Ibn Rushd on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Ibn Rushd (14 April 112611 December 1198), archaically Latinized as Averroes, was an

By 1153 Averroes was in

By 1153 Averroes was in

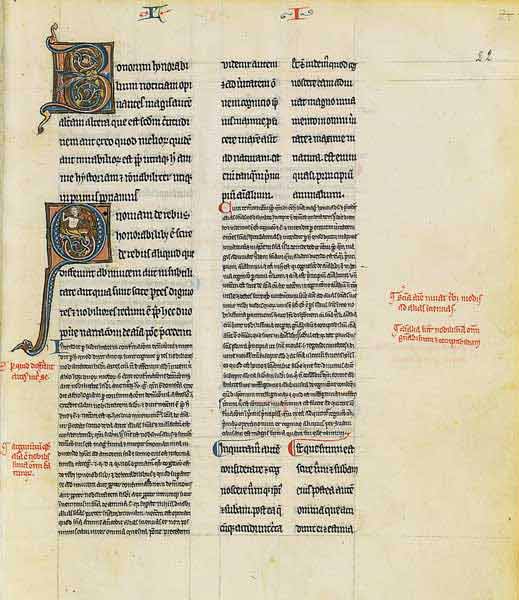

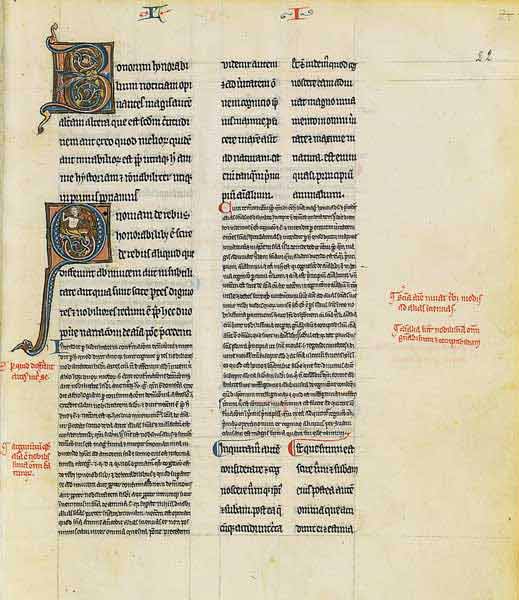

Averroes was a prolific writer and his works, according to Fakhry, "covered a greater variety of subjects" than those of any of his predecessors in the East, including philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence or legal theory, and linguistics. Most of his writings were commentaries on or paraphrasings of the works of Aristotle that—especially the long ones—often contain his original thoughts. According to French author Ernest Renan, Averroes wrote at least 67 original works, including 28 works on philosophy, 20 on medicine, 8 on law, 5 on theology, and 4 on grammar, in addition to his commentaries on most of Aristotle's works and his commentary on

Averroes was a prolific writer and his works, according to Fakhry, "covered a greater variety of subjects" than those of any of his predecessors in the East, including philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence or legal theory, and linguistics. Most of his writings were commentaries on or paraphrasings of the works of Aristotle that—especially the long ones—often contain his original thoughts. According to French author Ernest Renan, Averroes wrote at least 67 original works, including 28 works on philosophy, 20 on medicine, 8 on law, 5 on theology, and 4 on grammar, in addition to his commentaries on most of Aristotle's works and his commentary on

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's '' On the Soul''. Averroes is interested in explaining the human intellect using philosophical methods and by interpreting Aristotle's ideas. His position on the topic changed throughout his career as his thoughts developed. In his short commentary, the first of the three works, Averroes follows Ibn Bajja's theory that something called the " material intellect" stores specific images that a person encounters. These images serve as basis for the "unification" by the universal " agent intellect", which, once it happens, allow a person to gain universal knowledge about that concept. In his middle commentary, Averroes moves towards the ideas of Al-Farabi and Avicenna, saying the agent intellect gives humans the power of universal understanding, which is the material intellect. Once the person has sufficient empirical encounters with a certain concept, the power activates and gives the person universal knowledge (see also logical induction).

In his last commentary—called the ''Long Commentary''—he proposes another theory, which becomes known as the theory of "the unity of the intellect". In it, Averroes argues that there is only one material intellect, which is the same for all humans and is unmixed with human body. To explain how different individuals can have different thoughts, he uses a concept he calls ''fikr''—known as ''cogitatio'' in Latin—a process that happens in human brains and contains not universal knowledge but "active consideration of particular things" the person has encountered. This theory attracted controversy when Averroes's works entered Christian Europe; in 1229

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's '' On the Soul''. Averroes is interested in explaining the human intellect using philosophical methods and by interpreting Aristotle's ideas. His position on the topic changed throughout his career as his thoughts developed. In his short commentary, the first of the three works, Averroes follows Ibn Bajja's theory that something called the " material intellect" stores specific images that a person encounters. These images serve as basis for the "unification" by the universal " agent intellect", which, once it happens, allow a person to gain universal knowledge about that concept. In his middle commentary, Averroes moves towards the ideas of Al-Farabi and Avicenna, saying the agent intellect gives humans the power of universal understanding, which is the material intellect. Once the person has sufficient empirical encounters with a certain concept, the power activates and gives the person universal knowledge (see also logical induction).

In his last commentary—called the ''Long Commentary''—he proposes another theory, which becomes known as the theory of "the unity of the intellect". In it, Averroes argues that there is only one material intellect, which is the same for all humans and is unmixed with human body. To explain how different individuals can have different thoughts, he uses a concept he calls ''fikr''—known as ''cogitatio'' in Latin—a process that happens in human brains and contains not universal knowledge but "active consideration of particular things" the person has encountered. This theory attracted controversy when Averroes's works entered Christian Europe; in 1229

Averroes received a mixed reception from other Catholic thinkers;

Averroes received a mixed reception from other Catholic thinkers;

References to Averroes appear in the popular culture of both the western and Muslim world. The poem '' The Divine Comedy'' by the Italian writer Dante Alighieri, completed in 1320, depicts Averroes, "who made the Great Commentary", along with other non-Christian Greek and Muslim thinkers, in the first circle of hell around

References to Averroes appear in the popular culture of both the western and Muslim world. The poem '' The Divine Comedy'' by the Italian writer Dante Alighieri, completed in 1320, depicts Averroes, "who made the Great Commentary", along with other non-Christian Greek and Muslim thinkers, in the first circle of hell around

DARE

the Digital Averroes Research Environment, an ongoing effort to collect digital images of all Averroes manuscripts and full texts of all three language-traditions.

Islamic Philosophy Online (links to works by and about Averroes in several languages)

''The Philosophy and Theology of Averroes: Tractata translated from the Arabic''

trans. Mohammad Jamil-ur-Rehman, 1921

translation by Simon van den Bergh. [''N.B. '': Because these refutations consist mainly of commentary on statements by al-Ghazali which are quoted verbatim, this work contains a translation of most of the Tahafut.] There is also an Italian translation by Massimo Campanini, Averroè, ''L'incoerenza dell'incoerenza dei filosofi'', Turin, Utet, 1997.

