Sunni Islam is the largest

branch

A branch, also called a ramus in botany, is a stem that grows off from another stem, or when structures like veins in leaves are divided into smaller veins.

History and etymology

In Old English, there are numerous words for branch, includ ...

of

Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

and the largest

religious denomination

A religious denomination is a subgroup within a religion that operates under a common name and tradition, among other activities.

The term refers to the various Christian denominations (for example, Oriental Orthodox Churches, non-Chalcedonian, E ...

in the world. It holds that

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

did not appoint any

successor

Successor may refer to:

* An entity that comes after another (see Succession (disambiguation))

Film and TV

* ''The Successor'' (1996 film), a film including Laura Girling

* The Successor (2023 film), a French drama film

* ''The Successor'' ( ...

and that his closest companion

Abu Bakr

Abd Allah ibn Abi Quhafa (23 August 634), better known by his ''Kunya (Arabic), kunya'' Abu Bakr, was a senior Sahaba, companion, the closest friend, and father-in-law of Muhammad. He served as the first caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruli ...

() rightfully succeeded him as the

caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

of the Muslim community, being appointed at the meeting of

Saqifa

The Saqifa () of the Banu Sa'ida clan refers to the location of an event in early Islam where some of the Companions of the Prophet, companions of the Islamic prophet Muhammad pledged their allegiance to Abu Bakr as the first Caliphate, caliph and ...

. This contrasts with the

Shia view, which holds that Muhammad appointed

Ali ibn Abi Talib

Ali ibn Abi Talib (; ) was the fourth Rashidun caliph who ruled from until Assassination of Ali, his assassination in 661, as well as the first imamate in Shia doctrine, Shia Imam. He was the cousin and son-in-law of the Islamic prophet Muha ...

() as his successor. Nevertheless, Sunnis revere Ali, along with Abu Bakr,

Umar

Umar ibn al-Khattab (; ), also spelled Omar, was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () and is regarded as a senior companion and father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Mu ...

() and

Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan (17 June 656) was the third caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruling from 644 until his assassination in 656. Uthman, a second cousin, son-in-law, and notable companion of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, played a major role ...

() as '

rightly-guided caliphs'.

The term means those who observe the , the practices of Muhammad. The

Quran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

, together with

hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

(especially the

Six Books) and (scholarly consensus), form the basis of all

traditional jurisprudence within Sunni Islam.

Sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

legal rulings are derived from these basic sources, in conjunction with

consideration

Consideration is a concept of English law, English common law and is a necessity for simple contracts but not for special contracts (contracts by deed). The concept has been adopted by other common law jurisdictions. It is commonly referred to a ...

of

public welfare

Welfare spending is a type of government support intended to ensure that members of a society can meet basic human needs such as food and shelter. Social security may either be synonymous with welfare, or refer specifically to social insurance p ...

and

juristic discretion, using the

principles of jurisprudence developed by the four

legal schools:

Hanafi

The Hanafi school or Hanafism is the oldest and largest Madhhab, school of Islamic jurisprudence out of the four schools within Sunni Islam. It developed from the teachings of the Faqīh, jurist and theologian Abu Hanifa (), who systemised the ...

,

Hanbali

The Hanbali school or Hanbalism is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence, belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It is named after and based on the teachings of the 9th-century scholar, jurist and tradit ...

,

Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

and

Shafi'i

The Shafi'i school or Shafi'i Madhhab () or Shafi'i is one of the four major schools of fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It was founded by the Muslim scholar, jurist, and traditionis ...

.

In matters of

creed

A creed, also known as a confession of faith, a symbol, or a statement of faith, is a statement of the shared beliefs of a community (often a religious community) which summarizes its core tenets.

Many Christian denominations use three creeds ...

, the Sunni tradition upholds the six pillars of (faith) and comprises the

Ash'ari

Ash'arism (; ) is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (''mujaddid''), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on ...

and

Maturidi

Maturidism () is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu Mansur al-Maturidi. It is one of the three creeds of Sunni Islam alongside Ash'arism and Atharism, and prevails in the Hanafi school of jurisprudence.

Al-Maturidi codified a ...

schools of (theology) as well as the textualist

Athari

Atharism ( / , "of ''athar''") is a school of theology in Sunni Islam which developed from circles of the , a group that rejected rationalistic theology in favor of strict textualism in interpreting the Quran and the hadith.

Adherents of Ath ...

school. Sunnis regard the first four caliphs

Abu Bakr

Abd Allah ibn Abi Quhafa (23 August 634), better known by his ''Kunya (Arabic), kunya'' Abu Bakr, was a senior Sahaba, companion, the closest friend, and father-in-law of Muhammad. He served as the first caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruli ...

(),

Umar

Umar ibn al-Khattab (; ), also spelled Omar, was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () and is regarded as a senior companion and father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Mu ...

(),

Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan (17 June 656) was the third caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruling from 644 until his assassination in 656. Uthman, a second cousin, son-in-law, and notable companion of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, played a major role ...

() and

Ali () as (rightly-guided) and revere the , , and as the (predecessors).

Terminology

Sunna

The Arabic term , which Sunnis are named after, dates back to pre-Islamic language. It was used for "the right path that has always been followed". The term gained greater political significance after the murder of the third caliph,

Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan (17 June 656) was the third caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruling from 644 until his assassination in 656. Uthman, a second cousin, son-in-law, and notable companion of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, played a major role ...

(). It is said

Malik al-Ashtar, a famous follower of

Ali, provided encouragement during the

Battle of Siffin

The Battle of Siffin () was fought in 657 CE (37 Islamic calendar, AH) between the fourth Rashidun caliph Ali ibn Abi Talib and the rebellious governor of Syria (region), Syria Muawiyah I, Mu'awiya ibn Abi Sufyan. The battle is named after its ...

with the expression "Ali's political rival

Mu'awiya

Mu'awiya I (–April 680) was the founder and first caliph of the Umayyad Caliphate, ruling from 661 until his death. He became caliph less than thirty years after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and immediately after the four Rashid ...

kills the '". After the battle, it was agreed that "the righteous ', the unifying, not the divisive" ("") should be consulted to resolve the conflict. The time when the term ''sunna'' became the short form for "

Sunnah

is the body of traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time supposedly saw, followed, and passed on to the next generations. Diff ...

of the

Prophet

In religion, a prophet or prophetess is an individual who is regarded as being in contact with a divinity, divine being and is said to speak on behalf of that being, serving as an intermediary with humanity by delivering messages or teachings ...

" () is still unknown. During the

Umayyad Caliphate

The Umayyad Caliphate or Umayyad Empire (, ; ) was the second caliphate established after the death of the Islamic prophet Muhammad and was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty. Uthman ibn Affan, the third of the Rashidun caliphs, was also a member o ...

, several political movements, including the

Shia

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood ...

and the

Kharijites

The Kharijites (, singular ) were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the conflict with his challeng ...

rebelled against the formation of the state. They led their battles in the name of "the book of God (''

Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

'') and the ''Sunnah'' of his Prophet". During the

second Civil War (680–92) the Sunna term received connotations critical of

Shi'i

Shia Islam is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political successor (caliph) and as the spiritual leader of the Muslim community (imam). However, his right is understood to ...

doctrines (). It is recorded by Masrūq ibn al-Adschdaʿ (died 683), who was a ''

Mufti

A mufti (; , ) is an Islamic jurist qualified to issue a nonbinding opinion ('' fatwa'') on a point of Islamic law (''sharia''). The act of issuing fatwas is called ''iftāʾ''. Muftis and their ''fatāwa'' have played an important role thro ...

'' in

Kufa

Kufa ( ), also spelled Kufah, is a city in Iraq, about south of Baghdad, and northeast of Najaf. It is located on the banks of the Euphrates, Euphrates River. The estimated population in 2003 was 110,000.

Along with Samarra, Karbala, Kadhimiya ...

, a need to love the first two caliphs

Abū Bakr and

ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb and acknowledge their priority (). A disciple of Masrūq, the scholar ash-Shaʿbī (died between 721 and 729), who first sided with the Shia in Kufa during Civil War, but turned away in disgust by their fanaticism and finally decided to join the Umayyad Caliph

ʿAbd al-Malik, popularized the concept of ''Sunnah''. It is also passed down by ash-Shaʿbī that he took offense at the hatred on

ʿĀʾiša bint Abī Bakr and considered it a violation of the ''

Sunnah

is the body of traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time supposedly saw, followed, and passed on to the next generations. Diff ...

''.

The term ''Sunna'' instead of the longer expression or as a group-name for Sunnis is a relatively young phenomenon. It was probably

Ibn Taymiyyah

Ibn Taymiyya (; 22 January 1263 – 26 September 1328)Ibn Taymiyya, Taqi al-Din Ahmad, The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195125580.001.0001/acref-9780195125580-e-959 was a Sunni Muslim ulama, ...

