Khudadad on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Kingdom of Mysore was a geopolitical realm in

Tipu's successful attacks in 1790 on the

Tipu's successful attacks in 1790 on the

The years that followed witnessed cordial relations between Mysore and the British until things began to sour in the 1820s. Even though the

The years that followed witnessed cordial relations between Mysore and the British until things began to sour in the 1820s. Even though the  In 1876–77, however, towards the end of the period of direct British rule, Mysore was struck by a devastating famine with estimated mortality figures ranging between 700,000 and 1,100,000, or nearly a fifth of the population. Shortly thereafter, Maharaja Chamaraja X, educated in the British system, took over the rule of Mysore in 1881, following the success of a lobby set up by the Wodeyar dynasty that was in favour of rendition. Accordingly, a resident British officer was appointed at the Mysore court and a Dewan to handle the Maharaja's administration.Kamath (2001), pp. 250–254 From then onwards, until Indian independence in 1947, Mysore remained a Princely State within the

In 1876–77, however, towards the end of the period of direct British rule, Mysore was struck by a devastating famine with estimated mortality figures ranging between 700,000 and 1,100,000, or nearly a fifth of the population. Shortly thereafter, Maharaja Chamaraja X, educated in the British system, took over the rule of Mysore in 1881, following the success of a lobby set up by the Wodeyar dynasty that was in favour of rendition. Accordingly, a resident British officer was appointed at the Mysore court and a Dewan to handle the Maharaja's administration.Kamath (2001), pp. 250–254 From then onwards, until Indian independence in 1947, Mysore remained a Princely State within the

Before the 18th century, the society of the kingdom followed age-old and deeply established norms of social interaction between people. Accounts by contemporaneous travellers indicate the widespread practice of the

Before the 18th century, the society of the kingdom followed age-old and deeply established norms of social interaction between people. Accounts by contemporaneous travellers indicate the widespread practice of the

The era of the kingdom of Mysore is considered a golden age in the development of

The era of the kingdom of Mysore is considered a golden age in the development of

File:Mysore Palace, India (photo - Jim Ankan Deka).jpg, Mysore Palace

File:Chamundeshwari Temple Mysore 2.jpg, The

The first iron-cased and metal-

The first iron-cased and metal-

online review

{{DEFAULTSORT:Mysore, Kingdom of Former monarchies of India Former countries in South Asia Former monarchies of South Asia Historical Indian regions History of Karnataka Princely states of India States and territories established in 1399 States and territories disestablished in 1948 1399 establishments in Asia 1950 disestablishments in India 14th-century establishments in India Former kingdoms Gun salute princely states

southern India

South India, also known as Southern India or Peninsular India, is the southern part of the Deccan Peninsula in India encompassing the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana as well as the union territories of ...

founded in around 1399 in the vicinity of the modern-day city of Mysore

Mysore ( ), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern Indian state of Karnataka. It is the headquarters of Mysore district and Mysore division. As the traditional seat of the Wadiyar dynasty, the city functioned as the capital of the ...

and prevailed until 1950. The territorial boundaries and the form of government transmuted substantially throughout the kingdom's lifetime. While originally a feudal vassal under the Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire, also known as the Karnata Kingdom, was a late medieval Hinduism, Hindu empire that ruled much of southern India. It was established in 1336 by the brothers Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of the Sangama dynasty, belongi ...

, it became a princely state in British Raj

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

from 1799 to 1947, marked in-between by major political changes.

The kingdom, which was founded and ruled for the most part by the Wadiyars, initially served as a feudal vassal under the Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire, also known as the Karnata Kingdom, was a late medieval Hinduism, Hindu empire that ruled much of southern India. It was established in 1336 by the brothers Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of the Sangama dynasty, belongi ...

. With the gradual decline of the Empire, the 16th-century Timmaraja Wodeyar II

Timmaraja Wodeyar II (reigned 7 February 1533 – 1572), was the sixth maharaja of the Kingdom of Mysore, who ruled between 7 February 1553 and 1572. He was eldest son of Chamaraja Wodeyar III, the fifth raja of Mysore. On 17 February 1553, he ...

declared independence from it. The 17th century saw a steady expansion of its territory and, during the rules of Narasaraja Wodeyar I and Devaraja Wodeyar II, the kingdom annexed large expanses of what is now southern Karnataka and parts of Tamil Nadu

Tamil Nadu (; , TN) is the southernmost States and union territories of India, state of India. The List of states and union territories of India by area, tenth largest Indian state by area and the List of states and union territories of Indi ...

, becoming a formidable power in the Deccan

The Deccan is a plateau extending over an area of and occupies the majority of the Indian peninsula. It stretches from the Satpura and Vindhya Ranges in the north to the northern fringes of Tamil Nadu in the south. It is bound by the mount ...

.

During a brief Muslim rule

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is p ...

from 1761 to 1799, the kingdom became a sultan

Sultan (; ', ) is a position with several historical meanings. Originally, it was an Arabic abstract noun meaning "strength", "authority", "rulership", derived from the verbal noun ', meaning "authority" or "power". Later, it came to be use ...

ate under Hyder Ali

Hyder Ali (''Haidar'alī''; ; 1720 – 7 December 1782) was the Sultan and ''de facto'' ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. Born as Hyder Ali, he distinguished himself as a soldier, eventually drawing the attention of Mysore's ...

and Tipu, often referring to it as ''Sultanat-e-Khudadad'' (). During this time, it came into conflict with the Maratha Confederacy

The Maratha Empire, also referred to as the Maratha Confederacy, was an early modern polity in the Indian subcontinent. It comprised the realms of the Peshwa and four major independent Maratha states under the nominal leadership of the former.

...

, the Nizam of Hyderabad

Nizam of Hyderabad was the title of the ruler of Hyderabad State ( part of the Indian state of Telangana, and the Kalyana-Karnataka region of Karnataka). ''Nizam'' is a shortened form of (; ), and was the title bestowed upon Asaf Jah I wh ...

, the kingdom of Travancore

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vocalize it as st ...

, and the British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories and Crown Dependencies.

* British national identity, the characteristics of British people and culture ...

, culminating in four Anglo-Mysore Wars. Mysore's success in the First Anglo-Mysore war

The First Anglo-Mysore War (1767–1769) was a conflict in Mughal India, India between the Sultanate of Mysore and the East India Company. The war was instigated in part by the machinations of Nizam Ali Khan, Asaf Jah II, Asaf Jah II, the Niz ...

and a stalemate in the Second

The second (symbol: s) is a unit of time derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes, and finally to 60 seconds each (24 × 60 × 60 = 86400). The current and formal definition in the International System of U ...

were followed by defeats in the Third

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', i.e., the third in a series of fractional parts in a sexagesimal number system

Places

* 3rd Street (di ...

and the Fourth. Following Tipu's death in the Fourth War during the Siege of Seringapatam, large parts of his kingdom were annexed by the British, which signalled the end of a period of Mysorean hegemony over South India. Power returned absolutely to the Wadiyars when Krishnaraja Wodeyar III

Krishnaraja Wodeyar III (14 July 1794 – 27 March 1868) was an Indian king who was the twenty-second Maharaja of Mysore. He ruled the kingdom for nearly seventy years, from 30 June 1799 to 27 March 1868, for a good portion of the latter period ...

became king.

In 1831, the British took direct control of the kingdom and a commission

In-Commission or commissioning may refer to:

Business and contracting

* Commission (remuneration), a form of payment to an agent for services rendered

** Commission (art), the purchase or the creation of a piece of art most often on behalf of anot ...

administered it until 1881.Rajakaryaprasakta Rao Bahadur (1936), pg. 383 Through an instrument of rendition, power was once again transferred to the Wadiyars in 1881, when Chamaraja Wadiyar X was made king. In 1913, in lieu of the instrument, a proper subsidiary alliance

A subsidiary alliance, in South Asian history, was a tributary alliance between an Indian state and a European East India Company.

Under this system, an Indian ruler who formed an agreement with the company in question would be provided wit ...

was struck with the kingdom during Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV.

Upon India's independence

The Indian independence movement was a series of historic events in South Asia with the ultimate aim of ending British colonial rule. It lasted until 1947, when the Indian Independence Act 1947 was passed.

