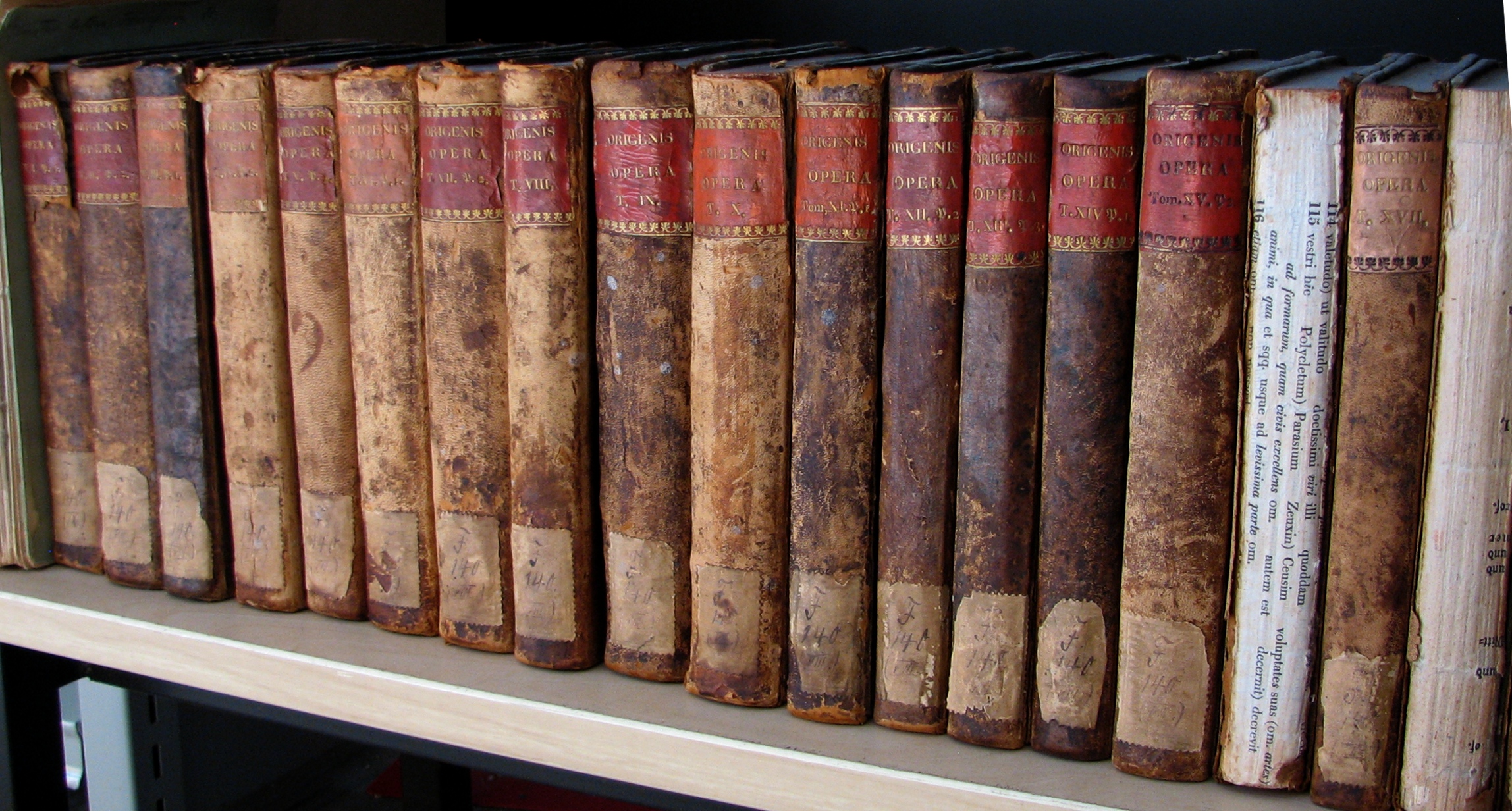

Origenes Opera on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Origen of Alexandria (), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an

