Azendohsaurus on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''Azendohsaurus'' is an extinct

The skull of ''A. madagaskarensis'' is almost completely known, and is robustly built with a short and boxy shape and a deep

The skull of ''A. madagaskarensis'' is almost completely known, and is robustly built with a short and boxy shape and a deep  The lower jaw is especially convergent with those of sauropodomorphs, with an articular joint where the jaw hinges positioned below the level of the tooth row and downward curving dentaries, as well as the similarly shaped teeth. These features are variously found in other herbivorous Triassic archosauromorphs, but this combination is only known in ''Azendohsaurus'' and sauropodomorphs.

The teeth are all roughly leaf-shaped (lanceolate) with expanded crowns and bulbous bases that are fused to the jaw bones (ankylothecodont). However, the upper and lower teeth are distinctly

The lower jaw is especially convergent with those of sauropodomorphs, with an articular joint where the jaw hinges positioned below the level of the tooth row and downward curving dentaries, as well as the similarly shaped teeth. These features are variously found in other herbivorous Triassic archosauromorphs, but this combination is only known in ''Azendohsaurus'' and sauropodomorphs.

The teeth are all roughly leaf-shaped (lanceolate) with expanded crowns and bulbous bases that are fused to the jaw bones (ankylothecodont). However, the upper and lower teeth are distinctly  The

The

The dorsal vertebrae of the back generally resemble the last cervicals, with tall, vertical neural spines. These vertebrae also decrease in length down the back, but less dramatically than in the neck. The last dorsal is unique, however, as it has a neural spine angled forward. Of the two sacrals, the first vertebra is larger and more robust, with a tall neural spines over its rear half. Both sacrals have large ribs completely fused to the vertebrae that articulate with the ilia (see below).

The caudal vertebrae resemble the other vertebrae, but with backward inclined neural spines. The length of the caudals and the height of the neural spines gradually decreases down the tail, unlike some other archosauromorphs where the vertebrae elongate towards the tip. This implies that the tail was short and not tapering, but the very tip of the tail is unknown. They consistently have chevron facets from the 3rd or 4th vertebrae down to the last known caudals in the series.

The cervical ribs are long and thin, becoming more robust and tapered as they move down the neck. Some of the cervical ribs from bottom half of the neck have a slight facet on the inside surface at their tips that may have held the tip of the preceding rib, forming a rigid cervical rib series (also suggested for the long necked ''

The dorsal vertebrae of the back generally resemble the last cervicals, with tall, vertical neural spines. These vertebrae also decrease in length down the back, but less dramatically than in the neck. The last dorsal is unique, however, as it has a neural spine angled forward. Of the two sacrals, the first vertebra is larger and more robust, with a tall neural spines over its rear half. Both sacrals have large ribs completely fused to the vertebrae that articulate with the ilia (see below).

The caudal vertebrae resemble the other vertebrae, but with backward inclined neural spines. The length of the caudals and the height of the neural spines gradually decreases down the tail, unlike some other archosauromorphs where the vertebrae elongate towards the tip. This implies that the tail was short and not tapering, but the very tip of the tail is unknown. They consistently have chevron facets from the 3rd or 4th vertebrae down to the last known caudals in the series.

The cervical ribs are long and thin, becoming more robust and tapered as they move down the neck. Some of the cervical ribs from bottom half of the neck have a slight facet on the inside surface at their tips that may have held the tip of the preceding rib, forming a rigid cervical rib series (also suggested for the long necked ''

The forelimbs and shoulders (pectoral girdle) of ''Azendohsaurus'' are well developed and robust. The

The forelimbs and shoulders (pectoral girdle) of ''Azendohsaurus'' are well developed and robust. The

Even preliminary examination of the rest of the skull and skeleton from the Madagascan species confirmed that ''Azendohsaurus'' was not a dinosaur, and was instead an aberrant herbivorous archosauromorph that was only distantly related to dinosaurs, let alone sauropodomorphs. A description of the cranial material was published first in May, 2010 by John J. Flynn and colleagues, who also officially named and diagnosed it as a new species of ''Azendohsaurus'', ''Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis'', named for its country of origin. This was also the first time ''Azendohsaurus'' was determined to be a non-dinosaur in the published literature.

In December, 2015, the rest of the skeleton of ''A. madagaskarensis'' was formally described and published by

Even preliminary examination of the rest of the skull and skeleton from the Madagascan species confirmed that ''Azendohsaurus'' was not a dinosaur, and was instead an aberrant herbivorous archosauromorph that was only distantly related to dinosaurs, let alone sauropodomorphs. A description of the cranial material was published first in May, 2010 by John J. Flynn and colleagues, who also officially named and diagnosed it as a new species of ''Azendohsaurus'', ''Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis'', named for its country of origin. This was also the first time ''Azendohsaurus'' was determined to be a non-dinosaur in the published literature.

In December, 2015, the rest of the skeleton of ''A. madagaskarensis'' was formally described and published by

''Azendohsaurus'' was first misidentified as an ornithischian dinosaur by Dutuit, based on shared characteristics of its teeth such as the leaf-like shape and the number of denticles. It was later believed to be a sauropodomorph instead by other researchers, assigned to the defunct infraorder "Prosauropoda" (then believed to be a distinct

''Azendohsaurus'' was first misidentified as an ornithischian dinosaur by Dutuit, based on shared characteristics of its teeth such as the leaf-like shape and the number of denticles. It was later believed to be a sauropodomorph instead by other researchers, assigned to the defunct infraorder "Prosauropoda" (then believed to be a distinct

In 2017, another large allokotosaur was described from the Middle Triassic of

In 2017, another large allokotosaur was described from the Middle Triassic of

The leaf-shaped teeth of ''Azendohsaurus'' are clearly suited for a herbivorous lifestyle, and microwear—marks left on the tooth surface during feeding—on the teeth of ''A. madagaskarensis'' suggest they were used for browsing on vegetation that was not especially tough or woody, preferring softer (but firm) vegetation. The microwear patterns also show that it used a simple up-and-down motion of the jaw, and did not use complex jaw movement to chew its food like ornithischian dinosaurs or contemporary cynodonts. This microwear has not yet been observed on the teeth of ''A. laaroussii'', but it is unknown if this is a genuine feature relating to a difference in diet and feeding habits between the two species or if it is just a feature of preservation.

The fully developed palatal teeth suggest that it was using them for feeding in a specialised manner. However, no functional studies have been performed on the palatal teeth so it is unknown exactly what they were used for, although their similar shape to the marginal teeth suggests they were used for processing similar food. A pterygoid from a younger individual of ''A. madagaskarensis'' has fewer rows of palatal teeth that are smaller in size than those of the larger, mature individuals, indicating that ''Azendohsaurus'' increased both the number and size of its palatal teeth as it grew into adulthood. Younger individuals also had fewer dentary teeth than adults, although the difference was much less extreme compared to the palatal teeth (16 compared to the 17 of mature specimens).

The leaf-shaped teeth of ''Azendohsaurus'' are clearly suited for a herbivorous lifestyle, and microwear—marks left on the tooth surface during feeding—on the teeth of ''A. madagaskarensis'' suggest they were used for browsing on vegetation that was not especially tough or woody, preferring softer (but firm) vegetation. The microwear patterns also show that it used a simple up-and-down motion of the jaw, and did not use complex jaw movement to chew its food like ornithischian dinosaurs or contemporary cynodonts. This microwear has not yet been observed on the teeth of ''A. laaroussii'', but it is unknown if this is a genuine feature relating to a difference in diet and feeding habits between the two species or if it is just a feature of preservation.

The fully developed palatal teeth suggest that it was using them for feeding in a specialised manner. However, no functional studies have been performed on the palatal teeth so it is unknown exactly what they were used for, although their similar shape to the marginal teeth suggests they were used for processing similar food. A pterygoid from a younger individual of ''A. madagaskarensis'' has fewer rows of palatal teeth that are smaller in size than those of the larger, mature individuals, indicating that ''Azendohsaurus'' increased both the number and size of its palatal teeth as it grew into adulthood. Younger individuals also had fewer dentary teeth than adults, although the difference was much less extreme compared to the palatal teeth (16 compared to the 17 of mature specimens).

genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of living and fossil organisms as well as viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus comes above species and below family. In binomial n ...

of herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

archosauromorph reptile from roughly the late Middle

Middle or The Middle may refer to:

* Centre (geometry), the point equally distant from the outer limits.

Places

* Middle (sheading), a subdivision of the Isle of Man

* Middle Bay (disambiguation)

* Middle Brook (disambiguation)

* Middle Creek (d ...

to early Late Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

Period of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria ...

and Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

. The type species

In zoological nomenclature, a type species (''species typica'') is the species name with which the name of a genus or subgenus is considered to be permanently taxonomically associated, i.e., the species that contains the biological type specimen( ...