The first nationalistic movement t ...

from the Crown rule in 1947, the kingdom of Mysore acceded to the Union of India. Upon accession, it became Mysore State, later uniting with other Kannada

Kannada () is a Dravidian language spoken predominantly in the state of Karnataka in southwestern India, and spoken by a minority of the population in all neighbouring states. It has 44 million native speakers, and is additionally a ...

speaking regions to form the present-day Karnataka

Karnataka ( ) is a States and union territories of India, state in the southwestern region of India. It was Unification of Karnataka, formed as Mysore State on 1 November 1956, with the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956, States Re ...

state. Soon after Independence, Maharaja Jayachamaraja Wadiyar was made Rajapramukh until 1956, when he became the first governor

A governor is an politician, administrative leader and head of a polity or Region#Political regions, political region, in some cases, such as governor-general, governors-general, as the head of a state's official representative. Depending on the ...

of the enlarged state.

Even as a princely state, Mysore came to be counted among the more developed and urbanised regions of South Asia. The period since the penultimate restoration (1799–1947) also saw Mysore emerge as one of the important centres of art and culture

Art is a diverse range of culture, cultural activity centered around works of art, ''works'' utilizing Creativity, creative or imagination, imaginative talents, which are expected to evoke a worthwhile experience, generally through an express ...

in India. The maharajas of Mysore were not only accomplished exponents of the fine arts and men of letters, they were enthusiastic patrons as well. Their legacies continue to influence music and the arts even today, as well as rocket science with the use of Mysorean rockets

Mysorean rockets were an Indian military weapon. The iron-cased rockets were successfully deployed for military use. They were the first successful iron-cased rockets, developed in the late 18th century in the Kingdom of Mysore (part of prese ...

.

History

Early history

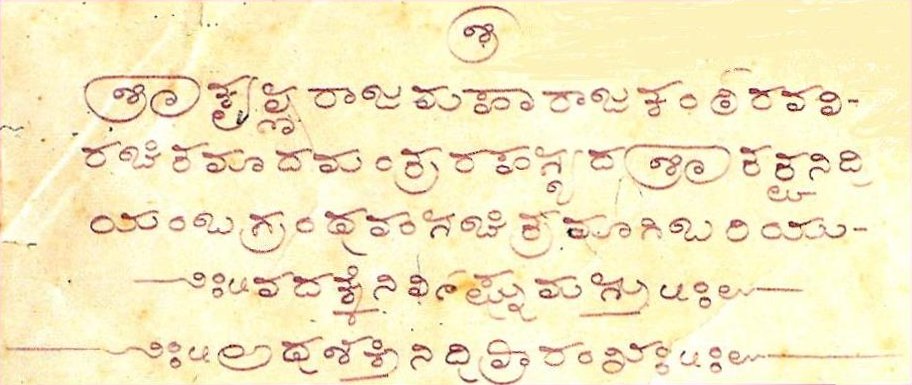

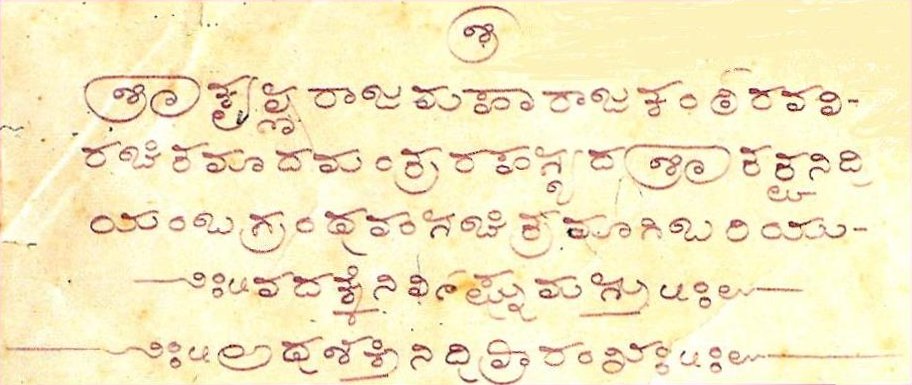

Sources for the history of the kingdom include numerous extant lithic and copper plate inscriptions, records from the Mysore palace and contemporary literary sources in Kannada,Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

and other languages.Kamath (2001), pp. 11–12, pp. 226–227; Pranesh (2003), p. 11Narasimhacharya (1988), p. 23Subrahmanyam (2003), p. 64; Rice E.P. (1921), p. 89 According to traditional accounts, the kingdom originated as a small state based in the modern city of Mysore and was founded by two brothers, Yaduraya (also known as Vijaya) and Krishnaraya. Their origins are mired in legend and are still a matter of debate; while some historians posit a northern origin at Dwarka

Dwarka () is a town and municipality of Devbhumi Dwarka district in the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Gujarat. It is located on the western shore of the Okhamandal Peninsula on the right bank of the Gomti river at ...

,Kamath (2001), p. 226Rice B.L. (1897), p. 361 others locate it in Karnataka.Pranesh (2003), pp. 2–3Wilks, Aiyangar in Aiyangar and Smith (1911), pp. 275–276 Yaduraya is said to have married Chikkadevarasi, the local princess and assumed the feudal title "Wodeyar" (), which the ensuing dynasty retained.Aiyangar (1911), p. 275; Pranesh (2003), p. 2 The first unambiguous mention of the Wodeyar family is in 16th century Kannada literature

Kannada literature is the Text corpus, corpus of written forms of the Kannada language, which is spoken mainly in the Indian state of Karnataka and written in the Kannada script.

Attestations in literature span one and a half millennia,

R.S. ...

from the reign of the Vijayanagara king Achyuta Deva Raya

Achyuta Deva Raya (r. 1529 - 1542 CE) was a emperor of Vijayanagara who succeeded his older brother, Krishnadevaraya, after the latter's death in 1529 CE.

During his reign, Fernao Nuniz, a Portuguese-Jewish traveller, chronicler and horse ...

(1529–1542); the earliest available inscription, issued by the Wodeyars themselves, dates to the rule of the petty chief Timmaraja II in 1551.Stein (1989), p. 82

Autonomy: advances and reversals

The kings who followed ruled as vassals of the Vijayanagara Empire until the decline of the latter in 1565. By this time, the kingdom had expanded to thirty-three villages protected by a force of 300 soldiers. King Timmaraja II conquered some surrounding chiefdoms,Kamath (2001), p. 227 and King ''Bola'' Chamaraja IV (''lit'', "Bald"), the first ruler of any political significance among them, withheld tribute to the nominal Vijayanagara monarch Aravidu Ramaraya.Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 67 After the death of Aravidu Ramaraya, the Wodeyars began to assert themselves further and King Raja Wodeyar I wrested control ofSrirangapatna

Srirangapatna or Srirangapattana is a town and headquarters of one of the seven Taluks of Mandya district, in the Indian State of Karnataka. It gets its name from the Ranganthaswamy temple consecrated around 984 CE. Later, under the Britis ...

from the Vijayanagara governor (''Mahamandaleshvara'') Aravidu Tirumalla – a development which elicited, if only ''ex post facto'', the tacit approval of Venkatapati Raya

Venkatapati Raya ( – October 1614), also known as Venkata II, was the third Emperor of Vijayanagara from the Aravidu Dynasty. He succeeded his older brother, the Emperor Sriranga Deva Raya as the ruler of Vijayanagara Empire with bases in Penu ...

, the incumbent king of the diminished Vijayanagar Empire ruling from Chandragiri

Chandragiri is a suburb and outgrowth of Tirupati and located in Tirupati district of the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh. It is a part of Tirupati urban agglomeration and a major growing residential area in Tirupati It is the mandal headquarter ...

.Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 68 Raja Wodeyar I's reign also saw territorial expansion with the annexation of Channapatna

Channapattana or Chennapattana is a city and taluk headquarters in Bengaluru South District, Karnataka, India. Channapatna is approximately 60 km from Bangalore and 80 km from Mysore. Channapatna toys are popular all over the world ...

to the north from Jaggadeva Raya – a development which made Mysore a regional political factor to reckon with.Shama Rao in Kamath (2001), p. 227

Consequently, by 1612–13, the Wodeyars exercised a great deal of autonomy and even though they acknowledged the nominal overlordship of the Aravidu dynasty

The Aravidu Dynasty was the fourth and last Hindu dynasty of Vijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire, also known as the Karnata Kingdom, was a late medieval Hinduism, Hindu empire that ruled much of southern India. It was establish ...

, tributes and transfers of revenue to Chandragiri stopped. This was in marked contrast to other major chiefs, the '' Nayaks'' of Tamil country who continued to pay off Chandragiri emperors well into the 1630s. Chamaraja VI and Kanthirava Narasaraja I

Kanthirava Narasaraja Wodeyar I (1615 – 31 July 1659) was the twelfth Maharaja of Mysore, maharaja of the Kingdom of Mysore from 1638 to 1659.