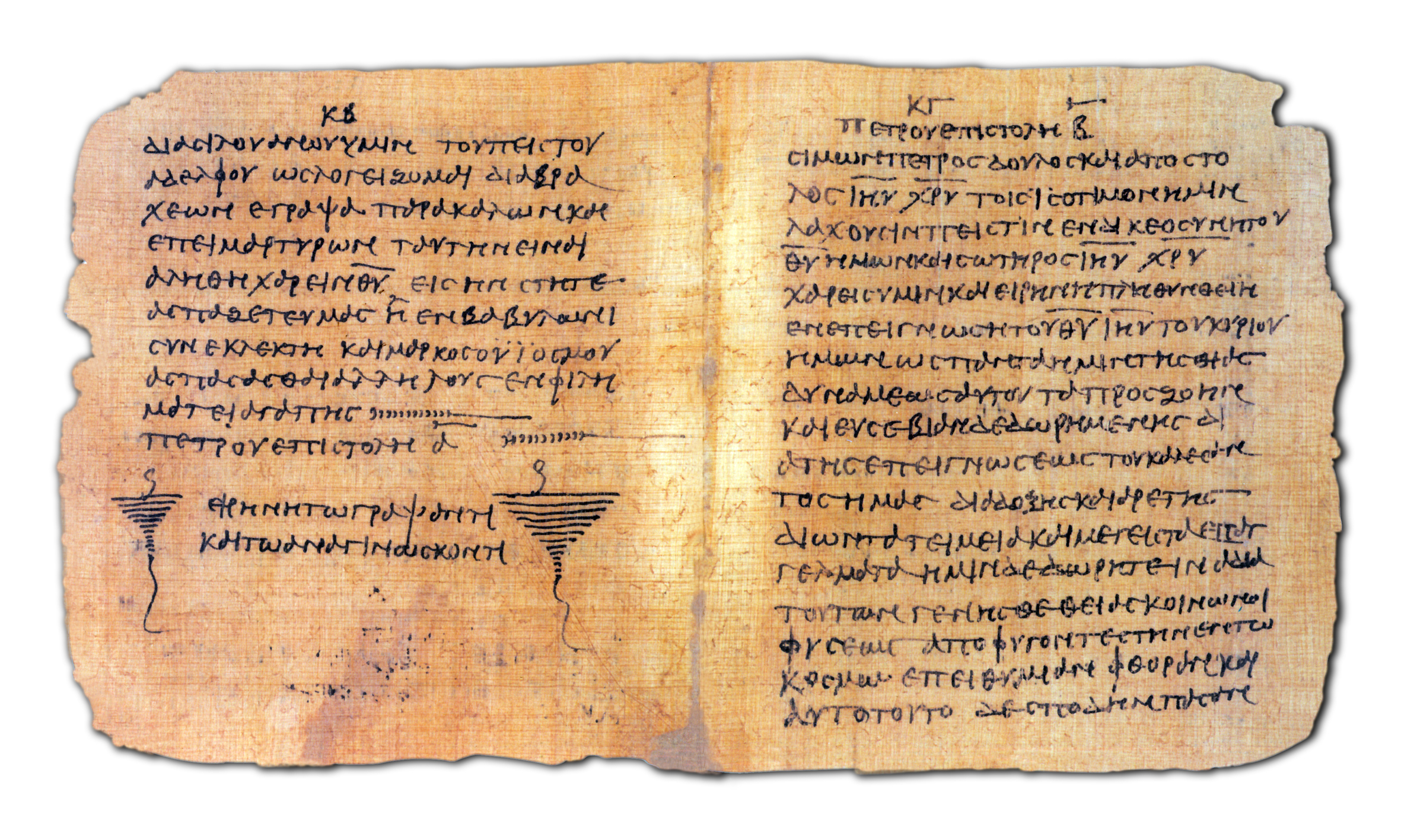

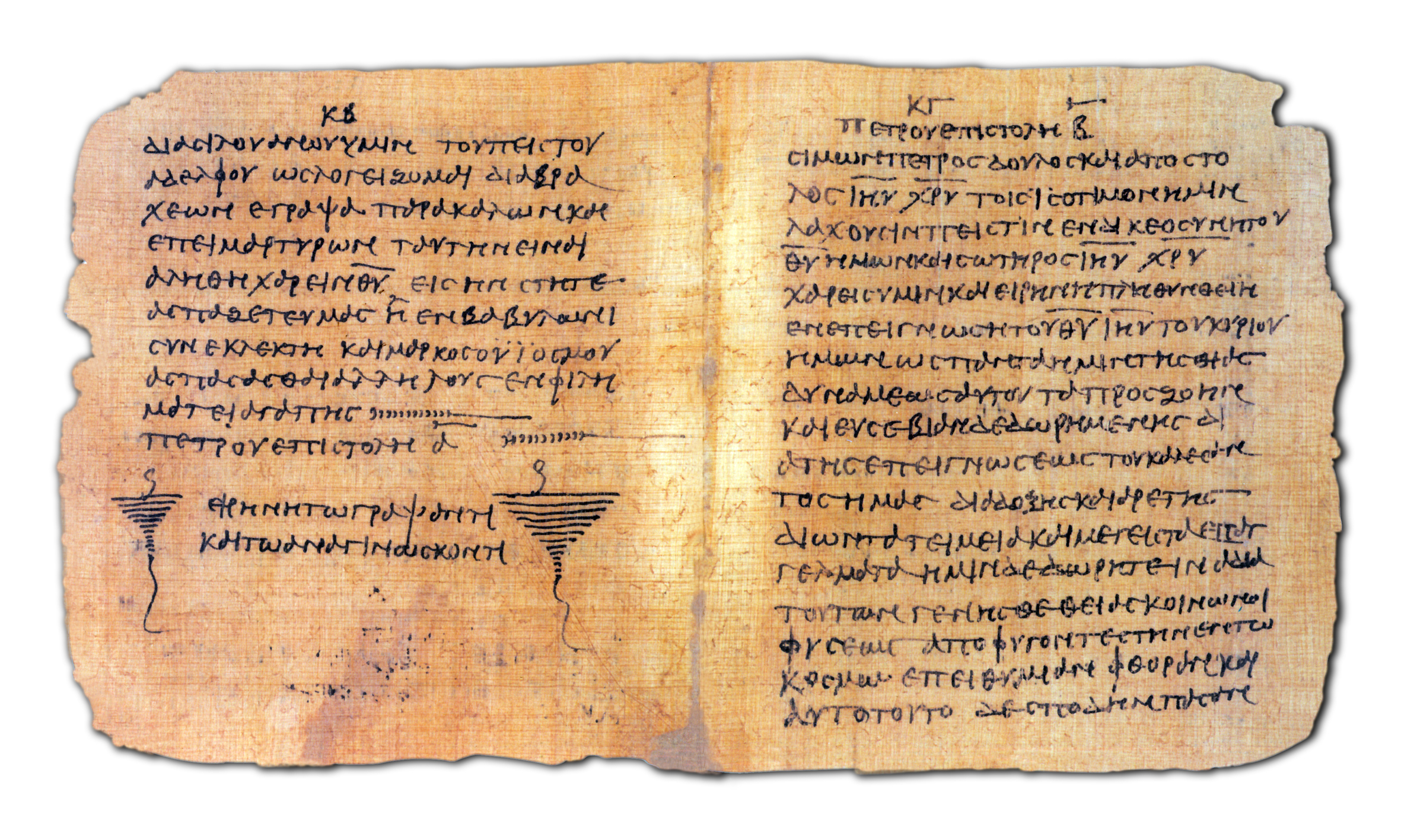

Origen obeyed Demetrius's order and returned to Alexandria, bringing with him an antique scroll he had purchased at

Origen obeyed Demetrius's order and returned to Alexandria, bringing with him an antique scroll he had purchased at  Origen also studied the entire

Origen also studied the entire

Pagans also took a fascination with Origen. The

Pagans also took a fascination with Origen. The

The was the cornerstone of the Great Library of Caesarea, which Origen founded. It was still the centerpiece of the library's collection by the time of Jerome, who records having used it in his letters on multiple occasions. When Emperor

The was the cornerstone of the Great Library of Caesarea, which Origen founded. It was still the centerpiece of the library's collection by the time of Jerome, who records having used it in his letters on multiple occasions. When Emperor  The homilies preserved are on Genesis (16), Exodus (13), Leviticus (16), Numbers (28), Joshua (26), Judges (9), I Sam. (2), Psalms 36–38 (9), Canticles (2), Isaiah (9), Jeremiah (7 Greek, 2 Latin, 12 Greek and Latin), Ezekiel (14), and Luke (39). The homilies were preached in the church at Caesarea, with the exception of the two on 1 Samuel which were delivered in Jerusalem. Nautin has argued that they were all preached in a three-year liturgical cycle some time between 238 and 244, preceding the ''Commentary on the Song of Songs'', where Origen refers to homilies on Judges, Exodus, Numbers, and a work on Leviticus. On June 11, 2012, the

The homilies preserved are on Genesis (16), Exodus (13), Leviticus (16), Numbers (28), Joshua (26), Judges (9), I Sam. (2), Psalms 36–38 (9), Canticles (2), Isaiah (9), Jeremiah (7 Greek, 2 Latin, 12 Greek and Latin), Ezekiel (14), and Luke (39). The homilies were preached in the church at Caesarea, with the exception of the two on 1 Samuel which were delivered in Jerusalem. Nautin has argued that they were all preached in a three-year liturgical cycle some time between 238 and 244, preceding the ''Commentary on the Song of Songs'', where Origen refers to homilies on Judges, Exodus, Numbers, and a work on Leviticus. On June 11, 2012, the

archive

/ref> The information used to create the late-fourth-century

Origen's commentaries written on specific books of scripture are much more focused on systematic exegesis than his homilies. In these writings, Origen applies the precise critical methodology that had been developed by the scholars of the

Origen's commentaries written on specific books of scripture are much more focused on systematic exegesis than his homilies. In these writings, Origen applies the precise critical methodology that had been developed by the scholars of the

''Against Celsus'' ( ; Latin: ), preserved entirely in Greek, was Origen's last treatise, written about 248. It is an apologetic work defending orthodox Christianity against the attacks of the pagan philosopher

''Against Celsus'' ( ; Latin: ), preserved entirely in Greek, was Origen's last treatise, written about 248. It is an apologetic work defending orthodox Christianity against the attacks of the pagan philosopher

One of Origen's main teachings was the doctrine of the preexistence of souls, which held that before God created the material world he created a vast number of incorporeal " spiritual intelligences" ( ). All of these souls were at first devoted to the contemplation and love of their Creator, but as the fervor of the divine fire cooled, almost all of these intelligences eventually grew bored of contemplating God, and their love for him "cooled off" ( ). When God created the world, the souls which had previously existed without bodies became incarnate. Those whose love for God diminished the most became

One of Origen's main teachings was the doctrine of the preexistence of souls, which held that before God created the material world he created a vast number of incorporeal " spiritual intelligences" ( ). All of these souls were at first devoted to the contemplation and love of their Creator, but as the fervor of the divine fire cooled, almost all of these intelligences eventually grew bored of contemplating God, and their love for him "cooled off" ( ). When God created the world, the souls which had previously existed without bodies became incarnate. Those whose love for God diminished the most became

Origen was an ardent believer in

Origen was an ardent believer in

Origen's conception of God the Father is apophatic—a perfect unity, invisible and incorporeal, transcending all things material, and therefore inconceivable and incomprehensible. He is likewise unchangeable and transcends space and time. But his power is limited by his goodness, justice, and wisdom; and, though entirely free from necessity, his goodness and omnipotence constrained him to reveal himself. This revelation, the external self-emanation of God, is expressed by Origen in various ways, the Logos being only one of many. The revelation was the first creation of God (cf. Proverbs 8:22), in order to afford creative mediation between God and the world, such mediation being necessary, because God, as changeless unity, could not be the source of a multitudinous creation.

The Logos is the rational creative principle that permeates the universe. The Logos acts on all human beings through their capacity for logic and rational thought, guiding them to the truth of God's revelation. As they progress in their rational thinking, all humans become more like Christ. Nonetheless, they retain their individuality and do not become subsumed into Christ. Creation came into existence only through the Logos, and God's nearest approach to the world is the command to create. While the Logos is substantially a unity, he comprehends a multiplicity of concepts, so that Origen terms him, in Platonic fashion, "essence of essences" and "idea of ideas".

The focused understanding of the Logos, along with the paradigms of participation carried from Greek philosophy, allowed Origen to have a major role in the development of the concept of human deification or . Origen believed that Christ's humanity was deified and this deification spread to all the believers. By participating in the very Logos himself, we become participants in divinity. Origen, however, concluded that only those who are created in God's image and live a life of virtue can deified; virtue for Origen is linked to the person of Jesus Christ. Thus, he excluded all inanimate objects or animals (previously seen as divine in some pagan polytheistic systems), and also excluded the pagan heroes from this perceived deification.

Origen significantly contributed to the development of the idea of the

Origen's conception of God the Father is apophatic—a perfect unity, invisible and incorporeal, transcending all things material, and therefore inconceivable and incomprehensible. He is likewise unchangeable and transcends space and time. But his power is limited by his goodness, justice, and wisdom; and, though entirely free from necessity, his goodness and omnipotence constrained him to reveal himself. This revelation, the external self-emanation of God, is expressed by Origen in various ways, the Logos being only one of many. The revelation was the first creation of God (cf. Proverbs 8:22), in order to afford creative mediation between God and the world, such mediation being necessary, because God, as changeless unity, could not be the source of a multitudinous creation.

The Logos is the rational creative principle that permeates the universe. The Logos acts on all human beings through their capacity for logic and rational thought, guiding them to the truth of God's revelation. As they progress in their rational thinking, all humans become more like Christ. Nonetheless, they retain their individuality and do not become subsumed into Christ. Creation came into existence only through the Logos, and God's nearest approach to the world is the command to create. While the Logos is substantially a unity, he comprehends a multiplicity of concepts, so that Origen terms him, in Platonic fashion, "essence of essences" and "idea of ideas".

