Aryanization In Slovakia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The Holocaust in Slovakia was the systematic dispossession, deportation, and murder of

Before 1939, Slovakia had never been an independent country; its territory was part of the

Before 1939, Slovakia had never been an independent country; its territory was part of the

The September 1938

The September 1938

Immediately after Slovakia was established as a state in 1938, the government began firing its Jewish employees. The

Immediately after Slovakia was established as a state in 1938, the government began firing its Jewish employees. The  Initially, many Jews believed that the measures taken against them would be temporary. Nevertheless, some attempted to emigrate and take their property with them. Between December 1938 and February 1939, more than 2.25 million Kčs were transferred illegally to the Czech lands, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; further amounts were transferred legally. Slovak government officials took advantage of the circumstances to purchase the property of wealthy Jewish emigrants at a significant discount, a precursor to the state-sponsored transfer of Jewish property as part of

Initially, many Jews believed that the measures taken against them would be temporary. Nevertheless, some attempted to emigrate and take their property with them. Between December 1938 and February 1939, more than 2.25 million Kčs were transferred illegally to the Czech lands, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; further amounts were transferred legally. Slovak government officials took advantage of the circumstances to purchase the property of wealthy Jewish emigrants at a significant discount, a precursor to the state-sponsored transfer of Jewish property as part of

At the July 1940

At the July 1940

Jews serving in the army were segregated into a labor unit in April 1939 and were stripped of their rank at the end of the year. From 1940, male Jews and Romani people were obliged to work for the national defense (generally manual labor on construction projects) for two months every year. All recruits considered Jewish or Romani were allocated to the

Jews serving in the army were segregated into a labor unit in April 1939 and were stripped of their rank at the end of the year. From 1940, male Jews and Romani people were obliged to work for the national defense (generally manual labor on construction projects) for two months every year. All recruits considered Jewish or Romani were allocated to the

In accordance with Catholic teaching on race, antisemitic laws initially defined Jews by religion rather than ancestry; Jews who were baptized before 1918 were considered Christian. By September 1940, Jews were banned from secondary and higher education and from all non-Jewish schools, and forbidden from owning motor vehicles, sports equipment, or radios. Local authorities had imposed anti-Jewish measures on their own; the head of the Šariš-Zemplín region ordered local Jews to wear a yellow band around their left arm from 5 April 1941, leading to physical attacks against Jews. In mid-1941, as the focus shifted to restricting Jews' civil rights after they had been deprived of their property through Aryanization,

In accordance with Catholic teaching on race, antisemitic laws initially defined Jews by religion rather than ancestry; Jews who were baptized before 1918 were considered Christian. By September 1940, Jews were banned from secondary and higher education and from all non-Jewish schools, and forbidden from owning motor vehicles, sports equipment, or radios. Local authorities had imposed anti-Jewish measures on their own; the head of the Šariš-Zemplín region ordered local Jews to wear a yellow band around their left arm from 5 April 1941, leading to physical attacks against Jews. In mid-1941, as the focus shifted to restricting Jews' civil rights after they had been deprived of their property through Aryanization,

The highest levels of the Slovak government were aware by late 1941 of mass murders of Jews in German-occupied territories. In July 1941, Wisliceny organized a visit by Slovak government officials to several camps run by

The highest levels of the Slovak government were aware by late 1941 of mass murders of Jews in German-occupied territories. In July 1941, Wisliceny organized a visit by Slovak government officials to several camps run by

The original deportation plan, approved in February 1942, entailed the deportation of 7,000 women to Auschwitz and 13,000 men to

The original deportation plan, approved in February 1942, entailed the deportation of 7,000 women to Auschwitz and 13,000 men to

Transports went to Auschwitz after mid-June, where a minority of the victims were selected for labor and the remainder were killed in the

Transports went to Auschwitz after mid-June, where a minority of the victims were selected for labor and the remainder were killed in the

In late 1943, leading army officers and

In late 1943, leading army officers and

Concerned about the increase in resistance, Germany invaded Slovakia; this precipitated the

Concerned about the increase in resistance, Germany invaded Slovakia; this precipitated the

Sereď concentration camp was the primary facility for interning Jews before their deportation. Although there were no transports until the end of September, the Jews experienced harsh treatment (including rape and murder) and severe overcrowding as the population swelled to 3,000 – more than twice the intended capacity. Brunner took over the camp's administration from the Slovak government at the end of September. About 11,700 people were deported on eleven transports; the first five (from 30 September to 17 October) went to Auschwitz, where most of the victims were gassed. The final transport to Auschwitz, on 2 November, arrived after the gas chambers were shut down. Later transports left for

Sereď concentration camp was the primary facility for interning Jews before their deportation. Although there were no transports until the end of September, the Jews experienced harsh treatment (including rape and murder) and severe overcrowding as the population swelled to 3,000 – more than twice the intended capacity. Brunner took over the camp's administration from the Slovak government at the end of September. About 11,700 people were deported on eleven transports; the first five (from 30 September to 17 October) went to Auschwitz, where most of the victims were gassed. The final transport to Auschwitz, on 2 November, arrived after the gas chambers were shut down. Later transports left for

The

The

The government's attitude to Jews and Zionism shifted after 1948, leading to the 1952

The government's attitude to Jews and Zionism shifted after 1948, leading to the 1952

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

in the Slovak State

Slovak may refer to:

* Something from, related to, or belonging to Slovakia (''Slovenská republika'')

* Slovaks, a Western Slavic ethnic group

* Slovak language, an Indo-European language that belongs to the West Slavic languages

* Slovak, Arkan ...

, a client state

A client state, in international relations, is a state that is economically, politically, and/or militarily subordinate to another more powerful state (called the "controlling state"). A client state may variously be described as satellite sta ...

of Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

, during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

. Out of 89,000 Jews in the country in 1940, an estimated 69,000 were murdered in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

.

After the September 1938 Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

, Slovakia unilaterally declared its autonomy within Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

, but lost significant territory to Hungary in the First Vienna Award

The First Vienna Award was a treaty signed on 2 November 1938 pursuant to the Vienna Arbitration, which took place at Vienna's Belvedere Palace. The arbitration and award were direct consequences of the previous month's Munich Agreement, which ...

, signed in November. The following year, with German encouragement, the ruling ethnonationalist Slovak People's Party

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party ( sk, Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana), also known as the Slovak People's Party (, SĽS) or the Hlinka Party, was a far-right clerico-fascist political party with a strong Catholic fundamentalist and authorita ...

declared independence from Czechoslovakia. State propaganda blamed the Jews for the territorial losses. Jews were targeted for discrimination and harassment, including the confiscation of their property and businesses. The exclusion of Jews from the economy impoverished the community, which encouraged the government to conscript them for forced labor. On 9 September 1941, the government passed the Jewish Code, which it claimed to be the strictest anti-Jewish law in Europe.

In 1941, the Slovak government negotiated with Nazi Germany for the mass deportation of Jews to German-occupied Poland

German-occupied Poland during World War II consisted of two major parts with different types of administration.

The Polish areas annexed by Nazi Germany following the invasion of Poland at the beginning of World War II—nearly a quarter of the ...

. Between March and October 1942, 58,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz concentration camp and the Lublin District

Lublin District (german: Distrikt Lublin) was one of the first four Nazi districts of the General Governorate region of German-occupied Poland during World War II, along with Warsaw District, Radom District, and Kraków District. On the south ...

of the General Governorate

The General Government (german: Generalgouvernement, pl, Generalne Gubernatorstwo, uk, Генеральна губернія), also referred to as the General Governorate for the Occupied Polish Region (german: Generalgouvernement für die be ...

; only a few hundred survived until the end of the war. The Slovak government organized the transports and paid 500 Reichsmarks

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reichs ...

per Jew for the supposed cost of resettlement. The persecution of Jews resumed in August 1944, when Germany invaded Slovakia and triggered the Slovak National Uprising

The Slovak National Uprising ( sk, Slovenské národné povstanie, abbreviated SNP) was a military uprising organized by the Slovak resistance movement during World War II. This resistance movement was represented mainly by the members of the D ...

