Water Speed Record on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The world unlimited water speed record is the officially recognised fastest speed achieved by a water-borne vehicle, irrespective of propulsion method. The current unlimited record is , achieved by Australian Ken Warby in the ''

The world unlimited water speed record is the officially recognised fastest speed achieved by a water-borne vehicle, irrespective of propulsion method. The current unlimited record is , achieved by Australian Ken Warby in the ''

by Sanj Atwal, GuinnessWorldRecords.com, February 7, 2024 The record is one of the sporting world's most hazardous competitions; seven of the thirteen people who have attempted it since June 1930 have died trying. Two official attempts to beat Ken Warby's 1978 record resulted in the pilot's death, with Lee Taylor in 1980 and Craig Arfons in 1989. Despite this, there are several teams currently working to make further attempts. The record is ratified by the

Until 1911, steam-powered, propeller-driven vehicles held world water speed records.

* 1885, Nathanael Herreshoff's ''Stiletto'':

* 1893, William B. Cogswell's '' Feiseen'':

* 1897,

Until 1911, steam-powered, propeller-driven vehicles held world water speed records.

* 1885, Nathanael Herreshoff's ''Stiletto'':

* 1893, William B. Cogswell's '' Feiseen'':

* 1897,

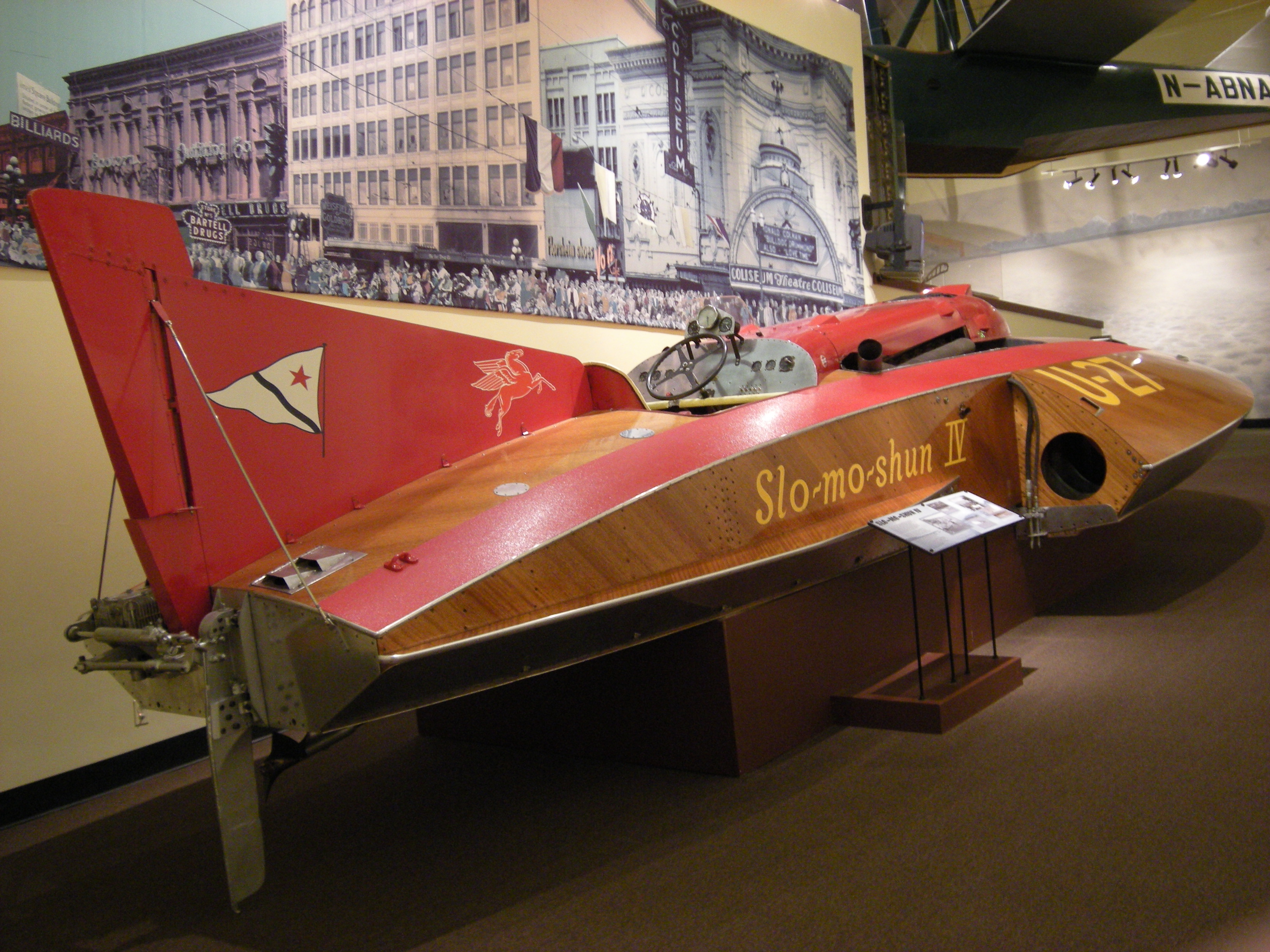

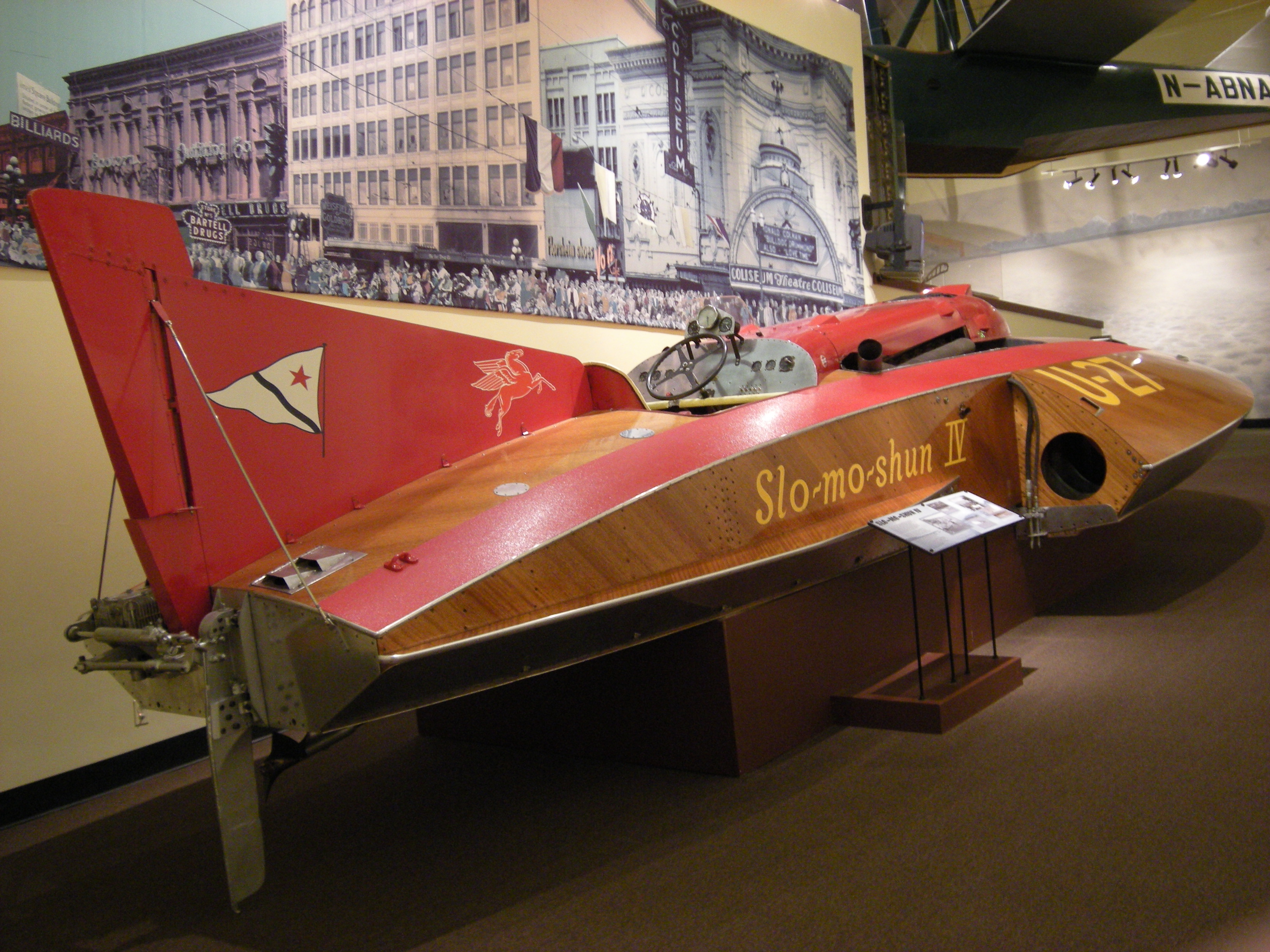

On 26 June 1950, '' Slo-Mo-Shun IV'' improved on Campbell's record by . Powered by an

On 26 June 1950, '' Slo-Mo-Shun IV'' improved on Campbell's record by . Powered by an

Donald Campbell, Bluebird, and the Final Record Attempt

* Th

Speed Record Club

seeks to promote an informed and educated enthusiast identity, reporting accurately and impartially on record-breaking engineering, events, attempts, and history to the best of its ability.