, ''Azendohsaurus laaroussii'', was described and named by Jean-Michel Dutuit in 1972 based on partial jaw fragments and some teeth from Morocco. A second species from Madagascar, ''A. madagaskarensis'', was first described in 2010 by John J. Flynn and colleagues from a multitude of specimens representing almost the entire skeleton. The generic name "Azendoh lizard" is for the village of Azendoh, a local village near where it was first discovered in the Atlas Mountains

The Atlas Mountains are a mountain range in the Maghreb in North Africa. It separates the Sahara Desert from the Mediterranean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean; the name "Atlantic" is derived from the mountain range. It stretches around through Moroc ...

. It was a bulky quadruped that unlike other early archosauromorphs had a relatively short tail and robust limbs that were held in an odd mix of sprawled hind limbs and raised forelimbs. It had a long neck and a proportionately small head with remarkably sauropod-like jaws and teeth.

''Azendohsaurus'' used to be classified as a herbivorous dinosaur

Dinosaurs are a diverse group of reptiles of the clade Dinosauria. They first appeared during the Triassic period, between 243 and 233.23 million years ago (mya), although the exact origin and timing of the evolution of dinosaurs is t ...

, at first as an ornithischian but more often as a "prosauropod

Sauropodomorpha ( ; from Greek, meaning "lizard-footed forms") is an extinct clade of long-necked, herbivorous, saurischian dinosaurs that includes the sauropods and their ancestral relatives. Sauropods generally grew to very large sizes, had ...

" sauropodomorph. This was based only on its jaws and teeth, which share derived features typically found in herbivorous dinosaurs. The complete skeletal material from Madagascar, however, revealed more basal

Basal or basilar is a term meaning ''base'', ''bottom'', or ''minimum''.

Science

* Basal (anatomy), an anatomical term of location for features associated with the base of an organism or structure

* Basal (medicine), a minimal level that is nec ...

characteristics ancestral

An ancestor, also known as a forefather, fore-elder or a forebear, is a parent or ( recursively) the parent of an antecedent (i.e., a grandparent, great-grandparent, great-great-grandparent and so forth). ''Ancestor'' is "any person from w ...

to Archosauromorpha and that ''Azendohsaurus'' was not a dinosaur at all. Instead, ''Azendohsaurus'' was actually a more primitive archosauromorph that had convergently evolved many features of the jaws and skeleton shared with the later giant sauropod dinosaurs. It was found to be a member of a newly recognised group of specialised, mostly herbivorous archosauromorphs that was named the Allokotosauria. It is also the namesake and typifier of its own family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

of allokotosaurs, the Azendohsauridae

Azendohsauridae is a family of allokotosaurian archosauromorphs that lived during the Middle to Late Triassic period, around 242-216 million years ago. The family was originally named solely for the eponymous '' Azendohsaurus'', marking out its ...

; initially the only member, the family now includes other similar allokotosaurs, such as the larger, horned azendohsaurid '' Shringasaurus'' from India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

.

Several other groups of archosauromorphs also adapted to herbivory in the Triassic

The Triassic ( ) is a geologic period and system which spans 50.6 million years from the end of the Permian Period 251.902 million years ago (Mya), to the beginning of the Jurassic Period 201.36 Mya. The Triassic is the first and shortest period ...

, sometimes with dinosaur-like teeth that also caused confusion in their classification. ''Azendohsaurus'' is notable, however, for also convergently evolving a similar body shape to sauropodomorphs in addition to its jaws and teeth. ''Azendohsaurus'' and sauropodomorphs likely independently evolved to fill a similar ecological niche

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition.

Three variants of ecological niche are described by

It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors (fo ...

as long-necked, relatively high browsing herbivores in their environments. However, ''Azendohsaurus'' predates the large Late Triassic sauropodomorphs it resembles by several million years, and did not evolve similar body plans under the same environmental conditions. It may then have been one of the first herbivores to fill the high-browsing role that only large sauropodomorphs were thought to occupy during the Triassic, expanding the known ecological diversity of herbivorous archosauromorphs outside of dinosaurs in the Triassic Period. ''Azendohsaurus'' is also significant as it may be one of the earliest endothermic

In thermochemistry, an endothermic process () is any thermodynamic process with an increase in the enthalpy (or internal energy ) of the system.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).''Principle of Modern Chemistry'', Brooks Cole. p. ...

archosauromorphs known, and suggests that a warm-blooded metabolism was ancestral to the later archosaurs, including the dinosaurs.

Description

''Azendohsaurus'' was a stocky mid-sized reptile estimated to be roughly long. It had a small, box-shaped head with a short snout on a long neck that was raised above the shoulders. The body was broad, with a barrel-shaped chest and shoulders much taller than the hips, together with an unusually short tail. Its posture was semi-sprawled, with sprawling hind limbs and slightly elevated forelimbs. The limbs themselves are relatively short and particularly robust, with digits that are shorter and stouter compared to other early archosauromorphs, each with notably large, curved claws on all four feet. Superficially its appearance is comparable to that of sauropodomorph dinosaurs, along with various details of its skeleton, suggesting ''Azendohsaurus'' converged on similar traits for a relatively high-browsing, herbivorous lifestyle. ''A. laaroussii'' is poorly known compared to ''A. madagaskarensis'', and the two species are only known to differ in minor details of the jaw bones and teeth. Additional skeletal material of ''A. laaroussii'' has been reported from thetype locality

Type locality may refer to:

* Type locality (biology)

* Type locality (geology)

See also

* Local (disambiguation)

* Locality (disambiguation)

{{disambiguation ...

of the original skull fragments, but have yet to be formally described as of 2015.

Skull

The skull of ''A. madagaskarensis'' is almost completely known, and is robustly built with a short and boxy shape and a deep

The skull of ''A. madagaskarensis'' is almost completely known, and is robustly built with a short and boxy shape and a deep snout

A snout is the protruding portion of an animal's face, consisting of its nose, mouth, and jaw. In many animals, the structure is called a muzzle, rostrum, or proboscis. The wet furless surface around the nostrils of the nose of many mammals is ...

. The premaxillae are gently curved at the front of the upper jaw, forming a blunt, round snout tip, while the lower jaws have a deep, down-turned tip like those of sauropods. The bony nostrils are fused into a single (confluent) opening that faces forwards at the front of the snout, similar to those of rhynchosaurs.

The skull has a number of traits convergent with sauropodomorphs, including the downward curving dentary

In anatomy, the mandible, lower jaw or jawbone is the largest, strongest and lowest bone in the human facial skeleton. It forms the lower jaw and holds the lower teeth in place. The mandible sits beneath the maxilla. It is the only movable bone ...

, a robust dorsal process of the maxilla

The maxilla (plural: ''maxillae'' ) in vertebrates is the upper fixed (not fixed in Neopterygii) bone of the jaw formed from the fusion of two maxillary bones. In humans, the upper jaw includes the hard palate in the front of the mouth. The ...

, and several features of the teeth. The process on the maxilla usually indicates the presence of an antorbital fenestra in archosauriforms, but in ''Azendohsaurus'' this space is occupied by the lacrimal bone

The lacrimal bone is a small and fragile bone of the facial skeleton; it is roughly the size of the little fingernail. It is situated at the front part of the medial wall of the orbit. It has two surfaces and four borders. Several bony landmarks of ...

in front of the eyes. This is a unique arrangement unknown in other Triassic archosauromorphs, except for the related ''Shringasaurus''. The orbits

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such as a ...

are almost entirely occupied by the large sclerotic rings, suggesting large eyes. The lower temporal fenestra is open at the bottom, separating the jugal and the quadratojugal bones (a primitive trait for archosauromorphs). Also like other early archosauromorphs, ''Azendohsaurus'' has a small (3–5 mm across) parietal foramen ("third eye") on the roof of the skull.

heterodont

In anatomy, a heterodont (from Greek, meaning 'different teeth') is an animal which possesses more than a single tooth morphology.

In vertebrates, heterodont pertains to animals where teeth are differentiated into different forms. For example, ...

, and can be readily distinguished from each other. The upper teeth are relatively short and broad at their base, with 4–6 denticles on each surface, similar to ornithischians; the lower teeth are almost twice as tall and have twice as many denticles, more closely resembling the teeth of sauropodomorphs. The four premaxillary teeth are the longest teeth in the upper jaw, and are more recurved back in shape than the rest.

