F Actin on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Actin is a

There are a number of different types of actin with slightly different structures and functions. α-actin is found exclusively in muscle fibres, while β- and γ-actin are found in other cells. As the latter types have a high turnover rate the majority of them are found outside permanent structures. Microfilaments found in cells other than muscle cells are present in three forms:

* Microfilament networks -

There are a number of different types of actin with slightly different structures and functions. α-actin is found exclusively in muscle fibres, while β- and γ-actin are found in other cells. As the latter types have a high turnover rate the majority of them are found outside permanent structures. Microfilaments found in cells other than muscle cells are present in three forms:

* Microfilament networks -  * Periodic actin rings - A periodic structure constructed of evenly spaced actin rings is found in

* Periodic actin rings - A periodic structure constructed of evenly spaced actin rings is found in

Even though the majority of plant cells have a

Even though the majority of plant cells have a

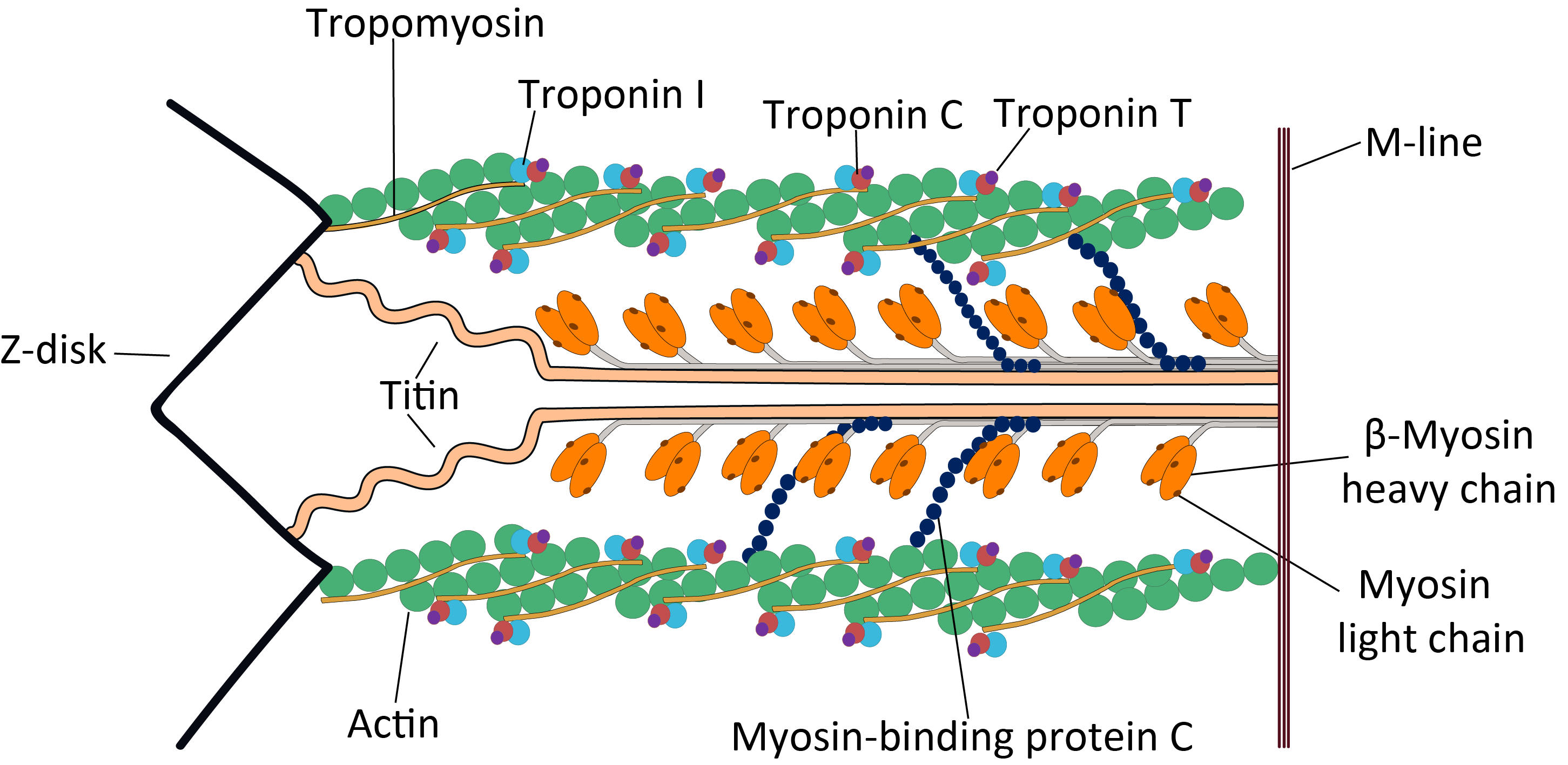

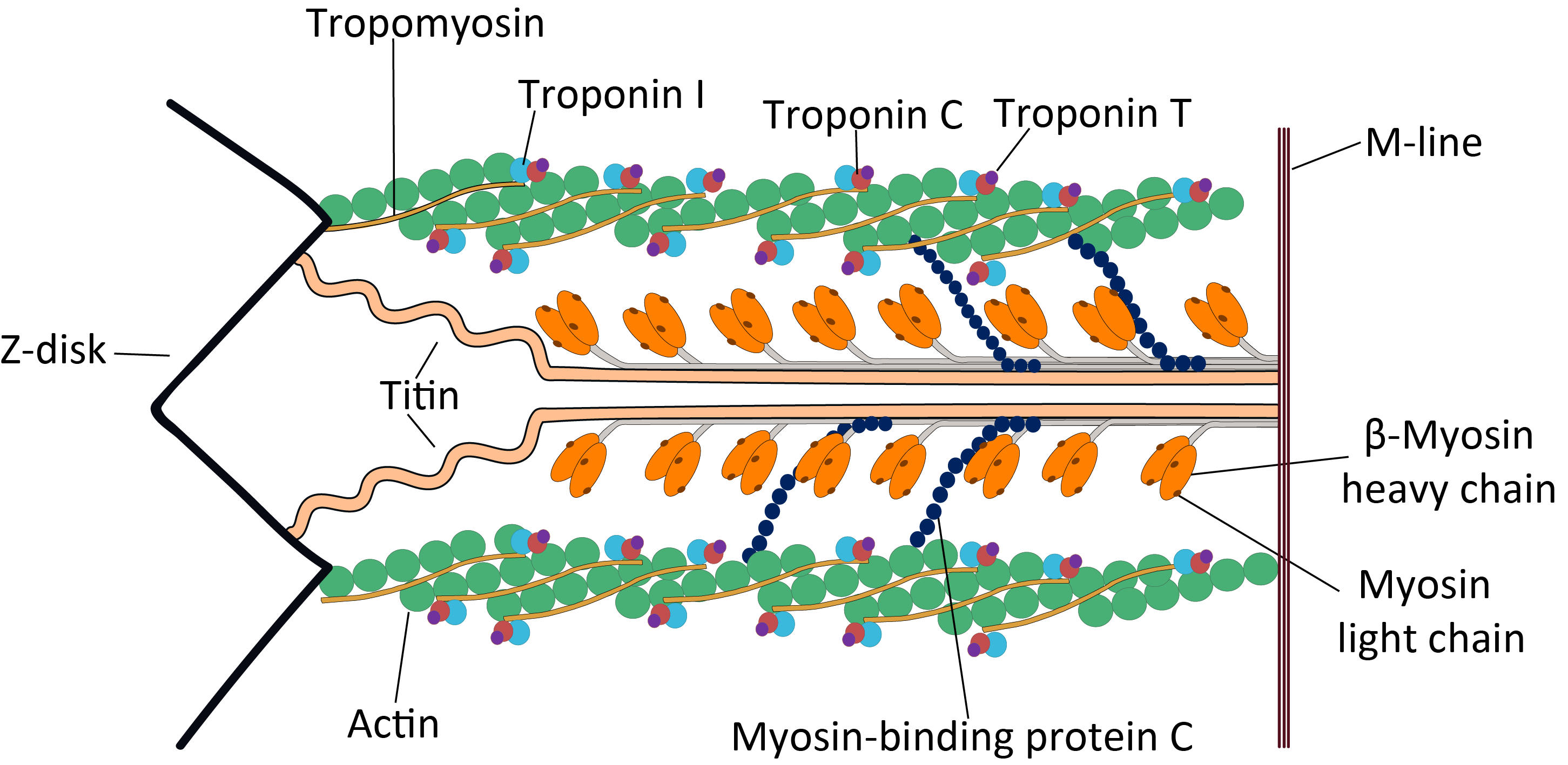

Actin plays a particularly prominent role in muscle cells, which consist largely of repeated bundles of actin and

