Diplobune on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Diplobune'' (

In 1862, Swiss palaeontologist

In 1862, Swiss palaeontologist

In 1883, Max Schlosser made ''Eurytherium'' a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' because he argued that the limb anatomies and dentitions were specific differences in characteristics rather than major ones that defined an entire genus. Sclosser pointed out that all species of ''Anoplotherium'' in some form had three indexes despite ''A. commune'' having less developed third indexes than ''A. latipes''. As a result, ''Diplobune'' became the senior synonym for the species ''D. bavaricum'', ''D. modicum'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minus''. He also mentioned that ''D. modicum'' was similar to ''D. bavaricum'' with the differences lying in specific dental characteristics. Schlosser noticed that ''A. secundarium'' appeared to have been related to ''Diplobune'' that he considered it "almost advisable" to reclassify it to the genus.

In 1885, Lydekker synonymized ''Diplobune'' with ''Anoplotherium'' because he felt that differences in the lower dentition were not worthy of generic distinctions, transferring species of the former genus to the latter genus. He also named a new species ''A. cayluxense''. The demotion of ''Diplobune'' as a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' was not followed by subsequent authors, however, as they recognized it as a valid genus. Also, von Zittel synonymized ''Plesidacrytherium'' and '' Mixtotherium'' with ''Diplobune'' in 1891–1893, but

In 1883, Max Schlosser made ''Eurytherium'' a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' because he argued that the limb anatomies and dentitions were specific differences in characteristics rather than major ones that defined an entire genus. Sclosser pointed out that all species of ''Anoplotherium'' in some form had three indexes despite ''A. commune'' having less developed third indexes than ''A. latipes''. As a result, ''Diplobune'' became the senior synonym for the species ''D. bavaricum'', ''D. modicum'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minus''. He also mentioned that ''D. modicum'' was similar to ''D. bavaricum'' with the differences lying in specific dental characteristics. Schlosser noticed that ''A. secundarium'' appeared to have been related to ''Diplobune'' that he considered it "almost advisable" to reclassify it to the genus.

In 1885, Lydekker synonymized ''Diplobune'' with ''Anoplotherium'' because he felt that differences in the lower dentition were not worthy of generic distinctions, transferring species of the former genus to the latter genus. He also named a new species ''A. cayluxense''. The demotion of ''Diplobune'' as a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' was not followed by subsequent authors, however, as they recognized it as a valid genus. Also, von Zittel synonymized ''Plesidacrytherium'' and '' Mixtotherium'' with ''Diplobune'' in 1891–1893, but

''Diplobune'' belongs to the Anoplotheriidae, a

''Diplobune'' belongs to the Anoplotheriidae, a

Skull materials of ''Diplobune'' are well known for multiple species, including one of ''D. minor'' uncovered between 1972 and 1975 in the

Skull materials of ''Diplobune'' are well known for multiple species, including one of ''D. minor'' uncovered between 1972 and 1975 in the

In 1928, palaeoneurologist

In 1928, palaeoneurologist

Unlike typical "even-toed" artiodactyls and ''Anoplotherium'' where one species (''A. commune'') is didactyl (two-toed) as opposed to all other species which are tridactyl (three-toed), all species of ''Diplobune'' are tridactyl. Multiple limb fossils are known from ''D. secundaria'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minor''. ''Diplobune'' is thought to be semi-

Unlike typical "even-toed" artiodactyls and ''Anoplotherium'' where one species (''A. commune'') is didactyl (two-toed) as opposed to all other species which are tridactyl (three-toed), all species of ''Diplobune'' are tridactyl. Multiple limb fossils are known from ''D. secundaria'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minor''. ''Diplobune'' is thought to be semi-

The weight estimates of ''D. bavarica'' and ''D. quercyi'' have not been offered in any recent study on ''Diplobune'', while ''D. minor'' has been subjected to a few weight estimate studies. ''D. minor'' has long been suggested to have been the smallest species of its genus since at least 1982. This has been proven in 1995 when Jean-Noël Martinez and Sudre made weight estimates of Palaeogene artiodactyls based on the dimensions of their astragali and M1 teeth. The astragali are common bones in fossil assemblages due to their reduced vulnerability to fragmentation as a result of their stocky shape and compact structure, explaining their choice for using it. The two weight estimates for ''D. minor'' from the locality of Itardies (MP23) yielded different results, with the M1 giving the body mass of and the astragalus yielding . These weight estimates were larger than several other artiodactyls in the study but were also smaller than many others. The two researchers considered that the estimated body mass of ''D. minor'' based on the M1 area is a slight underestimate compared to that of the astragalus.

In 2014, Takehisa Tsubamoto reexamined the relationship between astragalus size and estimated body mass based on extensive studies of extant terrestrial mammals, reapplying the methods to Palaeogene artiodactyls previously tested by Sudre and Martinez. The researcher used linear measurements and their products with adjusted correction factors. Compared to most other artiodactyl estimates, the recalculated body mass of ''D. minor'' was slightly higher, the previous underestimates possibly being the result of a shorter astragalus proportion than most other artiodactyls. The results of the body mass estimates of ''D. minor'' and other Palaeogene artiodactyls are displayed in the below graph:

The weight estimates of ''D. bavarica'' and ''D. quercyi'' have not been offered in any recent study on ''Diplobune'', while ''D. minor'' has been subjected to a few weight estimate studies. ''D. minor'' has long been suggested to have been the smallest species of its genus since at least 1982. This has been proven in 1995 when Jean-Noël Martinez and Sudre made weight estimates of Palaeogene artiodactyls based on the dimensions of their astragali and M1 teeth. The astragali are common bones in fossil assemblages due to their reduced vulnerability to fragmentation as a result of their stocky shape and compact structure, explaining their choice for using it. The two weight estimates for ''D. minor'' from the locality of Itardies (MP23) yielded different results, with the M1 giving the body mass of and the astragalus yielding . These weight estimates were larger than several other artiodactyls in the study but were also smaller than many others. The two researchers considered that the estimated body mass of ''D. minor'' based on the M1 area is a slight underestimate compared to that of the astragalus.

In 2014, Takehisa Tsubamoto reexamined the relationship between astragalus size and estimated body mass based on extensive studies of extant terrestrial mammals, reapplying the methods to Palaeogene artiodactyls previously tested by Sudre and Martinez. The researcher used linear measurements and their products with adjusted correction factors. Compared to most other artiodactyl estimates, the recalculated body mass of ''D. minor'' was slightly higher, the previous underestimates possibly being the result of a shorter astragalus proportion than most other artiodactyls. The results of the body mass estimates of ''D. minor'' and other Palaeogene artiodactyls are displayed in the below graph:

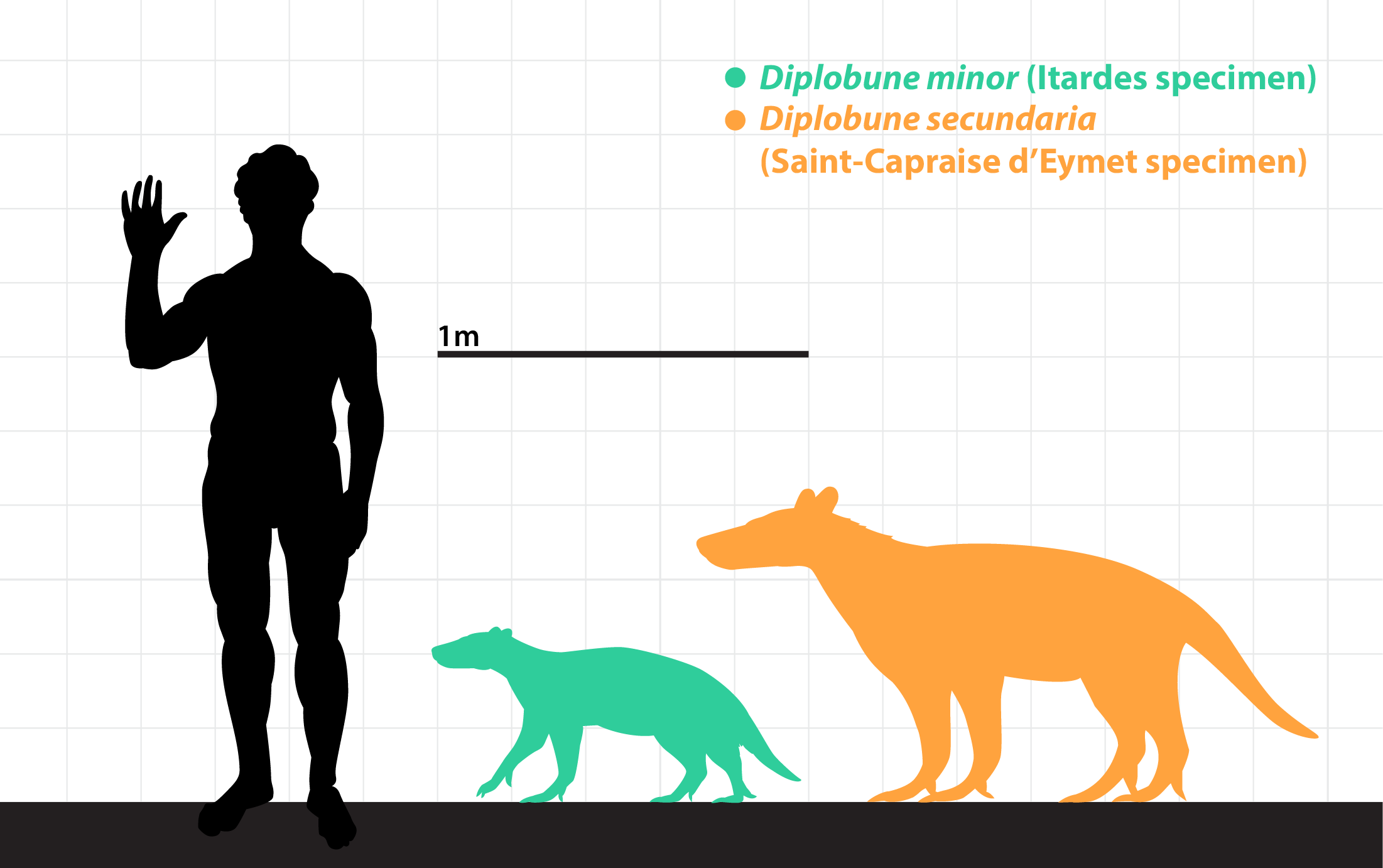

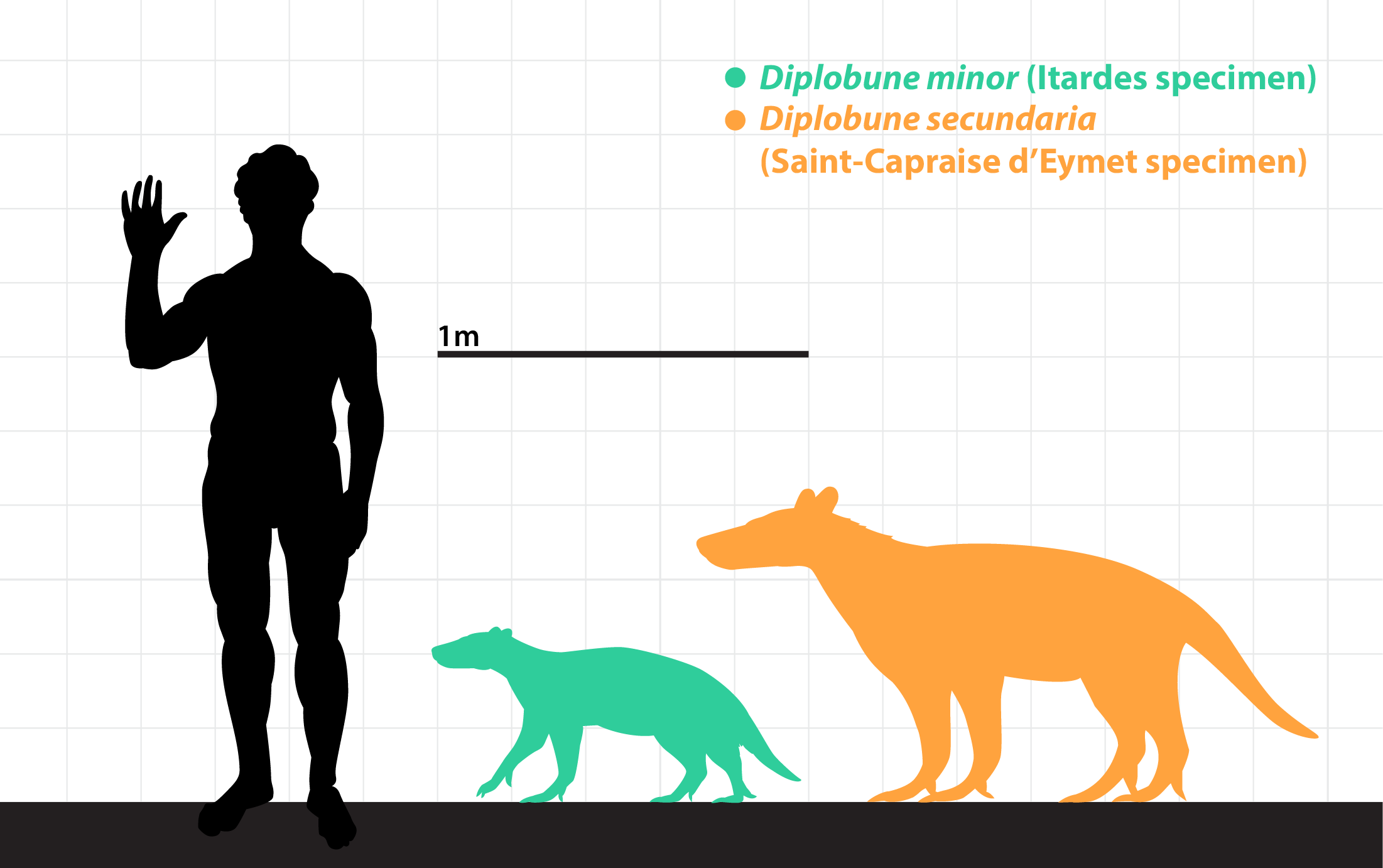

Maeva J. Orliac et al. suggested in 2017 that the mean body mass of ''D. minor'' based on five astragali from Itardies that belong to the species is . Based on a slightly deformed but complete cranium specimen UM ITD 43, which measures , the estimated body mass is . The mean of the two body mass estimates is . In 2022, Weppe determined based on a body mass formula that ''D. secundaria'', while not as massive as ''A. commune'' in weight, was a large herbivore that weighed approximately .

Cyril Gagnaison and Jean-Jacques Leroux suggested that based on the ''D. secundaria'' skull from Saint-Capraise-d'Eymet, the size of the individual would have been approximately in length and in height up to the

Maeva J. Orliac et al. suggested in 2017 that the mean body mass of ''D. minor'' based on five astragali from Itardies that belong to the species is . Based on a slightly deformed but complete cranium specimen UM ITD 43, which measures , the estimated body mass is . The mean of the two body mass estimates is . In 2022, Weppe determined based on a body mass formula that ''D. secundaria'', while not as massive as ''A. commune'' in weight, was a large herbivore that weighed approximately .

Cyril Gagnaison and Jean-Jacques Leroux suggested that based on the ''D. secundaria'' skull from Saint-Capraise-d'Eymet, the size of the individual would have been approximately in length and in height up to the

Based on agility scores employed for animal locomotion, ranging from 1 as extra slow to 6 as fast, ''D. minor'' best fitted in the Category 2 (slow) to Category 3 (medium slow) range of agility scores. Although it is not possible to eliminate it from the Category 1 score (extremely slow like sloths), the lack of variability of inner ear morphologies compared to tragulids suggest unlikeliness of such low speed. ''D. minor'' was definitely not a fast-moving animal, however, consistent with its postcranial morphology. Its ear morphology and measurements compared to other artiodactyls do suggest that its locomotion was distinct and peculiar. An aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle is eliminated as an option for ''Diplobune'' as a result of its ear morphology, currently leaving arborealism/semi-arborealism as the main suggested lifestyle of ''Diplobune''.

The elongated shapes of the nasal bones of at least ''D. secundaria'' suggest that it had a long, tapered tongue similar to

Based on agility scores employed for animal locomotion, ranging from 1 as extra slow to 6 as fast, ''D. minor'' best fitted in the Category 2 (slow) to Category 3 (medium slow) range of agility scores. Although it is not possible to eliminate it from the Category 1 score (extremely slow like sloths), the lack of variability of inner ear morphologies compared to tragulids suggest unlikeliness of such low speed. ''D. minor'' was definitely not a fast-moving animal, however, consistent with its postcranial morphology. Its ear morphology and measurements compared to other artiodactyls do suggest that its locomotion was distinct and peculiar. An aquatic or semi-aquatic lifestyle is eliminated as an option for ''Diplobune'' as a result of its ear morphology, currently leaving arborealism/semi-arborealism as the main suggested lifestyle of ''Diplobune''.

The elongated shapes of the nasal bones of at least ''D. secundaria'' suggest that it had a long, tapered tongue similar to

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and

For much of the Eocene, a hothouse climate with humid, tropical environments with consistently high precipitations prevailed. Modern mammalian orders including the Perissodactyla, Artiodactyla, and

After a considerable gap in anoplotheriine fossils in MP17a and MP17b, the derived anoplotheriines ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' made their first known appearances in the MP18 unit. They were exclusive to the western European archipelago, but their exact origins and dispersal routes are unknown. By then, ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' lived in Central Europe (then an island) and the Iberian Peninsula, only the former genus of which later dispersed into southern England by MP19 due to the apparent lack of ocean barriers.

''Diplobune'' coexisted with a wide diversity of artiodactyls in western Europe by MP18, ranging from the more widespread

After a considerable gap in anoplotheriine fossils in MP17a and MP17b, the derived anoplotheriines ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' made their first known appearances in the MP18 unit. They were exclusive to the western European archipelago, but their exact origins and dispersal routes are unknown. By then, ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' lived in Central Europe (then an island) and the Iberian Peninsula, only the former genus of which later dispersed into southern England by MP19 due to the apparent lack of ocean barriers.