, who used the short-term for the first time. It was later popularized by

pan-Islamic

Pan-Islamism () is a political movement which advocates the unity of Muslims under one Islamic country or state – often a caliphate – or an international organization with Islamic principles. Historically, after Ottomanism, which aimed at ...

scholars such as

Muhammad Rashid Rida in his treatise ("The Sunna and the Shia, Or

Wahhabism

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to oth ...

and

Rāfidism: Religious history, sociological and reform-oriented facts") published in 1928–29. The term ''Sunnah'' is usually used in Arabic discourse as designation for Sunni Muslims, when they are intended to be contrasted with Shias. The word pair ''Sunnah–Shia'' is also used on Western research literature to denote the ''Sunni–Shia'' contrast.

Ahl as-Sunna

One of the earliest supporting documents for derives from the Basric scholar Muhammad Ibn Siri (died 728). His is mentioned in the ''Sahih'' of

Muslim ibn al-Hajjaj

Abū al-Ḥusayn Muslim ibn al-Ḥajjāj ibn Muslim ibn Ward al-Qushayrī an-Naysābūrī (; after 815 – May 875 CE / 206 – 261 AH), commonly known as Imam Muslim, was an Islamic scholar from the city of Nishapur, particularly known as a ' ...

, and quoted having said: "Formerly one did not ask about the

Isnad

In the Islamic study of hadith, an isnād (chain of transmitters, or literally "supporting"; ) refers to a list of people who passed on a tradition, from the original authority to whom the tradition is attributed to, to the present person reciting ...

. But when the ''

fitna'' started, one said: 'Name us your informants'. One would then respond to them: If they were Sunnah people, you accept their hadith. But if they are people of the

Innovations

Innovation is the practical implementation of ideas that result in the introduction of new goods or services or improvement in offering goods or services. ISO TC 279 in the standard ISO 56000:2020 defines innovation as "a new or changed entit ...

, the hadith was rejected." G.H.A. Juynboll assumed, the term ''fitna'' in this statement is not related to the first Civil War (665–661) after murder of

ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān, but the second Civil War (680–692) in which the Islamic community was split into four parties (

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr

Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam (; May 624October/November 692) was the leader of a caliphate based in Mecca that rivaled the Umayyads from 683 until his death.

The son of al-Zubayr ibn al-Awwam and Asma bint Abi Bakr, and grandson of ...

, the

Umayyads, the Shia under

al-Mukhtār ibn Abī ʿUbaid and the Kharijites). The term ' designated in this situation whose, who stayed away from heretic teachings of the different warring parties.

The term ' was always a laudatory designation.

Abu Hanifa

Abu Hanifa (; September 699 CE – 767 CE) was a Muslim scholar, jurist, theologian, ascetic,Pakatchi, Ahmad and Umar, Suheyl, "Abū Ḥanīfa", in: ''Encyclopaedia Islamica'', Editors-in-Chief: Wilferd Madelung and, Farhad Daftary. and epony ...

(died 769), who sympathized with

Murdshia, insisted that this were "righteous people and people of the Sunnah" (''ahl al-ʿadl wa-ahl as-sunna''). According to

Josef van Ess Josef may refer to

*Josef (given name)

* Josef (surname)

* ''Josef'' (film), a 2011 Croatian war film

*Musik Josef

Musik Josef is a Japanese manufacturer of musical instruments. It was founded by Yukio Nakamura and is the only company in Japan spe ...

this term did not mean more than "honorable and righteous believing people". Among Hanafits the designation ' and ''ahl al-ʿadl'' (people of the righteous) remained interchangeable for a long time. Thus the Hanafite Abū l-Qāsim as-Samarqandī (died 953), who composed a

catechism

A catechism (; from , "to teach orally") is a summary or exposition of Catholic theology, doctrine and serves as a learning introduction to the Sacraments traditionally used in catechesis, or Christian religious teaching of children and adult co ...

for the

Samanides, used sometimes one expression and sometimes another for his own group.

[Ulrich Rudolph: ''Al-Māturīdī und die sunnitische Theologie in Samarkand.'' Brill, Leiden 1997. S. 66.]

Singular to ' was ''ṣāḥib sunna'' (adherent to the sunnah). This expression was used for example by

ʿAbd Allāh ibn al-Mubārak (died 797) for a person, who distances himself from the teachings of Shia,

Kharijites

The Kharijites (, singular ) were an Islamic sect which emerged during the First Fitna (656–661). The first Kharijites were supporters of Ali who rebelled against his acceptance of arbitration talks to settle the conflict with his challeng ...

, Qadarites and

Murjites. In addition, the

Nisba adjective ''sunnī'' was also used for the individual person. Thus it has been recorded, the Kufic scholar of the Quran Abū Bakr ibn ʿAyyāsh (died 809) was asked, how he was a "sunni". He responded the following: "The one who, when the heresies are mentioned, doesn't get excited about any of them." The Andalusiaian scholar

Ibn Hazm

Ibn Hazm (; November 994 – 15 August 1064) was an Andalusian Muslim polymath, historian, traditionist, jurist, philosopher, and theologian, born in the Córdoban Caliphate, present-day Spain. Described as one of the strictest hadith interpre ...

(died 1064) taught later that those who confess Islam can be divided into four groups: ',

Mutazilites, Murjites, Shites, Kharijites. The Muʿtazilites replaced the Qadarites here.

In the 9th century, one started to extent the term ' with further positive additions. Abu al-Hasan al-Ashari used for his own group expressions like ''ahl as-sunna wa-l-istiqāma'' ("people of Sunna and Straightness"), ''ahl as-sunna wa-l-ḥadīṯ'' ("people of Sunnah and of the Hadith") or ''ahl al-ḥaqq wa-s-sunna''

[So al-Ašʿarī: ''Kitāb al-Ibāna ʿan uṣūl ad-diyāna''. S. 8. – Engl. Übers. S. 49.] ("people of Truth and of the Sunnah").

Ahl as-Sunna wa l-Jamāʻah

The first appearances of the expression are entirely clear. In his Mihna edict, the Abbasite Caliph

Al-Ma'mūn (reigned 813–33) criticized a group of people who related themselves to the sunnah () and claimed they are the "people of truth, religion and community" (). ''Sunna'' and ''jamāʿah'' are already connected here. As a pair, these terms already appear in the 9th century. It is recorded that the disciple of

Ahmad ibn Hanbal

Ahmad ibn Hanbal (; (164-241 AH; 780 – 855 CE) was an Arab Muslim scholar, jurist, theologian, traditionist, ascetic and eponym of the Hanbali school of Islamic jurisprudence—one of the four major orthodox legal schools of Sunni Islam.

T ...

Harb ibn Ismail as-Sirjdshani (died 893) created a writing with the title ''as-Sunna wa l-Jamāʿah'', to which the Mutazilite Abu al-Qasim al-Balchi wrote a refutation later.

Al-Jubba'i

Abū 'Alī Muḥammad al-Jubbā'ī (; died c. 915) was an Arab Mu'tazili influenced theologian and philosopher of the 10th century. Born in Khuzistan, he studied in Basra where he trained Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, who went on to found his own th ...

(died 916) tells in his ''Kitāb al-Maqālāt'', that Ahmad ibn Hanbal attributed to his students the predicate ''sunnī jamāʿah'' ("Sunni Community"). This indicates that the Hanbalis were the first to use the phrase ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jamāʿah'' as a self-designation.

[Ess: ''Der Eine und das Andere''. 2011, Bd. II, S. 1276.]

Karramiyya theology, founded by Muhammad ibn Karram (died 859) referred to the sunnah and community. In praise of their school founder, they passed down a hadith, according to which Muhammad predicted that at the end of times a man named Muhammad ibn Karram will appear, who will restore the sunna and the community (''as-sunna wa l-jamāʿah'') and take Hidraj from Chorasan to Jerusalem, just how Muhammad himself took a Hidraj from Mecca to Medina.

According to the testimony of the

Transoxianian scholar Abu al-Yusr al-Bazdawi (died 1099), the Kullabites (followers of the Basrian scholar

Ibn Kullab

Ibn Kullab () (d. ca. 241/855) was an early Sunni theologian (mutakallim) in Basra and Baghdad in the first half of the 9th century during the time of the Mihna and belonged, according to Ibn al-Nadim, to the traditionalist group of the Nawabit. ...

ied 855 referred to themselves as also being among the ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jama''.

[al-Bazdawī: ''Kitāb Uṣūl ad-Dīn.'' 2003, S. 250.]

Abu al-Hasan al-Ashari used the expression ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jamāʿah'' rarely, and preferred another combination. Later Asharites like al-Isfaranini (died 1027) and Abd al-Qahir al-Baghdadi (died 1078) also used the expression ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jamāʿah'' and used them in their works to designate the teachings of their own school. According to al-Bazdawi, all Asharites in his time said they belong to the ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jamāʿah''.