Accession

The previous ruler, Raja Wodeyar II, Kanthirava Narasaraja Wodeyar's cousin, was poisone ...

attempted to expand further northward but were thwarted by the Bijapur Sultanate

The Sultanate of Bijapur was an early modern kingdom in the western Deccan and South India, ruled by the Muslim Adil Shahi (or Adilshahi) dynasty. Bijapur had been a '' taraf'' (province) of the Bahmani Kingdom prior to its independence in 14 ...

and its Maratha subordinates, though the Bijapur armies under Ranadullah Khan were effectively repelled in their 1638 siege of Srirangapatna.Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p.201Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 68; Kamath (2001), p. 228 Expansionist ambitions then turned southward into Tamil country where Narasaraja Wodeyar acquired Satyamangalam (in modern northern Erode

Erode (; īrōṭu), is a city in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Kaveri river and is surrounded by the Western Ghats. Erode is the seventh largest urban agglomeration in Tamil Nadu. It is the administrativ ...

district) while his successor Dodda Devaraja Wodeyar expanded further to capture western Tamil regions of Erode and Dharmapuri

Dharmapuri is a city in the north western part of Tamil Nadu, India. It serves as the administrative headquarters of Dharmapuri district which is the first district created in Tamil Nadu after the independence of India by splitting it from ...

, after successfully repulsing the chiefs of Madurai

Madurai ( , , ), formerly known as Madura, is a major city in the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is the cultural capital of Tamil Nadu and the administrative headquarters of Madurai District, which is ...

. The invasion of the Keladi Nayaka

Nayakas of Keladi () (1499–1763), also known as Nayakas of Bednore () and Ikkeri Nayakas (), were an Indian dynasty based in Keladi in present-day Shimoga district of Karnataka, India. They were an important ruling dynasty in post-mediev ...

s of Malnad

Malnad (or Malenadu) is a region in the state of Karnataka, India. Malenadu covers the western and eastern slopes of the Western Ghats mountain range and is roughly 100 kilometers in width. It includes the districts of Uttara Kannada, Shivam ...

was also dealt with successfully. This period was followed by one of the complex geo-political changes when in the 1670s, the Marathas and the Mughals pressed into the Deccan.

Chikka Devaraja

Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II (22 September 1645 – 16 November 1704) was the fourteenth maharaja of the Kingdom of Mysore from 1673 to 1704. During this time, Mysore saw further significant expansion after his predecessors. During his rule, cent ...

(r. 1672–1704), the most notable of Mysore's early kings, who ruled during much of this period, managed to not only survive the exigencies but further expand territory. He achieved this by forging strategic alliances with the Marathas and the Mughals

The Mughal Empire was an early modern empire in South Asia. At its peak, the empire stretched from the outer fringes of the Indus River Basin in the west, northern Afghanistan in the northwest, and Kashmir in the north, to the highlands of pre ...

.Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 71Kamath (2001), pp. 228–229 The kingdom soon grew to include Salem and Bangalore

Bengaluru, also known as Bangalore (List of renamed places in India#Karnataka, its official name until 1 November 2014), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the southern States and union territories of India, Indian state of Kar ...

to the east, Hassan to the west, Chikkamagaluru

Chikmagalur (officially Chikkamagaluru, ), previously known as ''Kiriya-Muguli'' is a city and the headquarters of Chikmagalur district in the Indian state of Karnataka. Located on the foothills of the Mullayanagiri, Mullayanagiri peak of the We ...

and Tumkur

Tumkur, officially Tumakuru, is a city and headquarters of Tumakuru district in the Karnataka state of India. Tumkur is known for Siddaganga Matha. Tumkur hosts India's first mega food park, a project of the ministry of food processing. The Ind ...

to the north and the rest of Coimbatore

Coimbatore (Tamil: kōyamputtūr, ), also known as Kovai (), is one of the major Metropolitan cities of India, metropolitan cities in the States and union territories of India, Indian state of Tamil Nadu. It is located on the banks of the Noyy ...

to the south.Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 69; Kamath (2001), pp. 228–229 Despite this expansion, the kingdom, which now accounted for a fair share of land in the southern Indian heartland, extending from the Western Ghats to the western boundaries of the Coromandel

Coromandel may refer to:

Places India

*Coromandel Coast, India

** Presidency of Coromandel and Bengal Settlements

**Dutch Coromandel

* Coromandel, KGF, Karnataka, India

New Zealand

*Coromandel, New Zealand, a town on the Coromandel Peninsula

*Cor ...

plain, remained landlocked without direct coastal access. Chikka Devaraja's attempts to remedy this brought Mysore into conflict with the ''Nayaka'' chiefs of Ikkeri and the kings (''Rajas'') of Kodagu

Kodagu district () (also known by its former name Coorg) is an administrative List of districts of Karnataka, district in the Karnataka state of India. Before 1956, it was an administratively separate Coorg State at which point it was merged ...

(modern Coorg); who between them controlled the Kanara

Kanara or Canara, also known as Karāvali, is the historically significant stretch of land situated by the southwestern Konkan coast of India, alongside the Arabian Sea in the present-day Indian state of Karnataka.

The subregion comprises thr ...

coast (coastal areas of modern Karnataka) and the intervening hill region respectively.Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 69 The conflict brought mixed results with Mysore annexing Periyapatna

Periyapatna, also known as Piriyāpattana, is a town in Mysore district. It is known for being a major producer of tobacco, and is called 'the land of tobacco'. There are popular temples in Periyapatna, the Kannambadi Amma and Masanikamma templ ...

but suffering a reversal at Palupare.Subrahmanyam (2001), p. 70

Nevertheless, from around 1704, when the kingdom passed on to the "Mute king" (''Mukarasu'') Kanthirava Narasaraja II, the survival and expansion of the kingdom was achieved by playing a delicate game of alliance, negotiation, subordination on occasion, and annexation of territory in all directions. According to historians Sanjay Subrahmanyam

Sanjay Subrahmanyam (born 21 May 1961) is an Indian American historian of the early modern period. He is the author of several books and publications. He holds the Irving and Jean Stone Endowed Chair in Social Sciences at UCLA which he joined i ...

and Sethu Madhava Rao, Mysore was now formally a tributary of the Mughal Empire. Mughul records claim a regular tribute (''peshkash'') was paid by Mysore. However, historian Suryanath U. Kamath feels the Mughals may have considered Mysore an ally, a situation brought about by Mughal–Maratha competition for supremacy in southern India.Subrahmanyam (2001), pp. 70–71; Kamath (2001), p. 229 By the 1720s, with the Mughal empire in decline, further complications arose with the Mughal residents at both Arcot

Arcot (natively spelt as Ārkāḍu) is a town and urban area of Ranipet district in the Indian state of Tamil Nadu. Located on the southern banks of Palar River, the city straddles a trade route between Chennai and Bangalore or Salem, betwe ...

and Sira claiming tribute. The years that followed saw Krishnaraja Wodeyar I tread cautiously on the matter while keeping the Kodagu chiefs and the Marathas at bay. He was followed by Chamaraja Wodeyar VII

Chamaraja Wodeyar VII (1704–1734) was the seventeenth maharaja of the Kingdom of Mysore. He nominally ruled from 1732 to 1734.

Adoption and coronation

He was son of Devaraj Urs of Ankanhalli and adopted by Maharani Devajamma and Maharaja ...

during whose reign power fell into the hands of prime minister (''Dalwai'' or ''Dalavoy'') Nanjarajiah (or Nanjaraja) and chief minister (''Sarvadhikari'') Devarajiah (or Devaraja), the influential brothers from Kalale town near Nanjangud

Nanjangud, officially known as Nanjanagudu, is a town in the Mysuru district of the Indian state of Karnataka. Nanjangud lies on the banks of the river Kapila (also called Kabini), 23 km from the city of Mysore. Nanjangud is famous for the ...

who would rule for the next three decades with the Wodeyars relegated to being the titular heads.Pranesh (2003), pp. 44–45Kamath (2001), p. 230 The latter part of the rule of Krishnaraja II saw the Deccan Sultanates

The Deccan sultanates is a historiographical term referring to five late medieval to early modern Persianate Indian Muslim kingdoms on the Deccan Plateau between the Krishna River and the Vindhya Range. They were created from the disintegrati ...

being eclipsed by the Mughals and in the confusion that ensued, Hyder Ali

Hyder Ali (''Haidar'alī''; ; 1720 – 7 December 1782) was the Sultan and ''de facto'' ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. Born as Hyder Ali, he distinguished himself as a soldier, eventually drawing the attention of Mysore's ...

, a captain in the army, rose to prominence. His victory against the Marathas at Bangalore in 1758, resulting in the annexation of their territory, made him an iconic figure. In honour of his achievements, the king gave him the title "Nawab Haider Ali Khan Bahadur".

