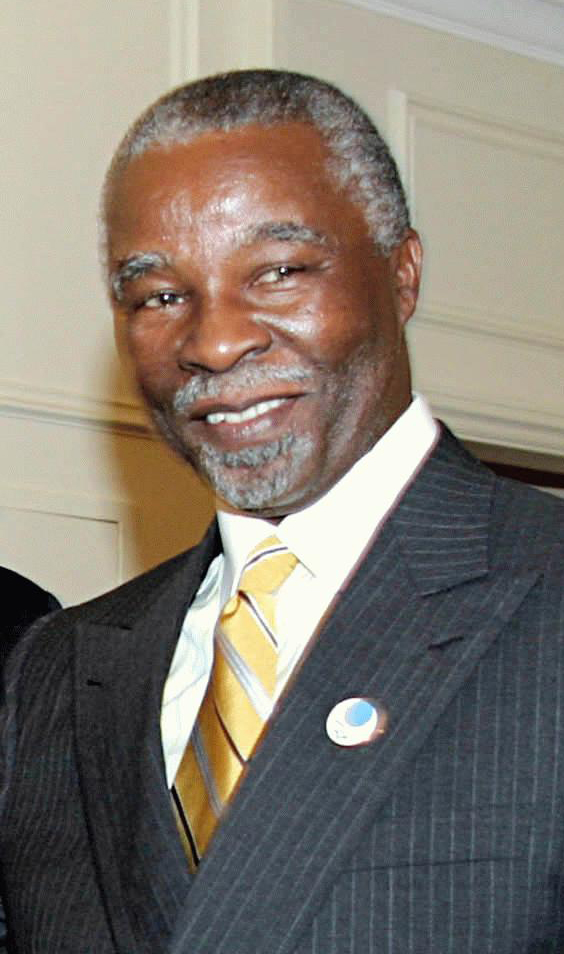

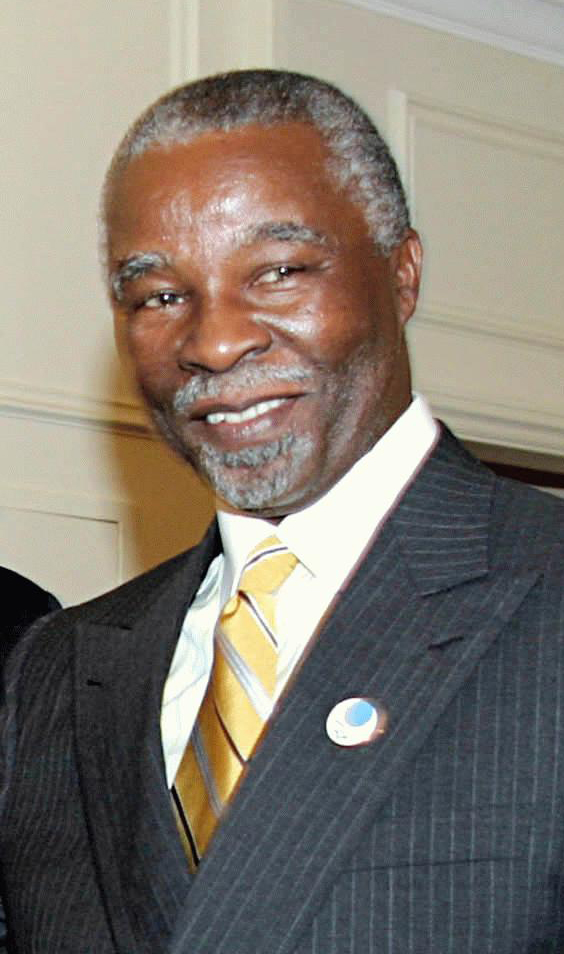

Thabo Mvuyelwa Mbeki (; born 18 June 1942) is a South African politician who served as the 2nd democratic

president of South Africa

The president of South Africa is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of South Africa. The president directs the executive branch of the government and is the commander-in-chief of the South African National Defence F ...

from 14 June 1999 to 24 September 2008, when he resigned at the request of his party, the

African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC).

Before that, he was

deputy president

A vice president or vice-president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vi ...

under

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

from 1994 to 1999.

The son of

Govan Mbeki

Govan Archibald Mvunyelwa Mbeki (9 July 1910 – 30 August 2001) was a South African politician, military commander, Communist leader who served as the Secretary of Umkhonto we Sizwe, at its inception in 1961. He was also the younger son of Ch ...

, an ANC intellectual, Mbeki has been involved in ANC politics since 1956, when he joined the

ANC Youth League

The African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) is the youth wing of the African National Congress (ANC). As set out in its constitution, the ANC Youth League is led by a National Executive Committee (NEC) and a National Working Committee (N ...

, and has been a member of the party's

National Executive Committee since 1975. Born in the

Transkei

Transkei ( , meaning ''the area beyond Great Kei River, he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei (), was an list of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa f ...

, he left South Africa aged twenty to attend university in England, and spent almost three decades in exile abroad, until the ANC was unbanned in 1990. He rose through the organisation in its information and publicity section and as

Oliver Tambo

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (27 October 191724 April 1993) was a South African anti-apartheid politician and activist who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

Biography Childhood

Oliver Tambo was ...

's protégé, but he was also an experienced diplomat, serving as the ANC's official representative in several of its African outposts. He was an early advocate for and leader of the diplomatic engagements which led to the

negotiations to end apartheid. After South Africa's

first democratic elections in 1994, he was appointed national deputy president. In subsequent years, it became apparent that he was Mandela's chosen successor, and he was elected unopposed as ANC president in 1997, enabling his rise to the presidency as the ANC's candidate in the

1999 elections.

While deputy president, Mbeki had been regarded as a steward of the government's

Growth, Employment and Redistribution policy, introduced in 1996, and as president he continued to subscribe to relatively conservative, market-friendly macroeconomic policies. During his presidency, South Africa experienced falling

public debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occu ...

, a narrowing

budget deficit

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit, the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budg ...

, and consistent, moderate economic growth. However, despite his retention of various

social democratic

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

programmes, and notable expansions to the

black economic empowerment programme, critics often regarded Mbeki's economic policies as

neoliberal

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pej ...

, with insufficient consideration for developmental and redistributive objectives. On these grounds, Mbeki grew increasingly alienated from the left wing of the ANC, and from the leaders of the ANC's

Tripartite Alliance

The Tripartite Alliance is an alliance between the African National Congress (ANC), the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). The ANC holds a plurality in the South African parliament, ...

partners, the

Congress of South African Trade Unions and

South African Communist Party

The South African Communist Party (SACP) is a communist party in South Africa. It was founded on 12 February 1921 as the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), and tactically dissolved itself in 1950 in the face of being declared illegal by t ...

. It was these leftist elements which supported

Jacob Zuma

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma (; born 12 April 1942) is a South African politician who served as the fourth president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018. He is also referred to by his initials JZ and clan names Nxamalala and Msholozi. Zuma was a for ...

over Mbeki in the political rivalry that erupted after Mbeki removed the latter from his post as deputy president in 2005.

As president, Mbeki had an apparent predilection for foreign policy and particularly for

multilateralism

In international relations, multilateralism refers to an alliance of multiple countries pursuing a common goal. Multilateralism is based on the principles of inclusivity, equality, and cooperation, and aims to foster a more peaceful, prosperous, an ...

. His

pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

and vision for an "

African renaissance" are central parts of his political persona, and commentators suggest that he secured for South Africa a role in African and global politics that was disproportionate to the country's size and historical influence.