During this time, the term was used as a self-designation by the Hanafite Maturidites in Transoxiania, used frequently by

Abu al-Layth al-Samarqandi

Abu al-Layth Nasr ibn Muhammad al-Samarqandi (; 944–983) was an Islamic scholar of the Hanafi school and Quran commentator, who lived during the second half of the 10th century.

Works

Al-Samarqandī authored various books on theology

The ...

(died 983), Abu Schakur as-Salimi (died 1086) and al-Bazdawi himself.

They used the term as a contrast to their enemies, among them Hanafites in the West, who have been followers of the Mutazilites. Al-Bazdawī also contrasted the ''Ahl as-Sunnah wa l-Jamāʻah'' with ''Ahl al-Ḥadīth'', "because they would adhere to teachings contrary to the Quran".

According to

Schams ad-Dīn al-Maqdisī (late 10th century) was the expression ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jamāʿah'' a laudatory term during his time, similar to ''ahl al-ʿadl wa-t-tawḥīd'' ("people of Righteousness and Divine Unity"), which was used for Mutazilites or generally designations like

Mu'minūn () or ''aṣḥāb al-hudā'' () for Muslims, who have been seen as righteous believers. Since the expression ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jamāʿah'' was used with a demand for righteous belief, it has been translated as in academic research.

There are different opinions regarding what the term ''jama'' in the phrase ''ahl as-sunna wa l-jama'' actually means, among Muslim scholars. In the Sunni Creed by

at-Tahawi (died 933), the term ''jama'' contrasts several times with the Arabic term ''furqa'' ("division, sectarianism"). Thus at-Tahāwī explains that ''jama'' is considered true or right (''ḥaqq wa-ṣawāb'') and ''furqa'' as aberration and punishment (''zaiġ wa-ʿaḏāb''). Ibn Taymiyyah argues that ''jama'', as opposed to ''furqa'', has the inherent meaning of ''iǧtimāʿ'' ("Coming together, being together, agreement"). Furthermore, he connects it with the principle of

Ijma

Ijma (, ) is an Arabic term referring to the consensus or agreement of the Islamic community on a point of Islamic law. Sunni Muslims regard it as one of the secondary sources of Sharia law, after the Qur'an, and the Sunnah.

Exactly what group s ...

, a third juridical source after the Book (Quran), and the Sunnah. The Ottoman scholar Muslih ad-Din al-Qastallani (died 1495) held the opinion that ''jama'' means 'path of the

Sahaba

The Companions of the Prophet () were the Muslim disciples and followers of the Islamic prophet Muhammad who saw or met him during his lifetime. The companions played a major role in Muslim battles, society, hadith narration, and governance ...

' (''ṭarīqat aṣ-ṣaḥāba'').

The modern Indonesian theologian

Nurcholish Madjid (died 2005) interpreted ''jama'' as an

inclusive concept: it means a society open for

pluralism and dialogue, though it does not particularly emphasize it.

History

One common mistake is to assume that Sunni Islam represents a normative Islam that emerged during the period after Muhammad's death, and that

Sufism

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

and

Shi'ism

Shia Islam is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that Muhammad in Islam, Muhammad designated Ali ibn Abi Talib () as both his political Succession to Muhammad, successor (caliph) and as the spiritual le ...

developed out of Sunni Islam. This perception is partly due to the reliance on highly ideological sources that have been accepted as reliable historical works, and also because the vast majority of the population is Sunni. Both Sunnism and Shiism are the end products of several centuries of competition between ideologies. Both sects used each other to further cement their own identities and doctrines.

The first four caliphs are known among Sunnis as the

Rāshidun or "Rightly-Guided Ones". Sunni recognition includes the aforementioned

Abu Bakr

Abd Allah ibn Abi Quhafa (23 August 634), better known by his ''Kunya (Arabic), kunya'' Abu Bakr, was a senior Sahaba, companion, the closest friend, and father-in-law of Muhammad. He served as the first caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruli ...

as the first,

Umar

Umar ibn al-Khattab (; ), also spelled Omar, was the second Rashidun caliph, ruling from August 634 until his assassination in 644. He succeeded Abu Bakr () and is regarded as a senior companion and father-in-law of the Islamic prophet Mu ...

as the second,

Uthman

Uthman ibn Affan (17 June 656) was the third caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, ruling from 644 until his assassination in 656. Uthman, a second cousin, son-in-law, and notable companion of the Islamic Prophet Muhammad, played a major role ...

as the third, and

Ali as the fourth.

Sunnis recognised different rulers as the

caliph

A caliphate ( ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with Khalifa, the title of caliph (; , ), a person considered a political–religious successor to the Islamic prophet Muhammad and a leader of ...

, though they barely ever included anyone in the list of the rightly guided ones or ''Rāshidun'' after the murder of Ali, until the caliphate was constitutionally abolished in

Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

on 3 March 1924.

Transition of caliphate into dynastic monarchy of Banu Umayya

The seeds of metamorphosis of caliphate into kingship were sown, as the second caliph Umar had feared, as early as the regime of the third caliph Uthman, who appointed many of his kinsmen from his clan

Banu Umayya, including

Marwān and

Walid bin Uqba on important government positions, becoming the main cause of turmoil resulting in his murder and the ensuing infighting during Ali's time and rebellion by

Muāwiya, another of Uthman's kinsman. This ultimately resulted in the establishment of firm dynastic rule of

Banu Umayya after

Husain Husain, a variant spelling of Hussein, is a common Arabic name, especially among Muslims because of the status of Husayn ibn Ali

Husayn ibn Ali (; 11 January 626 – 10 October 680 Common Era, CE) was a social, political and religious leader ...

, the younger son of Ali from

Fātima, was killed at the

Battle of Karbalā. The rise to power of Banu Umayya, the Meccan tribe of elites who had vehemently opposed Muhammad under the leadership of

Abu Sufyān, Muāwiya's father, right up to the

conquest of Mecca

The conquest of Mecca ( , alternatively, "liberation of Mecca") was a military campaign undertaken by Muhammad and Companions of the Prophet, his companions during the Muslim–Quraysh War. They led the early Muslims in an advance on the Quray ...

by Muhammad, as his successors with the accession of Uthman to caliphate, replaced the egalitarian society formed as a result of Muhammad's revolution to a society stratified between haves and have-nots as a result of

nepotism

Nepotism is the act of granting an In-group favoritism, advantage, privilege, or position to Kinship, relatives in an occupation or field. These fields can include business, politics, academia, entertainment, sports, religion or health care. In ...

, and in the words of El-Hibri through "the use of religious charity revenues (''

zakāt

Zakat (or Zakāh زكاة) is one of the Five Pillars of Islam. Zakat is the Arabic word for "Giving to Charity" or "Giving to the Needy". Zakat is a form of almsgiving, often collected by the Muslim Ummah. It is considered in Islam a reli ...

'') to subsidise family interests, which Uthman justified as al-sila''

' (pious filial support)". Ali, during his rather brief regime after Uthman maintained austere life style and tried hard to bring back the egalitarian system and supremacy of law over the ruler idealised in Muhammad's message, but faced continued opposition, and wars one after another by

Aisha

Aisha bint Abi Bakr () was a seventh century Arab commander, politician, Muhaddith, muhadditha and the third and youngest wife of the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad.

Aisha had an important role in early Islamic h ...

-

Talhah

Ṭalḥa ibn ʿUbayd Allāh al-Taymī (, ) was a companion of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. In Sunni Islam, he is mostly known for being among ('the ten to whom Paradise was promised'). He played an important role in the Battle of Uhud and ...

-

Zubair, by Muāwiya and finally by the

Khārjites. After he was murdered, his followers immediately elected

Hasan ibn Ali

Hasan ibn Ali (; 2 April 670) was an Alids, Alid political and religious leader. The eldest son of Ali and Fatima and a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, Hasan briefly ruled as Rashidun caliphate, Rashidun caliph from January 661 unt ...

his elder son from Fātima to succeed him. Hasan shortly afterward signed a treaty with

Muāwiya relinquishing power in favour of the latter, with a condition inter alia, that one of the two who will outlive the other will be the caliph, and that this caliph will not appoint a successor but will leave the matter of selection of the caliph to the public. Subsequently, Hasan was poisoned to death and Muawiya enjoyed unchallenged power. Dishonouring his treaty with Hasan, he nominated his son

Yazid

Yazīd (, "increasing", "adding more") is an Arabic name and may refer to:

Given name

* Yazid I (647–683), second Umayyad Caliph upon succeeding his father Muawiyah

* Yazid II (687–724), Umayyad caliph

* Yazid III (701–744), Umayyad caliph ...

to succeed him. Upon Muāwiya's death,

Yazid

Yazīd (, "increasing", "adding more") is an Arabic name and may refer to:

Given name

* Yazid I (647–683), second Umayyad Caliph upon succeeding his father Muawiyah

* Yazid II (687–724), Umayyad caliph

* Yazid III (701–744), Umayyad caliph ...

asked Husain, the younger brother of Hasan, Ali's son and Muhammad's grandson, to give his allegiance to Yazid, which he plainly refused. His caravan was cordoned by Yazid's army at Karbalā and he was killed with all his male companions – total 72 people, in a day long

battle

A battle is an occurrence of combat in warfare between opposing military units of any number or size. A war usually consists of multiple battles. In general, a battle is a military engagement that is well defined in duration, area, and force co ...

after which Yazid established himself as a sovereign, though strong public uprising erupted after his death against his dynasty to avenge the massacre of Karbalā, but

Banu Umayya were able to quickly suppress them all and ruled the Muslim world, till they were finally overthrown by

Banu Abbās.

