the Biblical sources ever identify or even connect the names "Arabs" and Ishmaelites.

* Eph øal's criticism of the identification on phonetic grounds rests on two arguments:

** the name is already attested in early Akkadian under the forms and (), () and () and in later Akkadian under the forms () and ();

** likewise, the Hebrew form of Akkadian would have been () or () rather than ().

History

Neo-Assyrian period

During the 9th century BCE, the Qedarite confederation was centered around the region of the

During the 9th century BCE, the Qedarite confederation was centered around the region of the Wadi Sirhan

Wadi Sirhan (; translation: "Valley of Sirhan") is a wide depression in the northwestern Arabian Peninsula. It runs from the Aljouf Oasis in Saudi Arabia northwestward into Jordan. It historically served as a major trade and transportation rou ...

, and it had commercial interests in the trade and border routes of the Syrian Desert

The Syrian Desert ( ''Bādiyat Ash-Shām''), also known as the North Arabian Desert, the Jordanian steppe, or the Badiya, is a region of desert, semi-desert, and steppe, covering about of West Asia, including parts of northern Saudi Arabia, ea ...

. To the west, the borderlands of the Qedarites bordered on the powerful kingdoms of Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

and Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

in the west, although the Qedarites themselves were independent of Damascene hegemony. The Qedarite king Gindibu æ during this period enjoyed good relations with the Aramaean kingdom of Zobah

Zobah or Aram-Zobah () was an early Aramean state and former vassal kingdom of Israel mentioned in the Hebrew Bible that extended northeast of David's realm according to the Hebrew Bible.

Alexander Kirkpatrick, in the Cambridge Bible for School ...

, and, the Qedarites being transhumant nomads, they would bring their flocks to the summer pastures of the lower Orontes or the Anti-Lebanon mountains

The Anti-Lebanon mountains (), also called Mount Amana, are a southwest–northeast-trending, c. long mountain range that forms most of the border between Syria and Lebanon. The border is largely defined along the crest of the range. Most of ...

in Zobah while spending the winter in the regions to the east and south-east of these mountains.

The earliest known activities of the Qedarites date from between 850 and 800 BC, when their king Gindibu æ allied with his powerful neighbours, the kings Hadadezer

Hadadezer ( ; " he godHadad is help"); also known as Adad-Idri (), and possibly the same as Bar- or Ben-Hadad II, was the king of Aram-Damascus between 865 and 842 BC.

The Hebrew Bible states that Hadadezer (which the biblical text calls ''ben H ...

of Aram-Damascus and Ahab

Ahab (; ; ; ; ) was a king of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), the son and successor of King Omri, and the husband of Jezebel of Sidon, according to the Hebrew Bible. He is depicted in the Bible as a Baal worshipper and is criticized for causi ...

of Israel, against the rising Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Neo-Assyrian Empire was the fourth and penultimate stage of ancient Assyrian history. Beginning with the accession of Adad-nirari II in 911 BC, the Neo-Assyrian Empire grew to dominate the ancient Near East and parts of South Caucasus, Nort ...

. Although Gindibu æ's kingdom was not in danger of being attacked by the Assyrians, the Qedarite rulers participated in the trade which passed through Damascus and Tyre, and Damascus and Israel controlled crucial parts of the trade routes as well as the pastures and water sources which were of vital importance to the nomadic Qedarites, especially in drought periods. This meant that the rise of Assyrian power in the 9th century BCE put the desert and border routes where Gindibu æ had economic interests under threat of Assyrian disruptions, fearing which Gindibu æ led 1000 camelry troops at the battle of Battle of Qarqar

