A fixed-wing aircraft is a heavier-than-air

aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

, such as an

airplane

An airplane (American English), or aeroplane (Commonwealth English), informally plane, is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, Propeller (aircraft), propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a vari ...

, which is capable of

flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

using

aerodynamic lift

When a fluid flows around an object, the fluid exerts a force on the object. Lift is the component of this force that is perpendicular to the oncoming flow direction. It contrasts with the drag force, which is the component of the force paral ...

. Fixed-wing aircraft are distinct from

rotary-wing aircraft

A rotary-wing aircraft, rotorwing aircraft or rotorcraft is a heavier-than-air aircraft with rotary wings that spin around a vertical mast to generate lift. Part 1 (Definitions and Abbreviations) of Subchapter A of Chapter I of Title 14 of the ...

(in which a

rotor

ROTOR was an elaborate air defence radar system built by the British Government in the early 1950s to counter possible attack by Soviet bombers. To get it operational as quickly as possible, it was initially made up primarily of WWII-era syst ...

mounted on a spinning shaft generates lift), and

ornithopter

An ornithopter (from Greek language, Greek ''ornis, ornith-'' 'bird' and ''pteron'' 'wing') is an aircraft that flies by flapping its wings. Designers sought to imitate the flapping-wing flight of birds, bats, and insects. Though machines may dif ...

s (in which the wings oscillate to generate lift). The wings of a fixed-wing aircraft are not necessarily rigid; kites,

hang glider

Hang gliding is an air sport or recreational activity in which a pilot flies a light, non-motorised, fixed-wing heavier-than-air aircraft called a hang glider. Most modern hang gliders are made of an aluminium alloy or composite frame covered ...

s,

variable-sweep wing

A variable-sweep wing, colloquially known as a "swing wing", is an airplane wing, or set of wings, that may be modified during flight, swept back and then returned to its previous straight position. Because it allows the aircraft's shape to ...

aircraft, and airplanes that use

wing morphing are all classified as fixed wing.

Gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

fixed-wing aircraft, including free-flying

gliders and tethered

kite

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. Kites often have ...

s, can use moving air to gain altitude.

Powered fixed-wing aircraft (airplanes) that gain forward

thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

from an

engine

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power ge ...

include

powered paraglider

Powered paragliding, also known as paramotoring or PPG, is a form of ultralight aviation where the pilot wears a back-pack motor (a paramotor) which provides enough thrust to take off using a paraglider. It can be launched in still air, and ...

s,

powered hang gliders and

ground effect vehicle

A ground-effect vehicle (GEV), also called a wing-in-ground-effect (WIGE or WIG), ground-effect craft/machine (GEM), wingship, flarecraft, surface effect vehicle or ekranoplan (), is a vehicle that is able to move over the surface by gaining su ...

s. Most fixed-wing aircraft are operated by a

pilot

An aircraft pilot or aviator is a person who controls the flight of an aircraft by operating its Aircraft flight control system, directional flight controls. Some other aircrew, aircrew members, such as navigators or flight engineers, are al ...

, but some are

unmanned or controlled

remotely or are completely autonomous (no remote pilot).

History

Kites

Kites were used approximately 2,800 years ago in China, where kite building materials were available. Leaf kites may have been flown earlier in what is now

Sulawesi

Sulawesi ( ), also known as Celebes ( ), is an island in Indonesia. One of the four Greater Sunda Islands, and the List of islands by area, world's 11th-largest island, it is situated east of Borneo, west of the Maluku Islands, and south of Min ...

, based on their interpretation of cave paintings on nearby

Muna Island. By at least 549 AD paper kites were flying, as recorded that year, a paper kite was used as a message for a rescue mission.

[Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, 127.] Ancient and medieval Chinese sources report kites used for measuring distances, testing the wind, lifting men, signaling, and communication for military operations.

Kite stories were brought to Europe by

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (; ; ; 8 January 1324) was a Republic of Venice, Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known a ...

towards the end of the 13th century, and kites were brought back by sailors from Japan and

Malaysia

Malaysia is a country in Southeast Asia. Featuring the Tanjung Piai, southernmost point of continental Eurasia, it is a federation, federal constitutional monarchy consisting of States and federal territories of Malaysia, 13 states and thre ...

in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Although initially regarded as curiosities, by the 18th and 19th centuries kites were used for scientific research.

Gliders and powered devices

Around

400 BC in Greece,

Archytas

Archytas (; ; 435/410–360/350 BC) was an Ancient Greek mathematician, music theorist, statesman, and strategist from the ancient city of Taras (Tarentum) in Southern Italy. He was a scientist and philosopher affiliated with the Pythagorean ...

was reputed to have designed and built the first self-propelled flying device, shaped like a bird and propelled by a jet of what was probably steam, said to have flown some . This machine may have been suspended during its flight.

One of the earliest attempts with

gliders was by 11th-century monk

Eilmer of Malmesbury

Eilmer of Malmesbury (also known as Oliver due to a scribe's miscopying, or Elmer, or Æthelmær) was an 11th-century English Benedictine monk best known for his early attempt at a gliding flight using wings.

Life

Eilmer was a monk of Malme ...

, which failed. A 17th-century account states that 9th-century poet

Abbas Ibn Firnas

Abū al-Qāsim ʿAbbās ibn Firnās ibn Wardūs al-Tākurnī (; c. 809/810 – 887 CE), known as ʿAbbās ibn Firnās () was an Andalusi polymath: Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (Spring, 1961). "Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A C ...

made a similar attempt, though no earlier sources record this event.

In 1799,

Sir George Cayley

Sir George Cayley, 6th Baronet (27 December 1773 – 15 December 1857) was an English engineer, inventor, and aviator. He is one of the most important people in the history of aeronautics. Many consider him to be the first true scientific ae ...

laid out the concept of the modern airplane as a fixed-wing machine with systems for lift, propulsion, and control. Cayley was building and flying models of fixed-wing aircraft as early as 1803, and built a successful passenger-carrying

glider in 1853. In 1856, Frenchman

Jean-Marie Le Bris

Jean Marie Le Bris (25 March 1817, Concarneau – 17 February 1872, Douarnenez) was a French aviator, born in Concarneau, Brittany who built two glider aircraft and performed at least one flight on board of his first machine in late 1856. His name ...

made the first powered flight, had his glider L'Albatros artificiel towed by a horse along a beach. In 1884, American

John J. Montgomery made controlled flights in a glider as a part of a series of gliders he built between 1883 and 1886.

Other aviators who made similar flights at that time were

Otto Lilienthal

Karl Wilhelm Otto Lilienthal (23 May 1848 – 10 August 1896) was a German pioneer of aviation who became known as the "flying man". He was the first person to make well-documented, repeated, successful flights with gliders, therefore making t ...

,

Percy Pilcher, and protégés of

Octave Chanute

Octave Chanute (February 18, 1832 – November 23, 1910) was a French-American civil engineer and aviation pioneer. He advised and publicized many aviation enthusiasts, including the Wright brothers. At his death, he was hailed as the father of ...

.

In the 1890s,

Lawrence Hargrave conducted research on wing structures and developed a

box kite

A box kite is a high-performance Kite flying, kite, noted for developing relatively high Lift (force), lift; it is a type within the family of cellular kites. The typical design has four parallel struts. The box is made rigid with diagonal cros ...

that lifted the weight of a man. His designs were widely adopted. He also developed a type of rotary aircraft engine, but did not create a powered fixed-wing aircraft.

Powered flight

Sir Hiram Maxim built a craft that weighed 3.5 tons, with a 110-foot (34-meter) wingspan powered by two 360-horsepower (270-kW) steam engines driving two propellers. In 1894, his machine was tested with overhead rails to prevent it from rising. The test showed that it had enough lift to take off. The craft was uncontrollable, and Maxim abandoned work on it.

