Apartheid ( ,

especially South African English

South African English (SAfE, SAfEn, SAE, en-ZA) is the List of dialects of English, set of English language dialects native to South Africans.

History

British Empire, British settlers first arrived in the South African region in 1795, ...

: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised

racial segregation

Racial segregation is the separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Segregation can involve the spatial separation of the races, and mandatory use of different institutions, ...

that existed in

South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the Southern Africa, southernmost country in Africa. Its Provinces of South Africa, nine provinces are bounded to the south by of coastline that stretches along the Atlantic O ...

and

South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

(now

Namibia

Namibia, officially the Republic of Namibia, is a country on the west coast of Southern Africa. Its borders include the Atlantic Ocean to the west, Angola and Zambia to the north, Botswana to the east and South Africa to the south; in the no ...

) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an authoritarian political culture based on ''

baasskap'' ( 'boss-ship' or 'boss-hood'), which ensured that South Africa was dominated politically, socially, and economically by the nation's minority

white population.

Under this

minoritarian system, white citizens held the highest status, followed by

Indians,

Coloureds and

black Africans, in that order.

The economic legacy and social effects of apartheid continue to the present day, particularly

inequality.

Broadly speaking, apartheid was delineated into ''petty apartheid'', which entailed the segregation of public facilities and social events, and ''grand apartheid'', which strictly separated housing and

employment opportunities by race.

The first apartheid law was the

Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act, 1949, followed closely by the

Immorality Amendment Act of 1950, which made it illegal for most South African citizens to

marry or pursue sexual relationships across racial lines.

The

Population Registration Act, 1950 classified all South Africans into one of four racial groups based on appearance, known ancestry, socioeconomic status, and cultural lifestyle: "Black", "White", "Coloured", and "Indian", the last two of which included several sub-classifications. Places of residence were determined by racial classification.

[ Between 1960 and 1983, 3.5 million black Africans were removed from their homes and forced into segregated neighbourhoods as a result of apartheid legislation, in some of the largest mass evictions in modern history.]bantustan

A Bantustan (also known as a Bantu peoples, Bantu homeland, a Black people, black homeland, a Khoisan, black state or simply known as a homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party (South Africa), National Party administration of the ...

s'', four of which became nominally independent states.[ The government announced that relocated persons would lose their South African citizenship as they were absorbed into the bantustans.]United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

and brought about extensive international sanctions

International sanctions are political and economic decisions that are part of diplomatic efforts by countries, multilateral or regional organizations against states or organizations either to protect national security interests, or to protect i ...

, including arms embargo

An arms embargo is a restriction or a set of sanctions that applies either solely to weaponry or also to "dual-use technology." An arms embargo may serve one or more purposes:

* to signal disapproval of the behavior of a certain actor

* to maintain ...

es and economic sanctions

Economic sanctions or embargoes are Commerce, commercial and Finance, financial penalties applied by states or institutions against states, groups, or individuals. Economic sanctions are a form of Coercion (international relations), coercion tha ...

on South Africa.internal resistance to apartheid

Several independent sectors of South African society opposed apartheid through various means, including social movements, passive resistance, and guerrilla warfare. Mass action against the ruling National Party (South Africa), National Party (N ...

became increasingly militant, prompting brutal crackdowns by the National Party ruling government and protracted sectarian violence that left thousands dead or in detention.Truth and Reconciliation Commission

A truth commission, also known as a truth and reconciliation commission or truth and justice commission, is an official body tasked with discovering and revealing past wrongdoing by a government (or, depending on the circumstances, non-state ac ...

found that there were 21,000 deaths from political violence, with 7,000 deaths between 1948 and 1989, and 14,000 deaths and 22,000 injuries in the transition period between 1990 and 1994. Some reforms of the apartheid system were undertaken, including allowing for Indian and Coloured political representation in parliament, but these measures failed to appease most activist groups.African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC), the leading anti-apartheid political movement, for ending segregation and introducing majority rule.[ In 1990, prominent ANC figures, such as ]Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

, were released from prison. Apartheid legislation was repealed on 17 June 1991,

Precursors

''Apartheid'' is an Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

word meaning "separateness", or "the state of being apart", literally " apart- hood" (from the Afrikaans suffix ''-heid''). Its first recorded use was in 1929.Dutch East India Company

The United East India Company ( ; VOC ), commonly known as the Dutch East India Company, was a chartered company, chartered trading company and one of the first joint-stock companies in the world. Established on 20 March 1602 by the States Ge ...

's establishment of a trading post in the Cape of Good Hope

The Cape of Good Hope ( ) is a rocky headland on the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic coast of the Cape Peninsula in South Africa.

A List of common misconceptions#Geography, common misconception is that the Cape of Good Hope is the southern tip of Afri ...

in 1652, which eventually expanded into the Dutch Cape Colony. The company began the Khoikhoi–Dutch Wars in which it displaced the local Khoikhoi people, replaced them with farms worked by White settlers, and imported Black slaves from across the Dutch Empire. In the days of slavery

Slavery is the ownership of a person as property, especially in regards to their labour. Slavery typically involves compulsory work, with the slave's location of work and residence dictated by the party that holds them in bondage. Enslavemen ...

, slaves required passes to travel away from their masters.

In 1797, the '' Landdrost'' and ''Heemraden'', local officials, of Swellendam and Graaff-Reinet extended pass laws beyond slaves and ordained that all Khoikhoi (designated as ''Hottentots'') moving about the country for any purpose should carry passes.French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

The French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars (sometimes called the Great French War or the Wars of the Revolution and the Empire) were a series of conflicts between the French and several European monarchies between 1792 and 1815. They encompas ...

, the British Empire

The British Empire comprised the dominions, Crown colony, colonies, protectorates, League of Nations mandate, mandates, and other Dependent territory, territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It bega ...

captured and annexed the Dutch Cape Colony. Under the 1806 Cape Articles of Capitulation the new British colonial rulers were required to respect previous legislation enacted under Roman-Dutch law

Roman-Dutch law ( Dutch: ''Rooms-Hollands recht'', Afrikaans: ''Romeins-Hollandse reg'') is an uncodified, scholarship-driven, and judge-made legal system based on Roman law as applied in the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries. As such, ...

,English Common Law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures. The judiciary is independent, and legal principles like fairness, equality bef ...

and a high degree of legislative autonomy. The governors and assemblies that governed the legal process in the various colonies of South Africa were launched on a different and independent legislative path from the rest of the British Empire.

The United Kingdom's Slavery Abolition Act 1833

The Slavery Abolition Act 1833 ( 3 & 4 Will. 4. c. 73) was an act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, which abolished slavery in the British Empire by way of compensated emancipation. The act was legislated by Whig Prime Minister Charl ...

provided for the gradual abolition of slavery in most parts of the British Empire. The trade of slaves was made illegal throughout the British Empire by 1837, with Nigeria and Bahrain being the last British territories to abolish slavery. The act overrode the Cape Articles of Capitulation. To comply with the act, the South African legislation was expanded to include Ordinance 1 in 1835, which effectively changed the status of slaves to indentured labourers. This was followed by Ordinance 3 in 1848, which introduced an indenture system for Xhosa that was little different from slavery.