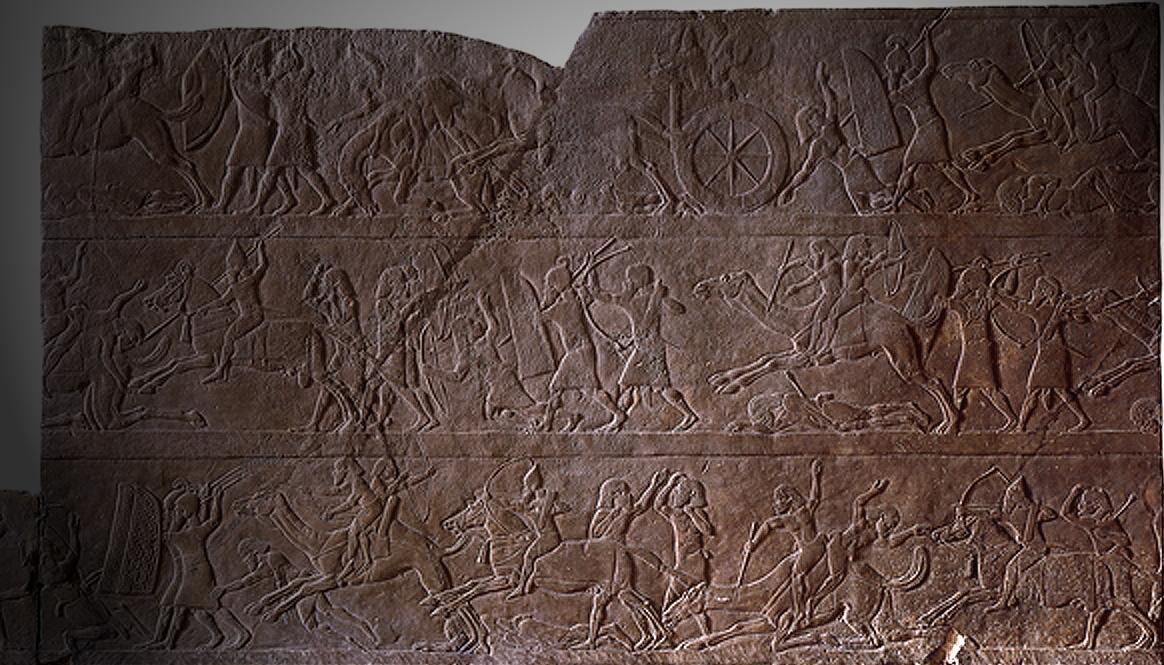

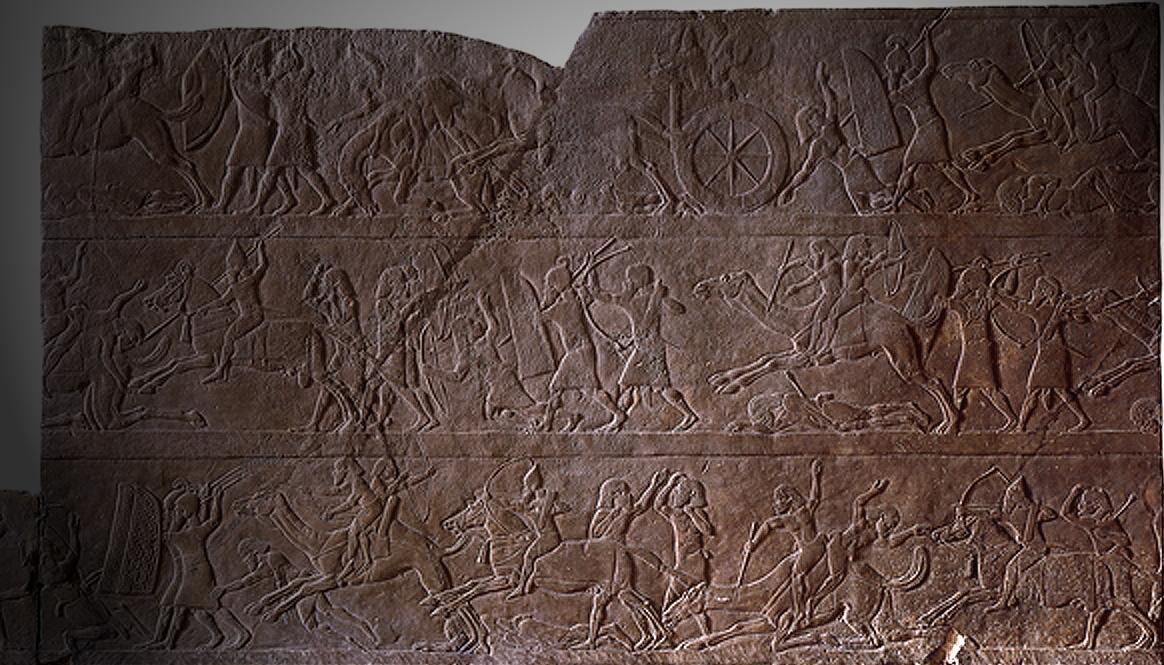

The Battle of Qarqar (or ·∏≤ar·∏≥ar) was fought in 853 BC when the army of the Neo-Assyrian Empire led by Emperor Shalmaneser III encountered an allied army of eleven kings at Qarqar led by Hadadezer, called in Assyrian ''Adad-idir'' and possib ...

in 853 BCE on the side of the alliance led by Aram-Damascus and Israel against Shalmaneser III

Shalmaneser III (''≈ÝulmƒÅnu-a≈°arƒìdu'', "the god Shulmanu is pre-eminent") was king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 859 BC to 824 BC.

His long reign was a constant series of campaigns against the eastern tribes, the Babylonians, the nations o ...

of Assyria.

Before the ascent of Assyrian hegemony, the Qedarite confederation was a polity of significant importance in the region of the Syrian Desert, and, beginning in the 8th and lasting until the 5th or 4th centuries BCE, the Qedarites were the hegemons among the Syrian Desert nomads, dominating the northwestern section of the Arabian peninsula in alliance with the local rulers of the kingdom of Dadān

Lihyan (, ''Liḥyān''; Greek: Lechienoi), also called Dadān or Dedan, was an ancient Arab kingdom that played a vital cultural and economic role in the north-western region of the Arabian Peninsula and used Dadanitic language. The kingdom flo ...

.

The alliance of Qarqar soon fell apart after Hadadezer of Damascus died and was succeeded by his son Hazael

Hazael (; ; Old Aramaic ê§áê§Üê§Äê§ã ''·∏§z îl'') was a king of Aram-Damascus mentioned in the Bible. Under his reign, Aram-Damascus became an empire that ruled over large parts of contemporary Syria and Israel-Samaria. While he was likely ...

, who declared war on Israel and killed its king Jehoram and the Judahite king Ahaziah near Ramoth-Gilead

Ramoth-Gilead (, meaning "Heights of Gilead"), was a Levitical city and city of refuge east of the Jordan River in the Hebrew Bible, also called "Ramoth in Gilead" (; ; ) or "Ramoth Galaad" in the Douay–Rheims Bible. It was located in the trib ...

in 842 BC; the consequent ascension of Jehu

Jehu (; , meaning "Jah, Yah is He"; ''Ya'√∫a'' 'ia-√∫-a'' ) was the tenth king of the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria), northern Kingdom of Israel since Jeroboam I, noted for exterminating the house of Ahab. He was the son of Jehoshaphat (father ...

to the throne of Israel did not end the hostilities between Damascus and Israel. Despite this significant change, the Qedarites continued enjoying good relations with Damascus.

Shalmaneser III later campaigned to Damascus

Damascus ( , ; ) is the capital and List of largest cities in the Levant region by population, largest city of Syria. It is the oldest capital in the world and, according to some, the fourth Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. Kno ...

and Mount Hauran

The Hauran (; also spelled ''Hawran'' or ''Houran'') is a region that spans parts of southern Syria and northern Jordan. It is bound in the north by the Ghouta oasis, to the northeast by the al-Safa field, to the east and south by the Harrat ...

in 841 BCE, but his inscriptions mentioned neither the Qedarite kingdom nor Gindibu æ himself or any successor of his. The Qedarites were not mentioned either in the list of rulers, including those of distant places such as Philistia

Philistia was a confederation of five main cities or pentapolis in the Southwest Levant, made up of principally Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, Gath, and for a time, Jaffa (part of present-day Tel Aviv-Yafo).

Scholars believe the Philist ...

, Edom

Edom (; Edomite language, Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian language, Akkadian: , ; Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomi ...

, and Israel

Israel, officially the State of Israel, is a country in West Asia. It Borders of Israel, shares borders with Lebanon to the north, Syria to the north-east, Jordan to the east, Egypt to the south-west, and the Mediterranean Sea to the west. Isr ...

, who paid tribute to Adad-nirari III

Adad-nīrārī III (also Adad-nārārī, meaning "Adad (the storm god) is my help") was a King of Assyria from 811 to 783 BC.

Family

Adad-nīrārī was a son and successor of king Shamshi-Adad V, and was apparently quite young at the time of hi ...

after the latter's defeat of Bar-Hadad III of Damascus in 796 BCE. This reason for absence the Assyrian records is that the kingdom of Gindibu æ was far from the campaign routes of the Assyrians during the later 9th century BCE.

Following the rise in the Armenian highlands of a powerful rival of the Neo-Assyrian Empire the form of the kingdom of Urartu

Urartu was an Iron Age kingdom centered around the Armenian highlands between Lake Van, Lake Urmia, and Lake Sevan. The territory of the ancient kingdom of Urartu extended over the modern frontiers of Turkey, Iran, Iraq, and Armenia.Kleiss, Wo ...

