Hydrogen is a

chemical element

A chemical element is a chemical substance whose atoms all have the same number of protons. The number of protons is called the atomic number of that element. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8: each oxygen atom has 8 protons in its ...

; it has

symbol

A symbol is a mark, Sign (semiotics), sign, or word that indicates, signifies, or is understood as representing an idea, physical object, object, or wikt:relationship, relationship. Symbols allow people to go beyond what is known or seen by cr ...

H and

atomic number

The atomic number or nuclear charge number (symbol ''Z'') of a chemical element is the charge number of its atomic nucleus. For ordinary nuclei composed of protons and neutrons, this is equal to the proton number (''n''p) or the number of pro ...

1. It is the lightest and

most abundant chemical element in the

universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents. It comprises all of existence, any fundamental interaction, physical process and physical constant, and therefore all forms of matter and energy, and the structures they form, from s ...

, constituting about 75% of all

normal matter. Under

standard conditions

Standard temperature and pressure (STP) or standard conditions for temperature and pressure are various standard sets of conditions for experimental measurements used to allow comparisons to be made between different sets of data. The most used ...

, hydrogen is a

gas

Gas is a state of matter that has neither a fixed volume nor a fixed shape and is a compressible fluid. A ''pure gas'' is made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon) or molecules of either a single type of atom ( elements such as ...

of

diatomic molecule

Diatomic molecules () are molecules composed of only two atoms, of the same or different chemical elements. If a diatomic molecule consists of two atoms of the same element, such as hydrogen () or oxygen (), then it is said to be homonuclear mol ...

s with the

formula

In science, a formula is a concise way of expressing information symbolically, as in a mathematical formula or a ''chemical formula''. The informal use of the term ''formula'' in science refers to the general construct of a relationship betwe ...

, called dihydrogen, or sometimes hydrogen gas, molecular hydrogen, or simply hydrogen. Dihydrogen is colorless, odorless, non-toxic, and highly

combustible

A combustible material is a material that can burn (i.e., sustain a flame) in air under certain conditions. A material is flammable if it ignites easily at ambient temperatures. In other words, a combustible material ignites with some effort a ...

.

Stars

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of ...

, including the

Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

, mainly consist of hydrogen in a

plasma state

Plasma () is a state of matter characterized by the presence of a significant portion of charged particles in any combination of ions or electrons. It is the most abundant form of ordinary matter in the universe, mostly in stars (including the ...

, while on Earth, hydrogen is found as the gas (dihydrogen) and in

molecular forms, such as in

water

Water is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It is a transparent, tasteless, odorless, and Color of water, nearly colorless chemical substance. It is the main constituent of Earth's hydrosphere and the fluids of all known liv ...

and

organic compounds

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

. The most common

isotope of hydrogen

Hydrogen (H) has three naturally occurring isotopes: H, H, and H. H and H are stable, while H has a half-life of years. Heavier isotopes also exist; all are synthetic and have a half-life of less than 1 zeptosecond (10 s).

Of these, H is t ...

(H) consists of one

proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , Hydron (chemistry), H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and approximately times the mass of an e ...

, one

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

, and no

neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

s.

Hydrogen gas was first produced artificially in the 17th century by the reaction of acids with metals.

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable a ...

, in 1766–1781, identified hydrogen gas as a distinct substance and discovered its property of producing water when burned; hence its name means 'water-former' in Greek. Understanding the colors of light absorbed and emitted by hydrogen was a crucial part of developing

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

.

Hydrogen, typically

nonmetallic

Nonmetallic material, or in nontechnical terms a ''nonmetal'', refers to materials which are not metals. Depending upon context it is used in slightly different ways. In everyday life it would be a generic term for those materials such as plastic ...

except under

extreme pressure, readily forms

covalent bonds

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atom ...

with most nonmetals, contributing to the formation of compounds like water and various organic substances. Its role is crucial in

acid-base reactions, which mainly involve proton exchange among soluble molecules. In

ionic compounds

In chemistry, a salt or ionic compound is a chemical compound consisting of an assembly of positively charged ions ( cations) and negatively charged ions (anions), which results in a compound with no net electric charge (electrically neutral). ...

, hydrogen can take the form of either a negatively charged

anion

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

, where it is known as

hydride

In chemistry, a hydride is formally the anion of hydrogen (H−), a hydrogen ion with two electrons. In modern usage, this is typically only used for ionic bonds, but it is sometimes (and has been more frequently in the past) applied to all che ...

, or as a positively charged

cation

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge. The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by convent ...

, , called a proton. Although tightly bonded to water molecules, protons strongly affect the behavior of

aqueous solution

An aqueous solution is a solution in which the solvent is water. It is mostly shown in chemical equations by appending (aq) to the relevant chemical formula. For example, a solution of table salt, also known as sodium chloride (NaCl), in water ...

s, as reflected in the importance of pH. Hydride, on the other hand, is rarely observed because it tends to deprotonate solvents, yielding .

In the

early universe, neutral hydrogen atoms formed about 370,000 years after the

Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

as the universe expanded and plasma had cooled enough for electrons to remain bound to protons. Once stars formed most of the atoms in the

intergalactic medium

Intergalactic may refer to:

* "Intergalactic" (song), a song by the Beastie Boys

* ''Intergalactic'' (TV series), a 2021 UK science fiction TV series

* Intergalactic space

* Intergalactic travel, travel between galaxies in science fiction and ...

re-ionized.

