Lieutenant General

Lieutenant general (Lt Gen, LTG and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. The rank traces its origins to the Middle Ages, where the title of lieutenant general was held by the second-in-command on the battlefield, who was norma ...

Troy Houston Middleton (12 October 1889 – 9 October 1976) was a distinguished educator and senior

officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

of the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

who served as a

corps

Corps (; plural ''corps'' ; from French , from the Latin "body") is a term used for several different kinds of organization. A military innovation by Napoleon I, the formation was formally introduced March 1, 1800, when Napoleon ordered Gener ...

commander in the

European Theatre

The European theatre of World War II was one of the two main theatres of combat during World War II, taking place from September 1939 to May 1945. The Allied powers (including the United Kingdom, the United States, the Soviet Union and Franc ...

during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

and later as president of

Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as Louisiana State University (LSU), is an American Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louis ...

(LSU).

Enlisting in the U.S. Army in 1910, Middleton was first assigned to the

29th Infantry Regiment, where he worked as a clerk. Here he did not become an

infantry

Infantry, or infantryman are a type of soldier who specialize in ground combat, typically fighting dismounted. Historically the term was used to describe foot soldiers, i.e. those who march and fight on foot. In modern usage, the term broadl ...

man as he had hoped, but he was pressed into service playing football, a sport strongly endorsed by the army. Following two years of enlisted service, Middleton was transferred to

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas, where he was given the opportunity to compete for an

officer's commission

An officer is a person who holds a position of authority as a member of an armed force or uniformed service.

Broadly speaking, "officer" means a commissioned officer, a non-commissioned officer (NCO), or a warrant officer. However, absent c ...

. Of the 300 individuals who were vying for a commission, 56 were selected, and four of them, including Middleton, would become

general officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

s. As a new

second lieutenant, Middleton was assigned to the

7th Infantry Regiment in

Galveston, Texas

Galveston ( ) is a Gulf Coast of the United States, coastal resort town, resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island (Texas), Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a pop ...

, which was soon pressed into service, responding to events created by the

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

. Middleton spent seven months doing occupation duty in the Mexican port city of

Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

, and later was assigned to

Douglas, Arizona

Douglas is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, that lies in the north-west to south-east running Sulphur Springs Valley. Douglas has a Douglas, Arizona Port of Entry, border crossing with Mexico at Agua Prieta and a history of min ...

, where his unit skirmished with some of

Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ( , , ; born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula; 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a Mexican revolutionary and prominent figure in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced ...

's fighters.

Upon the

entry of the United States into

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

, in April 1917, Middleton was assigned to the

4th Infantry Division, and soon saw action as a battalion commander during the

Second Battle of the Marne. Three months later, following some minor support roles, his unit led the attack during the

Meuse-Argonne Offensive, and Middleton became a regimental commander. Because of his exceptional battlefield performance, on 14 October 1918 he was promoted to the rank of

colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

, becoming, at the age of 29, the youngest officer of that rank in the

American Expeditionary Force

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

(AEF). He also received the

Army Distinguished Service Medal

The Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a military decoration of the United States Army that is presented to soldiers who have distinguished themselves by exceptionally meritorious service to the government in a duty of great responsibility. ...

for his exemplary service. Following World War I, Middleton served at the

U.S. Army School of Infantry, the

U.S. Army Command and General Staff School, the

U.S. Army War College

The United States Army War College (USAWC) is a United States Army, U.S. Army staff college in Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania, with a Carlisle, Pennsylvania, Carlisle postal address, on the 500-acre (2 km2) campus of the historic Carlisle B ...

, and as commandant of cadets at LSU. He retired from the army in 1937 to become dean of administration and later

comptroller

A comptroller (pronounced either the same as ''controller'' or as ) is a management-level position responsible for supervising the quality of accountancy, accounting and financial reporting of an organization. A financial comptroller is a senior- ...

and acting vice president at LSU. His tenure at LSU was fraught with difficulty, as Middleton became one of the key players in helping the university recover from a major scandal where nearly a million dollars had been embezzled.

Recalled to service in early 1942, upon American entry into World War II, Middleton became CG of the

45th Infantry Division during the

Sicily

Sicily (Italian language, Italian and ), officially the Sicilian Region (), is an island in the central Mediterranean Sea, south of the Italian Peninsula in continental Europe and is one of the 20 regions of Italy, regions of Italy. With 4. ...

and

Salerno

Salerno (, ; ; ) is an ancient city and ''comune'' (municipality) in Campania, southwestern Italy, and is the capital of the namesake province, being the second largest city in the region by number of inhabitants, after Naples. It is located ...

battles in

Italy

Italy, officially the Italian Republic, is a country in Southern Europe, Southern and Western Europe, Western Europe. It consists of Italian Peninsula, a peninsula that extends into the Mediterranean Sea, with the Alps on its northern land b ...

, and then in March 1944 moved up to command the

VIII Corps 8th Corps, Eighth Corps, or VIII Corps may refer to:

* VIII Corps (Grande Armée), a unit of the Imperial French army during the Napoleonic Wars

* VIII Army Corps (German Confederation)

* VIII Corps (German Empire), a unit of the Imperial German Arm ...

. His leadership in

Operation Cobra

Operation Cobra was an offensive launched by the First United States Army under Lieutenant General Omar Bradley seven weeks after the D-Day landings, during the Normandy campaign of World War II. The intention was to take advantage of the dis ...

during the

Battle of Normandy

Operation Overlord was the codename for the Battle of Normandy, the Allied operation that launched the successful liberation of German-occupied Western Europe during World War II. The operation was launched on 6 June 1944 (D-Day) with the N ...

led to the capture of the important port city of

Brest, France

Brest (; ) is a port, port city in the Finistère department, Brittany (administrative region), Brittany. Located in a sheltered bay not far from the western tip of a peninsula and the western extremity of metropolitan France, Brest is an impor ...

, and for his success he was awarded a second Distinguished Service Medal by General George Patton. His greatest World War II achievement, however, was in his decision to hold the important city of

Bastogne

Bastogne (; ; ; ) is a city and municipality of Wallonia located in the province of Luxembourg in the Ardennes, Belgium.

The municipality consists of the following districts: Bastogne, Longvilly, Noville, Villers-la-Bonne-Eau, and Wardi ...

, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge. Following this battle, and his corps' relentless push across Germany until reaching

Czechoslovakia

Czechoslovakia ( ; Czech language, Czech and , ''Česko-Slovensko'') was a landlocked country in Central Europe, created in 1918, when it declared its independence from Austria-Hungary. In 1938, after the Munich Agreement, the Sudetenland beca ...

