Thomas Mann on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

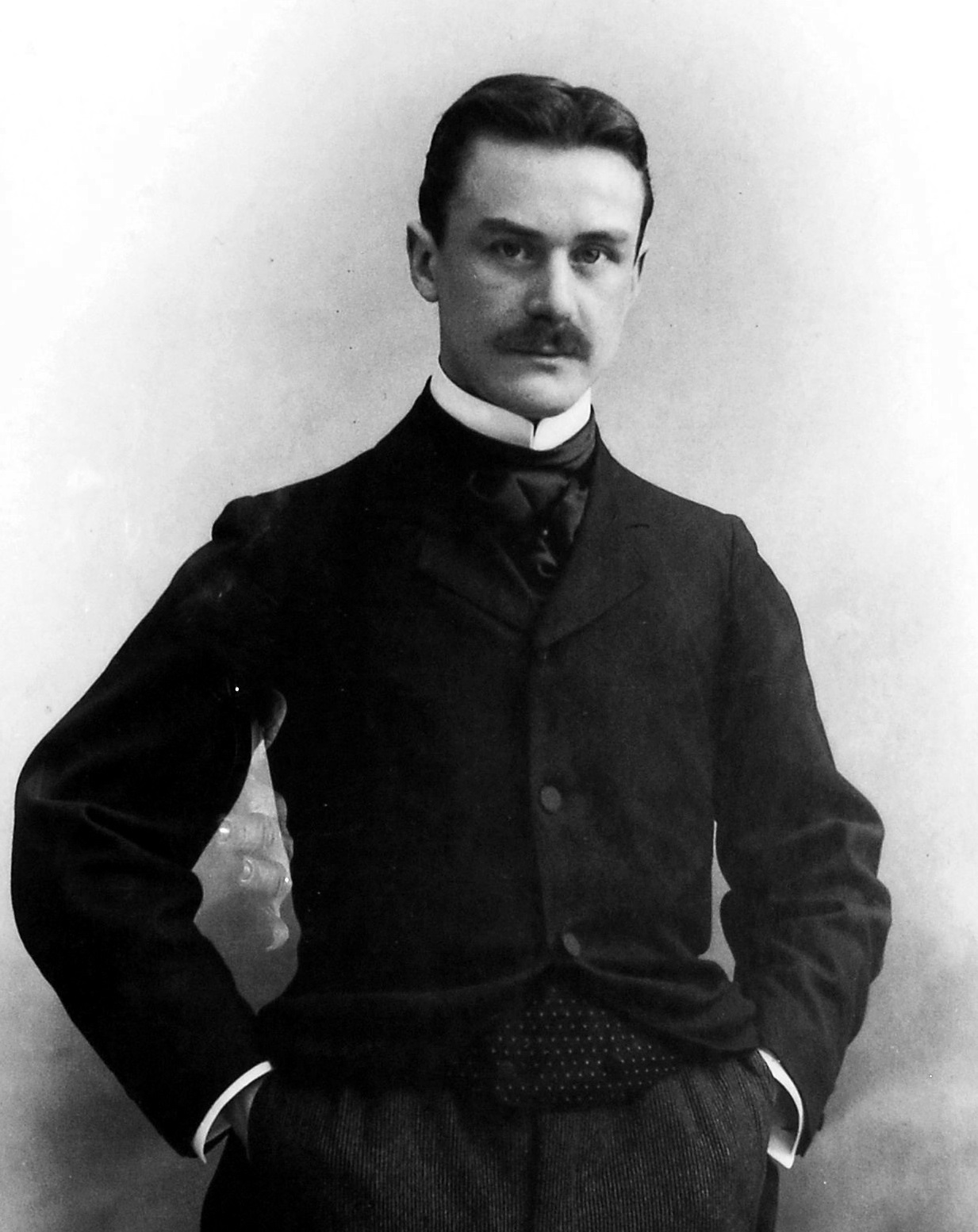

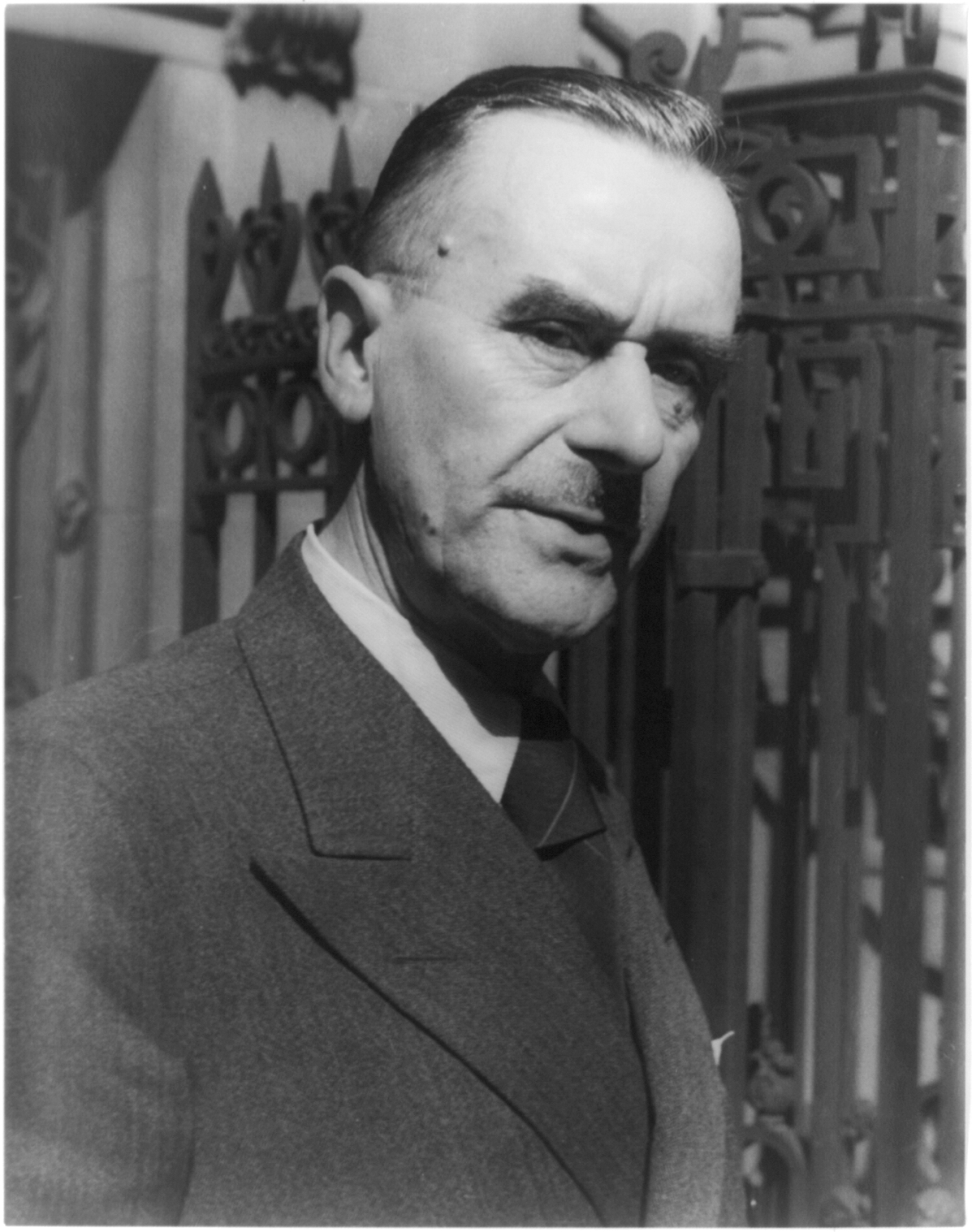

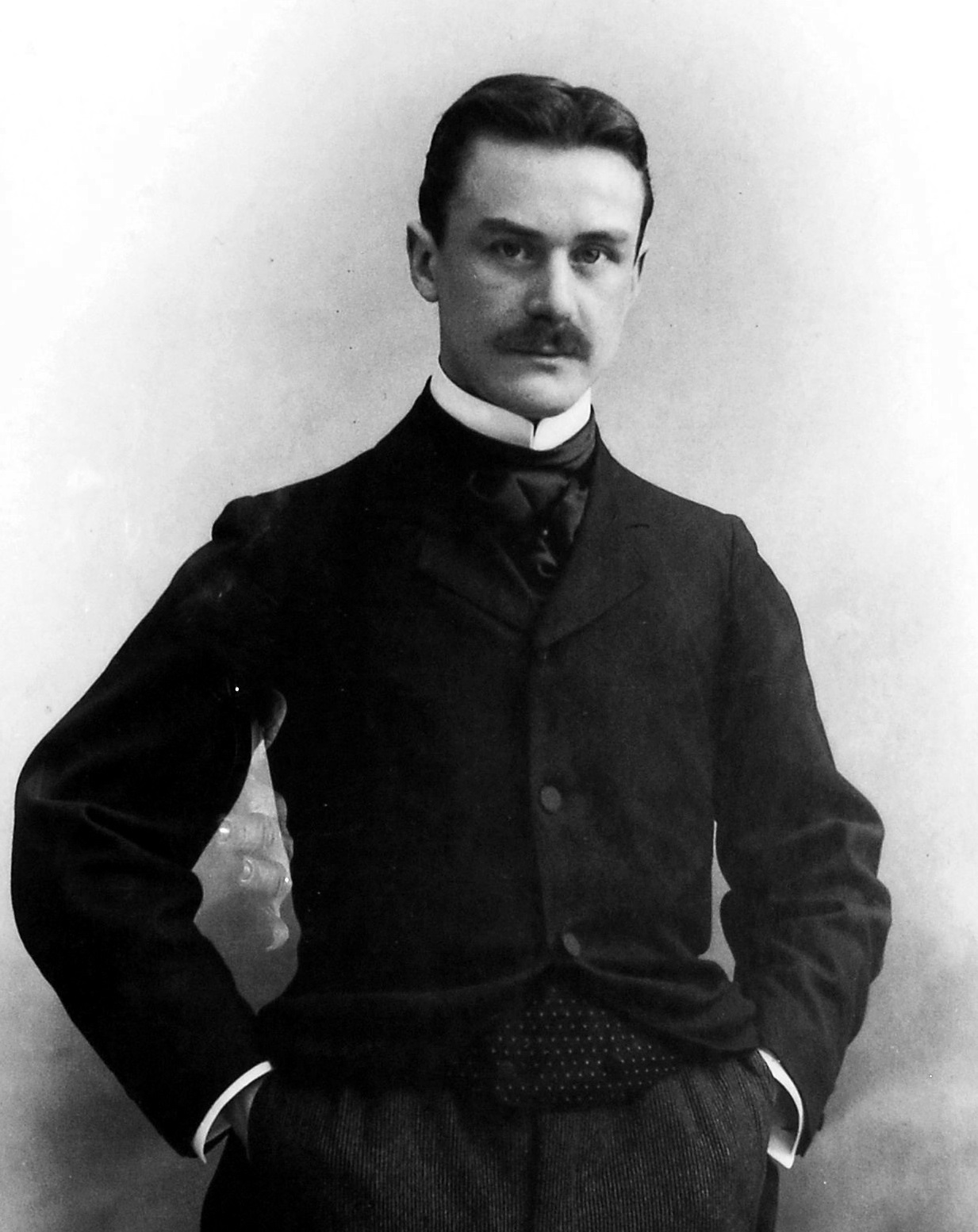

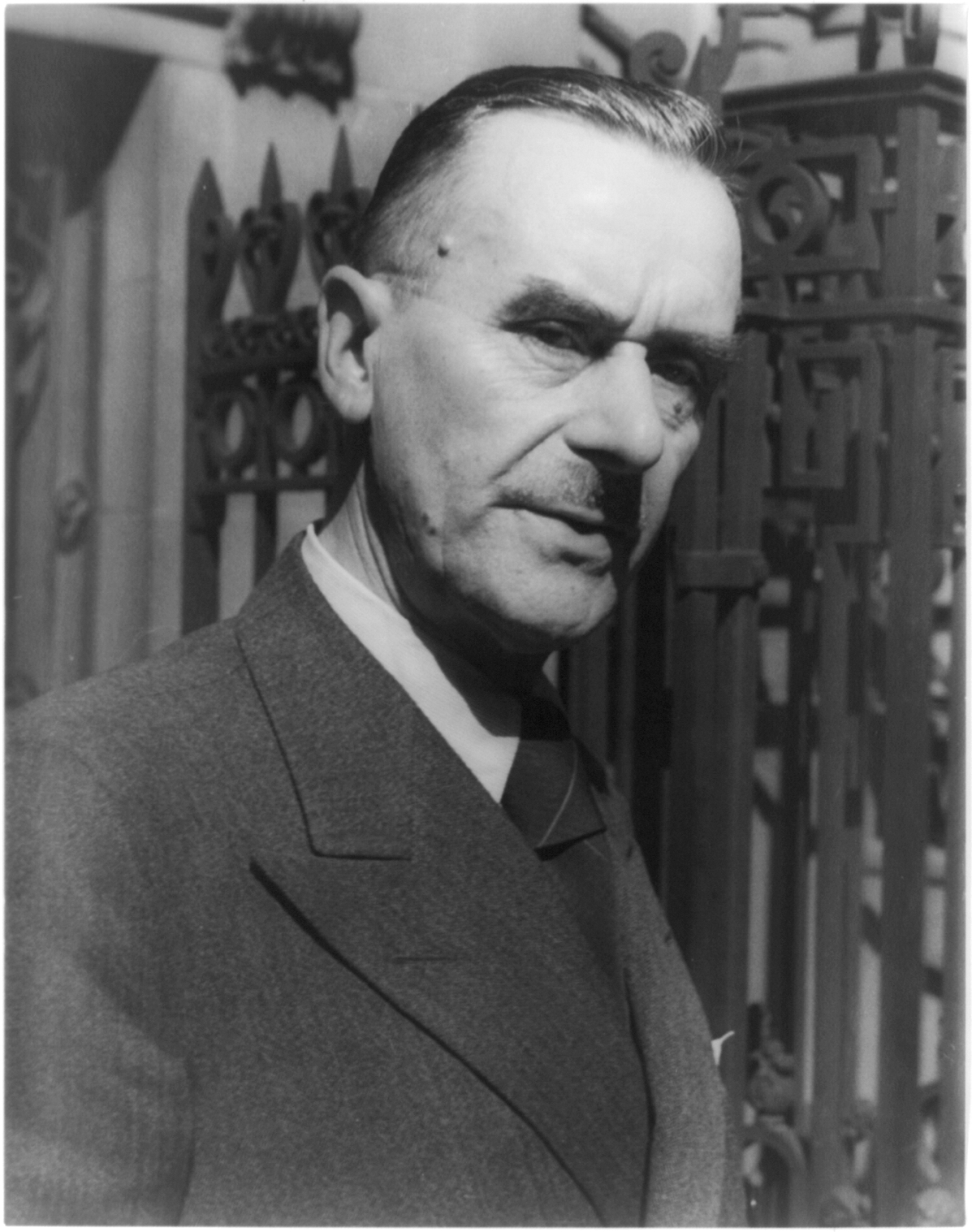

Paul Thomas Mann ( , ; ; 6 June 1875 – 12 August 1955) was a German novelist, short story writer, social critic, philanthropist, essayist, and the

Salka Viertel , Jewish Women's Archive

. Retrieved 19 November 2016. Thomas Mann's always difficult relationship with his brother Heinrich, who envied Thomas's success and wealth and also differed politically, hardly improved when the latter arrived in California, poor and sickly, in need of support. On 23 June 1944, Thomas Mann was naturalized as a citizen of the United States. The Manns lived in Los Angeles until 1952.

Reconstruction of the Thomas Mann mansion.jpg, The family lived in this villa in Munich from 1914 to 1933. Partially destroyed in World War II, it was later reconstructed.

Ehem. Villa Thomas Mann - 2022-04-22 - 147d.jpg, The family country house in

With the start of the

With the start of the

In the autobiographical novella '' Tonio Kröger'' from 1901, the young hero has a crush on a handsome male classmate (modeled after real-life Lübeck classmate Armin Martens). In the novella ''With the prophet'' (1904) Mann mocks the believing disciples of a neo-Romantic "prophet" who preaches asceticism and has a strong resemblance to the real contemporary poet

In the autobiographical novella '' Tonio Kröger'' from 1901, the young hero has a crush on a handsome male classmate (modeled after real-life Lübeck classmate Armin Martens). In the novella ''With the prophet'' (1904) Mann mocks the believing disciples of a neo-Romantic "prophet" who preaches asceticism and has a strong resemblance to the real contemporary poet

Many literary and other works make reference to ''Death in Venice'', including:

*

Many literary and other works make reference to ''Death in Venice'', including:

*