The

Wright brothers

The Wright brothers, Orville Wright (August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) and Wilbur Wright (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912), were American aviation List of aviation pioneers, pioneers generally credited with inventing, building, and flyin ...

' flights in 1903 with their

''Flyer I'' are recognized by the ''

Fédération Aéronautique Internationale

The World Air Sports Federation (; FAI) is the world governing body for air sports, and also stewards definitions regarding human spaceflight. It was founded on 14 October 1905, and is headquartered in Lausanne, Switzerland. It maintains worl ...

'' (FAI), the standard setting and record-keeping body for

aeronautics

Aeronautics is the science or art involved with the study, design process, design, and manufacturing of air flight-capable machines, and the techniques of operating aircraft and rockets within the atmosphere.

While the term originally referred ...

, as "the first sustained and controlled heavier-than-air powered flight". By 1905, the

Wright Flyer III was capable of fully controllable, stable flight for substantial periods.

In 1906, Brazilian inventor

Alberto Santos Dumont designed,

built and piloted an aircraft that set the first world record recognized by the

Aéro-Club de France

The Aéro-Club de France () is one of the oldest French aviators' associations still active. It was founded as the Aéro-Club on 20 October 1898 as a society 'to encourage aerial locomotion' by Ernest Archdeacon, Léon Serpollet, Henri de la ...

by flying the

14 bis in less than 22 seconds. The flight was certified by the FAI.

The

Bleriot VIII design of 1908 was an early aircraft design that had the modern

monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple wings.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing con ...

tractor configuration. It had movable tail surfaces controlling both yaw and pitch, a form of roll control supplied either by wing warping or by ailerons and controlled by its pilot with a

joystick

A joystick, sometimes called a flight stick, is an input device consisting of a stick that pivots on a base and reports its angle or direction to the device it is controlling. Also known as the control column, it is the principal control devic ...

and rudder bar. It was an important predecessor of his later

Bleriot XI Channel-crossing aircraft of the summer of 1909.

World War I

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

served initiated the use of aircraft as weapons and observation platforms. The earliest known aerial victory with a synchronized

machine gun-armed

fighter aircraft

Fighter aircraft (early on also ''pursuit aircraft'') are military aircraft designed primarily for air-to-air combat. In military conflict, the role of fighter aircraft is to establish air supremacy, air superiority of the battlespace. Domina ...

occurred in 1915, flown by German

Luftstreitkräfte

The ''Deutsche Luftstreitkräfte'' (, German Air Combat Forces)known before October 1916 as (The Imperial German Air Service, lit. "The flying troops of the German Kaiser’s Reich")was the air arm of the Imperial German Army. In English-langu ...

Lieutenant

Kurt Wintgens.

Fighter aces appeared; the greatest (by number of air victories) was

Manfred von Richthofen

Manfred Albrecht Freiherr von Richthofen (; 2 May 1892 – 21 April 1918), known in English as Baron von Richthofen or the Red Baron, was a fighter pilot with the German Air Force during World War I. He is considered the ace-of-aces of th ...

.

Alcock and Brown crossed the Atlantic non-stop for the first time in 1919. The first commercial flights traveled between the

United States

The United States of America (USA), also known as the United States (U.S.) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It is a federal republic of 50 U.S. state, states and a federal capital district, Washington, D.C. The 48 ...

and

Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its Provinces and territories of Canada, ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, making it the world's List of coun ...

in 1919.

Interwar aviation; the "Golden Age"

The so-called Golden Age of Aviation occurred between the two World Wars, during which updated interpretations of earlier breakthroughs. Innovations include

Hugo Junkers

Hugo Junkers (3 February 1859 – 3 February 1935) was a German aircraft engineer and aircraft designer who pioneered the design of all-metal airplanes and flying wings. His company, Junkers Flugzeug- und Motorenwerke AG (Junkers Aircraft and ...

' all-metal air frames

in 1915 leading to multi-engine aircraft

of up to 60+ meter wingspan sizes by the early 1930s, adoption of the mostly air-cooled

radial engine

The radial engine is a reciprocating engine, reciprocating type internal combustion engine, internal combustion engine configuration in which the cylinder (engine), cylinders "radiate" outward from a central crankcase like the spokes of a wheel. ...

as a practical aircraft power plant alongside V-12 liquid-cooled aviation engines, and longer and longer flights – as with

a Vickers Vimy in 1919, followed months later by

the U.S. Navy's NC-4 transatlantic flight; culminating in May 1927 with

Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, and author. On May 20–21, 1927, he made the first nonstop flight from New York (state), New York to Paris, a distance of . His aircra ...

's solo trans-Atlantic flight in the

Spirit of St. Louis spurring ever-longer flight attempts.

World War II

Airplanes had a presence in the major battles of World War II. They were an essential component of military strategies, such as the German

Blitzkrieg

''Blitzkrieg'(Lightning/Flash Warfare)'' is a word used to describe a combined arms surprise attack, using a rapid, overwhelming force concentration that may consist of armored and motorized or mechanized infantry formations, together with ...

or the American and Japanese

aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and hangar facilities for supporting, arming, deploying and recovering carrier-based aircraft, shipborne aircraft. Typically it is the ...

campaigns of the Pacific.

Military glider

Military gliders (an offshoot of common gliders) have been used by the militaries of various countries for carrying troops ( glider infantry) and heavy equipment to a combat zone, mainly during the Second World War. These engineless aircraft wer ...

s were developed and used in several campaigns, but were limited by the high casualty rate encountered. The

Focke-Achgelis Fa 330

The Focke-Achgelis Fa 330 ''Bachstelze'' () is a type of rotary-wing kite, known as a rotor kite. They were towed behind German U-boats during World War II to allow a lookout to see further. About 200 were built by Weser Flugzeugbau.

Develop ...

''Bachstelze'' (Wagtail) rotor kite of 1942 was notable for its use by German

U-boats

U-boats are naval submarines operated by Germany, including during the First and Second World Wars. The term is an anglicized form of the German word , a shortening of (), though the German term refers to any submarine. Austro-Hungarian Na ...

.

Before and during the war, British and German designers worked on

jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine, discharging a fast-moving jet (fluid), jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition may include Rocket engine, rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and ...

s. The first

jet aircraft

A jet aircraft (or simply jet) is an aircraft (nearly always a fixed-wing aircraft) propelled by one or more jet engines.

Whereas the engines in Propeller (aircraft), propeller-powered aircraft generally achieve their maximum efficiency at much ...

to fly, in 1939, was the German

Heinkel He 178. In 1943, the first operational jet fighter, the

Messerschmitt Me 262

The Messerschmitt Me 262, nicknamed (German for "Swallow") in fighter versions, or ("Storm Bird") in fighter-bomber versions, is a fighter aircraft and fighter-bomber that was designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Messers ...

, went into service with the German

Luftwaffe

The Luftwaffe () was the aerial warfare, aerial-warfare branch of the before and during World War II. German Empire, Germany's military air arms during World War I, the of the Imperial German Army, Imperial Army and the of the Imperial Ge ...

. Later in the war the British

Gloster Meteor

The Gloster Meteor was the first British jet fighter and the Allies' only jet aircraft to engage in combat operations during the Second World War. The Meteor's development was heavily reliant on its ground-breaking turbojet engines, pioneere ...

entered service, but never saw action – top air speeds for that era went as high as , with the early July 1944 unofficial record flight of the German

Me 163B V18 rocket fighter prototype.