. Another 13,500 Jews were deported and hundreds to thousands were murdered in Slovakia by Einsatzgruppe H

Einsatzgruppe H was one of the ''Einsatzgruppen'', the paramilitary death squads of Nazi Germany. A special task force of more than 700 soldiers, it was created at the end of August 1944 to deport or murder the remaining Jews in Slovakia followi ...

and the Hlinka Guard Emergency Divisions The Hlinka Guard Emergency Divisions or Flying Squads of the Hlinka Guard ( sk, Pohotovostné oddiely Hlinkovej gardy, POHG) were Slovak paramilitary formations set up to counter the August 1944 Slovak National Uprising. They are best known for the ...

.

After liberation by the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian language, Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist R ...

, survivors faced renewed antisemitism and difficulty regaining stolen property; most emigrated after the 1948 Communist coup

Events January

* January 1

** The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) is inaugurated.

** The Constitution of New Jersey (later subject to amendment) goes into effect.

** The railways of Britain are nationalized, to form British ...

. The postwar Communist regime censored discussion of the Holocaust; free speech was restored after the fall of the Communist regime in 1989. The Slovak government's complicity in the Holocaust continues to be disputed by far-right nationalists.

Background

Before 1939, Slovakia had never been an independent country; its territory was part of the

Before 1939, Slovakia had never been an independent country; its territory was part of the Kingdom of Hungary

The Kingdom of Hungary was a monarchy in Central Europe that existed for nearly a millennium, from the Middle Ages into the 20th century. The Principality of Hungary emerged as a Christian kingdom upon the coronation of the first king Stephe ...

for a thousand years. Seventeen medieval Jewish communities have been documented in the territory of modern-day Slovakia, but significant Jewish presence was ended with the expulsions following the Hungarian defeat at the Battle of Mohács

The Battle of Mohács (; hu, mohácsi csata, tr, Mohaç Muharebesi or Mohaç Savaşı) was fought on 29 August 1526 near Mohács, Kingdom of Hungary, between the forces of the Kingdom of Hungary and its allies, led by Louis II, and thos ...

in 1526. Many Jews immigrated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Jews from Moravia

Moravia ( , also , ; cs, Morava ; german: link=yes, Mähren ; pl, Morawy ; szl, Morawa; la, Moravia) is a historical region in the east of the Czech Republic and one of three historical Czech lands, with Bohemia and Czech Silesia.

Th ...

settled west of the Tatra Mountains

The Tatra Mountains (), Tatras, or Tatra (''Tatry'' either in Slovak () or in Polish () - '' plurale tantum''), are a series of mountains within the Western Carpathians that form a natural border between Slovakia and Poland. They are the h ...

, forming the Oberlander Jews Oberlander Jews ( yi, אויבערלאנד, translit. ''Oyberland'', "Highland"; he, גליל עליון, translit. ''Galil E'lion'', "Upper Province") were the Jews who inhabited the northwestern regions of the historical Kingdom of Hungary, whic ...

, while Jews from Galicia settled east of the mountains, forming a separate community (Unterlander Jews Unterlander Jews ( yi, אונטערלאנד, translit. ''Unterland'', "Lowland"; he, גליל תחתון, translit. ''Galil Takhton'', "Lower Province"; hu, Alföldi Zsidók) were the Jews who resided in the northeastern regions of the historical ...

) influenced by Hasidism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism ( Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory of cont ...

. Due to the schism in Hungarian Jewry

The Schism in Hungarian Jewry ( hu, ortodox–neológ szakadás, "Orthodox-Neolog Schism"; yi, די טיילונג אין אונגארן, trans. ''Die Teilung in Ungarn'', "The Division in Hungary") was the institutional division of the Jewish co ...

, communities split in the mid-nineteenth century into Orthodox (the majority), Status Quo, and more assimilated Neolog

Neologs ( hu, neológ irányzat, "Neolog faction") are one of the two large communal organizations among Hungarian Jewry. Socially, the liberal and modernist Neologs had been more inclined toward integration into Hungarian society since the Era ...

factions. Following Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It ...

, complete by 1896, many Jews adopted the Hungarian language

Hungarian () is an Uralic language spoken in Hungary and parts of several neighbouring countries. It is the official language of Hungary and one of the 24 official languages of the European Union. Outside Hungary, it is also spoken by Hunga ...

and customs to advance in society.

Although they were not as integrated as the Jews of Bohemia and Moravia

The history of the Jews in the Czech lands, which include the modern Czech Republic as well as Bohemia, Czech Silesia and Moravia, goes back many centuries. There is evidence that Jews have lived in Moravia and Bohemia since as early as the 10 ...

, many Slovak Jews moved to cities and joined all the professions; others remained in the countryside, mostly working as artisans, merchants, and shopkeepers. Jews spearheaded the nineteenth-century economic changes that led to greater commerce in rural areas; by the end of the century some 70 percent of the bankers and businessmen in the Slovak uplands were Jewish. Although a few Jews supported Slovak nationalism

Slovak nationalism is an ethnic nationalist ideology that asserts that the Slovaks are a nation and promotes the cultural unity of the Slovaks.

History

Modern Slovak nationalism first arose in the 19th century in response to Magyarization of Slov ...

, by the mid-nineteenth century antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

had become a theme in the Slovak national movement

The History of Slovakia, dates back to the findings of ancient human artifacts. This article shows the history of the country from prehistory to the present day.

Prehistory

Discovery of ancient tools made by the Clactonian technique near ...

, Jews being branded "agents of magyarization

Magyarization ( , also ''Hungarization'', ''Hungarianization''; hu, magyarosítás), after "Magyar"—the Hungarian autonym—was an assimilation or acculturation process by which non-Hungarian nationals living in Austro-Hungarian Transleitha ...

" and "the most powerful prop to the ungarianruling classes", in the words of historian Thomas Lorman Thomas Anselm Lorman is a historian who studies Central Europe.

Works

*

*

References

Historians of Hungary

Historians of Slovakia

Year of birth missing (living people)

Living people

{{historian-stub ...

. In the western Slovak lands, anti-Jewish riots broke out in the wake of the Revolutions of 1848

The Revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the Springtime of the Peoples or the Springtime of Nations, were a series of political upheavals throughout Europe starting in 1848. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in Euro ...

; more riots occurred due to the Tiszaeszlár blood libel

Tiszaeszlár (Old form: ''Tisza-Eszlár'') is a village in Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg, Hungary.

In 1882 the village was the centre of blood libel accusations against its Jewish community. They were accused of murdering and beheading a young gi ...

in 1882–1883. Traditional religious antisemitism

Religious antisemitism is aversion to or discrimination against Jews as a whole, based on religious doctrines of supersession that expect or demand the disappearance of Judaism and the conversion of Jews, and which figure their political enem ...

was joined by the stereotypical view of Jews as exploiters of poor Slovaks (economic antisemitism

Economic antisemitism is antisemitism that uses stereotypes and canards that are based on negative perceptions or assertions of the economic status, occupations or economic behaviour of Jews, at times leading to various governmental policies and ...

), and national antisemitism: Jews were strongly associated with the Hungarian state and accused of sympathizing with Hungarian at the expense of Slovak ambitions.

After World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

, Slovakia became part of the new country of Czechoslovakia

, rue, Чеськословеньско, , yi, טשעכאסלאוואקיי,

, common_name = Czechoslovakia

, life_span = 1918–19391945–1992

, p1 = Austria-Hungary

, image_p1 ...

. Jews lived in 227 communities (in 1918) and their population was estimated at 135,918 (in 1921). Anti-Jewish riots broke out in the aftermath of the declaration of independence (1918–1920), although the violence was not nearly as serious as in Ukraine or Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, , is a country in Central Europe. Poland is divided into Voivodeships of Poland, sixteen voivodeships and is the fifth most populous member state of the European Union (EU), with over 38 mill ...

. Slovak nationalists associated Jews with the Czechoslovak state and accused them of supporting Czechoslovakism

Czechoslovakism ( cs, Čechoslovakismus, sk, Čechoslovakizmus) is a concept which underlines reciprocity of the Czechs and the Slovaks. It is best known as an ideology which holds that there is one Czechoslovak nation, though it might also appe ...

