olive tree on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

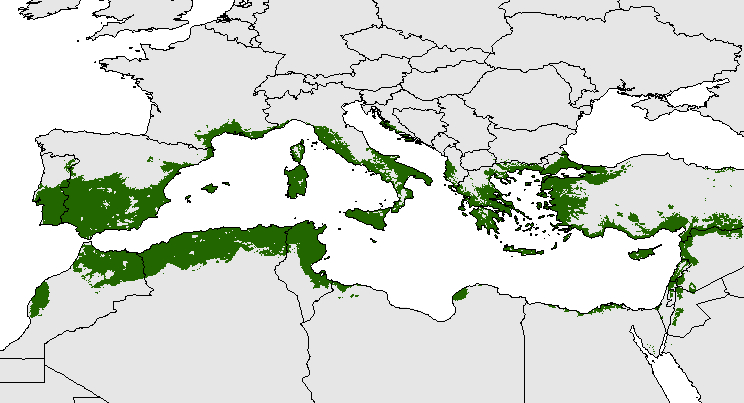

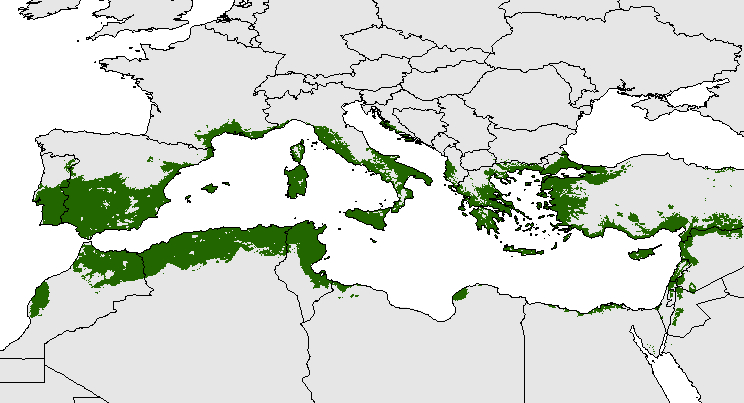

The olive,

botanical name

A botanical name is a formal scientific name conforming to the ''International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants'' (ICN) and, if it concerns a plant cultigen, the additional cultivar or cultivar group, Group epithets must conform t ...

''Olea europaea'' ("European olive"), is a species

A species () is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate sexes or mating types can produce fertile offspring, typically by sexual reproduction. It is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), ...

of subtropical

The subtropical zones or subtropics are geographical zone, geographical and Köppen climate classification, climate zones immediately to the Northern Hemisphere, north and Southern Hemisphere, south of the tropics. Geographically part of the Ge ...

evergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant which has Leaf, foliage that remains green and functional throughout the year. This contrasts with deciduous plants, which lose their foliage completely during the winter or dry season. Consisting of many diffe ...

tree

In botany, a tree is a perennial plant with an elongated stem, or trunk, usually supporting branches and leaves. In some usages, the definition of a tree may be narrower, e.g., including only woody plants with secondary growth, only ...

in the family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

Oleaceae

Oleaceae, also known as the olive family or sometimes the lilac family, is a taxonomic family of flowering shrubs, trees, and a few lianas in the order Lamiales. It presently comprises 28 genera, one of which is recently extinct.Peter S. Gree ...

. Originating in Asia Minor

Anatolia (), also known as Asia Minor, is a peninsula in West Asia that makes up the majority of the land area of Turkey. It is the westernmost protrusion of Asia and is geographically bounded by the Mediterranean Sea to the south, the Aegean ...

, it is abundant throughout the Mediterranean Basin, with wild subspecies

In Taxonomy (biology), biological classification, subspecies (: subspecies) is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (Morphology (biology), morpholog ...

in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent after Asia. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 20% of Earth's land area and 6% of its total surfac ...

and western Asia

Asia ( , ) is the largest continent in the world by both land area and population. It covers an area of more than 44 million square kilometres, about 30% of Earth's total land area and 8% of Earth's total surface area. The continent, which ...

; modern cultivars

A cultivar is a kind of cultivated plant that people have selected for desired traits and which retains those traits when propagated. Methods used to propagate cultivars include division, root and stem cuttings, offsets, grafting, tissue cult ...

are traced primarily to the Near East

The Near East () is a transcontinental region around the Eastern Mediterranean encompassing the historical Fertile Crescent, the Levant, Anatolia, Egypt, Mesopotamia, and coastal areas of the Arabian Peninsula. The term was invented in the 20th ...

, Aegean Sea

The Aegean Sea is an elongated embayment of the Mediterranean Sea between Europe and Asia. It is located between the Balkans and Anatolia, and covers an area of some . In the north, the Aegean is connected to the Marmara Sea, which in turn con ...

, and Strait of Gibraltar

The Strait of Gibraltar is a narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Europe from Africa.

The two continents are separated by 7.7 nautical miles (14.2 kilometers, 8.9 miles) at its narrowest point. Fe ...

. The olive is the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

for its genus

Genus (; : genera ) is a taxonomic rank above species and below family (taxonomy), family as used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In bino ...

, ''Olea

''Olea'' ( ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Oleaceae. It includes 12 species native to warm temperate and tropical regions of the Middle East, southern Europe, Africa, southern Asia, and Australasia. They are evergreen trees and s ...

'', and lends its name to the Oleaceae

Oleaceae, also known as the olive family or sometimes the lilac family, is a taxonomic family of flowering shrubs, trees, and a few lianas in the order Lamiales. It presently comprises 28 genera, one of which is recently extinct.Peter S. Gree ...

plant family, which includes species such as lilac, jasmine

Jasmine (botanical name: ''Jasminum'', pronounced ) is a genus of shrubs and vines in the olive family of Oleaceae. It contains around 200 species native to tropical and warm temperate regions of Eurasia, Africa, and Oceania. Jasmines are wid ...

, forsythia

''Forsythia'' , is a genus of flowering plants in the olive family Oleaceae. There are about 11 species, mostly native to Eastern Asia, but one native to Southeastern Europe. ''Forsythia'' – also one of the plant's common names – is named ...

, and ash. The olive fruit is classed botanically as a drupe

In botany, a drupe (or stone fruit) is a type of fruit in which an outer fleshy part (exocarp, or skin, and mesocarp, or flesh) surrounds a single shell (the ''pip'' (UK), ''pit'' (US), ''stone'', or ''pyrena'') of hardened endocarp with a seed ...

, similar to the cherry

A cherry is the fruit of many plants of the genus ''Prunus'', and is a fleshy drupe (stone fruit).

Commercial cherries are obtained from cultivars of several species, such as the sweet '' Prunus avium'' and the sour '' Prunus cerasus''. The na ...

or peach

The peach (''Prunus persica'') is a deciduous tree first domesticated and Agriculture, cultivated in China. It bears edible juicy fruits with various characteristics, most called peaches and the glossy-skinned, non-fuzzy varieties called necta ...

. The term oil—now used to describe any viscous

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for example, syrup h ...

water-insoluble liquid

Liquid is a state of matter with a definite volume but no fixed shape. Liquids adapt to the shape of their container and are nearly incompressible, maintaining their volume even under pressure. The density of a liquid is usually close to th ...

—was virtually synonymous with olive oil

Olive oil is a vegetable oil obtained by pressing whole olives (the fruit of ''Olea europaea'', a traditional Tree fruit, tree crop of the Mediterranean Basin) and extracting the oil.

It is commonly used in cooking for frying foods, as a cond ...

, the liquid fat made from olives.

The olive has deep historical, economic, and cultural significance in the Mediterranean; Georges Duhamel remarked that the "Mediterranean ends where the olive tree no longer grows". Among the oldest fruit trees domesticated by humans, the olive was first cultivated in the Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a loosely delimited region comprising the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean Sea, and well as the adjoining land—often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea. It includes the southern half of Turkey ...

between 8,000 and 6,000 years ago, most likely in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

. It gradually disseminated throughout the Mediterranean via trade and human migration starting in the 16th century BC; the olive took root in Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

around 3500 BC and reached Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

by about 1050 BC. Olive cultivation was vital to the growth and prosperity of various Mediterranean civilizations, from the Minoans and Myceneans of the Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

to the Greeks

Greeks or Hellenes (; , ) are an ethnic group and nation native to Greece, Greek Cypriots, Cyprus, Greeks in Albania, southern Albania, Greeks in Turkey#History, Anatolia, parts of Greeks in Italy, Italy and Egyptian Greeks, Egypt, and to a l ...

and Romans of classical antiquity

Classical antiquity, also known as the classical era, classical period, classical age, or simply antiquity, is the period of cultural History of Europe, European history between the 8th century BC and the 5th century AD comprising the inter ...

.

