Libya History-related Lists on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the

Maghreb

The Maghreb (; ar, الْمَغْرِب, al-Maghrib, lit=the west), also known as the Arab Maghreb ( ar, المغرب العربي) and Northwest Africa, is the western part of North Africa and the Arab world. The region includes Algeria, ...

region in North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in t ...

. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ...

to the north, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

to the east, Sudan to the southeast, Chad

Chad (; ar, تشاد , ; french: Tchad, ), officially the Republic of Chad, '; ) is a landlocked country at the crossroads of North and Central Africa. It is bordered by Libya to the north, Sudan to the east, the Central African Repub ...

to the south, Niger

)

, official_languages =

, languages_type = National languagesthe southwest,

The origin of the name "Libya" first appeared in an inscription of

The origin of the name "Libya" first appeared in an inscription of

The coastal plain of Libya was inhabited by

The coastal plain of Libya was inhabited by

Under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, the

Under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, the

After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510, and its handover to the

After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510, and its handover to the  Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer

Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer  In the early 19th century war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the

In the early 19th century war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the

After the

After the  In 1934, Italy combined

In 1934, Italy combined

On 24 December 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King

On 24 December 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King  On 1 September 1969, a group of rebel military officers led by

On 1 September 1969, a group of rebel military officers led by  In February 1977, Libya started delivering military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan conflict began in earnest when Libya's support of rebel forces in northern Chad escalated into an

In February 1977, Libya started delivering military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan conflict began in earnest when Libya's support of rebel forces in northern Chad escalated into an

Organizations of the United Nations, including

Organizations of the United Nations, including

Following the defeat of loyalist forces, Libya was torn among numerous rival, armed militias affiliated with distinct regions, cities and tribes, while the central government had been weak and unable to effectively exert its authority over the country. Competing militias pitted themselves against each other in a political struggle between Islamist politicians and their opponents. On 7 July 2012, Libyans held their first parliamentary elections since the end of the former regime. On 8 August, the

Following the defeat of loyalist forces, Libya was torn among numerous rival, armed militias affiliated with distinct regions, cities and tribes, while the central government had been weak and unable to effectively exert its authority over the country. Competing militias pitted themselves against each other in a political struggle between Islamist politicians and their opponents. On 7 July 2012, Libyans held their first parliamentary elections since the end of the former regime. On 8 August, the  In June 2014, elections were held to the

In June 2014, elections were held to the  In January 2015, meetings were held with the aim to find a peaceful agreement between the rival parties in Libya. The so-called Geneva-Ghadames talks were supposed to bring the GNC and the Tobruk government together at one table to find a solution of the internal conflict. However, the GNC actually never participated, a sign that internal division not only affected the "Tobruk Camp", but also the "Tripoli Camp". Meanwhile, terrorism within Libya steadily increased, also affecting neighbouring countries. The terrorist attack against the Bardo Museum in

In January 2015, meetings were held with the aim to find a peaceful agreement between the rival parties in Libya. The so-called Geneva-Ghadames talks were supposed to bring the GNC and the Tobruk government together at one table to find a solution of the internal conflict. However, the GNC actually never participated, a sign that internal division not only affected the "Tobruk Camp", but also the "Tripoli Camp". Meanwhile, terrorism within Libya steadily increased, also affecting neighbouring countries. The terrorist attack against the Bardo Museum in

Libya extends over , making it the 16th largest nation in the world by size. Libya is bound to the north by the

Libya extends over , making it the 16th largest nation in the world by size. Libya is bound to the north by the

The

The

Historically, the area of Libya was considered three provinces (or states),

Historically, the area of Libya was considered three provinces (or states),

Observer

: the eastern coast, Jabal Al-Akhdar, Al-Hizam, Benghazi, Al-Wahat, Al-Kufra, Al-Khaleej, Al-Margab, Tripoli, Al-Jafara, Al-Zawiya, West Coast, Gheryan, Zintan, Nalut, Sabha, Al-Wadi, and Murzuq Basin.

The Libyan economy depends primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which account for over half of GDP and 97% of exports. Libya holds the largest proven oil reserves in Africa and is an important contributor to the global supply of light,

The Libyan economy depends primarily upon revenues from the oil sector, which account for over half of GDP and 97% of exports. Libya holds the largest proven oil reserves in Africa and is an important contributor to the global supply of light,  Libya imports up to 90% of its cereal consumption requirements, and imports of wheat in 2012/13 was estimated at 1 million tonnes. The 2012 wheat production was estimated at 200,000 tonnes. The government hopes to increase food production to 800,000 tonnes of cereals by 2020. However, natural and environmental conditions limit Libya's agricultural production potential. Before 1958, agriculture was the country's main source of revenue, making up about 30% of GDP. With the discovery of oil in 1958, the size of the agriculture sector declined rapidly, comprising less than 5% GDP by 2005.

The country joined

Libya imports up to 90% of its cereal consumption requirements, and imports of wheat in 2012/13 was estimated at 1 million tonnes. The 2012 wheat production was estimated at 200,000 tonnes. The government hopes to increase food production to 800,000 tonnes of cereals by 2020. However, natural and environmental conditions limit Libya's agricultural production potential. Before 1958, agriculture was the country's main source of revenue, making up about 30% of GDP. With the discovery of oil in 1958, the size of the agriculture sector declined rapidly, comprising less than 5% GDP by 2005.

The country joined  In the early 2000s officials of the Jamahiriya era carried out economic reforms to reintegrate Libya into the global economy. UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003, and Libya announced in December 2003 that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction. Other steps have included applying for membership of the

In the early 2000s officials of the Jamahiriya era carried out economic reforms to reintegrate Libya into the global economy. UN sanctions were lifted in September 2003, and Libya announced in December 2003 that it would abandon programs to build weapons of mass destruction. Other steps have included applying for membership of the

Libya is a large country with a relatively small population, and the population is concentrated very narrowly along the coast. Population density is about in the two northern regions of

Libya is a large country with a relatively small population, and the population is concentrated very narrowly along the coast. Population density is about in the two northern regions of

Libya's population includes 1.7 million students, over 270,000 of whom study at the tertiary level. Basic education in Libya is free for all citizens, and is compulsory up to the

Libya's population includes 1.7 million students, over 270,000 of whom study at the tertiary level. Basic education in Libya is free for all citizens, and is compulsory up to the

The original inhabitants of Libya belonged predominantly to various Berber ethnic groups; however, the long series of foreign invasions and migrations – particularly by

The original inhabitants of Libya belonged predominantly to various Berber ethnic groups; however, the long series of foreign invasions and migrations – particularly by

About 97% of the population in Libya are

About 97% of the population in Libya are

Many Arabic speaking Libyans consider themselves as part of a wider Arab community. This was strengthened by the spread of Pan-Arabism in the mid-20th century, and their reach to power in Libya where they instituted Arabic as the only official language of the state. Under Gaddafi's rule, the teaching and even use of indigenous

Many Arabic speaking Libyans consider themselves as part of a wider Arab community. This was strengthened by the spread of Pan-Arabism in the mid-20th century, and their reach to power in Libya where they instituted Arabic as the only official language of the state. Under Gaddafi's rule, the teaching and even use of indigenous

Libyan cuisine is a mixture of the different Italian, Bedouin and traditional Arab culinary influences. Pasta is the staple food in the Western side of Libya, whereas rice is generally the staple food in the east.