''Diplobune'' coexisted with a wide diversity of artiodactyls in western Europe by MP18, ranging from the more widespread

The

The

As a result of the Grande Coupure, there are few post-Grande Coupure sites that contain any anoplotheriid. The only anoplotheriid genus with guaranteed survival was ''Diplobune'', with the stratigraphic range of ''Ephelcomenus'' being still unresolved. The last species of ''Diplobune'' was ''D. minor'' with the latest temporal range of MP22-MP23. ''D. minor'' is known from the localities of Calaf in Spain (MP22) and Itardies in France (MP23).

In the former, ''D. minor'' was found with the herpetotheriid ''Peratherium'', theridomyid ''Theridomys'', anoplotheriid ''Ephelcomenus''(?), and the anthracothere ''

As a result of the Grande Coupure, there are few post-Grande Coupure sites that contain any anoplotheriid. The only anoplotheriid genus with guaranteed survival was ''Diplobune'', with the stratigraphic range of ''Ephelcomenus'' being still unresolved. The last species of ''Diplobune'' was ''D. minor'' with the latest temporal range of MP22-MP23. ''D. minor'' is known from the localities of Calaf in Spain (MP22) and Itardies in France (MP23).

In the former, ''D. minor'' was found with the herpetotheriid ''Peratherium'', theridomyid ''Theridomys'', anoplotheriid ''Ephelcomenus''(?), and the anthracothere ''

Ancient Greek

Ancient Greek (, ; ) includes the forms of the Greek language used in ancient Greece and the classical antiquity, ancient world from around 1500 BC to 300 BC. It is often roughly divided into the following periods: Mycenaean Greek (), Greek ...

: (double) + (hill) meaning "double hill") is an extinct genus of Palaeogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

artiodactyl

Artiodactyls are placental mammals belonging to the order Artiodactyla ( , ). Typically, they are ungulates which bear weight equally on two (an even number) of their five toes (the third and fourth, often in the form of a hoof). The other t ...

s belonging to the family Anoplotheriidae

Anoplotheriidae is an extinct family of artiodactyl ungulates. They were endemic to Europe during the Eocene and Oligocene epochs about 44—30 million years ago. Its name is derived from the ("unarmed") and θήριον ("beast"), translating ...

. It was endemic to Europe and lived from the late Eocene

The Eocene ( ) is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (Ma). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene'' comes ...

to the early Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch (geology), epoch of the Paleogene Geologic time scale, Period that extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that defin ...

. The genus was first erected as a subgenus

In biology, a subgenus ( subgenera) is a taxonomic rank directly below genus.

In the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature, a subgeneric name can be used independently or included in a species name, in parentheses, placed between the ge ...

of ''Dichobune

''Dichobune'' is the type genus of the Dichobunoidea, an extinct paraphyletic superfamily consisting of some of the earliest artiodactyls known in the fossil record. It was a primitive artiodactyl genus that was endemic to western Europe and live ...

'' by Ludwig Rütimeyer

(Karl) Ludwig Rütimeyer (26 February 1825 in Biglen, Canton of Bern – 25 November 1895 in Basel) was a Swiss zoologist, anatomist and paleontologist, who is considered one of the fathers of zooarchaeology.

Career

Rütimeyer studied at the Univ ...

in 1862 based on his hypothesis of the taxon being a transitional form

A transitional fossil is any fossilized remains of a life form that exhibits traits common to both an ancestral group and its derived descendant group. This is especially important where the descendant group is sharply differentiated by gross ...

between "''Anoplotherium

''Anoplotherium'' is the type genus of the extinct Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyl family Anoplotheriidae, which was endemic to Western Europe. It lived from the Late Eocene to the earliest Oligocene. It was the fifth fossil mammal genus to be ...

''" secundaria, previously erected by Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

in 1822, and ''Dichobune''. He based the genus etymology off of the two-pointed pillarlike shapes of the lower molars, which had since been a diagnosis of it. However, in 1870, ''Diplobune'' was elevated to genus rank by Oscar Fraas

Oscar Friedrich von Fraas (17 January 1824 in Lorch (Württemberg) – 22 November 1897 in Stuttgart) was a German clergyman, paleontologist and geologist. He was the father of geologist Eberhard Fraas (1862–1915).

Biography

He studied theol ...

, who recognized that ''Diplobune'' was a distinct genus related to ''Anoplotherium'' and not ''Dichobune''. After several revisions of the anoplotheriids, there are currently four known species of which ''D. minor'' is the type species

In International_Code_of_Zoological_Nomenclature, zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the spe ...

.

''Diplobune'' was an evolutionarily derived medium to large-sized anoplotheriid with shared similarities to the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

''Anoplotherium''; the differences mainly consisting of all species having specialized three-fingered limbs and various specific dental, postcranial, and brain anatomy differences. It was well-adapted for purely folivorous diets, with dentition capable of chewing through hard leaf material and an implied presence of tapered tongues for reaching branches similar to modern-day giraffid

The Giraffidae are a family of ruminant artiodactyl mammals that share a recent common ancestor with deer and bovids. This family, once a diverse group spread throughout Eurasia and Africa, presently comprises only two extant genera, the giraffe ...

s. Its limbs were very specialized of which there are no modern analogues, especially in artiodactyls, with implied powerful muscles for some extent of mobility in the form of bending its fingers, especially its left, shortest finger (finger II).

Such unique traits along with hints of slow-walking locomotion suggest a life of arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally (scansorial), but others are exclusively arboreal. The hab ...

ism or semi-arborealism, where it was likely able to grasp onto hard objects for climbing them. These traits would have set it apart in lifestyle from ''Anoplotherium'', the Palaeotheriidae

Palaeotheriidae is an extinct family of herbivorous perissodactyl mammals that inhabited Europe, with less abundant remains also known from Asia, from the mid-Eocene to the early Oligocene. They are classified in Equoidea, along with the livin ...

, and most other mammals that it coexisted with. Although the sizes of several species are not described, ''D. secundaria'' of the late Eocene was estimated to weigh approximately and measure about in length and in shoulder height, whereas ''D. minor'' of the early Oligocene was much smaller with estimated weights of .

The evolutionary history of ''Diplobune'' is not complete, but it lived in western Europe back when it was an archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

that was isolated from the rest of Eurasia, meaning that it lived in an environment with various other faunas that also evolved with strong levels of endemism. It, like ''Anoplotherium'', arose long after a shift towards drier but still subhumid conditions that led to abrasive plants and the extinctions of the large-sized Lophiodontidae

Lophiodontidae is a family of browsing, herbivorous, mammals in the Perissodactyla suborder Ancylopoda that show long, curved and cleft claws. They lived in Southern Europe during the Eocene epoch. Previously thought to be related to tapirs, it ...

, becoming a regular component of late Eocene faunal communities. It survived through the Grande Coupure

Grande means "large" or "great" in many of the Romance languages. It may also refer to:

Places

* Grande, Germany, a municipality in Germany

* Grande Communications, a telecommunications firm based in Texas

* Grande-Rivière (disambiguation)

* Ar ...

extinction event of western Europe in the earliest Oligocene but seemingly lost at least one species in the process. ''D. minor'' appeared in the early Oligocene as likely the last representative of the Anoplotheriidae, leaning towards specialization in forested, subhumid environments with freshwater bodies.

Taxonomy

Early History

In 1862, Swiss palaeontologist

In 1862, Swiss palaeontologist Ludwig Rütimeyer

(Karl) Ludwig Rütimeyer (26 February 1825 in Biglen, Canton of Bern – 25 November 1895 in Basel) was a Swiss zoologist, anatomist and paleontologist, who is considered one of the fathers of zooarchaeology.

Career

Rütimeyer studied at the Univ ...

discussed his hypothesis that ''Anoplotherium

''Anoplotherium'' is the type genus of the extinct Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyl family Anoplotheriidae, which was endemic to Western Europe. It lived from the Late Eocene to the earliest Oligocene. It was the fifth fossil mammal genus to be ...

secundarium'' was a transitional species

Transition or transitional may refer to:

Mathematics, science, and technology

Biology

* Transition (genetics), a point mutation that changes a purine nucleotide to another purine (A ↔ G) or a pyrimidine nucleotide to another pyrimidine (C ↔ ...

to the genus ''Dichobune

''Dichobune'' is the type genus of the Dichobunoidea, an extinct paraphyletic superfamily consisting of some of the earliest artiodactyls known in the fossil record. It was a primitive artiodactyl genus that was endemic to western Europe and live ...

''. He noticed that the inner mounds of the molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

of the studied species were distinctly bicuspid, the tips not being in equal size. Because of the molar morphologies being similar to those of both ''Dichobune'' and ''Anoplotherium'', he created the ''Dichobune'' subgenus ''Diplobune'', thinking that it was the subgenus that derived species of ''Dichobune'' descended from. Rütimeyer did not elaborate on which species belonged to the subgenus, however. While the etymology of ''Diplobune'' was not defined by Rütimeyer, it derives in Greek from "" (double) and "" (hill, usually referencing rounded cusps), meaning that the etymology of the genus name is "double hill."