The olive has long been prized throughout the Mediterranean for its myriad uses and properties. Aside from its edible fruit, the extracted oil was used for lamp fuel, personal grooming, cosmetics, soap, lubrication, and medicine; its wood was sometimes used for construction. Owing to its utility, resilience, and longevity—which can allegedly reach thousands of years—the olive also held symbolic and spiritual importance in various cultures; it was used in religious rituals, funerary processions, and public ceremonies, from the ancient Olympic games

The ancient Olympic Games (, ''ta Olympia''.), or the ancient Olympics, were a series of Athletics (sport), athletic competitions among representatives of polis, city-states and one of the Panhellenic Games of ancient Greece. They were held at ...

to the coronation

A coronation ceremony marks the formal investiture of a monarch with regal power using a crown. In addition to the crowning, this ceremony may include the presentation of other items of regalia, and other rituals such as the taking of special v ...

of Israelite kings. Ancient Greeks regarded the olive tree as sacred and a symbol of peace, prosperity, and wisdom—associations that persist to this day. The olive is a core ingredient in traditional Middle Eastern

The Middle East (term originally coined in English language) is a geopolitical region encompassing the Arabian Peninsula, the Levant, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, and Iraq.

The term came into widespread usage by the United Kingdom and western Eur ...

and Mediterranean cuisine

Mediterranean cuisine is the food and methods of preparation used by the people of the Mediterranean basin. The idea of a Mediterranean cuisine originates with the cookery writer Elizabeth David's book, ''A Book of Mediterranean Food'' (1950), ...

s, particularly in the form of olive oil, and a defining feature of local landscapes, commerce, and folk traditions.

The olive is cultivated in all countries of the Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea ( ) is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the east by the Levant in West Asia, on the north by Anatolia in West Asia and Southern ...

, as well as in Australia, New Zealand, the Americas, and South Africa. Spain, Italy, and Greece lead the world in commercial olive production; other major producers are Turkey, Tunisia, Syria, Morocco, Algeria, and Portugal. There are thousands of cultivars of the olive tree, which may be used primarily for oil, eating, or both; some varieties are grown as ornamental sterile shrubs

A shrub or bush is a small to medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from trees by their multiple ...

, known as ''Olea europaea'' ''Montra'', ''dwarf olive'', or ''little olive''. Approximately 80% of all harvested olives are processed into oil, while about 20% are used for consumption, generally referred to as "table olives".

Etymology

The word ''olive'' derives fromLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

' 'olive fruit; olive tree', possibly through Etruscan 𐌀𐌅𐌉𐌄𐌋𐌄 (''eleiva'') from the archaic Proto-Greek

The Proto-Greek language (also known as Proto-Hellenic) is the Indo-European language which was the last common ancestor of all varieties of Greek, including Mycenaean Greek, the subsequent ancient Greek dialects (i.e., Attic, Ionic, Ae ...

form *ἐλαίϝα (*''elaíwa'') ( Classic Greek ' 'olive fruit; olive tree'). The word ''oil'' originally meant 'olive oil', from ', (' 'olive oil'). The word for 'oil' in multiple other languages also ultimately derives from the name of this tree and its fruit. The oldest attested forms of the Greek words are Mycenaean , ', and , ' or , ', written in the Linear B

Linear B is a syllabary, syllabic script that was used for writing in Mycenaean Greek, the earliest Attested language, attested form of the Greek language. The script predates the Greek alphabet by several centuries, the earliest known examp ...

syllabic script.

Description

The olive tree, ''Olea europaea'', is anevergreen

In botany, an evergreen is a plant which has Leaf, foliage that remains green and functional throughout the year. This contrasts with deciduous plants, which lose their foliage completely during the winter or dry season. Consisting of many diffe ...

tree or shrub native to Mediterranean Europe, Asia, and Africa. It is short and squat and rarely exceeds in height. Pisciottana—a unique variety comprising 40,000 trees found only in the area around Pisciotta

Pisciotta is an Italian town and communes of Italy, commune in the province of Salerno, region of Campania.

History

According to legend, Troy, Trojans escaping from the fire and the destruction of their city, Troy, founded Siris, Magna Graecia, ...

in the Campania

Campania is an administrative Regions of Italy, region of Italy located in Southern Italy; most of it is in the south-western portion of the Italian Peninsula (with the Tyrrhenian Sea to its west), but it also includes the small Phlegraean Islan ...

region of southern Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

—often exceeds this, with correspondingly large trunk diameters. The silvery green leaves

A leaf (: leaves) is a principal appendage of the stem of a vascular plant, usually borne laterally above ground and specialized for photosynthesis. Leaves are collectively called foliage, as in "autumn foliage", while the leaves, stem, ...

are oblong, measuring long and wide. The trunk is typically gnarled and twisted.

The small, white, feathery flowers

Flowers, also known as blooms and blossoms, are the reproductive structures of flowering plants ( angiosperms). Typically, they are structured in four circular levels, called whorls, around the end of a stalk. These whorls include: calyx, m ...

—with ten-cleft calyx and corolla, two stamen

The stamen (: stamina or stamens) is a part consisting of the male reproductive organs of a flower. Collectively, the stamens form the androecium., p. 10

Morphology and terminology

A stamen typically consists of a stalk called the filament ...

s, and bifid stigma—are borne generally on the previous year's wood, in raceme

A raceme () or racemoid is an unbranched, indeterminate growth, indeterminate type of inflorescence bearing flowers having short floral stalks along the shoots that bear the flowers. The oldest flowers grow close to the base and new flowers are ...

s springing from the axils of the leaves.

The fruit is a small drupe

In botany, a drupe (or stone fruit) is a type of fruit in which an outer fleshy part (exocarp, or skin, and mesocarp, or flesh) surrounds a single shell (the ''pip'' (UK), ''pit'' (US), ''stone'', or ''pyrena'') of hardened endocarp with a seed ...

, long when ripe, thinner-fleshed and smaller in wild plants than in orchard cultivars. Olives are harvested in the green to purple stage. ''O. europaea'' contains a pyrena commonly referred to in American English as a "pit", and in British English as a "stone".

Taxonomy

The six natural subspecies of ''Olea europaea'' are distributed over a wide range: *''O. e.'' subsp. ''europaea'' (Mediterranean Basin) The subspecies ''europaea'' is divided into two varieties, the ''europaea'', which was formerly named ''Olea sativa'', with theseedling

A seedling is a young sporophyte developing out of a plant embryo from a seed. Seedling development starts with germination of the seed. A typical young seedling consists of three main parts: the radicle (embryonic root), the hypocotyl (embry ...

s called "olivasters", and ''silvestris'', which corresponds to the old wildly growing Mediterranean species '' O. oleaster'', with the seedlings called "oleasters". The ''sylvestris'' is characterized by a smaller, shrubby tree that produces smaller fruits and leaves.

* ''O. e.'' subsp. ''cuspidata'' (from South Africa throughout East Africa, Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula (, , or , , ) or Arabia, is a peninsula in West Asia, situated north-east of Africa on the Arabian plate. At , comparable in size to India, the Arabian Peninsula is the largest peninsula in the world.

Geographically, the ...

to Southwest China

Southwestern China () is a region in the People's Republic of China. It consists of five provincial administrative regions, namely Chongqing, Sichuan, Guizhou, Yunnan, and Xizang.

Geography

Southwestern China is a rugged and mountainous region, ...

)

*''O. e.'' subsp. ''cerasiformis'' (Madeira

Madeira ( ; ), officially the Autonomous Region of Madeira (), is an autonomous Regions of Portugal, autonomous region of Portugal. It is an archipelago situated in the North Atlantic Ocean, in the region of Macaronesia, just under north of ...

); also known as ''Olea maderensis''

*''O. e.'' subsp. ''guanchica'' (Canary Islands)

*''O. e.'' subsp. ''laperrinei'' (Algeria, Sudan, Niger)

*''O. e.'' subsp. ''maroccana'' (Morocco)

The subspecies ''O. e. cerasiformis'' is tetraploid

Polyploidy is a condition in which the cells of an organism have more than two paired sets of ( homologous) chromosomes. Most species whose cells have nuclei (eukaryotes) are diploid, meaning they have two complete sets of chromosomes, one fro ...