*''Hayavadana'' (1972), a play by

*''Hayavadana'' (1972), a play by

''Essays of Three Decades''

translated from the German by H. T. Lowe-Porter. st American ed. New York, A. A. Knopf, 1947. Reprinted as Vintage book, K55, New York, Vintage Books, 1957. Includes "Schopenhauer" *1948: "Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Light of Recent History" *1950: "Michelangelo according to his poems" ("Michelangelo in seinen Dichtungen") *1958: ''Last Essays''. Includes "Nietzsche's Philosophy in the Light of Recent History"

''Stories of Three Decades''

(trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter). Includes 24 stories written from 1896 to 1922. First American edition published in 1936. *1963

''Death in Venice and Seven Other Stories''

(trans. H. T. Lowe-Porter). Includes: "Death in Venice"; "Tonio Kröger"; "Mario and the Magician"; "Disorder and Early Sorrow"; "A Man and His Dog"; "The Blood of the Walsungs"; "Tristan"; "Felix Krull". *1970

''Tonio Kröger and Other Stories''

(trans. David Luke). Includes: "Little Herr Friedemann"; "The Joker"; "The Road to the Churchyard"; "Gladius Dei"; "Tristan"; "Tonio Kroger". **Republished in 1988 as "Death in Venice and Other Stories" with the addition of the eponymous story. *1997

''Six Early Stories''

(trans. Peter Constantine). Includes: "A Vision: Prose Sketch"; "Fallen"; The Will to Happiness"; "Death"; "Avenged: Study for a Novella"; "Anecdote". *1998

''Death in Venice and Other Tales''

(trans. Joachim Neugroschel). Includes: "The Will for Happiness"; "Little Herr Friedemann"; "Tobias Mindernickel"; "Little Lizzy"; "Gladius Dei"; "Tristan"; "The Starvelings: A Study"; "Tonio Kröger"; "The Wunderkind"; "Harsh Hour"; "The Blood of the Walsungs"; "Death in Venice". *1999

''Death in Venice and Other Stories''

(trans. Jefferson Chase). Includes: "Tobias Mindernickel"; "Tristan"; "Tonio Kröger"; "The Child Prodigy"; "Hour of Hardship"; "Death in Venice"; "Man and Dog". *2023: ''New Selected Stories'' (trans.