Under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan

Hyder Ali

Hyder Ali (''Haidar'alī''; ; 1720 – 7 December 1782) was the Sultan and ''de facto'' ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. Born as Hyder Ali, he distinguished himself as a soldier, eventually drawing the attention of Mysore's ...

has earned an important place in the history of Karnataka

The History of Karnataka goes back several millennia. Several great empires and dynasties have ruled over Karnataka and have contributed greatly to the history, culture and development of Karnataka as well as the entire Indian subcontinent. Th ...

for his fighting skills and administrative acumen.Shama Rao in Kamath (2001), p. 233Quote: "A military genius and a man of vigour, valour and resourcefulness" (Chopra et al. 2003, p. 76) The rise of Hyder came at a time of important political developments in the sub-continent. While the European powers were busy transforming themselves from trading companies to political powers, the Nizam

Nizam of Hyderabad was the title of the ruler of Hyderabad State ( part of the Indian state of Telangana, and the Kalyana-Karnataka region of Karnataka). ''Nizam'' is a shortened form of (; ), and was the title bestowed upon Asaf Jah I ...

as the ''Subahdar

Subahdar, also known as Nazim, was one of the designations of a governor of a Subah (province) during the Khalji dynasty of Bengal, Mamluk dynasty, Khalji dynasty, Tughlaq dynasty, and the Mughal era who was alternately designated as Sahib- ...

'' of the Mughals pursued his ambitions in the Deccan, and the Marathas, following their defeat at Panipat

Panipat () is an industrial , located 95 km north of Delhi and 169 km south of Chandigarh on NH-44 in Panipat district, Haryana, India. It is famous for three major battles fought in 1526, 1556 and 1761. The city is also known as ...

, sought safe havens in the south. The period also saw the French vie with the British for control of the Carnatic—a contest in which the British would eventually prevail as British commander Sir Eyre Coote decisively defeated the French under the Comte de Lally at the Battle of Wandiwash

The Battle of Wandiwash was a battle in India between the French and the British in 1760. The battle was part of the Third Carnatic War fought between the French and British colonial empires, which itself was a part of the global Seven Years' ...

in 1760, a watershed in Indian history as it cemented British supremacy in South Asia.Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 207 Though the Wodeyars remained the nominal heads of Mysore during this period, real power lay in the hands of Hyder Ali and his son Tipu.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 71, 76

By 1761, Maratha power had diminished and by 1763, Hyder Ali had captured the Keladi kingdom, defeated the rulers of Bilgi, Bednur and Gutti, invaded the Malabar Coast

The Malabar Coast () is the southwestern region of the Indian subcontinent. It generally refers to the West Coast of India, western coastline of India stretching from Konkan to Kanyakumari. Geographically, it comprises one of the wettest regio ...

in the south and conquered the Zamorin

The Samoothiri (Anglicised as Zamorin; Malayalam: , , Arabic: ''Sāmuri'', Portuguese: ''Samorim'', Dutch: ''Samorijn'', Chinese: ''Shamitihsi''Ma Huan's Ying-yai Sheng-lan: 'The Overall Survey of the Ocean's Shores' 433 Translated and Edi ...

's capital Calicut

Kozhikode (), also known as Calicut, is a city along the Malabar Coast in the state of Kerala in India. Known as the City of Spices, Kozhikode is listed among the City of Literature, UNESCO's Cities of Literature.

It is the nineteenth large ...

with ease in 1766 and extended the Mysore kingdom up to Dharwad

Dharwad (), also known as Dharwar, is a city located in the northwestern part of the Indian state of Karnataka. It is the headquarters of the Dharwad district of Karnataka and forms a contiguous urban area with the city of Hubballi. It was merged ...

and Bellary

Ballari (formerly Bellary) is a city in the Ballari district in state of Karnataka, India.

Ballari houses many steel plants such as JSW Vijayanagar, one of the largest in Asia. Ballari district is also known as the ‘Steel city of South Ind ...

in the north.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 55Kamath (2001), p. 232 Mysore was now a major political power in the subcontinent and Haider's meteoric rise from relative obscurity and his defiance formed one of the last remaining challenges to complete British hegemony over the Indian subcontinent—a challenge which would take them more than three decades to overcome.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 71

In a bid to stem Hyder's rise, the British allied with the Marathas and the Nizam of Golconda

Golconda is a fortified citadel and ruined city located on the western outskirts of Hyderabad, Telangana, India. The fort was originally built by Kakatiya ruler Pratāparudra in the 11th century out of mud walls. It was ceded to the Bahmani ...

, culminating in the First Anglo-Mysore War

The First Anglo-Mysore War (1767–1769) was a conflict in Mughal India, India between the Sultanate of Mysore and the East India Company. The war was instigated in part by the machinations of Nizam Ali Khan, Asaf Jah II, Asaf Jah II, the Niz ...

in 1767. Despite numerical superiority, Hyder Ali suffered defeats at the battles of Chengham and Tiruvannamalai

Tiruvannamalai (Tamil: ''Tiruvaṇṇāmalai'' IPA: , otherwise spelt ''Thiruvannamalai''; ''Trinomali'' or ''Trinomalee'' on British records) is a city and the administrative headquarters of Tiruvannamalai District in the Indian state of ...

. The British ignored his overtures for peace until Hyder Ali had strategically moved his armies to within five miles of Madras (modern Chennai

Chennai, also known as Madras (List of renamed places in India#Tamil Nadu, its official name until 1996), is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Tamil Nadu by population, largest city of Tamil Nadu, the southernmost states and ...

) and was able to successfully sue for peace

Suing for peace is an act by a warring party to initiate a peace process.

Rationales

"Suing for", in this older sense of the phrase, means "pleading or petitioning for". Suing for peace is usually initiated by the losing party in an attempt to ...

.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 73 Three wars were fought from 1764 and 1772 between the Maratha armies of Peshwa Madhavrao I against Hyder, in which Hyder was severely defeated and had to pay 36 lacs of tribute as war expenses along with an annual tribute of 14 lacs every year to the peshwa. In these wars Hyder had expected British support as per the 1769 treaty but the British betrayed him by staying out of the conflict. The British betrayal and Hyder's subsequent defeat reinforced Hyder's deep distrust of the British—a sentiment that would be shared by his son and one that would inform Anglo-Mysore rivalries of the next three decades. In 1777, Haider Ali recovered the previously lost territories of Coorg and parts of what would later become Malabar District from the Marathas.

Haider Ali's army advanced towards the Marathas and fought them at the Battle of Saunshi

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force c ...

and came out victorious during the same year.

By 1779, Hyder Ali had captured parts of modern Tamil Nadu and Kerala

Kerala ( , ) is a States and union territories of India, state on the Malabar Coast of India. It was formed on 1 November 1956, following the passage of the States Reorganisation Act, by combining Malayalam-speaking regions of the erstwhile ...

in the south, extending the Kingdom's area to about 80,000 mi2 (205,000 km2). In 1780, he befriended the French and made peace with the Marathas and the Nizam.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 74 However, Hyder Ali was betrayed by the Marathas and the Nizam, who made treaties with the British as well. In July 1779, Hyder Ali headed an army of 80,000, mostly cavalry, descending through the passes of the Ghats amid burning villages, before laying siege to British forts in northern Arcot starting the Second Anglo-Mysore War

The Second Anglo-Mysore War was a conflict between the Kingdom of Mysore and the British East India Company from 1780 to 1784. At the time, Mysore was a key French ally in India, and the conflict between Britain against the French and Dutch in t ...

. Hyder Ali had some initial successes against the British notably at Pollilur, the worst defeat the British suffered in India until Chillianwala, and Arcot, until the arrival of Sir Eyre Coote, when the fortunes of the British began to change.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 75 On 1 June 1781 Coote struck the first heavy blow against Hyder Ali in the decisive Battle of Porto Novo. The battle was won by Coote against odds of five to one and is regarded as one of the greatest feats of the British in India. It was followed up by another hard-fought battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

at Pollilur (the scene of an earlier triumph of Hyder Ali over a British force) on 27 August, in which the British won another success, and by the rout of the Mysore troops at Sholinghur

}

Sholinghapuram, shortened to Sholinghur (in Tamil: சோளிங்கப்புரம் or சோளிங்கர்) is a municipality under Sholinghur taluk in Ranipet District, Vellore region of Tamil Nadu, India. The town is fam ...

a month later. Hyder Ali died on 7 December 1782, even as fighting continued with the British. He was succeeded by his son Tipu Sultan who continued hostilities against the British by recapturing Baidanur and Mangalore.Chopra et al. 2003, p. 75

By 1783 neither the British nor Mysore were able to obtain a clear overall victory. The French withdrew their support of Mysore following the peace settlement in Europe. Undaunted, Tipu, popularly known as the "Tiger of Mysore", continued the war against the British but lost some regions in modern coastal Karnataka to them. The Maratha–Mysore War occurred between 1785 and 1787 and consisted of a series of conflicts between the Sultanate of Mysore and the Maratha Empire. Following Tipu Sultan's victory against the Marathas at the siege of Bahadur Benda

The siege of Bahadur Benda occurred when the forces of Mysore led by Tipu Sultan besieged Bahadur fort in 1787. Tipu Sultan defeated the Maratha Army led by Hari Pant and captured the fort located in present-day Ahmednagar district in Maharashtr ...