, and ''O. e. maroccana'' is hexaploid. Wild-growing forms of the olive are sometimes treated as the species ''Olea oleaster

''Olea oleaster'', or wild olive, is a

On the origins and domestication of the olive: a review and perspectives

Ann Bot. 2018 Mar 5;121(3):385-403. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcx145. Erratum in: Ann Bot. 2018 Mar 5;121(3):587-588. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy002. PMID: 29293871; PMCID: PMC5838823. Beyond its immediate native range, the cultivated olive historically spread across

Olives are thought to have been domesticated in the third millennium BC at the latest, at which point they, along with grain and grapes, became part of

Olives are thought to have been domesticated in the third millennium BC at the latest, at which point they, along with grain and grapes, became part of

Olives were one of the main elements in ancient Israelite cuisine. Olive oil was used not only culinarily, but also for lighting, sacrificial offerings,

Olives were one of the main elements in ancient Israelite cuisine. Olive oil was used not only culinarily, but also for lighting, sacrificial offerings,

American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Accessed 9 Jul. 2012. the trees represent

In

In

Transcription

available at Founders Online. Jefferson believed the olive tree would be a valuable crop in America and could help alleviate poverty and improve the lives of enslaved people; he wrote letters to various agricultural societies urging them to consider introducing olive cultivation in the U.S., advocating for "an olive tree planted for every American slave", particularly in the

Raw or fresh olives are naturally very bitter and astringent; to make them palatable, olives must be cured and fermented, thereby removing

Raw or fresh olives are naturally very bitter and astringent; to make them palatable, olives must be cured and fermented, thereby removing

Olive wood is very hard and tough and is prized for its durability, colour, high combustion temperature, and interesting grain patterns. Because of the commercial importance of the fruit, slow growth, and relatively small size of the tree, olive wood and its products are relatively expensive. Common uses of olive wood include kitchen utensils, carved wooden bowls, cutting boards, fine furniture, and decorative items. The yellow or light greenish-brown wood is often finely veined with a darker tint; being very hard and close-grained, it is valued by woodworkers.

Olive wood is very hard and tough and is prized for its durability, colour, high combustion temperature, and interesting grain patterns. Because of the commercial importance of the fruit, slow growth, and relatively small size of the tree, olive wood and its products are relatively expensive. Common uses of olive wood include kitchen utensils, carved wooden bowls, cutting boards, fine furniture, and decorative items. The yellow or light greenish-brown wood is often finely veined with a darker tint; being very hard and close-grained, it is valued by woodworkers.

The earliest evidence for the domestication of olives comes from the

The earliest evidence for the domestication of olives comes from the  Olives are cultivated in many regions of the world with

Olives are cultivated in many regions of the world with

Since its first domestication, ''O. europaea'' has been spreading back to the wild from planted groves. Its original wild populations in southern Europe have been largely swamped by

Since its first domestication, ''O. europaea'' has been spreading back to the wild from planted groves. Its original wild populations in southern Europe have been largely swamped by

Most olives today are harvested by shaking the boughs or the whole tree. Using olives found lying on the ground can result in poor quality oil, due to damage. Another method involves standing on a ladder and "milking" the olives into a sack tied around the harvester's waist. This method produces high quality oil. A third method uses a device called an oli-net that wraps around the tree trunk and opens to form an umbrella-like catcher from which workers collect the fruit. Another method uses an electric tool with large tongs that spin around quickly, removing fruit from the tree.

Table olive varieties are more difficult to harvest, as workers must take care not to damage the fruit; baskets that hang around the worker's neck are used. In some places in Italy, Croatia, and Greece, olives are harvested by hand because the terrain is too mountainous for machines. As a result, the fruit is not bruised, which leads to a superior finished product. The method also involves sawing off branches, which is healthy for future production."Unusual Olives", ''Epikouria Magazine'', Spring/Summer 2006

The amount of oil contained in the fruit differs greatly by cultivar; the

Most olives today are harvested by shaking the boughs or the whole tree. Using olives found lying on the ground can result in poor quality oil, due to damage. Another method involves standing on a ladder and "milking" the olives into a sack tied around the harvester's waist. This method produces high quality oil. A third method uses a device called an oli-net that wraps around the tree trunk and opens to form an umbrella-like catcher from which workers collect the fruit. Another method uses an electric tool with large tongs that spin around quickly, removing fruit from the tree.

Table olive varieties are more difficult to harvest, as workers must take care not to damage the fruit; baskets that hang around the worker's neck are used. In some places in Italy, Croatia, and Greece, olives are harvested by hand because the terrain is too mountainous for machines. As a result, the fruit is not bruised, which leads to a superior finished product. The method also involves sawing off branches, which is healthy for future production."Unusual Olives", ''Epikouria Magazine'', Spring/Summer 2006

The amount of oil contained in the fruit differs greatly by cultivar; the

. ARA-diari (2015-06-18). Retrieved on 2015-06-20. * Some Italian olive trees are believed to date back to

File:Old olive tree in Maslina Kaštela, Croatia.jpg, Kaštela, Croatia

File:Ulivone di Canneto Sabino.jpg, Canneto Sabino, Italy

File:Olive tree Karystos2.jpg, Karystos, Euboia, Greece

File:OlivaAjv.jpg, Partenit, Ukraine

Agricultural Research Service, US Department of Agriculture; Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN): ''Olea europaea''

Most Common Spanish Olea Trees, Ginart Oleas

{{Authority control Cocktail garnishes Domesticated crops Drought-tolerant trees Drupes Flora of East Tropical Africa Flora of France Flora of Macaronesia Flora of Northeast Tropical Africa Flora of South Tropical Africa Flora of Southeastern Europe Flora of Southern Africa Flora of Southwestern Europe Flora of the Arabian Peninsula Flora of the Mediterranean basin Flora of the Western Indian Ocean Flora of Western Asia Garden plants of Africa Garden plants of Asia Garden plants of Europe Medicinal plants Mediterranean cuisine Ornamental trees Plants described in 1753 Plants in the Bible Plants used in bonsai Spanish cuisine Symbols of Athena Taxa named by Carl Linnaeus Tree crops Trees of Africa Trees of Ethiopia Trees of Europe Trees of Mediterranean climate Trees of Morocco Trees of Turkey Succulent plants Californian cuisine

white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no chroma). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully (or almost fully) reflect and scatter all the visible wa ...

" and "black

Black is a color that results from the absence or complete absorption of visible light. It is an achromatic color, without chroma, like white and grey. It is often used symbolically or figuratively to represent darkness.Eva Heller, ''P ...

" olives in Southeast Asia are not actually olives but species of '' Canarium''.

Cultivars

Hundreds of cultivars of the olive tree are known. An olive's cultivar has a significant impact on its colour, size, shape, and growth characteristics, as well as the qualities of olive oil. Olive cultivars may be used primarily for oil, eating, or both. Olives cultivated for consumption are generally referred to as "table olives". Since many olive cultivars are self-sterile or nearly so, they are generally planted in pairs with a single primary cultivar and a secondary cultivar selected for its ability to fertilize the primary one. In recent times, efforts have been directed at producing hybrid cultivars with qualities useful to farmers, such as resistance to disease, quick growth, and larger or more consistent crops.History

As one of the oldest cultivated trees on Earth, the history of the olive is deeply intertwined with humans; its ecological success and expansion is largely the result of human activity rather than environmental conditions, with the tree's genetic and geographic trajectory directly reflecting the rise and fall of several civilizations. Owing to this deep relationship with humans, the olive has been disseminated well beyond its native range, spanning 28.6 million acres across 66 countries. There were an estimated 865 million olive trees in the world in 2005, of which the vast majority were found in Mediterranean countries; traditionally marginal areas accounted for no more than 25% of olive-planted area and 10% of oil production.Mediterranean Basin

Fossil evidence indicates that the olive tree had its origins 20–40 million years ago in theOligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

, in what now corresponds to Italy and the eastern Mediterranean Basin. Around 100,000 years ago, olives were used by humans in Africa, on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, for fuel and most probably for consumption. Wild olive trees, or oleasters, have been collected in the Eastern Mediterranean

The Eastern Mediterranean is a loosely delimited region comprising the easternmost portion of the Mediterranean Sea, and well as the adjoining land—often defined as the countries around the Levantine Sea. It includes the southern half of Turkey ...

since approximately 19,000 BP; the genome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

of cultivated olives reflects their origin from oleaster populations in the region.

The olive plant was first cultivated in the Mediterranean between 8,000 and 6,000 years ago. Domestication likely began in the Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

, based on archeological findings in ancient tombs—including written tablets, olive pits, and olive wood fragments—as well as genetic analyses.

For thousands of years, olives were grown primarily for lamp oil rather than for culinary purposes, as the natural fruit has an extremely bitter taste. It is very likely that the first mechanized agricultural methods and tools were those designed to produce olive oil; the earliest olive oil production dates back some 6,500 years ago in coastal Israel. As far back as 3000BC, olives were grown commercially in Crete

Crete ( ; , Modern Greek, Modern: , Ancient Greek, Ancient: ) is the largest and most populous of the Greek islands, the List of islands by area, 88th largest island in the world and the List of islands in the Mediterranean#By area, fifth la ...

and may have been the main source of wealth for the Minoan civilization

The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age culture which was centered on the island of Crete. Known for its monumental architecture and energetic art, it is often regarded as the first civilization in Europe. The ruins of the Minoan palaces at K ...

.

The exact ancestry of the cultivated olive is unknown. Fossil ''olea

''Olea'' ( ) is a genus of flowering plants in the family Oleaceae. It includes 12 species native to warm temperate and tropical regions of the Middle East, southern Europe, Africa, southern Asia, and Australasia. They are evergreen trees and s ...