, which, just like Assyria, was interested in the rich states of northern Syria

Syria, officially the Syrian Arab Republic, is a country in West Asia located in the Eastern Mediterranean and the Levant. It borders the Mediterranean Sea to the west, Turkey to Syria–Turkey border, the north, Iraq to Iraq–Syria border, t ...

, in 743 BC the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III started a series of campaigns in Syria which would result in this region's absorption into the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and the first phase of which was the defeat in that very year of an alliance consisting of Urartu and the Aramaean states of Melid

Arslantepe, also known as Melid, was an ancient city on the Tohma River, a tributary of the upper Euphrates rising in the Taurus Mountains. It has been identified with the modern archaeological site of Arslantepe near Malatya, Turkey.

It was na ...

, Gurgum, Kummu·∏´, Bit Agusi

Bit Agusi or Bit Agushi (also written Bet Agus) was an ancient Aramaean Syro-Hittite state, established by Gusi of Yakhan at the beginning of the 9th century BC. It had included the cities of Arpad, Nampigi (Nampigu) and later on Aleppo Arpad wa ...

, and øUmqi, after which he besieged Bit Agusi's capital of Arpad, which was Urartu's principal ally, for two years before capturing it. While Tiglath-Pileser III was campaigning against Urartu in 739 BC, the Levantine states formed a new alliance, headed by the king ''Azriya'u'' of ·∏§amat, and including various Phoenician cities ranging from Arqa

Arqa (; ) is a Lebanese village near Miniara in Akkar Governorate, Lebanon, 22 km northeast of Tripoli, near the coast.

The town was a notable city-state during the Iron Age. The city of ''Irqata'' sent 10,000 soldiers to the coalition a ...

to ·π¢umur and multiple Aramaean states from Sam æal

Zincirli Höyük is an archaeological site located in the Anti-Taurus Mountains of modern Turkey's Gaziantep Province. During its time under the control of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (c. 700 BC) it was called, by them, Sam'al. It was founded at leas ...

in the north to Ḥamat in the south, which was defeated by Tiglath-Pileser III in 738 BC.

After this triumph of Assyrian hegemony in the western Fertile Crescent, the rulers of Damascus, Tyre and Israel accepted Assyrian overlordship and paid tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III. Since the Qedarite rulers participated in the trade which passed through Damascus and Tyre, they sought to preserve the Arabian commercial activities and the revenues that they acquired from these, and consequently the Qedarite queen Zabibe

Zabibe (also transliterated Zabibi, Zabiba, Zabibah; ''Zabibê'') was a queen of Qedar who reigned for five years between 738 and 733 BC. She was a vassal of Tiglath-Pileser III, king of Assyria, and is mentioned in the Annals of Tiglath-Pileser ...

joined the kings Rezin

Rezin of Aram (, ; ; *''Raḍyan''; ) was an Aramean King ruling from Damascus during the 8th century BC. During his reign, he was a tributary of King Tiglath-Pileser III of Assyria. Lester L. Grabbe, ''Ancient Israel: What Do We Know and How ...

of Damascus, Menahem

Menahem or Menachem (, "consoler" or "comforter"; ''Meniḫîmme'' 'me-ni-ḫi-im-me'' Greek: Μεναέμ ''Manaem'' in the Septuagint, Μεναέν ''Manaen'' in Aquila; ; full name: , ''Menahem son of Gadi'') was the sixteenth king of the ...

of Israel, Hiram II of Tyre, as well as other various rulers from southern Anatolia, Syria and Phoenicia in acknowledging Assyrian hegemony and paying tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III in 738 BC. The tribute of Zabibe consisted of camels, but did not include frankincense or perfumes as the Qedarites would later offer the Assyrians because they had not yet become participants in the trade of aromatics produced in South Arabia. Tiglath-Pileser III's inscriptions recording this tribute payment constitutes the first explicit mention of the Qedarites by name.

During the 8th century itself, the North Arabian region acquired increased economic importance, with the northern Hejaz

Hejaz is a Historical region, historical region of the Arabian Peninsula that includes the majority of the western region of Saudi Arabia, covering the cities of Mecca, Medina, Jeddah, Tabuk, Saudi Arabia, Tabuk, Yanbu, Taif and Al Bahah, Al-B ...

becoming a transit zone for the trade of goods imported from 'Asir

Asir, officially the Aseer Province, is a province of Saudi Arabia in southern Arabia. It has an area of , and an estimated population of 2,024,285 (in 2022). Asir is bounded by the Mecca Province to the north and west, al-Bahah Province to the ...

and from Africa across the Red Sea. This, in turn, led to increasing interest to control this region by the Assyrians.

Once Tiglath-Pileser III had returned to Assyria, the king Rezin of Damascus organised an anti-Assyrian alliance in Syria which was supported by Pekah

Pekah (, ''Peqaḥ''; ''Paqaḫa'' 'pa-qa-ḫa'' ) was the eighteenth and penultimate king of Israel. He was a captain in the army of king Pekahiah of Israel, whom he killed to become king. Pekah was the son of Remaliah.

Pekah became king in ...

of Israel and Hiram II of Tyre, and which started a revolt against Assyrian hegemony by the cities on the coast of the Levant. Tiglath-Pileser III retaliated by campaigning in 734 BC against the southern Levantine coast until the Brook of Egypt

The Brook of Egypt () is a wadi identified in the Hebrew Bible as forming the southernmost border of the Land of Israel. A number of scholars in the past identified it with Wadi al-Arish, an ephemeral river flowing into the Mediterranean sea nea ...

and successfully managed to establish control over the commercial activities between the Phoenicia

Phoenicians were an Ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syria, Syrian ...

ns, the Egyptians and the Philistines

Philistines (; LXX: ; ) were ancient people who lived on the south coast of Canaan during the Iron Age in a confederation of city-states generally referred to as Philistia.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that the Philistines origi ...

. Among the many rulers in the western Fertile Crescent who pledged allegiance to Tiglath-Pileser III as result of this campaign in Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

was the Qedarite queen ≈Ýam≈°i

≈Ýamsi (Old Arabic: ; ) was an Arab queen who reigned in the Ancient Near East, in the 8th century BCE. She succeeded Queen Zabibe (Arabic meaning "Raisin"). Tiglath-Pileser III, son of Ashur-nirari V and king of Assyria, was the first foreign ...

.

Tiglath-Pileser III's campaign had not only disrupted the interests of Tyre, Damascus, Israel and the Qedarites but also resulted in the formation of a pro-Assyrian alliance consisting of Arwad

Arwad (; ), the classical antiquity, classical Aradus, is a town in Syria on an eponymous List of islands of Syria, island in the Mediterranean Sea. It is the administrative center of the Arwad nahiyah, Subdistrict (''nahiyah''), of which it is ...