Common Libyan foods include several variations of red (tomato) sauce based pasta dishes (similar to the Italian Sugo all'arrabbiata dish); rice, usually served with lamb or chicken (typically stewed, fried, grilled, or boiled in-sauce); and

Libyan cuisine is a mixture of the different Italian, Bedouin and traditional Arab culinary influences. Pasta is the staple food in the Western side of Libya, whereas rice is generally the staple food in the east.

Common Libyan foods include several variations of red (tomato) sauce based pasta dishes (similar to the Italian Sugo all'arrabbiata dish); rice, usually served with lamb or chicken (typically stewed, fried, grilled, or boiled in-sauce); and

Libya

. ''

Libya profile

from the

Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Algiers

, coordinates =

, largest_city = capital

, religi ...

to the west, and Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

to the northwest. Libya is made of three historical regions: Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

, Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

, and Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

. With an area of almost 700,000 square miles (1.8 million km2), it is the fourth-largest country in Africa

Africa is the world's second-largest and second-most populous continent, after Asia in both cases. At about 30.3 million km2 (11.7 million square miles) including adjacent islands, it covers 6% of Earth's total surface area ...

and the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

, and the 16th-largest in the world. Libya has the 10th-largest proven oil reserves in the world. The largest city and capital, Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

, is located in western Libya and contains over three million of Libya's seven million people.

Libya has been inhabited by Berbers since the late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

as descendants from Iberomaurusian

The Iberomaurusian is a backed bladelet lithic industry found near the coasts of Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia. It is also known from a single major site in Libya, the Haua Fteah, where the industry is locally known as the Eastern Oranian.The " ...

and Capsian cultures. In ancient times, the Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns established city-states and trading posts in western Libya, while more recently the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

controlled the northern coastline of Libya. Parts of Libya were variously ruled by Carthaginians

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

, Persians

The Persians are an Iranian ethnic group who comprise over half of the population of Iran. They share a common cultural system and are native speakers of the Persian language as well as of the languages that are closely related to Persian.

...

, Egyptians and Macedonians before the entire region becoming a part of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post- Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Medite ...

. Libya was an early center of Christianity. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

, the area of Libya was mostly occupied by the Vandals

The Vandals were a Germanic people who first inhabited what is now southern Poland. They established Vandal kingdoms on the Iberian Peninsula, Mediterranean islands, and North Africa in the fifth century.

The Vandals migrated to the area be ...

until the 7th century when invasions brought Islam to the region. In the 16th century, the Spanish Empire

The Spanish Empire ( es, link=no, Imperio español), also known as the Hispanic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Hispánica) or the Catholic Monarchy ( es, link=no, Monarquía Católica) was a colonial empire governed by Spain and its prede ...

and the Knights of St John occupied Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

until Ottoman rule began in 1551. Libya was involved in the Barbary Wars

The Barbary Wars were a series of two wars fought by the United States, Sweden, and the Kingdom of Sicily against the Barbary states (including Tunis, Algiers, and Tripoli) of North Africa in the early 19th century. Sweden had been at war wi ...

of the 18th and 19th centuries. Ottoman rule continued until the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result ...

, which resulted in the Italian occupation of Libya and the establishment of two colonies, Italian Tripolitania and Italian Cyrenaica

Italian Cyrenaica (; ) was an Italian colony, located in present-day eastern Libya, that existed from 1911 to 1934. It was part of the territory conquered from the Ottoman Empire during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911, alongside Italian Tripol ...

(1911–1934), later unified in the Italian Libya

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica a ...

colony from 1934 to 1943.

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

, Libya was an area of warfare in the North African Campaign. The Italian population then went into decline. Libya became independent as a kingdom in 1951. A bloodless military coup in 1969, initiated by a coalition led by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by '' The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spelli ...

, overthrew King Idris I and created a republic. Gaddafi was often described by critics as a dictator

A dictator is a political leader who possesses absolute power. A dictatorship is a state ruled by one dictator or by a small clique. The word originated as the title of a Roman dictator elected by the Roman Senate to rule the republic in ti ...

, and was one of the world's longest serving non-royal leaders, ruling for 42 years. He ruled

''Ruled'' is the fifth full-length LP by The Giraffes. Drums, bass and principal guitar tracks recorded at The Bunker in Brooklyn, NY. Vocals and additional guitars recorded at Strangeweather in Brooklyn, NY. Mixed at Studio G in Brooklyn, NY ...

until being overthrown and killed in the 2011 Libyan Civil War

The First Libyan Civil War was an armed conflict in 2011 in the North African country of Libya that was fought between forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and rebel groups that were seeking to oust his government. It erupted with the Lib ...

during the wider Arab Spring

The Arab Spring ( ar, الربيع العربي) was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in Tunisia in response to corruption and econom ...

, with authority transferred to the National Transitional Council

The National Transitional Council of Libya ( ar, المجلس الوطني الإنتقالي '), sometimes known as the Transitional National Council, was the ''de facto'' government of Libya for a period during and after the Libyan Civil War ...

then to the elected General National Congress. By 2014 two rival authorities claimed to govern Libya, which led to a second civil war, with parts of Libya split between the Tobruk and Tripoli-based governments as well as various tribal and Islamist militias. The two main warring sides signed a permanent ceasefire in 2020, and a unity government

A national unity government, government of national unity (GNU), or national union government is a broad coalition government consisting of all parties (or all major parties) in the legislature, usually formed during a time of war or other na ...

took authority to plan for democratic elections, however political rivalries continue to delay this.

Libya is a member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be a centre for harmonizi ...

, the Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 120 countries that are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. After the United Nations, it is the largest grouping of states worldwide.

The movement originated in the aftermath ...

, the African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of member states of the African Union, 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling fo ...

, the Arab League, the OIC and OPEC

The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC, ) is a cartel of countries. Founded on 14 September 1960 in Baghdad by the first five members (Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia, and Venezuela), it has, since 1965, been headquart ...

. The country's official religion is Islam, with 96.6% of the Libyan population being Sunni Muslims

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word ''Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

.

Etymology

The origin of the name "Libya" first appeared in an inscription of

The origin of the name "Libya" first appeared in an inscription of Ramesses II

Ramesses II ( egy, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is often regarded a ...

, written as '' rbw'' in hieroglyphic. The name derives from a generalized identity given to a large confederacy of ancient east "Libyan" berbers, African people(s) and tribes who lived around the lush regions of Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

and Marmarica. An army of 40,000 men and a confederacy of tribes known as "Great Chiefs of the Libu

The Libu ( egy, rbw; also transcribed Rebu, Lebu, Lbou, Libou) were an Ancient Libyan tribe of Berber origin, from which the name ''Libya'' derives.

Early history

Their occupation of Ancient Libya is first attested in Egyptian language text ...