He was the central architect of the

New Partnership for Africa's Development and, as the inaugural chairperson of the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

, spearheaded the introduction of the

African Peer Review Mechanism. After the

IBSA Dialogue Forum

The IBSA Dialogue Forum ( India, Brazil, South Africa) is an international tripartite grouping for promoting international cooperation among these countries. It represents three important poles for galvanizing South–South cooperation and g ...

was launched in 2003, his government collaborated with India and Brazil to lobby for reforms at the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

, advocating for a stronger role for developing countries. Among South Africa's various

peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities, especially military ones, intended to create conditions that favor lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed w ...

commitments during his presidency, Mbeki was the primary mediator in the conflict between

ZANU-PF and the Zimbabwean opposition in the 2000s. However, he was frequently criticised for his policy of "quiet diplomacy" in Zimbabwe, under which he refused to condemn

Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of th ...

's regime or institute sanctions against it.

Also highly controversial worldwide was Mbeki's

HIV/AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

policy. His government did not introduce a national

mother-to-child transmission prevention programme until 2002, when it was mandated by the

Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ru ...

, nor did it make

antiretroviral therapy

The management of HIV/AIDS normally includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs as a strategy to control HIV infection. There are several classes of antiretroviral agents that act on different stages of the HIV life-cycle. The use of mul ...

available in the public

healthcare system

A health system, health care system or healthcare system is an organization of people, institutions, and resources that delivers health care services to meet the health needs of target populations.

There is a wide variety of health systems aroun ...

until late 2003. Subsequent studies have estimated that these delays caused hundreds of thousands of preventable deaths.

Mbeki himself, like his Health Minister

Manto Tshabalala-Msimang

Mantombazana "Manto" Edmie Tshabalala-Msimang Order for Meritorious Service, OMSS (née Mali; 9 October 1940 – 16 December 2009) was a South African politician. She was Deputy Minister of Justice from 1996 to 1999 and served as Minister of He ...

, has been described as an

AIDS denialist, "dissident", or sceptic. Although he did not explicitly deny the causal link between HIV and AIDS, he often posited a need to investigate alternate causes of and alternative treatments for AIDS, frequently suggesting that

immunodeficiency

Immunodeficiency, also known as immunocompromise, is a state in which the immune system's ability to fight infectious diseases and cancer is compromised or entirely absent. Most cases are acquired ("secondary") due to extrinsic factors that aff ...

was the indirect result of poverty.

His political descent began at the ANC's

Polokwane conference in December 2007, when he was replaced as ANC president by Zuma. Although his term as national president was not due to expire until June 2009, he announced on 20 September 2008 that he would resign at the request of the ANC National Executive Committee. The ANC's decision to "recall" Mbeki was understood to be linked to a

High Court judgement, handed down earlier that month, in which judge

Chris Nicholson had alleged improper political interference in the

National Prosecuting Authority and specifically in the

corruption charges against Zuma. Nicholson's judgement was overturned by the

Supreme Court of Appeal in January 2009, by which time Mbeki had been replaced as president by

Kgalema Motlanthe

Kgalema Petrus Motlanthe (; born 19 July 1949) is a South African politician who served as the 3rd president of South Africa from 25 September 2008 to 9 May 2009, following the resignation of Thabo Mbeki. Thereafter, he was deputy president und ...

.

Early life and education

1942–60: Eastern Cape

Mbeki was born on 18 June 1942 in

Mbewuleni, a small village in the former

homeland

A homeland is a place where a national or ethnic identity has formed. The definition can also mean simply one's country of birth. When used as a proper noun, the Homeland, as well as its equivalents in other languages, often has ethnic natio ...

of

Transkei

Transkei ( , meaning ''the area beyond Great Kei River, he riverKei''), officially the Republic of Transkei (), was an list of historical unrecognized states and dependencies, unrecognised state in the southeastern region of South Africa f ...

, now part of the

Eastern Cape

The Eastern Cape ( ; ) is one of the nine provinces of South Africa. Its capital is Bhisho, and its largest city is Gqeberha (Port Elizabeth). Due to its climate and nineteenth-century towns, it is a common location for tourists. It is also kno ...

. The second of four siblings, he had one sister, Linda (born 1941, died 2003), and two brothers,

Moeletsi (born 1945) and Jama (born 1948, died 1982).

His parents were

Epainette (died 2014), a trained teacher, and

Govan

Govan ( ; Cumbric: ''Gwovan''; Scots language, Scots: ''Gouan''; Scottish Gaelic: ''Baile a' Ghobhainn'') is a district, parish, and former burgh now part of southwest Glasgow, Scotland. It is situated west of Glasgow city centre, on the sout ...

(died 2001), a shopkeeper, teacher, journalist, and senior activist in the

African National Congress

The African National Congress (ANC) is a political party in South Africa. It originated as a liberation movement known for its opposition to apartheid and has governed the country since 1994, when the 1994 South African general election, fir ...

(ANC) and the

South African Communist Party

The South African Communist Party (SACP) is a communist party in South Africa. It was founded on 12 February 1921 as the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), and tactically dissolved itself in 1950 in the face of being declared illegal by t ...

(SACP). Both Epainette and Govan came from educated,

Christian

A Christian () is a person who follows or adheres to Christianity, a Monotheism, monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus in Christianity, Jesus Christ. Christians form the largest religious community in the wo ...

, land-owning families, and Govan's father was Sikelewu Mbeki, a colonially appointed

headman.

The couple had met in

Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

, where Epainette had become the second black woman to join the SACP (then still called the Communist Party of South Africa); however, while Mbeki was a child, his family was separated when Govan moved alone to

Ladismith for a teaching job.

Mbeki has said that he was "born into

the struggle", and recalls that his childhood home was decorated with portraits of

Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

and

Mahatma Gandhi

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi (2October 186930January 1948) was an Indian lawyer, anti-colonial nationalism, anti-colonial nationalist, and political ethics, political ethicist who employed nonviolent resistance to lead the successful Indian ...

.

Govan named him after senior South African communist

Thabo Mofutsanyana.

Mbeki began attending school in 1948, the same year that the

National Party was elected with a mandate to legislate

apartheid

Apartheid ( , especially South African English: , ; , ) was a system of institutionalised racial segregation that existed in South Africa and South West Africa (now Namibia) from 1948 to the early 1990s. It was characterised by an ...

.

The

Bantu Education Act

The Bantu ( Blacks ) Education Act 1953 (Act No. 47 of 1953; later renamed the Black Education Act, 1953) was a South African segregation law that legislated for several aspects of the apartheid system. Its major provision enforced racially-separ ...

was implemented towards the end of his school career, and in 1955 he arrived at the

Lovedale Institute, an eminent

mission school

A mission school or missionary school is a religious school originally developed and run by Christian missionaries. The mission school was commonly used in the colonial era for the purposes of Westernization of local people. These may be day s ...

outside

Alice

Alice may refer to:

* Alice (name), most often a feminine given name, but also used as a surname

Literature

* Alice (''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland''), a character in books by Lewis Carroll

* ''Alice'' series, children's and teen books by ...

, as part of the last class which would be permitted to follow the same curriculum as white students. At Lovedale, he was a year behind

Chris Hani

Chris Hani (28 June 194210 April 1993; born Martin Thembisile Hani ) was a South African military commander, politician and revolutionary who served as the leader of the South African Communist Party (SACP) and chief of staff of uMkhonto we S ...

, his future colleague and rival in the ANC.