, Ashkelon

Ashkelon ( ; , ; ) or Ashqelon, is a coastal city in the Southern District (Israel), Southern District of Israel on the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean coast, south of Tel Aviv, and north of the border with the Gaza Strip.

The modern city i ...

and Gaza, soon joined by Judah, Ammon

Ammon (; Ammonite language, Ammonite: ê§èê§åê§ç '' ªAmƒÅn''; '; ) was an ancient Semitic languages, Semitic-speaking kingdom occupying the east of the Jordan River, between the torrent valleys of Wadi Mujib, Arnon and Jabbok, in present-d ...

, Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

, and Edom, who became players in Syrian politics with the goal of countering the anti-Assyrian alliance led by Damascus, Israel, Qedar and Tyre. However, the alliance headed by Damascus continued its anti-Assyrian activities, which caused the pro-Assyrian alliance to disintegrate, with Ashkelon and Edom soon defecting to the pro-Assyrian side. And since the Qedarites were still participating in the trade networks passing through Damascus and Israel, who themselves controlled important parts of the Arabian commercial route as well as pasture and water sources on which the Qedarites depended, especially during periods of drought, ≈Ýam≈°i followed Rezin, Pekah, and Hiram II in rebelling against Assyrian authority in 733 BC.

During the reign of Tiglath-Pileser III itself, the Qedarites invaded Moab and killed the inhabitants of its capital city of Qir-M≈ç æƒÅb.

When Judah remained loyal to Assyria, Rezin and Pekah attacked it, starting the Syro-Ephraimite War

The Syro-Ephraimite War was a conflict which took place in the 8th century BCE between the Kingdom of Judah and an alliance of Aram-Damascus and the Kingdom of Israel based in Samaria.

One theory states that the war's sole goal was to force j ...

, in retaliation of which Tiglath-Pileser III in turn attacked Damascus in 733 and 732 BC. As part of his intervention in Syria, Tiglath-Pileser III also attacked and defeated the Qedarites in the region of Mount Saqurri (Often identified with Jabal al-Druze

Jabal al-Druze (), is an elevated volcanic region in the Suwayda Governorate of southern Syria. Most of the inhabitants of this region are Druze, and there are also significant Christian communities. Safaitic inscriptions were first found in ...

), forcing ≈Ýam≈°i to flee to the Wadi Sirhan, and taking significant spoils from them, including spices, which are first mentioned in relation with the Qedarites in Tiglath-Pileser III's records relating to this campaign, and cultic utensils like the resting places of the Qedarite gods as well as their goddess's sceptres. While Rezin would be executed and his kingdom annexed by the Assyrians and Peqa·∏• was assassinated, Tiglath-Pileser III allowed ≈Ýam≈°i to retain her position as the ruler of the Qedarites and appointed an Arab as (overseer for the count of Assyria) in Qedar to prevent her from providing aid to Damascus during the campaign in which the Assyrians annexed its territory, and to manage the Qedarites' commercial activities. This mild treatment of ≈Ýam≈°i was due to the fact that the Qedarites by then had become wealthier and more powerful, and the Assyrians were interested in products, such as camels, cattle and spices which they could obtain from the Qedarites, as well as in preserving the administrative and social structures of the peoples of the Assyrian border regions who played an important role in international commerce and thus ensured the stability of the Neo-Assyrian Empire's economy. The arrangement between the Assyrians and the Qedarites established at the end of Tiglath-Pileser III's campaign in Palestine satisfied both parties enough that ≈Ýam≈°i remained loyal to Assyria and later paid Tiglath-Pileser III a tribute of 125 white camels. Among the other Arabian populations around the southern Levant who offered tribute to Tiglath-Pileser III after his campaign were the Mas æaya. the Tayma

Tayma (; Taymanitic: ê™âê™Éê™í, , vocalized as: ) or Tema is a large oasis with a long history of settlement, located in northwestern Saudi Arabia at the point where the trade route between Medina and Dumah (Sakakah) begins to cross the Na ...

nites, Sabaean traders established in the Hejaz, the ·∏™aipaya, the Badanaya, the Hatiaya, and the Idiba æilaya.

The Assyrian annexation of the kingdoms of Damascus and later of Israel would allow the Qedarites, to expand into the pastures within the settled areas of these states' former territories, which improved their position in the Arabian commercial activities. The Assyrians would allow these nomad groups to graze their camels in the settled areas and integrate them into their control structure of the border regions of Palestine and Syria, which consisted of a network of sentry stations, check posts and fortresses at key positions, and administrative and governmental centres in the cities, and which would ensure that these Arabs would remain loyal to the Assyrians and would prevent the encroachment of other Arab nomads on the settled areas; thus, several letters to Tiglath-Pileser III by two Assyrian officials stationed in the Levant, respectively named Addu-ḫati and Bēl-liqbi, mention the participation of Arabs in several caravanserais in the region, including the one located at

The Assyrian annexation of the kingdoms of Damascus and later of Israel would allow the Qedarites, to expand into the pastures within the settled areas of these states' former territories, which improved their position in the Arabian commercial activities. The Assyrians would allow these nomad groups to graze their camels in the settled areas and integrate them into their control structure of the border regions of Palestine and Syria, which consisted of a network of sentry stations, check posts and fortresses at key positions, and administrative and governmental centres in the cities, and which would ensure that these Arabs would remain loyal to the Assyrians and would prevent the encroachment of other Arab nomads on the settled areas; thus, several letters to Tiglath-Pileser III by two Assyrian officials stationed in the Levant, respectively named Addu-ḫati and Bēl-liqbi, mention the participation of Arabs in several caravanserais in the region, including the one located at Hisyah

Hisyah (, also spelled Hasya, Hasiyah, Hesa or Hessia) is a town in central Syria, administratively part of the Homs Governorate, located about 35 kilometers south of Homs. Situated on the M5 Highway between Homs and Damascus, nearby localities in ...

; moreover, one Arabian chief from Tiglath-Pileser III's time, named Badi æilu, was given a grazing permit and appointed as an official of the Assyrian administration as part of this policy. This in turn allowed the Arabs integrated into the Assyrian administration to further expand into the Levantine settled regions around Damascus and the Anti-Lebanon

The Anti-Lebanon mountains (), also called Mount Amana, are a southwest–northeast-trending, c. long mountain range that forms most of the border between Syria and Lebanon. The border is largely defined along the crest of the range. Most of ...

until the Valley of Lebanon.