However, the status of ''Diplobune'' as a subgenus of ''Dichobune'' did not last long. In 1870, German palaeontologist Oscar Fraas

Oscar Friedrich von Fraas (17 January 1824 in Lorch (Württemberg) – 22 November 1897 in Stuttgart) was a German clergyman, paleontologist and geologist. He was the father of geologist Eberhard Fraas (1862–1915).

Biography

He studied theol ...

wrote about a mammal with numerous remains from the locality of Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

, its molars being similar but not identical to ''A. commune'' in terms of typical species diagnoses. He noticed the bicuspid characteristic and assigned the fossil materials to ''Diplobune''. He also wrote that based on its dentition, ''Dichobune'' had no evolutionary relationship with the anoplotheriids, making ''Diplobune'' a distinct genus. Although Fraas was the sole author of his article, he credited his colleague Karl Alfred von Zittel

Karl Alfred Ritter von Zittel (25 September 1839 – 5 January 1904) was a German palaeontologist best known for his ''Handbuch der Palaeontologie'' (1876–1880).

Biography

Karl Alfred von Zittel was born in Bahlingen in the Grand Duchy ...

for the name ''D. bavaricum'', which the specimens belonged to.

Several species now attributed to ''Diplobune'' were historically not included in the genus initially due to either being erected far before the genus itself (''Anoplotherium secundarium'' by Georges Cuvier

Jean Léopold Nicolas Frédéric, baron Cuvier (23 August 1769 – 13 May 1832), known as Georges Cuvier (; ), was a French natural history, naturalist and zoology, zoologist, sometimes referred to as the "founding father of paleontology". Cuv ...

in 1822) or after. In 1877, Henri Filhol

Henri Filhol

Henri Filhol (13 May 1843 – 28 April 1902) was a French medical doctor, malacologist and naturalist born in Toulouse. He was the son of Édouard Filhol (1814-1883), curator of the Muséum de Toulouse.

After receiving his early e ...

reassigned ''A. secundarium'' to the genus ''Eurytherium'' on the genus diagnosis that it has three toes. He also made three species for the genus mostly based on dentition: ''E. modicum'', ''E. quercyi'', and ''E. minus''. Filhol also argued that ''Eurytherium'' took priority over ''Diplobune'' because he thought that the three-toed diagnosis takes priority over dental diagnoses.

Several genus names that would eventually become synonyms of ''Diplobune'' were created in the late 19th century. In 1876, Paul Gervais

Paul Gervais (full name: François Louis Paul Gervais) (26 September 1816 – 10 February 1879) was a French palaeontologist and entomologist.

Biography

Gervais was born in Paris, where he obtained the diplomas of doctor of science and of medic ...

named a newer genus ''Thylacomorphus'' based on skull that he thought to belong to an animal closely related to thylacine

The thylacine (; binomial name ''Thylacinus cynocephalus''), also commonly known as the Tasmanian tiger or Tasmanian wolf, was a carnivorous marsupial that was native to the Mainland Australia, Australian mainland and the islands of Tasmani ...

s, the type species being ''T. cristatus''. ''Thylacomorphus'' materials were later referred to the hyaenodont ''Cynohyaenodon

''Cynohyaenodon'' ("dog-like ''Hyaenodon''") is an extinct paraphyletic genus of placental mammals from extinct family Hyaenodontidae that lived from the early to middle Eocene in Europe

Europe is a continent located entirely in the North ...

'' by Max Schlosser. However, in 1901, William Diller Matthew

William Diller Matthew FRS (February 19, 1871 – September 24, 1930) was a vertebrate paleontologist who worked primarily on mammal fossils, although he also published a few early papers on mineralogy, petrological geology, one on botany, one on ...

determined that the back of the skull actually belonged to ''Diplobune quercyi''.

In the same year, Filhol created a genus "''Hyracodon''" ("hyrax

Hyraxes (), also called dassies, are small, stout, thickset, herbivorous mammals in the family Procaviidae within the order Hyracoidea. Hyraxes are well-furred, rotund animals with short tails. Modern hyraxes are typically between in length a ...

tooth") after he noticed that the species' teeth, originating from the locality of Caylux in Quercy

Quercy (; , locally ) is a former province of France located in the country's southwest, bounded on the north by Limousin, on the west by Périgord and Agenais, on the south by Gascony and Languedoc, and on the east by Rouergue and Auverg ...

, were similar to those of hyraxes, creating the type species ''H. primavus''. Filhol was apparently unaware that the genus name "''Hyracodon

''Hyracodon'' ('hyrax tooth') is an extinct genus of perissodactyl mammal.

It was a lightly built, pony-like mammal of about 1.5 m (5 ft) long. ''Hyracodons skull was large in comparison to the rest of the body. ''Hyracodon's'' dentiti ...

''" was already reserved by American palaeontologist Joseph Leidy

Joseph Mellick Leidy (September 9, 1823 – April 30, 1891) was an American paleontologist, parasitologist and anatomist.

Leidy was professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania, later becoming a professor of natural history at Swarth ...

in 1856 for a rhinocerotoid

Rhinocerotoidea is a superfamily (taxonomy), superfamily of Perissodactyla, perissodactyls that appeared 56 million years ago in the Paleocene. They included four extinct families, the Amynodontidae, the Hyracodontidae, the Paraceratheriidae, an ...

initially, later changing the genus name to ''Hyracodontherium'' in 1877. Filhol named another species ''H. crassum'' in 1882, and a third species ''H. filholi'' was named by Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was a British naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history. He was known for his contributions to zoology, paleontology, and biogeography. He worked extensively in cata ...

in 1889. The genus name was eventually synonymized with ''Diplobune'' by a palaeontological textbook in 1925 and Johannes Hürzeler in 1938, the latter noticing the similarities of the type species to the older genus. Hürzeler reclassified ''H. filholi'' to the new anoplotheriid genus ''Ephelcomenus

''Ephelcomenus'' is an extinct genus of Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyls belonging to the Anoplotheriidae that were endemic to Western Europe. It contains one species ''E. filholi'', which was first described by Richard Lydekker in 1889 but e ...

'' in 1938 and discussed about being unsure of the status of "''H. crassum''" since it was based on a fragment of a mandible that was only briefly described and not illustrated. "''H. crassum''" and "''H. primaevum''" were not directly invalidated in 1938 but have not been recognized as valid species since.

Anoplotheriidae revisions

In 1883, Max Schlosser made ''Eurytherium'' a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' because he argued that the limb anatomies and dentitions were specific differences in characteristics rather than major ones that defined an entire genus. Sclosser pointed out that all species of ''Anoplotherium'' in some form had three indexes despite ''A. commune'' having less developed third indexes than ''A. latipes''. As a result, ''Diplobune'' became the senior synonym for the species ''D. bavaricum'', ''D. modicum'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minus''. He also mentioned that ''D. modicum'' was similar to ''D. bavaricum'' with the differences lying in specific dental characteristics. Schlosser noticed that ''A. secundarium'' appeared to have been related to ''Diplobune'' that he considered it "almost advisable" to reclassify it to the genus.

In 1885, Lydekker synonymized ''Diplobune'' with ''Anoplotherium'' because he felt that differences in the lower dentition were not worthy of generic distinctions, transferring species of the former genus to the latter genus. He also named a new species ''A. cayluxense''. The demotion of ''Diplobune'' as a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' was not followed by subsequent authors, however, as they recognized it as a valid genus. Also, von Zittel synonymized ''Plesidacrytherium'' and '' Mixtotherium'' with ''Diplobune'' in 1891–1893, but

In 1883, Max Schlosser made ''Eurytherium'' a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' because he argued that the limb anatomies and dentitions were specific differences in characteristics rather than major ones that defined an entire genus. Sclosser pointed out that all species of ''Anoplotherium'' in some form had three indexes despite ''A. commune'' having less developed third indexes than ''A. latipes''. As a result, ''Diplobune'' became the senior synonym for the species ''D. bavaricum'', ''D. modicum'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minus''. He also mentioned that ''D. modicum'' was similar to ''D. bavaricum'' with the differences lying in specific dental characteristics. Schlosser noticed that ''A. secundarium'' appeared to have been related to ''Diplobune'' that he considered it "almost advisable" to reclassify it to the genus.

In 1885, Lydekker synonymized ''Diplobune'' with ''Anoplotherium'' because he felt that differences in the lower dentition were not worthy of generic distinctions, transferring species of the former genus to the latter genus. He also named a new species ''A. cayluxense''. The demotion of ''Diplobune'' as a synonym of ''Anoplotherium'' was not followed by subsequent authors, however, as they recognized it as a valid genus. Also, von Zittel synonymized ''Plesidacrytherium'' and '' Mixtotherium'' with ''Diplobune'' in 1891–1893, but Hans Georg Stehlin

Hans Georg Stehlin (1870–1941) was a Swiss paleontologist and geologist.