The focused understanding of the Logos, along with the paradigms of participation carried from Greek philosophy, allowed Origen to have a major role in the development of the concept of human deification or . Origen believed that Christ's humanity was deified and this deification spread to all the believers. By participating in the very Logos himself, we become participants in divinity. Origen, however, concluded that only those who are created in God's image and live a life of virtue can deified; virtue for Origen is linked to the person of Jesus Christ. Thus, he excluded all inanimate objects or animals (previously seen as divine in some pagan polytheistic systems), and also excluded the pagan heroes from this perceived deification.

Origen significantly contributed to the development of the idea of the

The First Origenist Crisis began in the late fourth century, coinciding with the beginning of monasticism in Palestine. The first stirring of the controversy came from the

The First Origenist Crisis began in the late fourth century, coinciding with the beginning of monasticism in Palestine. The first stirring of the controversy came from the

''Volume 1''''Volume 2''

* ''Contra Celsum'', trans Henry Chadwick, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1965) * ''On First Principles'', trans GW Butterworth, (Gloucester, MA: Peter Smith, 1973) also trans

The Christian Platonists of Alexandria

'. 1886, revised 1913. * Bruns, Christoph (2013). ''Trinität und Kosmos. Zur Gotteslehre des Origenes'' rinity and cosmos. On the doctrine of God in Origen Adamantiana, vol. 3. Münster: Aschendorff, 2013. * * Fürst, Alfons (2017). ''Origenes. Grieche und Christ in römischer Zeit'' rigen. Greek and Christ in Roman Times Stuttgart: Hiersemann, . * Heine, Ronald E.; Torjesen, Karen Jo (eds). ''The Oxford Handbook of Origen.'' Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 2022. * Martens, Peter. ''Origen and Scripture: The Contours of the Exegetical Life.'' Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012. * * * * von Balthasar, Hans Urs. ''Origen, Spirit and Fire: A Thematic Anthology of His Writings''. Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1984. * Westcott, B. F.

Origenes

, ''

Coptic Church on Origen

*** The two-part Roman Catholic meditation on Origen by Pope Benedict XVI

an

**Ancient **

**

* Derivative summaries ** ** Edward Moore

** ** *

from New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge *Bibliography *

EarlyChurch.org.uk

Extensive bibliography and on-line articles. *Original texts *

*Other resources ** ttp://www.john-uebersax.com/plato/origen2.htm Table of Origen's Works with Links to Texts and Translations**

for

early Christian

Early Christianity, otherwise called the Early Church or Paleo-Christianity, describes the historical era of the Christian religion up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325. Christianity spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and be ...

scholar

A scholar is a person who is a researcher or has expertise in an academic discipline. A scholar can also be an academic, who works as a professor, teacher, or researcher at a university. An academic usually holds an advanced degree or a termina ...

, ascetic

Asceticism is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from worldly pleasures through self-discipline, self-imposed poverty, and simple living, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their pra ...

, and theologian

Theology is the study of religious belief from a religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of ...

who was born and spent the first half of his career in Alexandria

Alexandria ( ; ) is the List of cities and towns in Egypt#Largest cities, second largest city in Egypt and the List of coastal settlements of the Mediterranean Sea, largest city on the Mediterranean coast. It lies at the western edge of the Nile ...

. He was a prolific writer who wrote roughly 2,000 treatises in multiple branches of theology, including textual criticism

Textual criticism is a branch of textual scholarship, philology, and literary criticism that is concerned with the identification of textual variants, or different versions, of either manuscripts (mss) or of printed books. Such texts may rang ...

, biblical exegesis

Biblical studies is the academic application of a set of diverse disciplines to the study of the Bible, with ''Bible'' referring to the books of the canonical Hebrew Bible in mainstream Jewish usage and the Christian Bible including the can ...

and hermeneutics

Hermeneutics () is the theory and methodology of interpretation, especially the interpretation of biblical texts, wisdom literature, and philosophical texts. As necessary, hermeneutics may include the art of understanding and communication.

...

, homiletics

In religious studies, homiletics ( ''homilētikós'', from ''homilos'', "assembled crowd, throng") is the application of the general principles of rhetoric to the specific art of public preaching. One who practices or studies homiletics may be ...

, and spirituality. He was one of the most influential and controversial figures in early Christian theology, apologetics

Apologetics (from Greek ) is the religious discipline of defending religious doctrines through systematic argumentation and discourse. Early Christian writers (c. 120–220) who defended their beliefs against critics and recommended their f ...

, and asceticism. He has been described by John Anthony McGuckin

John Anthony McGuckin (born 1952) is a British theologian, church historian, Orthodox Christian priest and poet.

Education

McGuckin attended Heythrop College from 1970 to 1972, graduated from the University of London with a divinity degree in 1 ...

as "the greatest genius the early church ever produced".

Overview

Origen soughtmartyr

A martyr (, ''mártys'', 'witness' Word stem, stem , ''martyr-'') is someone who suffers persecution and death for advocating, renouncing, or refusing to renounce or advocate, a religious belief or other cause as demanded by an external party. In ...

dom with his father at a young age but was prevented from turning himself in to the authorities by his mother. When he was eighteen years old, Origen became a catechist

Catechesis (; from Greek language, Greek: , "instruction by word of mouth", generally "instruction") is basic Christian religious education of children and adults, often from a catechism book. It started as education of Conversion to Christia ...

at the or School of Alexandria

The Catechetical School of Alexandria was a school of Christian theologians and bishops and deacons in Alexandria. The teachers and students of the school (also known as the Didascalium) were influential in many of the early theological controve ...

. He devoted himself to his studies and adopted an ascetic lifestyle. He came into conflict with Demetrius, bishop of Alexandria, in 231 after he was ordained

Ordination is the process by which individuals are Consecration in Christianity, consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the religious denomination, denominationa ...

as a presbyter

Presbyter () is an honorific title for Christian clergy. The word derives from the Greek ''presbyteros'', which means elder or senior, although many in Christian antiquity understood ''presbyteros'' to refer to the bishop functioning as overseer ...

by his friend Theoclistus, the bishop of Caesarea

The archiepiscopal see of Caesarea in Palaestina, also known as Caesarea Maritima, is now a metropolitan see of the Eastern Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem and also a titular see of the Catholic Church.

It was one of the earliest Christian bish ...

, while on a journey to Athens through Palestine. Demetrius condemned Origen for insubordination and accused him of having castrated

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which a male loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmaceutical ...

himself and of having taught that even Satan

Satan, also known as the Devil, is a devilish entity in Abrahamic religions who seduces humans into sin (or falsehood). In Judaism, Satan is seen as an agent subservient to God, typically regarded as a metaphor for the '' yetzer hara'', or ' ...

would eventually attain salvation, an accusation which Origen vehemently denied.

Origen founded the Christian School of Caesarea, where he taught logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure o ...

, cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

, natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

, and theology, and became regarded by the churches of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

and Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

as the ultimate authority on all matters of theology. He was tortured for his faith during the Decian persecution

Christians were persecuted in 250 AD under the Decius, Roman emperor Decius. He had issued an edict ordering everyone in the empire to perform a sacrifice to the Roman gods and the well-being of the emperor. The sacrifices had to be performed ...

in 250 and died three to four years later from his injuries.

Origen produced a massive quantity of writings because of the patronage of his close friend Ambrose of Alexandria

Ambrose of Alexandria (before 212 – c. 250) was a friend of the Christian theologian Origen.

Life

Ambrose was attracted by Origen's fame as a teacher, and visited the Catechetical School of Alexandria in 212. At first a gnostic Valentinian a ...

, who provided him with a team of secretaries to copy his works, making him one of the most prolific writers in late antiquity

Late antiquity marks the period that comes after the end of classical antiquity and stretches into the onset of the Early Middle Ages. Late antiquity as a period was popularized by Peter Brown (historian), Peter Brown in 1971, and this periodiza ...

. His treatise ''On the First Principles

''On the First Principles'' (Greek: Περὶ Ἀρχῶν / ''Peri Archon''; Latin: ''De Principiis'') is a theological treatise by the Christian writer Origen. It was the first systematic exposition of Christian theology. It is thought to have b ...

'' systematically laid out the principles of Christian theology and became the foundation for later theological writings. He also authored , the most influential work of early Christian apologetics, in which he defended Christianity against the pagan philosopher Celsus

Celsus (; , ''Kélsos''; ) was a 2nd-century Greek philosopher and opponent of early Christianity. His literary work '' The True Word'' (also ''Account'', ''Doctrine'' or ''Discourse''; Greek: )Hoffmann p.29 survives exclusively via quotati ...

, one of its foremost early critics. Origen produced the , the first critical edition of the Hebrew Bible, which contained the original Hebrew text, four different Greek translations, and a Greek transliteration of the Hebrew, all written in columns, side by side.

He wrote hundreds of sermons covering almost the entire Bible

The Bible is a collection of religious texts that are central to Christianity and Judaism, and esteemed in other Abrahamic religions such as Islam. The Bible is an anthology (a compilation of texts of a variety of forms) originally writt ...