World Water Speed Record WWSR

- information on world water speed record and jet hydroplanes {{extreme motion Water speed

The world unlimited water speed record is the officially recognised fastest speed achieved by a water-borne vehicle, irrespective of propulsion method. The current unlimited record is , achieved by Australian Ken Warby in the ''

The world unlimited water speed record is the officially recognised fastest speed achieved by a water-borne vehicle, irrespective of propulsion method. The current unlimited record is , achieved by Australian Ken Warby in the ''Spirit of Australia

''Spirit of Australia'' is a wooden speed boat built in a Sydney backyard, by Ken Warby, that broke and set the world water speed record on 8 October 1978.

The record and boat

On 8 October 1978, Ken Warby rode the ''Spirit of Australia'' on ...

'' on 8 October 1978. Warby's record was still standing more than 45 years later."The deadly history of the water speed world record"by Sanj Atwal, GuinnessWorldRecords.com, February 7, 2024 The record is one of the sporting world's most hazardous competitions; seven of the thirteen people who have attempted it since June 1930 have died trying. Two official attempts to beat Ken Warby's 1978 record resulted in the pilot's death, with Lee Taylor in 1980 and Craig Arfons in 1989. Despite this, there are several teams currently working to make further attempts. The record is ratified by the

Union Internationale Motonautique

The Union Internationale Motonautique (UIM) is the international governing body of powerboating, based in the Principality of Monaco. It was founded in 1922, in Belgium, as the Union Internationale du Yachting Automobile.

History

Member nation ...

(UIM).

Before 1910

Until 1911, steam-powered, propeller-driven vehicles held world water speed records.

* 1885, Nathanael Herreshoff's ''Stiletto'':

* 1893, William B. Cogswell's '' Feiseen'':

* 1897,

Until 1911, steam-powered, propeller-driven vehicles held world water speed records.

* 1885, Nathanael Herreshoff's ''Stiletto'':

* 1893, William B. Cogswell's '' Feiseen'':

* 1897, Charles Algernon Parsons

Sir Charles Algernon Parsons (13 June 1854 – 11 February 1931) was an Anglo-Irish mechanical engineer and inventor who designed the modern steam turbine in 1884. His invention revolutionised marine propulsion, and he was also the founder of C ...

' ''Turbinia

''Turbinia'' is the first steam turbine-powered steamship. Built as an experimental vessel in 1894, and easily the fastest ship in the world at that time, ''Turbinia'' was demonstrated dramatically at the Fleet review (Commonwealth realms), Sp ...

'':

* 1903, Charles R. Flint's ''Arrow'':

1910s

In 1911, a stepped planing hull, ''Dixie IV'', designed by Clinton Crane, became the first gasoline-powered vessel to break the water speed record. In March 1911, the ''Maple Leaf III'', which was powered by two twelve-cylinder motors producing 350 hp each, set a new water speed record of onThe Solent

The Solent ( ) is a strait between the Isle of Wight and mainland Great Britain; the major historic ports of Southampton and Portsmouth lie inland of its shores. It is about long and varies in width between , although the Hurst Spit whic ...

.

Beginning in 1908, Alexander Graham Bell

Alexander Graham Bell (; born Alexander Bell; March 3, 1847 – August 2, 1922) was a Scottish-born Canadian Americans, Canadian-American inventor, scientist, and engineer who is credited with patenting the first practical telephone. He als ...

and engineer Frederick W. "Casey" Baldwin began experimenting with powered watercraft

A watercraft or waterborne vessel is any vehicle designed for travel across or through water bodies, such as a boat, ship, hovercraft, submersible or submarine.

Types

Historically, watercraft have been divided into two main categories.

*Raf ...

. In 1919, with Baldwin piloting their HD-4

''HD-4'' or ''Hydrodome number 4'' was an early research hydrofoil watercraft developed by the scientist Alexander Graham Bell. It was designed and built at the Bell Boatyard on Bell's Beinn Bhreagh estate near Baddeck, Nova Scotia. In 191 ...

hydrofoil

A hydrofoil is a lifting surface, or foil, that operates in water. They are similar in appearance and purpose to aerofoils used by aeroplanes. Boats that use hydrofoil technology are also simply termed hydrofoils. As a hydrofoil craft gains sp ...

, a new world water speed record of was set on Bras d'Or Lake

Bras d'Or Lake (Mi'kmaq language, Mi'kmawi'simk: Pitupaq) is an irregular estuary in the centre of Cape Breton Island in Nova Scotia, Canada. It has a connection to the open sea, and is tidal. It also has inflows of fresh water from rivers, ma ...

at Baddeck, Nova Scotia

Baddeck () is a village on Cape Breton Island in northeastern Nova Scotia, Canada. It is situated in the center of Cape Breton, approximately 6 km east of where the Baddeck River empties into Bras d'Or Lake.