Stehlin specialized in vertebrate paleontology, particularly the study of Cenozoic mammals. He published numerous scientific papers on primates and ungulates. He was presid ...

in 1910 instead synonymized ''Plesidacrytherium'' with ''Dacrytherium

''Dacrytherium'' (Ancient Greek: (tear, teardrop) + (beast or wild animal) meaning "tear beast") is an extinct genus of Paleogene, Palaeogene artiodactyls belonging to the family Anoplotheriidae. It occurred from the Middle to Late Eocene of W ...

'' while revalidating ''Mixtotherium''.

The same year that he touched upon the two other genus names, Stehlin also argued that ''Diplobune'' was morphologically similar to ''Anoplotherium'' but were generically distinct from each other. The German palaeontologist reclassified ''Anoplotherium secundaria'' to ''Diplobune'' plus synonymized ''D. modicum''/''D. modica'' with ''D. bavarica'' and ''A. cayluxense'' with ''D. secundaria''. The synonymy of "''A. secundaria''" with ''D. secundaria'' was agreed upon by Marcellin Boule

Pierre-Marcellin Boule (1 January 1861 – 4 July 1942), better known as merely Marcellin Boule, was a French palaeontologist, geologist, and anthropologist.

Early life and education

Pierre-Marcellin Boule was born in Montsalvy, France.

Car ...

and Jean Piveteau

Jean Piveteau (23 September 1899 – 7 March 1991) was a distinguished French vertebrate paleontologist. He was elected to the French Academy of Sciences in 1956 and served as the institute's president in 1973.

Legacy

Two genera of Triassic f ...

in 1935.

Classification

''Diplobune'' belongs to the Anoplotheriidae, a

''Diplobune'' belongs to the Anoplotheriidae, a Palaeogene

The Paleogene Period ( ; also spelled Palaeogene or Palæogene) is a geologic period and system that spans 43 million years from the end of the Cretaceous Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the Neogene Period Ma. It is the fir ...

artiodactyl family endemic to western Europe that lived from the middle Eocene to the early Oligocene (~44 to 30 Ma, possible earliest record at ~48 Ma). The type species of the genus is ''D. minor'', first described long after the genus name was first created. The exact evolutionary origins and dispersals of the anoplotheriids are uncertain, but they exclusively resided within the continent when it was an archipelago

An archipelago ( ), sometimes called an island group or island chain, is a chain, cluster, or collection of islands. An archipelago may be in an ocean, a sea, or a smaller body of water. Example archipelagos include the Aegean Islands (the o ...

that was isolated by seaway barriers from other regions such as Balkanatolia

For some 10 million years until the end of the Eocene, Balkanatolia was an island continent or a series of islands, separate from Asia and also from Western Europe. The area now comprises approximately the modern Balkans and Anatolia. Fossil mammal ...

and the rest of eastern Eurasia. The Anoplotheriidae's relations with other members of the Artiodactyla are not well-resolved, with some determining it to be either a tylopod

Tylopoda (meaning "calloused foot") is a suborder of terrestrial herbivorous even-toed ungulates belonging to the order Artiodactyla. They are found in the wild in their native ranges of South America and Asia, while Australian feral camels are ...

(which includes camelid

Camelids are members of the biological family (biology), family Camelidae, the only currently living family in the suborder Tylopoda. The seven extant taxon, extant members of this group are: dromedary, dromedary camels, Bactrian camels, wild Bac ...

s and merycoidodont

Merycoidodontoidea, previously known as "oreodonts" or " ruminating hogs," are an extinct superfamily of prehistoric cud-chewing artiodactyls with short faces and fang-like canine teeth. As their name implies, some of the better known forms wer ...

s of the Palaeogene) or a close relative to the infraorder and some others believing that it may have been closer to the Ruminantia (which includes tragulid

Chevrotains, or mouse-deer, are small, even-toed ungulates that make up the family Tragulidae, and are the only living members of the infraorder Tragulina. The 10 extant species are placed in three genera, but several species also are kno ...

s and other close Palaeogene relatives).

The Anoplotheriidae consists of two subfamilies, the Dacrytheriinae

Anoplotheriidae is an extinct family of artiodactyl ungulates. They were endemic to Europe during the Eocene and Oligocene epochs about 44—30 million years ago. Its name is derived from the ("unarmed") and θήριον ("beast"), translating ...

and Anoplotheriinae

Anoplotheriidae is an extinct family of artiodactyl ungulates. They were endemic to Europe during the Eocene and Oligocene epochs about 44—30 million years ago. Its name is derived from the ("unarmed") and θήριον ("beast"), translating ...

, the latter of which is the younger subfamily that ''Diplobune'' belongs to. The Dacrytheriinae is the older subfamily of the two that first appeared in the middle Eocene (since the Mammal Palaeogene zones unit MP13, possibly up to MP10), although some authors consider them to be a separate family in the form of the Dacrytheriidae. Anoplotheriines made their first appearances by the late Eocene (MP15-MP16), or ~41-40 Ma, within western Europe with ''Duerotherium

''Duerotherium'' is an extinct genus of artiodactyl that lived during the Middle Eocene and is only known from the Iberian Peninsula. The genus is a member of the family Anoplotheriidae and the subfamily Anoplotheriinae, and contains one speci ...

'' and ''Robiatherium

''Robiatherium'' is an extinct genus of Palaeogene artiodactyls containing one species ''R. cournovense''. The genus name derives from the locality of Robiac in France, where some of its fossils were described, plus the Greek /, meaning "beast" ...

''. By MP17a-MP17b, however, there is a notable gap in the fossil record of anoplotheriines overall as the former two genera seemingly made their last appearances by the previous MP level MP16.

By MP18, ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' made their first appearances in western Europe, but their exact origins are unknown. The two genera were widespread throughout western Europe based on abundant fossil evidence spanning from Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom, France, Germany, and Switzerland for much of pre-Grande Coupure Europe (prior to MP21), meaning that they were typical elements of the late Eocene up until the earliest Oligocene. The earlier anoplotheriines are considered to be smaller species whereas the later anoplotheriines were larger. Not all species of ''Diplobune'' were medium to large-sized however, as at least ''D. minor'' is known for having small weight estimates. ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' are considered the most derived (or evolutionarily recent) anoplotheriids based on dental morphology and achieved gigantism amongst non- whippomorph artiodactyls, making them some of the largest non-whippomorph artiodactyls of the Palaeogene as well as amongst the largest mammals to roam western Europe at the time (all species of ''Anoplotherium'' were large to very large whereas not all species of ''Diplobune'' were large).

Conducting studies focused on the phylogenetic relations within the Anoplotheriidae has proven difficult due to the general scarcity of fossil specimens of most genera. The phylogenetic relations of the Anoplotheriidae as well as the Xiphodontidae

Xiphodontidae is an extinct family (biology), family of herbivorous even-toed ungulates (order (biology), order Artiodactyla), endemic to Europe during the Eocene 40.4—33.9 million years ago, existing for about 7.5 million years. ''P ...

, Mixtotheriidae, and Cainotheriidae

Cainotheriidae is an extinct family of artiodactyls known from the Late Eocene to Middle Miocene of Europe. They are mostly found preserved in karstic deposits.

These animals were small in size, and generally did not exceed in height at the s ...

have also been elusive due to the selenodont

Selenodont teeth are the type of molars and premolars commonly found in ruminant herbivores. They are characterized by low crowns, and crescent-shaped cusps when viewed from above (crown view).

The term comes from the Ancient Greek roots (, ' ...

morphologies (or having crescent-shaped ridges) of the molars, which were convergent with tylopod

Tylopoda (meaning "calloused foot") is a suborder of terrestrial herbivorous even-toed ungulates belonging to the order Artiodactyla. They are found in the wild in their native ranges of South America and Asia, while Australian feral camels are ...

s or ruminant

Ruminants are herbivorous grazing or browsing artiodactyls belonging to the suborder Ruminantia that are able to acquire nutrients from plant-based food by fermenting it in a specialized stomach prior to digestion, principally through microb ...

s. Some researchers considered the selenodont families Anoplotheriidae (represented below by ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Dacrytherium''), Xiphodontidae, and Cainotheriidae to be within Tylopoda due to postcranial features that were similar to the tylopods from North America in the Palaeogene. Other researchers tie them as being more closely related to ruminants than tylopods based on dental morphology. Different phylogenetic analyses have produced different results for the "derived" selenodont Eocene European artiodactyl families, making it uncertain whether they were closer to the Tylopoda or Ruminantia.