The

The palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly s ...

is unusually covered in numerous fully developed palatal teeth, with up to four sets on the pterygoid and additional rows on the palatine

A palatine or palatinus (in Latin; plural ''palatini''; cf. derivative spellings below) is a high-level official attached to imperial or royal courts in Europe since Roman times.

and vomer

The vomer (; lat, vomer, lit=ploughshare) is one of the unpaired facial bones of the skull. It is located in the midsagittal line, and articulates with the sphenoid, the ethmoid, the left and right palatine bones, and the left and right maxil ...

s. Mature ''Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis'' have at least 44 pairs of palatal teeth, in addition to the 4 teeth in each premaxilla and 11–13 in the maxilla each, along with a maximum of 17 teeth in the dentary. Palatal teeth are not uncommon in herbivorous reptiles, but in ''Azendohsaurus'' they are almost identical in shape to those along the jaw margins, but a bit stouter. Other archosauromorphs with palatal teeth have a much simpler palatal dentition of small, domed teeth. ''Teraterpeton

''Teraterpeton'' (meaning "wonderful creeping thing" in Greek) is an extinct genus of trilophosaurid archosauromorphs. It is known from a partial skeleton from the Late Triassic Wolfville Formation of Nova Scotia, described in 2003. It has man ...

'' is the only other archosauromorph with similarly well developed palatal teeth.

The only described material of ''A. laaroussii'' are dentaries, maxillae, a premaxilla and several teeth. They broadly resemble ''A. madagaskarensis'' in general form but with a few distinguishing differences. The tooth count of ''A. laaroussii'' is higher, with 15–16 teeth in the maxilla compared to the 11–13 of ''A. madagaskarensis''. The teeth of ''A. laaroussii'' are also taller than those of ''A. madagaskarensis'' and have more closely packed denticles. Further distinguishing the two species is the presence of a prominent keel on the inside surface of the maxilla. This keel runs the whole length of the maxilla in ''A. laaroussii'', but is only found along the back half of it in ''A. madagaskarensis''. Any other possible differences between the two species cannot be determined without rest of the skull and skeleton.

Skeleton

All the known post-cranial information for the skeleton of ''Azendohsaurus'' comes from ''A. madagaskarensis''. Much of thevertebral column

The vertebral column, also known as the backbone or spine, is part of the axial skeleton. The vertebral column is the defining characteristic of a vertebrate in which the notochord (a flexible rod of uniform composition) found in all chordate ...

is known in ''Azendohsaurus'', and although incomplete, it is estimated to have 24 presacral vertebrae (including the atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geograp ...

and axis). The sacrum of the hips has only two vertebrae, and the full number of caudal vertebrae in the tail is unknown, but it is estimated to be only around 45–55 (low for an archosaur).

The cervical vertebrae

In tetrapods, cervical vertebrae (singular: vertebra) are the vertebrae of the neck, immediately below the skull. Truncal vertebrae (divided into thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in mammals) lie caudal (toward the tail) of cervical vertebrae. In ...

change shape down the neck, beginning as characteristically elongated with long and low neural spines

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates,Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characteristic i ...

, and getting progressively shorter in length towards the base of the neck, but with increasingly taller and narrower neural spines. This shortening is seen in the necks of other allokotosaurs like '' Trilophosaurus'', but is not found in other long-necked archosauromorphs (e.g. the middle cervicals are the longest in tanystropheids

Tanystropheidae is an extinct family of mostly marine archosauromorph reptiles that lived throughout the Triassic Period. They are characterized by their long, stiff necks formed from elongated cervical vertebrae with very long cervical ribs. So ...

). The neck would have been held raised up above the body, indicated by the inclined angle of the zygapophyses that connect each vertebra

The spinal column, a defining synapomorphy shared by nearly all vertebrates, Hagfish are believed to have secondarily lost their spinal column is a moderately flexible series of vertebrae (singular vertebra), each constituting a characterist ...

, as well as the front zygapophyses of each vertebra being higher than those at the back. The neck was also likely held in a gentle arc, based on an articulated set of cervicals in this position.

The dorsal vertebrae of the back generally resemble the last cervicals, with tall, vertical neural spines. These vertebrae also decrease in length down the back, but less dramatically than in the neck. The last dorsal is unique, however, as it has a neural spine angled forward. Of the two sacrals, the first vertebra is larger and more robust, with a tall neural spines over its rear half. Both sacrals have large ribs completely fused to the vertebrae that articulate with the ilia (see below).

The caudal vertebrae resemble the other vertebrae, but with backward inclined neural spines. The length of the caudals and the height of the neural spines gradually decreases down the tail, unlike some other archosauromorphs where the vertebrae elongate towards the tip. This implies that the tail was short and not tapering, but the very tip of the tail is unknown. They consistently have chevron facets from the 3rd or 4th vertebrae down to the last known caudals in the series.

The cervical ribs are long and thin, becoming more robust and tapered as they move down the neck. Some of the cervical ribs from bottom half of the neck have a slight facet on the inside surface at their tips that may have held the tip of the preceding rib, forming a rigid cervical rib series (also suggested for the long necked ''

The dorsal vertebrae of the back generally resemble the last cervicals, with tall, vertical neural spines. These vertebrae also decrease in length down the back, but less dramatically than in the neck. The last dorsal is unique, however, as it has a neural spine angled forward. Of the two sacrals, the first vertebra is larger and more robust, with a tall neural spines over its rear half. Both sacrals have large ribs completely fused to the vertebrae that articulate with the ilia (see below).

The caudal vertebrae resemble the other vertebrae, but with backward inclined neural spines. The length of the caudals and the height of the neural spines gradually decreases down the tail, unlike some other archosauromorphs where the vertebrae elongate towards the tip. This implies that the tail was short and not tapering, but the very tip of the tail is unknown. They consistently have chevron facets from the 3rd or 4th vertebrae down to the last known caudals in the series.

The cervical ribs are long and thin, becoming more robust and tapered as they move down the neck. Some of the cervical ribs from bottom half of the neck have a slight facet on the inside surface at their tips that may have held the tip of the preceding rib, forming a rigid cervical rib series (also suggested for the long necked ''Tanystropheus

''Tanystropheus'' (Greek ~ 'long' + 'hinged') is an extinct archosauromorph reptile from the Middle and Late Triassic epochs. It is recognisable by its extremely elongated neck, which measured long—longer than its body and tail combined. T ...

'') that would stiffen the neck. The trunk

Trunk may refer to:

Biology

* Trunk (anatomy), synonym for torso

* Trunk (botany), a tree's central superstructure

* Trunk of corpus callosum, in neuroanatomy

* Elephant trunk, the proboscis of an elephant

Computing

* Trunk (software), in rev ...

ribs are long and curve outwards, indicating ''Azendohsaurus'' had a broad and deep barrel-shaped chest. The length and curvature of the ribs decreases down the spine, and the last rib is short, fused completely to the final dorsal vertebra, and points directly outwards to the sides. Only a single set of gastralia is known for ''Azendohsaurus'', and their very delicate build and rarity compared to other bones suggests that it did not have a well developed basket of gastralia under the belly like some other archosauromorphs (e.g. '' Proterosuchus'').

Limbs and girdles

The forelimbs and shoulders (pectoral girdle) of ''Azendohsaurus'' are well developed and robust. The

The forelimbs and shoulders (pectoral girdle) of ''Azendohsaurus'' are well developed and robust. The scapula

The scapula (plural scapulae or scapulas), also known as the shoulder blade, is the bone that connects the humerus (upper arm bone) with the clavicle (collar bone). Like their connected bones, the scapulae are paired, with each scapula on eithe ...

(shoulder blade) is long, about twice as tall as it is wide, matching the length and curvature of the ribs to accommodate the deep chest. The blade is concave on each side with a slightly expanded tip that is pointed at the back. The interclavicle is large and robust, and shares with ''Trilophosaurus'' and some rhynchosaurs a long "paddle-like" posterior process that is flattened and expanded towards the tip. It also has a unique forward-pointing process, a feature it shares only with '' Protorosaurus'' and some early diapsids (most other archosauromorphs have a notch instead).

The coracoids are large and rounded, articulating with the scapula to form the glenoid (shoulder socket). The glenoid faces laterally, typical of sprawling reptiles, however, the scapular portion is directed slightly backwards, which could indicate the humerus

The humerus (; ) is a long bone in the arm that runs from the shoulder to the elbow. It connects the scapula and the two bones of the lower arm, the radius and ulna, and consists of three sections. The humeral upper extremity consists of a roun ...

was held in a more raised posture. The humerus itself is large and broadly expanded at both ends, leaving a relatively narrow "waisted" mid-shaft, with a very well developed deltopectoral crest. The radius

In classical geometry, a radius ( : radii) of a circle or sphere is any of the line segments from its center to its perimeter, and in more modern usage, it is also their length. The name comes from the latin ''radius'', meaning ray but also the ...

is similarly stocky with slightly expanded ends, while the ulna

The ulna (''pl''. ulnae or ulnas) is a long bone found in the forearm that stretches from the elbow to the smallest finger, and when in anatomical position, is found on the medial side of the forearm. That is, the ulna is on the same side of t ...

is greatly expanded at both ends, though to a lesser extent distally

Standard anatomical terms of location are used to unambiguously describe the anatomy of animals, including humans. The terms, typically derived from Latin or Greek roots, describe something in its standard anatomical position. This position ...