Mbeki joined the

ANC Youth League

The African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL) is the youth wing of the African National Congress (ANC). As set out in its constitution, the ANC Youth League is led by a National Executive Committee (NEC) and a National Working Committee (N ...

at age fourteen

and in 1958 became the secretary of its Lovedale branch. Shortly afterwards, at the start of his final year of high school, he was identified as one of the leaders of a March 1959

boycott

A boycott is an act of nonviolent resistance, nonviolent, voluntary abstention from a product, person, organisation, or country as an expression of protest. It is usually for Morality, moral, society, social, politics, political, or Environmenta ...

of classes, and was summarily expelled from Lovedale.

He nonetheless sat for

matric

Matriculation is the formal process of entering a university, or of becoming eligible to enter by fulfilling certain academic requirements such as a matriculation examination.

Australia

In Australia, the term ''matriculation'' is seldom used now ...

examinations and obtained a second-class pass.

1960–62: Johannesburg

In June 1960, Mbeki moved to

Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

, where he lived in the home of ANC secretary general

Duma Nokwe and where he intended to sit for

A-level

The A-level (Advanced Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Education, as well as a school leaving qualification offered by the educational bodies in the United Kingdom and the educational ...

examinations. The ANC had recently been banned in the aftermath of the

Sharpeville massacre, but Mbeki remained highly politically active, becoming national secretary of the African Students' Association, a new (and short-lived) youth movement envisaged as replacing the now illegal ANC Youth League. It was also during this period that Nokwe recruited Mbeki into the SACP.

Thus the ANC instructed him to join the growing cohort of cadres who were leaving South Africa to evade police attention, receive training, and establish the overt ANC structures that were now illegal inside the country. Mbeki was detained twice by the police while attempting to leave the country, first in

Rustenberg, when the group he was travelling with failed to pass themselves off as a touring football team, and then in

Rhodesia

Rhodesia ( , ; ), officially the Republic of Rhodesia from 1970, was an unrecognised state, unrecognised state in Southern Africa that existed from 1965 to 1979. Rhodesia served as the ''de facto'' Succession of states, successor state to the ...

.

He arrived at the ANC's new headquarters in

Dar es Salaam

Dar es Salaam (, ; from ) is the largest city and financial hub of Tanzania. It is also the capital of the Dar es Salaam Region. With a population of over 7 million people, Dar es Salaam is the largest city in East Africa by population and the ...

, Tanzania, in November 1962, and left shortly afterwards for England.

Exile and early career

1962–69: England

While at Sussex, Mbeki was involved in ANC work and in broader organising for the English

Anti-Apartheid Movement

The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) was a British organisation that was at the centre of the international movement opposing the South African apartheid system and supporting South Africa's non-white population who were oppressed by the policies ...

. Months after his arrival, his father was arrested during a

Security Branch raid at

Liliesleaf Farm

Liliesleaf Farm, also spelt Lilliesleaf and also known simply as Liliesleaf, is a location in northern Johannesburg, South Africa, which is most noted for its use as a safe house for African National Congress (ANC) activists during the apartheid ...

in July 1963. During the ensuing

Rivonia Trial

The Rivonia Trial was a trial that took place in apartheid-era South Africa between 9 October 1963 and 12 June 1964, after a group of anti-apartheid activists were arrested on Liliesleaf Farm in Rivonia. The farm had been the secret location f ...

, Mbeki appeared before the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN)

Special Committee on Apartheid and later led a student march from Brighton to London, a distance of fifty miles.

At the conclusion of the trial, Govan and seven other ANC leaders, among them

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela ( , ; born Rolihlahla Mandela; 18 July 1918 – 5 December 2013) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and politician who served as the first president of South Africa f ...

and

Walter Sisulu

Walter Max Ulyate Sisulu (18 May 1912 – 5 May 2003) was a South African Internal resistance to apartheid, anti-apartheid activist and member of the African National Congress (ANC). Between terms as ANC Secretary-General (1949–1954) and ANC ...

, were sentenced to

life imprisonment

Life imprisonment is any sentence (law), sentence of imprisonment under which the convicted individual is to remain incarcerated for the rest of their natural life (or until pardoned or commuted to a fixed term). Crimes that result in life impr ...

.

Mbeki completed his bachelor's degree in economics in May 1965 but, at the exhortation of

O. R. Tambo, enrolled for a Master's in economics and

development

Development or developing may refer to:

Arts

*Development (music), the process by which thematic material is reshaped

* Photographic development

*Filmmaking, development phase, including finance and budgeting

* Development hell, when a proje ...

instead of returning to Africa to join

Umkhonto we Sizwe

uMkhonto weSizwe (; abbreviated MK; ) was the paramilitary wing of the African National Congress (ANC), founded by Nelson Mandela in the wake of the Sharpeville massacre. Its mission was to fight against the South African government to brin ...

(MK), the ANC's armed wing. His Master's dissertation was in

economic geography

Economic geography is the subfield of human geography that studies economic activity and factors affecting it. It can also be considered a subfield or method in economics.

Economic geography takes a variety of approaches to many different topi ...

.

In addition to this and his political organising, he developed a deep fondness for

Yeats,

Brecht,

Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 23 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's natio ...

, and

blues music

Blues is a music genre and musical form that originated among African Americans in the Deep South of the United States around the 1860s. Blues has incorporated spiritual (music), spirituals, work songs, field hollers, Ring shout, shouts, cha ...

.

After completing his Master's, in October 1966 he moved to London to work full-time for the

propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded l ...

section of the ANC's English headquarters.

He remained active in the SACP, which was very closely allied to the ANC, and in 1967 he was appointed to the editorial board of its official magazine, the ''

African Communist

''African Communist'' is the magazine of the South African Communist Party, published quarterly. The magazine was started by a group of Marxist-Leninists in 1959. It has its headquarters in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu languag ...

''.

Throughout his time in England, Mbeki was the ward of O. R. Tambo and his wife

Adelaide Tambo – in the absence of his parents, it was Adelaide and senior communist

Michael Harmel who attended Mbeki's graduation ceremony in 1965.

O. R. Tambo later became the ANC's longest-serving president, and he acted as Mbeki's "political mentor and patron" until his death in 1993. Other friends Mbeki made in England, including

Ronnie Kasrils and brothers

Essop Pahad and

Aziz Pahad, were also among his key political allies in his later career.

1969–71: Soviet Union

In February 1969, Mbeki was sent to

Moscow

Moscow is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Russia by population, largest city of Russia, standing on the Moskva (river), Moskva River in Central Russia. It has a population estimated at over 13 million residents with ...

in the

Soviet Union

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

to receive

Marxist–Leninist political and ideological training – a fairly common practice, and even a rite of passage, among young people identified as belonging to the future generation of ANC and SACP political leaders. He was educated at the

Lenin Institute, where, because of the secrecy required, he went by the alias "Jack Fortune".

He excelled at the institute and in June 1970 was appointed to the

Central Committee of the SACP, alongside Chris Hani.

The last part of his training entailed military training, also a rite of passage, including in intelligence,

guerrilla

Guerrilla warfare is a form of unconventional warfare in which small groups of irregular military, such as rebels, Partisan (military), partisans, paramilitary personnel or armed civilians, which may include Children in the military, recruite ...

tactics, and weaponry. However, his biographer

Mark Gevisser

Mark Gevisser (born 1964) is a South African author and journalist. His latest book is ''The Pink Line: Journeys Across the World's Queer Frontiers'' (2020). Previous books include ''A Legacy of Liberation: Thabo Mbeki and the Future of the Sou ...

adduces that he was "not the ideal candidate for military life", and

Max Sisulu, who trained alongside him, says that he always regarded Mbeki as better suited to political leadership than military leadership.