'' pollen has been found in Macedonia and other places around the Mediterranean, indicating that this genus is an original element of the Mediterranean flora. Fossilized leaves of ''olea'' were found in the palaeosols of the volcanic Greek island of Santorini

Santorini (, ), officially Thira (, ) or Thera, is a Greek island in the southern Aegean Sea, about southeast from the mainland. It is the largest island of a small, circular archipelago formed by the Santorini caldera. It is the southern ...

and dated to about 37,000 BP. Imprints of larvae of olive whitefly

Whiteflies are Hemipterans that typically feed on the undersides of plant leaves. They comprise the family Aleyrodidae, the only family in the superfamily Aleyrodoidea. More than 1550 species have been described.

Description and taxonomy

The A ...

'' Aleurobus olivinus'' were found on the leaves. The same insect is commonly found today on olive leaves, showing that the plant-animal co-evolutionary relations have not changed since that time. Other leaves found on the same island date back to 60,000 BP, making them the oldest known olives from the Mediterranean.

Expansion and propagation

In the 16th century BC, thePhoenicians

Phoenicians were an ancient Semitic group of people who lived in the Phoenician city-states along a coastal strip in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily modern Lebanon and the Syrian coast. They developed a maritime civi ...

—a seafaring people native to the Levantine heartland where olives likely were first cultivated—started disseminating the olive throughout the Mediterranean. Owing to their dominance as traders, merchants, and mariners, they succeeded in spreading the olive to the Greek isles, particularly Crete, later introducing it to the Greek mainland between the 14th and 12th centuries BC. Olive cultivation increased and gained great importance among the Greeks; Athenian statesman Solon

Solon (; ; BC) was an Archaic Greece#Athens, archaic History of Athens, Athenian statesman, lawmaker, political philosopher, and poet. He is one of the Seven Sages of Greece and credited with laying the foundations for Athenian democracy. ...

(c. 630 – c. 560 BC) issued decrees regulating olive planting and encouraging its cultivation, particularly for export. Greek literature and mythology reflected the privileged and even sacred position of the olive, while leading thinkers and figures like Hippocrates, Homer, and Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

observed its various positive properties and benefits.

The earliest evidence of the olive tree in Egypt traces back to the Eighteenth Dynasty

The Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt (notated Dynasty XVIII, alternatively 18th Dynasty or Dynasty 18) is classified as the first dynasty of the New Kingdom of Egypt, the era in which ancient Egypt achieved the peak of its power. The Eighteenth Dynasty ...

(1570–1345 BC), during the same period the Phoenicians began distributing it across the Mediterranean. However, scenes on the walls of the tomb of King Teti (ruled c. 2345 BC to c. 2333 BC) show olive fruits and trees, though it is unclear if these represent domestic cultivation. Pharoah Ramses III (reigned 1186–1155 BC) promoted cultivating olive trees and offered the olive oil extracted from Heliopolis to the Sun God Ra; papyrus manuscripts dated to his reign (c. 1550 BC), as well as temple engravings, depict the growing of olive trees and the use of olive oil in cooking, lamps, cosmetics, medicine and embalming. Pharoah Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

, who ruled from ca. 1333 to 1323 BC, wore a garland of olive branches originated from Dakhla Oasis, 360 km to the east. Egyptian mummies dating back to the 20-25th dynasties (c.1185 BC to c. 656 BC) have also been found wearing olive wreaths.

While there is no evidence of olive cultivation in Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, olive wood appears as early as the mid third millennium BC

File:3rd millennium BC montage.jpg, 400x400px, From top left clockwise: Pyramid of Djoser; Khufu; Great Pyramid of Giza, one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World; Cuneiform, a contract for the sale of a field and a house; Enheduana, a high ...

; the site of Emar in present-day Syria has olive wood and olive pits dating to the Middle Bronze Age

The Bronze Age () was a historical period characterised principally by the use of bronze tools and the development of complex urban societies, as well as the adoption of writing in some areas. The Bronze Age is the middle principal period of ...

(2000–1600 BC). The Code of Hammurabi

The Code of Hammurabi is a Babylonian legal text composed during 1755–1750 BC. It is the longest, best-organized, and best-preserved legal text from the ancient Near East. It is written in the Old Babylonian dialect of Akkadian language, Akkadi ...

, a compilation of laws and edicts made by King Hammurabi

Hammurabi (; ; ), also spelled Hammurapi, was the sixth Amorite king of the Old Babylonian Empire, reigning from to BC. He was preceded by his father, Sin-Muballit, who abdicated due to failing health. During his reign, he conquered the ci ...

of the Old Babylonian Empire

The Old Babylonian Empire, or First Babylonian Empire, is dated to , and comes after the end of Sumerian power with the destruction of the Third Dynasty of Ur, and the subsequent Isin-Larsa period. The chronology of the first dynasty of Babylon ...

(reigning from c. 1792 to c. 1750 BC), makes repeated references to olive oil as a key commodity. The Assyrian Empire (858–627 BC) may have expanded into the southern Levant partly to secure control over its lucrative olive oil production.

From the sixth century BC onwards, the olive continued spreading toward the central and western Mediterranean through colonization and commerce, reaching Sicily, Libya, and Tunisia. From there, it expanded into southern Italy among the various Etruscan, Sabine, and Italic peoples. The introduction of the olive tree to mainland Italy allegedly occurred during the reign of Lucius Tarquinius Priscus

Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (), or Tarquin the Elder, was the legendary fifth king of Rome and first of its Etruscan dynasty. He reigned for thirty-eight years.Livy, '' ab urbe condita libri'', I Tarquinius expanded Roman power through military ...

(616 – 578 BC), possibly from Tripoli (Libya) or Gabes (Tunisia). Cultivation moved as far upwards as Liguria

Liguria (; ; , ) is a Regions of Italy, region of north-western Italy; its Capital city, capital is Genoa. Its territory is crossed by the Alps and the Apennine Mountains, Apennines Mountain chain, mountain range and is roughly coextensive with ...

near the border with France. When the Romans arrived in North Africa beginning in the second half of the first century BC, the native Berbers

Berbers, or the Berber peoples, also known as Amazigh or Imazighen, are a diverse grouping of distinct ethnic groups indigenous to North Africa who predate the arrival of Arab migrations to the Maghreb, Arabs in the Maghreb. Their main connec ...

knew how to graft wild olives and had highly developed its cultivation throughout the region.

The olive's expansion and cultivation reached its greatest extent through Rome's gradual conquest and settlement across virtually the entire Mediterranean; the Romans continued propagating the olive for commercial and agricultural purposes, as well as to assimilate local populations. It was introduced in present-day Marseille around 600 BC and spread from there to the whole of Gaul

Gaul () was a region of Western Europe first clearly described by the Roman people, Romans, encompassing present-day France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and parts of Switzerland, the Netherlands, Germany, and Northern Italy. It covered an area of . Ac ...

(modern France). The olive tree made its appearance in Sardinia

Sardinia ( ; ; ) is the Mediterranean islands#By area, second-largest island in the Mediterranean Sea, after Sicily, and one of the Regions of Italy, twenty regions of Italy. It is located west of the Italian Peninsula, north of Tunisia an ...

following Roman conquest in the third century BC, though it may not have reached nearby Corsica until after the fall of the western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

in the fifth century AD.

Although olive growing was introduced to Spain by the Phoenicians some time in 1050 BC, it did not reach a larger scale until the arrival of Scipio (212 BC) during the Second Punic War against Carthage. After the Third Punic War

The Third Punic War (149–146 BC) was the third and last of the Punic Wars fought between Carthage and Rome. The war was fought entirely within Carthaginian territory, in what is now northern Tunisia. When the Second Punic War ended in 20 ...

(149 – 146 BC), olives occupied a large stretch of the Baetica

Hispania Baetica, often abbreviated Baetica, was one of three Roman provinces created in Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) in 27 BC. Baetica was bordered to the west by Lusitania, and to the northeast by Tarraconensis. Baetica remained one of ...

valley in southwest Spain and spread towards the central and Mediterranean coastal areas of the Iberian Peninsula, including Portugal. Through the second century AD, this region would become the largest source of olives and olive oil within the empire. Olive became a core part of the Roman diet, and by extension a major economic pillar; the cultivation, harvesting, and trade in olives and their derived goods sustained many livelihoods and regions. The emperor Hadrian

Hadrian ( ; ; 24 January 76 – 10 July 138) was Roman emperor from 117 to 138. Hadrian was born in Italica, close to modern Seville in Spain, an Italic peoples, Italic settlement in Hispania Baetica; his branch of the Aelia gens, Aelia '' ...

(117 – 138 AD) passed laws prompting olive cultivation by exempting individuals who grew olive trees from rent payments on their land for ten years.

