The Carboniferous ( ) is a

geologic period

The geologic time scale or geological time scale (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochronolo ...

and

system

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its open system (systems theory), environment, is described by its boundaries, str ...

of the

Paleozoic

The Paleozoic ( , , ; or Palaeozoic) Era is the first of three Era (geology), geological eras of the Phanerozoic Eon. Beginning 538.8 million years ago (Ma), it succeeds the Neoproterozoic (the last era of the Proterozoic Eon) and ends 251.9 Ma a ...

era

An era is a span of time.

Era or ERA may also refer to:

* Era (geology), a subdivision of geologic time

* Calendar era

Education

* Academy of European Law (German: '), an international law school

* ERA School, in Melbourne, Australia

* E ...

that spans 60 million years, from the end of the

Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

Period Ma (million years ago) to the beginning of the

Permian

The Permian ( ) is a geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system which spans 47 million years, from the end of the Carboniferous Period million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Triassic Period 251.902 Mya. It is the s ...

Period, Ma. It is the fifth and penultimate period of the Paleozoic era and the fifth period of the

Phanerozoic

The Phanerozoic is the current and the latest of the four eon (geology), geologic eons in the Earth's geologic time scale, covering the time period from 538.8 million years ago to the present. It is the eon during which abundant animal and ...

eon

Eon, EON or Eons may refer to: Time

* Aeon, an indefinite long period of time

* Eon (geology), a division of the geologic time scale

Arts and entertainment

Fictional characters

* Eon, in the 2007 film '' Ben 10: Race Against Time''

* Eon, i ...

. In

North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere, Northern and Western Hemisphere, Western hemispheres. North America is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South Ameri ...

, the Carboniferous is often treated as two separate geological periods, the earlier

Mississippian

Mississippian may refer to:

* Mississippian (geology), a subperiod of the Carboniferous period in the geologic timescale, roughly 360 to 325 million years ago

* Mississippian cultures, a network of precontact cultures across the midwest and Easte ...

and the later

Pennsylvanian Pennsylvanian may refer to:

* A person or thing from Pennsylvania

* Pennsylvanian (geology)

The Pennsylvanian ( , also known as Upper Carboniferous or Late Carboniferous) is, on the International Commission on Stratigraphy, ICS geologic timesc ...

.

The name ''Carboniferous'' means "

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

-bearing", from the

Latin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

("

coal

Coal is a combustible black or brownish-black sedimentary rock, formed as rock strata called coal seams. Coal is mostly carbon with variable amounts of other Chemical element, elements, chiefly hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, and nitrogen.

Coal i ...

") and ("bear, carry"), and refers to the many coal beds formed globally during that time. The first of the modern "system" names, it was coined by geologists

William Conybeare and

William Phillips in 1822, based on a study of the British rock succession.

Carboniferous is the period during which both

terrestrial animal

Terrestrial animals are animals that live predominantly or entirely on land (e.g. cats, chickens, ants, most spiders), as compared with aquatic animals, which live predominantly or entirely in the water (e.g. fish, lobsters, octopuses), ...

and

land plant

The embryophytes () are a clade of plants, also known as Embryophyta (Plantae ''sensu strictissimo'') () or land plants. They are the most familiar group of photoautotrophs that make up the vegetation on Earth's dry lands and wetlands. Embryophyt ...

life was well established.

Stegocephalia

Stegocephali (often spelled Stegocephalia, from Greek , lit. "roofed head") is a clade of vertebrate animals containing all fully limbed tetrapodomorphs. It is equivalent to a broad definition of the superclass Tetrapoda: under this broad ...

(four-limbed

vertebrate

Vertebrates () are animals with a vertebral column (backbone or spine), and a cranium, or skull. The vertebral column surrounds and protects the spinal cord, while the cranium protects the brain.

The vertebrates make up the subphylum Vertebra ...

s including true

tetrapod

A tetrapod (; from Ancient Greek :wiktionary:τετρα-#Ancient Greek, τετρα- ''(tetra-)'' 'four' and :wiktionary:πούς#Ancient Greek, πούς ''(poús)'' 'foot') is any four-Limb (anatomy), limbed vertebrate animal of the clade Tetr ...

s), whose forerunners (

tetrapodomorph

Tetrapodomorpha (also known as Choanata) is a clade of vertebrates consisting of tetrapods (four-limbed vertebrates) and their closest sarcopterygian relatives that are more closely related to living tetrapods than to living lungfish. Advanced for ...

s) had evolved from

lobe-finned fish

Sarcopterygii (; )—sometimes considered synonymous with Crossopterygii ()—is a clade (traditionally a class or subclass) of vertebrate animals which includes a group of bony fish commonly referred to as lobe-finned fish. These vertebrates ar ...

during the preceding Devonian period, became

pentadactylous during the Carboniferous. The period is sometimes called the Age of Amphibians because of the

diversification of early

amphibian

Amphibians are ectothermic, anamniote, anamniotic, tetrapod, four-limbed vertebrate animals that constitute the class (biology), class Amphibia. In its broadest sense, it is a paraphyletic group encompassing all Tetrapod, tetrapods, but excl ...

s such as the

temnospondyl

Temnospondyli (from Greek language, Greek τέμνειν, ''temnein'' 'to cut' and σπόνδυλος, ''spondylos'' 'vertebra') or temnospondyls is a diverse ancient order (biology), order of small to giant tetrapods—often considered Labyrinth ...

s, which became dominant land vertebrates, as well as the first appearance of

amniote

Amniotes are tetrapod vertebrate animals belonging to the clade Amniota, a large group that comprises the vast majority of living terrestrial animal, terrestrial and semiaquatic vertebrates. Amniotes evolution, evolved from amphibious Stem tet ...

s including

synapsid

Synapsida is a diverse group of tetrapod vertebrates that includes all mammals and their extinct relatives. It is one of the two major clades of the group Amniota, the other being the more diverse group Sauropsida (which includes all extant rept ...

s (the

clade

In biology, a clade (), also known as a Monophyly, monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that is composed of a common ancestor and all of its descendants. Clades are the fundamental unit of cladistics, a modern approach t ...

to which modern

mammal

A mammal () is a vertebrate animal of the Class (biology), class Mammalia (). Mammals are characterised by the presence of milk-producing mammary glands for feeding their young, a broad neocortex region of the brain, fur or hair, and three ...

s belong) and

sauropsid

Sauropsida ( Greek for "lizard faces") is a clade of amniotes, broadly equivalent to the class Reptilia, though typically used in a broader sense to also include extinct stem-group relatives of modern reptiles and birds (which, as theropod dino ...

s (which include modern reptiles and birds) during the late Carboniferous. Land

arthropod

Arthropods ( ) are invertebrates in the phylum Arthropoda. They possess an arthropod exoskeleton, exoskeleton with a cuticle made of chitin, often Mineralization (biology), mineralised with calcium carbonate, a body with differentiated (Metam ...

s such as

arachnid

Arachnids are arthropods in the Class (biology), class Arachnida () of the subphylum Chelicerata. Arachnida includes, among others, spiders, scorpions, ticks, mites, pseudoscorpions, opiliones, harvestmen, Solifugae, camel spiders, Amblypygi, wh ...

s (e.g.

trigonotarbid

The Order (biology), order Trigonotarbida is a group of extinct arachnids whose fossil record extends from the late Silurian to the early Permian (Pridoli epoch, Pridoli to Sakmarian).Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2020A summary list of fos ...

s and ''

Pulmonoscorpius

''Pulmonoscorpius'' is an extinct genus of scorpion from the Mississippian (Early Carboniferous) of Scotland. It contains a single named species, ''Pulmonoscorpius kirktonensis''. It was one of the largest scorpions to have ever lived, with the ...

''),

myriapod

Myriapods () are the members of subphylum Myriapoda, containing arthropods such as millipedes and centipedes. The group contains about 13,000 species, all of them terrestrial.

Although molecular evidence and similar fossils suggests a diversifi ...

s (e.g. ''

Arthropleura

''Arthropleura'', from Ancient Greek ἄρθρον (''árthron''), meaning "joint", and πλευρά (''pleurá''), meaning "rib", is an extinct genus of massive myriapoda, myriapod that lived in what is now Europe and North America around 344 t ...

'') and especially insects (particularly

flying insects

Pterygota ( ) is a subclass of insects that includes all winged insects and groups who lost them secondarily.

Pterygota group comprises 99.9% of all insects. The orders not included are the Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and the Zygent ...

) also underwent a major

evolutionary radiation

An evolutionary radiation is an increase in taxonomic diversity that is caused by elevated rates of speciation, that may or may not be associated with an increase in morphological disparity. A significantly large and diverse radiation within ...

during the late Carboniferous.