In 729 BC, Tiglath-Pileser III proclaimed himself King of Babylon, thus marking the renewal of the importance of southern Mesopotamia and starting the resurgence of Babylon. This revival was itself related to the formation of new commercial links between Babylonia and the Persian Gulf and its surrounding regions, which would eventually lead to Aramaeans as well as Arabs moving into the region.

After the annexation of the kingdom of Israel to the Neo-Assyrian Empire by the Assyrian king Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

in , the Assyrians transferred some Arabs to the territory of the former kingdom as well as to the southern border regions of Palestine, and some sedentary Qedarites might have been present among the Arabians resettled by the Assyrians as colonists in the hill country around Samaria

Samaria (), the Hellenized¬Ýform of¬Ýthe Hebrew name Shomron (), is used as a historical and Hebrew Bible, biblical name for the central region of the Land of Israel. It is bordered by Judea to the south and Galilee to the north. The region is ...

to perform economic activities as part of the Assyrian diversion of some of the Spice trade to Tyre through Samaria so as to increase both Assyrian control over it and imperial revenue from this commercial traffic. These Arabian settlers introduced the cult of the god Ashima in the region of Samaria.

Due to the revival of Babylonia which had started under Tiglath-Pileser III, nomads had also migrated over the course of the middle 8th century BC to the east into Babylonia, where they settled down and either founded their own settlements or became the majority population in pre-existing local settlements there. These Arabs appear to have originated from the Wadi Sirhan region, passing through the Jawf depression and along the road near the city of Babylon which went from Yathrib to Borsippa

Borsippa (Sumerian language, Sumerian: BAD.SI.(A).AB.BAKI or Birs Nimrud, having been identified with Nimrod) is an archeological site in Babylon Governorate, Iraq, built on both sides of a lake about southwest of Babylon on the east bank of th ...

, before finally settling into Bit-Dakkuri and Bit-Amukkani, but not Bit-Yakin or the region of the Persian Gulf; the name of one of these settlements, Qidrina, located in the territory of Bit-Dakkuri, suggests that these newcomers might have been connected with the Qedarites, and the Arabian population in Babylonia remained in close contact with the Qedarites in the desert, who by this time had expanded eastwards so that they adjoined the western border of Babylonia. These Arabians might have been settled in Mesopotamia by the Assyrian kings themselves, especially by Sargon II and his son and successor Sennacherib, and some of these might have in turn been resettled in Media

Media may refer to:

Communication

* Means of communication, tools and channels used to deliver information or data

** Advertising media, various media, content, buying and placement for advertising

** Interactive media, media that is inter ...

as camel tamers by the Assyrians after they had introduced the use of the dromedary

The dromedary (''Camelus dromedarius''), also known as the dromedary camel, Arabian camel and one-humped camel, is a large camel of the genus '' Camelus'' with one hump on its back. It is the tallest of the three camel species; adult males sta ...

in this region.

In 716 BC, the Qedarite queen ≈Ýam≈°i joined a local Egyptian kinglet of the Nile Delta and the Yi·πØa ø æamar Watar I of Saba æ in offering lavish presents consisting of gold, precious stones, ivory, willow seeds, aromatics, horses, and camels to the Assyrian king Sargon II to normalise relations with Assyria and to preserve and expand their commercial relations with the economic and structures of the newly established western borderlands of the Neo-Assyrian Empire following the Assyrian annexation of Damascus and Israel. Assyrian records referred to these three rulers as the "kings of the seashore and the desert," reflecting their influence in the trade networks which spanned North Arabia, the Syrian desert, and the northern part of the Sinai.

In the late 8th century BC, shortly before 700 BC, the domestication of the camels had made it possible for the Qedarites populations to travel further south the Arabian Peninsula, thus competing with the regional maritime trade routes. During the 7th century BC, this ability to travel so far to the south led to the establishment of the import of frankincense from the kingdom of Saba æ, thus forming the incense trade route

The incense trade route was an ancient network of major land and sea trading routes linking the Mediterranean world with eastern and southern sources of incense, spices and other luxury goods, stretching from Mediterranean ports across the Levan ...

, and further increasing the commercial importance of the northern Hejaz and of Palestine and Syria and the adjoining regions. And, under Sargon II, the Arabs within Syria, who may or may not have included Qedarites, were continuing to participate in the caravan traffic in close cooperation with the Assyrian authorities, especially in the area of the Homs

Homs ( ; ), known in pre-Islamic times as Emesa ( ; ), is a city in western Syria and the capital of the Homs Governorate. It is Metres above sea level, above sea level and is located north of Damascus. Located on the Orontes River, Homs is ...

plain, which itself extended eastwards towards Palmyra, and where these Arabs were allowed to graze their camels. As part of this collaboration, the Assyrian official Bēl-liqbi, who was stationed in Ṣupite, wrote a letter to Sargon II demanding the permission to transform an old caravanserai which had since become an archers' camp back into a caravanserai. During this period, the Assyrians imposed prohibition on selling iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

, which was important for Assyrian armament, to the Arabs to prevent them from developing more efficient weaponry, and instead permitted only copper

Copper is a chemical element; it has symbol Cu (from Latin ) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish-orang ...

to be sold to them. Some Arabs, of unclear relation with both those which were then moving into Babylonia and the Qedarites, were at this time also living in Upper Mesopotamia

Upper Mesopotamia constitutes the Upland and lowland, uplands and great outwash plain of northwestern Iraq, northeastern Syria and southeastern Turkey, in the northern Middle East. Since the early Muslim conquests of the mid-7th century, the regio ...

, where they might have been settled by Sargon II

Sargon II (, meaning "the faithful king" or "the legitimate king") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 722 BC to his death in battle in 705. Probably the son of Tiglath-Pileser III (745–727), Sargon is generally believed to have be ...

and Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

, and where their camels used to graze between Aššur

A≈°≈°ur (; AN.≈ÝAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''A≈°-≈°urKI'', "City of God A≈°≈°ur"; ''ƒÄ≈°≈´r''; ''AŒ∏ur'', ''ƒÄ≈°≈´r''; ', ), also known as Ashur and Qal'at Sherqat, was the capital of the Old Assyrian city-state (2025‚Äì1364 BC), the Mid ...

and ·∏™indanu, under the authority of the governor of Kal·∏´u. Due to inadequate rainfall, the governor of Kal·∏´u lost control of these Upper Mesopotamian Arabs, who in 716 BC engaged in raids in the regions around Su·∏´u and ·∏™indanu and even further south-east till Sippar

Sippar (Sumerian language, Sumerian: , Zimbir) (also Sippir or Sippara) was an ancient Near Eastern Sumerian and later Babylonian city on the east bank of the Euphrates river. Its ''Tell (archaeology), tell'' is located at the site of modern Tell ...

, possibly with the support of Assyrian officials.