SIEPM virtual library, including scanned copies (PDF) of the Editio Juntina of Averroes's works in Latin (Venice 1550–1562) *

Bibliography

a comprehensive overview of the extant bibliography

Averroes Database

including a full bibliography of his works

Podcast on Averroes

at NPR's '' Throughline'' {{Authority control 1126 births 1198 deaths 12th-century writers from al-Andalus 12th-century astronomers 12th-century Spanish philosophers 12th-century physicians Scholars from the Almohad Caliphate Arabic-language commentators on Aristotle Aristotelian philosophers Commentators on Plato Characters in the Divine Comedy Epistemologists Spanish ethicists Medieval Islamic philosophers Logicians Medieval Spanish astronomers Astronomers from al-Andalus Physicians from al-Andalus Medieval physicists Maliki scholars from al-Andalus 12th-century Muslim theologians Ontologists People from Córdoba, Spain Philosophers of culture Philosophers of history Philosophers of language Philosophers of literature Philosophers of logic Philosophers of mind Philosophers of psychology Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Political philosophers Spanish psychologists Social philosophers Sunni Muslim scholars of Islam World Digital Library exhibits Philosophers from al-Andalus Spanish Sunni Muslims Muslim critics of atheism Critics of deism Critics of Christianity

Arab

Arabs (, , ; , , ) are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in West Asia and North Africa. A significant Arab diaspora is present in various parts of the world.

Arabs have been in the Fertile Crescent for thousands of years ...

Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

polymath

A polymath or polyhistor is an individual whose knowledge spans many different subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific problems. Polymaths often prefer a specific context in which to explain their knowledge, ...

and jurist

A jurist is a person with expert knowledge of law; someone who analyzes and comments on law. This person is usually a specialist legal scholar, mostly (but not always) with a formal education in law (a law degree) and often a Lawyer, legal prac ...

from Al-Andalus

Al-Andalus () was the Muslim-ruled area of the Iberian Peninsula. The name refers to the different Muslim states that controlled these territories at various times between 711 and 1492. At its greatest geographical extent, it occupied most o ...

who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

, theology

Theology is the study of religious belief from a Religion, religious perspective, with a focus on the nature of divinity. It is taught as an Discipline (academia), academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itse ...

, medicine

Medicine is the science and Praxis (process), practice of caring for patients, managing the Medical diagnosis, diagnosis, prognosis, Preventive medicine, prevention, therapy, treatment, Palliative care, palliation of their injury or disease, ...

, astronomy

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and the phenomena that occur in the cosmos. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and their overall evolution. Objects of interest includ ...

, physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

, psychology

Psychology is the scientific study of mind and behavior. Its subject matter includes the behavior of humans and nonhumans, both consciousness, conscious and Unconscious mind, unconscious phenomena, and mental processes such as thoughts, feel ...

, mathematics

Mathematics is a field of study that discovers and organizes methods, Mathematical theory, theories and theorems that are developed and Mathematical proof, proved for the needs of empirical sciences and mathematics itself. There are many ar ...

, neurology

Neurology (from , "string, nerve" and the suffix wikt:-logia, -logia, "study of") is the branch of specialty (medicine) , medicine dealing with the diagnosis and treatment of all categories of conditions and disease involving the nervous syst ...

, Islamic jurisprudence and law, and linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of language. The areas of linguistic analysis are syntax (rules governing the structure of sentences), semantics (meaning), Morphology (linguistics), morphology (structure of words), phonetics (speech sounds ...

. The author of more than 100 books and treatises, his philosophical works include numerous commentaries on Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

, for which he was known in the Western world

The Western world, also known as the West, primarily refers to various nations and state (polity), states in Western Europe, Northern America, and Australasia; with some debate as to whether those in Eastern Europe and Latin America also const ...

as ''The Commentator'' and ''Father of Rationalism''.

Averroes was a strong proponent of Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by Prior Analytics, deductive logic and an Posterior Analytics, analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics ...

; he attempted to restore what he considered the original teachings of Aristotle and opposed the Neoplatonist tendencies of earlier Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

thinkers, such as al-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

and Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

. He also defended the pursuit of philosophy against criticism by Ash'ari theologians such as Al-Ghazali. Averroes argued that philosophy was permissible in Islam and even compulsory among certain elites. He also argued scriptural text should be interpreted allegorically if it appeared to contradict conclusions reached by reason and philosophy. In Islamic jurisprudence, he wrote the ''Bidāyat al-Mujtahid'' on the differences between Islamic schools of law and the principles that caused their differences. In medicine, he proposed a new theory of stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

, described the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a neurodegenerative disease primarily of the central nervous system, affecting both motor system, motor and non-motor systems. Symptoms typically develop gradually and non-motor issues become ...

for the first time, and might have been the first to identify the retina

The retina (; or retinas) is the innermost, photosensitivity, light-sensitive layer of tissue (biology), tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some Mollusca, molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focus (optics), focused two-dimensional ...

as the part of the eye responsible for sensing light. His medical book ''Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'', translated into Latin and known as the '' Colliget'', became a textbook in Europe for centuries.

His legacy in the Islamic world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

was modest for geographical and intellectual reasons. In the West, Averroes was known for his extensive commentaries on Aristotle, many of which were translated into Latin and Hebrew. The translations of his work reawakened western European interest in Aristotle and Greek thinkers, an area of study that had been widely abandoned after the fall of the Western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire, also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome, was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vast ...

. His thoughts generated controversies in Latin Christendom and triggered a philosophical movement called Averroism based on his writings. His unity of the intellect thesis, proposing that all humans share the same intellect, became one of the best-known and most controversial Averroist doctrines in the West. His works were condemned by the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the List of Christian denominations by number of members, largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics Catholic Church by country, worldwid ...

in 1270 and 1277. Although weakened by condemnations and sustained critique from Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, Latin Averroism continued to attract followers up to the sixteenth century.

Name

Ibn Rushd's full, transliterated Arabic name is "Abū l-Walīd Muḥammad ibn ʾAḥmad Ibn Rushd". Sometimes, the nickname ''al-Hafid'' ("The Grandson") is appended to his name, to distinguish him from his grandfather, a famous judge and jurist. "Averroes" is theMedieval Latin

Medieval Latin was the form of Literary Latin used in Roman Catholic Church, Roman Catholic Western Europe during the Middle Ages. It was also the administrative language in the former Western Roman Empire, Roman Provinces of Mauretania, Numidi ...

form of "Ibn Rushd"; it was derived from the Spanish pronunciation of the original Arabic name, wherein "Ibn" becomes "Aben" or "Aven". Other forms of the name in European languages include "Ibin-Ros-din", "Filius Rosadis", "Ibn-Rusid", "Ben-Raxid", "Ibn-Ruschod", "Den-Resched", "Aben-Rassad", "Aben-Rasd", "Aben-Rust", "Avenrosdy", "Avenryz", "Adveroys", "Benroist", "Avenroyth" and "Averroysta".

Biography

Early life and education

Little is known about Averroes's early life. Muhammad ibn Ahmad ibn Muhammad ibn Rushd was born on 14 April 1126 (520 AH) in Córdoba. His family was well known in the city for their public service, especially in the legal and religious fields. His grandfather Abu al-Walid Muhammad (d. 1126) was the chief judge ('' qadi'') of Córdoba and the imam of the Great Mosque of Córdoba under the Almoravids. His father Abu al-Qasim Ahmad was not as celebrated as his grandfather, but was also chief judge until the Almoravids were replaced by the Almohads in 1146. According to his traditional biographers, Averroes's education was "excellent", beginning with studies inhadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

(traditions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

), ''fiqh'' (jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, also known as theory of law or philosophy of law, is the examination in a general perspective of what law is and what it ought to be. It investigates issues such as the definition of law; legal validity; legal norms and values ...