Postwar

In October 1947, the

Bell X-1

The Bell X-1 (Bell Model 44) is a rocket engine–powered aircraft, designated originally as the XS-1, and was a joint National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics– U.S. Army Air Forces– U.S. Air Force supersonic research project built by B ...

was the first aircraft to exceed the speed of sound, flown by

Chuck Yeager

Brigadier general (United States), Brigadier General Charles Elwood Yeager ( , February 13, 1923December 7, 2020) was a United States Air Force officer, flying ace, and record-setting test pilot who in October 1947 became the first pilot in his ...

.

In 1948–49, aircraft transported supplies during the

Berlin Blockade

The Berlin Blockade (24 June 1948 – 12 May 1949) was one of the first major international crises of the Cold War. During the multinational occupation of post–World War II Germany, the Soviet Union blocked the Western Allies' railway, roa ...

. New aircraft types, such as the

B-52, were produced during the

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

.

The first

jet airliner

A jet airliner or jetliner is an airliner powered by jet engines (passenger jet aircraft). Airliners usually have twinjet, two or quadjet, four jet engines; trijet, three-engined designs were popular in the 1970s but are less common today. Air ...

, the

de Havilland Comet

The de Havilland DH.106 Comet is the world's first commercial jet airliner. Developed and manufactured by de Havilland in the United Kingdom, the Comet 1 prototype first flew in 1949. It features an aerodynamically clean design with four ...

, was introduced in 1952, followed by the Soviet

Tupolev Tu-104 in 1956. The

Boeing 707

The Boeing 707 is an early American long-range Narrow-body aircraft, narrow-body airliner, the first jetliner developed and produced by Boeing Commercial Airplanes.

Developed from the Boeing 367-80 prototype, the initial first flew on Decembe ...

, the first widely successful commercial jet, was in commercial service for more than 50 years, from 1958 to 2010. The

Boeing 747

The Boeing 747 is a long-range wide-body aircraft, wide-body airliner designed and manufactured by Boeing Commercial Airplanes in the United States between 1968 and 2023.

After the introduction of the Boeing 707, 707 in October 1958, Pan Am ...

was the world's largest passenger aircraft from 1970 until it was surpassed by the

Airbus A380

The Airbus A380 is a very large wide-body airliner, developed and produced by Airbus until 2021. It is the world's largest passenger airliner and the only full-length double-deck jet airliner.

Airbus studies started in 1988, and the pr ...

in 2005. The most successful aircraft is the

Douglas DC-3

The Douglas DC-3 is a propeller-driven airliner manufactured by the Douglas Aircraft Company, which had a lasting effect on the airline industry in the 1930s to 1940s and World War II.

It was developed as a larger, improved 14-bed sleeper ...

and its military version, the

C-47, a medium sized twin engine passenger or transport aircraft that has been in service since 1936 and is still used throughout the world. Some of the hundreds of versions found other purposes, like the

AC-47, a

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (1 November 1955 – 30 April 1975) was an armed conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia fought between North Vietnam (Democratic Republic of Vietnam) and South Vietnam (Republic of Vietnam) and their allies. North Vietnam w ...

era gunship, which is still used in the

Colombian Air Force

The Colombian Aerospace Force (FAC, ) is the air force of the Republic of Colombia. The Colombian Aerospace Force is one of the three institutions of the Military Forces of Colombia charged, according to the 1991 Constitution, with working to exe ...

.

Types

Airplane/aeroplane

An airplane (spelled aeroplane in British English and shortened to plane) is a powered fixed-wing aircraft propelled by

thrust

Thrust is a reaction force described quantitatively by Newton's third law. When a system expels or accelerates mass in one direction, the accelerated mass will cause a force of equal magnitude but opposite direction to be applied to that ...

from a

jet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine, discharging a fast-moving jet (fluid), jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition may include Rocket engine, rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and ...

or

propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

. Planes come in many sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. Uses include

recreation

Recreation is an activity of leisure, leisure being discretionary time. The "need to do something for recreation" is an essential element of human biology and psychology. Recreational activities are often done for happiness, enjoyment, amusement, ...

, transportation of goods and people, military, and research.

Seaplane

A seaplane (hydroplane) is capable of

taking off and

landing

Landing is the last part of a flight, where a flying animal, aircraft, or spacecraft returns to the ground. When the flying object returns to water, the process is called alighting, although it is commonly called "landing", "touchdown" or " spl ...

(alighting) on water. Seaplanes that can also operate from dry land are a subclass called

amphibian aircraft. Seaplanes and amphibians divide into two categories:

float planes and

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

s.

* A

float plane is similar to a land-based airplane. The

fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

is not specialized. The wheels are replaced/enveloped by

floats, allowing the craft to make remain afloat for water landings.

* A

flying boat

A flying boat is a type of seaplane with a hull, allowing it to land on water. It differs from a floatplane in having a fuselage that is purpose-designed for flotation, while floatplanes rely on fuselage-mounted floats for buoyancy.

Though ...

is a

seaplane

A seaplane is a powered fixed-wing aircraft capable of takeoff, taking off and water landing, landing (alighting) on water.Gunston, "The Cambridge Aerospace Dictionary", 2009. Seaplanes are usually divided into two categories based on their tech ...

with a watertight

hull for the lower (ventral) areas of its fuselage. The fuselage lands and then rests directly on the water's surface, held afloat by the hull. It does not need additional floats for buoyancy, although small underwing floats or fuselage-mounted

sponson

Sponsons are projections extending from the sides of land vehicles, aircraft or watercraft to provide protection, Instantaneous stability, stability, storage locations, mounting points for weapons or other devices, or equipment housing.

Watercra ...

s may be used to stabilize it. Large seaplanes are usually flying boats, embodying most classic amphibian aircraft designs.

Powered gliders

Many forms of glider may include a small power plant. These include:

*

Motor glider – a conventional

glider or

sailplane

A glider or sailplane is a type of glider aircraft used in the leisure activity and sport of gliding (also called soaring). This unpowered aircraft can use naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmosphere to gain altitude. Sailplan ...

with an auxiliary power plant that may be used when in flight to increase performance.

*

Powered hang glider – a

hang glider

Hang gliding is an air sport or recreational activity in which a pilot flies a light, non-motorised, fixed-wing heavier-than-air aircraft called a hang glider. Most modern hang gliders are made of an aluminium alloy or composite frame covered ...

with a power plant added.

*

Powered parachute

A powered parachute, often abbreviated PPC, and also called a motorized parachute or paraplane, is a type of aircraft that consists of a parafoil with a motor and wheels.

The FAA defines a powered parachute as ''a powered aircraft a flexible or ...

– a

paraglider

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched Glider (aircraft), glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a :wikt:harness, harness or in ...

type of parachute with an integrated air frame, seat, undercarriage and power plant hung beneath.

*

Powered paraglider

Powered paragliding, also known as paramotoring or PPG, is a form of ultralight aviation where the pilot wears a back-pack motor (a paramotor) which provides enough thrust to take off using a paraglider. It can be launched in still air, and ...

or paramotor – a

paraglider

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched Glider (aircraft), glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a :wikt:harness, harness or in ...

with a power plant suspended behind the pilot.

Ground effect vehicle

A ground effect vehicle (GEV) flies close to the terrain, making use of the

ground effect – the interaction between the wings and the surface. Some GEVs are able to fly higher out of ground effect (OGE) when required – these are classed as powered fixed-wing aircraft.

Glider

A glider is a heavier-than-air craft whose free flight does not require an engine. A sailplane is a fixed-wing glider designed for soaring – gaining height using updrafts of air and to fly for long periods.

Gliders are mainly used for recreation but have found use for purposes such as

aerodynamics

Aerodynamics () is the study of the motion of atmosphere of Earth, air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an ...

research, warfare and spacecraft recovery.