The increased importance of Babylonia during this period was reflected by several anti-Assyrian revolts in Babylonia led by Marduk-apla-iddina II

Marduk-apla-iddina II ( Akkadian: ; in the Bible Merodach-Baladan or Berodach-Baladan, lit. ''Marduk has given me an heir'') was a Chaldean leader from the Bit-Yakin tribe, originally established in the territory that once made the Sealand in sou ...

and supported by Elam

Elam () was an ancient civilization centered in the far west and southwest of Iran, stretching from the lowlands of what is now Khuzestan and Ilam Province as well as a small part of modern-day southern Iraq. The modern name ''Elam'' stems fr ...

, and when he recaptured Babylon and revolted against the Assyrians again in 703 BC with the support of the Elamites, the Qedarites supported him, with this policy of theirs being motivated by the trade relations which existed between Qedar and Babylon. One of the Arab supporters of Marduk-apla-iddina II, a chieftain by the name of Bašqanu, was captured by the Assyrian king Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

when he suppressed the Babylonian revolt that same year. This Ba≈°qanu was the brother of an Arab queen named Ya·πØi øe, who appears to have been a Qedarite queen and a successor of ≈Ýam≈°i; the Qedarites had thus adopted the policy of supporting Assyria's enemy once Syria was firmly under Assyrian control after the previous one and half a century of trying to remain on good terms with the powers governing Syria, including Assyria.

During his repression of the Babylonian revolt in 702 BC, Sennacherib also attacked several Arab walled towns surrounded by unwalled villages in Babylonia, although it is unclear what relation existed between these Arabs and the Qedarites despite some of these settlements having names including Arabic components which would later be borne by several Qedarite kings, such as D≈´r-Uait (from Arabic ) and D≈´r-Birdada in Bƒ´t-Amukkani, and D≈´r-Abiyata æ (from Arabic ) in Bit-Dakkuri; among the settlements attacked by Sennacherib was Qidrina, in the territory of Bit-Dakkuri, suggesting that these Babylonian Arabs might have been connected with the Qedarites.

Through a series of campaigns conducted from 703 to 700 BC, Sennacherib was able to establish control over the settled parts of Babylonia, as well as over the nomads of the desert to the immediate west of it, and according to his annals, members of the Tayma

Tayma (; Taymanitic: ê™âê™Éê™í, , vocalized as: ) or Tema is a large oasis with a long history of settlement, located in northwestern Saudi Arabia at the point where the trade route between Medina and Dumah (Sakakah) begins to cross the Na ...

nites and of the Qedarite sub-group of the ≈Ýumu æilu, the latter of whom lived in the eastern Syrian Desert

The Syrian Desert ( ''Bādiyat Ash-Shām''), also known as the North Arabian Desert, the Jordanian steppe, or the Badiya, is a region of desert, semi-desert, and steppe, covering about of West Asia, including parts of northern Saudi Arabia, ea ...

bordering on Babylonia, went to offer him tribute in the late 690s at the Assyrian capital of Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

, where they had to pass through a then recently built gate of the city called the (Desert Gate).

Although Sennacherib had regained control of Babylon in 703 BC, the Babylonians revolted against Assyrian rule with Elamite help yet again in 694 BC, and the Qedarites supported them again. As part of Sennacherib's repression of this new rebellion, which would end with the destruction of the city of Babylon itself in 689 BC, in 691 BC he conducted a campaign against the Qedarites, who by then had grown enough powerful to pose a danger to Assyrian interests. At this time, the Qedarites were ruled by Ya·πØi øe's successor, the priestess-queen Te æel·∏´unu

Te æel·∏´unu (), also spelled Telkhunu, was a queen regnant of the Nomadic Arab tribes of Qedar who ruled in the 7th century BC, circa 690 BC. She succeeded Yatie and was succeeded by queen Tabua.

She was the fourth of six Arab queens to be att ...

and her husband, King ·∏™aza æil

·∏™aza æil () was a Qedarite king regnant who ruled in the 7th century BCE. He was a contemporary of the Neo-Assyrian kings Sennacherib and Esarhaddon. Life

Hazael was a Qedarite king regnant and an associate of the queen of Qedar, Te æel·∏´unu ...

, and who was attacked by the Assyrians while encamped in an oasis in the western borderlands of Babylonia; Te æel·∏´unu, who had come with the nomads to invade the settled areas attacked by the Qedarites, stayed behind in a camp behind the frontlines to remain out of danger should the Qedarite forces be defeated. Te æel·∏´unu and Hazael fled deep into the desert, to the Qedarite capital of D≈´mat, where the Assyrians overtook and captured Te æel·∏´unu and her daughter Tab≈´ øa, and took them as hostages to Assyria along with the idols of the Qedarites' gods, and continued pursuing the Qedarites until Kapanu near the eastern border of the Canaanite kingdom of Ammon, following which Hazael surrendered to Sennacherib and paid him tribute. The rich booty captured by the Assyrians at D≈´mat included camels as well as luxuries which the Qedarite rulers had acquired from the Arabian trade routes, such as spices, precious stones, and gold.

Te æel·∏´unu was taken to the Neo-Assyrian capital of Nineveh

Nineveh ( ; , ''URUNI.NU.A, Ninua''; , ''Nīnəwē''; , ''Nīnawā''; , ''Nīnwē''), was an ancient Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located in the modern-day city of Mosul (itself built out of the Assyrian town of Mepsila) in northern ...

in 689 or 698 BC, where Sennacherib

Sennacherib ( or , meaning "Sin (mythology), Sîn has replaced the brothers") was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 705BC until his assassination in 681BC. The second king of the Sargonid dynasty, Sennacherib is one of the most famous A ...

raised her daughter Tab≈´ øa Tab≈´ øa (Old Arabic: ; ) was a queen regnant of the Nomadic Arab tribes of Qedar. She ruled in the 7th century BC, circa 675 BC. She succeeded queen Te'el-hunu.

Life

Tabua was the fifth of six Arab queens to be attested (as ''sarratu'') in As ...

