Pseudomonas Pyocyanea on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common encapsulated,

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common encapsulated,

The word ''Pseudomonas'' means "false unit", from the Greek ''pseudēs'' (

The word ''Pseudomonas'' means "false unit", from the Greek ''pseudēs'' (

A comparative genomic study (in 2020) analyzed 494 complete genomes from the ''Pseudomonas'' genus, of which 189 were ''P. aeruginosa'' strains. The study observed that their protein count and

A comparative genomic study (in 2020) analyzed 494 complete genomes from the ''Pseudomonas'' genus, of which 189 were ''P. aeruginosa'' strains. The study observed that their protein count and

Frequently acting as an

Frequently acting as an

Depending on the nature of infection, an appropriate specimen is collected and sent to a

Depending on the nature of infection, an appropriate specimen is collected and sent to a

Due to widespread resistance to many common first-line antibiotics,

Due to widespread resistance to many common first-line antibiotics,

One of the most worrisome characteristics of ''P. aeruginosa'' is its low antibiotic susceptibility, which is attributable to a concerted action of multidrug efflux pumps with chromosomally encoded antibiotic resistance genes, i.e., the genes that encode proteins that serve as

One of the most worrisome characteristics of ''P. aeruginosa'' is its low antibiotic susceptibility, which is attributable to a concerted action of multidrug efflux pumps with chromosomally encoded antibiotic resistance genes, i.e., the genes that encode proteins that serve as

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common encapsulated,

''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' is a common encapsulated, Gram-negative

Gram-negative bacteria are bacteria that, unlike gram-positive bacteria, do not retain the crystal violet stain used in the Gram staining method of bacterial differentiation. Their defining characteristic is that their cell envelope consists ...

, aerobic

Aerobic means "requiring air," in which "air" usually means oxygen.

Aerobic may also refer to

* Aerobic exercise, prolonged exercise of moderate intensity

* Aerobics, a form of aerobic exercise

* Aerobic respiration, the aerobic process of cellu ...

–facultatively anaerobic

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

, rod-shaped

Bacterial cellular morphologies are the shapes that are characteristic of various types of bacteria and often key to their identification. Their direct examination under a light microscope enables the classification of these bacteria (and archae ...

bacterium

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one biological cell. They constitute a large domain of prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micrometres in length, bacteria were among the ...

that can cause disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

in plants and animals, including humans. A species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of considerable medical importance, ''P. aeruginosa'' is a multidrug resistant pathogen recognized for its ubiquity, its intrinsically advanced antibiotic resistance

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR or AR) occurs when microbes evolve mechanisms that protect them from antimicrobials, which are drugs used to treat infections. This resistance affects all classes of microbes, including bacteria (antibiotic resis ...

mechanisms, and its association with serious illnesses – hospital-acquired infections

A hospital-acquired infection, also known as a nosocomial infection (from the Greek , meaning "hospital"), is an infection that is acquired in a hospital or other healthcare facility. To emphasize both hospital and nonhospital settings, it is s ...

such as ventilator-associated pneumonia

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a type of lung infection that occurs in people who are on mechanical ventilation breathing machines in hospitals. As such, VAP typically affects critically ill persons that are in an intensive care unit (I ...

and various sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

syndromes

A syndrome is a set of medical signs and symptoms which are correlated with each other and often associated with a particular disease or disorder. The word derives from the Greek σύνδρομον, meaning "concurrence". When a syndrome is paire ...

. ''P. aeruginosa'' is able to selectively inhibit various antibiotics from penetrating its outer membrane'' ''– and has high resistance to several antibiotics. According to the World Health Organization

The World Health Organization (WHO) is a list of specialized agencies of the United Nations, specialized agency of the United Nations which coordinates responses to international public health issues and emergencies. It is headquartered in Gen ...

''P. aeruginosa'' poses one of the greatest threats to humans in terms of antibiotic resistance.

The organism is considered opportunistic

300px, ''Opportunity Seized, Opportunity Missed'', engraving by Theodoor Galle, 1605

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances — with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opport ...

insofar as serious infection often occurs during existing disease

A disease is a particular abnormal condition that adversely affects the structure or function (biology), function of all or part of an organism and is not immediately due to any external injury. Diseases are often known to be medical condi ...

s or conditions'' ''– most notably cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

and traumatic burns. It generally affects the immunocompromised

Immunodeficiency, also known as immunocompromise, is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious diseases and cancer is compromised or entirely absent. Most cases are acquired ("secondary") due to extrinsic factors that affe ...

but can also infect the immunocompetent

In immunology, immunocompetence is the ability of the body to produce a normal immune response following exposure to an antigen. Immunocompetence is the opposite of immunodeficiency (also known as ''immuno-incompetence'' or being ''immuno-comprom ...

as in hot tub folliculitis

Hot tub folliculitis, also called ''Pseudomonal'' folliculitis or Pseudomonas aeruginosa folliculitis, is a common type of folliculitis featuring inflammation of hair follicles and surrounding skin.

This condition is caused by an infection of the ...

. Treatment of ''P. aeruginosa'' infections can be difficult due to its natural resistance to antibiotics. When more advanced antibiotic drug regimens are needed adverse effects

An adverse effect is an undesired harmful effect resulting from a medication or other intervention, such as surgery. An adverse effect may be termed a "side effect", when judged to be secondary to a main or therapeutic effect. The term complic ...

may result.

It is citrate

Citric acid is an organic compound with the formula . It is a colorless weak organic acid. It occurs naturally in citrus fruits. In biochemistry

Biochemistry, or biological chemistry, is the study of chemical processes within and relati ...

, catalase

Catalase is a common enzyme found in nearly all living organisms exposed to oxygen (such as bacteria, plants, and animals) which catalyzes the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide to water and oxygen. It is a very important enzyme in protecting ...

, and oxidase positive

The oxidase test is used to determine whether an organism possesses the cytochrome c oxidase enzyme. The test is used as an aid for the differentiation of '' Neisseria'', '' Moraxella'', '' Campylobacter'' and '' Pasteurella'' species (oxidase posi ...

. It is found in soil, water, skin flora

Skin flora, also called skin microbiota, refers to microbiota (community (ecology), communities of microorganisms) that reside on the skin, typically human skin.

Many of them are bacterium, bacteria of which there are around 1,000 species upon hu ...

, and most human-made environments throughout the world. As a facultative anaerobe

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

, ''P. aeruginosa'' thrives in diverse habitats. It uses a wide range of organic material for food; in animals, its versatility enables the organism to infect damaged tissues or those with reduced immunity. The symptoms of such infections are generalized inflammation

Inflammation (from ) is part of the biological response of body tissues to harmful stimuli, such as pathogens, damaged cells, or irritants. The five cardinal signs are heat, pain, redness, swelling, and loss of function (Latin ''calor'', '' ...

and sepsis

Sepsis is a potentially life-threatening condition that arises when the body's response to infection causes injury to its own tissues and organs.

This initial stage of sepsis is followed by suppression of the immune system. Common signs and s ...

. If such colonizations occur in critical body organs, such as the lung

The lungs are the primary Organ (biology), organs of the respiratory system in many animals, including humans. In mammals and most other tetrapods, two lungs are located near the Vertebral column, backbone on either side of the heart. Their ...

s, the urinary tract

The human urinary system, also known as the urinary tract or renal system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and the urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressu ...

, and kidney

In humans, the kidneys are two reddish-brown bean-shaped blood-filtering organ (anatomy), organs that are a multilobar, multipapillary form of mammalian kidneys, usually without signs of external lobulation. They are located on the left and rig ...

s, the results can be fatal.

Because it thrives on moist surfaces, this bacterium is also found on and in soap and medical equipment

A medical device is any device intended to be used for medical purposes. Significant potential for hazards are inherent when using a device for medical purposes and thus medical devices must be proved safe and effective with reasonable assura ...

, including catheter

In medicine, a catheter ( ) is a thin tubing (material), tube made from medical grade materials serving a broad range of functions. Catheters are medical devices that can be inserted in the body to treat diseases or perform a surgical procedure. ...

s, causing cross-infection

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

s in hospital

A hospital is a healthcare institution providing patient treatment with specialized Medical Science, health science and auxiliary healthcare staff and medical equipment. The best-known type of hospital is the general hospital, which typically ...

s and clinic

A clinic (or outpatient clinic or ambulatory care clinic) is a health facility that is primarily focused on the care of outpatients. Clinics can be privately operated or publicly managed and funded. They typically cover the primary care needs ...

s. It is also able to decompose hydrocarbons and has been used to break down tarballs and oil from oil spill

An oil spill is the release of a liquid petroleum hydrocarbon into the environment, especially the marine ecosystem, due to human activity, and is a form of pollution. The term is usually given to marine oil spills, where oil is released into th ...

s. ''P. aeruginosa'' is not extremely virulent

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most cases, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its abilit ...

in comparison with other major species of pathogenic bacteria

Pathogenic bacteria are bacteria that can cause disease. This article focuses on the bacteria that are pathogenic to humans. Most species of bacteria are harmless and many are Probiotic, beneficial but others can cause infectious diseases. The nu ...

such as Gram-positive

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria are bacteria that give a positive result in the Gram stain test, which is traditionally used to quickly classify bacteria into two broad categories according to their type of cell wall.