Caliphate and the dynastic monarchy of Banu Abbās

The rule of and "caliphate" of Banu Umayya came to an end at the hands of Banu Abbās a branch of Banu Hāshim, the tribe of Muhammad, only to usher another dynastic monarchy styled as caliphate from 750 CE. This period is seen formative in Sunni Islam as the founders of the four schools viz,

Abu Hanifa

Abu Hanifa (; September 699 CE – 767 CE) was a Muslim scholar, jurist, theologian, ascetic,Pakatchi, Ahmad and Umar, Suheyl, "Abū Ḥanīfa", in: ''Encyclopaedia Islamica'', Editors-in-Chief: Wilferd Madelung and, Farhad Daftary. and epony ...

,

Malik ibn Anas

Malik ibn Anas (; –795) also known as Imam Malik was an Arab Islamic scholar and traditionalist who is the eponym of the Maliki school, one of the four schools of Islamic jurisprudence in Sunni Islam.Schacht, J., "Mālik b. Anas", in: ''E ...

,

Shāfi'i and

Ahmad bin Hanbal all practised during this time, so also did

Jafar al Sādiq who elaborated the doctrine of

imāmate, the basis for the Shi'a religious thought. There was no clearly accepted formula for determining succession in the Abbasid caliphate. Two or three sons or other relatives of the dying caliph emerged as candidates to the throne, each supported by his own party of supporters. A trial of strength ensued and the most powerful party won and expected favours of the caliph they supported once he ascended the throne. The caliphate of this dynasty ended with the death of the Caliph al-Ma'mun in 833 CE, when the period of Turkish domination began.

Sunni Islam in the contemporary era

The fall, at the end of

World War I

World War I or the First World War (28 July 1914 – 11 November 1918), also known as the Great War, was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War I, Allies (or Entente) and the Central Powers. Fighting to ...

of the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

, the biggest Sunni empire for six centuries, brought the caliphate to an end. This resulted in Sunni protests in far off places including the

Khilafat Movement

The Khilafat movement (1919–22) was a political campaign launched by Indian Muslims in British India over British policy against Turkey and the planned dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire after World War I by Allied forces.

Leaders particip ...

in India, which was later on upon gaining independence from Britain divided into Sunni-dominated

Pakistan

Pakistan, officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of over 241.5 million, having the Islam by country# ...

and secular

India

India, officially the Republic of India, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, seventh-largest country by area; the List of countries by population (United Nations), most populous country since ...

. Pakistan, the most populous Sunni state at its dawn, was later

partitioned into Pakistan and

Bangladesh

Bangladesh, officially the People's Republic of Bangladesh, is a country in South Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by population, eighth-most populous country in the world and among the List of countries and dependencies by ...

. The

demise of Ottoman caliphate also resulted in the emergence of

Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia, officially the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA), is a country in West Asia. Located in the centre of the Middle East, it covers the bulk of the Arabian Peninsula and has a land area of about , making it the List of Asian countries ...

, a dynastic absolute monarchy that championed the reformist doctrines of

Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab

Muḥammad ibn ʿAbd al-Wahhāb ibn Sulaymān al-Tamīmī (1703–1792) was a Sunni Muslim scholar, theologian, preacher, activist, religious leader, jurist, and reformer, who was from Najd in Arabian Peninsula and is considered as the eponymo ...

; the eponym of the

Wahhabi movement. This was followed by a considerable rise in the influence of the

Wahhabi

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to other ...

, ''

Salafiyya'',

Islamist and

Jihadist

Jihadism is a neologism for modern, armed militant Political aspects of Islam, Islamic movements that seek to Islamic state, establish states based on Islamic principles. In a narrower sense, it refers to the belief that armed confrontation ...

movements that revived the doctrines of the Hanbali theologian

Taqi Al-Din Ibn Taymiyyah (1263–1328 C.E/ 661–728 A.H), a fervent advocate of the traditions of the Sunni Imam

Ahmad ibn Hanbal

Ahmad ibn Hanbal (; (164-241 AH; 780 – 855 CE) was an Arab Muslim scholar, jurist, theologian, traditionist, ascetic and eponym of the Hanbali school of Islamic jurisprudence—one of the four major orthodox legal schools of Sunni Islam.

T ...

. The expediencies of

Cold War

The Cold War was a period of global Geopolitics, geopolitical rivalry between the United States (US) and the Soviet Union (USSR) and their respective allies, the capitalist Western Bloc and communist Eastern Bloc, which lasted from 1947 unt ...

resulted in the radicalisation of Afghan refugees in Pakistan who fought the

communist

Communism () is a sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology within the socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a socioeconomic order centered on common ownership of the means of production, di ...

regime backed by

USSR

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR), commonly known as the Soviet Union, was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 until Dissolution of the Soviet ...

forces in Afghanistan giving birth to the

Taliban movement. After the fall of communist regime in Afghanistan and the ensuing

civil war

A civil war is a war between organized groups within the same Sovereign state, state (or country). The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies.J ...

, Taliban wrestled power from the various

Mujahidin factions in

Afghanistan

Afghanistan, officially the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, is a landlocked country located at the crossroads of Central Asia and South Asia. It is bordered by Pakistan to the Durand Line, east and south, Iran to the Afghanistan–Iran borde ...

and formed a government under the leadership of

Mohammed Omar, who was addressed as the

Emir

Emir (; ' (), also Romanization of Arabic, transliterated as amir, is a word of Arabic language, Arabic origin that can refer to a male monarch, aristocratic, aristocrat, holder of high-ranking military or political office, or other person po ...

of the faithful, an honorific way of addressing the caliph. The Taliban regime was recognised by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia till after

9/11

The September 11 attacks, also known as 9/11, were four coordinated Islamist terrorist suicide attacks by al-Qaeda against the United States in 2001. Nineteen terrorists hijacked four commercial airliners, crashing the first two into ...

, perpetrated by

Osama bin Laden

Osama bin Laden (10 March 19572 May 2011) was a militant leader who was the founder and first general emir of al-Qaeda. Ideologically a pan-Islamist, Bin Laden participated in the Afghan ''mujahideen'' against the Soviet Union, and support ...

– a Saudi national by birth and harboured by the Taliban – took place, resulting in a

war on terror launched against the Taliban.

The sequence of events of the 20th century has led to resentment in some quarters of the Sunni community due to the loss of pre-eminence in several previously Sunni-dominated regions such as the

Levant

The Levant ( ) is the subregion that borders the Eastern Mediterranean, Eastern Mediterranean sea to the west, and forms the core of West Asia and the political term, Middle East, ''Middle East''. In its narrowest sense, which is in use toda ...

,

Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia is a historical region of West Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent. Today, Mesopotamia is known as present-day Iraq and forms the eastern geographic boundary of ...

, the

Balkans

The Balkans ( , ), corresponding partially with the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throug ...

, the

North Caucasus

The North Caucasus, or Ciscaucasia, is a subregion in Eastern Europe governed by Russia. It constitutes the northern part of the wider Caucasus region, which separates Europe and Asia. The North Caucasus is bordered by the Sea of Azov and the B ...

and the

Indian sub continent. The latest attempt by a radical wing of

Salafi-Jihadists to re-establish a Sunni caliphate was seen in the emergence of the militant group

ISIL

The Islamic State (IS), also known as the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) and Daesh, is a transnational Salafi jihadist organization and unrecognized quasi-state. IS occupied signif ...

, whose leader

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi

Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim Ali al-Badri (28 July 1971 – 27 October 2019), commonly known by his ''nom de guerre'' Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, was an Iraqi militant leader who was the founder and first leader of the Islamic State (IS), who proclaimed hims ...

is known among his followers as caliph and ''Amir-al-mu'mineen'', "The Commander of the Faithful". Jihadism is opposed from within the Muslim community (known as the ''

ummah

' (; ) is an Arabic word meaning Muslim identity, nation, religious community, or the concept of a Commonwealth of the Muslim Believers ( '). It is a synonym for ' (, lit. 'the Islamic nation'); it is commonly used to mean the collective com ...

