Life Expectancy In The Netherlands on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Life is a quality that distinguishes

Whether or not viruses should be considered as alive is controversial. They are most often considered as just

Whether or not viruses should be considered as alive is controversial. They are most often considered as just

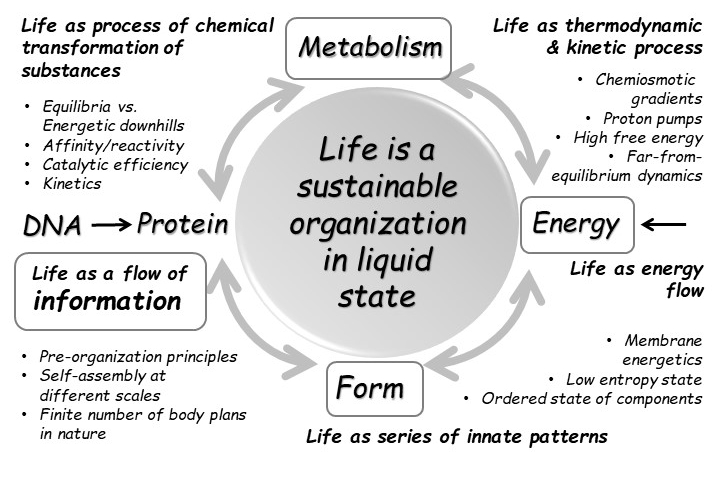

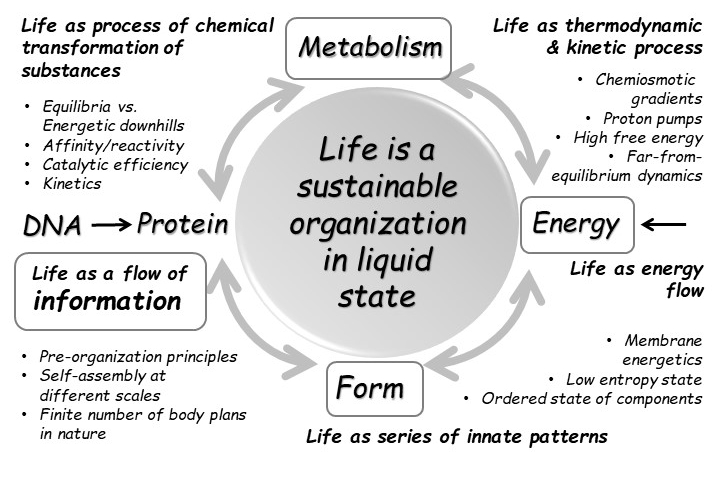

Budisa, Kubyshkin and Schmidt defined

Budisa, Kubyshkin and Schmidt defined

Hylomorphism is a theory first expressed by the Greek philosopher

Hylomorphism is a theory first expressed by the Greek philosopher

Although the number of Earth's catalogued species of lifeforms is between 1.2 million and 2 million, the total number of species in the planet is uncertain. Estimates range from 8 million to 100 million, with a more narrow range between 10 and 14 million, but it may be as high as 1 trillion (with only one-thousandth of one per cent of the species described) according to studies realised in May 2016. The total number of related DNA

Although the number of Earth's catalogued species of lifeforms is between 1.2 million and 2 million, the total number of species in the planet is uncertain. Estimates range from 8 million to 100 million, with a more narrow range between 10 and 14 million, but it may be as high as 1 trillion (with only one-thousandth of one per cent of the species described) according to studies realised in May 2016. The total number of related DNA

The diversity of life on Earth is a result of the dynamic interplay between

The diversity of life on Earth is a result of the dynamic interplay between

The inert components of an ecosystem are the physical and chemical factors necessary for life—energy (sunlight or biochemistry, chemical energy), water, heat,

The inert components of an ecosystem are the physical and chemical factors necessary for life—energy (sunlight or biochemistry, chemical energy), water, heat,

Death is the termination of all vital functions or life processes in an organism or cell. It can occur as a result of an accident, violence, medical conditions, biological interaction, malnutrition, poisoning, senescence, or suicide. After death, the remains of an organism re-enter the biogeochemical cycle. Organisms may be necrophagy, consumed by a predator or a scavenger and leftover

Death is the termination of all vital functions or life processes in an organism or cell. It can occur as a result of an accident, violence, medical conditions, biological interaction, malnutrition, poisoning, senescence, or suicide. After death, the remains of an organism re-enter the biogeochemical cycle. Organisms may be necrophagy, consumed by a predator or a scavenger and leftover

Life

(Systema Naturae 2000)

Vitae

(BioLib)

Biota

(Taxonomicon) * species:Main Page, Wikispecies – a free directory of life

Resources for life in the Solar System and in galaxy, and the potential scope of life in the cosmological future

''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' entry

The Kingdoms of Life

{{Authority control Life, Main topic articles

matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic parti ...

that has biological process

Biological processes are those processes that are vital for an organism to live, and that shape its capacities for interacting with its environment. Biological processes are made of many chemical reactions or other events that are involved in the ...

es, such as signaling

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The '' IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing' ...

and self-sustaining

Self-sustainability and self-sufficiency are overlapping states of being in which a person or organization needs little or no help from, or interaction with, others. Self-sufficiency entails the self being enough (to fulfill needs), and a self-s ...

processes, from that which does not, and is defined by the capacity for growth

Growth may refer to:

Biology

* Auxology, the study of all aspects of human physical growth

* Bacterial growth

* Cell growth

* Growth hormone, a peptide hormone that stimulates growth

* Human development (biology)

* Plant growth

* Secondary growth ...

, reaction to stimuli

A stimulus is something that causes a physiological response. It may refer to:

*Stimulation

**Stimulus (physiology), something external that influences an activity

**Stimulus (psychology), a concept in behaviorism and perception

*Stimulus (economi ...

, metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

, energy transformation

Energy transformation, also known as energy conversion, is the process of changing energy from one form to another. In physics, energy is a quantity that provides the capacity to perform Work (physics), work or moving, (e.g. Lifting an object) o ...

, and reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – " offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. Reproduction is a fundamental feature of all known life; each individual o ...

. Various forms of life exist, such as plant

Plants are predominantly photosynthetic eukaryotes of the kingdom Plantae. Historically, the plant kingdom encompassed all living things that were not animals, and included algae and fungi; however, all current definitions of Plantae ex ...

s, animal

Animals are multicellular, eukaryotic organisms in the biological kingdom Animalia. With few exceptions, animals consume organic material, breathe oxygen, are able to move, can reproduce sexually, and go through an ontogenetic stage ...

s, fungi

A fungus ( : fungi or funguses) is any member of the group of eukaryotic organisms that includes microorganisms such as yeasts and molds, as well as the more familiar mushrooms. These organisms are classified as a kingdom, separately from ...