.

The hips (pelvic girdle) are not as deep as the shoulders, with the three hip bones being roughly equal in size. The ilium

Ilium or Ileum may refer to:

Places and jurisdictions

* Ilion (Asia Minor), former name of Troy

* Ilium (Epirus), an ancient city in Epirus, Greece

* Ilium, ancient name of Cestria (Epirus), an ancient city in Epirus, Greece

* Ilium Building, a ...

is tall and curved along the top surface, with a short rounded process at the front and a longer tapering process behind it. The pubis points down and slightly forwards, and only has a slightly thickened expansion (boot) at the tip. The ischium is relatively short, shorter than the ilium, and roughly triangular in shape with straight edges and a rounded rear tip. The articulation surfaces between each ischia are unusually expanded compared to other archosauromorphs. All three contribute to forming a deep, rounded acetabulum (hip socket). Unlike the open socket of dinosaurs, the internal wall of the acetabulum in ''Azendohsaurus'' is solid bone.

The large sacral ribs articulate with the ilium so that it is held almost vertically, although their slight downward angle would have deflected the hip socket to face not only out away from the body but also down by about 10° to 25° from vertical. The femur

The femur (; ), or thigh bone, is the proximal bone of the hindlimb in tetrapod vertebrates. The head of the femur articulates with the acetabulum in the pelvic bone forming the hip joint, while the distal part of the femur articulates wit ...

is long and vaguely S-shaped, with a slightly expanded head that is not turned inwards, unlike those of dinosaurs, indicating it was not held upright. The femur is also twisted along its shaft so that the faces of the head and the knee are offset from each other by about ~75°. The tibia is roughly 75% the length of the femur, slightly bowed out, and is very robust compared those of other archosauromorphs except for the largest rhynchosaurs. The fibula

The fibula or calf bone is a human leg, leg bone on the Lateral (anatomy), lateral side of the tibia, to which it is connected above and below. It is the smaller of the two bones and, in proportion to its length, the most slender of all the long ...

by contrast is slender and more prominently twisted along its length.