Baddeck is the shire-town of th ...

.

1920s

In 1920,Garfield Wood

Garfield Arthur "Gar" Wood (December 4, 1880 – June 19, 1971) was an American inventor, entrepreneur, and championship motorboat builder and racer who held the world water speed record on several occasions. He was the first man to travel ...

set a new water speed record of on the Detroit River

The Detroit River is an List of international river borders, international river in North America. The river, which forms part of the border between the U.S. state of Michigan and the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Ont ...

, using a new boat called ''Miss America''. In the following twelve years, Wood built nine more ''Miss America''s and broke the record five times. Increased public interest generated by the speeds achieved by Wood and others led to an official speed record being ratified in 1928. The first person to try a record attempt was Wood's brother, George. On 4 September 1928, he drove ''Miss America VII'' to on the Detroit River. The next year, Gar Wood took the same boat up a waterway Indian Creek, Miami Beach and reached .

1930s

Like theland speed record

The land speed record (LSR) or absolute land speed record is the highest speed achieved by a person using a vehicle on land. By a 1964 agreement between the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) and Fédération Internationale de M ...

, the water record was destined to become a scrap for national honour between the United Kingdom and the United States. American success in setting records spurred Castrol

Castrol Limited is a British oil company that markets industrial and automotive lubricants, offering a wide range of oil, greases and similar products for most lubrication applications. The company was originally named CC Wakefield; the nam ...

Oil chairman Lord Wakefield to sponsor a project to bring the water record to Britain. Famed land speed racer and racing driver Sir Henry Segrave

Sir Henry O'Neal de Hane Segrave (22 September 1896 – 13 June 1930) was an early British pioneer in land speed and water speed records. Segrave, who set three land and one water record, was the first person to hold both titles simultaneou ...

was hired to pilot a new boat, ''Miss England

Miss England is a national beauty pageant in England.

History

The contest, title owned by the Miss World organisation is organised each year by Angie Beasley, a winner of 25 beauty contests in the 1980s and has organised beauty pageants aro ...

''. Although the boat was not capable of beating Wood's ''Miss America

Miss America is an annual competition that is open to women from the United States between the ages of 18 and 28. Originating in 1921 as a "bathing beauty revue", the contest is judged on competition segments with scoring percentages: ''Priva ...

'', the British team did gain experience, which was put into an improved boat. ''Miss England II

''Miss England II'' was the second of a series of speedboats used by Henry Segrave and Kaye Don to contest world water speed records in the 1920s and 1930s.

Design and construction

''Miss England II'' was built in 1930 for Lord Wakefield, who ...

'' was powered by two Rolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

aircraft engine

An aircraft engine, often referred to as an aero engine, is the power component of an aircraft propulsion system. Aircraft using power components are referred to as powered flight. Most aircraft engines are either piston engines or gas turbin ...

s and seemed capable of beating Wood's record.

On 13 June 1930, Segrave piloted ''Miss England II'' to a new record of average speed during two runs on Windermere

Windermere (historically Winder Mere) is a ribbon lake in Cumbria, England, and part of the Lake District. It is the largest lake in England by length, area, and volume, but considerably smaller than the List of lakes and lochs of the United Ki ...

, in Britain's Lake District

The Lake District, also known as ''the Lakes'' or ''Lakeland'', is a mountainous region and National parks of the United Kingdom, national park in Cumbria, North West England. It is famous for its landscape, including its lakes, coast, and mou ...

. Having set the record, Segrave set off on a third run to try to improve the record further. Unfortunately, the boat flipped during the run, with both Segrave and his co-driver receiving fatal injuries.

Following Segrave's death, ''Miss England II'' was salvaged and repaired. Kaye Don

Kaye Ernest Donsky (10 April 1891 – 29 August 1981), better known by his ''nom de course'' Kaye Don, was an Irish world record breaking car and speedboat racer. He became a motorcycle dealer on his retirement from road racing and set up Amb ...

was chosen as the new driver for 1931. However, during this time, Gar Wood recaptured the record for the U.S. at . A month later on Lake Garda

Lake Garda (, , or , ; ; ) is the largest lake in Italy. It is a popular holiday location in northern Italy, between Brescia and Milan to the west, and Verona and Venice to the east. The lake cuts into the edge of the Eastern Alps, Italian Alp ...

, Don got the record back with . In February 1932, Wood responded, nudging the mark to .

In response to the continued American challenge, the British team built a new boat, ''Miss England III

''Miss England III'' was the last of a series of speedboats used by Henry Segrave and Kaye Don to contest world water speed records in the 1920s and 1930s. She was the first craft in the Lloyd's unlimited rating, Lloyds Unlimited Group of high-per ...