Actin plays a particularly prominent role in muscle cells, which consist largely of repeated bundles of actin and

*

*

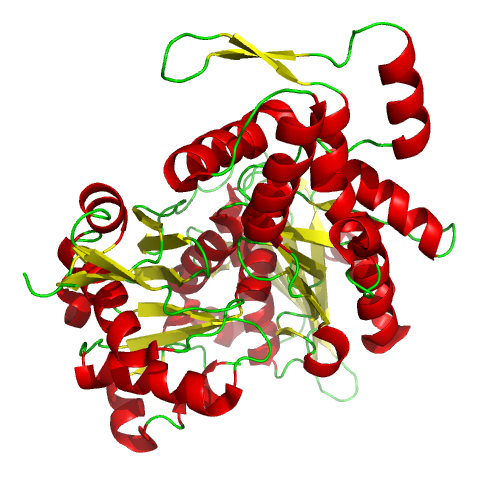

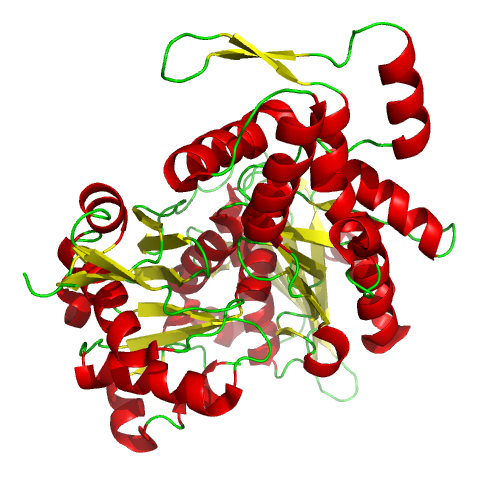

Under various conditions, G-actin molecules polymerize into longer threads called "filamentous-" or "F-actin". These F-actin threads are typically composed of two helical strands of actin wound around each other, forming a 7 to 9

Under various conditions, G-actin molecules polymerize into longer threads called "filamentous-" or "F-actin". These F-actin threads are typically composed of two helical strands of actin wound around each other, forming a 7 to 9

Actin can spontaneously acquire a large part of its

Actin can spontaneously acquire a large part of its  The CCT then causes actin's sequential folding by forming bonds with its subunits rather than simply enclosing it in its cavity. This is why it possesses specific recognition areas in its apical β-domain. The first stage in the folding consists of the recognition of residues 245–249. Next, other determinants establish contact. Both actin and tubulin bind to CCT in open conformations in the absence of ATP. In actin's case, two subunits are bound during each conformational change, whereas for tubulin binding takes place with four subunits. Actin has specific binding sequences, which interact with the δ and β-CCT subunits or with δ-CCT and ε-CCT. After AMP-PNP is bound to CCT the substrates move within the chaperonin's cavity. It also seems that in the case of actin, the CAP (protein), CAP protein is required as a possible cofactor in actin's final folding states.

The exact manner by which this process is regulated is still not fully understood, but it is known that the protein PhLP3 (a protein similar to phosducin) inhibits its activity through the formation of a tertiary complex.

The CCT then causes actin's sequential folding by forming bonds with its subunits rather than simply enclosing it in its cavity. This is why it possesses specific recognition areas in its apical β-domain. The first stage in the folding consists of the recognition of residues 245–249. Next, other determinants establish contact. Both actin and tubulin bind to CCT in open conformations in the absence of ATP. In actin's case, two subunits are bound during each conformational change, whereas for tubulin binding takes place with four subunits. Actin has specific binding sequences, which interact with the δ and β-CCT subunits or with δ-CCT and ε-CCT. After AMP-PNP is bound to CCT the substrates move within the chaperonin's cavity. It also seems that in the case of actin, the CAP (protein), CAP protein is required as a possible cofactor in actin's final folding states.

The exact manner by which this process is regulated is still not fully understood, but it is known that the protein PhLP3 (a protein similar to phosducin) inhibits its activity through the formation of a tertiary complex.

Actin filaments are often rapidly assembled and disassembled, allowing them to generate force and support cell movement. Assembly classically occurs in three steps. First, the "nucleation phase", in which two to three G-actin molecules slowly join to form a small oligomer that will nucleate further growth. Second, the "elongation phase", when the actin filament rapidly grows by the addition of many actin molecules to both ends. As the filament grows, actin molecules are added to the (+) end of the filament around 10 times faster than to the (−) end, and so filaments tend to primarily grow at the (+) end. Third, the "steady-state phase", where an equillibrium is reached as actin molecules join and leave the filament at the same rate, maintaining the filament's length. While the filament's length remains constant in the steady-state phase, new molecules are constantly being added to the (+) end and falling off the (−) end, a phenomenon called "treadmilling" as a given actin molecule would appear to move along the strand. In isolation, whether a filament will grow or shrink, and how quickly, are determined by the concentration of G-actin around the filament; however, in cells, the dynamics of actin filaments are heavily influenced by various actin-binding proteins.

Actin filaments are often rapidly assembled and disassembled, allowing them to generate force and support cell movement. Assembly classically occurs in three steps. First, the "nucleation phase", in which two to three G-actin molecules slowly join to form a small oligomer that will nucleate further growth. Second, the "elongation phase", when the actin filament rapidly grows by the addition of many actin molecules to both ends. As the filament grows, actin molecules are added to the (+) end of the filament around 10 times faster than to the (−) end, and so filaments tend to primarily grow at the (+) end. Third, the "steady-state phase", where an equillibrium is reached as actin molecules join and leave the filament at the same rate, maintaining the filament's length. While the filament's length remains constant in the steady-state phase, new molecules are constantly being added to the (+) end and falling off the (−) end, a phenomenon called "treadmilling" as a given actin molecule would appear to move along the strand. In isolation, whether a filament will grow or shrink, and how quickly, are determined by the concentration of G-actin around the filament; however, in cells, the dynamics of actin filaments are heavily influenced by various actin-binding proteins.

The nucleation of new actin filaments – the rate-limiting step in actin polymerization – is aided by actin-nucleating proteins such as formins (like formin-2) and the Arp2/3 complex. Formins help to nucleate long actin filaments. They bind two free actin-ATP molecules, bringing them together. Then as the filament begins to grow, formin moves along the (+) end of the growing filament, all the while recruiting actin-binding proteins that promote filament growth, and excluding capping proteins that would block filament extension. Branches in actin filaments are typically nucleated by the Arp2/3 complex in concert with nucleation promoting factors. Nucleation promoting factors bind two free G-actin molecules, then recruit and activate the Arp2/3 complex. The activated Arp2/3 complex attaches to an existing actin filament, and uses the two bound G-actin molecules to nucleate a new actin filament branching off of the old one at a 70° angle.

The nucleation of new actin filaments – the rate-limiting step in actin polymerization – is aided by actin-nucleating proteins such as formins (like formin-2) and the Arp2/3 complex. Formins help to nucleate long actin filaments. They bind two free actin-ATP molecules, bringing them together. Then as the filament begins to grow, formin moves along the (+) end of the growing filament, all the while recruiting actin-binding proteins that promote filament growth, and excluding capping proteins that would block filament extension. Branches in actin filaments are typically nucleated by the Arp2/3 complex in concert with nucleation promoting factors. Nucleation promoting factors bind two free G-actin molecules, then recruit and activate the Arp2/3 complex. The activated Arp2/3 complex attaches to an existing actin filament, and uses the two bound G-actin molecules to nucleate a new actin filament branching off of the old one at a 70° angle.

As filaments grow, the pool of available G-actin molecules is managed by G-actin-binding proteins such as

As filaments grow, the pool of available G-actin molecules is managed by G-actin-binding proteins such as  Other proteins bind to the ends of actin filaments, stabilizing them. These are called "capping proteins" and include CapZ and tropomodulin. CapZ binds the (+) end of a filament, preventing further addition or loss of actin from that end. Tropomodulin binds to a filament's (−) end, again preventing addition or loss of molecule's at that end. Tropomodulin is typically found in cells that require extremely stable actin filaments, such as those in muscle and red blood cells.

These actin binding proteins are typically regulated by various cellular signals to control actin assembly dynamics in different cellular locations. Formins, for example, are typically folded in an inactive conformation until they're activated by the binding of the small GTPase Rho family of GTPases, Rho. Actin branching at the cell membrane is important for cell movement, and so the plasma membrane lipid Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PIP2 activates the nucleation promoting factor Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein, WASp and inhibits CapZ. WASp is also activated by the small GTPase Cdc42, while another nucleation promoting factor WAVE is activated by the GTPase Rac1.