), medicine and theology. He learned Maliki jurisprudence under al-Hafiz Abu Muhammad ibn Rizq and hadith with Ibn Bashkuwal, a student of his grandfather. His father also taught him about jurisprudence, including on Imam Malik's ''magnum opus'' the '' Muwatta'', which Averroes went on to memorize. He studied medicine under Abu Jafar Jarim al-Tajail, who probably taught him philosophy too. He also knew the works of the philosopher Ibn Bajjah (also known as Avempace), and might have known him personally or been tutored by him. He joined a regular meeting of philosophers, physicians and poets in Seville

Seville ( ; , ) is the capital and largest city of the Spain, Spanish autonomous communities of Spain, autonomous community of Andalusia and the province of Seville. It is situated on the lower reaches of the Guadalquivir, River Guadalquivir, ...

which was attended by philosophers Ibn Tufayl and Ibn Zuhr as well as the future caliph Abu Yusuf Yaqub. He also studied the '' kalam'' theology of the Ash'ari school, which he criticized later in life. His 13th-century biographer Ibn al-Abbar said he was more interested in the study of law and its principles (''usul'') than that of hadith and he was especially competent in the field of '' khilaf'' (disputes and controversies in the Islamic jurisprudence). Ibn al-Abbar also mentioned his interests in "the sciences of the ancients", probably in reference to Greek philosophy and sciences.

Career

By 1153 Averroes was in

By 1153 Averroes was in Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech (; , ) is the fourth-largest city in Morocco. It is one of the four imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh–Safi Regions of Morocco, region. The city lies west of the foothills of the Atlas Mounta ...

, the capital of the Almohad Caliphate (now in Morocco), to perform astronomical observations and to support the Almohad project of building new colleges. He was hoping to find physical laws of astronomical movements instead of only the mathematical laws known at the time but this research was unsuccessful. During his stay in Marrakesh, he likely met ibn Tufayl, a renowned philosopher and the author of '' Hayy ibn Yaqdhan'' who was also the court physician in Marrakesh. Averroes and ibn Tufayl became friends despite the differences in their philosophies.

In 1169, ibn Tufayl introduced Averroes to the Almohad caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf. In a famous account reported by historian 'Abd al-Wahid al-Marrakushi, the caliph asked Averroes whether the heavens had existed since eternity or had a beginning. Knowing this question was controversial and worried a wrong answer could put him in danger, Averroes did not answer. The caliph then elaborated the views of Plato, Aristotle and Muslim philosophers on the topic and discussed them with Ibn Tufayl. This display of knowledge put Averroes at ease; Averroes then explained his views on the subject, which impressed the caliph. Averroes was similarly impressed by Abu Yaqub and later said the caliph had "a profuseness of learning I did not suspect".

After their introduction, Averroes remained in Abu Yaqub's favor until the caliph died in 1184. When the caliph complained to Ibn Tufayl about the difficulty of understanding Aristotle's work, Ibn Tufayl recommended to the caliph that Averroes work on explaining it. This was the beginning of Averroes's massive commentaries on Aristotle; his first works on the subject were written in 1169.

In the same year, Averroes was appointed ''qadi'' (judge) in Seville. In 1171 he became ''qadi'' in his hometown of Córdoba. As ''qadi'' he would decide cases and give '' fatwa''s (legal opinions) based on religious law

Religious law includes ethical and moral codes taught by religious traditions. Examples of religiously derived legal codes include Christian canon law (applicable within a wider theological conception in the church, but in modern times distin ...

. The writing rate increased during this time despite other obligations and his travels within the Almohad empire. He also took the opportunity from his travels to conduct astronomical research. Many of his works produced between 1169 and 1179 were dated in Seville rather than Córdoba. In 1179 he was again appointed ''qadi'' in Seville. In 1182, he succeeded his friend Ibn Tufayl as court physician. Later the same year, he was appointed chief qadi of Córdoba, then controlled by the Taifa of Seville, a prestigious office that his grandfather had once held.

In 1184 Caliph Abu Yaqub died and was succeeded by Abu Yusuf Yaqub. Initially, Averroes remained in royal favour, but in 1195, his fortune reversed. Various charges were made against him, and a tribunal in Córdoba tried him. The tribunal condemned his teachings, ordered the burning of his works and banished Averroes to nearby Lucena. Early biographers' reasons for this fall from grace include a possible insult to the caliph in his writings but modern scholars attribute it to political reasons. The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is a reference work that facilitates the Islamic studies, academic study of Islam. It is published by Brill Publishers, Brill and provides information on various aspects of Islam and the Muslim world, Isl ...

'' said the caliph distanced himself from Averroes to gain support from more orthodox ''ulema'', who opposed Averroes and whose support al-Mansur needed for his war against Christian kingdoms. Historian of Islamic philosophy Majid Fakhry also wrote that public pressure from traditional Maliki jurists who were opposed to Averroes played a role.

After a few years, Averroes returned to court in Marrakesh and was again in the caliph's favor. He died shortly afterwards, on 11 December 1198 (9 Safar 595 in the Islamic calendar). He was initially buried in North Africa

North Africa (sometimes Northern Africa) is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region. However, it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of t ...

. His body was later moved to Córdoba for another funeral, at which future Sufi mystic and philosopher ibn Arabi (1165–1240) was present.

Works

Plato

Plato ( ; Greek language, Greek: , ; born BC, died 348/347 BC) was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical Greece, Classical period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy and an innovator of the writte ...

's '' The Republic''. Many of Averroes's works in Arabic did not survive, but their translations into Hebrew

Hebrew (; ''ʿÎbrit'') is a Northwest Semitic languages, Northwest Semitic language within the Afroasiatic languages, Afroasiatic language family. A regional dialect of the Canaanite languages, it was natively spoken by the Israelites and ...

or Latin did. For example, of his long commentaries on Aristotle, only "a tiny handful of Arabic manuscript remains".

Commentaries on Aristotle

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''

Averroes wrote commentaries on nearly all of Aristotle's surviving works. The only exception is ''Politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

'', which he did not have access to, so he wrote commentaries on Plato's ''Republic''. He classified his commentaries into three categories that modern scholars have named ''short'', ''middle'' and ''long'' commentaries. Most of the short commentaries (''jami'') were written early in his career and contain summaries of Aristotlean doctrines. The middle commentaries (''talkhis'') contain paraphrases that clarify and simplify Aristotle's original text. The middle commentaries were probably written in response to his patron caliph Abu Yaqub Yusuf's complaints about the difficulty of understanding Aristotle's original texts and to help others in a similar position. The long commentaries (''tafsir'' or ''sharh''), or line-by-line commentaries, include the complete text of the original works with a detailed analysis of each line. The long commentaries are very detailed and contain a high degree of original thought, and were unlikely to be intended for a general audience. Only five of Aristotle's works had all three types of commentaries: ''Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

'', ''Metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of reality. It is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent features of the world, but some theorists view it as an inquiry into the conceptual framework of ...

'', '' On the Soul'', '' On the Heavens'', and '' Posterior Analytics''.

Stand-alone philosophical works

Averroes also wrote stand-alone philosophical treatises, including ''On the Intellect'', ''On the Syllogism'', ''On Conjunction with the Active Intellect'', ''On Time'', ''On the Heavenly Sphere'' and ''On the Motion of the Sphere''. He also wrote several polemics: ''Essay onal-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

's Approach to Logic, as Compared to that of Aristotle'', ''Metaphysical Questions Dealt with in the Book of Healing by Ibn Sina'', and ''Rebuttal of Ibn Sina's Classification of Existing Entities''.