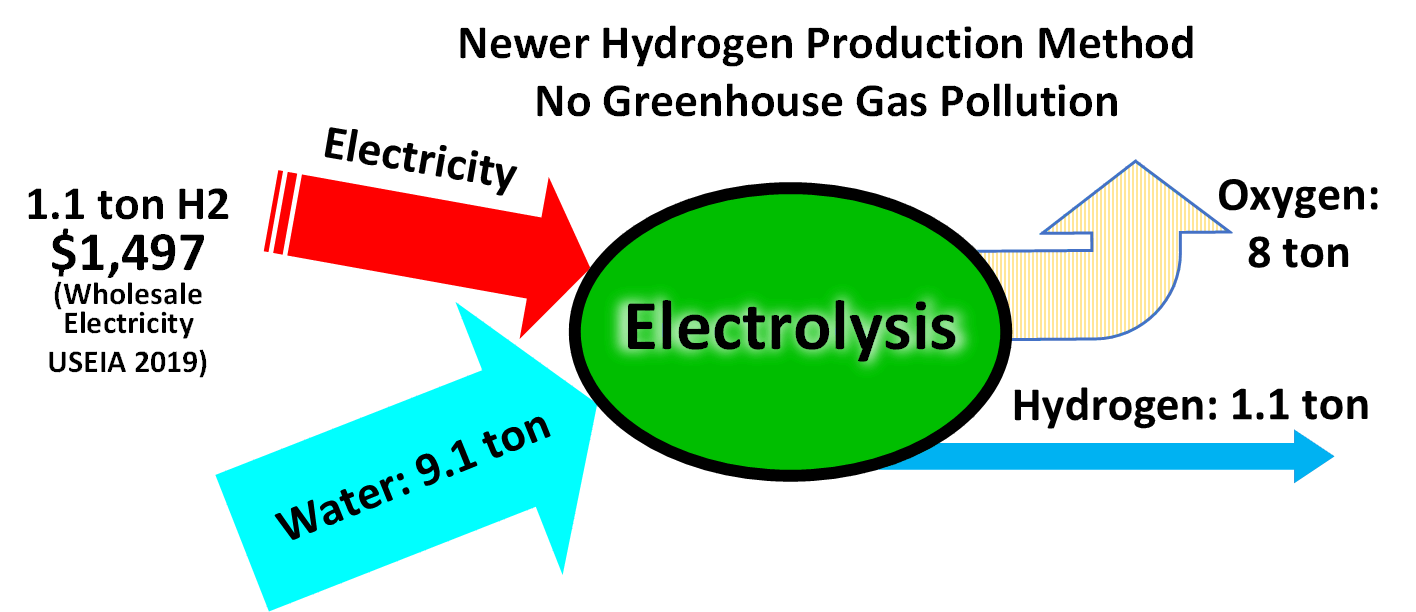

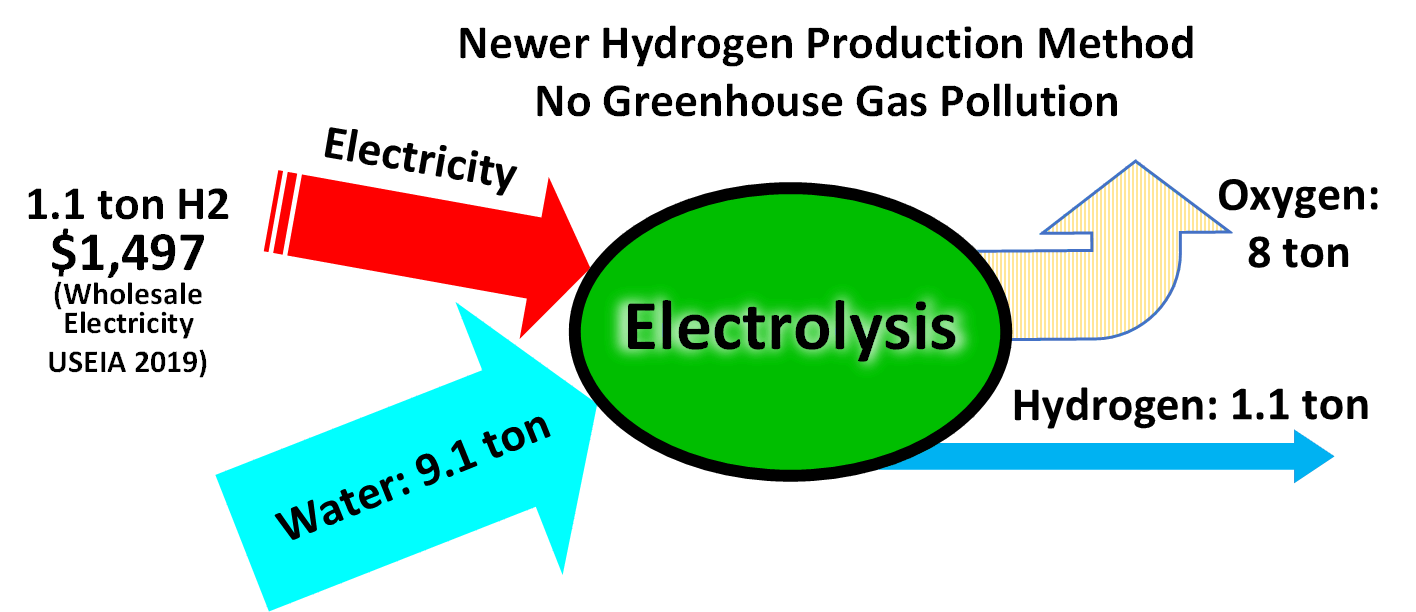

Nearly all

hydrogen production

Hydrogen gas is produced by several industrial methods. Nearly all of the world's current supply of hydrogen is created from fossil fuels. Article in press. Most hydrogen is ''gray hydrogen'' made through steam methane reforming. In this process, ...

is done by transforming fossil fuels, particularly

steam reforming

Steam reforming or steam methane reforming (SMR) is a method for producing syngas (hydrogen and carbon monoxide) by reaction of hydrocarbons with water. Commonly, natural gas is the feedstock. The main purpose of this technology is often hydrogen ...

of

natural gas

Natural gas (also fossil gas, methane gas, and gas) is a naturally occurring compound of gaseous hydrocarbons, primarily methane (95%), small amounts of higher alkanes, and traces of carbon dioxide and nitrogen, hydrogen sulfide and helium ...

. It can also be produced from water or saline by

electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

, but this process is more expensive. Its main industrial uses include

fossil fuel

A fossil fuel is a flammable carbon compound- or hydrocarbon-containing material formed naturally in the Earth's crust from the buried remains of prehistoric organisms (animals, plants or microplanktons), a process that occurs within geolog ...

processing and

ammonia production

Ammonia production takes place worldwide, mostly in large-scale manufacturing plants that produce 240 million metric tonnes of ammonia (2023) annually. Based on the annual production in 2023 the major part (~70%) of the production facilities are b ...

for fertilizer. Emerging uses for hydrogen include the use of

fuel cell

A fuel cell is an electrochemical cell that converts the chemical energy of a fuel (often hydrogen fuel, hydrogen) and an oxidizing agent (often oxygen) into electricity through a pair of redox reactions. Fuel cells are different from most bat ...

s to generate electricity.

Properties

Atomic hydrogen

Electron energy levels

The

ground state

The ground state of a quantum-mechanical system is its stationary state of lowest energy; the energy of the ground state is known as the zero-point energy of the system. An excited state is any state with energy greater than the ground state ...

energy level

A quantum mechanics, quantum mechanical system or particle that is bound state, bound—that is, confined spatially—can only take on certain discrete values of energy, called energy levels. This contrasts with classical mechanics, classical pa ...

of the electron in a hydrogen atom is −13.6

eV, equivalent to an

ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

photon

A photon () is an elementary particle that is a quantum of the electromagnetic field, including electromagnetic radiation such as light and radio waves, and the force carrier for the electromagnetic force. Photons are massless particles that can ...

of roughly 91 nm wavelength. The energy levels of hydrogen are referred to by consecutive

quantum number

In quantum physics and chemistry, quantum numbers are quantities that characterize the possible states of the system.

To fully specify the state of the electron in a hydrogen atom, four quantum numbers are needed. The traditional set of quantu ...

s, with

being the ground state. The

hydrogen spectral series

The emission spectrum of atomic hydrogen has been divided into a number of ''spectral series'', with wavelengths given by the Rydberg formula. These observed spectral lines are due to the electron making transitions between two energy levels i ...

corresponds to emission of light due to transitions from higher to lower energy levels. Each energy level is further split by

spin interactions between the electron and proton into 4

hyperfine levels.

High precision values for the hydrogen atom energy levels are required for definitions of physical constants. Quantum calculations have identified 9 contributions to the energy levels. The eigenvalue from the

Dirac equation

In particle physics, the Dirac equation is a relativistic wave equation derived by British physicist Paul Dirac in 1928. In its free form, or including electromagnetic interactions, it describes all spin-1/2 massive particles, called "Dirac ...

is the largest contribution. Other terms include

relativistic recoil, the

self-energy

In quantum field theory, the energy that a particle has as a result of changes that it causes in its environment defines its self-energy \Sigma. The self-energy represents the contribution to the particle's energy, or effective mass, due to inter ...

, and the

vacuum polarization

In quantum field theory, and specifically quantum electrodynamics, vacuum polarization describes a process in which a background electromagnetic field produces virtual electron–positron pairs that change the distribution of charges and curr ...

terms.