In an article published in 2019, Romain Weppe et al. conducted a phylogenetic analysis on the Cainotherioidea within the Artiodactyla based on mandibular and dental characteristics, specifically in terms of relationships with artiodactyls of the Palaeogene. The results retrieved that the superfamily was closely related to the Mixtotheriidae and Anoplotheriidae. They determined that the Cainotheriidae, Robiacinidae, Anoplotheriidae, and Mixtotheriidae formed a clade that was the sister group to the Ruminantia while Tylopoda, along with the Amphimerycidae and Xiphodontidae split earlier in the tree. The phylogenetic tree published in the article and another work about the cainotherioids is outlined below:

In 2020, Vincent Luccisano et al. created a phylogenetic tree of the basal artiodactyls, a majority endemic to western Europe, from the Palaeogene. In one clade, the "bunoselenodont endemic European" Mixtotheriidae, Anoplotheriidae, Xiphodontidae, Amphimerycidae, Cainotheriidae, and Robiacinidae are grouped together with the Ruminantia. The phylogenetic tree as produced by the authors is shown below:

In 2022, Weppe created a phylogenetic analysis in his academic thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

regarding Palaeogene artiodactyl lineages, focusing most specifically on the endemic European families. The phylogenetic tree, according to Weppe, is the first to conduct phylogenetic affinities of all anoplotheriid genera, although not all individual species were included. He found that the Anoplotheriidae, Mixtotheriidae, and Cainotherioidea form a clade based on synapomorphic

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to hav ...

dental traits (traits thought to have originated from their most recent common ancestor). The result, Weppe mentioned, matches up with previous phylogenetic analyses on the Cainotherioidea with other endemic European Palaeogene artiodactyls that support the families as a clade. As a result, he argued that the proposed superfamily Anoplotherioidea, composing of the Anoplotheriidae and Xiphodontidae as proposed by Alan W. Gentry and Hooker in 1988, is invalid due to the polyphyly

A polyphyletic group is an assemblage that includes organisms with mixed evolutionary origin but does not include their most recent common ancestor. The term is often applied to groups that share similar features known as homoplasies, which ar ...

of the lineages in the phylogenetic analysis. However, the Xiphodontidae was still found to compose part of a wider clade with the three other groups. ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune'' compose a clade of the Anoplotheriidae because of their derived dental traits, supported by them being the latest-appearing anoplotheriids.

Description

Skull

Quercy

Quercy (; , locally ) is a former province of France located in the country's southwest, bounded on the north by Limousin, on the west by Périgord and Agenais, on the south by Gascony and Languedoc, and on the east by Rouergue and Auverg ...

locality of Itardies and one of ''D. secundaria'' that was uncovered in Saint-Capraise-d'Eymet (France) in 2000. ''Diplobune'' differs from other anoplotheriids by the mandible increasing in height on the back side, its high articulation (or connection) with the cranium, its transverse elongation without any obliqueness, and its coronoid process (projection) being wide to moderately wide plus curved backwards. Many cranial traits observed in ''Anoplotherium'' are also found in its close relative ''Diplobune'', such as the glenoid (or hollow) surface being high in relation to the base of skull

The base of skull, also known as the cranial base or the cranial floor, is the most Anatomical terms of location#Superior and inferior, inferior area of the human skull, skull. It is composed of the endocranium and the lower parts of the Calvaria ...

unlike ''Dacrytherium'', a narrow occiput

The occipital bone () is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone lies over the occipital lobes of the ...

(back of the skull) that is enhanced just above the occipital condyles

The occipital condyles are undersurface protuberances of the occipital bone in vertebrates, which function in articulation with the superior facets of the Atlas (anatomy), atlas vertebra.

The condyles are oval or reniform (kidney-shaped) in shape ...

, and two small occipital bun

An occipital bun, also called an occipital spur, occipital knob, chignon hook or inion hook, is a prominent bulge or projection of the occipital bone at the back of the human skull, skull. It is important in scientific descriptions of classic Neand ...

s for muscle attachment. The upper skull of ''Diplobune'' is almost flat as a line from the parietal bones

The parietal bones ( ) are two bones in the skull which, when joined at a fibrous joint known as a cranial suture, form the sides and roof of the neurocranium. In humans, each bone is roughly quadrilateral in form, and has two surfaces, four bord ...

of the skull's back to the front area of the nasals, and the orbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit (also known as orbital revolution) is the curved trajectory of an physical body, object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an satellite, artificia ...

(eye sockets) are above M2 in position, similar to ''Anoplotherium''.

In 1927, Helga Sharpe Pearson reviewed cranial features of ''Diplobune'' based on a ''D. bavarica'' skull from the Phosphorites of Escamps, France and a ''D.'' sp. skull from Ulm

Ulm () is the sixth-largest city of the southwestern German state of Baden-Württemberg, and with around 129,000 inhabitants, it is Germany's 60th-largest city.

Ulm is located on the eastern edges of the Swabian Jura mountain range, on the up ...

, Germany (the latter skull is larger). The hind area of the basilar part of occipital bone

The basilar part of the occipital bone (also basioccipital) extends forward and upward from the foramen magnum, and presents in front an area more or less quadrilateral in outline.

In the young skull, this area is rough and uneven, and is joined ...

(basioccipital area) is convex. The position of the condylar canal

The condylar canal (or condyloid canal) is a canal in the condyloid fossa of the lateral parts of occipital bone behind the occipital condyle. Resection of the rectus capitis posterior major and minor muscles reveals the bony recess leading to th ...

and muscle arrangements of the basioccipital area of ''Diplobune'' are different from ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Dacrytherium''. The postglenoid process is bulky and projects down compared to the two anoplotheriid genera. The two skulls are similar to those of ''Anoplotherium'' by the thickened neck of the eardrum

In the anatomy of humans and various other tetrapods, the eardrum, also called the tympanic membrane or myringa, is a thin, cone-shaped membrane that separates the external ear from the middle ear. Its function is to transmit changes in pres ...

that projects vertically downwards below the opening area of the ear canal

The ear canal (external acoustic meatus, external auditory meatus, EAM) is a pathway running from the outer ear to the middle ear. The adult human ear canal extends from the auricle to the eardrum and is about in length and in diameter.

S ...

. The stylomastoid foramen

The stylomastoid foramen is a foramen between the styloid and mastoid processes of the temporal bone of the skull. It is the termination of the facial canal, and transmits the facial nerve, and stylomastoid artery. Facial nerve inflammation in th ...

is small while the hyaloid fossa

The hyaloid fossa is a depression on the anterior surface of the vitreous body

The vitreous body (''vitreous'' meaning "glass-like"; , ) is the clear gel that fills the space between the Lens (vision), lens and the retina of the eye, eyeball (t ...

is large.

''D. minor'' is known from multiple skull material such as a crushed one from Calaf

Calaf () is the main town in the northern portion of the Comarques of Catalonia, ''comarca'' of the Anoia in

Catalonia, Spain, situated on the Calaf Plain. The town holds an important weekly livestock market.

It is served by the main N-II road ...

, Spain with associated skeletal remains. The skull from Itardies measures about long and features traits typical of anoplotheriines, such as an elongated snout, backwards-extending premaxilla

The premaxilla (or praemaxilla) is one of a pair of small cranial bones at the very tip of the upper jaw of many animals, usually, but not always, bearing teeth. In humans, they are fused with the maxilla. The "premaxilla" of therian mammals h ...

, low orbits, strong post-orbital constriction

In physical anthropology, post-orbital constriction is the narrowing of the cranium (skull) just behind the eye sockets (the orbits, hence the name) found in most non-human primates and early hominins. This constriction is very noticeable in non-hu ...

, the infraorbital foramen

In human anatomy, the infraorbital foramen is one of two small holes in the skull's upper jawbone ( maxillary bone), located below the eye socket and to the left and right of the nose. Both holes are used for blood vessels and nerves. In anatomic ...

being above the P4, low zygomatic arch

In anatomy, the zygomatic arch (colloquially known as the cheek bone), is a part of the skull formed by the zygomatic process of temporal bone, zygomatic process of the temporal bone (a bone extending forward from the side of the skull, over the ...

es that take curve upward at the flat glenoid surface, and strong nuchal crests. The retroarticular process of the temporal bone

The temporal bone is a paired bone situated at the sides and base of the skull, lateral to the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex.

The temporal bones are overlaid by the sides of the head known as the temples where four of the cranial bone ...

, however, is less developed compared to that of the skull of ''D. bavarica'' that was described by Pearson in 1927. In ''D. minor'', the post-tympanic process, which limits the hind area of the ear canal, is more elongated compared to the other preceding species of ''Diplobune'' or any anoplotheriine. The occipital condyles are prominent and elongated but are less developed compared to ''A. commune''.

One well-preserved adult skull of ''D. secundaria'' from Saint-Capraise-d'Eymet measures in length, in maximum width, and in maximum height. The skull itself is large, elongated, and contains a highly developed sagittal crest

A sagittal crest is a ridge of bone running lengthwise along the midline of the top of the skull (at the sagittal suture) of many mammalian and reptilian skulls, among others. The presence of this ridge of bone indicates that there are excepti ...