, he was recognized by both General

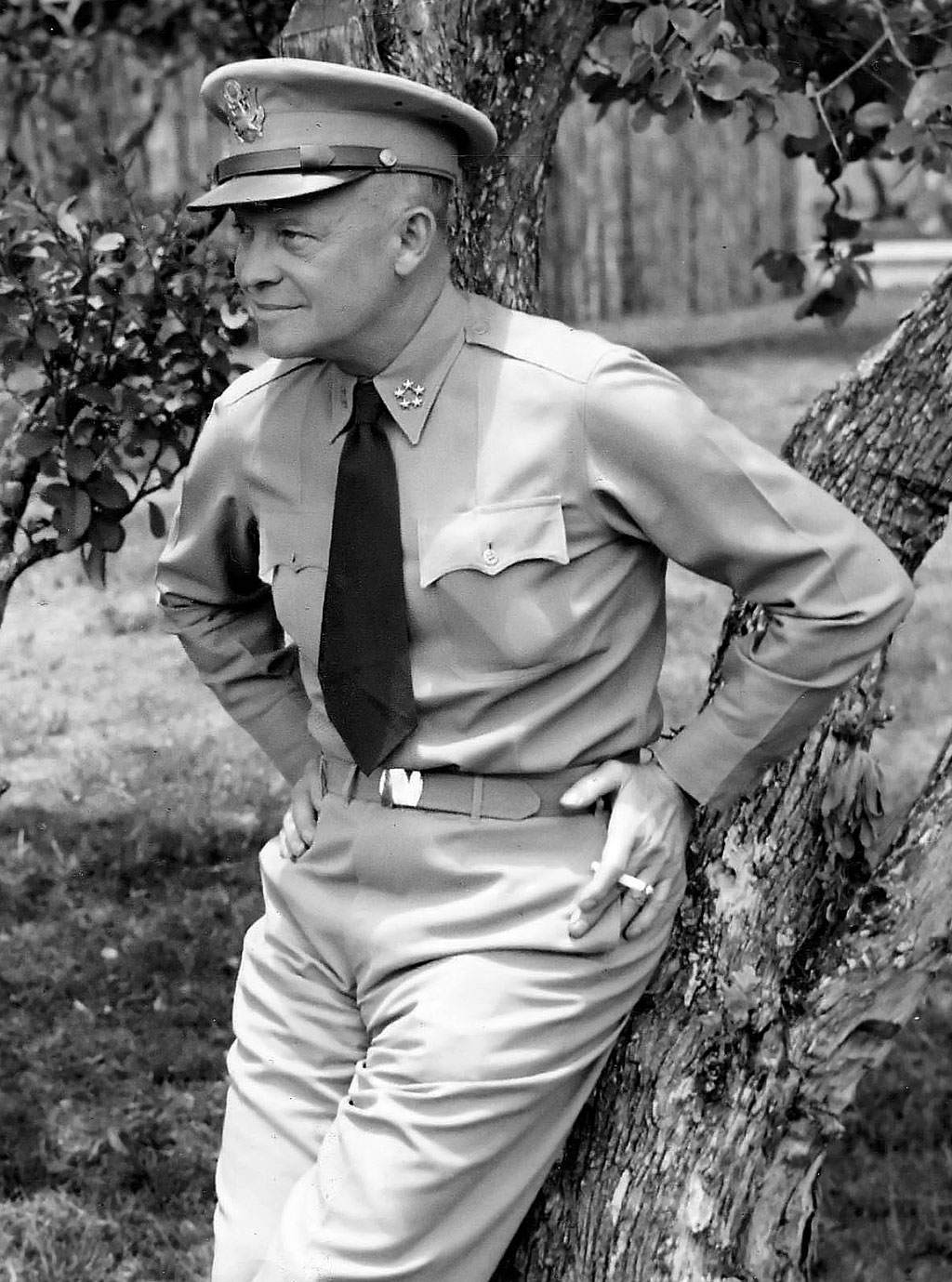

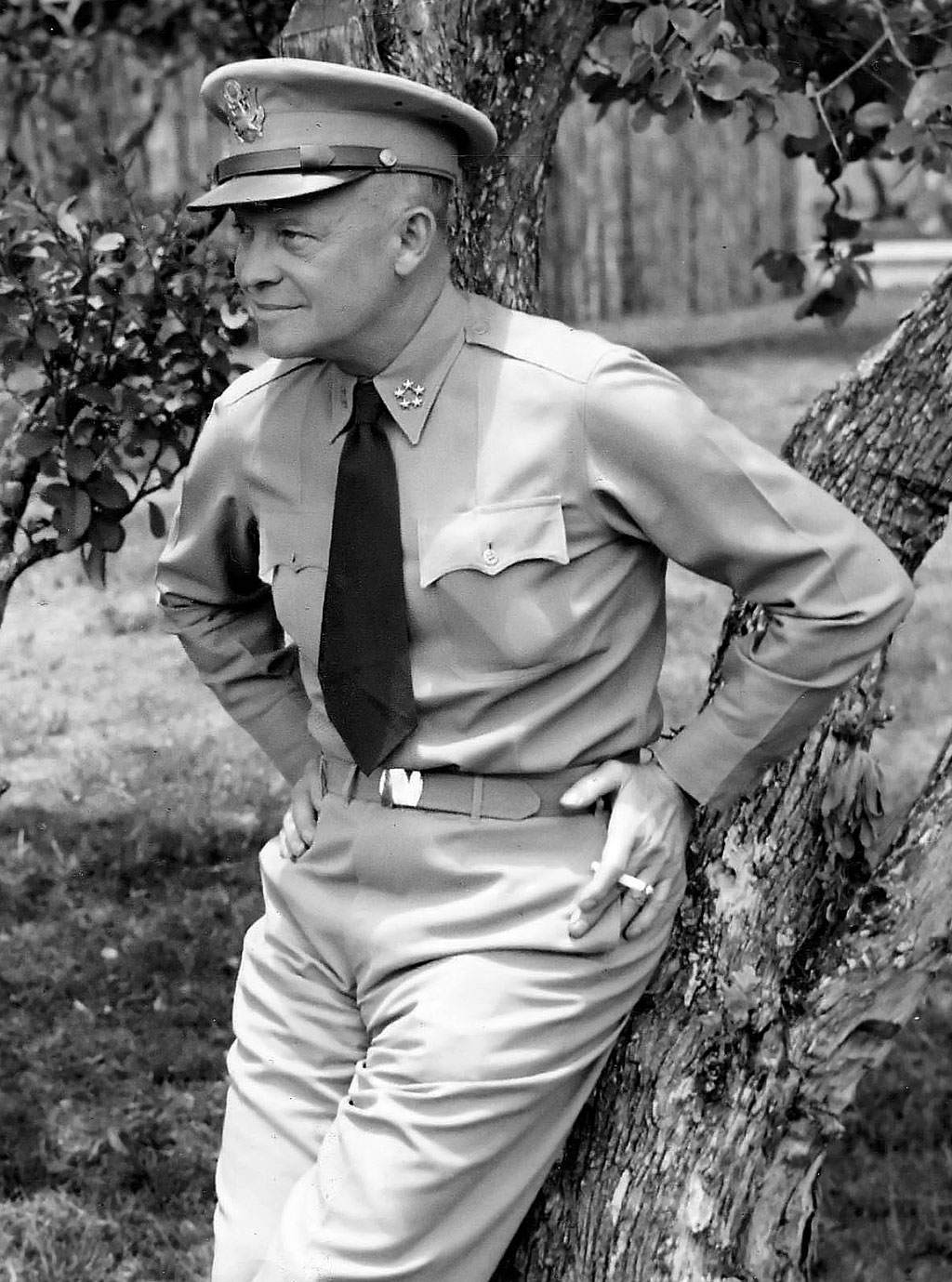

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, the

Supreme Allied Commander

Supreme Allied Commander is the title held by the most senior commander within certain multinational military alliances. It originated as a term used by the Allies during World War I, and is currently used only within NATO for Supreme Allied Co ...

, and Patton as being a corps commander of extraordinary abilities. Middleton logged 480 days in combat during World War II, more than any other American

general officer

A general officer is an Officer (armed forces), officer of high rank in the army, armies, and in some nations' air force, air and space forces, marines or naval infantry.

In some usages, the term "general officer" refers to a rank above colone ...

. Retiring from the army again in 1945, Middleton returned to LSU and in 1951 was appointed to the university presidency, a position he held for 11 years, while continuing to serve the army in numerous consultative capacities. He resided in

Baton Rouge, Louisiana

Baton Rouge ( ; , ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It had a population of 227,470 at the 2020 United States census, making it List of municipalities in Louisiana, Louisiana's second-m ...

, until his death in 1976 and was buried in

Baton Rouge National Cemetery

Baton Rouge National Cemetery is a United States National Cemetery located in East Baton Rouge Parish, in the city of Baton Rouge, Louisiana. It encompasses , and as of 2020, had over 5,000 interments.