Motor gliders

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into motion (physics), mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroe ...

are equipped with a limited

propulsion

Propulsion is the generation of force by any combination of pushing or pulling to modify the translational motion of an object, which is typically a rigid body (or an articulated rigid body) but may also concern a fluid. The term is derived from ...

system for takeoff, or to extend flight duration.

As is the case with planes, gliders come in diverse forms with varied wings, aerodynamic efficiency, pilot location, and controls.

Large gliders are most commonly born aloft by a tow-plane or by a

winch

A winch is a mechanical device that is used to pull in (wind up) or let out (wind out) or otherwise adjust the tension (physics), tension of a rope or wire rope (also called "cable" or "wire cable").

In its simplest form, it consists of a Bobb ...

.

Military glider

Military gliders (an offshoot of common gliders) have been used by the militaries of various countries for carrying troops ( glider infantry) and heavy equipment to a combat zone, mainly during the Second World War. These engineless aircraft wer ...

s have been used in combat to deliver troops and equipment, while specialized gliders have been used in atmospheric and

aerodynamic

Aerodynamics () is the study of the motion of atmosphere of Earth, air, particularly when affected by a solid object, such as an airplane wing. It involves topics covered in the field of fluid dynamics and its subfield of gas dynamics, and is an ...

research.

Rocket-powered aircraft and

spaceplane

A spaceplane is a vehicle that can flight, fly and gliding flight, glide as an aircraft in Earth's atmosphere and function as a spacecraft in outer space. To do so, spaceplanes must incorporate features of both aircraft and spacecraft. Orbit ...

s have made unpowered landings similar to a glider.

Gliders and sailplanes that are used for the sport of

gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

have high aerodynamic efficiency. The highest

lift-to-drag ratio is 70:1, though 50:1 is common. After take-off, further altitude can be gained through the skillful exploitation of rising air. Flights of thousands of kilometers at average speeds over 200 km/h have been achieved.

One small-scale example of a glider is the

paper airplane. An ordinary sheet of paper can be folded into an aerodynamic shape fairly easily; its low

mass

Mass is an Intrinsic and extrinsic properties, intrinsic property of a physical body, body. It was traditionally believed to be related to the physical quantity, quantity of matter in a body, until the discovery of the atom and particle physi ...

relative to its surface area reduces the required lift for flight, allowing it to glide some distance.

Gliders and sailplanes share many design elements and aerodynamic principles with powered aircraft. For example, the

Horten H.IV was a tailless

flying wing

A flying wing is a tailless fixed-wing aircraft that has no definite fuselage, with its crew, payload, fuel, and equipment housed inside the main wing structure. A flying wing may have various small protuberances such as pods, nacelles, blis ...

glider, and the

delta-winged Space Shuttle orbiter

The Space Shuttle orbiter is the spaceplane component of the Space Shuttle, a partially reusable launch system, reusable orbital spaceflight, orbital spacecraft system that was part of the discontinued Space Shuttle program. Operated from 1981 ...

glided during its descent phase. Many gliders adopt similar control surfaces and instruments as airplanes.

Types

The main application of modern glider aircraft is sport and recreation.

=Sailplane

=

Gliders were developed in the 1920s for recreational purposes. As pilots began to understand how to use rising air,

sailplane

A glider or sailplane is a type of glider aircraft used in the leisure activity and sport of gliding (also called soaring). This unpowered aircraft can use naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmosphere to gain altitude. Sailplan ...

gliders were developed with a high

lift-to-drag ratio. These allowed the craft to glide to the next source of "

lift", increasing their range. This gave rise to the popular sport of

gliding

Gliding is a recreational activity and competitive air sports, air sport in which pilots fly glider aircraft, unpowered aircraft known as Glider (sailplane), gliders or sailplanes using naturally occurring currents of rising air in the atmospher ...

.

Early gliders were built mainly of wood and metal, later replaced by composite materials incorporating glass, carbon or

aramid

Aramid fibers, short for aromatic polyamide, are a class of heat-resistant and strong synthetic fibers. They are used in aerospace and military applications, for ballistic-rated bulletproof vest, body armor cloth, fabric and ballistic composites ...

fibers. To minimize

drag, these types have a streamlined

fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

and long narrow wings incorporating a

high aspect ratio. Single-seat and two-seat gliders are available.

Initially, training was done by short "hops" in

primary glider

Primary glider aircraft, gliders are a category of aircraft that enjoyed worldwide popularity during the 1920s and 1930s as people strove for simple and inexpensive ways to learn to fly.Schweizer, Paul A: ''Wings Like Eagles, The Story of Soaring ...

s, which have no

cockpit and minimal instruments.

[Schweizer, Paul A: ''Wings Like Eagles, The Story of Soaring in the United States'', pages 14–22. Smithsonian Institution Press, 1988. ] Since shortly after World War II, training is done in two-seat dual control gliders, but high-performance two-seaters can make long flights. Originally skids were used for landing, later replaced by wheels, often retractable. Gliders known as

motor gliders are designed for unpowered flight, but can deploy

piston

A piston is a component of reciprocating engines, reciprocating pumps, gas compressors, hydraulic cylinders and pneumatic cylinders, among other similar mechanisms. It is the moving component that is contained by a cylinder (engine), cylinder a ...

,

rotary,

jet or

electric engines.

Gliders are classified by the

FAI for competitions into

glider competition classes mainly on the basis of wingspan and flaps.

A class of ultralight sailplanes, including some known as

microlift gliders and some known as airchairs, has been defined by the FAI based on weight. They are light enough to be transported easily, and can be flown without licensing in some countries. Ultralight gliders have performance similar to

hang gliders, but offer some crash safety as the pilot can strap into an upright seat within a deform-able structure. Landing is usually on one or two wheels which distinguishes these craft from hang gliders. Most are built by individual designers and hobbyists.

=Military gliders

=

Military gliders were used during World War II for carrying troops (

glider infantry) and heavy equipment to combat zones. The gliders were towed into the air and most of the way to their target by transport planes, e.g.

C-47 Dakota, or by one-time bombers that had been relegated to secondary activities, e.g.

Short Stirling. The advantage over paratroopers were that heavy equipment could be landed and that troops were quickly assembled rather than dispersed over a

parachute

A parachute is a device designed to slow an object's descent through an atmosphere by creating Drag (physics), drag or aerodynamic Lift (force), lift. It is primarily used to safely support people exiting aircraft at height, but also serves va ...

drop zone

A drop zone (DZ) is a place where parachutists or parachuted supplies land. It can be an area targeted for landing by paratroopers and airborne forces, or a base from which recreational parachutists and skydivers take off in aircraft and land ...

. The gliders were treated as disposable, constructed from inexpensive materials such as wood, though a few were re-used. By the time of the

Korean War

The Korean War (25 June 1950 – 27 July 1953) was an armed conflict on the Korean Peninsula fought between North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea; DPRK) and South Korea (Republic of Korea; ROK) and their allies. North Korea was s ...

, transport aircraft had become larger and more efficient so that even light tanks could be dropped by parachute, obsoleting gliders.

=Research gliders

=

Even after the development of powered aircraft, gliders continued to be used for

aviation research. The

NASA Paresev Rogallo flexible wing was developed to investigate alternative methods of recovering spacecraft. Although this application was abandoned, publicity inspired hobbyists to adapt the flexible-wing

airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is a streamlined body that is capable of generating significantly more Lift (force), lift than Drag (physics), drag. Wings, sails and propeller blades are examples of airfoils. Foil (fl ...

for hang gliders.

