The history of literature is the historical development of

writing

Writing is a medium of human communication which involves the representation of a language through a system of physically Epigraphy, inscribed, Printing press, mechanically transferred, or Word processor, digitally represented Symbols (semiot ...

s in

prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the f ...

or

poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek '' poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings ...

that attempt to provide

entertainment

Entertainment is a form of activity that holds the attention and interest of an audience or gives pleasure and delight. It can be an idea or a task, but is more likely to be one of the activities or events that have developed over thousan ...

,

enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

, or

instruction to the reader/listener/observer, as well as the development of the

literary techniques used in the

communication

Communication (from la, communicare, meaning "to share" or "to be in relation with") is usually defined as the transmission of information. The term may also refer to the message communicated through such transmissions or the field of inqu ...

of these pieces. Not all writings constitute

literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to inclu ...

. Some recorded materials, such as compilations of

data

In the pursuit of knowledge, data (; ) is a collection of discrete values that convey information, describing quantity, quality, fact, statistics, other basic units of meaning, or simply sequences of symbols that may be further interpret ...

(e.g., a

check register) are not considered literature, and this article relates only to the evolution of the works defined above.

Ancient (Bronze Age–5th century)

Early literature is derived from stories told in

hunter-gatherer bands through

oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

, including

myth

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not objectively true, the identification of a narrati ...

and

folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as Narrative, tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, r ...

.

Storytelling emerged as the human mind evolved to apply

causal reasoning and structure events into a

narrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether nonfictional ( memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travelogue, etc.) or fictional (fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller

Thriller may r ...

and

language

Language is a structured system of communication. The structure of a language is its grammar and the free components are its vocabulary. Languages are the primary means by which humans communicate, and may be conveyed through a variety of ...

allowed early humans to share information with one another. Early storytelling provided opportunity to learn about dangers and

social norms

Social norms are shared standards of acceptance, acceptable behavior by groups. Social norms can both be informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of a society, as well as be codified into wikt:rule, rules and laws. Social normat ...

while also entertaining listeners. Myth can be expanded to include all use of patterns and stories to make sense of the world, and it may be psychologically intrinsic to humans.

Epic poetry

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

is recognized as the pinnacle of ancient literature. These works are long narrative poems that recount the feats of mythic heroes, often said to take place in the nation's early history.

The

history of writing

The history of writing traces the development of expressing language by systems of markings and how these markings were used for various purposes in different societies, thereby transforming social organization. Writing systems are the foundati ...

began independently in different parts of the world, including in

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

about 3200 BC, in

Ancient China about 1250 BC, and in

Mesoamerica

Mesoamerica is a historical region and cultural area in southern North America and most of Central America. It extends from approximately central Mexico through Belize, Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, and northern Costa Rica. W ...

about 650 BC. Literature was not initially incorporated in writing, as it was primarily used for simpler purposes, such as

accounting. Some of the earliest surviving works of literature include ''

The Maxims of Ptahhotep

''The Maxims of Ptahhotep'' or ''Instruction of Ptahhotep'' is an ancient Egyptian literary composition composed by the Vizier Ptahhotep around 2375–2350 BC, during the rule of King Djedkare Isesi of the Fifth Dynasty. The text was discovered ...

'' and the ''

Story of Wenamun

The Story of Wenamun (alternately known as the Report of Wenamun, The Misadventures of Wenamun, Voyage of Unamūn, or nformallyas just Wenamun) is a literary text written in hieratic in the Late Egyptian language. It is only known from one incom ...

'' from

Ancient Egypt, ''

Instructions of Shuruppak'' and ''

Poor Man of Nippur

The Poor Man of Nippur is an Akkadian story dating from around 1500 BC. It is attested by only three texts, only one of which is more than a small fragment.

There was a man, a citizen of Nippur, destitute and poor,

Gimil-Ninurta was his name, an ...

'' from Mesopotamia, and ''

Classic of Poetry

The ''Classic of Poetry'', also ''Shijing'' or ''Shih-ching'', translated variously as the ''Book of Songs'', ''Book of Odes'', or simply known as the ''Odes'' or ''Poetry'' (; ''Shī''), is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, co ...

'' from Ancient China.

Mesopotamia

Sumerian literature

Sumerian literature constitutes the earliest known corpus of recorded literature, including the religious writings and other traditional stories maintained by the Sumerian civilization and largely preserved by the later Akkadian and Babylonian em ...

is the oldest known literature, written in

Sumer. Types of literature were not clearly defined, and all Sumerian literature incorporated poetic aspects. Sumerian poems demonstrate basic elements of poetry, including

lines,

imagery, and

metaphor

A metaphor is a figure of speech that, for rhetorical effect, directly refers to one thing by mentioning another. It may provide (or obscure) clarity or identify hidden similarities between two different ideas. Metaphors are often compared wit ...

. Humans, gods, talking animals, and inanimate objects were all incorporated as characters. Suspense and humor were both incorporated into Sumerian stories. These stories were primarily shared orally, though they were also recorded by

scribes

A scribe is a person who serves as a professional copyist, especially one who made copies of manuscripts before the invention of automatic printing.

The profession of the scribe, previously widespread across cultures, lost most of its promi ...

. Some works were associated with specific

musical instruments

A musical instrument is a device created or adapted to make musical sounds. In principle, any object that produces sound can be considered a musical instrument—it is through purpose that the object becomes a musical instrument. A person who pl ...

or contexts and may have been performed in specific settings. Sumerian literature did not use

titles

A title is one or more words used before or after a person's name, in certain contexts. It may signify either generation, an official position, or a professional or academic qualification. In some languages, titles may be inserted between the f ...

, instead being referred to by the work's first line.

Akkadian literature developed in subsequent Mesopotamian societies, such as

Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state ...

and

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the As ...

, from the third to first millennia BC. During this time, it spread to other areas, including Egypt,

Ugarit

)

, image =Ugarit Corbel.jpg

, image_size=300

, alt =

, caption = Entrance to the Royal Palace of Ugarit

, map_type = Near East#Syria

, map_alt =

, map_size = 300

, relief=yes

, location = Latakia Governorate, Syria

, region = ...

, and

Hattusa

Hattusa (also Ḫattuša or Hattusas ; Hittite: URU''Ḫa-at-tu-ša'',Turkish: Hattuşaş , Hattic: Hattush) was the capital of the Hittite Empire in the late Bronze Age. Its ruins lie near modern Boğazkale, Turkey, within the great loop of t ...

. The

Akkadian language

Akkadian (, Akkadian: )John Huehnergard & Christopher Woods, "Akkadian and Eblaite", ''The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the World's Ancient Languages''. Ed. Roger D. Woodard (2004, Cambridge) Pages 218-280 is an extinct East Semitic language th ...

was influenced by the

Sumerian language, and many elements of Sumerian literature were adopted in Akkadian literature. Many works of Akkadian literature were commissioned by kings that had scribes and scholars in their service. Some of these works served to celebrate the king or the divine, while others recorded information for religious practices or medicine. Poetry, proverbs, folktales, love lyrics, and accounts of disputes were all incorporated into Akkadian literature.