, interpreting many passages as allegorical. Origen taught that, before the creation of the material universe, God had created the souls of all intelligent beings. These souls, at first fully devoted to God, fell away from him and were given physical bodies. Origen was the first to propose the ransom theory of atonement

The ransom theory of atonement is a theory in Christian theology as to how the process of Atonement in Christianity had happened. It therefore accounts for the meaning and effect of the death of Jesus Christ. It is one of a number of historical ...

in its fully developed form, and he also significantly contributed to the development of the concept of the Trinity

The Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the Christian doctrine concerning the nature of God, which defines one God existing in three, , consubstantial divine persons: God the Father, God the Son (Jesus Christ) and God the Holy Spirit, thr ...

. Origen hoped that all people might eventually attain salvation but was always careful to maintain that this was only speculation. He defended free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

and advocated Christian pacifism

Christian pacifism is the Christian theology, theological and Christian ethics, ethical position according to which pacifism and non-violence have both a scriptural and rational basis for Christians, and affirms that any form of violence is inco ...

.

Origen is considered by some Christian groups to be a Church Father

The Church Fathers, Early Church Fathers, Christian Fathers, or Fathers of the Church were ancient and influential Christian theologians and writers who established the intellectual and doctrinal foundations of Christianity. The historical per ...

. He is widely regarded as one of the most influential Christian theologians. His teachings were especially influential in the east, with Athanasius of Alexandria

Athanasius I of Alexandria ( – 2 May 373), also called Athanasius the Great, Athanasius the Confessor, or, among Coptic Christians, Athanasius the Apostolic, was a Christian theologian and the 20th patriarch of Alexandria (as Athanasius ...

and the three Cappadocian Fathers

The Cappadocian Fathers, also traditionally known as the Three Cappadocians, were a trio of Byzantine Christian prelates, theologians and monks who helped shape both early Christianity and the monastic tradition. Basil the Great (330–379) wa ...

being among his most devoted followers. Argument over the orthodoxy of Origen's teachings spawned the First Origenist Crisis in the late fourth century, in which he was attacked by Epiphanius of Salamis

Epiphanius of Salamis (; – 403) was the bishop of Salamis, Cyprus, at the end of the Christianity in the 4th century, 4th century. He is considered a saint and a Church Father by the Eastern Orthodox Church, Eastern Orthodox, Catholic Churche ...

and Jerome

Jerome (; ; ; – 30 September 420), also known as Jerome of Stridon, was an early Christian presbyter, priest, Confessor of the Faith, confessor, theologian, translator, and historian; he is commonly known as Saint Jerome.

He is best known ...

but defended by Tyrannius Rufinus

Tyrannius Rufinus, also called Rufinus of Aquileia (; 344/345–411), was an early Christian monk, philosopher, historian, and theologian who worked to translate Greek patristic material, especially the work of Origen, into Latin.

Life

Rufinus ...

and John of Jerusalem. In 543, Emperor Justinian I

Justinian I (, ; 48214 November 565), also known as Justinian the Great, was Roman emperor from 527 to 565.

His reign was marked by the ambitious but only partly realized ''renovatio imperii'', or "restoration of the Empire". This ambition was ...

condemned him as a heretic and ordered all his writings to be burned. The Second Council of Constantinople

The Second Council of Constantinople is the fifth of the first seven ecumenical councils recognized by both the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Catholic Church. It is also recognized by the Old Catholics and others. Protestant opinions and re ...

in 553 may have anathema

The word anathema has two main meanings. One is to describe that something or someone is being hated or avoided. The other refers to a formal excommunication by a Christian denomination, church. These meanings come from the New Testament, where a ...

tized Origen, or it may have only condemned certain heretical teachings which claimed to be derived from Origen. The Church rejected his teachings on the pre-existence of souls.

Life

Early years

Almost all information about Origen's life comes from a lengthy biography of him in Book VI of the ''Ecclesiastical History

Church history or ecclesiastical history as an academic discipline studies the history of Christianity and the way the Christian Church has developed since its inception.

Henry Melvill Gwatkin defined church history as "the spiritual side of the ...

'' written by the Christian historian Eusebius

Eusebius of Caesarea (30 May AD 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilius, was a historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist from the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima. ...

(). Eusebius portrays Origen as the perfect Christian scholar and a literal saint. Eusebius, however, wrote this account almost fifty years after Origen's death and had access to few reliable sources on Origen's life, especially his early years. Anxious for more material about his hero, Eusebius recorded events based only on unreliable hearsay evidence. He frequently made speculative inferences about Origen based on the sources he had available. Nonetheless, scholars can reconstruct a general impression of Origen's historical life by sorting out the parts of Eusebius's account that are accurate from those that are inaccurate.

Origen was born in either 185 or 186 AD in Alexandria. Porphyry

Porphyry (; , ''Porphyrios'' "purple-clad") may refer to:

Geology

* Porphyry (geology), an igneous rock with large crystals in a fine-grained matrix, often purple, and prestigious Roman sculpture material

* Shoksha porphyry, quartzite of purple c ...

called him "a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor of all kno ...

, and educated in Greek literature

Greek literature () dates back from the ancient Greek literature, beginning in 800 BC, to the modern Greek literature of today.

Ancient Greek literature was written in an Ancient Greek dialect, literature ranges from the oldest surviving wri ...

". According to Eusebius, Origen's father was Leonides of Alexandria

Leonides of Alexandria (Greek: ) was a Greek early Christian martyr who lived in the second and early third centuries AD.

Biography

According to the Christian historian Eusebius, Leonides' son was the early Church father Origen.Eusebius Pamp ...

, a respected professor of literature and also a devout Christian who practised his religion openly (and later a martyr and saint with a feast day of April 22 in the Catholic church). Joseph Wilson Trigg deems the details of this report unreliable, but admits that Origen's father was certainly at least "a prosperous and thoroughly Hellenized bourgeois". According to John Anthony McGuckin, Origen's mother, whose name is unknown, may have been a member of the lower class who did not have the right of citizenship.

It is likely that, on account of his mother's status, Origen was not a Roman citizen. Origen's father taught him about literature and philosophy as well as the Bible and Christian doctrine. Eusebius states that Origen's father made him memorize passages of scripture daily. Trigg accepts this tradition as possibly genuine, given Origen's ability as an adult to recite extended passages of scripture at will. Eusebius also reports that Origen became so learned about the holy scriptures at an early age that his father was unable to answer his questions about them.

In 202, when Origen was "not yet seventeen", the Roman emperor Septimius Severus

Lucius Septimius Severus (; ; 11 April 145 – 4 February 211) was Roman emperor from 193 to 211. He was born in Leptis Magna (present-day Al-Khums, Libya) in the Roman province of Africa. As a young man he advanced through cursus honorum, the ...

ordered Roman citizens who openly practised Christianity to be executed. Origen's father Leonides was arrested and thrown in prison. Eusebius reports that Origen wanted to turn himself in to the authorities so that they would execute him as well, but his mother hid all his clothes and he was unable to go to the authorities since he refused to leave the house naked. According to McGuckin, even if Origen had turned himself in, it is unlikely that he would have been punished, since the emperor was only intent on executing Roman citizens. Origen's father was beheaded, and the state confiscated the family's entire property, leaving them impoverished. Origen was the eldest of nine children, and as his father's heir, it became his responsibility to provide for the whole family.

When he was eighteen, Origen was appointed as a catechist at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Many scholars have assumed that Origen became the head of the school, but according to McGuckin, this is highly improbable. It is more likely that he was given a paid teaching position, perhaps as a "relief effort" for his impoverished family. While employed at the school, he adopted the ascetic lifestyle of the Greek Sophist

A sophist () was a teacher in ancient Greece in the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. Sophists specialized in one or more subject areas, such as philosophy, rhetoric, music, athletics and mathematics. They taught ''arete'', "virtue" or "excellen ...

s. He spent the whole day teaching and would stay up late at night writing treatises and commentaries. He went barefoot and only owned one cloak. He did not drink alcohol and ate a simple diet and he often fasted for long periods. Although Eusebius goes to great lengths to portray Origen as one of the Christian monastics of his era, this portrayal is now generally recognized as anachronistic

An anachronism (from the Greek , 'against' and , 'time') is a chronological inconsistency in some arrangement, especially a juxtaposition of people, events, objects, language terms and customs from different time periods. The most common typ ...

.

According to Eusebius, as a young man, Origen was taken in by a wealthy Gnostic

Gnosticism (from Ancient Greek: , romanized: ''gnōstikós'', Koine Greek: �nostiˈkos 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems that coalesced in the late 1st century AD among early Christian sects. These diverse g ...

woman, who was also the patron of a very influential Gnostic theologian from Antioch

Antioch on the Orontes (; , ) "Antioch on Daphne"; or "Antioch the Great"; ; ; ; ; ; ; . was a Hellenistic Greek city founded by Seleucus I Nicator in 300 BC. One of the most important Greek cities of the Hellenistic period, it served as ...

, who frequently lectured in her home. Eusebius goes to great lengths to insist that, although Origen studied while in her home, he never once "prayed in common" with her or the Gnostic theologian. Later, Origen succeeded in converting a wealthy man named Ambrose

Ambrose of Milan (; 4 April 397), venerated as Saint Ambrose, was a theologian and statesman who served as Bishop of Milan from 374 to 397. He expressed himself prominently as a public figure, fiercely promoting Roman Christianity against Ari ...

from Valentinian Gnosticism

Valentinianism was one of the major Gnostic Christian movements. Founded by Valentinus ( CE – CE) in the 2nd century, its influence spread widely, not just within the Roman Empire but also from northwest Africa to Egypt through to Asia Minor an ...

to orthodox Christianity. Ambrose was so impressed by the young scholar that he gave Origen a house, a secretary, seven stenographers

Shorthand is an abbreviated symbolic writing method that increases speed and brevity of writing as compared to longhand, a more common method of writing a language. The process of writing in shorthand is called stenography, from the Greek ''st ...