Review

by

"have come out of copyright in the US, and will do so in the UK from the start of 2026"

" own translations of ''

Thomas Mann's Profile on FamousAuthors.org

*

First prints of Thomas Mann. Collection Dr. Haack, Leipzig (Germany)

References to Thomas Mann in European historic newspapers

*

List of Works

* * Thomas Mann Collection. Yale Collection of German Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

TMI Research

b

Thomas Mann International

Cross-house research in the archive and library holdings of the network partners in Lübeck, Munich, Zurich and Los Angeles

1929 Nobel Prize in Literature

The 1929 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the German author Thomas Mann (1875–1955) "principally for his great novel, Buddenbrooks, which has won steadily increased recognition as one of the classic works of contemporary literature." He ...

laureate. His highly symbolic and ironic epic novels and novellas are noted for their insight into the psychology of the artist and the intellectual. His analysis and critique of the European and German soul used modernized versions of German and Biblical stories, as well as the ideas of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

, and Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

.

Mann was a member of the hanseatic

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

Mann family

The Mann family ( , ; ) is a German dynasty of novelists and an old Hanseaten (class), Hanseatic family of Patrician (post-Roman Europe), patricians from Free City of Lübeck, Lübeck. It is known for being the family of the Nobel Prize for Li ...

and portrayed his family and class in his first novel, ''Buddenbrooks

''Buddenbrooks'' () is a 1901 novel by Thomas Mann, chronicling the decline of a wealthy north German merchant family over the course of four generations, incidentally portraying the manner of life and mores of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie in th ...

''. His older brother was the radical writer Heinrich Mann

Luiz Heinrich Mann (; March 27, 1871 – March 11, 1950), best known as simply Heinrich Mann, was a German writer known for his sociopolitical novels. From 1930 until 1933, he was president of the fine poetry division of the Prussian Academy ...

and three of Mann's six children – Erika Mann

Erika Julia Hedwig Mann (9 November 1905 – 27 August 1969) was a German actress and writer, daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann.

Erika lived a bohemian lifestyle in Berlin and became a critic of National Socialism. After Hitler came to power ...

, Klaus Mann and Golo Mann – also became significant German writers. When Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (20 April 1889 – 30 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was the dictator of Nazi Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his suicide in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the lea ...

came to power in 1933, Mann fled to Switzerland. When World War II

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

broke out in 1939, he moved to the United States, then returned to Switzerland in 1952. Mann is one of the best-known exponents of the so-called '' Exilliteratur'', German literature

German literature () comprises those literature, literary texts written in the German language. This includes literature written in Germany, Austria, the German parts of Switzerland and Belgium, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, South Tyrol in Italy ...

written in exile by those who opposed the Hitler regime.

Life

Paul Thomas Mann was born to ahanseatic

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

family in Lübeck

Lübeck (; or ; Latin: ), officially the Hanseatic League, Hanseatic City of Lübeck (), is a city in Northern Germany. With around 220,000 inhabitants, it is the second-largest city on the German Baltic Sea, Baltic coast and the second-larg ...

, the second son of Thomas Johann Heinrich Mann (a senator and a grain merchant) and his wife Júlia da Silva Bruhns

Júlia da Silva Bruhns (14 August 1851, Paraty – 11 March 1923, Weßling) was the Brazilian mother of Thomas and Heinrich Mann and one of the matriarchs of the Mann family.

Biography

Da Silva Bruhns was born in Paraty, Rio de Janeiro stat ...

, a Brazilian woman of German, Portuguese and Native Brazilian ancestry, who emigrated to Germany with her family when she was seven years old. His mother was Roman Catholic

The Catholic Church (), also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.27 to 1.41 billion baptized Catholics worldwide as of 2025. It is among the world's oldest and largest international institut ...

but Mann was baptised into his father's Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

religion. Mann's father died in 1891, and after that his trading firm was liquidated. The family subsequently moved to Munich

Munich is the capital and most populous city of Bavaria, Germany. As of 30 November 2024, its population was 1,604,384, making it the third-largest city in Germany after Berlin and Hamburg. Munich is the largest city in Germany that is no ...

. Mann first studied science at a Lübeck '' Gymnasium'' (secondary school), then attended the Ludwig Maximillians University of Munich as well as the Technical University of Munich

The Technical University of Munich (TUM or TU Munich; ) is a public research university in Munich, Bavaria, Germany. It specializes in engineering, technology, medicine, and applied and natural sciences.

Established in 1868 by King Ludwig II ...

, where, in preparation for a journalism career, he studied history, economics, art history and literature.

Mann lived in Munich from 1891 until 1933, with the exception of a year spent in Palestrina

Palestrina (ancient ''Praeneste''; , ''Prainestos'') is a modern Italian city and ''comune'' (municipality) with a population of about 22,000, in Lazio, about east of Rome. It is connected to the latter by the Via Prenestina. It is built upon ...

, Italy, with his elder brother, the novelist Heinrich. Thomas worked at the South German Fire Insurance Company in 1894–95. His career as a writer began when he wrote for the magazine ''Simplicissimus

:''Simplicissimus is also a name for the 1668 novel ''Der abenteuerliche Simplicissimus, Simplicius Simplicissimus'' and its protagonist.''

''Simplicissimus'' () was a German language, German weekly satire, satirical magazine, founded by Albert ...

''. Mann's first short story, "Little Mr Friedemann" (''Der Kleine Herr Friedemann''), was published in 1898.

In 1905, Mann married Katia Pringsheim, who came from a wealthy, secular Jewish industrialist family. She later joined the Lutheran

Lutheranism is a major branch of Protestantism that emerged under the work of Martin Luther, the 16th-century German friar and Protestant Reformers, reformer whose efforts to reform the theology and practices of the Catholic Church launched ...

church. The couple had six children: Erika (b. 1905), Klaus (b. 1906), Golo (b. 1909), Monika (b. 1910), Elisabeth (b. 1918) and Michael

Michael may refer to:

People

* Michael (given name), a given name

* he He ..., a given name

* Michael (surname), including a list of people with the surname Michael

Given name

* Michael (bishop elect)">Michael (surname)">he He ..., a given nam ...

(b. 1919).

Due to the Pringsheim family's wealth, Katia Mann was able to purchase a summer property in Bad Tölz

Bad Tölz (; Bavarian: ''Däiz'') is a town in Bavaria, Germany and the administrative center of the Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district.

History

Archaeology has shown continuous occupation of the site of Bad Tölz since the retreat of the gla ...

in 1908, on which they built a country house the following year, which they kept until 1917. In 1914 they also purchased a villa in Munich (at Poschinger Str in the borough of Bogenhausen

Bogenhausen (Central Bavarian: ''Bognhausn'') is the 13th borough of Munich, Germany. It is the geographically largest borough of Munich and comprises the city's north-eastern quarter, reaching from the Isar on the eastern side of the Englischer ...

, today 10 Thomas-Mann-Allee) where they lived until 1933.

Pre-war and Second World War period

In 1912, Katia was treated for tuberculosis for a few months in asanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, is a historic name for a specialised hospital for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments, and convalescence.

Sanatoriums are often in a health ...

in Davos

Davos (, ; or ; ; Old ) is an Alpine resort town and municipality in the Prättigau/Davos Region in the canton of Graubünden, Switzerland. It has a permanent population of (). Davos is located on the river Landwasser, in the Rhaetian ...

, Switzerland, where Thomas Mann visited her for a few weeks. This inspired him to write his 1924 novel ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann. It was first published in Germany in November 1924. Since then, it has gone through numerous editions and been translated into many languages. It is widely considered a seminal work of 20t ...

''. He was also appalled by the risk of international confrontation between Germany and France, following the Agadir Crisis

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis, was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in July 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat to Agadir, ...

in Morocco, and later by the outbreak of the First World War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

. The novel ends with the outbreak of this war, in which the hero perishes.

As a "German patriot", Mann had the proceeds from their summer house used in 1917 to subscribe to war bonds, which lost their face value after the war was lost. His father-in-law did the same, which caused a loss of a major part of the Pringsheim family's wealth. The disastrous inflation of 1923 and 1924 resulted in additional high losses. The sales success of his novel ''The Magic Mountain'', published in 1924, improved his financial situation again, as did the award of the Nobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1929. He used the prize money to build a cottage

A cottage, during Feudalism in England, England's feudal period, was the holding by a cottager (known as a cotter or ''bordar'') of a small house with enough garden to feed a family and in return for the cottage, the cottager had to provide ...

in the fishing village of Nida, Lithuania on the Curonian Spit, where there was a German art colony and where he spent the summers of 1930–1932 working on ''Joseph and His Brothers

''Joseph and His Brothers'' (, ) is a four-part novel by Thomas Mann, written over the course of 16 years. Mann retells the familiar stories of Genesis, from Jacob to Joseph (chapters 27–50), setting it in the historical context of the ...

''. Today, the cottage is a cultural center dedicated to him, with a small memorial exhibition.

In February 1933, while having finished a book tour to Amsterdam, Brussels and Paris, Thomas Mann recovered in Arosa

Arosa is a List of towns in Switzerland, town and a municipalities of Switzerland, municipality in the Plessur Region in the canton of Graubünden in Switzerland. It is both a summer and a winter tourist resort.

On 1 January 2013, the former mu ...