Initial research into many types of fixed-wing craft, including

flying wing

A flying wing is a tailless fixed-wing aircraft that has no definite fuselage, with its crew, payload, fuel, and equipment housed inside the main wing structure. A flying wing may have various small protuberances such as pods, nacelles, blis ...

s and

lifting bodies was also carried out using unpowered prototypes.

=Hang glider

=

A

hang glider

Hang gliding is an air sport or recreational activity in which a pilot flies a light, non-motorised, fixed-wing heavier-than-air aircraft called a hang glider. Most modern hang gliders are made of an aluminium alloy or composite frame covered ...

is a

glider aircraft

A glider is a fixed-wing aircraft that is supported in flight by the dynamic reaction of the air against its lifting surfaces, and whose gliding flight, free flight does not depend on an engine. Most gliders do not have an engine, although mot ...

in which the pilot is suspended in a harness suspended from the

air frame, and exercises control by shifting body weight in opposition to a control frame. Hang gliders are typically made of an

aluminum alloy or

composite-framed fabric wing. Pilots can

soar for hours, gain thousands of meters of altitude in

thermal

A thermal column (or thermal) is a rising mass of buoyant air, a convective current in the atmosphere, that transfers heat energy vertically. Thermals are created by the uneven heating of Earth's surface from solar radiation, and are an example ...

updrafts, perform aerobatics, and glide cross-country for hundreds of kilometers.

=Paraglider

=

A

paraglider

Paragliding is the recreational and competitive adventure sport of flying paragliders: lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched Glider (aircraft), glider aircraft with no rigid primary structure. The pilot sits in a :wikt:harness, harness or in ...

is a lightweight, free-flying, foot-launched glider with no rigid body. The pilot is suspended in a

harness below a hollow fabric wing whose shape is formed by its suspension lines. Air entering vents in the front of the wing and the aerodynamic forces of the air flowing over the outside power the craft. Paragliding is most often a recreational activity.

Unmanned gliders

A

paper plane is a toy aircraft (usually a glider) made out of paper or paperboard.

Model glider aircraft are models of aircraft using lightweight materials such as

polystyrene

Polystyrene (PS) is a synthetic polymer made from monomers of the aromatic hydrocarbon styrene. Polystyrene can be solid or foamed. General-purpose polystyrene is clear, hard, and brittle. It is an inexpensive resin per unit weight. It i ...

and

balsa wood. Designs range from simple glider aircraft to accurate

scale model

A scale model is a physical model that is geometrically similar to an object (known as the ''prototype''). Scale models are generally smaller than large prototypes such as vehicles, buildings, or people; but may be larger than small protot ...

s, some of which can be very large.

Glide bombs are bombs with aerodynamic surfaces to allow a gliding flight path rather than a ballistic one. This enables stand-off aircraft to attack a target from a distance.

Kite

A kite is a tethered aircraft held aloft by wind that blows over its wing(s). High pressure below the wing deflects the airflow downwards. This deflection generates horizontal

drag in the direction of the wind. The resultant force vector from the lift and drag force components is opposed by the tension of the

tether.

Kites are mostly flown for recreational purposes, but have many other uses. Early pioneers such as the

Wright Brothers

The Wright brothers, Orville Wright (August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) and Wilbur Wright (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912), were American aviation List of aviation pioneers, pioneers generally credited with inventing, building, and flyin ...

and

J.W. Dunne sometimes flew an aircraft as a kite in order to confirm its flight characteristics, before adding an engine and flight controls.

Applications

=Military

=

Kites have been used for signaling, for delivery of

munition

Ammunition, also known as ammo, is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. The term includes both expendable weapons (e.g., bombs, missiles, grenades, land mines), and the component parts of oth ...

s, and for

observation

Observation in the natural sciences is an act or instance of noticing or perceiving and the acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the percep ...

, by lifting an observer above the field of battle, and by using

kite aerial photography.

=Science and meteorology

=

Kites have been used for scientific purposes, such as

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin (April 17, 1790) was an American polymath: a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher and Political philosophy, political philosopher.#britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the m ...

's famous experiment proving that

lightning

Lightning is a natural phenomenon consisting of electrostatic discharges occurring through the atmosphere between two electrically charged regions. One or both regions are within the atmosphere, with the second region sometimes occurring on ...

is

electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter possessing an electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described by Maxwel ...

. Kites were the precursors to the traditional

aircraft

An aircraft ( aircraft) is a vehicle that is able to flight, fly by gaining support from the Atmosphere of Earth, air. It counters the force of gravity by using either Buoyancy, static lift or the Lift (force), dynamic lift of an airfoil, or, i ...

, and were instrumental in the development of early flying craft.

Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (; born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born Canadian Americans, Canadian-American inventor, scientist, and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He als ...

experimented with large

man-lifting kites, as did the

Wright brothers

The Wright brothers, Orville Wright (August 19, 1871 – January 30, 1948) and Wilbur Wright (April 16, 1867 – May 30, 1912), were American aviation List of aviation pioneers, pioneers generally credited with inventing, building, and flyin ...

and

Lawrence Hargrave. Kites had a historical role in lifting scientific instruments to measure atmospheric conditions for

weather forecasting

Weather forecasting or weather prediction is the application of science and technology forecasting, to predict the conditions of the Earth's atmosphere, atmosphere for a given location and time. People have attempted to predict the weather info ...

.

=Radio aerials and light beacons

=

Kites can be used to carry radio antennas. This method was used for the reception station of the first transatlantic transmission by

Marconi.

Captive balloons may be more convenient for such experiments, because kite-carried antennas require strong wind, which may be not always available with heavy equipment and a ground conductor.

Kites can be used to carry light sources such as light sticks or battery-powered lights.

=Kite traction

=

Kites can be used to pull people and vehicles downwind. Efficient

foil-type kites such as

power kite

A power kite or traction kite is a large kite designed to provide significant pull to the user.

Types

The two most common forms are the foil, and the leading edge inflatable. There are also other less common types of power kite including rig ...

s can also be used to sail upwind under the same principles as used by other sailing craft, provided that lateral forces on the ground or in the water are redirected as with the keels, center boards, wheels and ice blades of traditional sailing craft. In the last two decades,

kite sailing sports have become popular, such as

kite buggying,

kite landboarding,

kite boating and kite surfing.

Snow kiting is also popular.

Kite sailing opens several possibilities not available in traditional sailing:

* Wind speeds are greater at higher altitudes

* Kites may be maneuvered dynamically, which dramatically increases the available force

* Mechanical structures are not needed to withstand bending forces; vehicles/hulls can be light or eliminated.

=Power generation

=

Research and development projects investigate kites for harnessing high altitude wind currents for electricity generation.

= Cultural uses

=

Kite festivals are a popular form of entertainment throughout the world. They include local events, traditional festivals and major international festivals.

Designs

*

Bermuda kite

*

Bowed kite, e.g.

Rokkaku

*Cellular or

box kite

A box kite is a high-performance Kite flying, kite, noted for developing relatively high Lift (force), lift; it is a type within the family of cellular kites. The typical design has four parallel struts. The box is made rigid with diagonal cros ...

*

Chapi-chapi

*

Delta kite

*

Foil

Foil may refer to:

Materials

* Foil (metal), a quite thin sheet of metal, usually manufactured with a rolling mill machine

* Metal leaf, a very thin sheet of decorative metal

* Aluminium foil, a type of wrapping for food

* Tin foil, metal foil ma ...

,

parafoil or

bow kite

*

Malay kite see also

wau bulan

*

Tetrahedral kite

Types

*

Expanded polystyrene kite

*

Fighter kite

Fighter kites are kites used for the sport of kite fighting. Traditionally, most are small, unstable single-line flat kites where line tension alone is used for control, at least part of which is Manja (kite), manja, typically glass-coated co ...