" were led by King Meryey who fought a war against pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until th ...

Merneptah

Merneptah or Merenptah (reigned July or August 1213 BC – May 2, 1203 BC) was the fourth pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Ancient Egypt. He ruled Egypt for almost ten years, from late July or early August 1213 BC until his death on May 2, ...

in year 5 (1208 BCE). This conflict was mentioned in the Great Karnak Inscription in the western delta during the 5th and 6th years of his reign and resulted in a defeat for Meryey. According to the Great Karnak Inscription, the military alliance comprised the Meshwesh

The Meshwesh (often abbreviated in ancient Egyptian as Ma) was an ancient Libyan Berber tribe, along with other groups like Libu and Tehenou/Tehenu.

Early records of the Meshwesh date back to the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt from the reign of ...

, the Lukka, and the "Sea Peoples" known as the Ekwesh, Teresh, Shekelesh, and the Sherden

The Sherden ( Egyptian: ''šrdn'', ''šꜣrdꜣnꜣ'' or ''šꜣrdynꜣ'', Ugaritic: ''šrdnn(m)'' and ''trtn(m)'', possibly Akkadian: ''še-er-ta-an-nu''; also glossed “Shardana” or “Sherdanu”) are one of the several ethnic groups the Sea ...

.

The Great karnak inscription reads:

'

The modern name of "Libya" is an evolution of the "''Libu''" or "''Libúē''" name (from Greek ''Λιβύη, Libyē''), generally encompassing the people of Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

and Marmarica. The ''"Libúē"'' or ''"libu"'' name likely came to be used in the classical world as an identity for the natives of the North African region. The name was revived in 1934 for Italian Libya

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica a ...

from the ancient Greek

Ancient Greek includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Dark Ages (), the Archaic p ...

('). It was intended to supplant terms applied to Ottoman Tripolitania

The coastal region of what is today Libya was ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1912. First, from 1551 to 1864, as the Eyalet of Tripolitania ( ota, ایالت طرابلس غرب ''Eyālet-i Trâblus Gârb'') or ''Bey and Subjects of Tri ...

, the coastal region of what is today Libya, having been ruled by the Ottoman Empire from 1551 to 1911 as the Eyalet of Tripolitania. The name "Libya" was brought back into use in 1903 by Italian geographer Federico Minutilli."Bibliografia della Libia"; Bertarelli, p. 177.

Libya gained independence in 1951 as the United Libyan Kingdom ( '), changing its name to the Kingdom of Libya ( '), literally "Libyan Kingdom", in 1963. Following a coup d'état led by Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by '' The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spelli ...

in 1969, the name of the state was changed to the Libyan Arab Republic ( '). The official name was "Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" from 1977 to 1986 (), and "Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya" (, ' ) from 1986 to 2011.

The National Transitional Council

The National Transitional Council of Libya ( ar, المجلس الوطني الإنتقالي '), sometimes known as the Transitional National Council, was the ''de facto'' government of Libya for a period during and after the Libyan Civil War ...

, established in 2011, referred to the state as simply "Libya". The UN formally recognized the country as "Libya" in September 2011 based on a request from the Permanent Mission of Libya citing the Libyan interim Constitutional Declaration of 3 August 2011. In November 2011, the ISO 3166-1

ISO 3166-1 (''Codes for the representation of names of countries and their subdivisions – Part 1: Country codes'') is a standard defining codes for the names of countries, dependent territories, and special areas of geographical interest. It ...

was altered to reflect the new country name "Libya" in English, ''"Libye (la)"'' in French.

In December 2017 the Permanent Mission of Libya to the United Nations informed the United Nations that the country's official name was henceforth the "State of Libya"; "Libya" remained the official short form, and the country continued to be listed under "L" in alphabetical lists.

History

Ancient Libya

The coastal plain of Libya was inhabited by

The coastal plain of Libya was inhabited by Neolithic

The Neolithic period, or New Stone Age, is an Old World archaeological period and the final division of the Stone Age. It saw the Neolithic Revolution, a wide-ranging set of developments that appear to have arisen independently in several part ...

peoples from as early as 8000 BC. The Afroasiatic

The Afroasiatic languages (or Afro-Asiatic), also known as Hamito-Semitic, or Semito-Hamitic, and sometimes also as Afrasian, Erythraean or Lisramic, are a language family of about 300 languages that are spoken predominantly in the geographic su ...

ancestors of the Berber people

, image = File:Berber_flag.svg

, caption = The Berber flag, Berber ethnic flag

, population = 36 million

, region1 = Morocco

, pop1 = 14 million to 18 million

, region2 = Algeria

, p ...

are assumed to have spread into the area by the Late Bronze Age

The Bronze Age is a historic period, lasting approximately from 3300 BC to 1200 BC, characterized by the use of bronze, the presence of writing in some areas, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second pri ...

. The earliest known name of such a tribe was the Garamantes, based in Germa. The Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their his ...

ns were the first to establish trading posts in Libya. By the 5th century BC, the greatest of the Phoenician colonies, Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the clas ...

, had extended its hegemony

Hegemony (, , ) is the political, economic, and military predominance of one state over other states. In Ancient Greece (8th BC – AD 6th ), hegemony denoted the politico-military dominance of the ''hegemon'' city-state over other city-states. ...

across much of North Africa, where a distinctive civilization, known as Punic

The Punic people, or western Phoenicians, were a Semitic people in the Western Mediterranean who migrated from Tyre, Phoenicia to North Africa during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term ''Punic'' – the Latin equivalent of the ...

, came into being.

In 630 BC, the ancient Greeks

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

colonized the area around Barca in Eastern Libya and founded the city of Cyrene. Within 200 years, four more important Greek cities were established in the area that became known as Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

.

In 525 BC the Persian army of Cambyses II

Cambyses II ( peo, 𐎣𐎲𐎢𐎪𐎡𐎹 ''Kabūjiya'') was the second King of Kings of the Achaemenid Empire from 530 to 522 BC. He was the son and successor of Cyrus the Great () and his mother was Cassandane.

Before his accession, Cambyse ...

overran Cyrenaica, which for the next two centuries remained under Persian or Egyptian rule. Alexander the Great

Alexander III of Macedon ( grc, Ἀλέξανδρος, Alexandros; 20/21 July 356 BC – 10/11 June 323 BC), commonly known as Alexander the Great, was a king of the ancient Greek kingdom of Macedon. He succeeded his father Philip II to ...

was greeted by the Greeks when he entered Cyrenaica in 331 BC, and Eastern Libya again fell under the control of the Greeks, this time as part of the Ptolemaic Kingdom.

After the fall of Carthage

Carthage was the capital city of Ancient Carthage, on the eastern side of the Lake of Tunis in what is now Tunisia. Carthage was one of the most important trading hubs of the Ancient Mediterranean and one of the most affluent cities of the clas ...

the Romans did not immediately occupy Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

(the region around Tripoli), but left it instead under control of the kings of Numidia

Numidia ( Berber: ''Inumiden''; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tuni ...