, protist

A protist () is any eukaryotic organism (that is, an organism whose cells contain a cell nucleus) that is not an animal, plant, or fungus. While it is likely that protists share a common ancestor (the last eukaryotic common ancestor), the exclu ...

s, archaea

Archaea ( ; singular archaeon ) is a domain of single-celled organisms. These microorganisms lack cell nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. Archaea were initially classified as bacteria, receiving the name archaebacteria (in the Archae ...

, and bacteria. Biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

is the science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence ...

that studies life.

The gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ...

is the unit of heredity

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic info ...

, whereas the cell

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

is the structural and functional unit of life. There are two kinds of cells, prokaryotic

A prokaryote () is a single-celled organism that lacks a nucleus and other membrane-bound organelles. The word ''prokaryote'' comes from the Greek πρό (, 'before') and κάρυον (, 'nut' or 'kernel').Campbell, N. "Biology:Concepts & Con ...

and eukaryotic

Eukaryotes () are organisms whose cells have a nucleus. All animals, plants, fungi, and many unicellular organisms, are Eukaryotes. They belong to the group of organisms Eukaryota or Eukarya, which is one of the three domains of life. Bact ...

, both of which consist of cytoplasm

In cell biology, the cytoplasm is all of the material within a eukaryotic cell, enclosed by the cell membrane, except for the cell nucleus. The material inside the nucleus and contained within the nuclear membrane is termed the nucleoplasm. T ...

enclosed within a membrane and contain many biomolecules

A biomolecule or biological molecule is a loosely used term for molecules present in organisms that are essential to one or more typically biological processes, such as cell division, morphogenesis, or development. Biomolecules include large ...

such as proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

and nucleic acid

Nucleic acids are biopolymers, macromolecules, essential to all known forms of life. They are composed of nucleotides, which are the monomers made of three components: a 5-carbon sugar, a phosphate group and a nitrogenous base. The two main cl ...

s. Cells reproduce through a process of cell division

Cell division is the process by which a parent cell divides into two daughter cells. Cell division usually occurs as part of a larger cell cycle in which the cell grows and replicates its chromosome(s) before dividing. In eukaryotes, there a ...

, in which the parent cell divides into two or more daughter cells and passes its genes onto a new generation, sometimes producing genetic variation

Genetic variation is the difference in DNA among individuals or the differences between populations. The multiple sources of genetic variation include mutation and genetic recombination. Mutations are the ultimate sources of genetic variation, b ...

.

Organism

In biology, an organism () is any living system that functions as an individual entity. All organisms are composed of cells ( cell theory). Organisms are classified by taxonomy into groups such as multicellular animals, plants, and ...

s, or the individual entities of life, are generally thought to be open systems that maintain homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British also homoeostasis) (/hɒmɪə(ʊ)ˈsteɪsɪs/) is the state of steady internal, physical, and chemical conditions maintained by living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and i ...

, are composed of cells, have a life cycle, undergo metabolism, can grow, adapt

ADAPT (formerly American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today) is a United States grassroots disability rights organization with chapters in 30 states and Washington, D.C. They use nonviolent direct action in order to bring about disability jus ...

to their environment, respond to stimuli, reproduce and evolve over multiple generations. Other definitions sometimes include non-cellular life forms such as virus

A virus is a submicroscopic infectious agent that replicates only inside the living cells of an organism. Viruses infect all life forms, from animals and plants to microorganisms, including bacteria and archaea.

Since Dmitri Ivanovsky' ...

es and viroid

Viroids are small single-stranded, circular RNAs that are infectious pathogens. Unlike viruses, they have no protein coating. All known viroids are inhabitants of angiosperms (flowering plants), and most cause diseases, whose respective economi ...

s, but they are usually excluded because they do not function on their own; rather, they exploit the biological processes of hosts.

Abiogenesis

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothe ...

, also known as the Origin of Life, is the natural process of life arising from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

. Since its primordial beginnings, life on Earth has changed its environment on a geologic time scale

The geologic time scale, or geological time scale, (GTS) is a representation of time based on the rock record of Earth. It is a system of chronological dating that uses chronostratigraphy (the process of relating strata to time) and geochr ...

, but it has also adapted to survive in most ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

s and conditions. New lifeforms have evolved from common ancestors through hereditary

Heredity, also called inheritance or biological inheritance, is the passing on of traits from parents to their offspring; either through asexual reproduction or sexual reproduction, the offspring cells or organisms acquire the genetic info ...

variation and natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Char ...

, and today, estimates of the number of distinct species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of Taxonomy (biology), classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of ...

range anywhere from 3 million to over 100 million.

Death

Death is the irreversible cessation of all biological functions that sustain an organism. For organisms with a brain, death can also be defined as the irreversible cessation of functioning of the whole brain, including brainstem, and brain ...

is the permanent termination of all biological processes which sustain an organism, and as such, is the end of its life. Extinction

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed an ...

is the term describing the dying-out of a group or taxon

In biology, a taxon ( back-formation from '' taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular n ...

, usually a species. Fossil

A fossil (from Classical Latin , ) is any preserved remains, impression, or trace of any once-living thing from a past geological age. Examples include bones, shells, exoskeletons, stone imprints of animals or microbes, objects preserved ...

s are the preserved remains or traces

Traces may refer to:

Literature

* ''Traces'' (book), a 1998 short-story collection by Stephen Baxter

* ''Traces'' series, a series of novels by Malcolm Rose

Music Albums

* ''Traces'' (Classics IV album) or the title song (see below), 1969

* ''Tra ...

of organisms.

Definitions

The definition of life has long been a challenge for scientists and philosophers. This is partially because life is a process, not a substance. This is complicated by a lack of knowledge of the characteristics of living entities, if any, that may have developed outside of Earth. Philosophical definitions of life have also been put forward, with similar difficulties on how to distinguish living things from the non-living. Legal definitions of life have also been described and debated, though these generally focus on the decision to declare a human dead, and the legal ramifications of this decision. As many as 123 definitions of life have been compiled. One definition seems to be favoured by NASA: "a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution". More simply, life is "matter that can reproduce itself and evolve as survival dictates".Biology

Since there is no unequivocal definition of life, most current definitions in biology are descriptive. Life is considered a characteristic of something that preserves, furthers or reinforces its existence in the given environment. This characteristic exhibits all or most of the following traits: #Homeostasis

In biology, homeostasis (British also homoeostasis) (/hɒmɪə(ʊ)ˈsteɪsɪs/) is the state of steady internal, physical, and chemical conditions maintained by living systems. This is the condition of optimal functioning for the organism and i ...

: regulation of the internal environment to maintain a constant state; for example, sweating to reduce temperature

# Organisation: being structurally composed of one or more cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

– the basic units of life

# Metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

: transformation of energy by converting chemicals and energy into cellular components ( anabolism) and decomposing organic matter (catabolism

Catabolism () is the set of metabolic pathways that breaks down molecules into smaller units that are either oxidized to release energy or used in other anabolic reactions. Catabolism breaks down large molecules (such as polysaccharides, lipids, ...