, a crew of copyists and calligraphers, and paid for all of his writings to be published.

When he was in his early twenties, Origen sold the small library of Greek literary works that he had inherited from his father for a sum which netted him a daily income of four obols

The obol (, ''obolos'', also ὀβελός (''obelós''), ὀβελλός (''obellós''), ὀδελός (''odelós''). "nail, metal spit"; ) was a form of ancient Greek currency and weight.

Currency

Obols were used from early times. ...

.Eusebius, ''Historia Ecclesiastica'', VI.3.9 He used this money to continue his study of the Bible and of philosophy. Origen studied at numerous schools throughout Alexandria, including the Platonic Academy of Alexandria, where he was a student of Ammonius Saccas

Ammonius Saccas (; ; 175 AD243 AD) was a Hellenistic Platonist self-taught philosopher from Alexandria, generally regarded as the precursor of Neoplatonism or one of its founders. He is mainly known as the teacher of Plotinus, whom he taught f ...

. Eusebius claims that Origen studied under Clement of Alexandria

Titus Flavius Clemens, also known as Clement of Alexandria (; – ), was a Christian theology, Christian theologian and philosopher who taught at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Among his pupils were Origen and Alexander of Jerusalem. A ...

, but according to McGuckin, this is almost certainly a retrospective assumption based on the similarity of their teachings. Origen rarely mentions Clement in his writings, and when he does, it is usually to correct him.

Alleged self-castration

Eusebius claims that, as a young man, following a literal reading of Matthew 19:12, in which Jesus is presented as saying "there are eunuchs who have made themselves eunuch for the sake of the kingdom of heaven", Origen eithercastrated

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which a male loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy (excision of both testicles), while chemical castration uses pharmaceutical ...

himself or had someone else castrate him in order to ensure his reputation as a respectable tutor to young men and women. Eusebius further alleges that Origen privately told Demetrius, the bishop of Alexandria, about the castration and that Demetrius initially praised him for his devotion to God on account of it.

Origen, however, never mentions anything about having castrated himself in any of his surviving writings. In his explanation of this verse in his ''Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew'', written near the end of life, he strongly condemns any literal interpretation of Matthew 19:12, asserting that only an idiot would interpret the passage as advocating literal castration.

Since the beginning of the twentieth century, some scholars have questioned the historicity of Origen's self-castration, with many seeing it as a wholesale fabrication. Trigg states that Eusebius's account of Origen's self-castration is certainly true, because Eusebius, who was an ardent admirer of Origen, yet clearly describes the castration as an act of pure folly, would have had no motive to pass on a piece of information that might tarnish Origen's reputation unless it was "notorious and beyond question". Trigg sees Origen's condemnation of the literal interpretation of Matthew 19:12 as him "tacitly repudiating the literalistic reading he had acted on in his youth".

In sharp contrast, McGuckin dismisses Eusebius's story of Origen's self-castration as "hardly credible", seeing it as a deliberate attempt by Eusebius to distract from more serious questions regarding the orthodoxy of Origen's teachings. McGuckin also states: "We have no indication that the motive of castration for respectability was ever regarded as standard by a teacher of mixed-gender classes." He adds that Origen's female students (whom Eusebius lists by name) would have been accompanied by attendants at all times, meaning that Origen would have had no good reason to think that anyone would suspect him of impropriety.

Henry Chadwick argues that, while Eusebius's story may be true, it seems unlikely, given that Origen's exposition of Matthew 19:12 "strongly deplored any literal interpretation of the words". Instead, Chadwick suggests, "Perhaps Eusebius was uncritically reporting malicious gossip retailed by Origen's enemies, of whom there were many." However, many noted historians, such as Peter Brown and William Placher

William Carl Placher (1948–2008) was an American postliberal theologian. He was LaFollette Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Wabash College until his death in 2008. He was a leader at Wabash Avenue Presbyterian Church.

Publications ...

, continue to find no reason to conclude that the story is false.William Placher

William Carl Placher (1948–2008) was an American postliberal theologian. He was LaFollette Distinguished Professor in the Humanities at Wabash College until his death in 2008. He was a leader at Wabash Avenue Presbyterian Church.

Publications ...

, ''A History of Christian Theology: An Introduction'', (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983), p. 62. Placher theorizes that, if it is true, it may have followed an episode in which Origen received some raised eyebrows while privately tutoring a woman.

Travels and early writings

In his early twenties Origen became less interested in work as agrammarian

Grammarian may refer to:

* Alexandrine grammarians, philologists and textual scholars in Hellenistic Alexandria in the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE

* Biblical grammarians, scholars who study the Bible and the Hebrew language

* Grammarian (Greco-Roman ...

and more interested in operating as a rhetor-philosopher. He gave his job as a catechist to his younger colleague Heraclas. Meanwhile, Origen began to style himself as a "master of philosophy". Origen's new position as a self-styled Christian philosopher brought him into conflict with Demetrius, the bishop of Alexandria. Demetrius, a charismatic leader who ruled the Christian congregation of Alexandria with an iron fist, became the most direct promoter of the elevation in status of the bishop of Alexandria; before Demetrius, the bishop of Alexandria had merely been a priest who was elected to represent his fellows, but after Demetrius, the bishop was seen as clearly a rank higher than his fellow priests. By styling himself as an independent philosopher, Origen was reviving a role that had been prominent in earlier Christianity but which challenged the authority of the now-powerful bishop.

Meanwhile, Origen began composing his massive theological treatise ''On the First Principles

''On the First Principles'' (Greek: Περὶ Ἀρχῶν / ''Peri Archon''; Latin: ''De Principiis'') is a theological treatise by the Christian writer Origen. It was the first systematic exposition of Christian theology. It is thought to have b ...

'', a landmark book which systematically laid out the foundations of Christian theology for centuries to come. Origen also began travelling abroad to visit schools across the Mediterranean. In 212 he travelled to Rome – a major center of philosophy at the time. In Rome, Origen attended lectures by Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome ( , ; Romanized: , – ) was a Bishop of Rome and one of the most important second–third centuries Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communitie ...

and was influenced by his theology. In 213 or 214, the governor of the Province of Arabia

Arabia Petraea or Petrea, also known as Rome's Arabian Province or simply Arabia, was a frontier province of the Roman Empire beginning in the 2nd century. It consisted of the former Nabataean Kingdom in the southern Levant, the Sinai Peninsul ...

sent a message to the prefect of Egypt requesting him to send Origen to meet with him so that he could interview him and learn more about Christianity from its leading intellectual. Origen, escorted by official bodyguards, spent a short time in Arabia with the governor before returning to Alexandria.

In the autumn of 215, the Roman Emperor Caracalla

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (born Lucius Septimius Bassianus, 4 April 188 – 8 April 217), better known by his nickname Caracalla (; ), was Roman emperor from 198 to 217 AD, first serving as nominal co-emperor under his father and then r ...

visited Alexandria. During the visit, the students at the schools there protested and made fun of him for having murdered his brother Geta

Geta may refer to:

Places

*Geta (woreda), a woreda in Ethiopia's Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region

*Geta, Åland, a municipality in Finland

*Geta, Nepal, a town in Attariya Municipality, Kailali District, Seti Zone, Nepal

*Get� ...

(died 211). Caracalla, incensed, ordered his troops to ravage the city, execute the governor, and kill all the protesters. He also commanded them to expel all the teachers and intellectuals from the city. Origen fled Alexandria and traveled to the city of Caesarea Maritima

Caesarea () also Caesarea Maritima, Caesarea Palaestinae or Caesarea Stratonis, was an ancient and medieval port city on the coast of the eastern Mediterranean, and later a small fishing village. It was the capital of Judaea (Roman province), ...

in the Roman province of Palestine

Palestine, officially the State of Palestine, is a country in West Asia. Recognized by International recognition of Palestine, 147 of the UN's 193 member states, it encompasses the Israeli-occupied West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and th ...

, where the bishops Theoctistus of Caesarea and Alexander of Jerusalem

Alexander of Jerusalem (; died 251 AD) was a third century bishop who is venerated as a martyr and saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox churches, and the Roman Catholic Church. He died during the persecution of Emperor Decius.

...

became his devoted admirers and asked him to deliver discourses on the scriptures in their respective churches. This effectively allowed Origen to deliver sermons even though he was not formally ordained. While this was an unexpected phenomenon, especially given Origen's international fame as a teacher and philosopher, it infuriated Demetrius, who saw it as a direct undermining of his authority. Demetrius sent deacons from Alexandria to demand that the Palestinian hierarchs immediately return "his" catechist to Alexandria. He also issued a decree chastising the Palestinians for allowing a person who was not ordained to preach. The Palestinian bishops, in turn, issued their condemnation, accusing Demetrius of being jealous of Origen's fame and prestige.