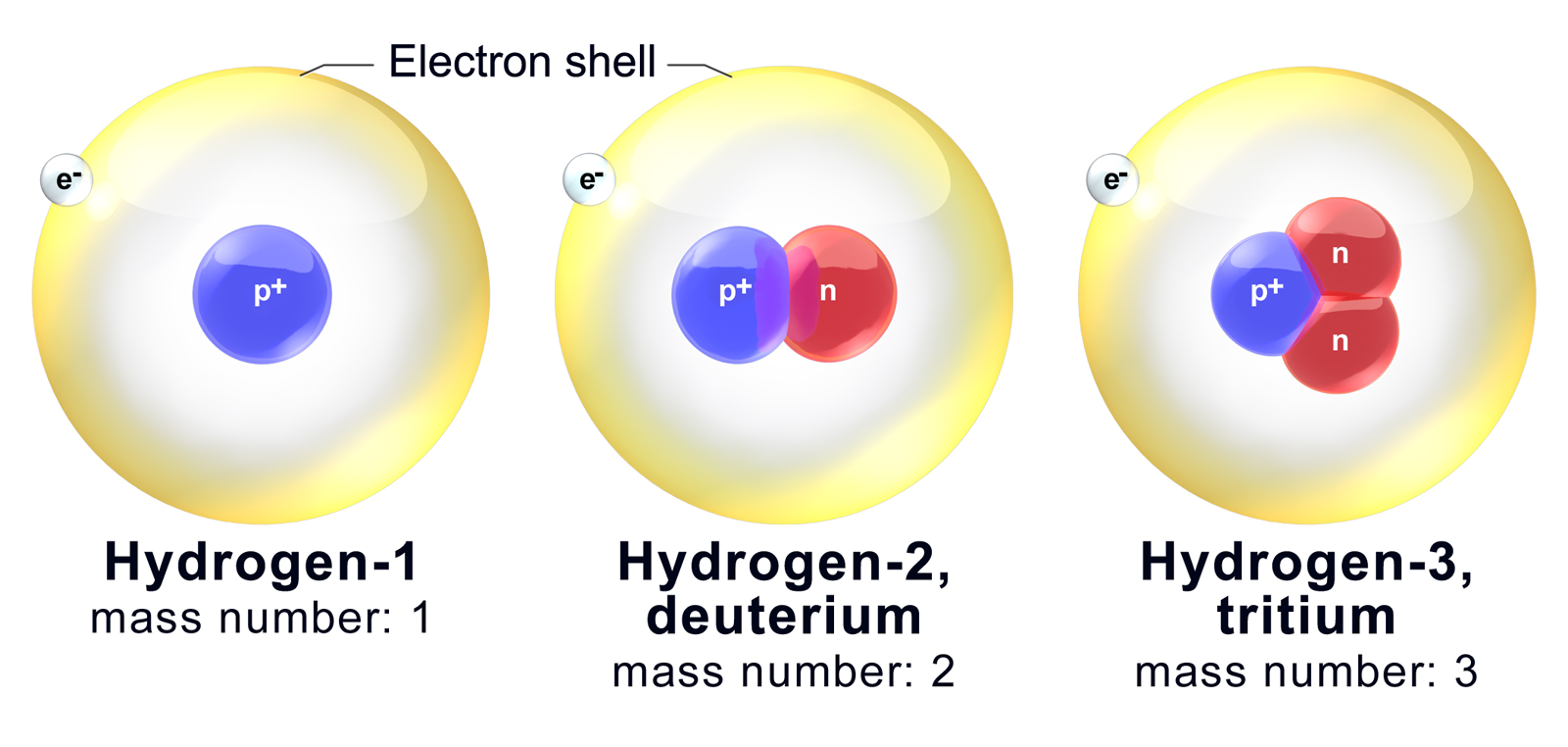

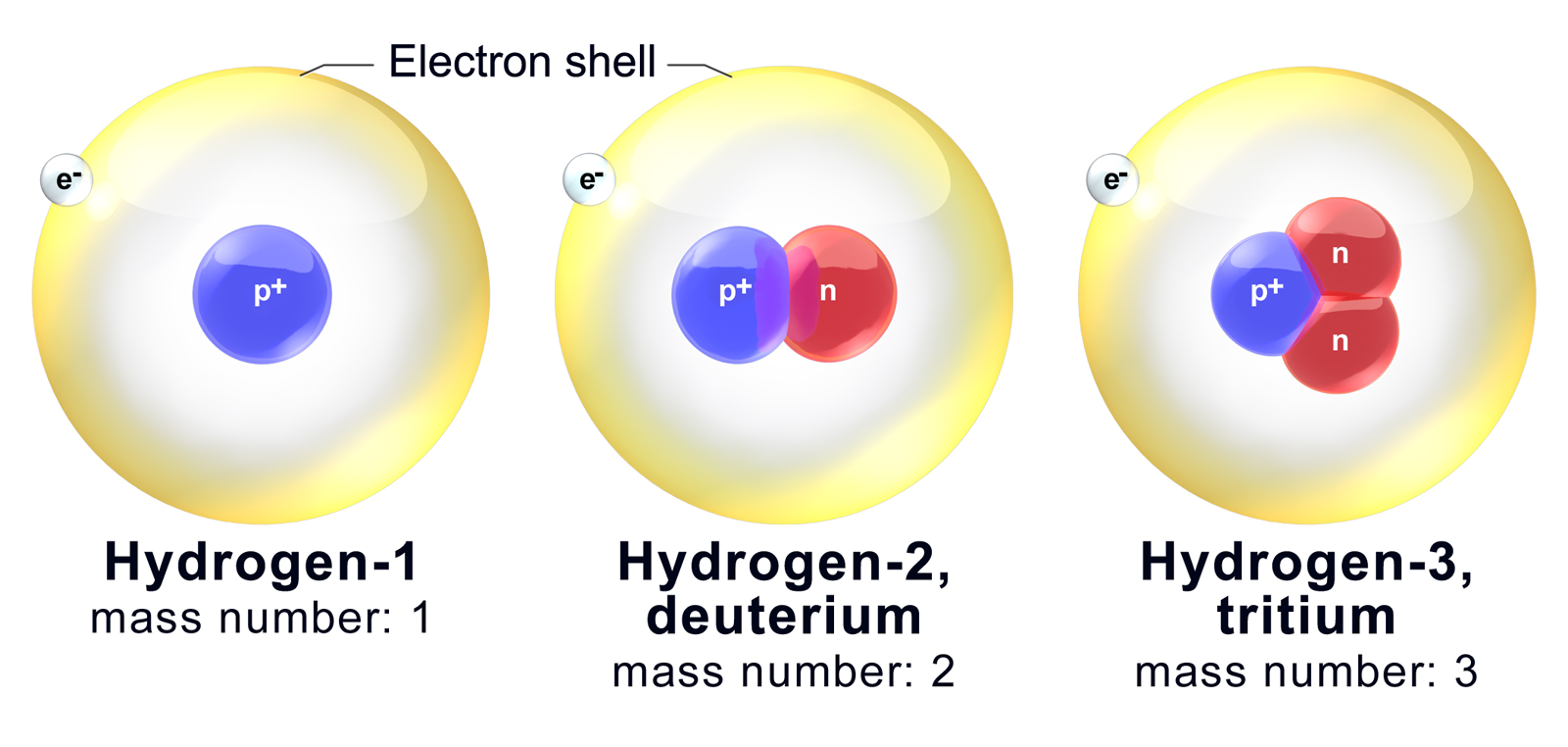

Isotopes

Hydrogen has three naturally occurring isotopes, denoted , and . Other, highly unstable nuclei ( to ) have been synthesized in the laboratory but not observed in nature.

is the most common hydrogen isotope, with an abundance of >99.98%. Because the

nucleus

Nucleus (: nuclei) is a Latin word for the seed inside a fruit. It most often refers to:

*Atomic nucleus, the very dense central region of an atom

*Cell nucleus, a central organelle of a eukaryotic cell, containing most of the cell's DNA

Nucleu ...

of this isotope consists of only a single proton, it is given the descriptive but rarely used formal name ''protium''. It is the only stable isotope with no neutrons; see

diproton

Helium (He) ( standard atomic weight: ) has nine known isotopes, but only helium-3 (He) and helium-4 (He) are stable. All radioisotopes are short-lived; the longest-lived is He with half-life . The least stable is He, with half-life (), though He ...

for a discussion of why others do not exist.

, the other stable hydrogen isotope, is known as

deuterium

Deuterium (hydrogen-2, symbol H or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen; the other is protium, or hydrogen-1, H. The deuterium nucleus (deuteron) contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more c ...

and contains one proton and one

neutron

The neutron is a subatomic particle, symbol or , that has no electric charge, and a mass slightly greater than that of a proton. The Discovery of the neutron, neutron was discovered by James Chadwick in 1932, leading to the discovery of nucle ...

in the nucleus. Nearly all deuterium nuclei in the universe is thought to have been produced at the time of the

Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

, and has endured since then. Deuterium is not radioactive, and is not a significant toxicity hazard. Water enriched in molecules that include deuterium instead of normal hydrogen is called

heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

. Deuterium and its compounds are used as a non-radioactive label in chemical experiments and in solvents for -

NMR spectroscopy

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, most commonly known as NMR spectroscopy or magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), is a spectroscopic technique based on re-orientation of atomic nuclei with non-zero nuclear spins in an external magnetic f ...

. Heavy water is used as a

neutron moderator

In nuclear engineering, a neutron moderator is a medium that reduces the speed of fast neutrons, ideally without capturing any, leaving them as thermal neutrons with only minimal (thermal) kinetic energy. These thermal neutrons are immensely ...

and coolant for nuclear reactors. Deuterium is also a potential fuel for commercial

nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction, reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutrons, neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the rele ...

.

is known as

tritium

Tritium () or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of ~12.33 years. The tritium nucleus (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of the ...

and contains one proton and two neutrons in its nucleus. It is radioactive, decaying into

helium-3

Helium-3 (3He see also helion) is a light, stable isotope of helium with two protons and one neutron. (In contrast, the most common isotope, helium-4, has two protons and two neutrons.) Helium-3 and hydrogen-1 are the only stable nuclides with ...

through

beta decay

In nuclear physics, beta decay (β-decay) is a type of radioactive decay in which an atomic nucleus emits a beta particle (fast energetic electron or positron), transforming into an isobar of that nuclide. For example, beta decay of a neutron ...

with a

half-life Half-life is a mathematical and scientific description of exponential or gradual decay.

Half-life, half life or halflife may also refer to:

Film

* Half-Life (film), ''Half-Life'' (film), a 2008 independent film by Jennifer Phang

* ''Half Life: ...

of 12.32 years.

It is radioactive enough to be used in

luminous paint

Luminous paint (or luminescent paint) is paint that emits visible light through fluorescence, phosphorescence, or radioluminescence.

Fluorescent paint

Fluorescent paints 'glow' when exposed to short-wave ultraviolet (UV) radiation. These UV ...

to enhance the visibility of data displays, such as for painting the hands and dial-markers of watches. The watch glass prevents the small amount of radiation from escaping the case.

Small amounts of tritium are produced naturally by cosmic rays striking atmospheric gases; tritium has also been released in

nuclear weapons tests. It is used in nuclear fusion, as a tracer in

isotope geochemistry

Isotope geochemistry is an aspect of geology based upon the study of natural variations in the relative abundances of isotopes of various Chemical element, elements. Variations in isotopic abundance are measured by isotope-ratio mass spectrometry, ...

, and in specialized

self-powered lighting

Tritium radioluminescence is the use of gaseous tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen, to create visible light. Tritium emits electrons through beta decay and, when they interact with a phosphor material, light is emitted through the proc ...

devices. Tritium has also been used in chemical and biological labeling experiments as a

radiolabel

A radioactive tracer, radiotracer, or radioactive label is a synthetic derivative of a natural compound in which one or more atoms have been replaced by a radionuclide (a radioactive atom). By virtue of its radioactive decay, it can be used to exp ...

.

Unique among the elements, distinct names are assigned to its isotopes in common use. During the early study of radioactivity, heavy radioisotopes were given their own names, but these are mostly no longer used. The symbols D and T (instead of and ) are sometimes used for deuterium and tritium, but the symbol P was already used for

phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol P and atomic number 15. All elemental forms of phosphorus are highly Reactivity (chemistry), reactive and are therefore never found in nature. They can nevertheless be prepared ar ...

and thus was not available for protium. In its

nomenclatural guidelines, the

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC ) is an international federation of National Adhering Organizations working for the advancement of the chemical sciences, especially by developing nomenclature and terminology. It is ...

(IUPAC) allows any of D, T, , and to be used, though and are preferred.

Antihydrogen

Antihydrogen () is the antimatter counterpart of hydrogen. Whereas the common hydrogen atom is composed of an electron and proton, the antihydrogen atom is made up of a positron and antiproton. Scientists hope that studying antihydrogen may sh ...

() is the

antimatter

In modern physics, antimatter is defined as matter composed of the antiparticles (or "partners") of the corresponding subatomic particle, particles in "ordinary" matter, and can be thought of as matter with reversed charge and parity, or go ...

counterpart to hydrogen. It consists of an

antiproton

The antiproton, , (pronounced ''p-bar'') is the antiparticle of the proton. Antiprotons are stable, but they are typically short-lived, since any collision with a proton will cause both particles to be annihilated in a burst of energy.

The exis ...

with a

positron

The positron or antielectron is the particle with an electric charge of +1''elementary charge, e'', a Spin (physics), spin of 1/2 (the same as the electron), and the same Electron rest mass, mass as an electron. It is the antiparticle (antimatt ...

. Antihydrogen is the only type of antimatter atom to have been produced .

The

exotic atom

An exotic atom is an otherwise normal atom in which one or more sub-atomic particles have been replaced by other particles. For example, electrons may be replaced by other negatively charged particles such as muons (muonic atoms) or pions (pionic a ...

muonium

Muonium () is an exotic atom made up of an antimuon and an electron,

which was discovered in 1960 by Vernon W. Hughes

and is given the chemical symbol Mu. During the muon's lifetime, muonium can undergo chemical reactions. Description

Beca ...