, until the coastal cities asked and obtained its protection. Bertarelli, p. 202. Ptolemy Apion, the last Greek ruler, bequeathed Cyrenaica to Rome, which formally annexed the region in 74 BC and joined it to Crete as a Roman province. As part of the Africa Nova province, Tripolitania was prosperous, and reached a golden age in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when the city of Leptis Magna

Leptis or Lepcis Magna, also known by other names in antiquity, was a prominent city of the Carthaginian Empire and Roman Libya at the mouth of the Wadi Lebda in the Mediterranean.

Originally a 7th-centuryBC Phoenician foundation, it was grea ...

, home to the Severan dynasty

The Severan dynasty was a Roman imperial dynasty that ruled the Roman Empire between 193 and 235, during the Roman imperial period. The dynasty was founded by the emperor Septimius Severus (), who rose to power after the Year of the Five Empero ...

, was at its height.

On the Eastern side, Cyrenaica's first Christian communities were established by the time of the Emperor Claudius. Bertarelli, p. 417. It was heavily devastated during the Kitos War and almost depopulated of Greeks and Jews alike. Although repopulated by Trajan

Trajan ( ; la, Caesar Nerva Traianus; 18 September 539/11 August 117) was Roman emperor from 98 to 117. Officially declared ''optimus princeps'' ("best ruler") by the senate, Trajan is remembered as a successful soldier-emperor who presid ...

with military colonies, from then started its decline. Libya was early to convert to Nicene Christianity

The original Nicene Creed (; grc-gre, Σύμβολον τῆς Νικαίας; la, Symbolum Nicaenum) was first adopted at the First Council of Nicaea in 325. In 381, it was amended at the First Council of Constantinople. The amended form is ...

and was the home of Pope Victor I; however, Libya was also home to many non-Nicene varieties of early Christianity, such as Arianism

Arianism ( grc-x-koine, Ἀρειανισμός, ) is a Christological doctrine first attributed to Arius (), a Christian presbyter from Alexandria, Egypt. Arian theology holds that Jesus Christ is the Son of God, who was begotten by G ...

and Donatism

Donatism was a Christian sect leading to a schism in the Church, in the region of the Church of Carthage, from the fourth to the sixth centuries. Donatists argued that Christian clergy must be faultless for their ministry to be effective and ...

.

Islamic Libya

Under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, the

Under the command of 'Amr ibn al-'As, the Rashidun army

The Rashidun army () was the core of the Rashidun Caliphate's armed forces during the early Muslim conquests in the 7th century. The army is reported to have maintained a high level of discipline, strategic prowess and organization, gran ...

conquered Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

. Bertarelli, p. 278. In 647 an army led by Abdullah ibn Saad took Tripoli from the Byzantines definitively. The Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

was conquered by Uqba ibn Nafi

ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ ibn ʿAbd al-Qays al-Fihrī al-Qurashī ( ar, عقبة بن نافع بن عبد القيس الفهري القرشي, ʿUqba ibn Nāfiʿ ibn ʿAbd al-Qays al-Fihrī), also simply known as Uqba ibn Nafi, was an Arab general ser ...

in 663. The Berber tribes of the hinterland accepted Islam, however they resisted Arab political rule.

For the next several decades, Libya was under the purview of the Umayyad

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by the ...

Caliph of Damascus

The Umayyad Caliphate (661–750 CE; , ; ar, ٱلْخِلَافَة ٱلْأُمَوِيَّة, al-Khilāfah al-ʾUmawīyah) was the second of the four major caliphates established after the death of Muhammad. The caliphate was ruled by th ...

until the Abbasids

The Abbasid Caliphate ( or ; ar, الْخِلَافَةُ الْعَبَّاسِيَّة, ') was the third caliphate to succeed the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abdul-Muttalib ...

overthrew the Umayyads in 750, and Libya came under the rule of Baghdad. When Caliph Harun al-Rashid

Abu Ja'far Harun ibn Muhammad al-Mahdi ( ar

, أبو جعفر هارون ابن محمد المهدي) or Harun ibn al-Mahdi (; or 766 – 24 March 809), famously known as Harun al-Rashid ( ar, هَارُون الرَشِيد, translit=Hārūn ...

appointed Ibrahim ibn al-Aghlab as his governor of Ifriqiya in 800, Libya enjoyed considerable local autonomy under the Aghlabid

The Aghlabids ( ar, الأغالبة) were an Arab dynasty of emirs from the Najdi tribe of Banu Tamim, who ruled Ifriqiya and parts of Southern Italy, Sicily, and possibly Sardinia, nominally on behalf of the Abbasid Caliph, for about a ...

dynasty. By the 10th century, the Shiite Fatimids

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a caliphate extant from the tenth to the twelfth centuries AD. Spanning a large area of North Africa, it ranged from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Red Sea in the east. The Fatimids, a dyna ...

controlled Western Libya, and ruled the entire region in 972 and appointed Bologhine ibn Ziri as governor.

Ibn Ziri's Berber Zirid dynasty

The Zirid dynasty ( ar, الزيريون, translit=az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri ( ar, بنو زيري, translit=banū zīrī), or the Zirid state ( ar, الدولة الزيرية, translit=ad-dawla az-zīriyya) was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from ...

ultimately broke away from the Shiite Fatimids, and recognised the Sunni Abbasids of Baghdad as rightful Caliphs. In retaliation, the Fatimids brought about the migration of thousands from mainly two Arab Qaisi tribes, the Banu Sulaym

The Banu Sulaym ( ar, بنو سليم) is an Arab tribe that dominated part of the Hejaz in the pre-Islamic era. They maintained close ties with the Quraysh of Mecca and the inhabitants of Medina, and fought in a number of battles against the ...

and Banu Hilal

The Banu Hilal ( ar, بنو هلال, translit=Banū Hilāl) was a confederation of Arabian tribes from the Hejaz and Najd regions of the Arabian Peninsula that emigrated to North Africa in the 11th century. Masters of the vast plateaux of th ...

to North Africa. This act drastically altered the fabric of the Libyan countryside, and cemented the cultural and linguistic Arabisation of the region.

Zirid rule in Tripolitania was short-lived though, and already in 1001 the Berbers of the Banu Khazrun The Banu Khazrun was a family of the Maghrawa

The Maghrawa or Meghrawa ( ar, المغراويون) were a large Zenata Berber tribal confederation whose cradle and seat of power was the territory located on the Chlef in the north-western part ...

broke away. Tripolitania remained under their control until 1146, when the region was overtaken by the Normans of Sicily. Bertarelli, p. 203. It was not until 1159 that the Almohad

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fou ...

empire reconquered Tripoli from European rule. For the next 50 years, Tripolitania was the scene of numerous battles among Ayyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

, the Almohad rulers and insurgents of the Banu Ghaniya The Banu Ghaniya were an Almoravid Sanhaja Berber dynasty. Their first leader, Muhammad ibn Ali ibn Yusuf, a son of Ali ibn Yusuf al-Massufi and the Almoravid Princess Ghaniya, was appointed as governor of the Balearic Islands in 1126. Following th ...

