HMS Dorsetshire (1929) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

HMS ''Dorsetshire'' (

''Dorsetshire'' was at maximum

''Dorsetshire'' was at maximum

At the start of the Second World War in September 1939, ''Dorsetshire'' was still on the China Station. In October, ''Dorsetshire''—with other Royal Navy ships—was sent to South American waters in pursuit of the German

At the start of the Second World War in September 1939, ''Dorsetshire'' was still on the China Station. In October, ''Dorsetshire''—with other Royal Navy ships—was sent to South American waters in pursuit of the German

By May 1941, ''Dorsetshire'' had been assigned to

By May 1941, ''Dorsetshire'' had been assigned to

In late August, ''Dorsetshire'' participated in the search for the heavy cruiser . ''Dorsetshire'', ''Eagle'' and the light cruiser left Freetown on 29 August, though they were unable to locate the German raider. On 4 November, ''Dorsetshire'' and the

In late August, ''Dorsetshire'' participated in the search for the heavy cruiser . ''Dorsetshire'', ''Eagle'' and the light cruiser left Freetown on 29 August, though they were unable to locate the German raider. On 4 November, ''Dorsetshire'' and the

Official History map of the loss of Dorsetshire

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dorsetshire (40) Kent-class cruisers County-class cruisers of the Royal Navy Ships built in Portsmouth 1929 ships World War II cruisers of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Indian Ocean Maritime incidents in April 1942 Cruisers sunk by aircraft Ships sunk by Japanese aircraft Naval magazine explosions

pennant number

In the Royal Navy and other navies of Europe and the Commonwealth of Nations, ships are identified by pennant number (an internationalisation of ''pendant number'', which it was called before 1948). Historically, naval ships flew a flag that iden ...

40) was a heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

of the British Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the naval warfare force of the United Kingdom. It is a component of His Majesty's Naval Service, and its officers hold their commissions from the King of the United Kingdom, King. Although warships were used by Kingdom ...

, named after the English county, now usually known as Dorset

Dorset ( ; Archaism, archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a Ceremonial counties of England, ceremonial county in South West England. It is bordered by Somerset to the north-west, Wiltshire to the north and the north-east, Hampshire to the east, t ...

. The ship was a member of the ''Norfolk'' sub-class, of which was the only other unit; the County class comprised a further eleven ships in two other sub-classes. ''Dorsetshire'' was built at the Portsmouth Dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is loc ...

; her keel was laid in September 1927, she was launched in January 1929, and was completed in September 1930. ''Dorsetshire'' was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

of eight guns, and had a top speed of .

''Dorsetshire'' served initially in the Atlantic Fleet in the early 1930s, before moving to become the flagship of the Commander-in-Chief, Africa in 1933, and then to the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China, was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 1 ...

in late 1935. She remained there until the outbreak of the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

in September 1939, when she was transferred to the South Atlantic. There, she reinforced the search for the German heavy cruiser . In late May 1941, ''Dorsetshire'' took part in the final engagement with the battleship ''Bismarck'', which ended when ''Dorsetshire'' was ordered to close and torpedo

A modern torpedo is an underwater ranged weapon launched above or below the water surface, self-propelled towards a target, with an explosive warhead designed to detonate either on contact with or in proximity to the target. Historically, such ...

the crippled German battleship. She joined searches for the heavy cruiser in August and the auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

in November.

In March 1942, ''Dorsetshire'' was transferred to the Eastern Fleet

Eastern or Easterns may refer to:

Transportation

Airlines

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 192 ...

to support British forces in the recently opened Pacific Theatre of the war. At the end of the month, the Japanese fast carrier task force—the ''Kido Butai

The , also known as the ''Kidō Butai'' ("Mobile Force"), was a combined carrier battle group comprising most of the aircraft carriers and carrier air groups of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) during the first eight months of the Pacific War.

...

''—launched the Indian Ocean raid. On 5 April, Japanese aircraft spotted ''Dorsetshire'' and her sister while en route to Colombo

Colombo, ( ; , ; , ), is the executive and judicial capital and largest city of Sri Lanka by population. The Colombo metropolitan area is estimated to have a population of 5.6 million, and 752,993 within the municipal limits. It is the ...