''. The design was an evolution of the predecessor, with a squared-off stern

The stern is the back or aft-most part of a ship or boat, technically defined as the area built up over the sternpost, extending upwards from the counter rail to the taffrail. The stern lies opposite the bow, the foremost part of a ship. O ...

and twin propeller

A propeller (often called a screw if on a ship or an airscrew if on an aircraft) is a device with a rotating hub and radiating blades that are set at a pitch to form a helical spiral which, when rotated, exerts linear thrust upon a working flu ...

s being the main improvements. Don took the new boat to Loch Lomond

Loch Lomond (; ) is a freshwater Scottish loch which crosses the Highland Boundary Fault (HBF), often considered the boundary between the lowlands of Central Scotland and the Highlands.Tom Weir. ''The Scottish Lochs''. pp. 33-43. Published by ...

, Scotland, on 18 July 1932, improved the record first to , then to on a second run.

Determined to have the last word over his great rival, Gar Wood built another new ''Miss America''. '' Miss America X'' was long, powered by four supercharged Packard

Packard (formerly the Packard Motor Car Company) was an American luxury automobile company located in Detroit, Michigan. The first Packard automobiles were produced in 1899, and the last Packards were built in South Bend, Indiana, in 1958.

One ...

aeroplane engines. On 20 September 1932 Wood broke the barrier, driving his new boat to . It would prove the end of an era. Don declined to attempt any further records. Wood also opted to scale down his involvement in racing and returned to running his businesses. Somewhat ironically, both record-breakers lived into their 90s. Wood died in 1971, and Don in 1985.

Boat design changes

Wood's last record would be one of the final records for a conventional, single-keel

The keel is the bottom-most longitudinal structural element of a watercraft, important for stability. On some sailboats, it may have a fluid dynamics, hydrodynamic and counterbalancing purpose as well. The keel laying, laying of the keel is often ...

boat. In June 1937 Malcolm Campbell

Major Sir Malcolm Campbell (11 March 1885 – 31 December 1948) was a British racing motorist and motoring journalist. He gained the world speed record on land and on water at various times, using vehicles called ''Blue Bird'', including a 1 ...

, the world-famous land speed record breaker, drove '' Blue Bird K3'' to a new record of at Lake Maggiore

Lake Maggiore (, ; ; ; ; literally 'greater lake') or Verbano (; ) is a large lake located on the south side of the Alps. It is the second largest lake in Italy and the largest in southern Switzerland. The lake and its shoreline are divided be ...

. Compared to the massive ''Miss America X'', ''K3'' was a much more compact craft. It was 5 metres shorter and had one engine to X's four.

Despite his success, Campbell was unsatisfied with the relatively small increase in speed. He commissioned a new ''Blue Bird'' to be built. '' Blue Bird K4'' was a 'three pointer' hydroplane. Unlike conventional powerboat

A motorboat or powerboat is a boat that is exclusively powered by an engine; faster examples may be called "speedboats".

Some motorboats are fitted with inboard engines, others have an outboard motor installed on the rear, containing the inter ...

s, which have a single keel, with an indent, or 'step', cut from the bottom to reduce drag, a hydroplane has a concave

Concave or concavity may refer to:

Science and technology

* Concave lens

* Concave mirror

Mathematics

* Concave function, the negative of a convex function

* Concave polygon

A simple polygon that is not convex is called concave, non-convex or ...

base with two sponsons fitted to the front and a third point at the rear of the hull. When the boat increases in speed, most of the hull lifts out of the water and runs on the three contact points. The positive effect is reduced drag; the downside is that the three-pointer is much less stable than the single-keel boat. If the hydroplane's angle of attack

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or \alpha) is the angle between a Airfoil#Airfoil terminology, reference line on a body (often the chord (aircraft), chord line of an airfoil) and the vector (geometry), vector representing the relat ...

is upset at speed, the craft can somersault into the air or nose-dive into the water.

Campbell's new boat was a success. In 1939, on the eve of the Second World War, he took it to Coniston Water

Coniston Water is a lake in the Lake District in North West England. It is the third largest by volume, after Windermere and Ullswater, and the fifth-largest by area. The lake has a length of , a maximum width of , and a maximum depth of . Its ou ...

and increased his record by , to .

1940s

The return of peace in 1945 brought a new form of power for the record breaker – thejet engine

A jet engine is a type of reaction engine, discharging a fast-moving jet (fluid), jet of heated gas (usually air) that generates thrust by jet propulsion. While this broad definition may include Rocket engine, rocket, Pump-jet, water jet, and ...