The degree to which the olive benefited from the Romans is demonstrated by the significant decline in olive planting and olive oil production that followed the collapse of the Roman Empire. Beginning in the early eighth century AD, Muslim Arabs and North Africans brought their own varieties of olives during their conquest of Iberia, reinvigorating and expanding olive growing throughout the peninsula. The spread and importance of olives during subsequent Islamic rule is reflected in the Arabic roots of the Spanish words for olive (''aceituna''), oil (''aceite''), and wild olive tree (''acebuche'') and the Portuguese words for olive (''azeitona'') and olive oil (''azeite'').

Outside the Mediterranean

The olive is not native outside the Mediterranean Basin, although various wild subspecies are endemic throughout Sub-Saharan Africa,southern Arabia

South Arabia (), or Greater Yemen, is a historical region that consists of the southern region of the Arabian Peninsula in West Asia, mainly centered in what is now the Republic of Yemen, yet it has also historically included Najran, Jazan, ...

, and central and south Asia.Besnard G, Terral JF, Cornille AOn the origins and domestication of the olive: a review and perspectives

Ann Bot. 2018 Mar 5;121(3):385-403. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcx145. Erratum in: Ann Bot. 2018 Mar 5;121(3):587-588. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcy002. PMID: 29293871; PMCID: PMC5838823. Beyond its immediate native range, the cultivated olive historically spread across

West Asia

West Asia (also called Western Asia or Southwest Asia) is the westernmost region of Asia. As defined by most academics, UN bodies and other institutions, the subregion consists of Anatolia, the Arabian Peninsula, Iran, Mesopotamia, the Armenian ...

through southwest China, and into parts of southern Egypt, northeast Sudan, the Canary Islands

The Canary Islands (; ) or Canaries are an archipelago in the Atlantic Ocean and the southernmost Autonomous communities of Spain, Autonomous Community of Spain. They are located in the northwest of Africa, with the closest point to the cont ...

, and possibly the mountains of the Sahara

The Sahara (, ) is a desert spanning across North Africa. With an area of , it is the largest hot desert in the world and the list of deserts by area, third-largest desert overall, smaller only than the deserts of Antarctica and the northern Ar ...

. Olive domestication is present on every inhabited continent due human introduction.

Americas

Spanish colonists brought the olive to theNew World

The term "New World" is used to describe the majority of lands of Earth's Western Hemisphere, particularly the Americas, and sometimes Oceania."America." ''The Oxford Companion to the English Language'' (). McArthur, Tom, ed., 1992. New York: ...

in the 18th century, where its cultivation prospered in present-day Peru, Chile, Uruguay and Argentina. The first seedlings from Spain were planted in Lima

Lima ( ; ), founded in 1535 as the Ciudad de los Reyes (, Spanish for "City of Biblical Magi, Kings"), is the capital and largest city of Peru. It is located in the valleys of the Chillón River, Chillón, Rímac River, Rímac and Lurín Rive ...

by Antonio de Rivera in 1560. Olive tree cultivation quickly spread along the valleys of South America's dry Pacific coast where the climate is similar to the Mediterranean.

Spanish missionaries established the olive tree in California

California () is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States that lies on the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. It borders Oregon to the north, Nevada and Arizona to the east, and shares Mexico–United States border, an ...

between 1769 and 1795 at Mission San Diego de Alcalá

Mission Basilica San Diego de Alcalá (, lit. The Mission of Saint Didacus of Acalá) was the second Franciscan founded mission in the Californias (after San Fernando de Velicata), a province of New Spain. Located in present-day San Diego, C ...

. Orchards were started at other missions, but by 1838, only two olive orchards were confirmed in California. Cultivation for oil gradually became a highly successful commercial venture from the 1860s onward.

Olive growing in the United States is primarily concentrated in warmer regions like California, Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, Georgia, and Florida. California is by far the largest olive producer in the U.S., accounting for 95 percent of domestic olives; as of 2021, there are roughly 36,000 acres under olive cultivation in the U.S., of which about 35,000 acres are in California. However, the industry is also expanding into the southeastern U.S., with Florida and Georgia experiencing growth in olive farming.

Asia

Olive trees were successfully introduced in Japan in 1908 on Shodo Island; located in theSeto Inland Sea

The , sometimes shortened to the Inland Sea, is the body of water separating Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu, three of the four main islands of Japan. It serves as a waterway connecting the Pacific Ocean to the Sea of Japan. It connects to Osaka Ba ...

, the island has a moderate climate characterized by stable year-round temperature and relatively low rainfall. It became the cradle of olive cultivation in Japan, accounting for over 95% of the country's total production, and earning the nickname "Olive Island". Olives play a central role in the local culture and economy, with the island's mascot and tourism merchandise reflecting olive themes. Olive cultivation has spread to other regions in Japan, namely neighboring Kagawa and Okayama

is the prefectural capital, capital Cities of Japan, city of Okayama Prefecture in the Chūgoku region of Japan. The Okayama metropolitan area, centered around the city, has the largest urban employment zone in the Chugoku region of western J ...

and nearby Kyushu

is the third-largest island of Japan's Japanese archipelago, four main islands and the most southerly of the four largest islands (i.e. excluding Okinawa Island, Okinawa and the other Ryukyu Islands, Ryukyu (''Nansei'') Ryukyu Islands, Islands ...

. The vast majority of Japanese growers are small-scale farmers.

Since 2010, Pakistan has been pursuing large scale commercial olive production, which it identified as a strategic national priority to reduce dependence on foreign oils and expand economic opportunity. As part of the national Ten Billion Tree Tsunami Project launched in 2019, which aimed to plant 10 billion trees to mitigate climate change and environmental degradation, the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (; ; , ; abbr. KP or KPK), formerly known as the North West Frontier Province (NWFP), is a Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Pakistan. Located in the Northern Pakistan, northwestern region of the country, Khyber ...

provincial government planted thousands of olives to symbolize peace and provide commercial opportunities in the war-torn region. By 2020, with the help of experts from Spain and Italy, Pakistan imported thousands of trees and identified 10 million acres for growing olives. The following year, the federal Ministry of Climate Change launched the Olive Trees Tsunami Project to plant nearly 10 million hectares of olive trees. In 2022, Pakistan announced its intention to join the International Olive Council as part of ongoing efforts to develop its domestic olive industry. As of January 2025, the country had 5.6 million cultivated olive trees, with 500,000 to 800,000 new trees planted annually, as well as 80 million wild olive trees. Punjab

Punjab (; ; also romanised as Panjāb or Panj-Āb) is a geopolitical, cultural, and historical region in South Asia. It is located in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent, comprising areas of modern-day eastern Pakistan and no ...

province plans to plant 50 million olive trees on about 9.8 million acres by 2026.

Commercial olive oil production started in India in 2016, following the planting of olive saplings imported from Israel in Rajasthan

Rajasthan (; Literal translation, lit. 'Land of Kings') is a States and union territories of India, state in northwestern India. It covers or 10.4 per cent of India's total geographical area. It is the List of states and union territories of ...

's Thar Desert

The Thar Desert (), also known as the Great Indian Desert, is an arid region in the north-western part of the Indian subcontinent that covers an area of in India and Pakistan. It is the world's 18th-largest desert, and the world's 9th-large ...

in 2008. Production was spearheaded by Rajasthan Olive Cultivation Limited, a state government-funded agency that offered subsidies and incentives for growing olives, with support from Israeli experts. Olive farms continued expanding into 2020 but saw a precipitous decline in size and production volume by 2023, due to the difficult climate and declining government interest and support.

Global expansion

Amid ongoing climate warming, several small-scale olive production farms have also been established at fairly high latitudes in Europe and North America since the early 21st century, including in the United Kingdom, Germany, and Canada.Symbolic and cultural significance

Modern researchers and historians have identified the olive as one of the defining characteristics of both ancient and contemporary Mediterranean culture, geography, and cuisine.Ancient Greece

Olives are thought to have been domesticated in the third millennium BC at the latest, at which point they, along with grain and grapes, became part of

Olives are thought to have been domesticated in the third millennium BC at the latest, at which point they, along with grain and grapes, became part of Colin Renfrew

Andrew Colin Renfrew, Baron Renfrew of Kaimsthorn, (25 July 1937 – 24 November 2024) was a British archaeologist, paleolinguist and Conservative peer noted for his work on radiocarbon dating, the prehistory of languages, archaeogenetics, ...