Other proteins bind to the ends of actin filaments, stabilizing them. These are called "capping proteins" and include CapZ and tropomodulin. CapZ binds the (+) end of a filament, preventing further addition or loss of actin from that end. Tropomodulin binds to a filament's (−) end, again preventing addition or loss of molecule's at that end. Tropomodulin is typically found in cells that require extremely stable actin filaments, such as those in muscle and red blood cells.

These actin binding proteins are typically regulated by various cellular signals to control actin assembly dynamics in different cellular locations. Formins, for example, are typically folded in an inactive conformation until they're activated by the binding of the small GTPase Rho family of GTPases, Rho. Actin branching at the cell membrane is important for cell movement, and so the plasma membrane lipid Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate, PIP2 activates the nucleation promoting factor Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome protein, WASp and inhibits CapZ. WASp is also activated by the small GTPase Cdc42, while another nucleation promoting factor WAVE is activated by the GTPase Rac1.

Although most

Although most

Some authors point out that the behaviour of actin, tubulin, and histone, a protein involved in the stabilization and regulation of DNA, are similar in their ability to bind nucleotides and in their ability of take advantage of Brownian motion. It has also been suggested that they all have a common ancestor. Therefore, evolutionary processes resulted in the diversification of ancestral proteins into the varieties present today, conserving, among others, actins as efficient molecules that were able to tackle essential ancestral biological processes, such as

Some authors point out that the behaviour of actin, tubulin, and histone, a protein involved in the stabilization and regulation of DNA, are similar in their ability to bind nucleotides and in their ability of take advantage of Brownian motion. It has also been suggested that they all have a common ancestor. Therefore, evolutionary processes resulted in the diversification of ancestral proteins into the varieties present today, conserving, among others, actins as efficient molecules that were able to tackle essential ancestral biological processes, such as

The mutation alters the structure and function of skeletal muscles producing one of three forms of myopathy: type 3 nemaline myopathy, Congenital myopathy, congenital myopathy with an excess of thin myofilaments (CM) and Congenital myopathy#Congenital fiber type disproportion, congenital myopathy with fibre type disproportion (CMFTD). Mutations have also been found that produce Central core disease, core myopathies. Although their phenotypes are similar, in addition to typical nemaline myopathy some specialists distinguish another type of myopathy called actinic nemaline myopathy. In the former, clumps of actin form instead of the typical rods. It is important to state that a patient can show more than one of these

The mutation alters the structure and function of skeletal muscles producing one of three forms of myopathy: type 3 nemaline myopathy, Congenital myopathy, congenital myopathy with an excess of thin myofilaments (CM) and Congenital myopathy#Congenital fiber type disproportion, congenital myopathy with fibre type disproportion (CMFTD). Mutations have also been found that produce Central core disease, core myopathies. Although their phenotypes are similar, in addition to typical nemaline myopathy some specialists distinguish another type of myopathy called actinic nemaline myopathy. In the former, clumps of actin form instead of the typical rods. It is important to state that a patient can show more than one of these

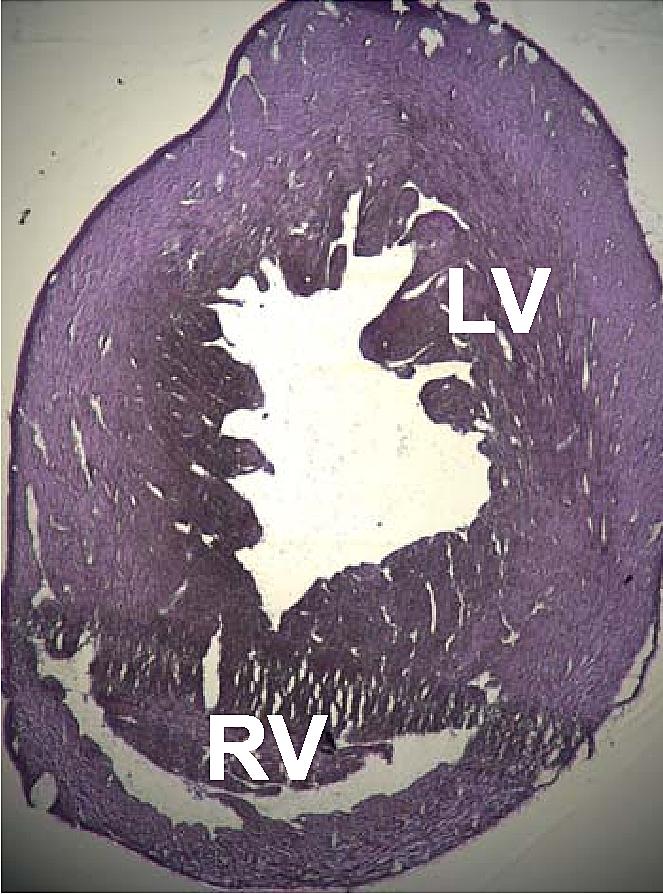

A number of structural disorders associated with point mutations of this gene have been described that cause malfunctioning of the heart, such as Type 1R dilated cardiomyopathy and Type 11 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Certain defects of the Atrium (heart), atrial septum have been described recently that could also be related to these mutations.

Two cases of dilated cardiomyopathy have been studied involving a substitution of highly conserved

A number of structural disorders associated with point mutations of this gene have been described that cause malfunctioning of the heart, such as Type 1R dilated cardiomyopathy and Type 11 hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Certain defects of the Atrium (heart), atrial septum have been described recently that could also be related to these mutations.

Two cases of dilated cardiomyopathy have been studied involving a substitution of highly conserved

Three pathological processes have so far been discovered that are caused by a direct alteration in gene sequence:

* Hemangiopericytoma with t(7;12)(p22;q13)-translocations is a rare affliction, in which a Mutation#By effect on structure, translocational mutation causes the fusion of the ''ACTB'' gene over GLI1 in Chromosome 12 (human), Chromosome 12.

* Juvenile onset dystonia is a rare degenerative disease that affects the central nervous system; in particular, it affects areas of the neocortex and thalamus, where rod-like eosinophilic inclusions are formed. The affected individuals represent a

Three pathological processes have so far been discovered that are caused by a direct alteration in gene sequence:

* Hemangiopericytoma with t(7;12)(p22;q13)-translocations is a rare affliction, in which a Mutation#By effect on structure, translocational mutation causes the fusion of the ''ACTB'' gene over GLI1 in Chromosome 12 (human), Chromosome 12.

* Juvenile onset dystonia is a rare degenerative disease that affects the central nervous system; in particular, it affects areas of the neocortex and thalamus, where rod-like eosinophilic inclusions are formed. The affected individuals represent a

*Actin is used as an internal control in western blots to ascertain that equal amounts of protein have been loaded on each lane of the gel. In the blot example shown on the left side, 75 μg of total protein was loaded in each well. The blot was reacted with anti-β-actin antibody (for other details of the blot see the reference )

The use of actin as an internal control is based on the assumption that its expression is practically constant and independent of experimental conditions. By comparing the expression of the gene of interest to that of the actin, it is possible to obtain a relative quantity that can be compared between different experiments, whenever the expression of the latter is constant. It is worth pointing out that actin does not always have the desired stability in its

*Actin is used as an internal control in western blots to ascertain that equal amounts of protein have been loaded on each lane of the gel. In the blot example shown on the left side, 75 μg of total protein was loaded in each well. The blot was reacted with anti-β-actin antibody (for other details of the blot see the reference )

The use of actin as an internal control is based on the assumption that its expression is practically constant and independent of experimental conditions. By comparing the expression of the gene of interest to that of the actin, it is possible to obtain a relative quantity that can be compared between different experiments, whenever the expression of the latter is constant. It is worth pointing out that actin does not always have the desired stability in its

A number of natural toxins that interfere with actin's dynamics are widely used in research to study actin's role in biology. Latrunculin – a toxin produced by sponges – binds to G-actin preventing it from joining microfilaments. Cytochalasin D – produced by certain fungi – serves as a capping factor, binding to the (+) end of a filament and preventing further addition of actin molecules. In contrast, the sponge toxin jasplakinolide promotes the nucleation of new actin filaments by binding and stabilzing pairs of actin molecules. Phalloidin – from the "death cap" mushroom ''Amanita phalloides'' – binds to adjacent actin molecules within the F-actin filament, stabilizing the filament and preventing its depolymerization.

Phalloidin is often labelled with Fluorophore, fluorescent dyes to visualize actin filaments by fluorescence microscopy.