. Later, a general of the Almohads

The Almohad Caliphate (; ar, خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or or from ar, ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, translit=al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit=those who profess the unity of God) was a North African Berber Muslim empire fo ...

, Muhammad ibn Abu Hafs, ruled Libya from 1207 to 1221 before the later establishment of a Tunisian Hafsid dynasty

The Hafsids ( ar, الحفصيون ) were a Sunni Muslim dynasty of Berber descentC. Magbaily Fyle, ''Introduction to the History of African Civilization: Precolonial Africa'', (University Press of America, 1999), 84. who ruled Ifriqiya (weste ...

independent from the Almohads. The Hafsids ruled Tripolitania for nearly 300 years. By the 16th century the Hafsids became increasingly caught up in the power struggle between Spain and the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

.

After weakening control of Abbasids, Cyrenaica was under Egypt based states such as Tulunids, Ikhshidids, Ayyubids

The Ayyubid dynasty ( ar, الأيوبيون '; ) was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin ...

and Mamluks

Mamluk ( ar, مملوك, mamlūk (singular), , ''mamālīk'' (plural), translated as "one who is owned", meaning "slave", also transliterated as ''Mameluke'', ''mamluq'', ''mamluke'', ''mameluk'', ''mameluke'', ''mamaluke'', or ''marmeluke'') i ...

before Ottoman conquest in 1517. Finally Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

acquired independence under Awlad Muhammad dynasty after Kanem rule. Ottomans finally conquered Fezzan between 1556 and 1577.

Ottoman Tripolitania

After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510, and its handover to the

After a successful invasion of Tripoli by Habsburg Spain in 1510, and its handover to the Knights of St. John

The Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem ( la, Ordo Fratrum Hospitalis Sancti Ioannis Hierosolymitani), commonly known as the Knights Hospitaller (), was a medieval and early modern Catholic military order. It was headq ...

, the Ottoman admiral Sinan Pasha took control of Libya in 1551. His successor Turgut Reis

Dragut ( tr, Turgut Reis) (1485 – 23 June 1565), known as "The Drawn Sword of Islam", was a Muslim Ottoman naval commander, governor, and noble, of Turkish or Greek descent. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extende ...

was named the Bey of Tripoli and later Pasha of Tripoli in 1556. By 1565, administrative authority as regent in Tripoli was vested in a ''pasha

Pasha, Pacha or Paşa ( ota, پاشا; tr, paşa; sq, Pashë; ar, باشا), in older works sometimes anglicized as bashaw, was a higher rank in the Ottoman political and military system, typically granted to governors, generals, dignita ...

'' appointed directly by the '' sultan'' in Constantinople

la, Constantinopolis ota, قسطنطينيه

, alternate_name = Byzantion (earlier Greek name), Nova Roma ("New Rome"), Miklagard/Miklagarth ( Old Norse), Tsargrad ( Slavic), Qustantiniya (Arabic), Basileuousa ("Queen of Cities"), Megalopolis ( ...

/Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

. In the 1580s, the rulers of Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

gave their allegiance to the sultan, and although Ottoman authority was absent in Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, a ''bey'' was stationed in Benghazi late in the next century to act as agent of the government in Tripoli. European slaves and large numbers of enslaved Blacks transported from Sudan were also a feature of everyday life in Tripoli. In 1551, Turgut Reis

Dragut ( tr, Turgut Reis) (1485 – 23 June 1565), known as "The Drawn Sword of Islam", was a Muslim Ottoman naval commander, governor, and noble, of Turkish or Greek descent. Under his command, the Ottoman Empire's maritime power was extende ...

enslaved almost the entire population of the Maltese island of Gozo

Gozo (, ), Maltese: ''Għawdex'' () and in antiquity known as Gaulos ( xpu, 𐤂𐤅𐤋, ; grc, Γαῦλος, Gaúlos), is an island in the Maltese archipelago in the Mediterranean Sea. The island is part of the Republic of Malta. After t ...

, some 5,000 people, sending them to Libya.

In time, real power came to rest with the pasha's corps of janissaries

A Janissary ( ota, یڭیچری, yeŋiçeri, , ) was a member of the elite infantry units that formed the Ottoman Sultan's household troops and the first modern standing army in Europe. The corps was most likely established under sultan Orhan ...

. In 1611 the '' deys'' staged a coup against the pasha, and Dey Sulayman Safar was appointed as head of government. For the next hundred years, a series of ''deys'' effectively ruled Tripolitania. The two most important Deys were Mehmed Saqizli Mehmed Saqizli ( tr, Sakızlı Mehmed Paşa, literally, Mehmed Pasha of Chios) (died 1649), (r.1631-49) was Dey and Pasha of Tripolis.Bertarelli (1929), p. 204.

He was born into a Christian family of Greek origin on the island of Chios (known in Ott ...

(r. 1631–49) and Osman Saqizli (r. 1649–72), both also Pasha, who ruled effectively the region. Bertarelli, p. 204. The latter conquered also Cyrenaica.

Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer

Lacking direction from the Ottoman government, Tripoli lapsed into a period of military anarchy during which coup followed coup and few deys survived in office more than a year. One such coup was led by Turkish officer Ahmed Karamanli

Ahmed or Ahmed Karamanli or Qaramanli or al-Qaramanli, (most commonly Ahmed Karamanli) (1686–1745) was of Janissary origin and a Member from the Karamanids.The City in the Islamic world, Volume 1, Salma Khadra Jayyusi, Renata Holod, Attilio Pe ...

. The Karamanlis ruled from 1711 until 1835 mainly in Tripolitania, and had influence in Cyrenaica and Fezzan as well by the mid-18th century. Ahmed's successors proved to be less capable than himself, however, the region's delicate balance of power allowed the Karamanli. The 1793–95 Tripolitanian civil war occurred in those years. In 1793, Turkish officer Ali Pasha Ali Pasha was the name of numerous Ottoman pashas named Ali. It is most commonly used to refer to Ali Pasha of Ioannina.

People

* Çandarlı Ali Pasha (died 1406), Ottoman grand vizier (1387–1406)

* Hadım Ali Pasha (died 1511), Ottoman grand v ...

deposed Hamet Karamanli and briefly restored Tripolitania to Ottoman rule. Hamet's brother Yusuf

Yusuf ( ar, يوسف ') is a male name of Arabic origin meaning "God increases" (in piety, power and influence).From the Hebrew יהוה להוסיף ''YHWH Lhosif'' meaning "YHWH will increase/add". It is the Arabic equivalent of the Hebrew name ...

(r. 1795–1832) re-established Tripolitania's independence.

In the early 19th century war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the

In the early 19th century war broke out between the United States and Tripolitania, and a series of battles ensued in what came to be known as the First Barbary War

The First Barbary War (1801–1805), also known as the Tripolitan War and the Barbary Coast War, was a conflict during the Barbary Wars, in which the United States and Sweden fought against Tripolitania. Tripolitania had declared war against S ...

and the Second Barbary War

The Second Barbary War (1815) or the U.S.–Algerian War was fought between the United States and the North African Barbary Coast states of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers. The war ended when the United States Senate ratified Commodore Stephen De ...