The various South African colonies passed legislation throughout the rest of the 19th century to limit the freedom of unskilled workers, to increase the restrictions on indentured workers and to regulate the relations between the races. The discoveries of diamonds and gold in South Africa also raised racial inequality between White people and Black people.

In the Cape Colony

The Cape Colony (), also known as the Cape of Good Hope, was a British Empire, British colony in present-day South Africa named after the Cape of Good Hope. It existed from 1795 to 1802, and again from 1806 to 1910, when it united with three ...

, which previously had a liberal and multi-racial constitution and a system of Cape Qualified Franchise open to men of all races, the Franchise and Ballot Act of 1892 raised the property franchise qualification and added an educational element, disenfranchising a disproportionate number of the Cape's non-White voters, and the Glen Grey Act of 1894 instigated by the government of Prime Minister Cecil Rhodes

Cecil John Rhodes ( ; 5 July 185326 March 1902) was an English-South African mining magnate and politician in southern Africa who served as Prime Minister of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896. He and his British South Africa Company founded th ...

limited the amount of land Africans could hold. Similarly, in Natal, the Natal Legislative Assembly Bill of 1894 deprived Indians of the right to vote. In 1896 the South African Republic

The South African Republic (, abbreviated ZAR; ), also known as the Transvaal Republic, was an independent Boer republics, Boer republic in Southern Africa which existed from 1852 to 1902, when it was annexed into the British Empire as a result ...

brought in two pass laws requiring Africans to carry a badge. Only those employed by a master were permitted to remain on the Rand, and those entering a "labour district" needed a special pass. During the Second Boer War

The Second Boer War (, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, Transvaal War, Anglo–Boer War, or South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer republics (the South African Republic and ...

, the British Empire cited racial exploitation of Blacks as a cause for its war against the Boer republics. However, the peace negotiations for the Treaty of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided ...

demanded "the just predominance of the white race" in South Africa as a precondition for the Boer republics unifying with the British Empire.

In 1905 the General Pass Regulations Act denied Black people the vote and limited them to fixed areas, and in 1906 the Asiatic Registration Act of the Transvaal Colony

The Transvaal Colony () was the name used to refer to the Transvaal region during the period of direct British rule and military occupation between the end of the Second Boer War in 1902 when the South African Republic was dissolved, and the ...

required all Indians to register and carry passes. Beginning in 1906 the South African Native Affairs Commission under Godfrey Lagden began implementing a more openly segregationist policy towards non-Whites. The latter was repealed by the British government but re-enacted in 1908. In 1910, the Union of South Africa

The Union of South Africa (; , ) was the historical predecessor to the present-day South Africa, Republic of South Africa. It came into existence on 31 May 1910 with the unification of the British Cape Colony, Cape, Colony of Natal, Natal, Tra ...

was created as a self-governing dominion

A dominion was any of several largely self-governance, self-governing countries of the British Empire, once known collectively as the ''British Commonwealth of Nations''. Progressing from colonies, their degrees of self-governing colony, colon ...

, which continued the legislative program: the South Africa Act (1910) enfranchised White people, giving them complete political control over all other racial groups while removing the right of Black people to sit in parliament;[Leach, Graham (1986). ''South Africa: no easy path to peace.'' Routledge. p. 68.] the Native Land Act (1913) prevented Black people, except those in the Cape, from buying land outside "reserves";British Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

rather than paramount chief

A paramount chief is the English-language designation for a king or queen or the highest-level political leader in a regional or local polity or country administered politically with a Chiefdom, chief-based system. This term is used occasionally ...

s the supreme head over all African affairs; the Native Land and Trust Act (1936) complemented the 1913 Native Land Act and, in the same year, the Representation of Natives Act removed previous Black voters from the Cape voters' roll and allowed them to elect three Whites to Parliament.

The United Party government of Jan Smuts began to move away from the rigid enforcement of segregationist laws during World War II, but faced growing opposition from Afrikaner nationalists who wanted stricter segregation. Post-war, one of the first pieces of segregating legislation enacted by Smuts' government was the Asiatic Land Tenure Bill (1946), which banned land sales to Indians and Indian descendent South Africans. The same year, the government established the Fagan Commission. Amid fears integration would eventually lead to racial assimilation, the Opposition Herenigde Nasionale Party (HNP) established the Sauer Commission to investigate the effects of the United Party's policies. The commission concluded that integration would bring about a "loss of personality" for all racial groups. The HNP incorporated the commission's findings into its campaign platform for the 1948 South African general election, which it won.

Institution

1948 election

South Africa had allowed social custom and law to govern the consideration of multiracial affairs and of the allocation, in racial terms, of access to economic, social, and political status.

South Africa had allowed social custom and law to govern the consideration of multiracial affairs and of the allocation, in racial terms, of access to economic, social, and political status.World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

attracted black migrant workers in large numbers to chief industrial centres, where they compensated for the wartime shortage of white labour. However, this escalated rate of black urbanisation went unrecognised by the South African government, which failed to accommodate the influx with parallel expansion in housing or social services.self-determination

Self-determination refers to a people's right to form its own political entity, and internal self-determination is the right to representative government with full suffrage.

Self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international la ...

and popular freedoms enshrined in such statements as the Atlantic Charter. Black political organisations and leaders such as Alfred Xuma, James Mpanza, the African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

, and the Council of Non-European Trade Unions began demanding political rights, land reform, and the right to unionise.

Whites reacted negatively to the changes, allowing the Herenigde Nasionale Party (or simply the National Party) to convince a large segment of the voting bloc

A voting bloc is a group of voting, voters that are strongly motivated by a specific common concern or group of concerns to the point that such specific concerns tend to dominate their voting patterns, causing them to vote together in elections.

...

that the impotence of the United Party in curtailing the evolving position of nonwhites indicated that the organisation had fallen under the influence of Western liberals.Afrikaners

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch people, Dutch Settler colonialism, settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in Free Burghers in the Dutch Cape Colony, 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. '' ...

resented what they perceived as disempowerment by an underpaid black workforce and the superior economic power and prosperity of white English speakers. Smuts, as a strong advocate of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, lost domestic support when South Africa was criticised for its colour bar and the continued mandate of South West Africa

South West Africa was a territory under Union of South Africa, South African administration from 1915 to 1990. Renamed ''Namibia'' by the United Nations in 1968, Independence of Namibia, it became independent under this name on 21 March 1990. ...

by other UN member states.[O'Meara, Dan. ''Forty Lost Years : The National Party and the Politics of the South African State'', 1948–1994. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1996.]