). Living things require energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of h ...

to maintain internal organisation (homeostasis) and to produce the other phenomena associated with life.

# Growth

Growth may refer to:

Biology

* Auxology, the study of all aspects of human physical growth

* Bacterial growth

* Cell growth

* Growth hormone, a peptide hormone that stimulates growth

* Human development (biology)

* Plant growth

* Secondary growth ...

: maintenance of a higher rate of anabolism than catabolism. A growing organism increases in size in all of its parts, rather than simply accumulating matter.

# Adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the p ...

: the evolutionary process whereby an organism becomes better able to live in its habitat

In ecology, the term habitat summarises the array of resources, physical and biotic factors that are present in an area, such as to support the survival and reproduction of a particular species. A species habitat can be seen as the physical ...

or habitats.

# Response to stimuli

A stimulus is something that causes a physiological response. It may refer to:

*Stimulation

**Stimulus (physiology), something external that influences an activity

**Stimulus (psychology), a concept in behaviorism and perception

*Stimulus (economi ...

: a response can take many forms, from the contraction of a unicellular organism

A unicellular organism, also known as a single-celled organism, is an organism that consists of a single cell, unlike a multicellular organism that consists of multiple cells. Organisms fall into two general categories: prokaryotic organisms and ...

to external chemicals, to complex reactions involving all the senses of multicellular organisms

A multicellular organism is an organism that consists of more than one cell, in contrast to unicellular organism.

All species of animals, land plants and most fungi are multicellular, as are many algae, whereas a few organisms are partially un ...

. A response is often expressed by motion; for example, the leaves of a plant turning toward the sun (phototropism

Phototropism is the growth of an organism in response to a light stimulus. Phototropism is most often observed in plants, but can also occur in other organisms such as fungi. The cells on the plant that are farthest from the light contain a hor ...

), and chemotaxis

Chemotaxis (from '' chemo-'' + ''taxis'') is the movement of an organism or entity in response to a chemical stimulus. Somatic cells, bacteria, and other single-cell or multicellular organisms direct their movements according to certain chemi ...

.

# Reproduction

Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – " offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. Reproduction is a fundamental feature of all known life; each individual o ...

: the ability to produce new individual organisms, either asexually from a single parent organism or sexually from two parent organisms.

These complex processes, called physiological functions, have underlying physical and chemical bases, as well as signaling

In signal processing, a signal is a function that conveys information about a phenomenon. Any quantity that can vary over space or time can be used as a signal to share messages between observers. The '' IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing' ...

and control mechanisms that are essential to maintaining life.

Alternative definitions

From aphysics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which re ...

perspective, living beings are thermodynamic systems

A thermodynamic system is a body of matter and/or radiation, confined in space by walls, with defined permeabilities, which separate it from its surroundings. The surroundings may include other thermodynamic systems, or physical systems that are ...

with an organised molecular structure that can reproduce itself and evolve as survival dictates. Thermodynamically, life has been described as an open system which makes use of gradients in its surroundings to create imperfect copies of itself. Another way of putting this is to define life as "a self-sustained chemical system capable of undergoing Darwinian evolution

Darwinism is a theory of biological evolution developed by the English naturalist Charles Darwin (1809–1882) and others, stating that all species of organisms arise and develop through the natural selection of small, inherited variations that ...

", a definition adopted by a NASA committee attempting to define life for the purposes of exobiology

Astrobiology, and the related field of exobiology, is an interdisciplinary scientific field that studies the origins, early evolution, distribution, and future of life in the universe. Astrobiology is the multidisciplinary field that investi ...

, based on a suggestion by Carl Sagan

Carl Edward Sagan (; ; November 9, 1934December 20, 1996) was an American astronomer, planetary scientist, cosmologist, astrophysicist, astrobiologist, author, and science communicator. His best known scientific contribution is research on e ...

. A major strength of this definition is that it distinguishes life by the evolutionary process rather than its chemical composition.

Others take a systemic viewpoint that does not necessarily depend on molecular chemistry. One systemic definition of life is that living things are self-organizing

Self-organization, also called spontaneous order in the social sciences, is a process where some form of overall order arises from local interactions between parts of an initially disordered system. The process can be spontaneous when suffic ...

and autopoietic

The term autopoiesis () refers to a system capable of producing and maintaining itself by creating its own parts.

The term was introduced in the 1972 publication '' Autopoiesis and Cognition: The Realization of the Living'' by Chilean biologist ...

(self-producing). Variations of this definition include Stuart Kauffman

Stuart Alan Kauffman (born September 28, 1939) is an American medical doctor, theoretical biologist, and complex systems researcher who studies the origin of life on Earth. He was a professor at the University of Chicago, University of Pennsylv ...

's definition as an autonomous agent

An autonomous agent is an intelligent agent operating on a user's behalf but without any interference of that user. An intelligent agent, however appears according to an IBM white paper as:

Intelligent agents are software entities that carry out ...

or a multi-agent system

A multi-agent system (MAS or "self-organized system") is a computerized system composed of multiple interacting intelligent agents.Hu, J.; Bhowmick, P.; Jang, I.; Arvin, F.; Lanzon, A.,A Decentralized Cluster Formation Containment Framework fo ...

capable of reproducing itself or themselves, and of completing at least one thermodynamic work cycle. This definition is extended by the apparition of novel functions over time.

Viruses

Whether or not viruses should be considered as alive is controversial. They are most often considered as just

Whether or not viruses should be considered as alive is controversial. They are most often considered as just gene coding

The coding region of a gene, also known as the coding sequence (CDS), is the portion of a gene's DNA or RNA that codes for protein. Studying the length, composition, regulation, splicing, structures, and functions of coding regions compared to n ...

replicators rather than forms of life. They have been described as "organisms at the edge of life" because they possess gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ...

s, evolve by natural selection, and replicate by making multiple copies of themselves through self-assembly. However, viruses do not metabolise and they require a host cell to make new products. Virus self-assembly within host cells has implications for the study of the origin of life

In biology, abiogenesis (from a- 'not' + Greek bios 'life' + genesis 'origin') or the origin of life is the natural process by which life has arisen from non-living matter, such as simple organic compounds. The prevailing scientific hypothe ...

, as it may support the hypothesis that life could have started as self-assembling organic molecules

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

.

Biophysics

To reflect the minimum phenomena required, other biological definitions of life have been proposed, with many of these being based upon chemicalsystem

A system is a group of interacting or interrelated elements that act according to a set of rules to form a unified whole. A system, surrounded and influenced by its environment, is described by its boundaries, structure and purpose and expresse ...

s. Biophysicists have commented that living things function on negative entropy

In information theory and statistics, negentropy is used as a measure of distance to normality. The concept and phrase "negative entropy" was introduced by Erwin Schrödinger in his 1944 popular-science book '' What is Life?'' Later, Léon Bril ...