. Blood libel

Blood libel or ritual murder libel (also blood accusation) is an antisemitic canardTurvey, Brent E. ''Criminal Profiling: An Introduction to Behavioral Evidence Analysis'', Academic Press, 2008, p. 3. "Blood libel: An accusation of ritual mu ...

accusations occurred in Trenčin and in Šalavský Gemer in the 1920s. In the 1930s, the Great Depression affected Jewish businessmen and also increased economic antisemitism. Economic underdevelopment and perceptions of discrimination in Czechoslovakia led a plurality (about one-third) of Slovaks to support the conservative, ethnonationalist Slovak People's Party

Hlinka's Slovak People's Party ( sk, Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana), also known as the Slovak People's Party (, SĽS) or the Hlinka Party, was a far-right clerico-fascist political party with a strong Catholic fundamentalist and authorita ...

( sk, Hlinkova slovenská ľudová strana: HSĽS). HSĽS viewed minority groups such as Czechs, Hungarians, Jews, and Romani people

The Romani (also spelled Romany or Rromani , ), colloquially known as the Roma, are an Indo-Aryan ethnic group, traditionally nomadic itinerants. They live in Europe and Anatolia, and have diaspora populations located worldwide, with sig ...

as a destructive influence on the Slovak nation, and presented Slovak autonomy as the solution to Slovakia's problems. The party began to emphasize antisemitism during the late 1930s following a wave of Jewish refugees from Austria in 1938 and anti-Jewish laws passed by Hungary, Poland, and Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, Serbia to the southwest, Moldova to the east, a ...

.

Slovak independence

The September 1938

The September 1938 Munich Agreement

The Munich Agreement ( cs, Mnichovská dohoda; sk, Mníchovská dohoda; german: Münchner Abkommen) was an agreement concluded at Munich on 30 September 1938, by Germany, the United Kingdom, France, and Italy. It provided "cession to Germany ...

ceded the Sudetenland

The Sudetenland ( , ; Czech and sk, Sudety) is the historical German name for the northern, southern, and western areas of former Czechoslovakia which were inhabited primarily by Sudeten Germans. These German speakers had predominated in the ...

, the German-speaking region of the Czech lands

The Czech lands or the Bohemian lands ( cs, České země ) are the three historical regions of Bohemia, Moravia, and Czech Silesia. Together the three have formed the Czech part of Czechoslovakia since 1918, the Czech Socialist Republic sinc ...

, to Germany. HSĽS took advantage of the ensuing political chaos to declare Slovakia's autonomy on 6 October. Jozef Tiso

Jozef Gašpar Tiso (; hu, Tiszó József; 13 October 1887 – 18 April 1947) was a Slovak politician and Roman Catholic priest who served as president of the Slovak Republic, a client state of Nazi Germany during World War II, from 1939 to 1945 ...

, a Catholic priest

The priesthood is the office of the ministers of religion, who have been commissioned ("ordained") with the Holy orders of the Catholic Church. Technically, bishops are a priestly order as well; however, in layman's terms ''priest'' refers only ...

and HSĽS leader, became prime minister of the Slovak autonomous region. Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, the religion of 80 percent of the country's inhabitants, was key to the regime with many of its leaders being bishops, priests, or laymen. Under Tiso's leadership, the Slovak government opened negotiations in Komárno with Hungary regarding their border. The dispute was submitted to arbitration in Vienna by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and the ...

. Hungary was awarded much of southern Slovakia on 2 November, including 40 percent of Slovakia's arable land and 270,000 people who had declared Czechoslovak ethnicity.

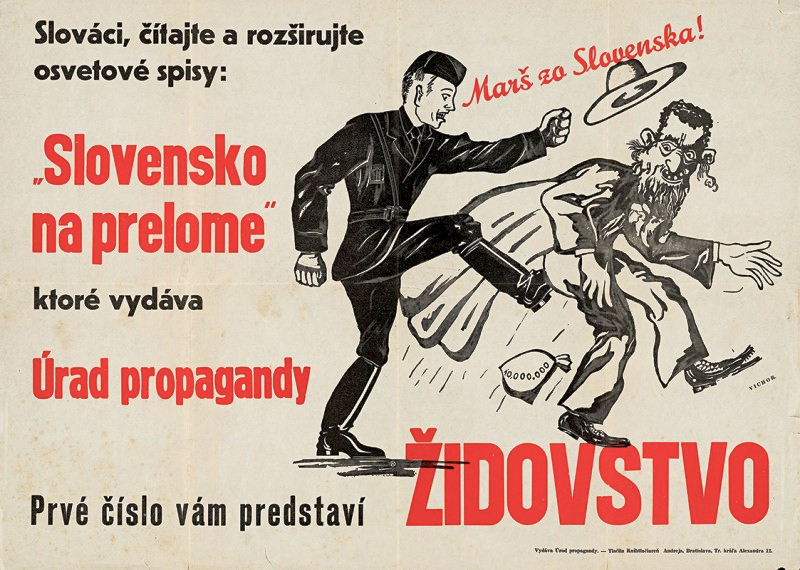

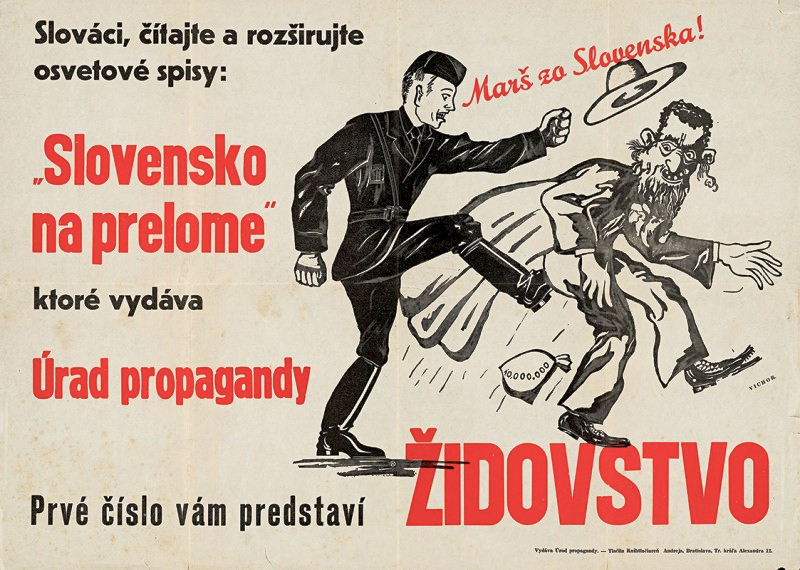

HSĽS consolidated its power by passing an enabling act

An enabling act is a piece of legislation by which a legislative body grants an entity which depends on it (for authorization or legitimacy) the power to take certain actions. For example, enabling acts often establish government agencies to c ...

, banning opposition parties, shutting down independent newspapers, distributing antisemitic and anti-Czech propaganda, and founding the paramilitary Hlinka Guard Hlinka (feminine Hlinková) is a Czech and Slovak surname. Notable people with the surname include:

* Andrej Hlinka, Slovak politician and Catholic priest

* Ivan Hlinka, Czech ice hockey player and coach

*Jaroslav Hlinka, Czech ice hockey player

...

. Parties for the German and Hungarian minorities were allowed under HSĽS hegemony, and the German Party formed the militia. HSĽS imprisoned thousands of its political opponents, but never carried out a sentence of capital punishment. Un-free elections in December 1938 resulted in a 95-percent vote for HSĽS.

On 14 March 1939, the Slovak State

Slovak may refer to:

* Something from, related to, or belonging to Slovakia (''Slovenská republika'')

* Slovaks, a Western Slavic ethnic group

* Slovak language, an Indo-European language that belongs to the West Slavic languages

* Slovak, Arkan ...

proclaimed its independence with German support and protection. Germany annexed and invaded the Czech rump state

A rump state is the remnant of a once much larger state, left with a reduced territory in the wake of secession, annexation, occupation, decolonization, or a successful coup d'état or revolution on part of its former territory. In the last cas ...

the following day, and Hungary seized Carpathian Ruthenia

Carpathian Ruthenia ( rue, Карпатьска Русь, Karpat'ska Rus'; uk, Закарпаття, Zakarpattia; sk, Podkarpatská Rus; hu, Kárpátalja; ro, Transcarpatia; pl, Zakarpacie); cz, Podkarpatská Rus; german: Karpatenukrai ...

with German acquiescence. In a treaty signed on 23 March, Slovakia renounced much of its foreign policy and military autonomy to Germany in exchange for border guarantees and economic assistance. It was neither fully independent nor a German puppet state

A puppet state, puppet régime, puppet government or dummy government, is a state that is ''de jure'' independent but ''de facto'' completely dependent upon an outside power and subject to its orders.Compare: Puppet states have nominal sover ...