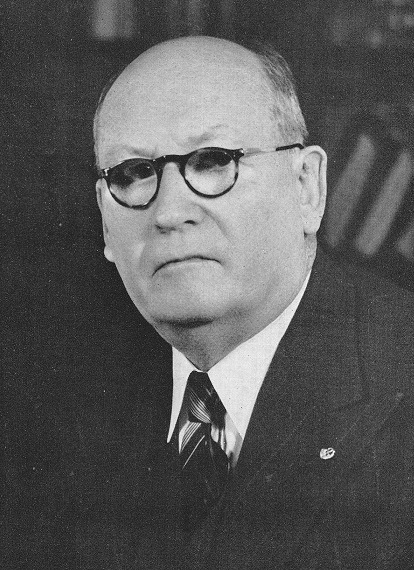

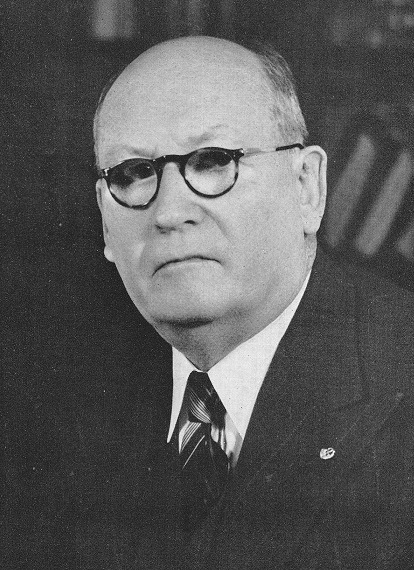

Afrikaner nationalists proclaimed that they offered the voters a new policy to ensure continued white domination.[M. Meredith, ''In the Name of Apartheid'', London: Hamish Hamilton, 1988, ] This policy was initially expounded from a theory drafted by Hendrik Verwoerd and was presented to the National Party by the Sauer Commission.Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

also stirred up discontent, while the nationalists promised to purge the state and public service of communist sympathisers.Pretoria

Pretoria ( ; ) is the Capital of South Africa, administrative capital of South Africa, serving as the seat of the Executive (government), executive branch of government, and as the host to all foreign embassies to the country.

Pretoria strad ...

. Barring the predominantly English-speaking landowner electorate of the Natal, the United Party was defeated in almost every rural district. Its urban losses in the nation's most populous province, the Transvaal, proved equally devastating.voting system

An electoral or voting system is a set of rules used to determine the results of an election. Electoral systems are used in politics to elect governments, while non-political elections may take place in business, nonprofit organizations and inf ...

was disproportionately weighted in favour of rural constituencies and the Transvaal in particular, the 1948 election catapulted the Herenigde Nasionale Party from a small minority party to a commanding position with an eight-vote parliamentary lead.

Legislation

NP leaders argued that South Africa did not comprise a single nation, but was made up of four distinct racial groups: white, black, Coloured and Indian. Such groups were split into 13 nations or racial federations. White people encompassed the English and Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

language groups; the black populace was divided into ten such groups.

The state passed laws that paved the way for "grand apartheid", which was centred on separating races on a large scale, by compelling people to live in separate places defined by race. This strategy was in part adopted from "left-over" British rule that separated different racial groups after they took control of the Boer republics in the Anglo-Boer war. This created the black-only "township

A township is a form of human settlement or administrative subdivision. Its exact definition varies among countries.

Although the term is occasionally associated with an urban area, this tends to be an exception to the rule. In Australia, Canad ...

s" or "locations", where blacks were relocated to their own towns. As the NP government's minister of native affairs from 1950, Hendrik Verwoerd had a significant role in crafting such laws, which led to him being regarded as the 'Architect of Apartheid'.[Alistair Boddy-Evans]

African History: Apartheid Legislation in South Africa

, About.com

Dotdash Meredith (formerly The Mining Company, About.com and Dotdash) is an American digital media company based in New York City. The company publishes online articles and videos about various subjects across categories including health, hom ...

. Retrieved 5 June 2007.

The first grand apartheid law was the Population Registration Act of 1950, which formalised racial classification and introduced an identity card for all persons over the age of 18, specifying their racial group. Official teams or boards were established to come to a conclusion on those people whose race was unclear. This caused difficulty, especially for Coloured people, separating their families when members were allocated different races.

The second pillar of grand apartheid was the Group Areas Act of 1950. Until then, most settlements had people of different races living side by side. This Act put an end to diverse areas and determined where one lived according to race. Each race was allotted its own area, which was used in later years as a basis of forced removal. The Prevention of Illegal Squatting Act of 1951 allowed the government to demolish black shanty town

A shanty town, squatter area, squatter settlement, or squatter camp is a settlement of improvised buildings known as shanties or shacks, typically made of materials such as mud and wood, or from cheap building materials such as corrugated iron s ...

slums and forced white employers to pay for the construction of housing for those black workers who were permitted to reside in cities otherwise reserved for whites. The Native Laws Amendment Act, 1952 centralised and tightened pass laws so that blacks could not stay in urban areas longer than 72 hours without a permit.

The Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act of 1949 prohibited marriage between persons of different races, and the Immorality Act of 1950 made sexual relations between whites and other races a criminal offence

In ordinary language, a crime is an unlawful act punishable by a state or other authority. The term ''crime'' does not, in modern criminal law, have any simple and universally accepted definition,Farmer, Lindsay: "Crime, definitions of", in Ca ...

.

Under the Reservation of Separate Amenities Act of 1953, municipal grounds could be reserved for a particular race, creating, among other things, separate beaches, buses, hospitals, schools and universities. Signboards such as "whites only" applied to public areas, even including park benches. Black South Africans were provided with services greatly inferior to those of whites, and, to a lesser extent, to those of Indian and Coloured people.Communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

. The act defined Communism and its aims so sweepingly that anyone who opposed government policy risked being labelled as a Communist. Since the law specifically stated that Communism aimed to disrupt racial harmony, it was frequently used to gag opposition to apartheid. Disorderly gatherings were banned, as were certain organisations that were deemed threatening to the government. It also empowered the Ministry of Justice to impose banning orders.African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC), the South African Indian Congress (SAIC), and the South African Congress of Trade Unions (SACTU). After the release of the Freedom Charter, 156 leaders of these groups were charged in the 1956 Treason Trial. It established censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governmen ...

of film, literature, and the media under the Customs and Excise Act 1955 and the Official Secrets Act 1956. The same year, the Native Administration Act 1956 allowed the government to banish blacks.bantustan

A Bantustan (also known as a Bantu peoples, Bantu homeland, a Black people, black homeland, a Khoisan, black state or simply known as a homeland; ) was a territory that the National Party (South Africa), National Party administration of the ...

s. The Bantu Education Act, 1953 established a separate education system for blacks emphasizing African culture and vocational training

Vocational education is education that prepares people for a Skilled worker, skilled craft. Vocational education can also be seen as that type of education given to an individual to prepare that individual to be gainfully employed or self em ...

under the Ministry of Native Affairs and defunded most mission schools. The Promotion of Black Self-Government Act of 1959 entrenched the NP policy of nominally independent "homelands" for blacks. So-called "self–governing Bantu units" were proposed, which would have devolved administrative powers, with the promise later of autonomy

In developmental psychology and moral, political, and bioethical philosophy, autonomy is the capacity to make an informed, uncoerced decision. Autonomous organizations or institutions are independent or self-governing. Autonomy can also be ...

and self-government. It also abolished the seats of white representatives of black South Africans and removed from the rolls the few blacks still qualified to vote. The Bantu Investment Corporation Act of 1959 set up a mechanism to transfer capital to the homelands to create employment there. Legislation of 1967 allowed the government to stop industrial development in "white" cities and redirect such development to the "homelands". The Black Homeland Citizenship Act of 1970 marked a new phase in the Bantustan strategy. It changed the status of blacks to citizens of one of the ten autonomous territories. The aim was to ensure a demographic majority of white people within South Africa by having all ten Bantustans achieve full independence.