. By 1819, the various treaties of the Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

had forced the Barbary states to give up piracy almost entirely, and Tripolitania's economy began to crumble. As Yusuf weakened, factions sprung up around his three sons. Civil war soon resulted. Bertarelli, p. 205.

Ottoman Sultan Mahmud II

Mahmud II ( ota, محمود ثانى, Maḥmûd-u s̠ânî, tr, II. Mahmud; 20 July 1785 – 1 July 1839) was the 30th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire from 1808 until his death in 1839.

His reign is recognized for the extensive administrative, ...

sent in troops ostensibly to restore order, marking the end of both the Karamanli dynasty and an independent Tripolitania. Order was not recovered easily, and the revolt of the Libyan under Abd-El-Gelil and Gûma ben Khalifa lasted until the death of the latter in 1858. The second period of direct Ottoman rule saw administrative changes, and greater order in the governance of the three provinces of Libya. Ottoman rule finally reasserted to Fezzan between 1850 and 1875 for earning income from Saharan commerce.

Italian colonization and Allied occupation

After the

After the Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result ...

(1911–1912), Italy simultaneously turned the three regions into colonies. From 1912 to 1927, the territory of Libya was known as Italian North Africa

Libya ( it, Libia; ar, ليبيا, Lībyā al-Īṭālīya) was a colony of the Fascist Italy located in North Africa, in what is now modern Libya, between 1934 and 1943. It was formed from the unification of the colonies of Italian Cyrenaica a ...

. From 1927 to 1934, the territory was split into two colonies, Italian Cyrenaica

Italian Cyrenaica (; ) was an Italian colony, located in present-day eastern Libya, that existed from 1911 to 1934. It was part of the territory conquered from the Ottoman Empire during the Italo-Turkish War of 1911, alongside Italian Tripol ...

and Italian Tripolitania, run by Italian governors. Some 150,000 Italians settled in Libya, constituting roughly 20% of the total population.

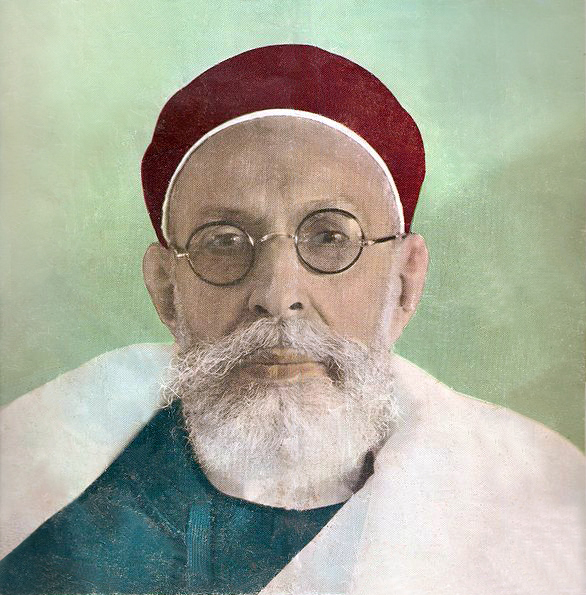

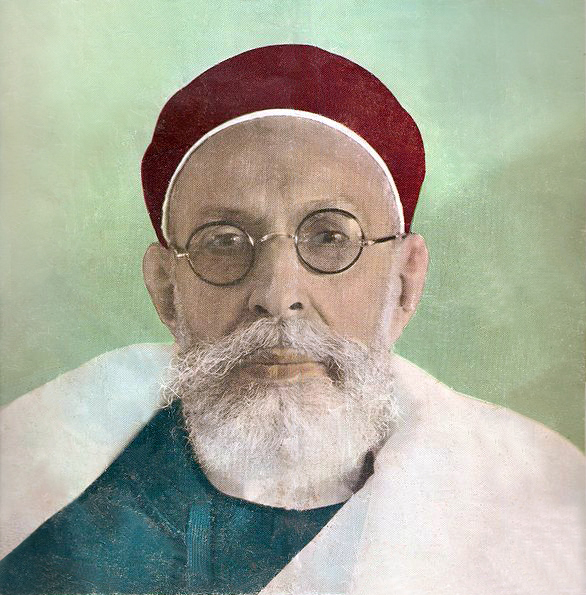

Omar Mukhtar rose to prominence as a resistance leader against Italian colonization and became a national hero despite his capture and execution on 16 September 1931. His face is currently printed on the Libyan ten dinar note in memory and recognition of his patriotism. Another prominent resistance leader, Idris al-Mahdi as-Senussi (later King Idris I), Emir of Cyrenaica, continued to lead the Libyan resistance until the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

The so-called " pacification of Libya" by the Italians resulted in mass deaths of the indigenous people in Cyrenaica, killing approximately one quarter of Cyrenaica's population of 225,000. Ilan Pappé

Ilan Pappé ( he, אילן פפה, ; born 1954) is an expatriate Israeli historian and socialist activist. He is a professor with the College of Social Sciences and International Studies at the University of Exeter in the United Kingdom, direc ...

estimates that between 1928 and 1932 the Italian military "killed half the Bedouin population (directly or through disease and starvation in Italian concentration camps in Libya

Background: The beginning of colonization in Libya

The conquest of Libya took place in two phases; the first was considered a more superficial and approximate stage, it began on the 4th of October 1911 under Giovanni Giolitti’s command. The e ...

)."

In 1934, Italy combined

In 1934, Italy combined Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

and Fezzan

Fezzan ( , ; ber, ⴼⵣⵣⴰⵏ, Fezzan; ar, فزان, Fizzān; la, Phazania) is the southwestern region of modern Libya. It is largely desert, but broken by mountains, uplands, and dry river valleys (wadis) in the north, where oases enable ...

and adopted the name "Libya" (used by the Ancient Greeks for all of North Africa except Egypt) for the unified colony, with Tripoli as its capital. The Italians emphasized infrastructure improvements and public works. In particular, they greatly expanded Libyan railway and road networks from 1934 to 1940, building hundreds of kilometers of new roads and railways and encouraging the establishment of new industries and dozens of new agricultural villages.

In June 1940, Italy entered World War II. Libya became the setting for the hard-fought North African Campaign that ultimately ended in defeat for Italy and its German ally in 1943.

From 1943 to 1951, Libya was under Allied occupation. The British military administered the two former Italian Libyan provinces of Tripolitana and Cyrenaïca, while the French administered the province of Fezzan. In 1944, Idris returned from exile in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo met ...

but declined to resume permanent residence in Cyrenaica until the removal of some aspects of foreign control in 1947. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.

Independence, Kingdom and Libya under Gaddafi

On 24 December 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King

On 24 December 1951, Libya declared its independence as the United Kingdom of Libya, a constitutional and hereditary monarchy under King Idris Idris may refer to:

People

* Idris (name), a list of people and fictional characters with the given name or surname

* Idris (prophet), Islamic prophet in the Qur'an, traditionally identified with Enoch, an ancestor of Noah in the Bible

* Idris G ...