(symbol Mu), composed of an anti

muon

A muon ( ; from the Greek letter mu (μ) used to represent it) is an elementary particle similar to the electron, with an electric charge of −1 '' e'' and a spin of ''ħ'', but with a much greater mass. It is classified as a ...

and an

electron

The electron (, or in nuclear reactions) is a subatomic particle with a negative one elementary charge, elementary electric charge. It is a fundamental particle that comprises the ordinary matter that makes up the universe, along with up qua ...

, is analogous hydrogen and IUPAC nomenclature incorporates such hypothetical compounds as muonium chloride (MuCl) and sodium muonide (NaMu), analogous to

hydrogen chloride

The Chemical compound, compound hydrogen chloride has the chemical formula and as such is a hydrogen halide. At room temperature, it is a colorless gas, which forms white fumes of hydrochloric acid upon contact with atmospheric water vapor. Hyd ...

and

sodium hydride

Sodium hydride is the chemical compound with the empirical formula Na H. This alkali metal hydride is primarily used as a strong yet combustible base in organic synthesis. NaH is a saline (salt-like) hydride, composed of Na+ and H− ions, in co ...

respectively.

Dihydrogen

Under

standard conditions

Standard temperature and pressure (STP) or standard conditions for temperature and pressure are various standard sets of conditions for experimental measurements used to allow comparisons to be made between different sets of data. The most used ...

, hydrogen is a

gas

Gas is a state of matter that has neither a fixed volume nor a fixed shape and is a compressible fluid. A ''pure gas'' is made up of individual atoms (e.g. a noble gas like neon) or molecules of either a single type of atom ( elements such as ...

of

diatomic molecule

Diatomic molecules () are molecules composed of only two atoms, of the same or different chemical elements. If a diatomic molecule consists of two atoms of the same element, such as hydrogen () or oxygen (), then it is said to be homonuclear mol ...

s with the

formula

In science, a formula is a concise way of expressing information symbolically, as in a mathematical formula or a ''chemical formula''. The informal use of the term ''formula'' in science refers to the general construct of a relationship betwe ...

, officially called "dihydrogen", but also called "molecular hydrogen",

or simply hydrogen. Dihydrogen is a colorless, odorless, flammable gas.

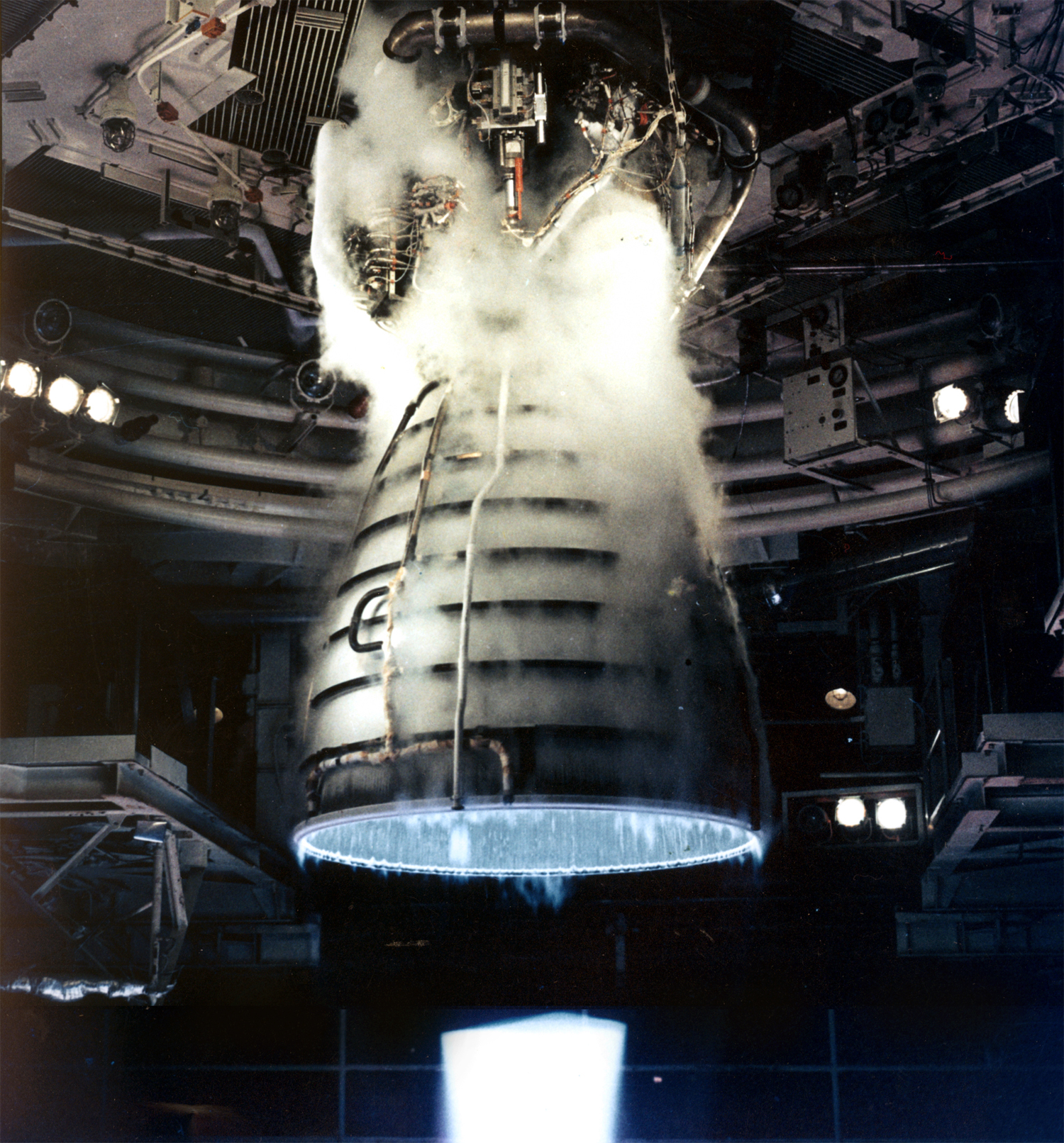

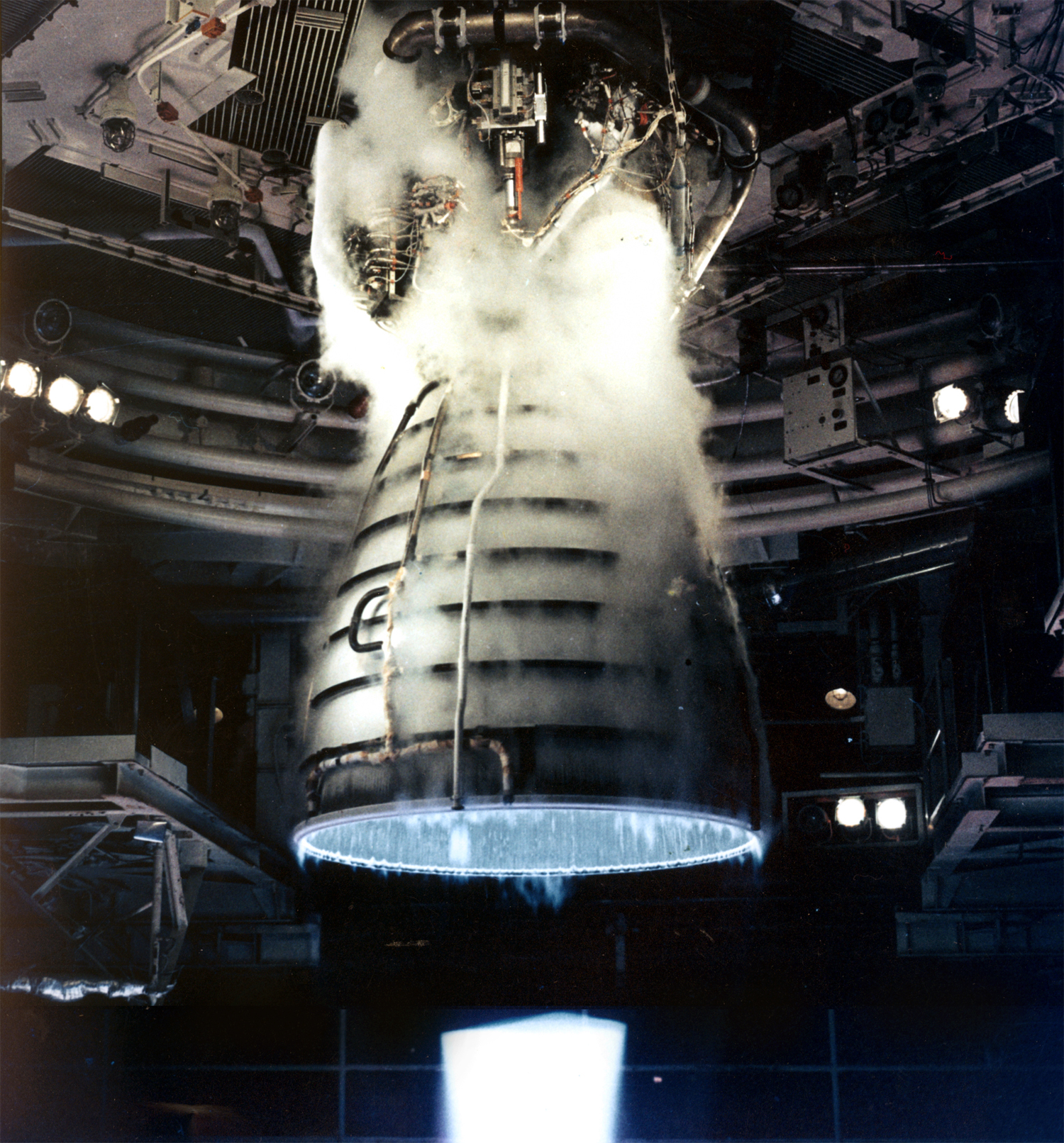

Combustion

Hydrogen gas is highly flammable, reacting with

oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

in air, to produce liquid water:

:

The

amount of heat released per

mole

Mole (or Molé) may refer to:

Animals

* Mole (animal) or "true mole"

* Golden mole, southern African mammals

* Marsupial mole

Marsupial moles, the Notoryctidae family, are two species of highly specialized marsupial mammals that are found i ...

of hydrogen is −286 kJ or 141.865 MJ for a kilogram mass.