. In other words, living processes can be viewed as a delay of the spontaneous diffusion

Diffusion is the net movement of anything (for example, atoms, ions, molecules, energy) generally from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Diffusion is driven by a gradient in Gibbs free energy or chemical ...

or dispersion of the internal energy of biological molecules

A molecule is a group of two or more atoms held together by attractive forces known as chemical bonds; depending on context, the term may or may not include ions which satisfy this criterion. In quantum physics, organic chemistry, and bioche ...

towards more potential microstates

A microstate or ministate is a sovereign state having a very small population or very small land area, usually both. However, the meanings of "state" and "very small" are not well-defined in international law.Warrington, E. (1994). "Lilliputs ...

. In more detail, according to physicists such as John Bernal

John Desmond Bernal (; 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971) was an Irish scientist who pioneered the use of X-ray crystallography in molecular biology. He published extensively on the history of science. In addition, Bernal wrote popular book ...

, Erwin Schrödinger

Erwin Rudolf Josef Alexander Schrödinger (, ; ; 12 August 1887 – 4 January 1961), sometimes written as or , was a Nobel Prize-winning Austrian physicist with Irish citizenship who developed a number of fundamental results in quantum theo ...

, Eugene Wigner

Eugene Paul "E. P." Wigner ( hu, Wigner Jenő Pál, ; November 17, 1902 – January 1, 1995) was a Hungarian-American theoretical physicist who also contributed to mathematical physics. He received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1963 "for his con ...

, and John Avery, life is a member of the class of phenomena that are open

Open or OPEN may refer to:

Music

* Open (band), Australian pop/rock band

* The Open (band), English indie rock band

* ''Open'' (Blues Image album), 1969

* ''Open'' (Gotthard album), 1999

* ''Open'' (Cowboy Junkies album), 2001

* ''Open'' (Y ...

or continuous systems able to decrease their internal entropy

Entropy is a scientific concept, as well as a measurable physical property, that is most commonly associated with a state of disorder, randomness, or uncertainty. The term and the concept are used in diverse fields, from classical thermodyna ...

at the expense of substances or free energy taken in from the environment and subsequently rejected in a degraded form. The emergence and increasing popularity of biomimetics

Biomimetics or biomimicry is the emulation of the models, systems, and elements of nature for the purpose of solving complex human problems. The terms "biomimetics" and "biomimicry" are derived from grc, βίος (''bios''), life, and μίμη� ...

or biomimicry (the design and production of materials, structures, and systems that are modelled on biological entities and processes) will likely redefine the boundary between natural and artificial life

Artificial life (often abbreviated ALife or A-Life) is a field of study wherein researchers examine systems related to natural life, its processes, and its evolution, through the use of simulations with computer models, robotics, and biochemi ...

.

Living systems theories

Living systems are openself-organizing

Self-organization, also called spontaneous order in the social sciences, is a process where some form of overall order arises from local interactions between parts of an initially disordered system. The process can be spontaneous when suffic ...

living things that interact with their environment. These systems are maintained by flows of information, energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of h ...

, and matter.

Budisa, Kubyshkin and Schmidt defined

Budisa, Kubyshkin and Schmidt defined cellular life

The cell is the basic structural and functional unit of life forms. Every cell consists of a cytoplasm enclosed within a membrane, and contains many biomolecules such as proteins, DNA and RNA, as well as many small molecules of nutrients and ...

as an organizational unit resting on four pillars/cornerstones: (i) energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of h ...

, (ii) metabolism

Metabolism (, from el, μεταβολή ''metabolē'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run ...

, (iii) information

Information is an abstract concept that refers to that which has the power to inform. At the most fundamental level information pertains to the interpretation of that which may be sensed. Any natural process that is not completely random, ...

and (iv) form. This system is able to regulate and control metabolism and energy supply and contains at least one subsystem that functions as an information carrier (genetic information

A nucleic acid sequence is a succession of bases signified by a series of a set of five different letters that indicate the order of nucleotides forming alleles within a DNA (using GACT) or RNA (GACU) molecule. By convention, sequences are usua ...

). Cells

Cell most often refers to:

* Cell (biology), the functional basic unit of life

Cell may also refer to:

Locations

* Monastic cell, a small room, hut, or cave in which a religious recluse lives, alternatively the small precursor of a monastery w ...

as self-sustaining units are parts of different population

Population typically refers to the number of people in a single area, whether it be a city or town, region, country, continent, or the world. Governments typically quantify the size of the resident population within their jurisdiction using a ...

s that are involved in the unidirectional and irreversible open-ended process known as evolution

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

.

Some scientists have proposed in the last few decades that a general living systems

Living systems are open self-organizing life forms that interact with their environment. These systems are maintained by flows of information, energy and matter.

In the last few decades, some scientists have proposed that a general living systems ...

theory is required to explain the nature of life. Such a general theory would arise out of the ecological

Ecology () is the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere level. Ecology overlaps w ...

and biological sciences

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary ...

and attempt to map general principles for how all living systems work. Instead of examining phenomena by attempting to break things down into components, a general living systems theory explores phenomena in terms of dynamic patterns of the relationships of organisms with their environment.

Gaia hypothesis

The idea that Earth is alive is found in philosophy and religion, but the first scientific discussion of it was by the Scottish scientistJames Hutton

James Hutton (; 3 June O.S.172614 June 1726 New Style. – 26 March 1797) was a Scottish geologist, agriculturalist, chemical manufacturer, naturalist and physician. Often referred to as the father of modern geology, he played a key role ...

. In 1785, he stated that Earth was a superorganism and that its proper study should be physiology

Physiology (; ) is the scientific study of functions and mechanisms in a living system. As a sub-discipline of biology, physiology focuses on how organisms, organ systems, individual organs, cells, and biomolecules carry out the chemica ...

. Hutton is considered the father of geology, but his idea of a living Earth was forgotten in the intense reductionism

Reductionism is any of several related philosophical ideas regarding the associations between phenomena which can be described in terms of other simpler or more fundamental phenomena. It is also described as an intellectual and philosophical pos ...

of the 19th century. The Gaia hypothesis, proposed in the 1960s by scientist James Lovelock

James Ephraim Lovelock (26 July 1919 – 26 July 2022) was an English independent scientist, environmentalist and futurist. He is best known for proposing the Gaia hypothesis, which postulates that the Earth functions as a self-regulating sys ...

, suggests that life on Earth functions as a single organism that defines and maintains environmental

A biophysical environment is a biotic and abiotic surrounding of an organism or population, and consequently includes the factors that have an influence in their survival, development, and evolution. A biophysical environment can vary in scale f ...

conditions necessary for its survival. This hypothesis served as one of the foundations of the modern Earth system science

Earth system science (ESS) is the application of systems science to the Earth. In particular, it considers interactions and 'feedbacks', through material and energy fluxes, between the Earth's sub-systems' cycles, processes and "spheres"—atmos ...

.