'' in Arabic) in all quarters of the world as evidenced by turnout of almost 2% of the Muslim population in London protesting against ISIL.

Following the puritan approach of

Ibn Kathir

Abu al-Fida Isma'il ibn Umar ibn Kathir al-Dimashqi (; ), known simply as Ibn Kathir, was an Arab Islamic Exegesis, exegete, historian and scholar. An expert on (Quranic exegesis), (history) and (Islamic jurisprudence), he is considered a lea ...

,

Muhammad Rashid Rida, etc. many contemporary ''

Tafsir

Tafsir ( ; ) refers to an exegesis, or commentary, of the Quran. An author of a ''tafsir'' is a ' (; plural: ). A Quranic ''tafsir'' attempts to provide elucidation, explanation, interpretation, context or commentary for clear understanding ...

'' (exegetic treatises) downplay the earlier significance of

Biblical material (''Isrā'iliyyāt''). Half of the Arab commentaries reject ''Isrā'iliyyāt'' in general, while Turkish tafsir usually partly allow referring to Biblical material. Nevertheless, most non-Arabic commentators regard them as useless or not applicable.

[Johanna Pink (2010). ''Sunnitischer Tafsīr in der modernen islamischen Welt: Akademische Traditionen, Popularisierung und nationalstaatliche Interessen''. Brill, , pp. 114–116.] A direct reference to the

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is an ongoing military and political conflict about Territory, land and self-determination within the territory of the former Mandatory Palestine. Key aspects of the conflict include the Israeli occupation ...

could not be found. It remains unclear whether the refusal of ''Isrā'iliyyāt'' is motivated by political discourse or by traditionalist thought alone.

The usage of ''tafsir'ilmi'' is another notable characteristic of modern Sunni tafsir. ''Tafsir'ilmi'' stands for alleged scientific miracles found in the Qur'an. In short, the idea is that the Qur'an contains knowledge about subjects an author of the 7th century could not possibly have. Such interpretations are popular among many commentators. Some scholars, such as the Commentators of

Al-Azhar University

The Al-Azhar University ( ; , , ) is a public university in Cairo, Egypt. Associated with Al-Azhar Al-Sharif in Islamic Cairo, it is Egypt's oldest degree-granting university and is known as one of the most prestigious universities for Islamic ...

, reject this approach, arguing the Qur'an is a text for religious guidance, not for science and scientific theories that may be disproved later; thus ''tafsir'ilmi'' might lead to interpreting Qur'anic passages as falsehoods.

[Johanna Pink (2010). ''Sunnitischer Tafsīr in der modernen islamischen Welt: Akademische Traditionen, Popularisierung und nationalstaatliche Interessen''. Brill, , pp. 120–121.] Modern trends of Islamic interpretation are usually seen as adjusting to a modern audience and purifying Islam from alleged alterings, some of which are believed to be intentional corruptions brought into Islam to undermine and corrupt its message.

Adherents

Sunnis believe the

companions of

Muhammad

Muhammad (8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious and political leader and the founder of Islam. Muhammad in Islam, According to Islam, he was a prophet who was divinely inspired to preach and confirm the tawhid, monotheistic teachings of A ...

to be reliable transmitters of Islam, since God and Muhammad accepted their integrity. Medieval sources even prohibit cursing or vilifying them. This belief is based upon prophetic traditions such as one narrated by

Abdullah, son of Masud, in which Muhammad said: "The best of the people are my generation, then those who come after them, then those who come after them." Support for this view is also found in the

Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

, according to Sunnis. Therefore,

narratives of companions are also reliably taken into account for knowledge of the Islamic faith. Sunnis also believe that the companions were

true believers since it was the companions who were given the task of

compiling the Qur'an.

Sunni Islam does not have a formal hierarchy. Leaders are informal, and gain influence through study to become a scholar of Islamic law (''

sharia

Sharia, Sharī'ah, Shari'a, or Shariah () is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on Islamic holy books, scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran, Qur'an and hadith. In Islamic terminology ''sharīʿah'' ...

'') or Islamic theology (''

Kalām

''Ilm al-kalam'' or ''ilm al-lahut'', often shortened to ''kalam'', is the scholastic, speculative, or rational study of Islamic theology ('' aqida''). It can also be defined as the science that studies the fundamental doctrines of Islamic fai ...

''). Both religious and political leadership are in principle open to all Muslims. According to the Islamic Center of

Columbia,

South Carolina

South Carolina ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Southeastern United States, Southeastern region of the United States. It borders North Carolina to the north and northeast, the Atlantic Ocean to the southeast, and Georgia (U.S. state), Georg ...

, anyone with the intelligence and the will can become an Islamic scholar. During Midday Mosque services on Fridays, the congregation will choose a well-educated person to lead the service, known as a Khateeb (one who speaks).