Hydrogen gas forms explosive mixtures with air in concentrations from 4–74% and with chlorine at 5–95%. The hydrogen

autoignition temperature

The autoignition temperature or self-ignition temperature, often called spontaneous ignition temperature or minimum ignition temperature (or shortly ignition temperature) and formerly also known as kindling point, of a substance is the lowest tem ...

, the temperature of spontaneous ignition in air, is . In a high-pressure hydrogen leak, the shock wave from the leak itself can heat air to the autoignition temperature, leading to flaming and possibly explosion.

Hydrogen flames emit faint blue and

ultraviolet

Ultraviolet radiation, also known as simply UV, is electromagnetic radiation of wavelengths of 10–400 nanometers, shorter than that of visible light, but longer than X-rays. UV radiation is present in sunlight and constitutes about 10% of ...

light.

Flame detectors are used to detect hydrogen fires as they are nearly invisible to the naked eye in daylight.

Spin isomers

Molecular exists as two

nuclear isomer

A nuclear isomer is a metastable state of an atomic nucleus, in which one or more nucleons (protons or neutrons) occupy excited state levels (higher energy levels). "Metastable" describes nuclei whose excited states have Half-life, half-lives of ...

s that differ in the

spin states of their nuclei.

In the orthohydrogen form, the spins of the two nuclei are parallel, forming a spin

triplet state

In quantum mechanics, a triplet state, or spin triplet, is the quantum state of an object such as an electron, atom, or molecule, having a quantum spin ''S'' = 1. It has three allowed values of the spin's projection along a given axis ''m''S = � ...

having a

total molecular spin ; in the parahydrogen form the spins are antiparallel and form a spin

singlet state

In quantum mechanics, a singlet state usually refers to a system in which all electrons are paired. The term 'singlet' originally meant a linked set of particles whose net angular momentum is zero, that is, whose overall spin quantum number s=0. A ...

having spin

. The equilibrium ratio of ortho- to para-hydrogen depends on temperature. At room temperature or warmer, equilibrium hydrogen gas contains about 25% of the para form and 75% of the ortho form.

The ortho form is an

excited state

In quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Add ...

, having higher energy than the para form by 1.455 kJ/mol,

and it converts to the para form over the course of several minutes when cooled to low temperature. The thermal properties of these isomers differ because each has distinct

rotational quantum states.

The ortho-to-para ratio in is an important consideration in the

liquefaction

In materials science, liquefaction is a process that generates a liquid from a solid or a gas or that generates a non-liquid phase which behaves in accordance with fluid dynamics.

It occurs both naturally and artificially. As an example of t ...

and storage of

liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen () is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecule, molecular H2 form.

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point (thermodynamics), critical point of 33 Kelvins, ...

: the conversion from ortho to para is

exothermic

In thermodynamics, an exothermic process () is a thermodynamic process or reaction that releases energy from the system to its surroundings, usually in the form of heat, but also in a form of light (e.g. a spark, flame, or flash), electricity (e ...

and produces sufficient heat to evaporate most of the liquid if not converted first to parahydrogen during the cooling process.

Catalyst

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

s for the ortho-para interconversion, such as

ferric oxide

Iron(III) oxide or ferric oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula . It occurs in nature as the mineral hematite, which serves as the primary source of iron for the steel industry. It is also known as red iron oxide, especially when us ...

and

activated carbon

Activated carbon, also called activated charcoal, is a form of carbon commonly used to filter contaminants from water and air, among many other uses. It is processed (activated) to have small, low-volume pores that greatly increase the surface ar ...

compounds, are used during hydrogen cooling to avoid this loss of liquid.

Phases

Liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen () is the liquid state of the element hydrogen. Hydrogen is found naturally in the molecule, molecular H2 form.

To exist as a liquid, H2 must be cooled below its critical point (thermodynamics), critical point of 33 Kelvins, ...

can exist at temperatures below hydrogen's

critical point of 33

K. However, for it to be in a fully liquid state at

atmospheric pressure

Atmospheric pressure, also known as air pressure or barometric pressure (after the barometer), is the pressure within the atmosphere of Earth. The standard atmosphere (symbol: atm) is a unit of pressure defined as , which is equivalent to 1,013. ...

, H

2 needs to be cooled to . Hydrogen was liquefied by

James Dewar

Sir James Dewar ( ; 20 September 1842 – 27 March 1923) was a Scottish chemist and physicist. He is best known for his invention of the vacuum flask, which he used in conjunction with research into the liquefaction of gases. He also studie ...

in 1898 by using

regenerative cooling

Regenerative cooling is a method of cooling gases in which compressed gas is cooled by allowing it to expand and thereby take heat from the surroundings. The cooled expanded gas then passes through a heat exchanger where it cools the incoming com ...

and his invention, the

vacuum flask

A vacuum flask (also known as a Dewar flask, Dewar bottle or thermos) is an insulating storage vessel that slows the speed at which its contents change in temperature. It greatly lengthens the time over which its contents remain hotter or coo ...

.

Liquid hydrogen becomes

solid hydrogen

Solid hydrogen is the solid state of the element hydrogen. At standard pressure, this is achieved by decreasing the temperature below hydrogen's melting point of . It was collected for the first time by James Dewar in 1899 and published with the ...

at

standard pressure

Standard temperature and pressure (STP) or standard conditions for temperature and pressure are various standard sets of conditions for experimental measurements used to allow comparisons to be made between different sets of data. The most used ...

below hydrogen's

melting point

The melting point (or, rarely, liquefaction point) of a substance is the temperature at which it changes state of matter, state from solid to liquid. At the melting point the solid and liquid phase (matter), phase exist in Thermodynamic equilib ...

of . Distinct solid phases exist, known as Phase I through Phase V, each exhibiting a characteristic molecular arrangement.

Liquid and solid phases can exist in combination at the

triple point

In thermodynamics, the triple point of a substance is the temperature and pressure at which the three Phase (matter), phases (gas, liquid, and solid) of that substance coexist in thermodynamic equilibrium.. It is that temperature and pressure at ...

, a substance known as

slush hydrogen Slush hydrogen is a combination of liquid hydrogen and solid hydrogen at the triple point with a lower temperature and a higher density than liquid hydrogen. It is commonly formed by repeating a freeze-thaw process. This is most easily done by brin ...

.

Metallic hydrogen

Metallic hydrogen is a phase of hydrogen in which it behaves like an electrical conductor. This phase was predicted in 1935 on theoretical grounds by Eugene Wigner and Hillard Bell Huntington.

At high pressure and temperatures, metallic hydr ...

, a phase obtained at extremely high pressures (in excess of ), is an electrical conductor. It is believed to exist deep within

giant planet

A giant planet, sometimes referred to as a jovian planet (''Jove'' being another name for the Roman god Jupiter (mythology), Jupiter), is a diverse type of planet much larger than Earth. Giant planets are usually primarily composed of low-boiling ...

s like

Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

.

When

ionized

Ionization or ionisation is the process by which an atom or a molecule acquires a negative or positive charge by gaining or losing electrons, often in conjunction with other chemical changes. The resulting electrically charged atom or molecule i ...

, hydrogen becomes a

plasma. This is the form in which hydrogen exists within

star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

s.

Thermal and physical properties

History

18th century

In 1671, Irish scientist

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, Alchemy, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the foun ...

discovered and described the reaction between

iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

filings and dilute

acid

An acid is a molecule or ion capable of either donating a proton (i.e. Hydron, hydrogen cation, H+), known as a Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, Brønsted–Lowry acid, or forming a covalent bond with an electron pair, known as a Lewis ...

s, which results in the production of hydrogen gas.

Boyle did not note that the gas was inflammable, but hydrogen would play a key role in overturning the

phlogiston theory

The phlogiston theory, a superseded scientific theory, postulated the existence of a fire-like element dubbed phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burnin ...

of combustion.

In 1766,

Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "inflammable air". He described the density of inflammable a ...

was the first to recognize hydrogen gas as a discrete substance, by naming the gas from a

metal-acid reaction "inflammable air". He speculated that "inflammable air" was in fact identical to the hypothetical substance "

phlogiston

The phlogiston theory, a superseded scientific theory, postulated the existence of a fire-like element dubbed phlogiston () contained within combustible bodies and released during combustion. The name comes from the Ancient Greek (''burnin ...

"

and further finding in 1781 that the gas produces water when burned. He is usually given credit for the discovery of hydrogen as an element.

In 1783,

Antoine Lavoisier

Antoine-Laurent de Lavoisier ( ; ; 26 August 17438 May 1794), When reduced without charcoal, it gave off an air which supported respiration and combustion in an enhanced way. He concluded that this was just a pure form of common air and that i ...

identified the element that came to be known as hydrogen when he and

Laplace

Pierre-Simon, Marquis de Laplace (; ; 23 March 1749 – 5 March 1827) was a French polymath, a scholar whose work has been instrumental in the fields of physics, astronomy, mathematics, engineering, statistics, and philosophy. He summariz ...

reproduced Cavendish's finding that water is produced when hydrogen is burned.