; a force of dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s then attacked the two ships and sank them. More than 1,100 men were rescued the next day, out of a combined crew of over 1,500.

Description

''Dorsetshire'' was at maximum

''Dorsetshire'' was at maximum long overall

Length overall (LOA, o/a, o.a. or oa) is the maximum length of a vessel's hull measured parallel to the waterline. This length is important while docking the ship. It is the most commonly used way of expressing the size of a ship, and is also u ...

, and had a beam

Beam may refer to:

Streams of particles or energy

*Light beam, or beam of light, a directional projection of light energy

**Laser beam

*Radio beam

*Particle beam, a stream of charged or neutral particles

**Charged particle beam, a spatially lo ...

of and a draught of . She displaced at standard displacement, in compliance with the tonnage restriction of the Washington Naval Treaty

The Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty, was signed during 1922 among the major Allies of World War I, Allies of World War I, which agreed to prevent an arms race by limiting Navy, naval construction. It was negotiated at ...

, and up to at full load

The displacement or displacement tonnage of a ship is its weight. As the term indicates, it is measured indirectly, using Archimedes' principle, by first calculating the volume of water displaced by the ship, then converting that value into weig ...

. ''Dorsetshire'' was propelled by four Parsons steam turbine

A steam turbine or steam turbine engine is a machine or heat engine that extracts thermal energy from pressurized steam and uses it to do mechanical work utilising a rotating output shaft. Its modern manifestation was invented by Sir Charles Par ...

s that drove four screw propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

s. Steam was provided by eight oil-fired 3-drum water-tube boiler

A high pressure watertube boiler (also spelled water-tube and water tube) is a type of boiler in which water circulates in tubes heated externally by fire. Fuel is burned inside the furnace, creating hot gas which boils water in the steam-generat ...

s. The turbines were rated at and produced a top speed of . The ship had a capacity of of fuel oil as built, which provided a cruising radius of at a speed of . She had a crew of 710 officers and enlisted men.

''Dorsetshire'' was armed with a main battery

A main battery is the primary weapon or group of weapons around which a warship is designed. As such, a main battery was historically a naval gun or group of guns used in volleys, as in the broadsides of cannon on a ship of the line. Later, th ...

of eight BL Mk VIII 50-cal. guns in four twin turrets

Turret may refer to:

* Turret (architecture), a small tower that projects above the wall of a building

* Gun turret, a mechanism of a projectile-firing weapon

* Objective turret, an indexable holder of multiple lenses in an optical microscope

* ...

, in two superfiring pairs forward and aft. As built, the cruiser had a secondary battery

A rechargeable battery, storage battery, or secondary cell (formally a type of Accumulator (energy), energy accumulator), is a type of electrical battery which can be charged, discharged into a load, and recharged many times, as opposed to a ...

that included four dual-purpose gun

A dual-purpose gun is a naval artillery mounting designed to engage both surface and air targets.

Description

Second World War-era capital ships had four classes of artillery: the heavy main battery, intended to engage opposing battleships and ...

s (DP) in single mounts. She also carried four QF 2-pounder anti-aircraft guns, also in single mounts. Her armament was rounded out by eight torpedo tube

A torpedo tube is a cylindrical device for launching torpedoes.

There are two main types of torpedo tube: underwater tubes fitted to submarines and some surface ships, and deck-mounted units (also referred to as torpedo launchers) installed aboa ...

s mounted in two quadruple launchers.

Unlike most heavy cruisers, the County-class cruisers dispensed with traditional belt armour

Belt armor is a layer of heavy metal armor plated onto or within the outer hulls of warships, typically on battleships, battlecruisers and cruisers, and aircraft carriers.

The belt armor is designed to prevent projectiles from penetrating to ...

and used side plating to protect the hulls against shell fragments only. The ammunition magazines

A magazine is a periodical literature, periodical publication, print or digital, produced on a regular schedule, that contains any of a variety of subject-oriented textual and visual content (media), content forms. Magazines are generally fin ...

received of armour plate on the sides. The gun turrets and their supporting barbette

Barbettes are several types of gun emplacement in terrestrial fortifications or on naval ships.