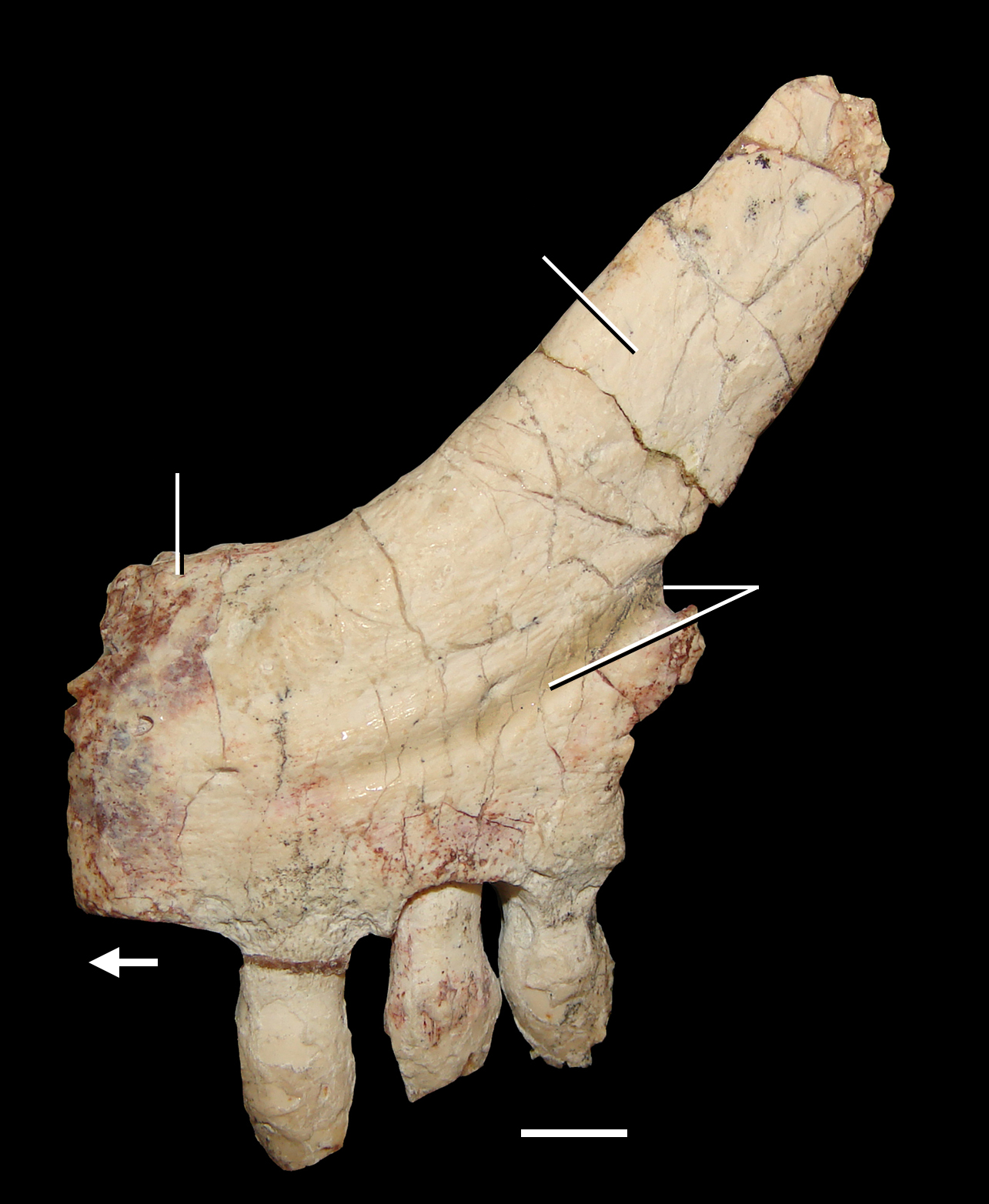

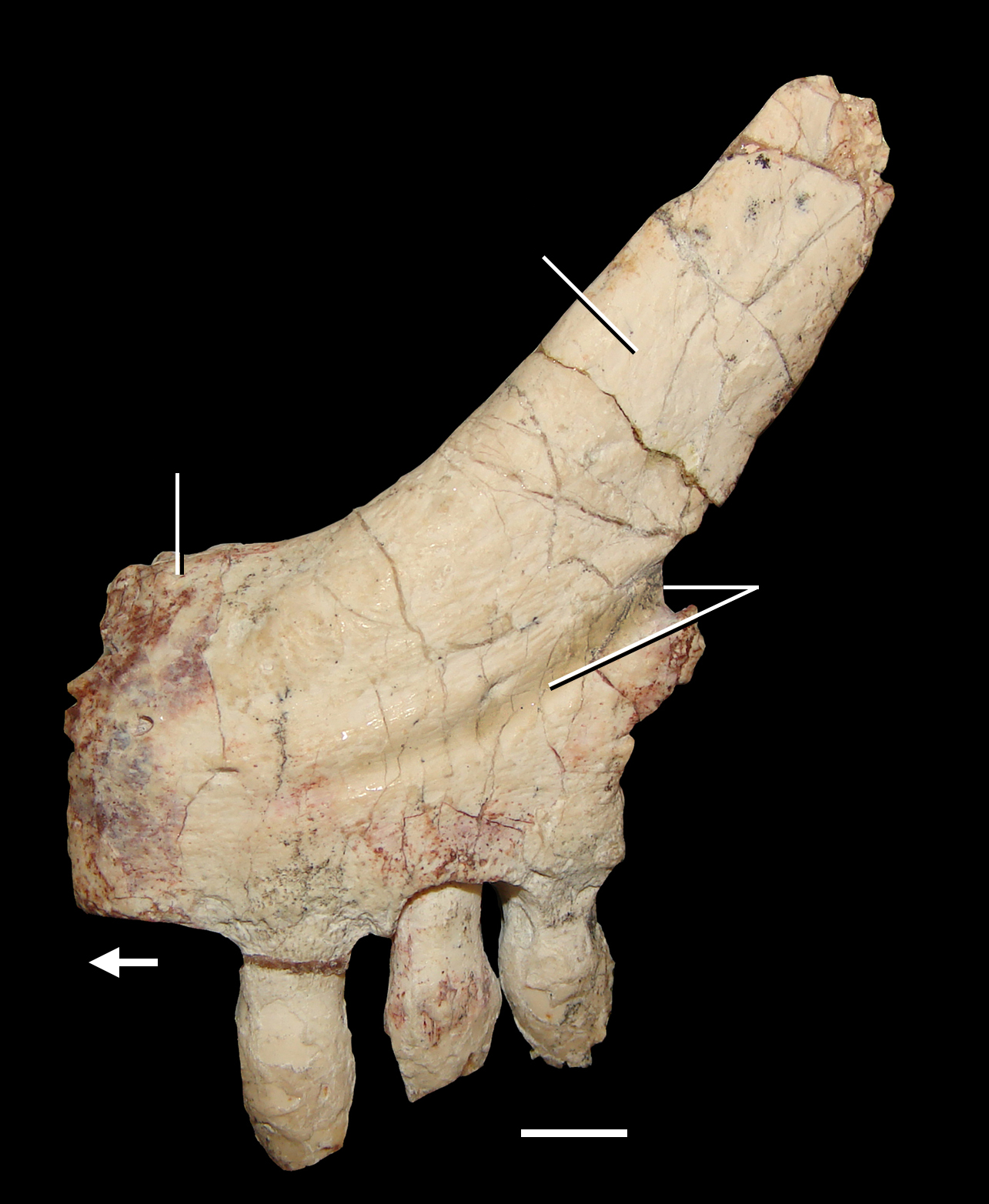

The extremities of ''Azendohsaurus'' are well represented in the fossils, including both a complete hand (manus) and foot (pes) each in articulation. All of the carpals and tarsal bones

In the human body, the tarsus is a cluster of seven articulating bones in each foot situated between the lower end of the tibia and the fibula of the lower leg and the metatarsus. It is made up of the midfoot (cuboid, medial, intermediate, an ...

are well ossified and distinct, and the complicated tarsus is made up of nine bones. The metacarpals in the hand are notable as they diverge in a smooth arc, with the length of the digits almost symmetrical around the long third digit as well as relatively non-diverged first and fifth digits. This contrasts with the hands of other reptiles where first and fifth digits are spread out from each other and the fourth digit is the longest. The metatarsals and digits of the foot also diverge in a smooth arc, but unlike the hand they are not symmetrical, with a long fourth toe and a short, hooked fifth digit.

All the digits of the hands and feet are unusually short for an archosauromorph, contrasting with the related ''Trilophosaurus''. The claw

A claw is a curved, pointed appendage found at the end of a toe or finger in most amniotes (mammals, reptiles, birds). Some invertebrates such as beetles and spiders have somewhat similar fine, hooked structures at the end of the leg or tars ...

s (or unguals) are all very large, narrow and sharply recurved, and are significantly larger than the preceding finger bone

The phalanges (singular: ''phalanx'' ) are digital bones in the hands and feet of most vertebrates. In primates, the thumbs and big toes have two phalanges while the other digits have three phalanges. The phalanges are classed as long bones.

...

they were attached to. The digits and claws share features with those of dromaeosaurid and troodontid

Troodontidae is a clade of bird-like theropod dinosaurs. During most of the 20th century, troodontid fossils were few and incomplete and they have therefore been allied, at various times, with many dinosaurian lineages. More recent fossil disco ...

maniraptorans

Maniraptora is a clade of coelurosaurian dinosaurs which includes the birds and the non-avian dinosaurs that were more closely related to them than to ''Ornithomimus velox''. It contains the major subgroups Avialae, Deinonychosauria, Oviraptorosa ...

, as well as other reptiles such as the turtle

Turtles are an order of reptiles known as Testudines, characterized by a special shell developed mainly from their ribs. Modern turtles are divided into two major groups, the Pleurodira (side necked turtles) and Cryptodira (hidden necked ...

'' Proganochelys''. These shared traits are associated with well developed flexor tendons, and it is suggested to be an adaptation for withstanding forces involved in digging.

History of Discovery

''A. laaroussii''

Early discoveries

The first fossils of ''Azendohsaurus laaroussii'' were discovered in a northern part the Timezgadiouine Formation inMorocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks the Mediterranean Sea to the north and the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and has land borders with Algeria ...

, which is found within the Argana Basin

Argana is a small town and rural commune in Taroudant Province of the Souss-Massa-Drâa region of Morocco

Morocco (),, ) officially the Kingdom of Morocco, is the westernmost country in the Maghreb region of North Africa. It overlooks ...

of the High Atlas

High Atlas, also called the Grand Atlas ( ar, الأطلس الكبير, Al-Aṭlas al-Kabīr; french: Haut Atlas; shi, ⴰⴷⵔⴰⵔ ⵏ ⴷⵔⵏ ''Adrar n Dern''), is a mountain range in central Morocco, North Africa, the highest part of t ...

. The fossil beds consist of sandstone

Sandstone is a clastic sedimentary rock composed mainly of sand-sized (0.0625 to 2 mm) silicate grains. Sandstones comprise about 20–25% of all sedimentary rocks.

Most sandstone is composed of quartz or feldspar (both silicates ...

s and red clay mudstones, and were excavated by Jean-Michel Dutuit between 1962 and 1969. The fossils of ''A. laaroussii'' are known from only a single layer within the formation, in an outcrop

An outcrop or rocky outcrop is a visible exposure of bedrock or ancient superficial deposits on the surface of the Earth.

Features

Outcrops do not cover the majority of the Earth's land surface because in most places the bedrock or superficia ...

numbered XVI by Dutuit at the base of the T5 (or Irohalene) member. The T5 member has traditionally been roughly dated to the early Late Triassic in age using vertebrate biostratigraphy

Biostratigraphy is the branch of stratigraphy which focuses on correlating and assigning relative ages of rock strata by using the fossil assemblages contained within them.Hine, Robert. “Biostratigraphy.” ''Oxford Reference: Dictionary of Bio ...

based on the presence of the phytosaur ''"Paleorhinus" magnoculus'', as part of the Carnian dated '"''Palaeorhinus''" biochron', although this method of correlating and dating global Triassic sequences may be inaccurate and the date for the T5 member remains uncertain.

The first fossils consisted of only a partial tooth-bearing dentary fragment and some associated teeth. This material was discovered by J. M. Dutuit in 1965 and described in 1972, who believed it to belong to a herbivorous ornithischian dinosaur, as well as one of the oldest dinosaurs yet discovered. He named the genus "Azendoh lizard", after the nearby Azendoh village located only 1.5 km to the west of where the fossils were discovered. The specific name, ''A. laaroussii'', is in honour of Laaroussi, the name of a technician from the Moroccan geological mapping service who first discovered the site where ''Azendohsaurus'' was found.

Dutuit's description of ''Azendohsaurus'' as an ornithischian was soon challenged by palaeontologist Richard Thulborn Richard Anthony (Tony) Thulborn is a British paleontologist. He is recognized as an expert in dinosaur tracks, and as one of the most productive paleontologists of his time.

In 1982, Thulborn debunked the purported plesiosaur embryos discovered by ...

two years later in 1974, who was the first to suggest that ''Azendohsaurus'' was a "prosauropod" instead. The same conclusion was made by José Boneparte after examining the material himself in 1976. This re-identification was favoured by researchers in subsequent publications, and it was variously referred to the "prosauropod" families Anchisauridae and Thecodontosauridae without further explanation. Dutuit himself even agreed that ''Azendohsaurus'' was likely to be a "prosauropod" in 1983, although not long before in 1981 he had briefly regarded it as a "pre-ornithischian".

In 1985, palaeontologist Peter Galton suggested that Dutuit's original "Azandohsaurus " material included the jaw of a "prosauropod" and the tooth of a fabrosaurid

Ornithischia () is an extinct order of mainly herbivorous dinosaurs characterized by a pelvic structure superficially similar to that of birds. The name ''Ornithischia'', or "bird-hipped", reflects this similarity and is derived from the Greek ...

ornithischian (a now defunct grouping of early ornithischians), based on the differences in the shape of the teeth. This suggestion was refuted by François-Xavier Gauffre in 1993 when he re-described the material, as well describing additional jaw bones and teeth including two maxillae. He correctly concluded that the material belonged to a single taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

, but assigned the genus to "Prosauropoda" ''incertae sedis

' () or ''problematica'' is a term used for a taxonomic group where its broader relationships are unknown or undefined. Alternatively, such groups are frequently referred to as "enigmatic taxa". In the system of open nomenclature, uncertain ...

'' based again on the characteristics of the jaws and teeth. However, he could not determine its position within "Prosauropoda" due to the ambiguous distribution of these traits in early herbivorous dinosaurs, as well as a lack of any comparable Triassic reptiles, so he referred it to ''incertae sedis''. His assessment was accepted by many other researchers in the years following up until the description of the new material from the Madagascan species.