Inter-racial contact in sport was frowned upon, but there were no segregatory sports laws.

The government tightened pass laws compelling blacks to carry identity documents, to prevent the immigration of blacks from other countries. To reside in a city, blacks had to be in employment there. Until 1956 women were for the most part excluded from these ''pass'' requirements, as attempts to introduce ''pass laws'' for women were met with fierce resistance.

Disenfranchisement of Coloured voters

In 1950, D. F. Malan announced the NP's intention to create a Coloured Affairs Department. J.G. Strijdom, Malan's successor as prime minister, moved to strip voting rights from black and Coloured residents of the Cape Province. The previous government had introduced the Separate Representation of Voters Bill into Parliament in 1951, turning it to be an Act on 18 June 1951; however, four voters, G Harris, W D Franklin, W D Collins and Edgar Deane, challenged its validity in court with support from the United Party. The Cape Supreme Court upheld the act, but reversed by the Appeal Court, finding the act invalid because a two-thirds majority in a joint sitting of both Houses of

In 1950, D. F. Malan announced the NP's intention to create a Coloured Affairs Department. J.G. Strijdom, Malan's successor as prime minister, moved to strip voting rights from black and Coloured residents of the Cape Province. The previous government had introduced the Separate Representation of Voters Bill into Parliament in 1951, turning it to be an Act on 18 June 1951; however, four voters, G Harris, W D Franklin, W D Collins and Edgar Deane, challenged its validity in court with support from the United Party. The Cape Supreme Court upheld the act, but reversed by the Appeal Court, finding the act invalid because a two-thirds majority in a joint sitting of both Houses of Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

was needed to change the entrenched clauses of the Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organization or other type of entity, and commonly determines how that entity is to be governed.

When these pri ...

. The government then introduced the High Court of Parliament Bill (1952), which gave Parliament the power to overrule decisions of the court. The Cape Supreme Court and the Appeal Court declared this invalid too.

In 1955 the Strijdom government increased the number of judges in the Appeal Court from five to 11, and appointed pro-Nationalist judges to fill the new places. In the same year they introduced the Senate Act, which increased the Senate from 49 seats to 89. Adjustments were made such that the NP controlled 77 of these seats. The parliament met in a joint sitting and passed the Separate Representation of Voters Act in 1956, which transferred Coloured voters from the common voters' roll in the Cape to a new Coloured voters' roll. Immediately after the vote, the Senate was restored to its original size. The Senate Act was contested in the Supreme Court, but the recently enlarged Appeal Court, packed with government-supporting judges, upheld the act, and also the Act to remove Coloured voters.

The 1956 law allowed Coloureds to elect four people to Parliament, but a 1969 law abolished those seats and stripped Coloureds of their right to vote. Since Indians had never been allowed to vote, this resulted in whites being the sole enfranchised group.

Separate representatives for coloured voters were first elected in the general election of 1958. Even this limited representation did not last, being ended from 1970 by the Separate Representation of Voters Amendment Act, 1968. Instead, all coloured adults were given the right to vote for the Coloured Persons Representative Council, which had limited legislative powers. The council was in turn dissolved in 1980. In 1984 a new constitution introduced the Tricameral Parliament in which coloured voters elected the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entities. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often ...

.

A 2016 study in '' The Journal of Politics'' suggests that disenfranchisement in South Africa had a significant negative effect on basic service delivery to the disenfranchised.

Division among whites

Before South Africa became a republic in 1961, politics among white South Africans was typified by the division between the mainly Afrikaner

Afrikaners () are a Southern African ethnic group descended from predominantly Dutch settlers who first arrived at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652.Entry: Cape Colony. ''Encyclopædia Britannica Volume 4 Part 2: Brain to Casting''. Encyclopæd ...

pro-republic conservative and the largely English anti-republican liberal sentiments, with the legacy of the Boer War still a factor for some people. Once South Africa became a republic, Prime Minister Hendrik Verwoerd called for improved relations and greater accord between people of British descent and the Afrikaners. He claimed that the only difference was between those in favour of apartheid and those against it. The ethnic division would no longer be between Afrikaans and English speakers, but between blacks and whites.

Most Afrikaners supported the notion of unanimity of white people to ensure their safety. White voters of British descent were divided. Many had opposed a republic, leading to a majority "no" vote in Natal. Later, some of them recognised the perceived need for white unity, convinced by the growing trend of decolonisation elsewhere in Africa, which concerned them. British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

's " Wind of Change" speech left the British faction feeling that the United Kingdom had abandoned them. The more conservative English speakers supported Verwoerd; others were troubled by the severing of ties with the UK and remained loyal to the Crown

The Crown is a political concept used in Commonwealth realms. Depending on the context used, it generally refers to the entirety of the State (polity), state (or in federal realms, the relevant level of government in that state), the executive ...

. They were displeased by having to choose between British and South African nationalities. Although Verwoerd tried to bond these different blocs, the subsequent voting illustrated only a minor swell of support, indicating that a great many English speakers remained apathetic and that Verwoerd had not succeeded in uniting the white population.

Homeland system

Under the homeland system, the government attempted to divide South Africa and South West Africa into a number of separate states, each of which was supposed to develop into a separate nation-state for a different ethnic group.

Under the homeland system, the government attempted to divide South Africa and South West Africa into a number of separate states, each of which was supposed to develop into a separate nation-state for a different ethnic group.[p. 15]

Territorial separation was hardly a new institution. There were, for example, the "reserves" created under the British government in the nineteenth century. Under apartheid, 13 percent of the land was reserved for black homelands, a small amount relative to its total population, and generally in economically unproductive areas of the country. The Tomlinson Commission of 1954 justified apartheid and the homeland system, but stated that additional land ought to be given to the homelands, a recommendation that was not carried out.

When Verwoerd became prime minister in 1958, the policy of "separate development" came into being, with the homeland structure as one of its cornerstones. Verwoerd came to believe in the granting of independence to these homelands. The government justified its plans on the ostensible basis that "(the) government's policy is, therefore, not a policy of discrimination on the grounds of race or colour, but a policy of differentiation on the ground of nationhood, of different nations, granting to each self-determination within the borders of their homelandshence this policy of separate development". Under the homelands system, blacks would no longer be citizens of South Africa, becoming citizens of the independent homelands who worked in South Africa as foreign migrant labourers on temporary work permits. In 1958 the Promotion of Black Self-Government Act was passed, and border industries and the Bantu Investment Corporation were established to promote economic development and the provision of employment in or near the homelands. Many black South Africans who had never resided in their identified homeland were forcibly removed from the cities to the homelands.