A number of natural toxins that interfere with actin's dynamics are widely used in research to study actin's role in biology. Latrunculin – a toxin produced by sponges – binds to G-actin preventing it from joining microfilaments. Cytochalasin D – produced by certain fungi – serves as a capping factor, binding to the (+) end of a filament and preventing further addition of actin molecules. In contrast, the sponge toxin jasplakinolide promotes the nucleation of new actin filaments by binding and stabilzing pairs of actin molecules. Phalloidin – from the "death cap" mushroom ''Amanita phalloides'' – binds to adjacent actin molecules within the F-actin filament, stabilizing the filament and preventing its depolymerization.

Phalloidin is often labelled with Fluorophore, fluorescent dyes to visualize actin filaments by fluorescence microscopy.

Actin Staining Techniques (Live and Fixed Cell Staining)

* * *

3D macromolecular structures of actin filaments from the EM Data Bank(EMDB)

{{Authority control Autoantigens Cytoskeleton proteins Articles containing video clips

family

Family (from ) is a Social group, group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or Affinity (law), affinity (by marriage or other relationship). It forms the basis for social order. Ideally, families offer predictabili ...

of globular

A globular cluster is a spheroidal conglomeration of stars that is bound together by gravity, with a higher concentration of stars towards its center. It can contain anywhere from tens of thousands to many millions of member stars, all orbiting ...

multi-functional protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residue (biochemistry), residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including Enzyme catalysis, catalysing metab ...

s that form microfilament

Microfilaments, also called actin filaments, are protein filaments in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that form part of the cytoskeleton. They are primarily composed of polymers of actin, but are modified by and interact with numerous other ...

s in the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

, and the thin filaments in muscle fibrils. It is found in essentially all eukaryotic cells

The eukaryotes ( ) constitute the domain of Eukaryota or Eukarya, organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, seaweeds, and many unicellular organisms are eukaryotes. They constitute a major group of li ...

, where it may be present at a concentration of over 100 μM

The micrometre (Commonwealth English as used by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures; SI symbol: μm) or micrometer (American English), also commonly known by the non-SI term micron, is a unit of length in the International System ...

; its mass is roughly 42 kDa

The dalton or unified atomic mass unit (symbols: Da or u, respectively) is a unit of mass defined as of the mass of an unbound neutral atom of carbon-12 in its nuclear and electronic ground state and at rest. It is a non-SI unit accepted f ...

, with a diameter of 4 to 7 nm.

An actin protein is the monomer

A monomer ( ; ''mono-'', "one" + '' -mer'', "part") is a molecule that can react together with other monomer molecules to form a larger polymer chain or two- or three-dimensional network in a process called polymerization.

Classification

Chemis ...

ic subunit of two types of filaments in cells: microfilaments

Microfilaments, also called actin filaments, are protein filaments in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that form part of the cytoskeleton. They are primarily composed of polymers of actin, but are modified by and interact with numerous other p ...

, one of the three major components of the cytoskeleton, and thin filaments, part of the contractile apparatus in muscle

Muscle is a soft tissue, one of the four basic types of animal tissue. There are three types of muscle tissue in vertebrates: skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, and smooth muscle. Muscle tissue gives skeletal muscles the ability to muscle contra ...

cells. It can be present as either a free monomer

A monomer ( ; ''mono-'', "one" + '' -mer'', "part") is a molecule that can react together with other monomer molecules to form a larger polymer chain or two- or three-dimensional network in a process called polymerization.

Classification

Chemis ...

called G-actin (globular) or as part of a linear polymer

A polymer () is a chemical substance, substance or material that consists of very large molecules, or macromolecules, that are constituted by many repeat unit, repeating subunits derived from one or more species of monomers. Due to their br ...

microfilament called F-actin (filamentous), both of which are essential for such important cellular functions as the mobility

Mobility may refer to:

Social sciences and humanities

* Economic mobility, ability of individuals or families to improve their economic status

* Geographic mobility, the measure of how populations and goods move over time

* Mobilities, a conte ...

and contraction of cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

* Cellphone, a phone connected to a cellular network

* Clandestine cell, a penetration-resistant form of a secret or outlawed organization

* Electrochemical cell, a d ...

during cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

.

Actin participates in many important cellular processes, including muscle contraction

Muscle contraction is the activation of Tension (physics), tension-generating sites within muscle cells. In physiology, muscle contraction does not necessarily mean muscle shortening because muscle tension can be produced without changes in musc ...

, cell motility

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently using metabolism, metabolic energy. This biological concept encompasses movement at various levels, from whole organisms to cells and subcellular components.

Motility is observed in ...

, cell division and cytokinesis

Cytokinesis () is the part of the cell division process and part of mitosis during which the cytoplasm of a single eukaryotic cell divides into two daughter cells. Cytoplasmic division begins during or after the late stages of nuclear division ...

, vesicle

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

; In human embryology

* Vesicle (embryology), bulge-like features ...

and organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

movement, cell signaling

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) is the Biological process, process by which a Cell (biology), cell interacts with itself, other cells, and the environment. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all Cell (biol ...

, and the establishment and maintenance of cell junction

Cell junctions or junctional complexes are a class of cellular structures consisting of multiprotein complexes that provide contact or adhesion between neighboring Cell (biology), cells or between a cell and the extracellular matrix in animals. Th ...

s and cell shape. Many of these processes are mediated by extensive and intimate interactions of actin with cellular membranes. In vertebrates, three main groups of actin isoforms

A protein isoform, or "protein variant", is a member of a set of highly similar proteins that originate from a single gene and are the result of genetic differences. While many perform the same or similar biological roles, some isoforms have uniqu ...

, alpha

Alpha (uppercase , lowercase ) is the first letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of one. Alpha is derived from the Phoenician letter ''aleph'' , whose name comes from the West Semitic word for ' ...

, beta

Beta (, ; uppercase , lowercase , or cursive ; or ) is the second letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 2. In Ancient Greek, beta represented the voiced bilabial plosive . In Modern Greek, it represe ...

, and gamma

Gamma (; uppercase , lowercase ; ) is the third letter of the Greek alphabet. In the system of Greek numerals it has a value of 3. In Ancient Greek, the letter gamma represented a voiced velar stop . In Modern Greek, this letter normally repr ...

have been identified. The alpha actins, found in muscle tissues, are a major constituent of the contractile apparatus. The beta and gamma actins coexist in most cell types as components of the cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

, and as mediators of internal cell motility

Motility is the ability of an organism to move independently using metabolism, metabolic energy. This biological concept encompasses movement at various levels, from whole organisms to cells and subcellular components.

Motility is observed in ...

. It is believed that the diverse range of structures formed by actin enabling it to fulfill such a large range of functions is regulated through the binding of tropomyosin

Tropomyosin is a two-stranded alpha-helical, coiled coil protein found in many animal and fungal cells. In animals, it is an important component of the muscular system which works in conjunction with troponin to regulate muscle contraction. It ...

along the filaments.

A cell's ability to dynamically form microfilaments provides the scaffolding that allows it to rapidly remodel itself in response to its environment or to the organism's internal signals

A signal is both the process and the result of Signal transmission, transmission of data over some transmission media, media accomplished by embedding some variation. Signals are important in multiple subject fields including signal processin ...

, for example, to increase cell membrane absorption or increase cell adhesion

Cell adhesion is the process by which cells interact and attach to neighbouring cells through specialised molecules of the cell surface. This process can occur either through direct contact between cell surfaces such as Cell_junction, cell junc ...

in order to form cell tissue. Other enzymes or organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s such as cilia

The cilium (: cilia; ; in Medieval Latin and in anatomy, ''cilium'') is a short hair-like membrane protrusion from many types of eukaryotic cell. (Cilia are absent in bacteria and archaea.) The cilium has the shape of a slender threadlike proj ...

can be anchored to this scaffolding in order to control the deformation of the external cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

, which allows endocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which Chemical substance, substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a Vesicle (biology and chem ...

and cytokinesis

Cytokinesis () is the part of the cell division process and part of mitosis during which the cytoplasm of a single eukaryotic cell divides into two daughter cells. Cytoplasmic division begins during or after the late stages of nuclear division ...

. It can also produce movement either by itself or with the help of molecular motors

Molecular motors are natural (biological) or artificial molecular machines that are the essential agents of movement in living organisms. In general terms, a motor is a device that consumes energy in one form and converts it into motion or mech ...

. Actin therefore contributes to processes such as the intracellular transport of vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles (or neurotransmitter vesicles) s ...

and organelles as well as muscular contraction

Muscle contraction is the activation of tension-generating sites within muscle cells. In physiology, muscle contraction does not necessarily mean muscle shortening because muscle tension can be produced without changes in muscle length, such as ...

and cellular migration

Cell migration is a central process in the development and maintenance of multicellular organisms. Tissue formation during embryonic development, wound healing and immune responses all require the orchestrated movement of cells in particular dir ...