In recent naval usage, a barbette is a protective circular armour support for a heavy gun turret. This evolved from earlier forms of gun protection ...

s also received only 1 in splinter protection.

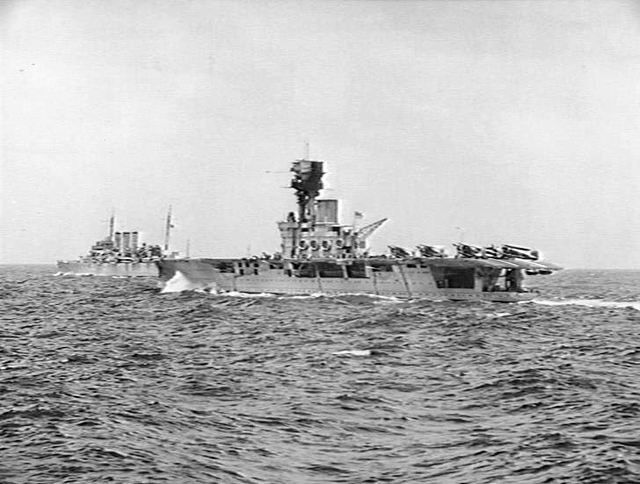

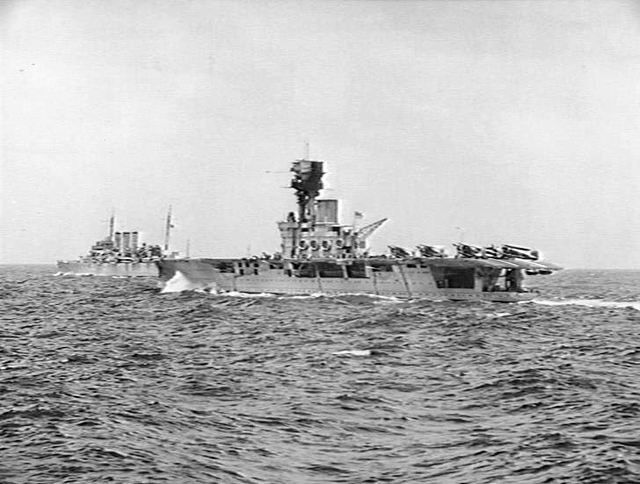

In 1931, ''Dorsetshire'' began to carry a seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

; a catapult

A catapult is a ballistics, ballistic device used to launch a projectile at a great distance without the aid of gunpowder or other propellants – particularly various types of ancient and medieval siege engines. A catapult uses the sudden rel ...

was installed the following year to allow her to launch the aircraft while underway. In 1937, her secondary battery was overhauled. Eight QF 4-inch Mk XVI DP guns in twin turrets replaced the single mounts, and the single 2-pounders were replaced with eight twin-mounts. During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

, her anti-aircraft battery was strengthened by the addition of nine guns.

Service history

Pre-war

''Dorsetshire'' was laid down at thePortsmouth Dockyard

His Majesty's Naval Base, Portsmouth (HMNB Portsmouth) is one of three operating bases in the United Kingdom for the Royal Navy (the others being HMNB Clyde and HMNB Devonport). Portsmouth Naval Base is part of the city of Portsmouth; it is loc ...

on 21 September 1927 and was launched on 21 January 1929. After completing fitting-out

Fitting out, or outfitting, is the process in shipbuilding that follows the float-out/launching of a vessel and precedes sea trials. It is the period when all the remaining construction of the ship is completed and readied for delivery to her o ...

work on 30 September 1930 she was commissioned into the Royal Navy. Upon commissioning, ''Dorsetshire'' became the flagship

A flagship is a vessel used by the commanding officer of a group of navy, naval ships, characteristically a flag officer entitled by custom to fly a distinguishing flag. Used more loosely, it is the lead ship in a fleet of vessels, typically ...

of the 2nd Cruiser Squadron. In 1931, she was part of the Atlantic Fleet during the Invergordon Mutiny. During the incident, some of her men initially refused to assemble for duty but after an hour and a half, the ship's officers had restored order and no further unrest troubled ''Dorsetshire'' during the mutiny. From 1933–1935, she served as the flagship for the Commander-in-Chief, Africa; she was replaced by . By September 1935, ''Dorsetshire'' was assigned to the China Station

The Commander-in-Chief, China, was the admiral in command of what was usually known as the China Station, at once both a British Royal Navy naval formation and its admiral in command. It was created in 1865 and deactivated in 1941.