1971–75: Lusaka

In April 1971, having been pulled out from military training, Mbeki was sent to

Lusaka

Lusaka ( ) is the Capital city, capital and largest city of Zambia. It is one of the fastest-developing cities in southern Africa. Lusaka is in the southern part of the central plateau at an elevation of about . , the city's population was abo ...

, Zambia, where the ANC-in-exile had set up its new headquarters under acting president Tambo. He was to fill the post of administrative secretary to the ANC

Revolutionary Council, a body newly established to coordinate the political and military efforts of the ANC and SACP.

He was later moved to the propaganda section, but continued to attend the council's meetings, and in 1975 he (again alongside Hani) was elected onto the ANC's top decision-making organ, the

National Executive Committee.

It was during this period that he began to

ghostwrite some of Tambo's speeches and reports, and he accompanied Tambo on important occasions, such as to the infamous December 1972 meeting with

Mangosuthu Buthelezi

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi (; 27 August 1928 – 9 September 2023) was a South African politician and Zulu people, Zulu prince who served as the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family from 1954 until his death in 2023. He ...

, the head of

Inkatha, in London.

In 1973, he helped to establish the ANC's office in Botswana, considered a "frontline" country because of its shared border with South Africa, where the ANC was attempting to re-establish its underground.

However, although he travelled frequently in subsequent years, the ANC's Lusaka headquarters remained his central base.

1975–76: Swaziland

Between 1975 and 1976, Mbeki was instrumental in establishing the ANC's frontline base in Swaziland. He was first sent there to assess the political landscape in January 1975, under the cover of attending a UN conference. As part of this reconnaissance trip, he and his colleague Max Sisulu spent time with

S'bu Ndebele, Max's sister

Lindiwe Sisulu, and their associates in the

Black Consciousness movement

The Black Consciousness Movement (BCM) was a grassroots anti-apartheid activist movement that emerged in South Africa in the mid-1960s out of the political vacuum created by the jailing and banning of the African National Congress and Pan Af ...

, which at the time was ascendent in neighbouring South Africa.

Mbeki made a positive report to the ANC executive, and he was sent back to Swaziland to begin establishing the base. In Swaziland, he lived at Stanley Mabizela's family home in

Manzini. Working with Albert Dhlomo, Mbeki was responsible for helping to re-establish underground ANC networks in the South African provinces of

Natal and

Transvaal, which shared a border with Swaziland. His counterpart inside South Africa was MK operative

Jacob Zuma

Jacob Gedleyihlekisa Zuma (; born 12 April 1942) is a South African politician who served as the fourth president of South Africa from 2009 to 2018. He is also referred to by his initials JZ and clan names Nxamalala and Msholozi. Zuma was a for ...

, who ran the Natal underground. According to Gevisser, the pair developed "an unlikely rapport".

Mbeki was also responsible for recruiting new MK operatives, for liaising with South African student and labour activists, and for liaising with Inkatha, which was becoming dominant in Natal.

However, still another part of his duties was to act as the ANC's official representative in the country, and to maintain good diplomatic relations with the Swazi government. In March 1976, the government discovered that Mbeki was involved in military activity inside Swaziland, and he and Dhlomo – as well as Zuma, who was in the country illegally – were detained and then

deported, though they managed to negotiate their deportation to the neutral territory of Mozambique rather than to South Africa.

Mbeki's management of the Swaziland base later became a point of contention between him and

Mac Maharaj

Sathyandranath Ragunanan "Mac" Maharaj OLS (born 22 April 1935 in Newcastle, Natal) is a retired South African-Indian politician, businessman, and former anti-apartheid activist. A member of the African National Congress (ANC), he was the ...

, with whom his relationship has remained acrimonious decades later. In 1978, Maharaj and Mbeki argued at a top-level strategic meeting in

Luanda

Luanda ( ) is the Capital city, capital and List of cities and towns in Angola, largest city of Angola. It is Angola's primary port, and its major industrial, cultural and urban centre. Located on Angola's northern Atlantic coast, Luanda is Ang ...

, Angola, when Maharaj, who had been tasked with running the political underground, claimed that Mbeki's records from the Swaziland office were in fact "just an empty folder".

1976–78: Nigeria

After being deported, Mbeki returned to Lusaka, where he was made Duma Nokwe's deputy in the ANC's Department of Information and Propaganda (DIP). In January 1977, he was posted to

Lagos

Lagos ( ; ), or Lagos City, is a large metropolitan city in southwestern Nigeria. With an upper population estimated above 21 million dwellers, it is the largest city in Nigeria, the most populous urban area on the African continent, and on ...

, Nigeria, where he was to be – as in Swaziland – the ANC's first representative to the country. Although there was some debate about whether the appointment was a signal that he had been sidelined, Gevisser says that Mbeki performed well in Lagos, establishing good relations with

Olusegun Obasanjo

Chief Olusegun Matthew Okikiola Ogunboye Aremu Obasanjo (; ; born 5 March 1937) is a Nigerian former army general, politician and statesman who served as Nigeria's head of state from 1976 to 1979 and later as its president from 1999 to 200 ...

's regime and establishing an ANC presence to eclipse that of its rival

Pan Africanist Congress

The Pan Africanist Congress of Azania, often shortened to the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC), is a South African pan-Africanist national liberation movement that is now a political party. It was founded by an Africanist group, led by Robert So ...

(PAC).

1978–80: Political secretary

When he returned to Lusaka from Lagos in 1978, he was promoted again: he replaced Nokwe as head of DIP, and simultaneously was appointed Tambo's political secretary, an extremely influential position in which he became one of Tambo's closest advisors and confidantes. He also continued to ghostwrite for Tambo, now in a formal capacity.

At DIP, his approach was encapsulated by the change he made to the department's name, replacing "propaganda" with "publicity". He eschewed the secrecy of earlier years and openly gave interviews and access to American journalists, to the disapproval of some hardline communists. According to various sources, he was responsible for reforming the public image of the ANC from that of a

terrorist

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of violence against non-combatants to achieve political or ideological aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violence during peacetime or in the context of war aga ...

organisation to that of a "government-in-waiting".

He established some of his own high-level intelligence networks, with key underground operatives reporting directly to him, and Gevisser claims that these led to the initiation of relationships with many of the domestic activists who later became his political allies. Moreover, he was responsible for innovating some of the vocabulary which became emblematic of the 1980s anti-apartheid struggle, which burgeoned in the aftermath of the

1976 Soweto uprising

The Soweto uprising, also known as the Soweto riots, was a series of demonstrations and protests led by black school children in South Africa during apartheid that began on the morning of 16 June 1976.

Students from various schools began to p ...

. Such phrases as "mass democratic movement", "people's power", and the exhortation to "

make the country ungovernable" are attributed to Mbeki, and gained widespread popularity inside South Africa through

Radio Freedom broadcasts written by DIP or by Mbeki personally.

Zuma has said that it was Mbeki's "drafting skills" which enabled his ascendancy in the ANC and ultimately to the presidency.

In 1980, Mbeki led the ANC's delegation to Zimbabwe, where the party hoped to establish relations with

Robert Mugabe

Robert Gabriel Mugabe (; ; 21 February 1924 – 6 September 2019) was a Zimbabwean revolutionary and politician who served as Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 1980 to 1987 and then as President from 1987 to 2017. He served as Leader of th ...

's newly elected government. This was a sensitive mission, because the ANC had historically been strongly allied to the

Zimbabwe African People's Union

The Zimbabwe African People's Union (ZAPU) is a Zimbabwean political party. It is a militant communist organization and political party that campaigned for majority rule in Rhodesia, from its founding in 1961 until 1980. In 1987, it merged with ...