, a peace agreement was signed between the two kingdoms with mutual gains and losses. Similarly, the treaty of Mangalore

The Treaty of Mangalore was signed between Tipu Sultan and the British East India Company on 11 March 1784. It was signed in Mangaluru and brought an end to the Second Anglo-Mysore War.

Background

Hyder Ali became dalwai Dalavayi of Mysore b ...

was signed in 1784 bringing hostilities with the British to a temporary and uneasy halt and restoring the others' lands to the status quo ante bellum

The term is a Latin phrase meaning 'the situation as it existed before the war'.

The term was originally used in treaties to refer to the withdrawal of enemy troops and the restoration of prewar leadership. When used as such, it means that no ...

.Chopra et al. (2003), pp. 75–76 The treaty is an important document in the history of India because it was the last occasion when an Indian power dictated terms to the British, who were made to play the role of humble supplicants for peace. A start of fresh hostilities between the British and French in Europe would have been sufficient reason for Tipu to abrogate his treaty and further his ambition of striking at the British.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 77 His attempts to lure the Nizam, the Marathas, the French and the Sultan of Turkey failed to bring direct military aid.

Tipu's successful attacks in 1790 on the

Tipu's successful attacks in 1790 on the kingdom of Travancore

The asterisk ( ), from Late Latin , from Ancient Greek , , "little star", is a typographical symbol. It is so called because it resembles a conventional image of a heraldic star.

Computer scientists and mathematicians often vocalize it as st ...

, a later British ally, ended in defeat for him, and it resulted in greater hostilities with the British which culminated in the Third Anglo-Mysore War

The Third Anglo-Mysore War (1790–1792) was a conflict in South India between the Kingdom of Mysore and the British East India Company, the Travancore, Kingdom of Travancore, the Maratha Empire, Maratha Confederacy, and the Nizam of Hyderabad ...

. In the beginning, the British made gains, taking the Coimbatore district

Coimbatore District is one of the 38 districts in the state of Tamil Nadu in India. Coimbatore is the administrative headquarters of the district. It is one of the most industrialized districts and a major textile, industrial, commercial, educa ...

, but Tipu's counterattack reversed many of these gains. By 1792, with aid from the Marathas who attacked from the north-west and the Nizam who moved in from the north-east, the British under Lord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805) was a British Army officer, Whigs (British political party), Whig politician and colonial administrator. In the United States and United Kingdom, he is best kn ...

successfully besieged Srirangapatna, resulting in Tipu's defeat and the Treaty of Srirangapatna. Half of Mysore was distributed among the allies, and two of his sons were held to ransom.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 78–79; Kamath (2001), p. 233 A humiliated but indomitable Tipu went about rebuilding his economic and military power. He attempted to covertly win over support from Revolutionary France, the Amir

Emir (; ' (), also transliterated as amir, is a word of Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person possessing actual or ceremonial authority. The title has ...

of Afghanistan, the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

and Arabia. However, these attempts to involve the French soon became known to the British, who were at the time fighting the French in Egypt

Egypt ( , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a country spanning the Northeast Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to northe ...

and were backed by the Marathas and the Nizam. In 1799, Tipu died defending Srirangapatna in the Fourth Anglo-Mysore War

The Fourth Anglo-Mysore War was a conflict in South India between the Kingdom of Mysore against the British East India Company and the Hyderabad Deccan in 1798–99.

This was the last of the four Anglo-Mysore Wars. The British captured the capi ...

, heralding the end of the Kingdom's independence.Chopra et al. (2003), pp. 79–80; Kamath (2001), pp. 233–234 Modern Indian historians consider Tipu Sultan an inveterate enemy of the British, an able administrator and an innovator.Chopra et al. (2003), pp. 81–82

Princely state

Following Tipu's fall, a part of the kingdom of Mysore was annexed and divided between the Madras Presidency and theNizam

Nizam of Hyderabad was the title of the ruler of Hyderabad State ( part of the Indian state of Telangana, and the Kalyana-Karnataka region of Karnataka). ''Nizam'' is a shortened form of (; ), and was the title bestowed upon Asaf Jah I ...

. The remaining territory was transformed into a Princely State; the five-year-old scion of the Wodeyar family, Krishnaraja III, was installed on the throne with Purnaiah

Krishnacharya Purnaiah (1746 – 27 March 1812), popularly known as Dewan Purnaiah, was an Indian administrator, statesman, and military strategist who served as the first dewan of Mysore from 1782 to 1811. He was instrumental in the restorati ...

continuing as Dewan

''Dewan'' (also known as ''diwan'', sometimes spelled ''devan'' or ''divan'') designated a powerful government official, minister, or ruler. A ''dewan'' was the head of a state institution of the same name (see Divan). Diwans belonged to the el ...

, who had earlier served under Tipu, handling the reins as regent and Barry Close was appointed the British Resident

A resident minister, or resident for short, is a government official required to take up permanent residence in another country. A representative of his government, he officially has diplomatic functions which are often seen as a form of in ...

for Msyore. The British then took control of Mysore's foreign policy and also exacted an annual tribute and a subsidy for maintaining a standing British army at Mysore.Kamath (2001), p. 249Kamath (2001), p. 234 As dewan, Purnaiah distinguished himself with his progressive and innovative administration until he retired from service in 1811 (and died shortly thereafter) following the 16th birthday of the boy king.Quote: "The Diwan seems to pursue the wisest and the most benevolent course for the promotion of industry and opulence" (Gen. Wellesley in Kamath 2001, p. 249)

The years that followed witnessed cordial relations between Mysore and the British until things began to sour in the 1820s. Even though the

The years that followed witnessed cordial relations between Mysore and the British until things began to sour in the 1820s. Even though the Governor of Madras

This is a list of the governors, agents, and presidents of colonial Madras, initially of the English East India Company, up to the end of British colonial rule in 1947.

English Agents

In 1639, the grant of Madras to the English was finalized ...

, Thomas Munro

Major-General Sir Thomas Munro, 1st Baronet KCB (27 May 17616 July 1827) was a Scottish soldier and British colonial administrator. He served as an East India Company Army officer and statesman, in addition to also being the governor of Mad ...

, determined after a personal investigation in 1825 that there was no substance to the allegations of financial impropriety made by A. H. Cole, the incumbent Resident of Mysore, the Nagar revolt (a civil insurrection) which broke out towards the end of the decade changed things considerably. In 1831, close on the heels of the insurrection and citing mal-administration, the British took direct control of the princely state, placing it under a commission rule.Kamath (2001), p. 250 For the next fifty years, Mysore passed under the rule of successive British Commissioners; Sir Mark Cubbon, renowned for his statesmanship, served from 1834 until 1861 and put into place an efficient and successful administrative system which left Mysore a well-developed state.

In 1876–77, however, towards the end of the period of direct British rule, Mysore was struck by a devastating famine with estimated mortality figures ranging between 700,000 and 1,100,000, or nearly a fifth of the population. Shortly thereafter, Maharaja Chamaraja X, educated in the British system, took over the rule of Mysore in 1881, following the success of a lobby set up by the Wodeyar dynasty that was in favour of rendition. Accordingly, a resident British officer was appointed at the Mysore court and a Dewan to handle the Maharaja's administration.Kamath (2001), pp. 250–254 From then onwards, until Indian independence in 1947, Mysore remained a Princely State within the

In 1876–77, however, towards the end of the period of direct British rule, Mysore was struck by a devastating famine with estimated mortality figures ranging between 700,000 and 1,100,000, or nearly a fifth of the population. Shortly thereafter, Maharaja Chamaraja X, educated in the British system, took over the rule of Mysore in 1881, following the success of a lobby set up by the Wodeyar dynasty that was in favour of rendition. Accordingly, a resident British officer was appointed at the Mysore court and a Dewan to handle the Maharaja's administration.Kamath (2001), pp. 250–254 From then onwards, until Indian independence in 1947, Mysore remained a Princely State within the British Indian Empire

The British Raj ( ; from Hindustani language, Hindustani , 'reign', 'rule' or 'government') was the colonial rule of the British The Crown, Crown on the Indian subcontinent,

*

* lasting from 1858 to 1947.