, Libya's only monarch. The discovery of significant oil reserves

An oil is any nonpolar chemical substance that is composed primarily of hydrocarbons and is hydrophobic (does not mix with water) & lipophilic (mixes with other oils). Oils are usually flammable and surface active. Most oils are unsaturate ...

in 1959 and the subsequent income from petroleum sales enabled one of the world's poorest nations to establish an extremely wealthy state. Although oil drastically improved the Libyan government's finances, resentment among some factions began to build over the increased concentration of the nation's wealth in the hands of King Idris.

On 1 September 1969, a group of rebel military officers led by

On 1 September 1969, a group of rebel military officers led by Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by '' The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spelli ...

launched a coup d'état against King Idris, which became known as the Al Fateh Revolution. Gaddafi was referred to as the " Brother Leader and Guide of the Revolution" in government statements and the official Libyan press. Moving to reduce Italian influence, in October 1970 all Italian-owned assets were expropriated and the 12,000-strong Italian community was expelled from Libya alongside the smaller community of Libyan Jews. The day became a national holiday National holiday may refer to:

* National day, a day when a nation celebrates a very important event in its history, such as its establishment

*Public holiday, a holiday established by law, usually a day off for at least a portion of the workforce, ...

known as "Vengeance Day". Libya's increase in prosperity was accompanied by increased internal political repression, and political dissent was made illegal under Law 75 of 1973. Widespread surveillance of the population was carried out through Gaddafi's Revolutionary Committees.

Gaddafi also wanted to combat the strict social restrictions that had been imposed on women by the previous regime, establishing the Revolutionary Women's Formation to encourage reform. In 1970, a law was introduced affirming equality of the sexes and insisting on wage parity. In 1971, Gaddafi sponsored the creation of a Libyan General Women's Federation. In 1972, a law was passed criminalizing the marriage of any females under the age of sixteen and ensuring that a woman's consent was a necessary prerequisite for a marriage.

On 25 October 1975, a coup attempt was launched by some 20 military officers, mostly from the city of Misrata

Misrata ( ; also spelled Misurata or Misratah; ar, مصراتة, Miṣrāta ) is a city in the Misrata District in northwestern Libya, situated to the east of Tripoli and west of Benghazi on the Mediterranean coast near Cape Misrata. With a ...

. This resulted in the arrest and executions of the coup plotters. On 2 March 1977, Libya officially became the "Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya". Gaddafi officially passed power to the General People's Committees and henceforth claimed to be no more than a symbolic figurehead. The new ''jamahiriya'' (Arab for "republic") governance structure he established was officially referred to as " direct democracy".

Gaddafi, in his vision of democratic government and political philosophy

Political philosophy or political theory is the philosophical study of government, addressing questions about the nature, scope, and legitimacy of public agents and institutions and the relationships between them. Its topics include politics, l ...

, published '' The Green Book'' in 1975. His short book inscribed a representative mix of utopian socialism and Arab nationalism with a streak of Bedouin supremacy.

In February 1977, Libya started delivering military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan conflict began in earnest when Libya's support of rebel forces in northern Chad escalated into an

In February 1977, Libya started delivering military supplies to Goukouni Oueddei and the People's Armed Forces in Chad. The Chadian–Libyan conflict began in earnest when Libya's support of rebel forces in northern Chad escalated into an invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing co ...

. Later that same year, Libya and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

fought a four-day border war that came to be known as the Libyan-Egyptian War. Both nations agreed to a ceasefire

A ceasefire (also known as a truce or armistice), also spelled cease fire (the antonym of 'open fire'), is a temporary stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions. Ceasefires may be between state ac ...

under the mediation of the Algerian president Houari Boumediène. Hundreds of Libyans lost their lives in the country's support for Idi Amin's Uganda in its war against Tanzania. Gaddafi financed various other groups from anti-nuclear movements to Australian trade unions.

Libya adopted its plain green national flag on 19 November 1977. Before 2011, it became the only plain-coloured flag in the world.

From 1977 onward, per capita income in the country rose to more than US$11,000, the fifth-highest in Africa, while the Human Development Index

The Human Development Index (HDI) is a statistic composite index of life expectancy, Education Index, education (mean years of schooling completed and expected years of schooling upon entering the Educational system, education system), ...

became the highest in Africa and greater than that of Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in Western Asia. It covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula, and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries by area, fifth-largest country in Asia ...

. This was achieved without borrowing any foreign loans, keeping Libya debt-free. The Great Manmade River was also built to allow free access to fresh water across large parts of the country. In addition, financial support was provided for university scholarships and employment programs.

Much of Libya's income from oil, which soared in the 1970s, was spent on arms purchases and on sponsoring dozens of paramilitaries and terrorist groups around the world. An American airstrike intended to kill Gaddafi failed in 1986. Libya was finally put under sanctions by the United Nations after the bombing

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechan ...

of a commercial flight at Lockerbie in 1988 killed 270 people. In 2003, Gaddafi renounced that all of his regime's weapons of mass destruction

A weapon of mass destruction (WMD) is a chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear, or any other weapon that can kill and bring significant harm to numerous individuals or cause great damage to artificial structures (e.g., buildings), natur ...

were disassembled and Libya transitioned its shift to nuclear power

Nuclear power is the use of nuclear reactions to produce electricity. Nuclear power can be obtained from nuclear fission, nuclear decay and nuclear fusion reactions. Presently, the vast majority of electricity from nuclear power is produced ...

.

First Libyan Civil War

The first civil war came during theArab Spring

The Arab Spring ( ar, الربيع العربي) was a series of anti-government protests, uprisings and armed rebellions that spread across much of the Arab world in the early 2010s. It began in Tunisia in response to corruption and econom ...

movements which overturned the rulers of Tunisia

)

, image_map = Tunisia location (orthographic projection).svg

, map_caption = Location of Tunisia in northern Africa

, image_map2 =

, capital = Tunis

, largest_city = capital

, ...

and Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Med ...

. Libya first experienced protests against Gaddafi's regime on 15 February 2011, with a full-scale revolt beginning on 17 February

Events Pre-1600

*1370 – Northern Crusades: Grand Duchy of Lithuania and the Teutonic Knights meet in the Battle of Rudau.

*1411 – Following the successful campaigns during the Ottoman Interregnum, Musa Çelebi, one of the sons of B ...

. Libya's authoritarian regime led by Muammar Gaddafi put up much more of a resistance compared to the regimes in Egypt and Tunisia. While overthrowing the regimes in Egypt and Tunisia was a relatively quick process, Gaddafi's campaign posed significant stalls on the uprising in Libya. The first announcement of a competing political authority appeared online and declared the Interim Transitional National Council

The National Transitional Council of Libya ( ar, المجلس الوطني الإنتقالي '), sometimes known as the Transitional National Council, was the ''de facto'' government of Libya for a period during and after the Libyan Civil War ...

as an alternative government. One of Gaddafi's senior advisors responded by posting a tweet, wherein he resigned, defected, and advised Gaddafi to flee. By 20 February, the unrest had spread to Tripoli. On 27 February 2011, the National Transitional Council

The National Transitional Council of Libya ( ar, المجلس الوطني الإنتقالي '), sometimes known as the Transitional National Council, was the ''de facto'' government of Libya for a period during and after the Libyan Civil War ...

was established to administer the areas of Libya under rebel control. On 10 March 2011, the United States and many other nations recognised the council headed by Mahmoud Jibril as acting prime minister and as the legitimate representative of the Libyan people and withdrawing the recognition of Gaddafi's regime.