Origen obeyed Demetrius's order and returned to Alexandria, bringing with him an antique scroll he had purchased at

Origen obeyed Demetrius's order and returned to Alexandria, bringing with him an antique scroll he had purchased at Jericho

Jericho ( ; , ) is a city in the West Bank, Palestine, and the capital of the Jericho Governorate. Jericho is located in the Jordan Valley, with the Jordan River to the east and Jerusalem to the west. It had a population of 20,907 in 2017.

F ...

containing the full text of the Hebrew Bible. The manuscript, which had purportedly been found "in a jar", became the source text for one of the two Hebrew columns in Origen's . Origen studied the Old Testament

The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

in great depth; Eusebius even claims that Origen learned Hebrew. Most modern scholars regard this claim as implausible, but they disagree over how much Origen knew about the language. H. Lietzmann concludes that Origen probably only knew the Hebrew alphabet and not much else, whereas R. P. C. Hanson and G. Bardy argue that Origen had a superficial understanding of the language but not enough to have composed the entire . A note in Origen's ''On the First Principles'' mentions an unknown "Hebrew master", but this was probably a consultant, not a teacher.

Origen also studied the entire

Origen also studied the entire New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

, but especially the epistles of the apostle Paul and the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John () is the fourth of the New Testament's four canonical Gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "Book of Signs, signs" culminating in the raising of Lazarus (foreshadowing the ...

, the writings which Origen regarded as the most important and authoritative. At Ambrose's request, Origen composed the first five books of his exhaustive ''Commentary on the Gospel of John'', He also wrote the first eight books of his ''Commentary on Genesis'', his ''Commentary on Psalms 1–25'', and his ''Commentary on Lamentations''. In addition to these commentaries, Origen also wrote two books on the resurrection of Jesus and ten books of ('Miscellanies'). It is likely that these works contained much theological speculation, which brought Origen into even greater conflict with Demetrius.

Conflict with Demetrius and removal to Caesarea

Origen repeatedly asked Demetrius toordain

Ordination is the process by which individuals are consecrated, that is, set apart and elevated from the laity class to the clergy, who are thus then authorized (usually by the denominational hierarchy composed of other clergy) to perform vari ...

him as a priest, but Demetrius continually refused. In around 231, Demetrius sent Origen on a mission to Athens. Along the way, Origen stopped in Caesarea, where he was warmly greeted by the bishops Theoctistus of Caesarea and Alexander of Jerusalem, who had become his close friends during his previous stay. While he was visiting Caesarea, Origen asked Theoctistus to ordain him as a priest. Theoctistus gladly complied. Upon learning of Origen's ordination, Demetrius was outraged and issued a condemnation declaring that Origen's ordination by a foreign bishop was an act of insubordination.

Eusebius reports that as a result of Demetrius's condemnations, Origen decided not to return to Alexandria and instead to take up permanent residence in Caesarea. John Anthony McGuckin, however, argues that Origen had probably already been planning to stay in Caesarea. The Palestinian bishops declared Origen the chief theologian of Caesarea. Firmilian

Firmilian (Greek: Φιρμιλιανός, Latin: Firmilianus, died c. 269 AD), Bishop of Caesarea Mazaca from , was a disciple of Origen. He had a contemporary reputation comparable to that of Dionysius of Alexandria or Cyprian, bishop of Carth ...

, the bishop of Caesarea Mazaca

Caesarea (Help:IPA/English, /ˌsɛzəˈriːə, ˌsɛsəˈriːə, ˌsiːzəˈriːə/; ), also known historically as Mazaca or Mazaka (, ), was an ancient city in what is now Kayseri, Turkey. In Hellenistic period, Hellenistic and Roman Empire, Rom ...

in Cappadocia

Cappadocia (; , from ) is a historical region in Central Anatolia region, Turkey. It is largely in the provinces of Nevşehir, Kayseri, Aksaray, Kırşehir, Sivas and Niğde. Today, the touristic Cappadocia Region is located in Nevşehir ...

, was such a devoted disciple of Origen that he begged him to come to Cappadocia and teach there.

Demetrius raised a storm of protests against the bishops of Palestine and the church synod

A synod () is a council of a Christian denomination, usually convened to decide an issue of doctrine, administration or application. The word '' synod'' comes from the Ancient Greek () ; the term is analogous with the Latin word . Originally, ...

in Rome. According to Eusebius, Demetrius published the allegation that Origen had secretly castrated himself, a capital offense under Roman law at the time and one which would have made Origen's ordination invalid, since eunuchs were forbidden from becoming priests. Demetrius also alleged that Origen had taught an extreme form of , which held that all beings, including even Satan himself, would eventually attain salvation. This allegation probably arose from a misunderstanding of Origen's argument during a debate with the Valentinian Gnostic teacher Candidus. Candidus had argued in favor of predestination

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby Go ...

by declaring that the Devil was beyond salvation. Origen had responded by arguing that, if the Devil is destined for eternal damnation, it was on account of his actions, which were the result of his own free will

Free will is generally understood as the capacity or ability of people to (a) choice, choose between different possible courses of Action (philosophy), action, (b) exercise control over their actions in a way that is necessary for moral respon ...

. Therefore, Origen had declared that Satan was only morally reprobate

Reprobation, in Christian theology, is a doctrine which teaches that a person can reject the gospel to a point where God in turn rejects them and curses their conscience. The English word ''reprobate'' is from the Latin root ''probare'' (''Engl ...

, not absolutely reprobate.

Demetrius died in 232, less than a year after Origen's departure from Alexandria. The accusations against Origen faded with the death of Demetrius, but they did not disappear entirely and they continued to haunt him for the rest of his career. Origen defended himself in his ''Letter to Friends in Alexandria'', in which he vehemently denied that he had ever taught that the Devil would attain salvation and insisted that the very notion of the Devil attaining salvation was simply ludicrous.

Work and teaching in Caesarea

During his early years in Caesarea, Origen's primary task was the establishment of a Christian School; Caesarea had long been seen as a center of learning for Jews and Hellenistic philosophers, but until Origen's arrival, it had lacked a Christian center of higher education. According to Eusebius, the school Origen founded was primarily targeted towards young pagans who had expressed interest in Christianity but were not yet ready to ask for baptism. The school therefore sought to explain Christian teachings throughMiddle Platonism

Middle Platonism is the modern name given to a stage in the development of Platonic philosophy, lasting from about 90 BC – when Antiochus of Ascalon rejected the scepticism of the new Academy – until the development of neoplatonis ...

. Origen started his curriculum by teaching his students classical Socratic reasoning. After they had mastered this, he taught them cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

and natural history

Natural history is a domain of inquiry involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment, leaning more towards observational than experimental methods of study. A person who studies natural history is cal ...

. Finally, once they had mastered all of these subjects, he taught them theology, which was the highest of all philosophies, the accumulation of everything they had previously learned.

With the establishment of the Caesarean school, Origen's reputation as a scholar and theologian reached its zenith and he became known throughout the Mediterranean world as a brilliant intellectual. The hierarchs of the Palestinian and Arabian church synods regarded Origen as the ultimate expert on all matters dealing with theology. While teaching in Caesarea, Origen resumed work on his ''Commentary on John'', composing at least books six through ten. In the first of these books, Origen compares himself to "an Israelite who has escaped the perverse persecution of the Egyptians". Origen also wrote the treatise ''On Prayer'' at the request of his friend Ambrose and Tatiana (referred to as the "sister" of Ambrose), in which he analyzes the different types of prayers described in the Bible and offers a detailed exegesis on the Lord's Prayer

The Lord's Prayer, also known by its incipit Our Father (, ), is a central Christian prayer attributed to Jesus. It contains petitions to God focused on God’s holiness, will, and kingdom, as well as human needs, with variations across manusc ...

.

Pagans also took a fascination with Origen. The

Pagans also took a fascination with Origen. The Neoplatonist

Neoplatonism is a version of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a series of thinkers. Among the common id ...

philosopher Porphyry

Porphyry (; , ''Porphyrios'' "purple-clad") may refer to:

Geology

* Porphyry (geology), an igneous rock with large crystals in a fine-grained matrix, often purple, and prestigious Roman sculpture material

* Shoksha porphyry, quartzite of purple c ...

heard of Origen's fame and traveled to Caesarea to listen to his lectures. Porphyry recounts that Origen had extensively studied the teachings of Pythagoras

Pythagoras of Samos (; BC) was an ancient Ionian Greek philosopher, polymath, and the eponymous founder of Pythagoreanism. His political and religious teachings were well known in Magna Graecia and influenced the philosophies of P ...

, Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

, and Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, but also those of important Middle Platonists, Neopythagoreans, and Stoics

Stoicism is a school of Hellenistic philosophy that flourished in ancient Greece and Rome. The Stoics believed that the universe operated according to reason, ''i.e.'' by a God which is immersed in nature itself. Of all the schools of ancient ...

, including Numenius of Apamea

Numenius of Apamea (, ''Noumēnios ho ex Apameias''; ) was a Greek philosopher, who lived in Rome, and flourished during the latter half of the 2nd century AD. He was a Neopythagorean and forerunner of the Neoplatonists.