The vision of a South Africa divided into multiple ethnostates appealed to the reform-minded Afrikaner intelligentsia, and it provided a more coherent philosophical and moral framework for the National Party's policies, while also providing a veneer of intellectual respectability to the controversial policy of so-called baasskap. In total, 20 homelands were allocated to ethnic groups, ten in South Africa proper and ten in South West Africa. Of these 20 homelands, 19 were classified as black, while one, Basterland, was set aside for a sub-group of Coloureds known as Basters, who are closely related to Afrikaners. Four of the homelands were declared independent by the South African government:

In total, 20 homelands were allocated to ethnic groups, ten in South Africa proper and ten in South West Africa. Of these 20 homelands, 19 were classified as black, while one, Basterland, was set aside for a sub-group of Coloureds known as Basters, who are closely related to Afrikaners. Four of the homelands were declared independent by the South African government: Transkei

Transkei ( , meaning ''the area beyond Great Kei River, he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei (), was an list of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa f ...

in 1976, Bophuthatswana

Bophuthatswana (, ), officially the Republic of Bophuthatswana (; ), and colloquially referred to as the Bop and by outsiders as Jigsawland (In reference to its enclave-ridden borders) was a Bantustan (also known as "Homeland", an area set asid ...

in 1977, Venda in 1979, and Ciskei in 1981 (known as the TBVC states). Once a homeland was granted its nominal independence, its designated citizens had their South African citizenship revoked and replaced with citizenship in their homeland. These people were then issued passports instead of passbooks. Citizens of the nominally autonomous homelands also had their South African citizenship circumscribed, meaning they were no longer legally considered South African.[Those who had the money to travel or emigrate were not given full passports; instead, travel documents were issued.] The South African government attempted to draw an equivalence between their view of black citizens of the homelands and the problems which other countries faced through entry of illegal immigrants.

International recognition of the Bantustans

Bantustans within the borders of South Africa and South West Africa were classified by degree of nominal self-rule: 6 were "non-self-governing", 10 were "self-governing", and 4 were "independent". In theory, self-governing Bantustans had control over many aspects of their internal functioning but were not yet sovereign nations. Independent Bantustans (Transkei, Bophutatswana, Venda and Ciskei; also known as the TBVC states) were intended to be fully sovereign. In reality, they had no significant economic infrastructure and with few exceptions encompassed swaths of disconnected territory. This meant all the Bantustans were little more than puppet states controlled by South Africa.

Throughout the existence of the independent Bantustans, South Africa remained the only country to recognise their independence. Nevertheless, internal organisations of many countries, as well as the South African government, lobbied for their recognition. For example, upon the foundation of Transkei, the Swiss-South African Association encouraged the Swiss government to recognise the new state. In 1976, leading up to a United States House of Representatives resolution urging the President to not recognise Transkei, the South African government intensely lobbied lawmakers to oppose the bill. Each TBVC state extended recognition to the other independent Bantustans while South Africa showed its commitment to the notion of TBVC sovereignty by building embassies in the TBVC capitals.

Forced removals

During the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, the government implemented a policy of "resettlement", to force people to move to their designated "group areas". Millions of people were forced to relocate. These removals included people relocated due to

During the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, the government implemented a policy of "resettlement", to force people to move to their designated "group areas". Millions of people were forced to relocate. These removals included people relocated due to slum clearance

Slum clearance, slum eviction or slum removal is an urban renewal strategy used to transform low-income settlements with poor reputation into another type of development or housing. This has long been a strategy for redeveloping urban communities; ...

programmes, labour tenants on white-owned farms, the inhabitants of the so-called "black spots" (black-owned land surrounded by white farms), the families of workers living in townships close to the homelands, and "surplus people" from urban areas, including thousands of people from the Western Cape (which was declared a "Coloured Labour Preference Area")Transkei

Transkei ( , meaning ''the area beyond Great Kei River, he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei (), was an list of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa f ...

and Ciskei homelands. The best-publicised forced removals of the 1950s occurred in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

, when 60,000 people were moved to the new township of Soweto

Soweto () is a Township (South Africa), township of the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality in Gauteng, South Africa, bordering the city's mining belt in the south. Its name is an English syllabic abbreviation for ''South Western T ...

(an abbreviation for South Western Townships).Soweto

Soweto () is a Township (South Africa), township of the City of Johannesburg Metropolitan Municipality in Gauteng, South Africa, bordering the city's mining belt in the south. Its name is an English syllabic abbreviation for ''South Western T ...

. Sophiatown was destroyed by bulldozers, and a new white suburb named Triomf (Triumph) was built in its place. This pattern of forced removal and destruction was to repeat itself over the next few years, and was not limited to black South Africans alone. Forced removals from areas like Cato Manor (Mkhumbane) in Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

, and District Six in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

, where 55,000 Coloured and Indian people

Indian people or Indians are the Indian nationality law, citizens and nationals of the India, Republic of India or people who trace their ancestry to India. While the demonym "Indian" applies to people originating from the present-day India, ...

were forced to move to new townships on the Cape Flats, were carried out under the Group Areas Act of 1950. Nearly 600,000 Coloured, Indian and Chinese people

The Chinese people, or simply Chinese, are people or ethnic groups identified with Greater China, China, usually through ethnicity, nationality, citizenship, or other affiliation.

Chinese people are known as Zhongguoren () or as Huaren () by ...

were moved under the Group Areas Act. Some 40,000 whites were also forced to move when land was transferred from "white South Africa" into the black homelands. In South-West Africa, the apartheid plan that instituted Bantustans was as a result of the so-called Odendaal Plan, a set of proposals from the Odendaal Commission of 1962–1964.

Society during apartheid

The NP passed a string of legislation that became known as ''petty apartheid''. The first of these was the Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Act 55 of 1949, prohibiting marriage between whites and people of other races. The Immorality Amendment Act 21 of 1950 (as amended in 1957 by Act 23) forbade "unlawful racial intercourse" and "any immoral or indecent act" between a white and a black, Indian or Coloured person.

Black people were not allowed to run businesses or professional practices in areas designated as "white South Africa" unless they had a permit – such being granted only exceptionally. Without a permit, they were required to move to the black "homelands" and set up businesses and practices there. Trains, hospitals and ambulances were segregated. Because of the smaller numbers of white patients and the fact that white doctors preferred to work in white hospitals, conditions in white hospitals were much better than those in often overcrowded and understaffed, significantly underfunded black hospitals.[Health Sector Strategic Framework 1999–2004 – Background](_blank)

, Department of Health, 2004. Retrieved 8 November 2006. Residential areas were segregated and blacks were allowed to live in white areas only if employed as a servant and even then only in servants' quarters. Black people were excluded from working in white areas, unless they had a pass, nicknamed the ''dompas'', also spelt ''dompass'' or ''dom pass''. The most likely origin of this name is from the Afrikaans "verdomde pas" (meaning accursed pass).[Dictionary of South African English on historical principles](_blank)

. Retrieved 27 December 2015. Only black people with "Section 10" rights (those who had migrated to the cities before World War II) were excluded from this provision. A pass was issued only to a black person with approved work. Spouses and children had to be left behind in black homelands. A pass was issued for one magisterial district (usually one town) confining the holder to that area only. Being without a valid pass made a person subject to arrest and trial for being an illegal migrant. This was often followed by deportation to the person's homeland and prosecution of the employer for employing an illegal migrant. Police vans patrolled white areas to round up blacks without passes. Black people were not allowed to employ whites in white South Africa.