Lavoisier produced hydrogen for his experiments on mass conservation by treating metallic

iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

with a stream of H

2O through an incandescent iron tube heated in a fire. Anaerobic oxidation of iron by the protons of water at high temperature can be schematically represented by the set of following reactions:

*

*

*

Many metals react similarly with water leading to the production of hydrogen. In some situations, this H

2-producing process is problematic as is the case of zirconium cladding on nuclear fuel rods.

19th century

By 1806 hydrogen was used to fill balloons.

François Isaac de Rivaz

François Isaac de Rivaz (December 19, 1752, in Paris – July 30, 1828, in Sion) was a French-born Swiss inventor and a politician. He invented a hydrogen-powered internal combustion engine with electric ignition and described it in a French pa ...

built the first

de Rivaz engine

The de Rivaz engine was a pioneering reciprocating engine designed and developed from 1804 by the Franco-Swiss inventor Isaac de Rivaz. The engine has a claim to be the world's first internal combustion engine and contained some features of modern ...

, an internal combustion engine powered by a mixture of hydrogen and oxygen in 1806.

Edward Daniel Clarke

Edward Daniel Clarke (5 June 17699 March 1822) was an English clergyman, naturalist, mineralogist, and traveller.

Life

Edward Daniel Clarke was born at Willingdon, Sussex, and educated first at Uckfield School"Anthony Saunders, D.D." in Mark ...

invented the hydrogen gas blowpipe in 1819. The

Döbereiner's lamp

Döbereiner's lamp, also called a "tinderbox" ("Feuerzeug"), is a lighter invented in 1823 by the German chemist Johann Wolfgang Döbereiner. The lighter is based on the Fürstenberger lighter (invented in Basel in 1780; in which hydrogen gas ...

and

limelight

Limelight (also known as Drummond light or calcium light)James R. Smith (2004). ''San Francisco's Lost Landmarks'', Quill Driver Books. is a non-electric type of stage lighting that was once used in theatres and music halls. An intense illum ...

were invented in 1823. Hydrogen was

liquefied for the first time by

James Dewar

Sir James Dewar ( ; 20 September 1842 – 27 March 1923) was a Scottish chemist and physicist. He is best known for his invention of the vacuum flask, which he used in conjunction with research into the liquefaction of gases. He also studie ...

in 1898 by using

regenerative cooling

Regenerative cooling is a method of cooling gases in which compressed gas is cooled by allowing it to expand and thereby take heat from the surroundings. The cooled expanded gas then passes through a heat exchanger where it cools the incoming com ...

and his invention, the

vacuum flask

A vacuum flask (also known as a Dewar flask, Dewar bottle or thermos) is an insulating storage vessel that slows the speed at which its contents change in temperature. It greatly lengthens the time over which its contents remain hotter or coo ...

. He produced

solid hydrogen

Solid hydrogen is the solid state of the element hydrogen. At standard pressure, this is achieved by decreasing the temperature below hydrogen's melting point of . It was collected for the first time by James Dewar in 1899 and published with the ...

the next year.

One of the first

quantum

In physics, a quantum (: quanta) is the minimum amount of any physical entity (physical property) involved in an interaction. The fundamental notion that a property can be "quantized" is referred to as "the hypothesis of quantization". This me ...

effects to be explicitly noticed (but not understood at the time) was

James Clerk Maxwell

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish physicist and mathematician who was responsible for the classical theory of electromagnetic radiation, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism an ...

's observation that the

specific heat capacity

In thermodynamics, the specific heat capacity (symbol ) of a substance is the amount of heat that must be added to one unit of mass of the substance in order to cause an increase of one unit in temperature. It is also referred to as massic heat ...

of unaccountably departs from that of a

diatomic

Diatomic molecules () are molecules composed of only two atoms, of the same or different chemical elements. If a diatomic molecule consists of two atoms of the same element, such as hydrogen () or oxygen (), then it is said to be homonuclear mol ...

gas below room temperature and begins to increasingly resemble that of a monatomic gas at cryogenic temperatures. According to quantum theory, this behavior arises from the spacing of the (quantized) rotational energy levels, which are particularly wide-spaced in because of its low mass. These widely spaced levels inhibit equal partition of heat energy into rotational motion in hydrogen at low temperatures. Diatomic gases composed of heavier atoms do not have such widely spaced levels and do not exhibit the same effect.

20th century

The existence of the

hydride anion was suggested by

Gilbert N. Lewis

Gilbert Newton Lewis (October 23 or October 25, 1875 – March 23, 1946) was an American physical chemist and a dean of the college of chemistry at University of California, Berkeley. Lewis was best known for his discovery of the covalent bon ...

in 1916 for group 1 and 2 salt-like compounds. In 1920, Moers electrolyzed molten

lithium hydride

Lithium hydride is an inorganic compound with the formula Li H. This alkali metal hydride is a colorless solid, although commercial samples are grey. Characteristic of a salt-like (ionic) hydride, it has a high melting point, and it is not solub ...

(LiH), producing a

stoichiometric

Stoichiometry () is the relationships between the masses of reactants and products before, during, and following chemical reactions.

Stoichiometry is based on the law of conservation of mass; the total mass of reactants must equal the total m ...

quantity of hydrogen at the anode.

Because of its simple atomic structure, consisting only of a proton and an electron, the

hydrogen atom

A hydrogen atom is an atom of the chemical element hydrogen. The electrically neutral hydrogen atom contains a single positively charged proton in the nucleus, and a single negatively charged electron bound to the nucleus by the Coulomb for ...

, together with the spectrum of light produced from it or absorbed by it, has been central to the

development of the theory of atomic structure. The energy levels of hydrogen can be calculated fairly accurately using the

Bohr model

In atomic physics, the Bohr model or Rutherford–Bohr model was a model of the atom that incorporated some early quantum concepts. Developed from 1911 to 1918 by Niels Bohr and building on Ernest Rutherford's nuclear Rutherford model, model, i ...

of the atom, in which the electron "orbits" the proton, like how Earth orbits the Sun. However, the electron and proton are held together by electrostatic attraction, while planets and celestial objects are held by

gravity

In physics, gravity (), also known as gravitation or a gravitational interaction, is a fundamental interaction, a mutual attraction between all massive particles. On Earth, gravity takes a slightly different meaning: the observed force b ...

. Due to the discretization of

angular momentum

Angular momentum (sometimes called moment of momentum or rotational momentum) is the rotational analog of Momentum, linear momentum. It is an important physical quantity because it is a Conservation law, conserved quantity – the total ang ...

postulated in early

quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is the fundamental physical Scientific theory, theory that describes the behavior of matter and of light; its unusual characteristics typically occur at and below the scale of atoms. Reprinted, Addison-Wesley, 1989, It is ...

by Bohr, the electron in the Bohr model can only occupy certain allowed distances from the proton, and therefore only certain allowed energies.

Hydrogen's unique position as the only neutral atom for which the

Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation is a partial differential equation that governs the wave function of a non-relativistic quantum-mechanical system. Its discovery was a significant landmark in the development of quantum mechanics. It is named after E ...

can be directly solved, has significantly contributed to the understanding of quantum mechanics through the exploration of its energetics.

Furthermore, study of the corresponding simplicity of the hydrogen molecule and the corresponding cation

brought understanding of the nature of the chemical bond, which followed shortly after the quantum mechanical treatment of the hydrogen atom had been developed in the mid-1920s.

Hydrogen-lifted airship

Because is only 7% the density of air, it was once widely used as a

lifting gas

A lifting gas or lighter-than-air gas is a gas that has a density lower than normal atmospheric gases and rises above them as a result, making it useful in lifting lighter-than-air aircraft. Only certain lighter-than-air gases are suitable as lift ...

in balloons and

airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

s.

The first hydrogen-filled

balloon

A balloon is a flexible membrane bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, or air. For special purposes, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), ...

was invented by

Jacques Charles

Jacques Alexandre César Charles (12 November 1746 – 7 April 1823) was a French people, French inventor, scientist, mathematician, and balloonist.

Charles wrote almost nothing about mathematics, and most of what has been credited to him was due ...

in 1783. Hydrogen provided the lift for the first reliable form of air-travel following the 1852 invention of the first hydrogen-lifted

airship

An airship, dirigible balloon or dirigible is a type of aerostat (lighter-than-air) aircraft that can navigate through the air flying powered aircraft, under its own power. Aerostats use buoyancy from a lifting gas that is less dense than the ...

by

Henri Giffard

Baptiste Jules Henri Jacques Giffard (8 February 182514 April 1882) was a French engineer. In 1852 he invented the steam injector and the powered Giffard dirigible airship.

Career

Giffard was born in Paris in 1825. He invented the injector a ...

. German count

Ferdinand von Zeppelin

Graf, Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (; 8 July 1838 – 8 March 1917) was a General (Germany), German general and later inventor of the Zeppelin rigid airships. His name became synonymous with airships and dominated long-distance flight until the ...

promoted the idea of rigid airships lifted by hydrogen that later were called

Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp. 155� ...

s; the first of which had its maiden flight in 1900.

Regularly scheduled flights started in 1910 and by the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, they had carried 35,000 passengers without a serious incident. Hydrogen-lifted airships in the form of

blimps

A non-rigid airship, commonly called a blimp ( /blɪmp/), is an airship (dirigible) without an internal structural framework or a keel. Unlike semi-rigid and rigid airships (e.g. Zeppelins), blimps rely on the pressure of their lifting gas (usu ...

were used as observation platforms and bombers during the War II, especially on the US Eastern seaboard.