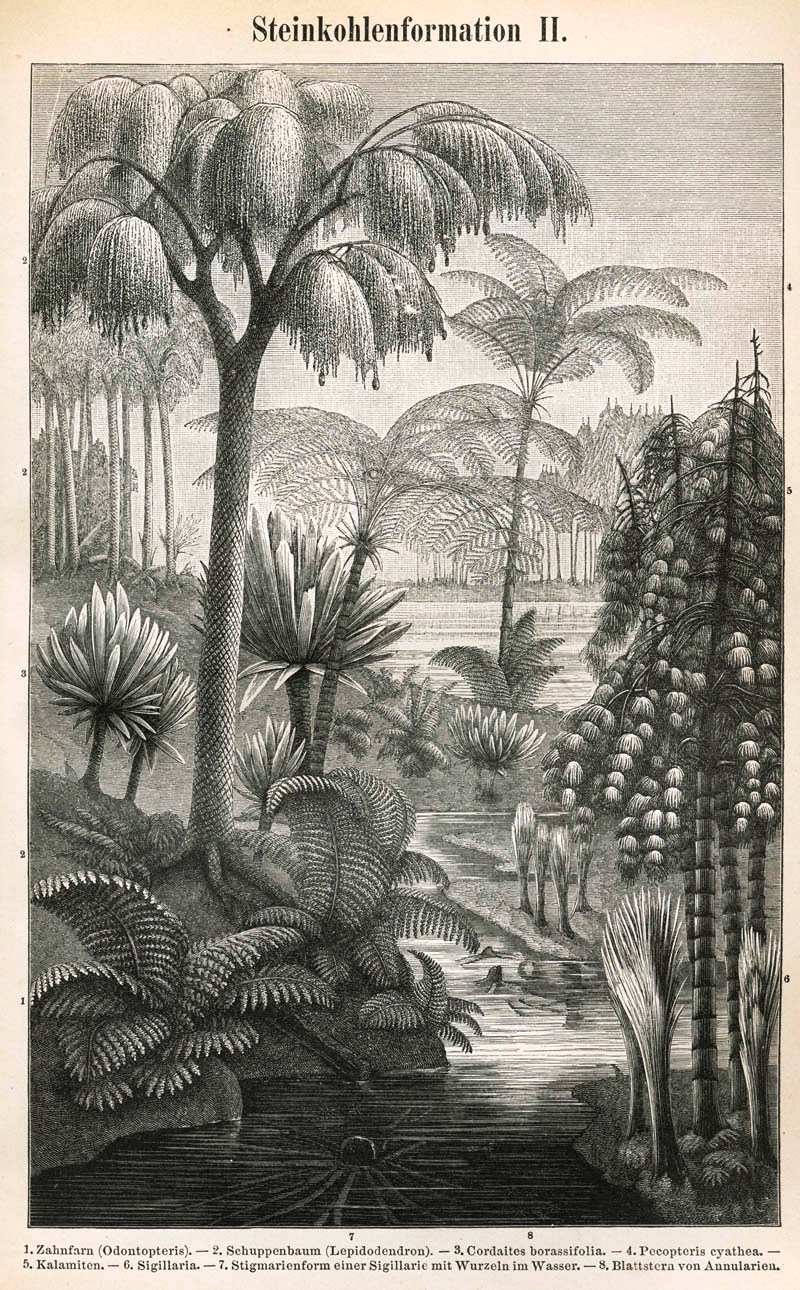

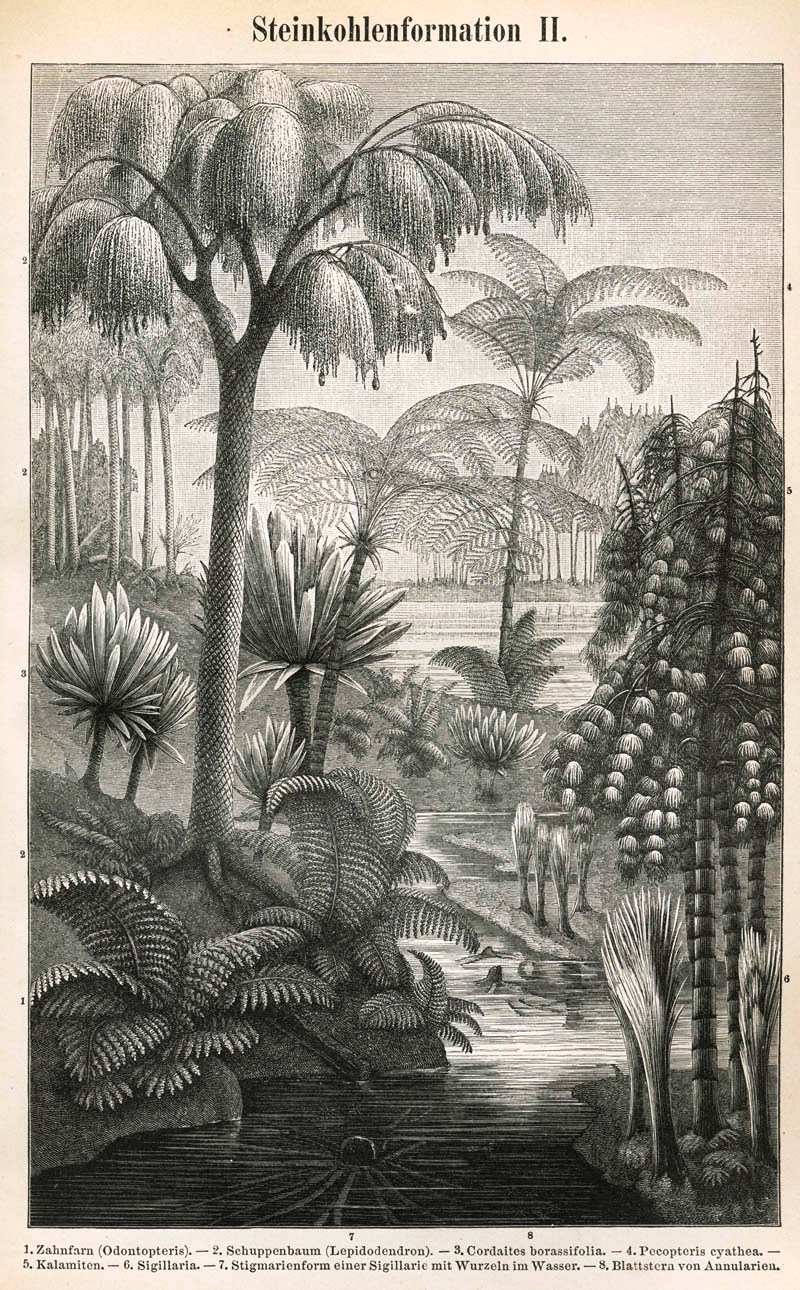

Vast swaths of forests and swamps covered the land, which eventually became the coal beds characteristic of the Carboniferous

stratigraphy

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithost ...

evident today.

The later half of the period experienced

glaciations

A glacial period (alternatively glacial or glaciation) is an interval of time (thousands of years) within an ice age that is marked by colder temperatures and glacier advances. Interglacials, on the other hand, are periods of warmer climate betw ...

, low sea level, and

mountain building

Mountain formation occurs due to a variety of geological processes associated with large-scale movements of the Earth's crust (List of tectonic plates, tectonic plates). Fold (geology), Folding, Fault (geology), faulting, Volcano, volcanic acti ...

as the continents collided to form

Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea ( ) was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous period approximately 335 mi ...

. A minor marine and terrestrial extinction event, the

Carboniferous rainforest collapse

The Carboniferous rainforest collapse (CRC) was a minor extinction event that occurred around 305 million years ago in the Carboniferous period. The event occurred at the end of the Moscovian and continued into the early Kasimovian stages of th ...

, occurred at the end of the period, caused by climate change. Atmospheric oxygen levels, originally thought to be consistently higher than today throughout the Carboniferous, have been shown to be more variable, increasing from low levels at the beginning of the Period to highs of 25–30%.

Etymology and history

The development of a Carboniferous

chronostratigraphic

Chronostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy that studies the ages of rock strata in relation to time.

The ultimate aim of chronostratigraphy is to arrange the sequence of deposition and the time of deposition of all rocks within a geological ...

timescale began in the late 18th century. The term "Carboniferous" was first used as an adjective by Irish geologist

Richard Kirwan

Richard Kirwan, LL.D, Fellow of the Royal Society, FRS, FRSE Membership of the Royal Irish Academy, MRIA (1 August 1733 – 22 June 1812) was an Irish geologist and chemist. He was one of the last supporters of the theory of Phlogiston theory, ...

in 1799 and later used in a heading entitled "Coal-measures or Carboniferous Strata" by

John Farey Sr. in 1811. Four units were originally ascribed to the Carboniferous, in ascending order, the

Old Red Sandstone

Old Red Sandstone, abbreviated ORS, is an assemblage of rocks in the North Atlantic region largely of Devonian age. It extends in the east across Great Britain, Ireland and Norway, and in the west along the eastern seaboard of North America. It ...

,

Carboniferous Limestone,

Millstone Grit

Millstone Grit is any of a number of coarse-grained sandstones of Carboniferous age which occur in the British Isles. The name derives from its use in earlier times as a source of millstones for use principally in watermills. Geologists refer to ...

and the

Coal Measures. These four units were placed into a formalised Carboniferous unit by

William Conybeare and

William Phillips in 1822 and then into the Carboniferous System by Phillips in 1835. The Old Red Sandstone was later considered

Devonian

The Devonian ( ) is a period (geology), geologic period and system (stratigraphy), system of the Paleozoic era (geology), era during the Phanerozoic eon (geology), eon, spanning 60.3 million years from the end of the preceding Silurian per ...

in age.

The similarity in successions between the British Isles and Western Europe led to the development of a common European timescale with the Carboniferous System divided into the lower

Dinantian

The Dinantian is a series or epoch from the Lower Carboniferous system in western Europe between 359.2 and 326.4 million years ago. It can stand for a series of rocks in Europe or the time span in which they were deposited.

The Dinantian is eq ...

, dominated by

carbonate

A carbonate is a salt of carbonic acid, (), characterized by the presence of the carbonate ion, a polyatomic ion with the formula . The word "carbonate" may also refer to a carbonate ester, an organic compound containing the carbonate group ...

deposition and the upper

Silesian with mainly

siliciclastic

Siliciclastic (or ''siliclastic'') rocks are clastic noncarbonate sedimentary rocks that are composed primarily of silicate minerals, such as quartz or clay minerals. Siliciclastic rock types include mudrock, sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic ...

deposition.