Nonfractionability

Robert Rosen devoted a large part of his career, from 1958 onwards, to developing a comprehensive theory of life as a self-organizing complex system, "closed to efficient causation". He defined a system component as "a unit of organization; a part with a function, i.e., a definite relation between part and whole." He identified the "nonfractionability of components in an organism" as the fundamental difference between living systems and "biological machines." He summarised his views in his book ''Life Itself''. Similar ideas may be found in the book ''Living Systems'' byJames Grier Miller

James Grier Miller (19167 November 2002, California) was an American biologist, a pioneer of systems science and academic administrator, who originated the modern use of the term "behavioral science", founded and directed the multi-disciplinary ...

.

Life as a property of ecosystems

A systems view of life treats environmentalflux

Flux describes any effect that appears to pass or travel (whether it actually moves or not) through a surface or substance. Flux is a concept in applied mathematics and vector calculus which has many applications to physics. For transport p ...

es and biological fluxes together as a "reciprocity of influence," and a reciprocal relation with environment is arguably as important for understanding life as it is for understanding ecosystems. As Harold J. Morowitz

Harold Joseph Morowitz (December 4, 1927 – March 22, 2016) was an American biophysicist who studied the application of thermodynamics to living systems. Author of numerous books and articles, his work includes technical monographs as well as es ...

(1992) explains it, life is a property of an ecological system

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

rather than a single organism or species. He argues that an ecosystemic definition of life is preferable to a strictly biochemical

Biochemistry or biological chemistry is the study of chemical processes within and relating to living organisms. A sub-discipline of both chemistry and biology, biochemistry may be divided into three fields: structural biology, enzymology and ...

or physical one. Robert Ulanowicz

Robert Edward Ulanowicz ( ) is an American theoretical ecologist and philosopher of Polish descent who in his search for a ''unified theory of ecology'' has formulated a paradigm he calls ''Process Ecology''. He was born September 17, 1943 in Bal ...

(2009) highlights mutualism as the key to understand the systemic, order-generating behaviour of life and ecosystems.

Complex systems biology

Complex systems biology (CSB) is a field of science that studies the emergence of complexity in functional organisms from the viewpoint ofdynamic systems

In mathematics, a dynamical system is a system in which a function describes the time dependence of a point in an ambient space. Examples include the mathematical models that describe the swinging of a clock pendulum, the flow of water in ...

theory. The latter is also often called systems biology

Systems biology is the computational and mathematical analysis and modeling of complex biological systems. It is a biology-based interdisciplinary field of study that focuses on complex interactions within biological systems, using a holistic ...

and aims to understand the most fundamental aspects of life. A closely related approach to CSB and systems biology called relational biology is concerned mainly with understanding life processes in terms of the most important relations, and categories of such relations among the essential functional components of organisms; for multicellular organisms, this has been defined as "categorical biology", or a model representation of organisms as a category theory

Category theory is a general theory of mathematical structures and their relations that was introduced by Samuel Eilenberg and Saunders Mac Lane in the middle of the 20th century in their foundational work on algebraic topology. Nowadays, cat ...

of biological relations, as well as an algebraic topology

Algebraic topology is a branch of mathematics that uses tools from abstract algebra to study topological spaces. The basic goal is to find algebraic invariants that classify topological spaces up to homeomorphism, though usually most classify u ...

of the functional organisation

Functional may refer to:

* Movements in architecture:

** Functionalism (architecture)

** Form follows function

* Functional group, combination of atoms within molecules

* Medical conditions without currently visible organic basis:

** Functional ...

of living organisms in terms of their dynamic, complex networks of metabolic, genetic, and epigenetic

In biology, epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes (known as ''marks'') that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence. The Greek prefix '' epi-'' ( "over, outside of, around") in ''epigenetics'' implies features that are "o ...

processes and signalling pathway

In biology, cell signaling (cell signalling in British English) or cell communication is the ability of a cell to receive, process, and transmit signals with its environment and with itself. Cell signaling is a fundamental property of all cellula ...

s. Alternative but closely related approaches focus on the interdependence of constraints, where constraints can be either molecular, such as enzymes, or macroscopic, such as the geometry of a bone or of the vascular system.

Darwinian dynamic

It has also been argued that the evolution of order in living systems and certain physical systems obeys a common fundamental principle termed the Darwinian dynamic. The Darwinian dynamic was formulated by first considering how macroscopic order is generated in a simple non-biological system far from thermodynamic equilibrium, and then extending consideration to short, replicatingRNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

molecules. The underlying order-generating process was concluded to be basically similar for both types of systems.

Operator theory

Another systemic definition called the operator theory proposes that life is a general term for the presence of the typical closures found in organisms; the typical closures are a membrane and an autocatalytic set in the cell and that an organism is any system with an organisation that complies with an operator type that is at least as complex as the cell. Life can also be modelled as a network of inferiornegative feedback

Negative feedback (or balancing feedback) occurs when some function of the output of a system, process, or mechanism is fed back in a manner that tends to reduce the fluctuations in the output, whether caused by changes in the input or by othe ...

s of regulatory mechanisms subordinated to a superior positive feedback

Positive feedback (exacerbating feedback, self-reinforcing feedback) is a process that occurs in a feedback loop which exacerbates the effects of a small disturbance. That is, the effects of a perturbation on a system include an increase in th ...

formed by the potential of expansion and reproduction.

History of study

Materialism

Some of the earliest theories of life were materialist, holding that all that exists is matter, and that life is merely a complex form or arrangement of matter.Empedocles

Empedocles (; grc-gre, Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; , 444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is best known for originating the cosmogonic theory of the ...

(430 BC) argued that everything in the universe is made up of a combination of four eternal "elements" or "roots of all": earth, water, air, and fire. All change is explained by the arrangement and rearrangement of these four elements. The various forms of life are caused by an appropriate mixture of elements.

Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. N ...

(460 BC) thought that the essential characteristic of life is having a soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest atte ...

(''psyche''). Like other ancient writers, he was attempting to explain what makes something a ''living'' thing. His explanation was that fiery atoms make a soul in exactly the same way atoms and void account for any other thing. He elaborates on fire because of the apparent connection between life and heat, and because fire moves.

The mechanistic materialism that originated in ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

was revived and revised by the French philosopher René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Math ...

(1596–1650), who held that animals and humans were assemblages of parts that together functioned as a machine. This idea was developed further by Julien Offray de La Mettrie

Julien Offray de La Mettrie (; November 23, 1709 – November 11, 1751) was a French physician and philosopher, and one of the earliest of the French materialists of the Enlightenment. He is best known for his 1747 work '' L'homme machine'' ('' ...

(1709–1750) in his book ''L'Homme Machine''.

In the 19th century

The 19th (nineteenth) century began on 1 January 1801 ( MDCCCI), and ended on 31 December 1900 ( MCM). The 19th century was the ninth century of the 2nd millennium.

The 19th century was characterized by vast social upheaval. Slavery was abolish ...