Ancient Egypt

Literature of the

Old Kingdom of Egypt

In ancient Egyptian history, the Old Kingdom is the period spanning c. 2700–2200 BC. It is also known as the "Age of the Pyramids" or the "Age of the Pyramid Builders", as it encompasses the reigns of the great pyramid-builders of the Fourt ...

developed directly from practical use during the

Fifth Dynasty

The Fifth Dynasty of ancient Egypt (notated Dynasty V) is often combined with Dynasties Third Dynasty of Egypt, III, Fourth Dynasty of Egypt, IV and Sixth Dynasty of Egypt, VI under the group title the Old Kingdom of Egypt, Old Kingdom. The Fifth ...

. Lists of offerings to the gods were rewritten as prayers, and statistical information about state officials was expanded into

autobiographies

An autobiography, sometimes informally called an autobio, is a self-written account of one's own life.

It is a form of biography.

Definition

The word "autobiography" was first used deprecatingly by William Taylor in 1797 in the English pe ...

. These autobiographies were written to exemplify the virtues of their subjects and often incorporated a free flow style that blended prose and poetry. Kings were not written about beyond clerical recordings, but poetry was performed during the funerals of kings as part of a religious ritual. The ''Instructions'', a form of

wisdom literature

Wisdom literature is a genre of literature common in the ancient Near East. It consists of statements by sages and the wise that offer teachings about divinity and virtue. Although this genre uses techniques of traditional oral storytelling, it ...

that was popular during most of Ancient Egyptian history, taught maxims of

Ancient Egyptian philosophy

Ancient Egyptian philosophy refers to the philosophical works and beliefs of Ancient Egypt. There is some debate regarding its true scope and nature.Juan José Castillos, Ancient Egyptian Philosophy, RSUE 31, 2014, 29-37.

Notable works

One Eg ...

that combined pragmatic thought and religious speculation.

These literary traditions continued to develop in the

Middle Kingdom of Egypt

The Middle Kingdom of Egypt (also known as The Period of Reunification) is the period in the history of ancient Egypt following a period of political division known as the First Intermediate Period. The Middle Kingdom lasted from approximatel ...

as autobiographies became more intricate. The role of the king in literature expanded during this period; royal testaments were written from the perspective of the king to his successor, and celebrations of the king and advocacy of strong leadership were included in autobiographies and ''Instructions''.

Fiction and analysis of

good and evil also developed during this period.

During the

New Kingdom of Egypt

The New Kingdom, also referred to as the Egyptian Empire, is the period in ancient Egyptian history between the sixteenth century BC and the eleventh century BC, covering the Eighteenth, Nineteenth, and Twentieth dynasties of Egypt. Radioc ...

, the popularity of wisdom literature and educational works persisted, though the use of teachings and stories was prioritized over the use of discourses. Entertainment literature was popular among the nobility during this period, incorporating aspects of narrative myth and folklore, religious hymns, love songs, and praise for the king and the city.

Ancient China

Zhou dynasty

Chinese mythology

Chinese mythology () is mythology that has been passed down in oral form or recorded in literature in the geographic area now known as Greater China. Chinese mythology includes many varied myths from regional and cultural traditions.

Much of ...

played a notable role in the earliest Chinese literature, though it was less prominent compared to mythological literature in other civilizations. By the time of the

Zhou dynasty

The Zhou dynasty ( ; Old Chinese ( B&S): *''tiw'') was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of China by ...

, Chinese culture emphasized the community over the individual, discouraging mythological stories of great personages and characterization of the divine. Mythological literature was more common in the southern

Chu

Chu or CHU may refer to:

Chinese history

* Chu (state) (c. 1030 BC–223 BC), a state during the Zhou dynasty

* Western Chu (206 BC–202 BC), a state founded and ruled by Xiang Yu

* Chu Kingdom (Han dynasty) (201 BC–70 AD), a kingdom of the Ha ...

nation. The ''

Tao Te Ching

The ''Tao Te Ching'' (, ; ) is a Chinese classic text written around 400 BC and traditionally credited to the sage Laozi, though the text's authorship, date of composition and date of compilation are debated. The oldest excavated portion d ...

'' and the

''Zhuangzi'' are philosophical compilations that serve as the foundation of Taoism.

Confucius

Confucius ( ; zh, s=, p=Kǒng Fūzǐ, "Master Kǒng"; or commonly zh, s=, p=Kǒngzǐ, labels=no; – ) was a Chinese philosopher and politician of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. C ...

was a defining figure in ancient Chinese

philosophy and

politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that stud ...

. He collected the

Six Classics

The Four Books and Five Classics () are the authoritative books of Confucianism, written in China before 300 BCE. The Four Books and the Five Classics are the most important classics of Chinese Confucianism.

Four Books

The Four Books () are C ...

as founding texts of

Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

, and they became the central texts by which other works were compared in Chinese literary scholarship. Confucianism dominated literary tastes in Ancient China starting in the

Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest ...

.

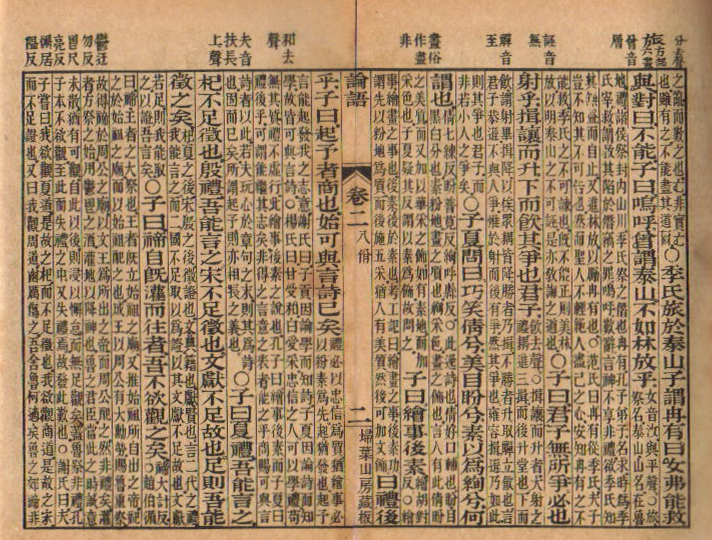

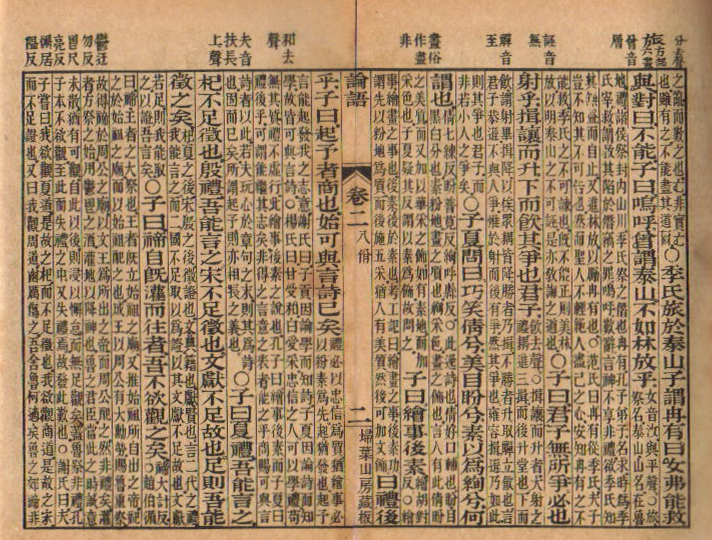

The sayings of Confucius were later compiled into the ''

Analects'' by his students.