The Gram stain is ...

''Staphylococcus aureus

''Staphylococcus aureus'' is a Gram-positive spherically shaped bacterium, a member of the Bacillota, and is a usual member of the microbiota of the body, frequently found in the upper respiratory tract and on the skin. It is often posi ...

'' and ''Streptococcus pyogenes

''Streptococcus pyogenes'' is a species of Gram-positive, aerotolerant bacteria in the genus '' Streptococcus''. These bacteria are extracellular, and made up of non-motile and non-sporing cocci (round cells) that tend to link in chains. They ...

''– though ''P. aeruginosa'' is capable of extensive colonization, and can aggregate into enduring biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s. Its genome includes numerous genes for transcriptional regulation and antibiotic resistance, such as efflux systems and beta-lactamases, which contribute to its adaptability and pathogenicity in human hosts. ''P. aeruginosa'' produces a characteristic sweet, grape-like odor due to its synthesis of 2-aminoacetophenone.

Nomenclature

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: ψευδής, false) and (, from Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

: μονάς, a single unit). The stem word ''mon'' was used early in the history of microbiology

Microbiology () is the branches of science, scientific study of microorganisms, those being of unicellular organism, unicellular (single-celled), multicellular organism, multicellular (consisting of complex cells), or non-cellular life, acellula ...

to refer to microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s and germ

Germ or germs may refer to:

Science

* Germ (microorganism), an informal word for a pathogen

* Germ cell, cell that gives rise to the gametes of an organism that reproduces sexually

* Germ layer, a primary layer of cells that forms during embry ...

s, e.g., kingdom Monera

Monera () (Greek: (), "single", "solitary") is historically a biological kingdom that is made up of unicellular prokaryotes. As such, it is composed of single-celled organisms that lack a nucleus.

The taxon Monera was first proposed as a ...

.

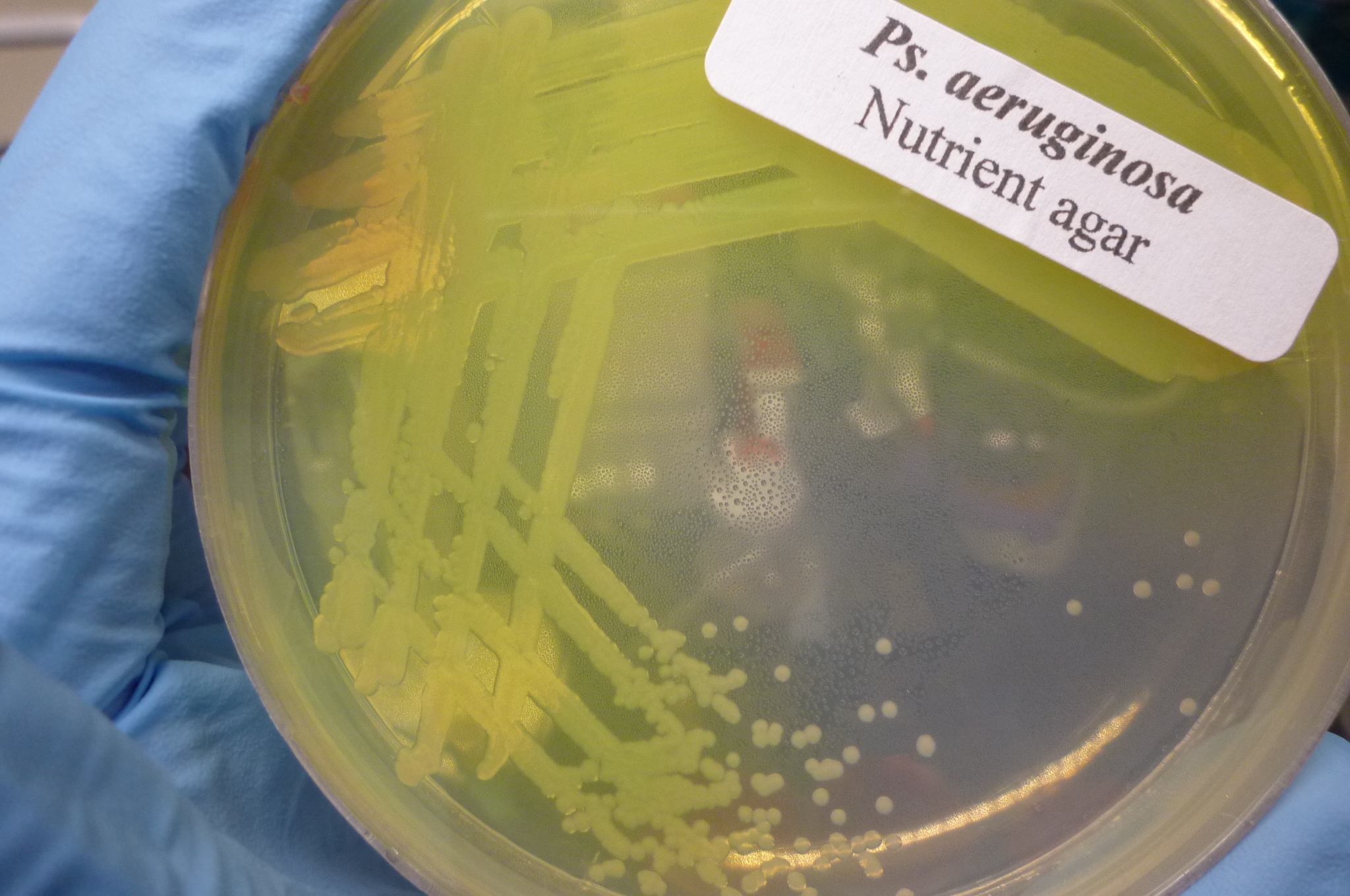

The species name ''aeruginosa'' is a Latin word meaning verdigris

Verdigris () is a common name for any of a variety of somewhat toxic copper salt (chemistry), salts of acetic acid, which range in colour from green to a blue-green, bluish-green depending on their chemical composition.H. Kühn, Verdigris and Cop ...

("copper rust"), referring to the blue-green color of laboratory cultures of the species. This blue-green pigment is a combination of two secondary metabolite

Secondary metabolites, also called ''specialised metabolites'', ''secondary products'', or ''natural products'', are organic compounds produced by any lifeform, e.g. bacteria, archaea, fungi, animals, or plants, which are not directly involved ...

s of ''P. aeruginosa'', pyocyanin

Pyocyanin (PCN−) is one of the many toxic compounds produced and secreted by the Gram negative bacterium ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa''. Pyocyanin is a blue secondary metabolite, turning red below pH 4.9, with the ability to oxidise and reduce other ...

(blue) and pyoverdine

Pyoverdines (alternatively, and less commonly, spelled as pyoverdins) are fluorescent siderophores produced by certain pseudomonads. Pyoverdines are important virulence factors, and are required for pathogenesis in many biological models of infec ...

(green), which impart the blue-green characteristic color of cultures. Another assertion from 1956 is that ''aeruginosa'' may be derived from the Greek prefix ''ae-'' meaning "old or aged", and the suffix ''ruginosa'' means wrinkled or bumpy.

The names pyocyanin and pyoverdine are from the Greek, with ''pyo-'', meaning "pus", ''cyanin'', meaning "blue", and ''verdine'', meaning "green". Hence, the term "pyocyanic bacteria" refers specifically to the "blue pus" characteristic of a ''P. aeruginosa'' infection. Pyoverdine in the absence of pyocyanin is a fluorescent-yellow color.

Biology

Genome

Thegenome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

of ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' consists of a relatively large circular chromosome (5.5–6.8'' ''Mb) that carries between 5,500 and 6,000 open reading frame

In molecular biology, reading frames are defined as spans of DNA sequence between the start and stop codons. Usually, this is considered within a studied region of a prokaryotic DNA sequence, where only one of the six possible reading frames ...

s, and sometimes plasmid

A plasmid is a small, extrachromosomal DNA molecule within a cell that is physically separated from chromosomal DNA and can replicate independently. They are most commonly found as small circular, double-stranded DNA molecules in bacteria and ...

s of various sizes depending on the strain. Comparison of 389 genomes from different ''P. aeruginosa'' strains showed that just 17.5% is shared. This part of the genome is the ''P. aeruginosa'' core genome.