Pro-Gaddafi forces were able to respond militarily to rebel pushes in Western Libya

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

and launched a counterattack along the coast toward Benghazi, the ''de facto'' centre of the uprising. The town of Zawiya, from Tripoli, was bombarded by air force planes and army tanks and seized by Jamahiriya troops, "exercising a level of brutality not yet seen in the conflict."

United Nations Secretary General

The secretary-general of the United Nations (UNSG or SG) is the chief administrative officer of the United Nations and head of the United Nations Secretariat, one of the six principal organs of the United Nations.

The role of the secretary-g ...

Ban Ki-moon

Ban Ki-moon (; ; born 13 June 1944) is a South Korean politician and diplomat who served as the eighth secretary-general of the United Nations between 2007 and 2016. Prior to his appointment as secretary-general, Ban was his country's Minister ...

and the United Nations Human Rights Council

The United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), CDH is a United Nations body whose mission is to promote and protect human rights around the world. The Council has 47 members elected for staggered three-year terms on a regional group basis. ...

, condemned the crackdown as violating international law, with the latter body expelling Libya outright in an unprecedented action.

On 17 March 2011 the UN Security Council passed Resolution 1973

Resolution 1973 was adopted by the United Nations Security Council on 17 March 2011 in response to the First Libyan Civil War. The resolution formed the legal basis for military intervention in the Libyan Civil War, demanding "an immediate cease ...

, with a 10–0 vote and five abstentions including Russia, China, India, Brazil and Germany. The resolution sanctioned the establishment of a no-fly zone

A no-fly zone, also known as a no-flight zone (NFZ), or air exclusion zone (AEZ), is a territory or area established by a military power over which certain aircraft are not permitted to fly. Such zones are usually set up in an enemy power's te ...

and the use of "all means necessary" to protect civilians within Libya. On 19 March, the first act of NATO allies to secure the no-fly zone began by destroying Libyan air defenses when French military jets entered Libyan airspace on a reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops ( skirmishe ...

mission heralding attacks on enemy targets.

In the weeks that followed, US American forces were in the forefront of NATO operations against Libya. More than 8,000 US personnel in warships and aircraft were deployed in the area. At least 3,000 targets were struck in 14,202 strike sorties, 716 of them in Tripoli and 492 in Brega

Brega , also known as ''Mersa Brega'' or ''Marsa al-Brega'' ( ar, مرسى البريقة , i.e. "Brega Seaport"), is a complex of several smaller towns, industry installations and education establishments situated in Libya on the Gulf of Sidra, ...

. The US air offensive included flights of B-2 Stealth bombers, each bomber armed with sixteen 2000-pound bombs, flying out of and returning to their base in Missouri in the continental United States. The support provided by the NATO air forces contributed to the ultimate success of the revolution.

By 22 August 2011, rebel fighters had entered Tripoli and occupied Green Square, which they renamed Martyrs' Square in honour of those killed since 17 February 2011. On 20 October 2011, the last heavy fighting of the uprising came to an end in the city of Sirte

Sirte (; ar, سِرْت, ), also spelled Sirt, Surt, Sert or Syrte, is a city in Libya. It is located south of the Gulf of Sirte, between Tripoli and Benghazi. It is famously known for its battles, ethnic groups, and loyalty to Muammar Gad ...

. The Battle of Sirte was both the last decisive battle and the last one in general of the First Libyan Civil War

The First Libyan Civil War was an armed conflict in 2011 in the North African country of Libya that was fought between forces loyal to Colonel Muammar Gaddafi and rebel groups that were seeking to oust his government. It erupted with the Libya ...

where Gaddafi was captured and killed by NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO, ; french: Organisation du traité de l'Atlantique nord, ), also called the North Atlantic Alliance, is an intergovernmental military alliance between 30 member states – 28 European and two No ...

-backed forces on 20 October 2011. Sirte was the last Gaddafi loyalist stronghold and his place of birth. The defeat of loyalist

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

forces was celebrated on 23 October 2011, three days after the fall of Sirte.

At least 30,000 Libyans died in the civil war. In addition, the National Transitional Council

The National Transitional Council of Libya ( ar, المجلس الوطني الإنتقالي '), sometimes known as the Transitional National Council, was the ''de facto'' government of Libya for a period during and after the Libyan Civil War ...

estimated 50,000 wounded.

Interwar period and the Second Libyan Civil War

National Transitional Council

The National Transitional Council of Libya ( ar, المجلس الوطني الإنتقالي '), sometimes known as the Transitional National Council, was the ''de facto'' government of Libya for a period during and after the Libyan Civil War ...

officially handed power over to the wholly-elected General National Congress, which was then tasked with the formation of an interim government and the drafting of a new Libyan Constitution to be approved in a general referendum

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of ...

.

On 25 August 2012, in what Reuters reported as "the most blatant sectarian attack" since the end of the civil war, unnamed organized assailants bulldozed a Sufi mosque with graves, in broad daylight in the center of the Libyan capital Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

*Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in t ...

. It was the second such razing of a Sufi site in two days. Numerous acts of vandalism and destruction of heritage were carried out by suspected Islamist militias, including the removal of the Nude Gazelle Statue and the destruction and desecration of World War II-era British grave sites near Benghazi. Many other cases of heritage vandalism were reported to be carried out by Islamist-related radical militias and mobs that either destroyed, robbed, or looted a number of historic sites.

On 11 September 2012, Islamist militants mounted an attack on the American diplomatic compound in Benghazi, killing the U.S. ambassador to Libya, J. Christopher Stevens

John Christopher Stevens (April 18, 1960 – September 11, 2012) was an American career diplomat and lawyer who served as the U.S. Ambassador to Libya from May 22, 2012, to September 11, 2012. Stevens was killed when the U.S. Special Missio ...

, and three others. The incident generated outrage in the United States and Libya. On 7 October 2012, Libya's Prime Minister-elect Mustafa A.G. Abushagur

Mustafa A. G. Abushagur (; born 15 February 1951) is a Libyan politician, professor of electrical engineering, university president and entrepreneur. He served as interim Deputy Prime Minister of Libya from 22 November 2011 to 14 November 2012 in ...

was ousted after failing a second time to win parliamentary approval for a new cabinet. On 14 October 2012, the General National Congress elected former GNC member and human rights lawyer Ali Zeidan as prime minister-designate. Zeidan was sworn in after his cabinet was approved by the GNC. On 11 March 2014, after having been ousted by the GNC for his inability to halt a rogue oil shipment, Prime Minister Zeidan stepped down, and was replaced by Prime Minister Abdullah al-Thani.

The Second Civil War began in May 2014 following fighting between rival parliaments with tribal militias and jihad