, but occupied an intermediate status. In October 1939, Tiso, leader of the conservative-clerical

Clerical may refer to:

* Pertaining to the clergy

* Pertaining to a clerical worker

* Clerical script, a style of Chinese calligraphy

* Clerical People's Party

See also

* Cleric (disambiguation)

Cleric is a member of the clergy.

Cleric may al ...

branch of HSĽS, became president; Vojtech Tuka

Vojtech Lázar "Béla" Tuka (4 July 1880 – 20 August 1946) was a Slovak politician who served as prime minister and minister of Foreign Affairs of the First Slovak Republic between 1939 and 1945. Tuka was one of the main forces behind the depor ...

, leader of the party's radical fascist wing, was appointed prime minister. Both wings of the party struggled for Germany's favor. The radical wing of the party was pro-German, while the conservatives favored autonomy from Germany; the radicals relied on the Hlinka Guard and German support, while Tiso was popular among the clergy and the population.

Anti-Jewish measures (1938–1941)

Initial actions

Immediately after Slovakia was established as a state in 1938, the government began firing its Jewish employees. The

Immediately after Slovakia was established as a state in 1938, the government began firing its Jewish employees. The Committee for the Solution of the Jewish Question

A committee or commission is a body of one or more persons subordinate to a deliberative assembly. A committee is not itself considered to be a form of assembly. Usually, the assembly sends matters into a committee as a way to explore them more ...

was founded on 23 January 1939 to discuss anti-Jewish legislation. The state-sponsored media demonized Jews as "enemies of the state

An enemy of the state is a person accused of certain crimes against the state such as treason, among other things. Describing individuals in this way is sometimes a manifestation of political repression. For example, a government may purport to ...

" and of the Slovak nation. Jewish businesses were robbed, and physical attacks on Jews occurred both spontaneously and at the instigation of the Hlinka Guard and . In his first radio address following the establishment of the Slovak State in 1939, Tiso emphasized his desire to "solve the Jewish Question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

"; anti-Jewish legislation was the only concrete measure that he promised. The persecution of Jews was a key element of the state's domestic policy. Discriminatory measures affected all aspects of life, serving to isolate and dispossess Jews before they were deported.

In the days after the announcement of the First Vienna Award

The First Vienna Award was a treaty signed on 2 November 1938 pursuant to the Vienna Arbitration, which took place at Vienna's Belvedere Palace. The arbitration and award were direct consequences of the previous month's Munich Agreement, which ...

, antisemitic rioting broke out in Bratislava; newspapers justified the riots with Jews' alleged support for Hungary during the partition negotiations. Adolf Eichmann

Otto Adolf Eichmann ( ,"Eichmann"

'' Czechoslovak koruna The Czechoslovak koruna (in Czech and Slovak: ''Koruna československá'', at times ''Koruna česko-slovenská''; ''koruna'' means ''crown'') was the currency of Czechoslovakia from 10 April 1919 to 14 March 1939, and from 1 November 1945 to 7 F ...

(Kčs) were arrested in an unsuccessful attempt to prevent '' Czechoslovak koruna The Czechoslovak koruna (in Czech and Slovak: ''Koruna československá'', at times ''Koruna česko-slovenská''; ''koruna'' means ''crown'') was the currency of Czechoslovakia from 10 April 1919 to 14 March 1939, and from 1 November 1945 to 7 F ...

capital flight

Capital flight, in economics, occurs when assets or money rapidly flow out of a country, due to an event of economic consequence or as the result of a political event such as regime change or economic globalization. Such events could be an increas ...

. Between 4 and 7 November, 4,000 or 7,600 Jews were deported, in a chaotic, pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian ...

-like operation in which the Hlinka Guard, the , and the German Party participated. The deportees included young children, the elderly, and pregnant women. A few days later, Tiso canceled the operation; most of the Jews were allowed to return home in December. More than 800 were confined to makeshift tent camps at Veľký Kýr, Miloslavov

Miloslavov ( hu, Annamajor) is a village and municipality in western Slovakia in Senec District in the Bratislava Region.

History

In historical records the village was first mentioned in 1332–1337.

Geography

The municipality lies at an altitud ...

, and Šamorín

Šamorín (; hu, Somorja, german: Sommerein) is a small town in western Slovakia, southeast of Bratislava.

Etymology

The name is derived from a patron saint of a local church Sancta Maria, mentioned for the first time as ''villa Sancti Marie'' ...

on the new Slovak–Hungarian border during the winter. The Slovak deportations occurred just after Germany's deportation of thousands of Polish Jews, attracted international criticism, reduced British investment, increased dependence on German capital, and were a rehearsal for the 1942 deportations.

Initially, many Jews believed that the measures taken against them would be temporary. Nevertheless, some attempted to emigrate and take their property with them. Between December 1938 and February 1939, more than 2.25 million Kčs were transferred illegally to the Czech lands, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; further amounts were transferred legally. Slovak government officials took advantage of the circumstances to purchase the property of wealthy Jewish emigrants at a significant discount, a precursor to the state-sponsored transfer of Jewish property as part of

Initially, many Jews believed that the measures taken against them would be temporary. Nevertheless, some attempted to emigrate and take their property with them. Between December 1938 and February 1939, more than 2.25 million Kčs were transferred illegally to the Czech lands, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom; further amounts were transferred legally. Slovak government officials took advantage of the circumstances to purchase the property of wealthy Jewish emigrants at a significant discount, a precursor to the state-sponsored transfer of Jewish property as part of Aryanization

Aryanization (german: Arisierung) was the Nazi term for the seizure of property from Jews and its transfer to non-Jews, and the forced expulsion of Jews from economic life in Nazi Germany, Axis-aligned states, and their occupied territories. I ...

. Interest in emigration among Jews surged after the invasion of Poland

The invasion of Poland (1 September – 6 October 1939) was a joint attack on the Republic of Poland by Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union which marked the beginning of World War II. The German invasion began on 1 September 1939, one week af ...

, as Jewish refugees from Poland told of atrocities there. Although the Slovak government encouraged Jews to emigrate, it refused to allow the export of foreign currency, ensuring that most attempts remained unsuccessful. No country was eager to accept Jewish refugees, and the tight limits imposed by the United Kingdom on legal emigration to Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 i ...

prevented Jews from seeking refuge there. In 1940, Bratislava became a hub for operatives organizing illegal immigration to Palestine, one of whom, Aron Grünhut

Aron Grünhut (1895–1974) was a Bratislava-based Jewish activist who helped 1,365 Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, and Austrian Jews illegally emigrate to Palestine before and during World War II. Grünhut later received an unauthorized Salvedorean vis ...

, helped 1,365 Slovak, Czech, Hungarian, and Austrian Jews emigrate. By early 1941, further emigration was impossible; even Jews who received valid United States visas were not allowed transit visas through Germany. The total number of Slovak Jewish emigrants has been estimated at 5,000 to 6,000. As 45,000 lived in the areas ceded to Hungary, the 1940 census found that 89,000 Jews lived in the Slovak State, 3.4 percent of the population.

Aryanization

Aryanization in Slovakia, the seizure of Jewish-owned property and exclusion of Jews from the economy, was justified by the stereotype (reinforced by HSĽS propaganda) of Jews obtaining their wealth by oppressing Slovaks. Between 1939 and 1942, the HSĽS regime received widespread popular support by promising Slovak citizens that they would be enriched by property confiscated from Jews and other minorities. They stood to gain a significant amount of money; in 1940, Jews registered more than 4.322 billionSlovak koruna

The Slovak koruna or Slovak crown ( sk, slovenská koruna, literally meaning ''Slovak crown'') was the currency of Slovakia between 8 February 1993 and 31 December 2008, and could be used for cash payment until 16 January 2009. The ISO 4217 code w ...