From 1831 to 1 ...

. From 1–4 February 1937, ''Dorsetshire'', the aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

and the cruiser participated in an exercise to test the defences of Singapore against a hypothetical Japanese attack.

Second World War

At the start of the Second World War in September 1939, ''Dorsetshire'' was still on the China Station. In October, ''Dorsetshire''—with other Royal Navy ships—was sent to South American waters in pursuit of the German

At the start of the Second World War in September 1939, ''Dorsetshire'' was still on the China Station. In October, ''Dorsetshire''—with other Royal Navy ships—was sent to South American waters in pursuit of the German heavy cruiser

A heavy cruiser was a type of cruiser, a naval warship designed for long range and high speed, armed generally with naval guns of roughly 203 mm (8 inches) in calibre, whose design parameters were dictated by the Washington Naval Treat ...

, which was attacking British merchant traffic in the area. ''Dorsetshire'' was assigned with her sister ship

A sister ship is a ship of the same Ship class, class or of virtually identical design to another ship. Such vessels share a nearly identical hull and superstructure layout, similar size, and roughly comparable features and equipment. They o ...

and the aircraft carrier . ''Dorsetshire'' had just arrived in Simonstown, South Africa, from Colombo on 9 December, with orders to proceed to Tristan da Cunha

Tristan da Cunha (), colloquially Tristan, is a remote group of volcano, volcanic islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is one of three constituent parts of the British Overseas Territories, British Overseas Territory of Saint Helena, Ascensi ...

and then to Port Stanley

Stanley (also known as Port Stanley) is the capital city of the Falkland Islands. It is located on the island of East Falkland, on a north-facing slope in one of the wettest parts of the islands. At the 2016 census, the city had a population o ...

in the Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; ), commonly referred to as The Falklands, is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and from Cape Dub ...

to relieve . After departing Simonstown, she received the order to join the hunt for ''Admiral Graf Spee''. She left South Africa on 13 December in company with the cruiser and was in transit on 17 December when the Germans scuttled

Scuttling is the act of deliberately sinking a ship by allowing water to flow into the hull, typically by its crew opening holes in its hull.

Scuttling may be performed to dispose of an abandoned, old, or captured vessel; to prevent the vesse ...

''Admiral Graf Spee'' following the Battle of the River Plate.

''Exeter'' had been badly damaged in the battle with ''Admiral Graf Spee'', and ''Dorsetshire'' escorted her back to Britain in January 1940, before returning to South American waters to search for German supply ships. On 11 February, her reconnaissance aircraft spotted the German supply freighter ''Wakama'' off the coast of Brazil, which was promptly scuttled by her crew. ''Dorsetshire'' arrived on the scene shortly thereafter, picked up ten officers and thirty-five crewmen and sank ''Wakama'' to prevent her from being a navigational hazard. The following month, the President of Panama, Augusto Samuel Boyd

Augusto Samuel Boyd Briceño (1 August 1879 – 17 June 1957 www.encaribe.org) was a politician from Panama.

Background

He was elected as the first presidential designate by the National Assembly for the terms 1936–1938 and 1938–194 ...

, sent a formal complaint to the British government protesting against ''Dorsetshire''s violation of the Pan-American Security Zone

During the early years of World War II before the United States became a formal belligerent, President Franklin D. Roosevelt declared a region of the Atlantic, adjacent to the Americas, as the Pan-American Security Zone. Within this zone, United St ...

in the ''Wakama'' incident.

In May, ''Dorsetshire'' underwent a short refit in Simonstown, before returning to Britain for a more thorough overhaul. On 23 June, she set out from Freetown to watch the French battleship

A battleship is a large, heavily naval armour, armored warship with a main battery consisting of large naval gun, guns, designed to serve as a capital ship. From their advent in the late 1880s, battleships were among the largest and most form ...