The Dinantian was divided into the

Tournaisian

The Tournaisian is in the ICS geologic timescale the lowest stage or oldest age of the Mississippian, the oldest subsystem of the Carboniferous. The Tournaisian age lasted from Ma to Ma. It is preceded by the Famennian (the uppermost st ...

and

Viséan

The Visean, Viséan or Visian is an age in the ICS geologic timescale or a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the second stage of the Mississippian, the lower subsystem of the Carboniferous. The Visean lasted from to Ma. It follows ...

stages. The Silesian was divided into the

Namurian

The Namurian is a stage in the regional stratigraphy of northwest Europe, with an age between roughly 331 and 319 Ma (million years ago). It is a subdivision of the Carboniferous system or period, as well as the regional Silesian series. The Na ...

,

Westphalian and

Stephanian stages. The Tournaisian is the same length as the

International Commission on Stratigraphy

The International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), sometimes unofficially referred to as the International Stratigraphic Commission, is a daughter or major subcommittee grade scientific organization that concerns itself with stratigraphy, strati ...

(ICS) stage, but the Viséan is longer, extending into the lower

Serpukhovian

The Serpukhovian is in the ICS geologic timescale the uppermost stage or youngest age of the Mississippian, the lower subsystem of the Carboniferous. The Serpukhovian age lasted from Ma to Ma. It is preceded by the Visean and is followed ...

.

North American geologists recognised a similar stratigraphy but divided it into two systems rather than one. These are the lower carbonate-rich sequence of the

Mississippian

Mississippian may refer to:

* Mississippian (geology), a subperiod of the Carboniferous period in the geologic timescale, roughly 360 to 325 million years ago

* Mississippian cultures, a network of precontact cultures across the midwest and Easte ...

System and the upper siliciclastic and coal-rich sequence of the

Pennsylvanian Pennsylvanian may refer to:

* A person or thing from Pennsylvania

* Pennsylvanian (geology)

The Pennsylvanian ( , also known as Upper Carboniferous or Late Carboniferous) is, on the International Commission on Stratigraphy, ICS geologic timesc ...

. The

United States Geological Survey

The United States Geological Survey (USGS), founded as the Geological Survey, is an agency of the U.S. Department of the Interior whose work spans the disciplines of biology, geography, geology, and hydrology. The agency was founded on Mar ...

officially recognised these two systems in 1953.

In Russia, in the 1840s British and Russian geologists divided the Carboniferous into the Lower, Middle and Upper series based on Russian sequences. In the 1890s these became the Dinantian,

Moscovian

Moscovian may refer to:

*An inhabitant of Moscow, the capital of Russia

*Something of, from, or related to Moscow

*Moscovian (Carboniferous)

The Moscovian is in the International Commission on Stratigraphy, ICS geologic timescale a stage (strat ...

and Uralian stages. The Serpukivian was proposed as part of the Lower Carboniferous, and the Upper Carboniferous was divided into the Moscovian and

Gzhelian

The Gzhelian ( ) is an age in the ICS geologic time scale or a stage in the stratigraphic column. It is the youngest stage of the Pennsylvanian, the youngest subsystem of the Carboniferous. The Gzhelian lasted from to Ma. It follows the Ka ...

. The

Bashkirian

The Bashkirian is in the International Commission on Stratigraphy geologic timescale the lowest stage (stratigraphy), stage or oldest age (geology), age of the Pennsylvanian (geology), Pennsylvanian. The Bashkirian age lasted from to Mega annu ...

was added in 1934.

In 1975, the ICS formally ratified the Carboniferous System, with the Mississippian and Pennsylvanian subsystems from the North American timescale, the Tournaisian and Visean stages from the Western European and the Serpukhovian, Bashkirian, Moscovian,

Kasimovian

The Kasimovian is a geochronologic age or chronostratigraphic stage in the ICS geologic timescale. It is the third stage in the Pennsylvanian (late Carboniferous), lasting from to Ma.; 2004: ''A Geologic Time Scale 2004'', Cambridge Unive ...

and Gzhelian from the Russian.

With the formal ratification of the Carboniferous System, the Dinantian, Silesian, Namurian, Westphalian and Stephanian became redundant terms, although the latter three are still in common use in Western Europe.

Geology

Stratigraphy

Stages can be defined globally or regionally. For global stratigraphic correlation, the ICS ratify global stages based on a

Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point

A Global Boundary Stratotype Section and Point (GSSP), sometimes referred to as a golden spike, is an internationally agreed upon reference point on a stratigraphic section which defines the lower boundary of a stage on the geologic time scale. ...

(GSSP) from a single

formation

Formation may refer to:

Linguistics

* Back-formation, the process of creating a new lexeme by removing or affixes

* Word formation, the creation of a new word by adding affixes

Mathematics and science

* Cave formation or speleothem, a secondary ...

(a

stratotype

In geology, a stratotype or type section is the physical location or outcrop of a particular reference exposure of a stratigraphic sequence or stratigraphic boundary. If the stratigraphic unit is layered, it is called a stratotype, whereas the ...

) identifying the lower boundary of the stage. Only the boundaries of the Carboniferous System and three of the stage bases are defined by global stratotype sections and points because of the complexity of the geology.