(Switzerland) when Hitler took power and Mann heard from his eldest children, Klaus and Erika in Munich, that it would not be safe for him to return to Germany. His political views (see chapter below) had made him an enemy of the Nazis for years. He was doubtful at first, because, with a certain naïveté, he could not imagine the violence of the overthrow and the persecution of opponents of the regime, but the children insisted, and their advice later turned out to be accurate when it emerged that even their driver-caretaker had become an informant

An informant (also called an informer or, as a slang term, a "snitch", "rat", "canary", "stool pigeon", "stoolie", "tout" or "grass", among other terms) is a person who provides privileged information, or (usually damaging) information inten ...

and that Mann's immediate arrest would have been very likely. The family (except these two children who went to Amsterdam) emigrated to Küsnacht

Küsnacht () is a municipality in the district of Meilen in the canton of Zürich, Switzerland.

History

Küsnacht is first mentioned in 1188 as ''de Cussenacho''.

Earliest findings of settlement date back to the Stone Age. There are also findi ...

, near Zürich

Zurich (; ) is the list of cities in Switzerland, largest city in Switzerland and the capital of the canton of Zurich. It is in north-central Switzerland, at the northwestern tip of Lake Zurich. , the municipality had 448,664 inhabitants. The ...

, Switzerland, after a stopover in Sanary-sur-Mer, France. The son Golo managed, at great risk, to smuggle the already completed chapters of the ''Joseph'' novel and the (sensitive) diaries into Switzerland. The Bavarian Political Police searched Mann's house in Munich and confiscated the house, its inventory and the bank accounts. At the same time, an arrest warrant

An arrest warrant is a warrant issued by a judge or magistrate on behalf of the state which authorizes the arrest and detention of an individual or the search and seizure of an individual's property.

Canada

Arrest warrants are issued by a jud ...

was issued. Mann was also no longer able to use his holiday home in Lithuania because it was only a few hundred yards from the German border and he seemed to be at risk there. When all members of the Poetry Section at the Prussian Academy of Arts

The Prussian Academy of Arts () was a state arts academy first established in 1694 by prince-elector Frederick III of Electorate of Brandenburg, Brandenburg in Berlin, in personal union Duke Frederick I of Prussia, and later king in Kingdom of ...

were asked to make a declaration of loyalty to the National Socialist government, Mann declared his resignation on March 17, 1933.

The writer's freedom of movement was reduced when his German passport expired. The Manns traveled to the United States for the first two times in 1934 and 1935. There was great interest in the prominent writer; the authorities allowed him entry without a valid passport. He received Czechoslovak citizenship and a passport in 1936, even though he had never lived there. A few weeks later, his German citizenship was revoked – at the same time as his wife Katia and their children Golo, Elisabeth and Michael. Furthermore, the Nazi government now expropriated the family home in Munich, which Reinhard Heydrich

Reinhard Tristan Eugen Heydrich ( , ; 7 March 1904 – 4 June 1942) was a German high-ranking SS and police official during the Nazi era and a principal architect of the Holocaust. He held the rank of SS-. Many historians regard Heydrich ...

in particular insisted on. It had already been confiscated and forcibly rented out in 1933. In December 1936, the University of Bonn

The University of Bonn, officially the Rhenish Friedrich Wilhelm University of Bonn (), is a public research university in Bonn, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany. It was founded in its present form as the () on 18 October 1818 by Frederick Willi ...

withdrew Mann's honorary doctorate, which he had been awarded in 1919.

In 1939, following the German occupation of Czechoslovakia

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany, the country of the Germans and German things

**Germania (Roman era)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizenship in Germany, see also Ge ...

, Mann emigrated to the United States, while his in-laws only managed thanks to high-ranking connections to leave Germany for Zurich in October 1939. The Manns moved to Princeton, New Jersey

The Municipality of Princeton is a Borough (New Jersey), borough in Mercer County, New Jersey, United States. It was established on January 1, 2013, through the consolidation of the Borough of Princeton, New Jersey, Borough of Princeton and Pri ...

, where they lived on 65 Stockton Street and he began to teach at Princeton University

Princeton University is a private university, private Ivy League research university in Princeton, New Jersey, United States. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth, New Jersey, Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the List of Colonial ...

. In 1941 he was designated consultant in German Literature, later Fellow in Germanic Literature, at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

. In 1942, the Mann family moved to 1550 San Remo Drive in the Pacific Palisades neighborhood of Los Angeles, California. The Manns were prominent members of the German expatriate community of Los Angeles and would frequently meet other emigres at the house of Salka and Bertold Viertel in Santa Monica, and at the Villa Aurora, the home of fellow German exile Lion Feuchtwanger

Lion Feuchtwanger (; 7 July 1884 – 21 December 1958) was a German Jewish novelist and playwright. A prominent figure in the literary world of Weimar Republic, Weimar Germany, he influenced contemporaries including playwright Bertolt Brecht.

...

.Jewish Women's ArchiveSalka Viertel , Jewish Women's Archive

. Retrieved 19 November 2016. Thomas Mann's always difficult relationship with his brother Heinrich, who envied Thomas's success and wealth and also differed politically, hardly improved when the latter arrived in California, poor and sickly, in need of support. On 23 June 1944, Thomas Mann was naturalized as a citizen of the United States. The Manns lived in Los Angeles until 1952.

Anti-Nazi broadcasts

The outbreak of World War II, on 1 September 1939, prompted Mann to offer anti-Nazi speeches (in German) to the German people via theBBC

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved into its current sta ...

. In October 1940, he began monthly broadcasts, recorded in the U.S. and flown to London, where the BBC German Service broadcast them to Germany on the longwave

In radio, longwave (also spelled long wave or long-wave and commonly abbreviated LW) is the part of the radio spectrum with wavelengths longer than what was originally called the medium-wave (MW) broadcasting band. The term is historic, dati ...

band. In these eight-minute addresses, Mann condemned Hitler and his "paladins" as crude philistines completely out of touch with European culture. In one noted speech, he said: "The war is horrible, but it has the advantage of keeping Hitler from making speeches about culture."

Mann was one of the few publicly active opponents of Nazism among German expatriates in the U.S. In a BBC broadcast of 30 December 1945, Mann expressed understanding as to why those peoples that had suffered from the Nazi regime would embrace the idea of German collective guilt. But he also thought that many enemies might now have second thoughts about "revenge". And he expressed regret that such judgement cannot be based on the individual:

Houses that the Manns lived in

Bad Tölz

Bad Tölz (; Bavarian: ''Däiz'') is a town in Bavaria, Germany and the administrative center of the Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen district.

History

Archaeology has shown continuous occupation of the site of Bad Tölz since the retreat of the gla ...

, Bavaria

Nida-Thomas-Mann-Haus01.jpg, Mann's summer cottage in Nidden, East Prussia

East Prussia was a Provinces of Prussia, province of the Kingdom of Prussia from 1772 to 1829 and again from 1878 (with the Kingdom itself being part of the German Empire from 1871); following World War I it formed part of the Weimar Republic's ...

(now Nida, Lithuania), now a memorial museum

200729 Thomas Mann House ml.jpg, Thomas Mann House, Pacific Palisades, Los Angeles. Residence in exile from 1942 until 1952

Thomas Manns Haus in Kilchberg-2.jpg, House in Kilchberg, Switzerland. Last residence 1954–1955

Last years

With the start of the

With the start of the Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

, he was increasingly frustrated by rising McCarthyism

McCarthyism is a political practice defined by the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a Fear mongering, campaign spreading fear of communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage i ...

. As a "suspected communist", he was required to testify to the House Un-American Activities Committee

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative United States Congressional committee, committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 19 ...

, where he was termed "one of the world's foremost apologists for Stalin and company". He was listed by HUAC as being "affiliated with various peace organizations or Communist fronts". Being in his own words a non-communist, rather than an anti-communist

Anti-communism is political and ideological opposition to communist beliefs, groups, and individuals. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in Russia, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, when th ...

, Mann openly opposed the allegations: "As an American citizen of German birth, I finally testify that I am painfully familiar with certain political trends. Spiritual intolerance, political inquisitions, and declining legal security, and all this in the name of an alleged 'state of emergency'. ... That is how it started in Germany." As Mann joined protests against the jailing of the Hollywood Ten

The Hollywood blacklist was the mid-20th century banning of suspected Communists from working in the United States entertainment industry. The blacklisting, blacklist began at the onset of the Cold War and Red Scare#Second Red Scare (1947–1957 ...

and the firing of schoolteachers suspected of being Communists, he found "the media had been closed to him". Finally, he was forced to quit his position as Consultant in Germanic Literature at the Library of Congress

The Library of Congress (LOC) is a research library in Washington, D.C., serving as the library and research service for the United States Congress and the ''de facto'' national library of the United States. It also administers Copyright law o ...

, and in 1952, he returned to Europe, to live in Kilchberg, near Zürich, Switzerland. Here he initially lived in a rented house and bought his last house there in 1954 (which later his widow and then their son Golo lived in until their deaths). He never again lived in Germany, though he regularly traveled there. His most important German visit was in 1949, at the 200th birthday of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, attending celebrations in Frankfurt am Main

Frankfurt am Main () is the most populous city in the States of Germany, German state of Hesse. Its 773,068 inhabitants as of 2022 make it the List of cities in Germany by population, fifth-most populous city in Germany. Located in the forela ...

(then West Germany

West Germany was the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) from its formation on 23 May 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with East Germany on 3 October 1990. It is sometimes known as the Bonn Republi ...

) and Weimar

Weimar is a city in the state (Germany), German state of Thuringia, in Central Germany (cultural area), Central Germany between Erfurt to the west and Jena to the east, southwest of Leipzig, north of Nuremberg and west of Dresden. Together w ...