(Ks) in property (38 percent of the national wealth). The process is also described as "Slovakization", as the Slovak government took steps to ensure that ethnic Slovaks, rather than Germans or other minorities, received the stolen Jewish property. Due to the intervention of the German Party and Nazi Germany, ethnic Germans received 8.3 percent of the stolen property, but most German applicants were refused, underscoring the freedom of action of the Slovak government.

The first anti-Jewish law, passed on 18 April 1939 and not systematically enforced, was a four-percent quota of the numbers of Jews allowed to practice law; Jews were also forbidden to write for non-Jewish publications. The Land Reform Act of February 1940 turned of land owned by 4,943 Jews, more than 40 percent of it arable, over to the State Land Office; the land officially passed to the state in May 1942. The First Aryanization Law was passed in April 1940. Through a process known as "voluntary Aryanization", Jewish business owners could suggest a "qualified Christian candidate" who would assume at least a 51-percent stake in the company. Under the law, 50 businesses out of more than 12,000 were Aryanized and 179 were liquidated. HSĽS radicals and the Slovak State's German backers believed that voluntary Aryanization was too soft on the Jews. Nevertheless, by mid-1940 the position of Jews in the Slovak economy had been largely wiped out.

At the July 1940

At the July 1940 Salzburg Conference

The Salzburg Conference (german: Salzburger Diktat) was a conference between Nazi Germany and the Slovak State, held on 28 July 1940, in Salzburg, Reichsgau Ostmark (present-day Austria). The Germans demanded the expulsion of the ''Nástup'' f ...

, Germany demanded the replacement of several members of the cabinet with reliably pro-German radicals. Ferdinand Ďurčanský

Ferdinand Ďurčanský (18 December 1906 – 15 March 1974) was a Slovak nationalist leader who for a time served with as a minister in the government of the Axis-aligned Slovak State in 1939 and 1940. He was known for spreading virulent antis ...

was replaced as interior minister by Alexander Mach

Alexander Mach (11 October 1902 – 15 October 1980) was a Slovak nationalist politician. Mach was associated with the far right wing of Slovak nationalism and became noted for his strong support of Nazism and Germany.

Early years

Mach joined ...

, who aligned the anti-Jewish policy of the Slovak State with that of Germany. Another result of the Salzburg talks was the appointment of SS officer Dieter Wisliceny

Dieter Wisliceny (13 January 1911 – 4 May 1948) was a member of the ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS) and one of the deputies of Adolf Eichmann, helping to organise and coordinate the wide scale deportations of the Jews across Europe during the Holocaust.

...

as an adviser on Jewish affairs for Slovakia, arriving in August. He aimed to impoverish the Jewish community so it would become a burden on non-Jewish Slovaks, who would then agree to deport them. At Wisliceny's instigation, the Slovak government created the Central Economic Office

Central is an adjective usually referring to being in the center of some place or (mathematical) object.

Central may also refer to:

Directions and generalised locations

* Central Africa, a region in the centre of Africa continent, also known as ...

(ÚHÚ), led by Slovak official and under Tuka's control, in September 1940. The Central Economic Office was tasked with assuming ownership of Jewish-owned property. Jews were required to register their property; their bank accounts (valued at 245 million Ks in August 1941) were frozen, and Jews were allowed to withdraw only 1,000 Ks (later 150 Ks) per week. The 22,000 Jews who worked in salaried employment were targeted: non-Jews had to obtain Central Economic Office permission to employ Jews and pay a fee.

A second Aryanization law was passed in November, mandating the expropriation

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to priv ...

of Jewish property and the Aryanization or liquidation of Jewish businesses. In a corrupt process overseen by Morávek's office, 10,000 Jewish businesses (mostly shops) were liquidated and the remainder – about 2,300 – were Aryanized. Liquidation benefited small Slovak businesses competing with Jewish enterprises, and Aryanization was applied to larger Jewish-owned companies which were acquired by competitors. In many cases, Aryanizers inexpert in business struck deals with former Jewish owners and employees so the Jews would keep working for the company. The Aryanization of businesses did not bring the anticipated revenue into the Slovak treasury, and only 288 of the liquidated businesses produced income for the state by July 1942. The Aryanization and liquidation of businesses was nearly complete by January 1942, resulting in 64,000 of 89,000 Jews losing their means of support. For Jews, Aryanization resulted in disaster as the manufactured Jewish impoverishment was resolved by their deportation in 1942.

Aryanization resulted in an immense financial loss for Slovakia and great destruction of wealth. The state failed to raise substantial funds from the sale of Jewish property and businesses, and most of its gains came from the confiscation of Jewish-owned bank accounts and financial securities. The main beneficiaries of Aryanization were members of Slovak fascist political parties and paramilitary groups, who were eager to acquire Jewish property but had little expertise in running businesses. During the Slovak Republic's existence, the government gained 1,100 million Ks from Aryanization and spent 900–950 million Ks on enforcing anti-Jewish measures. In 1942, it paid the German government another 300 million Ks for the deportation of 58,000 Jews.

Jewish Center

When Wisliceny arrived, all Jewish community organizations were dissolved and the Jews were forced to form the (Jewish Center, ÚŽ, subordinate to the Central Economic Office) in September 1940. The first outside the Reich and German-occupied Poland, the ÚŽ was the only secular Jewish organization allowed to exist in Slovakia; membership was required of all Jews. Leaders of the Jewish community were divided about how to respond to this development. Although some argued that the ÚŽ would be used to implement anti-Jewish measures, more saw participation in the ÚŽ as a way to help their fellow Jews by delaying the implementation of such measures and alleviating poverty. The first leader of the ÚŽ wasHeinrich Schwartz Heinrich may refer to:

People

* Heinrich (given name), a given name (including a list of people with the name)

* Heinrich (surname), a surname (including a list of people with the name)

*Hetty (given name), a given name (including a list of p ...

, who thwarted anti-Jewish orders to the best of his ability: he sabotaged a census of Jews in eastern Slovakia which was intended to justify their removal to the west of the country; Wisliceny had him arrested in April 1941. The Central Economic Office appointed the more cooperative Arpad Sebestyen as Schwartz's replacement. Wisliceny set up a Department for Special Affairs in the ÚŽ to ensure the prompt implementation of Nazi decrees, appointing the collaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to t ...

Karol Hochberg

Karol Hochberg (1911–1944, also Karl or Karel) was a collaborator during the Holocaust, who led the "Department for Special Affairs" within the Ústredňa Židov, the ''Judenrat'' in Bratislava which was created by the Nazis to direct the Jewis ...

(a Viennese Jew) as its director.

Forced labor

Jews serving in the army were segregated into a labor unit in April 1939 and were stripped of their rank at the end of the year. From 1940, male Jews and Romani people were obliged to work for the national defense (generally manual labor on construction projects) for two months every year. All recruits considered Jewish or Romani were allocated to the

Jews serving in the army were segregated into a labor unit in April 1939 and were stripped of their rank at the end of the year. From 1940, male Jews and Romani people were obliged to work for the national defense (generally manual labor on construction projects) for two months every year. All recruits considered Jewish or Romani were allocated to the Sixth Labor Battalion

Sixth is the ordinal form of the number six.

* The Sixth Amendment, to the U.S. Constitution

* A keg of beer, equal to 5 U.S. gallons or barrel

* The fraction

Music

* Sixth interval (music)s:

** major sixth, a musical interval

** minor si ...

, which worked at military construction sites at Sabinov

Sabinov ( la, Сibinium, hu, Kisszeben, german: Zeben, russian: Сабинов) is a small town located in the Prešov Region (north-eastern Slovakia), approximately 20 km from Prešov and 55 km from Košice. The population of Sabinov i ...

, Liptovský Svätý Peter, Láb

Láb is a village and municipality in western Slovakia in Malacky District in the Bratislava region

The Bratislava Region ( sk, Bratislavský kraj, , german: Pressburger/Bratislavaer Landschaftsverband (until 1919), hu, Pozsonyi kerület) i ...