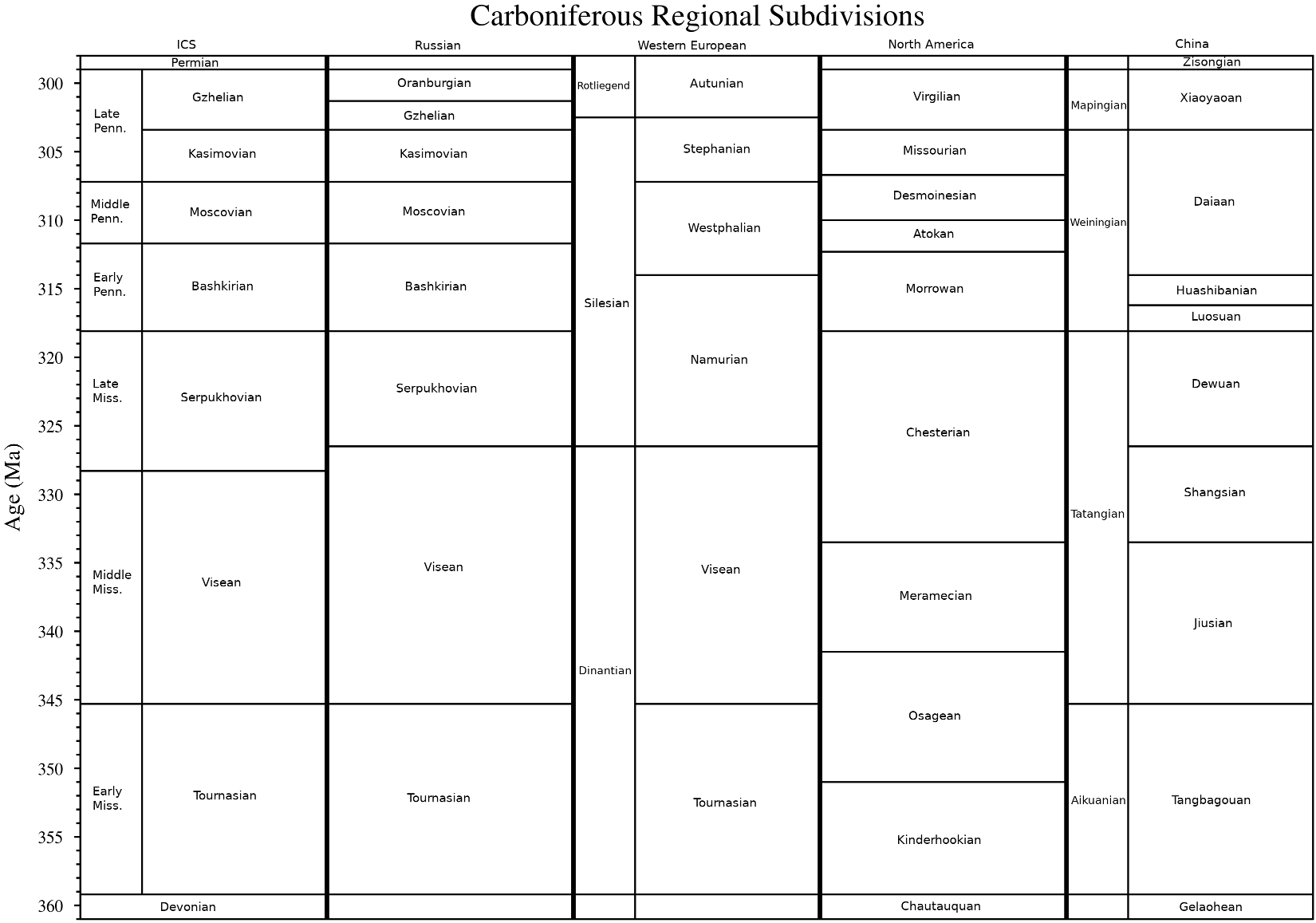

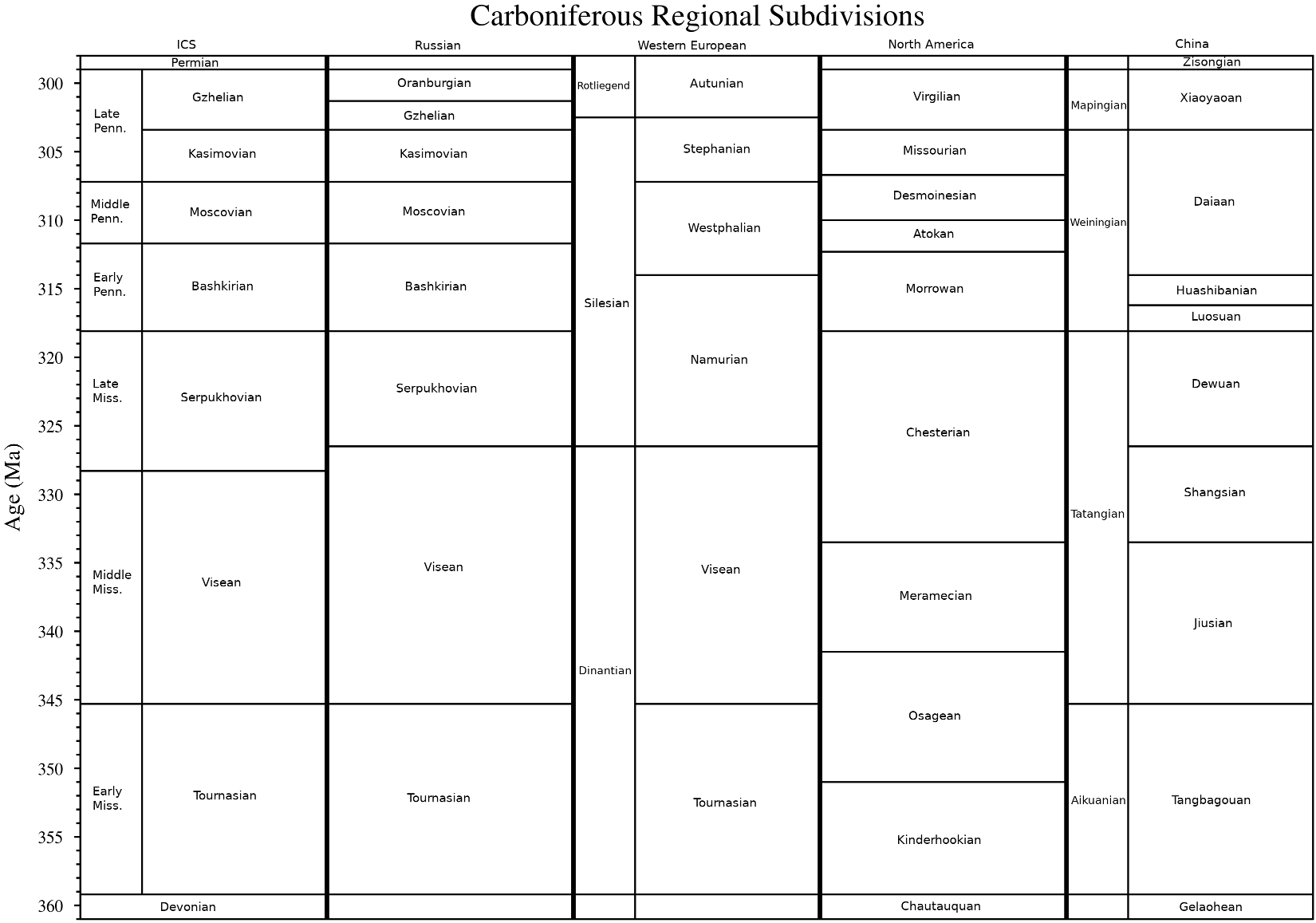

The ICS subdivisions from youngest to oldest are as follows:

[Cohen, K.M., Finney, S.C., Gibbard, P.L. & Fan, J.-X. (2013; updated]

The ICS International Chronostratigraphic Chart

Episodes 36: 199–204.

Mississippian

The Mississippian was proposed by

Alexander Winchell

Alexander Winchell (December 31, 1824, in North East, New York – February 19, 1891, in Ann Arbor, Michigan) was an American geologist who contributed to this field mainly as an educator and a popular lecturer and writer. His views on evolutio ...

in 1870 named after the extensive exposure of lower Carboniferous

limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

in the upper

Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the main stem, primary river of the largest drainage basin in the United States. It is the second-longest river in the United States, behind only the Missouri River, Missouri. From its traditional source of Lake Ita ...

valley.

During the Mississippian, there was a marine connection between the

Paleo-Tethys and

Panthalassa

Panthalassa, also known as the Panthalassic Ocean or Panthalassan Ocean (from Greek "all" and "sea"), was the vast superocean that encompassed planet Earth and surrounded the supercontinent Pangaea, the latest in a series of supercontinent ...

through the

Rheic Ocean

The Rheic Ocean (; ) was an ocean which separated two major paleocontinents, Gondwana and Laurussia ( Laurentia- Baltica- Avalonia). One of the principal oceans of the Paleozoic, its sutures today stretch from Mexico to Turkey and its closure r ...

resulting in the near worldwide distribution of marine faunas and so allowing widespread correlations using marine

biostratigraphy

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. "Biostratigraphy." ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of Biology ...

.

However, there are few Mississippian

volcanic rock

Volcanic rocks (often shortened to volcanics in scientific contexts) are rocks formed from lava erupted from a volcano. Like all rock types, the concept of volcanic rock is artificial, and in nature volcanic rocks grade into hypabyssal and me ...

s, and so obtaining

radiometric dates is difficult.

The Tournaisian Stage is named after the Belgian city of

Tournai

Tournai ( , ; ; ; , sometimes Anglicisation (linguistics), anglicised in older sources as "Tournay") is a city and Municipalities in Belgium, municipality of Wallonia located in the Hainaut Province, Province of Hainaut, Belgium. It lies by ...

. It was introduced in scientific literature by Belgian geologist

André Dumont in 1832. The GSSP for the base of the Carboniferous System, Mississippian Subsystem and Tournaisian Stage is located at the

La Serre

La Serre (; ) is a commune in the Aveyron department in southern France.

Population

The GSSP Golden Spike for the Tournaisian is in La Serre, with the first appearance of the conodont ''Siphonodella sulcata''. In 2006 it was discovered ...

section in

Montagne Noire

The Montagne Noire (; , known as the 'Black Mountain' in English) is a mountain range in central southern France. It is located at the southwestern end of the Massif Central at the juncture of the Tarn, Hérault and Aude departments. Its highe ...

, southern France. It is defined by the first appearance of the

conodont

Conodonts, are an extinct group of marine jawless vertebrates belonging to the class Conodonta (from Ancient Greek κῶνος (''kōnos''), meaning " cone", and ὀδούς (''odoús''), meaning "tooth"). They are primarily known from their hard ...

''

Siphonodella sulcata

''Siphonodella'' is an extinct genus of Conodont, conodonts.

''Siphonodella banraiensis'' is from the Late Devonian of Thailand. ''Siphonodella nandongensis'' is from the Early Carboniferous of the Baping Formation in China.New material of the ...

'' within the evolutionary lineage from ''

Siphonodella praesulcata'' to ''Siphonodella sulcata''. This was ratified by the ICS in 1990. However, in 2006 further study revealed the presence of ''Siphonodella sulcata'' below the boundary, and the presence of ''Siphonodella'' ''praesulcata'' and ''Siphonodella sulcata'' together above a local

unconformity

An unconformity is a buried erosional or non-depositional surface separating two rock masses or strata of different ages, indicating that sediment deposition was not continuous. In general, the older layer was exposed to erosion for an interval ...

. This means the evolution of one species to the other, the definition of the boundary, is not seen at the La Serre site making precise correlation difficult.

The Viséan Stage was introduced by André Dumont in 1832 and is named after the city of

Visé

Visé (; , ; ) is a city and municipality of Wallonia, located on the river Meuse in the province of Liège, Belgium.

The municipality consists of the following districts: Argenteau, Cheratte, Lanaye, Lixhe, Richelle, and Visé.

In the ...

,

Liège Province

Liège ( ; ; ; ; ) is the easternmost province of the Wallonia region of Belgium.

Liège Province is the only Belgian province that has borders with three countries. It borders (clockwise from the north) the Dutch province of Limburg, the ...

, Belgium. In 1967, the base of the Visean was officially defined as the first black limestone in the Leffe

facies

In geology, a facies ( , ; same pronunciation and spelling in the plural) is a body of rock with distinctive characteristics. The characteristics can be any observable attribute of rocks (such as their overall appearance, composition, or con ...

at the Bastion Section in the

Dinant Basin. These changes are now thought to be ecologically driven rather than caused by evolutionary change, and so this has not been used as the location for the GSSP. Instead, the GSSP for the base of the Visean is located in Bed 83 of the sequence of dark grey

limestone

Limestone is a type of carbonate rock, carbonate sedimentary rock which is the main source of the material Lime (material), lime. It is composed mostly of the minerals calcite and aragonite, which are different Polymorphism (materials science) ...

s and

shale

Shale is a fine-grained, clastic sedimentary rock formed from mud that is a mix of flakes of Clay mineral, clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g., Kaolinite, kaolin, aluminium, Al2Silicon, Si2Oxygen, O5(hydroxide, OH)4) and tiny f ...

s at the

Pengchong section,

Guangxi

Guangxi,; officially the Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, is an Autonomous regions of China, autonomous region of the China, People's Republic of China, located in South China and bordering Vietnam (Hà Giang Province, Hà Giang, Cao Bằn ...

, southern China. It is defined by the first appearance of the

fusulinid

The Fusulinida is an extinct order within the Foraminifera in which the tests are traditionally considered to have been composed of microgranular calcite. Like all forams, they were single-celled organisms. In advanced forms the test wall was d ...

''Eoparastaffella simplex'' in the evolutionary lineage ''Eoparastaffella ovalis – Eoparastaffella simplex'' and was ratified in 2009.

The Serpukhovian Stage was proposed in 1890 by Russian stratigrapher

Sergei Nikitin. It is named after the city of

Serpukhov

Serpukhov ( rus, Серпухов, p=ˈsʲerpʊxəf) is a types of inhabited localities in Russia, city in Moscow Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Oka River, Oka and the Nara (Oka), Nara Rivers, 99 kilometers (62 miles) south fro ...

, near Moscow and currently lacks a defined GSSP. The Visean-Serpukhovian boundary coincides with a major period of glaciation. The resulting sea level fall and climatic changes led to the loss of connections between marine basins and

endemism

Endemism is the state of a species being found only in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also foun ...

of marine fauna across the Russian margin. This means changes in

biota are environmental rather than evolutionary making wider correlation difficult.