Later finds to present

New material from thetype locality

Type locality may refer to:

* Type locality (biology)

* Type locality (geology)

See also

* Local (disambiguation)

* Locality (disambiguation)

{{disambiguation ...

of ''A. laaroussii'', including parts of the post-cranial skeleton, was reported on in 2002 at the annual conference of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology by Nour-Eddine Jalil and Fabien Knoll. The additional material included presacral vertebrae, limb bones and limb girdles. The material was disarticulated, and was only attributable to ''A. laaroussii'' due to its association with recognised fragments of the skull and jaws. The post-cranial material was recognised as non-dinosaurian, but still believed to be an ornithodiran

Avemetatarsalia (meaning "bird metatarsals") is a clade of diapsid Reptile, reptiles containing all archosaurs more closely related to birds than to crocodilians. The two most successful groups of avemetatarsalians were the dinosaurs and pterosau ...

archosaur

Archosauria () is a clade of diapsids, with birds and crocodilians as the only living representatives. Archosaurs are broadly classified as reptiles, in the cladistic sense of the term which includes birds. Extinct archosaurs include non-avi ...

related to dinosaurs. If correctly associated with the jaws and teeth, this indicated ''Azendohsaurus'' was not closely related to any herbivorous dinosaurs, despite their similarities. Similarly, teeth from other purported Triassic ornithischians were later found to belong to previously unrecognised herbivorous reptiles, such as the pseudosuchian '' Revueltosaurus'', highlighting the possibility for mistaken identities in other purported herbivorous Triassic dinosaurs, including ''Azendohsaurus''.

The new post cranial material from ''A. laaroussii'' was described as part of a Ph.D thesis

A thesis ( : theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144 ...

by Khaldoune in 2014, but as of 2019 this thesis has not yet been published and the material remains officially undescribed in published literature. However, it has now more confidently been referred to ''A. laaroussii'' after the description of the Madagascan material, and was found to share at least two diagnostic post cranial traits with the Madagascan species. All the material from ''A. laaroussii'', including the holotype and unpublished post crania, is housed at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle

The French National Museum of Natural History, known in French as the ' (abbreviation MNHN), is the national natural history museum of France and a ' of higher education part of Sorbonne Universities. The main museum, with four galleries, is loca ...

in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

.

''A. madagaskarensis''

Initial discoveries

In 1997 through to 1999, fossils of a new archosauromorph were discovered by an international expedition in southwesternMadagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

and were recovered over the following decade. The fossils were found in a single bone bed, referred to as M-28, that was only tens of centimetres thick across a 100 metre stretch of outcrop exposed as an uplifted river terrace not far from the east bank of the Malio River, just outside of the Isalo National Park, north-west of the town of Ranohira and to the east of Sakahara. The locality was from the base of the Middle–Late Triassic Makay Formation, also referred to as Isalo II, a part of the Isalo "Group" in the Morondava Basin.

Previously, the formation had been believed to be Early to Middle Jurassic in age, although the earlier discovery of the rhynchosaur '' Isalorhynchus'' had revised that estimate to the Middle Triassic. The tetrapod fossils recovered in the 1997–99 expedition confirmed the Isalo II was Triassic in age, but instead suggested a younger Carnian age. The age of the formation has also been correlated to the ''Santacruzodon'' Assemblage Zone (AZ) from the Santa Maria Formation

The Santa Maria Formation is a sedimentary rock formation found in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. It is primarily Carnian in age ( Late Triassic), and is notable for its fossils of cynodonts, " rauisuchian" pseudosuchians, and early dinosaurs an ...

in South America based on the shared genera of traversodontid cynodonts

The cynodonts () (clade Cynodontia) are a clade of eutheriodont therapsids that first appeared in the Late Permian (approximately 260 mya), and extensively diversified after the Permian–Triassic extinction event. Cynodonts had a wide variety ...

, with a similar late Ladinian or early Carnian age. The ''Santacruzodon'' AZ has been more reliably dated through radioisotope

A radionuclide (radioactive nuclide, radioisotope or radioactive isotope) is a nuclide that has excess nuclear energy, making it unstable. This excess energy can be used in one of three ways: emitted from the nucleus as gamma radiation; transferr ...

U—Pb dating, suggesting a maximum depositional age of 237 ±1.5 million years in the early Carnian.

The bone bed contained material from almost "a dozen" individuals of varying ages and size, all from a single species. The material was very well preserved, generally preserving the three-dimensional shape of the bones with very little crushing or distortion in some of the specimens. Based on the state of preservation, some of the bones were believed to have been buried rapidly while others were exposed for longer on the surface, where they were weathered, cracked and possibly trampled on before burial.

As with ''A. laaroussii'', the teeth and jaws were the first material to be recovered and described from the bone bed. These were initially mistaken to belong two different species based on the difference in tooth shape in the upper and lower jaws, but one of them was recognised as closely resembling ''A. laaroussii'', sharing a keel on the inside surface of the maxilla and expanded, leaf-shaped teeth, among other features''.'' Like ''A. laaroussii'', both of these supposed species were also misidentified as "prosauropods"; a species of ''Azendohsaurus'' or a related taxon and another, more typical "prosauropod". Further discoveries of associated material clarified that all the jaw material and the rest of the skeletons were from a single, new species of ''Azendohsaurus''.

Reinterpretation

Even preliminary examination of the rest of the skull and skeleton from the Madagascan species confirmed that ''Azendohsaurus'' was not a dinosaur, and was instead an aberrant herbivorous archosauromorph that was only distantly related to dinosaurs, let alone sauropodomorphs. A description of the cranial material was published first in May, 2010 by John J. Flynn and colleagues, who also officially named and diagnosed it as a new species of ''Azendohsaurus'', ''Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis'', named for its country of origin. This was also the first time ''Azendohsaurus'' was determined to be a non-dinosaur in the published literature.

In December, 2015, the rest of the skeleton of ''A. madagaskarensis'' was formally described and published by

Even preliminary examination of the rest of the skull and skeleton from the Madagascan species confirmed that ''Azendohsaurus'' was not a dinosaur, and was instead an aberrant herbivorous archosauromorph that was only distantly related to dinosaurs, let alone sauropodomorphs. A description of the cranial material was published first in May, 2010 by John J. Flynn and colleagues, who also officially named and diagnosed it as a new species of ''Azendohsaurus'', ''Azendohsaurus madagaskarensis'', named for its country of origin. This was also the first time ''Azendohsaurus'' was determined to be a non-dinosaur in the published literature.

In December, 2015, the rest of the skeleton of ''A. madagaskarensis'' was formally described and published by Sterling J. Nesbitt

Sterling Nesbitt (born March 25, 1982, in Mesa, Arizona) is an American paleontologist best known for his work on the origin and early evolutionary patterns of archosaurs. He is currently an associate professor at Virginia Tech in the Department ...

and colleagues, providing the first detailed examination of the full anatomy of ''Azendohsaurus'' from the now almost completely known skeleton. In addition to comparing its anatomy, they were also able to analyse its evolutionary relationships to other Triassic reptiles in a phylogenetic

In biology, phylogenetics (; from Greek φυλή/ φῦλον [] "tribe, clan, race", and wikt:γενετικός, γενετικός [] "origin, source, birth") is the study of the evolutionary history and relationships among or within groups o ...

context for the first time.

The preservation of the material was described as "generally excellent" by Nesbitt and colleagues, and the amount of overlapping material made it easier to determine the original morphology from distorted and broken bones. Much of the material was found disarticulated and sometimes isolated, but a number of specific parts of the body were found articulated in life position, including sections of the neck, back, hands and feet. Most of the material was similarly sized, with a range of about 25% between the smallest and largest specimens, although the significance of this is not understood and it could be related to ontogeny

Ontogeny (also ontogenesis) is the origination and development of an organism (both physical and psychological, e.g., moral development), usually from the time of fertilization of the egg to adult. The term can also be used to refer to the stu ...

, individual variation or sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most an ...

.

The well preserved nature of much of the material also allowed for reinterpretations of parts of the skeleton of other archosauromorphs, such as the hand of ''Trilophosaurus''. The hands of other archosauromorphs are often poorly known, and so their preservation in ''Azendohsaurus'' is considered important for understanding their evolution in early archosauromorphs. All the specimens of ''A. madagaskarensis'' are permanently housed in both the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar (including the holotype) and at the Field Museum of Natural History

The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), also known as The Field Museum, is a natural history museum in Chicago, Illinois, and is one of the largest such museums in the world. The museum is popular for the size and quality of its educational ...

in Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = List of sovereign states, Count ...

, Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolitan areas include, Peoria and Roc ...

, including casts of some of the original specimens.