A comparative genomic study (in 2020) analyzed 494 complete genomes from the ''Pseudomonas'' genus, of which 189 were ''P. aeruginosa'' strains. The study observed that their protein count and

A comparative genomic study (in 2020) analyzed 494 complete genomes from the ''Pseudomonas'' genus, of which 189 were ''P. aeruginosa'' strains. The study observed that their protein count and GC content

In molecular biology and genetics, GC-content (or guanine-cytosine content) is the percentage of nitrogenous bases in a DNA or RNA molecule that are either guanine (G) or cytosine (C). This measure indicates the proportion of G and C bases out of ...

ranged between 5500 and 7352 (average: 6192) and between 65.6 and 66.9% (average: 66.1%), respectively. This comparative analysis further identified 1811 aeruginosa-core proteins, which accounts for more than 30% of the proteome. The higher percentage of aeruginosa-core proteins in this latter analysis could partly be attributed to the use of complete genomes. Although ''P. aeruginosa'' is a very well-defined monophyletic species, phylogenomically and in terms of ANIm values, it is surprisingly diverse in terms of protein content, thus revealing a very dynamic accessory proteome, in accordance with several analyses. It appears that, on average, industrial strains have the largest genomes, followed by environmental strains, and then clinical isolates. The same comparative study (494 ''Pseudomonas'' strains, of which 189 are ''P. aeruginosa'') identified that 41 of the 1811 ''P. aeruginosa'' core proteins were present only in this species and not in any other member of the genus, with 26 (of the 41) being annotated as hypothetical. Furthermore, another 19 orthologous protein groups are present in at least 188/189 ''P. aeruginosa'' strains and absent in all the other strains of the genus.

Population structure

The population of ''P. aeruginosa'' can be classified in three main lineages, genetically characterised by the model strains PAO1, PA14, and the more divergent PA7. While ''P. aeruginosa'' is generally thought of as an opportunistic pathogen, several widespread clones appear to have become more specialised pathogens, particularly incystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

patients, including the Liverpool epidemic strain (LES) which is found mainly in the UK, DK2 in Denmark, and AUST-02 in Australia (also previously known as AES-2 and P2). There is also a clone that is frequently found infecting the reproductive tracts of horses.

Metabolism

''P. aeruginosa'' is afacultative anaerobe

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

, as it is well adapted to proliferate in conditions of partial or total oxygen depletion. This organism can achieve anaerobic

Anaerobic means "living, active, occurring, or existing in the absence of free oxygen", as opposed to aerobic which means "living, active, or occurring only in the presence of oxygen." Anaerobic may also refer to:

*Adhesive#Anaerobic, Anaerobic ad ...

growth with nitrate

Nitrate is a polyatomic ion with the chemical formula . salt (chemistry), Salts containing this ion are called nitrates. Nitrates are common components of fertilizers and explosives. Almost all inorganic nitrates are solubility, soluble in wa ...

or nitrite

The nitrite polyatomic ion, ion has the chemical formula . Nitrite (mostly sodium nitrite) is widely used throughout chemical and pharmaceutical industries. The nitrite anion is a pervasive intermediate in the nitrogen cycle in nature. The name ...

as a terminal electron acceptor

An electron acceptor is a chemical entity that accepts electrons transferred to it from another compound. Electron acceptors are oxidizing agents.

The electron accepting power of an electron acceptor is measured by its redox potential.

In the si ...

. When oxygen, nitrate, and nitrite are absent, it is able to ferment arginine

Arginine is the amino acid with the formula (H2N)(HN)CN(H)(CH2)3CH(NH2)CO2H. The molecule features a guanidinium, guanidino group appended to a standard amino acid framework. At physiological pH, the carboxylic acid is deprotonated (−CO2−) a ...

and pyruvate

Pyruvic acid (CH3COCOOH) is the simplest of the alpha-keto acids, with a carboxylic acid and a ketone functional group. Pyruvate, the conjugate base, CH3COCOO−, is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways throughout the cell.

Pyruvic ...

by substrate-level phosphorylation

Substrate-level phosphorylation is a metabolism reaction that results in the production of ATP or GTP supported by the energy released from another high-energy bond that leads to phosphorylation of ADP or GDP to ATP or GTP (note that the rea ...

. Additionally, phenazines produced by ''P. aeruginosa'' can act as electron shuttles to facilitate survival of cells at depth in biofilms. Adaptation to microaerobic

A microaerophile is a microorganism that requires environments containing lower levels of dioxygen than that are present in the atmosphere (i.e. < 21% O2; typically 2–10% O2) for optimal growth. A more r ...

or anaerobic environments is essential for certain lifestyles of ''P. aeruginosa'', for example, during lung infection in cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

and primary ciliary dyskinesia

Primary ciliary dyskinesia (PCD) is a rare, autosomal recessive genetic ciliopathy, that causes defects in the action of cilia lining the upper and lower respiratory tract, sinuses, Eustachian tube, middle ear, fallopian tube, and flagella of spe ...

, where thick layers of lung mucus

Mucus (, ) is a slippery aqueous secretion produced by, and covering, mucous membranes. It is typically produced from cells found in mucous glands, although it may also originate from mixed glands, which contain both Serous fluid, serous and muc ...

and bacterially-produced alginate

Alginic acid, also called algin, is a naturally occurring, edible polysaccharide found in brown algae. It is hydrophilic and forms a viscous gum when hydrated. When the alginic acid binds with sodium and calcium ions, the resulting salts are k ...

surrounding mucoid bacterial cells can limit the diffusion of oxygen. ''P. aeruginosa'' growth within the human body can be asymptomatic until the bacteria form a biofilm, which overwhelms the immune system. These biofilms are found in the lungs of people with cystic fibrosis and primary ciliary dyskinesia, and can prove fatal.

Cellular co-operation

''P. aeruginosa'' relies oniron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

as a nutrient source to grow. However, iron is not easily accessible because it is not commonly found in the environment. Iron is usually found in a largely insoluble ferric form. Furthermore, excessively high levels of iron can be toxic to ''P. aeruginosa''. To overcome this and regulate proper intake of iron, ''P. aeruginosa'' uses siderophore

Siderophores (Greek: "iron carrier") are small, high-affinity iron- chelating compounds that are secreted by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. They help the organism accumulate iron. Although a widening range of siderophore functions is n ...

s, which are secreted molecules that bind and transport iron. These iron-siderophore complexes, however, are not specific. The bacterium that produced the siderophores does not necessarily receive the direct benefit of iron intake. Rather, all members of the cellular population are equally likely to access the iron-siderophore complexes. Members of the cellular population that can efficiently produce these siderophores are commonly referred to as cooperators; members that produce little to no siderophores are often referred to as cheaters. Research has shown when cooperators and cheaters are grown together, cooperators have a decrease in fitness, while cheaters have an increase in fitness. The magnitude of change in fitness increases with increasing iron limitation. With an increase in fitness, the cheaters can outcompete the cooperators; this leads to an overall decrease in fitness of the group, due to lack of sufficient siderophore production. These observations suggest that having a mix of cooperators and cheaters can reduce the virulent nature of ''P. aeruginosa''.

Enzymes

LigD

LigD is a multifunctional ligase/polymerase/nuclease ( 3'-phosphoesterase) found in bacterial non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) DNA repair systems. It is much more error-prone than the more complex eukaryotic system of NHEJ, which uses multiple enz ...

s form a subfamily of the DNA ligase

DNA ligase is a type of enzyme that facilitates the joining of DNA strands together by catalyzing the formation of a phosphodiester bond. It plays a role in repairing single-strand breaks in duplex DNA in living organisms, but some forms (such ...

s. These all have a LigDom/ligase domain, but many bacterial LigDs also have separate polymerase

In biochemistry, a polymerase is an enzyme (Enzyme Commission number, EC 2.7.7.6/7/19/48/49) that synthesizes long chains of polymers or nucleic acids. DNA polymerase and RNA polymerase are used to assemble DNA and RNA molecules, respectively, by ...

domains/PolDoms and nuclease

In biochemistry, a nuclease (also archaically known as nucleodepolymerase or polynucleotidase) is an enzyme capable of cleaving the phosphodiester bonds that link nucleotides together to form nucleic acids. Nucleases variously affect single and ...

domains/NucDoms. In ''P. aeruginosa''s case the nuclease domains are N-terminus

The N-terminus (also known as the amino-terminus, NH2-terminus, N-terminal end or amine-terminus) is the start of a protein or polypeptide, referring to the free amine group (-NH2) located at the end of a polypeptide. Within a peptide, the amin ...