, the advances in cell theory

In biology, cell theory is a scientific theory first formulated in the mid-nineteenth century, that living organisms are made up of cells, that they are the basic structural/organizational unit of all organisms, and that all cells come from pre ...

in biological science encouraged this view. The evolution

Evolution is change in the heredity, heritable Phenotypic trait, characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the Gene expression, expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to ...

ary theory of Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended f ...

(1859) is a mechanistic explanation for the origin of species by means of natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Char ...

.

At the beginning of the 20th century

The 20th (twentieth) century began on

January 1, 1901 ( MCMI), and ended on December 31, 2000 ( MM). The 20th century was dominated by significant events that defined the modern era: Spanish flu pandemic, World War I and World War II, nuclea ...

Stéphane Leduc

Stéphane Leduc (1 November 1853 – 8 March 1939) was a French biologist who sought to contribute to understanding of the chemical and physical mechanisms of life. He was a scientist in the fledgling field of synthetic biology, particularly in re ...

(1853–1939) promoted the idea that biological processes could be understood in terms of physics and chemistry, and that their growth resembled that of inorganic crystals immersed in solutions of sodium silicate. His ideas, set out in his book ''La biologie synthétique'' was widely dismissed during his lifetime, but has incurred a resurgence of interest in the work of Russell, Barge and colleagues.

Hylomorphism

Hylomorphism is a theory first expressed by the Greek philosopher

Hylomorphism is a theory first expressed by the Greek philosopher Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

(322 BC). The application of hylomorphism to biology was important to Aristotle, and biology is extensively covered in his extant writings. In this view, everything in the material universe has both matter and form, and the form of a living thing is its soul

In many religious and philosophical traditions, there is a belief that a soul is "the immaterial aspect or essence of a human being".

Etymology

The Modern English noun '' soul'' is derived from Old English ''sāwol, sāwel''. The earliest atte ...

(Greek ''psyche'', Latin ''anima''). There are three kinds of souls: the ''vegetative soul'' of plants, which causes them to grow and decay and nourish themselves, but does not cause motion and sensation; the ''animal soul'', which causes animals to move and feel; and the ''rational soul'', which is the source of consciousness and reasoning, which (Aristotle believed) is found only in man. Each higher soul has all of the attributes of the lower ones. Aristotle believed that while matter can exist without form, form cannot exist without matter, and that therefore the soul cannot exist without the body.

This account is consistent with teleological

Teleology (from and )Partridge, Eric. 1977''Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English'' London: Routledge, p. 4187. or finalityDubray, Charles. 2020 912Teleology" In ''The Catholic Encyclopedia'' 14. New York: Robert Appleton ...

explanations of life, which account for phenomena in terms of purpose or goal-directedness. Thus, the whiteness of the polar bear's coat is explained by its purpose of camouflage. The direction of causality (from the future to the past) is in contradiction with the scientific evidence for natural selection, which explains the consequence in terms of a prior cause. Biological features are explained not by looking at future optimal results, but by looking at the past evolutionary history

The history of life on Earth traces the processes by which living and fossil organisms evolved, from the earliest emergence of life to present day. Earth formed about 4.5 billion years ago (abbreviated as ''Ga'', for '' gigaannum'') and evid ...

of a species, which led to the natural selection of the features in question.

Spontaneous generation

Spontaneous generation was the belief that living organisms can form without descent from similar organisms. Typically, the idea was that certain forms such as fleas could arise from inanimate matter such as dust or the supposed seasonal generation of mice and insects from mud or garbage. The theory of spontaneous generation was proposed byAristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of ...

, who compiled and expanded the work of prior natural philosophers and the various ancient explanations of the appearance of organisms; it was considered the best explanation for two millennia. It was decisively dispelled by the experiments of Louis Pasteur

Louis Pasteur (, ; 27 December 1822 – 28 September 1895) was a French chemist and microbiologist renowned for his discoveries of the principles of vaccination, microbial fermentation and pasteurization, the latter of which was named af ...

in 1859, who expanded upon the investigations of predecessors such as Francesco Redi

Francesco Redi (18 February 1626 – 1 March 1697) was an Italian physician, naturalist, biologist, and poet. He is referred to as the "founder of experimental biology", and as the "father of modern parasitology". He was the first person to ch ...

. Disproof of the traditional ideas of spontaneous generation is no longer controversial among biologists.

Vitalism

Vitalism is the belief that the life-principle is non-material. This originated withGeorg Ernst Stahl

Georg Ernst Stahl (22 October 1659 – 24 May 1734) was a German chemist, physician and philosopher. He was a supporter of vitalism, and until the late 18th century his works on phlogiston were accepted as an explanation for chemical processes. ...

(17th century), and remained popular until the middle of the 19th century. It appealed to philosophers such as Henri Bergson

Henri-Louis Bergson (; 18 October 1859 – 4 January 1941) was a French philosopherHenri Bergson. 2014. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 13 August 2014, from https://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/61856/Henri-Bergson

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (; or ; 15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher, prose poet, cultural critic, philologist, and composer whose work has exerted a profound influence on contemporary philosophy. He began his ca ...

, and Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held G. W. F. Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, ...

, anatomists like Xavier Bichat

Marie François Xavier Bichat (; ; 14 November 1771 – 22 July 1802) was a French anatomist and pathologist, known as the father of modern histology. Although he worked without a microscope, Bichat distinguished 21 types of elementary tissue ...

, and chemists like Justus von Liebig

Justus Freiherr von Liebig (12 May 1803 – 20 April 1873) was a German scientist who made major contributions to agricultural and biological chemistry, and is considered one of the principal founders of organic chemistry. As a professor at the ...

. Vitalism included the idea that there was a fundamental difference between organic and inorganic material, and the belief that organic material

Organic matter, organic material, or natural organic matter refers to the large source of carbon-based compounds found within natural and engineered, terrestrial, and aquatic environments. It is matter composed of organic compounds that have c ...

can only be derived from living things. This was disproved in 1828, when Friedrich Wöhler

Friedrich Wöhler () FRS(For) HonFRSE (31 July 180023 September 1882) was a German chemist known for his work in inorganic chemistry, being the first to isolate the chemical elements beryllium and yttrium in pure metallic form. He was the first ...

prepared urea

Urea, also known as carbamide, is an organic compound with chemical formula . This amide has two amino groups (–) joined by a carbonyl functional group (–C(=O)–). It is thus the simplest amide of carbamic acid.

Urea serves an important ...

from inorganic materials. This Wöhler synthesis

The Wöhler synthesis is the conversion of ammonium cyanate into urea. This chemical reaction was described in 1828 by Friedrich Wöhler. It is often cited as the starting point of modern organic chemistry. Although the Wöhler reaction concerns ...

is considered the starting point of modern organic chemistry

Organic chemistry is a subdiscipline within chemistry involving the scientific study of the structure, properties, and reactions of organic compounds and organic materials, i.e., matter in its various forms that contain carbon atoms.Clayden, J. ...