(then East Germany

East Germany, officially known as the German Democratic Republic (GDR), was a country in Central Europe from Foundation of East Germany, its formation on 7 October 1949 until German reunification, its reunification with West Germany (FRG) on ...

), as a statement that German culture extended beyond the new political borders. He also visited Lübeck, where he saw his parents' house, which was partially destroyed by the bombing of Lübeck in World War II (and only later rebuilt). The city welcomed him warmly, but the patrician hanseatic

The Hanseatic League was a Middle Ages, medieval commercial and defensive network of merchant guilds and market towns in Central Europe, Central and Northern Europe, Northern Europe. Growing from a few Northern Germany, North German towns in the ...

families gave him a reserved welcome, since the publication of ''Buddenbrooks'' they had resented him for daring to describe their caste with some mockery, as they at least felt about it.

Along with Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein (14 March 187918 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is best known for developing the theory of relativity. Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics. His mass–energy equivalence f ...

, Mann was one of the sponsors of the Peoples' World Convention (PWC), also known as Peoples' World Constituent Assembly (PWCA), which took place in 1950–51 at Palais Electoral, Geneva

Geneva ( , ; ) ; ; . is the List of cities in Switzerland, second-most populous city in Switzerland and the most populous in French-speaking Romandy. Situated in the southwest of the country, where the Rhône exits Lake Geneva, it is the ca ...

, Switzerland.

Death

Following his 80th birthday, Mann went on vacation toNoordwijk

Noordwijk () is a town and municipality in the west of the Netherlands, in the provinces of the Netherlands, province of South Holland. The municipality covers an area of of which is water and had a population of in .

On 1 January 2019, the f ...

in the Netherlands. On 18 July 1955, he began to experience pain and unilateral swelling in his left leg. The condition of thrombophlebitis

Thrombophlebitis is a phlebitis (inflammation of a vein) related to a thrombus (blood clot). When it occurs repeatedly in different locations, it is known as thrombophlebitis migrans (migratory thrombophlebitis).

Signs and symptoms

The following ...

was diagnosed by Dr. Mulders from Leiden and confirmed by Dr. Wilhelm Löffler. Mann was transported to a Zürich hospital, but soon developed a state of shock

Shock may refer to:

Common uses

Healthcare

* Acute stress reaction, also known as psychological or mental shock

** Shell shock, soldiers' reaction to battle trauma

* Circulatory shock, a medical emergency

** Cardiogenic shock, resulting from ...

. On 12 August 1955, he died.Bollinger A. he death of Thomas Mann: consequence of erroneous angiologic diagnosis? '' Wiener Medizinische Wochenschrift'', 1999; 149(2–4):30–32. Postmortem, his condition was found to have been misdiagnosed. The pathologic diagnosis, made by Christoph Hedinger, showed he had actually suffered a perforated iliac artery aneurysm

An aneurysm is an outward :wikt:bulge, bulging, likened to a bubble or balloon, caused by a localized, abnormal, weak spot on a blood vessel wall. Aneurysms may be a result of a hereditary condition or an acquired disease. Aneurysms can also b ...

resulting in a retroperitoneal

The retroperitoneal space (retroperitoneum) is the anatomical space (sometimes a potential space) behind (''retro'') the peritoneum. It has no specific delineating anatomical structures. Organs are retroperitoneal if they have peritoneum on thei ...

hematoma

A hematoma, also spelled haematoma, or blood suffusion is a localized bleeding outside of blood vessels, due to either disease or trauma including injury or surgery and may involve blood continuing to seep from broken capillaries. A hematoma is ...

, compression and thrombosis

Thrombosis () is the formation of a Thrombus, blood clot inside a blood vessel, obstructing the flow of blood through the circulatory system. When a blood vessel (a vein or an artery) is injured, the body uses platelets (thrombocytes) and fib ...

of the iliac vein. (At that time, lifesaving vascular surgery had not been developed.) On 16 August 1955, Thomas Mann was buried in the Kilchberg village cemetery.

Legacy

Mann's work influenced many later authors, such asYukio Mishima

Kimitake Hiraoka ( , ''Hiraoka Kimitake''; 14 January 192525 November 1970), known by his pen name Yukio Mishima ( , ''Mishima Yukio''), was a Japanese author, poet, playwright, actor, model, Shintoist, Ultranationalism (Japan), ultranationalis ...

. Joseph Campbell also stated in an interview with Bill Moyers that Mann was one of his mentors. Many institutions are named in his honour, for instance the Thomas Mann Gymnasium of Budapest

Budapest is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns of Hungary, most populous city of Hungary. It is the List of cities in the European Union by population within city limits, tenth-largest city in the European Union by popul ...

.

Career

Blanche Knopf

Blanche Wolf Knopf (July 30, 1894 – June 4, 1966) was an American book publisher who was the president of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., and wife of Alfred A. Knopf Sr., with whom she established the firm in 1915. She traveled the world seeking new ...

of Alfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Blanche Knopf and Alfred A. Knopf Sr. in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers ...

publishing house was introduced to Mann by H.L. Mencken while on a book-buying trip to Europe. Knopf became Mann's American publisher, and Blanche hired scholar Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter

Helen Tracy Lowe-Porter (' Porter; June 15, 1876 – April 26, 1963) was an American translator and writer, best known for translating almost all of the works of Thomas Mann for their first publication in English.

Personal life

Helen Tracy Porte ...

to translate Mann's books in 1924. Lowe-Porter subsequently translated Mann's complete works. Blanche Knopf continued to look after Mann. After ''Buddenbrooks'' proved successful in its first year, the Knopfs sent him an unexpected bonus. Later in the 1930s, Blanche helped arrange for Mann and his family to emigrate to America.

Nobel Prize in Literature

Mann was awarded theNobel Prize in Literature

The Nobel Prize in Literature, here meaning ''for'' Literature (), is a Swedish literature prize that is awarded annually, since 1901, to an author from any country who has, in the words of the will of Swedish industrialist Alfred Nobel, "in ...

in 1929, after he had been nominated by Anders Österling, member of the Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy (), founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. Its 18 members, who are elected for life, comprise the highest Swedish language authority. Outside Scandinavia, it is best known as the body t ...

, principally in recognition of his popular achievements with ''Buddenbrooks

''Buddenbrooks'' () is a 1901 novel by Thomas Mann, chronicling the decline of a wealthy north German merchant family over the course of four generations, incidentally portraying the manner of life and mores of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie in th ...

'' (1901), ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann. It was first published in Germany in November 1924. Since then, it has gone through numerous editions and been translated into many languages. It is widely considered a seminal work of 20t ...

'' (''Der Zauberberg'', 1924), and his numerous short stories. (Due to the personal taste of an influential committee member, only'' Buddenbrooks'' was cited at any great length.) Based on Mann's own family, ''Buddenbrooks'' relates the decline of a merchant family in Lübeck over the course of four generations. ''The Magic Mountain'' (''Der Zauberberg'', 1924) follows an engineering student who, planning to visit his tubercular cousin at a Swiss sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, is a historic name for a specialised hospital for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments, and convalescence.

Sanatoriums are often in a health ...

for only three weeks, finds his departure from the sanatorium delayed. During that time, he confronts medicine and the way it looks at the body and encounters a variety of characters, who play out ideological conflicts and discontents of contemporary European civilization. The tetralogy ''Joseph and His Brothers'' is an epic novel written over a period of sixteen years and is one of the largest and most significant works in Mann's oeuvre. Later novels included '' Lotte in Weimar'' (1939), in which Mann returned to the world of Goethe's novel ''The Sorrows of Young Werther

''The Sorrows of Young Werther'' (; ), or simply ''Werther'', is a 1774 epistolary novel by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Johann Wolfgang Goethe, which appeared as a revised edition in 1787. It was one of the main novels in the ''Sturm und Drang'' ...

'' (1774); '' Doctor Faustus'' (1947), the story of the fictitious composer Adrian Leverkühn and the corruption of German culture

The culture of Germany has been shaped by its central position in Europe and a history spanning over a millennium. Characterized by significant contributions to art, music, philosophy, science, and technology, German culture is both diverse and ...

in the years before and during World War II; and ''Confessions of Felix Krull

''Confessions of Felix Krull'' () is an unfinished 1954 novel by the Germany, German author Thomas Mann.

Synopsis

The novel is narrated by the protagonist, an impostor and adventurer named Felix Krull, the son of a ruined Rhineland winemaker. F ...

'' (''Bekenntnisse des Hochstaplers Felix Krull'', 1954), which was unfinished at Mann's death. These later works prompted two members of the Swedish Academy

The Swedish Academy (), founded in 1786 by King Gustav III, is one of the Royal Academies of Sweden. Its 18 members, who are elected for life, comprise the highest Swedish language authority. Outside Scandinavia, it is best known as the body t ...

to nominate Mann for the Nobel Prize in Literature a second time, in 1948.

Influence

The writerTheodor Fontane

Theodor Fontane (; 30 December 1819 – 20 September 1898) was a German novelist and poet, regarded by many as the most important 19th-century German-language Literary realism, realist author. He published the first of his novels, for which he i ...