The cemetery was added to the National Reg ...

. The library at Louisiana State University had been named for him, but in 2020, the LSU Board of Supervisors unanimously voted to remove his name due to his segregationist policies.

Family and early life

Ancestry

Troy H. Middleton was born near

Georgetown, Mississippi

Georgetown is a town in Copiah County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 286 at the 2010 census. With its eastern border formed by the Pearl River, it is part of the Jackson Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Two sites near Georgetow ...

, on 12 October 1889, the son of John Houston Middleton and Laura Catherine "Kate" Thompson.

[Price, 4–5] His paternal grandfather, Benjamin Parks Middleton, served as a private in the Mississippi Infantry for the

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army (CSA), also called the Confederate army or the Southern army, was the Military forces of the Confederate States, military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) duri ...

during the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861May 26, 1865; also known by Names of the American Civil War, other names) was a civil war in the United States between the Union (American Civil War), Union ("the North") and the Confederate States of A ...

, and his maternal grandfather, Riden M. Thompson, was also a

Confederate soldier.

His great-great-grandfather, Captain Holland Middleton, served from

Georgia

Georgia most commonly refers to:

* Georgia (country), a country in the South Caucasus

* Georgia (U.S. state), a state in the southeastern United States

Georgia may also refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Georgia (name), a list of pe ...

in the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was the armed conflict that comprised the final eight years of the broader American Revolution, in which Am ...

.

Holland Middleton was the son of William Middleton and grandson of Robert Middleton, who had extensive land interests in

Charles County

Charles County is a county located in the U.S. state of Maryland. As of the 2020 United States census, the population was 166,617. The county seat is La Plata. The county was named for Charles Calvert (1637–1715), third Baron Baltimore. The ...

and

Prince George's County

Prince George's County (often shortened to PG County or PG) is located in the U.S. state of Maryland bordering the eastern portion of Washington, D.C. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the population was 967,201, making it the second-most populous ...

in

Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It borders the states of Virginia to its south, West Virginia to its west, Pennsylvania to its north, and Delaware to its east ...

.

In 1678 Robert Middleton was paid for expenses incurred in fighting the

Nanticoke Indians and in 1681 he was commissioned as

cornet

The cornet (, ) is a brass instrument similar to the trumpet but distinguished from it by its conical bore, more compact shape, and mellower tone quality. The most common cornet is a transposing instrument in B. There is also a soprano cor ...

(second lieutenant) in a troop of

cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

.

Early life

Troy Middleton was the fifth of nine children and grew up on a 400-acre

plantation

Plantations are farms specializing in cash crops, usually mainly planting a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Plantations, centered on a plantation house, grow crops including cotton, cannabis, tob ...

in southeastern Copiah County.

[Price, 5] The plantation was virtually a self-contained community, and he had a variety of chores to do depending on the season, with sausage-stuffing being one of his favorites. The local Lick Creek and

Strong River

The Strong River is a U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map accessed June 13, 2011 river in south-central Mississippi in the United States. It is a tributary of the Pearl River, which ...

had plentiful fish that he would catch, and he loved to hunt, particularly with his

12-gauge

The gauge (in American English or more commonly referred to as bore in British English) of a firearm is a unit of measurement used to express the inner diameter (bore diameter) and other necessary parameters to define in general a smoothbore barr ...

shotgun

A shotgun (also known as a scattergun, peppergun, or historically as a fowling piece) is a long gun, long-barreled firearm designed to shoot a straight-walled cartridge (firearms), cartridge known as a shotshell, which discharges numerous small ...

.

[Price, 7] While his family was

Episcopal

Episcopal may refer to:

*Of or relating to a bishop, an overseer in the Christian church

*Episcopate, the see of a bishop – a diocese

*Episcopal Church (disambiguation), any church with "Episcopal" in its name

** Episcopal Church (United States ...

by heritage, they worshiped at the Bethel

Baptist

Baptists are a Christian denomination, denomination within Protestant Christianity distinguished by baptizing only professing Christian believers (believer's baptism) and doing so by complete Immersion baptism, immersion. Baptist churches ge ...

Church, a few miles west of Georgetown, the only church reachable on a Sunday morning.

[Price, 6] His education was conducted at the small Bethel schoolhouse, but in the summertime he was tutored by his oldest sister Emily, who came home from

Blue Mountain College

Blue Mountain Christian University (BMCU), formerly Blue Mountain College, is a private Baptist college in Blue Mountain, Mississippi. Founded as a women's college in 1873, the college's board of trustees voted unanimously for the college to ...

to share her knowledge with her family.

[Price, 11] Having exhausted all the educational opportunities available at home, Middleton's father asked him if he was interested in a college education. Finding this an attractive proposition, in the summer of 1904, at the age of fourteen, Middleton made the 172-mile train trip to

Starkville, where he would begin his studies at Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College (Mississippi A&M, later

Mississippi State University

Mississippi State University for Agriculture and Applied Science, commonly known as Mississippi State University (MSU), is a Public university, public land-grant university, land-grant research university in Mississippi State, Mississippi, Un ...

).

[Price, 12–13]

College at Mississippi A&M

At his young age, Middleton was required to complete a year of preparatory school before being enrolled in the four-year program at Mississippi A&M. In essence he did a final year of high school while living in the dormitory and following the regimen of the students at the college.

[Price, 14–15] The students were treated like cadets at a military academy, marching to and from all meals, and beginning their day with the first bugle call at 5:30 a.m. While Middleton did not particularly savor the military atmosphere, he settled into the routine, and the year passed quickly.

[Price, 16–17] The highlight of his preparatory year came on 10 February 1905 when

John Philip Sousa

John Philip Sousa ( , ; November 6, 1854 – March 6, 1932) was an American composer and conductor of the late Romantic music, Romantic era known primarily for American military March (music), marches. He is known as "The March King" or th ...

brought his band to A&M, attracting people from around the state, and packing the 2000-seat mess hall. The train that would take the band to its next stop was held up for over an hour as the concert was extended by repeated calls for encores.

[Price, 18]

The student corps at A&M was organized into a battalion, with a size of about 350 cadets during Middleton's first year. He began as a cadet corporal, and by his junior year was appointed as the cadet sergeant major. As a senior he had the cadet rank of lieutenant colonel and was the student commander of more than 700 cadets, in two battalions. Working with the military officer in charge of the cadets, Middleton took on additional responsibilities for which he was paid $25 per month.

[Price, 21–23]

Middleton was involved in numerous activities during his college days, and took leadership roles in most of them. He was the vice president of A&M's Collegian Club, and president of the school's Gun Club, being photographed on one occasion with his beloved shotgun, which he was allowed to keep in his dormitory room and use for hunting on weekends.

[Price, 24–25] He was the president of his junior class and during his senior year was the commandant of the select Mississippi Sabre Company, which was restricted to seniors of good social, academic and military standing. Among his favorite activities were baseball and football, and he played both sports throughout college, although he had to give up a season of baseball when he failed a chemistry course. Whether playing or spectating, the baseball and football games gave the students a chance to leave campus, and they took the train to play teams around the state.

[Price, 25–32]

Middleton graduated with a bachelor's degree in the spring of 1909, and was hoping to get an appointment to the

United States Military Academy

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

at

West Point

The United States Military Academy (USMA), commonly known as West Point, is a United States service academies, United States service academy in West Point, New York that educates cadets for service as Officer_(armed_forces)#United_States, comm ...

. No such opportunity presented itself, however, and at the age of 19 he was too young to take the examination for an army commission. Taking the advice of an army officer at A&M, he decided to enlist in the

United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the primary Land warfare, land service branch of the United States Department of Defense. It is designated as the Army of the United States in the United States Constitution.Article II, section 2, clause 1 of th ...