This legally enforced segregation was reinforced through deliberate town planning measures, such as introducing natural, industrial and infrastructural buffer zones. The legacy of this town planning element still hinders economic integration of urban economies today.

Although trade unions for black and Coloured workers had existed since the early 20th century, it was not until the 1980s reforms that a mass black trade union movement developed. Trade unions

A trade union (British English) or labor union (American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages ...

under apartheid were racially segregated, with 54 unions being white only, 38 for Indian and Coloured and 19 for black people. The Industrial Conciliation Act (1956) legislated against the creation of multi-racial trade unions and attempted to split existing multi-racial unions into separate branches or organisations along racial lines.

Each black homeland controlled its own education, health and police systems. Blacks were not allowed to buy hard liquor. They were able to buy only state-produced poor quality beer (although this law was relaxed later). Public beaches, swimming pools, some pedestrian bridges, drive-in cinema parking spaces, graveyards, parks, and public toilets were segregated. Cinemas and theatres in white areas were not allowed to admit blacks. There were practically no cinemas in black areas. Most restaurants and hotels in white areas were not allowed to admit blacks except as staff. Blacks were prohibited from attending white churches under the Churches Native Laws Amendment Act of 1957, but this was never rigidly enforced, and churches were one of the few places races could mix without the interference of the law. Blacks earning 360 rand a year or more had to pay taxes while the white threshold was more than twice as high, at 750 rand a year. On the other hand, the taxation rate for whites was considerably higher than that for blacks.

Blacks could not acquire land in white areas. In the homelands, much of the land belonged to a "tribe", where the local chieftain would decide how the land had to be used. This resulted in whites owning almost all the industrial and agricultural lands and much of the prized residential land. Most blacks were stripped of their South African citizenship when the "homelands" became "independent", and they were no longer able to apply for South African passports. Eligibility requirements for a passport had been difficult for blacks to meet, the government contending that a passport was a privilege, not a right, and the government did not grant many passports to blacks. Apartheid pervaded culture as well as the law, and was entrenched by most of the mainstream media

In journalism, mainstream media (MSM) is a term and abbreviation used to refer collectively to the various large Mass media, mass news media that influence many people and both reflect and shape prevailing currents of thought.Noam Chomsky, Choms ...

.

Coloured classification

The population was classified into four groups: African, White, Indian, and Coloured (capitalised to denote their legal definitions in South African law). The Coloured group included people regarded as being of mixed descent, including of Bantu, Khoisan

Khoisan ( ) or () is an Hypernymy and hyponymy, umbrella term for the various Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples of Southern Africa who traditionally speak non-Bantu languages, combining the Khoekhoen and the San people, Sān peo ...

, European and Malay ancestry. Many were descended from slaves, or indentured workers, who had been brought to South Africa from India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

, Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka, officially the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka, also known historically as Ceylon, is an island country in South Asia. It lies in the Indian Ocean, southwest of the Bay of Bengal, separated from the Indian subcontinent, ...

, Madagascar

Madagascar, officially the Republic of Madagascar, is an island country that includes the island of Madagascar and numerous smaller peripheral islands. Lying off the southeastern coast of Africa, it is the world's List of islands by area, f ...

, and China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. With population of China, a population exceeding 1.4 billion, it is the list of countries by population (United Nations), second-most populous country after ...

.[Patric Tariq Melle]

"Intro"

''Cape Slavery Heritage''. Retrieved 24 May 2011.

The Population Registration Act, (Act 30 of 1950), defined South Africans as belonging to one of three races: White, Black or Coloured. People of Indian ancestry were considered Coloured under this act. Appearance, social acceptance and descent were used to determine the qualification of an individual into one of the three categories. A white person was described by the act as one whose parents were both white and possessed the "habits, speech, education, deportment and demeanour" of a white person. Blacks were defined by the act as belonging to an African race or tribe. Lastly, Coloureds were those who could not be classified as black or white.voting rights

Suffrage, political franchise, or simply franchise is the right to vote in representative democracy, public, political elections and referendums (although the term is sometimes used for any right to vote). In some languages, and occasionally in ...

, but the Black majority were to become citizens of independent homelands.

Education

Education

Education is the transmission of knowledge and skills and the development of character traits. Formal education occurs within a structured institutional framework, such as public schools, following a curriculum. Non-formal education als ...

was segregated by the 1953 Bantu Education Act, which crafted a separate system of education for black South African students and was designed to prepare black people for lives as a labouring class.Afrikaans

Afrikaans is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language spoken in South Africa, Namibia and to a lesser extent Botswana, Zambia, Zimbabwe and also Argentina where there is a group in Sarmiento, Chubut, Sarmiento that speaks the Pat ...

and English on an equal basis in high schools outside the homelands.Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

) was to register only Xhosa-speaking students. Sotho, Tswana, Pedi and Venda speakers were placed at the newly founded University College of the North at Turfloop, while the University College of Zululand was launched to serve Zulu students. Coloureds and Indians were to have their own establishments in the Cape

A cape is a clothing accessory or a sleeveless outer garment of any length that hangs loosely and connects either at the neck or shoulders. They usually cover the back, shoulders, and arms. They come in a variety of styles and have been used th ...

and Natal respectively.

Each black homeland controlled its own education, health and police systems.

By 1948, before formal Apartheid, 10 universities existed in South Africa: four were Afrikaans, four for English, one for Blacks and a Correspondence University open to all ethnic groups. By 1981, under apartheid government, 11 new universities were built: seven for Blacks, one for Coloureds, one for Indians, one for Afrikaans and one dual-language medium Afrikaans and English.