, who died in 1898, had a particular stylistic influence on Thomas Mann. Of course, Mann always admired and emulated Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

, the German "poet prince". The Danish author Herman Bang, with whom he felt a kindred spirit, had a certain influence, especially on the novellas. The pessimistic philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer

Arthur Schopenhauer ( ; ; 22 February 1788 – 21 September 1860) was a German philosopher. He is known for his 1818 work ''The World as Will and Representation'' (expanded in 1844), which characterizes the Phenomenon, phenomenal world as ...

provided philosophical inspiration for the ''Buddenbrooks narrative of decline, especially with his two-volume work ''The World as Will and Representation

''The World as Will and Representation'' (''WWR''; , ''WWV''), sometimes translated as ''The World as Will and Idea'', is the central work of the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer. The first edition was published in late 1818, with the date ...

'', which Mann studied closely while writing the novel. Russian narrators should also be mentioned, he admired the Russian Literature

Russian literature refers to the literature of Russia, its Russian diaspora, émigrés, and to Russian language, Russian-language literature. Major contributors to Russian literature, as well as English for instance, are authors of different e ...

's ability for self-criticism, at least during the 19th century, in Nikolai Gogol

Nikolai Vasilyevich Gogol; ; (; () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, and playwright of Ukrainian origin.

Gogol used the Grotesque#In literature, grotesque in his writings, for example, in his works "The Nose (Gogol short story), ...

, Ivan Goncharov

Ivan Aleksandrovich Goncharov ( , ; rus, Ива́н Алекса́ндрович Гончаро́в, r=Iván Aleksándrovich Goncharóv, p=ɪˈvan ɐlʲɪkˈsandrəvʲɪdʑ ɡənʲtɕɪˈrof; – ) was a Russian novelist best known for his n ...

and Ivan Turgenev

Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev ( ; rus, links=no, Иван Сергеевич ТургеневIn Turgenev's day, his name was written ., p=ɪˈvan sʲɪrˈɡʲe(j)ɪvʲɪtɕ tʊrˈɡʲenʲɪf; – ) was a Russian novelist, short story writer, poe ...

. Mann believed that in order to make a bourgeois revolution, the Russians had to forget Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influenti ...

. He particularly loved Leo Tolstoy

Count Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy Tolstoy pronounced his first name as , which corresponds to the romanization ''Lyov''. () (; ,Throughout Tolstoy's whole life, his name was written as using Reforms of Russian orthography#The post-revolution re ...

, whom he considered an anarchist and whom he lovingly and mockingly admired for his "courage to be boring."

Throughout Mann's Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky. () was a Russian novelist, short story writer, essayist and journalist. He is regarded as one of the greatest novelists in both Russian and world literature, and many of his works are considered highly influenti ...

essay, he finds parallels between the Russian and the sufferings of Friedrich Nietzsche

Friedrich Wilhelm Nietzsche (15 October 1844 – 25 August 1900) was a German philosopher. He began his career as a classical philology, classical philologist, turning to philosophy early in his academic career. In 1869, aged 24, Nietzsche bec ...

. Speaking of Nietzsche, he says, "his personal feelings initiate him into those of the criminal ... in general all creative originality, all artist nature in the broadest sense of the word, does the same. It was the French painter and sculptor Degas

Edgar Degas (, ; born Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas, ; 19 July 183427 September 1917) was a French people, French Impressionism, Impressionist artist famous for his pastel drawings and oil paintings.

Degas also produced bronze sculptures, Print ...

who said that an artist must approach his work in the spirit of the criminal about to commit a crime." Nietzsche's influence on Mann runs deep in his work, especially in Nietzsche's views on decay and the proposed fundamental connection between sickness and creativity. Mann believed that disease should not be regarded as wholly negative. In his essay on Dostoevsky, we find: "but after all and above all it depends on who is diseased, who mad, who epileptic or paralytic: an average dull-witted man, in whose illness any intellectual or cultural aspect is non-existent; or a Nietzsche or Dostoyevsky. In their case something comes out in illness that is more important and conducive to life and growth than any medical guaranteed health or sanity.... other words: certain conquests made by the soul and the mind are impossible without disease, madness, crime of the spirit."

Thematic and stylistic focuses

Many of Thomas Mann's works have the following similarities: * A "gravely-mischievous" style that is very popular with readers, with superficial solemnity and an underlying ironic humor, mostly benevolent, never drastic or bitter and only rarely degenerating into the macabre. Thomas Mann took this "mild irony" from his literary predecessor and role modelTheodor Fontane

Theodor Fontane (; 30 December 1819 – 20 September 1898) was a German novelist and poet, regarded by many as the most important 19th-century German-language Literary realism, realist author. He published the first of his novels, for which he i ...

, at first in ''Buddenbrooks

''Buddenbrooks'' () is a 1901 novel by Thomas Mann, chronicling the decline of a wealthy north German merchant family over the course of four generations, incidentally portraying the manner of life and mores of the Hanseatic bourgeoisie in th ...

'' where it is modified into local sedateness through Low German

Low German is a West Germanic languages, West Germanic language variety, language spoken mainly in Northern Germany and the northeastern Netherlands. The dialect of Plautdietsch is also spoken in the Russian Mennonite diaspora worldwide. "Low" ...

sprinkles and quotations. He continued this style, with variations, throughout his life (the contemporary, much more avant-garde author Alfred Döblin

Bruno Alfred Döblin (; 10 August 1878 – 26 June 1957) was a German novelist, essayist, and doctor, best known for his novel '' Berlin Alexanderplatz'' (1929). A prolific writer whose œuvre spans more than half a century and a wide variety of ...

mocked that Mann had "elevated the ''pressed crease'' to a style principle"). In ''Joseph and His Brothers

''Joseph and His Brothers'' (, ) is a four-part novel by Thomas Mann, written over the course of 16 years. Mann retells the familiar stories of Genesis, from Jacob to Joseph (chapters 27–50), setting it in the historical context of the ...

'' the tone takes on something fairytale-biblical, but here too the irony often shines through. In '' Doctor Faustus'', Thomas Mann adopts a predominantly serious tone in view of the sinister theme, although the critical irony does not completely disappear there either, for which the description of the nationalist milieu in the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

in particular provides ample reason.

* The amusingly entertaining, mostly ironic descriptions of contemporaries as well as people of the past and their views and lifestyles based on his own observations or research, often very detailed, similar to his contemporary Marcel Proust

Valentin Louis Georges Eugène Marcel Proust ( ; ; 10 July 1871 – 18 November 1922) was a French novelist, literary critic, and essayist who wrote the novel (in French – translated in English as ''Remembrance of Things Past'' and more r ...

, are combined with various profound components: in ''Buddenbrooks'' with the motif of economic and spiritual decline of a family, in ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann. It was first published in Germany in November 1924. Since then, it has gone through numerous editions and been translated into many languages. It is widely considered a seminal work of 20t ...

'' with the philosophical disputes of the time before the First World War, in '' Lotte in Weimar'' with the circumstances of Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

's Weimar Classicism

Weimar Classicism () was a German literary and cultural movement, whose practitioners established a new humanism from the synthesis of ideas from Romanticism, Classicism, and the Age of Enlightenment. It was named after the city of Weimar in th ...

and the complicated effect between real and literary love, in ''Joseph and his brothers'' with biblical-mythical motifs and the question of origins as well as the eternal recurrence of the same "mythical" stories, in ''Doctor Faustus'' with the historical-political circumstances of the rise, success and fall of Nazism.

* Attachment to home regions: Lübeck (Buddenbrooks, Tonio Kröger) and Munich (Gladius Dei, At the Prophet, Disorder and Early Suffering) are in the foreground of important works.

* Classical music already plays a central role in ''Buddenbrooks'' and ''Tristan

Tristan (Latin/ Brythonic: ''Drustanus''; ; ), also known as Tristran or Tristram and similar names, is the folk hero of the legend of Tristan and Iseult. While escorting the Irish princess Iseult to wed Tristan's uncle, King Mark of ...

'' (Mann loved Richard Wagner

Wilhelm Richard Wagner ( ; ; 22 May 181313 February 1883) was a German composer, theatre director, essayist, and conductor who is chiefly known for his operas (or, as some of his mature works were later known, "music dramas"). Unlike most o ...

's operas and, in his 1933 essay ''The Suffering and Greatness of Richard Wagner'', defended him against the Nazis' attempt to appropriate Wagner as a nationalist icon) and Neue Musik plays the main role in ''Doctor Faustus'' (about which Mann sought advice from Theodor W. Adorno

Theodor W. Adorno ( ; ; born Theodor Ludwig Wiesengrund; 11 September 1903 – 6 August 1969) was a German philosopher, musicologist, and social theorist. He was a leading member of the Frankfurt School of critical theory, whose work has com ...

and gave his hero's music features of Arnold Schoenberg

Arnold Schoenberg or Schönberg (13 September 187413 July 1951) was an Austrian and American composer, music theorist, teacher and writer. He was among the first Modernism (music), modernists who transformed the practice of harmony in 20th-centu ...

's compositional style).

* Central to Thomas Mann's thoughts and work is the mutual relationship between art and life: ''Ambiguity as a system'' is also the title of an essay.

* Conscientiousness: Thomas Mann always wrote his works after long and thorough research into the facts and the atmospheric circumstances.

* Political commitment (see below: Political views): His – mostly indirect – commitment runs through many of his works, from the ''Buddenbrooks'' (covering the revolutionary and counter-revolutionary shifts of the entire 19th century) to '' Mario and the Magician'' (mocking the atmosphere of 1920s Italian fascism

Italian fascism (), also called classical fascism and Fascism, is the original fascist ideology, which Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini developed in Italy. The ideology of Italian fascism is associated with a series of political parties le ...