.

[Price, 33]

Early service in the U.S. Army

Enlisted service

On 3 March 1910 Troy Middleton enlisted into the 29th Infantry Regiment at

Fort Porter in

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is a Administrative divisions of New York (state), city in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York and county seat of Erie County, New York, Erie County. It lies in Western New York at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of ...

.

He was put to work as a company clerk, and as a

private

Private or privates may refer to:

Music

* "In Private", by Dusty Springfield from the 1990 album ''Reputation''

* Private (band), a Denmark-based band

* "Private" (Ryōko Hirosue song), from the 1999 album ''Private'', written and also recorded ...

earned $15 a month, which was paid in gold until it became scarce, and was then paid in silver.

[Price, 34] Middleton tired of this desk work quickly and asked to become a

soldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a Conscription, conscripted or volunteer Enlisted rank, enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, a warrant officer, or an Officer (armed forces), officer.

Etymology

The wo ...

. While this did not happen at Fort Porter, his talents as a

football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kick (football), kicking a football (ball), ball to score a goal (sports), goal. Unqualified, football (word), the word ''football'' generally means the form of football t ...

player became known, and he was pressed into duty as the

quarterback

The quarterback (QB) is a position in gridiron football who are members of the offensive side of the ball and mostly line up directly behind the Lineman (football), offensive line. In modern American football, the quarterback is usually consider ...

of the local team, which played civilian teams in the Buffalo area as well as other army teams.

[Price, 35] For the next several years Middleton would play a lot of football, a sport that was strongly endorsed by the army. After getting a commission, an officer is never returned to the same unit from which he served as an enlisted member, but Middleton became the exception because of his talents as a quarterback. Middleton felt that football provided him with the finest training he received while in the army, and he said he never met a good football player who was not also a good soldier.

Officer's commission

After 27 months of service, Middleton got his first promotion, to

corporal

Corporal is a military rank in use by the armed forces of many countries. It is also a police rank in some police services. The rank is usually the lowest ranking non-commissioned officer. In some militaries, the rank of corporal nominally corr ...

.

[Price, 36] Promotions came very slowly, and occurred only when a position was vacated by someone else getting promoted or retiring. Shortly after his promotion on 10 June 1912, Corporal Middleton was transferred to

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas, where he would have a chance to compete for an army commission. Here Middleton attended an intensive training course to prepare for the written examination required for a

second lieutenant's commission.

Of the 300 civilians and enlisted men who took the exam, 56 of them passed and were commissioned. Middleton's score was just about in the middle of the passing scores. Almost all of those passing were college graduates, coming from schools such as

Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher lear ...

,

Yale

Yale University is a private Ivy League research university in New Haven, Connecticut, United States. Founded in 1701, Yale is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States, and one of the nine colonial colleges ch ...

,

Virginia Military Institute

The Virginia Military Institute (VMI) is a public senior military college in Lexington, Virginia, United States. It was founded in 1839 as America's first state military college and is the oldest public senior military college in the U.S. In k ...

, and

Stanford

Leland Stanford Junior University, commonly referred to as Stanford University, is a private research university in Stanford, California, United States. It was founded in 1885 by railroad magnate Leland Stanford (the eighth governor of and th ...

. Four of the 56, including Middleton, would go on to become general officers.

In addition to taking the written exam, all of the applicants had to take a horse-riding test as well. Having grown up riding horses on his family's plantation, Middleton scored very well on this exam, and the officer in charge thought that he would want to go into the

cavalry

Historically, cavalry (from the French word ''cavalerie'', itself derived from ''cheval'' meaning "horse") are groups of soldiers or warriors who Horses in warfare, fight mounted on horseback. Until the 20th century, cavalry were the most mob ...

. Middleton, however, wanted to go into the infantry, leaving the officer stunned that anyone with such horsemanship skills would even consider spending his time walking.

[Price, 37]

Having passed his exam, Middleton was recommended for a commission by

President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

* President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film and television

*'' Præsident ...

Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) served as the 27th president of the United States from 1909 to 1913 and the tenth chief justice of the United States from 1921 to 1930. He is the only person to have held both offices. ...

in November 1912, but it was not until after the new president,

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

, was sworn in the following March, and the new congress convened, that the 56 successful candidates were confirmed by the Senate. Their appointment was back-dated to 30 November 1912. During this interim period, Middleton was transferred to

Fort Crockett

Fort Crockett is a government reservation on Galveston Island overlooking

the Gulf of Mexico originally built as a defense installation to protect the city and harbor of Galveston and to secure the entrance to Galveston Bay,

thus protecting the c ...

in

Galveston

Galveston ( ) is a Gulf Coast of the United States, coastal resort town, resort city and port off the Southeast Texas coast on Galveston Island and Pelican Island (Texas), Pelican Island in the U.S. state of Texas. The community of , with a pop ...

, Texas, where he arrived early in 1913.

[Price, 37–38]

Fort Crockett and deployment to Mexico

In February 1913 Troy Middleton reported to

Fort Crockett

Fort Crockett is a government reservation on Galveston Island overlooking

the Gulf of Mexico originally built as a defense installation to protect the city and harbor of Galveston and to secure the entrance to Galveston Bay,

thus protecting the c ...

as a second lieutenant without a commission, being assigned to Company K of the

7th Infantry Regiment. A large part of the United States Army was rotating here in response to trouble in Mexico.

[Price, 44] In 1910 Mexico's President

Porfirio Diaz Porfirio is a given name in Portuguese and Spanish, derived from the Greek Porphyry (''porphyrios'' "purple-clad").

It can refer to:

* Porfirio Salinas – Mexican-American artist

* Porfirio Armando Betancourt – Honduran football player

* ...

was overthrown by a reform leader,

Francisco Madero

Francisco Ignacio Madero González (; 30 October 1873 – 22 February 1913) was a Mexican businessman, revolutionary, writer and Public figure, statesman, who served as the 37th president of Mexico from 1911 until he was deposed in Ten Tragic ...

, beginning the

Mexican Revolution

The Mexican Revolution () was an extended sequence of armed regional conflicts in Mexico from 20 November 1910 to 1 December 1920. It has been called "the defining event of modern Mexican history". It saw the destruction of the Federal Army, its ...

which would last for nearly a decade. Madero was supported by General

Victoriano Huerta

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez (; 23 December 1850 – 13 January 1916) was a Mexican general, politician, engineer and dictator who was the 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of ...

in putting down a series of revolts in 1912, but the following year was assassinated by the General, who then seized power. Though many countries recognized the Huerta government, President

Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only History of the Democratic Party (United States), Democrat to serve as president during the Prog ...

would not, and he hoped to return Mexico to a constitutional government by backing

Venustiano Carranza

José Venustiano Carranza de la Garza (; 29 December 1859 – 21 May 1920), known as Venustiano Carranza, was a Mexican land owner and politician who served as President of Mexico from 1917 until his assassination in 1920, during the Mexican Re ...

. The troops at Fort Crockett went into a waiting mode, preparing for the call from the President to take action in support of American interests.

In April 1914 the waiting for the military units ended, and American troops under the command of Brigadier General

Frederick Funston

Frederick Funston (November 9, 1865 – February 19, 1917), also known as Fighting Fred Funston, was a General officer, general in the United States Army, best known for his roles in the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American ...

were sent into Mexico. The

Navy

A navy, naval force, military maritime fleet, war navy, or maritime force is the military branch, branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral z ...

had taken the port city of

Veracruz

Veracruz, formally Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, officially the Free and Sovereign State of Veracruz de Ignacio de la Llave, is one of the 31 states which, along with Mexico City, comprise the 32 Political divisions of Mexico, Federal Entit ...

and the 7th Regiment was ordered to take part in the occupation of the city. Middleton's landing party went in unopposed and settled into

occupation duty without a shot being fired. Middleton spent a total of seven months in Mexico and returned home to Galveston in November 1914.