, the arch rival of Mugabe's

ZANU-PF. Working primarily through Mugabe's righthand man, future Zimbabwean president

Emmerson Mnangagwa, Mbeki negotiated an extraordinarily congenial agreement between ZANU-PF and the ANC. The agreement allowed the ANC to open an office in Zimbabwe and to move MK weapons and cadres over Zimbabwean borders; moreover, it committed the Zimbabwean military to assisting the ANC, and the government to providing MK cadres with Zimbabwean identity documents.

However, Mbeki handed the running of the

Salisbury

Salisbury ( , ) is a city status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and civil parish in Wiltshire, England with a population of 41,820, at the confluence of the rivers River Avon, Hampshire, Avon, River Nadder, Nadder and River Bourne, Wi ...

office over to another ANC official, and the deal later collapsed.

1980s: Negotiations

In 1985,

PW Botha declared a State of Emergency and gave the army and police special powers. In 1986, the South African Army sent a captain in the South African Defence Force (SADF) to kill Mbeki. The plan was to put a bomb in his house in Lusaka, but the assassin was arrested by the Zambian police before he could go through with the plan. Also in 1985, Mbeki became the ANC's director of the Department of Information and Publicity and coordinated diplomatic campaigns to involve more white South Africans in anti-apartheid activities. In 1989, he rose in the ranks to head the ANC's Department of International Affairs and was involved in the ANC's negotiations with the South African government. Mbeki played a major role in turning the international media against apartheid. Raising the diplomatic profile of the ANC, Mbeki acted as a point of contact for foreign governments and international organisations and he was extremely successful in this position. Mbeki also played the role of ambassador to the steady flow of delegates from the elite sectors of white South Africa. These included academics, clerics, business people and representatives of liberal white groups who travelled to Lusaka to assess the ANC's views on a democratic, free South Africa.

Mbeki was seen as pragmatic, eloquent, rational, and urbane. He was known for his diplomatic style and sophistication. In the early 1980s, Mbeki, Jacob Zuma and

Aziz Pahad were appointed by Tambo to conduct private talks with representatives of the

National Party government. Twelve meetings between the parties took place between November 1987 and May 1990, most of them held at

Mells Park House, a country house near

Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

in Somerset,

England

England is a Countries of the United Kingdom, country that is part of the United Kingdom. It is located on the island of Great Britain, of which it covers about 62%, and List of islands of England, more than 100 smaller adjacent islands. It ...

. By September 1989, the team secretly met with Maritz Spaarwater and

Mike Louw in a hotel in

Switzerland

Switzerland, officially the Swiss Confederation, is a landlocked country located in west-central Europe. It is bordered by Italy to the south, France to the west, Germany to the north, and Austria and Liechtenstein to the east. Switzerland ...

. Known as "Operation Flair",

PW Botha was kept informed of all the meetings. At the same time, Mandela and

Kobie Coetzee, the Minister of Justice, were also holding secret talks. When Mbeki finally was able to return home to South Africa and was reunited with his own father, the elder Mbeki told a reporter, "You must remember that Thabo Mbeki is no longer my son. He is my comrade!" A news article pointed out that this was an expression of pride, explaining, "For Govan Mbeki, a son was a mere biological appendage; to be called a comrade, on the other hand, was the highest honour."

In the late 1970s, Mbeki made a number of trips to the United States in search of support among US corporations. Literate and funny, he made a wide circle of friends in New York City. Mbeki was appointed head of the ANC's information department in 1984 and then became head of the international department in 1989, reporting directly to

Oliver Tambo

Oliver Reginald Kaizana Tambo (27 October 191724 April 1993) was a South African anti-apartheid politician and activist who served as President of the African National Congress (ANC) from 1967 to 1991.

Biography Childhood

Oliver Tambo was ...

, then President of the ANC. Tambo was Mbeki's long-time mentor. In 1985, Mbeki was a member of a delegation that began meeting secretly with representatives of the South African business community, and in 1989, he led the ANC delegation that conducted secret talks with the South African government. These talks led to the unbanning of the ANC and the release of political prisoners. He also participated in many of the other important

negotiations

Negotiation is a dialogue between two or more parties to resolve points of difference, gain an advantage for an individual or Collective bargaining, collective, or craft outcomes to satisfy various interests. The parties aspire to agree on m ...

between the ANC and the government that eventually led to the democratisation of South Africa.

As a sign of goodwill, de Klerk set free a few of the ANC's top leadership at the end of 1989, among them

Govan Mbeki

Govan Archibald Mvunyelwa Mbeki (9 July 1910 – 30 August 2001) was a South African politician, military commander, Communist leader who served as the Secretary of Umkhonto we Sizwe, at its inception in 1961. He was also the younger son of Ch ...

.

Rise to the presidency

On 2 February 1990, Botha's successor as state president,

F. W. de Klerk

Frederik Willem de Klerk ( , ; 18 March 1936 – 11 November 2021) was a South African politician who served as the seventh and final state president of South Africa from 1989 to 1994 and as Deputy President of South Africa, deputy president a ...

, announced that the ANC and other political organisations would be unbanned, and ANC exiles began to return to South Africa. At the same time that it was to

negotiate the end of apartheid, the ANC had to implement a significant internal reorganisation, absorbing into its official exile bodies the domestic ANC underground, released political prisoners, and other activists from the trade unions and the

United Democratic Front. It also had an ageing leadership, meaning that a new generation of leaders had to be prepared for succession.

1993: ANC chairperson

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, Mbeki's key role in the early negotiations made him a likely contender for top leadership positions in the party, and he was even considered to be in line for the ANC presidency.

However, at the ANC's

48th National Conference in July 1991, its first

national elective conference since 1960, Mbeki was not elected to any of the "Top Six" leadership positions. Sisulu was elected ANC deputy president, almost certainly as a compromise candidate, and trade unionist

Cyril Ramaphosa

Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa (born 17 November 1952) is a South African businessman and politician serving as the 5th and current President of South Africa since 2018. A former Anti-Apartheid Movement, anti-apartheid activist and trade union leade ...

was elected secretary general.

According to historian Tom Lodge, Ramaphosa's election was a putsch carried out by the party's "internal wing", in defiance of the former exiles and political prisoners who had hitherto dominated the ANC's leadership.

Over the next three years, Ramaphosa also came to eclipse Mbeki as the party's central negotiator when he, not Mbeki, was appointed to lead the ANC's delegation to the

CODESA talks. Once SACP leader

Chris Hani

Chris Hani (28 June 194210 April 1993; born Martin Thembisile Hani ) was a South African military commander, politician and revolutionary who served as the leader of the South African Communist Party (SACP) and chief of staff of uMkhonto we S ...

was assassinated in April 1993, Ramaphosa became Mbeki's primary competition in the ANC succession battle.

When Tambo died later the same month, Mbeki succeeded him as ANC national chairperson.

1994: Deputy president

Following the

1994 elections

The following elections occurred in the year 1994.

Africa

* 1994 Botswana general election

* 1994 Guinea-Bissau general election

* 1994 Malawian general election

* 1994 Mozambican general election

* 1994 Namibian general election

* 1994 South Afr ...

, South Africa's first under

universal suffrage

Universal suffrage or universal franchise ensures the right to vote for as many people bound by a government's laws as possible, as supported by the " one person, one vote" principle. For many, the term universal suffrage assumes the exclusion ...

, Mbeki became one of the two national

deputy presidents in the ANC-led

Government of National Unity, in which Mandela was president. At the ANC's

next national conference, held in December that year, Mbeki was elected unopposed to the ANC deputy presidency, also under Mandela.