*

* It is also called Crown rule ...

, with the Wodeyars continuing their rule.

After the demise of Maharaja Chamaraja X, Krishnaraja IV, still a boy of eleven, ascended the throne in 1895. His mother Maharani Kemparajammanniyavaru ruled as regent until Krishnaraja took over the reins on 8 February 1902. Under his rule, with Sir M. Visvesvayara as his Dewan, the Maharaja set about transforming Mysore into a progressive and modern state, particularly in industry, education, agriculture and art. Such were the strides that Mysore made that Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

called the Maharaja a "saintly king" (''Rajarishi''). Paul Brunton

Paul Brunton is the pen name of Raphael Hurst (21 October 1898 – 27 July 1981), a British author of spiritual books. He is best known as one of the early popularizers of Neo-Hindu spiritualism in western esotericism, notably via his be ...

, the British philosopher and orientalist, John Gunther

John Gunther (August 30, 1901 – May 29, 1970) was an Americans, American journalist and writer.

His success came primarily by a series of popular sociopolitical works, known as the "Inside" books (1936–1972), including the best-sell ...

, the American author, and British statesman Lord Samuel praised the ruler's efforts. Much of the pioneering work in educational infrastructure that took place during this period would serve Karnataka invaluably in the coming decades. The Maharaja was an accomplished musician, and like his predecessors, avidly patronised the development of the fine arts.Pranesh (2003), p. 162 He was followed by his nephew Jayachamarajendra whose rule continued for some years after he signed the instrument of accession

The Instrument of Accession was a legal document first introduced by the Government of India Act 1935 and used in 1947 to enable each of the rulers of the princely states under British paramountcy to join one of the new dominions of Dominion ...

and Mysore joined the Indian Union on 9 August 1947.Kamath (2001), p. 261 Jayachamarajendra continued to rule as Rajapramukh of Mysore until 1956 when as a result of the States Reorganisation Act, 1956

The States Reorganisation Act, 1956 was a major reform of the boundaries of India's states and territories, organising them along linguistic lines.

Although additional changes to India's state boundaries have been made since 1956, the States ...

, his position was converted into Governor of Mysore State. From 1963 until 1966, he was the first Governor of Madras State

Madras State was a state in the Indian Republic, which was in existence during the mid-20th century as a successor to the Madras Presidency of British India. The state came into existence on 26 January 1950 when the Constitution of India was ad ...

.''Asian Recorder'', Volume 20 (1974), p. 12263

Administration

There are no records relating to the administration of the Mysore territory during theVijayanagara Empire

The Vijayanagara Empire, also known as the Karnata Kingdom, was a late medieval Hinduism, Hindu empire that ruled much of southern India. It was established in 1336 by the brothers Harihara I and Bukka Raya I of the Sangama dynasty, belongi ...

's reign (1399–1565). Signs of a well-organised and independent administration appear from the time of Raja Wodeyar I who is believed to have been sympathetic towards peasants (''raiyat

Ryot (alternatives: raiyat, rait or ravat) was a general economic term used throughout India for peasant cultivators but with variations in different provinces. While zamindars were landlords, raiyats were tenants and cultivators, and served as hi ...

s'') who were exempted from any increases in taxation during his time. The first sign that the kingdom had established itself in the area was the issuing of gold coins (''Kanthirayi phanam'') resembling those of the erstwhile Vijayanagara Empire during Narasaraja Wodeyar's rule.Kamath (2001), p. 228; Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 201

The rule of Chikka Devaraja saw several reforms effected. Internal administration was remodelled to suit the kingdom's growing needs and became more efficient. A postal system came into being. Far-reaching financial reforms were also introduced. Several petty taxes were imposed in place of direct taxes, as a result of which the peasants were compelled to pay more by way of land tax. The king is said to have taken a personal interest in the regular collection of revenues the treasury burgeoned to 90,000,000 ''Pagoda

A pagoda is a tiered tower with multiple eaves common to Thailand, Cambodia, Nepal, India, China, Japan, Korea, Myanmar, Vietnam, and other parts of Asia. Most pagodas were built to have a religious function, most often Buddhist, but some ...

'' (a unit of currency) – earning him the epithet "Nine crore

Crore (; abbreviated cr) denotes the quantity ten million (107) and is equal to 100 lakh in the Indian numbering system. In many international contexts, the decimal quantity is formatted as 10,000,000, but when used in the context of the India ...

Narayana" (''Navakoti Narayana''). In 1700, he sent an embassy to Aurangazeb

Alamgir I (Muhi al-Din Muhammad; 3 November 1618 – 3 March 1707), commonly known by the title Aurangzeb, also called Aurangzeb the Conqueror, was the sixth Mughal emperors, Mughal emperor, reigning from 1658 until his death in 1707, becomi ...

's court bestowed upon him the title ''Jug Deo Raja'' and awarded permission to sit on the ivory throne. Following this, he founded the district offices (''Attara Kacheri''), the central secretariat comprising eighteen departments, and his administration was modelled on Mughal lines.Kamath (2001), pp. 228–229; Venkata Ramanappa, M. N. (1975), p. 203

During Hyder Ali

Hyder Ali (''Haidar'alī''; ; 1720 – 7 December 1782) was the Sultan and ''de facto'' ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore in southern India. Born as Hyder Ali, he distinguished himself as a soldier, eventually drawing the attention of Mysore's ...

's rule, the kingdom was divided into five provinces (''Asofis'') of unequal size, comprising 171 taluk

A tehsil (, also known as tahsil, taluk, or taluka () is a local unit of administrative division in India and Pakistan. It is a subdistrict of the area within a district including the designated populated place that serves as its administrative ...

s ('' Paraganas'') in total.Kamath (2001), p. 233 When Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan (, , ''Sultan Fateh Ali Sahab Tipu''; 1 December 1751 – 4 May 1799) commonly referred to as Sher-e-Mysore or "Tiger of Mysore", was a ruler of the Kingdom of Mysore based in South India. He was a pioneer of rocket artillery ...

became the ''de facto'' ruler, the kingdom, which encompassed (62,000 mi2), was divided into 37 provinces and a total of 124 taluks (''Amil''). Each province had a governor (''Asof''), and one deputy governor. Each taluk had a headman called ''Amildar'' and a group of villages were in charge of a ''Patel

Patel is an Indian surname or Indian honorifics, title, predominantly found in the States and union territories of India, state of Gujarat, representing the community of land-owning farmers and later (with the British East India Company) busine ...

''. The central administration comprised six departments headed by ministers, each aided by an advisory council of up to four members.Kamath (2001), p. 235

When the princely state came under direct British rule in 1831, early commissioners Lushington, Briggs and Morrison were followed by Mark Cubbon, who took charge in 1834.Kamath (2001), p. 251 He made Bangalore

Bengaluru, also known as Bangalore (List of renamed places in India#Karnataka, its official name until 1 November 2014), is the Capital city, capital and largest city of the southern States and union territories of India, Indian state of Kar ...

the capital and divided the princely state into four divisions, each under a British superintendent. The state was further divided into 120 taluks with 85 taluk courts, with all lower level administration in the Kannada language

Kannada () is a Dravidian languages, Dravidian language spoken predominantly in the state of Karnataka in southwestern India, and spoken by a minority of the population in all neighbouring states. It has 44 million native speakers, an ...

. The office of the commissioner had eight departments; revenue, post, police, cavalry, public works, medical, animal husbandry, judiciary and education. The judiciary was hierarchical with the commissioners' court at the apex, followed by the ''Huzur Adalat'', four superintending courts and eight ''Sadar Munsiff'' courts at the lowest level.Kamath (2001), p. 252 Lewin Bowring became the chief commissioner in 1862 and held the position until 1870. During his tenure, the property "Registration Act", the "Indian Penal Code

The Indian Penal Code (IPC) was the official criminal code of the Republic of India, inherited from British India after independence. It remained in force until it was repealed and replaced by the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) in December 2023 ...

" and " Code of Criminal Procedure" came into effect and the judiciary was separated from the executive branch of the administration. The state was divided into eight districts

A district is a type of administrative division that in some countries is managed by the local government. Across the world, areas known as "districts" vary greatly in size, spanning regions or counties, several municipalities, subdivisions ...

– Bangalore, Chitraldroog, Hassan, Kadur

Kaduru, also known as Kadur, is a town in the district and a taluk in Chikmagalur district, in Karnataka. It is located at in the rain shadow region of western ghats in the Malenadu region. Most of the taluk is dry, unlike much of the distri ...