Philosophy

Statements ...

, Chronius, Apollophanes

Apollophanes Soter (Greek: ; epithet means "the Saviour"; reigned c. 35 – 25 BCE) was an Indo-Greek king in the area of eastern and central Punjab in modern India and Pakistan.

Rule

Little is known about him, except for some of his remaining ...

, Longinus

Longinus (Greek: Λογγίνος) is the name of the Roman soldier who pierced the side of Jesus with a lance, who in apostolic and some modern Christian traditions is described as a convert to Christianity. His name first appeared in the apoc ...

, Moderatus of Gades

Moderatus of Gades () was a Greek philosopher of the Neopythagorean school, who lived in the 1st century AD. He was a contemporary of Apollonius of Tyana. He wrote a great work on the doctrines of the Pythagoreans, and tried to show that the succ ...

, Nicomachus

Nicomachus of Gerasa (; ) was an Ancient Greek Neopythagorean philosopher from Gerasa, in the Roman province of Syria (now Jerash, Jordan). Like many Pythagoreans, Nicomachus wrote about the mystical properties of numbers, best known for his ...

, Chaeremon, and Cornutus. Nonetheless, Porphyry accused Origen of having betrayed true philosophy by subjugating its insights to the exegesis of the Christian scriptures. Eusebius reports that Origen was summoned from Caesarea to Antioch at the behest of Julia Avita Mamaea

Julia Avita Mamaea or Julia Mamaea (14 or 29 August around 182 – March 21/22 235) was a Syrian noble woman and member of the Severan dynasty. She was the mother of Roman emperor Alexander Severus and remained one of his chief advisors thr ...

, the mother of Roman Emperor Severus Alexander

Marcus Aurelius Severus Alexander (1 October 208 – March 235), also known as Alexander Severus, was Roman emperor from 222 until 235. He was the last emperor from the Severan dynasty. Alexander took power in 222, when he succeeded his slain c ...

, "to discuss Christian philosophy and doctrine with her".

In 235, approximately three years after Origen began teaching in Caesarea, Alexander Severus, who had been tolerant towards Christians, was murdered and Emperor Maximinus Thrax

Gaius Julius Verus Maximinus "Thrax" () was a Roman emperor from 235 to 238. Born of Thracian origin – given the nickname ''Thrax'' ("the Thracian") – he rose up through the military ranks, ultimately holding high command in the army of th ...

instigated a purge of all those who had supported his predecessor. His pogrom

A pogrom is a violent riot incited with the aim of Massacre, massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe late 19th- and early 20th-century Anti-Jewis ...

s targeted Christian leaders and, in Rome, Pope Pontianus

Pope Pontian (; died October 235) was the bishop of Rome from 21 July 230 to 28 September 235.Kirsch, Johann Peter (1911). "Pope St. Pontian" in ''The Catholic Encyclopedia''. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company. In 235, during the persecu ...

and Hippolytus of Rome

Hippolytus of Rome ( , ; Romanized: , – ) was a Bishop of Rome and one of the most important second–third centuries Christian theologians, whose provenance, identity and corpus remain elusive to scholars and historians. Suggested communitie ...

were both sent into exile. Origen knew that he was in danger and went into hiding in the home of a faithful Christian woman named Juliana the Virgin, who had been a student of the Ebionite leader Symmachus. Origen's close friend and longtime patron Ambrose was arrested in Nicomedia

Nicomedia (; , ''Nikomedeia''; modern İzmit) was an ancient Greece, ancient Greek city located in what is now Turkey. In 286, Nicomedia became the eastern and most senior capital city of the Roman Empire (chosen by the emperor Diocletian who rul ...

, and Protoctetes, the leading priest in Caesarea, was also arrested. In their honor, Origen composed his treatise '' Exhortation to Martyrdom'', which is now regarded as one of the greatest classics of Christian resistance literature. After coming out of hiding following Maximinus's death, Origen founded a school of which Gregory Thaumaturgus

Gregory Thaumaturgus or Gregory the Miracle-Worker (, ; ; ), also known as Gregory of Neocaesarea, was a Christian bishop of the 3rd century. He has been canonized as a saint in the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

Biography

Gregory was born arou ...

, later bishop of Pontus, was one of the pupils. He preached regularly on Wednesdays and Fridays, and later daily.

Later life

Sometime between 238 and 244, Origen visited Athens, where he completed his ''Commentary on theBook of Ezekiel

The Book of Ezekiel is the third of the Nevi'im#Latter Prophets, Latter Prophets in the Hebrew Bible, Tanakh (Hebrew Bible) and one of the Major Prophets, major prophetic books in the Christian Bible, where it follows Book of Isaiah, Isaiah and ...

'' and began writing his ''Commentary on the Song of Songs

The Song of Songs (), also called the Canticle of Canticles or the Song of Solomon, is a Biblical poetry, biblical poem, one of the five ("scrolls") in the ('writings'), the last section of the Tanakh. Unlike other books in the Hebrew Bible, i ...

''. After visiting Athens, he visited Ambrose in Nicomedia. According to Porphyry, Origen also travelled to Rome or Antioch, where he met Plotinus

Plotinus (; , ''Plōtînos''; – 270 CE) was a Greek Platonist philosopher, born and raised in Roman Egypt. Plotinus is regarded by modern scholarship as the founder of Neoplatonism. His teacher was the self-taught philosopher Ammonius ...

, the founder of Neoplatonism. The Christians of the eastern Mediterranean continued to revere Origen as the most orthodox of all theologians, and when the Palestinian hierarchs learned that Beryllus, the bishop of Bostra and one of the most energetic Christian leaders of the time, had been preaching adoptionism

Adoptionism, also called dynamic monarchianism, is an early Christian nontrinitarian theological doctrine, subsequently revived in various forms, which holds that Jesus was adopted as the Son of God at his baptism, his resurrection, or his ...

(the belief that Jesus was born human and only became divine after his baptism), they sent Origen to convert him to orthodoxy. Origen engaged Beryllus in a public disputation, which went so successfully that Beryllus promised only to teach Origen's theology from then on. On another occasion, a Christian leader in Arabia named Heracleides began teaching that the soul was mortal and that it perished with the body. Origen refuted these teachings, arguing that the soul is immortal and can never die.

In , the Plague of Cyprian

The Plague of Cyprian was a pandemic which afflicted the Roman Empire from about AD 249 to 262, or 251/2 to 270. The plague is thought to have caused widespread manpower shortages for food production and the Roman army, severely weakening the em ...

broke out. In 250, Emperor Decius

Gaius Messius Quintus Trajanus Decius ( 201June 251), known as Trajan Decius or simply Decius (), was Roman emperor from 249 to 251.

A distinguished politician during the reign of Philip the Arab, Decius was proclaimed emperor by his troops a ...

, believing that the plague was caused by Christians' failure to recognise him as divine, issued a decree for Christians to be persecuted. This time Origen did not escape. Eusebius recounts how Origen suffered "bodily tortures and torments under the iron collar and in the dungeon; and how for many days with his feet stretched four spaces in the stocks". The governor of Caesarea gave very specific orders that Origen was not to be killed until he had publicly renounced his faith in Christ. Origen endured two years of imprisonment and torture, but obstinately refused to renounce his faith. In June 251, Decius was killed fighting the Goths in the Battle of Abritus

The Battle of Abritus also known as the Battle of Forum Terebronii occurred near Abritus (modern Razgrad) in the Roman province of Moesia Inferior in the summer of 251. It was fought between the Romans and a federation of Gothic and Scythian t ...

, and Origen was released from prison. Nonetheless, Origen's health was broken by the physical tortures enacted on him, and he died less than a year later at the age of sixty-nine. A later legend, recounted by Jerome and numerous itineraries, places his death and burial at Tyre, but little value can be attached to this.

Works

Exegetical writings

Origen was an extremely prolific writer. According to Epiphanius, he wrote a grand total of roughly 6,000 works over the course of his lifetime. Most scholars agree that this estimate is probably somewhat exaggerated. According to Jerome, Eusebius listed the titles of just under 2,000 treatises written by Origen in his lost ''Life of Pamphilus''. Jerome compiled an abbreviated list of Origen's major treatises, itemizing 800 different titles. By far the most important work of Origen on textual criticism was the ('Sixfold'), a massive comparative study of various translations of the Old Testament in six columns:Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

, Hebrew in Greek characters, the Septuagint

The Septuagint ( ), sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy (), and abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Biblical Hebrew. The full Greek ...

, and the Greek translations of Theodotion

Theodotion (; , ''gen''.: Θεοδοτίωνος; died c. 200) was a Hellenistic Jewish scholar, perhaps working in Ephesus, who in c. A.D. 150 translated the Hebrew Bible into Greek.

History

Whether he was revising the Septuagint, or was wor ...

(a Jewish scholar from 180 AD), Aquila of Sinope

Aquila (Hebrew language, Hebrew: עֲקִילַס ''ʿăqīlas'', Floruit, fl. 130 Common Era, CE) of Sinope (modern-day Sinop, Turkey; ) was a translator of the Hebrew Bible into Greek language, Greek, a proselyte, and disciple of Rabbi Akiva.

R ...