, Svätý Jur

Svätý Jur (; german: Sankt Georgen; he, Yergen; hu, Szentgyörgy; formerly ''Jur pri Bratislave'') is a small historical town northeast of Bratislava, located in the Bratislava Region. The city is situated on the slopes of Little Carpathians m ...

, and Zohor

Zohor is a village and municipality in western Slovakia in Malacky District in the Bratislava Region.

History

The village was first mentioned in 1314 as ''Sahur''.

Famous people

*Albín Brunovský

Albín Brunovský (25 December 1935, Zohor, Cz ...

the following year. Although the Ministry of Defense was pressured by the Ministry of the Interior to release the Jews for deportation in 1942, it refused. The battalion was disbanded in 1943, and the Jewish laborers were sent to work camps.

The first labor centers were established in early 1941 by the ÚŽ as retraining courses for Jews forced into unemployment; 13,612 Jews had applied for the courses by February, far exceeding the programs' capacity. On 4 July, the Slovak government issued a decree conscripting all Jewish men aged 18 to 60 for labor. Although the ÚŽ had to supplement the workers' pay to meet the legal minimum, the labor camps greatly increased the living standard of Jews impoverished by Aryanization. By September, 5,500 Jews were performing manual labor for private companies at about 80 small labor centers, most of which were dissolved in the final months of 1941 as part of the preparation for deportation. Construction began on three larger camps – Sereď

Sereď (; hu, Szered ) is a town in southern Slovakia near Trnava, on the right bank of the Váh River on the Danubian Lowland. It has approximately 15,500 inhabitants.

Geography

Sereď lies at an altitude of above sea level and covers an are ...

, Nováky, and Vyhne

Vyhne ( hu, Vihnye) is a village in the Žiar nad Hronom District, which is part of the Banská Bystrica Region in central Slovakia.

Geography

Vyhne is located in the Štiavnické vrchy mountains, near the historic town of Banská Štiavnica. A n ...

– in September of that year.

Jewish Code

In accordance with Catholic teaching on race, antisemitic laws initially defined Jews by religion rather than ancestry; Jews who were baptized before 1918 were considered Christian. By September 1940, Jews were banned from secondary and higher education and from all non-Jewish schools, and forbidden from owning motor vehicles, sports equipment, or radios. Local authorities had imposed anti-Jewish measures on their own; the head of the Šariš-Zemplín region ordered local Jews to wear a yellow band around their left arm from 5 April 1941, leading to physical attacks against Jews. In mid-1941, as the focus shifted to restricting Jews' civil rights after they had been deprived of their property through Aryanization,

In accordance with Catholic teaching on race, antisemitic laws initially defined Jews by religion rather than ancestry; Jews who were baptized before 1918 were considered Christian. By September 1940, Jews were banned from secondary and higher education and from all non-Jewish schools, and forbidden from owning motor vehicles, sports equipment, or radios. Local authorities had imposed anti-Jewish measures on their own; the head of the Šariš-Zemplín region ordered local Jews to wear a yellow band around their left arm from 5 April 1941, leading to physical attacks against Jews. In mid-1941, as the focus shifted to restricting Jews' civil rights after they had been deprived of their property through Aryanization, Department 14

Department may refer to:

* Departmentalization, division of a larger organization into parts with specific responsibility

Government and military

* Department (administrative division), a geographical and administrative division within a country, ...

of the Ministry of the Interior was formed to enforce anti-Jewish measures.

The Slovak parliament passed the Jewish Code on 9 September 1941, which contained 270 anti-Jewish articles. Based on the Nuremberg Laws

The Nuremberg Laws (german: link=no, Nürnberger Gesetze, ) were antisemitic and Racism, racist laws that were enacted in Nazi Germany on 15 September 1935, at a special meeting of the Reichstag (Nazi Germany), Reichstag convened during ...

, the code defined Jews in terms of ancestry, banned intermarriage, and required that all Jews over six years old wear a yellow star. The Jewish Code excluded Jews from public life, restricting the hours that they were allowed to travel and shop, and barring them from clubs, organizations, and public events. Jews also had to pay a 20-percent tax on all property. Government propaganda boasted that the Jewish Code was the strictest set of anti-Jewish laws in Europe. The president could issue exemptions protecting individual Jews from the law. Employed Jews were initially exempt from some of the code's requirements, such as wearing the star.

The racial definition of Jews was criticized by the Catholic Church, and converts were eventually exempted from some of the requirements. The Hlinka Guard and increased assaults on Jews, engaged in antisemitic demonstrations on a daily basis, and harassed non-Jews judged insufficiently antisemitic. The law enabled the Central Economic Office to force Jews to change their residence. This provision was put into effect on 4 October 1941, when 10,000 of 15,000 Jews in Bratislava (who were not employed or intermarried) were ordered to move to fourteen towns. The relocation was paid for and carried out by the ÚŽ's Department of Special Tasks. Although the Jews were ordered to leave by 31 December, fewer than 7,000 people had moved by March 1942.

Deportations (1942)

Planning

The highest levels of the Slovak government were aware by late 1941 of mass murders of Jews in German-occupied territories. In July 1941, Wisliceny organized a visit by Slovak government officials to several camps run by

The highest levels of the Slovak government were aware by late 1941 of mass murders of Jews in German-occupied territories. In July 1941, Wisliceny organized a visit by Slovak government officials to several camps run by Organization Schmelt

Organization Schmelt was a Nazi SS organization that ran a system of forced-labor camps with mostly Jewish prisoners. It originated in East Upper Silesia, but spread to the Sudetenland and other areas. Many of its camps were later absorbed into ...

, which imprisoned Jews in East Upper Silesia East Upper Silesia (german: Ostoberschlesien) is the easternmost extremity of Silesia, the eastern part of the Upper Silesian region around the city of Katowice (german: Kattowitz).Isabel Heinemann, ''"Rasse, Siedlung, deutsches Blut": das Rasse- u ...

to employ them in forced labor on the Reichsautobahn

The ''Reichsautobahn'' system was the beginning of the German autobahns under Nazi Germany. There had been previous plans for controlled-access highways in Germany under the Weimar Republic, and two had been constructed, but work had yet to st ...

. The visitors understood that Jews in the camps lived under conditions which would eventually cause their deaths. Slovak soldiers participated in the invasions of Poland

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

and the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen nationa ...

; they brought word of the mass shootings of Jews, and participated in at least one of the massacres. Some Slovaks were aware of the 1941 Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre

The Kamianets-Podilskyi massacre was a World War II mass shooting of Jews carried out in the opening stages of Operation Barbarossa, by the German Police Battalion 320 along with Friedrich Jeckeln's ''Einsatzgruppen'', the Hungarian soldiers, an ...

, in which 23,600 Jews, many of them deported from Hungary, were shot in western Ukraine. Defense minister Ferdinand Čatloš

Ferdinand Čatloš (October 7, 1895 – December 16, 1972), born Csatlós Nándor, was a Slovak military officer and politician. Throughout his short career in the administration of the Slovak Republic he held the post of Minister of Defence. He wa ...

and General Jozef Turanec __NOTOC__

Jozef Turanec (7 March 1892 Sučany – 9 March 1957, Leopoldov) was a Slovak General during World War II. He was also a recipient of the Knight's Cross of the Iron Cross of Nazi Germany. Jozef Turanec served as a general in the Slovak In ...

reported massacres in Zhytomyr

Zhytomyr ( uk, Жито́мир, translit=Zhytomyr ; russian: Жито́мир, Zhitomir ; pl, Żytomierz ; yi, זשיטאָמיר, Zhitomir; german: Schytomyr ) is a city in the north of the western half of Ukraine. It is the administrative ...

to Tiso by February 1942. Both bishop Karol Kmeťko

Karol Kmeťko (December 12, 1875 – December 22, 1948) was the Roman Catholic Bishop of Nitra in Slovakia (1920-1948) and personal archbishop (from 1944).