. It therefore plays an important role in embryogenesis

An embryo ( ) is the initial stage of development for a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male ...

, the healing of wounds, and the invasivity of cancer

Cancer is a group of diseases involving Cell growth#Disorders, abnormal cell growth with the potential to Invasion (cancer), invade or Metastasis, spread to other parts of the body. These contrast with benign tumors, which do not spread. Po ...

cells. The evolutionary origin of actin can be traced to prokaryotic cells

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a single-celled organism whose cell lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Greek (), meaning 'before', and (), meaning 'nut' or ...

, which have equivalent proteins. Actin homologs from prokaryotes and archaea polymerize into different helical or linear filaments consisting of one or multiple strands. However the in-strand contacts and nucleotide binding sites are preserved in prokaryotes and in archaea. Lastly, actin plays an important role in the control of gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

.

A large number of illnesses and diseases are caused by mutation

In biology, a mutation is an alteration in the nucleic acid sequence of the genome of an organism, virus, or extrachromosomal DNA. Viral genomes contain either DNA or RNA. Mutations result from errors during DNA or viral replication, ...

s in allele

An allele is a variant of the sequence of nucleotides at a particular location, or Locus (genetics), locus, on a DNA molecule.

Alleles can differ at a single position through Single-nucleotide polymorphism, single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP), ...

s of the gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s that regulate the production of actin or of its associated proteins. The production of actin is also key to the process of infection

An infection is the invasion of tissue (biology), tissues by pathogens, their multiplication, and the reaction of host (biology), host tissues to the infectious agent and the toxins they produce. An infectious disease, also known as a transmis ...

by some pathogen

In biology, a pathogen (, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of"), in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a Germ theory of d ...

ic microorganism

A microorganism, or microbe, is an organism of microscopic scale, microscopic size, which may exist in its unicellular organism, single-celled form or as a Colony (biology)#Microbial colonies, colony of cells. The possible existence of unseen ...

s. Mutations in the different genes that regulate actin production in humans can cause muscular diseases, variations in the size and function of the heart

The heart is a muscular Organ (biology), organ found in humans and other animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels. The heart and blood vessels together make the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrie ...

as well as deafness

Deafness has varying definitions in cultural and medical contexts. In medical contexts, the meaning of deafness is hearing loss that precludes a person from understanding spoken language, an audiological condition. In this context it is writte ...

. The make-up of the cytoskeleton is also related to the pathogenicity of intracellular bacteria

Bacteria (; : bacterium) are ubiquitous, mostly free-living organisms often consisting of one Cell (biology), biological cell. They constitute a large domain (biology), domain of Prokaryote, prokaryotic microorganisms. Typically a few micr ...

and virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living Cell (biology), cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea. Viruses are ...

es, particularly in the processes related to evading the actions of the immune system

The immune system is a network of biological systems that protects an organism from diseases. It detects and responds to a wide variety of pathogens, from viruses to bacteria, as well as Tumor immunology, cancer cells, Parasitic worm, parasitic ...

.

Function

Actin's primary role in the cell is to form linear polymers calledmicrofilament

Microfilaments, also called actin filaments, are protein filaments in the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells that form part of the cytoskeleton. They are primarily composed of polymers of actin, but are modified by and interact with numerous other ...

s that serve various functions in the cell's structure, trafficking networks, migration, and replication. The multifaceted role of actin relies on a few of the microfilaments' properties: First, the formation of actin filaments is reversible, and their function often involves undergoing rapid polymerization and depolymerization. Second, microfilaments are polarized – i.e. the two ends of a filament are distinct from one another. Third, actin filaments can bind to many other proteins, which together help modify and organize microfilaments for their diverse functions.

In most cells actin filaments form larger-scale networks which are essential for many key functions:

* Actin networks give mechanical support to cells and provide trafficking routes through the cytoplasm to aid signal transduction.

* Rapid assembly and disassembly of actin network enables cells to migrate (Cell migration

Cell migration is a central process in the development and maintenance of multicellular organisms. Tissue formation during embryogenesis, embryonic development, wound healing and immune system, immune responses all require the orchestrated movemen ...

).

Actin is extremely abundant in most cells, comprising 1–5% of the total protein mass of most cells, and 10% of muscle cells.

The actin protein is found in both the cytoplasm

The cytoplasm describes all the material within a eukaryotic or prokaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, including the organelles and excluding the nucleus in eukaryotic cells. The material inside the nucleus of a eukaryotic cell a ...

and the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (; : nuclei) is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have #Anucleated_cells, ...

. Its location is regulated by cell membrane signal transduction

Signal transduction is the process by which a chemical or physical signal is transmitted through a cell as a biochemical cascade, series of molecular events. Proteins responsible for detecting stimuli are generally termed receptor (biology), rece ...

pathways that integrate the stimuli that a cell receives stimulating the restructuring of the actin networks in response.

Cytoskeleton

There are a number of different types of actin with slightly different structures and functions. α-actin is found exclusively in muscle fibres, while β- and γ-actin are found in other cells. As the latter types have a high turnover rate the majority of them are found outside permanent structures. Microfilaments found in cells other than muscle cells are present in three forms:

* Microfilament networks -

There are a number of different types of actin with slightly different structures and functions. α-actin is found exclusively in muscle fibres, while β- and γ-actin are found in other cells. As the latter types have a high turnover rate the majority of them are found outside permanent structures. Microfilaments found in cells other than muscle cells are present in three forms:

* Microfilament networks - Animal cell

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of all life, forms of life. Every cell consists of cytoplasm enclosed within a Cell membrane, membrane; many cells contain organelles, each with a specific function. The term comes from the ...

s commonly have a cell cortex

The cell cortex, also known as the actin cortex, cortical cytoskeleton or actomyosin cortex, is a specialized layer of cytoplasmic proteins on the inner face of the cell membrane. It functions as a modulator of membrane behavior and cell surface p ...

under the cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of a cell from the outside environment (the extr ...

that contains a large number of microfilaments, which precludes the presence of organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s. This network is connected with numerous receptor

Receptor may refer to:

* Sensory receptor, in physiology, any neurite structure that, on receiving environmental stimuli, produces an informative nerve impulse

*Receptor (biochemistry), in biochemistry, a protein molecule that receives and respond ...

s that relay signals to the outside of a cell.

* Periodic actin rings - A periodic structure constructed of evenly spaced actin rings is found in

* Periodic actin rings - A periodic structure constructed of evenly spaced actin rings is found in axon

An axon (from Greek ἄξων ''áxōn'', axis) or nerve fiber (or nerve fibre: see American and British English spelling differences#-re, -er, spelling differences) is a long, slender cellular extensions, projection of a nerve cell, or neuron, ...

s. In this structure, the actin rings, together with spectrin

Spectrin is a cytoskeletal protein that lines the intracellular side of the plasma membrane in eukaryotic cells. Spectrin forms pentagonal or hexagonal arrangements, forming a scaffold and playing an important role in maintenance of plasma mem ...

tetramers that link the neighboring actin rings, form a cohesive cytoskeleton

The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is compos ...

that supports the axon membrane. The structure periodicity may also regulate the sodium ion channel

Sodium channels are integral membrane proteins that form ion channels, conducting sodium ions (Na+) through a cell (biology), cell's cell membrane, membrane. They belong to the Cation channel superfamily, superfamily of cation channels.

Classific ...

s in axons.

Yeasts

Actin's cytoskeleton is key to the processes ofendocytosis

Endocytosis is a cellular process in which Chemical substance, substances are brought into the cell. The material to be internalized is surrounded by an area of cell membrane, which then buds off inside the cell to form a Vesicle (biology and chem ...

, cytokinesis

Cytokinesis () is the part of the cell division process and part of mitosis during which the cytoplasm of a single eukaryotic cell divides into two daughter cells. Cytoplasmic division begins during or after the late stages of nuclear division ...

, determination of cell polarity

Cell polarity refers to spatial differences in shape, structure, and function within a cell. Almost all cell types exhibit some form of polarity, which enables them to carry out specialized functions. Classical examples of polarized cells are de ...

and morphogenesis

Morphogenesis (from the Greek ''morphê'' shape and ''genesis'' creation, literally "the generation of form") is the biological process that causes a cell, tissue or organism to develop its shape. It is one of three fundamental aspects of deve ...

in yeast

Yeasts are eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms classified as members of the fungus kingdom (biology), kingdom. The first yeast originated hundreds of millions of years ago, and at least 1,500 species are currently recognized. They are est ...

s. In addition to relying on actin, these processes involve 20 or 30 associated proteins, which all have a high degree of evolutionary conservation, along with many signalling molecules. Together these elements allow a spatially and temporally modulated assembly that defines a cell's response to both internal and external stimuli.