, circular orbits, the frontal bone

In the human skull, the frontal bone or sincipital bone is an unpaired bone which consists of two portions.'' Gray's Anatomy'' (1918) These are the vertically oriented squamous part, and the horizontally oriented orbital part, making up the bo ...

and occipital bone which are both elongated towards the back of the skull, a thin and straight zygomatic arch, and small plus stocky temporal bones. Both the nasal bones and the maxilla

In vertebrates, the maxilla (: maxillae ) is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The two maxil ...

are elongated, the tip of the latter being rounded. The nasal bones are welded to each other and the maxilla. These traits support the presence of tapered tongues in ''Diplobune''. The sphenopalatine foramen

The sphenopalatine foramen is a foramen of the skull that connects the nasal cavity and the pterygopalatine fossa. It gives passage to the sphenopalatine artery, nasopalatine nerve, and the superior nasal nerve (all passing from the pterygopala ...

is generally oval and elongated in shape, the pterygoid bone

The pterygoid is a paired bone forming part of the palate of many vertebrates, behind the palatine bone

In anatomy, the palatine bones (; derived from the Latin ''palatum'') are two irregular bones of the facial skeleton in many animal specie ...

s are wavy and in thin striplike shapes, and the basisphenoid bone is triangular and stretched.

The mandibles of ''Diplobune'' reveal that its body's height increases towards the rear area, and the angle of the mandible

__NOTOC__

The angle of the mandible (a.k.a. gonial angle, Masseteric Tuberosity, and Masseteric Insertion) is located at the posterior border at the junction of the lower border of the ramus of the mandible.

The angle of the mandible, which may ...

is prominent. The mandibular condyle

The condyloid process or condylar process is the process on the human and other mammalian species' mandibles that ends in a condyle, the mandibular condyle. It is thicker than the coronoid process of the mandible and consists of two portions: the ...

, at the back of the mandible, has a high position while the mandible's coronoid process has a low position. These traits are more pronounced compared to most other Palaeogene ungulates, although they are not as clearly pronounced in ''D. minor''.

Endocast anatomy

Ear morphology

The endocasts of thepetrous part of the temporal bone

The petrous part of the temporal bone is pyramid-shaped and is wedged in at the base of the skull between the sphenoid and occipital bones. Directed medially, forward, and a little upward, it presents a base, an apex, three surfaces, and three ...

(or petrosals) of ''Diplobune'' differ from those of ''Anoplotherium'' in several ways. For one, a cavity of the ear in the upper edge of it is rectangular in shape in ''Diplobune'' and convex in shape in ''Anoplotherium''. The prominent part of the petrosal of ''Diplobune'' shows complicated positions and barely overlap with the skull's underside whereas that of ''Anoplotherium'' protrudes strongly around the internal auditory meatus

The internal auditory meatus (also meatus acusticus internus, internal acoustic meatus, internal auditory canal, or internal acoustic canal) is a canal within the petrous part of the temporal bone of the skull between the posterior cranial fossa ...

and straightens towards the back area. The portion of the petrosal crest located between the subarcuate fossa and the internal auditory meatus is closer to the upper edge of the periotic bone

The periotic bone is the single bone that surrounds the inner ear of birds and mammals. It is formed from the fusion of the prootic, epiotic, and opisthotic bones, and in Cetacea forms a complex with the tympanic bone

The tympanic part of the ...

in ''Diplobune'' but closer to the lower edge in ''Anoplotherium''. The subarcuate fossa is closer to the superior petrosal sinus

The superior petrosal sinus is one of the dural venous sinuses located beneath the brain. It receives blood from the cavernous sinus and passes backward and laterally to drain into the transverse sinus. The sinus receives superior petrosal veins, ...

of the brain in ''Diplobune'' than in ''Anoplotherium''.

The petrosal of ''D. minor'' contains a large, blunt, and flat mastoid region with a large mastoid process, the former of which is inconsistent with the reduced mastoid region of aquatic or semiaquatic artiodactyls. The ear morphology does not exhibit any specialty towards underwater hearing, therefore disproving that ''Diplobune'' was specialized for aquatic behaviour. Within the temporal bone, a groove projects outward the subarcuate fossa. The internal acoustic meatus

The internal auditory meatus (also meatus acusticus internus, internal acoustic meatus, internal auditory canal, or internal acoustic canal) is a canal within the petrous part of the temporal bone of the skull between the posterior cranial fossa ...

canal of the ear has a deep, oval shape with fixed boundaries from clear edges, containing two roughly equal in size foramina

In anatomy and osteology, a foramen (; : foramina, or foramens ; ) is an opening or enclosed gap within the dense connective tissue (bones and deep fasciae) of extant and extinct amniote animals, typically to allow passage of nerves, arter ...

. The petrosal bone in context of the front area near the internal acoustic meatus has a reduced area extension.

In terms of the bony labyrinth

The bony labyrinth (also osseous labyrinth or otic capsule) is the rigid, bony outer wall of the inner ear in the temporal bone. It consists of three parts: the vestibule, semicircular canals, and cochlea. These are cavities hollowed out of the ...

(outer wall of the bony ear), the cochlea

The cochlea is the part of the inner ear involved in hearing. It is a spiral-shaped cavity in the bony labyrinth, in humans making 2.75 turns around its axis, the modiolus (cochlea), modiolus. A core component of the cochlea is the organ of Cort ...

, a cavity involved in hearing, composes 50% of the total volume of the bony labyrinth. ''D. minor'' has a cochlea shape index (or aspect ratio) between 0.62 and 0.72, meaning that its cochlea is pointed instead of flattened in shape. The length of the cochlea of ''D. minor'' based on multiple specimens vary, measuring from to (8% variation).

The ''D. minor'' specimen UM ITD 1083 has an estimated interaural distance of , translating to a function interaural delay before arrival to the ear of 277 μs (millionths of a second). Based on the measurement in relation to hearing range

Hearing range describes the frequency range that can be heard by humans or other animals, though it can also refer to the range of levels. The human range is commonly given as 20 to 20,000 Hz, although there is considerable variation bet ...

, ''D. minor'' likely had a large high-frequency limit estimate of 44 KHz

The hertz (symbol: Hz) is the unit of frequency in the International System of Units (SI), often described as being equivalent to one event (or cycle) per second. The hertz is an SI derived unit whose formal expression in terms of SI base uni ...

. Another specimen UM ITD 1081 has an estimated high-frequency limit estimate of 32 kHz and a low-frequency limit of 0.35 kHz. The frequency limits of ''Diplobune'' suggest that it was not a specialist in low-level or high-level hearing frequency limit, since its high-level range, between 30 and 44 kHz, is similar to most extant terrestrial artiodactyls while its low-level range, between 0.11 and 0.4 kHz, is high compared to extant artiodactyls. It is not certain whether the equations used for predicting hearing frequency limits of fossil animals are accurate. Either way, ''Diplobune'' does not show cochlear morphology for underwater hearing.

Brain

In 1928, palaeoneurologist

In 1928, palaeoneurologist Tilly Edinger

Johanna Gabrielle Ottilie "Tilly" Edinger (13 November 1897 – 27 May 1967) was a German-American paleontologist and the founder of paleoneurology.

Personal life

Early life

Tilly Edinger was born to a wealthy Jewish family in 1897. Her fat ...

wrote about multiple endocasts of ''D. bavarica'' from their skulls from the collection of the State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart

The State Museum of Natural History Stuttgart (), abbreviated SMNS, is one of the two state of Baden-Württemberg's natural history museums. Together with the State Museum of Natural History Karlsruhe (Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Karls ...

, one complete but most others partial. The mostly complete brain cast measures long. Its olfactory bulb

The olfactory bulb (Latin: ''bulbus olfactorius'') is a neural structure of the vertebrate forebrain involved in olfaction, the sense of smell. It sends olfactory information to be further processed in the amygdala, the orbitofrontal cortex (OF ...

s measure , although they may have been incompletely preserved. The bulbs are extensive and fused into one mass. In ''Diplobune'', the cerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

has a comparable large height to the cerebrum

The cerebrum (: cerebra), telencephalon or endbrain is the largest part of the brain, containing the cerebral cortex (of the two cerebral hemispheres) as well as several subcortical structures, including the hippocampus, basal ganglia, and olfac ...

, and neither touch each other. Anoplotheriids were characterized by elongated brains with large olfactory bulbs and a simple, straight, and furrowed cerebrum that did not overlap with the equally wide cerebellum.

In 1969, Colette Dechaseaux conducted an extensive study on known Palaeogene artiodactyls with known endocasts, including on anoplotheriids ''Anoplotherium'' and ''Diplobune''. She pointed out that in both, a narrow and deep furrow separates the cerebellum from the cerebrum. The cerebellar vermis

The cerebellar vermis (from Latin ''vermis,'' "worm") is located in the medial, cortico-nuclear zone of the cerebellum, which is in the posterior cranial fossa, posterior fossa of the cranium. The primary fissure in the vermis curves ventrolatera ...

is wide and protruding that it is more prominent than the other cerebellar hemispheres. The prominence is not made immediately obvious, however, because of the enlargement of the cerebellar hemispheres due to connection in the outer face with strong petrosal sinuses. The upper view of the cerebral hemisphere reveals its convex shape with a lower area in the front compared to the back. The rhinal area (or nasal area) is close to the upper edge of the neocortex

The neocortex, also called the neopallium, isocortex, or the six-layered cortex, is a set of layers of the mammalian cerebral cortex involved in higher-order brain functions such as sensory perception, cognition, generation of motor commands, ...