In June 1996, the

National Party withdrew from the Government of National Unity and, with the second deputy, de Klerk, having thereby resigned, Mbeki became the sole deputy president.

The same year, as deputy president, Mbeki acted as a peace broker in what was then known as

Zaire

Zaire, officially the Republic of Zaire, was the name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1971 to 18 May 1997. Located in Central Africa, it was, by area, the third-largest country in Africa after Sudan and Algeria, and the 11th-la ...

, following the

First Congo War

The First Congo War, also known as Africa's First World War, was a Civil war, civil and international military conflict that lasted from 24 October 1996 to 16 May 1997, primarily taking place in Zaire (which was renamed the Democratic Republi ...

and the deposition of Zairean president

Mobutu Sese Seko

Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu wa za Banga ( ; born Joseph-Désiré Mobutu; 14 October 1930 – 7 September 1997), often shortened to Mobutu Sese Seko or Mobutu and also known by his initials MSS, was a Congolese politician and military officer ...

.

Mbeki also took on increasing domestic responsibilities, including executive powers delegated to him by Mandela, to such an extent that Mandela called him "a ''de facto'' president".

Mandela had made it clear publicly since early 1995 or earlier that he intended to retire after one term in office, and by then Mbeki was already seen as his most likely successor.

1997: ANC president

In December 1997, the ANC's

50th National Conference elected Mbeki unopposed to succeed Mandela as ANC president. On some accounts, the election was not contested because the top leadership had prepared assiduously for the conference, lobbying and negotiating on Mbeki's behalf in the interest of unity and continuity.

Pursuant to the

1999 national elections, which the ANC won by a significant majority, Mbeki was elected

president of South Africa

The president of South Africa is the head of state and head of government of the Republic of South Africa. The president directs the executive branch of the government and is the commander-in-chief of the South African National Defence F ...

. He was re-elected for a second term in 2002.

Presidency of South Africa

Economic policy

Mbeki had been highly involved in economic policy as deputy president, especially in spearheading the

Growth, Employment and Redistribution (GEAR) programme, which was introduced in 1996 and remained a cornerstone of Mbeki's administration after 1999.

In comparison to the

Reconstruction and Development Programme policy which had been the basis of the ANC's platform in 1994, GEAR placed less emphasis on developmental and redistributive imperatives, and subscribed to elements of the liberalisation, deregulation, and privatisation at the centre of

Washington Consensus

The Washington Consensus is a set of ten economic policy prescriptions considered in the 1980s and 1990s to constitute the "standard" reform package promoted for Economic crisis, crisis-wracked developing country, developing countries by the Was ...

-style reforms.

It was therefore viewed by some as a "policy reversal" and embrace of

neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pe ...

, and thus as an abandonment of the ANC's

socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

principles.

Mbeki also emphasised communication between government, business, and labour, establishing four working groups – for big business, black business, trade unions, and commercial agriculture – under which ministers, senior officials, and Mbeki himself met regularly with business and union leaders to build trust and explore solutions to structural economic problems.

Conservative groups such as the

Cato Institute

The Cato Institute is an American libertarian think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1977 by Ed Crane, Murray Rothbard, and Charles Koch, chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Koch Industries.Koch ...

commended Mbeki's macroeconomic policies, which reduced the

budget deficit

Within the budgetary process, deficit spending is the amount by which spending exceeds revenue over a particular period of time, also called simply deficit, or budget deficit, the opposite of budget surplus. The term may be applied to the budg ...

and

public debt

A country's gross government debt (also called public debt or sovereign debt) is the financial liabilities of the government sector. Changes in government debt over time reflect primarily borrowing due to past government deficits. A deficit occu ...

and which according to them likely played a role in increasing economic growth.

According to the

Free Market Foundation, during the Mbeki presidency, average annualised quarter-on-quarter GDP growth was 4.2%, and average annual inflation was 5.7%.

On the other hand, the shift alienated leftists, including inside in the ANC and its

Tripartite Alliance

The Tripartite Alliance is an alliance between the African National Congress (ANC), the Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) and the South African Communist Party (SACP). The ANC holds a plurality in the South African parliament, ...

.

of the

Congress of South African Trade Unions (COSATU) was an outspoken critic of Mbeki's "market-friendly" economic policies, claiming that Mbeki's "flirtation" with neoliberalism had been "absolutely disastrous" for development, and especially for the labour-intensive development required to address South Africa's high unemployment rate. The discord between Mbeki and the left was on public display by December 2002, when Mbeki attacked what he called divisive "ultra-leftists" in a speech to the ANC's

51st National Conference.

However, Mbeki clearly never subscribed to undiluted neoliberalism. He retained various

social democratic

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

programmes and principles, and generally endorsed a

mixed economy

A mixed economy is an economic system that includes both elements associated with capitalism, such as private businesses, and with socialism, such as nationalized government services.

More specifically, a mixed economy may be variously de ...

in South Africa.

One of the ANC's slogans in the campaign for his

2004 re-election was, "A people's contract for growth and development."

He popularised the concept of a dual or two-track economy in South Africa, with severe underdevelopment in one segment of the population, and, for example in a 2003 newsletter, argued that high growth alone would only benefit the developed segment, without significant

trickle-down benefits for the rest of the population.

Yet, somewhat paradoxically, he explicitly advocated state support for the creation of a black capitalist class in South Africa.

The government's

black economic empowerment policy, which was expanded and consolidated under his administration, was criticised precisely for benefitting only a small black elite and thereby failing to address

inequality.

Foreign policy

According to academic and diplomat

Gerrit Olivier, during his presidency Mbeki "succeeded in placing Africa high on the global agenda."

He was known for his

pan-Africanism

Pan-Africanism is a nationalist movement that aims to encourage and strengthen bonds of solidarity between all Indigenous peoples of Africa, indigenous peoples and diasporas of African ancestry. Based on a common goal dating back to the Atla ...

, having emphasised related themes both in his famous "

I am an African" speech in 1996 and in his first speech to

Parliament

In modern politics and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

as president in June 1999, when he foregrounded his trademark ideal of an "

African renaissance". He advocated for greater solidarity among African countries and, in place of reliance on Western intervention and aid, for greater self-sufficiency for the African continent. Simultaneously, however, he argued for increased

developmental aid to Africa.

He called for Western leaders to address

global apartheid and unequal development, most memorably in a speech to the

World Summit on Sustainable Development

The World Summit on Sustainable Development 2002, took place in South Africa, from 26 August to 4 September 2002. It was convened to discuss sustainable development organizations, 10 years after the first Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro. (It was t ...

in

Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu language, Zulu and Xhosa language, Xhosa: eGoli ) (colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, Jo'burg or "The City of Gold") is the most populous city in South Africa. With 5,538,596 people in the City of Johannesburg alon ...

in August 2002.

Africa

Although Mbeki also forged strategic individual relationships with key African leaders, especially the heads of state of Nigeria, Algeria, Mozambique, and Tanzania,

perhaps his central foreign policy instrument was

multilateral cooperation. Mbeki's government, and Mbeki personally, are frequently cited as the single most significant driving force behind the creation in 2001 of the

New Partnership for Africa's Development (NEPAD), which aims to develop a framework for accelerating economic development and cooperation in Africa.

Olivier calls Mbeki the "seminal thinker" behind NEPAD and its "principal author and articulator".

According to academic Chris Landsberg, NEPAD's central principle – "African leaders holding one another accountable in exchange for the recommitment of the industrialised world to Africa's development" – epitomised Mbeki's strategy in Africa.