*

Indoor kite

*

Inflatable single-line kite

*

Kytoon

*

Man-lifting kite

*

Rogallo parawing kite

*

Stunt (sport) kite

*

Water kite

Characteristics

Air frame

The structural element of a fixed-wing aircraft is the air frame. It varies according to the aircraft's type, purpose, and technology. Early airframes were made of wood with fabric wing surfaces, When engines became available for powered flight, their mounts were made of metal. As speeds increased metal became more common until by the end of World War II, all-metal (and glass) aircraft were common. In modern times,

composite material

A composite or composite material (also composition material) is a material which is produced from two or more constituent materials. These constituent materials have notably dissimilar chemical or physical properties and are merged to create a ...

s became more common.

Typical structural elements include:

* One or more mostly horizontal wings, often with an

airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is a streamlined body that is capable of generating significantly more Lift (force), lift than Drag (physics), drag. Wings, sails and propeller blades are examples of airfoils. Foil (fl ...

cross-section. The wing deflects air downward as the aircraft moves forward, generating

lifting force to support it in flight. The wing also provides lateral stability to stop the aircraft level in steady flight. Other roles are to hold the fuel and mount the engines.

* A

fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

, typically a long, thin body, usually with tapered or rounded ends to make its shape

aerodynamically slippery. The fuselage joins the other parts of the air frame and contains the payload, and flight systems.

* A

vertical stabilizer

A vertical stabilizer or tail fin is the static part of the vertical tail of an aircraft. The term is commonly applied to the assembly of both this fixed surface and one or more movable rudders hinged to it. Their role is to provide control, sta ...

or fin is a rigid surface mounted at the rear of the plane and typically protruding above it. The fin stabilizes the plane's

yaw (turn left or right) and mounts the

rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw ...

which controls its rotation along that axis.

* A

horizontal stabilizer, usually mounted at the tail near the vertical stabilizer. The horizontal stabilizer is used to stabilize the plane's

pitch (tilt up or down) and mounts the

elevators

An elevator (American English) or lift (English in the Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth English) is a machine that vertically transports people or freight between levels. They are typically powered by electric motors that drive tracti ...

that provide pitch control.

*

Landing gear

Landing gear is the undercarriage of an aircraft or spacecraft that is used for taxiing, takeoff or landing. For aircraft, it is generally needed for all three of these. It was also formerly called ''alighting gear'' by some manufacturers, s ...

, a set of wheels, skids, or floats that support the plane while it is not in flight. On seaplanes, the bottom of the fuselage or floats (pontoons) support it while on the water. On some planes, the landing gear retracts during the flight to reduce drag.

Wings

The wings of a fixed-wing aircraft are static planes extending to either side of the aircraft. When the aircraft travels forwards, air flows over the wings that are shaped to create lift.

Structure

Kites and some lightweight gliders and airplanes have flexible wing surfaces that are stretched across a frame and made rigid by the lift forces exerted by the airflow over them. Larger aircraft have rigid wing surfaces.

Whether flexible or rigid, most wings have a strong frame to give them shape and to transfer lift from the wing surface to the rest of the aircraft. The main structural elements are one or more spars running from root to tip, and ribs running from the leading (front) to the trailing (rear) edge.

Major components of a rigid wing.

Early airplane engines had little power and light weight was critical. Also, early airfoil sections were thin, and could not support a strong frame. Until the 1930s, most wings were so fragile that external bracing struts and wires were added. As engine power increased, wings could be made heavy and strong enough that bracing was unnecessary. Such an unbraced wing is called a

cantilever

A cantilever is a rigid structural element that extends horizontally and is unsupported at one end. Typically it extends from a flat vertical surface such as a wall, to which it must be firmly attached. Like other structural elements, a cantilev ...

wing.

Configuration

The number and shape of wings vary widely. Some designs blend the wing with the fuselage, while left and right wings separated by the fuselage are more common.

Occasionally more wings have been used, such as the three-winged

triplane

A triplane is a fixed-wing aircraft equipped with three vertically stacked wing planes. Tailplanes and canard (aeronautics), canard foreplanes are not normally included in this count, although they occasionally are.

Design principles

The trip ...

from World War I. Four-winged

quadruplanes and other

multiplane designs have had little success.

Most planes are

monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple wings.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing con ...

s, with one or two parallel wings.

Biplanes

A biplane is a fixed-wing aircraft with two main wings stacked one above the other. The first powered, controlled aeroplane to fly, the Wright Flyer, used a biplane wing arrangement, as did many aircraft in the early years of aviation. While a ...

and

triplanes stack one wing above the other.

Tandem wings place one wing behind the other, possibly joined at the tips. When the available engine power increased during the 1920s and 1930s and bracing was no longer needed, the unbraced or cantilever monoplane became the most common form.

The

planform is the shape when seen from above/below. To be aerodynamically efficient, wings are straight with a long span, but a short chord (high

aspect ratio

The aspect ratio of a geometry, geometric shape is the ratio of its sizes in different dimensions. For example, the aspect ratio of a rectangle is the ratio of its longer side to its shorter side—the ratio of width to height, when the rectangl ...

). To be structurally efficient, and hence lightweight, wingspan must be as small as possible, but offer enough area to provide lift.

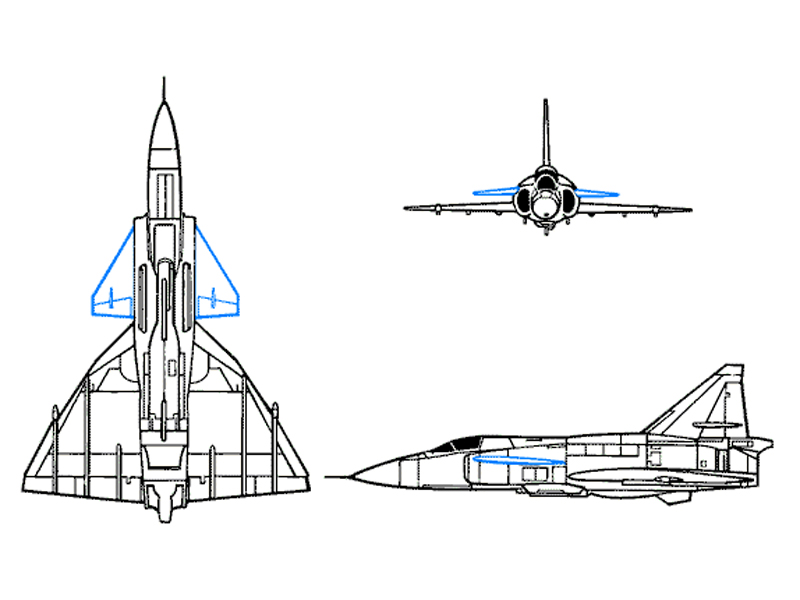

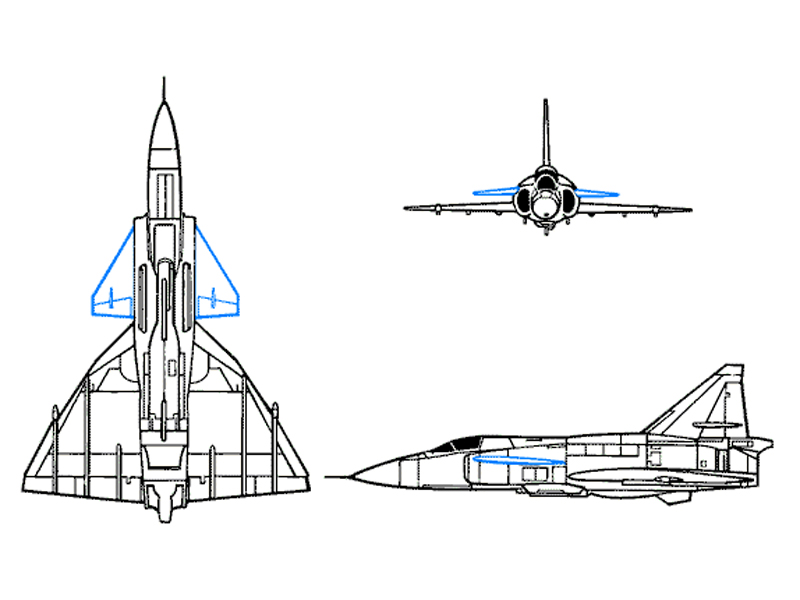

To travel at

transonic

Transonic (or transsonic) flow is air flowing around an object at a speed that generates regions of both subsonic and Supersonic speed, supersonic airflow around that object. The exact range of speeds depends on the object's critical Mach numb ...