Yeasts contain three main elements that are associated with actin: patches, cables, and rings. Despite not being present for long, these structures are subject to a dynamic equilibrium due to continual polymerization and depolymerization. They possess a number of accessory proteins including ADF/cofilin, which has a molecular weight of 16kDa and is coded for by a single gene, called ''COF1''; Aip1, a cofilin cofactor that promotes the disassembly of microfilaments; Srv2/CAP, a process regulator related to adenylate cyclase

Adenylate cyclase (EC 4.6.1.1, also commonly known as adenyl cyclase and adenylyl cyclase, abbreviated AC) is an enzyme with systematic name ATP diphosphate-lyase (cyclizing; 3′,5′-cyclic-AMP-forming). It catalyzes the following reaction:

:A ...

proteins; a profilin with a molecular weight of approximately 14 kDa that is related/associated with actin monomers; and twinfilin, a 40 kDa protein involved in the organization of patches.

Plants

Plantgenome

A genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding genes, other functional regions of the genome such as ...

studies have revealed the existence of protein isovariants within the actin family of genes. Within ''Arabidopsis thaliana

''Arabidopsis thaliana'', the thale cress, mouse-ear cress or arabidopsis, is a small plant from the mustard family (Brassicaceae), native to Eurasia and Africa. Commonly found along the shoulders of roads and in disturbed land, it is generally ...

'', a model organism

A model organism is a non-human species that is extensively studied to understand particular biological phenomena, with the expectation that discoveries made in the model organism will provide insight into the workings of other organisms. Mo ...

, there are ten types of actin, six profilins, and dozens of myosins. This diversity is explained by the evolutionary necessity of possessing variants that slightly differ in their temporal and spatial expression. The majority of these proteins were jointly expressed in the tissue analysed. Actin networks are distributed throughout the cytoplasm of cells that have been cultivated ''in vitro

''In vitro'' (meaning ''in glass'', or ''in the glass'') Research, studies are performed with Cell (biology), cells or biological molecules outside their normal biological context. Colloquially called "test-tube experiments", these studies in ...

''. There is a concentration of the network around the nucleus that is connected via spokes to the cellular cortex, this network is highly dynamic, with a continuous polymerization and depolymerization.

Even though the majority of plant cells have a

Even though the majority of plant cells have a cell wall

A cell wall is a structural layer that surrounds some Cell type, cell types, found immediately outside the cell membrane. It can be tough, flexible, and sometimes rigid. Primarily, it provides the cell with structural support, shape, protection, ...

that defines their morphology, their microfilaments can generate sufficient force to achieve a number of cellular activities, such as the cytoplasmic currents generated by the microfilaments and myosin. Actin is also involved in the movement of organelles and in cellular morphogenesis, which involve cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

as well as the elongation and differentiation of the cell.

The most notable proteins associated with the actin cytoskeleton in plants include: villin

Villin-1 is a 92.5 kDa tissue-specific actin-binding protein associated with the actin core bundle of the brush border. Villin-1 is encoded by the ''VIL1'' gene. Villin-1 contains multiple gelsolin-like domains capped by a small (8.5 kDa) "headp ...

, which belongs to the same family as gelsolin

Gelsolin is an actin-binding protein that is a key regulator of actin filament assembly and disassembly. Gelsolin is one of the most potent members of the actin-severing gelsolin/villin superfamily, as it severs with nearly 100% efficiency.

Cellu ...

/severin and is able to cut microfilaments and bind actin monomers in the presence of calcium cations; fimbrin

Fimbrin also known as is plastin 1 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the PLS1 gene. Fimbrin is an actin cross-linking protein important in the formation of filopodia.

Structure

Fimbrin belongs to the calponin homology (CH) domain sup ...

, which is able to recognize and unite actin monomers and which is involved in the formation of networks (by a different regulation process from that of animals and yeasts); formin

Formins (formin homology proteins) are a group of proteins that are involved in the polymerization of actin and associate with the fast-growing end (barbed end) of actin filaments. Most formins are Rho-GTPase effector proteins. Formins re ...

s, which are able to act as an F-actin polymerization nucleating agent; myosin

Myosins () are a Protein family, family of motor proteins (though most often protein complexes) best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are adenosine triphosphate, ATP- ...

, a typical molecular motor that is specific to eukaryotes and which in ''Arabidopsis thaliana'' is coded for by 17 genes in two distinct classes; CHUP1, which can bind actin and is implicated in the spatial distribution of chloroplast

A chloroplast () is a type of membrane-bound organelle, organelle known as a plastid that conducts photosynthesis mostly in plant cell, plant and algae, algal cells. Chloroplasts have a high concentration of chlorophyll pigments which captur ...

s in the cell; KAM1/MUR3 that define the morphology of the Golgi apparatus

The Golgi apparatus (), also known as the Golgi complex, Golgi body, or simply the Golgi, is an organelle found in most eukaryotic Cell (biology), cells. Part of the endomembrane system in the cytoplasm, it protein targeting, packages proteins ...

as well as the composition of xyloglucan

Xyloglucan is a hemicellulose that occurs in the primary cell wall of all vascular plants; however, all enzymes responsible for xyloglucan metabolism are found in Charophyceae algae.LEV Del Bem and M Vincentz (2010) Evolution of xyloglucan-relate ...

s in the cell wall; NtWLIM1, which facilitates the emergence of actin cell structures; and ERD10, which is involved in the association of organelles within membranes

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. B ...

and microfilaments and which seems to play a role that is involved in an organism's reaction to stress.

Nuclear actin

Nuclear actin was first noticed and described in 1977 by Clark and Merriam. Authors describe a protein present in the nuclear fraction, obtained from ''Xenopus laevis'' oocytes, which shows the same features as skeletal muscle actin. Since that time there have been many scientific reports about the structure and functions of actin in the nucleus (for review see: Hofmann 2009.) The controlled level of actin in the nucleus, its interaction with actin-binding proteins (ABP) and the presence of different isoforms allows actin to play an important role in many important nuclear processes.Transport through the nuclear membrane

The actin sequence does not contain a nuclear localization signal. The small size of actin (about 43 kDa) allows it to enter the nucleus by passive diffusion. The import of actin into the nucleus (probably in a complex with cofilin) is facilitated by the import protein importin 9. Low levels of actin in the nucleus seems to be important, because actin has two nuclear export signals (NES) in its sequence. Microinjected actin is quickly removed from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Actin is exported at least in two ways, through exportin 1 and exportin 6. Specific modifications, such as SUMOylation, allows for nuclear actin retention. A mutation preventing SUMOylation causes rapid export of beta actin from the nucleus.Organization

Nuclear actin exists mainly as a monomer, but can also form dynamic oligomers and short polymers. Nuclear actin organization varies in different cell types. For example, in ''Xenopus'' oocytes (with higher nuclear actin level in comparison to somatic cells) actin forms filaments, which stabilize nucleus architecture. These filaments can be observed under the microscope thanks to fluorophore-conjugated phalloidin staining. In somatic cell nuclei, however, actin filaments cannot be observed using this technique. The DNase I inhibition assay, the only test which allows the quantification of the polymerized actin directly in biological samples, has revealed that endogenous nuclear actin indeed occurs mainly in a monomeric form. Precisely controlled level of actin in the cell nucleus, lower than in the cytoplasm, prevents the formation of filaments. The polymerization is also reduced by the limited access to actin monomers, which are bound in complexes with ABPs, mainly cofilin.Actin isoforms

Different isoforms of actin are present in the cell nucleus. The level of actin isoforms may change in response to stimulation of cell growth or arrest of proliferation and transcriptional activity. Research on nuclear actin is focused on isoform beta. However the use of antibodies directed against different actin isoforms allows identifying not only the cytoplasmic beta in the cell nucleus, but also alpha- and gamma-actin in certain cell types. The presence of different isoforms of actin may have a significant effect on its function in nuclear processes, as the level of individual isoforms can be controlled independently.Functions

Functions of actin in the nucleus are associated with its ability to polymerize and interact with various ABPs and with structural elements of the nucleus. Nuclear actin is involved in: * Architecture of the nucleus - Interaction of actin with alpha II-spectrin and other proteins are important for maintaining proper shape of the nucleus. * Transcription – Actin is involved in chromatin reorganization, transcription initiation and interaction with the transcription complex. Actin takes part in the regulation of chromatin structure, interacting with RNA polymerase I, II and III. In Pol I transcription, actin and myosin (MYO1C

Myosin-Ic is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ''MYO1C'' gene.

This gene encodes a member of the unconventional myosin protein family, which are actin-based molecular motors. The protein is found in the cytoplasm, and one isoform with a ...