. Campbell immediately renovated ''Blue Bird K4'' with a De Havilland Goblin jet engine. The result was a curious-looking craft whose shoe-like profile led to it being nicknamed 'The Coniston Slipper'. The jet-powered experiment was unsuccessful, and Campbell retired from record attempts. He died in 1948.

1950s

On 26 June 1950, '' Slo-Mo-Shun IV'' improved on Campbell's record by . Powered by an

On 26 June 1950, '' Slo-Mo-Shun IV'' improved on Campbell's record by . Powered by an Allison V-1710

The Allison V-1710 aircraft engine designed and produced by the Allison Engine Company was the most common United States, US-developed V12 engine, V-12 Internal combustion engine cooling, liquid-cooled engine in service during World War II. Ve ...

aircraft engine, the boat was built by Seattle Chrysler

FCA US, LLC, Trade name, doing business as Stellantis North America and known historically as Chrysler ( ), is one of the "Big Three (automobile manufacturers), Big Three" automobile manufacturers in the United States, headquartered in Auburn H ...

dealer Stanley Sayres and was able to run because her hull was designed to lift the top of the propeller out of water when running at high speed. This phenomenon, called 'prop riding', further reduced drag.

In 1952, Sayres drove ''Slo-Mo-Shun'' to , a increase on his previous record.

The renewed American success persuaded Malcolm Campbell's son, Donald

Donald is a Scottish masculine given name. It is derived from the Gaelic name ''Dòmhnall''.. This comes from the Proto-Celtic *''Dumno-ualos'' ("world-ruler" or "world-wielder"). The final -''d'' in ''Donald'' is partly derived from a misinter ...

, who had already driven ''Blue Bird K4'' within sight of his father's record, to further push for the record. However, ''Blue Bird K4'' was then 12 years old, with a 20-year-old engine, and Campbell struggled to reach the speeds of the Seattle-built boat. In late 1951, it was written off after suffering a structural failure at on Coniston Water.

At this time, yet another land-speed driver entered the fray. Englishman John Cobb was hoping to reach in his jet-powered '' Crusader''. A radical design, the ''Crusader'' reversed the 'three-pointer' design, placing the sponsons at the rear of the hull. On 29 September 1952, Cobb tried to beat the world record on Loch Ness

Loch Ness (; ) is a large freshwater loch in the Scottish Highlands. It takes its name from the River Ness, which flows from the northern end. Loch Ness is best known for claimed sightings of the cryptozoology, cryptozoological Loch Ness Mons ...

but, while travelling at an estimated , ''Crusaders front plane collapsed and the craft instantly disintegrated. Cobb was retrieved from the water but had already died.

Two years later, on 8 October 1954, another man would die trying for the record. Italian textile magnates Mario Verga and Francesco Vitetta, responding to a prize offer of 5 million lire from the Italian Motorboat Federation to any Italian who broke the world record, built a sleek piston-engined hydroplane to claim the record. Named ''Laura III'', after Verga's daughter, the boat was fast but unstable. Travelling across Lake Iseo, in Northern Italy, at close to , Verga lost control of ''Laura III'' and was thrown out into the water when the boat somersaulted. Like Cobb, he died.

Following Cobb's death, Donald Campbell started working on a new ''Bluebird'', '' K7'', a jet-powered hydroplane. Learning the many lessons from Cobb's ill-starred ''Crusader'', K7 was designed as a classic 3-pointer with sponsons forward alongside the cockpit. She was designed by Ken and Lewis Norris in 1953-54 and was completed in early 1955. She was powered by a Metropolitan-Vickers Beryl turbojet of thrust. K7 was of all-metal construction and proved to have extremely high rigidity.

Campbell and ''K7'' set a new record of on Ullswater

Ullswater is a glacial lake in Cumbria, England and part of the Lake District National Park. It is the second largest lake in the region by both area and volume, after Windermere. The lake is about long, wide, and has a maximum depth of . I ...

in July 1955. Campbell and ''K7'' went on to break the record a further six times over the next nine years in the US and England (Coniston Water

Coniston Water is a lake in the Lake District in North West England. It is the third largest by volume, after Windermere and Ullswater, and the fifth-largest by area. The lake has a length of , a maximum width of , and a maximum depth of . Its ou ...

), finally increasing it to at Lake Dumbleyung in Western Australia in 1964. Campbell thus became the most prolific water speed record breaker of all time.

At the time Campbell set the absolute record, the piston-powered propeller-driven record was held by the George Simons' ''Miss U.S. I'' at . Roy Duby set this record at Guntersville, Alabama, in 1962 and stood for 38 years.