The first non-stop transatlantic crossing was made by the British airship ''

R34'' in 1919 and regular passenger service resumed in the 1920s. Hydrogen was used in the

''Hindenburg'' airship, which caught fire over

New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state located in both the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. Located at the geographic hub of the urban area, heavily urbanized Northeas ...

on 6 May 1937.

The hydrogen that filled the airship was ignited, possibly by static electricity, and burst into flames. Following this

Hindenburg disaster

The ''Hindenburg'' disaster was an airship accident that occurred on May 6, 1937, in Manchester Township, New Jersey, Manchester Township, New Jersey, United States. The LZ 129 Hindenburg, LZ 129 ''Hindenburg'' (; Aircraft registration, Regi ...

, commercial hydrogen airship travel

ceased. Hydrogen is still used, in preference to non-flammable but more expensive

helium

Helium (from ) is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol He and atomic number 2. It is a colorless, odorless, non-toxic, inert gas, inert, monatomic gas and the first in the noble gas group in the periodic table. Its boiling point is ...

, as a lifting gas for

weather balloons.

Deuterium and tritium

Deuterium

Deuterium (hydrogen-2, symbol H or D, also known as heavy hydrogen) is one of two stable isotopes of hydrogen; the other is protium, or hydrogen-1, H. The deuterium nucleus (deuteron) contains one proton and one neutron, whereas the far more c ...

was discovered in December 1931 by

Harold Urey

Harold Clayton Urey ( ; April 29, 1893 – January 5, 1981) was an American physical chemist whose pioneering work on isotopes earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1934 for the discovery of deuterium. He played a significant role in the ...

, and

tritium

Tritium () or hydrogen-3 (symbol T or H) is a rare and radioactive isotope of hydrogen with a half-life of ~12.33 years. The tritium nucleus (t, sometimes called a ''triton'') contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of the ...

was prepared in 1934 by

Ernest Rutherford

Ernest Rutherford, 1st Baron Rutherford of Nelson (30 August 1871 – 19 October 1937) was a New Zealand physicist who was a pioneering researcher in both Atomic physics, atomic and nuclear physics. He has been described as "the father of nu ...

,

Mark Oliphant

Sir Marcus Laurence Elwin Oliphant, (8 October 1901 – 14 July 2000) was an Australian physicist and humanitarian who played an important role in the first experimental demonstration of nuclear fusion and in the development of nuclear weapon ...

, and

Paul Harteck

Paul Karl Maria Harteck (20 July 190222 January 1985) was an Austrian physical chemist. In 1945 under Operation Epsilon in "the big sweep" throughout Germany, Harteck was arrested by the allied British and American Armed Forces for suspicion of ...

.

Heavy water

Heavy water (deuterium oxide, , ) is a form of water (molecule), water in which hydrogen atoms are all deuterium ( or D, also known as ''heavy hydrogen'') rather than the common hydrogen-1 isotope (, also called ''protium'') that makes up most o ...

, which consists of deuterium in the place of regular hydrogen, was discovered by Urey's group in 1932.

Chemistry

Reactions of H2

is relatively unreactive. The thermodynamic basis of this low reactivity is the very strong H–H bond, with a

bond dissociation energy

The bond-dissociation energy (BDE, ''D''0, or ''DH°'') is one measure of the strength of a chemical bond . It can be defined as the standard enthalpy change when is cleaved by homolysis to give fragments A and B, which are usually radical ...

of 435.7 kJ/mol. It does form coordination complexes called

dihydrogen complex

Dihydrogen complexes are coordination complexes containing intact H2 as a ligand. They are a subset of sigma complexes. The prototypical complex is W(CO)3(Tricyclohexylphosphine, PCy3)2(H2). This class of chemical compound, compounds represent in ...

es. These species provide insights into the early steps in the interactions of hydrogen with metal catalysts. According to

neutron diffraction

Neutron diffraction or elastic neutron scattering is the application of neutron scattering to the determination of the atomic and/or magnetic structure of a material. A sample to be examined is placed in a beam of Neutron temperature, thermal or ...

, the metal and two H atoms form a triangle in these complexes. The H-H bond remains intact but is elongated. They are acidic.

Although exotic on Earth, the ion is common in the universe. It is a triangular species, like the aforementioned dihydrogen complexes. It is known as

protonated molecular hydrogen or the trihydrogen cation.

Hydrogen reacts with

chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

to produce

HCl and with

bromine

Bromine is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol Br and atomic number 35. It is a volatile red-brown liquid at room temperature that evaporates readily to form a similarly coloured vapour. Its properties are intermediate between th ...

to produce

HBr by a

chain reaction

A chain reaction is a sequence of reactions where a reactive product or by-product causes additional reactions to take place. In a chain reaction, positive feedback leads to a self-amplifying chain of events.

Chain reactions are one way that sys ...

. The reaction requires initiation. For example in the case of Br

2, the diatomic molecule is broken into atoms, . Propagating reactions consume hydrogen molecules and produce HBr, as well as Br and H atoms:

:

:

Finally the terminating reaction:

:

:.

consumes the remaining atoms.

The addition of H

2 to unsaturated organic compounds, such as

alkene

In organic chemistry, an alkene, or olefin, is a hydrocarbon containing a carbon–carbon double bond. The double bond may be internal or at the terminal position. Terminal alkenes are also known as Alpha-olefin, α-olefins.

The Internationa ...

s and

alkyne

\ce

\ce

Acetylene

\ce

\ce

\ce

Propyne

\ce

\ce

\ce

\ce

1-Butyne

In organic chemistry, an alkyne is an unsaturated hydrocarbon containing at least one carbon—carbon triple bond. The simplest acyclic alkynes with only one triple bond and n ...

s, is called

hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to redox, reduce or Saturated ...

. Even if the reaction is

energetically favorable, it does not take place even at higher temperatures. In the presence of a

catalyst

Catalysis () is the increase in rate of a chemical reaction due to an added substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed by the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recycles quick ...

like finely divided

platinum

Platinum is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a density, dense, malleable, ductility, ductile, highly unreactive, precious metal, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name origina ...

or

nickel

Nickel is a chemical element; it has symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive, but large pieces are slo ...

, the reaction proceeds at room temperature.

Hydrogen-containing compounds

Hydrogen can exist in both +1 and −1

oxidation states

In chemistry, the oxidation state, or oxidation number, is the hypothetical charge of an atom if all of its bonds to other atoms are fully ionic. It describes the degree of oxidation (loss of electrons) of an atom in a chemical compound. Concep ...

, forming compounds through

ionic and

covalent bonding

A covalent bond is a chemical bond that involves the sharing of electrons to form electron pairs between atoms. These electron pairs are known as shared pairs or bonding pairs. The stable balance of attractive and repulsive forces between atoms ...

. It is a part of a wide range of substances, including water,

hydrocarbons

In organic chemistry, a hydrocarbon is an organic compound consisting entirely of hydrogen and carbon. Hydrocarbons are examples of group 14 hydrides. Hydrocarbons are generally colourless and hydrophobic; their odor is usually faint, and may b ...

, and numerous other

organic compounds

Some chemical authorities define an organic compound as a chemical compound that contains a carbon–hydrogen or carbon–carbon bond; others consider an organic compound to be any chemical compound that contains carbon. For example, carbon-co ...

.

The H

+ ion—commonly referred to as a proton due to its single proton and absence of electrons—is central to

acid–base chemistry, although the proton does not move freely. In the

Brønsted–Lowry framework, acids are defined by their ability to donate H

+ ions to bases.

Hydrogen forms a vast variety of compounds with

carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalence, tetravalent—meaning that its atoms are able to form up to four covalent bonds due to its valence shell exhibiting 4 ...

known as hydrocarbons, and an even greater diversity with other elements (

heteroatoms

In chemistry, a heteroatom () is, strictly, any atom that is not carbon or hydrogen.

Organic chemistry

In practice, the term is mainly used more specifically to indicate that non-carbon atoms have replaced carbon in the backbone of the molecular ...

), giving rise to the broad class of organic compounds often associated with living organisms.

Hydrogen compounds with hydrogen in the oxidation state −1 are known as hydrides, which are usually formed between hydrogen and metals. The hydrides can be ionic (aka saline), covalent, nor metallic. With heating, H

2 reacts efficiently with the alkali and alkaline earth metals to give the

ionic hydrides of the formula MH and MH

2, respectively. These salt-like crystalline compounds have high melting points and all react with water to liberate hydrogen. Covalent hydrides are include

boranes

A borane is a compound with the formula although examples include multi-boron derivatives. A large family of boron hydride clusters is also known. In addition to some applications in organic chemistry, the boranes have attracted much attention ...

and polymeric

aluminium hydride.

Transition metals

In chemistry, a transition metal (or transition element) is a chemical element in the d-block of the periodic table (groups 3 to 12), though the elements of group 12 (and less often group 3) are sometimes excluded. The lanthanide and actinid ...

form

metal hydrides

In chemistry, a hydride is formally the anion of hydrogen (H−), a hydrogen ion with two electrons. In modern usage, this is typically only used for ionic bonds, but it is sometimes (and has been more frequently in the past) applied to all co ...

via continuous dissolution of hydrogen into the metal.

[ A well known hydride is ]lithium aluminium hydride

Lithium aluminium hydride, commonly abbreviated to LAH, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula or . It is a white solid, discovered by Finholt, Bond and Schlesinger in 1947. This compound is used as a reducing agent in organic synthe ...

, the anion carries hydridic centers firmly attached to the Al(III). Perhaps the most extensive series of hydrides are the boranes

A borane is a compound with the formula although examples include multi-boron derivatives. A large family of boron hydride clusters is also known. In addition to some applications in organic chemistry, the boranes have attracted much attention ...