, Kolar

Kolar may refer to:

Places India

* Kolar, Karnataka, a city in India

**Kolar Assembly constituency

*Kolar district, in Karnataka, India

*Kolar Gold Fields, former gold mines in Karnataka, India

**KGF (disambiguation)

**Kolar Gold Field Assembly co ...

, Mysore

Mysore ( ), officially Mysuru (), is a city in the southern Indian state of Karnataka. It is the headquarters of Mysore district and Mysore division. As the traditional seat of the Wadiyar dynasty, the city functioned as the capital of the ...

, Shimoga

Shimoga, officially Shivamogga, is a city and the district headquarters of Shimoga district in the Karnataka state of India. The city lies on the banks of the Tunga River. Being the gateway for the hilly region of the Western Ghats, the city ...

, and Tumkur

Tumkur, officially Tumakuru, is a city and headquarters of Tumakuru district in the Karnataka state of India. Tumkur is known for Siddaganga Matha. Tumkur hosts India's first mega food park, a project of the ministry of food processing. The Ind ...

.

After the rendition, C. V. Rungacharlu was made the Dewan. Under him, the first Representative Assembly of British India, with 144 members, was formed in 1881.Kamath (2001), p. 254 He was followed by K. Seshadri Iyer in 1883 during whose tenure gold mining at the Kolar Gold Fields

Kolar Gold Fields (K.G.F.) is a mining region in K.G.F. taluk (township), Kolar district, Karnataka, India. It is headquartered in Robertsonpet, where employees of Bharat Gold Mines Limited (BGML) and BEML Limited (formerly Bharat Earth Mov ...

began, the Shivanasamudra

Shivanasamudra Falls is a cluster of waterfalls on the borders of Malavalli, Mandya and Kollegala, Chamarajanagara, in Karnataka, India, situated along the river Kaveri. The falls form the contour between the districts of Chamarajanagara and Ma ...

hydroelectric

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies 15% of the world's electricity, almost 4,210 TWh in 2023, which is more than all other Renewable energ ...

project was initiated in 1899 (the first such major attempt in India) and electricity and drinking water (the latter through pipes) was supplied to Bangalore.Kamath (2001), pp. 254–255 Seshadri Iyer was followed by P. N. Krishnamurti

Sir Purniah Narasinga Rao Krishnamurti, Order of the Indian Empire, KCIE (12 August 1849 – 1911) was an Indian lawyer and administrator who served as the 16th Dewan of Mysore from 1901 to 1906. He was the great-great grandson of Purnaiah, th ...

, who created The Secretariat Manual to maintain records and the Co-operative Department in 1905, V. P. Madhava Rao who focussed on the conservation of forests and T. Ananda Rao, who finalised the Kannambadi Dam project.Kamath (2001), p. 257

Sir Mokshagundam Visvesvaraya, popularly known as the "Maker of Modern Mysore", holds a key place in the history of Karnataka.Kamath (2001), p. 259 An engineer by education, he became the Dewan in 1909.Indian Science Congress (2003), p. 139 Under his tenure, membership of the Mysore Legislative Assembly

The Karnataka Legislative Assembly (formerly the Mysore Legislative Assembly) is the lower house of the Karnataka Legislature, bicameral legislature of the South India, southern Indian state of Karnataka. Karnataka is one of the six states in ...

was increased from 18 to 24, and it was given the power to discuss the state budget. The Mysore Economic Conference was expanded into three committees; industry and commerce, education, and agriculture, with publications in English and Kannada.Kamath (2001), p. 258 Important projects commissioned during his time included the construction of the Kannambadi Dam, the founding of the Mysore Iron Works at Bhadravathi, founding of the Mysore University

The University of Mysore is a public state university in Mysore, Karnataka, India. The university was founded during the reign of Maharaja Krishnaraja Wadiyar IV and the premiership of Sir M. Visvesvaraya. The university is recognised by t ...

in 1916, the University Visvesvaraya College of Engineering

UVCE (University of Visvesvaraya College of Engineering) is a premier public university under the Govt of Karnataka, at Bangalore. The Government of Karnataka, Govt of Karnataka has declared it as an Institution of State Eminence for its contri ...

in Bangalore, the establishment of the Mysore state railway department and numerous industries in Mysore. In 1955, he was awarded the Bharat Ratna

The Bharat Ratna (; ) is the highest Indian honours system, civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred in recognition of "exceptional service/performance of the highest order", without distin ...

, India's highest civilian honour.Indian Science Congress (2003), pp. 139–140

Sir Mirza Ismail took office as Dewan in 1926 and built on the foundation laid by his predecessor. Amongst his contributions were the expansion of the Bhadravathi Iron Works, the founding of a cement and paper factory in Bhadravathi and the launch of Hindustan Aeronautics Limited

Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) is an Indian public sector aerospace and defence company, headquartered in Bengaluru. Established on 23 December 1940, HAL is one of the oldest and largest aerospace and defence manufacturers in the world. H ...

. A man with a penchant for gardens, he founded the Brindavan Gardens

The Brindavan Gardens is a garden located 12 k.ms from the city of Mysore in the Mandya District of the Indian States and territories of India, State of Karnataka. It lies adjoining the Krishna Raja Sagara, Krishnarajasagara Dam which is bu ...

(Krishnaraja Sagar) and built the Kaveri River

The Kaveri (also known as Cauvery) is a major river flowing across Southern India. It is the third largest river in the region after Godavari and Krishna.

The catchment area of the Kaveri basin is estimated to be and encompasses the states o ...

high-level canal to irrigate in modern Mandya district.Kamath (2001), p. 260

In 1939 Mandya District

Mandya district is an administrative district of Karnataka, India. The district Mandya was carved out of larger Mysore district in the year 1939.

Mandya is the main town in Mandya district. As of 2011, the district population was 1,808,680 ...

was carved out of Mysore District, bringing the number of districts in the state to nine.

Economy

The vast majority of the people lived in villages and agriculture was their main occupation. The economy of the kingdom was based on agriculture. Grains, pulses, vegetables and flowers were cultivated. Commercial crops included sugarcane and cotton. The agrarian population consisted of landlords (''vokkaliga

Vokkaliga (also transliterated as Vokkaligar, Vakkaliga, Wakkaliga, Okkaligar, Okkiliyan) is a community of closely related castes, from the Indian states of Karnataka and Tamil Nadu.

As a community of warriors and cultivators they have historical ...

'', ''zamindar

A zamindar in the Indian subcontinent was an autonomous or semi-autonomous feudal lord of a ''zamindari'' (feudal estate). The term itself came into use during the Mughal Empire, when Persian was the official language; ''zamindar'' is the ...

'', '' heggadde'') who tilled the land by employing several landless labourers, usually paying them in grain. Minor cultivators were also willing to hire themselves out as labourers if the need arose.Sastri (1955), p. 297–298 It was due to the availability of these landless labourers that kings and landlords were able to execute major projects such as palaces, temples, mosques, anicuts (dams) and tanks.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 123 Because land was abundant and the population relatively sparse, no rent was charged on land ownership. Instead, landowners paid tax for cultivation, which amounted to up to one-half of all harvested produce.

Under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan is credited with founding state trading depots in various locations of his kingdom. In addition, he founded depots in foreign locations such asKarachi

Karachi is the capital city of the Administrative units of Pakistan, province of Sindh, Pakistan. It is the List of cities in Pakistan by population, largest city in Pakistan and 12th List of largest cities, largest in the world, with a popul ...

, Jeddah

Jeddah ( ), alternatively transliterated as Jedda, Jiddah or Jidda ( ; , ), is a List of governorates of Saudi Arabia, governorate and the largest city in Mecca Province, Saudi Arabia, and the country's second largest city after Riyadh, located ...

and Muscat

Muscat (, ) is the capital and most populous city in Oman. It is the seat of the Governorate of Muscat. According to the National Centre for Statistics and Information (NCSI), the population of the Muscat Governorate in 2022 was 1.72 million. ...

, where Mysore products were sold.M. H. Gopal in Kamath 2001, p. 235 During Tipu's rule French technology was used for the first time in carpentry and smithing

A metalsmith or simply smith is a craftsperson fashioning useful items (for example, tools, kitchenware, tableware, jewelry, armor and weapons) out of various metals. Smithing is one of the oldest metalworking occupations. Shaping metal with a ...