Work is underway in the

Urals

The Ural Mountains ( ),; , ; , or simply the Urals, are a mountain range in Eurasia that runs north–south mostly through Russia, from the coast of the Arctic Ocean to the river Ural (river), Ural and northwestern Kazakhstan. and Nashui,

Guizhou

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption =

, image_map = Guizhou in China (+all claims hatched).svg

, mapsize = 275px

, map_alt = Map showing the location of Guizhou Province

, map_caption = Map s ...

Province, southwestern China for a suitable site for the GSSP with the proposed definition for the base of the Serpukhovian as the first appearance of conodont ''

Lochriea ziegleri.''

Pennsylvanian

The Pennsylvanian was proposed by

J.J.Stevenson in 1888, named after the widespread coal-rich strata found across the state of Pennsylvania.

The closure of the Rheic Ocean and formation of Pangea during the Pennsylvanian, together with widespread glaciation across

Gondwana

Gondwana ( ; ) was a large landmass, sometimes referred to as a supercontinent. The remnants of Gondwana make up around two-thirds of today's continental area, including South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia (continent), Australia, Zea ...

led to major climate and sea level changes, which restricted marine fauna to particular geographic areas thereby reducing widespread biostratigraphic correlations.

Extensive volcanic events associated with the assembling of Pangea means more radiometric dating is possible relative to the Mississippian.

The Bashkirian Stage was proposed by Russian stratigrapher

Sofia Semikhatova in 1934. It was named after

Bashkiria, the then Russian name of the republic of

Bashkortostan

Bashkortostan, officially the Republic of Bashkortostan, sometimes also called Bashkiria, is a republic of Russia between the Volga river and the Ural Mountains in Eastern Europe. The republic borders Perm Krai to the north, Sverdlovsk Oblast ...

in the southern Ural Mountains of Russia. The GSSP for the base of the Pennsylvanian Subsystem and Bashkirian Stage is located at

Arrow Canyon

An arrow is a fin-stabilized projectile launched by a bow. A typical arrow usually consists of a long, stiff, straight shaft with a weighty (and usually sharp and pointed) arrowhead attached to the front end, multiple fin-like stabilizers call ...

in

Nevada

Nevada ( ; ) is a landlocked state in the Western United States. It borders Oregon to the northwest, Idaho to the northeast, California to the west, Arizona to the southeast, and Utah to the east. Nevada is the seventh-most extensive, th ...

, US and was ratified in 1996. It is defined by the first appearance of the conodont ''

Declinognathodus noduliferus''. Arrow Canyon lay in a shallow, tropical seaway which stretched from Southern California to Alaska. The boundary is within a

cyclothem

In geology, cyclothems are alternating stratigraphy, stratigraphic sequences of marine and non-marine Sedimentary structures, sediments, sometimes interbedded with coal seams. The cyclothems consist of repeated sequences, each typically several m ...

sequence of

transgressive

Transgressive may mean:

*Transgressive art, a name given to art forms that violate perceived boundaries

*Transgressive fiction, a modern style in literature

*Transgressive Records, a United Kingdom-based independent record label

*Transgressive (l ...

limestones and fine

sandstone

Sandstone is a Clastic rock#Sedimentary clastic rocks, clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of grain size, sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate mineral, silicate grains, Cementation (geology), cemented together by another mineral. Sand ...

s, and

regressive mudstone

Mudstone, a type of mudrock, is a fine-grained sedimentary rock whose original constituents were clays or muds. Mudstone is distinguished from ''shale'' by its lack of fissility.Blatt, H., and R.J. Tracy, 1996, ''Petrology.'' New York, New York, ...

s and

breccia

Breccia ( , ; ) is a rock composed of large angular broken fragments of minerals or Rock (geology), rocks cementation (geology), cemented together by a fine-grained matrix (geology), matrix.

The word has its origins in the Italian language ...

ted limestones.

The Moscovian Stage is named after shallow marine limestones and colourful

clay

Clay is a type of fine-grained natural soil material containing clay minerals (hydrous aluminium phyllosilicates, e.g. kaolinite, ). Most pure clay minerals are white or light-coloured, but natural clays show a variety of colours from impuriti ...

s found around Moscow, Russia. It was first introduced by Sergei Nikitin in 1890. The Moscovian currently lacks a defined GSSP. The fusulinid ''Aljutovella aljutovica'' can be used to define the base of the Moscovian across the northern and eastern margins of Pangea, however, it is restricted in geographic area, which means it cannot be used for global correlations.

The first appearance of the conodonts ''Declinognathodus donetzianus'' or ''Idiognathoides postsulcatus'' have been proposed as a boundary marking species and potential sites in the Urals and Nashui, Guizhou Province, southwestern China are being considered.

The Kasimovian is the first stage in the Upper Pennsylvanian. It is named after the Russian city of

Kasimov

Kasimov (; ;, Ханкирмән Latinized : Kasıym, Hankirmən,Ханкирмән, Хан-Кермень, means " Khan's fortress" historically Gorodets Meshchyorsky, Novy Nizovoy) is a town in Ryazan Oblast, Russia, located on the left bank of ...

, and was originally included as part of Nikitin's 1890 definition of the Moscovian. It was first recognised as a distinct unit by A.P. Ivanov in 1926, who named it the "''Tiguliferina''" Horizon after a type of

brachiopod

Brachiopods (), phylum (biology), phylum Brachiopoda, are a phylum of animals that have hard "valves" (shells) on the upper and lower surfaces, unlike the left and right arrangement in bivalve molluscs. Brachiopod valves are hinged at the rear e ...

. The boundary of the Kasimovian covers a period of globally low sea level, which has resulted in

disconformities within many sequences of this age. This has created difficulties in finding suitable marine fauna that can used to correlate boundaries worldwide.

The Kasimovian currently lacks a defined GSSP; potential sites in the southern Urals, southwest USA and Nashui, Guizhou Province, southwestern China are being considered.

The Gzhelian is named after the Russian village of

Gzhel (selo), Moscow Oblast

Gzhel ( rus, Гжель, p=ɡʐelʲ) is a rural locality (a '' selo'') in Ramensky District of Moscow Oblast, Russia, located southeast from the center of Moscow. As of the 2010 Census, its population was 1,006.Moscow Oblast Territorial ...

, near

Ramenskoye, not far from Moscow. The name and type locality were defined by Sergei Nikitin in 1890. The Gzhelian currently lacks a defined GSSP. The first appearance of the fusulinid ''Rauserites rossicus'' and ''Rauserites'' ''stuckenbergi'' can be used in the

Boreal Sea and Paleo-Tethyan regions but not eastern Pangea or Panthalassa margins.

Potential sites in the Urals and Nashui, Guizhou Province, southwestern China for the GSSP are being considered.

The GSSP for the base of the Permian is located in the Aidaralash River valley near

Aqtöbe

Aktobe (, ; ) is a major city located on the Ilek River in western Kazakhstan. It serves as the administrative center of the Aktobe Region and is an important cultural, economic, and industrial hub in the region. As of 2023, the city has a popu ...

, Kazakhstan and was ratified in 1996. The beginning of the stage is defined by the first appearance of the conodont ''

Streptognathodus postfusus.''

Cyclothems

A cyclothem is a succession of non-marine and marine

sedimentary rock

Sedimentary rocks are types of rock (geology), rock formed by the cementation (geology), cementation of sediments—i.e. particles made of minerals (geological detritus) or organic matter (biological detritus)—that have been accumulated or de ...

s, deposited during a single sedimentary cycle, with an

erosional surface at its base. Whilst individual cyclothems are often only metres to a few tens of metres thick, cyclothem sequences can be many hundreds to thousands of metres thick and contain tens to hundreds of individual cyclothems.

Cyclothems were deposited along

continental shelves

A continental shelf is a portion of a continent that is submerged under an area of relatively shallow water, known as a shelf sea. Much of these shelves were exposed by drops in sea level during glacial periods. The shelf surrounding an island ...

where the very gentle gradient of the shelves meant even small changes in sea level led to large advances or retreats of the sea.

Cyclothem lithologies vary from

mudrock

Mudrocks are a class of fine-grained siliciclastic sedimentary rocks. The varying types of mudrocks include siltstone, claystone, mudstone and shale. Most of the particles of which the stone is composed are less than and are too small to ...

and carbonate-dominated to coarse siliciclastic sediment-dominated sequences depending on the paleo-topography, climate and supply of sediments to the shelf.

The main period of cyclothem deposition occurred during the

Late Paleozoic Ice Age from the Late Mississippian to early Permian, when the waxing and waning of

ice sheet

In glaciology, an ice sheet, also known as a continental glacier, is a mass of glacier, glacial ice that covers surrounding terrain and is greater than . The only current ice sheets are the Antarctic ice sheet and the Greenland ice sheet. Ice s ...

s led to rapid changes in

eustatic sea level

The eustatic sea level (from Greek εὖ ''eû'', "good" and στάσις ''stásis'', "standing") is the distance from the center of the Earth to the sea surface. An increase of the eustatic sea level can be generated by decreasing glaciation, inc ...

.

The growth of ice sheets led global sea levels to fall as water was locked away in glaciers. Falling sea levels exposed large tracts of the continental shelves across which river systems eroded channels and valleys and vegetation broke down the surface to form

soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, water, and organisms that together support the life of plants and soil organisms. Some scientific definitions distinguish dirt from ''soil'' by re ...

s. The non-marine sediments deposited on this erosional surface form the base of the cyclothem.

As sea levels began to rise, the rivers flowed through increasingly water-logged landscapes of swamps and lakes.

Peat mires developed in these wet and oxygen-poor conditions, leading to coal formation.

With continuing sea level rise, coastlines migrated landward and

deltas

A river delta is a landform, wikt:archetype#Noun, archetypically triangular, created by the deposition (geology), deposition of the sediments that are carried by the waters of a river, where the river merges with a body of slow-moving water or ...