) to ''Doctor Faustus''. In contrast to his brother Heinrich and his children Erika and Klaus, Thomas Mann at first advocated a rather conservative stance, especially in the '' Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man'' (1918), later and in his major works, however, a moderate, centrist and occasionally progressive attitude, while they were more "left-leaning".

* Homoerotic allusions are also common and recur in many works (see below: Sexuality and literary work).

Political views

During World War I, Mann supported the conservatism ofKaiser Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as the Hohenzollern dynasty ...

, attacked liberalism, and supported the war effort, calling the Great War

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

"a purification, a liberation, an enormous hope". In his 600-page-long work '' Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man'' (1918), Mann presented his conservative, anti-modernist philosophy: spiritual tradition over material progress, German patriotism over egalitarian internationalism, and rooted culture over rootless civilisation.

In " On the German Republic" (, 1922), Mann called upon German intellectuals to support the new Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic, officially known as the German Reich, was the German Reich, German state from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional republic for the first time in history; hence it is also referred to, and unofficially proclai ...

. The work was delivered at the Beethovensaal in Berlin on 13 October 1922, and published in '' Die neue Rundschau'' in November 1922. In the work, Mann developed his eccentric defence of the Republic based on extensive close readings of Novalis

Georg Philipp Friedrich Freiherr von Hardenberg (2 May 1772 – 25 March 1801), pen name Novalis (; ), was a German nobility, German aristocrat and polymath, who was a poet, novelist, philosopher and Mysticism, mystic. He is regarded as an inf ...

and Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman Jr. (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist, and journalist; he also wrote two novels. He is considered one of the most influential poets in American literature and world literature. Whitman incor ...

. Also in 1921, he wrote an essay ''Mind and Money'' in which he made a very open assessment of his family background: "In any case, I am personally indebted to the capitalist world order from the past, which is why it will never be appropriate for me to spit on it as it is ''à la mode'' these days." Thereafter, his political views gradually shifted toward liberal-left. He especially embraced democratic principles when the Weimar Republic was established.

Mann initially gave his support to the left-liberal German Democratic Party

The German Democratic Party (, DDP) was a liberal political party in the Weimar Republic, considered centrist or centre-left. Along with the right-liberal German People's Party (, DVP), it represented political liberalism in Germany between 19 ...

before urging unity behind the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a social, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achieving social equality. In modern practice, s ...

, probably less for ideological reasons, but because he only trusted the political party of the workers to provide sufficient mass and resistance to the growing Nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

. In 1930, he gave a public address in Berlin titled ''An Appeal to Reason'', in which he strongly denounced Nazism and encouraged resistance by the working class. This was followed by numerous essays and lectures in which he attacked the Nazis

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During H ...

. At the same time, he expressed increasing sympathy for socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

ideas. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, Mann and his wife were on holiday in Switzerland. Due to his strident denunciations of Nazi policies, his son Klaus advised him not to return. In contrast to those of his brother Heinrich and his son Klaus, Mann's books were not among those burnt publicly by Hitler's regime in May 1933, possibly since he had been the Nobel laureate in literature for 1929. In 1936, the Nazi government officially revoked his German citizenship.

During the war, Mann made a series of anti-Nazi radio-speeches, published as '' Listen, Germany!'' in 1943. They were recorded on tape in the United States and then sent to the United Kingdom, where the British Broadcasting Corporation

The British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is a British public broadcasting, public service broadcaster headquartered at Broadcasting House in London, England. Originally established in 1922 as the British Broadcasting Company, it evolved in ...

transmitted them, hoping to reach German listeners.

Views on Soviet communism and German National-Socialism

Mann expressed his belief in the collection of letters written in exile, ''Listen, Germany!'' (''Deutsche Hörer!''), that equating Soviet communism with Nazi fascism on the basis that both aretotalitarian

Totalitarianism is a political system and a form of government that prohibits opposition from political parties, disregards and outlaws the political claims of individual and group opposition to the state, and completely controls the public sph ...

systems was either superficial or insincere in showing a preference for nazism

Nazism (), formally named National Socialism (NS; , ), is the far-right totalitarian socio-political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Germany. During Hitler's rise to power, it was fre ...

. He clarified this view during a German press interview in July 1949, declaring that he was not a communist but that communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

at least had some relation to ideals of humanity and of a better future. He said that the transition of the communist revolution

A communist revolution is a proletarian revolution inspired by the ideas of Marxism that aims to replace capitalism with communism. Depending on the type of government, the term socialism can be used to indicate an intermediate stage between ...

into an autocratic regime was a tragedy while Nazism was only "devilish nihilism

Nihilism () encompasses various views that reject certain aspects of existence. There have been different nihilist positions, including the views that Existential nihilism, life is meaningless, that Moral nihilism, moral values are baseless, and ...

".

Sexuality and literary work

Mann's diaries reveal his struggles with hisbisexuality

Bisexuality is romantic attraction, sexual attraction, or Human sexual activity, sexual behavior toward both males and females. It may also be defined as the attraction to more than one gender, to people of both the same and different gender, ...

, his attraction to men finding frequent reflection in his works, most prominently through the obsession of the elderly Aschenbach for the 14-year-old Polish boy Tadzio in the novella ''Death in Venice

''Death in Venice ''() is a novella by German author Thomas Mann, published in 1912. It presents an ennobled writer who visits Venice and is liberated, uplifted, and then increasingly obsessed by the sight of a boy in a family of Polish tourist ...

'' (''Der Tod in Venedig'', 1912). Anthony Heilbut's biography ''Thomas Mann: Eros and Literature'' (1997) uncovered the centrality of Mann's sexuality to his oeuvre. Gilbert Adair's work ''The Real Tadzio'' (2001) describes how, in 1911, Mann had stayed at the Grand Hôtel des Bains on the Venice Lido

The Lido, or Venice Lido (), is an barrier island in the Venetian Lagoon, Northern Italy; it is home to about 20,400 residents. The Venice Film Festival takes place at the Lido in late August/early September.

Geography

The Lido island is on ...

with his wife and brother, when he became enraptured by the angelic figure of Władysław (Władzio) Moes, a 10-year-old Polish boy ( the real Tadzio).

In the autobiographical novella '' Tonio Kröger'' from 1901, the young hero has a crush on a handsome male classmate (modeled after real-life Lübeck classmate Armin Martens). In the novella ''With the prophet'' (1904) Mann mocks the believing disciples of a neo-Romantic "prophet" who preaches asceticism and has a strong resemblance to the real contemporary poet

In the autobiographical novella '' Tonio Kröger'' from 1901, the young hero has a crush on a handsome male classmate (modeled after real-life Lübeck classmate Armin Martens). In the novella ''With the prophet'' (1904) Mann mocks the believing disciples of a neo-Romantic "prophet" who preaches asceticism and has a strong resemblance to the real contemporary poet Stefan George

Stefan Anton George (; 12 July 18684 December 1933) was a German symbolist poet and a translator of Dante Alighieri, William Shakespeare, Hesiod, and Charles Baudelaire. He is also known for his role as leader of the highly influential liter ...

and his '' George-Kreis'' ("George-Circle"). In 1902, George had met the fourteen-year-old boy Maximilian Kronberger

Maximilian Kronberger, known familiarly as Maximin (April 15, 1888 – April 16, 1904), was a German poet and a significant figure in the literary circle of Stefan George (the so‑called ''George‑Kreis'').

Maximin came to the attention of ...

; He made an idol of him and after his early death in 1904 transfigured him into a kind of Antinous

Antinous, also called Antinoös, (; ; – ) was a Greek youth from Bithynia, a favourite and lover of the Roman emperor Hadrian. Following his premature death before his 20th birthday, Antinous was deified on Hadrian's orders, being worshippe ...

-style "god".

Mann had also started planning a novel about Frederick the Great

Frederick II (; 24 January 171217 August 1786) was the monarch of Prussia from 1740 until his death in 1786. He was the last Hohenzollern monarch titled ''King in Prussia'', declaring himself ''King of Prussia'' after annexing Royal Prussia ...

in 1905/1906, which ultimately did not come to fruition. The sexuality of Frederick the Great would have played a significant role in this, its impact on his life, his political decisions and wars. In late 1914, at the start of World War I, Mann used the notes and excerpts already collected for this project to write his essay ''Frederick and the grand coalition'' in which he contrasted Frederick's soldierly, male drive and his literary, female connotations consisting of "decomposing" skepticism. A similar "decomposing skepticism" had already estranged the barely concealed gay novel characters ''Tonio Kröger'' and ''Hanno Buddenbrook'' (1901) from their traditional upper class family environments and hometown (which in both cases is Lübeck). The ''Confessions of Felix Krull

''Confessions of Felix Krull'' () is an unfinished 1954 novel by the Germany, German author Thomas Mann.

Synopsis

The novel is narrated by the protagonist, an impostor and adventurer named Felix Krull, the son of a ruined Rhineland winemaker. F ...

'', written from 1910 onwards, describes a self-absorbed young dandyish imposter who, if not explicitly, fits into the gay typology. The 1909 novel ''Royal Highness

Royal Highness is a style used to address or refer to some members of royal families, usually princes or princesses. Kings and their female consorts, as well as queens regnant, are usually styled ''Majesty''.

When used as a direct form of a ...

'', which describes a young unworldly and dreamy prince who forces himself into a marriage of convenience that ultimately becomes happy, was modeled after Mann's own romance and marriage to Katia Mann in February 1905. In ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann. It was first published in Germany in November 1924. Since then, it has gone through numerous editions and been translated into many languages. It is widely considered a seminal work of 20t ...