Classification

Initial attempts

''Azendohsaurus'' was first misidentified as an ornithischian dinosaur by Dutuit, based on shared characteristics of its teeth such as the leaf-like shape and the number of denticles. It was later believed to be a sauropodomorph instead by other researchers, assigned to the defunct infraorder "Prosauropoda" (then believed to be a distinct

''Azendohsaurus'' was first misidentified as an ornithischian dinosaur by Dutuit, based on shared characteristics of its teeth such as the leaf-like shape and the number of denticles. It was later believed to be a sauropodomorph instead by other researchers, assigned to the defunct infraorder "Prosauropoda" (then believed to be a distinct monophyletic

In cladistics for a group of organisms, monophyly is the condition of being a clade—that is, a group of taxa composed only of a common ancestor (or more precisely an ancestral population) and all of its lineal descendants. Monophyletic ...

group related to sauropods, now known to be a paraphyletic

In taxonomy (general), taxonomy, a group is paraphyletic if it consists of the group's most recent common ancestor, last common ancestor and most of its descendants, excluding a few Monophyly, monophyletic subgroups. The group is said to be pa ...

grade) based on the morphology of its lower jaw, maxilla and teeth, such as the downward curving dentary and absence of a predentary bone, one of the characteristic traits of ornithischians. These misidentifications were caused by the convergence in jaw and tooth shape between it and the herbivorous dinosaurs while its true phylogenetic relationships could not be realised due to the absence of other bones of the skull and skeleton.

The non-dinosaurian identity of ''Azendohsaurus'' was first hinted at after the discovery of additional skeletal material recovered from the type locality. This was based on the presence of traits such as a solid hip socket (acetabulum), and a proximal fourth trochanter on the femur that also lacked an inward-facing head, which are typical of dinosaur skeletons. While evidently not a dinosaur, it was tentatively interpreted as an ornithodiran archosaur, still closely related to dinosaurs.

The discovery of more complete material from Madagascar prompted the first formal classification ''Azendohsaurus'' as non-dinosaurian by Flynn and colleagues in 2010 through a detailed description of its cranial anatomy and were able to clarify its relationships further. They instead recognised it to be a more basal archosauromorph, far removed dinosaurs and closely related to but outside of the clade of Archosauriformes. As well as the derived, sauropodomorph-like features, the skull also had numerous primitive traits for archosauromorphs, including an open-bottomed lower temporal fenestra, extensive palatal teeth, a pineal foramen and no external mandibular or antorbital fenestrae. However, its exact relationships still remained unknown beyond a position as an indeterminate non-archosauriform archosauromorph.

Recognition of Allokotosauria

''Azendohsaurus'' was included in a phylogenetic analysis of Triassic archosauromorphs for the first time in 2015 by Nesbitt and colleagues, utilising all of the new information from the skull and skeleton and a broad sample of various Triassic archosauromorph species, where it was recovered as closely related to other enigmatic herbivorous Triassic reptiles such as '' Trilophosaurus'' and ''Teraterpeton

''Teraterpeton'' (meaning "wonderful creeping thing" in Greek) is an extinct genus of trilophosaurid archosauromorphs. It is known from a partial skeleton from the Late Triassic Wolfville Formation of Nova Scotia, described in 2003. It has man ...

''. This newly recognised grouping of archosauromorphs was named Allokotosauria, meaning "strange reptiles", for the unusual qualities of the reptiles that belonged to the group. ''Azendohsaurus'' was found to be the sister taxon

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and ...

of the family

Family (from la, familia) is a group of people related either by consanguinity (by recognized birth) or affinity (by marriage or other relationship). The purpose of the family is to maintain the well-being of its members and of society. Idea ...

Trilophosauridae, and was recognised as the sole member of its own family, the Azendohsauridae

Azendohsauridae is a family of allokotosaurian archosauromorphs that lived during the Middle to Late Triassic period, around 242-216 million years ago. The family was originally named solely for the eponymous '' Azendohsaurus'', marking out its ...

, due its distinctiveness even amongst other allokotosaurs. A similar result was recovered by another large analysis of archosauromorph phylogeny in 2016 by Martín D. Ezcurra, who found a monophyletic Allokotosauria containing ''Azendohsaurus'' and ''Trilophosaurus''.

Allokotosaurs are recognised as often having specialised jaws and teeth, as well as sharing a number of synapomorphies

In phylogenetics, an apomorphy (or derived trait) is a novel character or character state that has evolved from its ancestral form (or plesiomorphy). A synapomorphy is an apomorphy shared by two or more taxa and is therefore hypothesized to hav ...

that include several reversals to more plesiomorphic (ancestral) traits of archosauromorphs, as well as at least two derived traits. The clade is considered to be well supported in these analyses. However, although closely related, the craniodental characteristics of allokotosaurs vary dramatically, and among them ''Azendohsaurus'' was characterised by having laterally compressed, serrated teeth present throughout the length of the jaws (unlike the 'beaked' jaws of trilophosaurids). ''Azendohsaurus'' broadly shares with other azendohsaurids features such as confluent nares, leaf-shaped teeth and a long neck, but ''Azendohsaurus'' itself is distinguished by the distinctive groove on the inside surface of the maxilla and tooth crowns that are expanded above the base.

In 2017, another large allokotosaur was described from the Middle Triassic of

In 2017, another large allokotosaur was described from the Middle Triassic of India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

by Saradee Sengupta and colleagues, named ''Shringasaurus indicus

''Shringasaurus'' (meaning "horned lizard", from Sanskrit शृङ्ग (''śṛṅga),'' "horn", and Ancient Greek (''sauros),'' "lizard") is an extinct genus of archosauromorph reptile from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of India. It is known ...

.'' ''Shringasaurus'' was very similar to ''Azendohsaurus'', and they were found to be closely related, supporting the existence of Azendohsauridae as a distinct family from the trilophosaurids. The same analysis also recovered '' Pamelaria'', another long necked archosauromorph from India, as a basal azendohsaurid. Similarities between ''Pamelaria'' and ''Azendohsaurus'' had been noted by Nesbitt and colleagues in 2015, including confluent nares, serrated teeth and low cervical spines, but their analysis favoured a position in Allokotosauria basal to azendohsaurids. The 2017 analysis also confirmed the close relationship between ''A. laaroussii'' and ''A. madagaskarensis'' within Azendohsauridae, strengthening their shared referral to the genus ''Azendohsaurus''. A 2018 analysis of Triassic archosauromorphs failed to recover Allokotosauria, but still recovered both species of ''Azendohsaurus'' within a clade of azendohsaurids. The cladogram below follows the results of Sengupta and colleagues in 2017:

A 2022 phylogenetic analysis supported a monophyletic Allokotosauria and confirmed that ''Azendohsaurus'' was a sister taxon of ''Shringasaurus'', and that the clade consisting of the two genera was in turn most closely related to ''Malerisaurus'' and ''Pamelaria''.

Evolutionary significance

The number of convergent traits shared between ''Azendohsaurus'' and sauropodomorph dinosaurs is remarkably high, especially as all the shared features are interpreted as beinghomoplastic

Homoplasy, in biology and phylogenetics, is the term used to describe a Phenotypic trait, feature that has been gained or lost independently in separate lineages over the course of evolution. This is different from Homology (biology), homology, w ...

, meaning that they evolved completely independently of each other. Some of the shared adaptations of the skeleton between ''Azendohsaurus'' and sauropodomorphs were previously considered to be unique to sauropodomorphs. However, the convergent evolution

Convergent evolution is the independent evolution of similar features in species of different periods or epochs in time. Convergent evolution creates analogous structures that have similar form or function but were not present in the last com ...

of these traits in ''Azendohsaurus'' as adaptations towards a herbivorous lifestyle show that they may be more broadly distributed amongst Triassic archosauromorphs, and do not necessarily indicate a close relationship to sauropodomorphs in fossil taxa.

The pattern of convergences in ''Azendohsaurus'' is unusual, as they appear to be have arisen in only the front half of the animal, while the sprawling back legs and short tail of ''Azendohsaurus'' are characteristically primitive of earlier archosauromorphs, very unlike the columnar hind limbs and long tail of sauropodomorphs. This further highlights the non-uniform distribution and acquisition of typically sauropodomorph traits in other herbivorous archosauromorphs.

The age of ''Azendohsaurus'' is also significant, as it was roughly coeval with the earliest known sauropodomorphs from Carnian

The Carnian (less commonly, Karnian) is the lowermost stage of the Upper Triassic Series (or earliest age of the Late Triassic Epoch). It lasted from 237 to 227 million years ago (Ma). The Carnian is preceded by the Ladinian and is followe ...

South America, such as the lightweight, bipedal ''Saturnalia

Saturnalia is an ancient Roman festival and holiday in honour of the god Saturn, held on 17 December of the Julian calendar and later expanded with festivities through to 23 December. The holiday was celebrated with a sacrifice at the Temple o ...