,

lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') an ...

s and

esturaries developed; their sediments deposited over the peat mires. As fully marine conditions were established, limestones succeeded these marginal marine deposits. The limestones were in turn overlain by deep water black shales as maximum sea levels were reached.

Ideally, this sequence would be reversed as sea levels began to fall again; however, sea level falls tend to be protracted, whilst sea level rises are rapid, ice sheets grow slowly but melt quickly. Therefore, the majority of a cyclothem sequence occurred during falling sea levels, when rates of

erosion

Erosion is the action of surface processes (such as Surface runoff, water flow or wind) that removes soil, Rock (geology), rock, or dissolved material from one location on the Earth's crust#Crust, Earth's crust and then sediment transport, tran ...

were high, meaning they were often periods of non-deposition. Erosion during sea level falls could also result in the full or partial removal of previous cyclothem sequences. Individual cyclothems are generally less than 10 m thick because the speed at which sea level rose gave only limited time for sediments to accumulate.

During the Pennsylvanian, cyclothems were deposited in shallow,

epicontinental seas across the tropical regions of

Laurussia

Laurasia () was the more northern of two large landmasses that formed part of the Pangaea supercontinent from around (Million years ago, Mya), the other being Gondwana. It separated from Gondwana (beginning in the late Triassic period) during ...

(present day western and central US, Europe, Russia and central Asia) and the

North

North is one of the four compass points or cardinal directions. It is the opposite of south and is perpendicular to east and west. ''North'' is a noun, adjective, or adverb indicating Direction (geometry), direction or geography.

Etymology

T ...

and

South China cratons

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþaz' ...

.

The rapid sea levels fluctuations they represent correlate with the glacial cycles of the Late Paleozoic Ice Age. The advance and retreat of ice sheets across Gondwana followed a 100 kyr

Milankovitch cycle

Milankovitch cycles describe the collective effects of changes in the Earth's movements on its climate over thousands of years. The term was coined and named after the Serbian geophysicist and astronomer Milutin Milanković. In the 1920s, he pr ...

, and so each cyclothem represents a cycle of sea level fall and rise over a 100 kyr period.

Coal formation

Coal forms when organic matter builds up in waterlogged,

anoxic

Anoxia means a total depletion in the level of oxygen, an extreme form of hypoxia or "low oxygen". The terms anoxia and hypoxia are used in various contexts:

* Anoxic waters, sea water, fresh water or groundwater that are depleted of dissolved ox ...

swamps, known as peat mires, and is then buried, compressing the peat into coal. The majority of Earth's coal deposits were formed during the late Carboniferous and early Permian. The plants from which they formed contributed to changes in the Carboniferous Earth's atmosphere.

During the Pennsylvanian, vast amounts of organic debris accumulated in the peat mires that formed across the low-lying, humid equatorial wetlands of the

foreland basin

A foreland basin is a structural basin that develops adjacent and parallel to a mountain belt. Foreland basins form because the immense mass created by crustal thickening associated with the evolution of a mountain belt causes the lithospher ...

s of the

Central Pangean Mountains

The Central Pangean Mountains were an extensive northeast–southwest trending mountain range in the central portion of the supercontinent Pangaea during the Carboniferous, Permian and Triassic periods. They were formed as a result of collision be ...

in Laurussia, and around the margins of the North and South China cratons.

During glacial periods, low sea levels exposed large areas of the continental shelves. Major river channels, up to several kilometres wide, stretched across these shelves feeding a network of smaller channels, lakes and peat mires.

These wetlands were then buried by sediment as sea levels rose during

interglacial

An interglacial period (or alternatively interglacial, interglaciation) is a geological interval of warmer global average temperature lasting thousands of years that separates consecutive glacial periods within an ice age. The current Holocene i ...

s. Continued crustal

subsidence

Subsidence is a general term for downward vertical movement of the Earth's surface, which can be caused by both natural processes and human activities. Subsidence involves little or no horizontal movement, which distinguishes it from slope mov ...

of the foreland basins and continental margins allowed this accumulation and burial of peat deposits to continue over millions of years resulting in the formation of thick and widespread coal formations.

During the warm interglacials, smaller coal swamps with plants adapted to the temperate conditions formed on the

Siberian craton

Siberia, also known as Siberian Craton, Angaraland (or simply Angara) and Angarida, is an ancient craton in the heart of Siberia. Today forming the Central Siberian Plateau, it formed an independent landmass prior to its fusion into Pangea during ...

and the western Australian region of Gondwana.

There is ongoing debate as to why this peak in the formation of Earth's coal deposits occurred during the Carboniferous. The first theory, known as the delayed fungal evolution hypothesis, is that a delay between the development of trees with the wood fibre

lignin

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants. Lignins are particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because they lend rigidit ...

and the subsequent evolution of lignin-degrading fungi gave a period of time where vast amounts of lignin-based organic material could accumulate. Genetic analysis of

basidiomycete

Basidiomycota () is one of two large divisions that, together with the Ascomycota, constitute the subkingdom Dikarya (often referred to as the "higher fungi") within the kingdom Fungi. Members are known as basidiomycetes. More specifically, Basid ...

fungi, which have

enzyme

An enzyme () is a protein that acts as a biological catalyst by accelerating chemical reactions. The molecules upon which enzymes may act are called substrate (chemistry), substrates, and the enzyme converts the substrates into different mol ...

s capable of breaking down lignin, supports this theory by suggesting this fungi evolved in the Permian. However, significant Mesozoic and Cenozoic coal deposits formed after lignin-digesting fungi had become well established, and fungal degradation of lignin may have already evolved by the end of the Devonian, even if the specific enzymes used by basidiomycetes had not.

The second theory is that the geographical setting and climate of the Carboniferous were unique in Earth's history: the co-occurrence of the position of the continents across the humid equatorial zone, high biological productivity, and the low-lying, water-logged and slowly subsiding sedimentary basins that allowed the thick accumulation of peat were sufficient to account for the peak in coal formation.

Palaeogeography

During the Carboniferous, there was an increased rate in

tectonic plate

Plate tectonics (, ) is the scientific theory that the Earth's lithosphere comprises a number of large tectonic plates, which have been slowly moving since 3–4 billion years ago. The model builds on the concept of , an idea developed durin ...

movements as the

supercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continent, continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", ...

Pangea assembled. The continents themselves formed a near circle around the opening Paleo-Tethys Ocean, with the massive

Panthalassic Ocean beyond. Gondwana covered the

south polar region. To its northwest was Laurussia. These two continents slowly collided to form the core of Pangea. To the north of Laurussia lay

Siberia

Siberia ( ; , ) is an extensive geographical region comprising all of North Asia, from the Ural Mountains in the west to the Pacific Ocean in the east. It has formed a part of the sovereign territory of Russia and its predecessor states ...

and

Amuria

Amuria is a town in the Eastern Region of Uganda. It is the chief municipal, administrative, and commercial center of Amuria District, in the Teso sub-region.

Location

Amuria is located , by road, north of Soroti, the largest city in the Tes ...

. To the east of Siberia,

Kazakhstania

Kazakhstania (), the Kazakh terranes, or the Kazakhstan Block, is a geological region in Central Asia which consists of the area roughly centered on Lake Balkhash, north and east of the Aral Sea, south of the Siberian craton and west of the Alta ...

, North China and South China formed the northern margin of the Paleo-Tethys, with Annamia laying to the south.

Variscan-Alleghanian-Ouachita orogeny

The Central Pangean Mountains were formed during the

Variscan

The Variscan orogeny, or Hercynian orogeny, was a geologic mountain-building event caused by Late Paleozoic continental collision between Euramerica (Laurussia) and Gondwana to form the supercontinent of Pangaea.

Nomenclature

The name ''Variscan ...

-

Alleghanian-

Ouachita orogeny. Today their remains stretch over 10,000 km from the

Gulf of Mexico

The Gulf of Mexico () is an oceanic basin and a marginal sea of the Atlantic Ocean, mostly surrounded by the North American continent. It is bounded on the northeast, north, and northwest by the Gulf Coast of the United States; on the southw ...

in the west to

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

in the east.

The orogeny was caused by a series of continental collisions between Laurussia, Gondwana and the

Armorican terrane assemblage (much of modern-day Central and Western Europe including

Iberia

The Iberian Peninsula ( ), also known as Iberia, is a peninsula in south-western Europe. Mostly separated from the rest of the European landmass by the Pyrenees, it includes the territories of peninsular Spain and Continental Portugal, compri ...

) as the

Rheic Ocean

The Rheic Ocean (; ) was an ocean which separated two major paleocontinents, Gondwana and Laurussia ( Laurentia- Baltica- Avalonia). One of the principal oceans of the Paleozoic, its sutures today stretch from Mexico to Turkey and its closure r ...

closed and Pangea formed. This mountain building process began in the Middle Devonian and continued into the early Permian.

The Armorican

terrane

In geology, a terrane (; in full, a tectonostratigraphic terrane) is a crust fragment formed on a tectonic plate (or broken off from it) and accreted or " sutured" to crust lying on another plate. The crustal block or fragment preserves its d ...

s

rift

In geology, a rift is a linear zone where the lithosphere is being pulled apart and is an example of extensional tectonics. Typical rift features are a central linear downfaulted depression, called a graben, or more commonly a half-graben ...

ed away from Gondwana during the Late

Ordovician

The Ordovician ( ) is a geologic period and System (geology), system, the second of six periods of the Paleozoic Era (geology), Era, and the second of twelve periods of the Phanerozoic Eon (geology), Eon. The Ordovician spans 41.6 million years f ...

. As they drifted northwards the Rheic Ocean closed in front of them, and they began to collide with southeastern Laurussia in the Middle Devonian.