, compounds consisting only of boron and hydrogen.ligand

In coordination chemistry, a ligand is an ion or molecule with a functional group that binds to a central metal atom to form a coordination complex. The bonding with the metal generally involves formal donation of one or more of the ligand's el ...

but also as bridging ligand

In coordination chemistry, a bridging ligand is a ligand that connects two or more atoms, usually metal ions. The ligand may be atomic or polyatomic. Virtually all complex organic compounds can serve as bridging ligands, so the term is usually r ...

s. In diborane (), four H's are terminal and two bridge between the two B atoms.

Hydrogen bonding

When bonded to a more electronegative element, particularly fluorine

Fluorine is a chemical element; it has Chemical symbol, symbol F and atomic number 9. It is the lightest halogen and exists at Standard temperature and pressure, standard conditions as pale yellow Diatomic molecule, diatomic gas. Fluorine is extre ...

, oxygen

Oxygen is a chemical element; it has chemical symbol, symbol O and atomic number 8. It is a member of the chalcogen group (periodic table), group in the periodic table, a highly reactivity (chemistry), reactive nonmetal (chemistry), non ...

, or nitrogen

Nitrogen is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol N and atomic number 7. Nitrogen is a Nonmetal (chemistry), nonmetal and the lightest member of pnictogen, group 15 of the periodic table, often called the Pnictogen, pnictogens. ...

, hydrogen can participate in a form of medium-strength noncovalent bonding with another electronegative element with a lone pair like oxygen or nitrogen, a phenomenon called hydrogen bonding that is critical to the stability of many biological molecules. Hydrogen bonding alters molecule structures, viscosity

Viscosity is a measure of a fluid's rate-dependent drag (physics), resistance to a change in shape or to movement of its neighboring portions relative to one another. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of ''thickness''; for e ...

, solubility, as well as melting and boiling points even protein folding dynamics.

Protons and acids

In water, hydrogen bonding plays an important role in reaction thermodynamics. A hydrogen bond can shift over to proton transfer.

Under the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, acids are proton donors, while bases are proton acceptors.

A bare proton, essentially cannot exist in anything other than a vacuum. Otherwise it attaches to other atoms, ions, or molecules. Even species as inert as methane can be protonated. The term 'proton' is used loosely and metaphorically to refer to refer to solvated " without any implication that any single protons exist freely as a species. To avoid the implication of the naked proton in solution, acidic aqueous solutions are sometimes considered to contain the "hydronium ion" () or still more accurately, .

In water, hydrogen bonding plays an important role in reaction thermodynamics. A hydrogen bond can shift over to proton transfer.

Under the Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory, acids are proton donors, while bases are proton acceptors.

A bare proton, essentially cannot exist in anything other than a vacuum. Otherwise it attaches to other atoms, ions, or molecules. Even species as inert as methane can be protonated. The term 'proton' is used loosely and metaphorically to refer to refer to solvated " without any implication that any single protons exist freely as a species. To avoid the implication of the naked proton in solution, acidic aqueous solutions are sometimes considered to contain the "hydronium ion" () or still more accurately, .

Occurrence

Cosmic

Hydrogen, as atomic H, is the most Natural abundance, abundant

Hydrogen, as atomic H, is the most Natural abundance, abundant chemical element

A chemical element is a chemical substance whose atoms all have the same number of protons. The number of protons is called the atomic number of that element. For example, oxygen has an atomic number of 8: each oxygen atom has 8 protons in its ...

in the universe, making up 75% of Baryon, normal matter by mass and >90% by number of atoms. In the early universe, the protons formed in the first second after the Big Bang

The Big Bang is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models based on the Big Bang concept explain a broad range of phenomena, including th ...

; neutral hydrogen atoms formed about 370,000 years later during the Recombination (cosmology), recombination epoch as the universe expanded and plasma had cooled enough for electrons to remain bound to protons.

In astrophysics, neutral hydrogen in the interstellar medium is called ''H I'' and ionized hydrogen is called ''H II''. Radiation from stars ionizes H I to H II, creating Strömgren sphere, spheres of ionized H II around stars. In the chronology of the universe neutral hydrogen dominated until the birth of stars during the era of reionization led to bubbles of ionized hydrogen that grew and merged over 500 million of years.

They are the source of the 21-cm hydrogen line at 1420 MHz that is detected in order to probe primordial hydrogen. The large amount of neutral hydrogen found in the damped Lyman-alpha systems is thought to dominate the Physical cosmology, cosmological baryonic density of the universe up to a redshift of ''z'' = 4.

Hydrogen is found in great abundance in stars and gas giant planets. Molecular clouds of are associated with star formation. Hydrogen plays a vital role in powering star

A star is a luminous spheroid of plasma (physics), plasma held together by Self-gravitation, self-gravity. The List of nearest stars and brown dwarfs, nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night sk ...

s through the proton-proton reaction in lower-mass stars, and through the CNO cycle of nuclear fusion

Nuclear fusion is a nuclear reaction, reaction in which two or more atomic nuclei combine to form a larger nuclei, nuclei/neutrons, neutron by-products. The difference in mass between the reactants and products is manifested as either the rele ...

in case of stars more massive than the Sun

The Sun is the star at the centre of the Solar System. It is a massive, nearly perfect sphere of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core, radiating the energy from its surface mainly as visible light a ...

.

A molecular form called protonated molecular hydrogen () is found in the interstellar medium, where it is generated by ionization of molecular hydrogen from cosmic rays. This ion has also been observed in the Primary atmosphere, upper atmosphere of Jupiter. The ion is long-lived in outer space due to the low temperature and density. is one of the most abundant ions in the universe, and it plays a notable role in the chemistry of the interstellar medium. Neutral triatomic hydrogen can exist only in an excited form and is unstable.

Terrestrial

Hydrogen is the third most abundant element on the Earth's surface,

Production and storage

Industrial routes

Nearly all of the world's current supply of hydrogen gas () is created from fossil fuels.[ Article in press.] Many methods exist for producing H2, but three dominate commercially: steam reforming often coupled to water-gas shift, partial oxidation of hydrocarbons, and water electrolysis.[

]

Steam reforming

Hydrogen is mainly produced by steam reforming, steam methane reforming (SMR), the reaction of water and methane.ammonia production

Ammonia production takes place worldwide, mostly in large-scale manufacturing plants that produce 240 million metric tonnes of ammonia (2023) annually. Based on the annual production in 2023 the major part (~70%) of the production facilities are b ...

, hydrogen is generated from natural gas.

Partial oxidation of hydrocarbons

Other methods for CO and production include partial oxidation of hydrocarbons:

Water electrolysis

Electrolysis of water is a conceptually simple method of producing hydrogen.

:

Commercial electrolyzers use

Electrolysis of water is a conceptually simple method of producing hydrogen.

:

Commercial electrolyzers use nickel

Nickel is a chemical element; it has symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive, but large pieces are slo ...

-based catalysts in strongly alkaline solution. Platinum is a better catalyst but is expensive. The hydrogen created through electrolysis using renewable energy is commonly referred to as "green hydrogen".chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element; it has Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate between ...

also produces high purity hydrogen as a co-product, which is used for a variety of transformations such as hydrogenation

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to redox, reduce or Saturated ...

s.

The electrolysis

In chemistry and manufacturing, electrolysis is a technique that uses Direct current, direct electric current (DC) to drive an otherwise non-spontaneous chemical reaction. Electrolysis is commercially important as a stage in the separation of c ...

process is more expensive than producing hydrogen from methane without carbon capture and storage.

Methane pyrolysis

Hydrogen can be produced by pyrolysis of natural gas (methane), producing hydrogen gas and solid carbon with the aid a catalyst and 74 kJ/mol input heat:

: (ΔH° = 74 kJ/mol)

The carbon may be sold as a manufacturing feedstock or fuel, or landfilled.

This route could have a lower carbon footprint than existing hydrogen production processes, but mechanisms for removing the carbon and preventing it from reacting with the catalyst remain obstacles for industrial scale use.

Thermochemical

Water splitting is the process by which water is decomposed into its components. Relevant to the biological scenario is this simple equation:

:

The reaction occurs in the Light-dependent reactions, light reactions in all photosynthetic organisms. A few organisms, including the alga ''Chlamydomonas reinhardtii'' and cyanobacteria, have evolved a second step in the dark reactions in which protons and electrons are reduced to form gas by specialized hydrogenases in the chloroplast.

Efforts have been undertaken to genetically modify cyanobacterial hydrogenases to more efficiently generate gas even in the presence of oxygen. Efforts have also been undertaken with genetically modified Biological hydrogen production (Algae), alga in a bioreactor.

Relevant to the thermal water-splitting scenario is this simple equation:

:

More than 200 thermochemical cycles can be used for water splitting. Many of these cycles such as the iron oxide cycle, cerium(IV) oxide–cerium(III) oxide cycle, zinc zinc-oxide cycle, sulfur-iodine cycle, copper-chlorine cycle and hybrid sulfur cycle have been evaluated for their commercial potential to produce hydrogen and oxygen from water and heat without using electricity. A number of labs (including in France, Germany, Greece, Japan, and the United States) are developing thermochemical methods to produce hydrogen from solar energy and water.

Natural routes

Biohydrogen

is produced by enzymes called hydrogenases. This process allows the host organism to use fermentation as a source of energy. These same enzymes also can oxidize H2, such that the host organisms can subsist by reducing oxidized substrates using electrons extracted from H2.

The hydrogenase enzyme feature iron

Iron is a chemical element; it has symbol Fe () and atomic number 26. It is a metal that belongs to the first transition series and group 8 of the periodic table. It is, by mass, the most common element on Earth, forming much of Earth's o ...

or nickel

Nickel is a chemical element; it has symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive, but large pieces are slo ...