, which binds DNA) act as a molecular motor

Molecular motors are natural (biological) or artificial molecular machines that are the essential agents of movement in living organisms. In general terms, a motor is a device that consumes energy in one form and converts it into motion or mech ...

. For Pol II transcription, β-actin is needed for the formation of the preinitiation complex. Pol III contains β-actin as a subunit. Actin can also be a component of chromatin remodelling complexes as well as pre-mRNP particles (that is, precursor messenger RNA

In molecular biology, messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) is a single-stranded molecule of RNA that corresponds to the genetic sequence of a gene, and is read by a ribosome in the process of synthesizing a protein.

mRNA is created during the ...

bundled in proteins), and is involved in nuclear export of RNAs and proteins.

* Regulation of gene activity – Actin binds to the regulatory regions of different kinds of genes. Actin's ability to regulate gene activity is used in the molecular reprogramming method, which allows differentiated cells return to their embryonic state.

* Translocation of the activated chromosome fragment from under membrane region to euchromatin where transcription starts. This movement requires the interaction of actin and myosin.

* Integration of different cellular compartments. Actin is a molecule that integrates cytoplasmic and nuclear signal transduction pathways. An example is the activation of transcription in response to serum stimulation of cells ''in vitro''.

* Immune response - Nuclear actin polymerizes upon T-cell receptor

The T-cell receptor (TCR) is a protein complex, located on the surface of T cells (also called T lymphocytes). They are responsible for recognizing fragments of antigen as peptides bound to major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules. ...

stimulation and is required for cytokine expression and antibody production ''in vivo''.

* DNA repair - Nuclear actin mediates the repair of DNA double-strand breaks. In the cell nucleus

The cell nucleus (; : nuclei) is a membrane-bound organelle found in eukaryote, eukaryotic cell (biology), cells. Eukaryotic cells usually have a single nucleus, but a few cell types, such as mammalian red blood cells, have #Anucleated_cells, ...

, a filamentous polymer of actin (F-actin) acts both in the DNA repair pathway of non homologous end joining and in the pathway of homologous recombinational repair.

Due to its ability to undergo conformational changes and interaction with many proteins, actin acts as a regulator of formation and activity of protein complexes such as transcriptional complex.

Cell movement

Actin is also involved in cell movement. Several different types of protrusions mediated directly or indirectly by actin are involved in cell migration in different ways, with the most important ones beinglamellipodia

The lamellipodium (: lamellipodia) (from Latin ''lamella'', related to ', "thin sheet", and the Greek radical ''pod-'', "foot") is a cytoskeletal protein actin projection on the leading edge of the cell. It contains a quasi-two-dimensional act ...

, filopodia

Filopodia (: filopodium) are slender cytoplasmic projections that extend beyond the leading edge of lamellipodia in migrating cells. Within the lamellipodium, actin ribs are known as ''microspikes'', and when they extend beyond the lamellipod ...

, invadopodia

Invadopodia are actin-rich protrusions of the plasma membrane that are associated with degradation of the extracellular matrix in cancer invasiveness and metastasis. Very similar to podosomes, invadopodia are found in invasive cancer cells and are ...

and blebs.

Lamellipodia

A meshwork of actin filaments marks the forward edge of a moving cell, and the polymerization of new actin filaments pushes the cell membrane forward in protrusions calledlamellipodia

The lamellipodium (: lamellipodia) (from Latin ''lamella'', related to ', "thin sheet", and the Greek radical ''pod-'', "foot") is a cytoskeletal protein actin projection on the leading edge of the cell. It contains a quasi-two-dimensional act ...

. These membrane protrusions then attach to the substrate, forming structures known as focal adhesions

In cell biology, focal adhesions (also cell–matrix adhesions or FAs) are large macromolecular assemblies through which mechanical force and regulatory signals are transmitted between the extracellular matrix (ECM) and an interacting cell. Mor ...

that connect to the actin network. Once attached, the rear of the cell body contracts squeezing its contents forward past the adhesion point. Once the adhesion point has moved to the rear of the cell, the cell disassembles it, allowing the rear of the cell to move forward.

Filopodia

Filopodia

Filopodia (: filopodium) are slender cytoplasmic projections that extend beyond the leading edge of lamellipodia in migrating cells. Within the lamellipodium, actin ribs are known as ''microspikes'', and when they extend beyond the lamellipod ...

are thin extensions of the plasma membrane that contain parallel bundles of actin filaments, in contrast to the branched actin structures of lamellipodia. They serve an exploratory role, being used by cells to probe their environment. While the presence of filopodia is linked to enhanced cell migration, they are not directly involved in cell body displacement.

Invadopodia

Invadopodia

Invadopodia are actin-rich protrusions of the plasma membrane that are associated with degradation of the extracellular matrix in cancer invasiveness and metastasis. Very similar to podosomes, invadopodia are found in invasive cancer cells and are ...

are actin-driven membrane protrusions that help to degrade the extracellular matrix. They are used by cancer cells for cell invasion, particularly to help them cross the basement membrane. The matrix degradation takes place by transporting vesicles containing matrix-degrading proteins to the invadopodia where the proteins are released via exocytosis.

Blebs

Blebs are spherical membrane protrusions that are involved in both apoptosis and cell movement. The driving force behind bleb extension is hydrostatic pressure, rather than actin filament elongation which drives lamellipodia, filopodia and invadopodia extension. Blebs are formed by actomyosin contraction, which causes the delamination of the plasma membrane from the actin cortex or a focal rupture of the actin cortex. They are then stabilized via actin cortex reassembly and finally retracted via actomyosin contraction. In migrating cells a front-rear polarity is established, with bleb formation restricted to the leading edge, allowing for directed movement.

Actin/myosin movement

In addition to the physical force generated by actin polymerization, microfilaments facilitate the movement of various intracellular components by serving as the roadway along which a family ofmotor protein

Motor proteins are a class of molecular motors that can move along the cytoskeleton of cells. They do this by converting chemical energy into mechanical work by the hydrolysis of ATP.

Cellular functions

Motor proteins are the driving force b ...

s called myosin

Myosins () are a Protein family, family of motor proteins (though most often protein complexes) best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are adenosine triphosphate, ATP- ...

s travel.

Muscle contraction

myosin II

Myosins () are a family of motor proteins (though most often protein complexes) best known for their roles in muscle contraction and in a wide range of other motility processes in eukaryotes. They are ATP-dependent and responsible for actin-ba ...

. Each repeated unit – called a sarcomere

A sarcomere (Greek σάρξ ''sarx'' "flesh", μέρος ''meros'' "part") is the smallest functional unit of striated muscle tissue. It is the repeating unit between two Z-lines. Skeletal striated muscle, Skeletal muscles are composed of tubular ...

– consists of two sets of oppositely oriented F-actin strands ("thin filaments"), interlaced with bundles of myosin ("thick filaments"). The two sets of actin strands are oriented with their (+) ends embedded in either end of the sarcomere in delimiting structures called Z-disk

A sarcomere (Greek σάρξ ''sarx'' "flesh", μέρος ''meros'' "part") is the smallest functional unit of striated muscle tissue. It is the repeating unit between two Z-lines. Skeletal striated muscle, Skeletal muscles are composed of tubular ...

s. The myosin fibrils are in the middle between the sets of actin filaments, with strands facing in both directions. When the muscle contracts, the myosin threads move along the actin filaments towards the (+) end, pulling the ends of the sarcomere together and shortening it by around 70% of its length. In order to move along the actin thread, myosin must hydrolyze ATP; thus ATP serves as the energy source for muscle contraction.

At times of rest, the proteins tropomyosin

Tropomyosin is a two-stranded alpha-helical, coiled coil protein found in many animal and fungal cells. In animals, it is an important component of the muscular system which works in conjunction with troponin to regulate muscle contraction. It ...

and troponin

Troponin, or the troponin complex, is a complex of three regulatory proteins (troponin C, troponin I, and troponin T) that are integral to muscle contraction in skeletal muscle and cardiac muscle, but not smooth muscle. Measurements of cardiac-spe ...

bind to the actin filaments, preventing the attachment of myosin. When an activation signal (i.e. an action potential

An action potential (also known as a nerve impulse or "spike" when in a neuron) is a series of quick changes in voltage across a cell membrane. An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific Cell (biology), cell rapidly ri ...

) arrives at the muscle fiber, it triggers the release of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum

The sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) is a membrane-bound structure found within muscle cells that is similar to the smooth endoplasmic reticulum in other cells. The main function of the SR is to store calcium ions (Ca2+). Calcium ion levels are kep ...

into the cytosol. The resulting spike in cytosolic calcium rapidly releases tropomyosin and troponin from the actin thread, allowing myosin to bind, and muscle contracation to begin.