The resulting Variscan orogeny involved a complex series of oblique collisions with associated

metamorphism

Metamorphism is the transformation of existing Rock (geology), rock (the protolith) to rock with a different mineral composition or Texture (geology), texture. Metamorphism takes place at temperatures in excess of , and often also at elevated ...

,

igneous

Igneous rock ( ), or magmatic rock, is one of the three main rock types, the others being sedimentary and metamorphic. Igneous rocks are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

The magma can be derived from partial ...

activity, and large-scale

deformation between these terranes and Laurussia, which continued into the Carboniferous.

During the mid Carboniferous, the South American sector of Gondwana collided obliquely with Laurussia's southern margin resulting in the Ouachita orogeny.

The major

strike-slip faulting

In geology, a fault is a Fracture (geology), planar fracture or discontinuity in a volume of Rock (geology), rock across which there has been significant displacement as a result of rock-mass movements. Large faults within Earth's crust (geology ...

that occurred between Laurussia and Gondwana extended eastwards into the

Appalachian Mountains

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, are a mountain range in eastern to northeastern North America. The term "Appalachian" refers to several different regions associated with the mountain range, and its surrounding terrain ...

where early deformation in the Alleghanian orogeny was predominantly strike-slip. As the West African sector of Gondwana collided with Laurussia during the Late Pennsylvanian, deformation along the Alleghanian orogen became northwesterly-directed

compression

Compression may refer to:

Physical science

*Compression (physics), size reduction due to forces

*Compression member, a structural element such as a column

*Compressibility, susceptibility to compression

* Gas compression

*Compression ratio, of a ...

.

Uralian orogeny

The

Uralian orogeny

The Uralian orogeny refers to the long series of linear deformation and mountain building events that raised the Ural Mountains, starting in the Late Carboniferous and Permian periods of the Palaeozoic Era, 323–299 and 299–251 million years ...

is a north–south trending

fold and thrust belt

A fold and thrust belt is a series of mountainous foothills adjacent to an orogenic belt, which forms due to contractional tectonics. Fold and thrust belts commonly form in the forelands adjacent to major orogens as deformation propagates outwards ...

that forms the western edge of the

Central Asian Orogenic Belt.

The Uralian orogeny began in the Late Devonian and continued, with some hiatuses, into the

Jurassic

The Jurassic ( ) is a Geological period, geologic period and System (stratigraphy), stratigraphic system that spanned from the end of the Triassic Period million years ago (Mya) to the beginning of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 143.1 Mya. ...

. From the Late Devonian to early Carboniferous, the

Magnitogorsk

Magnitogorsk ( rus, Магнитого́рск, p=məɡnʲɪtɐˈɡorsk, ) is an industrial city in Chelyabinsk Oblast, Russia, on the eastern side of the extreme southern extent of the Ural Mountains by the Ural River. Its population is curre ...

island arc

Island arcs are long archipelago, chains of active volcanoes with intense earthquake, seismic activity found along convergent boundary, convergent plate tectonics, tectonic plate boundaries. Most island arcs originate on oceanic crust and have re ...

, which lay between Kazakhstania and Laurussia in the

Ural Ocean, collided with the

passive margin

A passive margin is the transition between Lithosphere#Oceanic lithosphere, oceanic and Lithosphere#Continental lithosphere, continental lithosphere that is not an active plate continental margin, margin. A passive margin forms by sedimentatio ...

of northeastern Laurussia (

Baltica craton). The

suture zone between the former island arc complex and the continental margin formed the

Main Uralian Fault

The Main Uralian Fault (MUF) runs north–south through the middle of the Ural Mountains for over 2,000 km. It separates both Europe from Asia and the three, or four, western megazones of the Urals from the three eastern megazones: namel ...

, a major structure that runs for more than 2,000 km along the orogen.

Accretion

Accretion may refer to:

Science

* Accretion (astrophysics), the formation of planets and other bodies by collection of material through gravity

* Accretion (meteorology), the process by which water vapor in clouds forms water droplets around nucl ...

of the island arc was complete by the Tournaisian, but subduction of the Ural Ocean between Kazakhstania and Laurussia continued until the Bashkirian when the ocean finally closed and continental collision began.

Significant strike-slip movement along this zone indicates the collision was oblique. Deformation continued into the Permian and during the late Carboniferous and Permian the region was extensively intruded by

granite

Granite ( ) is a coarse-grained (phanerite, phaneritic) intrusive rock, intrusive igneous rock composed mostly of quartz, alkali feldspar, and plagioclase. It forms from magma with a high content of silica and alkali metal oxides that slowly coo ...

s.

Laurussia

The Laurussian continent was formed by the collision between

Laurentia

Laurentia or the North American craton is a large continental craton that forms the Geology of North America, ancient geological core of North America. Many times in its past, Laurentia has been a separate continent, as it is now in the form of ...

,

Baltica

Baltica is a paleocontinent that formed in the Paleoproterozoic and now constitutes northwestern Eurasia, or Europe north of the Trans-European Suture Zone and west of the Ural Mountains.

The thick core of Baltica, the East European Craton, i ...

and

Avalonia

Avalonia was a microcontinent in the Paleozoic era. Crustal fragments of this former microcontinent are terranes in parts of the eastern coast of North America: Atlantic Canada, and parts of the East Coast of the United States, East Coast of the ...

during the Devonian. At the beginning of the Carboniferous, some models show it at the equator, while others place it further south. In either case, the continent drifted northwards, reaching low latitudes in the northern hemisphere by the end of the Period.

The Central Pangean Mountain drew in moist air from the Paleo-Tethys Ocean resulting in heavy precipitation and a tropical wetland environment. Extensive coal deposits developed within the cyclothem sequences that dominated the Pennsylvanian

sedimentary basin

Sedimentary basins are region-scale depressions of the Earth's crust where subsidence has occurred and a thick sequence of sediments have accumulated to form a large three-dimensional body of sedimentary rock They form when long-term subsidence ...

s associated with the growing orogenic belt.

Subduction of the

Panthalassic

Panthalassa, also known as the Panthalassic Ocean or Panthalassan Ocean (from Greek "all" and "sea"), was the vast superocean that encompassed planet Earth and surrounded the supercontinent Pangaea, the latest in a series of supercontinents ...

oceanic plate along its western margin resulted in the

Antler orogeny in the Late Devonian to Early Mississippian. Further north along the margin,

slab roll-back, beginning in the Early Mississippian, led to the rifting of the

Yukon–Tanana terrane and the opening of the

Slide Mountain Ocean

The Slide Mountain Ocean was an ancient ocean that existed between the Intermontane Islands and North America beginning around 245 million years ago in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ; sometimes symbolized 🝈) is a geologic period and system ...

. Along the northern margin of Laurussia,

orogenic collapse

In geology, orogenic collapse is the thinning and lateral spread of thickened crust. It is a broad term referring to processes which distribute material from regions of high gravitational potential energy to regions of low gravitational potential ...

of the Late Devonian to Early Mississippian

Innuitian orogeny

The Innuitian orogeny, sometimes called the Ellesmere orogeny, was a major tectonic orogeny (mountain building episode) of the late Devonian to early Carboniferous, responsible for the formation of a series of mountain ranges in the Canadian Arcti ...

led to the development of the

Sverdrup Basin.

Gondwana

Much of Gondwana lay in the southern polar region during the Carboniferous. As the plate moved, the South Pole drifted from southern Africa in the early Carboniferous to eastern Antarctica by the end of the period.

Glacial deposits

image:Geschiebemergel.JPG, Closeup of glacial till. Note that the larger grains (pebbles and gravel) in the till are completely surrounded by the matrix of finer material (silt and sand), and this characteristic, known as ''matrix support'', is d ...

are widespread across Gondwana and indicate multiple ice centres and long-distance movement of ice.

The northern to northeastern margin of Gondwana (northeast Africa, Arabia, India and northeastern West Australia) was a passive margin along the southern edge of the Paleo-Tethys with cyclothem deposition including, during more temperate intervals, coal swamps in Western Australia.

The Mexican terranes along the northwestern Gondwana margin, were affected by the subduction of the Rheic Ocean.

However, they lay to west of the Ouachita orogeny and were not impacted by continental collision but became part of the active margin of the Pacific.

The Moroccan margin was affected by periods of widespread dextral strike-slip deformation, magmatism and metamorphism associated with the Variscan orogeny.

Towards the end of the Carboniferous, extension and rifting across the northern margin of Gondwana led to the breaking away of the

Cimmerian terrane

Cimmeria ( ) was an ancient continent, or, rather, a string of microcontinents or terranes, that rifted from Gondwana in the Southern Hemisphere and was accreted to Eurasia in the Northern Hemisphere. It consisted of parts of present-day Turke ...

during the early Permian and the opening of the

Neo-Tethys Ocean.

Along the southeastern and southern margin of Gondwana (eastern Australia and Antarctica), northward subduction of Panthalassa continued. Changes in the relative motion of the plates resulted in the early Carboniferous

Kanimblan Orogeny

The Kanimblan orogeny was a mountain-building event in eastern Australia toward the end of Early Carboniferous time (about 318 million years ago). It was a terminal orogenic episode forming the Lachlan Fold Belt, which was also known as the Lach ...

.

Continental arc

A continental arc is a type of volcanic arc occurring as an "arc-shape" topographic high region along a continental margin. The continental arc is formed at an active continental margin where two tectonic plates meet, and where one plate has conti ...

magmatism continued into the late Carboniferous and extended round to connect with the developing

proto-Andean subduction zone along the western South American margin of Gondwana.

Siberia and Amuria

Shallow seas covered much of the Siberian craton in the early Carboniferous. These retreated as sea levels fell in the Pennsylvanian and as the continent drifted north into more temperate zones extensive coal deposits formed in the

Kuznetsk Basin

The Kuznetsk Basin (, Кузбасс; often abbreviated as Kuzbass or Kuzbas) in southwestern Siberia, Russia, is one of the largest coal mining areas in Russia, covering an area of around . It lies in the Kuznetsk Depression between Tomsk and ...