Marriage

After arriving at Fort Crockett, Middleton adapted to garrison life and attended Saturday night dances in town. At one such dance he had a navy lieutenant introduce him to Jerusha Collins, who would later become his wife. She had attended

Southwestern University

Southwestern University (Southwestern or SU) is a Private college, private Liberal arts colleges in the United States, liberal arts college in Georgetown, Texas. Formed in 1873 from a revival of collegiate charters granted in 1840, Southwester ...

in

Georgetown, Texas

Georgetown is a city in Texas and the county seat of Williamson County, Texas, United States. The population was 67,176 at the 2020 census, and according to 2024 census estimates, the city is estimated to have a population of 101,344. It is no ...

, and had made her debut in Galveston society in 1911. Following the death of her father, Sidney G. Collins, Jerusha had come to live with her aunt and uncle, Mr. and Mrs. John Hagemann, in Galveston. As a merchant, Hagemann was well to do. Middleton met the Hagemanns, soon becoming a regular visitor at their house while calling on Jerusha.

[Price, 45]

Following seven months in Mexico, Middleton's return to Galveston brought a special anticipation. He had proposed to Jerusha Collins at an earlier time, and renewed the proposal upon his return. The couple was married on 6 January 1915, and this allowed them to be in

New Orleans

New Orleans (commonly known as NOLA or The Big Easy among other nicknames) is a Consolidated city-county, consolidated city-parish located along the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Louisiana. With a population of 383,997 at the 2020 ...

two days later with other members of Middleton's unit for the one hundredth anniversary of the

Battle of New Orleans

The Battle of New Orleans was fought on January 8, 1815, between the British Army under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham and the United States Army under Brevet Major General Andrew Jackson, roughly 5 miles (8 km) southeast of the Frenc ...

in which the 7th Regiment had served. After a week in New Orleans, the couple returned to Galveston, and were invited to move into the Hagemann's house, where they were given a large upstairs room.

[Price, 52]

Fort Bliss

When Galveston's second major

hurricane

A tropical cyclone is a rapidly rotating storm system with a low-pressure area, a closed low-level atmospheric circulation, strong winds, and a spiral arrangement of thunderstorms that produce heavy rain and squalls. Depending on its ...

hit the Texas coastline in mid-August 1915, most of the Army units had scattered to safe locations away from the storm's path, with a few units remaining in the secure buildings of Fort Crockett or in downtown Galveston. The Middletons chose to ride out the storm at the Hagemann house. Following the storm cleanup, in October 1915, the 7th Regiment was ordered to

Fort Bliss

Fort Bliss is a United States Army post in New Mexico and Texas, with its headquarters in El Paso, Texas. Established in 1848, the fort was renamed in 1854 to honor William Wallace Smith Bliss, Bvt.Lieut.Colonel William W.S. Bliss (1815–1853 ...

in

El Paso

El Paso (; ; or ) is a city in and the county seat of El Paso County, Texas, United States. The 2020 United States census, 2020 population of the city from the United States Census Bureau, U.S. Census Bureau was 678,815, making it the List of ...

, Texas as events in Mexico flared up again. Here they were put under the command of

Brigadier General John Pershing

General of the Armies John Joseph Pershing (September 13, 1860 – July 15, 1948), nicknamed "Black Jack", was an American army general, educator, and founder of the Pershing Rifles. He served as the commander of the American Expeditionary Forc ...

, a highly capable officer who had skipped three ranks by being promoted from captain to brigadier general for his exceptional service during the

Philippine–American War

The Philippine–American War, known alternatively as the Philippine Insurrection, Filipino–American War, or Tagalog Insurgency, emerged following the conclusion of the Spanish–American War in December 1898 when the United States annexed th ...

.

[Price, 54]

The Mexican Revolutionary General

Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa ( , , ; born José Doroteo Arango Arámbula; 5 June 1878 – 20 July 1923) was a Mexican revolutionary and prominent figure in the Mexican Revolution. He was a key figure in the revolutionary movement that forced ...

, who had at one time been supported by the United States, felt betrayed when the Americans backed Carranza. In January 1916, Villa's followers, known as Villistas, attacked a train and killed 16 American businessmen. Two months later Villa's men crossed the border into the United States and attacked the town of

Columbus, New Mexico

Columbus is an incorporated village in Luna County, New Mexico, United States, about north of the Mexican border. It is considered a place of historical interest, as the scene of a 1916 attack by Mexican general Francisco "Pancho" Villa that ...

, killing an additional 19 Americans. Following these attacks, General Pershing took his forces into Mexico to pursue Pancho Villa.

Preceding these events, Middleton's 7th Regiment was sent to

Camp Harry J. Jones

Camp Harry J. Jones was an encampment of the United States Army. Located near Douglas, Arizona, it was active during the Pancho Villa Expedition and World War I.

History

The United States Army established a camp near Douglas, Arizona in 1910, o ...

near

Douglas, Arizona

Douglas is a city in Cochise County, Arizona, United States, that lies in the north-west to south-east running Sulphur Springs Valley. Douglas has a Douglas, Arizona Port of Entry, border crossing with Mexico at Agua Prieta and a history of min ...

to perform border security.

[Price, 55] While there, Middleton and a squad of his men were fired upon by the Villistas who

unsuccessfully attacked the Mexican village of Agua Prieta, across the border from Douglas.

While several of Middleton's men were hit, no one was killed, and they all returned with the 7th Regiment back to Fort Bliss in late December 1915.

[Price, 56]

Preparation for war

The hunt for Pancho Villa ended unsuccessfully for the Americans. War was raging in Europe, and following several months in Mexico, Pershing was called back to Fort Bliss to begin preparing his troops for this much larger conflict. In April 1917, President Wilson requested that

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

declare war, which they did. The same month Middleton was assigned to

Gettysburg National Park

The Gettysburg National Military Park protects and interprets the landscape of the Battle of Gettysburg, fought over three days between July 1 and July 3, 1863, during the American Civil War. The park, in the Gettysburg, Pennsylvania area, is m ...

where the 7th Regiment would continue its training. Here, he was promoted to

first lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a se ...

on 1 July 1916, after a little more than three and a half years as a second lieutenant.

[Price, 58] With the pending war, his promotions would become much more frequent, and in less than a year he was promoted to

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader or highest rank officer of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police depa ...

, on 15 May 1917, over a month after the

American entry into World War I

The United States entered into World War I on 6 April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began in Europe. Apart from an Anglophile element urging early support for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, British and an a ...

.

World War I

In preparation for its buildup in strength, the army had to train a large cadre of officers. On 10 June 1917 Middleton was assigned to

Fort Myer

Fort Myer is the previous name used for a U.S. Army Military base, post next to Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington County, Virginia, and across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. Founded during the American Civil War as Fort Cass and ...

, Virginia, as the

adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an Officer (armed forces), officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of “human resources” in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed ...

of a reserve officer training camp. These camps were organized to take civilians and turn them into officers in ninety days, and as adjutant Middleton was responsible for directing the flow of paperwork for 2,700 officer candidates. By November 1917, his camp graduated its last class of officers, and Middleton requested to join a combat division. His request was granted and on 21 December 1917 he reported to the

4th Division In military terms, 4th Division may refer to:

Infantry divisions

*4th (Quetta) Division, British Indian Army

* 4th Alpine Division Cuneense, Italy

* 4th Blackshirt Division (3 January), Italy

*4th Canadian Division

*4th Division (Australia)

* 4th ...

at

Camp Greene

Camp Greene was a United States Army facility in Charlotte, North Carolina, United States, during the early 20th century. In 1917, both the 3rd Infantry Division (United States), 3rd Infantry Division and the 4th Infantry Division (United States) ...

near

Charlotte, North Carolina. Two days later, however, he received new orders to become the commander of a reserve officer training camp in

Leon Springs, Texas

Leon Springs is an unincorporated community in Bexar County, Texas, United States, now partially within the city limits of San Antonio. According to the Handbook of Texas, the community had a population of 137 in 2000. It is located within t ...