Early life and ordination

Born in Veľké Držkovce, in the Trencsén County of the Ki ...

and papal Giuseppe Burzio Giuseppe Burzio (1901-1966), born Cambiano, Italy, was a Vatican diplomat and Roman Catholic Archbishop

In Christian denominations, an archbishop is a bishop of higher rank or office. In most cases, such as the Catholic Church, there are man ...

confronted the president with reliable reports of the mass murder of Jewish civilians in the Ukraine. Slovak newspapers wrote many articles attempting to refute rumors that deported Jews were mistreated, pointing to general knowledge by mid-1942 that deported Jews were no longer alive.

In mid-1941, the Germans demanded (per previous agreements) another 20,000 Slovak laborers to work in Germany. Slovakia refused to send gentile Slovaks and instead offered an equal number of Jewish workers, although it did not want to be burdened with their families. A letter sent on 15 October 1941 indicates that plans were being made for the mass murder of Jews in the Lublin District

Lublin District (german: Distrikt Lublin) was one of the first four Nazi districts of the General Governorate region of German-occupied Poland during World War II, along with Warsaw District, Radom District, and Kraków District. On the south ...

of the General Government to make room for deported Jews from Slovakia and Germany. In late October, Tiso, Tuka, Mach, and Čatloš visited the Wolf's Lair

The ''Wolf's Lair'' (german: Wolfsschanze; pl, Wilczy Szaniec) served as Adolf Hitler's first Eastern Front military headquarters in World War II.

The headquarters was located in the Masurian woods, near the small village of Görlitz in Ostp ...

(near Rastenburg, East Prussia

East Prussia ; german: Ostpreißen, label= Low Prussian; pl, Prusy Wschodnie; lt, Rytų Prūsija was a province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1773 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1 ...

) and met with Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

. No record survives of this meeting, at which the deportation of Jews from Slovakia was probably first discussed, leading to historiographical debate over who proposed the idea. Even if the Germans made the offer, the Slovak decision was not motivated by German pressure. In November 1941, the Slovak government permitted the German government to deport the 659 Slovak Jews living in the Reich and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia

The Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia; cs, Protektorát Čechy a Morava; its territory was called by the Nazis ("the rest of Czechia"). was a partially annexed territory of Nazi Germany established on 16 March 1939 following the German oc ...

to German-occupied Poland, with the proviso that their confiscated property be passed to Slovakia. This was the first step towards deporting Jews from Slovakia, which Tuka discussed with Wisliceny in early 1942. As indicated by a cable from the German ambassador to Slovakia, Hanns Ludin

Hanns Elard Ludin (10 June 1905, in Freiburg – 9 December 1947, in Bratislava) was a German diplomat.

Born in Freiburg to Friedrich and Johanna Ludin, Ludin began his Nazi affiliation in 1930 by joining the party, and was arrested for his ...

, the Slovaks responded "with enthusiasm" to the idea.

Tuka presented the deportation proposals to the government on 3 March, and they were debated in parliament three days later. On 15 May, parliament approved Decree 68/1942

A decree is a legal proclamation, usually issued by a head of state (such as the president of a republic or a monarch), according to certain procedures (usually established in a constitution). It has the force of law. The particular term used ...

, which retroactively legalized the deportation of Jews, authorized the removal of their citizenship, and regulated exemptions. Opposition centered on economic, moral, and legal obstacles, but, as Mach later stated, "every egislatorwho has spoken on this issue has said that we should get rid of Jews". The official Catholic representative and Bishop of Spiš

Spiš (Latin: ''Cips/Zepus/Scepus/Scepusia'', german: Zips, hu, Szepesség/Szepes, pl, Spisz) is a region in north-eastern Slovakia, with a very small area in south-eastern Poland (14 villages). Spiš is an informal designation of the territory ...

, Ján Vojtaššák

Ján Vojtaššák (14 November 18774 August 1965)

at the official website ...

, only requested separate settlements in Poland for Jews who had converted to Christianity. The Slovaks agreed to pay 500 at the official website ...

Reichsmark

The (; sign: ℛℳ; abbreviation: RM) was the currency of Germany from 1924 until 20 June 1948 in West Germany, where it was replaced with the , and until 23 June 1948 in East Germany, where it was replaced by the East German mark. The Reich ...

s per Jew deported (ostensibly to cover shelter, food, retraining and housing) and an additional fee to the for transport. The 500 Reichsmark fee was equivalent to about USD$125 at the time, or $ today. The Germans promised in exchange that the Jews would never return, and Slovakia could keep all confiscated property. Except for the Independent State of Croatia

The Independent State of Croatia ( sh, Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH; german: Unabhängiger Staat Kroatien; it, Stato indipendente di Croazia) was a World War II-era puppet state of Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy. It was established in p ...

(which paid 30 Reichsmarks per person), Slovakia was the only country which paid to deport its Jewish population. According to historian Donald Bloxham

Donald Bloxham FRHistS is a Professor of Modern History, specialising in genocide, war crimes and other mass atrocities studies. He is the editor of the ''Journal of Holocaust Education''.

He completed his undergraduate studies at Keele and po ...

, "the fact that the Tiso regime let Germany do the dirty work should not conceal its desire to “cleanse” the economy and ultimately the society in the name of 'Christianization.

First phase

The original deportation plan, approved in February 1942, entailed the deportation of 7,000 women to Auschwitz and 13,000 men to

The original deportation plan, approved in February 1942, entailed the deportation of 7,000 women to Auschwitz and 13,000 men to Majdanek

Majdanek (or Lublin) was a Nazi concentration and extermination camp built and operated by the SS on the outskirts of the city of Lublin during the German occupation of Poland in World War II. It had seven gas chambers, two wooden gallows, a ...

as forced laborers. Department 14 organized the deportations, while the Slovak Transport Ministry provided the cattle cars

In railroad terminology, a stock car or cattle car is a type of rolling stock used for carrying livestock (not carcasses) to market. A traditional stock car resembles a boxcar with louvered instead of solid car sides (and sometimes ends) for the p ...

. Lists of those to be deported were drawn up by Department 14 based on statistical data provided by the Jewish Center's Department for Special Tasks. At the border station in Zwardon, the Hlinka Guard handed the transports off to the German . Slovak officials promised that deportees would be allowed to return home after a fixed period, and many Jews initially believed that it was better to report for deportation rather than risk reprisals against their families. On 25 March 1942, the first transport departed from Poprad transit camp

Poprad-Tatry railway station ( sk, Železničná stanica Poprad-Tatry) is a break-of-gauge junction station serving the city of Poprad, in the Prešov Region, northeastern Slovakia.

Opened in 1871, the station forms part of the standard gauge Ko ...

for Auschwitz with 1,000 unmarried Jewish women between the ages of 16 and 45. During the first wave of deportations (which ended on 2 April), 6,000 young, single Jews were deported to Auschwitz and Majdanek.

Members of the Hlinka Guard, the , and the gendarmerie

Wrong info! -->

A gendarmerie () is a military force with law enforcement duties among the civilian population. The term ''gendarme'' () is derived from the medieval French expression ', which translates to " men-at-arms" (literally, ...

were in charge of rounding up the Jews, guarding the transit centers, and eventually forcing them into train cars for deportation. A German officer was stationed at each of the concentration centers. Official exemptions were supposed to keep certain Jews from being deported, but local authorities sometimes deported exemption-holders. The victims were given only four hours' warning, to prevent them from escaping. Beatings and forcible shaving were commonplace, as was subjecting Jews to invasive searches to uncover hidden valuables. Although some guards and local officials accepted bribes to keep Jews off the transports, the victim would typically be deported on the next train. Others took advantage of their power to rape Jewish women. Jews were only allowed to bring of personal items with them, but even this was frequently stolen.

Family transports

Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( ; ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a high-ranking German SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust.

He was chief of the Reich Security Main Office (inc ...

, the head of the Reich Security Main Office

The Reich Security Main Office (german: Reichssicherheitshauptamt or RSHA) was an organization under Heinrich Himmler in his dual capacity as ''Chef der Deutschen Polizei'' (Chief of German Police) and '' Reichsführer-SS'', the head of the Nazi ...