, and the polymerase domains are C-terminus

The C-terminus (also known as the carboxyl-terminus, carboxy-terminus, C-terminal tail, carboxy tail, C-terminal end, or COOH-terminus) is the end of an amino acid chain (protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comp ...

, extensions of the single central ligase domain.

Pathogenesis

opportunistic

300px, ''Opportunity Seized, Opportunity Missed'', engraving by Theodoor Galle, 1605

Opportunism is the practice of taking advantage of circumstances — with little regard for principles or with what the consequences are for others. Opport ...

, nosocomial

A hospital-acquired infection, also known as a nosocomial infection (from the Greek , meaning "hospital"), is an infection that is acquired in a hospital or other healthcare facility. To emphasize both hospital and nonhospital settings, it is s ...

pathogen of immunocompromised

Immunodeficiency, also known as immunocompromise, is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious diseases and cancer is compromised or entirely absent. Most cases are acquired ("secondary") due to extrinsic factors that affe ...

individuals, but capable of infecting the immunocompetent, ''P. aeruginosa'' typically infects the airway, urinary tract

The human urinary system, also known as the urinary tract or renal system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and the urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and blood pressu ...

, burns

Burns may refer to:

Astronomy

* 2708 Burns, an asteroid

* Burns (crater), on Mercury

People

* Burns (surname), list of people and characters named Burns

** Burns (musician), Scottish record producer

Places in the United States

* Burns, ...

, and wound

A wound is any disruption of or damage to living tissue, such as skin, mucous membranes, or organs. Wounds can either be the sudden result of direct trauma (mechanical, thermal, chemical), or can develop slowly over time due to underlying diseas ...

s, and also causes other blood infections.

It is the most common cause of infections of burn injuries and of the outer ear

The outer ear, external ear, or auris externa is the external part of the ear, which consists of the auricle (also pinna) and the ear canal. It gathers sound energy and focuses it on the eardrum ( tympanic membrane).

Structure

Auricle

The ...

(otitis externa

Otitis externa, also called swimmer's ear, is inflammation of the ear canal. It often presents with ear pain, swelling of the ear canal, and occasionally decreased hearing. Typically there is pain with movement of the outer ear. A high fever ...

), and is the most frequent colonizer of medical devices (e.g., catheter

In medicine, a catheter ( ) is a thin tubing (material), tube made from medical grade materials serving a broad range of functions. Catheters are medical devices that can be inserted in the body to treat diseases or perform a surgical procedure. ...

s). ''Pseudomonas'' can be spread by equipment that gets contaminated and is not properly cleaned or on the hands of healthcare workers. ''Pseudomonas'' can, in rare circumstances, cause community-acquired pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia contracted by a person outside of the healthcare system. In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is seen in patients who are in a hospital or who have recently been hospitalized in the ...

s, as well as ventilator

A ventilator is a type of breathing apparatus, a class of medical technology that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathi ...

-associated pneumonias, being one of the most common agents isolated in several studies. Pyocyanin

Pyocyanin (PCN−) is one of the many toxic compounds produced and secreted by the Gram negative bacterium ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa''. Pyocyanin is a blue secondary metabolite, turning red below pH 4.9, with the ability to oxidise and reduce other ...

is a virulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

of the bacteria and has been known to cause death in '' C. elegans'' by oxidative stress

Oxidative stress reflects an imbalance between the systemic manifestation of reactive oxygen species and a biological system's ability to readily detoxify the reactive intermediates or to repair the resulting damage. Disturbances in the normal ...

. However, salicylic acid

Salicylic acid is an organic compound with the formula HOC6H4COOH. A colorless (or white), bitter-tasting solid, it is a precursor to and a active metabolite, metabolite of acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin). It is a plant hormone, and has been lis ...

can inhibit pyocyanin production. One in ten hospital-acquired infections is from ''Pseudomonas'' . Cystic fibrosis

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is a genetic disorder inherited in an autosomal recessive manner that impairs the normal clearance of Sputum, mucus from the lungs, which facilitates the colonization and infection of the lungs by bacteria, notably ''Staphy ...

patients are also predisposed to ''P. aeruginosa'' infection of the lungs due to a functional loss in chloride ion movement across cell membranes as a result of a mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

. ''P. aeruginosa'' may also be a common cause of "hot-tub rash" (dermatitis

Dermatitis is a term used for different types of skin inflammation, typically characterized by itchiness, redness and a rash. In cases of short duration, there may be small blisters, while in long-term cases the skin may become thickened ...

), caused by lack of proper, periodic attention to water quality. Since these bacteria thrive in moist environments, such as hot tubs and swimming pools, they can cause skin rash or swimmer's ear. ''Pseudomonas'' is also a common cause of postoperative infection in radial keratotomy

Radial keratotomy (RK) is a refractive surgery, refractive surgical procedure to correct myopia (nearsightedness). It was developed in 1974 by Svyatoslav Fyodorov, a Russian Ophthalmology, ophthalmologist. It has been largely supplanted by newer, ...

surgery patients. The organism is also associated with the skin lesion ecthyma gangrenosum. ''P. aeruginosa'' is frequently associated with osteomyelitis

Osteomyelitis (OM) is the infectious inflammation of bone marrow. Symptoms may include pain in a specific bone with overlying redness, fever, and weakness. The feet, spine, and hips are the most commonly involved bones in adults.

The cause is ...

involving puncture wounds of the foot, believed to result from direct inoculation with ''P. aeruginosa'' via the foam padding found in tennis shoes, with diabetic patients at a higher risk.

A comparative genomic analysis of 494 complete ''Pseudomonas'' genomes, including 189 complete ''P. aeruginosa'' genomes, identified several proteins that are shared by the vast majority of ''P. aeruginosa'' strains, but are not observed in other analyzed ''Pseudomonas'' genomes. These aeruginosa-specific core proteins, such as ''CntL, CntM, PlcB, Acp1, MucE, SrfA, Tse1, Tsi2, Tse3,'' and ''EsrC'' are known to play an important role in this species' pathogenicity.

Toxins

''P. aeruginosa'' uses thevirulence factor

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* c ...

exotoxin A

The Pseudomonas exotoxin (or exotoxin A) is an exotoxin produced by ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa''. ''Vibrio cholerae'' produces a similar protein called the Cholix toxin ().

It inhibits elongation factor-2. It does so by ADP-ribosylation of EF2 u ...

to inactivate eukaryotic elongation factor 2 via ADP-ribosylation

ADP-ribosylation is the addition of one or more ADP-ribose moieties to a protein. It is a reversible post-translational modification that is involved in many cellular processes, including cell signaling, DNA repair, gene regulation and apoptosis ...

in the host cell, much as the diphtheria toxin

Diphtheria toxin is an exotoxin secreted mainly by '' Corynebacterium diphtheriae'' but also by ''Corynebacterium ulcerans'' and '' Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis'', the pathogenic bacterium that causes diphtheria. The toxin gene is enco ...

does. Without elongation factor'' ''2, eukaryotic cells

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of li ...

cannot synthesize proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, re ...

and necrotise. The release of intracellular contents induces an immunologic response in immunocompetent

In immunology, immunocompetence is the ability of the body to produce a normal immune response following exposure to an antigen. Immunocompetence is the opposite of immunodeficiency (also known as ''immuno-incompetence'' or being ''immuno-comprom ...

patients.

In addition ''P. aeruginosa'' uses an exoenzyme, ExoU, which degrades the plasma membrane of eukaryotic cells, leading to lysis

Lysis ( ; from Greek 'loosening') is the breaking down of the membrane of a cell, often by viral, enzymic, or osmotic (that is, "lytic" ) mechanisms that compromise its integrity. A fluid containing the contents of lysed cells is called a ...

. Increasingly, it is becoming recognized that the iron-acquiring siderophore

Siderophores (Greek: "iron carrier") are small, high-affinity iron- chelating compounds that are secreted by microorganisms such as bacteria and fungi. They help the organism accumulate iron. Although a widening range of siderophore functions is n ...

, pyoverdine

Pyoverdines (alternatively, and less commonly, spelled as pyoverdins) are fluorescent siderophores produced by certain pseudomonads. Pyoverdines are important virulence factors, and are required for pathogenesis in many biological models of infec ...