Anthologies

In book publishing, an anthology is a collection of literary works chosen by the compiler; it may be a collection of plays, poems, short stories, songs or excerpts by different authors.

In genre fiction, the term ''anthology'' typically catego ...

were common in Ancient China, and anthologizing was used as a means of literary criticism to determine literary classics.

The ''

Classic of Poetry

The ''Classic of Poetry'', also ''Shijing'' or ''Shih-ching'', translated variously as the ''Book of Songs'', ''Book of Odes'', or simply known as the ''Odes'' or ''Poetry'' (; ''Shī''), is the oldest existing collection of Chinese poetry, co ...

'', one of the Six Classics, is the oldest existing anthology of Chinese poetry. It comprises 305 works by anonymous authors dating from the 12th to 7th centuries BC. Prior to the collection of these works, poetic tradition in Ancient China was primarily oral. The ''

Chu Ci

The ''Chu ci'', variously translated as ''Verses of Chu,'' ''Songs of Chu'', or ''Elegies of Chu'', is an ancient anthology of Chinese poetry including works traditionally attributed mainly to Qu Yuan and Song Yu from the Warring States perio ...

'' anthology is a volume of poems from the Warring States period written in Chu and attributed to

Qu Yuan

Qu Yuan ( – 278 BCE) was a Chinese poet and politician in the State of Chu during the Warring States period. He is known for his patriotism and contributions to classical poetry and verses, especially through the poems of the ' ...

. These poems were written as rhapsodies that were meant to be recited with a specific tone rather than sung. The

Music Bureau

The Music Bureau (Traditional Chinese: 樂府; Simplified Chinese: 乐府; Hanyu Pinyin: ''yuèfǔ'', and sometimes known as the "Imperial Music Bureau") served in the capacity of an organ of various imperial government bureaucracies of China: di ...

was developed during the Zhou dynasty, establishing a governmental role for the collection of musical works and folk songs that would persist throughout Chinese history.

Historical documents developed into an early form of literature during the Warring States period, as documentation was combined with narrative and sometimes with legendary accounts of history. Two of the Six Classics, the ''

Book of Documents

The ''Book of Documents'' (''Shūjīng'', earlier ''Shu King'') or ''Classic of History'', also known as the ''Shangshu'' (“Venerated Documents”), is one of the Five Classics of ancient Chinese literature. It is a collection of rhetoric ...

'' and the ''

Spring and Autumn Annals

The ''Spring and Autumn Annals'' () is an ancient Chinese chronicle that has been one of the core Chinese classics since ancient times. The '' Annals'' is the official chronicle of the State of Lu, and covers a 241-year period from 722 to 48 ...

'', are historical documents. The latter inspired works of historical commentary that became a genre in their own right, including the ''

Zuo Zhuan'', the ''

Gongyang Zhuan

The ''Gongyang Zhuan'' (), also known as the ''Gongyang Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals'' or the ''Commentary of Gongyang'', is a commentary on the ''Spring and Autumn Annals'', and is thus one of the Chinese classics. Along with the ' ...

'', and the ''

Guliang Zhuan

The () is considered one of the classic books of ancient Chinese history. It is traditionally attributed to a writer with the surname of Guliang in the disciple tradition of Zixia, but versions of his name vary and there is no definitive way t ...

''. The ''Zuo Zhuan'' is considered to be the first large scale narrative work in Chinese literature. ''

The Art of War

''The Art of War'' () is an ancient Chinese military treatise dating from the Late Spring and Autumn Period (roughly 5th century BC). The work, which is attributed to the ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu ("Master Sun"), is com ...

'' by

Sun Tzu

Sun Tzu ( ; zh, t=孫子, s=孙子, first= t, p=Sūnzǐ) was a Chinese military general, strategist, philosopher, and writer who lived during the Eastern Zhou period of 771 to 256 BCE. Sun Tzu is traditionally credited as the author of '' Th ...

was an influential book on military strategy that is still referenced in the modern era.

Qin and Han dynasties

Poetry written in the brief period of the

Qin dynasty

The Qin dynasty ( ; zh, c=秦朝, p=Qín cháo, w=), or Ch'in dynasty in Wade–Giles romanization ( zh, c=, p=, w=Ch'in ch'ao), was the first dynasty of Imperial China. Named for its heartland in Qin state (modern Gansu and Shaanxi), ...

has been entirely lost. Poetry in the

Han dynasty

The Han dynasty (, ; ) was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China (202 BC – 9 AD, 25–220 AD), established by Emperor Gaozu of Han, Liu Bang (Emperor Gao) and ruled by the House of Liu. The dynasty was preceded by th ...

diverged as several branches developed, including short length, paralleled exposition, rhymed exposition, and ancient style, and

idealism

In philosophy, the term idealism identifies and describes metaphysics, metaphysical perspectives which assert that reality is indistinguishable and inseparable from perception and understanding; that reality is a mental construct closely con ...

also became popular during the Han dynasty.

The ''

Nineteen Old Poems

''Nineteen Old Poems'' (), also known as ''Ku-shih shih-chiu shou'' is an anthology of Chinese poems, consisting of nineteen poems which were probably originally collected during the Han Dynasty. These nineteen poems were very influential on lat ...

'' were written at this time, though how they came about is the subject of debate. Poetry during this period abandoned tetrasyllabic verse in favor of pentasyllabic verse. The ballads of Chu spread through China and became widely popular, often focusing on concepts of inevitable destiny and fate.

Political and argumentative literature by government officials dominated Chinese prose during this period, though even these works often engaged in lyricism and metaphor.

Jia Yi was an essayist known for his emotional political treatises such as ''

The Faults of Qin''.

Chao Cuo was an essayist known for treatises that were meticulous rather than emotional. Confucianism continued to dictate philosophical works, though a movement of works criticizing contemporary application of Confucianism began with

Wang Chong in his ''

Lunheng''. Prose literature meant for entertainment also developed during this period. Historical literature was revolutionized by the ''

Records of the Grand Historian

''Records of the Grand Historian'', also known by its Chinese name ''Shiji'', is a monumental history of China that is the first of China's 24 dynastic histories. The ''Records'' was written in the early 1st century by the ancient Chinese his ...

'', the first general history of ancient times and the largest work of literature to that point in time.

Six Dynasties

Centralism declined during the Six Dynasties period, and Confucianism lost influence as a predominating ideology. This caused the rise of many local traditions of philosophical literature, including that of Taoist and Buddhist ideas. Prose fiction during the Wei and Jin dynasties consisted mainly of supernatural folklore, including those presented as historical. This tradition of supernatural fiction continued during the Northern and Southern Dynasties with the ''Records of Light and Shade'' attributed to

Liu Yiqing

/ ( or ) is an East Asian surname. pinyin: in Mandarin Chinese, in Cantonese. It is the family name of the Han dynasty emperors. The character originally meant 'kill', but is now used only as a surname. It is listed 252nd in the classic text ...

. Another genre of prose was collections of short biographical or anecdotal impressions, of which only ''

A New Account of the Tales of the World'' survives.

Jian'an poetry

Jian'an poetry, or Chien'an poetry (), refers to the styles of Chinese poetry particularly associated with the end of the Han dynasty and the beginning of the Six Dynasties era of China. This poetry category is particularly important because, in ...

developed from the literary tradition of Eastern Han, incorporating idiosyncrasies and strong demonstrations of emotion to express individualism. This movement was led by then-ruler of China

Cao Cao

Cao Cao () (; 155 – 15 March 220), courtesy name Mengde (), was a Chinese statesman, warlord and poet. He was the penultimate Grand chancellor (China), grand chancellor of the Eastern Han dynasty, and he amassed immense power in the End of ...