, visited Bratislava on 10 April, and he and Tuka agreed that further deportations would target whole families and eventually remove all Jews from Slovakia. The family transports began on 11 April, and took their victims to the Lublin District. During the first half of June 1942 ten transports stopped briefly at Majdanek, where able-bodied men were selected for labor; the trains continued to Sobibor extermination camp

Sobibor (, Polish: ) was an extermination camp built and operated by Nazi Germany as part of Operation Reinhard. It was located in the forest near the village of Żłobek Duży in the General Government region of German-occupied Poland.

As a ...

, where the remaining victims were murdered. Most of the trains brought their victims (30,000 in total) to ghettos whose inhabitants had been recently deported to the Bełżec or Sobibor extermination camps

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The ...

. Some groups stayed only briefly before they were deported again to the extermination camps, while other groups remained in the ghettos for months or years. Some of the deportees ended up in the forced-labor camps in the Lublin District (such as Poniatowa, Dęblin–Irena, and Krychów

Krychów is a village neighbourhood ( pl, kolonia) in the administrative district of Gmina Hańsk, within Włodawa County, Lublin Voivodeship, in eastern Poland. In 1975–98 the settlement belonged administratively to Chełm Voivodeship.

World ...

). Unusually, the deportees in the Lublin District were quickly able to establish contact with the Jews remaining in Slovakia, which led to extensive aid efforts. The fate of the Jews deported from Slovakia was ultimately "sealed within the framework of Operation Reinhard

or ''Einsatz Reinhard''

, location = Occupied Poland

, date = October 1941 – November 1943

, incident_type = Mass deportations to extermination camps

, perpetrators = Odilo Globočnik, Hermann Höfle, Richard Thomalla, Erw ...

" along with that of the Polish Jews

The history of the Jews in Poland dates back at least 1,000 years. For centuries, Poland was home to the largest and most significant Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. Poland was a principal center of Jewish culture, because of the lon ...

, in the words of Yehoshua Büchler.

Transports went to Auschwitz after mid-June, where a minority of the victims were selected for labor and the remainder were killed in the

Transports went to Auschwitz after mid-June, where a minority of the victims were selected for labor and the remainder were killed in the gas chambers

A gas chamber is an apparatus for killing humans or other animals with gas, consisting of a sealed chamber into which a poisonous or asphyxiant gas is introduced. Poisonous agents used include hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide.

History ...

. This occurred for nine transports, the last of which arrived on 21 October 1942. From 1 August to 18 September, no transports departed; most of the Jews not exempt from deportation had already been deported or had fled to Hungary. In mid-August, Tiso gave a speech in Holič in which he described Jews as the "eternal enemy" and justified the deportations according to Christian ethics

Christian ethics, also known as moral theology, is a multi-faceted ethical system: it is a virtue ethic which focuses on building moral character, and a deontological ethic which emphasizes duty. It also incorporates natural law ethics, whic ...

. At this time of the speech, the Slovak government had accurate information on the mass murder of the deportees from Slovakia; an official request to inspect the camps where Slovak Jews were held in Poland was denied by Eichmann. Three more transports occurred in September and October 1942 before ceasing until 1944. By the end of 1942, only 500 or 600 Slovak Jews were still alive at Auschwitz. Thousands of surviving Slovak Jews in the Lublin District were shot on 3–4 November 1943 during Operation Harvest Festival

Operation Harvest Festival (german: Aktion Erntefest) was the murder of up to 43,000 Jews at the Majdanek, Poniatowa and Trawniki concentration camps by the SS, the Order Police battalions, and the Ukrainian '' Sonderdienst'' on 3–4 N ...

.

Between 25 March and 20 October 1942, almost 58,000 Jews (two-thirds of the population) were deported. The exact number is unknown due to discrepancies in the sources. The deportations disproportionately affected poorer Jews from eastern Slovakia. Although the Šariš-Zemplín region in eastern Slovakia lost 85 to 90 percent of its Jewish population, Žilina reported that almost half of its Jews remained after the deportation. The deportees were held briefly in five camps in Slovakia before deportation; 26,384 from Žilina, 7,500 from Patrónka, 7,000 from Poprad, 4,463 from Sereď, and 4,000 to 5,000 from Nováky. Nineteen trains went to Auschwitz, and another thirty-eight went to ghettos and concentration and extermination camps in the Lublin District. Only a few hundred survived the war, most at Auschwitz; almost no one survived in Lublin District.

Opposition, exemption, and evasion

TheHoly See

The Holy See ( lat, Sancta Sedes, ; it, Santa Sede ), also called the See of Rome, Petrine See or Apostolic See, is the jurisdiction of the Pope in his role as the bishop of Rome. It includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of R ...

opposed deportation, fearing that such actions from a Catholic government would discredit the church. Domenico Tardini

Domenico Tardini (29 February 1888 – 30 July 1961) was a longtime aide to Pope Pius XII in the Secretariat of State. Pope John XXIII named him Cardinal Secretary of State and, in this position the most prominent member of the Roman Curia i ...

, Vatican Undersecretary of State, wrote in a private memo: "Everyone understands that the Holy See cannot stop Hitler. But who can understand that it does not know how to rein in a priest?" According to a Security Service (SD) report, Burzio threatened Tiso with an interdict

In Catholic canon law, an interdict () is an ecclesiastical censure, or ban that prohibits persons, certain active Church individuals or groups from participating in certain rites, or that the rites and services of the church are banished from ...

. Slovak bishops were equivocal, endorsing Jewish deicide

Jewish deicide is the notion that the Jews as a people were collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus. A Biblical justification for the charge of Jewish deicide is derived from Matthew 27:24–25. Some rabbinical authorities, such as Ma ...

and other antisemitic myths while urging Catholics to treat Jews humanely. The Catholic Church ultimately chose not to discipline any of the Slovak Catholics who were complicit in the regime's actions. Officials from the ÚŽ and several of the most influential Slovak rabbis sent petitions to Tiso, but he did not reply. Ludin reported that the deportations were "very unpopular", but few Slovaks took action against them. By March 1942, the Working Group

A working group, or working party, is a group of experts working together to achieve specified goals. The groups are domain-specific and focus on discussion or activity around a specific subject area. The term can sometimes refer to an interdis ...

(an underground organization which operated under the auspices of the ÚŽ) had formed to oppose the deportations. Its leaders, Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in J ...

organizer Gisi Fleischmann and Orthodox rabbi Michael Dov Weissmandl

Michael Dov Weissmandl ( yi, מיכאל בער ווייסמאנדל) (25 October 190329 November 1957) was an Orthodox rabbi of the Oberlander Jews of present-day western Slovakia. Along with Gisi Fleischmann he was the leader of the Bratislav ...

, bribed Anton Vašek

Anton Vašek (1905–1946) was the head of Department 14 in the Slovak State's Central Economic Office. He is known for accepting bribes in exchange for reducing deportation of Jews from Slovakia.

Life

Vašek attended law school. One of his classm ...

, head of Department 14, and Wisliceny. It is unknown if the group's efforts had any connection with the halting of deportations.

Many Jews learned about the fate awaiting them during the first half of 1942, from sources such as letters from deported Jews or escapees. Around 5,000 to 6,000 Jews fled to Hungary to avoid the deportations, many by paying bribes or with help from paid smugglers and the Zionist youth movement

A Zionist youth movement ( he, תנועות הנוער היהודיות הציוניות ''tnuot hanoar hayehudiot hatsioniot'') is an organization formed for Jewish children and adolescents for educational, social, and ideological development, in ...

Hashomer Hatzair

Hashomer Hatzair ( he, הַשׁוֹמֵר הַצָעִיר, , ''The Young Guard'') is a Labor Zionist, secular Jewish youth movement founded in 1913 in the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, Austria-Hungary, and it was also the name of the gro ...

; about one third of those who fled to Hungary survived the war. Many owners of Aryanized businesses applied for work exemptions for the Jewish former owners. In some cases this was a fictitious Aryanization; other Aryanizers, motivated by profit, kept the Jewish former owners around for their skills. About 2,000 Jews had false papers identifying themselves as Aryans. Some Christian clergy baptized Jews, even those who were not sincere converts. Although conversion after 1939 did not exempt Jews from deportation, being baptized made it easier to obtain other exemptions and some clergy edited records to predate baptisms.