. It is of historical significance because for the first time an organic compound

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

was produced in inorganic

In chemistry, an inorganic compound is typically a chemical compound that lacks carbon–hydrogen bonds, that is, a compound that is not an organic compound. The study of inorganic compounds is a subfield of chemistry known as ''inorganic chemistr ...

reactions.

During the 1850s, Hermann von Helmholtz

Hermann Ludwig Ferdinand von Helmholtz (31 August 1821 – 8 September 1894) was a German physicist and physician who made significant contributions in several scientific fields, particularly hydrodynamic stability. The Helmholtz Association, ...

, anticipated by Julius Robert von Mayer

Julius Robert von Mayer (25 November 1814 – 20 March 1878) was a German physician, chemist, and physicist and one of the founders of thermodynamics. He is best known for enunciating in 1841 one of the original statements of the conservat ...

, demonstrated that no energy is lost in muscle movement, suggesting that there were no "vital forces" necessary to move a muscle. These results led to the abandonment of scientific interest in vitalistic theories, especially after Buchner's demonstration that alcoholic fermentation could occur in cell-free extracts of yeast.

Nonetheless, the belief still exists in pseudoscientific

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable clai ...

theories such as homoeopathy

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine. It was conceived in 1796 by the German physician Samuel Hahnemann. Its practitioners, called homeopaths, believe that a substance that causes symptoms of a dise ...

, which interprets diseases and sickness as caused by disturbances in a hypothetical vital force or life force.

Origin

Theage of Earth

The age of Earth is estimated to be 4.54 ± 0.05 billion years This age may represent the age of Earth's accretion, or core formation, or of the material from which Earth formed. This dating is based on evidence from radiometric age-dating of m ...

is about 4.54 billion years. Evidence suggests that life on Earth has existed for at least 3.5 billion years, Early edition, published online before print. with the oldest physical traces

Traces may refer to:

Literature

* ''Traces'' (book), a 1998 short-story collection by Stephen Baxter

* ''Traces'' series, a series of novels by Malcolm Rose

Music Albums

* ''Traces'' (Classics IV album) or the title song (see below), 1969

* ''Tra ...

of life dating back 3.7 billion years; however, some hypotheses, such as Late Heavy Bombardment

The Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB), or lunar cataclysm, is a hypothesized event thought to have occurred approximately 4.1 to 3.8 billion years (Ga) ago, at a time corresponding to the Neohadean and Eoarchean eras on Earth. According to the hypot ...

, suggest that life on Earth may have started even earlier, as early as 4.1–4.4 billion years ago, and the chemistry leading to life may have begun shortly after the Big Bang

The Big Bang event is a physical theory that describes how the universe expanded from an initial state of high density and temperature. Various cosmological models of the Big Bang explain the evolution of the observable universe from the ...

, 13.8 billion years ago, during an epoch when the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

was only 10–17 million years old.

More than 99% of all species of life forms, amounting to over five billion species, that ever lived on Earth are estimated to be extinct

Extinction is the termination of a kind of organism or of a group of kinds (taxon), usually a species. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of the species, although the capacity to breed and ...

.

Although the number of Earth's catalogued species of lifeforms is between 1.2 million and 2 million, the total number of species in the planet is uncertain. Estimates range from 8 million to 100 million, with a more narrow range between 10 and 14 million, but it may be as high as 1 trillion (with only one-thousandth of one per cent of the species described) according to studies realised in May 2016. The total number of related DNA

Although the number of Earth's catalogued species of lifeforms is between 1.2 million and 2 million, the total number of species in the planet is uncertain. Estimates range from 8 million to 100 million, with a more narrow range between 10 and 14 million, but it may be as high as 1 trillion (with only one-thousandth of one per cent of the species described) according to studies realised in May 2016. The total number of related DNA base pair

A base pair (bp) is a fundamental unit of double-stranded nucleic acids consisting of two nucleobases bound to each other by hydrogen bonds. They form the building blocks of the DNA double helix and contribute to the folded structure of both DN ...

s on Earth is estimated at 5.0 x 1037 and weighs 50 billion tonnes. In comparison, the total mass of the biosphere

The biosphere (from Greek βίος ''bíos'' "life" and σφαῖρα ''sphaira'' "sphere"), also known as the ecosphere (from Greek οἶκος ''oîkos'' "environment" and σφαῖρα), is the worldwide sum of all ecosystems. It can also be ...

has been estimated to be as much as 4 TtC (trillion tons of carbon

Carbon () is a chemical element with the symbol C and atomic number 6. It is nonmetallic and tetravalent—its atom making four electrons available to form covalent chemical bonds. It belongs to group 14 of the periodic table. Carbon makes u ...

). In July 2016, scientists reported identifying a set of 355 gene

In biology, the word gene (from , ; "... Wilhelm Johannsen coined the word gene to describe the Mendelian units of heredity..." meaning ''generation'' or ''birth'' or ''gender'') can have several different meanings. The Mendelian gene is a ...

s from the Last Universal Common Ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; th ...

(LUCA) of all organisms living on Earth.

All known life forms share fundamental molecular mechanisms, reflecting their common descent

Common descent is a concept in evolutionary biology applicable when one species is the ancestor of two or more species later in time. All living beings are in fact descendants of a unique ancestor commonly referred to as the last universal comm ...

; based on these observations, hypotheses on the origin of life attempt to find a mechanism explaining the formation of a universal common ancestor

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; th ...

, from simple organic molecule

In chemistry, organic compounds are generally any chemical compounds that contain carbon-hydrogen or carbon-carbon bonds. Due to carbon's ability to catenate (form chains with other carbon atoms), millions of organic compounds are known. The s ...

s via pre-cellular life to protocell

A protocell (or protobiont) is a self-organized, endogenously ordered, spherical collection of lipids proposed as a stepping-stone toward the origin of life. A central question in evolution is how simple protocells first arose and how they coul ...

s and metabolism. Models have been divided into "genes-first" and "metabolism-first" categories, but a recent trend is the emergence of hybrid models that combine both categories.

There is no current scientific consensus

Scientific consensus is the generally held judgment, position, and opinion of the majority or the supermajority of scientists in a particular field of study at any particular time.

Consensus is achieved through scholarly communication at confer ...

as to how life originated. However, most accepted scientific models build on the Miller–Urey experiment

The Miller–Urey experiment (or Miller experiment) is a famous chemistry experiment that simulated the conditions thought at the time (1952) to be present in the atmosphere of the early, prebiotic Earth, in order to test the hypothesis of the ...

and the work of Sidney Fox, which show that conditions on the primitive Earth favoured chemical reactions that synthesize amino acid

Amino acids are organic compounds that contain both amino and carboxylic acid functional groups. Although hundreds of amino acids exist in nature, by far the most important are the alpha-amino acids, which comprise proteins. Only 22 alpha a ...

s and other organic compounds from inorganic precursors, and phospholipid

Phospholipids, are a class of lipids whose molecule has a hydrophilic "head" containing a phosphate group and two hydrophobic "tails" derived from fatty acids, joined by an alcohol residue (usually a glycerol molecule). Marine phospholipids typ ...

s spontaneously form lipid bilayer

The lipid bilayer (or phospholipid bilayer) is a thin polar membrane made of two layers of lipid molecules. These membranes are flat sheets that form a continuous barrier around all cells. The cell membranes of almost all organisms and many v ...

s, the basic structure of a cell membrane

The cell membrane (also known as the plasma membrane (PM) or cytoplasmic membrane, and historically referred to as the plasmalemma) is a biological membrane that separates and protects the interior of all cells from the outside environment ( ...