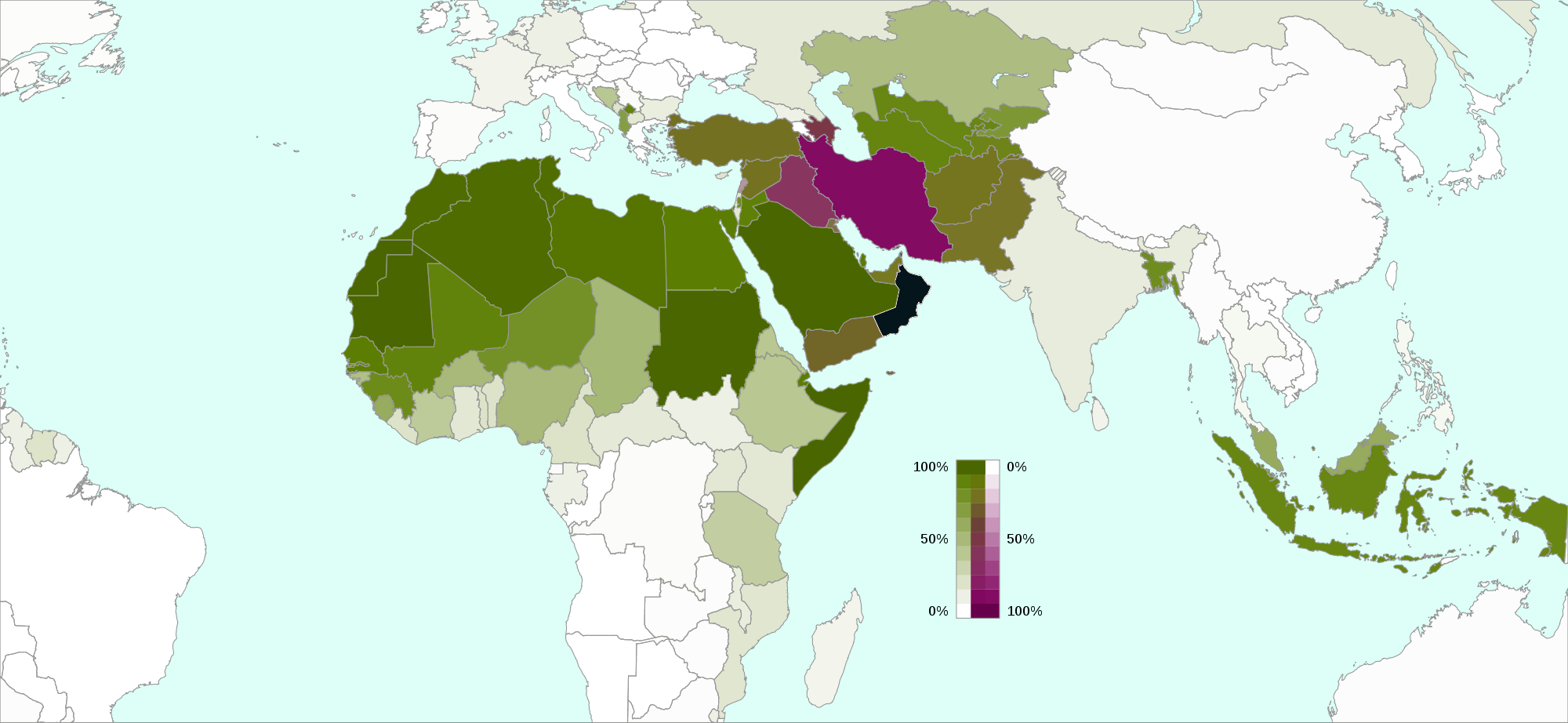

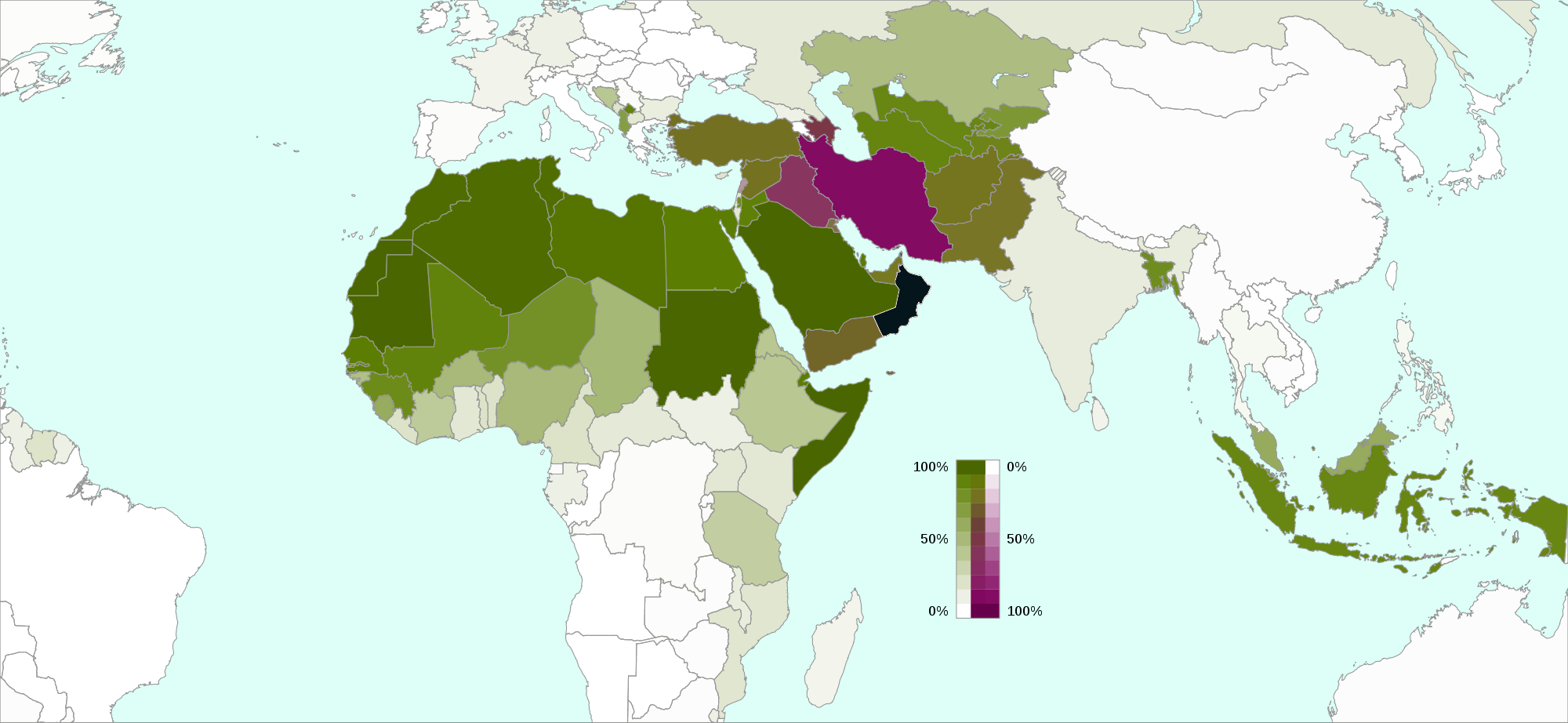

A study conducted by the ''

Pew Research Center

The Pew Research Center (also simply known as Pew) is a nonpartisan American think tank based in Washington, D.C. It provides information on social issues, public opinion, and demographic trends shaping the United States and the world. It ...

'' in 2010 and released January 2011

found that there are 1.62 billion Muslims around the world, and it is estimated over 85–90% are Sunni.

[See:

]

Eastern Europe Russia and Central Asia

"some 80% of the worlds Muslims are Sunni"

*

Sue Hellett;U.S. should focus on sanctions against Iran

"Sunnis make up over 75 percent of the world's Muslim population"

Iran, Israel and the United States

"Sunni, accounts for over 75% of the Islamic population"

A dictionary of modern politics

"probably 80% of the worlds Muslims are Sunni"

*

*

*

Sunni Islam: Oxford Bibliographies Online Research Guide

"Sunni Islam is the dominant division of the global Muslim community, and throughout history it has made up a substantial majority (85 to 90 percent) of that community."

Three group doctrines

There is no agreement among Muslim scholars as to which dogmatic tendencies are to be assigned to Sunni tradition. Since the early modern period, is the idea that a total of three groups belong to the Sunnis: 1. those named after

Abu l-Hasan al-Aschʿari (died 935)

Ashʿarites, 2. those named after

Abu Mansur al-Maturidi

Imam Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (; 853–944) was a Hanafi jurist and theologian who is the eponym of the Maturidi school of kalam in Sunnism. He got his from Māturīd, a district in Samarkand. His works include , a classic exegesis of the Qur'a ...

(died 941) named

Maturidi

Maturidism () is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu Mansur al-Maturidi. It is one of the three creeds of Sunni Islam alongside Ash'arism and Atharism, and prevails in the Hanafi school of jurisprudence.

Al-Maturidi codified a ...

tes and 3. a differently named third group, which is traditionalistic-oriented and rejects the rational discourse of

Kalām

''Ilm al-kalam'' or ''ilm al-lahut'', often shortened to ''kalam'', is the scholastic, speculative, or rational study of Islamic theology ('' aqida''). It can also be defined as the science that studies the fundamental doctrines of Islamic fai ...

advocated by the Maturidites and Ashʿarites. The Syrian scholar ʿAbd al-Baqi Ibn Faqih Fussa (died 1661) calls this third traditionalist group the Hanbalites. The late Ottoman thinker (died 1946), who agreed to dividing Sunnis into these three groups, called the traditionalist group

Salafiyya, but also used ''Athariyya'' as an alternative term. For the Maturidiyya he gives ''Nasafīyya'' as a possible alternative name.

[İsmail Hakkı İzmirli: ''Muḥaṣṣalü l-kelâm ve-l-ḥikme''. Istanbul 1336h (= 1917/18 n.Chr.). S. 75]

Digitalisat

/ref> Another used for the traditionalist-oriented group is "people of Hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

" (''ahl al-ḥadīṯ''). It is used, for example, in the final document of the Grozny Conference. Only those "people of the Hadith" are assigned to Sunnism who practice '' tafwīḍ'', i.e. who refrain from interpreting the ambiguous statements of the Quran.[Abschlussdokument der Grosny-Konferenz von 2016]

arabisches Original

un

deutsche Übersetzung

Ash'ari

Founded by Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari

Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari (; 874–936 CE) was an Arab Muslim theologian known for being the eponymous founder of the Ash'ari school of kalam in Sunnism.

Al-Ash'ari was notable for taking an intermediary position between the two diametrically ...

(873–935). This theological school of Aqeedah was embraced by many Muslim scholars

Lists of Islamic scholars include:

Lists

* List of contemporary Islamic scholars

* List of female Islamic scholars

* List of Muslim historians

* List of Islamic jurists

* List of Muslim philosophers

* List of Muslim astronomers

* List of ...

and developed in parts of the Islamic world throughout history; al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

wrote on the creed discussing it and agreeing upon some of its principles.

Ash'ari theology stresses divine revelation

Revelation, or divine revelation, is the disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity (god) or other supernatural entity or entities in the view of religion and theology.

Types Individual revelation

Thomas A ...

over human reason. Contrary to the Mu'tazilites, they say that ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

cannot be derived from human reason, but that God's commands, as revealed in the ''Quran'' and the ''Sunnah'' (the practices of Muhammad and his companions as recorded in the traditions, or hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

), are the sole source of all morality and ethics.

Regarding the nature of God and the divine attributes, the Ash'ari rejected the Mu'tazili

Mu'tazilism (, singular ) is an Islamic theological school that appeared in early Islamic history and flourished in Basra and Baghdad. Its adherents, the Mu'tazilites, were known for their neutrality in the dispute between Ali and his opponents ...

position that all Quranic references to God as having real attributes were metaphorical. The Ash'aris insisted that these attributes were as they "best befit His Majesty". The Arabic language is a wide language in which one word can have 15 different meanings, so the Ash'aris endeavor to find the meaning that best befits God and is not contradicted by the Quran. Therefore, when God states in the Quran, "He who does not resemble any of His creation", this clearly means that God cannot be attributed with body parts because He created body parts. Ash'aris tend to stress divine omnipotence

Omnipotence is the property of possessing maximal power. Monotheistic religions generally attribute omnipotence only to the deity of their faith. In the monotheistic religious philosophy of Abrahamic religions, omnipotence is often listed as ...

over human free will and they believe that the Quran is eternal and uncreated.