.

The northwest to eastern margins of Siberia were passive margins along the Mongol-Okhotsk Ocean on the far side of which lay Amuria. From the mid Carboniferous, subduction zones with associated magmatic arcs developed along both margins of the ocean.

The southwestern margin of Siberia was the site of a long lasting and complex accretionary orogen. The Devonian to early Carboniferous Siberian and South Chinese

Altai accretionary complexes developed above an east-dipping subduction zone, whilst further south, the Zharma-Saur arc formed along the northeastern margin of Kazakhstania. By the late Carboniferous, all these complexes had accreted to the Siberian craton as shown by the intrusion of post-orogenic granites across the region. As Kazakhstania had already accreted to Laurussia, Siberia was effectively part of Pangea by 310 Ma, although major strike-slip movements continued between it and Laurussia into the Permian.

Central and East Asia

The Kazakhstanian microcontinent is composed of a series of Devonian and older accretionary complexes. It was strongly deformed during the Carboniferous as its western margin collided with Laurussia during the Uralian orogen and its northeastern margin collided with Siberia. Continuing strike-slip motion between Laurussia and Siberia led the formerly elongate microcontinent to bend into an

orocline

An orocline — from the Greek words for "mountain" and "to bend" — is a bend or curvature of an orogenic (mountain building) belt imposed after it was formed. The term was introduced by S. Warren Carey in 1955 in a paper setting forth how comp ...

.

During the Carboniferous, the Tarim craton lay along the northwestern edge of North China. Subduction along the Kazakhstanian margin of the Turkestan Ocean resulted in collision between northern Tarim and Kazakhstania during the mid Carboniferous as the ocean closed. The

South Tian Shan fold and thrust belt, which extends over 2,000 km from

Uzbekistan

, image_flag = Flag of Uzbekistan.svg

, image_coat = Emblem of Uzbekistan.svg

, symbol_type = Emblem of Uzbekistan, Emblem

, national_anthem = "State Anthem of Uzbekistan, State Anthem of the Republ ...

to northwest China, is the remains of this accretionary complex and forms the suture between Kazakhstania and Tarim.

A continental magmatic arc above a south-dipping subduction zone lay along the northern North China margin, consuming the Paleoasian Ocean.

Northward subduction of the Paleo-Tethys beneath the southern margins of North China and Tarim continued during the Carboniferous, with the

South Qinling block accreted to North China during the mid to late Carboniferous.

No sediments are preserved from the early Carboniferous in North China. However,

bauxite

Bauxite () is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)), and diaspore (α-AlO(OH) ...

deposits immediately above the regional mid Carboniferous unconformity indicate warm tropical conditions and are overlain by cyclothems including extensive coals.

South China and Annamia (Southeast Asia) rifted from Gondwana during the Devonian.

During the Carboniferous, they were separated from each other and North China by the Paleoasian Ocean with the Paleo-Tethys to the southwest and Panthalassa to the northeast. Cyclothem sediments with coal and

evaporite

An evaporite () is a water- soluble sedimentary mineral deposit that results from concentration and crystallization by evaporation from an aqueous solution. There are two types of evaporite deposits: marine, which can also be described as oce ...

s were deposited across the passive margins that surrounded both continents.

Climate

The Carboniferous climate was dominated by the Late Paleozoic Ice Age (LPIA), the most extensive and longest icehouse period of the Phanerozoic, which lasted from the Late Devonian to the Permian (365 Ma-253 Ma).

Temperatures began to drop during the late Devonian with a short-lived glaciation in the late Famennian through Devonian–Carboniferous boundary,

before the Early Tournaisian Warm Interval.

Following this, a reduction in atmospheric CO

2 levels, caused by the increased burial of organic matter and widespread ocean anoxia led to climate cooling and glaciation across the south polar region.

During the Visean Warm Interval glaciers nearly vanished retreating to the proto-Andes in Bolivia and western Argentina and the Pan-African mountain ranges in southeastern Brazil and southwest Africa.

The main phase of the LPIA (c. 335–290 Ma) began in the late Visean, as the climate cooled and atmospheric CO

2 levels dropped. Its onset was accompanied by a global fall in sea level and widespread multimillion-year unconformities.

This main phase consisted of a series of discrete several million-year-long glacial periods during which ice expanded out from up to 30 ice centres that stretched across mid- to high latitudes of Gondwana in eastern Australia, northwestern Argentina, southern Brazil, and central and Southern Africa.

Isotope records indicate this drop in CO

2 levels was triggered by tectonic factors with increased weathering of the growing Central Pangean Mountains and the influence of the mountains on precipitation and surface water flow.

Closure of the oceanic gateway between the Rheic and Tethys oceans in the early Bashkirian also contributed to climate cooling by changing ocean circulation and heat flow patterns.

Warmer periods with reduced ice volume within the Bashkirian, the late Moscovian and the latest Kasimovian to mid-Gzhelian are inferred from the disappearance of glacial sediments, the appearance of deglaciation deposits and rises in sea levels.

In the early Kasimovian there was short-lived (<1 million years) intense period of glaciation, with atmospheric CO

2 concentration levels dropping as low as 180 ppm.

This ended suddenly as a rapid increase in CO

2 concentrations to c. 600 ppm resulted in a warmer climate. This rapid rise in CO

2 may have been due to a peak in pyroclastic volcanism and/or a reduction in burial of terrestrial organic matter.

The LPIA peaked across the Carboniferous-Permian boundary. Widespread glacial deposits are found across South America, western and central Africa, Antarctica, Australia, Tasmania, the Arabian Peninsula, India, and the Cimmerian blocks, indicating trans-continental ice sheets across southern Gondwana that reached to sea-level.

In response to the uplift and erosion of the more mafic basement rocks of the Central Pangea Mountains at this time, CO

2 levels dropped as low as 175 ppm and remained under 400 ppm for 10 Ma.

Temperatures

Temperatures across the Carboniferous reflect the phases of the LPIA. At the extremes, during the Permo-Carboniferous Glacial Maximum (299–293 Ma) the global average temperature (GAT) was c. 13 °C (55 °F), the average temperature in the tropics c. 24 °C (75 °F) and in polar regions c. -23 °C (-10 °F), whilst during the Early Tournaisian Warm Interval (358–353 Ma) the GAT was c. 22 °C (72 °F), the tropics c. 30 °C (86 °F) and polar regions c. 1.5 °C (35 °F). Overall, for the Ice Age the GAT was c. 17 °C (62 °F), with tropical temperatures c. 26 °C and polar temperatures c. -9.0 °C (16 °F).

Atmospheric oxygen levels

There are a variety of methods for reconstructing past atmospheric oxygen levels, including the

charcoal

Charcoal is a lightweight black carbon residue produced by strongly heating wood (or other animal and plant materials) in minimal oxygen to remove all water and volatile constituents. In the traditional version of this pyrolysis process, ca ...

record,

halite

Halite ( ), commonly known as rock salt, is a type of salt, the mineral (natural) form of sodium chloride ( Na Cl). Halite forms isometric crystals. The mineral is typically colorless or white, but may also be light blue, dark blue, purple, pi ...

gas inclusions, burial rates of organic carbon and

pyrite

The mineral pyrite ( ), or iron pyrite, also known as fool's gold, is an iron sulfide with the chemical formula Fe S2 (iron (II) disulfide). Pyrite is the most abundant sulfide mineral.

Pyrite's metallic luster and pale brass-yellow hue ...

, carbon isotopes of organic material, isotope mass balance and forward modelling.

Depending on the preservation of source material, some techniques represent moments in time (e.g. halite gas inclusions),

whilst others have a wider time range (e.g. the charcoal record and pyrite).

Results from these different methods for the Carboniferous vary.

For example: the increasing occurrence of charcoal produced by wildfires from the Late Devonian into the Carboniferous indicates increasing oxygen levels, with calculations showing oxygen levels above 21% for most of the Carboniferous;

halite gas inclusions from sediments dated 337–335 Ma give estimates for the Visean of c. 15.3%, although with large uncertainties;

and, pyrite records suggest levels of c. 15% early in the Carboniferous, to over 25% during the Pennsylvanian, before dropping back below 20% towards the end.

However, whilst exact numbers vary, all models show an overall increase in atmospheric oxygen levels from a low of between 15 and 20% at the beginning of the Carboniferous to highs of 25–30% during the Period. This was not a steady rise, but included peaks and troughs reflecting the dynamic climate conditions of the time.

How the atmospheric oxygen concentrations influenced the large body size of arthropods and other fauna and flora during the Carboniferous is also a subject of ongoing debate.

Effects of climate on sedimentation

The changing climate was reflected in regional-scale changes in sedimentation patterns. In the relatively warm waters of the Early to Middle Mississippian, carbonate production occurred to depth across the gently dipping continental slopes of Laurussia and North and South China (

carbonate ramp architecture)

and evaporites formed around the coastal regions of Laurussia, Kazakhstania, and northern Gondwana.

From the late Visean, the cooling climate restricted carbonate production to depths of less than c. 10 m forming

carbonate shelves with flat-tops and steep sides. By the Moscovian, the waxing and waning of the ice sheets led to cyclothem deposition with mixed carbonate-siliciclastic sequences deposited on continental platforms and shelves.

Seasonal melting of glaciers resulted in near freezing waters around the margins of Gondwana. This is evidenced by the occurrence of glendonite (a pseudomorph of

ikaite

Ikaite is the mineral name for the hexahydrate of calcium carbonate, . Ikaite tends to form very steep or spiky pyramidal crystals, often radially arranged, of varied sizes from thumbnail size aggregates to gigantic salient spurs. It is only fo ...