''. However, ''Azendohsaurus'' resembles the later Norian

The Norian is a division of the Triassic Period. It has the rank of an age ( geochronology) or stage (chronostratigraphy). It lasted from ~227 to million years ago. It was preceded by the Carnian and succeeded by the Rhaetian.

Stratigraphic ...

sauropodomorphs more closely, both in general anatomy and its larger body size. This suggests that azendohsaurids had been the first reptiles to evolve as high browsing herbivores in Triassic ecosystems, prior to the evolution of the larger sauropodomorphs, which had previously been assumed to have been the first high browsing herbivores. It also indicates that the convergence between ''Azendohsaurus'' and sauropodomorphs did not occur under the same environmental circumstances, as ''Azendohsaurus'' was part of an initial wave of herbivory in archosauromorphs (along with rhynchosaurs, silesaurids and cynodonts) and large sauropodomorphs in a second wave (along with herbivorous pseudosuchians).

''Azendohsaurus'' also demonstrates that archosauromorphs were occupying roles as large herbivores in Triassic ecosystems earlier in their evolutionary history than had been assumed. These roles were previously thought to be dominated by large synapsid

Synapsids + (, 'arch') > () "having a fused arch"; synonymous with ''theropsids'' (Greek, "beast-face") are one of the two major groups of animals that evolved from basal amniotes, the other being the sauropsids, the group that includes rep ...

s such as dicynodonts prior to the radiation of archosaurs in the Late Triassic, but ''Azendohsaurus'' suggests that earlier archosauromorphs were also capable of competing with synapsid herbivores.

Palaeobiology

Feeding and diet

The leaf-shaped teeth of ''Azendohsaurus'' are clearly suited for a herbivorous lifestyle, and microwear—marks left on the tooth surface during feeding—on the teeth of ''A. madagaskarensis'' suggest they were used for browsing on vegetation that was not especially tough or woody, preferring softer (but firm) vegetation. The microwear patterns also show that it used a simple up-and-down motion of the jaw, and did not use complex jaw movement to chew its food like ornithischian dinosaurs or contemporary cynodonts. This microwear has not yet been observed on the teeth of ''A. laaroussii'', but it is unknown if this is a genuine feature relating to a difference in diet and feeding habits between the two species or if it is just a feature of preservation.

The fully developed palatal teeth suggest that it was using them for feeding in a specialised manner. However, no functional studies have been performed on the palatal teeth so it is unknown exactly what they were used for, although their similar shape to the marginal teeth suggests they were used for processing similar food. A pterygoid from a younger individual of ''A. madagaskarensis'' has fewer rows of palatal teeth that are smaller in size than those of the larger, mature individuals, indicating that ''Azendohsaurus'' increased both the number and size of its palatal teeth as it grew into adulthood. Younger individuals also had fewer dentary teeth than adults, although the difference was much less extreme compared to the palatal teeth (16 compared to the 17 of mature specimens).

The leaf-shaped teeth of ''Azendohsaurus'' are clearly suited for a herbivorous lifestyle, and microwear—marks left on the tooth surface during feeding—on the teeth of ''A. madagaskarensis'' suggest they were used for browsing on vegetation that was not especially tough or woody, preferring softer (but firm) vegetation. The microwear patterns also show that it used a simple up-and-down motion of the jaw, and did not use complex jaw movement to chew its food like ornithischian dinosaurs or contemporary cynodonts. This microwear has not yet been observed on the teeth of ''A. laaroussii'', but it is unknown if this is a genuine feature relating to a difference in diet and feeding habits between the two species or if it is just a feature of preservation.

The fully developed palatal teeth suggest that it was using them for feeding in a specialised manner. However, no functional studies have been performed on the palatal teeth so it is unknown exactly what they were used for, although their similar shape to the marginal teeth suggests they were used for processing similar food. A pterygoid from a younger individual of ''A. madagaskarensis'' has fewer rows of palatal teeth that are smaller in size than those of the larger, mature individuals, indicating that ''Azendohsaurus'' increased both the number and size of its palatal teeth as it grew into adulthood. Younger individuals also had fewer dentary teeth than adults, although the difference was much less extreme compared to the palatal teeth (16 compared to the 17 of mature specimens).

Body posture

The body posture inferred for ''Azendohsaurus'' is a mixture of sprawled and semi-sprawled. The hind limbs have been interpreted as being completely sprawled outwards from the body, with its femur held straight out and the lower leg bent 90° beneath it at the knee, like alizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia al ...

. The forelimbs and shoulder girdle, however, suggest that the front of the body was held more upright than the hind quarters, with a partly downward directed shoulder socket and a humerus more suited for being held partially erect, and was similar in shape to those of sauropodomorphs. This unusual combination suggests that ''Azendohsaurus'' stood with its front end raised up off from the ground, which combined with its long, arched neck and small head, allowed it to browse relatively high off the ground, unlike contemporary low-browsing rhynchosaurs and cynodonts. Adapting to high-browsing could possibly explain the convergence between ''Azendohsaurus'' and sauropodomorphs, acquiring similar traits of the neck, forelimbs and spine to perform in similar niches. However, the more sprawling posture of ''Azendohsaurus'' probably inhibited high-browsing like that of the fully erect sauropodomorphs.

Palaeopathology

Despite the multitude of specimens present in the bone bed that was examined, only a singlepathology

Pathology is the study of the causes and effects of disease or injury. The word ''pathology'' also refers to the study of disease in general, incorporating a wide range of biology research fields and medical practices. However, when used in ...

has been recorded in ''A. madagaskarensis''. Specimen UA 7-16-99-620, one of the three preserved interclavicles, had been malformed so that the long posterior process had been sharply bent to the right, compared to the normal straight posterior processes of the other two interclavicles.

Metabolism and growth

In 2019, thin slices were cut from the humerus, femur and tibia of specimens attributed to ''A. laaroussii'' for histological examination of the microscopic bone structure to try and determine the rate of growth in ''Azendohsaurus''. The vascular density (the density of blood vessels in the bone tissue) in all three limb bones was found to be comparable to those of fast-growingbirds

Birds are a group of warm-blooded vertebrates constituting the class Aves (), characterised by feathers, toothless beaked jaws, the laying of hard-shelled eggs, a high metabolic rate, a four-chambered heart, and a strong yet lightweig ...

and mammals

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fu ...

, and the types of bone tissue identified—particularly energy-consuming fibrolamellar bone tissue—were interpreted as indicating a high resting metabolic rate that was in the range of living birds and mammals. It was inferred then that, like birds and mammals, ''Azendohsaurus'' would also likewise have been endothermic

In thermochemistry, an endothermic process () is any thermodynamic process with an increase in the enthalpy (or internal energy ) of the system.Oxtoby, D. W; Gillis, H.P., Butler, L. J. (2015).''Principle of Modern Chemistry'', Brooks Cole. p. ...

, or "warm-blooded". High resting metabolic rates similar to those of ''Azendohsaurus'' had been identified in other more derived archosauromorphs (such as '' Prolacerta''), and analyses suggested that endothermy may then have been ancestrally present in archosauromorphs as far back as their common ancestor with allokotosaurs. This suggests that ''Azendohsaurus'' may then have been ancestrally endothermic. By contrast, the related allokotosaur ''Trilophosaurus'' was previously found to not have any fibrolamellar bone tissue in its limb bones and so was inferred to have grown slowly.

Palaeoecology

Although the two species of ''Azendohsaurus'' are known from disparate locations in North Africa and Madagascar, during the Middle to Late Triassic these regions were connected as part of thesupercontinent

In geology, a supercontinent is the assembly of most or all of Earth's continental blocks or cratons to form a single large landmass. However, some geologists use a different definition, "a grouping of formerly dispersed continents", which lea ...

Pangaea

Pangaea or Pangea () was a supercontinent that existed during the late Paleozoic and early Mesozoic eras. It assembled from the earlier continental units of Gondwana, Euramerica and Siberia during the Carboniferous approximately 335 millio ...

. Because of this, the two regions share broadly similar faunas, as well as sharing some with other regions of the globe at the time. For example, the cynodonts in Madagascar are similar to those also found in South America, and the Moroccan temnospondyls may be related to those found in eastern North America. The climate was hot and dry at this time, but with evidence suggesting higher levels of rainfall during the Carnian, interrupting the increasing aridity trend and creating wetter environments around the globe.

Timezgadiouine Formation, Morocco

Other reptiles from the base of the Irohalene (T5) member of the Timezgadiouine Formation contemporaneous with ''A. laaroussii'' include the phytosaur ''Arganarhinus

''Arganarhinus'' (meaning "Argana (Morocco) snout") is an extinct genus of phytosaur known from the late Triassic period (geology), period (Middle Carnian stage) of Argana Basin in Morocco. It is known from a skull which is housed at the Muséum ...