Maturidi

Founded by Abu Mansur al-Maturidi

Imam Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (; 853–944) was a Hanafi jurist and theologian who is the eponym of the Maturidi school of kalam in Sunnism. He got his from Māturīd, a district in Samarkand. His works include , a classic exegesis of the Qur'a ...

(died 944), Maturidiyyah was the major tradition in Central Asia

Central Asia is a region of Asia consisting of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. The countries as a group are also colloquially referred to as the "-stans" as all have names ending with the Persian language, Pers ...

based on Hanafi

The Hanafi school or Hanafism is the oldest and largest Madhhab, school of Islamic jurisprudence out of the four schools within Sunni Islam. It developed from the teachings of the Faqīh, jurist and theologian Abu Hanifa (), who systemised the ...

-law. It is more influenced by Persian interpretations of Islam and less on the traditions established within Arabian culture. In contrast to the traditionalistic approach, Maturidism allows to reject hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

s based on reason alone. Nevertheless, revelation remains important to inform humans about that is beyond their intellectual limits, such as the concept of an afterlife. Ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

on the other hand, do not need prophecy or revelation, but can be understood by reason alone. One of the tribes, the Seljuk Turks

The Seljuk dynasty, or Seljukids ( ; , ''Saljuqian'',) alternatively spelled as Saljuqids or Seljuk Turks, was an Oghuz Turks, Oghuz Turkic, Sunni Muslim dynasty that gradually became Persianate society, Persianate and contributed to Turco-Persi ...

, migrated to Turkey

Turkey, officially the Republic of Türkiye, is a country mainly located in Anatolia in West Asia, with a relatively small part called East Thrace in Southeast Europe. It borders the Black Sea to the north; Georgia (country), Georgia, Armen ...

, where later the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire (), also called the Turkish Empire, was an empire, imperial realm that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa from the 14th to early 20th centuries; it also controlled parts of southeastern Centr ...

was established. Their preferred school of law achieved a new prominence throughout their whole empire although it continued to be followed almost exclusively by followers of the Hanafi

The Hanafi school or Hanafism is the oldest and largest Madhhab, school of Islamic jurisprudence out of the four schools within Sunni Islam. It developed from the teachings of the Faqīh, jurist and theologian Abu Hanifa (), who systemised the ...

school while followers of the Shafi and Maliki

The Maliki school or Malikism is one of the four major madhhab, schools of Islamic jurisprudence within Sunni Islam. It was founded by Malik ibn Anas () in the 8th century. In contrast to the Ahl al-Hadith and Ahl al-Ra'y schools of thought, the ...

schools within the empire followed the Ash'ari and Athari schools of thought. Thus, wherever can be found Hanafi

The Hanafi school or Hanafism is the oldest and largest Madhhab, school of Islamic jurisprudence out of the four schools within Sunni Islam. It developed from the teachings of the Faqīh, jurist and theologian Abu Hanifa (), who systemised the ...

followers, there can be found the Maturidi

Maturidism () is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu Mansur al-Maturidi. It is one of the three creeds of Sunni Islam alongside Ash'arism and Atharism, and prevails in the Hanafi school of jurisprudence.

Al-Maturidi codified a ...

creed.

Athari

Traditionalist or Athari theology is a movement of Islam

Islam is an Abrahamic religions, Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the Quran, and the teachings of Muhammad. Adherents of Islam are called Muslims, who are estimated to number Islam by country, 2 billion worldwide and are the world ...

ic scholars who reject rationalistic Islamic theology (''kalam

''Ilm al-kalam'' or ''ilm al-lahut'', often shortened to ''kalam'', is the scholastic, speculative, or rational study of Islamic theology ('' aqida''). It can also be defined as the science that studies the fundamental doctrines of Islamic fai ...

'') in favor of strict textualism in interpreting the ''Qur'an

The Quran, also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation directly from God ('' Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which consist of individual verses ('). Besides ...

'' and ''sunnah

is the body of traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time supposedly saw, followed, and passed on to the next generations. Diff ...

''. The name derives from "tradition" in its technical sense as translation of the Arabic word ''hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

''. It is also sometimes referred to as ''athari'' as by several other names.

Adherents of traditionalist theology believe that the '' zahir'' (literal, apparent) meaning of the ''Qur'an'' and the hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

have sole authority in matters of belief and law; and that the use of rational disputation is forbidden even if it verifies the truth.tafwid

Tafwid () is an Arabic term meaning "relegation" or "delegation", with uses in theology and law.

In theology

In Islamic theology, ''tafwid'' (or ''tafwid al-amr li-llah'', relegation of matters to God) is a doctrine according to which the mean ...

'').Bi-la kaifa

The Arabic phrase ''Bila Kayf'', also pronounced as ''Bila Kayfa'', () is roughly translated as "without asking how", "without knowing how", or "without modality" and refers to the belief that the verses of the Qur'an with an "unapparent meanin ...

".

Traditionalist theology emerged among scholars of hadith who eventually coalesced into a movement called ''ahl al-hadith

() is an Islamic school of Sunni Islam that emerged during the 2nd and 3rd Islamic centuries of the Islamic era (late 8th and 9th century CE) as a movement of hadith scholars who considered the Quran and authentic hadith to be the only authority ...

'' under the leadership of Ibn Hanbal.Mu'tazilites

Mu'tazilism (, singular ) is an Islamic theological school that appeared in early Islamic history and flourished in Basra and Baghdad. Its adherents, the Mu'tazilites, were known for their neutrality in the dispute between Ali and his opponents ...

and other theological currents, condemning many points of their doctrine as well as the rationalistic methods they used in defending them.al-Ash'ari

Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari (; 874–936 CE) was an Arab Islamic theology, Muslim theologian known for being the eponymous founder of the Ash'ari school of kalam in Sunnism.

Al-Ash'ari was notable for taking an intermediary position between the two ...

and al-Maturidi

Imam Abu Mansur al-Maturidi (; 853–944) was a Hanafi jurist and theologian who is the eponym of the Maturidi school of kalam in Sunnism. He got his from Māturīd, a district in Samarkand. His works include , a classic exegesis of the Qu ...

found a middle ground between Mu'tazilite rationalism and Athari

Atharism ( / , "of ''athar''") is a school of theology in Sunni Islam which developed from circles of the , a group that rejected rationalistic theology in favor of strict textualism in interpreting the Quran and the hadith.

Adherents of Ath ...

literalism, using the rationalistic methods championed by Mu'tazilites to defend most tenets of the traditionalist doctrine. Although the mainly Athari scholars who rejected this synthesis were in the minority, their emotive, narrative-based approach to faith remained influential among the urban masses in some areas, particularly in Abbasid

The Abbasid Caliphate or Abbasid Empire (; ) was the third caliphate to succeed the prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad. It was founded by a dynasty descended from Muhammad's uncle, Abbas ibn Abd al-Muttalib (566–653 C ...

Baghdad

Baghdad ( or ; , ) is the capital and List of largest cities of Iraq, largest city of Iraq, located along the Tigris in the central part of the country. With a population exceeding 7 million, it ranks among the List of largest cities in the A ...

.

While Ash'arism

Ash'arism (; ) is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (''mujaddid''), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on ...

and Maturidism

Maturidism () is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu Mansur al-Maturidi. It is one of the three creeds of Sunni Islam alongside Ash'arism and Atharism, and prevails in the Hanafi school of jurisprudence.

Al-Maturidi codified ...

are often called the Sunni "orthodoxy", traditionalist theology has thrived alongside it, laying rival claims to be the orthodox Sunni faith. In the modern era, it has had a disproportionate impact on Islamic theology, having been appropriated by Wahhabi

Wahhabism is an exonym for a Salafi revivalist movement within Sunni Islam named after the 18th-century Hanbali scholar Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab. It was initially established in the central Arabian region of Najd and later spread to other ...

and other traditionalist Salafi

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a fundamentalist revival movement within Sunni Islam, originating in the late 19th century and influential in the Islamic world to this day. The name "''Salafiyya''" is a self-designation, claiming a retu ...

currents and have spread well beyond the confines of the Athari

Atharism ( / , "of ''athar''") is a school of theology in Sunni Islam which developed from circles of the , a group that rejected rationalistic theology in favor of strict textualism in interpreting the Quran and the hadith.

Adherents of Ath ...

school.