, which left Dakar

Dakar ( ; ; ) is the capital city, capital and List of cities in Senegal, largest city of Senegal. The Departments of Senegal, department of Dakar has a population of 1,278,469, and the population of the Dakar metropolitan area was at 4.0 mill ...

for Casablanca

Casablanca (, ) is the largest city in Morocco and the country's economic and business centre. Located on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Chaouia (Morocco), Chaouia plain in the central-western part of Morocco, the city has a populatio ...

two days later. While ''en route'', ''Dorsetshire'' rendezvoused with the aircraft carrier ''Hermes'' off Dakar. ''Richelieu'' was ordered to return to Dakar by Admiral François Darlan

Jean Louis Xavier François Darlan (; 7 August 1881 – 24 December 1942) was a French admiral and political figure. Born in Nérac, Darlan graduated from the ''École navale'' in 1902 and quickly advanced through the ranks following his servic ...

later that day and she arrived on 27 June. ''Dorsetshire'' continued to monitor the French Navy off Dakar and on 3 July, the French submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited underwater capability.) The term "submarine" is also sometimes used historically or infor ...

s and attempted to intercept her. ''Dorsetshire'' was able to evade their attacks through high-speed manoeuvres. On 5 July, ''Hermes'' and the Australian cruiser joined her there. On 7 July, the squadron was ordered to issue an ultimatum to the French fleet, to either surrender and be interned under British control or to scuttle their ships; the French refused, so a fast sloop was sent in to drop depth charge

A depth charge is an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) weapon designed to destroy submarine

A submarine (often shortened to sub) is a watercraft capable of independent operation underwater. (It differs from a submersible, which has more limited ...

s under the stern of ''Richelieu'' to disable her screws.

On 4 September, she was dry-docked at Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

and on the 20th she arrived back in Simonstown. She sailed for Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone, officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered to the southeast by Liberia and by Guinea to the north. Sierra Leone's land area is . It has a tropical climate and envi ...

the next day. Operating in the Indian Ocean, on 18 November she bombarded Zante in Italian Somaliland

Italian Somaliland (; ; ) was a protectorate and later colony of the Kingdom of Italy in present-day Somalia, which was ruled in the 19th century by the Sultanate of Hobyo and the Majeerteen Sultanate in the north, and by the Hiraab Imamate and ...

. On 18 December she departed to join the search for the heavy cruiser , which had recently sunk the British refrigerator ship ''Duquesa'' in the South Atlantic

The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, with an area of about . It covers approximately 17% of Earth's surface and about 24% of its water surface area. During the Age of Discovery, it was known for ...

. The British were unsuccessful in their search and ''Admiral Scheer'' remained at large.

''Bismarck''

By May 1941, ''Dorsetshire'' had been assigned to

By May 1941, ''Dorsetshire'' had been assigned to Force H

Force H was a British naval formation during the Second World War. It was formed in late-June 1940, to replace French naval power in the western Mediterranean removed by the French armistice with Nazi Germany. The force occupied an odd place ...

, along with the aircraft carrier , the battlecruiser

The battlecruiser (also written as battle cruiser or battle-cruiser) was a type of capital ship of the first half of the 20th century. These were similar in displacement, armament and cost to battleships, but differed in form and balance of att ...

, and the light cruiser

A light cruiser is a type of small or medium-sized warship. The term is a shortening of the phrase "light armored cruiser", describing a small ship that carried armor in the same way as an armored cruiser: a protective belt and deck. Prior to thi ...

. ''Dorsetshire'' was at that time commanded by Captain Benjamin Martin. Late in the month, the German battleship and heavy cruiser broke out into the North Atlantic to attack convoys sailing for Britain, and ''Dorsetshire'' was one of the ships deployed to hunt the German raiders. ''Dorsetshire'' had been escorting convoy SL74 from Sierra Leone to the UK on 26 May, when she received the order to leave the convoy and join the search for ''Bismarck''; she was some south of ''Bismarck''s location. ''Dorsetshire'' steamed at top speed, though heavy seas later in the night forced her to reduce to and later to . By 08:33, ''Dorsetshire'' encountered the destroyer

In naval terminology, a destroyer is a fast, maneuverable, long-endurance warship intended to escort

larger vessels in a fleet, convoy, or carrier battle group and defend them against a wide range of general threats. They were conceived i ...