Islamic theology

Scholarly sources, including Fakhry and the ''Encyclopaedia of Islam

The ''Encyclopaedia of Islam'' (''EI'') is a reference work that facilitates the Islamic studies, academic study of Islam. It is published by Brill Publishers, Brill and provides information on various aspects of Islam and the Muslim world, Isl ...

'', have named three works Averroes's critical writings in this area. '' Fasl al-Maqal'' ("The Decisive Treatise") is an 1178 treatise that argues for the compatibility of Islam and philosophy. ''Al-Kashf 'an Manahij al-Adillah'' ("Exposition of the Methods of Proof"), written in 1179, criticizes the theologies of the Ash'arites, and lays out Averroes's argument for proving the existence of God, as well as his thoughts on God's attributes and actions. The 1180 '' Tahafut at-Tahafut'' ("Incoherence of the Incoherence") is a rebuttal of al-Ghazali's (d. 1111) landmark criticism of philosophy '' The Incoherence of the Philosophers''. It combines ideas in his commentaries and stand-alone works and uses them to respond to al-Ghazali. The work also criticizes Avicenna and his neoplatonist tendencies, sometimes agreeing with al-Ghazali's critique against him.

Medicine

Averroes, who served as the royal physician at the Almohad court, wrote a number of medical treatises. The most famous was ''al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The General Principles of Medicine", Latinized in the west as the ''Colliget''), written around 1162, before his appointment at court. The title of this book is the opposite of ''al-Juz'iyyat fi al-Tibb'' ("The Specificities of Medicine"), written by his friend Ibn Zuhr, and the two collaborated intending that their works complement each other. The Latin translation of the ''Colliget'' became a medical textbook in Europe for centuries. His other surviving titles include ''On Treacle'', ''The Differences in Temperament'', and ''Medicinal Herbs''. He also wrote summaries of the works of Greek physicianGalen

Aelius Galenus or Claudius Galenus (; September 129 – AD), often Anglicization, anglicized as Galen () or Galen of Pergamon, was a Ancient Rome, Roman and Greeks, Greek physician, surgeon, and Philosophy, philosopher. Considered to be one o ...

(died 210) and a commentary on Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

's ''Urjuzah fi al-Tibb'' ("Poem on Medicine").

Averroes made pioneering observations. He identified the retina, rather than the lens, as the primary organ responsible for sensing light, a significant departure from prevailing theories of his time. Averroes provided early descriptions of conditions resembling Parkinson's disease and offered insights into stroke, attributing it to cerebral causes rather than peripheral obstructions.

Jurisprudence and law

Averroes served multiple tenures as judge and produced multiple works in the fields of Islamic jurisprudence or legal theory. The only book that survives today is ''Bidāyat al-Mujtahid wa Nihāyat al-Muqtaṣid'' ("Primer of the Discretionary Scholar"). In this work he explains the differences of opinion ('' ikhtilaf'') between the Sunni ''madhhab

A ''madhhab'' (, , pl. , ) refers to any school of thought within fiqh, Islamic jurisprudence. The major Sunni Islam, Sunni ''madhhab'' are Hanafi school, Hanafi, Maliki school, Maliki, Shafi'i school, Shafi'i and Hanbali school, Hanbali.

They ...

s'' (schools of Islamic jurisprudence) both in practice and in their underlying juristic principles, as well as the reason why they are inevitable. Despite his status as a Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

judge, the book also discusses the opinion of other schools, including liberal and conservative ones. Other than this surviving text, bibliographical information shows he wrote a summary of Al-Ghazali's '' On Legal Theory of Muslim Jurisprudence'' (''Al-Mustasfa'') and tracts on sacrifices and land tax.

Philosophical ideas

Aristotelianism in the Islamic philosophical tradition

In his philosophical writings, Averroes attempted to return toAristotelianism

Aristotelianism ( ) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by Prior Analytics, deductive logic and an Posterior Analytics, analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics ...

, which according to him had been distorted by the Neoplatonist tendencies of Muslim philosophers such as Al-Farabi

file:A21-133 grande.webp, thumbnail, 200px, Postage stamp of the USSR, issued on the 1100th anniversary of the birth of Al-Farabi (1975)

Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (; – 14 December 950–12 January 951), known in the Greek East and Latin West ...

and Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

. He rejected al-Farabi's attempt to merge the ideas of Plato and Aristotle, pointing out the differences between the two, such as Aristotle's rejection of Plato's theory of ideas. He also criticized Al-Farabi's works on logic for misinterpreting its Aristotelian source. He wrote an extensive critique of Avicenna, who was the standard-bearer of Islamic Neoplatonism in the Middle Ages. He argued that Avicenna's theory of emanation had many fallacies and was not found in the works of Aristotle. Averroes disagreed with Avicenna's view that existence is merely an accident

An accident is an unintended, normally unwanted event that was not deliberately caused by humans. The term ''accident'' implies that the event may have been caused by Risk assessment, unrecognized or unaddressed risks. Many researchers, insurers ...

added to essence, arguing the reverse; something exists ''per se'' and essence can only be found by subsequent abstraction. He also rejected Avicenna's modality and Avicenna's argument to prove the existence of God as the Necessary Existent.

Averroes felt strongly about the incorporation of Greek thought into the Muslim world

The terms Islamic world and Muslim world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs, politics, and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is ...

, and wrote that "if before us someone has inquired into isdom it behooves us to seek help from what he has said. It is irrelevant whether he belongs to our community or to another".

Relation between religion and philosophy

During Averroes's lifetime, philosophy came under attack from the Sunni tradition, especially from theological schools like the Hanbali school and the Ashʾarites. In particular, the Ashʾari scholar al-Ghazali (1058–1111) wrote ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'', a scathing and influential critique of the Neoplatonic philosophical tradition in the Islamic world and against the works of Avicenna in particular. Among others, Al-Ghazali charged philosophers with non-belief in Islam and sought to disprove the teaching of the philosophers using logical arguments. In ''Decisive Treatise'', Averroes argues that philosophy—which for him represented conclusions reached using reason and careful method—cannot contradict revelations in Islam because they are just two different methods of reaching the truth, and "truth cannot contradict truth". When conclusions reached by philosophy appear to contradict the text of the revelation, then according to Averroes, revelation must be subjected to interpretation or allegorical understanding to remove the contradiction. This interpretation must be done by those "rooted in knowledge"—a phrase taken from surah Āl Imrān 3:7 of theQuran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

, which for Averroes refers to philosophers who during his lifetime had access to the "highest methods of knowledge". He also argues that the Quran calls for Muslims to study philosophy because the study and reflection of nature would increase a person's knowledge of "the Artisan" (God). He quotes Quranic passages calling Muslims to reflect on nature. He uses them to render a fatwa that philosophy is allowed for Muslims and is probably an obligation, at least among those who have the talent for it.

Averroes also distinguishes between three modes of discourse: the rhetoric

Rhetoric is the art of persuasion. It is one of the three ancient arts of discourse ( trivium) along with grammar and logic/ dialectic. As an academic discipline within the humanities, rhetoric aims to study the techniques that speakers or w ...

al (based on persuasion) accessible to the common masses; the dialectical (based on debate) and often employed by theologians and the ulama

In Islam, the ''ulama'' ( ; also spelled ''ulema''; ; singular ; feminine singular , plural ) are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

"Ulama ...