Narrow definition

There were also Muslim scholars who wanted to limit the Sunni term to the ''Ash'ari

Ash'arism (; ) is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (''mujaddid''), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on ...

tes'' and '' Māturīdites'' alone. For example, Murtadā az-Zabīdī (died 1790) wrote in his commentary on al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111), archaically Latinized as Algazelus, was a Shafi'i Sunni Muslim scholar and polymath. He is known as one of the most prominent and influential jurisconsults, legal theoreticians, muftis, philosophers, the ...

s "Iḥyāʾ ʿulūm ad-dīn": "When (sc. The term) ''ahl as-sunna wal jamaʿa'' is used, the Ashʿarites and Māturīdites are meant."[Murtaḍā az-Zabīdī]

''Itḥāf as-sāda al-muttaqīn bi-šarḥ Iḥyāʾ ʿulūm ad-dīn''

Muʾassasat at-taʾrīḫ al-ʿArabī, Beirut, 1994. Vol. II, p. 6. This position was also taken over by the Egyptian Fatwa Office in July 2013.[''al-Murād bi-ahl as-sunna wa-l-ǧamāʿa''](_blank)

Fatwa No. 2366 of the Egyptian Fatwa Office of 24 July 2013. In Ottoman times, many efforts were made to establish a good harmony between the teachings of the Ashʿarīya and the Māturīdīya.Fatiha

Al-Fatiha () is the first chapter () of the Quran. It consists of seven verses (') which consist of a prayer for guidance and mercy.

Al-Fatiha is recited in Muslim obligatory and voluntary prayers, known as ''salah''. The primary literal mea ...

: "As far as the Sunnis are concerned, it is the Ashʿarites and those who follow in their correct belief."

Conversely, there were also scholars who excluded the Ashʿarites from Sunnism. The Andalusian scholar Ibn Hazm

Ibn Hazm (; November 994 – 15 August 1064) was an Andalusian Muslim polymath, historian, traditionist, jurist, philosopher, and theologian, born in the Córdoban Caliphate, present-day Spain. Described as one of the strictest hadith interpre ...

(died 1064) said that Abu l-Hasan al-Ashʿarī belonged to the Murji'a, namely those who were particularly far removed from the Sunnis in terms of faith.[Ibn Ḥazm: ''al-Faṣl fi-l-milal wa-l-ahwāʾ wa-n-niḥal.'' Ed. Muḥammad Ibrāhīm Naṣr; ʿAbd-ar-Raḥmān ʿUmaira. Dār al-Jīl, Beirut 1985. Vol. II, pp. 265ff.] Twentieth-century Syrian

Syrians () are the majority inhabitants of Syria, indigenous to the Levant, most of whom have Arabic, especially its Levantine and Mesopotamian dialects, as a mother tongue. The cultural and linguistic heritage of the Syrian people is a blend ...

-Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

Athari Salafi

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a fundamentalist revival movement within Sunni Islam, originating in the late 19th century and influential in the Islamic world to this day. The name "''Salafiyya''" is a self-designation, claiming a retu ...

theologian Muhammad Nasir al-Din al-Albani rejected extremism in excluding Ash'ari

Ash'arism (; ) is a school of theology in Sunni Islam named after Abu al-Hasan al-Ash'ari, a Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer (''mujaddid''), and scholastic theologian, in the 9th–10th century. It established an orthodox guideline, based on ...

s from Sunni Islam. He believed that despite that their fundamental differences from Atharis, not every Ash'ari is to be excluded from ''Ahl al-Sunna wal Jama'ah'', unless they openly disapprove of the doctrines of the ''Salaf

Salaf (, "ancestors" or "predecessors"), also often referred to with the honorific expression of al-salaf al-ṣāliḥ (, "the pious predecessors"), are often taken to be the first three generations of Muslims. This comprises companions of the ...

'' (''mad'hab as-Salaf''). According to Albani:

Sunnism in general and in a specific sense

The Hanbali

The Hanbali school or Hanbalism is one of the four major schools of Islamic jurisprudence, belonging to the Ahl al-Hadith tradition within Sunni Islam. It is named after and based on the teachings of the 9th-century scholar, jurist and tradit ...

scholar Ibn Taymiyyah

Ibn Taymiyya (; 22 January 1263 – 26 September 1328)Ibn Taymiyya, Taqi al-Din Ahmad, The Oxford Dictionary of Islam. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195125580.001.0001/acref-9780195125580-e-959 was a Sunni Muslim ulama, ...

(died 1328) distinguished in his work ''Minhāj as-sunna'' between Sunnis in the general sense (''ahl as-unna al-ʿāmma'') and Sunnis in the special sense (''ahl as-sunna al-ḫāṣṣa''). Sunnis in the general sense are all Muslims who recognize the caliphate of the three caliphs ( Abū Bakr, ʿUmar ibn al-Khaṭṭāb and ʿUthmān ibn ʿAffān). In his opinion, this includes all Islamic groups except the Shiite Rafidites. Sunnis in the special sense are only the "people of the hadith" (''ahl al-ḥadīṯ'').

İsmail Hakkı İzmirli, who took over the distinction between a broader and narrower circle of Sunnis from Ibn Taimiya, said that Kullabiyya and the Ashʿarīyya are Sunnis in the general sense, while the Salafiyya represent Sunnis in the specific sense. About the Maturidiyya he only says that they are closer to the Salafiyya than the Ashʿariyya because they excel more in Fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.[Fiqh](_blank)

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

than in Kalām

''Ilm al-kalam'' or ''ilm al-lahut'', often shortened to ''kalam'', is the scholastic, speculative, or rational study of Islamic theology ('' aqida''). It can also be defined as the science that studies the fundamental doctrines of Islamic fai ...

.[Muḥammad ibn ʿUṯaimīn: ''Aš-Šarḥ al-mumtiʿ ʿalā Zād al-mustaqniʿ''. Dār Ibn al-Ǧauzī, Dammam, 2006. Bd. XI, S. 30]

Digitalized

/ref>

Classification of the Muʿtazila

The Muʿtazilites are usually not regarded as Sunnis. Ibn Hazm

Ibn Hazm (; November 994 – 15 August 1064) was an Andalusian Muslim polymath, historian, traditionist, jurist, philosopher, and theologian, born in the Córdoban Caliphate, present-day Spain. Described as one of the strictest hadith interpre ...

, for example, contrasted them with the Sunnis as a separate group in his heresiographic work ''al-Faṣl fi-l-milal wa-l-ahwāʾ wa-n-niḥal''.fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

'' office ruled out in a fatwa

A fatwa (; ; ; ) is a legal ruling on a point of Islamic law (sharia) given by a qualified Islamic jurist ('' faqih'') in response to a question posed by a private individual, judge or government. A jurist issuing fatwas is called a ''mufti'', ...

that the Muʿtazilites, like the Kharijites, represent a doctrine that is contrary to Sunnism. Ibn Taymiyya argued that the Muʿtazilites belong to the Sunnis in the general sense because they recognize the caliphate of the first three caliphs.

Mysticism

There is broad agreement that the Sufis are also part of Sunnism. This view can already be found in the Shafi'ite scholar Abu Mansur al-Baghdadi

Abū Manṣūr ʿAbd al-Qāhir ibn Ṭāhir bin Muḥammad bin ʿAbd Allāh al-Tamīmī al-Shāfiʿī al-Baghdādī (), more commonly known as Abd al-Qāhir al-Baghdādī () or simply Abū Manṣūr al-Baghdādī () was an Arab Sunni scholar fr ...

(died 1037). In his heresiographical work '' al-Farq baina l-firaq '' he divided the Sunnis into eight different categories (''aṣnāf'') of people: 1. the theologians and Kalam

''Ilm al-kalam'' or ''ilm al-lahut'', often shortened to ''kalam'', is the scholastic, speculative, or rational study of Islamic theology ('' aqida''). It can also be defined as the science that studies the fundamental doctrines of Islamic fai ...

Scholars, 2. the Fiqh

''Fiqh'' (; ) is the term for Islamic jurisprudence.[Fiqh](_blank)

Encyclopædia Britannica ''Fiqh'' is of ...

scholars, 3. the traditional and Hadith

Hadith is the Arabic word for a 'report' or an 'account f an event and refers to the Islamic oral tradition of anecdotes containing the purported words, actions, and the silent approvals of the Islamic prophet Muhammad or his immediate circle ...

scholars, 4. the Adab and language scholars, 5. the Koran

The Quran, also Romanization, romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a Waḥy, revelation directly from God in Islam, God (''Allah, Allāh''). It is organized in 114 chapters (, ) which ...

– Scholars, 6. the Sufi

Sufism ( or ) is a mysticism, mystic body of religious practice found within Islam which is characterized by a focus on Islamic Tazkiyah, purification, spirituality, ritualism, and Asceticism#Islam, asceticism.

Practitioners of Sufism are r ...

ascetics (''az-zuhhād aṣ-ṣūfīya''), 7. those who perform the ''ribat

A ribāṭ (; hospice, hostel, base or retreat) is an Arabic term, initially designating a small fortification built along a frontier during the first years of the Muslim conquest of the Maghreb to house military volunteers, called ''murabitun' ...

'' and ''jihad