, also functions as a toxin by removing iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

from mitochondria

A mitochondrion () is an organelle found in the cells of most eukaryotes, such as animals, plants and fungi. Mitochondria have a double membrane structure and use aerobic respiration to generate adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is us ...

, inflicting damage on this organelle. Since pyoverdine is secreted into the environment, it can be easily detected by the host or predator, resulting the host/predator migration towards the bacteria.

Phenazines

Phenazines

Phenazine is an organic compound with the formula (C6H4)2N2. It is a dibenzo annulated pyrazine, and the parent substance of many dyestuffs, such as the toluylene red, indulines, and safranines (and the closely related eurhodines). Phenazine c ...

are redox-active pigments produced by ''P. aeruginosa''. These pigments are involved in quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signaling (QS) is the process of cell-to-cell communication that allows bacteria to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation, typically as a means of acclimating to environmental disadv ...

, virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most cases, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its abili ...

, and iron acquisition. ''P. aeruginosa'' produces several pigments all produced by a biosynthetic pathway: phenazine-1-carboxamide (PCA), 1-hydroxyphenazine, 5-methylphenazine-1-carboxylic acid betaine, pyocyanin

Pyocyanin (PCN−) is one of the many toxic compounds produced and secreted by the Gram negative bacterium ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa''. Pyocyanin is a blue secondary metabolite, turning red below pH 4.9, with the ability to oxidise and reduce other ...

and aeruginosin A. Two nearly identical operons are involved in phenazine biosynthesis: ''phzA1B1C1D1E1F1G1'' and ''phzA2B2C2D2E2F2G2''. The enzymes encoded by these operons convert chorismic acid

Chorismic acid, more commonly known as its ion, anionic form chorismate, is an important biochemical intermediate in plants and microorganisms. It is a precursor for:

* The aromatic amino acids phenylalanine, tryptophan, and tyrosine

* Indole, ind ...

to PCA. The products of three key genes, ''phzH'', ''phzM'', and ''phzS'' then convert PCA to the other phenazines mentioned above. Though phenazine biosynthesis is well studied, questions remain as to the final structure of the brown phenazine

Phenazine is an organic compound with the formula (C6H4)2N2. It is a dibenzo annulation, annulated pyrazine, and the parent substance of many dyestuffs, such as the toluylene red, indulines, and safranines (and the closely related eurhodines). Phe ...

pyomelanin.

When pyocyanin biosynthesis is inhibited, a decrease in ''P. aeruginosa'' pathogenicity is observed ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

''. This suggests that pyocyanin is mostly responsible for the initial colonization of ''P. aeruginosa'' ''in vivo''.

Triggers

With lowphosphate

Phosphates are the naturally occurring form of the element phosphorus.

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthop ...

levels, ''P. aeruginosa'' has been found to activate from benign symbiont to express lethal toxins inside the intestinal tract and severely damage or kill the host, which can be mitigated by providing excess phosphate instead of antibiotics.

Plants and invertebrates

In higher plants, ''P. aeruginosa'' induces soft rot, for example in ''Arabidopsis thaliana

''Arabidopsis thaliana'', the thale cress, mouse-ear cress or arabidopsis, is a small plant from the mustard family (Brassicaceae), native to Eurasia and Africa. Commonly found along the shoulders of roads and in disturbed land, it is generally ...

'' (Thale cress) and ''Lactuca sativa

Lettuce (''Lactuca sativa'') is an annual plant of the family Asteraceae mostly grown as a leaf vegetable. The leaves are most often used raw in green salads, although lettuce is also seen in other kinds of food, such as sandwiches, wraps an ...

'' (lettuce). It is also pathogenic to invertebrate animals, including the nematode ''Caenorhabditis elegans

''Caenorhabditis elegans'' () is a free-living transparent nematode about 1 mm in length that lives in temperate soil environments. It is the type species of its genus. The name is a Hybrid word, blend of the Greek ''caeno-'' (recent), ''r ...

'', the fruit fly ''Drosophila

''Drosophila'' (), from Ancient Greek δρόσος (''drósos''), meaning "dew", and φίλος (''phílos''), meaning "loving", is a genus of fly, belonging to the family Drosophilidae, whose members are often called "small fruit flies" or p ...

'', and the moth ''Galleria mellonella

''Galleria mellonella'', the greater wax moth or honeycomb moth, is a moth of the family Pyralidae. ''G. mellonella'' is found throughout the world. It is one of two species of wax moths, with the other being the lesser wax moth. ''G. mellonella' ...

.'' The associations of virulence factors are the same for plant and animal infections. In both insects and plants, ''P. aeruginosa'' virulence

Virulence is a pathogen's or microorganism's ability to cause damage to a host.

In most cases, especially in animal systems, virulence refers to the degree of damage caused by a microbe to its host. The pathogenicity of an organism—its abili ...

is highly quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signaling (QS) is the process of cell-to-cell communication that allows bacteria to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation, typically as a means of acclimating to environmental disadv ...

(QS) dependent. Its QS is in turn highly dependent upon such genes as acyl-homoserine-lactone synthase, and lasI.

Quorum sensing

''P. aeruginosa'' is an opportunistic pathogen with the ability to coordinate gene expression in order to compete against other species for nutrients or colonization. Regulation ofgene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

can occur through cell-cell communication or quorum sensing

In biology, quorum sensing or quorum signaling (QS) is the process of cell-to-cell communication that allows bacteria to detect and respond to cell population density by gene regulation, typically as a means of acclimating to environmental disadv ...

(QS) via the production of small molecules called autoinducer

In biology, an autoinducer is a signaling molecule that enables detection and response to changes in the population density of bacterial cells. Synthesized when a bacterium reproduces, autoinducers pass outside the bacterium and into the surround ...

s that are released into the external environment. These signals, when reaching specific concentrations correlated with specific population cell densities, activate their respective regulators thus altering gene expression and coordinating behavior. ''P. aeruginosa'' employs five interconnected QS systems'' ''– las, rhl, pqs, iqs, and pch'' ''– that each produce unique signaling molecules. The las and rhl systems are responsible for the activation of numerous QS-controlled genes, the pqs system is involved in quinolone signaling, and the iqs system plays an important role in intercellular communication. QS in ''P. aeruginosa'' is organized in a hierarchical manner. At the top of the signaling hierarchy is the las system, since the las regulator initiates the QS regulatory system by activating the transcription of a number of other regulators, such as rhl. So, the las system defines a hierarchical QS cascade from the las to the rhl regulons. Detection of these molecules indicates ''P. aeruginosa'' is growing as biofilm within the lungs of cystic fibrosis patients. The impact of QS and especially las systems on the pathogenicity of ''P. aeruginosa'' is unclear, however. Studies have shown that lasR-deficient mutants are associated with more severe outcomes in cystic fibrosis patients and are found in up to 63% of chronically infected cystic fibrosis patients despite impaired QS activity.

QS is known to control expression of a number of virulence factors

Virulence factors (preferably known as pathogenicity factors or effectors in botany) are cellular structures, molecules and regulatory systems that enable microbial pathogens (bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa) to achieve the following:

* co ...

in a hierarchical manner, including the pigment pyocyanin. However, although the las system initiates the regulation of gene expression, its absence does not lead to loss of virulence factors. Recently, it has been demonstrated that the rhl system partially controls las-specific factors, such as proteolytic enzymes responsible for elastolytic and staphylolytic activities, but in a delayed manner. So, las is a direct and indirect regulator of QS-controlled genes. Another form of gene regulation

Regulation of gene expression, or gene regulation, includes a wide range of mechanisms that are used by cells to increase or decrease the production of specific gene products (protein or RNA). Sophisticated programs of gene expression are wide ...

that allows the bacteria to rapidly adapt to surrounding changes is through environmental signaling. Recent studies have discovered anaerobiosis can significantly impact the major regulatory circuit of QS. This important link between QS and anaerobiosis has a significant impact on production of virulence factors of this organism. Garlic

Garlic (''Allium sativum'') is a species of bulbous flowering plants in the genus '' Allium''. Its close relatives include the onion, shallot, leek, chives, Welsh onion, and Chinese onion. Garlic is native to central and south Asia, str ...

experimentally blocks quorum sensing in ''P. aeruginosa''.

Biofilms formation and cyclic di-GMP

As in most Gram negative bacteria, ''P. aeruginosa''biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

formation is regulated by one single molecule: cyclic di-GMP

Cyclic di-GMP (also called cyclic diguanylate and c-di- GMP) is a second messenger used in signal transduction in a wide variety of bacteria. Cyclic di-GMP is not known to be used by archaea, and has only been observed in eukaryotes in ''Dictyost ...