Mbeki was also involved in the dissolution of the

Organisation of African Unity

The Organisation of African Unity (OAU; , OUA) was an African intergovernmental organization established on 25 May 1963 in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 33 signatory governments. Some of the key aims of the OAU were to encourage political and ec ...

and its replacement by the

African Union

The African Union (AU) is a continental union of 55 member states located on the continent of Africa. The AU was announced in the Sirte Declaration in Sirte, Libya, on 9 September 1999, calling for the establishment of the African Union. The b ...

(AU), of which he became the

inaugural chairperson in 2002, and his government spearheaded the introduction of the AU's

African Peer Review Mechanism in 2003.

He was twice chairperson of the

Southern African Development Community

The Southern African Development Community (SADC) is an inter-governmental organization headquartered in Gaborone, Botswana.

Goals

The SADC's goal is to further regional socio-economic cooperation and integration as well as political and se ...

(SADC), first from 1999 to 2000 and second, briefly, in 2008. Through these multilateral organisations and by contributing forces to various

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the Earth, global intergovernmental organization established by the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter on 26 June 1945 with the stated purpose of maintaining international peace and internationa ...

(UN) peacekeeping missions, Mbeki and his government were involved in

peacekeeping

Peacekeeping comprises activities, especially military ones, intended to create conditions that favor lasting peace. Research generally finds that peacekeeping reduces civilian and battlefield deaths, as well as reduces the risk of renewed w ...

initiatives in African countries including Zimbabwe, Ethiopia and Eritrea, Liberia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Burundi.

Global South

Outside Africa, Mbeki was the chairperson of the

Non-Aligned Movement

The Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) is a forum of 121 countries that Non-belligerent, are not formally aligned with or against any major power bloc. It was founded with the view to advancing interests of developing countries in the context of Cold W ...

between 1999 and 2003 and the chairperson of the

Group of 77

The Group of 77 (G77) at the United Nations (UN) is a coalition of developing country, developing countries, designed to promote its members' collective economic interests and create an enhanced joint negotiating capacity in the United Nations. T ...

+ China in 2006.

He also pursued

South

South is one of the cardinal directions or compass points. The direction is the opposite of north and is perpendicular to both west and east.

Etymology

The word ''south'' comes from Old English ''sūþ'', from earlier Proto-Germanic ''*sunþa ...

-South solidarity in a coalition with India and Brazil under the

IBSA Dialogue Forum

The IBSA Dialogue Forum ( India, Brazil, South Africa) is an international tripartite grouping for promoting international cooperation among these countries. It represents three important poles for galvanizing South–South cooperation and g ...

, which was launched in June 2003 and held its first summit in September 2006.

The IBSA countries together pressed for changes in the agricultural subsidy regimes of developed countries at the

2003 World Trade Organisation conference, and also pressed for reforms at the UN which would allow developing countries a stronger role.

Indeed, Mbeki had called for reform at the UN as early as 1999 and 2000.

In 2007, following a prolonged diplomatic campaign,

South Africa secured a non-permanent seat on the

UN Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, an ...

for a two-year term.

Controversially, in February 2007, South Africa followed Russia and China in voting against a draft resolution calling for an end to political detentions and military attacks against ethnic minorities in Myanmar.

Mbeki later told the media that the resolution exceeded the Security Council's mandate, and that its tabling had been illegal in terms of

international law

International law, also known as public international law and the law of nations, is the set of Rule of law, rules, norms, Customary law, legal customs and standards that State (polity), states and other actors feel an obligation to, and generall ...

.

Quiet diplomacy in Zimbabwe

Mbeki's presidency coincided with an escalating political and economic crisis in South Africa's neighbour, Zimbabwe, under president Mugabe of ZANU-PF. Problems included land invasions under the

"fast-track" land reform programme,

political violence

Political violence is violence which is perpetrated in order to achieve political goals. It can include violence which is used by a State (polity), state against other states (war), violence which is used by a state against civilians and non-st ...

and state-sponsored human rights violations, and

hyperinflation

In economics, hyperinflation is a very high and typically accelerating inflation. It quickly erodes the real versus nominal value (economics), real value of the local currency, as the prices of all goods increase. This causes people to minimiz ...

.

With SADC's endorsement, Mbeki frequently acted as a mediator between ZANU-PF and the Zimbabwean opposition. However, controversially, his policy towards the Mugabe regime was one of non-confrontational "quiet diplomacy" and "constructive engagement": he refused to condemn Mugabe and instead attempted to persuade him to accept gradual political reforms.

He was firmly opposed to forcible or manufactured

regime change

Regime change is the partly forcible or coercive replacement of one government regime with another. Regime change may replace all or part of the state's most critical leadership system, administrative apparatus, or bureaucracy. Regime change may ...

in Zimbabwe, and also opposed the use of sanctions.

The ''

Economist

An economist is a professional and practitioner in the social sciences, social science discipline of economics.

The individual may also study, develop, and apply theories and concepts from economics and write about economic policy. Within this ...

'' posited an "Mbeki doctrine" holding that South Africa "cannot impose its will on others, but it can help to deal with instability in African countries by offering its resources and its leadership to bring rival groups together, and to keep things calm until an election is safely held." Mbeki said in 2004:The motives behind Mbeki's Zimbabwe policy have been interpreted in various ways: for example, some suggest that he was attempting to maintain economic stability in Zimbabwe and therefore to protect South African economic interests, while others cite his attachment to ideals of African solidarity and opposition to what he perceived as quasi-

imperial Western interference in Africa.

In any case, Mbeki's policy on Zimbabwe attracted widespread criticism both domestically and internationally.

Some also questioned Mbeki's neutrality in his role as mediator.

After a South African

observer mission endorsed the result of the Zimbabwean

presidential election of 2002, in which Mugabe was re-elected,

Zimbabwean opposition leader

Morgan Tsvangirai

Morgan Richard Tsvangirai (; ; 10 March 1952 – 14 February 2018) was a Zimbabwean politician who was Prime Minister of Zimbabwe from 2009 to 2013. He was president of the Movement for Democratic Change, and later the Movement for Democrati ...

accused Mbeki of being a "dishonest broker" and his government of becoming "part of the Zimbabwe problem because its actions are worsening the crisis."

Commentators later said that Mbeki's soft stance on Mugabe during this period permanently damaged relations between South Africa and the Zimbabwean opposition.

A South African government observer mission also endorsed the result of the Zimbabwean

parliamentary elections of 2005, apparently leading Tsvangirai's party, the

Movement for Democratic Change (MDC), to effectively sever relations with Mbeki's administration.

Power-sharing negotiations

Following

another contested election in Zimbabwe – after which Mbeki controversially denied that there was a "crisis" in Zimbabwe – the MDC and ZANU-PF

entered into negotiations towards the formation of a power-sharing government, with talks beginning in July 2008. Mbeki mediated the negotiations and brokered the resulting power-sharing agreement, signed on 15 September 2008, which retained Mugabe as president but diluted his executive power across posts to be held by opposition leaders.

HIV/AIDS

Policy and treatment

According to political scientist

Jeffrey Herbst

Jeffrey I. Herbst is an American political scientist, specializing in comparative politics, and was the fourth president of the American Jewish University in Los Angeles, California from July 2018 to May 2025. Herbst was previously the 16th pr ...

, Mbeki's HIV/AIDS policies were "bizarre at best, severely negligent at worst."

In 2000, amid a burgeoning

HIV/AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

epidemic in South Africa, Mbeki's government launched the ''HIV/AIDS/

STD Strategic Plan for South Africa, 2000–2005'', a "multi-sectoral" plan which was criticised by HIV/AIDS activists for lacking concrete timeframes and failing to commit to

antiretroviral treatment

The management of HIV/AIDS normally includes the use of multiple antiretroviral drugs as a strategy to control HIV infection. There are several classes of antiretroviral agents that act on different stages of the HIV life-cycle. The use of mul ...

programmes.