1967

Donald Campbell's ''Bluebird K7'' had been re-engined with aBristol Siddeley Orpheus

The Bristol Siddeley Orpheus is a single-spool turbojet developed by Bristol Siddeley for various light fighter/trainer applications such as the Folland Gnat and the Fiat G.91. Later, the Orpheus formed the core of the first Bristol Pegasus ...

jet rated at of thrust. On 4 January 1967, he tried again. His first run averaged , and a new record seemed in sight. Campbell applied ''K7s water brake to slow the craft down from her peak speed of clear of the measured kilometre to a speed around . Rather than waiting for the lake to settle again before starting the mandatory return leg, Campbell immediately turned around at the end of the lake and began his return run. At around , just as she entered the measured kilometre, ''Bluebird'' began to lose stability, and 400 m before the end of the kilometre, ''Bluebird''′s nose lifted beyond its critical pitch angle and she started to rise out of the water at a 45-degree angle. The boat took off, somersaulted, and then plunged nose-first into the lake, breaking up as she cartwheeled across the surface. Campbell was killed instantly. Over the next two weeks, prolonged searches discovered the wreck, but it was not until May 2001 that Campbell's body was finally located and recovered. Campbell was buried in the churchyard at Coniston on 12 September 2001. The 1988 television drama ''Across the Lake'' recreates the attempt.

Lee Taylor, a Californian boat racer in ''Hustler'' during a test run on Lake Havasu

Lake Havasu () is a large reservoir formed by Parker Dam on the Colorado River, on the border between San Bernardino County, California, and Mohave County, Arizona. Lake Havasu City sits on the Arizonan side of the lake with its Californian coun ...

on 14 April 1964, was unable to shut down the jet and crashed into the lakeside at over . ''Hustler'' was wrecked, and Taylor was severely injured. He spent the following years recuperating and rebuilding his boat. On 30 June 1967, on Lake Guntersville, Taylor and ''Hustler'' tried for the record. Still, the wake of some spectators' boats disturbed the water, forcing Taylor to slow down his second run, and he came up short. He tried again the same day and set a new record of .

1977 and 1978

Until 20 November 1977, every official water speed record had been set by an American, Canadian, Irishman, or Briton. That day Ken Warby became the first Australian holder when he piloted his ''Spirit of Australia

''Spirit of Australia'' is a wooden speed boat built in a Sydney backyard, by Ken Warby, that broke and set the world water speed record on 8 October 1978.

The record and boat

On 8 October 1978, Ken Warby rode the ''Spirit of Australia'' on ...

'' to to beat Lee Taylor's record. Warby, who had built the craft in his backyard, used the publicity to find sponsorship to pay for improvements to the Spirit. On 8 October 1978 Warby travelled to Blowering Dam, Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a country comprising mainland Australia, the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania and list of islands of Australia, numerous smaller isl ...

, and broke both the and barriers with an average speed of . As he exited the course, his peak speed as measured on a radar gun was approximately .

Warby's record still stands. There have only been two official attempts to break it, both resulting in the driver's death.

1980s

Lee Taylor tried to get the record back in 1980. Inspired by the land speed record cars '' Blue Flame'' and '' Budweiser Rocket'', he built a rocket-powered boat, '' Discovery II''. The long craft was a reverse three-point design, similar to John Cobb's ''Crusader'', but of much greater length. Originally, Taylor tested the boat on Walker Lake in Nevada, but his backers demanded a more accessible location, so he switched toLake Tahoe

Lake Tahoe (; Washo language, Washo: ''dáʔaw'') is a Fresh water, freshwater lake in the Sierra Nevada of the Western United States, straddling the border between California and Nevada. Lying at above sea level, Lake Tahoe is the largest a ...

. An attempt was set for 13 November 1980, but when conditions on the lake proved unfavourable, he decided against trying for the record. Not wanting to disappoint the assembled spectators and media, he did a test run instead. At 432 km/h (270 mph) ''Discovery II'' started to become unstable. It has been speculated that it may have hit a swell.. Its unstable lateral oscillations caused the left sponson to collapse, sending the boat plunging into the water. The cockpit section with Taylor's body was recovered three days later. The cockpit had not floated as intended, and Taylor drowned.

On 9 July 1989 Craig Arfons, son of Walt Arfons, builder of the world's first jet car, and nephew of record breaker Art Arfons

Arthur Eugene Arfons (February 3, 1926 – December 3, 2007) was the world land speed record holder three times from 1964 to 1965 with his ''Green Monster'' series of jet-powered cars, after a series of ''Green Monster'' piston-engine and j ...

, tried for the record in his all-composite fiberglass and Kevlar ''Rain X Challenger''. At 7:07am, less than 15 seconds into his run, the hydroplane somersaulted at more than . The cockpit remained intact underwater with Arfons remaining inside upside down. Two divers from a rescue team reached the wreckage and extracted him within three minutes of the initial incident. While he still had a pulse after cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is an emergency procedure used during Cardiac arrest, cardiac or Respiratory arrest, respiratory arrest that involves chest compressions, often combined with artificial ventilation, to preserve brain function ...

was administered, he did not respond to the medical personnel. He was taken to the Highlands Regional Medical Center but was pronounced dead at 8:30am, 1 hour and 23 minutes after the initial incident.