.

Living organisms synthesize proteins

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

, which are polymer

A polymer (; Greek '' poly-'', "many" + '' -mer'', "part")

is a substance or material consisting of very large molecules called macromolecules, composed of many repeating subunits. Due to their broad spectrum of properties, both synthetic a ...

s of amino acids using instructions encoded by deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Protein synthesis

Protein biosynthesis (or protein synthesis) is a core biological process, occurring inside cells, balancing the loss of cellular proteins (via degradation or export) through the production of new proteins. Proteins perform a number of critical ...

entails intermediary ribonucleic acid

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

(RNA) polymers. One possibility for how life began is that genes originated first, followed by proteins; the alternative being that proteins came first and then genes.

However, because genes and proteins are both required to produce the other, the problem of considering which came first is like that of the chicken or the egg

The chicken or the egg causality dilemma is commonly stated as the question, "which came first: the chicken or the egg?" The dilemma stems from the observation that all chickens hatch from eggs and all chicken eggs are laid by chickens. "Chicke ...

. Most scientists have adopted the hypothesis that because of this, it is unlikely that genes and proteins arose independently.

Therefore, a possibility, first suggested by Francis Crick

Francis Harry Compton Crick (8 June 1916 – 28 July 2004) was an English molecular biologist, biophysicist, and neuroscientist. He, James Watson, Rosalind Franklin, and Maurice Wilkins played crucial roles in deciphering the helical struc ...

, is that the first life was based on RNA

Ribonucleic acid (RNA) is a polymeric molecule essential in various biological roles in coding, decoding, regulation and expression of genes. RNA and deoxyribonucleic acid ( DNA) are nucleic acids. Along with lipids, proteins, and carbohydra ...

, which has the DNA-like properties of information storage and the catalytic

Catalysis () is the process of increasing the rate of a chemical reaction by adding a substance known as a catalyst (). Catalysts are not consumed in the reaction and remain unchanged after it. If the reaction is rapid and the catalyst recy ...

properties of some proteins. This is called the RNA world hypothesis

The RNA world is a hypothetical stage in the evolutionary history of life on Earth, in which self-replicating RNA molecules proliferated before the evolution of DNA and proteins. The term also refers to the hypothesis that posits the existence ...

, and it is supported by the observation that many of the most critical components of cells (those that evolve the slowest) are composed mostly or entirely of RNA. Also, many critical cofactors ( ATP, Acetyl-CoA

Acetyl-CoA (acetyl coenzyme A) is a molecule that participates in many biochemical reactions in protein, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. Its main function is to deliver the acetyl group to the citric acid cycle (Krebs cycle) to be oxidized fo ...

, NADH

Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) is a coenzyme central to metabolism. Found in all living cells, NAD is called a dinucleotide because it consists of two nucleotides joined through their phosphate groups. One nucleotide contains an aden ...

, etc.) are either nucleotides or substances clearly related to them. The catalytic properties of RNA had not yet been demonstrated when the hypothesis was first proposed, but they were confirmed by Thomas Cech

Thomas Robert Cech (born December 8, 1947) is an American chemist who shared the 1989 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Sidney Altman, for their discovery of the catalytic properties of RNA. Cech discovered that RNA could itself cut strands of RNA, ...

in 1986.

One issue with the RNA world hypothesis is that synthesis of RNA from simple inorganic precursors is more difficult than for other organic molecules. One reason for this is that RNA precursors are very stable and react with each other very slowly under ambient conditions, and it has also been proposed that living organisms consisted of other molecules before RNA. However, the successful synthesis of certain RNA molecules under the conditions that existed prior to life on Earth has been achieved by adding alternative precursors in a specified order with the precursor phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from pho ...

present throughout the reaction. This study makes the RNA world hypothesis more plausible.

Geological findings in 2013 showed that reactive phosphorus

Phosphorus is a chemical element with the symbol P and atomic number 15. Elemental phosphorus exists in two major forms, white phosphorus and red phosphorus, but because it is highly reactive, phosphorus is never found as a free element on Ea ...

species (like phosphite

The general structure of a phosphite ester showing the lone pairs on the P

In organic chemistry, a phosphite ester or organophosphite usually refers to an organophosphorous compound with the formula P(OR)3. They can be considered as esters of ...

) were in abundance in the ocean before 3.5 Ga, and that Schreibersite

Schreibersite is generally a rare iron nickel phosphide mineral, , though common in iron-nickel meteorites. It has been found on Disko Island in Greenland and Illinois.

Another name used for the mineral is rhabdite. It forms tetragonal crystals ...

easily reacts with aqueous glycerol

Glycerol (), also called glycerine in British English and glycerin in American English, is a simple triol compound. It is a colorless, odorless, viscous liquid that is sweet-tasting and non-toxic. The glycerol backbone is found in lipids know ...

to generate phosphite and glycerol 3-phosphate

''sn''-Glycerol 3-phosphate is the organic ion with the formula HOCH2CH(OH)CH2OPO32-. It is one of three stereoisomers of the ester of dibasic phosphoric acid (HOPO32-) and glycerol. It is a component of glycerophospholipids. Equally appropriat ...

. It is hypothesized that Schreibersite

Schreibersite is generally a rare iron nickel phosphide mineral, , though common in iron-nickel meteorites. It has been found on Disko Island in Greenland and Illinois.

Another name used for the mineral is rhabdite. It forms tetragonal crystals ...

-containing meteorites

A meteorite is a solid piece of debris from an object, such as a comet, asteroid, or meteoroid, that originates in outer space and survives its passage through the atmosphere to reach the surface of a planet or moon. When the original object e ...

from the Late Heavy Bombardment

The Late Heavy Bombardment (LHB), or lunar cataclysm, is a hypothesized event thought to have occurred approximately 4.1 to 3.8 billion years (Ga) ago, at a time corresponding to the Neohadean and Eoarchean eras on Earth. According to the hypot ...

could have provided early reduced phosphorus, which could react with prebiotic organic molecules to form phosphorylate

In chemistry, phosphorylation is the attachment of a phosphate group to a molecule or an ion. This process and its inverse, dephosphorylation, are common in biology and could be driven by natural selection. Text was copied from this source, whi ...

d biomolecules, like RNA