, therefore composing a low frontal lobe

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere (in front of the parietal lobe and the temporal lobe). It is parted from the parietal lobe by a Sulcus (neur ...

compared to the temporal lobe

The temporal lobe is one of the four major lobes of the cerebral cortex in the brain of mammals. The temporal lobe is located beneath the lateral fissure on both cerebral hemispheres of the mammalian brain.

The temporal lobe is involved in pr ...

. The sagittal sinus, present on the outer face of the piriform cortex

The piriform cortex, or pyriform cortex, is a region in the brain, part of the rhinencephalon situated in the cerebrum. The function of the piriform cortex relates to the sense of smell.

Structure

The piriform cortex is part of the rhinencephal ...

, branches out well on the outer area, especially in the back. ''Anoplotherium'' and large species of ''Diplobune'' are similar also in the appearance of the back rhinal area.

Despite the major similarities, the brains of anoplotheriid species have several differences. For instance, the exact location of the primary fissure of the cerebellum (or fissura prima) of ''Anoplotherium'' is difficult to locate because the cerebellar vermis's front area is hidden by a transverse sinus covering space between the cerebral hemispheres and the cerebellum. In comparison, ''Diplobune'' has a transverse sinus attached to the base of the cerebral hemisphere that displays the vermis. In large-sized species of ''Diplobune'', the paleocerebellum

The cerebellum (: cerebella or cerebellums; Latin for 'little brain') is a major feature of the hindbrain of all vertebrates. Although usually smaller than the cerebrum, in some animals such as the mormyrid fishes it may be as large as it or eve ...

is swollen, voluminous, and more spread out in its width compared to the neocerebellum

The posterior lobe of cerebellum or neocerebellum is one of the lobes of the cerebellum, below the primary fissure. The posterior lobe is much larger than anterior lobe. The anterior lobe is separated from the posterior lobe by the primary fissu ...

. In small-sized species, two furrows of the vermis are present, one being near the front edge (possibly the fissura prima) and the other being only slightly over half the length of the other. Therefore, the paleocerebella of small species were smaller than the neocerebella.

The widths of the cerebral hemispheres of ''Diplobune'' are further back compared to ''Anoplotherium''. The upper surface of the cerebral hemispheres of ''Diplobune'' is flatter, and the neocortex lowering forward from the approximate back third of its length so that the latter can connect with the base of the olfactory peduncle

The olfactory tract (olfactory peduncle or olfactory stalk) is a bilateral bundle of afferent nerve fibers from the mitral and tufted cells of the olfactory bulb that connects to several target regions in the brain, including the piriform cor ...

. In comparison, the same cerebral hemispheres surface of ''Anoplotherium'' is convex, and the neocortex to some extent maintains thickness. The back rhinal area of the brain of ''Diplobune'' is rectilinear except for the back end where the area ascends.

Dentition

Thedental formula

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiology ...

of ''Diplobune'' and other anoplotheriids is for a total of 44 teeth, consistent with the primitive dental formula for early-middle Palaeogene placental

Placental mammals (infraclass Placentalia ) are one of the three extant subdivisions of the class Mammalia, the other two being Monotremata and Marsupialia. Placentalia contains the vast majority of extant mammals, which are partly distinguished ...

mammals. Anoplotheriids have selenodont (crescent-shaped ridge form) or bunoselenodont (bunodont and selenodont) premolar

The premolars, also called premolar Tooth (human), teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the Canine tooth, canine and Molar (tooth), molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per dental terminology#Quadrant, quadrant in ...

s (P/p) and molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat tooth, teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammal, mammals. They are used primarily to comminution, grind food during mastication, chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, '' ...

(M/m) made for leaf-browsing diets. The canines (C/c) of the Anoplotheriidae are overall undifferentiated from the incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, wher ...

s (I/i). The lower premolars of the family are piercing and elongated. The upper molars are bunoselenodont in form while the lower molars have selenodont labial cuspids and bunodont (or rounded) lingual cuspids. The subfamily Anoplotheriinae differs from the Dacrytheriinae by the molariform premolars with crescent-shaped paraconules and the lower molars that lack a third cusp between the metaconid and entoconid.

''Diplobune'' is very similar in dentition to the similarly derived ''Anoplotherium'' but differs primarily by the generally smaller sizes and its two front tubercles ( crowns) of its lower molars being welded together in a "bicuspid" (or two-pointed) pillarlike shape. ''Diplobune'' is also specifically diagnosed by many specific dental traits, making its diagnoses more focused on dental traits compared to ''Anoplotherium''. Its upper incisors are separated by short diastema

A diastema (: diastemata, from Greek , 'space') is a space or gap between two teeth. Many species of mammals have diastemata as a normal feature, most commonly between the incisors and molars. More colloquially, the condition may be referred to ...

ta. Its I1 is large, procumbent

This glossary of botanical terms is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to botany and plants in general. Terms of plant morphology are included here as well as at the more specific Glossary of plant morphology and Glossary ...

, and curved while the I2 and I3 are smaller and vertically within the premaxilla. In terms of lower incisors, the I1 and I2 are round in shape and procumbent while the I3 has a somewhat triangular shape, all of which are vertically within the maxilla. The canine (C) is undifferentiated from the incisors, typical of the Anoplotheriinae, and it is compressed and linear (or ridged). The P1 is canine-like while the P2 and P3 are relatively elongated and each have a posterolingual heel. The P4 is somewhat triangular in shape with a labially prominent parastyle cusp. The P4 is small in size. The upper molars are bunoselenodont, have five cusps (meaning that the molar is "pentacuspidate") and have prominent cusp arrangements, consistent with the Anoplotheriidae. The lower molars contain a fusion of the paraconid cusp with the metaconid cusp, giving rise to a mesiodistal cusp that is divided in two.

Vertebrae

Unlike ''Anoplotherium'', ''Diplobune'' is not as well known in remains of vertebrae or ribs. Fraas in 1870 referenced 1dorsal vertebra

In vertebrates, thoracic vertebrae compose the middle segment of the vertebral column, between the cervical vertebrae and the lumbar vertebrae. In humans, there are twelve thoracic vertebrae of intermediate size between the cervical and lumbar ve ...

, 1 lumbar vertebra

The lumbar vertebrae are located between the thoracic vertebrae and pelvis. They form the lower part of the back in humans, and the tail end of the back in quadrupeds. In humans, there are five lumbar vertebrae. The term is used to describe the ...

, and 6 caudal vertebrae

Caudal vertebrae are the vertebrae of the tail in many vertebrates. In birds, the last few caudal vertebrae fuse into the pygostyle, and in apes, including humans, the caudal vertebrae are fused into the coccyx.

In many reptiles, some of the caud ...

(tail vertebrae) from a museum in Berlin

Berlin ( ; ) is the Capital of Germany, capital and largest city of Germany, by both area and List of cities in Germany by population, population. With 3.7 million inhabitants, it has the List of cities in the European Union by population withi ...

that he thought belonged to ''Diplobune'', the number of tail vertebrae being similar to that of ''Anoplotherium''. The vertebrae were neither illustrated in his source nor referenced in future literature, however, making their statuses unknown. Sudre in 1982 also did not indicate vertebrae specimens but hypothesized that unlike ''Anoplotherium'', the tail of ''D. minor'' was not elongated based on apparently known vertebrae.

Limbs

Unlike typical "even-toed" artiodactyls and ''Anoplotherium'' where one species (''A. commune'') is didactyl (two-toed) as opposed to all other species which are tridactyl (three-toed), all species of ''Diplobune'' are tridactyl. Multiple limb fossils are known from ''D. secundaria'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minor''. ''Diplobune'' is thought to be semi-

Unlike typical "even-toed" artiodactyls and ''Anoplotherium'' where one species (''A. commune'') is didactyl (two-toed) as opposed to all other species which are tridactyl (three-toed), all species of ''Diplobune'' are tridactyl. Multiple limb fossils are known from ''D. secundaria'', ''D. quercyi'', and ''D. minor''. ''Diplobune'' is thought to be semi-digitigrade

In terrestrial vertebrates, digitigrade ( ) locomotion is walking or running on the toes (from the Latin ''digitus'', 'finger', and ''gradior'', 'walk'). A digitigrade animal is one that stands or walks with its toes (phalanges) on the ground, and ...

or fully digitigrade based on its limb morphology, with a common proposed adaptation being proposed for multiple species as a result. The two right-side fingers (fingers III and IV) are similar in terms of long sizes although finger IV is slightly longer while the left finger (finger II) is short and relatively spaced out from the two other fingers. Each finger has three phalange

The phalanges (: phalanx ) are digital bones in the hands and feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are classed as long bones.

Structure ...

s, the second phalanx being half as long as the first. The articular surface of the third phalanx for the hoof rises on the dorsal side, indicating mobility of the hoof. The hooves of fingers III and IV are asymmetric, similar to both extant terrestrial artiodactyls and ''Anoplotherium''.

Front limbs

Thescapula

The scapula (: scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on either side ...

(or shoulder blade) is triangular, asymmetrical, and wide, its low scapular index value of 118 potentially implying both a broad thorax