. The

poetry of Cao Cao

Cao Cao (155–220) was a warlord who rose to power towards the final years of the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 CE) and became the ''de facto'' head of government in China. He laid the foundation for what was to become the state of Cao Wei (220 ...

consisted of ensemble songs published through the Music Bureau and performed with music. The

Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove were influential poets in the Wei dynasty mid-3rd century, addressing political and philosophical concerns directly in their poetry. Chinese poetry developed significantly during the

Jin dynasty, incorporating

parallelism,

prosody, and emotional expression through scenery.

Zhang Hua

Zhang Hua (232–7 May 300According to Sima Zhong's biography in ''Book of Jin'', Zhang Hua was killed on the ''guisi'' day of the 4th month of the 1st year of the ''Yongkang'' era of his reign. This corresponds to 7 May 300 永康元年夏四 ...

,

Lu Ji, and

Pan Yue are recognized as the great poets that developed early Western Jin poetry.

Zuo Si and

Liu Kun

Liu Kun (; born December 1956) is a Chinese politician and the current Minister of Finance. Previously he served as director of Budgetary Affairs Commission of the National People's Congress, Vice-Minister of Finance, and vice-governor of Guang ...

were poets in later Western Jin. In Eastern Jin, philosophical poetry went through a period of abstraction that removed much of its literary elements.

Guo Pu and

Tao Yuanming

Tao Yuanming (; 365–427), also known as Tao Qian (; also T'ao Ch'ien in Wade-Giles), was a Chinese poet and politician who was one of the best-known poets during the Six Dynasties period. He was born during the Eastern Jin dynasty (317-420 ...

were notable poets in Eastern Jin.

The popularity of literary poetry and

aestheticism

Aestheticism (also the Aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century which privileged the aesthetic value of literature, music and the arts over their socio-political functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be p ...

grew during the

Southern Dynasties

The Northern and Southern dynasties () was a period of political division in the history of China that lasted from 420 to 589, following the tumultuous era of the Sixteen Kingdoms and the Eastern Jin dynasty. It is sometimes considered as ...

, and literature as art began to be recognized as distinct from political and philosophical literature. This resulted in the growth of literary criticism, with ''

The Literary Mind and the Carving of Dragons'' and

''Ranking of Poetry'' being written at this time. The

Sixteen Kingdoms

The Sixteen Kingdoms (), less commonly the Sixteen States, was a chaotic period in Chinese history from AD 304 to 439 when northern China fragmented into a series of short-lived dynastic states. The majority of these states were founded by ...

of the

Northern Dynasties

The Northern and Southern dynasties () was a period of political division in the history of China that lasted from 420 to 589, following the tumultuous era of the Sixteen Kingdoms and the Eastern Jin dynasty. It is sometimes considered as ...

saw little cultural growth due to their instability, and Northern literature of this time was typically influenced by the Southern Dynasties.

Shanshui poetry

''Shanshui'' poetry or ''Shanshui shi'' (; lit. "mountains and rivers poetry") refers to the movement in Chinese poetry, poetry, influenced by the ''shan shui'' (landscape) painting style, which became known as ''Shanshui poetry'', or "landscape p ...

also became prominent in Six Dynasties poetry.

Levant

Ancient literature of the Levant was written in the

Northwest Semitic languages

Northwest Semitic is a division of the Semitic languages comprising the indigenous languages of the Levant. It emerged from Proto-Semitic in the Early Bronze Age. It is first attested in proper names identified as Amorite in the Middle Bronze Age ...

, a language group that contains the

Aramaic language

The Aramaic languages, short Aramaic ( syc, ܐܪܡܝܐ, Arāmāyā; oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; tmr, אֲרָמִית), are a language family containing many varieties (languages and dialects) that originated i ...

, as well as the

Canaanite languages

The Canaanite languages, or Canaanite dialects, are one of the three subgroups of the Northwest Semitic languages, the others being Aramaic and Ugaritic, all originating in the Levant and Mesopotamia. They are attested in Canaanite inscriptio ...

such as

Phoenician and

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

. A corpus of

Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the society and history of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occ ...

(or "Northwest Semitic inscriptions") are the primary extra-Biblical source for the writings of the ancient

Phoenicians

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their hist ...

,

Hebrews

The terms ''Hebrews'' (Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and ...

and

Arameans

The Arameans ( oar, 𐤀𐤓𐤌𐤉𐤀; arc, 𐡀𐡓𐡌𐡉𐡀; syc, ܐܪ̈ܡܝܐ, Ārāmāyē) were an ancient Semitic-speaking people in the Near East, first recorded in historical sources from the late 12th century BCE. The Aramean ...

. These inscriptions occur on stone slabs, pottery

ostraca

An ostracon (Greek: ''ostrakon'', plural ''ostraka'') is a piece of pottery, usually broken off from a vase or other earthenware vessel. In an archaeological or epigraphical context, ''ostraca'' refer to sherds or even small pieces of sto ...

, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts.

The books that constitute the

Hebrew Bible

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh (;["Tanach"](_blank)

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. Hebrew: ''Tān ...

developed over roughly a millennium, with the oldest texts originating from about the eleventh or tenth centuries BCE. They are edited works, being collections of various sources intricately and carefully woven together. The Old Testament was compiled and edited by

various authors The expression "various authors" is used to credit creative works which are the result of a collaboration. In English it is more common to describe the authors of such a compilation collectively, for example by saying for what occasion the texts wer ...

over a period of centuries, with many scholars concluding that the Hebrew canon was

solidified by about the 3rd century BC.

[Philip R. Davies in ''The Canon Debate'', page 50: "With many other scholars, I conclude that the fixing of a canonical list was almost certainly the achievement of the ]Hasmonean dynasty

The Hasmonean dynasty (; he, ''Ḥašmōnaʾīm'') was a ruling dynasty of Judea and surrounding regions during classical antiquity, from BCE to 37 BCE. Between and BCE the dynasty ruled Judea semi-autonomously in the Seleucid Empire, an ...

." The

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

was an additional collection of books that supplemented the Hebrew Bible, consisting of the

gospels that described

Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

and the

epistles

An epistle (; el, ἐπιστολή, ''epistolē,'' "letter") is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part ...

written by notable figures of early

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

.

Classical antiquity

Ancient Greece

Early Greek literature was composed in

dactylic hexameter

Dactylic hexameter (also known as heroic hexameter and the meter of epic) is a form of meter or rhythmic scheme frequently used in Ancient Greek and Latin poetry. The scheme of the hexameter is usually as follows (writing – for a long syllable, ...

.

Homer

Homer (; grc, Ὅμηρος , ''Hómēros'') (born ) was a Greek poet who is credited as the author of the '' Iliad'' and the '' Odyssey'', two epic poems that are foundational works of ancient Greek literature. Homer is considered one of ...

is credited with the codification of epic poetry in Ancient Greece with the ''

Iliad

The ''Iliad'' (; grc, Ἰλιάς, Iliás, ; "a poem about Ilium") is one of two major ancient Greek epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by modern audiences. As with the '' Odys ...