, which had been engaging ''Bismarck'' throughout the night. The German battleship's gun flashes could be seen, only away, by 08:50.

Shortly thereafter, ''Dorsetshire'' took part in ''Bismarck''s last battle; after the battleships and neutralised ''Bismarck''s main battery early in the engagement, ''Dorsetshire'' and other warships—including her sister —closed in to join the attack. ''Dorsetshire'' opened fire at a range of , but poor visibility forced her to check her fire for lengthy periods. In the course of the engagement, she fired 254 shells from her main battery. In the final moments of the battle, she was ordered to move closer and torpedo ''Bismarck'' and fired three torpedoes, two of which hit the crippled battleship. The Germans had by this time detonated scuttling charges, which with the damage inflicted by the British, caused ''Bismarck'' to rapidly sink at 10:40.

''Dorsetshire'' and the destroyer then moved in to pick up survivors. Martin had ropes lowered down the sides of the ship so the men in the water could climb aboard. A reported U-boat

U-boats are Submarine#Military, naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the World War I, First and Second World Wars. The term is an Anglicization#Loanwords, anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the G ...

sighting forced the two ships to break off the rescue effort. Historians Holger Herwig

Dr. Holger H. Herwig (born 1941) is a German-born Canadian historian and professor. He is the author of more than a dozen books, including the award-winning, ''The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918'' and ''The Origins of World ...

and David Bercuson

David Jay Bercuson (born August 31, 1945) is a Canadian labour, military, and political historian.

Career

Born on 31 August 1945 in Montreal, Quebec, he attended Sir George Williams University, graduated there in 1965 with a Bachelor of Arts ...

state that only 110 men were rescued: 85 aboard ''Dorsetshire'' and 25 aboard ''Maori''. Historian Angus Konstam

Angus Konstam (born 2 January 1960) is a Scottish writer of popular history. Born in Aberdeen, Scotland and raised on the Orkney Islands, he has written more than a hundred books on maritime history, naval history, historical atlases, with a ...

, however, writes that his research indicated a total of 116 saved, 86 on ''Dorsetshire'' (one of whom died), 25 on ''Maori'', 3 rescued by and a further 2 picked up by the German weather ship .

''Rodney'', ''King George V'' and the destroyers , and ''Cossack'' had meanwhile begun to steam north-west to return to Scapa Flow. After abandoning the rescue effort, ''Dorsetshire'' and ''Maori'' caught up with the rest of the fleet shortly after 12:00. Late that night, as the fleet steamed off Britain, ''Dorsetshire'' was detached to stop in the Tyne Tyne may refer to:

__NOTOC__ Geography

*River Tyne, England

*Port of Tyne, the commercial docks in and around the River Tyne in Tyne and Wear, England

* River Tyne, Scotland

*River Tyne, a tributary of the South Esk River, Tasmania, Australia

Peopl ...

. She had suffered no casualties in the battle with ''Bismarck''.

Deployment to South Africa and the Indian Ocean

In late August, ''Dorsetshire'' participated in the search for the heavy cruiser . ''Dorsetshire'', ''Eagle'' and the light cruiser left Freetown on 29 August, though they were unable to locate the German raider. On 4 November, ''Dorsetshire'' and the

In late August, ''Dorsetshire'' participated in the search for the heavy cruiser . ''Dorsetshire'', ''Eagle'' and the light cruiser left Freetown on 29 August, though they were unable to locate the German raider. On 4 November, ''Dorsetshire'' and the auxiliary cruiser

An armed merchantman is a merchant ship equipped with guns, usually for defensive purposes, either by design or after the fact. In the days of sail, piracy and privateers, many merchantmen would be routinely armed, especially those engaging in lo ...

, were sent to investigate reports of a German surface raider in the South Atlantic but neither ship found anything. In November–December, WS-24, a convoy of 10 troop transport ships, steamed out from Halifax, Canada

Halifax is the capital and most populous municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the most populous municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of 2024, it is estimated that the population of the Halifax CMA was 530,167, with 348,634 ...

en route to Basra

Basra () is a port city in Iraq, southern Iraq. It is the capital of the eponymous Basra Governorate, as well as the List of largest cities of Iraq, third largest city in Iraq overall, behind Baghdad and Mosul. Located near the Iran–Iraq bor ...