, following the Assyrian practice of controlling vassal

A vassal or liege subject is a person regarded as having a mutual obligation to a lord or monarch, in the context of the feudal system in medieval Europe. While the subordinate party is called a vassal, the dominant party is called a suzerain ...

populations by raising their rulers at the Assyrian court, while Hazael had retained his position, but as an Assyrian vassal, and he sent Sennacherib continuous tribute until the latter's death. Sennacherib also retained the idols of the Arabian gods as a way to ensure that they would remain loyal to Assyrian power and as a punishment against them in accordance with his heavy-handed policy with respect to Babylonia and its surrounding regions. From this period onwards, the Assyrians would attempt to control the North Arabian populations through vassals, although these vassals would themselves often rebel against the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

When Sennacherib's son Esarhaddon

Esarhaddon, also spelled Essarhaddon, Assarhaddon and Ashurhaddon (, also , meaning " Ashur has given me a brother"; Biblical Hebrew: '' æƒísar-·∏§add≈çn'') was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 681 to 669 BC. The third king of the S ...

succeeded him in 681 BC, Hazael went to Nineveh to request from him that Tab≈´ øa and the idols of the Qedarite gods be returned to him. Esarhaddon, after having had his own name as well as "the might of A≈°≈°ur

A≈°≈°ur (; AN.≈ÝAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: ''A≈°-≈°urKI'', "City of God A≈°≈°ur"; ''ƒÄ≈°≈´r''; ''AŒ∏ur'', ''ƒÄ≈°≈´r''; ', ), also known as Ashur and Qal'at Sherqat, was the capital of the Old Assyrian city-state (2025‚Äì1364 BC), the Mid ...

" inscribed on the idols, acquiesced to Hazael's demand in exchange for an additional tribute of 65 camels, with this light tribute being motivated by Esarhaddon's desire to maintain Hazael's loyalty. This was motivated by Esarhaddon's view that the desert populations were required to maintain control of Babylonia, hence why he adopted the same conciliatory attitude towards the Arabs that he had towards Babylonia itself, and Hazael in consequence ruled over the Qedarites as an Assyrian vassal, and Esarhaddon soon allowed Tab≈´ øa to return to D≈´mat and appointed her as queen of the Qedarites at some point before 678 or 677 BC.

Around the same time, Hazael died and was succeeded as king by his son Yau·πØa ø with the approval of Esarhaddon, who demanded from him a heavier tribute consisting of 10 minas of gold, 1000 gems, 50 camels, and 1000 spice bags. Yau·πØa ø agreed to these conditions due to his dependence on Assyria and to consolidate his precarious position of rulership.

Hazael and his son Yau·πØa ø might have been seen as Assyrian agents by the Qedarites, and, sometime between 676 and 673 BC, one Wahb united the Arab tribes in a revolt against Yau·πØa ø. The Assyrians intervened by suppressing Wahb's rebellion, capturing him and his people, and deporting them to Nineveh to be punished as enemies of the king of Assyria.

When the Assyrians invaded Egypt in 671 BC, Yau·πØa ø was one of the Arab kings summoned by Esarhaddon to provide water supplies to his army during the crossing of the Sinai Desert separating southern Palestine from Egypt. Yau·πØa ø however soon took advantage of Esarhaddon being preoccupied with his operations in Egypt to rebel against Assyria, likely in reaction to the hefty tribute required from him. The Assyrian army intervened against Yau·πØa ø and defeated him, and captured the idols of the Qedarites, including that of their god øAttar-≈Ýamƒì, while Yau·πØa ø himself fled, leaving the Qedarites king-less for the rest of Esarhaddon's rule.

After Esarhaddon died and was succeeded as king of Assyria by his son Ashurbanipal

Ashurbanipal (, meaning " Ashur is the creator of the heir")—or Osnappar ()—was the king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire from 669 BC to his death in 631. He is generally remembered as the last great king of Assyria. Ashurbanipal inherited the th ...

in 669 BC, Yau·πØa ø returned, and requested from the Assyrian king the return of the idol of øAttar-≈Ýamƒì, which Ashurbanipal granted after Yau·πØa ø swore his allegiance to him.

Yau·πØa ø however soon led the Qedarites and the other Arab peoples into rebelling against the Assyrians, although the Nabataean king Nadnu refused when approached by join the revolt by Yau·πØa ø, who, along with the king øAmmu-laddin of another sub-group of Qedarites, attacked the western regions of the Neo-Assyrian Empire in Transjordan and southern Syria, while Yau·πØa ø's wife øA·π≠ƒ´ya, who had come with the nomads to invade the settled areas attacked by the Qedarites, stayed behind in a camp behind the frontlines to remain out of danger should the Qedarite forces be defeated. The Assyrian troops stationed in the region, from ·π¢upite to Edom

Edom (; Edomite language, Edomite: ; , lit.: "red"; Akkadian language, Akkadian: , ; Egyptian language, Ancient Egyptian: ) was an ancient kingdom that stretched across areas in the south of present-day Jordan and Israel. Edom and the Edomi ...

, and the armies of the local Assyrian vassal kings, especially of Moab

Moab () was an ancient Levant, Levantine kingdom whose territory is today located in southern Jordan. The land is mountainous and lies alongside much of the eastern shore of the Dead Sea. The existence of the Kingdom of Moab is attested to by ...

, repelled the Arab attacks, with øAmmu-laddin being defeated and captured by the Moabite king Kamas-halta

Kamas-halta (;

One Abya·πØi ø ben Te æri, who appears to have been unrelated to Yau·πØa ø, became king of the Qedarites with Assyrian approval after going to Nineveh to swear his allegiance to Ashurbanipal and pledge to pay him tribute.

When Esarhaddon's elder son, ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, who had succeeded him as the Neo-Babylonian emperor, rebelled against his brother Ashurbanipal in 652 BC, Abya·πØi ø supported the revolt; this Qedarite policy towards the Assyrians was dictated by their interests in the trade routes in the region, which were threatened by Assyrian encroachment. Abya·πØi ø, along with his brother Ayammu, as well as Yau·πØa ø's cousin, the king Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda of the ≈Ýumu æilu, led a contingent of Arab warriors to Babylon, where they arrived shortly before Ashurbanipal besieged the city. The Qedarite troops were defeated by the Assyrian army and they retreated into Babylon, where they became trapped once the siege had started. Shortly before the Assyrians stormed Babylon and destroyed the city, the Arabs tried to break out of the city, but they were defeated again by the Assyrians.

While the Arab intervention in Babylonia in support of ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin was happening, Yau·πØa ø, who was still a prisoner in Assyria, went to Nineveh to attempt to request Ashurbanipal to restore him as king of the Qedarites. Ashurbanipal however saw Yau·πØa ø as incapable of regaining his leadership over the Qedarites and instead punished him for his previous disloyalty.

Following the complete suppression of the Babylonian revolt in 648 BC, while the Assyrians were busy until 646 BC conducting operations against the Elamite kings who had supported ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, the southern Phoenician cities and the kingdom of Judah seized the opportunity and rebelled against Assyrian authority. Taking advantage of this situation, the Qedarites, led by Abya·πØi ø, Ayammu, and Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda, allied with the Nabataeans led by Nadnu, conducted raids against the western borderlands of the Neo-Assyrian Empire ranging from the Jabal al-Bi≈°rƒ´ to the environs of the city of

One Abya·πØi ø ben Te æri, who appears to have been unrelated to Yau·πØa ø, became king of the Qedarites with Assyrian approval after going to Nineveh to swear his allegiance to Ashurbanipal and pledge to pay him tribute.