(religious scholars); and the demonstrative (based on logical deduction). According to Averroes, the Quran uses the rhetorical method of inviting people to the truth, which allows it to reach the common masses with its persuasiveness, whereas philosophy uses the demonstrative methods that were only available to the learned but provided the best possible understanding and knowledge.

Averroes also tries to deflect Al-Ghazali's criticisms of philosophy by saying that many of them apply only to the philosophy of Avicenna and not to that of Aristotle, which Averroes argues to be the true philosophy from which Avicenna has deviated.

Nature of God

Existence

Averroes lays out his views on the existence and nature of God in the treatise ''The Exposition of the Methods of Proof''. He examines and critiques the doctrines of four sects of Islam: the Asharites, the Mutazilites, the Sufis and those he calls the "literalists" (''al-hashwiyah''). Among other things, he examines their proofs of God's existence and critiques each one. Averroes argues that there are two arguments for God's existence that he deems logically sound and in accordance to the Quran; the arguments from "providence" and "from invention". The providence argument considers that the world and the universe seem finely tuned to support human life. Averroes cited the sun, the moon, the rivers, the seas and the location of humans on the earth. According to him, this suggests a creator who created them for the welfare of mankind. The argument from invention contends that worldly entities such as animals and plants appear to have been invented. Therefore, Averroes argues that a designer was behind the creation and that is God. Averroes's two arguments areteleological

Teleology (from , and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology. In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Applet ...

in nature and not cosmological

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe, the cosmos. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', with the meaning of "a speaking of the wo ...

like the arguments of Aristotle

Aristotle (; 384–322 BC) was an Ancient Greek philosophy, Ancient Greek philosopher and polymath. His writings cover a broad range of subjects spanning the natural sciences, philosophy, linguistics, economics, politics, psychology, a ...

and most contemporaneous Muslim kalam theologians.

God's attributes

Averroes upholds the doctrine of divine unity (''tawhid

''Tawhid'' () is the concept of monotheism in Islam, it is the religion's central and single most important concept upon which a Muslim's entire religious adherence rests. It unequivocally holds that God is indivisibly one (''ahad'') and s ...

'') and argues that God has seven divine attributes: knowledge, life, power, will, hearing, vision and speech. He devotes the most attention to the attribute of knowledge and argues that divine knowledge differs from human knowledge because God knows the universe because God is its cause while humans only know the universe through its effects.

Averroes argues that the attribute of life can be inferred because it is the precondition of knowledge and also because God willed objects into being. Power can be inferred by God's ability to bring creations into existence. Averroes also argues that knowledge and power inevitably give rise to speech. Regarding vision and speech, he says that because God created the world, he necessarily knows every part of it in the same way an artist understands his or her work intimately. Because two elements of the world are the visual and the auditory, God must necessarily possess vision and speech.

The omnipotence paradox was first addressed by AverroesAverroës, ''Tahafut al-Tahafut (The Incoherence of the Incoherence)'' trans. Simon Van Den Bergh, Luzac & Company 1969, sections 529–536 and only later by Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

. Aquinas, Thomas Summa Theologica

The ''Summa Theologiae'' or ''Summa Theologica'' (), often referred to simply as the ''Summa'', is the best-known work of Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), a scholastic theologian and Doctor of the Church. It is a compendium of all of the main t ...

Book 1 Question 25 article 3

Pre-eternity of the world

In the centuries preceding Averroes, there had been a debate between Muslim thinkers questioning whether the world was created at a specific moment in time or whether it has always existed. Neo-Platonic philosophers such as Al-Farabi and Avicenna argued the world has always existed. This view was criticized by the mutakallimin (philosophers and theologians) of the Ashʾari tradition; in particular, al-Ghazali wrote an extensive refutation of the pre-eternity doctrine in his ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' and accused the Neoplatonists of unbelief ('' kufr''). Averroes responded to Al-Ghazali in his ''Incoherence of the Incoherence''. He argued first that the differences between the two positions were not vast enough to warrant the charge of unbelief. He also said the pre-eternity doctrine did not necessarily contradict the Quran and cited verses that mention pre-existing "throne" and "water" in passages related to creation. Averroes argued that a careful reading of the Quran implied only the "form" of the universe was created in time but that its existence has been eternal. Averroes further criticized the mutakallimin for using their interpretations of scripture to answer questions that should have been left to philosophers.Politics

Averroes states his political philosophy in his commentary of Plato's ''Republic''. He combines his ideas with Plato's and with Islamic tradition; he considers the ideal state to be one based on the Islamic law ('' shariah''). His interpretation of Plato's philosopher-king followed that of Al-Farabi, which equates the philosopher-king with theimam

Imam (; , '; : , ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Islam, Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a prayer leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Salah, Islamic prayers, serve as community leaders, ...

, caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

and lawgiver of the state. Averroes's description of the characteristics of a philosopher-king are similar to those given by Al-Farabi; they include love of knowledge, good memory, love of learning, love of truth, dislike for sensual pleasures, dislike for amassing wealth, magnanimity, courage, steadfastness, eloquence and the ability to "light quickly on the middle term". Averroes writes that if philosophers cannot rule—as was the case in the Almoravid and Almohad empires around his lifetime—philosophers must still try to influence the rulers towards implementing the ideal state.

According to Averroes, there are two methods of teaching virtue to citizens; persuasion and coercion. Persuasion is the more natural method consisting of rhetorical, dialectical and demonstrative methods; sometimes, however, coercion is necessary for those not amenable to persuasion, e.g. enemies of the state. Therefore, he justifies war as a last resort, which he also supports using Quranic arguments. Consequently, he argues that a ruler should have both wisdom and courage, which are needed for governance and defense of the state.

Like Plato, Averroes calls for women to share with men in the administration of the state, including participating as soldiers, philosophers and rulers. He regrets that contemporaneous Muslim societies limited the public role of women; he says this limitation is harmful to the state's well-being.

Averroes also accepted Plato's ideas of the deterioration of the ideal state. He cites examples from Islamic history when the Rashidun caliphate

The Rashidun Caliphate () is a title given for the reigns of first caliphs (lit. "successors") — Abu Bakr, Umar, Uthman, and Ali collectively — believed to Political aspects of Islam, represent the perfect Islam and governance who led the ...

—which in Sunni tradition represented the ideal state led by "rightly guided caliphs"—became a dynastic state under Muawiyah, founder of the Umayyad dynasty. He also says the Almoravid and the Almohad empires started as ideal, shariah-based states but then deteriorated into timocracy, oligarchy

Oligarchy (; ) is a form of government in which power rests with a small number of people. Members of this group, called oligarchs, generally hold usually hard, but sometimes soft power through nobility, fame, wealth, or education; or t ...

, democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

and tyranny.

Diversity of Islamic law

In his tenure as judge and jurist, Averroes for the most part ruled and gave fatwas according to the Maliki school of Islamic law which was dominant in Al-Andalus and the western Islamic world during his time. However, he frequently acted as "his own man", including sometimes rejecting the "consensus of the people ofMedina

Medina, officially al-Madinah al-Munawwarah (, ), also known as Taybah () and known in pre-Islamic times as Yathrib (), is the capital of Medina Province (Saudi Arabia), Medina Province in the Hejaz region of western Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, ...