speeds, variable geometry wings change orientation, angling backward to reduce drag from supersonic shock waves. The

variable-sweep wing

A variable-sweep wing, colloquially known as a "swing wing", is an airplane wing, or set of wings, that may be modified during flight, swept back and then returned to its previous straight position. Because it allows the aircraft's shape to ...

transforms between an efficient straight configuration for

takeoff and landing

Aircraft have different ways to take off and land. Conventional airplanes accelerate along the ground until reaching a speed that is sufficient for the airplane to takeoff and climb at a safe speed. Some airplanes can take off at low speed, this b ...

, to a low-drag swept configuration for high-speed flight. Other forms of variable planform have been flown, but none have gone beyond the research stage. The

swept wing

A swept wing is a wing angled either backward or occasionally forward from its root rather than perpendicular to the fuselage.

Swept wings have been flown since the pioneer days of aviation. Wing sweep at high speeds was first investigated in Ge ...

is a straight wing swept backward or forwards.

The

delta wing

A delta wing is a wing shaped in the form of a triangle. It is named for its similarity in shape to the Greek uppercase letter delta (letter), delta (Δ).

Although long studied, the delta wing did not find significant practical applications unti ...

is a triangular shape that serves various purposes. As a flexible

Rogallo wing, it allows a stable shape under aerodynamic forces, and is often used for kites and other ultralight craft. It is supersonic capable, combining high strength with low drag.

Wings are typically hollow, also serving as fuel tanks. They are equipped with

flaps, which allow the wing to increase/decrease drag/lift, for take-off and landing, and acting in opposition, to change direction.

Fuselage

The fuselage is typically long and thin, usually with tapered or rounded ends to make its shape

aerodynamically smooth. Most fixed-wing aircraft have a single fuselage. Others may have multiple fuselages, or the fuselage may be fitted with booms on either side of the tail to allow the extreme rear of the fuselage to be utilized.

The fuselage typically carries the

flight crew

Aircrew are personnel who operate an aircraft while in flight. The composition of a flight's crew depends on the type of aircraft, plus the flight's duration and purpose.

Commercial aviation

Flight deck positions

In commercial aviation, ...

, passengers, cargo, and sometimes fuel and engine(s).

Gliders typically omit fuel and engines, although some variations such as

motor gliders and

rocket gliders have them for temporary or optional use.

Pilots of manned commercial fixed-wing aircraft control them from inside a

cockpit within the fuselage, typically located at the front/top, equipped with controls, windows, and instruments, separated from passengers by a secure door. In small aircraft, the passengers typically sit behind the pilot(s) in the cabin, Occasionally, a passenger may sit beside or in front of the pilot. Larger

passenger aircraft

An airliner is a type of airplane for transporting passengers and air cargo. Such aircraft are most often operated by airlines. The modern and most common variant of the airliner is a long, tube shaped, and jetliner, jet powered aircraft. The ...

have a separate passenger cabin or occasionally cabins that are physically separated from the cockpit.

Aircraft often have two or more pilots, with one in overall command (the "pilot") and one or more "co-pilots". On larger aircraft a

navigator

A navigator is the person on board a ship or aircraft responsible for its navigation.Grierson, MikeAviation History—Demise of the Flight Navigator FrancoFlyers.org website, October 14, 2008. Retrieved August 31, 2014. The navigator's prim ...

is typically also seated in the cockpit as well. Some military or specialized aircraft may have other flight crew members in the cockpit as well.

Wings vs. bodies

Flying wing

A flying wing is a

tailless aircraft

In aeronautics, a tailless aircraft is a fixed-wing aircraft with no other horizontal aerodynamic surface besides its main wing. It may still have a fuselage, vertical tail fin (vertical stabilizer), and/or vertical rudder.

Theoretical advanta ...

that has no distinct

fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

, housing the crew, payload, and equipment inside.

[Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition''. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ]

The flying wing configuration was studied extensively in the 1930s and 1940s, notably by

Jack Northrop and

Cheston L. Eshelman in the United States, and

Alexander Lippisch

Alexander Martin Lippisch (2 November 1894 – 11 February 1976) was a German aeronautical engineer, a pioneer of aerodynamics who made important contributions to the understanding of tailless aircraft, delta wings and the ground effect in aircra ...

and the

Horten brothers in Germany. After the war, numerous experimental designs were based on the flying wing concept. General interest continued into the 1950s, but designs did not offer a great advantage in range and presented technical problems. The flying wing is most practical for designs in the slow-to-medium speed range, and drew continual interest as a tactical

airlift

An airlift is the organized delivery of Materiel, supplies or personnel primarily via military transport aircraft.

Airlifting consists of two distinct types: strategic and tactical. Typically, strategic airlifting involves moving material lo ...

er design.

Interest in flying wings reemerged in the 1980s due to their potentially low

radar cross-sections.

Stealth technology

Stealth technology, also termed low observable technology (LO technology), is a sub-discipline of military tactics and passive and active electronic countermeasures. The term covers a range of military technology, methods used to make personnel ...

relies on shapes that reflect radar waves only in certain directions, thus making it harder to detect. This approach eventually led to the Northrop

B-2 Spirit

The Northrop B-2 Spirit, also known as the Stealth Bomber, is an American Heavy bomber, heavy strategic bomber, featuring low-observable stealth aircraft, stealth technology designed to penetrator (aircraft), penetrate dense anti-aircraft war ...

stealth bomber (pictured). The flying wing's aerodynamics are not the primary concern. Computer-controlled

fly-by-wire

Fly-by-wire (FBW) is a system that replaces the conventional aircraft flight control system#Hydro-mechanical, manual flight controls of an aircraft with an electronic interface. The movements of flight controls are converted to electronic sig ...

systems compensated for many of the aerodynamic drawbacks, enabling an efficient and stable long-range aircraft.

Blended wing body

Blended wing body aircraft have a flattened airfoil-shaped body, which produces most of the lift to keep itself aloft, and distinct and separate wing structures, though the wings are blended with the body.

Blended wing bodied aircraft incorporate design features from both fuselage and flying wing designs. The purported advantages of the blended wing body approach are efficient, high-lift wings and a wide,

airfoil

An airfoil (American English) or aerofoil (British English) is a streamlined body that is capable of generating significantly more Lift (force), lift than Drag (physics), drag. Wings, sails and propeller blades are examples of airfoils. Foil (fl ...

-shaped body. This enables the entire craft to contribute to

lift generation with potentially increased fuel economy.

Lifting body

A lifting body is a configuration in which the body produces

lift. In contrast to a

flying wing

A flying wing is a tailless fixed-wing aircraft that has no definite fuselage, with its crew, payload, fuel, and equipment housed inside the main wing structure. A flying wing may have various small protuberances such as pods, nacelles, blis ...