. Here, he reported as ordered, and stayed until the mission was complete in April 1918. As he was technically on loan from the 4th Division, his request to rejoin that unit was granted, and Middleton was soon on his way to France.

[Price, 59]

Believing that the 4th Division was still at Camp Greene, Middleton wired there to find out that the unit was already on its way overseas. He caught a train for New York, and when he arrived on 28 April 1918, he found his division at

Camp Mills

Camp Albert L. Mills (Camp Mills) was a military installation on Long Island, New York (state), New York. It was located about ten miles from the eastern boundary of New York City on the Hempstead Plains within what is now the village of Garden Ci ...

on

Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated continental island in southeastern New York (state), New York state, extending into the Atlantic Ocean. It constitutes a significant share of the New York metropolitan area in both population and land are ...

, living in tents and awaiting transport. Middleton was given command of the First Battalion,

47th Infantry Regiment, and departed New York with his regiment aboard the ''Princess Matokia'' on 11 May in a convoy of fourteen ships. Three days out of France, a fleet of destroyers met the convoy and escorted it to the port city of

Brest where they arrived on 23 May. There the division unloaded and organized for several days, subsequently loading onto a troop train to arrive at

Calais

Calais ( , , traditionally , ) is a French port city in the Pas-de-Calais department, of which it is a subprefecture. Calais is the largest city in Pas-de-Calais. The population of the city proper is 67,544; that of the urban area is 144,6 ...

on 30 May.

[Price, 61–62]

Calais, Chateau Thierry and Saint-Mihiel

The first assignment of the 4th Division was to become a reserve unit for the British, just south of Calais. The Americans gave up their

Springfield Rifles for some British

Enfields for which there was available ammunition. When the

Germans

Germans (, ) are the natives or inhabitants of Germany, or sometimes more broadly any people who are of German descent or native speakers of the German language. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany, constitution of Germany, imple ...

began an offensive north of

Paris

Paris () is the Capital city, capital and List of communes in France with over 20,000 inhabitants, largest city of France. With an estimated population of 2,048,472 residents in January 2025 in an area of more than , Paris is the List of ci ...

, the 4th was put onto trains and sent to the

Marne River

The Marne (; ) is a river in France, an eastern tributary of the Seine in the area east and southeast of Paris. It is long. The river gave its name to the departments of France, departments of Haute-Marne, Marne (department), Marne, Seine-et-Ma ...

, about twenty-five miles west of

Chateau Thierry. Here the 4th became a reserve unit for the badly battered

42nd Division.

[Price, 62] In late July 1918, Middleton, promoted to

major

Major most commonly refers to:

* Major (rank), a military rank

* Academic major, an academic discipline to which an undergraduate student formally commits

* People named Major, including given names, surnames, nicknames

* Major and minor in musi ...

on 7 June, moved his First Battalion in to support the 167th Regiment of the 42nd Division. In the ensuing operation, called the

Second Battle of the Marne, four days of heavy fighting took place against the

Prussian

Prussia (; ; Old Prussian: ''Prūsija'') was a German state centred on the North European Plain that originated from the 1525 secularization of the Prussian part of the State of the Teutonic Order. For centuries, the House of Hohenzoll ...

Fourth Guard Division fresh from a month's rest. While the veteran Germans fought with determination, the Americans were able to push them back about twelve miles, though at a considerable cost—more than one in four of the Americans became casualties.

[Price, 63–66]

When the 4th Division was relieved, they were sent to the

Saint-Mihiel

Saint-Mihiel () is a commune in the Meuse department in the Grand Est region in Northeastern France.

Geography

Saint-Mihiel lies on the banks of the river Meuse.

History

A Benedictine abbey was established here in 708 or 709 by Count Wulfoalde ...

area, where they would undertake a small support role. Major Middleton was given the task of directing the unit's transport, complicated by the requirement to move at night with equipment and personnel to be drawn by horse and mule. After Saint-Mihiel, the unit was moved to

Verdun

Verdun ( , ; ; ; official name before 1970: Verdun-sur-Meuse) is a city in the Meuse (department), Meuse departments of France, department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

In 843, the Treaty of V ...

where hundreds of thousands of French and Germans had become casualties earlier in the war. This would become the last major engagement of the First World War for Middleton, who was promoted to

lieutenant colonel on 17 September, shortly before the commencement of the operation, called the

Meuse-Argonne Offensive.

[Price, 66]

Meuse-Argonne Offensive

The 4th Division, on its own for the first time in the war, was assigned a front that was one to two miles wide, sandwiched between two seasoned French divisions, about eight miles from Verdun. Lieutenant Colonel Middleton's battalion led the attack for the Americans on 26 September 1918. That day, they covered five miles, breaking through German defenses, after which it was up to the entire 47th Infantry Regiment to hold onto the gains.

[Price, 66–67] Middleton then put his second-in-command in charge of the battalion when he was assigned as the

executive officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization.

In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer ...

of the regiment. He was in this staff position for two weeks when, on 11 October, he was given command of the

39th Infantry Regiment after commander

James K. Parsons and most of his regimental staff became casualties following a gas attack.

[Price, 67] At about one o'clock in the morning, Middleton had to find his way to the 39th headquarters and prepare for battle at daybreak. Shortly before 7:30 a.m., Middleton led his new regiment into enemy-held territory using a tactic called "marching fire," where all of the troops constantly fired their weapons while moving a mile through heavy woods. This compelled most of the dug-in and concealed Germans to surrender, and allowed the 4th Division to move to the edge of the

Meuse River

The Meuse or Maas is a major European river, rising in France and flowing through Belgium and the Netherlands before draining into the North Sea from the Rhine–Meuse–Scheldt delta. It has a total length of .

History

From 1301, the upp ...

.

[Price, 68] Three days after taking command of the 39th, and two days after his twenty-ninth birthday, Middleton was promoted to

colonel

Colonel ( ; abbreviated as Col., Col, or COL) is a senior military Officer (armed forces), officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, a colon ...

, becoming the youngest officer in the

American Expeditionary Forces

The American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) was a formation of the United States Armed Forces on the Western Front (World War I), Western Front during World War I, composed mostly of units from the United States Army, U.S. Army. The AEF was establis ...

(AEF) to attain that rank.

He also received the

Army Distinguished Service Medal

The Distinguished Service Medal (DSM) is a military decoration of the United States Army that is presented to soldiers who have distinguished themselves by exceptionally meritorious service to the government in a duty of great responsibility. ...

for his exceptional battlefield performance.

The citation for the medal reads:

On 19 October, the 4th Division was withdrawn from the battle line after 24 days of continuous contact with the enemy, the longest unbroken period of combat for any American division during the war.

[Price, 70] Middleton was now given command of his former regiment, the 47th. In early November the 4th Division relieved an

African American

African Americans, also known as Black Americans and formerly also called Afro-Americans, are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, American racial and ethnic group that consists of Americans who have total or partial ancestry from an ...

regiment near

Metz

Metz ( , , , then ) is a city in northeast France located at the confluence of the Moselle (river), Moselle and the Seille (Moselle), Seille rivers. Metz is the Prefectures in France, prefecture of the Moselle (department), Moselle Departments ...