'', the enamored Hans Castorp, with his heart pounding, asks Pribislav Hippe if he could lend him his pencil, of which he keeps a few scraps like a relic. Borrowing and returning are poetic masks for a sexual act. But it is not just a poetic symbol. In his diary entry from September 15, 1950, Mann remembers "Williram Timpe's scraps from his pencil", referring to a classmate from Lübeck. The novella '' Mario and the Magician'' (1929) ends with a murder due to a male-male kiss.

Numerous homoerotic crushes are documented in his letters and diaries, both before and after his marriage. Mann's diary records his attraction to his own 13-year-old son, "Eissi" – Klaus Mann: "Klaus to whom recently I feel very drawn" (22 June). In the background conversations about man-to-man eroticism take place; a long letter is written to Carl Maria Weber on this topic, while the diary reveals: "In love with Klaus during these days" (5 June). "Eissi, who enchants me right now" (11 July). "Delight over Eissi, who in his bath is terribly handsome. Find it very natural that I am in love with my son ... Eissi lay reading in bed with his brown torso naked, which disconcerted me" (25 July). "I heard noise in the boys' room and surprised Eissi completely naked in front of Golo's bed acting foolish. Strong impression of his premasculine, gleaming body. Disquiet" (17 October 1920).

Mann was a friend of the violinist and painter Paul Ehrenberg, for whom he had feelings as a young man (at least until around 1903 when there is evidence that those feelings had cooled). The attraction that he felt for Ehrenberg, which is corroborated by notebook entries, caused Mann difficulty and discomfort and may have been an obstacle to his marrying an English woman, Mary Smith, whom he met in 1901. In 1927, while on summer vacation in Kampen (Sylt)

(Söl'ring: Kaamp) is a municipality and seaside resort on the island Sylt, in the district of Nordfriesland, in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. It is located north of the island's main town, Westerland, Germany, Westerland. The municipality is pa ...

, Mann fell in love with 17-year-old Klaus Heuser, to whom he dedicated the introduction to his essay ''" Kleist's Amphitryon, a Reconquest"'' in the fall of the same year, which he read publicly in Munich in the presence of Heuser. Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a Jupiter mass, mass more than 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined a ...

, who has transformed himself into the form of the general Amphitryon

Amphitryon (; Ancient Greek: Ἀμφιτρύων, ''gen''.: Ἀμφιτρύωνος; usually interpreted as "harassing either side", Latin: Amphitruo), in Greek mythology, was a son of Alcaeus, king of Tiryns in Argolis. His mother was named ...

, tries to seduce his wife Alcmene when the real Amphitryon returns home and Alcmene rejects the god. Mann understands Jupiter as the "lonely artistic spirit" who courts life, is rejected and, "a triumphant renouncer", learns to be content with his divinity. In 1950, Mann met the 19-year-old waiter Franz Westermeier, confiding to his diary "Once again this, once again love".. He immediately processed the experience in his essay ''"Michelangelo

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni (6March 147518February 1564), known mononymously as Michelangelo, was an Italian sculptor, painter, architect, and poet of the High Renaissance. Born in the Republic of Florence, his work was inspir ...

in his poems"'' (1950) and was also inspired to write '' The Black Swan'' (1954). In 1975, when Mann's diaries were published, creating a national sensation in Germany, the retired Westermeier was tracked down in the United States: he was flattered to learn he had been the object of Mann's obsession, but also shocked at its depth.

Mann's infatuations probably remained largely platonic. Katia Mann tolerated these love affairs, as did the children, because they knew that it didn't go too far. He exchanged letters with Klaus Heuser for a while and met him again in 1935. He wrote about the Heuser experience in his diary on May 6, 1934: "In comparison, the early experiences with Armin Martens and Williram Timpe recede far into the childlike, and that with Klaus Heuser was a late happiness with the character of life-relevant fulfillment... That's probably how it is humanly, and because of this normality I can feel my life is more canonical than through marriage and children." In the entry from February 20, 1942, he spoke again about Klaus Heuser: "Well, yes − lived and loved. Black eyes that shed tears for me, beloved lips that I kissed − it was there, I had it too, I'll be able to tell myself when I die." He was partly delighted, partly ashamed of the depth of his own emotions in these cases and mostly made them productive at some earlier or later date, but the experiences themselves were not yet literary. Only in retrospective, he converted them into literary production and sublimated his shame into the theory that "a writer experiences in order to express himself", that his life is just material. Mann even went so far as to accuse his brother Heinrich of his "aestheticism being a gesture-rich, highly gifted impotence for life and love." When Mann met the aging bachelor Heuser, who had worked in China for 18 years, for the last time in 1954, his daughter Erika scoffed: "Since he (Heuser) couldn't have the magician (= Thomas Mann's nickname with his children), he preferred to give it up completely."

Although Mann had always denied his novels had autobiographical components, the unsealing of his diaries revealing how consumed his life had been with unrequited and sublimated passion resulted in a reappraisal of his work. Thomas Mann had burned all of his diaries from before March 1933 in the garden of his home in Pacific Palisades in May 1945. Only the booklets from September 1918 to December 1921 were preserved because the author needed them for his work on '' Doctor Faustus''. He later decided to have them − and his diaries from 1933 onwards – published 20 years after his death and predicted "surprise and cheerful astonishment". They were published by Peter von Mendelssohn and Inge Jens in 10 volumes.

From the very beginning, Thomas' son Klaus Mann openly dealt with his own homosexuality in his literary work and open lifestyle and referred critically to his father's " sublimation" in his diary. On the other hand, Thomas's daughter Erika Mann

Erika Julia Hedwig Mann (9 November 1905 – 27 August 1969) was a German actress and writer, daughter of the novelist Thomas Mann.

Erika lived a bohemian lifestyle in Berlin and became a critic of National Socialism. After Hitler came to power ...

and his son Golo Mann came out only later in their lives. Thomas Mann reacted cautiously to Klaus's first novel ''The Pious Dance, Adventure Book of a Youth'' (1926), which is openly set in Berlin's homosexual milieu. Although he embraced male-male eroticism, he disapproved of gay lifestyle. The Eulenburg affair

The Eulenburg affair (also called the Harden–Eulenburg affair) was a public controversy surrounding a series of courts-martial and five civil trials regarding accusations of homosexual conduct, and accompanying libel trials, among prominent mem ...

, which broke out two years after Mann's marriage, had strengthened him in his renunciation of a gay life and he supported the journalist Maximilian Harden

__NOTOC__

Maximilian Harden (born Felix Ernst Witkowski, 20 October 1861 – 30 October 1927) was an influential German journalist and editor.

Biography

Born the son of a Jewish merchant in Berlin, he attended the '' Französisches Gymnasium'' ...

, who was friends with Katia Mann's family, in his denunciatory trial against the gay Prince of Eulenburg, a close friend of Emperor Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia from 1888 until Abdication of Wilhelm II, his abdication in 1918, which marked the end of the German Empire as well as th ...

. Thomas Mann was always concerned about his dignity, reputation and respectability; the "poet king" Goethe

Johann Wolfgang (von) Goethe (28 August 1749 – 22 March 1832) was a German polymath who is widely regarded as the most influential writer in the German language. His work has had a wide-ranging influence on Western literature, literary, Polit ...

was his role model. His horror at a possible collapse of these attributes found expression in the character of Aschenbach in ''Death in Venice''. But as time went on Mann became more open. When the twenty-two-year-old war novelist Gore Vidal

Eugene Luther Gore Vidal ( ; born Eugene Louis Vidal, October 3, 1925 – July 31, 2012) was an American writer and public intellectual known for his acerbic epigrammatic wit. His novels and essays interrogated the Social norm, social and sexual ...

published his first novel '' The City and the Pillar'' in 1948, a love-story between small-town American boys and a portrait of homosexual life in New York and Hollywood in the forties, a highly controversial book even among the publishers, not to mention the press, Mann called it a "noble work".

When the physician and pioneer of gay liberation Magnus Hirschfeld

Magnus Hirschfeld (14 May 1868 – 14 May 1935) was a German physician, Sexology, sexologist and LGBTQ advocate, whose German citizenship was later revoked by the Nazi government.David A. Gerstner, ''Routledge International Encyclopedia of Queer ...

sent another petition to the Reichstag in 1922 to abolish Section 175 of the German Criminal Code, under which many homosexuals were imprisoned simply because of their inclinations, Thomas Mann also signed. However, criminal liability among adults was only abolished through a change in the law on June 25, 1969 − fourteen years after Mann's death and just three days before the Stonewall riots

The Stonewall riots (also known as the Stonewall uprising, Stonewall rebellion, Stonewall revolution, or simply Stonewall) were a series of spontaneous riots and demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of ...

. This legal situation certainly had an impact throughout his life; the man whom the Nazis labeled a traitor never had any desire to be incarcerated for "criminal acts".

Cultural references

''The Magic Mountain''

Several literary and other works make reference to Mann's book ''The Magic Mountain

''The Magic Mountain'' (, ) is a novel by Thomas Mann. It was first published in Germany in November 1924. Since then, it has gone through numerous editions and been translated into many languages. It is widely considered a seminal work of 20t ...

'', including:

* Frederic Tuten's 1993 novel ''Tintin in the New World'' features many characters (such as Clavdia Chauchat, Mynheer Peeperkorn and others) from ''The Magic Mountain'' interacting with Tintin

Tintin usually refers to:

* ''The Adventures of Tintin'', the comics series by Belgian cartoonist Hergé

** Tintin (character), the protagonist and titular character of the series

Tintin or Tin Tin may also refer to:

Material related to ''The A ...

in Peru.