Indeed, according to economist

Nicoli Nattrass, resistance to the roll-out of antiretroviral drugs for prevention and treatment became central to the HIV/AIDS policy of Mbeki's government in subsequent years.

A national

mother-to-child transmission prevention programme was not introduced until 2002, when it was mandated by the

Constitutional Court

A constitutional court is a high court that deals primarily with constitutional law. Its main authority is to rule on whether laws that are challenged are in fact unconstitutional, i.e. whether they conflict with constitutionally established ru ...

in response to a successful legal challenge by the

Treatment Action Campaign. Similarly, chronic highly active antiretroviral therapy for AIDS-sick people was not introduced in the public

healthcare system

A health system, health care system or healthcare system is an organization of people, institutions, and resources that delivers health care services to meet the health needs of target populations.

There is a wide variety of health systems aroun ...

until late 2003, reportedly at the insistence of some members of

Mbeki's cabinet.

According to Nattrass, better access to antiretroviral drugs in South Africa could have prevented about 171,000 HIV infections and 343,000 deaths between 1999 and 2007.

In November 2008, a

Harvard University

Harvard University is a Private university, private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States. Founded in 1636 and named for its first benefactor, the History of the Puritans in North America, Puritan clergyma ...

study estimated that more than 330,000 people died between 2000 and 2005 due to insufficient antiretroviral programmes under Mbeki's government.

Even after these programmes were introduced, Mbeki's appointee as Minister of Health,

Manto Tshabalala-Msimang

Mantombazana "Manto" Edmie Tshabalala-Msimang Order for Meritorious Service, OMSS (née Mali; 9 October 1940 – 16 December 2009) was a South African politician. She was Deputy Minister of Justice from 1996 to 1999 and served as Minister of He ...

, continued to advocate publicly for unproven alternative treatments in place of antiretrovirals, leading to continual calls by civil society for her dismissal.

In late 2006,

the cabinet transferred responsibility for AIDS policy from Tshabalala-Msimang to Deputy President

Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka, who subsequently spearheaded a new draft National Strategic Plan on HIV/AIDS.

Association with denialism

While president, Mbeki was also criticised for his public messaging on

HIV/AIDS

The HIV, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a retrovirus that attacks the immune system. Without treatment, it can lead to a spectrum of conditions including acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). It is a Preventive healthcare, pr ...

. He was viewed as sympathetic to or influenced by the views of a small minority of scientists who challenged the scientific consensus that HIV caused AIDS and that

antiretroviral drugs were the most effective means of treatment. In an April 2000 letter to UN secretary-general

Kofi Annan

Kofi Atta Annan (8 April 193818 August 2018) was a Ghanaian diplomat who served as the seventh secretary-general of the United Nations from 1997 to 2006. Annan and the UN were the co-recipients of the 2001 Nobel Peace Prize. He was the founder a ...

and the heads of state of the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, and France, Mbeki pointed to differences in how the AIDS epidemic had manifested in Africa and in the West, and committed to "the search for specific and targeted responses to the specifically African incidence of HIV-AIDS."

He also defended scientists who had challenged the scientific consensus on AIDS: The letter was leaked to ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'', locally known as ''The'' ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'' or ''WP'', is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C., the national capital. It is the most widely circulated newspaper in the Washington m ...

'' and caused controversy. During the same period, Mbeki convened a panel to investigate the cause of AIDS, staffed by researchers who believed that AIDS was caused by malnutrition and parasites as well as by orthodox researchers. In July 2000, opening the

13th International AIDS Conference in

Durban

Durban ( ; , from meaning "bay, lagoon") is the third-most populous city in South Africa, after Johannesburg and Cape Town, and the largest city in the Provinces of South Africa, province of KwaZulu-Natal.

Situated on the east coast of South ...

, he proposed that the "disturbing phenomenon of the

collapse of immune systems among millions of our people" was the result of various factors, especially poverty, and that "we could not blame everything on a single virus." It was characteristic of Mbeki's stance on HIV/AIDS to draw attention to socioeconomic differences between the West and Africa, emphasising the importance of poverty in poor health outcomes in Africa, and to insist that African countries should not be asked blindly to accept Western scientific theories and policy models. Commentators speculate that his stance was motivated by suspicion of the West and was a response to what he perceived as

racist stereotypes of the continent and its people.

For example, in October 2001, in a speech at the

University of Fort Hare

The University of Fort Hare () is a public university in Alice, Eastern Cape, Alice, Eastern Cape, South Africa.

It was a key institution of higher education for Africans from 1916 to 1959 when it offered a Western-style academic education to ...

, he said of the West: "Convinced that we are but natural-born, promiscuous carriers of germs, unique in the world, they proclaim that our continent is doomed to an inevitable mortal end because of our unconquerable devotion to the sin of lust."

Mbeki announced in October 2000 that he would withdraw from the public debate on HIV/AIDS science,

and in 2002 his cabinet staunchly affirmed that HIV causes AIDS. However, critics claimed that he continued to influence – and impede – HIV/AIDS policy, a charge which Mbeki denied.

AIDS activist

Zackie Achmat said in 2002 that "Mbeki epitomizes leadership in denial and his stand has fuelled government inaction."

Gevisser writes that in 2007 Mbeki continued to defend his position on HIV/AIDS, and directed Gevisser to a controversial and anonymous ANC discussion document titled

''Castro Hlongwane, Caravans, Cats, Geese, Foot & Mouth and Statistics: HIV/Aids and the Struggle for the Humanisation of the African''.

The Gevisser biography also says that, while Mbeki never explicitly

denied the link between HIV and AIDS, he is a "profound sceptic"

– as Mbeki himself wrote in 2016, in a newsletter cautioning "great care and caution" in the use of antiretrovirals, he had not denied that HIV caused AIDS but that "a virus

ouldcause a syndrome." He is generally referred to as an HIV/AIDS "dissident" rather than an outright denialist, although Nattrass questions the value of that distinction.

FIFA World Cup bid

As president, Mbeki spearheaded South Africa's successful bid to host the

2010 FIFA World Cup

The 2010 FIFA World Cup was the 19th FIFA World Cup, the world championship for List of men's national association football teams, men's national Association football, football teams. It took place in South Africa from 11 June to 11 July 2010. ...

. Commentators, and Mbeki himself, frequently linked the bid to his vision for an African renaissance. In 2015, amid an

American investigation into corruption at

FIFA

The Fédération Internationale de Football Association (), more commonly known by its acronym FIFA ( ), is the international self-regulatory governing body of association football, beach soccer, and futsal. It was founded on 21 May 1904 to o ...

, soccer administrator

Chuck Blazer testified that, between 2004 and 2011, he and other FIFA executives had received

bribes

Bribery is the corrupt solicitation, payment, or acceptance of a private favor (a bribe) in exchange for official action. The purpose of a bribe is to influence the actions of the recipient, a person in charge of an official duty, to act contrar ...

in connection with South Africa's bid. Mbeki denied any knowledge of the bribes.

Electricity crisis

In late 2007, Mbeki's government announced that the public power utility,

Eskom

Eskom Hld SOC Ltd or Eskom is a South African electricity public utility. Eskom was established in 1923 as the Electricity Supply Commission (ESCOM) (). Eskom represents South Africa in the Southern African Power Pool. The utility is the larg ...

, would introduce electricity rationing or rolling blackouts, commonly known in South Africa as

loadshedding