Cell division

In the final stages ofcell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell (biology), cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukar ...

, many cells form a ring of actin at the cell's midpoint. This ring, aptly called the "contractile ring

In molecular biology, an actomyosin ring or contractile ring, is a prominent structure during cytokinesis. It forms perpendicular to the axis of the spindle apparatus towards the end of telophase, in which sister chromatids are identically separ ...

", uses a similar mechanism as muscle fibers where myosin II pulls along the actin ring, causing it to contract. This contraction cleaves the parent cell into two, completing cytokinesis

Cytokinesis () is the part of the cell division process and part of mitosis during which the cytoplasm of a single eukaryotic cell divides into two daughter cells. Cytoplasmic division begins during or after the late stages of nuclear division ...

. The contractile ring is composed of actin, myosin, anillin, and α-actinin. In the fission yeast ''Schizosaccharomyces pombe

''Schizosaccharomyces pombe'', also called "fission yeast", is a species of yeast used in traditional brewing and as a model organism in molecular and cell biology. It is a unicellular eukaryote, whose cells are rod-shaped. Cells typically meas ...

'', actin is actively formed in the constricting ring with the participation of Arp3, the formin

Formins (formin homology proteins) are a group of proteins that are involved in the polymerization of actin and associate with the fast-growing end (barbed end) of actin filaments. Most formins are Rho-GTPase effector proteins. Formins re ...

Cdc12, profilin

Profilin is an actin-binding protein involved in the dynamic turnover and reconstruction of the actin cytoskeleton. It is found in most eukaryotic organisms. Profilin is important for spatially and temporally controlled growth of actin microfila ...

, and WASp

A wasp is any insect of the narrow-waisted suborder Apocrita of the order Hymenoptera which is neither a bee nor an ant; this excludes the broad-waisted sawflies (Symphyta), which look somewhat like wasps, but are in a separate suborder ...

, along with preformed microfilaments. Once the ring has been constructed the structure is maintained by a continual assembly and disassembly that, aided by the Arp2/3

Arp2/3 complex (Actin Related Protein 2/3 complex) is a seven-subunit protein complex that plays a major role in the regulation of the actin cytoskeleton. It is a major component of the actin cytoskeleton and is found in most actin cytoskeleton ...

complex and formins, is key to one of the central processes of cytokinesis.

Intracellular trafficking

Actin-myosin pairs can also participate in the trafficking of variousmembrane vesicle

A membrane is a selective barrier; it allows some things to pass through but stops others. Such things may be molecules, ions, or other small particles. Membranes can be generally classified into synthetic membranes and biological membranes. Bi ...

s and organelle

In cell biology, an organelle is a specialized subunit, usually within a cell (biology), cell, that has a specific function. The name ''organelle'' comes from the idea that these structures are parts of cells, as Organ (anatomy), organs are to th ...

s within the cell. Myosin V is activated by binding to various cargo receptors on organelles, and then moves along an actin filament towards the (+) end, pulling its cargo along with it.

These nonconventional myosins use ATP hydrolysis to transport cargo, such as vesicles

Vesicle may refer to:

; In cellular biology or chemistry

* Vesicle (biology and chemistry), a supramolecular assembly of lipid molecules, like a cell membrane

* Synaptic vesicle

In a neuron, synaptic vesicles (or neurotransmitter vesicles) s ...

and organelles, in a directed fashion much faster than diffusion. Myosin V walks towards the barbed end of actin filaments, while myosin VI walks toward the pointed end. Most actin filaments are arranged with the barbed end toward the cellular membrane and the pointed end toward the cellular interior. This arrangement allows myosin V to be an effective motor for the export of cargos, and myosin VI to be an effective motor for import.

Other biological processes

The traditional image of actin's function relates it to the maintenance of the cytoskeleton and, therefore, the organization and movement of organelles, as well as the determination of a cell's shape. However, actin has a wider role in eukaryotic cell physiology, in addition to similar functions inprokaryote

A prokaryote (; less commonly spelled procaryote) is a unicellular organism, single-celled organism whose cell (biology), cell lacks a cell nucleus, nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Ancient Gree ...

s.

* Apoptosis

Apoptosis (from ) is a form of programmed cell death that occurs in multicellular organisms and in some eukaryotic, single-celled microorganisms such as yeast. Biochemistry, Biochemical events lead to characteristic cell changes (Morphology (biol ...

. During programmed cell death

Programmed cell death (PCD) sometimes referred to as cell, or cellular suicide is the death of a cell (biology), cell as a result of events inside of a cell, such as apoptosis or autophagy. PCD is carried out in a biological process, which usual ...

the ICE/ced-3 family of proteases (one of the interleukin-1β-converter proteases) degrade actin into two fragments ''in vivo''; one of the fragments is 15 kDa and the other 31 kDa. This represents one of the mechanisms involved in destroying cell viability that form the basis of apoptosis. The protease calpain

A calpain (; , ) is a protein belonging to the family of calcium-dependent, non-lysosomal cysteine proteases ( proteolytic enzymes) expressed ubiquitously in mammals and many other organisms. Calpains constitute the C2 family of protease clan C ...

has also been shown to be involved in this type of cell destruction; just as the use of calpain inhibitors has been shown to decrease actin proteolysis and the degradation of DNA

Deoxyribonucleic acid (; DNA) is a polymer composed of two polynucleotide chains that coil around each other to form a double helix. The polymer carries genetic instructions for the development, functioning, growth and reproduction of al ...

(another of the characteristic elements of apoptosis). On the other hand, the stress-induced triggering of apoptosis causes the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton (which also involves its polymerization), giving rise to structures called stress fiber

Stress fibers are contractile actin bundles found in non-muscle cells. They are composed of actin (microfilaments) and non-muscle myosin II (NMMII), and also contain various crosslinking proteins, such as α-actinin, to form a highly regulated ...

s; this is activated by the MAP kinase

A mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK or MAP kinase) is a type of serine/threonine-specific protein kinases involved in directing cellular responses to a diverse array of stimuli, such as mitogens, osmotic stress, heat shock and proinflammato ...

pathway.

Cellular adhesion

Cell adhesion is the process by which cells interact and attach to neighbouring cells through specialised molecules of the cell surface. This process can occur either through direct contact between cell surfaces such as Cell_junction, cell junc ...

and development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development (music), the process by which thematic material is reshaped

* Photographic development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

* Development hell, when a proje ...

. The adhesion between cells is a characteristic of multicellular organisms

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, unlike unicellular organisms. All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially uni- and pa ...

that enables tissue specialization and therefore increases cell complexity. Adhesion of cell epithelia

Epithelium or epithelial tissue is a thin, continuous, protective layer of cells with little extracellular matrix. An example is the epidermis, the outermost layer of the skin. Epithelial ( mesothelial) tissues line the outer surfaces of many ...

involves the actin cytoskeleton in each of the joined cells as well as cadherin

Cadherins (named for "calcium-dependent adhesion") are cell adhesion molecules important in forming adherens junctions that let cells adhere to each other. Cadherins are a class of type-1 transmembrane proteins, and they depend on calcium (Ca2+) ...

s acting as extracellular elements with the connection between the two mediated by catenin

Catenins are a family of proteins found in complexes with cadherin cell adhesion molecules of animal cells. The first two catenins that were identified became known as α-catenin and β-catenin. α-Catenin can bind to β-catenin and can also bi ...

s. Interfering in actin dynamics has repercussions for an organism's development, in fact actin is such a crucial element that systems of redundant gene

In biology, the word gene has two meanings. The Mendelian gene is a basic unit of heredity. The molecular gene is a sequence of nucleotides in DNA that is transcribed to produce a functional RNA. There are two types of molecular genes: protei ...

s are available. For example, if the α-actinin or gelation

In polymer chemistry, gelation (gel transition) is the formation of a gel from a system with polymers. Branched polymers can form links between the chains, which lead to progressively larger polymers. As the linking continues, larger branched p ...

factor gene has been removed in ''Dictyostelium

''Dictyostelium'' is a genus of single- and multi-celled eukaryotic, phagotrophic bacterivores. Though they are Protista and in no way fungal, they traditionally are known as "slime molds". They are present in most terrestrial ecosystems a ...

'' individuals do not show an anomalous phenotype

In genetics, the phenotype () is the set of observable characteristics or traits of an organism. The term covers the organism's morphology (physical form and structure), its developmental processes, its biochemical and physiological propert ...

possibly due to the fact that each of the proteins can perform the function of the other. However, the development of double mutations that lack both gene types is affected.

* Gene expression

Gene expression is the process (including its Regulation of gene expression, regulation) by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product that enables it to produce end products, proteins or non-coding RNA, ...

modulation. Actin's state of polymerization affects the pattern of gene expression