'' and the ''

Odyssey

The ''Odyssey'' (; grc, Ὀδύσσεια, Odýsseia, ) is one of two major Ancient Greek literature, ancient Greek Epic poetry, epic poems attributed to Homer. It is one of the oldest extant works of literature still widely read by moder ...

.''

Hesiod

Hesiod (; grc-gre, Ἡσίοδος ''Hēsíodos'') was an ancient Greek poet generally thought to have been active between 750 and 650 BC, around the same time as Homer. He is generally regarded by western authors as 'the first written poet i ...

is credited with developing a literary tradition of poetry derived from catalogues and genealogies, such as the ''

Megala Erga

__NOTOC__

The "Megala Erga" ( grc, Μέγαλα Ἔργα), or "Great Works", is a now fragmentary didactic poem that was attributed to the Greek oral poet Hesiod during antiquity. Only two brief direct quotations can be attributed to the work with ...

'' and the ''

Theogony

The ''Theogony'' (, , , i.e. "the genealogy or birth of the gods") is a poem by Hesiod (8th–7th century BC) describing the origins and genealogies of the Greek gods, composed . It is written in the Epic dialect of Ancient Greek and contain ...

''. Notable writers of religious literature also held similar prominence at the time, but these works have since been lost. Notable among later Greek poets was

Sappho

Sappho (; el, Σαπφώ ''Sapphō'' ; Aeolic Greek ''Psápphō''; c. 630 – c. 570 BC) was an Archaic Greek poet from Eresos or Mytilene on the island of Lesbos. Sappho is known for her lyric poetry, written to be sung while accompanied ...

, who contributed to the development of

lyric poetry

Modern lyric poetry is a formal type of poetry which expresses personal emotions or feelings, typically spoken in the first person.

It is not equivalent to song lyrics, though song lyrics are often in the lyric mode, and it is also ''not'' equi ...

and was widely popular in antiquity.

Ancient Greek plays originate from the

chorus plays of

Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Greece, largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh List ...

in the 6th century BC as a tradition to honor

Dionysus

In ancient Greek religion and myth, Dionysus (; grc, Διόνυσος ) is the god of the grape-harvest, winemaking, orchards and fruit, vegetation, fertility, insanity, ritual madness, religious ecstasy, festivity, and theatre. The Romans ...

, the god of theater and wine. Greek plays came to be associated with "elaborate costumes, complex choreography, scenic architecture, and the mask". They were often structured as a

tetralogy in which three tragedies were followed by a

satyr play

The satyr play is a form of Attic theatre performance related to both comedy and tragedy. It preserves theatrical elements of dialogue, actors speaking verse, a chorus that dances and sings, masks and costumes. Its relationship to tragedy is stron ...

.

Aeschylus

Aeschylus (, ; grc-gre, Αἰσχύλος ; c. 525/524 – c. 456/455 BC) was an ancient Greek tragedian, and is often described as the father of tragedy. Academic knowledge of the genre begins with his work, and understanding of earlier Gree ...

,

Sophocles

Sophocles (; grc, Σοφοκλῆς, , Sophoklễs; 497/6 – winter 406/5 BC)Sommerstein (2002), p. 41. is one of three ancient Greek tragedians, at least one of whose plays has survived in full. His first plays were written later than, or c ...

, and

Euripides

Euripides (; grc, Εὐριπίδης, Eurīpídēs, ; ) was a tragedian of classical Athens. Along with Aeschylus and Sophocles, he is one of the three ancient Greek tragedians for whom any plays have survived in full. Some ancient scholars ...

were known for their

tragedies, while

Aristophanes

Aristophanes (; grc, Ἀριστοφάνης, ; c. 446 – c. 386 BC), son of Philippus, of the deme Kydathenaion ( la, Cydathenaeum), was a comic playwright or comedy-writer of ancient Athens and a poet of Old Attic Comedy. Eleven of his fo ...

and

Menander

Menander (; grc-gre, Μένανδρος ''Menandros''; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy. He wrote 108 comedies and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times. His re ...

were known for their

comedies. Sophocles is most well known for his play ''

Oedipus Rex

''Oedipus Rex'', also known by its Greek title, ''Oedipus Tyrannus'' ( grc, Οἰδίπους Τύραννος, ), or ''Oedipus the King'', is an Athenian tragedy by Sophocles that was first performed around 429 BC. Originally, to the ancient Gr ...

'', which established an early example of literary

irony.

Ancient Greek philosophy

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

was developed as the foundation of

Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The wo ...

.

Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded ...

was the first person in recorded history to engage in Western philosophy. The Ancient Greek philosophical literature was advanced by

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institutio ...

, who incorporated philosophical debates into dialogues with

Socratic questioning

Socratic questioning (or Socratic maieutics) was named after Socrates. He used an educational method that focused on discovering answers by asking questions from his students. According to Plato, who was one of his students, Socrates believed t ...

.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

, Plato's student, wrote dozens of works on many scientific disciplines. Aristotle also developed early

literary criticism and

literary theory

Literary theory is the systematic study of the nature of literature and of the methods for literary analysis. Culler 1997, p.1 Since the 19th century, literary scholarship includes literary theory and considerations of intellectual history, m ...

in his ''

Poetics

Poetics is the theory of structure, form, and discourse within literature, and, in particular, within poetry.

History

The term ''poetics'' derives from the Ancient Greek ποιητικός ''poietikos'' "pertaining to poetry"; also "creative" an ...

.''

Ancient Rome

In the

Roman Republic

The Roman Republic ( la, Res publica Romana ) was a form of government of Rome and the era of the classical Roman civilization when it was run through public representation of the Roman people. Beginning with the overthrow of the Roman Kingd ...

, literature took the form of tragedy, comedy, epic, and historical.

Livius Andronicus

Lucius Livius Andronicus (; el, Λούκιος Λίβιος Ανδρόνικος; c. 284 – c. 204 BC) was a Greco-Roman dramatist and epic poet of the Old Latin period during the Roman Republic. He began as an educator in the service of a no ...

is recognized as the originator of literature in the Latin language, and due to Rome's influence, the development of Latin literature often extended beyond the traditional boundaries of Rome.

Plautus

Titus Maccius Plautus (; c. 254 – 184 BC), commonly known as Plautus, was a Roman playwright of the Old Latin period. His comedies are the earliest Latin literary works to have survived in their entirety. He wrote Palliata comoedia, the ...

was an influential playwright known for his comedies that emphasized humor and

popular culture

Popular culture (also called mass culture or pop culture) is generally recognized by members of a society as a set of practices, beliefs, artistic output (also known as, popular art or mass art) and objects that are dominant or prevalent in ...

. The late republic saw the rise of

Augustan literature and

Classical Latin

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a literary standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used from 75 BC to the 3rd century AD, when it developed into Late Latin. In some later pe ...

, which was primarily prose and included the works of

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the est ...

and

Sallust

Gaius Sallustius Crispus, usually anglicised as Sallust (; 86 – ), was a Roman historian and politician from an Italian plebeian family. Probably born at Amiternum in the country of the Sabines, Sallust became during the 50s BC a partisan ...

. Upon the formation of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

, political commentary declined and prose went out of favor to be replaced by poetry. Poets such as

Virgil

Publius Vergilius Maro (; traditional dates 15 October 7021 September 19 BC), usually called Virgil or Vergil ( ) in English, was an ancient Roman poet of the Augustan period. He composed three of the most famous poems in Latin literature: t ...