Women under apartheid

The colonialist ideology established under apartheid had a major effect on Black and Coloured women, with them suffering due to both racial and gender discrimination while being politically pushed to the margins. Scholar Judith Nolde has argued that, in general, the discriminatory system set up a "triple yoke of oppression: gender, race, and class" such that South African women became "deprive of their fundamental "human rights as individuals." Jobs were often hard to find. Many Black and Coloured women worked as agricultural employees or as domestic worker

A domestic worker is a person who works within a residence and performs a variety of household services for an individual, from providing cleaning and household maintenance, or cooking, laundry and ironing, or care for children and elderly ...

s, but wages were extremely low, if existent at all.malnutrition

Malnutrition occurs when an organism gets too few or too many nutrients, resulting in health problems. Specifically, it is a deficiency, excess, or imbalance of energy, protein and other nutrients which adversely affects the body's tissues a ...

and sanitation problems given the oppressive public policies, and mortality rate

Mortality rate, or death rate, is a measure of the number of deaths (in general, or due to a specific cause) in a particular Statistical population, population, scaled to the size of that population, per unit of time. Mortality rate is typically ...

s were therefore high. The controlled movement of black and Coloured workers within the country caused by the Natives Urban Areas Act of 1923 and restrictive 'pass laws' separated family members from one another. This occurred because the apartheid system perceived that men could prove their employment in urban centres while most women were merely dependents; consequently, they risked being deported to rural areas.

Sport under apartheid

By the 1930s, association football

Association football, more commonly known as football or soccer, is a team sport played between two teams of 11 Football player, players who almost exclusively use their feet to propel a Ball (association football), ball around a rectangular f ...

mirrored the balkanised society of South Africa; football was divided into numerous institutions based on race: the (White) South African Football Association, the South African Indian Football Association (SAIFA), the South African African Football Association (SAAFA) and its rival the South African Bantu Football Association, and the South African Coloured Football Association (SACFA). Lack of funds to provide proper equipment would be noticeable in regards to black amateur football matches; this revealed the unequal lives black South Africans were subject to, in contrast to Whites, who were much better off financially. Apartheid's social engineering made it more difficult to compete across racial lines. Thus, in an effort to centralise finances, the federations merged in 1951, creating the South African Soccer Federation (SASF), which brought Black, Indian, and Coloured national associations into one body that opposed apartheid. This was generally opposed more and more by the growing apartheid government, andwith urban segregation being reinforced with ongoing racist policiesit was harder to play football along these racial lines. In 1956, the Pretoria regimethe administrative capital of South Africapassed the first apartheid sports policy; by doing so, it emphasised the White-led government's opposition to inter-racialism.

While football was plagued by racism, it also played a role in protesting apartheid and its policies. With the international bans from FIFA

The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (), more commonly known by its acronym FIFA ( ), is the international self-regulatory governing body of association football, beach soccer, and futsal. It was founded on 21 May 1904 to o ...

and other major sporting events, South Africa would be in the spotlight internationally. In a 1977 survey, white South Africans ranked the lack of international sport as one of the three most damaging consequences of apartheid.

Professional boxing

Activities in the sport of professional boxing were also affected, as there were 44 recorded professional boxing fights for national titles as deemed "for Whites only" between 1955 and 1979, and 397 fights as deemed "for non-Whites" between 1901 and 1978.

Asians during apartheid

Defining its Asian population, a minority that did not appear to belong to any of the initial three designated non-white groups, was a constant dilemma for the apartheid government.

The classification of " honorary white" (a term which would be ambiguously used throughout apartheid) was granted to immigrants from

Defining its Asian population, a minority that did not appear to belong to any of the initial three designated non-white groups, was a constant dilemma for the apartheid government.

The classification of " honorary white" (a term which would be ambiguously used throughout apartheid) was granted to immigrants from Japan

Japan is an island country in East Asia. Located in the Pacific Ocean off the northeast coast of the Asia, Asian mainland, it is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan and extends from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north to the East China Sea ...

, South Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the southern half of the Korea, Korean Peninsula and borders North Korea along the Korean Demilitarized Zone, with the Yellow Sea to the west and t ...

and Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia. The main geography of Taiwan, island of Taiwan, also known as ''Formosa'', lies between the East China Sea, East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocea ...

countries with which South Africa maintained diplomatic and economic relationsand to their descendants.

Indian South Africans during apartheid were classified many ranges of categories from "Asian" to "black" to "Coloured" and even the mono-ethnic category of "Indian", but never as white, having been considered "nonwhite" throughout South Africa's history. The group faced severe discrimination during the apartheid regime and were subject to numerous racialist policies.

In 2005, a retrospect study was done by Josephine C. Naidoo and Devi Moodley Rajab, where they interviewed a series of Indian South Africans about their experience living through apartheid; their study highlighted education, the workplace, and general day to day living. One participant who was a doctor said that it was considered the norm for Non-White and White doctors to mingle while working at the hospital but when there was any down time or breaks, they were to go back to their segregated quarters. Not only was there severe segregation for doctors, non-white, more specifically Indians, were paid three to four times less than their white counterparts. Many described being treated as a "third class citizen" due to the humiliation of the standard of treatment for non-white employees across many professions. Many Indians described a sense of justified superiority from whites due to the apartheid laws that, in the minds of White South Africans, legitimised those feelings. Another finding of this study was the psychological damage done to Indians living in South Africa during apartheid. One of the biggest long-term effects on Indians was the distrust of white South Africans. There was a strong degree of alienation that left a strong psychological feeling of inferiority.

Chinese South Africans

Chinese South Africans () are Overseas Chinese who reside in South Africa, including those whose ancestors came to South Africa in the early 20th century until Chinese immigration was banned under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1904. Chinese indu ...

who were descendants of migrant workers who came to work in the gold mines around Johannesburg in the late 19th centurywere initially either classified as "Coloured" or "Other Asian" and were subject to numerous forms of discrimination and restriction.Indonesians

Indonesians (Indonesian language, Indonesian: ''orang Indonesia'') are citizens or people who are identified with the country of Indonesia, regardless of their ethnic or religious background. There are more than Ethnic groups in Indonesia, 1,300 ...

arrived at the Cape of Good Hope as slaves until the abolishment of slavery during the 19th century. They were predominantly Muslim

Muslims () are people who adhere to Islam, a Monotheism, monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God ...

, were allowed religious freedom and formed their own ethnic group/community known as Cape Malays. They were classified as part of the Coloured racial group. This was the same for South Africans of Malaysian descent who were also classified as part of the Coloured race and thus considered "not-white".Canaan

CanaanThe current scholarly edition of the Septuagint, Greek Old Testament spells the word without any accents, cf. Septuaginta : id est Vetus Testamentum graece iuxta LXX interprets. 2. ed. / recogn. et emendavit Robert Hanhart. Stuttgart : D ...

region (the birthplace of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, which states that Jesus in Christianity, Jesus is the Son of God (Christianity), Son of God and Resurrection of Jesus, rose from the dead after his Crucifixion of Jesus, crucifixion, whose ...

and Judaism

Judaism () is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic, Monotheism, monotheistic, ethnic religion that comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Jews, Jewish people. Religious Jews regard Judaism as their means of o ...

), they could not be discriminated against by race laws which targeted non-believers, and thus, were classified as white. The Lebanese community maintained their white status after the Population Registration Act came into effect; however, further immigration from the Middle East was restricted.

Conservatism

Alongside apartheid, the National Party implemented a programme of social conservatism

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and a variety of conservatism which places emphasis on Tradition#In political and religious discourse, traditional social structures over Cultural pluralism, social pluralism. Social conservatives ...