Current projects

Despite the high fatality rate, the record is still coveted by boat enthusiasts and racers. Ongoing projects aimed at breaking the record include the following:''Quicksilver''

The British ''Quicksilver'' project is managed by Nigel Macknight. The design was initially based on concepts for a rear-sponsoned configuration by Ken Norris, who had worked with the Campbells on their 'Bluebird' designs. The design is of modular construction with the main body consisting of a front section with a steel spaceframe incorporating the engine, aRolls-Royce Spey

The Rolls-Royce Spey (company designations RB.163 and RB.168 and RB.183) is a low-bypass turbofan engine originally designed and manufactured by Rolls-Royce that has been in widespread service for over 40 years. A co-development version of the ...

Mk.101, and the rear section a monocoque extending to the tail. The front sponsons are also modules, one of which contains the driver.

''Spirit of Australia II''

Ken Warby, now working with his son David, began build on a new boat powered by a jet engine from aFiat G.91

The Fiat G.91 is a jet fighter aircraft designed and built by the Italian aircraft manufacturer Fiat Aviazione, which later merged into Aeritalia.

The G.91 has its origins in the NATO-organised NBMR-1 competition started in 1953, which sough ...

to break the record. The team conducting a series of trials had, as of 31 August 2019, increased the speed to 407 km/h. Earlier in 2003, Ken Warby had built another boat, ''Aussie Spirit'', for a record attempt.

Ken Warby died in February 2023, with the project, now solely led by David Warby, conducting test runs that May and September at Blowering Dam, with further runs planned in November that year. Test runs are continuing as of October 2024, according to David Warby.

Dartagnan SP600

Daniel Dehaemers was the Belgian challenger for the absolute water speed record. The SP600 is of full carbon composite construction. It is powered by aRolls-Royce

Rolls-Royce (always hyphenated) may refer to:

* Rolls-Royce Limited, a British manufacturer of cars and later aero engines, founded in 1906, now defunct

Automobiles

* Rolls-Royce Motor Cars, the current car manufacturing company incorporated in ...

Adour 104 turbojet engine. The boat was planned to be tested in 2016. However, after finishing building the boat, he died of cancer in 2018 before he managed to trial the craft.

Alençon Jos restarted the project in 2019 with an expected engine test in 2020.

''LONGBOW''

A British team, with a serving British military pilot at the helm, are working together to build and run ''Longbow'', a jet hydroplane, on lakes and lochs within the UK, for a British attempt at the water speed record.Thrust WSH

Richard Noble, engineer behind the Thrust series ofland speed record

The land speed record (LSR) or absolute land speed record is the highest speed achieved by a person using a vehicle on land. By a 1964 agreement between the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (FIA) and Fédération Internationale de M ...

cars Thrust2 which he drove, and ThrustSSC

ThrustSSC, Thrust SSC or Thrust SuperSonic Car is a British jet car developed by Richard Noble, Glynne Bowsher, Ron Ayers, and Jeremy Bliss. Thrust SSC holds the world land speed record, set on 15 October 1997, and piloted by Andy Gree ...

, the supersonic Land Speed Record holder since 1997, announced on a YouTube video 27 May 2022 that his group intends to construct a water speed record boat, named ThrustWSH (Water Speed Hydroplane), conforming to the naming custom of ThrustSSC (Supersonic Car).

Record holders

See also

*Blue Riband

The Blue Riband () is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest Velocity, average speed. The term was borrowed from horse racing and was not widely used until ...

* Speed sailing record

* List of vehicle speed records

The following is a list of speed records for various types of vehicles. This list only presents the single greatest speed achieved in each broad record category; for more information on records under variations of test conditions, see the specific ...

* World Sailing Speed Record Council

Notes

References

* Fred Harris and Mike Rimmer (2001). ''Skimming the Surface''. * Kevin Desmond (1996). ''The World Water Speed Record''. Batsford. * Leo Villa (1969). ''The Record Breakers''. Hamlyn. * Bill Tuckey (2009). ''The World's Fastest Coffin on Water''. A biography of Ken Warby.External links

Donald Campbell, Bluebird, and the Final Record Attempt

* Th

Speed Record Club

seeks to promote an informed and educated enthusiast identity, reporting accurately and impartially on record-breaking engineering, events, attempts, and history to the best of its ability.

World Water Speed Record WWSR

- information on world water speed record and jet hydroplanes {{extreme motion Water speed