,

Horace

Quintus Horatius Flaccus (; 8 December 65 – 27 November 8 BC), known in the English-speaking world as Horace (), was the leading Roman lyric poet during the time of Augustus (also known as Octavian). The rhetorician Quintilian regarded his ...

,

Propertius

Sextus Propertius was a Latin elegiac poet of the Augustan age. He was born around 50–45 BC in Assisium and died shortly after 15 BC.

Propertius' surviving work comprises four books of '' Elegies'' ('). He was a friend of the poets Gallu ...

, and

Ovid

Pūblius Ovidius Nāsō (; 20 March 43 BC – 17/18 AD), known in English as Ovid ( ), was a Roman poet who lived during the reign of Augustus. He was a contemporary of the older Virgil and Horace, with whom he is often ranked as one of the ...

are recognized as bringing about the Golden Age of Latin literature. Virgil's epic poem the ''

Aeneid

The ''Aeneid'' ( ; la, Aenē̆is or ) is a Latin Epic poetry, epic poem, written by Virgil between 29 and 19 BC, that tells the legendary story of Aeneas, a Troy, Trojan who fled the Trojan_War#Sack_of_Troy, fall of Troy and travelled to ...

'' closely followed the formula established by Homer.

Prominent Latin authors that lived during the early empire included

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ...

,

Seneca the Younger

Lucius Annaeus Seneca the Younger (; 65 AD), usually known mononymously as Seneca, was a Stoicism, Stoic philosopher of Ancient Rome, a statesman, dramatist, and, in one work, satirist, from the post-Augustan age of Latin literature.

Seneca was ...

, and Emperor

Marcus Aurelius

Marcus Aurelius Antoninus (Latin: áːɾkus̠ auɾέːli.us̠ antɔ́ːni.us̠ English: ; 26 April 121 – 17 March 180) was Roman emperor from 161 to 180 AD and a Stoic philosopher. He was the last of the rulers known as the Five Good ...

. As the Roman Empire grew, Latin literature increasingly came from Spain and Northern Africa. Historical works of the early empire included the epic ''

Pharsalia

''De Bello Civili'' (; ''On the Civil War''), more commonly referred to as the ''Pharsalia'', is a Roman epic poem written by the poet Lucan, detailing the civil war between Julius Caesar and the forces of the Roman Senate led by Pompey the Gr ...

'' by

Lucan

Marcus Annaeus Lucanus (3 November 39 AD – 30 April 65 AD), better known in English as Lucan (), was a Roman poet, born in Corduba (modern-day Córdoba), in Hispania Baetica. He is regarded as one of the outstanding figures of the Imperial ...

, which followed

Caesar's civil war

Caesar's civil war (49–45 BC) was one of the last politico-military conflicts of the Roman Republic before its reorganization into the Roman Empire. It began as a series of political and military confrontations between Gaius Julius Caesar ...

, and the

''Annals'' of

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

, which recorded the events of the first century. ''

The Golden Ass

The ''Metamorphoses'' of Apuleius, which Augustine of Hippo referred to as ''The Golden Ass'' (''Asinus aureus''), is the only ancient Roman novel in Latin to survive in its entirety.

The protagonist of the novel is Lucius. At the end of the n ...

'' by

Apuleius

Apuleius (; also called Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis; c. 124 – after 170) was a Numidian Latin-language prose writer, Platonist philosopher and rhetorician. He lived in the Roman province of Numidia, in the Berber city of Madauros, modern- ...

was written in the later Empire and is possibly the world's oldest novel. The adoption of

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesu ...

in the Roman Empire became apparent in Latin literature, most notably in the

confessional writing Confessional Writing is a literary style and genre that developed in American writing schools following the Second World War. A prominent mode of confessional writing is confessional poetry, which emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. Confessional writin ...

of

Augustine of Hippo

Augustine of Hippo ( , ; la, Aurelius Augustinus Hipponensis; 13 November 354 – 28 August 430), also known as Saint Augustine, was a theologian and philosopher of Berber origin and the bishop of Hippo Regius in Numidia, Roman North A ...

, such as the ''

Confessions''.

Ancient India

Knowledge traditions in India handed down philosophical gleanings and theological concepts through the two traditions of

Shruti and

Smriti

''Smriti'' ( sa, स्मृति, IAST: '), literally "that which is remembered" are a body of Hindu texts usually attributed to an author, traditionally written down, in contrast to Śrutis (the Vedic literature) considered authorless, t ...

, meaning ''that which is learnt'' and ''that which is experienced'', which included the

Vedas

upright=1.2, The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the '' Atharvaveda''.

The Vedas (, , ) are a large body of religious texts originating in ancient India. Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute th ...

. It is generally believed that the

Puranas

Purana (; sa, , '; literally meaning "ancient, old"Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, , page 915) is a vast genre of Indian literature about a wide range of topics, particularly about legends an ...

are the earliest philosophical writings in Indian history, although linguistic works on

Sanskrit

Sanskrit (; attributively , ; nominalization, nominally , , ) is a classical language belonging to the Indo-Aryan languages, Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European languages. It arose in South Asia after its predecessor languages had Trans-cul ...

existed earlier than 1000 BC. Puranic works such as the Indian epics:

Ramayana

The ''Rāmāyana'' (; sa, रामायणम्, ) is a Sanskrit epic composed over a period of nearly a millennium, with scholars' estimates for the earliest stage of the text ranging from the 8th to 4th centuries BCE, and later stages e ...

and ''

Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; sa, महाभारतम्, ', ) is one of the two major Sanskrit epics of ancient India in Hinduism, the other being the '' Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the struggle between two groups of cousins in the K ...

'', have influenced countless other works, including Balinese

Kecak and other performances such as shadow puppetry (

wayang

, also known as ( jv, ꦮꦪꦁ, translit=wayang), is a traditional form of puppet theatre play originating from the Indonesian island of Java. refers to the entire dramatic show. Sometimes the leather puppet itself is referred to as . Perfor ...

), and many European works.

Pali

Pali () is a Middle Indo-Aryan liturgical language native to the Indian subcontinent. It is widely studied because it is the language of the Buddhist '' Pāli Canon'' or '' Tipiṭaka'' as well as the sacred language of '' Theravāda'' Bud ...

literature has an important position in the rise of

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

.

Classical Sanskrit literature flowers in the

Maurya and

Gupta period

The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire which existed from the early 4th century CE to late 6th century CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. This period is considered as the Go ...

s, roughly spanning the 2nd century BC to the 8th century AD.

Classical Tamil literature also emerged in the early historic period dating from 300 BC to 300 AD, and is the earliest secular literature of India, mainly dealing with themes such as love and war. The

Gupta period

The Gupta Empire was an ancient Indian empire which existed from the early 4th century CE to late 6th century CE. At its zenith, from approximately 319 to 467 CE, it covered much of the Indian subcontinent. This period is considered as the Go ...

in India sees the flowering of

Sanskrit drama

The term Indian classical drama refers to the tradition of dramatic literature and performance in ancient India. The roots of drama in the Indian subcontinent can be traced back to the Rigveda (1200-1500 BCE), which contains a number of hymns in ...

, classical

Sanskrit poetry

Sanskrit literature broadly comprises all literature in the Sanskrit language. This includes texts composed in the earliest attested descendant of the Proto-Indo-Aryan language known as Vedic Sanskrit, texts in Classical Sanskrit as well as s ...

and the compilation of the

Puranas

Purana (; sa, , '; literally meaning "ancient, old"Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of Literature (1995 Edition), Article on Puranas, , page 915) is a vast genre of Indian literature about a wide range of topics, particularly about legends an ...