, Iraq. After arriving in Cape Town on 9 December, ''Dorsetshire'' took over the escort duties and the convoy was diverted to Bombay, where it arrived on 24 December.

''Dorsetshire'' was deployed in November, to join the search for the German commerce raider , that had been attacking Allied shipping off the coast of Africa. Admiral Algernon Willis

Admiral of the Fleet Sir Algernon Usborne Willis (17 May 1889 – 12 April 1976) was a Royal Navy officer. He served in the First World War and saw action at the Battle of Jutland in May 1916. He also served in the Second World War as Commander ...

formed Task Force 3, with ''Dorsetshire'' and to patrol likely refuelling locations for ''Atlantis''. On 1 December, ''Dorsetshire'' intercepted the German supply ship ''Python'', based on Ultra

Ultra may refer to:

Science and technology

* Ultra (cryptography), the codename for cryptographic intelligence obtained from signal traffic in World War II

* Adobe Ultra, a vector-keying application

* Sun Ultra series, a brand of computer work ...

intelligence. The German ship was refuelling a pair of U-boats— and —in the South Atlantic. The U-boats dived while ''Python'' tried to flee. ''UA'' fired five torpedoes at ''Dorsetshire'' but all missed her due to her evasive manoeuvres. ''Dorsetshire'' fired a salvo to stop ''Python'' and the latter's crew abandoned the ship, after detonating scuttling charges. ''Dorsetshire'' left the Germans in their boats, since the U-boats still presented too much of a threat for the British to pick up the Germans.

Loss

In 1942, ''Dorsetshire'', under the command ofAugustus Agar

Augustus Willington Shelton Agar, (4 January 1890 – 30 December 1968) was a Royal Navy officer in both the First and the Second World Wars. He was a recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest award for gallantry in the face of the enemy t ...

, was assigned to the Eastern Fleet

Eastern or Easterns may refer to:

Transportation

Airlines

*China Eastern Airlines, a current Chinese airline based in Shanghai

* Eastern Air, former name of Zambia Skyways

*Eastern Air Lines, a defunct American airline that operated from 192 ...

in the Indian Ocean. In March, ''Dorsetshire'' was assigned to Force A, which was commanded by Admiral James Somerville

Admiral of the Fleet Sir James Fownes Somerville (17 July 1882 – 19 March 1949) was a Royal Navy admiral of the fleet. He served in the First World War as fleet wireless officer for the Mediterranean Fleet where he was involved in providing ...

, with the battleship and the carriers and . Somerville received reports of an impending Japanese attack in the Indian Ocean—the Indian Ocean raid—and so he put his fleet to sea on 31 March. Having not encountered any hostile forces by 4 April, he withdrew to refuel. ''Dorsetshire'' and her sister ship ''Cornwall'' were sent to Colombo to replenish their fuel.

The next day, she and ''Cornwall'' were spotted by reconnaissance aircraft from the heavy cruiser . The two British cruisers were attacked by a force of 53 Aichi D3A

The Aichi D3A (Navy designation "Type 99 Carrier Bomber"; World War II Allied names for Japanese aircraft, Allied reporting name "Val") is a World War II carrier-borne dive bomber. It was the primary dive bomber of the Imperial Japanese Na ...

2 "Val" dive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s southwest of Ceylon

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

. In the span of about eight minutes, ''Dorsetshire'' was hit by ten and bombs and several near misses; she sank stern first at about 13:50. One of the bombs detonated an ammunition magazine and contributed to her rapid sinking. ''Cornwall'' was hit eight times and sank bow first about ten minutes later. Between the two ships, 1,122 men out of a total of 1,546 were picked up by the cruiser and the destroyers and the next day.

Footnotes

References

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* * *External links

Official History map of the loss of Dorsetshire

{{DEFAULTSORT:Dorsetshire (40) Kent-class cruisers County-class cruisers of the Royal Navy Ships built in Portsmouth 1929 ships World War II cruisers of the United Kingdom World War II shipwrecks in the Indian Ocean Maritime incidents in April 1942 Cruisers sunk by aircraft Ships sunk by Japanese aircraft Naval magazine explosions