. At low cyclic di-GMP concentration, ''P. aeruginosa'' has a free-swimming mode of life. But when cyclic di-GMP levels increase, ''P. aeruginosa'' start to establish sessile communities on surfaces. The intracellular concentration of cyclic di-GMP increases within seconds when ''P. aeruginosa'' touches a surface (''e.g.'': a rock, plastic, host tissues...). This activates the production of adhesive pili

A pilus (Latin for 'hair'; : pili) is a hair-like cell-surface appendage found on many bacteria and archaea. The terms ''pilus'' and '' fimbria'' (Latin for 'fringe'; plural: ''fimbriae'') can be used interchangeably, although some researchers r ...

, that serve as "anchors" to stabilize the attachment of ''P. aeruginosa'' on the surface. At later stages, bacteria will start attaching irreversibly by producing a strongly adhesive matrix. At the same time, cyclic di-GMP represses the synthesis of the flagellar machinery, preventing ''P. aeruginosa'' from swimming. When suppressed, the biofilms are less adherent and easier to treat.

The biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

matrix of ''P. aeruginosa'' is composed of nucleic acids, amino acids, carbohydrates, and various ions. It mechanically and chemically protects ''P. aeruginosa'' from aggression by the immune system and some toxic compounds. ''P. aeruginosa'' biofilm's matrix is composed of up to three types of sugar polymers (or "exopolysaccharides") named PSL, PEL, and alginate. Which exopolysaccharides are produced varies by strain.

* The polysaccharide synthesis operon

In genetics, an operon is a functioning unit of DNA containing a cluster of genes under the control of a single promoter. The genes are transcribed together into an mRNA strand and either translated together in the cytoplasm, or undergo splic ...

and cyclic di-GMP form a positive feedback loop. This 15-gene operon is responsible for the cell-cell and cell-surface interactions required for cell communication.

* PEL is a cationic exopolysaccharide that cross-links extracellular DNA in the ''P. aeruginosa'' biofilm matrix.

Upon certain cues or stresses, ''P. aeruginosa'' revert the biofilm program and detach. Recent studies have shown that the dispersed cells from ''P. aeruginosa'' biofilms have lower cyclic di-GMP levels and different physiologies from those of planktonic and biofilm cells, with unique population dynamics and motility. Such dispersed cells are found to be highly virulent against macrophages and ''C. elegans'', but highly sensitive towards iron stress, as compared with planktonic cells.

Biofilms and treatment resistance

Biofilm

A biofilm is a Syntrophy, syntrophic Microbial consortium, community of microorganisms in which cell (biology), cells cell adhesion, stick to each other and often also to a surface. These adherent cells become embedded within a slimy ext ...

s of ''P. aeruginosa'' can cause chronic opportunistic infection

An opportunistic infection is an infection that occurs most commonly in individuals with an immunodeficiency disorder and acts more severe on those with a weakened immune system. These types of infections are considered serious and can be caused b ...

s, which are a serious problem for medical care in industrialized societies, especially for immunocompromised patients and the elderly. They often cannot be treated effectively with traditional antibiotic

An antibiotic is a type of antimicrobial substance active against bacteria. It is the most important type of antibacterial agent for fighting pathogenic bacteria, bacterial infections, and antibiotic medications are widely used in the therapy ...

therapy. Biofilms serve to protect these bacteria from adverse environmental factors, including host immune system components in addition to antibiotics. ''P. aeruginosa'' can cause nosocomial infections and is considered a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

for the study of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Researchers consider it important to learn more about the molecular mechanisms that cause the switch from planktonic growth to a biofilm phenotype and about the role of QS in treatment-resistant bacteria such as ''P. aeruginosa''. This should contribute to better clinical management of chronically infected patients, and should lead to the development of new drugs.

Scientists have been examining the possible genetic basis for ''P. aeruginosa'' resistance to antibiotics such as tobramycin

Tobramycin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic derived from '' Streptomyces tenebrarius'' that is used to treat various types of bacterial infections, particularly Gram-negative infections. It is especially effective against species of ''Pseudomo ...

. One locus

Locus (plural loci) is Latin for "place". It may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Locus (mathematics), the set of points satisfying a particular condition, often forming a curve

* Root locus analysis, a diagram visualizing the position of r ...

identified as being an important genetic determinant of the resistance in this species is ''ndvB'', which encodes periplasm

The periplasm is a concentrated gel-like matrix in the space between the inner cytoplasmic membrane and the bacterial outer membrane called the ''periplasmic space'' in Gram-negative (more accurately "diderm") bacteria. Using cryo-electron micros ...

ic glucan

A glucan is a polysaccharide derived from D-glucose, linked by glycosidic bonds. Glucans are noted in two forms: alpha glucans and beta glucans. Many beta-glucans are medically important. They represent a drug target for antifungal medications of ...

s that may interact with antibiotics and cause them to become sequestered into the periplasm. These results suggest a genetic basis exists behind bacterial antibiotic resistance, rather than the biofilm simply acting as a diffusion barrier to the antibiotic.