.

Post-classical (5th century–15th century)

Medieval Europe

After the fall of Rome (in roughly 476), many of the literary approaches and styles invented by the Greeks and Romans fell out of favor in Europe. In the

millennium

A millennium (plural millennia or millenniums) is a period of one thousand years, sometimes called a kiloannus, kiloannum (ka), or kiloyear (ky). Normally, the word is used specifically for periods of a thousand years that begin at the starting ...

or so that intervened between Rome's fall and the

Florentine Renaissance

The Italian Renaissance ( it, Rinascimento ) was a period in Italian history covering the 15th and 16th centuries. The period is known for the initial development of the broader Renaissance culture that spread across Europe and marked the trans ...

, medieval literature focused more and more on faith and faith-related matters, in part because the works written by the Greeks had not been preserved in Europe, and therefore there were few models of classical literature to learn from and move beyond. Although much had been lost to the ravages of time (and to catastrophe, as in the burning of the Library of Alexandria), many Greek works remained extant: they were preserved and copied carefully by Muslim scribes. What little there was became changed and distorted, with new forms beginning to develop from the distortions. Some of these distorted beginnings of new styles can be seen in the literature generally described as

Matter of Rome

According to the medieval poet Jean Bodel, the Matter of Rome is the literary cycle of Greek and Roman mythology, together with episodes from the history of classical antiquity, focusing on military heroes like Alexander the Great and Julius ...

,

Matter of France

The Matter of France, also known as the Carolingian cycle, is a body of literature and legendary material associated with the history of France, in particular involving Charlemagne and his associates. The cycle springs from the Old French '' chan ...

and

Matter of Britain

The Matter of Britain is the body of medieval literature and legendary material associated with Great Britain and Brittany and the legendary kings and heroes associated with it, particularly King Arthur. It was one of the three great Wester ...

.

Around 400 AD, the ''Prudenti

Psychomachia'' began the tradition of allegorical tales. Poetry flourished, however, in the hands of the

troubadour

A troubadour (, ; oc, trobador ) was a composer and performer of Old Occitan lyric poetry during the High Middle Ages (1100–1350). Since the word ''troubadour'' is etymologically masculine, a female troubadour is usually called a '' trobai ...

s, whose courtly romances and ''

chanson de geste

The ''chanson de geste'' (, from Latin 'deeds, actions accomplished') is a medieval narrative, a type of epic poem that appears at the dawn of French literature. The earliest known poems of this genre date from the late 11th and early 12th ce ...

'' amused and entertained the upper classes who were their patrons. The

First Crusade

The First Crusade (1096–1099) was the first of a series of religious wars, or Crusades, initiated, supported and at times directed by the Latin Church in the medieval period. The objective was the recovery of the Holy Land from Islamic ...

in 1095 also affected literature. For instance the image of the

knight

A knight is a person granted an honorary title of knighthood by a head of state (including the Pope) or representative for service to the monarch, the church or the country, especially in a military capacity. Knighthood finds origins in the G ...

would take on a different significance. The

Islamic

Islam (; ar, ۘالِإسلَام, , ) is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion centred primarily around the Quran, a religious text considered by Muslims to be the direct word of God (or ''Allah'') as it was revealed to Muhammad, the main ...

emphasis on scientific investigation and the preservation of the Greek philosophical writings would also affect European literature.

Hagiographies

A hagiography (; ) is a biography of a saint or an ecclesiastical leader, as well as, by extension, an adulatory and idealized biography of a founder, saint, monk, nun or icon in any of the world's religions. Early Christian hagiographies migh ...

, or "lives of the

saints

In religious belief, a saint is a person who is recognized as having an exceptional degree of holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. However, the use of the term ''saint'' depends on the context and denomination. In Catholic, Eastern Orth ...

", were frequent among early medieval European texts. The writings of

Bede

Bede ( ; ang, Bǣda , ; 672/326 May 735), also known as Saint Bede, The Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable ( la, Beda Venerabilis), was an English monk at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom ...

—''

Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum

The ''Ecclesiastical History of the English People'' ( la, Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum), written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict be ...

''—and others continue the faith-based historical tradition begun by Eusebius in the early 4th century. Between Augustine and ''The Bible'', religious authors had numerous aspects of Christianity that needed further explication and interpretation.

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, more than any other single person, was able to turn

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing th ...

into a kind of science, in part because he was heavily influenced by Aristotle, whose works were returning to Europe in the 13th century. Playwriting essentially ceased, except for the

mystery play

Mystery plays and miracle plays (they are distinguished as two different forms although the terms are often used interchangeably) are among the earliest formally developed plays in medieval Europe. Medieval mystery plays focused on the represe ...

s and the

passion plays that focused heavily on conveying Christian belief to the common people.

Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

continued to be used as a

literary language

A literary language is the form (register) of a language used in written literature, which can be either a nonstandard dialect or a standardized variety of the language. Literary language sometimes is noticeably different from the spoken langu ...

in medieval Europe. Though it was also spoken, it was primarily learned and expressed through literature, and scientific literature was typically written in Latin. Christianity became increasingly prominent in medieval European literature, also written in Latin. Religious literature in other languages proliferated during the 13th century as those who were not educated in Latin sought religious literature that they could understand. Women in particular were not permitted to learn Latin, and an extensive body of religious literature in many languages was written by women at this time.

Medieval England

Early Medieval literature in England was written in

Old English, which is not mutually intelligible with modern English. Works of this time include the epic poem ''

Beowulf

''Beowulf'' (; ang, Bēowulf ) is an Old English Epic poetry, epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 Alliterative verse, alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and List of translations of Beo ...

'' and

Arthurian fantasy based on the legendary character of

King Arthur. Literature in the modern English language began with

Geoffrey Chaucer in the 14th century, known for ''

The Canterbury Tales''.

Medieval Italy

''

The Decameron

''The Decameron'' (; it, label= Italian, Decameron or ''Decamerone'' ), subtitled ''Prince Galehaut'' (Old it, Prencipe Galeotto, links=no ) and sometimes nicknamed ''l'Umana commedia'' ("the Human comedy", as it was Boccaccio that dubbed Da ...

'' by

Giovanni Boccaccio

Giovanni Boccaccio (, , ; 16 June 1313 – 21 December 1375) was an Italian writer, poet, correspondent of Petrarch, and an important Renaissance humanist. Born in the town of Certaldo, he became so well known as a writer that he was som ...

was published in 1351, and it influenced European literature over the following centuries. Its framing device of ten individuals each telling ten stories introduced the term ''

novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) fact ...

'' and inspired later works, including Chaucer's ''Canterbury Tales''.

Islamic world

The most well known

fiction from the Islamic world was ''

The Book of One Thousand and One Nights

''One Thousand and One Nights'' ( ar, أَلْفُ لَيْلَةٍ وَلَيْلَةٌ, italic=yes, ) is a collection of Middle Eastern folk tales compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. It is often known in English as the ''Arabian ...

'' (''Arabian Nights''), which was a compilation of many earlier folk tales told by the

Persian Queen

Scheherazade

Scheherazade () is a major female character and the storyteller in the frame narrative of the Middle Eastern collection of tales known as the ''One Thousand and One Nights''.