, and was preparing to chase German defenders down the

Moselle River

The Moselle ( , ; ; ) is a river that rises in the Vosges mountains and flows through north-eastern France and Luxembourg to western Germany. It is a left bank tributary of the Rhine, which it joins at Koblenz. A small part of Belgiu ...

, with Middleton to lead the attack. The attack did not materialize, however, because, on 10 November, Middleton received confidential news that an armistice was imminent. The following morning a messenger brought word that there would be no more firing after 11 a.m. There was celebration throughout the ranks, but there was still much work to be done; the 4th Division would soon be assigned to Germany as an occupying force.

Occupation of Germany

In late November 1918 the 4th Division began a road march of more than 125 miles from the French city of Metz toward the German city of

Koblenz

Koblenz ( , , ; Moselle Franconian language, Moselle Franconian: ''Kowelenz'') is a German city on the banks of the Rhine (Middle Rhine) and the Moselle, a multinational tributary.

Koblenz was established as a Roman Empire, Roman military p ...

, on the

Rhine River

The Rhine ( ) is one of the major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Swiss-Austrian border. From Lake Cons ...

. The final destination of Middleton's 47th Regiment would be the town of

Adenau

Adenau () is a town in the High Eifel in Germany. It is known as the ''Johanniterstadt'' because the Order of Saint John (Bailiwick of Brandenburg), Order of Saint John was based there in the Middle Ages. The town's coat of arms combines the black ...

, 35 miles due west of Koblenz. The road trip took fifteen days of moving through almost incessant rain and ended in a driving snowstorm on 15 December. Middleton rode a horse during most of each day, surveying his troops and occasionally dismounting to talk with them. The formation marched for fifty minutes of each hour, and rested for ten, with a full hour for lunch.

Once in Adenau, the regiment dispersed to many villages in the area, while Colonel Middleton stayed in a large home in Adenau where the owners continued to live as well. During the stay in Adenau, the 47th continued with its training, building a rifle range, running combat problems, and practicing lessons learned from its recent combat operations. In early March 1919, after nearly four months in Adenau, the 47th was ordered to the area of

Remagen

Remagen () is a town in Germany in the state of Rhineland-Palatinate, in the district of Ahrweiler (district), Ahrweiler. It is about a one-hour drive from Cologne, just south of Bonn, the former West Germany, West German seat of government. It i ...

on the Rhine. On the morning of the move, Middleton had breakfast with Colonel

George C. Marshall

George Catlett Marshall Jr. (31 December 1880 – 16 October 1959) was an American army officer and statesman. He rose through the United States Army to become Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army under presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. ...

, who had come to Adenau the day before to inform Middleton of his regiment's new orders. Marshall was the aide of General John Pershing, who by now was the

Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) of the AEF.

[Price, 71–73]

At Remagen the 47th Regiment was given the mission of guarding the

Ludendorff Bridge

The Ludendorff Bridge, also known as the Bridge at Remagen, was a bridge across the river Rhine in Germany which was captured by United States Army forces in early March 1945 during the Battle of Remagen, in the closing weeks of World War I ...

over the

Rhine River

The Rhine ( ) is one of the major rivers in Europe. The river begins in the Swiss canton of Graubünden in the southeastern Swiss Alps. It forms part of the Swiss-Liechtenstein border, then part of the Swiss-Austrian border. From Lake Cons ...

. Twenty five years later the 47th would once again guard this bridge during

World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

. The regiment remained here until given orders to return home in mid-summer 1919. Before his departure from Europe, Middleton was summoned to report to the Third Army Chief of Staff in Koblenz. Here he was informed that he and other senior officers were being assigned to

Camp Benning

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

, Georgia, to form the first faculty of the

Infantry School

A School of Infantry provides training in weapons and infantry tactics to infantrymen of a nation's military forces.

Schools of infantry include:

Australia

*Australian Army – School of Infantry, Lone Pine Barracks at Singleton, NSW.

Franc ...

that was being established there. Middleton sailed out of Brest in mid-July, met his wife in New York, and together they traveled to

Columbus, Georgia

Columbus is a consolidated city-county located on the west-central border of the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. Columbus lies on the Chattahoochee River directly across from Phenix City, Alabama. It is the county seat of Muscogee ...

, by way of Washington, D.C., and

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

.

[Price, 73–77]

Military schools

For the ten years following World War I, Troy Middleton would be either an instructor or a student in the succession of military schools that Army officers attend during their careers.

Middleton arrived in Columbus, Georgia with strong praise from his superiors, and would soon get his efficiency report, in which Brigadier General Benjamin Poore of the 4th Division wrote of him,

The best all-around officer I have yet seen. Unspoiled by his rapid promotion from captain in July to colonel in October; and made good in every grade. He gets better results in a quiet unobtrusive way than any officer I have ever met. Has a wonderful grasp of situations and a fine sense of proportion.[Price, 84]

Infantry School

Up until the World War, other branches of the Army had their own specialty schools, but the infantry did not. This situation was being amended, and Middleton would be part of that change as a new faculty member of the

Infantry School

A School of Infantry provides training in weapons and infantry tactics to infantrymen of a nation's military forces.

Schools of infantry include:

Australia

*Australian Army – School of Infantry, Lone Pine Barracks at Singleton, NSW.

Franc ...

at

Camp Benning

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

, about nine miles from Columbus.

[Price, 78–79] Middleton, whose rank had reverted to his permanent rank of captain following the war, was an instructor in the new school for his first two years at Benning, and also a member of the Infantry Board, set up for research on weapons and tactics. One of his jobs on the board was to evaluate new weapons and equipment, and at one point he tested a new

semiautomatic rifle

A semi-automatic rifle is a type of rifle that fires a single round each time the trigger is pulled while automatically loading the next cartridge. These rifles were developed Pre-World War II, and were used throughout World War II. Rifles ...

which would eventually become the

M-1 rifle

The M1 Garand or M1 rifleOfficially designated as U.S. rifle, caliber .30, M1, later simply called Rifle, Caliber .30, M1, also called US Rifle, Cal. .30, M1 is a semi-automatic rifle that was the service rifle of the U.S. Army during World Wa ...

, the standard weapon of the infantry in World War II.

The first nine-month class of the new infantry school began in September 1919, and students were taken through a curriculum of weapons and tactics. Captain Middleton, the youngest faculty member on the school staff, was an ideal instructor, fresh with experiences from the recent war.

[Price, 80] After two years as an instructor, and a promotion to major on 1 July 1920, Middleton prevailed upon his commanders to be allowed to enroll in the advanced infantry course as a student. This ten-month course included instruction on

combined arms

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects—for example, using infantry and armoured warfare, armour in an Urban warfare, urban environment in ...

,

tactical principles and decisions,

military history

Military history is the study of War, armed conflict in the Human history, history of humanity, and its impact on the societies, cultures and economies thereof, as well as the resulting changes to Politics, local and international relationship ...

and

economics

Economics () is a behavioral science that studies the Production (economics), production, distribution (economics), distribution, and Consumption (economics), consumption of goods and services.

Economics focuses on the behaviour and interac ...

, then ended with a written

thesis

A thesis (: theses), or dissertation (abbreviated diss.), is a document submitted in support of candidature for an academic degree or professional qualification presenting the author's research and findings.International Standard ISO 7144: D ...

. Middleton, who was one of the most junior members of his class, finished at the top of the class.

[Price, 83]

Following the advanced course, Middleton spent the summer as the senior instructor at a

Reserve Officer

A military reserve force is a military organization whose members (reservists) have military and civilian occupations. They are not normally kept under arms, and their main role is to be available when their military requires additional m ...

Training Camp at

Fort Logan

Fort Logan was a military installation located eight miles southwest of Denver, Colorado. It was established in October 1887, when the first soldiers camped on the land, and lasted until 1946, when it was closed following the end of World War II ...