's Mediterranean triad of staple crops that fueled the emergence of more complex societies.C. Renfrew, ''The Emergence of Civilisation: The Cyclades and the Aegean in The Third Millennium BC'', 1972, p.280. Olives, and especially (perfumed) olive oil, became a major export product during the Minoan and Mycenae

Mycenae ( ; ; or , ''Mykē̂nai'' or ''Mykḗnē'') is an archaeological site near Mykines, Greece, Mykines in Argolis, north-eastern Peloponnese, Greece. It is located about south-west of Athens; north of Argos, Peloponnese, Argos; and sou ...

an periods. Dutch archaeologist Jorrit Kelder proposed that the Mycenaeans sent shipments of olive oil, probably alongside live olive branches, to the court of Egyptian pharaoh Akhenaten

Akhenaten (pronounced ), also spelled Akhenaton or Echnaton ( ''ʾŪḫə-nə-yātəy'', , meaning 'Effective for the Aten'), was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh reigning or 1351–1334 BC, the tenth ruler of the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eig ...

as a diplomatic gift. In Egypt, these imported olive branches may have acquired ritual meanings, as they are depicted as offerings on the wall of the Aten

Aten, also Aton, Atonu, or Itn (, reconstructed ) was the focus of Atenism, the religious system formally established in ancient Egypt by the late Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Akhenaten. Exact dating for the Eighteenth Dynasty is contested, thou ...

temple and were used in wreaths for the burial of Tutankhamun

Tutankhamun or Tutankhamen, (; ), was an Egyptian pharaoh who ruled during the late Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt. Born Tutankhaten, he instituted the restoration of the traditional polytheistic form of an ...

. It is likely that, as well as being used for culinary purposes, olive oil had various other purposes, including as a perfume.

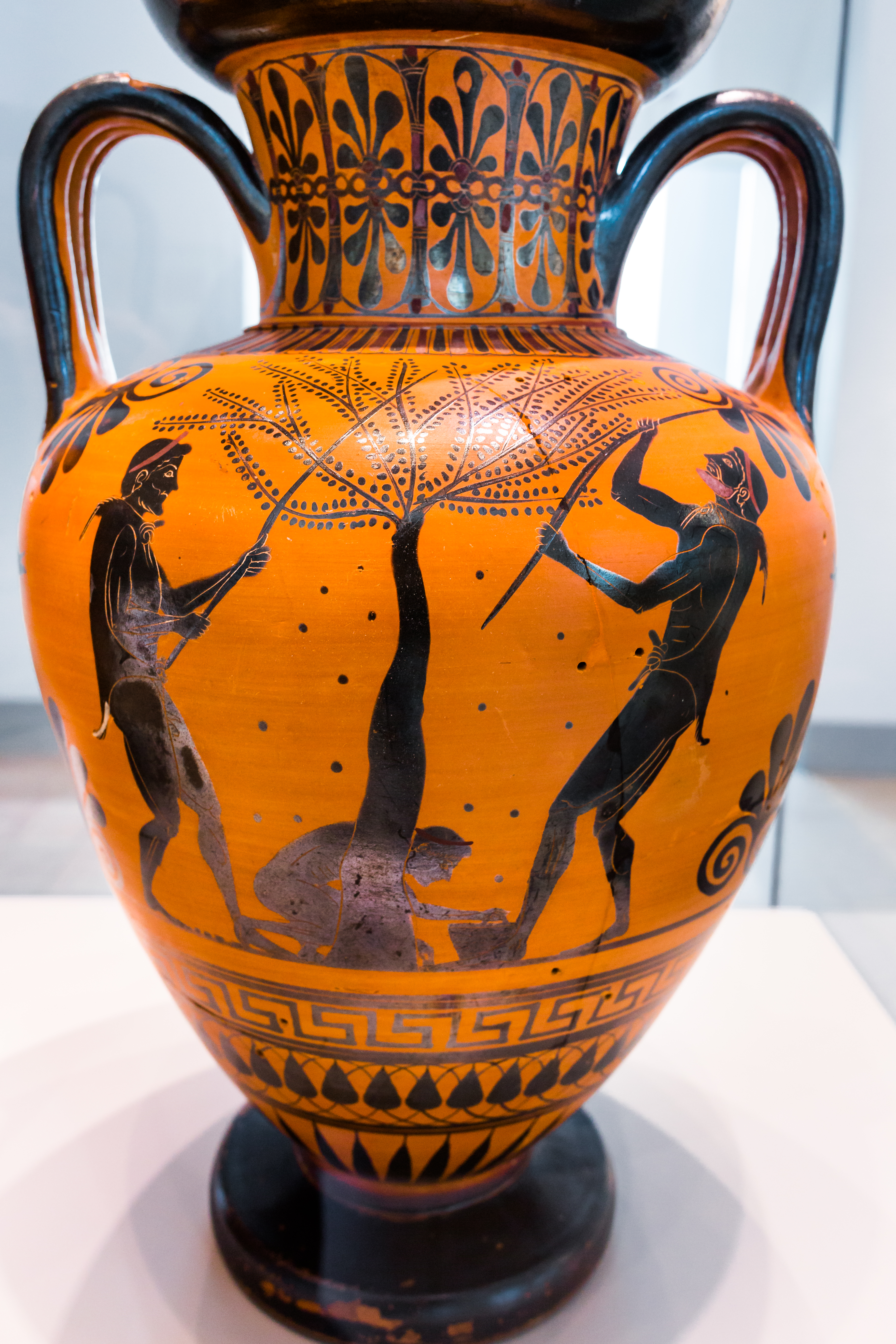

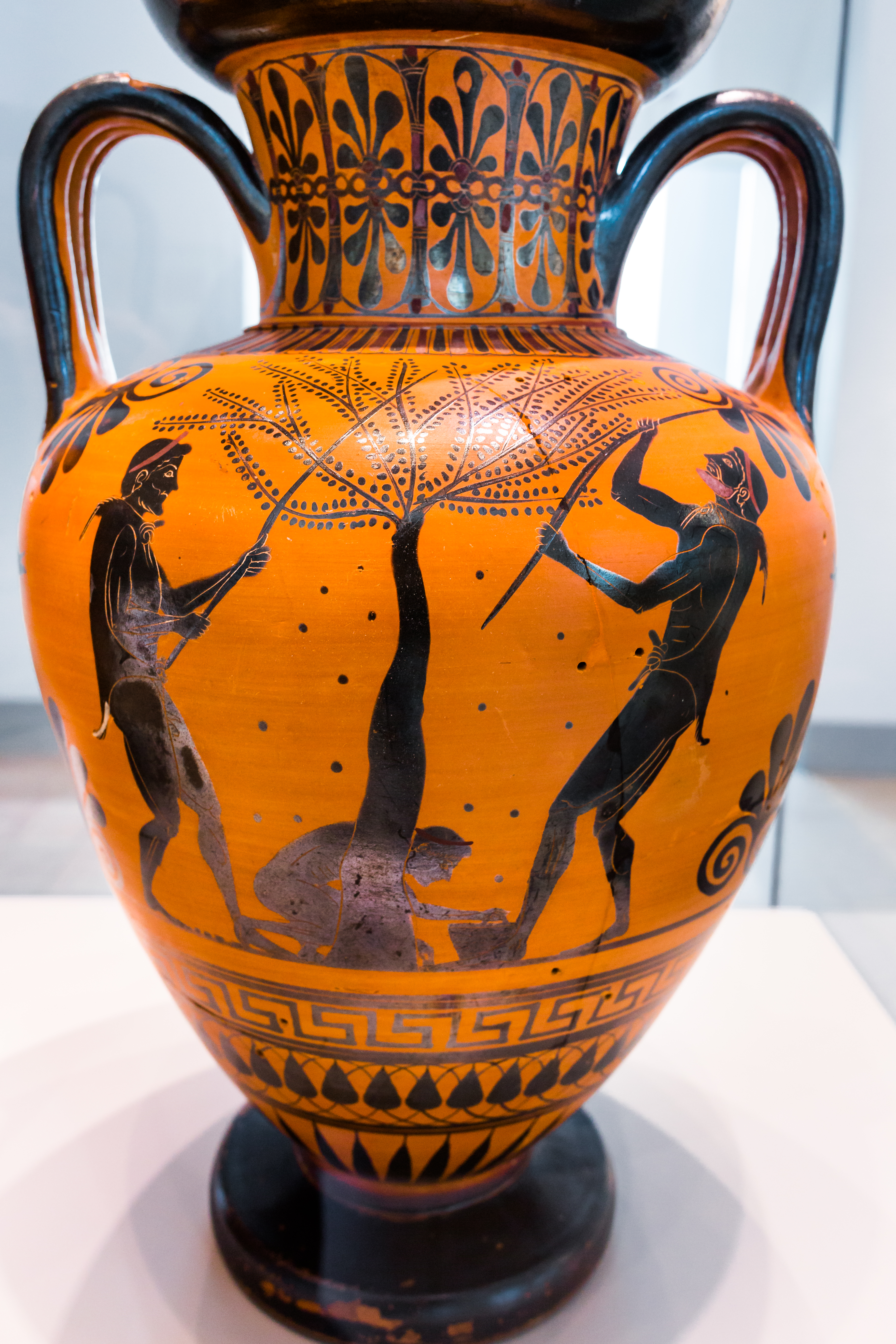

The ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece () was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity (), that comprised a loose collection of culturally and linguistically re ...

smeared olive oil on their bodies and hair as a matter of grooming and good health. Olive oil was used to anoint kings and athletes in ancient Greece. It was burnt in the sacred lamps of temples and was the "eternal flame" of the original Olympic games, whose victors were crowned with its leaves. The olive appears frequently, and often prominently, in ancient Greek literature. Homer's ''Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; ) is one of two major epics of ancient Greek literature attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest surviving works of literature and remains popular with modern audiences. Like the ''Iliad'', the ''Odyssey'' is divi ...