Name

According to modern scholarship, the name ''Scheherazade'' deri ...

. The epic took form in the 10th century and reached its final form by the 14th century; the number and type of tales have varied from one manuscript to another.

[John Grant and John Clute, ''The Encyclopedia of Fantasy'', "Arabian fantasy", p. 51 ] All Arabian

fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction involving magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and sometimes inspired by mythology and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy literature and drama ...

tales were often called "Arabian Nights" when translated into

English, regardless of whether they appeared in ''The Book of One Thousand and One Nights'', in any version, and a number of tales are known in Europe as "Arabian Nights" despite existing in no Arabic manuscript.

This epic has been influential in the West since it was translated in the 18th century, first by

Antoine Galland

Antoine Galland (; 4 April 1646 – 17 February 1715) was a French orientalist and archaeologist, most famous as the first European translator of ''One Thousand and One Nights'', which he called '' Les mille et une nuits''. His version of the ta ...

. Many imitations were written, especially in France.

[John Grant and John Clute, ''The Encyclopedia of Fantasy'', "Arabian fantasy", p. 52 ]

Dante Alighieri

Dante Alighieri (; – 14 September 1321), probably baptized Durante di Alighiero degli Alighieri and often referred to as Dante (, ), was an Italian poet, writer and philosopher. His '' Divine Comedy'', originally called (modern Italian: ...

's ''

Divine Comedy

The ''Divine Comedy'' ( it, Divina Commedia ) is an Italian narrative poem by Dante Alighieri, begun 1308 and completed in around 1321, shortly before the author's death. It is widely considered the pre-eminent work in Italian literature a ...

'', considered the greatest epic of

Italian literature

Italian literature is written in the Italian language, particularly within Italy. It may also refer to literature written by Italians or in other languages spoken in Italy, often languages that are closely related to modern Italian, including ...

, derived many features of and episodes about the hereafter directly or indirectly from Arabic works on

Islamic eschatology

Islamic eschatology ( ar, علم آخر الزمان في الإسلام, ) is a field of study in Islam concerning future events that would happen in the end times. It is primarily based on hypothesis and speculations based on sources from ...

: the ''

Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

'' and the ''

Kitab al-Miraj'' (translated into Latin in 1264 or shortly before

[I. Heullant-Donat and M.-A. Polo de Beaulieu, "Histoire d'une traduction," in ''Le Livre de l'échelle de Mahomet'', Latin edition and French translation by Gisèle Besson and Michèle Brossard-Dandré, Collection ''Lettres Gothiques'', Le Livre de Poche, 1991, p. 22 with note 37.] as ''

Liber scalae Machometi

The ''Book of Muḥammad's Ladder'' is a first-person account of the Islamic prophet Muḥammad's night journey ('' isrāʾ'') and ascent to heaven ('' miʿrāj''), translated into Latin (as ) and Old French (as ) from traditional Arabic materials ...

'', "The Book of Muhammad's Ladder") concerning

Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

's ascension to Heaven, and the spiritual writings of

Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

. The

Moors

The term Moor, derived from the ancient Mauri, is an exonym first used by Christian Europeans to designate the Muslim inhabitants of the Maghreb, the Iberian Peninsula, Sicily and Malta during the Middle Ages.

Moors are not a distinct o ...

also had a noticeable influence on the works of

George Peele

George Peele (baptised 25 July 1556 – buried 9 November 1596) was an English translator, poet, and dramatist, who is most noted for his supposed but not universally accepted collaboration with William Shakespeare on the play ''Titus Andronicus ...

and

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

. Some of their works featured Moorish characters, such as Peele's ''

The Battle of Alcazar'' and Shakespeare's ''

The Merchant of Venice

''The Merchant of Venice'' is a play by William Shakespeare, believed to have been written between 1596 and 1598. A merchant in Venice named Antonio defaults on a large loan provided by a Jewish moneylender, Shylock.

Although classified as ...

'', ''

Titus Andronicus

''Titus Andronicus'' is a tragedy by William Shakespeare believed to have been written between 1588 and 1593, probably in collaboration with George Peele. It is thought to be Shakespeare's first tragedy and is often seen as his attempt to emul ...

'' and ''

Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cyp ...

'', which featured a Moorish

Othello

''Othello'' (full title: ''The Tragedy of Othello, the Moor of Venice'') is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare, probably in 1603, set in the contemporary Ottoman–Venetian War (1570–1573) fought for the control of the Island of Cyp ...

as its title character. These works are said to have been inspired by several Moorish

delegation

Delegation is the assignment of authority to another person (normally from a manager to a subordinate) to carry out specific activities. It is the process of distributing and entrusting work to another person,Schermerhorn, J., Davidson, P., Poole ...

s from

Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria ...

to

Elizabethan England

The Elizabethan era is the epoch in the Tudor period of the history of England

England became inhabited more than 800,000 years ago, as the discovery of stone tools and footprints at Happisburgh in Norfolk have indicated.; "Earliest ...

at the beginning of the 17th century.

Arabic literature

Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theo ...

(Abubacer) and

Ibn al-Nafis (1213–1288) were pioneers of the

philosophical novel

Philosophical fiction refers to the class of works of fiction which devote a significant portion of their content to the sort of questions normally addressed in philosophy. These might explore any facet of the human condition, including the fu ...

. Ibn Tufail wrote the first fictional Arabic

novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

''

Hayy ibn Yaqdhan'' (''Philosophus Autodidactus'') as a response to

al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polym ...

's ''

The Incoherence of the Philosophers

''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (تهافت الفلاسفة ''Tahāfut al-Falāsifaʰ'' in Arabic) is the title of a landmark 11th-century work by the Persian theologian Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali and a student o ...

'', and then Ibn al-Nafis also wrote a novel ''

Theologus Autodidactus

''Theologus Autodidactus'' ("The Self-taught Theologian"), originally titled ''The Treatise of Kāmil on the Prophet's Biography'' ( ar, الرسالة الكاملية في السيرة النبوية), also known as ''Risālat Fādil ibn Nātiq'' ...

'' as a response to Ibn Tufail's ''Philosophus Autodidactus''. Both of these narratives had

protagonist

A protagonist () is the main character of a story. The protagonist makes key decisions that affect the plot, primarily influencing the story and propelling it forward, and is often the character who faces the most significant obstacles. If a st ...

s (Hayy in ''Philosophus Autodidactus'' and Kamil in ''Theologus Autodidactus'') who were

autodidactic feral child

A feral child (also called wild child) is a young individual who has lived isolated from human contact from a very young age, with little or no experience of human care, social behavior, or language. The term is used to refer to children who h ...

ren living in seclusion on a

desert island

A desert island, deserted island, or uninhabited island, is an island, islet or atoll that is not permanently populated by humans. Uninhabited islands are often depicted in films or stories about shipwrecked people, and are also used as stereo ...

, both being the earliest examples of a desert island story. However, while Hayy lives alone with animals on the desert island for the rest of the story in ''Philosophus Autodidactus'', the story of Kamil extends beyond the desert island setting in ''Theologus Autodidactus'', developing into the earliest known

coming of age plot and eventually becoming the first example of a

science fiction

Science fiction (sometimes shortened to Sci-Fi or SF) is a genre of speculative fiction which typically deals with imagination, imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, Paral ...

novel.

''Theologus Autodidactus'' deals with various science fiction elements such as

spontaneous generation