, Chinese technology was used for sugar production, and technology from Bengal

Bengal ( ) is a Historical geography, historical geographical, ethnolinguistic and cultural term referring to a region in the Eastern South Asia, eastern part of the Indian subcontinent at the apex of the Bay of Bengal. The region of Benga ...

helped improve the sericulture

Sericulture, or silk farming, is the cultivation of silkworms to produce silk. Although there are several commercial species of silkworms, the caterpillar of the Bombyx mori, domestic silkmoth is the most widely used and intensively studied silkwo ...

industry.Kamath (2001), pp. 235–236 State factories were established in Kanakapura

Kanakapura is a city in the Bengaluru South District of Karnataka on the banks of the Arkavathi river and the administrative center of the taluk of the same name. Its founder is Shrihan Kanaka Sigmanath, hence its name. Kanakapura is largest ...

and Taramandelpeth for producing cannons and gunpowder respectively. The state held the monopoly in the production of essentials such as sugar, salt, iron, pepper, cardamom, betel nut, tobacco and sandalwood

Sandalwood is a class of woods from trees in the genus ''Santalum''. The woods are heavy, yellow, and fine-grained, and, unlike many other aromatic woods, they retain their fragrance for decades. Sandalwood oil is extracted from the woods. Sanda ...

, as well as the extraction of incense oil from sandalwood and the mining of silver, gold and precious stones. Sandalwood was exported to China and the Persian Gulf countries and sericulture was developed in twenty-one centres within the kingdom.Kamath (2001), pp. 236–237

The Mysore silk industry was initiated during the rule of Tipu Sultan. Later the industry was hit by a global depression and competition from imported silk and rayon

Rayon, also called viscose and commercialised in some countries as sabra silk or cactus silk, is a semi-synthetic fiber made from natural sources of regenerated cellulose fiber, cellulose, such as wood and related agricultural products. It has t ...

. In the second half of the 20th century, it however revived and the Mysore State became the top multivoltine silk producer in India.

Under British rule

This system changed under the subsidiary alliance with the British, when tax payments were made in cash and were used for the maintenance of the army, police and other civil and public establishments. A portion of the tax was transferred to England as the "Indian tribute".Chopra et al. (2003), p. 124 Unhappy with the loss of their traditional revenue system and the problems they faced, peasants rose in rebellion in many parts of south India.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 129 After 1800, the Cornwallis land reforms came into effect. Reade, Munro, Graham and Thackeray were some administrators who improved the economic conditions of the masses.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 130 However, the homespun textile industry suffered while most of India was under British rule, except the producers of the finest cloth and the coarse cloth which was popular with the rural masses. This was due to the manufacturing mills ofManchester

Manchester () is a city and the metropolitan borough of Greater Manchester, England. It had an estimated population of in . Greater Manchester is the third-most populous metropolitan area in the United Kingdom, with a population of 2.92&nbs ...

, Liverpool

Liverpool is a port City status in the United Kingdom, city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. It is situated on the eastern side of the River Mersey, Mersey Estuary, near the Irish Sea, north-west of London. With a population ...

and Scotland being more than a match for the traditional handweaving industry, especially in spinning and weaving.Kamath (2001), p. 286Chopra et al. (2003), p. 132

The economic revolution in England and the tariff policies of the British also caused massive de-industrialization in other sectors throughout British India and Mysore. For example, the gunny bag weaving business had been a monopoly of the Goniga people, which they lost when the British began ruling the area. The import of a chemical substitute for saltpetre (potassium nitrate) affected the Uppar community, the traditional makers of saltpetre for use in gunpowder. The import of kerosene affected the Ganiga community which supplied oils. Foreign enamel and crockery industries affected the native pottery business, and mill-made blankets replaced the country-made blankets called ''kambli''.Kamath (2001), p. 287 This economic fallout led to the formation of community-based social welfare organisations to help those within the community to cope better with their new economic situation, including youth hostels for students seeking education and shelter.Kamath (2001), pp. 288–289 However, the British economic policies created a class structure consisting of a newly established middle class comprising various blue and white-collared occupational groups, including agents, brokers, lawyers, teachers, civil servants and physicians. Due to a more flexible caste hierarchy, the middle class contained a heterogeneous mix of people from different castes.Chopra et al. (2003), p. 134

Culture

Religion

The early kings of the Wodeyar dynasty worshipped the Hindu god Shiva. The later kings, starting from the 17th century, took toVaishnavism

Vaishnavism () ), also called Vishnuism, is one of the major Hindu denominations, Hindu traditions, that considers Vishnu as the sole Para Brahman, supreme being leading all other Hindu deities, that is, ''Mahavishnu''. It is one of the majo ...

, the worship of the Hindu god Vishnu.Rice E.P. (1921), p. 89 According to musicologist Meera Rajaram Pranesh, King Raja Wodeyar I was a devotee of the god Vishnu, King Dodda Devaraja was honoured with the title "Protector of Brahmins" (''Deva Brahmana Paripalaka'') for his support to Brahmin

Brahmin (; ) is a ''Varna (Hinduism), varna'' (theoretical social classes) within Hindu society. The other three varnas are the ''Kshatriya'' (rulers and warriors), ''Vaishya'' (traders, merchants, and farmers), and ''Shudra'' (labourers). Th ...

s, and Maharaja Krishnaraja III was devoted to the goddess Chamundeshwari (a form of Hindu goddess Durga

Durga (, ) is a major Hindu goddess, worshipped as a principal aspect of the mother goddess Mahadevi. She is associated with protection, strength, motherhood, destruction, and wars.

Durga's legend centres around combating evils and demonic ...

).Pranesh (2003), p. 5, p. 16, p. 54 Wilks ("History of Mysore", 1800) wrote about a ''Jangam

The ''Jangam'' (Kannada script, Kannada; ''ಜಂಗಮರು'') or Janga''muru or veerashaiva Jangam'' a Shaivism, Shaiva order of religious monks. They are the priests (Gurus) of the Shaivism, Hindu Shaiva sect, Gurus of Veerashaiva sect a ...

a'' (Veerashaiva

The Lingayats are a monotheistic religious denomination of Hinduism. Lingayats are also known as , , , . Lingayats are known for their unique practice of Ishtalinga worship, where adherents carry a personal linga symbolizing a constant, intim ...

saint-devotee of Shiva) uprising, related to excessive taxation, which was put down firmly by Chikka Devaraja. Historian D.R. Nagaraj claims that four hundred ''Jangamas'' were murdered in the process but clarifies that Veerashaiva literature itself is silent about the issue.Nagaraj in Pollock (2003), p. 379 Historian Suryanath Kamath claims King Chikka Devaraja was a Srivaishnava (follower of Sri Vaishnavism

Sri Vaishnavism () is a denomination within the Vaishnavism tradition of Hinduism, predominantly practiced in South India. The name refers to goddess Lakshmi (also known as Sri), as well as a prefix that means "sacred, revered", and the god Vi ...

, a sect of Vaishnavism) but was not anti-Veerashaiva.Kamath (2001), p. 229 Historian Aiyangar concurs that some of the kings including the celebrated Narasaraja I and Chikka Devaraja were Vaishnavas, but suggests this may not have been the case with all Wodeyar rulers.Aiyangar and Smith (1911), p. 304 The rise of the modern-day Mysore city as a centre of south Indian culture

South Indian culture refers to the cultural region typically covering the South Indian states of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, and Telangana. The idea of South India is closely linked to the Dravidian ethnic and linguistic ide ...

has been traced from the period of their sovereignty.Pranesh (2003), p. 17 Raja Wodeyar I initiated the celebration of the Dasara festival in Mysore, a proud tradition of the erstwhile Vijayanagara royal family.Aiyangar and Smith (1911), p. 290Pranesh (2003), p. 4

Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religions, Indian religion whose three main pillars are nonviolence (), asceticism (), and a rejection of all simplistic and one-sided views of truth and reality (). Jainism traces its s ...

, though in decline during the late medieval period, also enjoyed the patronage of the Mysore kings, who made munificent endowments to the Jain monastic order at the town of Shravanabelagola

Shravanabelagola (pronunciation: ) is a town located near Channarayapatna of Hassan district in the Indian state of Karnataka and is from Bengaluru. The Gommateshwara Bahubali statue at Shravanabelagola is one of the most important tirthas ...

.Pranesh (2003), p. 44Kamath (2001), pp. 229–230 Records indicate that some Wodeyar kings not only presided over the ''Mahamastakabhisheka

The ''Māhāmastakābhiṣeka'' ("Grand Consecration") refers to the ''abhiṣeka'' (anointment) of the Jain idols when held on a large scale. The most famous of such consecrations is the anointment of the Bahubali Gommateshwara statue loc ...

'' ceremony, an important Jain religious event at Shravanabelagola, but also personally offered prayers ('' puja'') during the years 1659, 1677, 1800, 1825, 1910, 1925, 1940, and 1953.Singh (2001), pp. 5782–5787

The contact between South India and Islam