, which is a wing with minimal or no conventional

fuselage

The fuselage (; from the French language, French ''fuselé'' "spindle-shaped") is an aircraft's main body section. It holds Aircrew, crew, passengers, or cargo. In single-engine aircraft, it will usually contain an Aircraft engine, engine as wel ...

, a lifting body can be thought of as a fuselage with little or no conventional wing. Whereas a flying wing seeks to maximize cruise efficiency at

subsonic speeds by eliminating non-lifting surfaces, lifting bodies generally minimize the drag and structure of a wing for subsonic,

supersonic

Supersonic speed is the speed of an object that exceeds the speed of sound (Mach 1). For objects traveling in dry air of a temperature of 20 °C (68 °F) at sea level, this speed is approximately . Speeds greater than five times ...

, and

hypersonic

In aerodynamics, a hypersonic speed is one that exceeds five times the speed of sound, often stated as starting at speeds of Mach 5 and above.

The precise Mach number at which a craft can be said to be flying at hypersonic speed varies, since i ...

flight, or,

spacecraft

A spacecraft is a vehicle that is designed spaceflight, to fly and operate in outer space. Spacecraft are used for a variety of purposes, including Telecommunications, communications, Earth observation satellite, Earth observation, Weather s ...

re-entry

Atmospheric entry (sometimes listed as Vimpact or Ventry) is the movement of an object from outer space into and through the gases of an atmosphere of a planet, dwarf planet, or natural satellite. Atmospheric entry may be ''uncontrolled entry ...

. All of these flight regimes pose challenges for flight stability.

Lifting bodies were a major area of research in the 1960s and 1970s as a means to build small and lightweight crewed spacecraft. The US built lifting body rocket planes to test the concept, as well as several rocket-launched re-entry vehicles. Interest waned as the

US Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the Air force, air service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is one of the six United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Tracing its ori ...

lost interest in the crewed mission, and major development ended during the

Space Shuttle design process when it became clear that highly shaped fuselages made it difficult to fit fuel tanks.

Empennage and foreplane

The classic airfoil section wing is unstable in flight. Flexible-wing planes often rely on an anchor line or the weight of a pilot hanging beneath to maintain the correct attitude. Some free-flying types use an adapted airfoil that is stable, or other mechanisms including electronic artificial stability.

In order to achieve trim, stability, and control, most fixed-wing types have an

empennage

The empennage ( or ), also known as the tail or tail assembly, is a structure at the rear of an aircraft that provides stability during flight, in a way similar to the feathers on an arrow.Crane, Dale: ''Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third ed ...

comprising a fin and rudder that act horizontally, and a tailplane and elevator that act vertically. This is so common that it is known as the conventional layout. Sometimes two or more fins are spaced out along the tailplane.

Some types have a horizontal "

canard" foreplane ahead of the main wing, instead of behind it.

[Aviation Publishers Co. Limited, ''From the Ground Up'', page 10 (27th revised edition) ] This foreplane may contribute to the trim, stability or control of the aircraft, or to several of these.

Aircraft controls

Kite control

Kites are controlled by one or more tethers.

Free-flying aircraft controls

Gliders and airplanes have sophisticated control systems, especially if they are piloted.

The controls allow the pilot to direct the aircraft in the air and on the ground. Typically these are:

*The

yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, used in dif ...

or

joystick

A joystick, sometimes called a flight stick, is an input device consisting of a stick that pivots on a base and reports its angle or direction to the device it is controlling. Also known as the control column, it is the principal control devic ...

controls rotation of the plane about the pitch and roll axes. A

yoke

A yoke is a wooden beam used between a pair of oxen or other animals to enable them to pull together on a load when working in pairs, as oxen usually do; some yokes are fitted to individual animals. There are several types of yoke, used in dif ...

resembles a steering wheel. The pilot can pitch the plane down by pushing on the yoke or joystick, and pitch the plane up by pulling on it. Rolling the plane is accomplished by turning the yoke in the direction of the desired roll, or by tilting the joystick in that direction.

*

Rudder

A rudder is a primary control surface used to steer a ship, boat, submarine, hovercraft, airship, or other vehicle that moves through a fluid medium (usually air or water). On an airplane, the rudder is used primarily to counter adverse yaw ...

pedals control rotation of the plane about the yaw axis. Two pedals pivot so that when one is pressed forward the other moves backward, and vice versa. The pilot presses on the right rudder pedal to make the plane yaw to the right, and pushes on the left pedal to make it yaw to the left. The rudder is used mainly to balance the plane in turns, or to compensate for winds or other effects that push the plane about the yaw axis.

*On powered types, an engine stop control ("fuel cutoff", for example) and, usually, a

Throttle

A throttle is a mechanism by which fluid flow is managed by construction or obstruction.

An engine's power can be increased or decreased by the restriction of inlet gases (by the use of a throttle), but usually decreased. The term ''throttle'' ha ...

or

thrust lever

Thrust levers or throttle levers are found in the cockpit of aircraft, and are used by the Pilot in command, pilot, copilot, flight engineer, or autopilot to control the thrust output of the aircraft's aircraft engine, engines, by controlling th ...

and other controls, such as a fuel-mixture control (to compensate for air density changes with altitude change).

Other common controls include:

*

Flap levers, which are used to control the deflection position of flaps on the wings.

*

Spoiler levers, which are used to control the position of spoilers on the wings, and to arm their automatic deployment in planes designed to deploy them upon landing. The spoilers reduce lift for landing.

*

Trim controls, which usually take the form of knobs or wheels and are used to adjust pitch, roll, or yaw trim. These are often connected to small airfoils on the trailing edge of the control surfaces and are called "trim tabs". Trim is used to reduce the amount of pressure on the control forces needed to maintain a steady course.

*On wheeled types,

brake

A brake is a machine, mechanical device that inhibits motion by absorbing energy from a moving system. It is used for Acceleration, slowing or stopping a moving vehicle, wheel, axle, or to prevent its motion, most often accomplished by means of ...

s are used to slow and stop the plane on the ground, and sometimes for turns on the ground.

A craft may have two pilot seats with dual controls, allowing two to take turns.

The control system may allow full or partial automation, such as an

autopilot

An autopilot is a system used to control the path of a vehicle without requiring constant manual control by a human operator. Autopilots do not replace human operators. Instead, the autopilot assists the operator's control of the vehicle, allow ...

, a wing leveler, or a

flight management system. An

unmanned aircraft

An unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) or unmanned aircraft system (UAS), commonly known as a drone, is an aircraft with no human Aircraft pilot, pilot, crew, or passengers onboard, but rather is controlled remotely or is autonomous.De Gruyter H ...

has no pilot and is controlled remotely or via gyroscopes, computers/sensors or other forms of autonomous control.

Cockpit instrumentation

On manned fixed-wing aircraft, instruments provide information to the pilots, including

flight

Flight or flying is the motion (physics), motion of an Physical object, object through an atmosphere, or through the vacuum of Outer space, space, without contacting any planetary surface. This can be achieved by generating aerodynamic lift ass ...

,

engines

An engine or motor is a machine designed to convert one or more forms of energy into mechanical energy.

Available energy sources include potential energy (e.g. energy of the Earth's gravitational field as exploited in hydroelectric power gen ...

,

navigation

Navigation is a field of study that focuses on the process of monitoring and controlling the motion, movement of a craft or vehicle from one place to another.Bowditch, 2003:799. The field of navigation includes four general categories: land navig ...

,

communications

Communication is commonly defined as the transmission of information. Its precise definition is disputed and there are disagreements about whether Intention, unintentional or failed transmissions are included and whether communication not onl ...

, and other aircraft systems that may be installed.

The six basic instruments, sometimes referred to as the six pack, are:

* The

airspeed indicator