Diagnosis

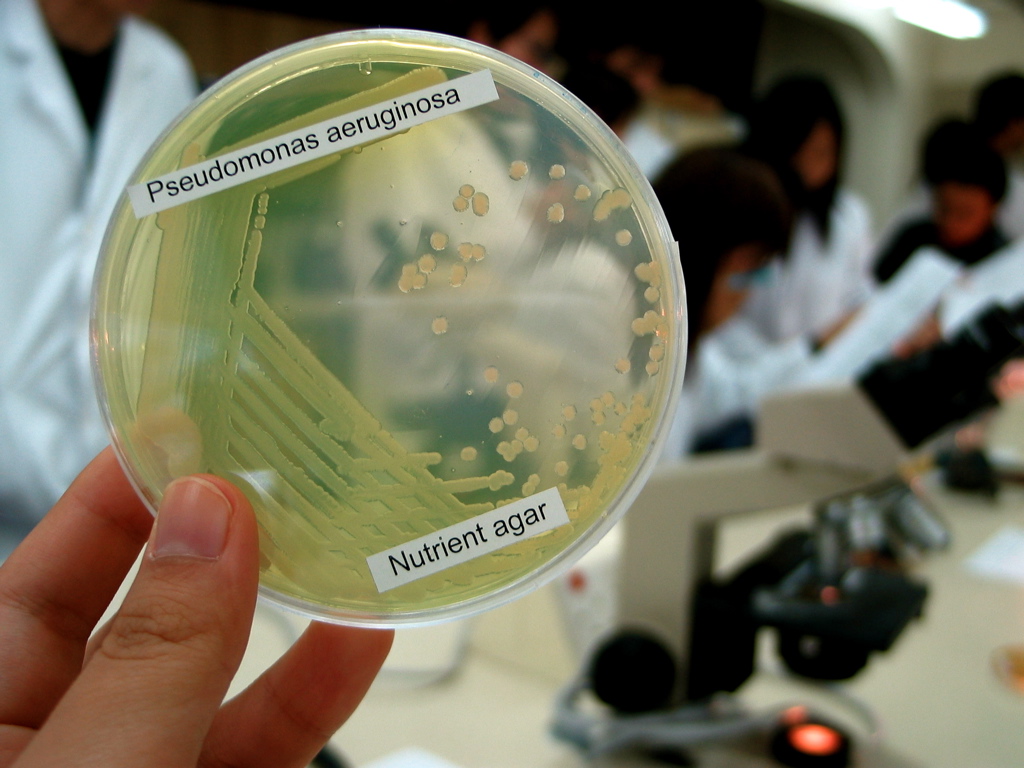

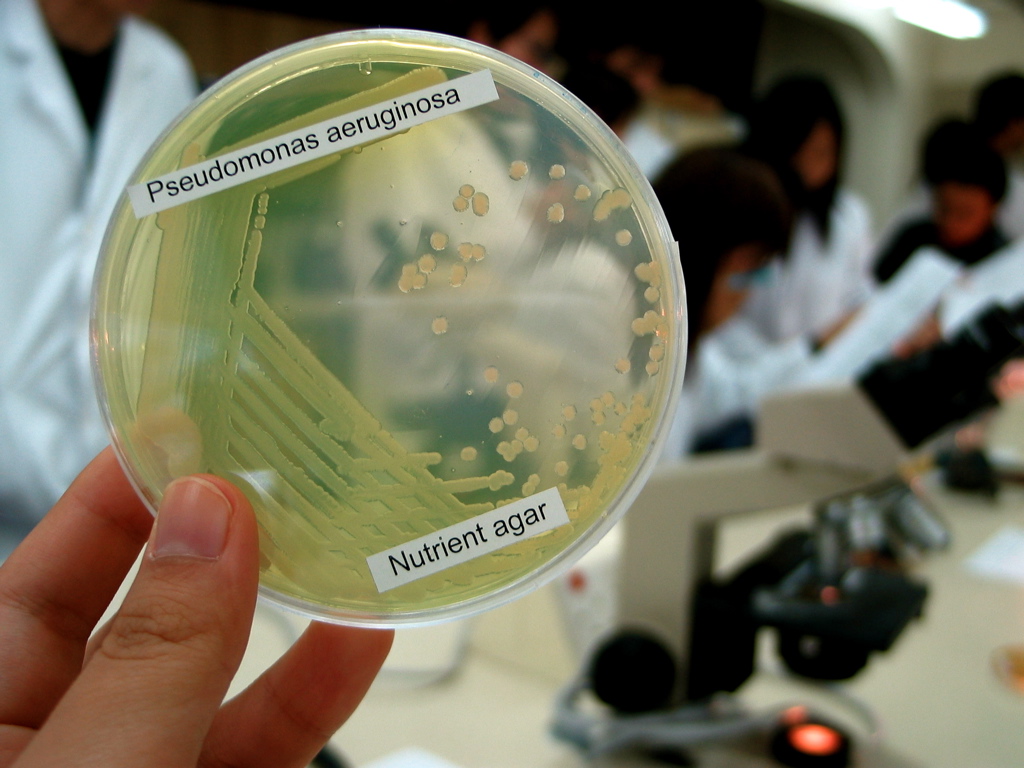

Depending on the nature of infection, an appropriate specimen is collected and sent to a

Depending on the nature of infection, an appropriate specimen is collected and sent to a bacteriology

Bacteriology is the branch and specialty of biology that studies the Morphology (biology), morphology, ecology, genetics and biochemistry of bacteria as well as many other aspects related to them. This subdivision of microbiology involves the iden ...

laboratory for identification. As with most bacteriological specimens, a Gram stain

Gram stain (Gram staining or Gram's method), is a method of staining used to classify bacterial species into two large groups: gram-positive bacteria and gram-negative bacteria. It may also be used to diagnose a fungal infection. The name comes ...

is performed, which may show Gram-negative rods and/or white blood cells

White blood cells (scientific name leukocytes), also called immune cells or immunocytes, are cells of the immune system that are involved in protecting the body against both infectious disease and foreign entities. White blood cells are genera ...

. ''P. aeruginosa'' produces colonies with a characteristic "grape-like" or "fresh-tortilla" odor on bacteriological media. In mixed cultures, it can be isolated as clear colonies on MacConkey agar

MacConkey agar is a selective and differential culture medium for bacteria. It is designed to selectively isolate gram-negative and enteric (normally found in the intestinal tract) bacteria and differentiate them based on lactose fermentatio ...

(as it does not ferment lactose

Lactose is a disaccharide composed of galactose and glucose and has the molecular formula C12H22O11. Lactose makes up around 2–8% of milk (by mass). The name comes from (Genitive case, gen. ), the Latin word for milk, plus the suffix ''-o ...

) which will test positive for oxidase

In biochemistry, an oxidase is an oxidoreductase (any enzyme that catalyzes a redox reaction) that uses dioxygen (O2) as the electron acceptor. In reactions involving donation of a hydrogen atom, oxygen is reduced to water (H2O) or hydrogen peroxid ...

. Confirmatory tests include production of the blue-green pigment pyocyanin on cetrimide agar and growth at 42 °C. A TSI slant

250px, TSI agar slant results: (from left) preinoculated (as control),

''P. aeruginosa'', ''E. coli'', '' Shigella_flexneri.html" ;"title="Salmonella Typhimurium'', ''Shigella flexneri">Salmonella Typhimurium'', ''Shigella flexneri''

The Tripl ...

is often used to distinguish nonfermenting ''Pseudomonas'' species from enteric pathogens in faecal specimens.

When ''P. aeruginosa'' is isolated from a normally sterile site (blood, bone, deep collections), it is generally considered dangerous, and almost always requires treatment. However, ''P. aeruginosa'' is frequently isolated from nonsterile sites (mouth swabs, sputum

Sputum is mucus that is coughed up from the lower airways (the trachea and bronchi). In medicine, sputum samples are usually used for a naked-eye examination, microbiological investigation of respiratory infections, and Cytopathology, cytological ...

, etc.), and, under these circumstances, it may represent colonization and not infection. The isolation of ''P. aeruginosa'' from nonsterile specimens should, therefore, be interpreted cautiously, and the advice of a microbiologist

A microbiologist (from Greek ) is a scientist who studies microscopic life forms and processes. This includes study of the growth, interactions and characteristics of microscopic organisms such as bacteria, algae, fungi, and some types of par ...

or infectious diseases physician/pharmacist should be sought prior to starting treatment. Often, no treatment is needed.

Classification

Morphological, physiological, and biochemical characteristics of ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' are shown in the Table below. Note: + = Positive, - =Negative ''P. aeruginosa'' is a Gram-negative,aerobic

Aerobic means "requiring air," in which "air" usually means oxygen.

Aerobic may also refer to

* Aerobic exercise, prolonged exercise of moderate intensity

* Aerobics, a form of aerobic exercise

* Aerobic respiration, the aerobic process of cellu ...

(and at times facultatively anaerobic

A facultative anaerobic organism is an organism that makes ATP by aerobic respiration if oxygen is present, but is capable of switching to fermentation if oxygen is absent.

Some examples of facultatively anaerobic bacteria are ''Staphylococcus' ...

), rod-shaped bacterium with unipolar motility. It has been identified as an opportunistic pathogen

An opportunistic infection is an infection that occurs most commonly in individuals with an immunodeficiency disorder and acts more severe on those with a weakened immune system. These types of infections are considered serious and can be caused b ...

of both humans and plants. ''P. aeruginosa'' is the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

of the genus ''Pseudomonas

''Pseudomonas'' is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the family Pseudomonadaceae in the class Gammaproteobacteria. The 348 members of the genus demonstrate a great deal of metabolic diversity and consequently are able to colonize a ...

''.

Identification of ''P. aeruginosa'' can be complicated by the fact individual isolates often lack motility. The colony morphology itself also displays several varieties. The main two types are large, smooth, with a flat edge and elevated center and small, rough, and convex. A third type, mucoid, can also be found. The large colony can typically be found in clinal settings while the small is found in nature. The third, however, is present in biological settings and has been found in respiratory and in the urinary tract. Furthermore, mutations in the gene lasR drastically alter colony morphology and typically lead to failure to hydrolyze gelatin or hemolyze.

In certain conditions, ''P. aeruginosa'' can secrete a variety of pigments, including pyocyanin

Pyocyanin (PCN−) is one of the many toxic compounds produced and secreted by the Gram negative bacterium ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa''. Pyocyanin is a blue secondary metabolite, turning red below pH 4.9, with the ability to oxidise and reduce other ...

(blue), pyoverdine

Pyoverdines (alternatively, and less commonly, spelled as pyoverdins) are fluorescent siderophores produced by certain pseudomonads. Pyoverdines are important virulence factors, and are required for pathogenesis in many biological models of infec ...

(yellow and fluorescent

Fluorescence is one of two kinds of photoluminescence, the emission of light by a substance that has absorbed light or other electromagnetic radiation. When exposed to ultraviolet radiation, many substances will glow (fluoresce) with color ...

), pyorubin (red), and pyomelanin (brown). These can be used to identify the organism.

Clinical identification of ''P. aeruginosa'' may include identifying the production of both pyocyanin and fluorescein, as well as its ability to grow at 42 °C. ''P. aeruginosa'' is capable of growth in diesel

Diesel may refer to:

* Diesel engine, an internal combustion engine where ignition is caused by compression

* Diesel fuel, a liquid fuel used in diesel engines

* Diesel locomotive, a railway locomotive in which the prime mover is a diesel engine ...

and jet fuel

Jet fuel or aviation turbine fuel (ATF, also abbreviated avtur) is a type of aviation fuel designed for use in aircraft powered by Gas turbine, gas-turbine engines. It is colorless to straw-colored in appearance. The most commonly used fuels for ...

s, where it is known as a hydrocarbon

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and Hydrophobe, hydrophobic; their odor is usually fain ...

-using microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

, causing microbial corrosion

Microbial corrosion, also known as microbiologically influenced corrosion (MIC), microbially induced corrosion (MIC) or biocorrosion, occurs when microbes affect the electrochemical environment of the surface on which they are fixed. This usually ...