, Colorado, then returned to Camp Benning for one more year as a member of the Infantry Board. Four years at Benning had been enough for him and he was ready to move on. After expressing his wishes to a senior officer, he was assigned to Fort Leavenworth in the summer of 1923.

[Price, 86–88]

Command and General Staff School

As one of the youngest majors in the army, Middleton found himself among officers who were ten to fifteen years his senior at the Army's

Command and General Staff School

The United States Army Command and General Staff College (CGSC or, obsolete, USACGSC) at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, is a graduate school for United States Army and sister service officers, interagency representatives, and international military ...

at

Fort Leavenworth

Fort Leavenworth () is a United States Army installation located in Leavenworth County, Kansas, in the city of Leavenworth, Kansas, Leavenworth. Built in 1827, it is the second oldest active United States Army post west of Washington, D.C., an ...

, Kansas. Students attended this ten-month school to qualify for higher commands.

[Price, 89] Here Middleton met a classmate,

George Patton

George Smith Patton Jr. (11 November 1885 – 21 December 1945) was a general in the United States Army who commanded the Seventh Army in the Mediterranean Theater of World War II, then the Third Army in France and Germany after the Alli ...

, who would become one of his friends. Patton had confided to Middleton that he predicted completing the course as an Honor Graduate, one who finishes in the top 25% of the nearly 200 students. His prediction came true, and he finished 14th in the class. Middleton finished 8th.

With his exceptional class performance, Middleton, along with half a dozen other graduates, was invited to stay on for the next four years as an instructor at the school.

[Price, 90]

During his second year of teaching at Command and General Staff School, one of his students,

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was the 34th president of the United States, serving from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, he was Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionar ...

, would come to his office and pump him for information, knowing that Middleton had commanded a regiment in combat in France. Eisenhower asked practical questions, and was unquestionably motivated—he finished first in his class.

[Price, 91] Nearly every officer who commanded a division in Europe during World War II attended the Command and General Staff School during Middleton's tenure there from 1924 to 1928. There was also a point in time during World War II when every corps commander in Europe had been a student of Middleton's.

War College

In 1928, his final year at Leavenworth, Middleton received orders to attend the

Army War College in Washington, D.C. His year at this highest level of professional military education was very fulfilling. He spent time in the school library and the

Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

.

[Price, 94] He wrote his staff memorandum (equivalent to a thesis) on the subject of Army transportation. Recalling his personal experience with horses and mules in France, he recommended that motorized transport significantly replace the Army's use of livestock. The

commandant

Commandant ( or ; ) is a title often given to the officer in charge of a military (or other uniformed service) training establishment or academy. This usage is common in English-speaking nations. In some countries it may be a military or police ...

of the school commended Middleton for work of exceptional merit, and sent his ideas to the highest levels in the

War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet ...

.

[Price, 94–95]

Late career

Having spent the previous ten years in the various Army schools, Major Middleton requested a return to

Camp Benning

Fort Benning (named Fort Moore from 2023–2025) is a United States Army post in the Columbus, Georgia area. Located on Georgia's border with Alabama, Fort Benning supports more than 120,000 active-duty military, family members, reserve compone ...

, where he and his wife still had friends. The request was approved and he was assigned as a battalion commander in the

29th Infantry Regiment there, the same unit in which he had enlisted nineteen years earlier at

Fort Porter.

[Price, 97–8] He was at Benning for only a year when he was told he would be assigned to the

General Staff

A military staff or general staff (also referred to as army staff, navy staff, or air staff within the individual services) is a group of officers, Enlisted rank, enlisted, and civilian staff who serve the commanding officer, commander of a ...

at the

War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet ...

in Washington D.C., but this changed when a new requirement for career officers was brought to his attention. Officers were now expected to have an assignment with a civilian component of the Army such as the

National Guard

National guard is the name used by a wide variety of current and historical uniformed organizations in different countries. The original National Guard was formed during the French Revolution around a cadre of defectors from the French Guards.

...

, the

Reserves, or the

Reserve Officers' Training Corps

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC; or ) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all branches o ...

(ROTC). The last option appealed to Middleton the most, and he wanted to work at a school in the south. There was an opening at

Louisiana State University

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as Louisiana State University (LSU), is an American Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louis ...

(LSU), and this is where Middleton soon headed.

[Price, 98]

ROTC duty at Louisiana State University

In July 1930 Troy Middleton stopped at his new headquarters at

Fort McPherson

Fort McPherson was a U.S. Army military base located in Atlanta, Georgia, bordering the northern edge of the city of East Point, Georgia. It was the headquarters for the U.S. Army Installation Management Command, Southeast Region; the U.S. Ar ...

in

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital and List of municipalities in Georgia (U.S. state), most populous city in the U.S. state of Georgia (U.S. state), Georgia. It is the county seat, seat of Fulton County, Georg ...

, then drove west with his family to

Baton Rouge

Baton Rouge ( ; , ) is the List of capitals in the United States, capital city of the U.S. state of Louisiana. It had a population of 227,470 at the 2020 United States census, making it List of municipalities in Louisiana, Louisiana's second-m ...

, Louisiana, which would become the family home for many years. Major Middleton became the Commandant of cadets at

LSU

Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, commonly referred to as Louisiana State University (LSU), is an American Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Baton Rouge, Louis ...

, along with being the professor of military science.

[Price, 99]

While at headquarters, Middleton had learned that his predecessor did not get along with Louisiana's governor,

Huey P. Long. Middleton was told a few stories about the governor that made him curious enough to call on him the day after arriving in town. While the meeting turned out to be somewhat awkward for Major Middleton, it began a friendship between the two men.

[Price, 100–1] Governor Long loved LSU and the cadet corps there. When Middleton mentioned to him that the cadet band had just a few dozen members, the governor saw to it that the band would grow to 250 members. Governor Long was a showman, and enjoyed parades and fanfare, and would negotiate special fares to get the cadets and band transported to athletic events across the region.

[Price, 105–6] Because of the governor's dealings, LSU transformed from a third rate school in 1930 to the largest university in the south by 1936.

During Middleton's tenure at LSU the presidency of the university changed hands from President Atkinson to President James Monroe Smith, the latter an appointee of Governor Long. Towards the end of Middleton's fourth year on campus President Smith asked him if he would stay on for an additional year and also become

Dean of Men. Middleton responded that he would accept, but it had to be cleared through the

War Department War Department may refer to:

* War Department (United Kingdom)

* United States Department of War

The United States Department of War, also called the War Department (and occasionally War Office in the early years), was the United States Cabinet ...

. Smith's request to the War Department for both the extension and the deanship for Middleton were approved. Toward the end of the fifth year Smith went a step further, suggesting that Middleton retire from the army and become a permanent member of the LSU staff. Middleton would not even consider retirement, but accepted a sixth year with the

ROTC

The Reserve Officers' Training Corps (ROTC; or ) is a group of college- and university-based officer-training programs for training commissioned officers of the United States Armed Forces.

While ROTC graduate officers serve in all branches o ...

program. As he began his sixth year on campus, on 1 Aug 1935, he was promoted to

lieutenant colonel.

Early in his final year on campus, Middleton was once again pressed by the university president to retire from the army and go to work for the college. Again, Middleton could not do that, and began looking for a suitable follow-on assignment. Not having been overseas in over sixteen years, he put in a request for duty in the

Philippines

The Philippines, officially the Republic of the Philippines, is an Archipelagic state, archipelagic country in Southeast Asia. Located in the western Pacific Ocean, it consists of List of islands of the Philippines, 7,641 islands, with a tot ...

. He finished his tenure at LSU in the summer of 1936, having overseen the increase in students completing the ROTC program from about 500 to over 1700 cadets.

Philippines and retirement

In August 1936 the Middletons made a leisurely drive to

New York City