" argument that is one of the traditional Maliki position. In ''Bidāyat al-Mujtahid'', one of his major contributions to the field of Islamic law, he not only describes the differences between various school of Islamic laws but also tries to theoretically explain the reasons for the difference and why they are inevitable. Even though all the schools of Islamic law are ultimately rooted in the Quran and hadith, there are "causes that necessitate differences" (''al-asbab al-lati awjabat al-ikhtilaf''). They include differences in interpreting scripture in a general or specific sense, in interpreting scriptural commands as obligatory or merely recommended, or prohibitions as discouragement or total prohibition, as well as ambiguities in the meaning of words or expressions. Averroes also writes that the application of ''qiyas

Qiyas (, , ) is the process of deductive analogy in which the teachings of the hadith are compared and contrasted with those of the Quran in Islamic jurisprudence, in order to apply a known injunction ('' nass'') to a new circumstance and cre ...

'' (reasoning by analogy) could give rise to different legal opinion because jurists might disagree on the applicability of certain analogies and different analogies might contradict each other.

Natural philosophy

Astronomy

As did Avempace and Ibn Tufail, Averroes criticizes the Ptolemaic system using philosophical arguments and rejects the use of eccentrics and epicycles to explain the apparent motions of the Moon, the Sun and the planets. He argued that those objects move uniformly in a strictly circular motion around the Earth, following Aristotelian principles. He postulates that there are three type of planetary motions; those that can be seen with the naked eye, those that require instruments to observe and those that can only be known by philosophical reasoning. Averroes argues that the occasional opaque colors of the Moon are caused by variations in its thickness; the thicker parts receive more light from the Sun—and therefore emit more light—than the thinner parts. This explanation was used up to the seventeenth century by the European Scholastics to account forGalileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642), commonly referred to as Galileo Galilei ( , , ) or mononymously as Galileo, was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a poly ...

's observations of spots on the Moon's surface, until the Scholastics such as Antoine Goudin in 1668 conceded that the observation was more likely caused by mountains on the Moon. He and Ibn Bajja observed sunspot

Sunspots are temporary spots on the Sun's surface that are darker than the surrounding area. They are one of the most recognizable Solar phenomena and despite the fact that they are mostly visible in the solar photosphere they usually aff ...

s, which they thought were transits of Venus and Mercury between the Sun and the Earth. In 1153 he conducted astronomical observations in Marrakesh, where he observed the star Canopus (Arabic: ''Suhayl'') which was invisible in the latitude of his native Spain. He used this observation to support Aristotle's argument for the spherical Earth

Spherical Earth or Earth's curvature refers to the approximation of the figure of the Earth as a sphere. The earliest documented mention of the concept dates from around the 5th century BC, when it appears in the writings of Ancient Greek philos ...

.

Averroes was aware that Arabic and Andalusian astronomers of his time focused on "mathematical" astronomy, which enabled accurate predictions through calculations but did not provide a detailed physical explanation of how the universe worked. According to him, "the astronomy of our time offers no truth, but only agrees with the calculations and not with what exists." He attempted to reform astronomy to be reconciled with physics, especially the physics of Aristotle. His long commentary of Aristotle's ''Metaphysics'' describes the principles of his attempted reform, but later in his life he declared that his attempts had failed. He confessed that he had not enough time or knowledge to reconcile the observed planetary motions with Aristotelian principles. In addition, he did not know the works of Eudoxus and Callippus, and so he missed the context of some of Aristotle's astronomical works. However, his works influenced astronomer Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji (d. 1204) who adopted most of his reform principles and did succeed in proposing an early astronomical system based on Aristotelian physics.

Physics

In physics, Averroes did not adopt the inductive method that was being developed by Al-Biruni in the Islamic world and is closer to today's physics. Rather, he was—in the words of historian of science Ruth Glasner—an "exegetical" scientist who produced new theses about nature through discussions of previous texts, especially the writings of Aristotle. because of this approach, he was often depicted as an unimaginative follower of Aristotle, but Glasner argues that Averroes's work introduced highly original theories of physics, especially his elaboration of Aristotle's '' minima naturalia'' and on motion as ''forma fluens'', which were taken up in the west and are important to the overall development of physics.Psychology

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's '' On the Soul''. Averroes is interested in explaining the human intellect using philosophical methods and by interpreting Aristotle's ideas. His position on the topic changed throughout his career as his thoughts developed. In his short commentary, the first of the three works, Averroes follows Ibn Bajja's theory that something called the " material intellect" stores specific images that a person encounters. These images serve as basis for the "unification" by the universal " agent intellect", which, once it happens, allow a person to gain universal knowledge about that concept. In his middle commentary, Averroes moves towards the ideas of Al-Farabi and Avicenna, saying the agent intellect gives humans the power of universal understanding, which is the material intellect. Once the person has sufficient empirical encounters with a certain concept, the power activates and gives the person universal knowledge (see also logical induction).

In his last commentary—called the ''Long Commentary''—he proposes another theory, which becomes known as the theory of "the unity of the intellect". In it, Averroes argues that there is only one material intellect, which is the same for all humans and is unmixed with human body. To explain how different individuals can have different thoughts, he uses a concept he calls ''fikr''—known as ''cogitatio'' in Latin—a process that happens in human brains and contains not universal knowledge but "active consideration of particular things" the person has encountered. This theory attracted controversy when Averroes's works entered Christian Europe; in 1229

Averroes expounds his thoughts on psychology in his three commentaries on Aristotle's '' On the Soul''. Averroes is interested in explaining the human intellect using philosophical methods and by interpreting Aristotle's ideas. His position on the topic changed throughout his career as his thoughts developed. In his short commentary, the first of the three works, Averroes follows Ibn Bajja's theory that something called the " material intellect" stores specific images that a person encounters. These images serve as basis for the "unification" by the universal " agent intellect", which, once it happens, allow a person to gain universal knowledge about that concept. In his middle commentary, Averroes moves towards the ideas of Al-Farabi and Avicenna, saying the agent intellect gives humans the power of universal understanding, which is the material intellect. Once the person has sufficient empirical encounters with a certain concept, the power activates and gives the person universal knowledge (see also logical induction).

In his last commentary—called the ''Long Commentary''—he proposes another theory, which becomes known as the theory of "the unity of the intellect". In it, Averroes argues that there is only one material intellect, which is the same for all humans and is unmixed with human body. To explain how different individuals can have different thoughts, he uses a concept he calls ''fikr''—known as ''cogitatio'' in Latin—a process that happens in human brains and contains not universal knowledge but "active consideration of particular things" the person has encountered. This theory attracted controversy when Averroes's works entered Christian Europe; in 1229 Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

wrote a detailed critique titled ''On the Unity of the Intellect against the Averroists''.

Medicine

While his works in medicine indicate an in-depth theoretical knowledge in medicine of his time, he likely had limited expertise as a practitioner, and declared in one of his works that he had not "practiced much apart from myself, my relatives or my friends." He did serve as a royal physician, but his qualification and education was mostly theoretical. For the most part, Averroes's medical work ''Al-Kulliyat fi al-Tibb'' follows the medical doctrine of Galen, an influential Greek physician and author from the second century, which was based on the four humors—blood, yellow bile, black bile, and phlegm, whose balance is necessary for the health of the human body. Averroes's original contributions include his observations on the retina: he might have been the first to recognize that theretina

The retina (; or retinas) is the innermost, photosensitivity, light-sensitive layer of tissue (biology), tissue of the eye of most vertebrates and some Mollusca, molluscs. The optics of the eye create a focus (optics), focused two-dimensional ...

was the part of the eye responsible for sensing light, rather than the lens

A lens is a transmissive optical device that focuses or disperses a light beam by means of refraction. A simple lens consists of a single piece of transparent material, while a compound lens consists of several simple lenses (''elements'') ...

as was commonly thought. Modern scholars dispute whether this is what he meant it his ''Kulliyat'', but Averroes also stated a similar observation in his commentary to Aristotle's '' Sense and Sensibilia'': "the innermost of the coats of the eye he retinamust necessarily receive the light from the humors of the eye he lens just like the humors receive the light from air."