. Pornography, gambling

Gambling (also known as betting or gaming) is the wagering of something of Value (economics), value ("the stakes") on a Event (probability theory), random event with the intent of winning something else of value, where instances of strategy (ga ...

and works from Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

and other socialist thinkers were banned. Cinemas, shops selling alcohol and most other businesses were forbidden from opening on Sundays. Abortion

Abortion is the early termination of a pregnancy by removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus. Abortions that occur without intervention are known as miscarriages or "spontaneous abortions", and occur in roughly 30–40% of all pregnan ...

,

Internal resistance

Apartheid sparked significant internal resistance.

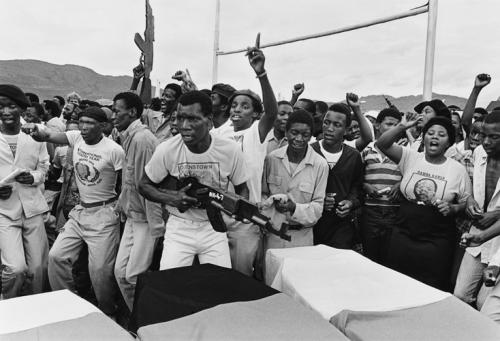

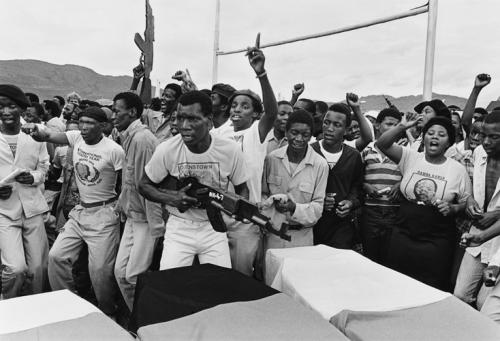

Apartheid sparked significant internal resistance.African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC) took control of the organisation and started advocating a radical African nationalist programme. The new young leaders proposed that white authority could only be overthrown through mass campaigns. In 1950 that philosophy saw the launch of the Programme of Action, a series of strikes, boycotts and civil disobedience actions that led to occasional violent clashes with the authorities.

In 1959, a group of disenchanted ANC members formed the Pan Africanist Congress of Azania (PAC), which organised a demonstration against pass books on 21 March 1960. One of those protests was held in the township of Sharpeville, where 69 people were killed by police in the Sharpeville massacre.

In the wake of Sharpeville, the government declared a state of emergency. More than 18,000 people were arrested, including leaders of the ANC and PAC, and both organisations were banned. The resistance went underground, with some leaders in exile abroad and others engaged in campaigns of domestic sabotage and terrorism.

In May 1961, before the declaration of South Africa as a Republic, an assembly representing the banned ANC called for negotiations between the members of the different ethnic groupings, threatening demonstrations and strikes during the inauguration of the Republic if their calls were ignored.

When the government overlooked them, the strikers (among the main organisers was a 42-year-old, Thembu-origin Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

) carried out their threats. The government countered swiftly by giving police the authority to arrest people for up to twelve days and detaining many strike leaders amid numerous cases of police brutality. Defeated, the protesters called off their strike. The ANC then chose to launch an armed struggle through a newly formed military wing, Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), which would perform acts of sabotage on tactical state structures. Its first sabotage plans were carried out on 16 December 1961, the anniversary of the Battle of Blood River

The Battle of Blood River or Voortrekker-Zulu War (16 December 1838) was fought on the bank of the Blood River, Ncome River, in what is today KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa between 464 Voortrekkers ("Pioneers"), led by Andries Pretorius, and an es ...

.

In the 1970s, the Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was created by tertiary students influenced by the Black Power movement in the US. BCM endorsed black pride and African customs and did much to alter the feelings of inadequacy instilled among black people by the apartheid system. The leader of the movement, Steve Biko, was taken into custody on 18 August 1977 and was beaten to death in detention.

In 1976, secondary students in Soweto took to the streets in the Soweto uprising to protest against the imposition of Afrikaans as the only language of instruction. On 16 June, police opened fire on students protesting peacefully. According to official reports 23 people were killed, but the number of people who died is usually given as 176, with estimates of up to 700.Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell ( ; born June 30, 1930) is an American economist, economic historian, and social and political commentator. He is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. With widely published commentary and books—and as a guest on T ...

wrote that basic supply and demand led to violations of Apartheid "on a massive scale" throughout the nation, simply because there were not enough white South African business owners to meet the demand for various goods and services. Large portions of the garment industry and construction of new homes, for example, were effectively owned and operated by blacks, who either worked surreptitiously or who circumvented the law with a white person as a nominal, figurehead manager.

In 1983, anti-apartheid leaders determined to resist the tricameral parliament assembled to form the United Democratic Front (UDF) in order to coordinate anti-apartheid activism inside South Africa. The first presidents of the UDF were Archie Gumede, Oscar Mpetha and Albertina Sisulu; patrons were Archbishop Desmond Tutu, Dr Allan Boesak, Helen Joseph, and Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

. Basing its platform on abolishing apartheid and creating a nonracial democratic South Africa, the UDF provided a legal way for domestic human rights groups and individuals of all races to organise demonstrations and campaign against apartheid inside the country. Churches and church groups also emerged as pivotal points of resistance. Church leaders were not immune to prosecution, and certain faith-based organisations were banned, but the clergy generally had more freedom to criticise the government than militant groups did. The UDF, coupled with the protection of the church, accordingly permitted a major role for Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who served both as a prominent domestic voice and international spokesperson denouncing apartheid and urging the creation of a shared nonracial state.

Although the majority of whites supported apartheid, some 20 percent did not. Parliamentary opposition was galvanised by Helen Suzman, Colin Eglin and Harry Schwarz, who formed the Progressive Federal Party. Extra-parliamentary resistance was largely centred in the South African Communist Party and women's organisation the Black Sash. Women were also notable in their involvement in trade union organisations and banned political parties. The public intellectuals too, such as Nadine Gordimer the eminent author and winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

(1991), vehemently opposed the Apartheid regime and accordingly bolstered the movement against it.

International relations during apartheid

Commonwealth

South Africa's policies were subject to international scrutiny in 1960, when British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986), was a British statesman and Conservative Party (UK), Conservative politician who was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1957 to 1963. Nickn ...

criticised them during his Wind of Change speech in Cape Town

Cape Town is the legislature, legislative capital city, capital of South Africa. It is the country's oldest city and the seat of the Parliament of South Africa. Cape Town is the country's List of municipalities in South Africa, second-largest ...

. Weeks later, tensions came to a head in the Sharpeville massacre, resulting in more international condemnation. Soon afterwards, Prime Minister

A prime minister or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. A prime minister is not the head of state, but r ...

Hendrik Verwoerd announced a referendum

A referendum, plebiscite, or ballot measure is a Direct democracy, direct vote by the Constituency, electorate (rather than their Representative democracy, representatives) on a proposal, law, or political issue. A referendum may be either bin ...

on whether the country should become a republic. Verwoerd lowered the voting age for Whites to eighteen years of age and included Whites in South West Africa