'' (c. eighth century BC), Odysseus

In Greek mythology, Greek and Roman mythology, Odysseus ( ; , ), also known by the Latin variant Ulysses ( , ; ), is a legendary Greeks, Greek king of Homeric Ithaca, Ithaca and the hero of Homer's Epic poetry, epic poem, the ''Odyssey''. Od ...

crawls beneath two shoots of olive that grow from a single stock, and in the ''Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; , ; ) is one of two major Ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the ''Odyssey'', the poem is divided into 24 books and ...

'', (XVII.53ff) there is a metaphoric description of a lone olive tree in the mountains by a spring; the Greeks observed that the olive rarely thrives at a distance from the sea, which in Greece invariably means up mountain slopes. Greek myth attributed to the primordial culture-hero Aristaeus

Aristaeus (; ''Aristaios'') was the mythological culture hero credited with the discovery of many rural useful arts and handicrafts, including bee-keeping; He was the son of the huntress Cyrene and Apollo.

''Aristaeus'' ("the best") was a cu ...

the understanding of olive husbandry, along with cheese-making and beekeeping. Olive was one of the woods used to fashion the most primitive Greek cult figures, called '' xoana'', referring to their wooden material; they were reverently preserved for centuries.

In an archaic Athenian foundation myth, Athena

Athena or Athene, often given the epithet Pallas, is an ancient Greek religion, ancient Greek goddess associated with wisdom, warfare, and handicraft who was later syncretism, syncretized with the Roman goddess Minerva. Athena was regarde ...

won the patronage of Attica

Attica (, ''Attikḗ'' (Ancient Greek) or , or ), or the Attic Peninsula, is a historical region that encompasses the entire Athens metropolitan area, which consists of the city of Athens, the capital city, capital of Greece and the core cit ...

from Poseidon

Poseidon (; ) is one of the twelve Olympians in ancient Greek religion and mythology, presiding over the sea, storms, earthquakes and horses.Burkert 1985pp. 136–139 He was the protector of seafarers and the guardian of many Hellenic cit ...

with the gift of the olive. According to the fourth-century BC father of botany, Theophrastus

Theophrastus (; ; c. 371 – c. 287 BC) was an ancient Greek Philosophy, philosopher and Natural history, naturalist. A native of Eresos in Lesbos, he was Aristotle's close colleague and successor as head of the Lyceum (classical), Lyceum, the ...

, olive trees ordinarily attained an age around 200 years, and he mentions that the very olive tree of Athena still grew on the Acropolis

An acropolis was the settlement of an upper part of an ancient Greek city, especially a citadel, and frequently a hill with precipitous sides, mainly chosen for purposes of defense. The term is typically used to refer to the Acropolis of Athens ...

; it was still to be seen there in the second century AD, and when Pausanias was shown it , he reported "Legend also says that when the Persians fired Athens the olive was burnt down, but on the very day it was burnt it grew again to the height of two cubit

The cubit is an ancient unit of length based on the distance from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. It was primarily associated with the Sumerians, Egyptians, and Israelites. The term ''cubit'' is found in the Bible regarding Noah ...

s." Because olive suckers sprout readily from the stump, and some existing olive trees are purportedly many centuries old, it is possible that the olive tree of the Acropolis dated to the Bronze Age. The olive remained sacred to Athens and its patron deity Athena, appearing on its coinage. According to another myth, Elaea—whose name translates to "olive"—was an accomplished athlete killed by fellow athletes out of envy; owing to her impressive achievement, Athena and Gaia

In Greek mythology, Gaia (; , a poetic form of ('), meaning 'land' or 'earth'),, , . also spelled Gaea (), is the personification of Earth. Gaia is the ancestral mother—sometimes parthenogenic—of all life. She is the mother of Uranus (S ...

turn her into an olive tree as a reward.

The olive and its properties were subject to early scientific and empirical observation. Theophrastus, in ''On the Causes of Plants'', states that the cultivated olive must be vegetatively propagated; indeed, the pits give rise to thorny, wild-type olives, spread far and wide by birds. He also reports how the bearing olive can be grafted on the wild olive, for which the Greeks had a separate name, ''kotinos''. In his '' Enquiry into Plants'', Theophrastus states that the olive can be propagated from a piece of the trunk, the root, a twig, or a stake. Homer described olive oil as "liquid gold", while Hippocrates (c. 460 BCE – c. 375 BCE), widely regarded as the father of medicine, considered it "the great healer".

Ancient Egypt

Ancient Egyptians believed thatIsis

Isis was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion whose worship spread throughout the Greco-Roman world. Isis was first mentioned in the Old Kingdom () as one of the main characters of the Osiris myth, in which she resurrects her sla ...

, the consort of Osiris and the mother of university, taught mankind to extract oil from olives; olive oil has been found among valuable treasures buried in the tombs of important prehistoric Egyptians, and was used as an offering to the gods.

Ancient Rome

Like the Greeks, the Romans held olives in high regard for various purposes, both practical and symbolic. Roman mythology held thatHercules

Hercules (, ) is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

The Romans adapted the Gr ...

introduced the olive tree to Italy from North Africa, while the goddess of wisdom, Minerva

Minerva (; ; ) is the Roman goddess of wisdom, justice, law, victory, and the sponsor of arts, trade, and strategy. She is also a goddess of warfare, though with a focus on strategic warfare, rather than the violence of gods such as Mars. Be ...

, taught the art of cultivation and oil extraction. Numerous archaeological finds indicate the presence of the olive tree in Lazio

Lazio ( , ; ) or Latium ( , ; from Latium, the original Latin name, ) is one of the 20 Regions of Italy, administrative regions of Italy. Situated in the Central Italy, central peninsular section of the country, it has 5,714,882 inhabitants an ...

, the region around Rome, as early as the 7th century BC; however, rudimentary olive production has also been traced back to earlier Etruscan and Sabine settlements in the area.

The olive tree was subject to many treatises and agronomic works by the Romans. Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/24 79), known in English as Pliny the Elder ( ), was a Roman Empire, Roman author, Natural history, naturalist, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the Roman emperor, emperor Vesp ...

, in his first century AD encyclopedia, ''Naturalis Historia

The ''Natural History'' () is a Latin work by Pliny the Elder. The largest single work to have survived from the Roman Empire to the modern day, the ''Natural History'' compiles information gleaned from other ancient authors. Despite the work' ...

,'' describes at least 22 different varieties and qualities of olive trees, detailing their respective techniques for cultivation and production. Pliny also observes that an olive tree is one of only three plants—along with a vine and fig tree

''Ficus'' ( or ) is a genus of about 850 species of woody trees, shrubs, vines, epiphytes and hemiepiphytes in the family (biology), family Moraceae. Collectively known as fig trees or figs, they are native throughout the tropics with a few spe ...

—growing in the middle of the Roman Forum

A forum (Latin: ''forum'', "public place outdoors", : ''fora''; English : either ''fora'' or ''forums'') was a public square in a municipium, or any civitas, of Ancient Rome reserved primarily for the vending of goods; i.e., a marketplace, alon ...

, which served as the center of daily life in the city; the olive was purportedly planted to provide shade. (The garden was recreated in the 20th century).

Roman poet Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 BC – 27 November 8 BC), Suetonius, Life of Horace commonly known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). Th ...

mentions the olive in reference to his own diet, which he describes as very simple: "As for me, olives, endive

Endive () is a leaf vegetable belonging to the genus ''Cichorium'', which includes several similar bitter-leafed vegetables. Species include ''Cichorium endivia'' (also called endive), ''Cichorium pumilum'' (also called wild endive), and ''Cicho ...

s, and smooth mallows provide sustenance." Roman architect and engineer Vitruvius

Vitruvius ( ; ; –70 BC – after ) was a Roman architect and engineer during the 1st century BC, known for his multi-volume work titled . As the only treatise on architecture to survive from antiquity, it has been regarded since the Renaissan ...

describes of the use of charred olive wood in tying together walls and foundations in his ''De Architectura

(''On architecture'', published as ''Ten Books on Architecture'') is a treatise on architecture written by the Ancient Rome, Roman architect and military engineer Vitruvius, Marcus Vitruvius Pollio and dedicated to his patron, the emperor Caesa ...

''. Olive cultivation and production was also recognized for its commercial and economic importance; according to Cato the Younger, among the various tasks of the ''pater familias

The ''pater familias'', also written as ''paterfamilias'' (: ''patres familias''), was the head of a Roman family. The ''pater familias'' was the oldest living male in a household, and could legally exercise autocratic authority over his extende ...