(another Jewish scholar from 117–138), and Symmachus (an Ebionite scholar from 193–211). Origen was the first Christian scholar to introduce critical markers to a Biblical text. He marked the Septuagint column of the ''Hexapla'' using signs adapted from those used by the textual critics of the Great Library of Alexandria

The Great Library of Alexandria in Alexandria, Egypt, was one of the largest and most significant List of libraries in the ancient world, libraries of the ancient world. The library was part of a larger research institution called the Mousei ...

: a passage found in the Septuagint that was not found in the Hebrew text would be marked with an obelus

An obelus (plural: obeluses or obeli) is a term in codicology and latterly in typography that refers to a historical annotation mark which has resolved to three modern meanings:

* Division sign

* Dagger

* Commercial minus sign (limited g ...

(÷) and a passage that was found in other Greek translations, but not in the Septuagint, would be marked with an asterisk

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a Typography, typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a star (heraldry), heraldic star.

Computer scientists and Mathematici ...

(*).

Constantine the Great

Constantine I (27 February 27222 May 337), also known as Constantine the Great, was a Roman emperor from AD 306 to 337 and the first Roman emperor to convert to Christianity. He played a Constantine the Great and Christianity, pivotal ro ...

ordered fifty complete copies of the Bible to be transcribed and disseminated across the empire, Eusebius used the as the master copy for the Old Testament. Although the original has been lost, the text of it has survived in numerous fragments and a more-or-less complete Syriac translation of the Greek column, made by the seventh-century bishop Paul of Tella, has also survived. For some sections of the , Origen included additional columns containing other Greek translations; for the Book of Psalms, he included no less than eight Greek translations, making this section known as ('Ninefold'). Origen also produced the ('Fourfold'), a smaller, abridged version of the containing only the four Greek translations and not the original Hebrew text.

According to Jerome's ''Epistle'' 33, Origen wrote extensive on the books of Exodus

Exodus or the Exodus may refer to:

Religion

* Book of Exodus, second book of the Hebrew Torah and the Christian Bible

* The Exodus, the biblical story of the migration of the ancient Israelites from Egypt into Canaan

Historical events

* Ex ...

, Leviticus, Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "Yahweh is salvation"; also known as Isaias or Esaias from ) was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

The text of the Book of Isaiah refers to Isaiah as "the prophet" ...

, Psalms 1–15, Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes ( ) is one of the Ketuvim ('Writings') of the Hebrew Bible and part of the Wisdom literature of the Christian Old Testament. The title commonly used in English is a Latin transliteration of the Greek translation of the Hebrew word ...

, and the Gospel of John. None of these have survived intact, but parts of them were incorporated into the , a collection of excerpts from major works of Biblical commentary written by the Church Fathers. Other fragments of the are preserved in Origen's and in Pamphilus of Caesarea

Saint Pamphilus (; latter half of the 3rd century – February 16, 309 AD), was a priest of Caesarea and chief among the biblical scholars of his generation. He was the friend and teacher of Eusebius of Caesarea, who recorded details of his ...

's apology for Origen. The were of a similar character, and the margin of , 184, contains citations from this work on Romans 9:23; I Corinthians 6:14, 7:31, 34, 9:20–21, 10:9, besides a few other fragments. Origen composed homilies covering almost the entire Bible. There are 205, and possibly 279, homilies of Origen that are extant either in Greek or in Latin translations.

The homilies preserved are on Genesis (16), Exodus (13), Leviticus (16), Numbers (28), Joshua (26), Judges (9), I Sam. (2), Psalms 36–38 (9), Canticles (2), Isaiah (9), Jeremiah (7 Greek, 2 Latin, 12 Greek and Latin), Ezekiel (14), and Luke (39). The homilies were preached in the church at Caesarea, with the exception of the two on 1 Samuel which were delivered in Jerusalem. Nautin has argued that they were all preached in a three-year liturgical cycle some time between 238 and 244, preceding the ''Commentary on the Song of Songs'', where Origen refers to homilies on Judges, Exodus, Numbers, and a work on Leviticus. On June 11, 2012, the

The homilies preserved are on Genesis (16), Exodus (13), Leviticus (16), Numbers (28), Joshua (26), Judges (9), I Sam. (2), Psalms 36–38 (9), Canticles (2), Isaiah (9), Jeremiah (7 Greek, 2 Latin, 12 Greek and Latin), Ezekiel (14), and Luke (39). The homilies were preached in the church at Caesarea, with the exception of the two on 1 Samuel which were delivered in Jerusalem. Nautin has argued that they were all preached in a three-year liturgical cycle some time between 238 and 244, preceding the ''Commentary on the Song of Songs'', where Origen refers to homilies on Judges, Exodus, Numbers, and a work on Leviticus. On June 11, 2012, the Bavarian State Library

The Bavarian State Library (, abbreviated BSB, called ''Bibliotheca Regia Monacensis'' before 1919) in Munich is the central " Landesbibliothek", i. e. the state library of the Free State of Bavaria, the biggest universal and research libra ...

announced that the Italian philologist Marina Molin Pradel had discovered twenty-nine previously unknown homilies by Origen in a twelfth-century Byzantine manuscript from their collection. Prof. Lorenzo Perrone of Bologna University and other experts confirmed the authenticity of the homilies. The texts of these manuscripts can be found online.

Origen is the main source of information on the use of the texts that were later officially canonized as the New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

.C. G. Bateman, Origen's Role in the Formation of the New Testament Canon, 2010archive

/ref> The information used to create the late-fourth-century

Easter Letter The Festal Letters or Easter Letters are a series of annual letters by which the Bishops of Alexandria, in conformity with a decision of the First Council of Nicaea, announced the date on which Easter was to be celebrated. The council chose Alexandr ...

, which declared accepted Christian writings, was probably based on the lists given in Eusebius's ''Ecclesiastical History'' HE 3:25 and 6:25, which were both primarily based on information provided by Origen. Origen accepted the authenticity of the epistles of 1 John

The First Epistle of John is the first of the Johannine epistles of the New Testament, and the fourth of the catholic epistles. There is no scholarly consensus as to the authorship of the Johannine works. The author of the First Epistle is so ...

, 1 Peter

The First Epistle of Peter is a book of the New Testament. The author presents himself as Peter the Apostle. The ending of the letter includes a statement that implies that it was written from "Babylon", which may be a reference to Rome. The ...

, and Jude without question and accepted the Epistle of James

The Epistle of James is a Catholic epistles, general epistle and one of the 21 epistles (didactic letters) in the New Testament. It was written originally in Koine Greek. The epistle aims to reach a wide Jewish audience. It survives in manusc ...

as authentic with only slight hesitation. He also refers to 2 John

The Second Epistle of John is a book of the New Testament attributed to John the Evangelist, traditionally thought to be the author of the other two epistles of John, and the Gospel of John (though this is disputed). Most modern scholars beli ...

, 3 John

The Third Epistle of John is the third-to-last book of the New Testament and the Christian Bible as a whole, and attributed to John the Evangelist, traditionally thought to be the author of the Gospel of John and the other two epistles of John ...

, and 2 Peter

2 Peter, also known as the Second Epistle of Peter and abbreviated as 2 Pet., is an epistle of the New Testament written in Koine Greek. It identifies the author as "Simon Peter" (in some translations, 'Simeon' or 'Shimon'), a bondservant and ...

but notes that all three were suspected to be forgeries. Origen may have also considered other writings to be "inspired" that were rejected by later authors, including the Epistle of Barnabas

The Epistle of Barnabas () is an early Christian Greek epistle written between AD 70 and AD 135. The complete text is preserved in the 4th-century Codex Sinaiticus, where it appears at the end of the New Testament, following the Book of Revelati ...

, Shepherd of Hermas

A shepherd is a person who tends, herds, feeds, or guards flocks of sheep. Shepherding is one of the world's oldest occupations; it exists in many parts of the globe, and it is an important part of pastoralist animal husbandry.

Because t ...

, and 1 Clement.McGuckin, John A. "Origen as Literary Critic in the Alexandrian Tradition." 121–37 in vol. 1 of 'Origeniana octava: Origen and the Alexandrian Tradition.' Papers of the 8th International Origen Congress (Pisa, 27–31 August 2001). Edited by L. Perrone. Bibliotheca Ephemeridum theologicarum Lovaniensium 164. 2 vols. Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2003. "Origen is not the originator of the idea of biblical canon, but he certainly gives the philosophical and literary–interpretative underpinnings for the whole notion."

Extant commentaries

Mouseion

The Mouseion of Alexandria (; ), which arguably included the Library of Alexandria, was an institution said to have been founded by Ptolemy I Soter and his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Originally, the word ''mouseion'' meant any place that was ...

in Alexandria to the Christian scriptures. The commentaries also display Origen's impressive encyclopedic knowledge of various subjects and his ability to cross-reference specific words, listing every place in which a word appears in the scriptures along with all the word's known meanings, a feat made all the more impressive by the fact that he did this in a time when Bible concordance

A Bible concordance is a Concordance (publishing), concordance, or verbal index, to the Bible. A simple form lists Biblical words alphabetically, with indications to enable the inquirer to find the passages of the Bible where the words occur.

Con ...