Another of his departures from Galen and the medical theories of the time is his description of stroke

Stroke is a medical condition in which poor cerebral circulation, blood flow to a part of the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: brain ischemia, ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and intracranial hemorrhage, hemor ...

as produced by the brain and caused by an obstruction of the arteries from the heart to the brain. This explanation is closer to the modern understanding of the disease compared to that of Galen, which attributes it to the obstruction between heart and the periphery. He was also the first to describe the signs and symptoms of Parkinson's disease

Parkinson's disease (PD), or simply Parkinson's, is a neurodegenerative disease primarily of the central nervous system, affecting both motor system, motor and non-motor systems. Symptoms typically develop gradually and non-motor issues become ...

in his ''Kulliyat'', although he did not give the disease a name.

Legacy

In Jewish tradition

Maimonides

Moses ben Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (, ) and also referred to by the Hebrew acronym Rambam (), was a Sephardic rabbi and Jewish philosophy, philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah schola ...

(d. 1204) was among early Jewish scholars who received Averroes's works enthusiastically, saying he "received lately everything Averroes had written on the works of Aristotle" and that Averroes "was extremely right". Thirteenth-century Jewish writers, including Samuel ibn Tibbon

Samuel ben Judah ibn Tibbon ( – ), more commonly known as Samuel ibn Tibbon (, ), was a Jewish philosopher and doctor who lived and worked in Provence, later part of France. He was born about 1150 in Lunel, Hérault, Lunel (Languedoc), and die ...

in his work ''Opinion of the Philosophers'', Judah ben Solomon ha-Kohen in his ''Search for Wisdom'' and Shem-Tov ibn Falaquera, relied heavily on Averroes's texts. In 1232, Joseph Ibn Kaspi translated Averroes's commentaries on Aristotle's '' Organon''; this was the first Jewish translation of a complete work. In 1260 Moses ibn Tibbon published the translation of almost all of Averroes's commentaries and some of his medical works. Jewish Averroism peaked in the fourteenth century; Jewish writers of this time who translated or were influenced by Averroes include Kalonymus ben Kalonymus of Arles

Arles ( , , ; ; Classical ) is a coastal city and Communes of France, commune in the South of France, a Subprefectures in France, subprefecture in the Bouches-du-Rhône Departments of France, department of the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur Reg ...

, France, Todros Todrosi of Arles, Elia del Medigo of Candia and Gersonides of Languedoc

The Province of Languedoc (, , ; ) is a former province of France.

Most of its territory is now contained in the modern-day region of Occitanie in Southern France. Its capital city was Toulouse. It had an area of approximately .

History

...

.

Averroes was cited by Falaquera, Yehuda Moscato and Abraham Bibago to argue that the Greeks borrowed their scientific and philosophical knowledge from Jewish sources.

In Latin tradition

Averroes's main influence on the Christian West was through his extensive commentaries on Aristotle. After the fall of theWestern Roman Empire

In modern historiography, the Western Roman Empire was the western provinces of the Roman Empire, collectively, during any period in which they were administered separately from the eastern provinces by a separate, independent imperial court. ...

, western Europe fell into a cultural decline that resulted in the loss of nearly all of the intellectual legacy of the Classical Greek scholars, including Aristotle. Averroes's commentaries, which were translated into Latin and entered western Europe in the thirteenth century, provided an expert account of Aristotle's legacy and made them available again. The influence of his commentaries led to Averroes being referred to simply as "The Commentator" rather than by name in Latin Christian writings. He has been sometimes described as the "father of free thought and unbelief" and "father of rationalism".

Michael Scot (1175 – 1232) was the first Latin translator of Averroes who translated the long commentaries of ''Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its Elementary particle, fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge whi ...

'', ''Metaphysics'', ''On the Soul'' and ''On the Heavens'', as well as multiple middle and short commentaries, starting in 1217 in Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

and Toledo. Following this, European authors such as Hermannus Alemannus, William de Luna and Armengaud of Montpellier translated Averroes's other works, sometimes with help from Jewish authors. Soon after, Averroes's works propagated among Christian scholars in the scholastic tradition. His writing attracted a strong circle of followers known as the Latin Averroists. Paris and Padua

Padua ( ) is a city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Veneto, northern Italy, and the capital of the province of Padua. The city lies on the banks of the river Bacchiglione, west of Venice and southeast of Vicenza, and has a population of 20 ...

were major centers of Latin Averroism, and its prominent thirteenth-century leaders included Siger of Brabant and Boethius of Dacia.

Authorities of the Roman Catholic Church reacted against the spread of Averroism. In 1270, the Bishop of Paris

The Archdiocese of Paris (; ) is a Latin Church ecclesiastical jurisdiction or archdiocese of the Catholic Church in France. It is one of twenty-three archdioceses in France. The original diocese is traditionally thought to have been create ...

Étienne Tempier

Étienne Tempier (; also known as Stephanus of Orleans; died 3 September 1279) was a French bishop of Paris during the 13th century. He was Chancellor of the University of Paris, Chancellor of the University of Paris, Sorbonne from 1263 to 1268, ...

issued a condemnation against 15 doctrines—many of which were Aristotelian or Averroist—that he said were in conflict with the doctrines of the church. In 1277, at the request of Pope John XXI

Pope John XXI (, , ; – 20 May 1277), born Pedro Julião (), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 8 September 1276 to his death in May 1277. He is the only ethnically Portuguese pope in history.Richard P. McBrien, ...

, Tempier issued another condemnation, this time targeting 219 theses drawn from many sources, mainly the teachings of Aristotle and Averroes.

Averroes received a mixed reception from other Catholic thinkers;

Averroes received a mixed reception from other Catholic thinkers; Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas ( ; ; – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican Order, Dominican friar and Catholic priest, priest, the foremost Scholasticism, Scholastic thinker, as well as one of the most influential philosophers and theologians in the W ...

, a leading Catholic thinker of the thirteenth century, relied extensively on Averroes's interpretation of Aristotle but disagreed with him on many points. For example, he wrote a detailed attack on Averroes's theory that all humans share the same intellect. He also opposed Averroes on the eternity of the universe and divine providence. Ramon Llull

Ramon Llull (; ; – 1316), sometimes anglicized as ''Raymond Lully'', was a philosopher, theologian, poet, missionary, Christian apologist and former knight from the Kingdom of Majorca.

He invented a philosophical system known as the ''Art ...

opposed Averroism and established a distinction between a religion that could be tolerated—Islam—and a philosophy that should be opposed—Averroism, especially in its Latin version.

The Catholic Church's condemnations of 1270 and 1277, and the detailed critique by Aquinas weakened the spread of Averroism in Latin Christendom, though it maintained a following until the sixteenth century, when European thought began to diverge from Aristotelianism. Leading Averroists in the following centuries included John of Jandun and Marsilius of Padua (fourteenth century), Gaetano da Thiene and Pietro Pomponazzi (fifteenth century), and Agostino Nifo and Marcantonio Zimara (sixteenth century).