'' (the family patriarch and head of household) was that of keeping an account of the olive oil. The city of Rome designated a special area for negotiating and selling olive oil that was managed by ''negotiaroes oleari'', who were analogous to stockbrokers.

Judaism and Israel

Olives were one of the main elements in ancient Israelite cuisine. Olive oil was used not only culinarily, but also for lighting, sacrificial offerings,

Olives were one of the main elements in ancient Israelite cuisine. Olive oil was used not only culinarily, but also for lighting, sacrificial offerings, ointment

A topical medication is a medication that is applied to a particular place on or in the body. Most often topical medication means application to body surfaces such as the skin or mucous membranes to treat ailments via a large range of classes ...

, and anointing

Anointing is the ritual, ritual act of pouring aromatic oil over a person's head or entire body. By extension, the term is also applied to related acts of sprinkling, dousing, or smearing a person or object with any perfumed oil, milk, butter, ...

religious and political officials.Macdonald, Nathan (2008). '' What Did the Ancient Israelites Eat?''. William B. Eerdmans. pp. 23–24. . The word '' moshiach''—Hebrew for Messiah—means "anointed one"; in Jewish eschatology

Jewish eschatology is the area of Jewish philosophy, Jewish theology concerned with events that will happen in the Eschatology, end of days and related concepts. This includes the ingathering of the exiled Jewish diaspora, diaspora, the coming ...

, the Messiah is a future Jewish king

King is a royal title given to a male monarch. A king is an Absolute monarchy, absolute monarch if he holds unrestricted Government, governmental power or exercises full sovereignty over a nation. Conversely, he is a Constitutional monarchy, ...

from the Davidic line

The Davidic line refers to the descendants of David, who established the House of David ( ) in the Kingdom of Israel (united monarchy), Kingdom of Israel and the Kingdom of Judah. In Judaism, the lineage is based on texts from the Hebrew Bible ...

, who is expected to be anointed with holy oil partially derived from olive oil. The olive tree is one of the first plants mentioned in the Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Noah Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

by a dove to demonstrate that the flood was over ( Genesis 8:11).

The olive's importance in Israel is expressed in the parable of Jotham in Judges 9:8–9: "One day the trees went out to anoint a king for themselves. They said to the olive tree, ‘Be our king.’ But the olive tree answered, ‘Should I give up my oil, by which both gods and humans are honored, to hold sway over the trees?'" The olive tree is also analogized to a righteous man (Psalm 52:8; Hosea 14:6) whose "children will be like vigorous young olive trees" (Psalm 128:3).

. '' Noah Noah (; , also Noach) appears as the last of the Antediluvian Patriarchs (Bible), patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5–9), the Quran and Baháʼí literature, ...

Deuteronomy

Deuteronomy (; ) is the fifth book of the Torah (in Judaism), where it is called () which makes it the fifth book of the Hebrew Bible and Christian Old Testament.

Chapters 1–30 of the book consist of three sermons or speeches delivered to ...

characterizes the "Promised Land

In the Abrahamic religions, the "Promised Land" ( ) refers to a swath of territory in the Levant that was bestowed upon Abraham and his descendants by God in Abrahamic religions, God. In the context of the Bible, these descendants are originally ...

" of the Hebrews

The Hebrews (; ) were an ancient Semitic-speaking peoples, ancient Semitic-speaking people. Historians mostly consider the Hebrews as synonymous with the Israelites, with the term "Hebrew" denoting an Israelite from the nomadic era, which pre ...

as containing olive groves (6:11) and subsequently lists olives as one of the seven species

The Seven Species (, ''Shiv'at HaMinim'') are seven agricultural products—two grains and five fruits—that are listed in the Hebrew Bible as being special products of the Land of Israel.

The seven species listed are wheat, barley, grape, Ficu ...

that are special products of the Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine. The definition ...

(8:8). According to the Halakha

''Halakha'' ( ; , ), also Romanization of Hebrew, transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Judaism, Jewish religious laws that are derived from the Torah, Written and Oral Torah. ''Halakha'' is ...

, the Jewish law mandatory for all Jews

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of History of ancient Israel and Judah, ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, rel ...

, the olive is one of the seven species that require the recitation of ''me'eyn shalosh,'' a blessing of gratitude, after they are consumed. Olive oil is also the most recommended and best possible oil for lighting Shabbat candles.

Olive oil features prominently in the Jewish festival of Hanukkah

Hanukkah (, ; ''Ḥănukkā'' ) is a Jewish holidays, Jewish festival commemorating the recovery of Jerusalem and subsequent rededication of the Second Temple at the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire in the 2nd ce ...

, which commemorates the recovery of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

and subsequent rededication of the Second Temple

The Second Temple () was the Temple in Jerusalem that replaced Solomon's Temple, which was destroyed during the Siege of Jerusalem (587 BC), Babylonian siege of Jerusalem in 587 BCE. It was constructed around 516 BCE and later enhanced by Herod ...

during the Maccabean Revolt

The Maccabean Revolt () was a Jewish rebellion led by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire and against Hellenistic influence on Jewish life. The main phase of the revolt lasted from 167 to 160 BCE and ended with the Seleucids in control of ...

against the Seleucid Empire

The Seleucid Empire ( ) was a Greek state in West Asia during the Hellenistic period. It was founded in 312 BC by the Macedonian general Seleucus I Nicator, following the division of the Macedonian Empire founded by Alexander the Great ...

in the 2nd century BCE. According to the Talmud

The Talmud (; ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of Haskalah#Effects, modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

, the central text of Rabbinical Judaism, after Seleucid forces had been driven from the Temple, the Maccabees discovered that almost all the ritual olive oil for the Temple menorah

The Temple menorah (; , Tiberian Hebrew ) is a seven-branched candelabrum that is described in the Hebrew Bible and later ancient sources as having been used in the Tabernacle and the Temple in Jerusalem.

Since ancient times, it has served as a ...

had been profaned. They found only single container with just enough pure oil to keep the menorah lit for a single day; however, it burned for eight days—the time needed for new oil to have been prepared—a miracle that forms a major part of Hanukkah celebrations. Subsequently, the olive tree and its oil have come to represent the strength and persistence of the Jewish people

Jews (, , ), or the Jewish people, are an ethnoreligious group and nation, originating from the Israelites of ancient Israel and Judah. They also traditionally adhere to Judaism. Jewish ethnicity, religion, and community are highly inte ...

. In common with other Mediterranean cultures, the Jewish people used it for many practical and ritualistic purposes, from fuel and medicine to cosmetics and even currency; as in Greek and Roman societies, athletes were cleansed by covering their skin with oil then scraping it to remove the dirt. Jews who settled in foreign lands often became olive merchants.

Due to its importance in the Hebrew Bible, the olive has significant national meaning in modern Israeli culture. Two olive branches appear as part of Israel's emblem, which may have been inspired by the vision of biblical Hebrew prophet Zechariah, who describes seeing a menorah flanked by an olive tree on each side;Mishory, Alec. ''The Israeli Emblem''. Jewish Virtual LibraryAmerican-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise. Accessed 9 Jul. 2012. the trees represent

Zerubbabel

Zerubbabel ( from ) was, according to the Hebrew Bible, a governor of the Achaemenid Empire's province of Yehud Medinata and the grandson of Jeconiah, penultimate king of Judah. He is not documented in extra-biblical documents, and is considered ...

and Joshua

Joshua ( ), also known as Yehoshua ( ''Yəhōšuaʿ'', Tiberian Hebrew, Tiberian: ''Yŏhōšuaʿ,'' Literal translation, lit. 'Yahweh is salvation'), Jehoshua, or Josue, functioned as Moses' assistant in the books of Book of Exodus, Exodus and ...

, the governor and high priest, respectively. The olive tree was declared the unofficial national tree of Israel in 2021 by a survey of Israelis; it is often planted during Tu BiShvat and its fruit is a customary part of the accompanying seder.

Christianity

The olive tree, as well as its fruit and oil, play an important role in Christianity. Apart from being mentioned in theHebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;"Tanach"

. '' Old Testament The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

), they appear several times in the . '' Old Testament The Old Testament (OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible, or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew and occasionally Aramaic writings by the Isr ...

New Testament

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus, as well as events relating to Christianity in the 1st century, first-century Christianit ...

. The Mount of Olives east of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is a city in the Southern Levant, on a plateau in the Judaean Mountains between the Mediterranean Sea, Mediterranean and the Dead Sea. It is one of the List of oldest continuously inhabited cities, oldest cities in the world, and ...

figures prominently in the Bible: It is part of the route to Bethany

Bethany (,Murphy-O'Connor, 2008, p152/ref> Syriac language, Syriac: ܒܝܬ ܥܢܝܐ ''Bēṯ ʿAnyā''), locally called in Palestinian Arabic, Arabic Al-Eizariya or al-Aizariya (, "Arabic nouns and adjectives#Nisba,

, which is the site of several key biblical events; where lace