. It creates dark, gellish mats sometimes improperly called "algae

Algae ( , ; : alga ) is an informal term for any organisms of a large and diverse group of photosynthesis, photosynthetic organisms that are not plants, and includes species from multiple distinct clades. Such organisms range from unicellular ...

" because of their appearance.

Treatment

Many ''P. aeruginosa'' isolates are resistant to a large range of antibiotics and may demonstrate additional resistance after unsuccessful treatment. It should usually be possible to guide treatment according to laboratory sensitivities, rather than choosing an antibioticempirically

In philosophy, empiricism is an Epistemology, epistemological view which holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from Sense, sensory experience and empirical evidence. It is one of several competing views within ...

. If antibiotics are started empirically, then every effort should be made to obtain cultures (before administering the first dose of antibiotic), and the choice of antibiotic used should be reviewed when the culture results are available.

Due to widespread resistance to many common first-line antibiotics,

Due to widespread resistance to many common first-line antibiotics, carbapenems

Carbapenems are a class of very effective antibiotic agents most commonly used for treatment of severe bacterial infections. This class of antibiotics is usually reserved for known or suspected multidrug-resistant (MDR) bacterial infections. Simi ...

, polymyxins, and more recently tigecycline

Tigecycline, sold under the brand name Tygacil, is a tetracycline antibiotic medication for a number of bacterial infections. It is a glycylcycline class drug that is administered intravenously. It was developed in response to the growing ra ...

were considered to be the drugs of choice; however, resistance to these drugs has also been reported. Despite this, they are still being used in areas where resistance has not yet been reported. Use of β-lactamase inhibitors such as sulbactam has been advised in combination with antibiotics to enhance antimicrobial action even in the presence of a certain level of resistance. Combination therapy after rigorous antimicrobial susceptibility testing has been found to be the best course of action in the treatment of multidrug-resistant ''P. aeruginosa''. Some next-generation antibiotics that are reported as being active against ''P. aeruginosa'' include doripenem, ceftobiprole, and ceftaroline. However, these require more clinical trials for standardization. Therefore, research for the discovery of new antibiotics and drugs against ''P. aeruginosa'' is very much needed.

Antibiotics that may have activity against ''P. aeruginosa'' include:

* aminoglycoside

Aminoglycoside is a medicinal and bacteriologic category of traditional Gram-negative antibacterial medications that inhibit protein synthesis and contain as a portion of the molecule an amino-modified glycoside (sugar). The term can also refer ...

s (gentamicin

Gentamicin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic used to treat several types of bacterial infections. This may include bone infections, endocarditis, pelvic inflammatory disease, meningitis, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis amo ...

, amikacin

Amikacin is an antibiotic medication used for a number of bacterial infections. This includes joint infections, intra-abdominal infections, meningitis, pneumonia, sepsis, and urinary tract infections. It is also used for the treatment of ...

, tobramycin

Tobramycin is an aminoglycoside antibiotic derived from '' Streptomyces tenebrarius'' that is used to treat various types of bacterial infections, particularly Gram-negative infections. It is especially effective against species of ''Pseudomo ...

, but ''not'' kanamycin

Kanamycin A, often referred to simply as kanamycin, is an antibiotic used to treat severe bacterial infections and tuberculosis. It is not a first line treatment. It is used by mouth, injection into a vein, or injection into a muscle. Kanamy ...

)

* quinolones

Quinolone may refer to:

* 2-Quinolone

* 4-Quinolone

* Quinolone antibiotic

Quinolone antibiotics constitute a large group of broad-spectrum bacteriocidals that share a bicyclic core structure related to the substance 4-quinolone. They ar ...

(ciprofloxacin

Ciprofloxacin is a fluoroquinolone antibiotic used to treat a number of bacterial infections. This includes bone and joint infections, intra-abdominal infections, certain types of infectious diarrhea, respiratory tract infections, skin ...

, levofloxacin

Levofloxacin, sold under the brand name Levaquin among others, is a broad-spectrum antibiotic of the fluoroquinolone drug class. It is the left-handed isomer of the medication ofloxacin. It is used to treat a number of bacterial infections ...

, but not moxifloxacin

Moxifloxacin is an antibiotic, used to treat bacterial infections, including pneumonia, conjunctivitis, endocarditis, tuberculosis, and sinusitis. It can be given by mouth, by injection into a vein, and as an eye drop.

Common side effec ...

)

* cephalosporin

The cephalosporins (sg. ) are a class of β-lactam antibiotics originally derived from the fungus '' Acremonium'', which was previously known as ''Cephalosporium''.

Together with cephamycins, they constitute a subgroup of β-lactam antibio ...

s (ceftazidime

Ceftazidime, sold under the brand name Fortaz among others, is a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic useful for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. Specifically it is used for joint infections, meningitis, pneumonia, sepsi ...

, cefepime

Cefepime is a fourth-generation cephalosporin antibiotic. Cefepime has an extended spectrum of activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, with greater activity against both types of organism than third-generation agents. A 2007 ...

, cefoperazone

Cefoperazone is a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic, marketed by Pfizer under the name Cefobid. It is one of few cephalosporin antibiotics effective in treating ''Pseudomonas'' bacterial infections which are otherwise resistant to these a ...

, cefpirome, ceftobiprole

Ceftobiprole, sold under the brand name Zevtera among others, is a fifth-generation cephalosporin antibacterial used for the treatment of hospital-acquired pneumonia (excluding ventilator-associated pneumonia) and community-acquired pneumonia. ...

, but not cefuroxime

Cefuroxime, sold under the brand name Zinacef among others, is a second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic used to treat and prevent a number of bacterial infections. These include pneumonia, meningitis, otitis media, sepsis, urinary tract inf ...

, cefotaxime

Cefotaxime is an antibiotic used to treat several bacterial infections in humans, other animals, and plant tissue culture. Specifically in humans it is used to treat joint infections, pelvic inflammatory disease, meningitis, pneumonia, urin ...

, or ceftriaxone

Ceftriaxone, sold under the brand name Rocephin, is a third-generation cephalosporin antibiotic used for the treatment of a number of bacterial infections. These include middle ear infections, endocarditis, meningitis, pneumonia, bone and joi ...

)

* antipseudomonal penicillins

The extended-spectrum penicillins are a group of antibiotics that have the widest antibacterial spectrum of all penicillins. Some sources identify them with antipseudomonal penicillins, others consider these types to be distinct. This group include ...

: carboxypenicillin

The carboxypenicillins are a group of antibiotics. They belong to the penicillin family and comprise the members carbenicillin and ticarcillin.

Chemical structure

The carboxypenicillins feature the beta-lactam backbone of all penicillins b ...

s (carbenicillin

Carbenicillin is a bactericidal antibiotic belonging to the carboxypenicillin subgroup of the penicillins. It was discovered by scientists at Beecham and marketed as Pyopen. It has Gram-negative coverage which includes ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa' ...

and ticarcillin

Ticarcillin is a carboxypenicillin. It can be sold and used in combination with clavulanate as ticarcillin/clavulanic acid. Because it is a penicillin, it also falls within the larger class of beta-lactam, β-lactam antibiotics. Its main clinical ...

), and ureidopenicillin

The ureidopenicillins are a group of penicillins which are active against ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa''.

There are three ureidopenicillins in clinical use:

* Azlocillin

* Piperacillin

* Mezlocillin

They are mostly ampicillin derivatives in whic ...

s (mezlocillin

Mezlocillin is a broad-spectrum penicillin antibiotic. It is active against both Gram-negative and some Gram-positive bacteria. Unlike most other extended spectrum penicillins, it is excreted by the liver, therefore it is useful for biliary tract ...

, azlocillin

Azlocillin is an acyl ampicillin antibiotic with an extended spectrum of activity and greater ''in vitro'' potency than the carboxy penicillins.

Azlocillin is similar to mezlocillin and piperacillin. It demonstrates antibacterial activity aga ...

, and piperacillin

Piperacillin is a broad-spectrum β-lactam antibiotic of the ureidopenicillin class. The chemical structure of piperacillin and other ureidopenicillins incorporates a polar side chain that enhances penetration into Gram-negative bacteria and red ...

). ''P. aeruginosa'' is intrinsically resistant to all other penicillin

Penicillins (P, PCN or PEN) are a group of beta-lactam antibiotic, β-lactam antibiotics originally obtained from ''Penicillium'' Mold (fungus), moulds, principally ''Penicillium chrysogenum, P. chrysogenum'' and ''Penicillium rubens, P. ru ...

s.

* carbapenem