In Islamic tradition

Averroes had no major influence on Islamic philosophic thought until modern times. Part of the reason was geography; Averroes lived in Spain, the extreme west of the Islamic civilization far from the centers of Islamic intellectual traditions. Also, his philosophy may not have appealed to Islamic scholars of his time. His focus on Aristotle's works was outdated in the twelfth-century Muslim world, which had already scrutinized Aristotle since the ninth century and by now was engaging deeply with newer schools of thought, especially that ofAvicenna

Ibn Sina ( – 22 June 1037), commonly known in the West as Avicenna ( ), was a preeminent philosopher and physician of the Muslim world, flourishing during the Islamic Golden Age, serving in the courts of various Iranian peoples, Iranian ...

. In the nineteenth century, Muslim thinkers began to engage with the works of Averroes again. By this time, there was a cultural renaissance called '' Al-Nahda'' ("reawakening") in the Arabic-speaking world and the works of Averroes were seen as inspiration to modernize the Muslim intellectual tradition.

Cultural references

References to Averroes appear in the popular culture of both the western and Muslim world. The poem '' The Divine Comedy'' by the Italian writer Dante Alighieri, completed in 1320, depicts Averroes, "who made the Great Commentary", along with other non-Christian Greek and Muslim thinkers, in the first circle of hell around

References to Averroes appear in the popular culture of both the western and Muslim world. The poem '' The Divine Comedy'' by the Italian writer Dante Alighieri, completed in 1320, depicts Averroes, "who made the Great Commentary", along with other non-Christian Greek and Muslim thinkers, in the first circle of hell around Saladin

Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub ( – 4 March 1193), commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, h ...

. The prologue of '' The Canterbury Tales'' (1387) by Geoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer ( ; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He w ...

lists Averroes among other medical authorities known in Europe at the time. Averroes is depicted in Raphael

Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino (; March 28 or April 6, 1483April 6, 1520), now generally known in English as Raphael ( , ), was an Italian painter and architect of the High Renaissance. List of paintings by Raphael, His work is admired for its cl ...

's 1501 fresco '' The School of Athens'' that decorates the Apostolic Palace

The Apostolic Palace is the official residence of the Pope, the head of the Catholic Church, located in Vatican City. It is also known as the Papal Palace, the Palace of the Vatican and the Vatican Palace. The Vatican itself refers to the build ...

in the Vatican

Vatican may refer to:

Geography

* Vatican City, an independent city-state surrounded by Rome, Italy

* Vatican Hill, in Rome, namesake of Vatican City

* Ager Vaticanus, an alluvial plain in Rome

* Vatican, an unincorporated community in the ...

, which features seminal figures of philosophy. In the painting, Averroes wears a green robe and a turban, and peers out from behind Pythagoras, who is shown writing a book.

Averroes is referenced briefly in Victor Hugo

Victor-Marie Hugo, vicomte Hugo (; 26 February 1802 – 22 May 1885) was a French Romanticism, Romantic author, poet, essayist, playwright, journalist, human rights activist and politician.

His most famous works are the novels ''The Hunchbac ...

's '' The Hunchback of Notre-Dame'' (written 1831, but set in the Paris of 1482). The novel's villain, the Priest Claude Frollo, extols Averroes' talents as an alchemist in his obsessive quest to find the Philosophers Stone.

A 1947 short story by Jorge Luis Borges

Jorge Francisco Isidoro Luis Borges Acevedo ( ; ; 24 August 1899 – 14 June 1986) was an Argentine short-story writer, essayist, poet and translator regarded as a key figure in Spanish literature, Spanish-language and international literatur ...

, " Averroes's Search" (), features his attempts to understand Aristotle's ''Poetics'' within a culture that lacks a tradition of live theatrical performance. In the afterwords of the story, Borges comments, "I felt that he storymocked me, foiled me, thwarted me. I felt that Averroës, trying to imagine what a play is without ever having suspected what a theater is, was no more absurd than I, trying to imagine Averroës yet with no more material than a few snatches from Renan, Lane, and Asín Palacios." Averroes is also the hero of the 1997 Egyptian movie ''Destiny

Destiny, sometimes also called fate (), is a predetermined course of events. It may be conceived as a predetermined future, whether in general or of an individual.

Fate

Although often used interchangeably, the words ''fate'' and ''destiny'' ...

'' by Youssef Chahine, made partly in commemoration of the 800th anniversary of his death. The plant genus ''Averrhoa

''Averrhoa'' is a genus of trees in the family Oxalidaceae. It includes five species native to Java, the Maluku Islands, New Guinea, Sulawesi, and Vietnam. The genus is named after Averroes, a 12th-century astronomer and philosopher from Muslim S ...

'' (whose members include the starfruit and the bilimbi

''Averrhoa bilimbi'' (commonly known as bilimbi, cucumber tree, or tree sorrel) is a fruit-bearing tree of the genus ''Averrhoa'', family (biology), family Oxalidaceae. It is believed to be originally native to the Maluku Islands of Indonesia but ...

), the lunar crater ibn Rushd, and the asteroid

An asteroid is a minor planet—an object larger than a meteoroid that is neither a planet nor an identified comet—that orbits within the Solar System#Inner Solar System, inner Solar System or is co-orbital with Jupiter (Trojan asteroids). As ...

8318 Averroes are named after him.

Mael Malihabadi's 1957 Urdu historical fiction novel ''Falsafi ibn-e Rushd'' revolves around his life.

Notes

References

Works cited

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Works of Averroes

DARE

the Digital Averroes Research Environment, an ongoing effort to collect digital images of all Averroes manuscripts and full texts of all three language-traditions.

Islamic Philosophy Online (links to works by and about Averroes in several languages)

''The Philosophy and Theology of Averroes: Tractata translated from the Arabic''

trans. Mohammad Jamil-ur-Rehman, 1921

translation by Simon van den Bergh. [''N.B. '': Because these refutations consist mainly of commentary on statements by al-Ghazali which are quoted verbatim, this work contains a translation of most of the Tahafut.] There is also an Italian translation by Massimo Campanini, Averroè, ''L'incoerenza dell'incoerenza dei filosofi'', Turin, Utet, 1997.

SIEPM virtual library, including scanned copies (PDF) of the Editio Juntina of Averroes's works in Latin (Venice 1550–1562) *

Information about Averroes

* * on the Internet Encyclopedia of PhilosophyBibliography

a comprehensive overview of the extant bibliography

Averroes Database

including a full bibliography of his works

Podcast on Averroes

at NPR's '' Throughline'' {{Authority control 1126 births 1198 deaths 12th-century writers from al-Andalus 12th-century astronomers 12th-century Spanish philosophers 12th-century physicians Scholars from the Almohad Caliphate Arabic-language commentators on Aristotle Aristotelian philosophers Commentators on Plato Characters in the Divine Comedy Epistemologists Spanish ethicists Medieval Islamic philosophers Logicians Medieval Spanish astronomers Astronomers from al-Andalus Physicians from al-Andalus Medieval physicists Maliki scholars from al-Andalus 12th-century Muslim theologians Ontologists People from Córdoba, Spain Philosophers of culture Philosophers of history Philosophers of language Philosophers of literature Philosophers of logic Philosophers of mind Philosophers of psychology Philosophers of religion Philosophers of science Political philosophers Spanish psychologists Social philosophers Sunni Muslim scholars of Islam World Digital Library exhibits Philosophers from al-Andalus Spanish Sunni Muslims Muslim critics of atheism Critics of deism Critics of Christianity