When Esarhaddon's elder son, ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, who had succeeded him as the Neo-Babylonian emperor, rebelled against his brother Ashurbanipal in 652 BC, Abya·πØi ø supported the revolt; this Qedarite policy towards the Assyrians was dictated by their interests in the trade routes in the region, which were threatened by Assyrian encroachment. Abya·πØi ø, along with his brother Ayammu, as well as Yau·πØa ø's cousin, the king Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda of the ≈Ýumu æilu, led a contingent of Arab warriors to Babylon, where they arrived shortly before Ashurbanipal besieged the city. The Qedarite troops were defeated by the Assyrian army and they retreated into Babylon, where they became trapped once the siege had started. Shortly before the Assyrians stormed Babylon and destroyed the city, the Arabs tried to break out of the city, but they were defeated again by the Assyrians.

While the Arab intervention in Babylonia in support of ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin was happening, Yau·πØa ø, who was still a prisoner in Assyria, went to Nineveh to attempt to request Ashurbanipal to restore him as king of the Qedarites. Ashurbanipal however saw Yau·πØa ø as incapable of regaining his leadership over the Qedarites and instead punished him for his previous disloyalty.

Following the complete suppression of the Babylonian revolt in 648 BC, while the Assyrians were busy until 646 BC conducting operations against the Elamite kings who had supported ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, the southern Phoenician cities and the kingdom of Judah seized the opportunity and rebelled against Assyrian authority. Taking advantage of this situation, the Qedarites, led by Abya·πØi ø, Ayammu, and Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda, allied with the Nabataeans led by Nadnu, conducted raids against the western borderlands of the Neo-Assyrian Empire ranging from the Jabal al-Bi≈°rƒ´ to the environs of the city of

After Ashurbanipal's death, the Babylonians led by

After Ashurbanipal's death, the Babylonians led by  From Judah, King

From Judah, King

"Gešem the Arabian" an adversary of

"Gešem the Arabian" an adversary of

The ancient Greek historian

The ancient Greek historian

Nabataeans

The Nabataeans or Nabateans (; Nabataean Aramaic: , , vocalized as ) were an ancient Arabs, Arab people who inhabited northern Arabian Peninsula, Arabia and the southern Levant. Their settlements—most prominently the assumed capital city o ...

, whose king Nadnu refused to grant him asylum and instead swore allegiance to the Assyrians and handed over Yau·πØa ø to Ashurbanipal, who punished Yau·πØa ø by imprisoning him in a cage.

One Abya·πØi ø ben Te æri, who appears to have been unrelated to Yau·πØa ø, became king of the Qedarites with Assyrian approval after going to Nineveh to swear his allegiance to Ashurbanipal and pledge to pay him tribute.

When Esarhaddon's elder son, ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, who had succeeded him as the Neo-Babylonian emperor, rebelled against his brother Ashurbanipal in 652 BC, Abya·πØi ø supported the revolt; this Qedarite policy towards the Assyrians was dictated by their interests in the trade routes in the region, which were threatened by Assyrian encroachment. Abya·πØi ø, along with his brother Ayammu, as well as Yau·πØa ø's cousin, the king Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda of the ≈Ýumu æilu, led a contingent of Arab warriors to Babylon, where they arrived shortly before Ashurbanipal besieged the city. The Qedarite troops were defeated by the Assyrian army and they retreated into Babylon, where they became trapped once the siege had started. Shortly before the Assyrians stormed Babylon and destroyed the city, the Arabs tried to break out of the city, but they were defeated again by the Assyrians.

While the Arab intervention in Babylonia in support of ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin was happening, Yau·πØa ø, who was still a prisoner in Assyria, went to Nineveh to attempt to request Ashurbanipal to restore him as king of the Qedarites. Ashurbanipal however saw Yau·πØa ø as incapable of regaining his leadership over the Qedarites and instead punished him for his previous disloyalty.

Following the complete suppression of the Babylonian revolt in 648 BC, while the Assyrians were busy until 646 BC conducting operations against the Elamite kings who had supported ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, the southern Phoenician cities and the kingdom of Judah seized the opportunity and rebelled against Assyrian authority. Taking advantage of this situation, the Qedarites, led by Abya·πØi ø, Ayammu, and Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda, allied with the Nabataeans led by Nadnu, conducted raids against the western borderlands of the Neo-Assyrian Empire ranging from the Jabal al-Bi≈°rƒ´ to the environs of the city of

One Abya·πØi ø ben Te æri, who appears to have been unrelated to Yau·πØa ø, became king of the Qedarites with Assyrian approval after going to Nineveh to swear his allegiance to Ashurbanipal and pledge to pay him tribute.

When Esarhaddon's elder son, ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, who had succeeded him as the Neo-Babylonian emperor, rebelled against his brother Ashurbanipal in 652 BC, Abya·πØi ø supported the revolt; this Qedarite policy towards the Assyrians was dictated by their interests in the trade routes in the region, which were threatened by Assyrian encroachment. Abya·πØi ø, along with his brother Ayammu, as well as Yau·πØa ø's cousin, the king Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda of the ≈Ýumu æilu, led a contingent of Arab warriors to Babylon, where they arrived shortly before Ashurbanipal besieged the city. The Qedarite troops were defeated by the Assyrian army and they retreated into Babylon, where they became trapped once the siege had started. Shortly before the Assyrians stormed Babylon and destroyed the city, the Arabs tried to break out of the city, but they were defeated again by the Assyrians.

While the Arab intervention in Babylonia in support of ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin was happening, Yau·πØa ø, who was still a prisoner in Assyria, went to Nineveh to attempt to request Ashurbanipal to restore him as king of the Qedarites. Ashurbanipal however saw Yau·πØa ø as incapable of regaining his leadership over the Qedarites and instead punished him for his previous disloyalty.

Following the complete suppression of the Babylonian revolt in 648 BC, while the Assyrians were busy until 646 BC conducting operations against the Elamite kings who had supported ≈Ýama≈°-≈°uma-ukin, the southern Phoenician cities and the kingdom of Judah seized the opportunity and rebelled against Assyrian authority. Taking advantage of this situation, the Qedarites, led by Abya·πØi ø, Ayammu, and Yuwai·πØi ø ben BirdƒÅda, allied with the Nabataeans led by Nadnu, conducted raids against the western borderlands of the Neo-Assyrian Empire ranging from the Jabal al-Bi≈°rƒ´ to the environs of the city of Damascus